Open Journal of Orthopedics

Vol.3 No.1(2013), Article ID:29384,6 pages DOI:10.4236/ojo.2013.31004

The Clinical Characteristics of Combined Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis of Rivaroxaban and Mechanical Therapy after Total Knee Replacement Arthroplasty

![]()

Joint & Arthritis Research, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Himchan Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

Email: changcape@naver.com

Received December 9th, 2012; revised January 13th, 2013; accepted February 27th, 2013

Keywords: Deep Vein Thrombosis; Total Knee Replacement Arthroplasty; Rivaroxaban

ABSTRACT

Purpose: To investigate the clinical characteristics of combined prophylaxis of rivaroxaban (Xarelto®) and mechanical therapy (foot sole pump, antiembolism stocking) after total knee replacement arthroplasty, for prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Materials and Methods: The subjects of this study were 110 patients who underwent total knee replacement arthroplasty (TKA) between November 2011 and May 2012, and were prospectively evaluated. They consisted of 13 men (11.8%) and 97 women (88.2%) with the mean age of 68.7 years (±7.9). All of the patients received 10 mg of rivaroxaban once daily for 14 days from Day 1 postoperatively, and used an intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) pump and compression stockings immediately after the operation. To determine the presence of postoperative DVT, clinical symptoms examination, D-dimer test, color Doppler ultrasound imaging were performed to analyze the risk factors of DVT events. Results: There were a total of 13 patients (11.8%) with DVT in the distal lower limbs among the entire 110 patients. At Day 4 after the operation, a statistically significant difference was seen only in femoral swelling of several clinical symptoms between DVT group and non-DVT group (p = 0.043). D-dimer tests showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups, however with the boundary value of 0.3 mg/L, diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, positive predictability and negative predictability were equivalent to 100%, 8.2%, 12.7% and 100%, respectively. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of well-known risk factors including age, gender, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and anesthesia method, and no case of pulmonary embolism was observed. Conclusion: A combination of pharmacological therapy (rivaroxaban, Xarelto®) and mechanical therapy (foot sole pump system) after TKA is considered effective for DVT prevention.

1. Introduction

With the advent of aging society, the elderly population has increased rapidly leading to rising concern in degenerative diseases. Since a typical degenerative disease, degenerative arthritis usually has great effects on the patient’s daily life due to severe pain, the number of patients with end-stage knee osteoarthritis undergoing total knee replacement arthroplasty (TKA) is increasing. In the United States, about 0.7 million of TKAs have been performed annually, and it is estimated that about 35 million of TKAs will be conducted by 2030 [1]. It is reported that as one of post-TKA complications, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is relatively common after orthopedic surgery, has a high likelihood to develop into pulmonary thromboembolism, and causes fatal pulmonary embolism in 0.5% - 2% of the affected patients [2]. Because the relevant clinical findings are usually non-specific and asymptomatic despite of some symptoms such as paintenderness, swelling, heat or redness in the lower leg, the prevention and early diagnosis of DVT is critically important. Generally, the known risk factors of DVT include old age, obesity, the past history of venous embolism and/or thrombosis, the presence of malignant diseases, cardiac disease, the past history of lower limb surgery, hematological disorder, long-term fixation or paralysis, varicose veins, pregnancy, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, hormone treatment, and contraceptive use. Although it is known that the event of vein thrombosis after TKA is usually attributed to complicated factors, lower limb surgery itself may be one of main risk factors of vein thrombosis.

In the Western countries, TKA patients are considered at high risk for DVT, and it was reported that in the absence of preoperative prophylaxis (i.e., preventive measure), the frequency of DVT ranged from approx. 40% to 80% [3]. In the Eastern countries, the importance of preoperative prophylaxis has not been emphasized owing to 10% - 20% of low prevalence rates, however up to 40% of incidence rates are currently reported along with steadily increasing frequency [4].

