Open Journal of Modern Linguistics

Vol.04 No.05(2014), Article ID:51581,13 pages

10.4236/ojml.2014.45053

Arabic Language Teachers in the State of Michigan: Views of Their Professional Needs

Hassan Wafa

Michigan Arabic Teachers’ Council, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, USA

Email: wafa.hassan@wmich.edu

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 2 September 2014; revised 17 October 2014; accepted 2 November 2014

ABSTRACT

A full-day summer conference directed by this investigator took place in Dearborn city under the umbrella of Western Michigan University for professional development of Arabic teachers serving public, private, and academic charter schools in Michigan. The theoretical framework for conducting the conference was focused on the issue of teaching strategies as well as the needs assessment of teachers for improving their professional development. A group of fifty teachers volunteered to participate in the conference and were asked to complete a twelve-item questionnaire designed to provide their professional profile and their preference in developing professional development. Their professional profile included years of Arabic teaching experience in the United States, teaching level (elementary school, middle school, or high school), teaching certificate, academic credentials, and type of school (public, private, or charter school). The findings indicated that among the ten sub-items related to the professional development skills of the teachers, “Implementing differentiated language instruction” was rated by the participating teachers as the most important components of their professional development skills; followed in order by “Integrating technology and Arabic instruction”; “Using effective learner-centered teaching strategies”; “Using and maintaining Arabic language”; “Implementing a standards-based curriculum”; “Developing curriculum and thematic units”; “Implementing performance assessment methods”; “Conducting constructive action research in Arabic instruction”; “Conducting the Oral Proficiency Interview”; and “Learning how to be a certified Arabic language teacher in Michigan”. In response to the questions regarding the role of Council in supporting Arabic teachers, the participating teachers made a number of constructive suggestions to help improve the quality of teaching Arabic with special focus on facilitating appropriate teaching materials and other instructional tools as a part of curriculum development.

Keywords:

Professional Development, Performance Assessment, Standard-Based Curriculum, Language Proficiency, Heritage and Non-Heritage Students

1. Introduction

Since September 11, 2001, teaching Arabic in the United States has become the focus of more attention from the educational community. In August 2002, the United States Department of Education created the National Middle East Language Resources at Brigham Young University to focus on languages of Middle East (Morrison, 2003) . As indicated by Morrison, the funding for this program reflected the federal government’s growing awareness of the need to focus on enhancing the nation’s understanding of Middle East affairs and languages. While at the time teaching Arabic in elementary and secondary schools was not nearly as the teaching of Western European languages such as French, German, and Spanish, there has been an increase demand for teaching Arabic, particularly in private schools (Morrison, 2003) .

Today, Arabic is one of the fastest-growing foreign languages currently taught throughout schools and colleges in the United States. According to Heldt (2010) , the largest population of native Arabic speakers resides in heavily urban areas such as Los Angeles, Detroit, Chicago, and New York City. Detroit and the surrounding areas of Michigan host one of the largest Arabic-speaking populations including many from Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon. A vast majority of educated Arab professionals who immigrate to the United States are often fluent in English, as it is widely used in the Middle East. Many Lebanese and Arab-speaking immigrants from North Africa are to some extent fluent in French (Heldt, 2010) .

According to the United States Department of Commerce (Washington, D.C., 2012) , based on the data reported by the U.S. Census Bureau, during the year 2010 California shared the largest number of Arabic speakers (158,398), followed in order by Michigan (101,470), New York (86,269), Texas (54,340), Illinois (53,251), New Jersey (51,011), Virginia (36,683), Florida (34,698), and Ohio (33,125). Based on the statistics derived from U.S. Census Bureau, in 2010 Lebanese were found to be the largest populated Arab speakers in the United States (501,988), followed by Egyptians (190,0781), Syrian (148,214), Iraqi (105,981), Palestinian (93,438), Moroccan (82,073), Jordanian (61,664), Yemeni (29,358), and Algerian (14,716).

Undoubtedly, the population of Arab communities throughout the United States is growing rapidly as a result of daily routine migration and growth of second generation. Detroit alone shares the most populated Arabs from a variety of Middle East countries as well as other Arabic speaking countries in North and South Africa. In fact, Arabic is the second language in Detroit and some other metropolitan areas in the State of Michigan. Therefore, district schools in Michigan are currently facing the shortage of certified Arabic speaking teachers to fulfill the educational needs of Arab students. Fortunately, today there are numerous educational institutions that offer Arabic courses for students as well as a variety of workshops and seminars designed to fulfill the professional development needs of both heritage and non-heritage Arabic speaking teachers. Some of these institutes include: American Association of Teachers of Arabic (2014) ; Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition Summer Institute (2014) ; Brigham Young University Startalk Arabic Language (2010) ; Columbia University Summer Arabic Program (2014) ; Georgetown University Arabic Language Institute (2013) ; George Washington University Intensive Arabic Program (2014) ; Pennsylvania State University Arabic Language Program (2014) ; State University of New York (2013) ; University of California Arabic Teacher Preparation (2014) ; University of Maryland Intensive Arabic Language Program (2012) ; University of Michigan Summer Arabic Language Program (2014) ; University of Minnesota Intensive Arabic Teacher Training (2014) ; University of Pennsylvania Summer Arabic Program (2013) ; University of Wisconsin Summer Arabic Program (2012) ; and many more.

