Open Journal of Medical Psychology

Vol. 1 No. 4 (2012) , Article ID: 23931 , 4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojmp.2012.14012

Relationships among Health and Spiritual Beliefs, Religious Practices, and Congregational Support in Individuals with Cancer

1Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA

2Department of Health Psychology, School of Health Professions, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA

3School of Social Work, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA

Email: *johnstoneg@missouri.edu

Received July 10, 2012; revised September 3, 2012; accepted September 15, 2012

Keywords: Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality; BMMRS; Religion; Spirituality; Health; Cancer

ABSTRACT

To assess relationships among physical health, mental health, spiritual experiences, religious practices, and perceived congregational support for individuals with cancer. Design: A cross-sectional analysis of 56 individuals from outpatient settings (25 with cancer, 31 healthy controls). Measures: Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality (BMMRS; [1]); Medical Outcomes Scale-Short Form 36 (SF-36) General Health Perception (GHP) and General Mental Health (GMH) scales. Results: Participants with cancer reported significantly higher levels of Daily Spiritual Experiences and Religious Support on the BMMRS than the Healthy Controls. No BMMRS subscales were significantly correlated with the SF-36, although the BMMRS subscales had larger correlations with the SF-36 GMH scale (mean = 0.23; range = 0.14 - 0.37) than the GHP scale (mean = 0.16; range = 0.01 - 0.33). Conclusions: Individuals with cancer rely on spiritual beliefs and congregations support more than healthy controls. Statistical trends indicate that individuals with cancer use spiritual, religious, and congregational support factors primarily to assist them in emotionally coping with their disease, rather than to improve physical health.

1. Introduction

There has been increased interest in determining the relationship among religious, spiritual, and health variables over the past decade, as increased religiosity has generally been demonstrated to be related to better health [2-7]. Research has focused on these relationships for persons with cancer given that cancer is the second leading cause of death in the US [8]. Individuals with cancer typically have the sudden diagnosis of a life changing and threatening illness which is often associated with shock, denial, and need for profound adaptation (i.e., cancer survivorship). As a result, many individuals with cancer turn to spiritual and religious resources to assist them in coping with their disease, and to provide meaning and perspective to the illness process [7,9,10]. Unfortunately, the specific mechanisms that exist among spiritual, religious, and health variables remain unclear for persons with cancer.

A major weakness inherent in religion and health research to date, including the area of cancer, relates to the imprecise definition and measurement of “religious” and “spiritual” factors, as these terms are often used interchangeably [11]. For this reason the Fetzer Institute and the National Institute on Aging developed the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality (BMMRS) [1] to distinguish between spiritual (i.e., beliefs in and connection to a higher power) and religious variables (i.e., culturally based practices such as prayer, reading of scriptures, and service attendance). However, a recent factor analysis of the BMMRS suggests that it may be best to conceptualize the BMMRS as measuring three distinct aspects, including spiritual experience, religious practices, and congregational support [12].

Although the BMMRS has recently been investigated with several populations with chronic disabling conditions such as traumatic brain injury [13], stroke [14], and spinal cord injury [15], it has yet to be investigated with persons with cancer. Regression analyses with these rehabilitation populations (and including participants from the current study) indicate that the physical and mental health of individuals with heterogeneous medical conditions is primarily related to spiritual and congregational support factors, but not religious practices [16,17].

Because the BMMRS has not been used to date with individuals with cancer, the purpose of the current study was to determine the manner in which persons with cancer rely on spiritual, religious, and congregational support factors (using the BMMRS), as well as the relationships that exist among these variables and physical and mental health.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