It was reported that if effective DVT prophylaxis is given, the incidence rates were reduced to 10% - 20% [5], and for the reason, mechanical and pharmacological therapies are commonly used. Mechanical therapies include initiating early postoperative exercise, using compression dressings and stockings, using a foot pump, and doing active ankle pump exercise [6], while pharmacological therapies include aspirin, low molecular weight heparin, warfarin, and dextran. In addition, as new drugs such as dabigatran, rivaroxaban or apixaban have the advantages of availability as oral dosage form, unnecessary monitoring based on hematological tests, fixed dose administration without dosage adjustments, less interacttions with food or other drugs, the results of clinical studies on their efficacy and safety have been reported in recent days [7-9]. Of these, rivaroxaban acts as a factor Xa inhibitor, and in their recent comparative study of rivaroxaban versus warfarin, Patel MR et al. reported that there was no significant difference between the two groups even in stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, and non-major bleeding, and instead, the incidence rates of intracranial bleeding and fatal bleeding were lower in rivaroxaban group [10]. Also, rivaroxaban was approved for DVT prevention after some orthopedic surgical procedures in the United States, Canada and Europe, and was approved by the US FDA for the reduction of stroke and thrombosis in atrial fibrillation patients as well as for the prevention of thrombosis in patients undergoing total knee or hip replacement arthroplasty patients in September 2011. There was the increasing demand for the said medication in South Korea as well. In this context, the study was intended to investigate the clinical characteristics of combined DVT prophylaxis of rivaroxaban (Xarelto®) and mechanical therapy (foot sole pump, antiembolism stocking) after TKA.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the hospital ethic committee at our institution, and all participants were provided with an informed consent. The subjects of this study were 110 patients who underwent TKA between November 2011 and May 2012, and were prospectively evaluated. They consisted of 13 men (11.8%) and 97 women (88.2%) with the mean age, weight, height and body mass index (BMI) of 68.7 years (±7.9), 60.5 kg (±9.8), 153.1 cm (±7.8) and 25.8 kg/m2 (±3.8), respectively. Their etiologies were composed of degenerative arthritis (103 cases), osteonecrosis (6 cases) and rheumatoid arthritis (1 case). The number of cases receiving either unilateral TKA or bilateral TKA (at a 1-week interval) was 51 and 59, respectively, and the surgery was performed under a general anesthesia by a single surgeon. The patients all used Scorpio NRG® (Non-Restrictive Geometry, Stryker®, Allendale, NJ, USA). Every patient took 10mg rivaroxaban as an oral anticoagulant for DVT prophylaxis, once daily for 14 days from Day 1 postoperatively, and at the same time, used intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) pumps and compression stockings shortly after the operation, and also continuous passive motion (CPM) of the knee was initiated on postoperative day 2 or 3. To analyze the correlation with risk factors affecting DVT incidence, the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients including age, gender, obesity, hypertension, diabetes and smoking status were investigated. To determine the presence of DVT, the clinical symptoms of patients were examined at Days 4 and 9 after the operation. During examination of clinical symptoms, the severity of distal femoral pain and proximal tibial pain was assessed using a verbal rating scale (VRS) (0 = no pain; 1 = mild pain; 2 = moderate pain; and, 3 = severe pain) [9]. Thigh swelling was assessed in the manner of measuring the circumference of the thigh at a distance of 10 centimeters from the patella in both the lower limbs with and without the surgical site, and subsequently categorizing differences between the measurements into four grades (0 = no swelling; 1 = less than 1.5 cm; 2 = 1.6 - 3.0 cm; and, 3 = 3 cm or more) [11]. The severity of thigh bruising was assessed on the basis of the criteria proposed by Warwick et al. [12,13] specifically, 0 point for no color change; 1 point for light yellow; 2 points for dark yellow; 3 points for yellow in the area of at least three palms; 4 points for yellow-black; and, 5 points for yellow-black in the area of at least three palms. In addition, local heat around the patella was assessed and judged as one of mild, moderate or severe in consideration for patient’s gait, exercise and fomentation right before examination of clinical symptoms, followed by checking the patients for a positive Homan’s sign.