Another line of workshops is offered by a large number of higher education institutions through STARTALK which is a federally funded program launched as a new component of the National Security Language Initiative announced by former President Bush in January 2006. Startalk’s original mission is to increase the number of Americans learning and speaking foreign languages. It is also designed to provide students at all levels of education (K-16) with an opportunity to learn the foreign languages of their choice. Most importantly, it is designed to offer teachers of critical languages creative teaching strategies: (a) to exemplify best practices in language education and in professional development; and (b) to establish teaching policies and practices that seek continuous improvement in such criteria as standards-based curriculum planning, outcomes-driven program design, learner-centered approaches, excellence in selection and development of teaching materials, and meaningful assessment of program outcomes (cited by University of Maryland: National Foreign Language Center, 2014). In fact, since 2007 this investigator has been in charge of conducting a number of STARTALK programs designed for improving the quality of Arabic language for teachers and students in the state of Michigan through Michigan State University as well as Western Michigan University.

Qatar Foundation International is one of the most promising organizations which provide appropriate grants to numerous institutions of higher education and other educational organizations across the United States to offer best practices in teaching Arabic as a second language. It is a non-profit member of Qatar Foundation in the United States with a shared mission to connect cultures and advance global citizenship through the world of education. It also supports teachers Councils in several metropolitan areas including Chicago, Los Angeles, Michigan, and Washington, D.C. Some of the major responsibilities of these Councils are to strengthen local Arabic programs by setting up a forum for Arabic teachers to share innovative teaching approaches, as well as providing outreach to teachers, parents, and community at large. The role of each Council is also crucial in strengthening and enriching the goals of Qatar Foundation International to improve Arabic language education by helping teachers support each other. In cooperation with Qatar Foundation International, the following universities and other educational institutions facilitate Regional Teacher Councils.

DePaul University and the Center for Arabic Language and Culture: Chicago Arabic Teachers’ Council serves in collaborative project supported by the Qatar Foundation International and joint cooperation of DePaul University (2014) and the Center for Arabic Language and Culture. The goal of the Council is to ensure quality of Arabic teaching, by providing training, seminars, and workshops to support the community of Arabic teachers within the Chicago land area. The Council is primarily organized to help fulfill the needs of Arabic language teachers and administrators throughout Chicago, including public, private, and religious schools teachers. The Council further provides teacher training and professional development opportunities, while supporting teacher certification and encouraging others to join in the field of teaching Arabic.

Occidental College of Foreign Language Project: The Southern California Arabic Language Teachers’ Council located in Los Angeles is hosted by the California World Language Project at Occidental College (2014) . The Council assists Arabic language educators to meet and share ideas about teaching Arabic in a variety of institutions. The Council also helps those schools that are interested in starting new programs, reach out to communities and encourage them to advocate for Arabic language and culture programs in their school districts. The Council organizes workshops and cultural events for Arabic language teachers across Southern California.

Western Michigan University: The Michigan Arabic Teachers’ Council assists a large number of Arabic teachers in the Detroit Metropolitan Area and Dearborn with the most populated Arab from different countries in the Middle East. The Council also serves Arabic teachers throughout Michigan State and specifically those teaching in Detroit area district schools. It is interesting to know that all activities of the Council are determined by the teachers of Arabic language themselves.

George Mason University: The major role of Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area Arabic Teachers’ Council in collaboration with the George Mason University (2014) is to involve Arabic teachers in carefully structured learning sequences that provide critical and yet feasible training procedure. The executive committee of the George Mason University is comprised of volunteer teachers from the public, private, and parochial schools throughout the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area.

2. Literature Review

Today, more professional development opportunities exist for teachers of Arabic language than ever before. As reflected in the introduction there are numerous institutions of higher education and other educational organizations that offer professional development courses, workshops, conference, and other training activities to enhance the quality of teaching for Arabic teachers across the nation. This review presents a number of teacher preparation opportunities for Arabic teachers as related to the purpose of this study.

Professional development of teachers of second-language learners has been thoroughly discussed by August and Shanahan (2006) in their interesting book which mainly concentrates on a broad number of issues related to teaching strategies and end results assessment. The authors tackle on a variety of strategies for professional development of teachers with regard to five specific policies and procedures, including development of literacy among second-language learners, cross-linguistic relationships among second-language learners, socio-cultural context and literacy development, strategies for educating language-minority students, and student assessment. According to the authors, teachers’ professional development will be assessed based on their quality of job performance as related to the aforementioned instructional strategies.