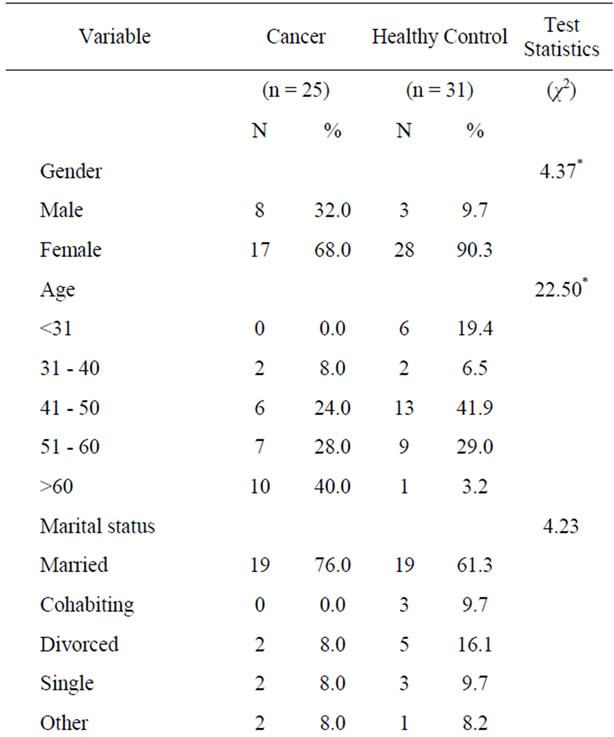

The sample was drawn from a larger cross-sectional study examining the relationships among spirituality, religion, and health outcomes of individuals with heterogeneous medical disorders. Participants (n = 56) were recruited from a Midwestern academic health center, including 25 with cancer and 31 healthy controls. Participants were included if they were at least 18 years old, spoke English, and were capable of completing the questionnaires. Given that the data were collected as a larger pilot study of participants, no information was obtained regarding type or stage of disease. Demographic characteristics for the two groups are shown in Table 1. There were statistically significant differences between the two groups in gender, age, and education.

2.2. Procedure

The current study was exploratory and used a convenience sample. Participants in the cancer group were contacted in an outpatient clinic at a cancer hospital by a research team member and asked to participate in the study. The medical diagnosis was made by an oncologist. Healthy controls were recruited from a sample of employees at a local university wellness program. It was assured that the healthy controls were without significant medical (e.g., cancer, traumatic brain injury) or psychological disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder). If individuals expressed an interest in the study, a description of the research was provided and written informed consent was obtained per procedures approved by the appropriate institutional review board. Subsequently, participants completed a research packet consisting of paper-and-pencil measures of spirituality/religion (i.e., BMMRS), health status (i.e., SF-36), and demographic information (i.e., gender, age, marital status, education, annual income, and religious preference). Respondents received nominal compensation for their participation.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality (BMMRS)

The BMMRS is a 38-item self-report survey, with Likert

Table 1. Comparison of demographic characteristics by group.

scale formats [1]. Any reference to “God” in original BMMRS items was changed to “higher power” for this study to make the measure more suitable for individuals of all faith traditions. Lower scores are indicative of a greater degree of religiosity or spiritual experience for all BMMRS items.

For the current study, based on the recent factor analysis of the BMMRS [12], the BMMRS subscales were conceptualized as measuring Spiritual Experiences (i.e., emotional experience of feeling connected to a higher power), Religious Practices (i.e., culturally based activities), and Congregational Support factors.

2.3.2. Spiritual Experience Subscales

Daily Spiritual Experience measures the individual’s connection with a higher power in daily life (e.g., “I feel the presence of a higher power,” “I feel deeper peace or harmony,” “I desire to be closer to or in union with a higher power.”). This subscale consists of 6 items rated on a 6-point response format, ranging from 1 (many times a day) to 6 (never). The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.75.

Meaning measures a sense of meaning in life (e.g., “The events in my life unfold according to a divine or greater plan,” “I have a sense of mission or calling in my own life.”). This subscale is composed of 2 items with a 4-point response format, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). The internal consistency reliability was 0.30. Given this low measure of reliability, the Meaning subscale was not included in statistical analyses.

Values/Beliefs measures religious values and beliefs (e.g., “I feel a deep sense of responsibility for reducing pain and suffering in the world,” “I believe in a God who watches over me.”). This subscale is composed of 2 items with a 4-point response format, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). The internal consistency reliability was 0.10. Given this low measure of reliability, the Values/Beliefs subscale was not included in statistical analyses.

Forgiveness measures the degree of forgiveness of self and others, and a belief in the forgiveness of a higher power (e.g., “I have forgiven those who hurt me,” “I know that I am forgiven by a higher power.”). The subscale consists of 3 items rated on a 4-point response format, ranging from 1 (always) to 4 (never). The internal consistency reliability was 0.77.

Religious/Spiritual Coping purportedly measures religious and spiritual coping strategies (e.g., “I work together with a higher power as partners,” “I look to a higher power for strength, support, and guidance.”). Although its title suggests it measures both “religious” and “spiritual” coping, a previous factor analytic study indicates that items from this scale load on a spiritual factor [12]. As a result, for the purposes of this study it was conceptualized as a “spiritual” subscale. This subscale consists of 7 items with a 4-point response format, ranging from 1 (a great deal) to 4 (not at all). The internal consistency reliability was 0.78.

2.3.3. Religious Practices Subscales

Private Religious Practices measures religious behaviors (e.g., “Within your religious or spiritual tradition, how often do you mediate?” “How often do you watch or listen to religious programs on TV or radio?”). This subscale is composed of 5 items with an 8-point response format, ranging from 1 (more than once a day) to 5 (never). The internal consistency reliability was 0.81.

