Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Vol.3 No.9A(2013), Article ID:38989,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ojog.2013.39A004

Giving voice to adolescent mothers’ challenges*

![]()

1Casey Health Institute, Gaithersburg, USA

2Northwestern University, Chicago, USA

3Washington University, St. Louis, USA

Email: #askowron@caseyhealth.org

Copyright © 2013 Amanda Skowron et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 2 August 2013; revised 1 September 2013; accepted 10 September 2013

Keywords: Postpartum Care; Adolescents; Pregnancy/Parenting

ABSTRACT

An estimated 32% to 60% of adolescent mothers experience postpartum depression. Young women who deal with the simultaneous developmental tasks of adolescence and parenting are vulnerable to depression, which affects the welfare of both the mother and child. The primary objective of this qualitative study was to appreciate the unique experiences of adolescent mothers. Seventeen postpartum adolescents participated in two focus groups and completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The qualitative data analysis identified 19 major conceptual themes in the data. The four most frequently discussed themes that emerged were: 1) social support, 2) differences between teen and adult mothers, 3) parenting ability, and 4) increased maturity. Six of the 17 participants (35.3%) had CES-D scores of 16 or above, which is indicative of a probable major depression. These findings highlight areas that could inform screening assessments, treatment, and prevention programs for adolescent mothers.

1. INTRODUCTION

Young women under 18 years of age who deal with parenting an infant in addition to the developmental tasks of adolescence are often poorly prepared, have few resources, and are stressed [1]. The availability of positively perceived social support has been identified as essential for maternal role functioning and confidence [2]. When postpartum women receive social support that matches their needs, they have fewer symptoms of depression [3,4]. Most pregnant and parenting young women are unmarried and unemployed. They must rely on their families for basic necessities, such as food and housing, for both themselves and their infants. Guardians frequently provide childcare so adolescent mothers can continue their education. This situation reinforces the young woman’s dependent role while she is simultaneously seeking independence from her nuclear family.

The involvement of family members and the baby’s father has a direct impact on the adolescent mother’s perceived support. Flaherty [5] studied the involvement of African-American grandmothers in the care activities of their grandchildren. Grandmothers had a prominent role in both caring for the infant and in helping their daughters develop their skills, such as managing schedules, activities and resources related to infant care. Grandmothers also supervised their daughter’s lifestyle and personal goals. Support from the father of the baby was mentioned frequently as being important to young pregnant and parenting women, and, when present, increased her self-esteem [6]. However, young fathers have limited resources, so they are rarely sources of financial support. They might also lack the maturity to provide their partners with emotional support and stability [1].

Young motherhood brings many hardships. Adolescent mothers are at risk for emotional and behavioral problems, including depression and parenting difficulties. Approximately 14.5% of women experience depression in the first 3 months after childbirth [7], and higher rates have been reported among adolescents. The prevalence of depression in adolescents during the early postpartum period varies from 32% to 60% [8-10]. One study found that more than 50% of adolescent mothers reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms during the first year postpartum [11].

To understand the experience of depression for young postpartum women, Clemmens [12] conducted a phenomenological study. Feeling depressed as a young mother included several unique experiences: feeling changed, different, and frightened by with the sudden realization of motherhood; torn between the responsibilities of adolescence and motherhood; feeling abandoned and rejected by partners and peers; questioning and not understanding what was happening to them.

Postpartum depression has lasting effects on children’s cognitive and emotional growth and affects maternal role functioning [13,14]. Problems observed in children of mothers with postpartum depression include insecure attachment [15]; antisocial behavior (temper tantrums, less sharing, less sociability with strangers, uncontrollable behavior) [16]; and poorer cognitive performance at age 4 [17-19]. Maternal role functioning in young women (n = 66) has been compared to adults (n = 242) [20]. Young women scored lower on care-taking behaviors than adults and experienced less gratification in the maternal role at 8 and 12 months postpartum. Young women also reported diminishing social support over time. During the first year postpartum, Mercer [20] found that women aged 15 - 19 years experienced more feelings of responsibility and “loss of freedom” as compared to adults.

Nunes and Phipps [21] reported that adolescent postpartum depressive symptoms were influenced by different risk factors than adult postpartum depressive symptoms and current screening tools might not adequately identify high risk adolescents. We conducted a focus group study of adolescent mothers to better appreciate the experiences of young motherhood.

2. METHODS

Two focus groups for adolescent mothers were conducted in an urban city in the United States of America on 7/20/10 and 10/19/10. Approval was obtained from the University’s Institutional Review Board. Postpartum adolescents were broadly recruited from the adolescent maternity unit at the university’s obstetrical hospital by posting flyers. Inclusion criteria were: age less than 18 years, gave birth to a live infant in the year prior, and adolescent assent with parental consent for participation. Each participant received $50 for participating, as well as lunch during the focus group discussion.

