Open Journal of Marine Science

Vol.07 No.03(2017), Article ID:77578,30 pages

10.4236/ojms.2017.73027

Assessing Marine Protected Areas Effectiveness: A Case Study with the Tobago Cays Marine Park

Alba Garcia Rodriguez, Lucia M. Fanning

Marine Affairs Program, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: May 31, 2017; Accepted: July 9, 2017; Published: July 12, 2017

ABSTRACT

Given the socio-economic consequences associated with declaring areas of ocean protected in order to achieve conservation objectives, this paper contributes to the growing global need to assess Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) as an effective management tool. It adds to the current body of knowledge on MPA effectiveness by conducting an evaluation of the Tobago Cays Marine Park (TCMP), located in St. Vincent and the Grenadines (SVG) in the eastern Caribbean, using a modified MPA effectiveness framework. Due to the limited information existing about the current performance of this MPA, this assessment also provides needed insight on the effect that the TCMP is having on the marine ecosystem, as well as its overall management performance. By comparing the performance of the MPA over a 10-year span (2007 and 2016), the results indicate that overall, the TCMP could be described as having limited success when key management categories of context, planning, input, process, output and outcomes are evaluated. In particular, efforts dedicated to planning, process and outcomes are assessed as deficient. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that efforts to realize the stated goals relating to conservation, public awareness and public education were being neglected. However, considerable effort was being expended by TCMP staff on achieving the remaining goal focusing on deriving economic benefits from touristic activities in the Park. Preliminary field research examining the effects of the TCMP on the abundance and density of an economically important species, Lobatus gigas, (commonly referred to as the queen conch) showed the TCMP as having no effect towards conch protection. The results and recommendations of this study, combined with continued monitoring of a recommended targeted suite of indicators, could contribute to better-informed adaptive MPA management, leading to progress towards the achievement of the stated goals for the TCMP.

Keywords:

Marine Protected Areas, MPA Effectiveness, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Tobago Cays Marine Park, Evaluation Framework, Queen Conch

1. Introduction

During the past decades, human activities have severely modified and shaped the marine environment. Fishing practices, fossil fuels consumption, the need for mineral products, and land-based pollution are some of the activities that have been generating important changes in the ocean [1] [2] . The consequences of these activities, particularly when highly developed, often result in negative impacts on the marine biota and the humans who depend on them [3] [4] [5] [6] . These impacts have over time brought attention to the need for better marine management and conservation measures [7] [8] [9] [10] . Effective marine management is the required mechanism to ensure the sustainable use of the ocean’s resources and to develop conservation strategies. Through marine management and conservation, the impacts of climate change, overfishing, pollution, etc. can be mitigated, and ecosystem resilience can be enhanced [11] [12] [13] .

In order to maintain functional and productive marine ecosystems, it is essential to minimize or remove the threats to which these systems are exposed. One response for minimizing these threats is the use of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). MPAs can be defined as clearly outlined geographical spaces that are designated and managed to achieve the conservation of marine ecosystems from a long-term perspective [14] . MPAs have been recognized as one of the best tools for the conservation of marine ecosystems as they are intended to limit anthropogenic activities [15] [16] [17] . However, by establishing an MPA, there is no assurance that it will inherently result in positive impacts on the environment. Currently, many scientists still argue about their actual effectiveness, considering the conservation goals they aim to achieve [18] [19] .

Since MPAs are not physical barriers, the ecosystem existing within their boundaries could still be exposed to pollution, temperature increase, ocean acidification, and other indirect threats. In addition, the size of the MPA could be insufficient to meet its conservation purpose [20] . Furthermore, there could be a lack of compliance and/or enforcement of the MPA regulations, resulting in a legally recognized MPA that is actually not being managed. However, MPAs have been shown in some instances to reduce human threats to marine ecosystems and have been proven to increase biodiversity, biomass, and ecosystem health if they are adequately designated, and well managed [16] [21] . To date, only 2.2% of the world’s oceans are protected [22] and only about 33% of these MPAs might be truly effective, defined as “the degree to which management actions are achieving the goals and objectives of the protected area” [23] .

Currently, no standard method for evaluating effectiveness has been recognized, and thus measurements vary among MPAs. Additionally, given their place-based nature, the effectiveness of MPAs needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case study to determine if management improvements or other conservation measures are being achieved or indeed, even necessary for that particular area [24] . Given the socio-economic consequences associated with declaring areas of ocean protected in order to achieve conservation objectives, this paper contributes to the growing global need to assess MPAs as an effective management tool. The purpose of this study is to develop an adapted MPA evaluation framework to monitor MPA effectiveness and to test the framework using the Tobago Cays Marine Park (TCMP), located in St. Vincent and the Grenadines (SVG) in the eastern Caribbean. Due to the limited information existing about the current performance of the TCMP, this assessment provides needed insight on the effect that this MPA is having on the marine ecosystem, as well as its overall management performance.

This study aims to develop the evaluation framework based on a modification to the scorecard system developed by the World Bank [25] [26] and incorporating MPA performance indicators recommended by Pomeroy et al. [23] . Moreover, in order to evaluate the TCMP as a functioning MPA, this study then assesses its performance regarding the different parts of the management process using the modified evaluation framework as well as compares the results obtained in 2016 with a partially conducted evaluation in 2007. In order to provide more information of the TCMP performance, this desktop assessment is supplemented with field research designed to assess the outcome of the management measures in place at TCMP by examining the effects of this MPA on the abundance of an economically important species, Lobatus gigas, commonly referred to as the queen conch. Finally, this study aims to provide recommendations on additional indicators for improving the monitoring and evaluation of the TCMP to achieve its stated goals, as well as recommendations to improve the management effectiveness of the Park and provide lessons for other MPAs.