Organizational Religiousness measures the frequency of involvement in formal public religious institutions (e.g., “How often do you go to religious service?” “Besides religious service, how often do you take part in other activities at a place of worship?”). This subscale consists of 2 items with a 6-point response format, ranging from 1 (more than once a week) to 6 (never). The internal consistency reliability was 0.68.

2.3.4. Congregational Social Support Subscale

Religious Support measures the degree to which individuals perceive that their local congregations provide help, support, and comfort (e.g., “If you had a problem or were faced with a difficult situation, how much comfort would the people in your congregation be willing to give you?”). This subscale is composed of 4 items and a 4-point response format was used, ranging from 1 (very often) to 4 (never). The internal consistency reliability was 0.63.

2.3.5. SF-Health Status Questionnaire

The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-Version 2 (SF-36) [18] is a 36-item questionnaire that assesses eight dimensions of self-perceived health. For the current study the SF-36 General Health Perception (GHP) scale was used to measure general physical health, and the SF-36 General Mental Health (GMH) subscale was used to assess general mental health functioning.

General Health Perception assesses individual’s perceptions of themselves as healthy versus sick, with expectations for improving or declining health. This scale is composed of 5 items with a 5-point response format, ranging from 1 (definitely true) to 5 (definitely false). The internal consistency reliability was 0.78.

General Mental Health is composed of 5 items and a 6-point response format, ranging from 1 (all of the time) to 6 (none of the time), with items assessing constructs such as happiness, peace, nervousness, and sadness. The internal consistency reliability was 0.82.

3. Results

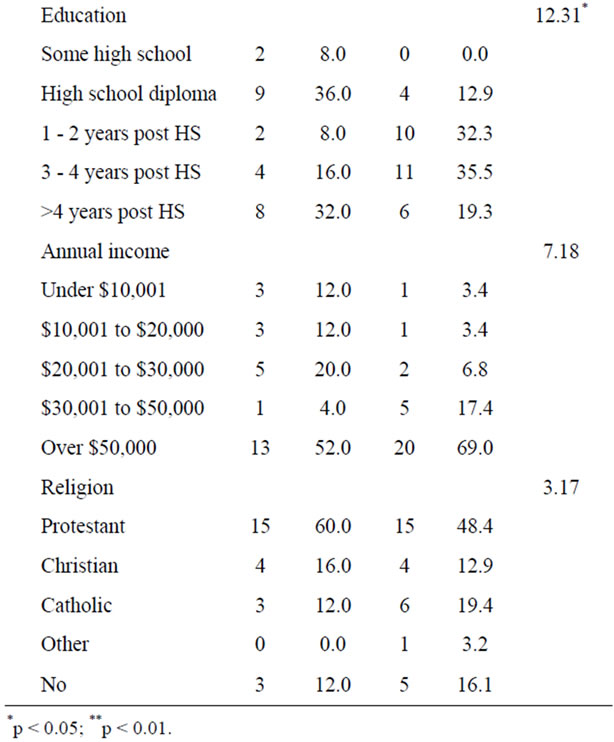

1) BMMRS and SF-36 Group Mean Differences.

There were statistically significant differences for 2 of 6 BMMRS scales between the Cancer and Healthy Control groups, including Daily Spiritual Experiences (t = –2.48, p < 0.05) and Religious Support (t = –2.78, p < 0.001). As stated previously, the Meaning and Values/Beliefs subscales were not used in the analysis due to low reliability. Participants with cancer reported higher levels of spiritual experiences and religious support than healthy controls. In terms of health status, there were statistically significant group mean differences in General Health Perception (t = 5.08, p < 0.001), but not in General Mental Health, with healthy controls reporting better general physical health (see Table 2).