At Day 7 after the operation, a same radiologist examined the common femoral vein, superficial femoral vein, and popliteal vein using color Doppler ultrasound imaging to check for the presence of deep vein thrombosis. Besides, D-dimer testing was carried out which is primarily employed to rule out venous thrombosis by virtue of its high sensitivity and negative predictability, and the results of less than 0.3 mg/L were judged as negative.

The results of each group were expressed as mean, standard deviation and frequency (%), and statistical analyses of respective parameters were conducted using SPSS (18.0 for Windows, Chicago, Illinois) statistical software program. Risk factors found in the two groups were analyzed with independent t-test at a significance level of p < 0.05. Furthermore, to determine the usefulness of D-dimer testing, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictability and negative predictability were calculated and analyzed.

3. Results

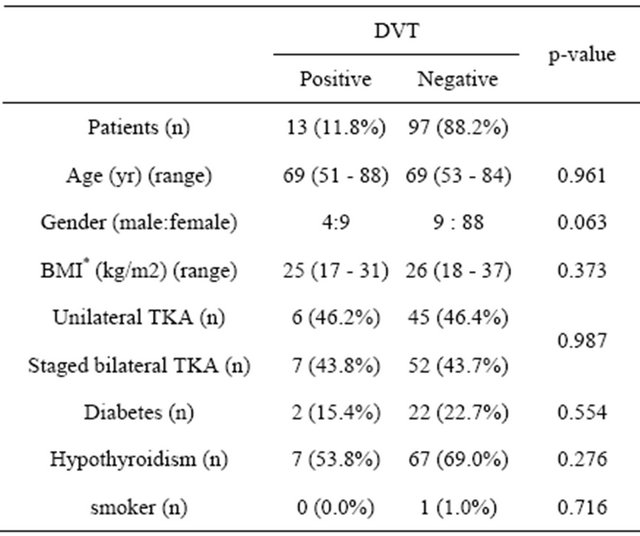

There were a total of 13 patients (11.8%) with DVT of one hundred and ten patients who underwent TKA, and there was no patient experiencing pulmonary embolism. 6 (11.8%) of 51 patients receiving unilateral TKA and 7 (11.9%) of 59 patients receiving staged bilateral TKA developed DVT and all of them had distal DVT (Table 1).

