Open Journal of Political Science

Vol.4 No.2(2014), Article ID:45482,13 pages DOI:10.4236/ojps.2014.42009

Co-Motion—Twitter Enters the Public Domain

George Robert Boynton

Department of Political Science, University of Iowa, Iowa City, USA

Email: bob-boynton@uiowa.edu

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 3 February 2014; revised 6 March 2014; accepted 27 March 2014

ABSTRACT

Political communication is being dramatically altered by the new or social media. The new media has discovered this communication. The politicians have discovered this communication. The paper is an argument about what the public domain becomes as the new media becomes pervasive in society. The evidence used to buttress the argument is taken from 800 collections of streams of Twitter messages. Twitter is particularly useful as evidence because it is by default public. Hence, it is in the public domain. And it is readily available for researchers. The conclusion is that we have moved from broadcast-audience to co-motion, and that is a dramatic transformation of the public domain.

Keywords:Co-Motion, Twitter, Public Domain, Politics, Broadcast Audience

1. Introduction

In 2008, Lance Bennett and Shanto Iyengar published “A new era of minimal effects” in which they traced political communication research from the 1940s to the date of their writing (Bennett & Iyengar, 2008). It was an era of broadcast communication. Suddenly in the 1940s, the technology made a reach possible that had never before been possible. The questions were: what would be done with the technology and what effects would it have on the audience? It was an era of broadcast-audience, and they effectively summarize what was learned by research in the era.

2008 could also be understood as the inflection point in the move to a new era in public communication. Blogs were actively in use, and they were particularly in use for political communication (Karpf, 2008). Obama had shown that having fans on a Facebook page and using that for attracting campaign financing was a plus for a candidate for the highest office in the land. And will.i.am showed that a political video on YouTube could attract as many viewers as any that the broadcast media could produce (Wallsten, 2010). But it did not stop in 2008. In 2009, Teaparty emerged. These were people widely separated geographically. They needed a technology that would let them communicate, and it became Twitter. In 2009, Twitter was just becoming large enough to attract attention, and Teaparty found it and rode it to have a substantial impact on the 2010 election. Then there were the revolts in North Africa and the Middle East. Reporters were not welcome so the world, including the Arab world, watched video provided by people on the ground, uploaded to YouTube, and then broadcast for the world to see. That was followed by OccupyWallStreet. And the list could go on and on.

It is a new era in public communication. The technologies being used by what are variously called new media and social media are opening up the public domain in ways that were not possible before. This is how the broadcast media calls it. In 2012, a new person headed up BBC. His inaugural speech was reported.

New BBC chief vows to re-invent content, not just re-purpose it

“As we increasingly make use of a distribution model—the internet—principally characterised by its return path, its capacity for interaction, its hunger for more and more information about the habits and preferences of individual users, then we need to be ready to create content which exploits this new environment—content which shifts the height of our ambition from live output to living output.

“We need to be ready to produce and create genuinely digital content for the first time. And we need to understand better what it will mean to assemble, edit and present such content in a digital setting where social recommendation and other forms of curation will play a much more influential role. (Andrews, 2012)

The technology of communication makes interaction possible and explodes the broadcast paradigm. It is not enough to re-purpose; we must re-invent, he said. We must create content that is genuinely interactive. And “curation” is a code word for bringing together communication we did not produce and packaging it in a way that our followers will want to view it. That “curation” was exactly what Al Jazeera had done for the revolts in North Africa and the Middle East in 2011.

This is how Jim Roberts, assistant managing editor of the New York Times, tells about social media and the operation of the New York Times.

I definitely think the transition to digital—it’s enormous, it’s ongoing. Change is hard. Dealing with disruptive technologies left and right requires a lot of energy, a lot of imagination. And every institution like ours deals with it. Just as we’ve mastered the Web, we then are faced with a completely new environment in which people are getting information on their phones. Tablets are now creating their own different types of use cases and consumption. Social media came out of nowhere. If you and I had this conversation four years ago, we wouldn’t be talking about Twitter. (Taintor, 2012)

He talked about more than the changes in technology for receiving the news. He talked about how reporters are using social media and, in particular, Twitter in their work. And he tells a story that epitomizes that change. It was September 17, 2011. OccupyWallStreet was marching across Brooklyn Bridge and being sprayed and arrested. There was a surge in messages about this and he received a Twitter direct message asking why the New York Times was not covering it. He checked and found that the Times had been covering it, but on the local news pages. He thought it should have wider coverage and so did others. So OccupyWallStreet made the front page for the first time. It also was the subject of 150,000 Twitter messages (Boynton, 2011a). That was the turning point for the movement. From that time on OccupyWallStreet was a movement becoming global.

The broadcast media know this is a new era. They know how important the new technology is in reshaping the public domain. It is a new time. It needs a new framework or paradigm for understanding and for research. And that is what this paper suggests.

The argument is:

1. In the last decade, the public domain has been and is being reconstructed.

2. The public domain is communication; it is the communicating. The communication is carried by a technology. When the technology changes the public domain is reconstructed as humans rush to take advantage of the new technology.

3. Broadcast media have been the monopoly suppliers of the public domain because broadcast was the technology that extended the reach of the public domain to larger and larger populations.