2. Study Area

SVG is located in the West Indies (southeastern Caribbean Sea). Comprised of 32 islands, the country has some 390 km2 of land, and 406 km of coastline (Figure 1). As with most Caribbean islands, tourism is an important contributor to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and foreign exchange earnings [27] [28] .

The TCMP, established in 1986, is a 51.8 km2 MPA located in the southern territory of SVG. It was originally proposed to facilitate increasing tourism in the country as the area was identified as the most popular destination for marine tourism in the region [29] [30] . The MPA comprises the east side of Mayreau Island, five uninhabited Cays (Petit Bateau, Petit Rameau, Baradel, Jamesby, and Petit Tabac), and the surrounding marine area [27] [28] [29] (Figure 2). According to the SVG Census Office, in 2012 Mayreau had an estimated population of 271 inhabitants [31] .

The MPA comprises many types of coral reefs, sea grass beds, and patches of endangered mangrove ecosystems. In addition, it is a nursery area for conch, lobster, fish, and green turtles. Furthermore, the Tobago Cays present the largest

Figure 1. Map showing location of St. Vincent and the Grenadines in the south-east Caribbean (Source: AlyDeGraffOllivierre).

Figure 2. Satellite map of the TCMP.

seagrass bed of the country [27] [29] [30] . This area is regulated under the SVG National Parks Authority, and managed by the TCMP as a statutory body. In addition, regulations and laws are implemented by the TCMP [29] .

According to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the TCMP Management Plan of 2007, the goals of TCMP can be summarized as: (1) Enhance conservation and management of biological diversity of the area; (2) Sustain economic benefits from the use of existing natural resources; (3) Increase public awareness of environmental issues and create a strong resources management system; and (4) Contribute to public education to increase engagement and achieve the objectives of the management plan [29] [31] . To date, the effectiveness of the TCMP as an MPA has not been conducted although a partial assessment of the management process was undertaken in 2007 [29] .

3. The Modified MPA Effectiveness Framework

3.1. Adapted Scorecard for Measuring MPA Effectiveness

The scorecard developed by the World Bank in 2004 for assessing MPA effectiveness originally included 34 questions distributed among six categories, namely context, planning, inputs, process, output, and outcome [25] . The scorecard was adapted by supplementing the questions identified for the “process” category with 36 indicators developed by Pomeroy et al. [23] , focusing on the identification and evaluation of the goals of the MPA as well as on communicating the improvements needed in the management of the evaluated MPA (Appendix 1). This modification of the original scorecard was viewed as improving the evaluation of the effectiveness of the MPA by acquiring more monitoring details and to guide the selection of the best indicators to be measured according to the MPA’s goals. To achieve this, questions in the Process category were adapted. Question 19 of the original scorecard was divided into three separate questions to address specific biophysical, socioeconomic, and governance indicators (Question 19, 23 and 25) and the relevant indicators from Pomeroy et al. [23] for each of these were then assigned as illustrated in Questions 20, 24 and 26 (Appendix 1). Lastly, to conduct a more comprehensive evaluation of the monitoring activities undertaken within the MPA, the adapted scorecard was modified to also incorporate questions on the different spatial and temporal scales being measured as recommended by Stelzenmuller and Pinnegar in 2011 [26] , as well as the frequency for monitoring biophysical indicators (Questions 21 and 22, Appendix 1).

To obtain a preliminary assessment of the TCMP using the adapted evaluation framework, responses to the questions were obtained based on a literature review of key TCMP’s management and monitoring documents (e.g. the TCMP management plan, as well as previous assessments and documents describing the area and its management) and in person experience in the area while conducting research on the TCMP [27] [29] [32] [33] [34] . The majority of the indicators were scored on a scale of 0 to 3 (three being scored on a scale of 0 to 2 due to the nature of the questions), with the opportunity for bonus points to be awarded. Effectiveness was calculated based on percent of maximum allowable score obtainable where 0% - 29% was deemed “deficient”, 30% - 49% was “limited”, 50% - 69% was “fair”, 70% - 79% was “good” and more than 80% was considered to be “excellent”.

In addition to the assessment of the TCMP performance in 2016 using the modified scorecard comprised of both the original and supplemental questions, a comparative assessment was undertaken of the results obtained in 2016 using the adapted scorecard with the 2007 assessment using the original scorecard [25] . This comparison allowed for improvements in the effectiveness of the TCMP over a ten-year period to be determined as well as highlighted the additional management information gleaned from a more in-depth monitoring scorecard when assessing MPA effectiveness in 2016.

3.2. Queen Conch Density Surveys to Measure MPA Effectiveness

As noted by scholars and practitioners in the field of MPA management, the ultimate objective of MPAs is to enhance marine conservation. To determine whether this outcome has been achieved by the TCMP, the desktop assessment using the adapted scorecard was supplemented with in situ fieldwork aimed at assessing queen conch abundance and density inside and outside of the Park. Queen conch is a very important resource (environmentally, economically, and culturally) in SVG, as well as in most Caribbean countries. Current management regulations for queen conch in the Grenadines include size limits and protected fishing areas such as the TCMP [35] . However, the TCMP has had many management problems since its creation, and the effect that this MPA might be having in regards to queen conch conservation is not clear. In order to measure the effect of the TCMP on conch abundance to determine its contribution to conch conservation, a stratified random sampling approach was conducted. Underwater surveys were conducted outside (six surveys) and inside the MPA (six surveys). The sites were identified after considering the bathymetry of the area, information on conch distribution provided by the fishing community, and suitable habitats where conch could be found (Figure 3). Each underwater survey consisted on four belt transects of 30 m length and 2 m wide (north, west, south, and east of a deployed buoy on the coordinates of each site), where data on conch abundance was gathered.

