American Journal of Industrial and Business Management

Vol.4 No.3(2014), Article ID:43941,14 pages DOI:10.4236/ajibm.2014.43021

Learning, Lending, and Laws: Banks as Learning Organizations in a Regulated Environment

Marissa Martineau, Kelly Knox, Paul Combs

School of Business Administration, Marymount University, Arlington, USA

Email: pcombs@marymount.edu

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 3 January 2014; revised 3 February 2014; accepted 10 February 2014

ABSTRACT

The concept of American banks as the most innovative in the world is difficult to reconcile with the reality that banking in the US is also a highly regulated industry with detailed and focused regulators and whose rules and regulations are constantly changing. While innovation inherently entails a need for freedom to experiment, laws and regulations inherently entail a certain degree of constraint. On the one hand, organizational learning may be defined as the ability of an organization to gain insight and understanding from experience through experimentation, observation, analysis, and a willingness to examine both successes and failures. On the other hand, a common goal of bank regulation is to prevent failures from ever occurring in the first place, and although in recent decades there has been significant deregulation in many industries, a sector that remains heavily regulated is banking. This paper examines the adequacy and applicability of Peter Senge’s theory of a learning organization’s five disciplines to the banking industry, the role of laws and regulations in promoting or discouraging US banks to become learning organizations, and recommendations for steps that US banks may take towards becoming learning organizations.

Keywords:Learning Organization; Banking; Regulated Environment

1. Introduction

“Money alone sets the whole world in motion,” wrote a Latin author of maxims in the 1st century B.C. [1] . Today, more than two thousand years later, the flow of money remains an important topic in today’s American society, as evidenced by a February 2012 Gallup poll which found that more than 9 in 10 US registered voters say the economy is extremely (45%) or very important (47%) to their vote in this year’s presidential election [2] . As financiers of the largest economy in the world, “it is little wonder that banks in the United States have gained substantial importance in the global financial market. They offer the widest range of products and services globally, ranging from personal to small business, corporate and institutional banking… US banks are the largest and most innovative in the world [3] .” Indeed, “learning to learn is about innovation and creativity, designing the future rather than merely adapting to it [4] .” As “learning to learn” is typically considered an inherent goal of a learning organization, one might logically conclude that US banks may be considered learning organizations.

But is this conclusion consistent with the actual experience of US banks? In the first place, “just what constitutes a ‘learning organization’ is a matter of some debate [5] .” Identifying learning organizations within any industry remains particularly challenging when the notion of a learning organization remains so ill defined. Moreover, the concept of US banks as the “most innovative in the world [6] ” is difficult to reconcile with the reality that banking in the US is also “a highly regulated industry with detailed and focused regulators... the rules and regulations are constantly changing [7] .” While innovation inherently entails a need for freedom to experiment, laws and regulations inherently entail a certain degree of constraint. On the one hand, organizational learning may be defined as the “ability of an organization to gain insight and understanding from experience through experimentation, observation, analysis, and a willingness to examine both successes and failures [8] .” On the other hand, a common goal of bank regulation is preventing failures from ever occurring in the first place, and although “in recent decades there has been significant deregulation in many industries, a sector that remains heavily regulated is banking [9] .”

This paper seeks to examine the adequacy and applicability of Peter Senge’s theory of a learning organization’s five disciplines to the banking industry, the role of laws and regulations in promoting or discouraging US banks to become learning organizations, and recommendations for steps that US banks may take towards becoming learning organizations.

1.1. Defining a Learning Organization

Even the team of authors of The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization admits that their publication includes “no excellent learning companies, no sterling wunder-orgs that do everything so well that the rest of us need only benchmark and copy them [10] .” How, then, can a learning organization be defined? According to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), a learning organization is “an organization that has developed a continuous ability to learn, adapt and change [11] .” It “is the term given to a company that facilitates the learning of its members and continuously transforms itself [12] .” It is true that employees at many organizations may be confronted by opportunities to learn throughout the course of their daily work. It is also true that external forces may bring about the need for an organization to change on any number of levels. These factors alone, however, are insufficient for an organization to be accurately labeled a learning organization. “Traditional organizations change by reacting to events. Their ‘reference points’ are external and often based in the past or on the competition. They are often change-averse. Learning organizations, by contrast, are vision-led and creative. Their reference points are internal and anchored in the future they intend to create. They embrace change rather than merely react to it [13] .” “A learning organization actively creates, captures, transfers, and mobilizes knowledge to enable it to adapt to a changing environment… a learning organization does not rely on passive or ad hoc process in the hope that organizational learning will take place through serendipity or as a by-product of normal work. A learning organization actively promotes, facilitates, and rewards collective learning [14] .”

1.2. Senge’s Five Disciplines and the Banking Industry

The core ideas about learning organizations developed in Peter Senge’s bestselling classic, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, many of which seemed radical when first published in 1990, have since then become deeply integrated, in general terms, how people see the world and, more specifically, how management techniques are practiced. The book helped give voice to a “wave of interest [in the idea of a learning organization] by presenting the conceptual underpinnings of the work of building learning organizations [10] .” According to The Fifth Discipline, a learning organization exhibits five main characteristics:

2. Systems Thinking

Systems Thinking is a conceptual framework that allows people to study businesses as bounded objects, “bounded by invisible fabrics of interrelated actions, which often take years to fully play out their effects on each other [15] .” It is the process of understanding how things influence one another within a whole, and it concerns an understanding of a system by examining the linkages and interactions between the elements that compose the entirety of the system. In organizations, systems consist of people, structures, and processes that work together to make an organization healthy or unhealthy [16] . The meaning of systems thinking may be more clearly understood in contrast to its opposite: analysis, which is “the separation of an intellectual or material whole into its constituent parts for individual study. While analysis favors breaking down a whole into fundamental parts for study or identifying the root cause of a problem, systems thinking proposes study of parts not in isolation but in seamless interconnectedness with others and with the whole [17] .” Systems thinking propagates that the whole is not merely the sum of parts, but much more. Learning organizations use systems thinking when assessing their company and have information systems that measure the performance of the organization as a whole, and of its various components.