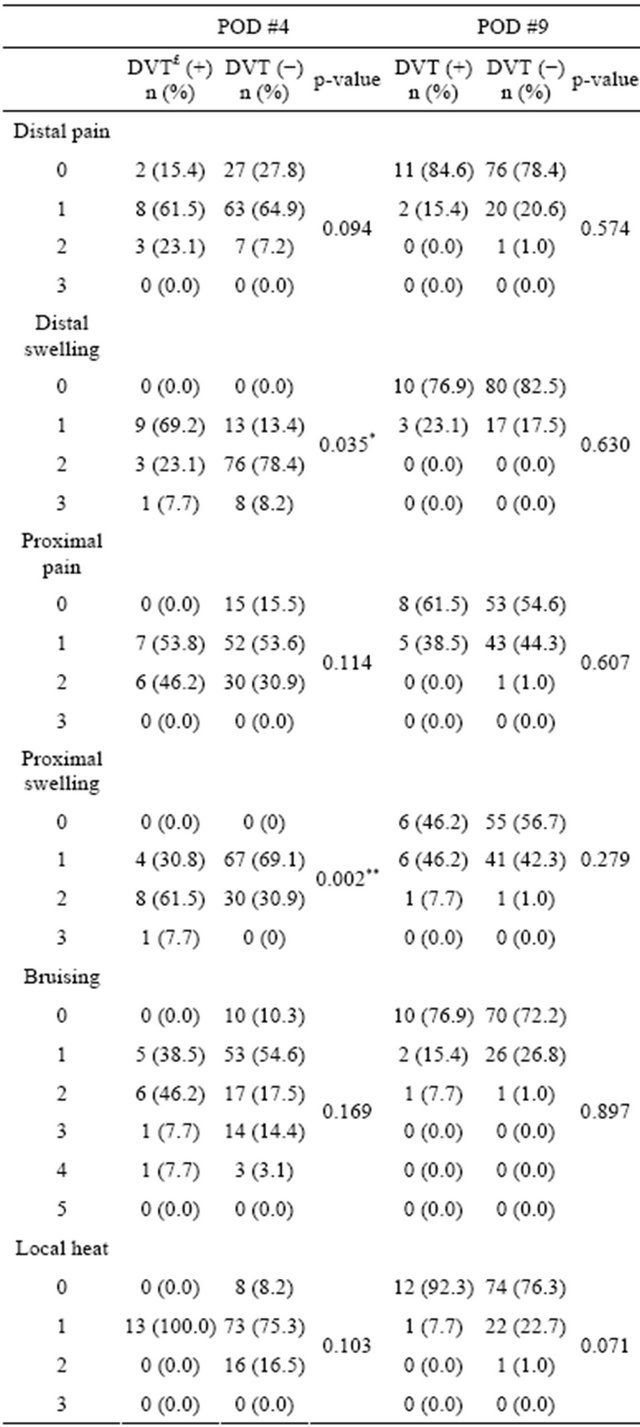

Of clinical symptoms examined at Day 4 postoperatively, thigh swelling index was 1.4 in DVT group compared to 0.9 in non-DVT group, indicating statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.043). When the severity of pain (0 - 4) was assessed, distal femoral pain was equivalent to 1.5 in DVT group compared to 1.2 in non-DVT group. Proximal pain was equivalent to 1.1 (close to mild pain) in DVT group, compared to 0.8 in non-DVT group. The results of assessing the severity of bruising (0 - 4) indicate 1.8 and 1.5 (close to dark yellow) in DVT group and non-DVT group, respectively. Local heat (0 - 3) corresponded to 1.0 in DVT group and 1.1 in non-DVT group. No significant difference in the statistical significance of pain, bruising and local heat was seen between the two groups.

The mean distal femoral pain and proximal tibial pain, thigh bruising, and local heat around the patella were 1.5, 1.1, 1.8, and 1.0 respectively in DVT group, and 1.2, 0.8, 1.5, and 1.1 respectively in non-DVT group, suggesting no statistical significance (p > 0.05). Similarly, no sig-

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients.

*BMI: body mass index.

nificant difference in the findings of clinical symptoms examined at Day 9 postoperatively was observed between the two groups. Even in thigh swelling index exhibiting some difference, no statistically significant difference was seen between DVT group and non-DVT group (p = 0.574) (Table 2).

Table 2. Univariate analysis results for clinical symptoms.

£DVT: deep vein thrombosis; *Significantly different between the two groups: p < 0.05; aValues are means ± standard deviations.

There was also no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of known risk factors including age, gender, obesity, hypertension, diabetes and smoking status (p > 0.05).

All the patients received D-dimer testing at Day 7 to 10 after the operation, 102 of the entire 110 patients were categorized into positive (+) range, and based upon imaging findings, just 13 cases were diagnosed as DVT. On the other hand, there was no event of DVT in 8 patients categorized into negative (−) range. When the boundary value of D-dimer testing was set to 0.3 mg/L, diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, positive predictability and negative predictability were 100%, 8.2%, 12.7% and 100%, respectively. This test showed no statistically significant difference between DVT group and non-DVT group (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

It is reported that the frequency of various complications after TKA is estimated at up to 23.6%, and initially, the complications were limited to swelling or hemarthrosis, however in recent days, composed primarily of complications associated with revision TKA. The types of complications include infection, necrosis, hematoma, seroma, thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, renal or urinary dysfunction, cardiac dysfunction, and postoperative changes in mental status [14]. It was reported that among these complications, the frequency of DVT after TKA was estimated at 35% - 65% without prophylactic medication, and that of fatal pulmonary embolism at 0.5% - 3% [6]. However, a study reported that with prophylactic medication, the incidence rate of DVT ranged from 10% to 20%, and that of pulmonary embolism was also estimated at less than 1%. In general, it is known that the frequency of post-TKA DVT is somewhat lower (ranging from 14% to 42%) in the Eastern countries than in the Western countries [15]. However, because it may cause several symptoms leading to patient’s discomfort and at the worst, death, the number of patients receiving prophylactic medications for DVT prevention is increasing. In this study, prophylactic medication was applied in all the cases to prevent post-TKA DVT, and conesquently, the frequency of DVT was relatively low (11.8%) while there was no case of pulmonary embolism.