• Broadcast media include newspapers, radio, television, mass direct mailing, bulk email campaigns, and others.

4. The internet with its global expansion and the concomitant increase in speed is the technological change undergirding the new or social media.

• YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter are the most popular of the new media, but they are joined by social networks like Tumbler, Pinterest and many others.

5. With the new media the “audience” gains voice, and the public domain becomes co-motion.

The most fundamental premise of the theorizing about and of the research on political communication has been broadcast-audience. Research about the activity of the broadcast media and research to study the effects of that activity on the audience all are based on the premise that the fundamental structure of the public domain is broadcast-audience.

When the “audience” gains voice the fundamental premise is challenged. Broadcast-audience has no place for voice for the audience. A new fundamental premise becomes necessary.

The new fundamental premise is co-motion. The broadcast media does not go away, but it becomes part of a larger stream with new forms of interaction. Political messaging on Twitter will demonstrate how co-motion goes beyond broadcast-audience. Twitter is used to make this case because of its size, which is 500 million messages a day in 2013 and growing, and because it is by default public. It is in the public domain unless the user constrains it, which few do.

To develop the concept and to demonstrate its importances in contemporary political communication the paper include the following sections:

1. A very brief history of Twitter.

2. The scope of Twitter in political communication is reviewed.

3. Reach—the broadcast media became the public domain by virtue of the reach of the technology. A review of the reach of Twitter messages demonstrates that its reach matches and exceeds the reach of broadcast media.

4. A final section demonstrating how the tools of communication distinctive to Twitter—retweets, hashtags, and shortened urls—facilitate interaction in the public domain that was not been possible when the public domain was broadcast-audience.

2. Data Collections

Collecting the streams of Twitter messages about politics used in this report began in 2009. There are three sets drawn on in this report.

The most extensive set is collections using a desktop program Archivist. It accesses the Twitter API every five minutes requesting messages containing the search term. Twitter will send only 1500 messages per request. If the number of messages being posted to Twitter exceeds 1500 in five minutes the collection will be a sample, in time, of the messages being posted. For most of the collections that limit was not exceeded, but there are cases when the limit was exceeded. The number of messages posted to Twitter about the 2012 State of the Union message peaked at 15,000 a minute, for example (Twitter Blog, 2012c). The samples of messages generally number in the hundreds of thousands, which are samples that exceed the capabilities of tests of significance to discriminate.

The collections began in 2009 and are ongoing. There are more than 550 collections in this set. Some run only a few days and find only a few hundred Twitter messages. Some are much longer running. The collection of Twitter messages with the search term #teaparty ran from 2010 through most of 2013, and there are several others that have run as long. Streams of messages about each of the candidates for the Republican presidential nomination were collected beginning in February of 2011. Collections of messages containing the search terms #feb14, #libya, #mar15, #syria, and #yemen began with the inception of those revolts. Some collections have messages numbering in the hundreds. Some collections have messages numbering in the tens of millions. The collections are extremely diverse in the subjects being investigated.

The second set is collections by Tweettronics.com. Tweettronics data is explicitly a sample, in time, of the messages being posted with any search term. The number of messages collected range from a low of a few per day to approximately 6000 per day. The number depends on the volume of messages being posted to Twitter. Tweettronics supplies information about the messages that is not available using Archivist. There are 29 separate searches and most of the 29 ran from 2011 through 2012.

The third set is 235 collections obtained from R-Shief concerned with the Occupy movement as it became worldwide. They made the files available as part of a hackathon they conducted in 2011. At the time it was a project located at University of Southern California. Subsequently it has become an independent organization with a focus on North Africa and the Middle East. These data are limited in time and the focus of the research, but they are a very extensive collection of searches with the same focus.

3. Twitter

Twitter started in 2006, and it became a favorite of information technology aficionados in 2007 at the South by Southwest interactive conference (Douglas, 2007). It remained largely limited to that community until early spring of 2010 when the number of messages a day reached fifty million (Weil, 2010). By June of 2012 the number of messages per day had grown to 400 million (Farber, 2012). And their growth continues at a rapid rate (Bennett, 2012).

Twitter messages are 140 characters or less. They are easy to write and easy to read. And they are by default public. Most messages can be found and read in a variety of ways. Unlike email, unlike texting, unlike messages on Facebook these messages are in the public domain. Five hundred million messages a day is a huge addition to public discourse in the world.

Much of what is known about communication via Twitter does not fit political messaging using Twitter. The report will point out places where the public domain is quite different from the total stream.