Is systems thinking widely practiced within the banking industry? One bank management consultant, Tripp Babbitt, stated it aptly: “Banks are built on command and control thinking with the workers working and the managers managing; this presents a missed opportunity. Most bankers in management have ‘done the work of a teller’ at one point in their career. But things change and without a thorough understanding of the work as it is done today, wrong or poor decisions are made. Banking management needs to be on a constant vigil to understand the work [18] .” John Blakely and Ian Day, authors of Where Were All the Coaches When the Banks Went Down?, view a generalized lack of this awareness as the major cause of a breakdown of trust in the whole banking system, saying that “In a sense no one person was responsible for this ‘crunch’ but, in another sense, all participants in the system were equally responsible [19] .” Even so, some banks have undertaken efforts to address the aforementioned issues and develop a stronger systems perspective. The Professional Practice for Sustainable Development (PPSD), a project devoted to promoting sustainable practice among professionals, uses the concept of systems thinking to educate the financial services sector about the application of sustainable development to professional practice. In addition to serving as a basis for the link between sustainable development and corporate social responsibility, PPSD views the banks themselves as systems, with “a range of stakeholders in the process of a range of financial transactions (current accounts, dividends, salaries, savings, loans, mortgages, investment, etc.) [20] ,” and seeks to raise the banks’ awareness of themselves as such. “Where the Rubber Meets the Road,” a Bank of America study to evaluate transition processes in its California Northwest region, criticized executives who were “familiar with only one transformation segment each, and grasp(ed) what need(ed) to be done but not necessarily why.” The study revealed a need for broader, systems-focused thinking, to “identify and understand needs of all stakeholders… look beyond the ‘usual suspects’ (customers, associates, stockholders),” and also “develop an ‘all hands’ mentality through a culture of open communication [21] .”

3. Mental Models

Mental models are “deeply ingrained assumptions, generalizations, or even pictures of images that influence how we understand the world and how we take action [10] .” They are “an explanation of someone’s thought process about how something works in the real world… a representation of the surrounding world, the relationships between its various parts and a person’s intuitive perception about his or her own acts and their consequences.” A mental model is a kind of internal symbol or representation of external reality, hypothesized to play a major role in cognition, reasoning and decision-making [22] . Confronting the existence of mental models in a learning organization “involves each individual reflecting upon, continually clarifying, and improving his or her internal pictures of the world, and seeing how they shape personal actions and decisions [23] .” Indeed, the importance of questioning ones assumptions about people resonates not only with many human resources professionals, but also with many thoughtful people in general, in order to avoid biases and discrimination. Senge, however, takes this idea further and argues that individuals in a learning organization need to question all of their mental models, such as what can or cannot be done in different management situations, what happens in various markets, what happens with the economy, and the like.

Do certain mental models significantly impact the financial sector? For one contributor to the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, Kevin T. Jackson, the answer is a resounding “yes [24] .” Jackson states that “the mental models of economics, business management, and law have equipped us with knowledge to comprehend and to manage, albeit in an imperfect and limited way, complex financial systems and institutions,” and that indeed any meaningful discussion, say, of the 2008 financial crisis must be grounded in these mental models. In simplest terms, he explains that the prevailing mental model of the economist inclines him to look for mathematical formulas, that the business management theorist leads him to seek causal scientific explanations, and that the legal expert inclines him to suggest new laws and policies to “fix” the problem at hand. While some may or may not find Jackson’s subsequent harsh critique of the inadequacy of three approaches to be debatable, his identification of the existence of prevailing mental models within the financial sector remains accurate. Similarly, economist Thomas D. Willett argues that “the current global financial crisis that started in the US subprime market was to a considerable extent the result of deficient mental models or beliefs by many actors in both the public and private sectors [25] ;” specifically, beliefs that home prices never fall, and that market discipline would automatically lead to self-regulation of the financial markets so that little regulatory oversight was needed. Willett’s conclusion is that “efforts to correct the defective mental models… can make an important contribution to improving financial regulation and the soundness of financial systems [25] . Moreover, authors Yoram (Jerry) Wind and Colin Crook of the Rotman School of Management go as far as to characterize the financial crisis of 2008 as “of the best possible examples of the dangers posed by narrow mental models,” as “some of the most basic assumptions implicit in the prevailing worldview before the collapse, such as ever-rising home prices and stock markets, were patently false, but this mindset was so powerful that by and large, objections were not raised [26] .” Underlying causes of the 2008 financial crisis may be widely and hotly debated, and perhaps no general consensus on the matter may ever be reached, lending credence to George Bernard Shaw’s saying that “If all the economists were laid end to end, they’d never reach a conclusion [27] .” Despite the wide variety of perspectives on causes, an increased awareness of the existence of mental models within the financial sector is clearly noticeable.

4. Building Shared Vision

Building shared vision in practice “involves the skills of unearthing shared ‘pictures of the future’ that foster genuine commitment and enrollment rather than compliance… when there is a genuine vision (as opposed to the all-too-familiar ‘vision statement’), people excel and learn, not because they are told to, but because they want to [16] .” A shared vision emerges from the intersection of personal visions and helps create a sense of commitment to the long term. However, there is more to a shared vision than just this convergence of personal visions. Vision is only truly shared “when people are committed to one another having it, not just each person individually having it. There needs to be a sense of connection and community with respect to the vision that provides the focus and energy for learning in learning organizations. It is the commitment to support each other in realizing the shared vision that gives the vision power. Furthermore, it supplies the guiding force that enables organizations to navigate difficult times and to keep the learning process on course [28] ”. While “fostering genuine commitment” may seem a daunting task, a leading business strategy and management consulting company concluded that shared vision is not merely an ideal for which to strive, but an essential element of charting a company’s course: “Without a shared vision, a business will take indirect and meandering paths towards growth and prosperity. The missed opportunity to set and control the business’s own direction will leave it to fate and the actions of competitors to determine the organization’s destiny [29] .”