The total density of conch in the study area was obtained by calculating the total area surveyed and the amount of conch encountered within that area. The total area sampled in the study area was 5,760 m2 (0.576 hectares), with an equal area surveyed inside and outside the TCMP. Conch density inside the TCMP was obtained using the total area sampled within its boundaries (0.288 hectares). The same procedure was used to obtain conch density in the Union area outside the MPA. Conch density found inside the Park was compared to conch density

Figure 3. Survey sites map. Light blue areas indicate shallow areas (0 - 10 meters), and dark blue areas indicate deeper areas (10 - 20 meters). Survey sites are marked with an orange circle.

found outside, in total and by maturity stage (juveniles and adults). Conch with lip thickness less than 4 mm and shell length less than 20 cm were considered juveniles [36] [37] . Using the statistical software SPSS, Shapiro-Wilk normality tests were used to obtain information on the distribution of the data. Due to the reduced sample size and the distribution pattern of this species, the data did not follow a normal distribution for any of the conducted tests. Therefore, nonparametric analyses were conducted. Specifically, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to conduct pairwise comparisons among groups. The TCMP Rangers provided boat access to the survey sites as well as participated in the surveys.

4. Results

4.1. 2016 TCMP Effectiveness Scores Using the Adapted Scorecard

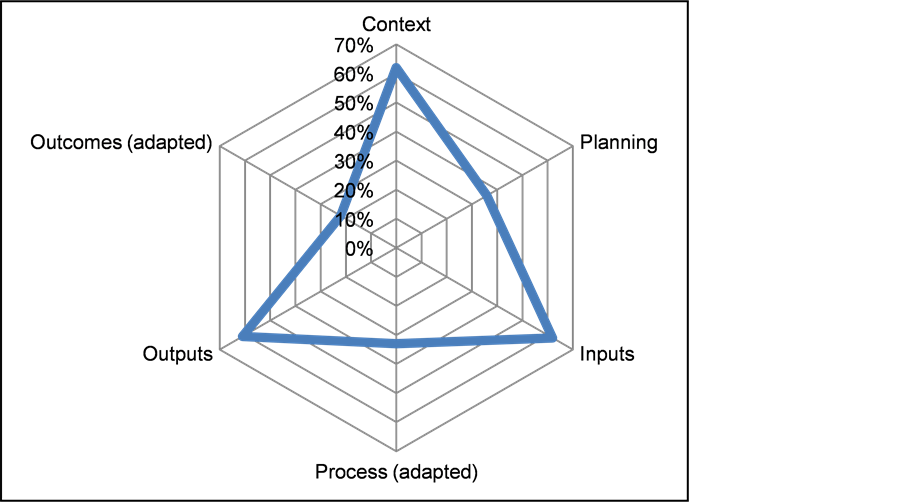

Using available documentation on the TCMP and in person observations, all questions included in the adapted scorecard (Appendix 1) could be adequately addressed except for four of the Outcomes section questions due to lack of reliable, available information. Results showed that the TCMP scored a ranking equating to “fairly” effective in the Context, Inputs, and Outputs categories (61% - 62%) and a ranking of “limited” effectiveness in terms of the Process and Planning categories (33% - 36%). The scoring for the Park for indicators assessing Outcomes indicated its effectiveness for this category could be termed “deficient”, having received a score of only 22%. The overall assessment of TCMP effectiveness could be considered “limited”, based on a score 39% for the six categories included in the adapted scorecard (Table 1).

The urgent need for improvement in the performance of the TCMP, as identified using the modified scorecard is highlighted in Figure 4. While there is room for improvement in the Context, Inputs and Output categories, having all been assigned a ranking of “fair”, attention should be prioritized to address issues associated with Planning and Process which have been assigned a ranking of “deficient”. Given improvements in these categories, one can expect better scores for the expected Outcomes over time.

Table 1. Summary results of TCMP effectiveness in 2016 using the adapted scorecard.

*Qualitative assessment of the rankings equate to 0% - 29% as deficient; 30% - 49% as limited; 50% - 69% as fair; 70% - 79% as good and over 80% as excellent.

Figure 4. TCMP effectiveness by category in 2016 using the adapted scorecard.

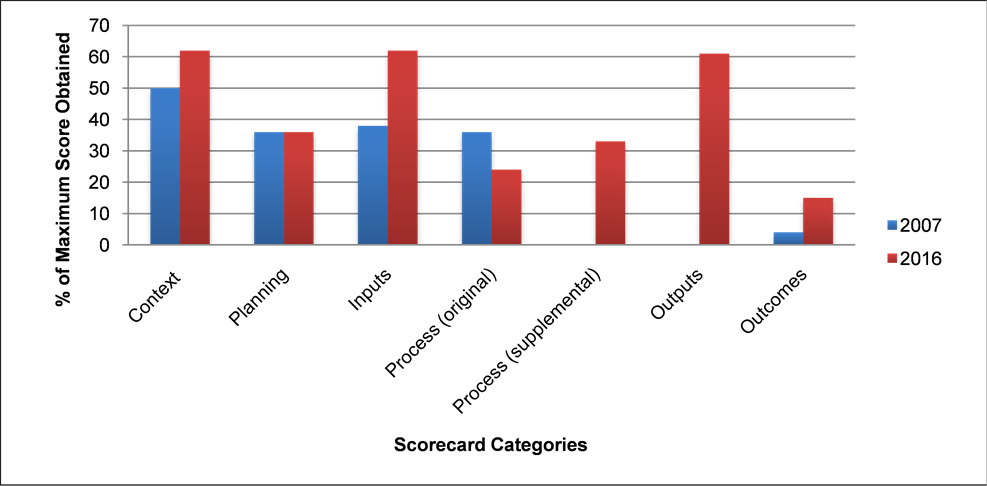

4.2. Evaluating Effectiveness over the Period 2007 to 2016

This analysis examined the results obtained using the original scorecard for 2007 and the adapted scorecard for 2016 where additional questions were added to the Process category. To highlight the difference in the scoring for Process indicators using the different scorecards, the scoring for this category are shown using those questions asked in the original scorecard and the supplemental questions added to create the modified scorecard.