The two focus groups were scheduled from 4 - 6 PM, in a conference room at a perinatal mental health research program. The first group had 8 participants and the second had 9 participants. Chairs were arranged in a circle. If a family member was not available, infant care facilities were provided to allow the adolescent mothers to participate freely in the focus groups, while certified staff members cared for the infants.

At the beginning of the session, the mothers were asked to provide demographic information, and because of the high prevalence of postpartum depression amongst adolescents, participants completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D [22]) to assess depressive symptoms. The CES-D has been used extensively in groups of young postpartum women and has high sensitivity and specificity in adolescents including ethnic minorities [23]. The CES-D is a 20-item instrument with a score of 16 or higher indicating probable major depression diagnostic status [24].

The focus groups were facilitated by a doctoral level epidemiologist who had conducted similar focus groups with adults [25]. She explained that the purpose of the meeting was to understand teenage mothers’ experiences in the year following childbirth. The mothers used first names only and were assured that their personal information would not be connected to the data collected. The adolescents were encouraged to speak openly about their views without worrying about disagreeing with others. The discussion was audio-taped and later transcribed for analysis by the data team in the University Center for Social and Urban Studies.

Discussions were framed by research questions chosen to progress from introductory comments to more demanding questions. Mothers were asked to discuss: 1) the responsibilities associated with new motherhood; 2) changes in their lives since giving birth; 3) the characteristics of “a good mom”; 4) the circumstances surrounding times when the mothers feel confident and distressed; and, 5) sources of support and tension in their lives.

A thematic analysis [26,27] was used to develop a list of codes that identified the major conceptual categories in the data. Initially two coders read through the two focus group transcripts and independently identified the major themes. The code lists were then consolidated into a single codebook by the project manager, which was approved by the investigative team. The two coders applied these codes to the two focus transcripts with Atlas.ti 6.2, a qualitative data analysis software program that enables multi-coder projects. Disagreements in applications of the codes were then adjudicated jointly by the investigative team, project manager, and coders utilizing the software package Eusebius, an adjudication application program. Based on the results of the adjudication, the project manager removed invalid code applications from the Atlas.ti data files, and consolidated the two sets of codings into a single set of code applications for both focus group transcripts. To understand the themes discussed in the focus groups, Atlas.ti 6.2 was used to generate lists of quotations for each individual code in the codebook, and a code frequency matrix for each transcript.

