Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.3(2013), Article ID:34953,7 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.33044

Interprofessional education development: A road map for getting there

![]()

Faculty of Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Nursing, Lubbock, USA

Email: *yondell.masten@ttuhsc.edu

Copyright © 2013 Yondell Masten et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 18 April 2013; revised 19 May 2013; accepted 10 June 2013

Keywords: Interprofessional Education

ABSTRACT

Improvement of relationships among health clinicians is important for reducing adverse clinical outcomes. To improve clinician relationships, the relationship development process is best initiated during health professional education, rather than “refitting” the interrelationship model learned during the health education process. While Interprofessional Education (IPE) has been identified as an effective model to fill the gap for both education and practice, IPE requires moving to an integrative curricular approach with a strong practice component. As a developmental process, IPE implementation faces challenges at every stage. The Interprofessional Education Development: The Roadmap for Getting There article describes the five stages of IPE, discusses important components of creating an IPE culture, suggests strategies for overcoming the challenges for each stage, and describes signs related to achievement of the five developmental stages of IPE.

1. INTRODUCTION

Substantial preventable mortality, morbidity, and major quality issues have been linked to inadequacies in systems of care delivery because of the widespread nature of patient adverse events in U.S. hospitals. Identified deficiencies in collaboration and communication among healthcare professionals have consistently been found to negatively impact the provision of healthcare and patient outcomes for decades [1,2]. Improvement of relationships among clinicians has been recognized to be the most influential factor in reducing potentially negative effects on clinical outcomes. Reduction of negative effects will not occur, however, without reforming education across the health professions. IPE, defined as the process of preparing health professionals and students to deliberatively work together in building a safer, patientcentered, and community/population oriented U.S. health care system, has been identified as one effective model for both education and practice [3]. Thus, the purpose of the Interprofessional Education Development: The Roadmap for Getting There article is to describe the five stages of IPE occurring within a mid-western health sciences center university and to discuss important aspects of creating an IPE culture.

To move IPE forward, faculty and administrators must understand what IPE is (and is not), as well as how to move from merely adding IPE content to a few courses or creating a couple of electives with an IPE focus to a comprehensive, integrative, curricular approach considered as the “norm” for the university [4]. Struggling with how to get to full acceptance and integration of IPE into curricula and practice learning opportunities is not unique because major institutional and practice obstacles exist for implementation. The goal for discussing the roadmap to IPE culture development is to assist faculty and administrators in filling the gap between the current health professions education and implementing the recommended IPE across the health professions by realizing IPE is a progressive process rather than an “all or nothing” process.

2. HISTORY OF IPE DEVELOPMENT

The IPE movement became active in the mid-1990s. Many of the pioneers were foundations, such as the Hartford Foundation, Robert Woods Johnson Foundation, and Josiah Macy Foundation. Each foundation identified the need for professional collaboration. Additionally, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) presented alarming rates of multiple quality problems facing the nation. The IOM laid out visions of how systems must change in practice, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Heath System [5], Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century [6], and in education, Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality (2003) [1].

By 2005, professional organizations solidified the IOM vision of focusing on interprofessional collaborative practice as the primary means to address international quality problems. Significant among the practices were the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) and American Interprofessional Health Collaborative (AIHC). Both organizations teamed together to form the Collaborating across Boarders (CAB) entity to accelerate the already rising IPE movement.

Between 2005 and 2012, accrediting agencies and professional organizations redefined competencies of individual health care professional education curricula. Professional organizations, in particular the World Health Organization (WHO) and Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC), created sentinel reports defining IPE and identifying core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice. Today the reports serve as foundational documents for all health professions chartering a course of IPE.

Currently, IPE is recognized as an effective approach to teaching and learning with the goal of facilitating effective collaboration to result in a competent, collaborative practice-ready heath care workforce. Such a workforce is capable of achieving health outcomes of the highest quality and is prepared to engage individuals whose skills can help achieve local health goals. The defining characteristic of IPE is when individuals (students) from two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other [7].