When compared to the results of 2007, the assessment of effectiveness in 2016 relating to Context, Inputs, and Outputs showed considerable improvement (Figure 5). This was attributed to better control of human activities in the Park, the start of the process to include the TCMP into a larger coastal management plan, and the availability of more information to manage the area (Table 2). In addition, it seemed that the staff and budget had slightly improved in 2016 over 2007. However, stakeholder engagement and participation decreased in the ensuing decade. The assessment conducted in 2007 provided no information on measuring indicators addressing Outputs. In contrast, the 2016 Output scores were relatively high due to the improvement in the MPA legal status, management, enforcement, boundary demarcation, resource inventory, existence of moorings, existence of visitor facilities, fees that support the management of the MPA, etc. (Table 2).

Regarding the Planning category, even though there has been an agreement on the goals for the MPA and an increased level of implementation of the management plan since 2007, the scores assigned for both years were the same. For 2016, these higher scores were offset by the decrease in stakeholder participation and the inclusion of socioeconomic issues. However, as shown in Table 3, both assessments obtained similar scores for different reasons.

Figure 5. Scores obtained in 2007 and 2016 regarding TCMP effectiveness using the original scorecard for 2007 and the adapted scorecard for 2016.

Table 2. Summary results of TCMP effectiveness in 2016 using the adapted scorecard.

Table 3. 2007 and 2016 comparison of TCMP Planning scores.

With regard to the assessment of Outcome indicators in 2007, only one sub- question was addressed, specifying that resource conflict had been reduced. The 2016 scores for Outcomes, while higher than that obtained in 2007, scored only a 15% effectiveness ranking. This was due to management objectives and threats had not been fully addressed, overall resource conditions not improving, and lack of current information to score the community welfare, environmental awareness and stakeholder satisfaction with the outcomes of compliance and management of this MPA (Table 4).

Finally, in the Process category, the score for 2016 was lower than in 2007 when using the original scorecard only (Figure 5). This was the result of the apparent lack of communication between managers and stakeholders, and a reduction in stakeholder participation. Using the supplemental questions as a measure of effectiveness in 2016 in the adapted scorecard, the Process section obtained a higher score due to the evaluation of information available for specific monitoring indicators in the modified framework (Table 5).

4.3. Selecting Indicators to Assess Achievement of TCMP’s Goals

Based on the four goals identified for the TCMP and the indicators highlighted in the adapted framework, 20 indicators in total (five for each of the four goals) were identified as important for future assessment of progress towards achieving the goals. Of these indicators, 17 were part of the set proposed by Pomeroy et al.

Table 4. 2007 and 2016 comparison of TCMP Outcome scores.

Table 5. 2007 and 2016 comparison of TCMP Process scores.

(2005) [23] , while three new ones (illegal activities rate; number of visitors; fees collected) were added by the authors in order to gain additional information regarding Goal 2, which focused on economic benefits (Table 6). In addition to their fit with the goals of the TCMP, criteria for selecting the indicators were based on availability of information (pre and post 2015) and feasibility to be monitored.

As noted from the assessment of available information, only six of the indicators have available information and of those, only one has current information, i.e. post 2015. However, it is worth noting that at least one indicator per goal has been tracked, allowing for limited progress on each of the goals to be assessed. The challenge for the TCMP is to obtain monitoring data on at least these six indicators on an ongoing basis and to increase the level of monitoring to more

Table 6. Recommended indicators and availability of information to evaluate progress towards TCMP’s conservation goals.

than the existing six indicators. As such, measuring progress towards Park goals would require a concerted monitoring effort on the part of Park staff and/or their partners. However, given the importance of tracking the achievement of Park goals to determine the effectiveness of the TCMP, a plan to put in place the mechanisms needed should be undertaken and implemented.

4.4. A Preliminary Assessment of TCMP Effect on Conch Abundance and Density

A total of 21 individuals were found during the surveys in 2016, 12 of them (57%) were juveniles, while 9 of them (43%) were adults. Conch density found in the study area was 36.4 individuals/ha in total, 20.8 juveniles/ha, and 15.6 adults/ha. Of the conch found, 16 individuals were encountered inside the TCMP (77%), while only 5 (24%) were encountered outside the TCMP. Interestingly, no adults were found outside the TCMP. Higher densities of conch were found in deeper areas (52.1 ind/ha in total), both for juveniles and adults. In shallow areas, the density was lower (20.8 ind/ha in total), and the proportion of adults and juveniles was equal (Table 7).

Multiple statistical tests were conducted to obtain further information regarding abundance in the study area. Results showed that in 2016 there was no significant difference between the total abundance of conch (Figure 6). Furthermore, the inclusion of the depth as a factor did not show any significant differences in regards to conch abundance in 2016.

Table 7. Abundance and density results for the 12 survey sites, in total and also by maturity level, protection level, and depth.