The medications used for DVT prophylaxis are very limited to: aspirin, dextran, warfarin, low molecular weight heparin, and so on. Of these, low molecular weight heparin is contraindicated in patients with any of pulmonary embolism, underweight (<50 kg; thromboembolism only), or serious renal impairment, while warfarin has unpredictable pharmacological effects in spite of constant monitoring and a high likelihood of food-drug interactions [16]. Similarly, it is known that aspirin can reduce the risk of postoperative bleeding problems [17], however its safety as an anticoagulant is still disputable.

Meanwhile, since used by the authors in this study, rivaroxaban (Xarelto®) acts as a factor Xa inhibitor and has the advantages of availability as oral dosage form, unnecessary monitoring based on hematological tests, fixed dose administration without dosage adjustments, less interactions with food or other drugs, the results of clinical studies on their efficacy and safety have been reported in recent days [9].

For effective prevention of DVT, the present authors gave pharmacological therapy in combination to mechanical therapy such as IPC pump or compression stockings immediately after the operation and afterwards, and continuous passive motion (CPM) of the knee was initiated on postoperative day 2 or 3.

According to some reports [18-20], TKA itself is a risk factor of DVT because it may cause venous congestion, excessive clotting, and/or blood vessel intimal injury—for example, attributed to the position of lower limbs during the operation, local swelling in the surgical site, surgical manipulations themselves or intraoperative tissue injury. In addition, many studies suggest that it is associated with such risk factors as age, gender, obesity, varicosity, hypertension, diabetes, mobility, and/or the duration of tourniquet use [21,22], however their relationship remains unclear. No significant intergroup difference was found in this study comparing DVT group versus non-DVT group in terms of age, gender, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking.

DVT is difficult to predict its event and it is critically important to give timely treatments through early diagnosis. However, it is very important to monitor carefully the postoperative clinical symptoms of patients because they are either symptomatic or asymptomatic. In this study, patient’s clinical symptoms at Days 4 and 9 postoperatively were examined to check for any clinical symptoms in this study, and it was observed that thigh swelling index at Day 4 was significantly higher in DVT group than in non-DVT group. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups in other clinical symptoms including distal femoral pain and proximal tibial pain, thigh bruising, and local heat around the patella, and also in swelling index at Day 9. Furthermore, all the patients received D-dimer testing after the operation, and as calculated from the results of testing, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictability and negative predictability were 100%, 8.2%, 12.7% and 100%, which indicates higher sensitivity and negative predictability suggesting its high applicability as a test intended to rule out venous thrombosis, but no difference in test results was seen between DVT group and non-DVT group.

This study has the following limitations. First, there was no comparison group about the other drug. As the results of this study are consistent with those of a study performed by R. Patel et al. [10] in which comparisons of rivaroxaban versus warfarin as anticoagulant were made and reported, it is considered feasible to evaluate just the clinical results of DVT prophylaxis with rivaroxaban. However, further studies designed to make comparisons with other drug group are required. Second, we did not use venography, for DVT diagnosis. Venography is the gold standard for diagnosis DVT, however, this technique is invasive and requires the use of potentially hazardous contrast agents [23]. Because it may not be suitable immediately after TKA, we diagnosed the DVT using color Doppler ultrasound imaging. Finally, in spite of some studies reporting the delayed events of post-TKA DVT at up to Day 30, [24,25] this study assessed the early events of DVT at up to Day 10 only. Nevertheless, the clinical symptoms and outcomes of DVT were carefully followed up in visits at Months 1 and 3, and no case of DVT was observed.