At the present time and from an international viewpoint, Canada is leading the way in interprofessional education by creating collaborative standards among the health professions. For example, Canada provides the only certification course for interprofessional education. The certification course, coordinated by the Centre for Interprofessional Education at the University of Toronto, is designed for health professionals interested in interprofessional education and interprofessional practice [8]. The aims of the continuing education-based certification course are to develop leaders in interprofessional education with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to teach both learners and fellow colleagues the art and science of working collaboratively for patient-centered care. Other progressive innovations developed in Canada include the Accreditation of Interprofessional Health Education (AIPHE) Standards Development Working Group, funded by Health Canada in 2010. The Working Group is charged with development of an Interprofessional Health Education Accreditation Standards Guide (www.aiphe.ca) [9]. The guide is intended to provide suggestions for accreditation agencies to consider when developing, implementing, and evaluating interprofessional health education standards for accreditation purposes.

The United States has begun building resources to support IPE. In 2012, the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services awarded the University of Minnesota $4 million over five years to establish a national coordinating center for IPE and collaborative practice, the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education. Additionally, the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and John A. Hartford Foundation have collectively committed up to $8.6 million in grants over five years to support and guide the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education. The Center will work to accelerate team work and collaboration among doctors, nurses, other health professionals, and patients to break down the traditional silo-approach to health professions education. Further, the IOM Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education recently released Interprofessional Education for Collaboration: Learning How to Improve Health from Interprofessional Models across the Continuum of Education to Practice. The Workshop Summary clearly communicates the definition and evidence for understanding IPE, based on living histories of speakers from around the world, including Canada, India, South Africa, and Uganda. Experiences working in and between IPE and interprofessional or collaborative practice were shared with the attendees [10].

3. MOTIVATING FACTORS FOR IMPLEMENTING IPE DEVELOPMENT

IPE is moving forward via the motivation promoted by health professionals and organizations, policy makers, and patients. Many are painfully aware of the shortcomings of the nation’s current system and are demanding change. The overarching motivational factor is the significant role IPE can play in mitigating many of the challenges faced by health systems around the world. IPE has the potential to strengthen health systems, and ultimately, achieve improved health outcomes. IPE professions can change the way health professionals interact with one another to deliver care designed to ease the global health workforce crisis; improve workplace practices and productivity; increase staff morale; improve patient outcomes; increase patient satisfaction; and improve patient safety. Participating students learn in real world experiences, gain insights, engage in program development, and develop an understanding of the work of other health professionals. Engaged faculty members have opportunity to be innovative and can be rejuvenated with new methods of communication and facilitation of learning resulting in increased research and other schoolarly activities.

Health professionals unwilling to participate in IPE, will soon find very few practice and academic settings not implementing IPE. Governing and accrediting agencies, health professions, patients and families are demanding improved health outcomes available through interprofessional practice. The major consequence of not engaging in IPE is being left behind. At the present time, interprofessional education and practice seem to be strategies for improving health care outcomes, even though the journey will be difficult.

Health science and technology advancements are coming at unprecedented rates, and will continue to so. Under current health care system conditions, patients are too frequently harmed and benefits of the system are not routinely delivered to patients. Further, patients are living longer. Additionally, the consequence of an aging population is an increase in the incidence and prevalence of chronic conditions. Care delivery models are complex and uncoordinated, often resulting in decreased quality and safety [6]. Thus, IPE provides the opportunity to fill gaps in the current health care system. The purpose of IPE is to create, through education, a skilled health professions work force serving as members of high functioning teams. Each member deliberately works with other team members to resolve problems and provide timely, safe, high quality care. Thus, IPE is really about interprofessionality, a concept embodying both interprofessional education and interprofessional collaborative practice. Interprofessionality is defined as “the process by which professionals reflect on and develop ways of practicing that provides an integrated and cohesive answer to the needs of the client/family/population… [and] involves continuous interaction and knowledge sharing between professionals organized to solve or explore a variety of education and care issues all while seeking to optimize the patient’s participation… Interprofessionailty requires a paradigm shift, since interprofessional practice has unique characteristics in terms of values, codes of conduct, and ways of working” [11].