Figure 6. Mean values of total conch abundance inside and outside the TCMP in 2016. Error bars show 95% confidence interval. Nonparametric statistic analysis (Wilcoxon test) showed no significant difference between these groups. The TCMP bar includes conch abundance inside the MPA, while UNION refers to conch abundance outside the MPA.

5. Discussion

The focus of this paper has been to draw attention to the current status of the TCMP in meeting its stated goals, using a modified assessment framework. The results indicate areas in which the Park is doing an adequate job as well as challenges that need to be addressed. Overall, lack of dependable resources (funding and expertise) as well as lack of appropriate authority have been identified as significant factors limiting effective Park management. However, a key observation that bodes well for the TCMP is the support and interest of external organizations, both within SVG (e.g. SusGren) and more broadly (e.g. TNC, external researchers and the AGGRA Program to name a few). However, maximizing these opportunities to address shortcomings by the TCMP will require greater involvement of Park staff in communicating its specific needs and raising stakeholder awareness and involvement in contributing to meeting its stated goals. The following discussion on the scorecard results, the findings with respect to achievement of Park goals, and the preliminary assessment of the role of the Park in conserving an important economic fishery are offered as a means of informing the development of a targeted collaborative approach to enhance the management of the TCMP.

5.1. Scorecard Results

While the TCMP’s performance increased over the 10-year period between 2007 and 2016, especially with regard to Context, Inputs and Outputs, there is still considerable room for improvement. This is particularly evident in the assessment of Planning, Process, and Outcomes. Furthermore, management practices and outcomes are still deficient when considering all the previously stated goals of the TCMP. In order to increase overall effectiveness, the MPA should be evaluated with relative frequency (ideally every two to three years) to improve opportunities for adaptive management and address issues in need of greater attention. The modified framework for assessing performance provides a suite of indicators from which the TCMP, in collaboration with interested partners could enhance the overall understanding of the progress being made (or not) within each of the six management categories, with particular emphasis on improving process related activities.

To enhance outcomes addressing the goals of public engagement, awareness and education, after each monitoring and evaluation cycle, a series of meetings should be held to discuss the findings with all relevant stakeholders and to consider how current management activities should be modified. This should be a joint effort undertaken with Park staff, even if facilitated by an external organization. It has been noted that before performance monitoring and evaluation can be well-integrated within the regular management practices, MPAs often need “major institutional reorientation at the policy level” [38] . Perhaps, by developing incentives, and engaging the community to expect performance information of the TCMP, managers could start conducting performance reports, allowing for a higher connection between the community and the management of this MPA again, as was the case in 2007.

5.2. TCMP Performance in Achieving Stated Goals

The TCMP has four main goals, of which it seems that only the second one (sustain economic benefits from the use of existing natural resources) is being achieved. The other three goals relate to marine conservation, public awareness and resources management, and public education and engagement.

Goal 1: Enhance conservation and management of biological diversity of the area.

Regarding the first goal, monitoring of several biophysical indicators has been conducted with relative frequency, mostly by external organizations or during ad hoc external research. However, the purpose behind these efforts seemed to have had no specific connection with improving TCMP management actions. There is an apparent disconnect between management and monitoring in the TCMP, limiting any opportunity for the implementation of adaptive management. This could be from the lack of a requirement by external researchers to provide the TCMP managers with their research proposal or their findings after completing their research. Furthermore, when research relevant to the TCMP is completed, it may not be published or the TCMP managers may not be aware that it has been published or have access to the publication, even if the data could be of use. In addition, the TCMP does not generally conduct research as part of its own activities.

Goal 2: Sustain economic benefits from the use of existing natural resources.

Emphasis on achieving Goal 2 has been the main focus of TCMP staff. According to observations in the area, most of the TCMP resources, staff, and budget are used to collect fees from boats visiting the TCMP, and to maintain the moorings. These economic benefits are the major source of funding of the MPA and staff salaries, and no doubt account for the attention given to this goal. Given the array of different expertise that would be needed to monitor progress towards the other stated goals, it would seem likely that a higher budget and additional staff will be needed if all of the goals become the focus of the Park management. Alternately, the re-structuring of current resources and workplans could be explored as well as developing more collaborative and formal linkages with external organizations that explicitly specify how their activities could contribute towards enhanced management of the Park.

Goal 3 and Goal 4: Increase public awareness of environmental issues and create a strong resources management system; and contribute to public education to increase engagement and achieve the objectives of the management plan.

The focus on these goals was very evident during the draft of the management plan. However, after the plan was drafted and finally accepted, activities relating to its achievement appeared to have been dropped. During the drafting of the management plan, it was noted that management of the TCMP “should be people-centered and participatory”. It was also stated that two particularly relevant aspects were public education and monitoring [33] . However, the priority documents that were generated in 2007 mostly targeted visitors instead of the local community. Other expected outputs such as educational materials for school children were similarly not given priority. Finally and as noted above, research plans involving the TCMP (including surveys and analyses) are not developed or implemented by the TCMP and as such, do not play a key role in increasing public awareness and education about the resource management system for the TCMP.

The measures identified in the management plan aimed to increase the effectiveness of the management of the Park. However, it seems that they were not, or only partially, implemented. In 2002, Day, Hockings, & Jones stated that “while monitoring and evaluation programs are supported in principle, they often get displaced by more ‘urgent’ (though often less important) day-to-day management activities” [39] . We suggest that this displacement could also happen at the level of goals. In the case of the TCMP, it seems monitoring activities and performance evaluations for three of the four goals identified for the Park were displaced by the need to maintain an adequate mooring systems so as to obtain economic benefits from tourism inside the MPA. Perhaps, if external funding (not originating from the fees collected inside the MPA) was secured on an annual basis, a higher focus on achieving the remaining goals would be developed. Until then, it is possible that major efforts at TCMP will be directed towards Goal 2.