5. Conclusion

In this study of DVT prophylaxis with a combination of pharmacological therapy and mechanical therapy after TKA, the frequency of DVT was 11.8%, no thrombosis at Day 9 appeared in both the groups, without any events of complications resulting from thrombosis. It seems to be required to follow further up clinical symptoms, e.g., postoperative swelling, in patient populations at risk of thrombosis. A combination of pharmacology therapy (Rivaroxaban, Xarelto®) and mechanical therapy (foot sole pump system) after TKA is considered effective for DVT prevention.

REFERENCES

- D. L. Riddle, F. J. Keefe, D. Ang, K. J. Saleh, L. Dumenci, M. P. Jensen, M. J. Bair, S. D. Reed and K. Kroenke, “A Phase III Randomized Three-Arm Trial of Physical Therapist Delivered Pain Coping Skills Training for Patients with Total Knee Arthroplasty: The Kastpain Protocol,” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1239-1250. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-149

- J. R. Lieberman and W. H. Geerts, “Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism after Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty,” Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, Vol. 76, No. 8, 1994, pp. 1239-1250. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.03033

- W. H Geerts, D. Bergqvist, G. F. Pineo, J. A. Heit, C. M. Samama, M. R. Lassen and C. W. Colwell, “Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition),” Chest, Vol. 133, No. 6, 2008, pp. 381S- 453S. doi:10.1378/chest.08-0656

- Y. H. Kim and J. S. Kim, “Incidence and Natural History of Deep-Vein Thrombosis after Total Knee Arthroplasty. A Prospective, Randomised Study,” The Bone & Joint Journal, Vol. 84, No. 4, 2002, pp. 566-570. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.84B4.12330

- D. S. Hwang, S. T. Kwon, Y. M. Kim, Y. J. Young, S. H. Yune and H. C. Jeong, “Prophylaxis of Postoperative Deep Vein Thrombosis and Thromboembolism with Low Molecular Weight Heparin (Nadroparin Calcium) after Hip Arthroplasty—Comparison with Warfarin and Low Molecular Weight Dextran,” Journal of the Korean Orthopedic Association, Vol. 34, No. 1, 1999, pp. 9-16.

- J. I. Arcelus, J. C. Kudrna and J. A. Caprini, “Venous Thromboembolism Following Major Orthopedic Surgery: What Is the Risk after Discharge?” Orthopedics, Vol. 29, No. 6, 2006, pp. 506-516.

- J. W. Little, “New Oral Anticoagulants: Will They Replace Warfarin?” Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, Vol. 113, No. 5, 2012, pp. 575- 580. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2011.10.006

- G. Agnelli, “Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism in Surgical Patients,” Circulation, Vol. 110, No. 4, 2004, pp. 4-12. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000150639.98514.6c

- S. T. Duggan, L. J. Scott and G. L. Plosker, “Rivaroxaban: A Review of Its Use for the Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism after Total Hip or Knee Replacement Surgery,” Drugs, Vol. 69, No. 13, 2009, pp. 1829-1851. doi:10.2165/11200890-000000000-00000

- R. P. Manesh, W. M. Kenneth, G. Jyotsna, P. Guohua, E. S. Daniel, H. Werner, B. Günter, L. H. Jonathan, J. H. Graeme, P. P. Jonathan, C. B. Richard, C. N. Christopher, F. P. John, D. B. Scott, A. A. F. Keith, Ch.B. and M. C. Robert, “Rivaroxaban versus Warfarin in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation,” Indian Heart J, Vol. 64, No. 1, 2012, pp. 110-111. doi:10.1016/S0019-4832(12)60029-7 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019483212600297

- E. K. Song, J. K. Seon, S. J. Park, S. B. Cho and M. S. Choi, “Diagnosis of the Deep Vein Thrombosis with Multidetector-Row Computed Tomographic Venography after Total Knee Arthroplasty,” Journal of the Korean Orthopedic Association, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2008, pp. 294-300.