The relative lack of systematic and normative standards for planning, development, implementation and evaluation of IPE academic programs can be considered another motivational factor in the maturation of IPE as a movement. The increasing pressures for building the evidence base for any innovation includes establishing standards and benchmarks. Building the state of the art and science for IPE is an evolutionary process requiring academic and health system engagement in enterprise activities.

4. FIVE STAGES OF IPE DEVELOPMENT

Based on the review of the literature, the IOM recommendations, and motivating factors for IPE, faculty at a large health sciences university began the process of developing IPE. Reflecting on the process, the following steps of progressing from the beginning to cultural change were recognized:

Stage 1. Awakening. Awakening is defined as the process of emerging awareness regarding a difference between interdisciplinary and interprofessional educational and practice activities.

Stage 2. Giving Lip Service. Giving lip service is defined as the process of professional struggling to place current interdisciplinary activities into the interprofessional framework.

Stage 3. Parallel Play. Parallel play, a concept borrowed from pediatric colleagues, is defined as the process of progressing from total absorption in individual health profession activities to awareness of similar activities by other health professionals at the same time, much as toddlers playing in the sand box at the same time where each toddler is engrossed in individual rather than group play. Professionals may comment on similarities of health profession activities, may imitate the health profession activities of other health professionals, but rarely engage in cooperative or collaborative activities.

Stage 4. Group Play. Group play, another concept borrowed from pediatric colleagues, is defined as cooperative group engagement in similar health profession activities with other health professionals where learning occurs with and from each other.

Stage 5. Cultural Transformation. Cultural transformation, is defined as planned cooperation, coordination, and collaboration by teams of health professionals to improve patient care [7,12].

5. SUGGESTIONS FOR IPE DEVELOPMENT

The process of interprofessional education and practice development is progressive, presents challenges (opportunities for review, revision, and refinement), and requires periodic self-assessment and realignment of the processes to achieve and maintain Stage 5 IPE Cultural Transformation. Suggestions for progressing along the journey are as follows:

Stage 1. Awakening. The process for IPE development begins with the faculty and educational/practice administrators realizing the usual pedagogies for health professions education do not effectively promote achievement of the expected interprofessional outcomes, e.g., functioning as a member of a collaborative practice team and moving health systems from a pattern of fragmented care delivery to a strengthened model designed to achieve improved health outcomes. The “signs” of interprofessional development awakening for educational and practice faculty and administrators include such evidence as conversations about the shift in educational professsional accreditation agency focus from current pedagogies to interprofessional learning pedagogies. Experiences of awakening for faculty at a large health sciences university and educational administrators began in the School of Nursing (SON) with review of the publications, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Heath System [5] and Crossing the Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century [6].

The SON adopted as student learning outcomes for the BSN and MSN graduates the IOM [1] recommendations for health professions competencies listed below:

• Provide patient-centered care;

• Work as an effective member of interprofessional teams;

• Employ evidence-based practice (EBP);

• Apply quality improvement measures;

• Utilize informatics;

• Provide safe care.

Adopting the IOM recommended competencies stimulated rich conversations among faculty in the SON and with faculty from other schools in the health sciences center. Suggestions for progressing through the Awakening stage for administrators and faculty are as follows:

• Negotiation with the CEO to present the notion of IPE to the institutional leadership council first (rather than trying to get buy-in of the institutional leadership members by SON faculty conversations with other health-related departmental faculty and leaders);

• Institutional CEO-initiated conversations for changing health-related professions education preparation of graduates to meet the IOM recommendations for student learning outcomes;

• Alignment of curricula with accrediting agency criteria.