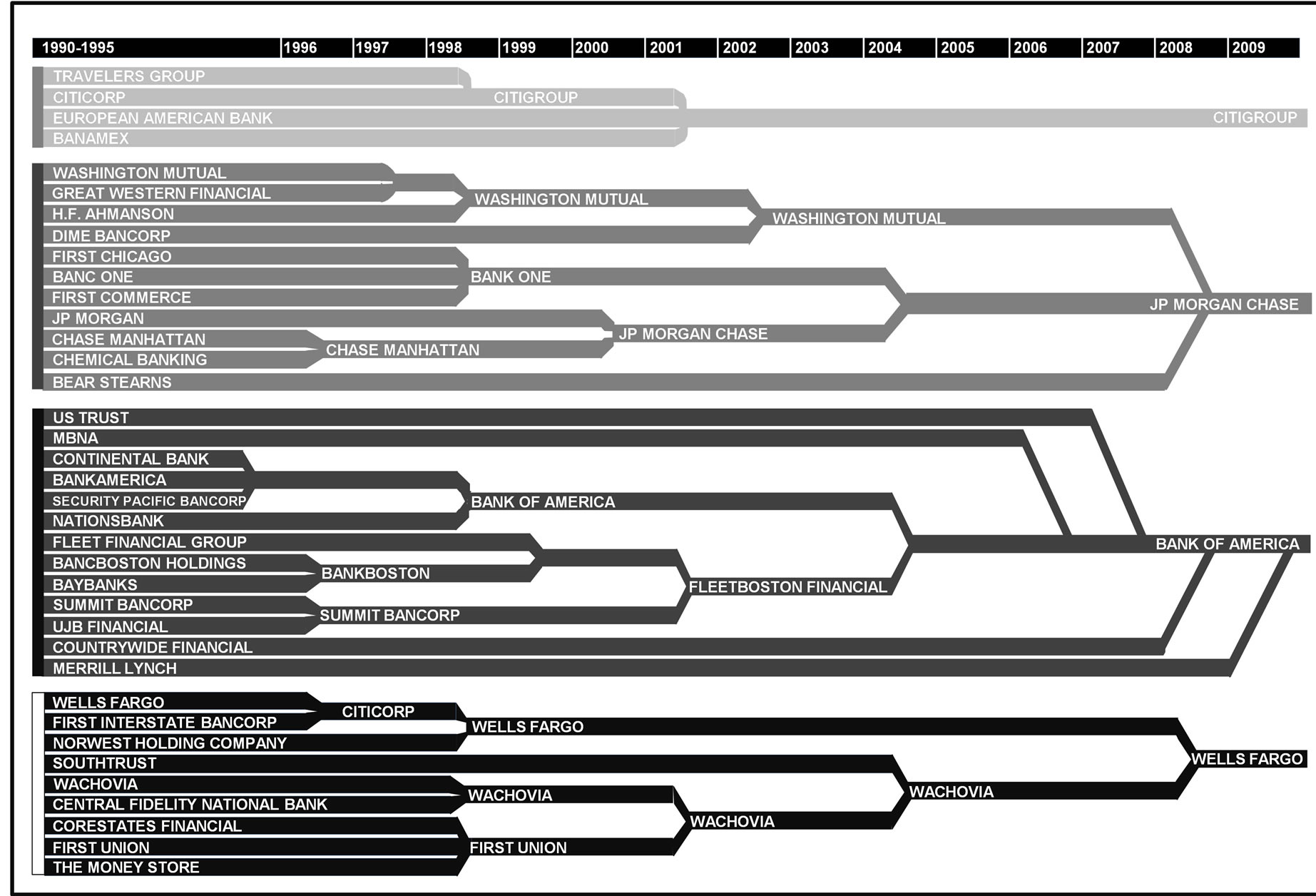

While Senge recognizes that simply having a vision statement is not necessarily evidence of genuine shared vision in an organization, all of the ten largest US banks [30] do indeed have a vision statement. The largest, Bank of America, with 12.62 percent of the nation’s deposit share as of June 30, 2012 [31] , makes a very direct and concise statement on its web site: “Our vision is to become the world’s finest financial services company [32] .” The second largest, Wells Fargo, with 9.96 percent of the nation’s deposits, also limits its vision statement to a single sentence: “We want to satisfy all our customers’ financial needs and help them succeed financially [33] .” For both of these banks, as well as the third and fourth largest (JP Morgan Chase and Citibank, respectively), mergers and acquisitions played a highly significant role in growth, as illustrated in Figure 1 [34] .

In a study of the causes and effects of mergers and acquisitions, capitalization on opportunities for organizational learning was found to be strength of an acquisition growth strategy. The study’s authors found that the “rationale for acquisitions formation is consistent with a growing body of research that suggests that firms enhance their competitive position through superior knowledge... Firms place a high priority on the acquisition as a way to achieve technical skills or technological capabilities. It is often difficult for a firm that does not have a particular skill to buy it in the marketplace, because knowledge is often tacit and difficult to price. A firm that

Figure 1. Mergers and consolidations in American banking.

wants to learn a particular skill often stands a better chance of accomplishing its objective acquiring a firm that is exemplary in that area [35] .” While these principles may be true for numerous acquisitions in multiple industries, however, they do not necessarily apply to mergers of companies within the highly regulated banking industry, where one bank may seek to acquire another for reasons far different than the advancement of skills. Since the Department of the Treasury issued a new tax law in 2008 [36] , a bank that acquires another is allowed to use some of the unrecognized losses of the bank it acquires to offset its own revenues for tax purposes. That lowers the tax liability of the merged bank. Before the notice was issued, the merged bank could write off only a limited amount of the losses. The notice removed those restrictions, enabling the struggling acquired institutions to avoid penalties from regulatory non-compliance, and the acquiring banks to make huge reductions in their tax liabilities while gaining new accounts, assets, and locations (and often experienced employees to staff them). Indeed, “plenty of investors are interested in scooping up distressed banks [37] .” Yet, in the eyes of many, a result of multiple acquisitions throughout time is that a sense of shared vision is greatly diluted: “Banks, like so many other businesses… have lost their identities as one after another are bought up by interests far from the community they serve. There’s a lot lost in consolidation [38] .” Shared vision often suffers in the “typical merger phenomenon of team members who are very participatory versus others who feel ‘acquired’ and consequently fearful and silent [39] .” While leaders of acquired banks may tout recapitalization and regulatory approval, a vision of the future may not be shared by their employees. To be sure, the discipline of “building shared vision” presents challenges that are unique to the banking industry.

5. Personal Mastery

Personal mastery is the commitment of an individual to the process of learning. Senge states that it is “the discipline of continually clarifying and deepening our personal vision, of focusing our energies, of developing patience, and seeing reality objectively. As such, it is an essential cornerstone of the learning organization, the learning organization’s spiritual foundation” [16] . While the aforementioned characteristic of systems thinking focuses on the organization as a whole rather than its individual components, the discipline of personal mastery is more heavily dependent upon the behavior, dedication and engagement of the individual employees. Organizations must have “people at all levels capable of personal mastery in order to become successful learning organizations. It is important to remember, however, that this is a matter of choice. It cannot be dictated from on high [40] .” In other words, personal mastery is not a means of developing people towards organizational ends but rather an agreement between the people and the organization [41] ; it cannot be enforced, but only encouraged. A learning organization can facilitate personal mastery by creating an environment conducive to individual pursuits, through encouraging inquiry and curiosity, challenging the status quo, changing assumptions about what motivates employees, examples set by the leaders, and long-term commitment [40] . Nevertheless, a learning organization has been described as the “sum of individual learning, but there must be mechanisms for individual learning to be transferred into organizational learning [42] .” New information systems may be needed to make better data available and to disseminate it. As one wise human resources practitioner observed, “In a sense ‘organizations’ do not learn, the people in them do, and individual learning may go on all the time. What is different about a learning organization is that it promotes a culture of learning, a community of learners, and it ensures that individual learning enriches and enhances the organization as a whole. There can be no organizational learning without individual learning, but individual learning must be shared and used by the organization [23] .” Indeed, “Learning is much more than simply acquiring information. ... Information needs to be transformed into knowledge, then knowledge must be transformed into action, and then again into wisdom [43] .”