4. Politics on Twitter

The standard interpretation of Twitter messaging is that it is about personal matters and personal relations or entertainment or natural disasters. Friends send direct messages to each other. Music and sports are among the popular entertainment messages. The 2012 Olympics generated more than 150 million Twitter messages, for example (Twitter Blog, 2012d). Earthquakes and tsnuami have produced quite large streams of messages. The winter Olympics in 2014 also saw many millions of tweets with one peak reaching 72,630 tweets per minute. (Fraser, 2014)

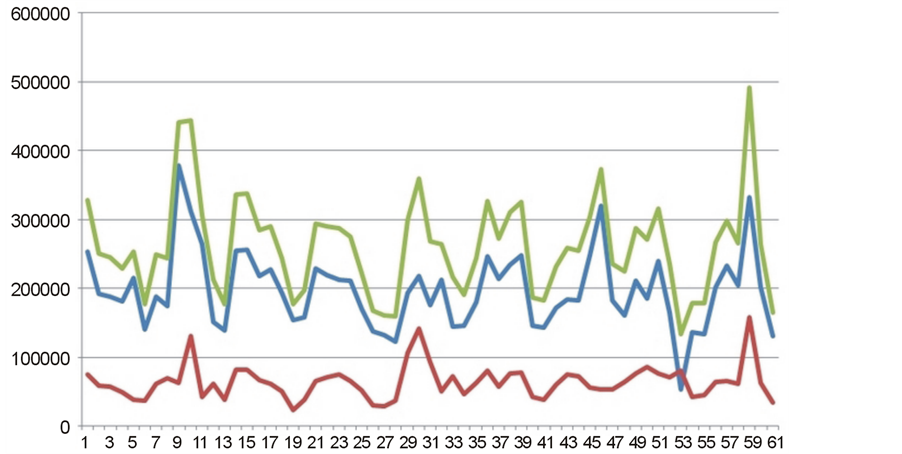

What about politics? Is politics a major player on Twitter as well? In 2012, the presidential election was the major story about politics for the year. The standard projection is that elections do not begin until after Labor Day. That is not so much a statement about the candidates as about the public. It is when, traditionally, most of the public have turned their attention to the election. But the election on Twitter was off to a big start much earlier. Messages mentioning Obama and Romney were collected in May and June. The counts depend on the search term. In the case of Obama the messages mentioned Obama, Barackobama, and Obama 2012. Both Obama and Barackobama had been actively used in Twitter messages before that, but Obama 2012 started at about that point. These are barely overlapping sets. If you mention Obama you do not refer to Barackobama or Obama 2012, for example. So the total for Obama combines all three search terms. The search for Romney was that single search for the two months, and beginning in June searching for mittromney produced enough messages that they became part of the collection as well. So the total for Romney is the total for Romney in May and for Romney and mittromney in June. The secondary searches find relatively few messages compared to the searches for Obama and Romney.

Figure 1 shows the number of messages about Obama, about Romney, and the total number of messages mentioning either. The red line is messages mentioning Romney. The blue line is messages mentioning Obama. And the green line is the sum of the two. During the period Obama was the dominate focus of communication about the election. There are some spikes, but the mean number of messages per day was 197,538, and there is no upward or downward trend during the two months. Romney was mentioned much less frequently. The mean number per day was 64,136, and there is no upward trend from May to June despite adding the search for mittromney. The answer to the question about how big politics is on Twitter is in the total, which was an average of 261,674. The total fluctuates with messages about the candidates, but it is relatively stable over time at 261,274. That is a quarter of million messages about the candidates each day. For a week that is 1.8 million messages. That number agrees with the announcement of Twitter about the #twindex that they had developed for the assessment of messages about the two candidates (Twitter Blog, 2012a). They say their index is based on approximately two million messages a week. Then by the end of the campaign there was a huge spike of communication. On the seventh of November there were 31 million messages about the election and its result (Twitter Blog, 2012b).

Figure 1. Twitter messages about Obama, Romney and the sum of the two.

But large numbers are not limited to the US presidential election campaign. Messages mentioning Bahrain, Syria, Iran and Yemen each totaled approximately 500,000 messages a week. Two political dispositions, Teaparty and P2, are large streams of messages. The progressive stream, #P2, averages about 100,000 messages a week, and #Teaparty averages about 60,000 a week. Some policy domains produce considerable messaging. There were more than a million messages leading up to and with the passage of the health care reform in 2010, for example. And there are huge spikes. The messaging about the State of the Union was extraordinary for a single day (Boynton & Richardson, 2012). As was the messaging the day the Supreme Court released their decision on the health care legislation (Boynton, 2012a).

Politics is too diverse to be able to collect or even sample all political messages using Twitter. Just for starters you would need to collect messages about every politician in the world, every political disposition in the world, every policy matter in the world, every form of demonstration and conflict in the world. There is no list, and there is no shortcut. However, with 500 million a day as the upper limit and based on these collections and the counts Twitter has publicized it seems clear that there are tens of millions of political messages a day. It is a huge addition to the public domain. The public domain has been enormously expanded.

5. Reach

From the very beginning Twitter provided an option to follow any other Twitter account. Some accounts have many millions of followers. Twitaholic.com regularly collects the number of followers for user accounts. President Obama is the only politician in the top 100 with 41,554,111 followers in February of 2014, which puts him third on the list (Twitaholic, 2014). And the number of followers increases every day. Katy Perry is number one with 50,726,545 followers. Every message posted on Twitter goes to all followers. So, every Obama message goes to 41.5 million on this date and even more in the future. These numbers are the exceptions, of course.