For example, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACS-COC) requires each college and university in the eleven southern states of the SACS-COC region to develop a university (or college) Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP). At a health sciences university, the QEP started out as Interprofessional Teamwork (IT). The initial response was “the QEP is forced upon us and we will do only what is required.” Then, the School of Pharmacy (SOP) hosted a professional accreditation site visit. SOP faculty and administration, as well as the entire health sciences university, thought the SOP was implementing IT but the onsite accreditation team did not see evidence of IT implementation. The on-site team report stimulated a more focused conversations about IT.

Stage 2. Giving “Lip Service”. Giving “lip service” to the notion of IPE development as being “okay” includes such signs as agreeing “IPE development is a good idea as long as my faculty, my department, or I do not have to change how our courses are taught; agreeing to participate in some IPE development activities as long as doing so does not take too much time or require making changes in the curriculum; and accepting IPE development with neutral enthusiasm as long as the implementation does not interfere with how we do business.” Experiences of giving “lip service” at a large health sciences university included allowing one faculty champion per school to be named as a school representative to the IPE development task force with no reduction in workload assignments. Suggestions for progressing through the giving “lip service” stage require costs listed as follows:

• Faculty release time for conversations, working in task force groups to develop modules and courses, and to revise the curricula;

• Faculty incentives, e.g., credit toward tenure and promotion;

• “Counting” IPE development as part of faculty workload;

• Preventing burn-out of Faculty Champions.

Stage 3. Parallel Play. The parallel play stage of IPE implementation development includes collaboratively designed educational and practice activities for implementation on individual school/college, department, or course bases. Parallel Play signs include individual department or school/college IPE activities but no “crosspollination” of activities with other departments/schools/ colleges in the institution. Another Parallel Play sign is a tendency for a department or school/college to avoid “airing dirty laundry” with anyone outside the department or school/college until everything has been “cleaned up” and activities can be shared as exemplars. Examples of parallel play at a health sciences university include development of within the school interprofessional activities by two schools, development of off-campus and after-hours activities by one school, review and revision of the curriculum in another school, and multiple attempts by one to engage other HSC schools in common IPE curricular work. Suggestions for progressing through the Parallel Play stage are as follows:

• Provide support for faculty risk-takers willing to step up;

• Achieve complete buy-in by the institutional leadership;

• Provide an edict by the institution CEO stating the curricula will be revised to support IPE.

Stage 4. Group Play. The group play stage of IPE development is demonstrated by such process improvement signs as broadening practice-based case studies developed by designated faculty experts to enrich case study simulation learning for all health professions students. An example of the focus for a broad-based case study is a common health care client presentation applicable across all health sciences university schools such as a common women’s health problem case study. In addition to the focus on the client’s problem, ethical issues can be inserted for rich discussion. Examples of group play at a health sciences university include reaching out to other schools for team-based simulation learning, standardized patient learning experiences, and asking faculty from other schools to collaborate on research grant applications and manuscript development. Suggestions for progressing through the Group Play stage include the following:

• University and school administrative recognition of and appreciation for the struggles faculty face all along the journey;

• Provision of faculty development across departments/ schools/colleges for common topics, e.g., prescriptive authority;

• Sharing new IPE pedagogies by faculty champion representatives with faculty of individual schools (example one faculty champion shared the work and pedagogical changes discussed by the Faculty Champion Task Force with faculty in a “neutral” school so the faculty were able to adopt IPE pedagogies within the school and move to Step 4, Group Play);

• Providing seed grants for research projects and/or curriculum revision projects;

• Scheduling classes and school holidays for common semester/quarter time frames to support IPE activities by engaged students.

Stage 5. Cultural Transformation. Cultural Transformation achievement results in extremely clear, valued, and rewarding IPE implementation. Once achieved, the interprofessional processes seem easy, obvious, and implementers have difficulty understanding the initial confusion and resistance. Signs of Cultural Transformation achievement include the following:

• System changes in support of IPE implementation;

• Practice planning, development, and implementation of role expectations;

• True IPE and practice faculty-to-faculty interactions with measurable productivity;

• Revised curricula development to include common courses across all health-related professions schools and/or common modules embedded within similar courses;

• Implementation of IPE clinical learning and practice experiences.