5.3. TCMP Effectiveness Based on Conch Density

Results obtained on density and abundance of queen conch showed no significant difference inside and outside of the Park, even though conch had a higher density inside the TCMP borders than in nonprotected areas around Union Island. However, it is important to note that overall conch abundance has been reported as decreasing in the area as a result of overfishing, according to local knowledge [29] . As such, the TCMP could potentially have cushioned that decrease, contributing to the conservation of this species although not from a statistically significant perspective.

It is well known that excessive fishing pressure is usually responsible for conch decrease in multiple Caribbean countries [38] . However, the TCMP is a no-take MPA, and as such, it should be reasonable to discount conch fishing as a reason underlying the apparent lack of influence of the TCMP on the conservation of this species within the Park boundaries. Nevertheless, it is also known in the community and by the TCMP Rangers that some illegal fishing activities are still occurring inside the TCMP, so fishing activities could partially explain the results obtained. On the other hand, water quality could also be having major impacts on the abundance of this species. Conch are very sensitive to water quality changes due to their specific habitat requirements [40] . It is important to remember that the TCMP was originally created with tourism increase purposes. However, few measures to manage tourism activities were taken at the time, and the management plan does not include regulations for tourism except for the designation of special zones for anchoring [30] . According to a recent study by Reed, about 50,000 visitors and about 8,600 yachts entered the TCMP in 2015 [41] . It is known that vessels visiting the MPA could be decreasing water quality levels due to sewage waste generated by these vessels, and therefore regulations such as holding tank release restrictions have been recommended. Given the decrease in water quality caused by some twenty years of non-managed tourism activities, it is conceivable that this could be an important cause for the lack of effect of the TCMP regarding queen conch conservation.

Currently, the TCMP is in the process of implementing a yacht management plan to reduce the impacts that anchoring has inside the MPA, including tourism-oriented management measures for the first time [41] . This plan calls for enhanced water quality monitoring, as well as data collection on yacht impacts. It is also likely that this information will contribute to a better understanding of the carrying capacity inside the MPA for tourism. In addition, by analyzing water quality data and yacht abundance, poor water quality or degraded areas could be identified [41] .

In order to ensure the health of the marine ecosystem and that adequate management is being implemented, it is essential to continue monitoring marine life, as well as other indicators such as water quality. We contend that the adapted framework can serve as an improved guide for ensuring all six management categories and four outcomes are tracked using indicators that provide needed data for informed decision making and adaptive management. However, recognizing the limited resources, dependence on external expertise and funding that limits implementation of a planned monitoring program, at a minimum, a focus on indicators tracking TCMP goals (Table 6) should be explicitly guiding monitoring decisions undertaken by Park staff or in discussions with external organizations. If monitoring continues and the necessary measures to preserve this area are taken (e.g. the successful implementation of a yacht management plan), the TCMP could significantly contribute to the conservation of multiple marine species such as conch, corals, and others as well as enhance the economic benefits to be obtained from a well-managed marine ecosystem.

The adapted framework developed in this study can certainly be used to evaluate other MPAs in order to test their effectiveness as management measures. The use of the adapted framework should be followed by the identification of a set of indicators that could be measured in the MPA to track its progress over time. These indicators might be different from the ones presented in this study, as they should fit the MPA goals, challenges, and management capacity. Considering that only 33% of the worlds MPAs could be truly effective, the need to evaluate them in a comprehensive manner is clear. In order to achieve the desired outcomes from the implementation of MPAs, these assessments should be conducted, so their performance can be improved.

6. Conclusions

MPAs have been found to be effective tools for marine conservation when they are adequately designated and managed. Management challenges encountered at the TCMP need to be overcome for it to achieve its full potential. For this purpose, the evaluation of the TCMP’s effectiveness needs to be carried out with relative frequency to be able to determine the management actions that need improvement to reach the desired goals. In addition, it would be critical that the TCMP does not lose the perspective on the goals that they were originally trying to achieve. Currently, the TCMP needs to improve their planning, process, and outcomes in terms of their management actions, as well as to improve their monitoring strategies, and their ability to incorporate research data into their management actions. In addition, the TCMP needs to develop a higher focus on education, stakeholder participation, and stakeholder engagement.

It is essential to develop the necessary tools and platforms to promote integrated planning and implementation, collaboration, and information sharing between managers, external researchers and the TCMP staff, and between the community and the TCMP staff. In addition, it is important to develop strategies in which an annual budget for the management of the TCMP can be secured, and it is important that this is not only linked to tourism visitation. Tourism threats should be further identified and included as part of the management plan in order to reduce them. The carrying capacity of this MPA should also be determined in order to promote the sustainable use of the TCMP. Furthermore, the enforcement capacity of the TCMP should improve, as currently its staff does not have the authority to fine infractions occurring in the area, such as anchoring in restricted areas. Finally, the enforcement capacity of the TCMP should cover all regulations and monitoring of activities that are necessary to focus on the achievement of their goals.

Meeting current management, conservation, and socioeconomic needs of the MPA, investing in research activities, using available data to improve management, and conducting performance evaluations are the only way in which the TCMP will be able to become a successful and fully operational MPA at a time when effective marine management and protection are urgently required. Finally, the results of the evaluation conducted in this study can provide insights and lessons for other MPAs and managers. The authors encourage the use of the adapted scorecard as well as the identification of recommended indicators to evaluate other MPAs in order to enhance the overall performance of MPAs around the globe, and to encourage the adequate conservation of our marine resources.