3. RESULTS

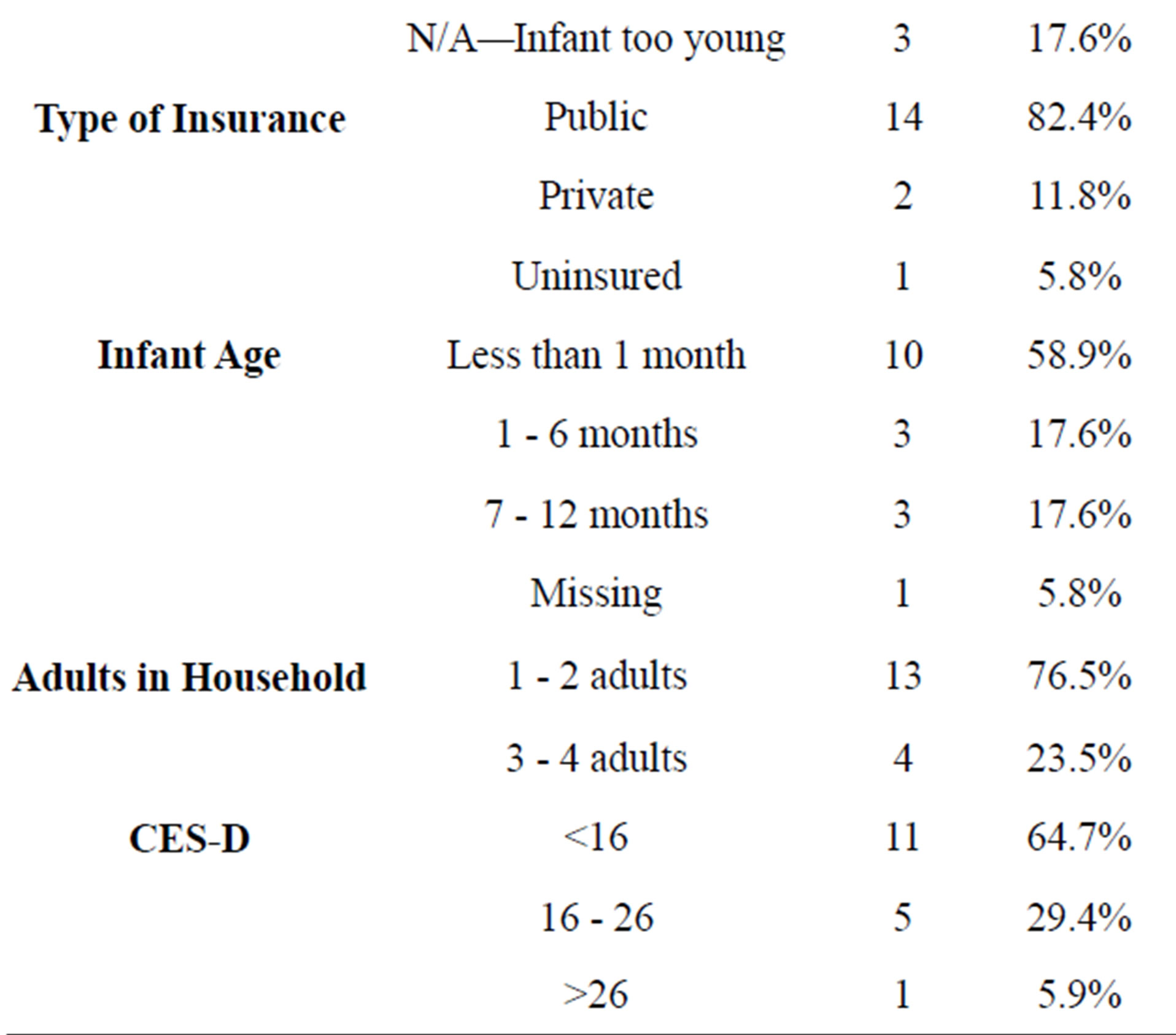

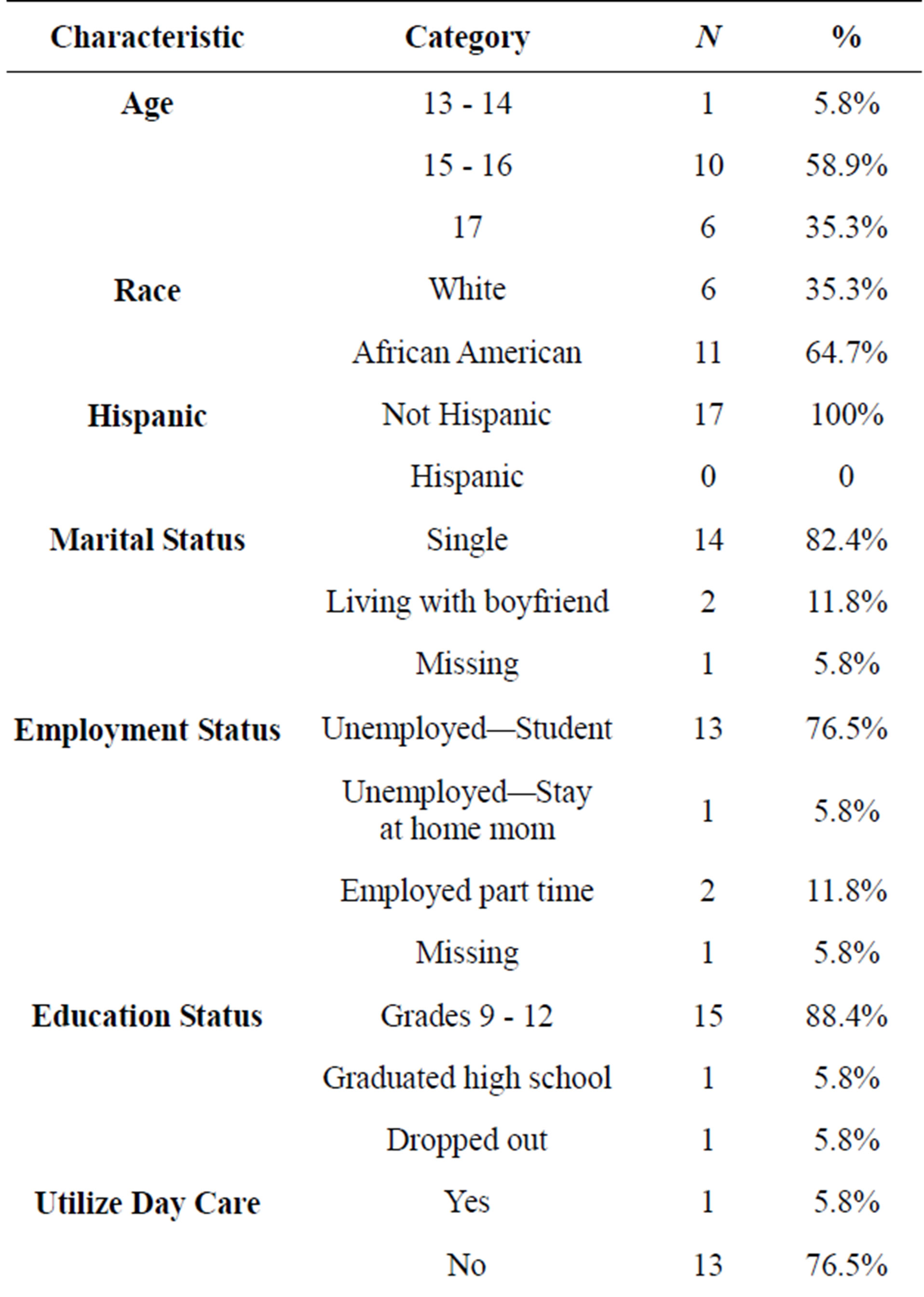

Participants included 17 postpartum adolescents. Eleven African American and 6 White adolescents participated in the study and 58.9% of the sample was 15 - 16 years old. The majority of adolescents were single (82.4%) and students (76.5%). The scores for the CES-D indicated that 35.3% of the mothers scored above 16, consistent with probable depression (Table 1).