Since most of the follower counting is for individuals it is difficult to find aggregate numbers for number of followers per Twitter account. In 2010, Sysomos drew a very large sample and found that 32% had 0 to 5 followers, 52% had 6 to 100 followers, and 16% had more than 100 followers (Sysomos, 2010b). Since the number of followers increased from 2009 to 2010 there is reason to believe that the number of followers has continued to increase. However, the number of followers is generally rather small with the exceptions of celebrities of one sort or another.

What about political messages? Is this low level of following characteristic of political messages?

One way to begin to answer the question is to look at the reach of political organizations (Boynton, 2012b). The organizations investigated were: two specific interest groups—the National Rifle Association and the Sierra Club—two organizations that comment on the media and distortions they find there—MediaMatters and NewsBusters—two general purpose political organizations—MoveOn and the National Review—and ThinkProgress. ThinkProgress is a blog of the Center for American Progress, which is a liberal “educational” organization. These organizations are in the communication and mobilization business. At a point, May of 2012, this is how they had been able to utilize Twitter in their work.

For ten days, May 6 through May 15, 2012, the communication of the organizations was tracked. Table 1 reports the number of followers of each organization at that time. The organization with the fewest followers was NewsBusters. The rest were between 35 thousand and 66 thousand except for ThinkProgress which had 123,190 followers. There was also a relatively large range in posting messages to Twitter. The National Review only posted 272 messages in the ten days. ThinkProgress was again the most active with 2053 posts to Twitter.

Retweets are an important element in the reach of communication on Twitter. Retweeting is anyone reading a message and forwarding it to the person’s followers. When MediaMatters posts a message to Twitter It is available to 60 thousand persons. If that is the end of it then 60 thousand is the reach of their message. But followers of MediaMatters have some number of followers—perhaps as few as 100—themselves. What if half of the 60 thousand followers retweeted the message. Communication would go to the original 60 thousand plus 30,000 times 100 followers for each. Suddenly there would be an explosion of the message as it reached much more widely than the original 60 thousand.

The differences in the number of retweets per organization are striking. The Sierra Club had less than one retweet for each of their posts to Twitter. The National Review and the National Rifle Association and NewsBusters were not far ahead with 1.5 and 1.3 retweets per post. MediaMatters and MoveOn had a somewhat higher rate at 3.6 and 3.9. But it is ThinkProgress that stands out with 22.8 retweets for each post to Twitter.

To check on the spread of these messages the average number of followers for each of the retweets was found and that can be multiplied by the number of retweets to get a total spread of the communication. In ten days, the posts of the National Review reached 739,697. It is surely the case that not all of these messages were read. But not all news stories in newspapers or TV programs are “read”. This is the potential audience for the National Review given its quantity of posting and the retweeting of its followers. MediaMatters is impressive with 8.6 million messages via retweeting. But it is ThinkProgress that is most impressive with 47 million potential views.

ThinkProgress stands out in comparison to the other political organizations that are more wedded to pre social media communication. But other numbers are quite impressive at 1.5 million, 1.9 million, 4.4 million and 8.6 million. These are messages moved to very large audiences. The forty-seven million of ThinkProgress is a number that matches the reach of almost all counts of audience of political commentators. William O’Reilly has an audience of about 3 million for his Fox News broadcast (Kissel, 2014) and Jon Stewart’s audience is just over 2 million (O’Connell, 2013). The 47 million of ThinkProgress is a daily audience of 4.7 million. This is in the broadcast realm when it comes to reach.

Is ThinkProgress unique?

TweetTronics conducted 29 searches over an extended period of time. They find a sample of Twitter messages using the search terms specified. They also find the number of followers for each Twitter message they collect. Summaries were collected at two-month intervals 106 times. Each summary is the number of persons posting a Twitter message during the two months and the number of followers of each. These are very large numbers across all 106 collections. The number of “speakers” is 2,952,977 and the “audience” is 6,958,790,696. These are

Table 1. Reach of political organizations, 2012.

sums of the two month samples collected by TweetTronics. Since they are samples we know that these are very partial counts. What is not partial is the average number of followers. That can be computed within sampling error, but with numbers this large sampling error is miniscule by standard tests.

There are 106 collections of average number of followers per person posting a Twitter message. They range from 983 to 4885. All but three are in the range 983 and 3600. The mean is 2078. There is high variety and one could do more analysis to show what was related to the variation. But that is not the point here. The point is that political messaging via Twitter is accompanied by a very high follower rate. If there are 100 Twitter messages about a subject it would, on average, go to 207,800 followers. If there were a thousand you add three zeroes. And you get to millions very fast when you think about 755,000 twitter messages about the 2012 State of the Union message. For the average number of followers that would come to 1,568,890,000. Obviously that number is too large. That is far larger than the population of the US and any others who might be interested. But it shows that the potential reach of Twitter messages in politics is very great. And it shows the necessity of getting beyond very general aggregations for understanding the communication.

Broadcast media dominated the public domain—they were the public domain—because of their reach. It seems clear that the reach of political messaging on Twitter is at least equal to the reach of broadcast media. And this is only Twitter and not the other social media that have come into being to take advantage of the new technology for communication. The monopoly that was once broadcast media as public domain has been broken.