Wise bank leaders recognize that “promoting personal mastery is an effective way to strengthen commitment and with such, employees are less likely to transfer to other banks” [44] after the company has invested resources into training them. One example of a bank that promotes personal mastery is Umpqua Bank, which sends its employees from all levels to Ritz-Carlton Hotels’ customer service class as a regular part of its training curriculum. Post-participation feedback indicates a sense of feeling “invigorated,” “energized,” and wanting “to share the mission statement and keys to our culture with fellow associates again and to continue to do it more on a regular basis [45] ,” thus surpassing basic imparting of knowledge to employees, and reaching a true desire to learn, share knowledge, and perform to the utmost of their abilities. Likewise, Goldman Sachs also fosters personal mastery as much as possible, as stated on its web site: “we recognize that learning is a competitive advantage, and we are committed to helping our people reach the peak of their capabilities [46] .” To this end, the company does not merely leave the task of promoting learning to individual employees, teams, and supervisors: instead, it has created and filled a highly competitive position of Chief Learning Officer, who must recognize that “Goldman Sachs is becoming a larger, more global firm, and those changes require a change in the skills and leadership of the workforce [47] ,” which should be proactively initiated before it is forced upon the organization. Each new employee’s orientation begins prior to his or her first day in the office, the internal training and development program “Goldman Sachs University” offers courses for every stage of career development, and 360-degree feedback is not only used, but also taught and incorporated into each employee’s professional development plan. Ironically, despite excellent initiatives to foster personal mastery, Goldman Sachs is said to have “ignited a firestorm of public outrage [48] ,” caused “Senators from both sides of the aisle [to express] emotions ranging from disgust to utter frustration [49] ,” and been called “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money [50] ,” as internal emails confirmed that Goldman Sachs “was making tens of millions of dollars of profits daily by betting against its own clients’ investments [51] ,” and then accepted “bailout” funds from the US federal government in the aftermath of the financial crisis that it had helped to create. Interestingly, in 2006, just a few years prior to the recent financial crisis, Investment Dealers’ Digest highlighted investment bankers’ strong interest and participation in a Columbia Business School Course taught by Srikumar Rao, with an objective of learning “how to be more creative, ethical, and ‘vibrantly alive’” (emphasis added), and former students indicate higher levels of personal mastery, saying that “after taking the class, they have felt more fulfilled at their job and better able to serve their clients [52] .” Goldman Sachs was both ranked among both the “100 Best Companies to Work For” [53] and the “The 10 Most Hated Companies in America” for 2011 [54] . This dual perception suggests that personal mastery alone, in the absence of the aforementioned discipline of building shared vision with broader society, may contribute to doing more harm than good for a company’s reputation, and for the economy of which it is a part.

6. Team Learning

Team learning is the process of working collectively to achieve a common objective in a group. In the learning organization context, team members tend to share knowledge and complement each others’ skills [55] . Senge writes that “when teams are truly learning, not only are they producing extraordinary results, but the individual members are growing more rapidly than could have occurred otherwise.” When dialogue between team members is joined with systems thinking, Senge argues, there is the “possibility of creating a language more suited for dealing with complexity, and of focusing on deep-seated structural issues and forces rather than being diverted by questions of personality and leadership style [56] .” Indeed, such is the emphasis on dialogue in his work that it could almost be put alongside systems thinking as a central feature of his approach. Contributors to The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook state that team learning is not team building, which they describe as creating courteous behaviors, improving communication, becoming better able to perform work tasks together, and building strong relationships [10] . Rather, it is “the process of aligning and developing the capacity of a team to create the results its members truly desire. It builds on the discipline of developing shared vision. It also builds on personal mastery, for talented teams are made up of talented individuals.” [16] .

While team learning may or may not be a widespread concept across the entire banking industry, some banks recognize its value, such as Dr. Martin Moehrle, Chief Learning Officer for Deutsche Bank, where global business functions and learning/development have been integrated under one roof. Says Moehrle, “It’s not just a community where people try to work on a knowledge database and leverage each other’s experiences and talk a little bit with each other. Now, they are forced to work from the same platform, to join a meeting every quarter, to join regular calls with the management team and to decide jointly and accept the decisions that are relevant for the whole enterprise, which makes these meetings certainly more heated than if you left everybody in his or her world alone [57] .” World Bank Group President Dr. Jim Yong Kim also exemplifies an understanding of team learning, and stated that there are “a lot of new insights in how matrix organizations and systems can work more effectively together. So I would just say this is at the very top of my priority list. You know, I’m also the first Bank president to ever have run a knowledge institution before. So I would come to this job with a lot of ideas about how to manage knowledge, about how to make it effective and be present where we need it. But the key to doing that is to have a lot of great people who actually have knowledge, and the good news is we have plenty of those [58] .” Even the aforementioned Goldman Sachs aims to “systematically and quickly make available the best ideas and products from one area of the firm across the whole organization [59] .” A bank need not be enormous, however, to develop team learning. First steps toward developing this learning organization discipline could simply include the practice of Lidia Kwiatkowska, manager at the Bank of Montreal/Harris, who holds a weekly staff meeting for employees to talk about how they delivered their best customer service that week [60] .

6.1. Short-Term Reactions, Long-Term Effects: Key US Banking Laws and Regulations in the Mid to Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries

In The Fifth Discipline, Senge acknowledges Jay Forrester’s development of the concept of “system dynamics,” and states “the causes of many pressing public issues, from urban decay to global ecological threat lay in the very well-intentioned policies designed to alleviate them [16] .” Admittedly, popular outrage at the “bailout” that granted millions of taxpayer dollars to banks in order to stabilize the economy amidst a financial crisis demands some sort of response from lawmakers and government. Whether or not additional laws and regulations will do more good than harm, however, remains a controversial topic. Additional oversight of the entities that were most directly involved in the causes of the crisis may appear at first glance a logical and critical next step. Upon further examination, though, many would argue that from the stock market crash in 1929 to the financial crisis of 2008, lawmakers have been “lured into interventions that focused on obvious symptoms and not underlying causes, which produced short-term benefit but long-term malaise, and fostered the need for still more symptomatic intervention [16] .”

While newsworthy events in recent memory have prompted a sharp increase in the quantity and complexity of the laws, rules, and regulations that govern the banking industry, one must bear in mind that these represent a shift in direction and volume, not a beginning. The “most important federal legislation relating to the financial community since the 1930s [61] ” (at the time) was the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 (DIDMCA), put forth by President Jimmy Carter. This Act increased federal deposit insurance from $40,000 to $100,000 at commercial banks, savings banks, savings and loan associations and credit unions. It also began to phase out Regulation Q, which had prohibited banks from being able to pay interest on deposits within checking accounts. This Regulation Q had been enacted in accordance to the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, to “limit loan sharking and other such unseemly actions [62] .” In addition, it motivated consumers to release funds from these accounts and put them into money market funds. The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 (DIDMCA) is made up of nine titles, none of which were without the precedent of existing conditions which deregulation was designed to address.