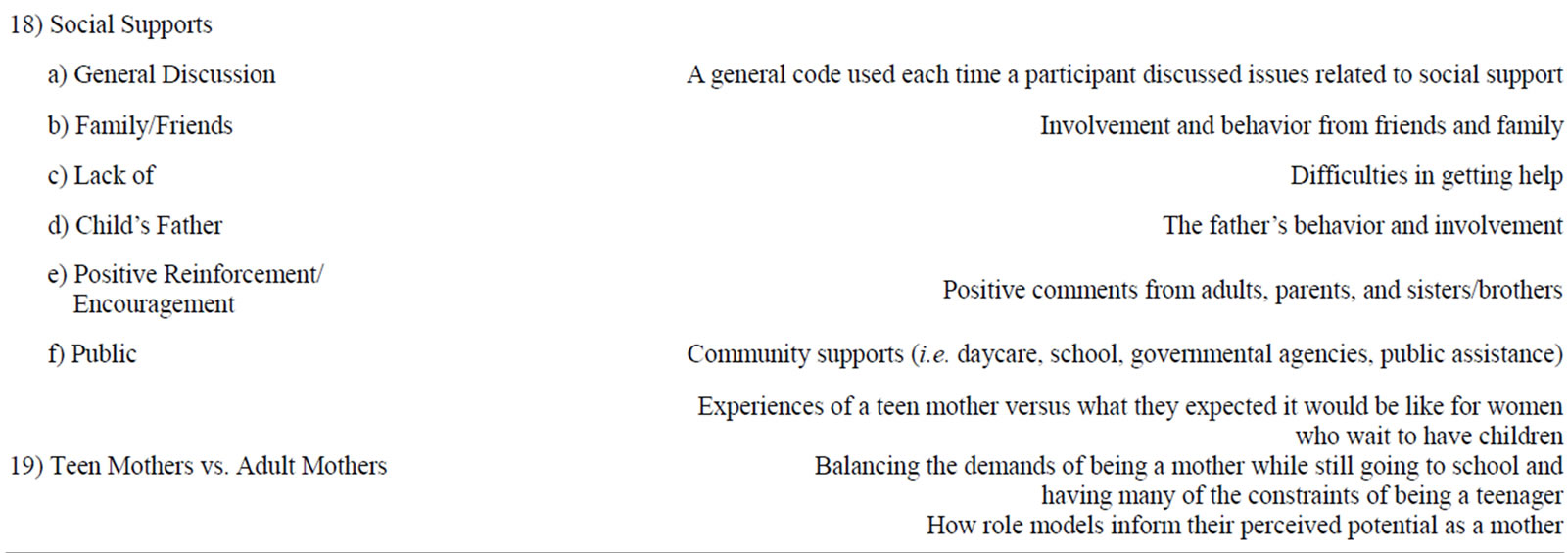

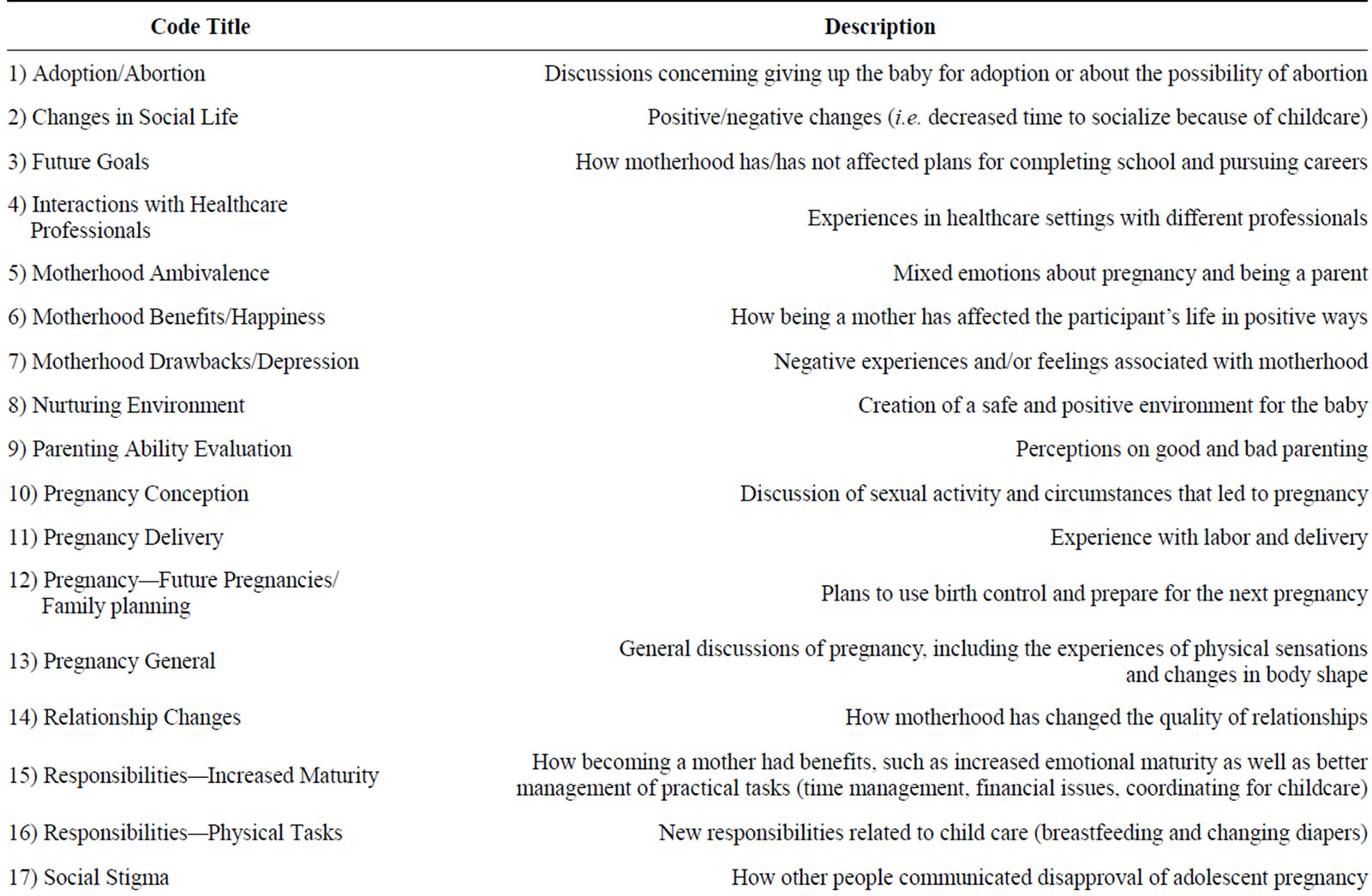

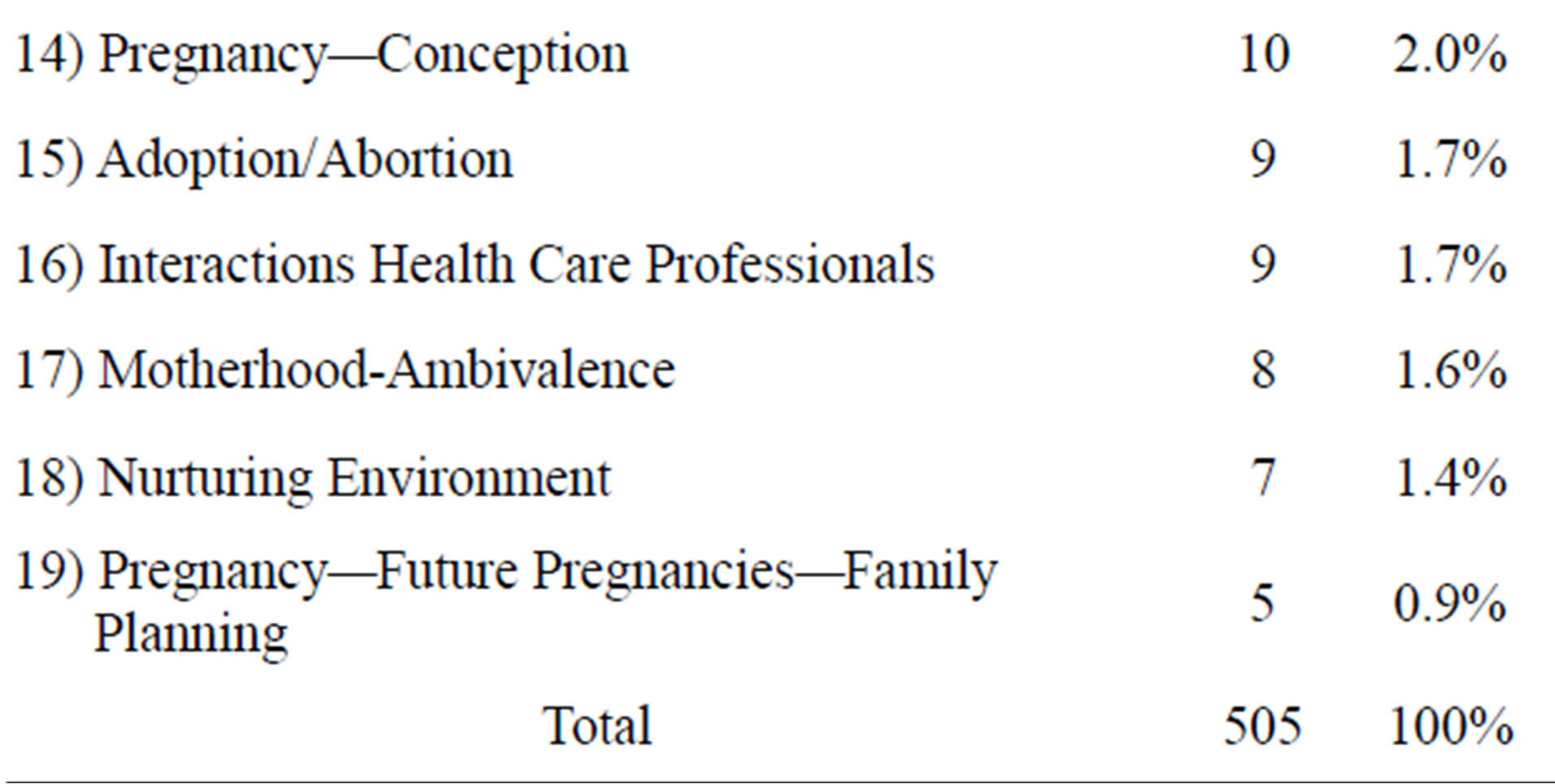

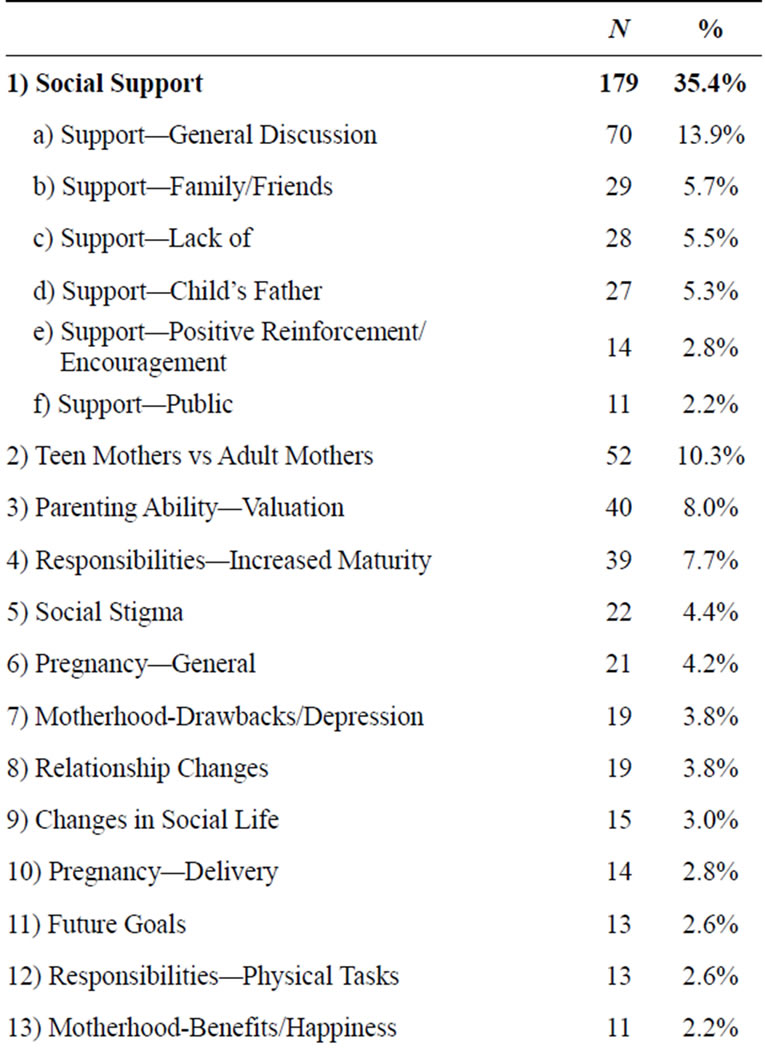

Nineteen themes were identified (Table 2). The four most frequently identified themes were (Table 3): 1) social support, 2) differences between teen and adult mothers, 3) parenting ability and valuation, and 4) responsibilities—increased maturity. Social Support was by far the most frequently discussed topic (35.4%). To better understand how social support was discussed in the focus groups, the “Social Support” code was subdivided into 6 categories: 1) general discussion indicated nonspecific mention of social support (13.9%); 2) statements about support from family/friends (5.7%), 3) lack of support from people in their lives (5.5%); 4) levels of involvement from the child’s father (5.3%), 5) reinforcement/encouragement, which indicated positive experiences of social support (2.8%); 6) support from public sources, such as school, public assistance, and daycare (2.2%). Adolescent mothers voiced varying opinions about how they perceived different support systems. The high frequency of the social support codes highlights its importance to young women and the many different ways that social support was part of the conversation.

The social support offered by family/friends was described through the verbal acknowledgments and behavior of others:

She says that she’s so proud of me and she thinks I’m doing so well and that she could never do that, and that she’s glad that I kept him and stuff like that. She’s, she’s real supportive. So is my friend [name]. She, they both love him to death. Like, they always want to come over and play with him.

“My mom usually watches my baby, when I need some time. My sister helps too.”

“Yeah, my mom and my sister, they help me out a lot. Yeah, my dad does, too.”

One adolescent mother’s statement about support from family/friends highlighted perceived inconsistency in support from pregnancy and early after delivery to months postpartum. “My one friend, [name], and she’s 16, but, and she had her baby when she was 15 and whatever. And, it’s like, she stopped going to school like a month after she had her baby because like she had no-like when she was pregnant, everybody like, her boyfriend’s mom was like, “Keep the baby, like, this is my first grandchild, we’ll be there, we’ll watch him” and then after a minute like, after like her first month of school nobody like-she really didn’t have no one to watch.”

Support or lack thereof by the child’s father and his family was described by several of the adolescent mothers.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

My sister’s boyfriend sees my daughter more than his dad does. And I was like, you’re going—I called her dad, and I was like, you’re going to be mad because she’s going to call somebody else dad. I was like, she’s not going to know who you are.

My son’s dad, his family, they’re real supportive, like they love my son, they’re real they’re real involved in his life—I’m proud of that.

Table 2. Code definitions.

Statements coded as reinforcement/encouragement often related to guidance and role models:

Cause when I came home with my baby and he kept crying. I just was not patient. I kept crying too. [laughter] And, but, it was just hard work. My mom-I just, I just wanted my mom to like, just have him, like, I didn’t want to hold him or none of that. Because it was the middle of the night, he kept waking up and just, just kept crying, and it was like crazy. My mom’s like, “Yeah, be patient with him. He’s a newborn.” She’s like, “It will get better,” and all that good stuff. And I just, just kept crying. And then, three weeks or whatever, and I started getting patient with him and I felt much better cause then my mom started giving me more compliments, so, it worked out. So now I’m patient with him, I don’t cry no more.

The second most frequently discussed theme was Teen Mothers versus Adult Mothers (10.3%). This code was used when adolescent mothers made comparisons between their experiences as a teen mother versus what they expected it would be like for older women who have children. This code included: 1) balancing the de-

Table 3. Code frequencies for the 19 themes.

mands of being a mother, going to school, and the constraints of being a teenager, 2) discussions about the need and usefulness of role models and other examples of motherhood, and 3) discussion of a history of teen pregnancy in the participant’s family. The participants’ statements highlighted conflicting messages that they received and the difficult balance of being a teenager and a mother.