Examples at a health sciences university include the system changes to make IP teamwork easier to implement, e.g., development of a Center for Rural Health and work toward development of the IPE Institute. Suggestions for maintaining Cultural Transformation include the following:

• Support IP research teams;

• Revise Promotion and Tenure criteria to include interprofessional development activities;

• Open the doors to each education and practice silo.

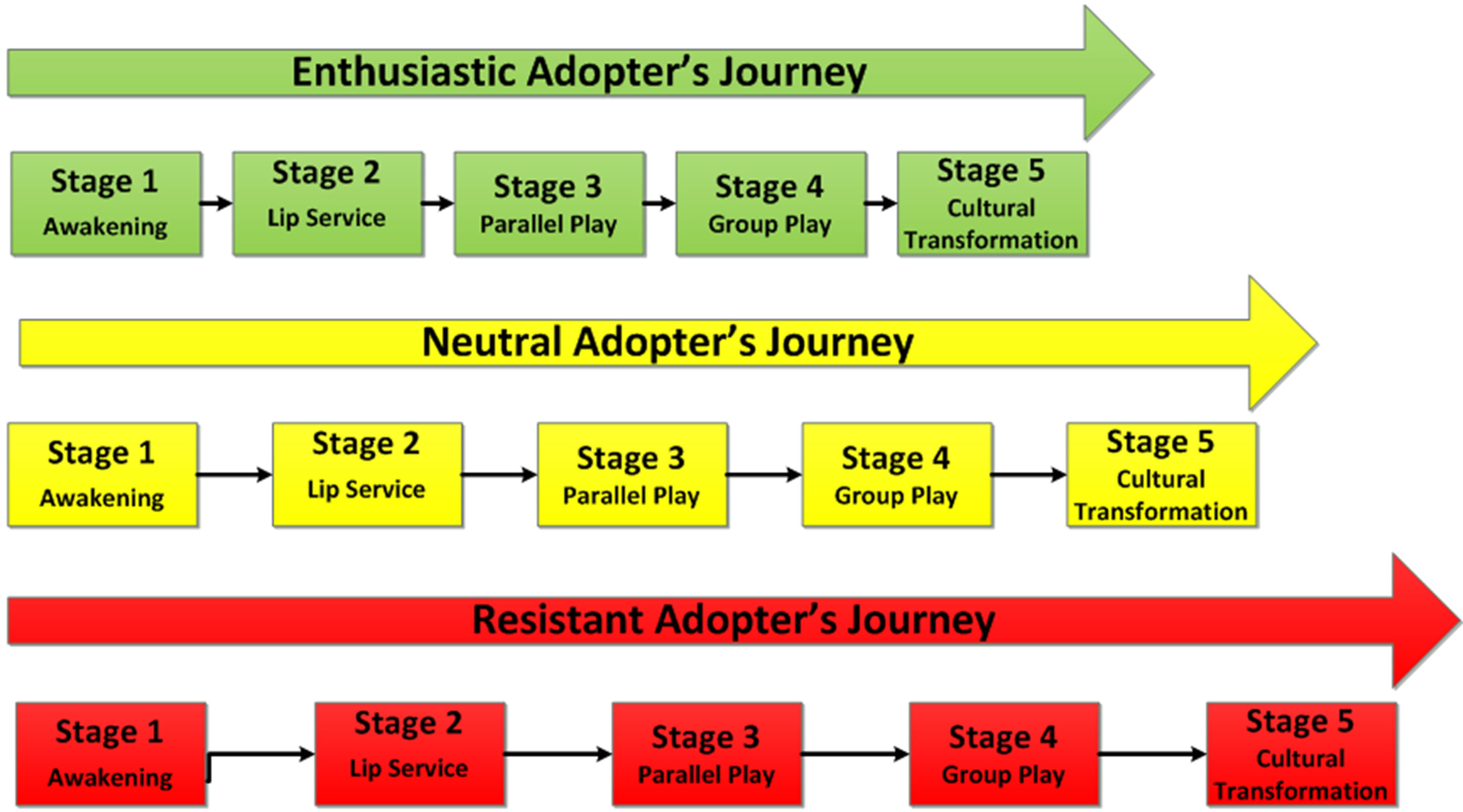

As faculty within schools and schools within a health sciences institution progressed through the five stages of IPE development and maintenance, three types of IPE adopters (enthusiastic, neutral, resistant) and time frames emerged. Enthusiastic adopter faculty/schools grasp the “vision” of IPE quickly and move through the stages toward cultural change in a persistent, timely manner. Neutral adopter faculty/schools “wait and see” whether the revisions for IPE really are required/necessary and to let other faculty/schools “work out the bugs” first. Resistant adopter faculty/schools focus on avoiding revisions as long as possible and delaying progression as much as possible. Figure 1, Map of Stage Progression Journey for Enthusiastic, Neutral, and Resistant Adopters, depicts the more rapid progression of enthusiastic adopter, “wait and see” progression of neutral adopters, and slower progression of the resistant adopter faculty and administrators, through the five stages from awakening to cultural change. The variation in progression is typical of the various faculty in each of the health professions schools/colleges and institutions. See Figure 1, Map of Stage Progression Journey for Enthusiastic, Neutral, and Resistant Adopters.

6. SUMMARY/CONCLUSION

The endeavor to establish and develop an IPE curriculum in academic institutions is fraught with challenges and obstacles, depending on the nature and environment within the academic institution as a system and on individual components within the system. In a health sciences center, for example, where the academic components consist of individual health professions schools where the majority offer graduate level programs only, chances are the individual health professions schools are steeped in traditional modes of knowledge building and dissemination. The strongest tendencies dominating such traditional mode educational cultures are to follow in the lines of established tradition and pedagogy. Thus, the critical component in the beginning journey toward creating an IPE curriculum is to seriously face the challenges, demands, and obstacles.