Acknowledgements

Part of this study was conducted under the Eastern Caribbean Marine Managed Areas Network (ECMMAN) Project, in collaboration with the Tobago Cays Marine Park, the National Parks and Beaches Authority of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Sustainable Grenadines Inc. The authors would like to thank Sustainable Grenadines Inc., the TCMP staff and the community of Union Island for their support during this research.

Cite this paper

Garcia Rodriguez, A. and Fanning, L.M. (2017) Assessing Marine Protected Areas Effectiveness: A Case Study with the Tobago Cays Marine Park. Open Journal of Marine Science, 7, 379-408. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojms.2017.73027

References

- 1. Halpern, B.S., Walbridge, S., Selkoe, K.A., Kappel, C.V., Micheli, F., D’agrosa, C., Bruno, J.F., Casey, K.S., Ebert, C., Fox, H.E. and Fujita, R. (2008) A Global Map of Human Impact on Marine Ecosystems. Science, 319, 948-952. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1149345

- 2. Halpern, B.S., Longo, C., Hardy, D., McLeod, K.L., Samhouri, J.F., Katona, S.K., Kleisner, K., Lester, S.E., O’Leary, J., Ranelletti, M. and Rosenberg, A.A. (2012) An Index to Assess the Health and Benefits of the Global Ocean. Nature, 488, 615-620. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11397

- 3. Vitousek, P.M., Mooney, H.A., Lubchenco, J. and Melillo, J.M. (1997) Human Domination of Earth’s Ecosystems. Science, 277, 494-499. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5325.494

- 4. Crutzen, P.J. (2006) The “Anthropocene”. In Earth System Science in the Anthropocene. Springer, Berlin, 13-18.https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-26590-2_3

- 5. Wu, Z., Yu, Z., Song, X., Li, Y., Cao, X. and Yuan, Y. (2016) A Methodology for Assessing and Mapping Pressure of Human Activities on Coastal Region Based on Stepwise Logic Decision Process and GIS Technology. Ocean & Coastal Management, 120, 80-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.11.016

- 6. Madin, E.M., Dill, L.M., Ridlon, A.D., Heithaus, M.R. and Warner, R.R. (2016) Human Activities Change Marine Ecosystems by Altering Predation Risk. Global Change Biology, 22, 44-60. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13083

- 7. Borja, A., Elliott, M., Carstensen, J., Heiskanen, A.S. and Van, B.W. (2010) Marine Management-Towards an Integrated Implementation of the European Marine Strategy Framework and the Water Framework Directives. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 60, 2175-2186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.09.026

- 8. Douvere, F. (2008) The Importance of Marine Spatial Planning in Advancing Ecosystem-Based Sea Use Management. Marine Policy, 32, 762-771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2008.03.021

- 9. Wondolleck, J.M. and Yaffee, S.L. (2017) Drawing Lessons from Experience in Marine Ecosystem-Based Management. In: Wondolleck, J. and Yaffee, S., Eds., Marine Ecosystem-Based Management in Practice, Island Press, Center for Resource Economics, Washington DC, 1-12.https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-61091-800-8_1

- 10. Gunderson, A.R., Armstrong, E.J. and Stillman, J.H. (2016) Multiple Stressors in a Changing World: the Need for an Improved Perspective on Physiological Responses to the Dynamic Marine Environment. Annual Review of Marine Science, 8, 357-378.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-122414-033953

- 11. Micheli, F., Saenz-Arroyo, A., Greenley, A., Vazquez, L., Espinoza, M.J.A., Rossetto, M. and Leo, G.A. (2012) Evidence that Marine Reserves Enhance Resilience to Climatic Impacts. PLoS One, 7, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040832

- 12. Barner, A.K., Lubchenco, J., Costello, C., Gaines, S.D., Leland, A., Jenks, B., Murawski, S., Schwaab, E. and Spring, M. (2015) Solutions for Recovering and Sustaining the Bounty of the Ocean: Combining Fishery Reforms, Rights-Based Fisheries Management, and Marine Reserves. Oceanography, 28, 252-263. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2015.51

- 13. Hoegh-Guldberg, O. and Bruno, J.F. (2010) The Impact of Climate Change on the World’s Marine Ecosystems. Science, 328, 1523-1528. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1189930

- 14. Dudley, N. (2008) Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories. International Union for Conservation of Nature, Gland VD.

- 15. Agardy, M.T. (1994) Advances in Marine Conservation: The Role of Marine Protected Areas. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 9, 267-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(94)90297-6

- 16. Halpern, B.S. and Warner, R.R. (2002) Marine Reserves Have Rapid and Lasting Effects. Ecology Letters, 5, 361-366. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2002.00326.x

- 17. Hughes, T.P., Baird, A.H., Bellwood, D.R., Card, M., Connolly, S.R., Folke, C. and Roughgarden, J. (2003) Climate Change, Human Impacts, and the Resilience of Coral Reefs. Science, 301, 929-933. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1085046

- 18. Boersma, P.D. and Parrish, J.K. (1999) Limiting Abuse: Marine Protected Areas, a Limited Solution. Ecological Economics, 31, 287-304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00085-3

- 19. Jameson, S.C., Tupper, M.H. and Ridley, J.M. (2002) The Three Screen Doors: Can Marine “Protected” Areas Be Effective? Marine Pollution Bulletin, 44, 1177-1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00258-8

- 20. Agardy, T., Sciara, G.N. and Christie, P. (2011) Mind the Gap: Addressing the Shortcomings of Marine Protected Areas through Large Scale Marine Spatial Planning. Marine Policy, 35, 226-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.10.006

- 21. Claudet, J., Pelletier, D., Jouvenel, J.Y., Bachet, F. and Galzin, R. (2006) Assessing the Effects of Marine Protected Area (MPA) on a Reef Fish Assemblage in a Northwestern Mediterranean Marine Reserve: Identifying Community-Based Indicators. Biological Conservation, 130, 349-369.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.12.030

- 22. MPAtlas (2016) Discover the World’s Marine Protected Areas. Marine Conservation Institute, Seattle.