Two years later, the Garn St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 was passed in order “to revitalize the housing industry by strengthening the financial stability of home mortgage lending institutions and ensuring the availability of home mortgage loans [63] .” Upon signing this Act, President Ronald Reagan stated, “This bill is the most important legislation for financial institutions in the last 50 years. It provides a long-term solution for troubled thrift institutions. It’s pro-consumer, granting small savers greater access to loans, a higher return on their savings. And when combined with recent sharp declines in interest rates, it means help for housing, more jobs, and new growth for the economy [64] .” The Act expanded the powers of thrift institutions by permitting the industry to make commercial loans and increase their consumer lending, and reduced their exposure to changes in the housing market and in interest rate levels. Supporters of the Garn St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 believed that this would in turn make the thrift industry a “stronger, more effective force in financing housing for millions of Americans in the years to come [64] .”

The 1980s brought still more significant new laws to govern the banking industry. In 1987, it was the Competitive Equality Banking Act—“to regulate nonbank banks, impose a moratorium on certain securities and insurance activities by banks, recapitalize the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation, allow emergency interstate bank acquisitions, streamline credit union operations, regulate consumer checkholds, and for other purposes [65] .” Yet, as thrifts did not actually become stronger but ultimately failed, in response in 1989, the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (FIRREA) was passed—“to reform, recapitalize, and consolidate the Federal deposit insurance system, to enhance the regulatory and enforcement powers of Federal financial institutions regulatory agencies, and for other purposes [66] .” Also in response to the failure of thrifts, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991 (FDICIA) was passed—“to require the least-cost resolution of insured depository institutions, to improve supervision and examinations, to provide additional resources to the Bank Insurance Fund, and for other purposes [67] .”

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) is another debatable law, with plenty of opinions both pro and con. Originally passed in 1977 in response to national pressure to address the deteriorating conditions of American cities, in 1993 President Bill Clinton requested that regulators reform the CRA in order to make examinations more consistent, clarify performance standards, and reduce cost and compliance burden, and in 1995, the final amended regulations replaced the existing CRA regulations in their entirety. While seemingly well-intentioned, critics argue that what resulted was “the US government’s push… to have banks lend money to low-income people who would, in many cases, have a slim chance of repaying the loans [68] .” To enable banks to lend these substantial funds, federal regulators held up approval of bank mergers and acquisitions. Also in 1995, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development ordered two government-sponsored enterprises, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, to direct 42 percent of their mortgage financing to lowand moderate-income borrowers. In 1997, to help achieve that goal, Fannie Mae introduced a three-percent-down mortgage (the traditional mortgage had required a twenty-percent down payment) [68] . With only three percent down, an owner whose house value fell only a bit below the original price would be tempted to walk away from it. The housing crisis caused huge losses for Fannie Mae, and the federal government then “bailed them out.” This reality, opponents argue, together with an over-reliance on high ratings given to mortgage-backed securities, was a contributing factor toward the later 2008 economic collapse. Supporters of the Community Reinvestment Act, however, argue it was actually a lack of regulation that caused the mortgage crisis. They also state that loans made as a result of the Community Reinvestment Act are not the problem loans that brought down the economy, and that “subprime mortgages that are now defaulting in droves were made mostly by unregulated mortgage bankers with no CRA obligations or oversight…the mortgages that are a major part of the crisis were made mostly to middle-and upper-income borrowers who didn’t want to verify income or wanted a bigger loan than a prime lender would offer [69] .”

In response to the economic collapse of 2008, and government “bailout” which provided survival funds to banks that had been supposedly “too big to fail,” President Barack Obama signed The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act into federal law on July 21, 2010. This act brought “the most significant changes to financial regulation in the United States since the regulatory reform that followed the Great Depression... It made changes in the American financial regulatory environment that affect all federal financial regulatory agencies and almost every part of the nation’s financial services industry [70] .” The Dodd-Frank Act, for all intents and purposes, repealed Regulation Q and allowed for banks to offer interest on checking accounts for it business-banking customers. This move was made, in part, to increase banking reserves to militate against credit illiquidity that was experienced in the initial days of the 2008-2009-credit crisis. Moreover, it also imposed numerous regulations on Wall Street [71] .

Finally, any discussion of recent laws governing the US banking industry would be incomplete without mention of the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act—more commonly known by its acronym, the US Patriot Act. This act was passed in direct response to the terrorist attacks on the United States soil on September 11, 2001, and its sections that affect financial institutions may be summarized in the following four points [72] :

1) To strengthen US measures to prevent, detect and prosecute international money laundering and financing of terrorism;

2) To subject to special scrutiny foreign jurisdictions, foreign financial institutions, and classes of international transactions or types of accounts that are susceptible to criminal abuse;

3) To require all appropriate elements of the financial services industry to report potential money laundering;

4) To strengthen measures to prevent use of the US financial system for personal gain by corrupt foreign officials and facilitate repatriation of stolen assets to the citizens of countries to whom such assets belong.

The Patriot Act also engulfed the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), which was passed in the 1970s. The BSA requires financial institutions in the United States to assist US government agencies to detect and prevent money laundering. Specifically, the act requires financial institutions to keep records of cash purchases of negotiable instruments, and file reports of cash purchases of these negotiable instruments of more than $10,000 (daily aggregate amount), and to report suspicious activity that might signify money laundering, tax evasion, or other criminal activities. These practices demonstrate how existing knowledge was used to address new concerns.

6.2. Five Disciplines, Hundreds of Laws and Regulations: What Really Facilitates Learning?

Senge writes, “Generative learning cannot be sustained in an organization if people’s thinking is dominated by short-term events. If we focus on events, the best we can ever do is predict an event before it happens, so that we can react optimally. But we cannot learn to create [16] .” Unfortunately, this reactive type of thinking appears all too common with regard to banking legislation. Most regulations go hand-in-hand with occurrences. In the early 1980s banking regulations were shaped by two factors: a reaction to the failure of the thrift industry, and a reaction to changes in banking occurring in since the 1960s. Senge himself uses an example from the financial sector to illustrate the shortcomings of a focus on events that leads to event explanations: “‘The Dow Jones average dropped sixteen points today,’ announces the newspaper, ‘because low fourth-quarter profits were announced yesterday.’ Such explanations may be true,” he writes, “but they distract us from seeing the long-term patterns of change that lie behind the events and from understanding the causes of those patterns [16] .” This is in sharp contrast to a learning organization, which places a much stronger emphasis on being forward-thinking. Some would also argue that proactive laws get use into trouble, such as the Community Reinvestment Act of 1995’s possible role in setting up the United States up for the finial crisis of 2008. The cause vs. effect debate of regulation remains ongoing, and may be as impossible to resolve as the question of “which came first, the chicken or the egg?”