One of the first steps is to obtain the support of executive top level administration. Achieving top level administrative support was not an easy task for the health sciences university experience. Within a ten-year period, four presidents came and went. Each president came with little knowledge and vision relative to IPE, and for three

Figure 1. Map of stage progression journey for enthusiastic, neutral, and resistant adopters key. Green color: stage progression for early adoption by enthusiastic adopters of IPE. Yellow color: stage progression for “wait and see” adoption by neutral adopters of IPE. Red color: stage progression for late adoption by resistant adopters of IPE.

of the four presidents, the learning curves were steep. A typical beginning attitude towards the concept of IPE was bare acknowledgement of the need or usefulness of IPE, or lip service support with lukewarm administrative involvement. A major commitment is required on the part of IPE faculty champions within such a system for the time, effort, and fortitude required to persist in guiding top administration through the trajectory from bare acknowledgement to full and active administrative involvement in IPE cultural change. An important part of such involvement is committing the financial support necessary to build a lasting infrastructure for IPE. In the health sciences university experience, the threat of not being able to meet continuing regional (SACS-COC) accreditation standards was needed to propel the executive administration to commit significant resources to building the infrastructure.

A major requirement to establishing a meaningful IPE curriculum is the nurturance of institutional collaboration among the various schools within the health sciences institution. Inter-academic disciplinary variations in both knowledge and commitment to IPE are a common characteristic found in many institutions attempting to establish IPE curricula. Oftentimes, Nursing is found to be the “lone voice” in the interprofessional education wilderness. As a frequently holistic discipline, Nursing tends to have a differing world view from other health professsions. The nursing world view imbues the task of establishing partnerships and collaborations for IPE among the other health professions disciplines where more segmented views of the world are particularly challenging. Yet, Nursing is in a crucial position to promote and encourage IPE because the model requires interprofessional collaborations to set up a holistic process [13].