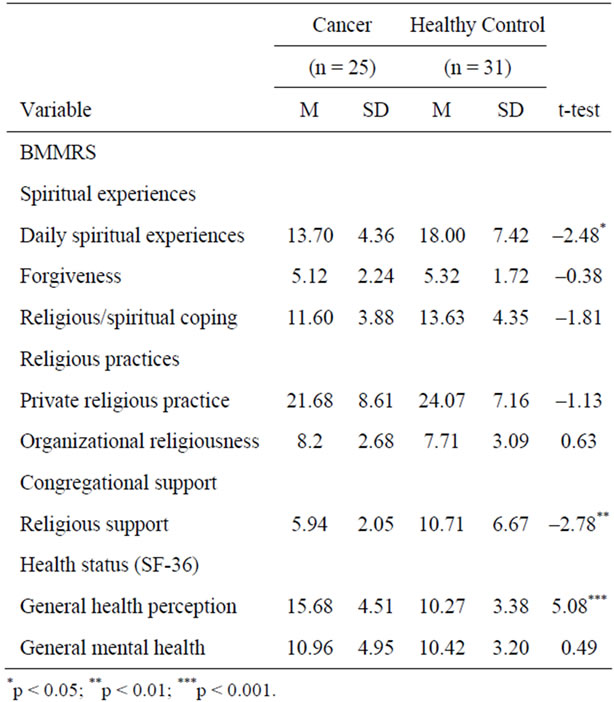

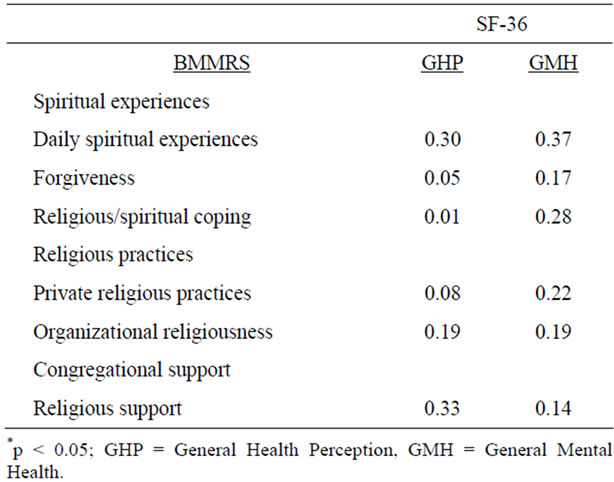

2) Correlation Analyses of Measured Variables.

Given the interest in persons with cancer, Pearson correlations are reported for only this group (see Table 3). No BMMRS subscales were significantly correlated with the SF-36, although inspection of the data indicate that the BMMRS subscales had larger correlations with the SF-36 GMH scale (mean = 0.23; range = 0.14 - 0.37) than the GHP scale (mean = 0.16; range = 0.01 - 0.33).

4. Discussion

Overall the test results suggest that, compared to healthy controls, individuals with cancer increasingly rely on their spiritual beliefs and congregational support to assist them in adjusting emotionally to their disease. This finding is generally consistent with previous studies utilizing the BMMRS with TBI, stroke, and SCI samples [13-15]. Specifically, the cancer group reported significantly higher levels of Daily Spiritual Experiences and Religious Support than the healthy controls. Although non-significant, the results in Table 2 indicate that there was also a trend for the participants with cancer to report higher levels of spiritual beliefs, religious practices, and congregational support than the healthy controls on the majority of BMMR subscales (i.e., Forgiveness, Religious/Spiritual Coping, Private Religious Practices). These findings are generally consistent with previous research which indicates that individuals with cancer increasingly rely on their beliefs, their rituals, and their fellow congregants to assist them in coping with their disease and its impact on their lives. It is noted that the Organizational Religiousness subscale was the only BMMRS subscale which was lower for the cancer group (i.e., they report attending religious services less frequently), although this may be related to the fact that individuals with cancer are less physically healthy (as indicated in Table 2), and as a result are less able to attend religious activities at their respective centers of worship.

Although non-significant, the correlations also suggest that individuals with cancer tend to rely on spiritual, religious, and congregational support factors primarily to

Table 2. Group differences in BMMRS and SF-36 variables.

Table 3. Pearson R-value (p-value) among BMMRS and SF-36 Variables for Cancer Group.

help them emotionally cope with their disease. Specifically, Table 3 indicates that the BMMRS variables are more strongly correlated with the SF-36 General Mental Health scale, compared to the General Health Perception scale. This finding is generally consistent with research which suggests that individuals rely on spiritual and religious factors to cope with disease, and to provide meaning and perspective to the illness process [7,9,10,19]. It is likely that the physical effects of cancer may be so significant that spiritual beliefs, religious practices, nor social support can improve physical health status.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, the study was cross sectional and longitudinal studies are needed to determine the specific mechanisms by which these variables impact health. In addition, the sample size was small as the primary purpose was exploratory and hypothesis generating. Increasing sample size may lead to statistically significant findings in the future. Limitations in the ability to use the control group are also noted given that the cancer group was significantly older, had a significantly larger proportion of women, and had a larger proportion being married and of higher educational level. Future studies will also benefit from investigating types of cancer, as well as disease stage.

REFERENCES

- Fetzer Institute and National Institute on Aging Working Group, “Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research,” Fetzer Institute, Kalamazoo, 1999.