6. Interaction

By construction Twitter is a broadcast medium. A message is written and posted to Twitter. Others may find that message in a variety of ways, but in this basic structure there is no interaction. There is only broadcast and audience. But from the very beginning, users developed procedures that would facilitate interaction. The first convention developed was for identity. How do you let a person know that you are addressing him or her? Use the form @username; an invention in 2007 (Anarchogeek, 2012). That was followed by three other conventions.

One convention was the retweet which takes the form RT @originator-username and status message. A second was the hashtag which takes the form of #letters. The hashtag gets used for two principal purposes: identifying a subject for communication or identifying a group. The third convention was the shortened url. With a 140 character limit urls, which may be more characters than that, did not easily go into a Twitter message. The conversion of a complete url into a shortened version made including urls in a Twitter message quite feasible.

In all of these cases interaction is the driving force. And that distinguishes this communication from broadcast-audience. Suddenly the public domain has become interactive, which was never possible before.

7. Retweets

The standard form of a retweet is username | RT @authorname | status message It is a connection of three individuals or groups. It connects the author of the message and the person sending it forward and the followers of the person sending the message to them. They are joined in the very structure of the communication. Retweeting has been especially widely used when constituting a “we” was important. Social movements of all sorts need to think of themselves as a group, a we. This was important in the revolts of North Africa and the Middle East (Boynton, 2011b). And below evidence is presented that it was important in the occupy movement. But you can also trace this in specific policy concerns such as SOPA, PIPA and ACTA. Retweeting has been important in thinking as a we and organizing as a we.

Retweeting is a case in which interaction is “on the surface”. For every retweet there is a person who read the original message and then passed it along. When the percentage of retweets is high in a stream that means there is substantial reading as well as passing along in the stream. It becomes a stream of messages with high interaction among communicators.

The OccupyWallStreet movement used Twitter and retweeting extensively from its very beginning.

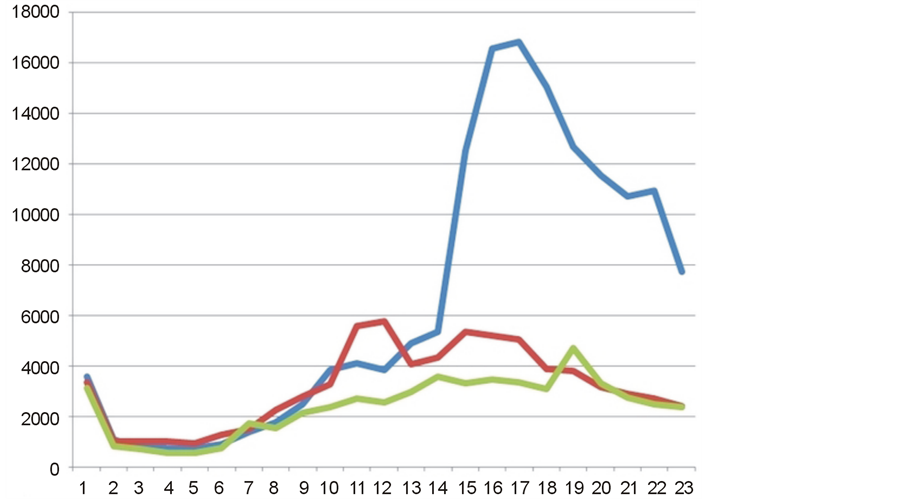

It started on Twitter as #DayOfRage. The New York Times report on the first day of protest, September 17, 2011, noted that “day of rage” was used by some of the organizers (Moynihan, 2011). The only place #OccupyWallStreet was found in the report was the photo that headed the story. Its beginnings can be traced back to the summer of 2011, but September was the first large scale public activity of the occupy movement, and it was the beginning of its utilization of Twitter (Boynton, 2012d). A few days later it moved from the New York Times local news page to the front page as protestors crossed Brooklyn Bridge and were arrested. On September 29th, the number of Twitter messages mentioning occupywallstreet was 55,263. On September 30, it was 72,952. And on October 1, the day of the march and arrests, the number was 150,381. That was a huge jump from the two previous days to the day of the march. And an hour by hour counting reveals that the jump starts with the arrests.

The green line in Figure 2 is September 29. The red line is September 30. And the blue line is October 1. The three lines are very similar until about 2:00 p.m. On October 1 at two p.m. twitter messages about #occupywallstreet took off in response to the march and the arrests. And it became hundreds of thousands of messages a day.

By December, the occupy movement had become a worldwide movement. And R-Shief offered access to a very large set of collections of Twitter messages about the occupy movement in its various locations to anyone who wanted to participate in a hack-a-thon analysis of the data (see Boynton, 2012b).

A preliminary point is the extent of retweeting in general Twitter messaging. In 2010, Sysomos found that only six percent of Twitter messages were retweets (Sysomos, 2010a). Twitter messages about the occupy movement were in a very different range. The percentage of Twitter messages that were retweets for the top ten in the R-Shief collections was, see Table 2.

Figure 2. Twitter messages mentioning #OccupyWallStreet.

Table 2. Retweets in occupy twitter messages.