- D. Warwick, J. Harrison, D. Glew, A. Mitchelmore, T. J. Peters and J. Donovan, “Comparison of the Use of a Foot Pump with the Use of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin for the Prevention of Deep-Vein Thrombosis after Total Hip Replacement. A Prospective, Randomized Trial,” Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, Vol. 80, No. 8, 1998, pp. 1158-1166.

- J. K. Lee, K. S. Chun, S. W. Baek and C. H. Choi, “The Prophylaxis of Venous Thromboembolism in Korean Patients with Total Knee Replacement Arthroplasty,” Journal of the Korean Orthopedic Association, Vol. 47, No. 2, 2012, pp. 86-95.

- P. Frosch, J. Decking, C. Theis, P. Drees, C. Schoellner and A. Eckardt, “Complications after Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Comprehensive Report,” Acta Orthopaedica Belgica, Vol. 70, No. 6, 2004, pp. 565-569.

- Y. J. Kim, C. I. Hur, E. K. Song, J. K. Seon, S. J. Park, S. B. Cho and Y. J. Cho, “Availability of D-Dimer Test for the Diagnosis of Deep Vein Thrombosis after Total Knee Arthroplasty,” Journal of the Korean Orthopedic Association, Vol. 42, No. 4, 2007, pp. 523-529.

- S. N. Melillo, J. V. Scanlon, B. P. Exter, M. Steinberg and C. I. Jarvis, “Rivaroxaban for Thromboprophylaxis in Patients Undergoing Major Orthopedic Surgery,” The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, Vol. 44, No. 6, 2010, pp. 1061-1071. doi:10.1345/aph.1M681

- Intermountain Joint Replacement Center Writing Committee, “A Prospective Comparison of Warfarin to Aspirin for Thromboprophylaxis in Total Hip and Total Knee Arthroplasty,” The Journal of Arthroplasty, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-9. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2011.03.032

- P. T. Duncan, “Venous Trombogenesis,” Annual Review of Medicine, Vol. 36, 1985, pp. 39-50. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.36.020185.000351

- D. S. Hwang, S. T. Kwon, S. H. Yune, H. R. Oh and S. Y. Lee, “Deep Venous Thrombosis after Hip Arthroplasty,” Journal of the Korean Orthopedic Association, Vol. 32, No. 3, 1997, pp. 554-564.

- S. Bredbacka, M. Andreen, M. Blombäck and A. Wykman, “Activation of Cascade Systems by Hip Arthroplasty. No Difference between Fixation with and without cement,” Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica, Vol. 53, No. 3, 1987, pp. 231-235.

- Y. H. Kim and J. S. Suh, “Low Incidence of Deep-Vein Thrombosis after Cementless Total Hip Replacement,” Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, Vol. 70, No. 6, 1988, pp. 878-882.

- N. E. Sharrock, S. B. Haas, M. J. Hargett, B. Urquhart, J. N. Insall and G. Scuderi, “Effects of Epidural Anesthesia on the Incidence of Deep-Vein Thrombosis after Total Knee Arthroplasty,” Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, Vol. 73, No. 4, 1991, pp. 502-506.

- J. P. Carpenter, G. A. Holland, R. A. Baum, R. S. Owen, J. T. Carpenter and C. Cope, “Magnetic Resonance Venography for the Detection of Deep Venous Thrombosis: Comparison with Contrast Venography and Duplex Doppler Ultrasonography,” Journal of Vascular Surgery, Vol. 18, No. 5, 1993, pp. 734-741. doi:10.1016/0741-5214(93)90325-G

- O. E. Dahl, T. E. Gudmundsen and L. Haukeland, “Late Occurring Clinical Deep Vein Thrombosis in Joint-Operated Patients,” Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica, Vol. 71, No. 1, 2000, pp. 47-50. doi:10.1080/00016470052943883

- J. D. Douketis, J. W. Eikelboom, D. J. Quinlan, A. R. Willan and M. A. Crowther, “Short-Duration Prophylaxis against Venous Thromboembolism after Total Hip or Knee Replacement: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies Investigating Symptomatic Outcomes,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 162, No. 13, 2002, pp. 1465- 1471.