- H. G. Koenig, M. McCullough and D. B. Larson, “Handbook of Religion and Health,” Oxford University Press, New York, 2001. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195118667.001.0001

- R. A. Hummer, R. G. Rogers, C. B. Nam and C. G. Ellison, “Religious Involvement and U.S. Adult Mortality,” Demography, Vol. 36, No. 2, 1999, pp. 273-285. doi:10.2307/2648114

- D. Oman, J. H. Kurata, W. J. Strawbridge and R. D. Cohen, “Religious Attendance and Cause of Death over 31 Years,” International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2002, pp. 69-89. doi:10.2190/RJY7-CRR1-HCW5-XVEG

- R. C. Byrd, “Positive Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer in a Coronary Care Unit Population,” Southern Medical Journal, Vol. 81, No. 7, 1988, pp. 826-829. doi:10.1097/00007611-198807000-00005

- W. S. Harris, M. Gowda, J. W. Kold, C. P. Strychacz, J. L. Vacek, P. G. Jones, et al., “A Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Effects of Remote, Intercessory Prayer on Outcomes in Patients Admitted to the Coronary Care Unit,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 159, No. 19, 1999, pp. 2273-2278.doi:10.1001/archinte.159.19.2273

- L. H. Powell, L. Shahabi and C. E. Thoresen, “Religion and Spirituality,” American Psychologist, Vol. 58, No. 1, 2003, pp. 36-52. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.36

- H. C. Kung, D. L Hoyert, J. Xu and S. L. Murphy, “Deaths: Final Data for 2005,” National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 56, No. 10, 2008, pp. 1-121. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr56/nvsr56_10.pdf

- J. C. Holland, S. Passik, K. M. Kash, S. M. Russak, M. K. Gronert, A. Sison, et al., “The Role of Religious and Spiritual Beliefs in Coping with Malignant Melanoma,” Psycho-Oncology, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1999, pp. 14-26. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199901/02)8:1<14::AID-PON321>3.0.CO;2-E

- A. J. Weaver and K. J. Flannelly, “The Role of Religion/Spirituality for Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers,” Southern Medical Journal, Vol. 97, No. 12, pp. 1210-1214. doi:10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146492.27650.1C

- R. P. Sloan, E. Bagiella and T. Powell, “Religion, Spirituality and Medicine,” The Lancet, Vol. 353, No. 9153, 1999, pp. 664-667. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07376-0

- B. Johnstone, D. P. Yoon, K. L. Franklin, L. H. Schopp and J. Hinkebein, “Reconceptualizing the Factor Structure of the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/ Spirituality,” Journal of Religion and Health, Vol. 48, No. 2, 2009, pp. 146-163. doi:10.1007/s10943-008-9179-9

- B. Johnstone, D. P. Yoon, J. Rupright and S. Reid-Arndt, “Relationships among Spiritual Beliefs, Religious Practices, Congregational Support, and Health for Individuals with Traumatic Brain Injury,” Brain Injury, Vol. 23, No. 5, 2009, pp. 411-419. doi:10.1080/02699050902788501

- B. Johnstone, K. L. Franklin, D. P. Yoon, J. Burris and C. L. Shigaki, “Relationships among Religiousness, Spirituality, and Health for Individuals Surviving a Stroke,” Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2008, pp. 308-313. doi:10.1007/s10880-008-9128-5

- K. L. Franklin, D. P. Yoon, M. Acuff and B. Johnstone, “Relationships among Religiousness, Spirituality, and Health for Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury,” Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2008, pp. 76-81. doi:10.1310/sci1402-76

- D. Cohen, D. P. Yoon and B. Johnstone, “Differentiating the Impact of Spiritual Experiences, Religious Practices, and Congregational Support on the Mental Health of Individuals with Heterogeneous Medical Disorders,” International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2009, pp. 121-138. doi:10.1080/10508610802711335

- J. Campbell, D. P. Yoon and B. Johnstone, “Determining Relationships between Physical Health and Spiritual Experience, Religious Practices, and Congregational Support in a Heterogeneous Medical Sample,” Journal of Religion and Health, Vol. 49, No. 1, 2010, pp. 3-17. doi:10.1007/s10943-008-9227-5

- J. E. Ware, M. Kosinski and B. Gandek, “SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide,” QualityMetric Incorporated, Boston, 2000.

- R. A. Schnoll, L. L. Harlow and L. Brower, “Spirituality, Demographic and Disease Factors, and Adjustment to Cancer,” Cancer Practice, Vol. 8, No. 6, 2000, pp. 298-304. doi:10.1111/j.1523-5394.2000.86006.pp.x

NOTES

*Corresponding author.