Eighty percent, seventy percent, sixty percent and only two were in the fifties. By that point OWS had become the shorthand that was being used most widely. In addition to Wall Street, the messages were about the movement in Oakland, LA, Boston, San Francisco and Denver and numbered in the hundreds of thousands. And everywhere retweeting was off the charts. For the entire set of 235 collections the distribution is in the same range—eighty percent to fifty percent—with one or two exceptions. OccupySanta, for example, was used in 97 Twitter messages with only 15% retweeted.

Across this wide range of collections retweeting was many orders of magnitude greater than retweeting in general Twitter communication.

Two early studies provided a count of Twitter messages that were retweets. The 2010 report by Sysomos found that 6% of the Twitter messages in their sample were retweets (Sysomos, 2010a). A 2009 study found that 3% of the Twitter messages in their sample were retweets (Boyd et al., 2010). To make a direct comparison with those research reports the collections for the same time period are used. Their results are compared to 125 collections conducted between July of 2009 and March 2010 (Boynton, 2010). They were collections of streams of messages. So an important way to compare them is the length of time the data collection ran until there were so few messages being collected that the collection could stop.

The 125 studies are divided into quintiles in Table 3. The streams that lasted the fewest days lasted only between 1 and 12 days. That is the low end. Three fifths of the collections lasted 43 days or fewer. At the top 25 collections lasted between 136 and 244 days. This was before the occupy movement. It was before the revolts in North Africa and the Middle East in which retweeting was so prevalent. There was very little social movement in these streams, and that differentiates it from the occupy movement collections, for example.

The collections with the fewest retweets had between 4% and 27%, see Table 4. Collections in the median quintile have between 34% and 40% retweets. In the top quintile, the range of retweets per collection was 47% to 72%. There were no collections with as few as 3% retweets, which is what the 2009 study found for the sample of Twitter messages. More than four fifths of these streams had more than 6% retweets, which is what the 2010 study found. Even before the rise of major social movements messages about politics via Twitter were very far from the rest of Twitter messages in terms of retweets.

The conclusion to draw is that political messaging is much more interactive and much more about sharing than most uses of Twitter. And the public domain becomes co-motion as interaction becomes standard practice.

8. Hashtags

A hashtag is a # followed by a string of characters. Hashtags were invented by Twitter users because of the 140 character limit on the message (Gannes, 2010). If you want to communicate about the state of the union address you do not want to use 27 of the 140 characters on the title. So, #sotu serves as an abbreviation that others will recognize, search for, read, and include in their messages in their effort to communicate about the address. The point is communicating. Hashtag are used to constitute a domain of communication. This, #sotu, is where we communicate about the address before it starts, during the address, and after as well. If you are interested in communicating about the address this is the Twitter version of where to be (Boynton & Richardson, 2012). The same was true in 2009 and 2010 when people wanted to communicate about health care reform. The hashtag that became the locus for the communication was #hcr. If a message contained that hashtag people would find it, read it, and respond.

How important have hashtags been in political communication? In 2011, #Egypt was the most frequently used hashtag at Twitter, and #Jan25, which was the hashtag for the day of the revolution, was the eighth most used hashtag that year (Friedman, 2011). But hashtags, as ways to identify communication about the revolutions in North Africa and the Middle East, did not stop there. There was also #Feb14, which was the date of the

Table 3. Number of streams lasting number of days in quintiles.

Table 4. Percentage retweets per stream by quintile.

revolution in Bahrain; a revolution not as successful as Egypt. There was #Libya, #Syria, #Mar15, which was to be the day of the revolution in Syria, and #Yemen. As the movement for revolutions swelled so to did the number of messages being posted to Twitter and they, in very large numbers, used hashtags to identify a domain of communication, see Table 5.

Posting to Twitter did not start at the same time in the four countries. The posts for #Feb14 exploded on February 15 and 16. The messages posted using #Libya started later in February. The messages using #Syria started in March. And the #Yemen messaging started later in March. The totals in the table are as of the end of May. There were something over five million messages carrying the hashtags of the individual countries. These were separate domains of communication. The number of posts that contained two references are extremely small. (Boynton, 2012d) “Arab spring”, the western designation, was included in less than 1% of the messages using these hashtags. These were domains of communication about the countries by people most concerned with the individual country.

Twitter reported that 11% of messages contained hashtags in 2010 (Gannes, 2010). For the same period the percentage of hashtags in the 125 political messages collections of 2009 through 2010 divided into quintiles is presented in Table 6.

Four-fifths of the political streams had more hashtags than Twitter reported for all messages. Only the streams with the lowest percentage—1% to 13%—had fewer or as few as the general Twitter stream.

People using Twitter want to do more than broadcast. They want to engage in communication; they want interaction. One way to facilitate the communication is to identify a ‘marker’ for the subject of the communication. That is what hashtags are used to do. They are used to constitute a domain of communication. If you follow the hashtag you can know that you will find messages about this topic and people with whom you can communicate.

9. Shortened URLS

Adding a url to a Twitter message is bringing a non-Twitter source into the communication. But urls are long and 140 characters is a constraint. So shortened urls were invented. For a number of years the shortening was done by independent systems. Then Twitter decided to do shortening automatically, and most of those businesses went out of business. The objective is bringing media into the Twitter conversation that does not start with Twitter. There are two partially overlapping reasons for doing this. One is just to spread the word about something the person thinks is interesting or important. This is “hey, did you see...” The other use is as a justification for a claim. A claim is articulated and the reader is sent to a web based source where the claim is backed up.