- 23. Pomeroy, R.S., Watson, L.M., Parks, J.E. and Cid, G.A. (2005) How Is Your MPA Doing? A Methodology for Evaluating the Management Effectiveness of Marine Protected Areas. Ocean & Coastal Management, 48, 485-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2005.05.004

- 24. Selig, E.R. and Bruno, J.F. (2010) A Global Analysis of the Effectiveness of Marine Protected Areas in Preventing Coral Loss. PLoS One, 5, Article ID: e9278. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009278

- 25. Staub, F. and Hatziolos, M.E. (2004) Score Card to Assess Progress in Achieving Management Effectiveness Goals for Marine Protected Areas. World Bank, Washington DC.

- 26. Stelzenmuller, V. and Pinnegar, J.K. (2011) Monitoring Fisheries Effects of Marine Protected Areas: Current Approaches and the Need for Integrated Assessments. In Marine Protected Areas: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Cambridge University Press, New York, 186-189.https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139049382.011

- 27. The Nature Conservancy (2016) St. Vincent and the Grenadines’ Coral Reef Report Card 2016. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, 8.https://www.nature.org/media/coral-reef-report-cards/SVG_Report_Card_2016_WebLowRes.pdf

- 28. World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) (2017) Travel and Tourism Economic Impact Caribbean. World Travel and Tourism Council, London.https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/regions-2017/caribbean2017.pdf

- 29. Hoggarth, D. (2007) Tobago Cays Marine Park 2007-2009 Management Plan. Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States, and Environment and Sustainable Development Unit, St. Lucia.

- 30. United Nations Environment Programme (2014) Proposed Areas for Inclusion in the SPAW List. Annotated Format for Presentation Report for: Tobago Cays Marine Park, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. United Nations Environment Programme, Kingston.

- 31. The Census Office (2012) 2012 Population & Housing Census: Preliminary Report. St. Vincent & the Grenadines Population & Housing. Central Planning Division, Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, Suitland.

- 32. Deschamps, A., Desrochers, A. and Klomp, K.D. (2003) A Rapid Assessment of the Horseshoe Reef, Tobago Cays Marine Park, St. Vincent, West Indies (Stony Corals, Algae and Fishes). Atoll Research Bulletin, 496, 438-458. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00775630.496-24.438

- 33. Ecoengineering Caribbean Limited (2007) Environmental and Socio-Economic Studies for OPAAL Demonstration Sites. Tobago Cays Site Report, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. (Eco Report No. 06). Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States Environment and Sustainable Development Unit, St. Augustine, Trinidad, West Indies.

- 34. Phillips, M. and Hewitt, K. (2015) Eastern Caribbean Marine Managed Areas Network (ECMANN) Project. Component 3: Prioritizing Sites in the SVG MMA System for Application of Key Management Actions. Sustainable Grenadines Incorporation, St. Vincent, 11.

- 35. Food and Agriculture Organization (2007) Regional Workshop on the Monitoring and Management of Queen Conch, Strombus gigas (FAO Fisheries Report No. 832) Food and Agriculture Organization, Kingston, 186.

- 36. Egan, B.D. (1985) Aspects of the Reproductive Biology of Strombus Gigas. University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

- 37. Clark, S.A., Danylchuk, A.J. and Freeman, B.T. (2005) The Harvest of Juvenile Queen Conch (Strombus gigas) off Cape Eleuthera, Bahamas: Implications for the Effectiveness of a Marine Reserve. Proceedings of the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute, 56, 705-714.

- 38. Townsend, J. (2012) Petition to List Queen Conch (Strombas gigas) under the Endangered Species Act. WildEarth Guardians, Santa Fe.

- 39. Day, J., Hockings, M. and Jones, G. (2002) Measuring Effectiveness in Marine Protected Areas: Principles and Practice. World Congress on Aquatic Protected Areas, 18, 401-404.

- 40. Appeldoorn, R.S., Gonzalez, E.C., Glazer, R. and Prada, M. (2011) Applying EBM to Queen Conch Fisheries in the Caribbean. In: Fanning, L., Mahon, R. and Mcconney, P., Eds., Towards Marine Ecosystem-Based Management in the Wider Caribbean, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 177-186.

- 41. Reed, M. (2016) Adaptive Moorings Management Plan for Tobago Cays Marine Park, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Sustainable Grenadines Incorporation and The Nature Conservancy for Tobago Cays Marine Park with Funding from United States Agency for International Development, Arlington.

Appendix 1

Criteria for scoring MPA effectiveness

Submit or recommend next manuscript to SCIRP and we will provide best service for you:

Accepting pre-submission inquiries through Email, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, etc.

A wide selection of journals (inclusive of 9 subjects, more than 200 journals)

Providing 24-hour high-quality service

User-friendly online submission system

Fair and swift peer-review system

Efficient typesetting and proofreading procedure

Display of the result of downloads and visits, as well as the number of cited articles

Maximum dissemination of your research work

Submit your manuscript at: http://papersubmission.scirp.org/

Or contact ojms@scirp.org