A study was conducted by Mona (2012) to examine the effectiveness of a STARTAL training program in professional development of a group of Arabic teachers. A survey instrument was used to explore perceptions of these teachers regarding the extent to which the major goals and objectives of the training have been achieved. The findings indicated that the training initiatives tend to emphasize on pedagogical knowledge and skills rather than content knowledge. The findings further indicated that such initiatives also tend to focus on some Arabic teacher approach professional development with fundamental goal of gaining knowledge and skills rather than earning a degree or certification.

Since 1996, the Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition (2014) at the University of Minnesota has sponsored a variety of summer session programs for second language teachers including teachers of Arabic language. This internationally known program reflects commitment of the institution to link research and theory with their practical applications in the classroom. The programs are highly interactive and include theory-building, hands-on activities, discussion, and plenty of networking opportunities after completion of the program.

Sponsored by Qatar Foundation International, Concordia Language Villages (2013) offered two professional development workshops for current and future teachers of Arabic language. The project brought together Arabic teachers of elementary, middle, high schools as well as higher education institutions from across the United States with two exciting opportunities to participate in professional development programs. The workshop themes included “Staying in the Target Language in the Arabic Language Classroom”, and “Integrating Culture into Arabic Language Classroom”. The workshops were designed to have teachers learn how to empower students and themselves to use Arabic 90% of the time in the classroom. The participants will also learn to share ideas for group work and presentations along with implementation of proper resources and creative teaching strategies.

The National Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Language (2014) serves educators in all foreign languages, at all levels from kindergarten through higher education in both public and private settings. It is the largest of five regional associations of its kind in the United States. Its mission is “to anticipate, explore, respond to, and advocate for constituent needs; to offer both established and innovative professional development in support of language teachers and learners; and to provide opportunities for collegial interchange on issues critical to the profession.” Its sixty-first anniversary was held in Boston in spring 2014.

During the fall semester of 2013, Aldeen Foundation developed and facilitated a six-week online course for 40 teachers of Arabic language to learn about creative interactive Arabic activities and to implement the effective activities in the classroom. The course was taught by expert instructors in the field with presentation of best practices, lectures, quizzes, and providing online opportunities for networking and consultation.

Each year from 2011 to 2014, Qatar Foundation International has provided high-level sponsorship of the annual conference held by American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Language raising the generous commitment and viability of Qatar Foundation in the field of language education. Each year Arabic teachers are invited to attend special workshops for professional development. In 2013, for example, more than 200 teachers and administrators participated in the annual reception to celebrate the teaching of Arabic.

In July 2013, a unique online training course was offered by the National Middle East Language Resource Center to help the interested Arabic teachers develop their own highly effective programs and share them with others. The course was designed to promote self-efficiency and strategic self-regulation into account for producing the best learning outcomes. Participating teachers learned to build articulated learning sequences appropriate to their students’ need and maturity in a manner to compete with national language learning standards.

In March 2014, the Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages held a conference in Boston and offered a wide range of outstanding professional development opportunities and the sustaining experience of a true learning environment. As a result those who participated in the conference reported to have discovered new ways of supporting language programs suitable to their professional needs.

Through Arabic Language Programs, American Association of Teachers of Arabic (2014) offers summer intensive training courses in Arabic to those who are interested in learning Arabic. The association’s major goals and objectives focus on promoting research and instruction in the field of Arabic language pedagogy, as well as Arabic literature.

3. Purpose of the Study

The major purpose of this study is to evaluate the perceptions of a group of Michigan Arabic language teachers regarding their interest in development of their professional skills based on certain components including: (a) Implementing differentiated language instruction, (b) Implementing a standards-based curriculum, (c) Developing curriculum and thematic units, (d) Using effective learner-centered teaching strategies, (e) Using and maintaining Arabic language, (f) Implementing differentiated language instruction, (g) Integrating technology and Arabic instruction, (h) Implementing performance assessment methods, (i) Conducting constructive action research in Arabic instruction, (j) Learning how to be a certified Arabic teacher in Michigan, and (k) Conducting the Oral Proficiency Interview. The study is also designed to determine the teachers’ envision of the Council’s role to support teachers of Arabic language in Michigan. The study was further designed to explore how the teachers enrich the Council. In addition, a professional profile of the participating teachers will be presented to have a better understanding of the sample included in the study.

4. Methods and Procedures

Participating Teachers: The target population for the study included teachers of Arabic language in the State of Michigan. An invitation letter was sent to these teachers with a detail of the project’s objectives to encourage them for participation. As a result only 50 teachers accepted the invitation and decided to enroll for a full-day conference. They comprised of heritage Arabic speakers, non-heritage Arabic Speakers, and a combination of both. As compared to native Arabic speakers, heritage speakers refer to those who have been exposed to Arabic language at home or when they were young. Otherwise, they are considered as non-heritage speakers.

Survey Instrument: The data for this study was collected from the participating teachers through the use of a twelve-item questionnaire. Of the total twelve items, seven were designed to provide a professional profile of the participating teachers, two items were included to determine their preference in attendance to a full-day conference and their interest in presenting at the conference, two open-ended items to seek their perceptions regarding their envision of the Council’s role and how they enrich the Council, and one item to determine their preference in developing professional development. After collection of the data, two of the questionnaires were missing too many items that were not appropriate to be included in data analysis.