One standard interpretation of Twitter messages “Is Twitter anything more than an online echo chamber?” which is the title of a post in the guardian online (Marcus, 2012). The argument of the article is twofold. One, the communication in Twitter is nothing more than an echo chamber, an amplification of, the news that can be found in the mainstream media. Two, the claim that people on Twitter only interact with people with whom they agree. So there is no debate. It is again just an echo. If the first claim was true then one would expect most of the urls to be references to reports in the mainstream media. The validity of this claim is examined here. For the second see (Boynton, 2012c).

It is possible to unshorten the shortened urls; they can be traced back to their source. In the 29 collections TweetTronics put together there were 73 two month summaries of the number of “traced” urls per domain. Generally the top ten domains are more than half of the urls found in the collection so the focus is on the ten most frequently cited domains in the 73 two month collections.

“Mainstream media” is an inexact phrase. The above is the list of media organizations that are counted as mainstream, see Table 7. They are media with a national audience. Local newspapers or local TV stations were

Table 5. Messages including these hashtags.

Table 6. Percentage per stream containing hashtag by quintile.

not counted as mainstream. Blogs like the Huffington Post or Hot Air or blogs of individuals were not counted. This is a very restrictive specification of mainstream, but having a national audience and a long history is implicit in most claims about Twitter messages repeating the news in mainstream media. Note that the counts are for domain names. It is the total of posts from ABC News or from CBS News or from The Washington Post. It is not a count of individual urls; it is a count of the domain or source of the url.

The question is how many of these mainstream media sources are included in the top ten most cited domains? If they dominate the top ten then the echo chamber argument has good support. If they do not dominate then there is question about the echo chamber argument.

In 48 of the 73 two month summaries there were no mainstream media, as defined here, in the top ten. That does not mean that there were no references to them. It just means the references were fewer in number. In the remaining 25 two month summaries the average number of references to the mainstream media domains was 5.8%. The range was from 0.06% to 8.7%.

If not the mainstream media then what? The first answer is that there were many potential sources—10 times 73. Domains that were referred to more than 10 times are shown in Table 8.

First, 280 compared to 730 clearly illustrates the diversity. Most of the domains were referenced fewer that ten times. Of the ones that were referenced more than 10 times only the Washington Post is a mainstream source. YouTube tops the list, and YouTube was the most frequently mentioned domain, number one, 23 times. The

Table 7. Mainstream media.

Table 8. In top ten references.

ones referencing Twitter are referring to other Twitter messages. With the exception of the ThinkProgress they are all well known. They just are not the media that people normally have in mind when making the echo chamber claim.

There is not much support for the echo chamber argument.

What this indicates is that a very diverse set of media, or ideas, are being brought into the Twitter conversation using urls. Twitter users are pulling a much broader array of sources into the communication than one would find in mainstream media. And that means that many sources, as well as many individuals, are finding voice in the new world of co-motion.

10. Co-Motion

The framework for understanding political communication has been broadcast-audience. However, the infrastructure undegirding political communication has changed; the internet and the new media systems built on top of it have provided opportunities that did not exist before. This report has reviewed some of the ways people have taken advantage of the changes. In particular, the focus has been on how the public domain has been and is being reconstructed using communication software that is public and that is able to reach others around the world. The new framing suggested is co-motion. The point is to emphasize the interaction that has become the newly reconstructed public domain. By examining the use of Twitter it is possible to assess the extent to which the new social media are used for political communication, the potential reach of that communication, and the interaction as users address each other and the communication emanating from broadcast media.

This report has focused on the interaction of individual users of Twitter. If the co-motion framework is plausible what research should be next? One, much more attention is needed in tracking the interaction of individual communication and broadcast communication. How is the attention of the two streams the same and different? How are the dynamics similar and dissimilar? Is one stream more episodic than the other, for example? How is the communication of the new media being brought into the reporting of the broadcast media? What additional broadcast media are being brought more fully into the public domain? Two, more research is needed on the spread of communication in the network. The Pew Research Internet Project has made an important start in a recent report mapping clusters in social media communication (Smith et al., 2014). But there is much more research to be done to determine the conditions that lead to various patterns of spread through the network. Three, more research needs to be done on how political leaders enter this field of activity. The research on congress, and political leaders in general, using social media is still primarily focused on who is using social media. Little has been done on how it is being used, and how the uses change as political leaders become more experienced with the new possibilities. Fourth, the promise of the infrastructure is global communication. Research is needed on how this opportunity is being utilized by citizens of the world. What kind of communication reaches across borders?

Co-motion is what is happening in political communication. And it is a challenge to our standard practice as communication scholars. We have fine honed procedures for dealing with broadcast-audience. The temptation to reduce this new public domain back to what we have known before is there. But it is new, and we need new ideas and new technologies to explore how it is new. That is our challenge now.

References

- Anarchogeek (2012). Origin of the @Reply—Digging Through Twitter’s History.