Another challenge in IPE is the creation of a cadre of institutional faculty champions from various schools within the system. Acquiring or developing such a cadre is not an easy task and requires a significant amount of systematic institutional resources. The required IPE cadre-development resources include identifying committed individuals, providing each one with adequate support, distributing responsibilities among the cadre and ensuring meaningful incentives to guarantee continued commitment and ongoing participation as leaders in the initiative. Another vital component to the IPE of health care professions students is availability of practicum sites where interprofessional collaborative practice can be fostered. Generational dissonance is a real possibility where younger generations of students have been educated through IPE curricula and are exposed to clinical sites where older generations of practicing professionals have never been introduced to the concept of IP practice. Thus, the possibility of creating confusion and disappointment among the students is an essential situation to be anticipated.

In many academic settings where the movement towards IPE is just beginning, there is an evolutionary challenge in development of faculty capacity for IPE. At the very beginning of the journey at a health sciences university, a core group of faculty leaders must be identified, committed, and trained to marshal the process all the way to maturity. Such issues as faculty development, workload allocation, release time, and meaningful incentives must be faced and resolved. The most essential strategic challenge for planning and structural development is building administrative support for the appropriate infrastructure before implementing IPE can even be attempted.

One of the major challenges in implementing IPE pedagogy is the evaluation of the process outcomes. The educational literature provides substantial guidance in structuring the process of evaluation and measurement of educational outcomes for academic programs. While serving as a basis for the evaluation of IPE, there are significant questions to be answered, if the outcomes of the IPE program are to be truly measured. Major questions for the designers and implementers of IPE include the following:

• How to determine the metrics to measure the ecological validity of the program;

• How to account for and accommodate the natural environment where the student learns.

To a large extent, the practice environment where the students in IPE are exposed for learning experiences must be a representative design of true practice settings for delivery of health care services in the IP model of practice.

REFERENCES

- Institute of Medicine (2003) Health professions education: A bridge to quality. The National Academies Press, Washington DC.

- Finkelman, A.W. and Kenner, C. (2009) Teaching IOM: Implications of the Institute of Medicine reports for nursing education.

- Buring, S.M., Bhushan, A., Broeseker, A., Conway, S., Duncan-Hewitt, W., Hansen, L. and Westberg, S. (2009) Interprofessional education: Definitions, student competencies, and guidelines for implementation. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 73, 59. doi:10.5688/aj730459

- Blue, A.V., Mitcham, M., Smith, T., Raymond, J. and Greenberg, R. (2010) Changing the future of health professions: Embedding interprofessional education within an academic health center. Academic Medicine, 85, 1290- 1295

- Institute of Medicine (2000) To err is human: Building a safer health system. The National Academies Press, Washington DC.

- Institute of Medicine (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. The National Academies Press, Washington DC.

- Organization, World Health (1988) Learning together to work together for health. Report of a WHO study group on multiprofessional education of health personnel: The team approach. WHO Technical Report Series, 769, 3-72.

- University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine (2013) Continuing education and professional development website—Better education, better outcomes. http://www.cepd.utoronto.ca

- Accreditation of Interprofessional Health Education, [AIPHE] (2011) Interprofessional Health Education Accreditation Standards Guide. http://www.cihc.ca/aiphe/about

- Institute of Medicine (2013) Interprofessional education for collaboration: Learning how to improve health from interprofessional models across the continuum of education to practice: Workshop summary. The National Academies Press, Washington DC.

- D’amour, D. and Oandasan, I. (2005) Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: An emerging concept. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19, 8-20. doi:10.1080/13561820500081604

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel (2011) Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel.

- Gilbert, J.H. (2005) Interprofessional education for collaborative, patient-centred practice, Nursing Leadership (Toronto Ontario), 18, 32-36.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.