Being forward thinking in the banking industry, and exercising systems thinking, can be a great challenge, due to a substantial duty to the public. Money touches every single employment situation, and nearly every aspect of daily life. While a corporation may have a “target market,” the government’s “target market” is everyone, and money is valuable to all. How can one-exercise systems thinking, when the extent of that system’s influence is practically limitless, and touches individuals of nearly every possible sort of mental model? The possibility of inadvertently excluding critical considerations is practically limitless as well. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York does well to identify two themes that make banks different with regards to governance: “the multitude of stakeholders in banks, and the complexity of the business [73] .” Moreover, Congress has had difficulty not only anticipating problems but also addressing issues that legislators and others have recognized as requiring legislative action. As Senge states, “Whether in business or politics, if we simply become more aggressive fighting the ‘enemy out there’ we are reacting [16] .” “Since everything in a global system is inter-connected, solutions are neither simple nor straightforward, but messy and manifold. Solutions will need to have the requisite variety to match the complex, recursive nature of the global financial system itself [74] .”

“Mastery might suggest gaining dominance over people or things. But mastery can also mean a special level of proficiency [16] ,” wrote Senge. Due to the complicated nature of banking-related legislation itself, many in the industry lack even a basic firsthand understanding of what the legislation contains, much less a proficient one. For example, the Dodd-Frank Act alone consumes 848 pages [75] . Not only is it lengthy, it is highly detailed, which makes understanding its contents problematic at best. Consultants and specialists are employed to provide explanations of what bankers need to know in order to perform their jobs in compliance with the law, but little else. The frequency of having a “middleman” reduces effectiveness toward development of learning organizations within the banking industry, as learning organizations favor flatter hierarchical structures and more direct communication.

While a learning organization encourages its members to exercise creativity and to experiment without excessive fear of negative consequences, the consequences of experimentation in financial matters can be dire. When an experiment goes wrong—such as the 2008 financial crisis—laws and regulations follow, and the banks are legally required to comply. Being “creative” can often get a bank in trouble (and the entire economy too), so some banks actually pride themselves in maintaining the familiar expectations of “plain vanilla banking.”

6.3. Recommendations for the Banking Industry to Facilitate Steps towards Transformation into Learning Organizations

As stated in a staff report of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Ideally, the goal would be to gain a robust sense of the role governance plays in risk taking in order to suggest best practices or regulatory guidance. However, the notion of causation is a tricky one: does a given characteristic lead a bank to make risky choices, or does a culture of risk taking lead a bank to have certain characteristics?” Although recommendations for legal and regulatory measures extend far beyond the scope of this article, three recommendations are made for the banking industry to facilitate steps towards transformation into learning organizations, as follows:

1) Designate responsibility for organizational learning and knowledge management. In some successful banks, such as Goldman Sachs, this responsibility lies with the Chief Learning Officer, who is “responsible for the learning structure across all divisions and will direct the Pine Street Leadership Project, the firm’s training and development initiative for its business leaders [76] .” Including a Chief Learning Officer in the company’s organizational hierarchy not only clarifies responsibility for organizational learning, but also serves to legitimize the corporate value of organizational learning itself. In addition, delegating responsibility for learning may take the form of increased use of mentor/mentee programs. “Mentoring programs are growing in number as an effective mechanism to pass on knowledge within organizations,” as evidenced by an empirical investigation in Lebanese banks. These programs consist of a new employee learning “the ropes” from a seasoned employee [77] ; without these programs, the knowledge would be lost if or when the seasoned employee leaves the company or position. Admittedly, some employees want to keep information to themselves, in an attempt to facilitate their own job security and become “irreplaceable” as the only person who knows how to do what he or she does. This possibility suggests the benefit to a bank of having a Chief Learning Officer, to structure and strengthen the pursuit of knowledge, and to ensure that even if the person leaves the bank, that person’s knowledge remains.

2) Engage in direct, ongoing communication between the banks and the legislators, or regulators, or both, and share results of this communication at all levels of the organization. The aforementioned role of Chief Learning Officer demands an understanding of the importance of being proactive, and initiating change before it is forced upon an organization [78] . As most financial institutions or organizations do not have a Chief Learning Officer, however, communication between banks and legislators or regulators or both leaves significant room for improvement. It should be interesting to see if this position is instituted into organizations in the future. Meanwhile, Texas Senator Kirk Watson, who serves on the Business and Commerce Committee and is the founder of an Elgin de novo bank, has a message for bankers: to communicate with legislators and help them understand the industry’s needs. “Don’t assume they are as aware as you want them to be,” he cautioned [79] . Furthermore, communications with legislators/regulators should be shared throughout all levels of the bank. A mandatory annual compliance-training course instructs a bank employee on various regulations to which a bank must conform in its operations [80] . While mandatory trainings generally focus on instructing staff on how to remain in conformity with the law, they generally do little to broaden the employee’s perspective about the context within which the laws were formed, related actions that the financial institution is taking, or how the employees themselves may become involved in the policy-making process. This would be a meaningful step for a bank towards becoming a true learning organization.

This applies to both the individual financial institution level, and the national governmental/economic/societal level. It may be argued that the many rules and regulations for financial institutions only allow them to be involved in what Chris Argyris and Donald Schon call “single-loop learning,” which is “control-oriented and reactive, and it leads to corrective action that appears rational: if one action does not work an alternative course of action is followed [81] .” This is because most of the rules and regulations are reactive in nature. However, financial institutions that seek to become learning organizations would do well to shift their mental model towards “double-loop learning,” which “breaks the cycle of single-loop learning by ‘the detection and correction of errors where the correction requires changes not only in action strategies but also in the values that govern the theory-in-use [82] .’” For example, Walter Wriston, CEO of Citibank from 1970 to 1984, thought that it Citibank could be the world’s largest bank [83] , and he created a sales and service culture. “Citibank thus forged new values for the industry [84] .” Mr. Wriston also pioneered the technology for the automated teller machine (ATM) [83] . Without a shift of mental model from reactiveness to the mental model of the customer perspective, such innovation would never have been possible.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, because banking is highly regulated and affects everyone, it is difficult for banks to become learning organizations. However, some banks are slowly changing their mental models, and are at least showing some aspects of being a learning organization despite ever-changing regulations. As stated in 1982 by the authors of Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life, “it is going to be fascinating to watch how banks react to the deregulation in the industry [84] ,” and we are still watching how banking reacts not only to deregulations, but also to regulations 30 years later. Above all, “we should keep in mind that banking regulations should reflect the state of development in the financial markets, which implies that it is exposed to constant change [85] ,” which a true learning organization will be eager to embrace.