Data Analysis: Analysis of the data was conducted through the use of quantitative and qualitative methods. The quantitative analysis of the data was achieved by applying frequency distribution of most items of the questionnaire as well as computation of a measuring item of the questionnaire. The qualitative analysis of the data was achieved by categorizing and reporting the responses of the participating teachers to the open-ended items of the survey.

5. Findings

The findings are presented into three parts. The first part includes a professional profile of the participating teachers as a result of analyzing their responses to certain items related to their educational background as well as their teaching experiences. The second part provides the resulting analysis of the data related to their professional development. The third part presents an analysis of their responses to the open-ended items of the questionnaire.

Part 1: Professional Profile of the Participating Teachers

A professional profile of the teachers who participated in this training program was conducted through the use of frequency distribution of the participating responses to certain items of the questionnaire presented below:

Years of Arabic Teaching in the United States: As shown in Table 1, of the total participating teachers, 54.2% reported to have less than six years of teaching Arabic in the United States, 29.2% had between six to ten years of experience, and the remaining 16.7% indicated to have more than ten years of experience in teaching Arabic.

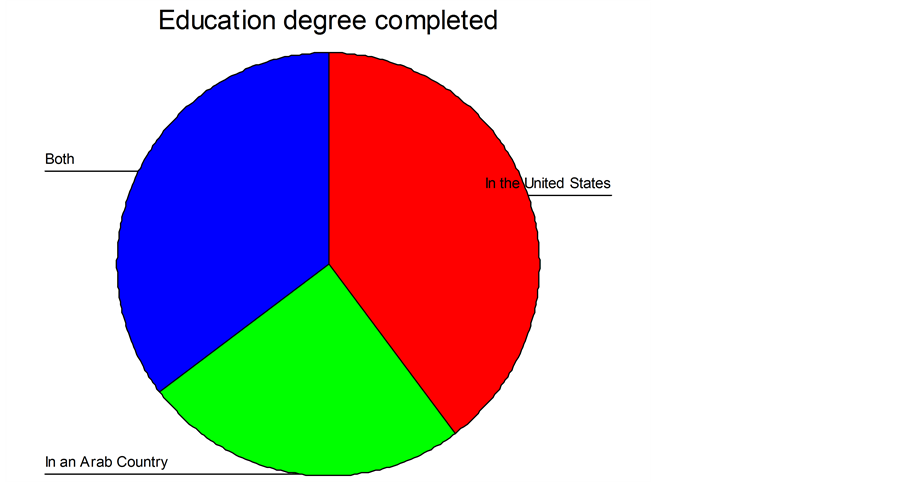

Educational Background of the Participating Teachers: Table 2 presents a breakdown of the participating teachers by where they completed their educational degrees. As a result, 39.6% indicated they have received their degrees in the United States, 25.0% had received their degrees in an Arab country, and the remaining 35.4% had finished a part of their education overseas and then completed their degrees in the United States.

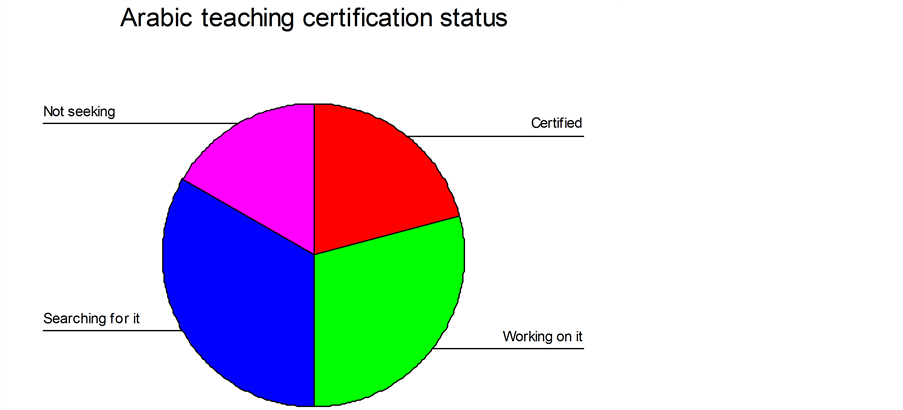

Certification Status of the Participating Teachers: Table 3 provides frequency distribution of the participating teachers based on their certification status. The findings indicate that only 20.8% of these participants reported to be a certified Arabic teacher, 29.2% indicated they are working on their certification status, 33.3% said they are looking for information to learn how to get certified, and the remaining 16.7% showed no interest in looking for certification. This indicates that only one out of five teacher were certified in teaching Arabic.

Table 1. Years of experience of the participating teachers.

Table 2. Educational background of the participating teachers.

Table 3. Certification status of the participating teachers.