- Andrews, R. (2012). New BBC Chief Vows to Re-Invent Content, Not Just Re-Purpose It. http://paidcontent.org/2012/09/18/new-bbc-chief-vows-to-re-invent-content-not-just-re-purpose-it/

- Bennett, L., & Iyengar, S. (2008). A New Era of Minimal Effects? The Changing Foundations of Political Communication. Journal of Communication, 58, 707-731.

- Bennett, S. (2012). Twitter on Track for 500 Million Total Users by March, 250 Million Active Users by End of 2012, All Twitter. http://www.mediabistro.com/alltwitter/twitter-active-total-users_b17655

- Boyd, D., Golder, S., & Lotan, G. (2010) Tweet, Tweet, Retweet: Conversational Aspects of Retweeting on Twitter. 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, 6 January 2010, 1-10.

- Boynton, G. R. (2010). Politics Moves to Twitter: How Big Is Big and Other Such Distributions. http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/distributions/politics-moves-twitter.html

- Boynton, G. R. (2011a). A Day of Protest. http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/day-of-protest/day-of-protest.html

- Boynton, G. R. (2011b). RT @bobboynton New Media and the Revolting Middle East. http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/retweet-community-isa2011/twitter-bahrain-revolt.html

- Boynton, G. R. (2011c). The “We Move” in #Occupy... http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/we-move/we-move-retweet.html

- Boynton, G. R. (2012a). Supreme Court and Health Care; Tracking the Focus of Attention. http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/attention-obamacare-court/focus-attention-obamacare-court.html

- Boynton, G. R. (2012b). Political Organizations and the Magic of Retweeting. http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/pol-groups-multiplier/pol-groups-retweet.html

- Boynton, G. R. (2012c). Shouting across Divides. http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/shouting-across/shouting-across-divides-120422.html

- Boynton, G. R. (2012d). Arab Spring from the Ground up. http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/arab-spring/isa-arabspring-120327.html

- Boynton, G. R., & Richardson, G. (2012). Reframing Audience; Co-motion at @#SOTU. http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/state-union-2010-11-12/sotu-RSA-120424.html

- Douglas, N. (2007). Twitter Blows up as SXSW Conference. Gawker. http://gawker.com/243634/twitter-blows-up-at-sxsw-conference

- Farber, D. (2012). Twitter Hits 400 Million Tweets per Day, Mostly Mobile. CNET. http://news.cnet.com/8301-1023_3-57448388-93/twitter-hits-400-million-tweets-per-day-mostly-mobile/

- Fraser, L. (2014). Farewell, #Sochi2014. Twitter Blog.

- Friedman, U. (2011). The Egyptian Revolution Dominated Twitter This Year. FP Foreign Policy Magazine. http://blog.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2011/12/05/the_egyptian_revolution_dominated_twitter_this_year

- Gannes, L. (2010). The Short and Illustrious History of Twitter #Hashtags. Gigaom. http://gigaom.com/2010/04/30/the-short-and-illustrious-history-of-twitter-hashtags/

- Karpf, D. (2008). Understanding Blogspace. Journal of Information Technology and Politics, 5, 369-385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19331680802546571

- Kissel, R. (2014). Obama Interview Lifts Fox News’ “O’Reilly Factor” to Largest Audience in 10 Months. Variety.

- Moynihan, C. (2011). Wall Street Protest Begins, with Demonstrators Blocked, City Room. New York Times. http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/17/wall-street-protest-begins-with-demonstrators-blocked/

- O’Connell, M. (2013). TV Ratings: Jon Stewart Lifts “Daily Show” Audience upon Return. The Hollywood Reporter.

- Smith, M., Rainie, L., Shneiderman, B., & Himelboim, I. (2014). Mapping Twitter Topic Networks: From Polarized Crowds to Community Clusters. Pew Research Internet Project.

- Sysomos Resource Library (2010a). Replies and Retweets on Twitter. http://www.sysomos.com/insidetwitter/engagement/

- Sysomos Resource Library (2010b). Twitter Statistics for 2010. Sysomos, Inc. http://www.sysomos.com/insidetwitter/twitter-stats-2010/

- Taintor, D. (2012). NY Times’ Jim Roberts: “The Pace of Change Gets Faster and Faster”. TPM. http://talkingpointsmemo.com/idealab/ny-times-jim-roberts-the-pace-of-change-gets-faster-and-faster

- Twitter Blog (2012a). A New Barometer for the Election. http://blog.twitter.com/2012/08/a-new-barometer-for-election.html

- Twitter Blog (2012b). Election Night 2012. http://blog.twitter.com/2012/11/election-night-2012.html

- Twitter Blog (2012c). Follow the State of the Union on Twitter. http://blog.twitter.com/2012/01/follow-state-of-union-on-twitter.html

- Twitter Blog (2012d). Olympic (and Twitter) Records. http://blog.twitter.com/2012/08/olympic-and-twitter-records.html

- Wallsten, K. (2010). “Yes We Can”: How Online Viewership, Blog Discussion, Campaign Statements and Mainstream Media Coverage Produced a Viral Video Phenomenon. Journal of Information Technology and Politics, 7, 163-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19331681003749030

- Weil, K. (2010). Measuring Tweets, Twitter Blog. http://blog.twitter.com/2010/02/measuring-tweets.html