References

- Publilius Syrus. http://www.quotationspage.com/subjects/money/31.html

- Jones, J.M. (2012) Economy Is Paramount Issue to US Voters. Gallup. http://www.gallup.com/poll/153029/Economy-Paramount-Issue-Voters.aspx

- (2010) Economy Watch. http://www.economywatch.com/world_economy/usa/banks-in-usa.html

- David Skyrme Associates (2012) The Learning Organization. http://www.skyrme.com/insights/3lrnorg.htm

- Smith, M.K. (2001) The Learning Organization. The Encyclopedia of Informal Education. http://www.infed.org/biblio/learning-organization.htm

- (2010) Economy Watch. http://www.economywatch.com/world_economy/usa/banks-in-usa.html

- (2012) Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bank

- Malhotra, Y. (1996) Organizational Learning and Learning Organizations: An Overview. http://www.brint.com/papers/orglrng.htm

- Allen, F. and Carletti, E. (2007) What Is the Rationale for Regulating Banks? UniCredit Group: Banking and Finance Monitor, 2. http://finance.wharton.upenn.edu/~allenf/download/Vita/banking%20and%20finance%20monitor%20article.pdf

- Senge, P.M., Kleiner, A., Roberts, C., Ross, R.B. and Smith, B.J. (1994) The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook. Doubleday, New York, 5.

- (2012) Society for Human Resource Management Glossary of Business Terms. http://www.shrm.org/TemplatesTools/Glossaries/BusinessTerms/Pages/l.aspx

- Pedler, M., Burgogyne, J. and Boydell, T. (1997) The Learning Company: A Strategy for Sustainable Development. 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, London.

- Clark, D. (2012) The Learning Organization. http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/leader/learnor2.html

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organizational_learning

- Senge, P.M. (2006) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. Doubleday (A Division of Random House), New York, 7.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Systems_thinking

- Sinha, A. (2012) Systems Thinking—A Beginner’s Quest. http://systemsview.wordpress.com/2010/06/28/4/

- Babbit, T. (2009) Banking—5 Ways to Make Your Operations Profitable. Tripp Babbitt’s Blog. http://blog.newsystemsthinking.com/banking-5-ways-to-make-your-operations-profitable/

- Blakely, D. and Day, I. (2009) Where Were All the Coaches When the Banks Went Down? 121 Partners Ltd. http://www.trainingzone.co.uk/topic/coaching/where-were-all-coaches-when-banks-went-down-part-5-systems-thinking/137496

- Professional Practice for Sustainable Development (2012) Financial Sector Programme—Systems Thinking and the Five Capitals. http://www.pp4sd.org.uk/downloads/pdf/2Systems%20Thinking%20and%20Five%20Capitals.pdf

- Wallance, D. (2011) Transformation at Bank of America: An Enterprise Systems Analysis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 29-32. http://sdm.mit.edu/docs/Wallance%20-%20Thesis%20presentation%20-%20copyright.pdf

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mental_models

- Agarwal, A. (2012) Learning Organization. HR Folks International. http://www.hrfolks.com/articles/learning%20organization/learning%20organization.pdf

- Jackson, K.T. (2010) The Scandal Beneath the Financial Crisis: Getting a View from a Moral-Cultural Mental Model. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, 2010, 736-777. http://www.readperiodicals.com/201004/2045076881.html

- Willett, T.D. (2009) The Role of Defective Mental Models in Generating the Current Financial Crisis. Prepared for the Cornell Workshop on the Global Implications of the Financial Crisis, 1. http://econ.duke.edu/uploads/assets/Workshop%20Papers/Willett.pdf

- Wind, Y. (Jerry) and Crook, C. (2009) From Mental Models to Transformation: Overcoming Inhibitors to Change. Harvard Business Review, 2009, 5. http://hbr.org/product/from-mental-models-to-transformation-overcoming-in/an/ROT081-PDF-ENG

- Shaw, G.B. (2012) Quotes about Economy and Recession. http://www.soundoflife.net/economy-quotes-recession/

- Jacobs, M. (2007) Building Shared Vision: The Third Discipline of Learning Organizations. Systems in Sync, 1. http://www.systemsinsync.com/pdfs/Shared%20Vision.pdf

- Method Frameworks, a Division of Forte Solutions Group (2012) Corporate Strategy: Create a Shared Vision. http://www.methodframeworks.com/blog/2012/corporate-strategy-create-shared-vision/index.html

- Wang, J. (2012) Ten Largest Banks in the US. Bargaineering. http://www.bargaineering.com/articles/ten-largest-banks-in-the-u-s.html

- Dunn, A. (2012) Bank of America Still Tops the US in Deposits. The Charlotte Observer: Bank Watch. http://obsbankwatch.blogspot.com/2012/10/bank-of-america-still-tops-in-us.html

- Bank of America (2012) Our Vision. http://about.bankofamerica.com/en-us/our-story/our-company.html#fbid=7BwpY8OLoIS

- Wells, F. (2012) Our Vision. https://www.wellsfargo.com/invest_relations/vision_values/3

- (2012) http://www.motherjones.com/files/images/big-bank-theory-chart-large.jpg.

- Carbonara, G. and Caiazza, R. (2009) Mergers and Acquisitions: Causes and Effects. Journal of the American Academy of Business, Cambridge, 14, 188-194. http://www.scribd.com/doc/14358472/Cause-and-Effect-of-Mergers-Acquisitions

- (2012) New Tax Law a Windfall for Buyers of Struggling Banks. University of California at Davis, Graduate School of Management. http://gsm.ucdavis.edu/research/new-tax-law-windfall-buyers-struggling-banks

- McGaw, R. (2010) Financiers Eye Struggling Banks; Centennial First Buy. Denver Business Journal. http://www.bizjournals.com/denver/stories/2010/05/17/story8.html?page=all

- Startup Nation (2012) Shared Vision, Not Group-Think: Will Chase. http://www.devsun.startupnation.com/pages/keymoves/shared-vision-will-chase.asp

- The Emerich Group, Inc. (2012) Adams Community Bank: In a Merger State of Mind. 4. http://www.emmerichfinancial.com/CaseStudies/Adams-Case-Study.pdf

- Jacobs, M. (2009) Personal Mastery—The First Discipline of Learning Organizations. http://ezinearticles.com/?Personal-Mastery---The-First-Discipline-of-Learning-Organizations&id=2750492

- (2009) Management Decision Making. http://ivythesis.typepad.com/term_paper_topics/2009/10/management-decision-making.html

- Wikipedia Learning Organization. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Learning_organization#cite_ref-OK_1-14

- (2012) Sober 24. http://www.sober24.com/Recovery_Tools/Moral_Compass/Finding_Your_Moral_Compass/265/vobId__2729/

- (2009) Management Decision Making. http://ivythesis.typepad.com/term_paper_topics/2009/10/management-decision-making.html

- (2012) Umpqua Holdings Financial Corporation. Case Study by Ritz Carlton. http://corporate.ritzcarlton.com/en/LeadershipCenter/Studies/UmpquaHoldingsCorporation.htm

- (2012) Goldman Sachs Training and Orientation. http://www.goldmansachs.com/careers/why-goldman-sachs/training-and-orientation/training-and-orientation-main-page.html

- Gandel, S. (2001) Goldman Hirelings Educate Execs to Keep the Lead. Crain’s New York Business, 17, 35. Quoted in Zolfo, E. and Mann, D. (2012) Global Competition and Learning Organizations: Goals and Motivations of Corporate Leaders and Employees Who Participate in Corporate/University Partnerships. Dowling College, Forum on Public Policy. http://www.forumonpublicpolicy.com/archive07/zolfomann.pdf

- Trichur, R. (2009) Goldman’s Huge Profit Stirs Public Outrage. Toronto Star. http://www.thestar.com/business/article/666314--goldman-s-huge-profit-stirs-public-outrage.