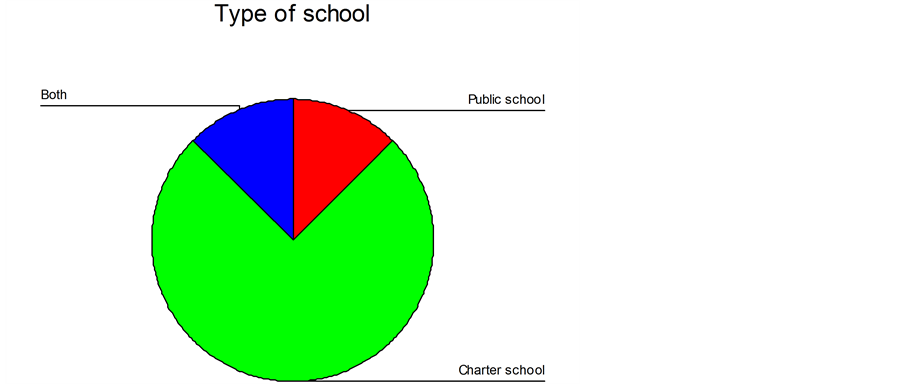

Teaching Experience of the Participating Teachers by Type of School: As shown in Table 4, a relatively large percentage of 75.0% of the participating teachers reported to have worked in charter schools, whereas only 12.5% were working in public school districts and another 12.5% were working in private schools.

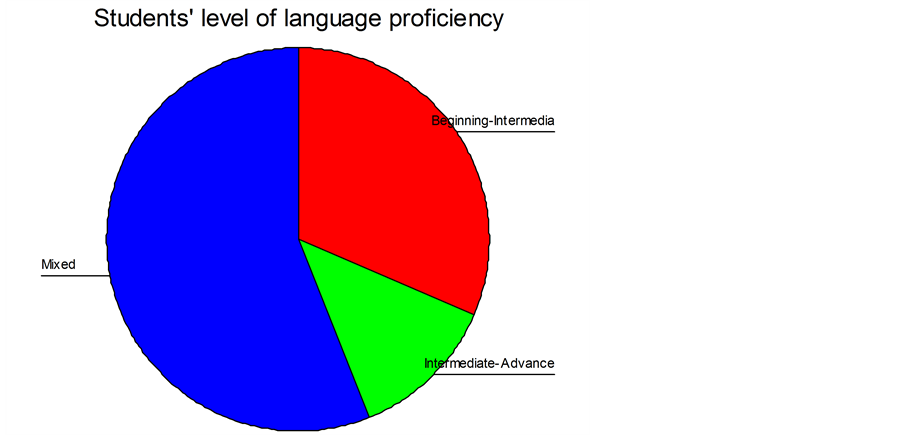

Students’ Level of Language Proficiency: The data in Table 5 indicated that 31.3% of the participating teachers perceived their students’ language proficiency fall between beginning and intermediate levels, 12.5% fall between intermediate and advanced, and the remaining 56.3 of their students have a mixture of all proficiency levels.

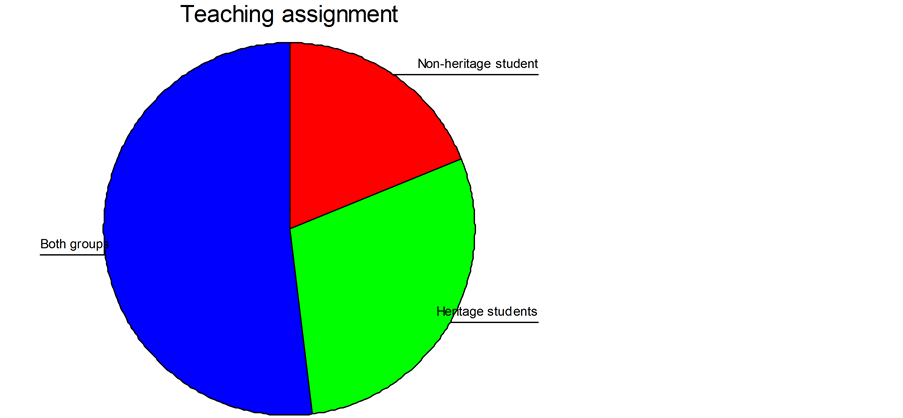

Heritage and Non-Heritage Students: Table 6 provides an estimation of the proportion of heritage and non-heritage students as perceived by the participating teachers. According to the data in this table, approximately 29.2% of the students were heritage case whose parents were originally Arabs, 18.8% of the cases were Arabic language learners who were non-heritage students, and the remaining 52.1% were considered as mixed of heritage and non-heritage cases.

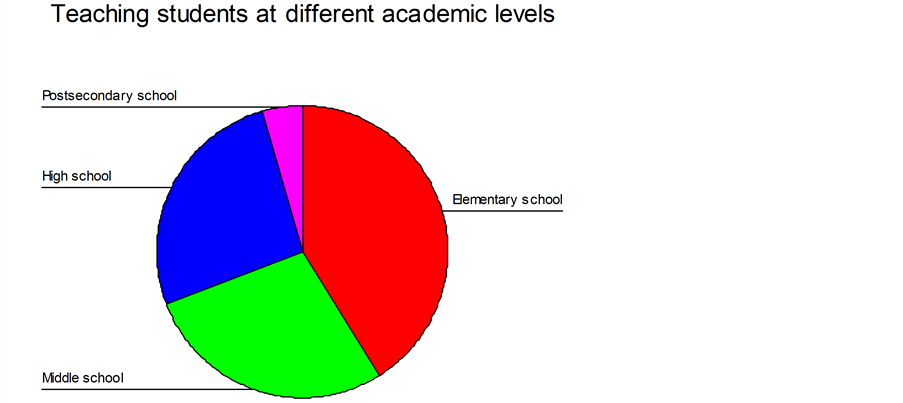

Teaching Experiences of the Participating by Academic Level: As reflected in Table 7, the participating teachers had working experiences with students at different academic levels as follows: (a) 58.3% indicated to have taught students at the elementary level, (b) 39.6% had taught students at middle schools, (c) 37.5% had taught students at high school, and (d) only 6.3% of the respondents reported to have taught students at the post-secondary level.

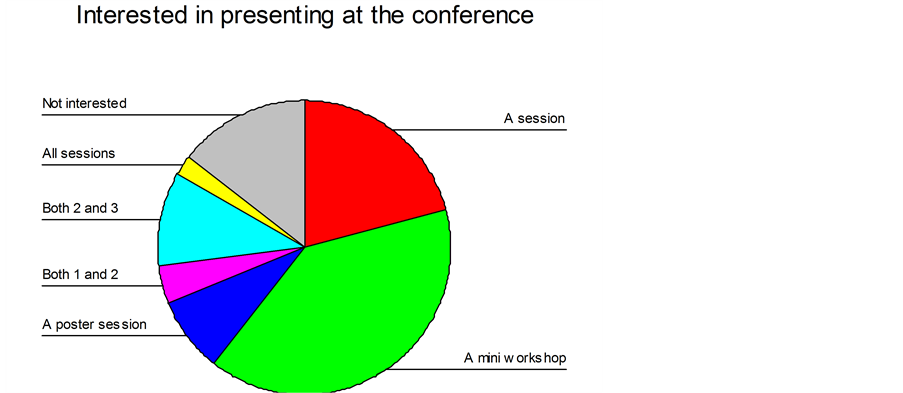

Respondents’ Interest in Presenting at the Conference: According to the data in Table 8, the teachers were found to be interested in presenting at the conference with a 20.8% found to be interested in presenting at a session, 39.6% were interested in presenting at a mini workshop, 8.3% were interested in presenting at a poster session, 4.2% showed interest in presenting at both a session and a mini workshop, 10.4% were interested in presenting at both a mini workshop and a poster session, 2.1% showed interest in presenting at all three sessions, and 14.6% were not interested in presenting at the conference.

Part 2: Teachers’ Interest in Developing Professional Skills

In this part, a descriptive analysis of the data was conducted to determine the mean and standard deviation of the rating assigned by the participating to each of the ten components related to their teaching and professional

Table 4. Teaching experience of the participating teachers by type of school.

Table 5. Students’ level of language proficiency perceived by the teachers.

Table 6. An estimation of the proportion of heritage and non-heritage students.

Table 7. Teaching experiences of the participating by academic level.

Table 8. Respondents’ interest in presenting at the conference.

skills. The ratings assigned by the participating teachers to each of the ten sub-items related to their professional skills ranged from 1 for the most degree of interest to ten for the least degree of interest. As may be seen in Table 9, among the ten items related to the professional development skills of the teachers, “Implementing differentiated language instruction” was rated an average of 3.06 by the respondents as the most important components of their professional development skills; followed in order by “Integrating technology and Arabic instruction” with an average ratings of 3.35; “Using effective learner-centered teaching strategies” with an average ratings of 3.50; “Using and maintaining Arabic language” with an average ratings of 3.81; “Implementing a standards-based curriculum” with an average ratings of 4.15; “Developing curriculum and thematic units” with an average rating of 4.56; “Implementing performance assessment methods” with an average ratings of 4.85; “Conducting constructive action research in Arabic instruction” with an average ratings of 5.02; “Conducting the Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI)” with an average ratings of 5.60; and “Learning how to be a certified Arabic language teacher in Michigan” with an average ratings of 6.02.

Part 3: Teachers’ Responses to the Open-Ended Items of the Questionnaire

This part deals with a qualitative method which is conducted to analyze the responses of the participating teachers to the following two open-ended items of the questionnaire. Responses to each item were listed for review and analysis. After reviewing the individual responses, they were categorized into different themes for analysis and interpretation. Those responses that were interesting and could not fall into any special category were presented through direct quotations.

5.1. Please Write How You Envision the Council’s Role to Support Arabic Teachers in Michigan

The following provides a collective response of the teachers to this particular issue which reflects their percep-

Table 9. Respondents’ interest in developing professional skills.