- Reisinger, S. (2012) Senators Express Disgust, Anger as Corporate Execs Squirm. Corporate Counsel. http://www.law.com/jsp/article.jsp?id=1202453292949&Senators_Express_Disgust_Anger_as_Goldman_Execs_Squirm&slreturn=1.

- Taibbi, M. (2009) The Great American Bubble Machine. Rolling Stone. http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/the-great-american-bubble-machine-20100405.

- Macalister, T. (2010) Revealed: Goldman Sachs Made Fortune Betting against Clients. The Observer. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/apr/25/goldman-sachs-senator-carl-levin

- (2006) Investment Bankers Flock to Spiritual Guru. Dealbook. http://www.areyoureadytosucceed.com/dealbook.htm

- (2012) 100 Best Companies to Work for. http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/bestcompanies/2011/index.html

- (2012) The 10 Most Hated Companies in America. http://247wallst.com/2012/01/13/the-10-most-hated-companies-in-america/

- Wikipedia Team Learning. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Team_learning

- (2012) Peter Senge and the Learning Organization. In: Infed: The Encyclopaedia of Informal Education. http://www.infed.org/thinkers/senge.htm

- Hollis, E. (2004) Deutsche Bank: Building Global Learning. Chief Learning Officer Magazine, Mediatec Publishing, Inc. http://clomedia.com/articles/view/deutsche_bank_building_global_learning/1

- Kim, J.Y. (2012) Quoted in Global Development at a Pivotal Time: A Conversation with World Bank President Dr. Jim Yong Kim. Brookings Institution. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/2012/07/18/world-bank-group-president-jim-yong-kim-brookings-institution

- (2012) Goldman Sachs Training and Orientation. http://www.goldmansachs.com/careers/why-goldman-sachs/training-and-orientation/training-and-orientation-main-page.html

- Kouzes, J.M. and Posner, B.Z. (2007) The Leadership Challenge. 4th Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., San Francisco, 326.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. (2012) Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980. http://www.bos.frb.org/about/pubs/deposito.pdf

- Investopedia. (2012) Definition of Regulation Q. http://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/regulationq.asp#ixzz2DXtNbTH3

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (2012) Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982. http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/8000-4100.html

- Reagan, R. (1982) Remarks on Signing the Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982. In: The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=41872

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (2012) Competitive Equality Banking Act of 1987. http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/6500-3240.html

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (2012) Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989. http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/8000-3100.html

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (2012) Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991. http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/8000-2400.html

- Henderson, D.R. (2012) The Roots of the 2008 Economic Collapse. Review of What Caused the Financial Crisis? In: Friedman, J., Ed., What Caused the Financial Crisis? University of Pennsylvania Press. http://www.hoover.org/publications/policy-review/article/80211

- White, A. (2008) Blaming the CRA. Consumer Law & Policy Blog. Public Citizen’s Consumer Justice Project. http://banking.about.com/gi/o.htm?zi=1/XJ&zTi=1&sdn=banking&cdn=money&tm=1644&gps=226_355_1020_537&f=00&su=p284.13.342.ip_&tt=2&bt=1&bts=1&zu=http%3A//pubcit.typepad.com/clpblog/2008/09/blaming-the-cra.html

- Wikipedia (2012) The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dodd%E2%80%93Frank_Wall_Street_Reform_and_Consumer_Protection_Act

- Investopedia (2012) Definition of Regulation Q. http://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/regulationq.asp#ixzz2DXtNbTH3

- Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FINCEN). (2012) USA Patriot Act. http://www.fincen.gov/statutes_regs/patriot/

- Mehran, H., Morrison, A. and Shapiro, J. (2011) Corporate Governance and Banks: What Have We Learned from the Financial Crisis? Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, No. 502, 1.

- Mainelli, M. and Giffords, B. (2009) The Road to Long Finance: A Systems View of the Credit Scrunch. Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation, No. 87, London, 6.

- Kolhatkar, S. and Weise, K. (2012) Dodd-Frank: The 848-Page Financial Firewall. Bloomberg Business Week. http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2012-10-11/dodd-frank-the-848-page-financial-firewall

- Goldman Sachs. (2012) Goldman Sachs Hires Stephen Kerr as Chief Learning Officer. http://www.goldmansachs.com/media-relations/press-releases/archived/2001/2001-05-10.html

- Karkoulian, S., Halawi, L.A. and McCarthy, R.V. (2008) Knowledge Management, Formal and Informal Mentoring: An Empirical Investigation in Lebanese Banks. The Learning Organization, Emerald Group Publishing, 15, 409-420.

- Zolfo, E. and Mann, D. (2007) Global Competition and Learning Organizations: Goals and Motivations of Corporate Leaders and Employees Who Participate in Corporate/University Partnerships. Forum on Public Policy: A Journal of the Oxford Round Table. http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Global+competition+and+learning+organizations%3a+goals+and+motivations...-a0180164015

- (2009) 250 Bankers Attend Banker Legislative Day. Texas Banking Magazine. http://www.texasbankers.com/tba_info_news_releases.php?news_id=690&archived=&type=Bank

- Codjia, M. (2012) Mandatory Annual Compliance Training for Banks. http://www.ehow.com/about_6647167_mandatory-annual-compliance-training-banks.html

- Caldwell, R. (2011) Leadership and Learning: A Critical Reexamination of Senge’s Learning Organization. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 25, 39-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11213-011-9201-0

- Argyris, C. (2004) Reasons and Rationalizations: The Limits of Organizational Knowledge. Oxford University Press, Oxford. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268078.001.0001

- Ahearn, W.E. (2005) Walter Wriston, Ex-Citigroup Chief Executive, Dies. Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=as3a1z7NeiSY&refer=us

- Deal, T.E. and Kennedy, A.A. (1982) Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life. Addison Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, 126.

- Weber, A.A. (2009) The Future of Banking Regulation. Dinner Speech at the Conference on “The Future of Banking Regulation” Organized by Imperial College London and the Deutsche Bundesbank, Frankfurt am Main. http://www.bis.org/review/r090929a.pdf