Note: Mean ratings are based on the scale of 1 for the most to 10 for the least important interest.

tions regarding the Council’s role to support Arabic language teachers in Michigan.

The role of Council in supporting Arabic language teachers was found to be substantially important for a number of prominent reasons to: (a) provide opportunities for teacher training and special workshops; (b) facilitate teachers with appropriate teaching materials and other instructional tools as a part of curriculum development; (c) establish coordinating efforts between teachers and Council to design and implement appropriate curriculum suitable to the needs of teachers and students; (d) encourage foreign language teachers to get certified by providing them with opportunities to ease up the process of certification; (e) bring university professors and other experts in the field of foreign language to school districts as a part of training initiatives; (f) help advising Arabic language teachers how to improve their teaching strategies in accordance with the needs of students; (g) create a special network for Arabic language teachers to communicate with each other and to share their ideas to improve their students’ learning process; and (h) help improve the quality of Arabic language teaching strategies by collecting appropriate data from Arabic language teachers and by implementing the most effective strategies recommended by the teachers.

In addition to the aforementioned viewpoints, the following quotations can be addressed further to reflect the perceptions of the participating teachers regarding this issue of concern:

“Arabic teachers are facing lots of questions that need to be answered. The council is a reference where we can find an answer to all what we need. It will support us in maintaining the Arabic language and developing our curriculum.”

“The Council’s role is to make sure that teachers have the required materials, instructional tools and the preparation to teach the students Arabic efficiently. Furthermore, to produce fluent Arabic students who can speak, read and write Arabic. In addition, they should appreciate language and culture.”

“One of the most important ways to support teachers of Arabic is to form an information sharing online source, because it’s easier to exchange ideas and information online allowing flexibility in terms of the time in which each instructor can connect and help other teachers.”

“The Council’s role should be effective for both teachers and students. He or she is supposed to try to find standards for Arabic language that works for all students, coordinate with a better curriculum, and shares the data concerns and needs of students/teachers with the board.”

“We need a council like this to share ideas and get the appropriate workshops that we need. We need to learn the new strategies and things that are related to the foreign language education field. This council will be the bridge between us and our needs.”

5.2. Please Write as an Experienced Teacher of Arabic How You Will Enrich the Council

The following provides a collective response of the participating teachers regarding how to enrich the Council to ask questions and make suggestions reflecting their issues of concern:

In order to enrich the Council for improving the quality of teaching Arabic, the participating teacher recommended to: (a) recognize the potential needs of heritage and non-heritage students who are willing to learn Arabic; (b) provide the Council with different motivational and successful strategies suitable to the language learning needs of students; (c) integrate the role of technology in teaching Arabic classrooms as a part of effective teaching strategies; (d) provide other effective teaching strategies to improve the quality of teaching Arabic language; (e) share the ideas of how to deal with the typical problems in the Arabic classroom; (f) support all creative ideas for improving the quality of teaching Arabic school-wide; (g) offer conferences to Arabic language teachers to share their teaching strategies through a brainstorming progressive strategy; and (h) provide feedback and meaningful assessment strategies to the Council in order to explore effective methods and procedures implemented for a successful outcomes.

The following also provides interesting quotations from the participating teachers that can further express their perceptions regarding this issue of concern.

“I will enrich the Council by active member in the network for communication and provide ideas and strategies to others. Also, I can help in the planning and presentation of professional development sessions to Arabic language teachers.”

“I will transfer my knowledge of working with different levels in one class to emphasize on how to differentiate instruction, how to improve students’ performances, how to align the Arabic language with English, and how to persuade parental awareness.”

“I think sharing ideas and experiences would help a lot in taking decisions for recommendation and identifying major school strengths in Arabic and the areas that we can improve. Workshops will also prepare us in an accreditation a work team.”

“I suggest keep searching about the week plans in teaching Arabic as a second language by visiting different schools and different levels of the students they have to search for a solution for any problems face them as a teacher.”

“I recommend providing feedback that will help Arabic teachers implement teaching strategies to teach Arabic. Provide teachers with Arabic materials (Arabic curriculum), and sharing ideas such as integrating technology in teaching Arabic language.”

6. Conclusion and Implication

Based on the qualitative analyses of the open-ended items of the questionnaire, it can be concluded that Arabic language teachers need certain training initiatives to improve the quality of their professional skills. Such initiatives should include providing opportunities for special workshops; facilitating teachers with appropriate teaching materials and other instructional tools as a part of curriculum development; designing and implementing appropriate curriculum suitable to the needs of teachers and students; creating a special network for Arabic language teachers to communicate with each other and to share their ideas for improving their students’ learning process; and improving the quality of Arabic language teaching strategies by collecting appropriate data from these teachers and by implementing the most effective strategies recommended by the teachers. As a result of quantitative analyses of the data, it can be concluded that the participating teachers were mostly interested in developing their professional skills with concentration on implementing differentiated language instruction; integrating technology and Arabic instruction; using effective learner-centered teaching strategies; using and maintaining Arabic language; and implementing a standards-based curriculum.

A number of implications are derived based on the findings of this study and in accordance to the overall findings reported in the literature review. First of all, the findings imply that as a result of teacher training, Arabic teachers can substantially improve their professional development and consequently enhance the quality of instruction in the classroom. Secondly, arranging network opportunities between teachers of Arabic language for exchanging ideas and sharing resources can significantly improve their teaching performances. Third, recognizing the potential needs of students, utilizing successful teaching strategies suitable to the language learning needs of students, and integrating the role of technology in the classroom help improving the overall quality of instruction. Finally, providing feedback to Arabic teachers will help recognizing their strengths and weaknesses and enhancing the quality of instruction.

7. Contributions of the Study

Certain groups and individuals can benefit from the resulting analyses of the data in this study. First, perceptions of the respondents about the councils’ role to support teachers can help the councils to offer the best practices for improving the quality of teaching Arabic in classroom settings. Second, preference of the respondents regarding certain initiatives of developing their professional skills can help school systems in conducting appropriate training programs to improve the quality of teaching Arabic in their school district. Third, the findings of this study can also help other institutions of higher education in conducting studies relevant to the needs assessment of Arabic teachers for improving their professional skills.

8. Suggestions for Future Research

This study was conducted at only one university, and thus results may be different due to localities and certain demographic factors. Other institutions of higher education are, therefore, recommended to conduct similar studies at their own localities. The study was also limited to 50 cases and thus their perceptions should be cautiously generalized. Future studies are, therefore, recommended to include larger sample of teachers in the program; even if it would be necessary to expand the program to more number of conference sessions.

References

- Aldeen Foundation of Arabic Teaching (2013). Startalk Arabic Language Teacher Training Program. Pasadena, CA. http://aldeenfoundation.org/

- American Association of Teachers of Arabic (2014). Arabic Language Programs: Summer Intensive Training Programs. Birmingham, AL. http://www.language-learning.net/

- American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (2013). Annual Convention and World Languages Expo. San Antonio, TX. www.actfl.org/

- August, D., & Shanahan, T. (2006). Developing Literacy in Second-Language Learners: Report of National Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Brigham Young University, Startalk Arabic Language (2010). http://www.byu.edu/

- Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition (2014). Professional Development of Teachers of Arabic. Minneapolis, MN. http://carla.umn.edu/

- Columbia University Summer Arabic Program (2014). http://ce.columbia.edu/summer

- Concordia Language Villages Arabic Teachers’ Workshop (2013). Summer Professional Development Programs. Moorhead, MN. http://www.concordialanguagevillages.org/

- DePaul University (2014).Center for Arabic Language and Culture. Chicago Arabic Language Teachers’ Council. Chicago, IL.

- George Mason University. Summer Session Program (June 23-July 5, 2014). Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area Arabic Teachers’ Council.

- George Washington University Intensive Arabic Program (2014). http://www.gwu.edu/

- Georgetown University Arabic Language Institute (2013). http://www.georgetown.edu/

- Heldt, D. (2010). Arabic Is the Fastest-Growing Language at the United States Colleges. An Article Published in Gazette: Thursday, September 5, 2014.

- Mona, M. (2012). Arabic-Teacher Training and Professional Development. National Foreign Language Center: University of Maryland, Riverdale.

- Morrison, S. (2003). Arabic Language Teaching in the United States. ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics, Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington DC.

- National Middle East Language Resource Center (2013). http://nmelrc.byu.edu

- National Security Language Initiative (2006). Establishment of the Startalk Programs. Announced by Former US President George W. Bush, Washington DC.

- Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (2014). Teacher Professional Development Programs. Took Place in Boston. http://www.nectfl.org/

- Occidental College of Foreign Language Project (2014) Southern California Arabic Language Teachers’ Council. Took Place in Loss Angeles.

- Pennsylvania State University Arabic Language Program (2014). http://www.worldcampus.psu.edu/

- State University of New York Summer Arabic Program (2013). http://www.suny.edu/

- United States Department of Commerce (2012). The Most Common Languages Spoken in the United States. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

- University of California (2014). Arabic Teacher Preparation Summer Session Program: July 18 to July 23, 2014. Santa Barbara. http://universityofcalifornia.edu/.

- University of Maryland Intensive Arabic Language Program (2012). http://www.umd.edu/

- University of Maryland Intensive Arabic Program (2012). National Foreign Language Center. Riverdale. http://www.nflc.org/.

- University of Michigan Summer Arabic Program (2014). http://www.umich.edu/

- University of Minnesota (2014). Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition at the Qatar Foundation International Intensive Arabic Teacher Training. Minneapolis.

- University of Pennsylvania Summer Arabic Program (2013). http://www.upenn.edu/

- University of Wisconsin Summer Arabic Program (2012). http://www.wisc.edu/

- Western Michigan University (2014) Conference for Teachers of Arabic Language. Kalamazoo. http://wmich.edu/