Yeah, because sometimes, sometimes my mom will say, “Well you had a baby, you’re old now, da, da, da,” and sometimes she’ll be, “Oh well you’re only 17 so da, da, da, da, it’s like with me like, I-I’m mature, but I’m still the same person that I was before I had my baby. Like I’m still goofy, funny, the only thing··· [I will] be more mature within the decisions that I make and stuff like that.”

The decision about adoption was one area where a participant described a situation of feeling more like a teenager and being “told what to do”:

“At first, when I first found out, I just wanted to give him up, and then my mom, she wouldn’t let me do that because she was adopted and, so. And his dad was adopted, too, so he was like, I would have taken him before you would have done that, so. I was kind of forced into keeping him, but, after I’d had him I was glad that I did keep him.”

Within this theme, participants also discussed the need to have role models and examples of how to parent from different people in their lives (i.e. mothers, siblings):

“I just watch my sister, she has a little daughter, and my other sister, she has a three year old son, I watch what they’re doing. So I know when he turns one, to two, to three, then I’ll know what to do, too—my sister just guide me and tell me what I’m doing wrong, or tell me what I’m doing right.”

Throughout the focus group discussion, the participants also made comments about how they differentiated “good” from “bad” parenting, coded as Parenting Ability-Valuation (8%). The adolescents associated good parenting with the importance of developing an attachment to the baby, prioritizing the needs of the child above their own, and having good role models for the child. An area that the majority of adolescent mothers agreed on was their desire to “let (their) kids know that as they’re growing up that they weren’t a mistake,” and they discussed what it meant to prioritize their child’s needs:

“I think, I think a good mother is someone that put their child’s first, like, like even when it come to like doing stuff that you want to do, when it comes to moneywise, when it come to your spare time.”

The majority of adolescent mothers in the study also discussed how becoming a mother led to increased emotional maturity as well as more responsible management of practical tasks (time management, financial issues, coordinating for childcare). This theme was captured by the fourth code Responsibilities—Increased Maturity (7.7%).

“I’m more mature than what I was. You ain’t able to do all the stuff you was able to do before you was pregnant. Yeah. You got to get used to that—Can’t go to the club [laughter]. Can’t go to parties. You can’t do what you want to do. You can’t be yourself no more, it’s about you and your child, you got to do what your child needs and what he want to do-or she.”

Some participants commented on responding to threats of violence at school and in their neighborhoods. Concerns for the safety of the mother and baby highlight how adolescent mothers might face unique circumstances during pregnancy. A unique description of an incident faced by one of the adolescent mothers was concern for her baby’s safety after people found out that she was pregnant:

“If people dislike you, threaten you, something like that, because I know the guy I thought who was the father, his cousin is like, “I’m going to kill your baby.” Weird stuff like that. Like he’s real weird. I go to school with him every day. So I see him every day. So, he tried to hire my best friend to punch me in the stomach when I was pregnant.”

In terms of support, healthcare providers are in the unique position of providing support to teenage mothers because they are among the first contacts when a teen is pregnant. Several of the participants’ interactions with health care providers were described as less than favorable. One participant described how she felt judged during a visit with a health care professional:

“I think the doctors treat like women better than they treat like teenagers, for some reason—I went to [names a hospital]—but they rejected me. They just looked at me like I was stupid or did something wrong. They’re like-the one doctor was like, how old are you? I was like, pretty young. He goes, “You shouldn’t have had a baby.” I was like that you’re going to judge me now, out of every teenager that comes here pregnant?”

4. DISCUSSION

During the focus groups, Social Support was the most frequently discussed topic. The current study and previous research suggest the importance of adolescents’ receipt of social support that matches their needs and expectations. One previous study demonstrated that social support and postpartum depression in adolescents can be detrimental if the support does not match the adolescent mother’s desires/expectations, particularly when they receive excess support [1], which could result in the adolescent viewing herself as incapable, incompetent, or inadequate [28,29].

The second theme of teen mothers versus adult mothers highlighted the difficulty of balancing the challenges of adolescence and motherhood. The participants discussed the need to have role models and examples of how to parent from different adults in their lives. Depression is inversely related to maternal competence, and maternal self-perceived care taking ability might affect the developing infant-mother relationship [30,31]. The participants reported having more confidence in their parenting abilities when they had role models, particularly relatives they observed completing parental activities. Previous research supports the potential benefits for the infant and mother with the use of home visits [32]. The participants’ advocacy for role models lends further support to the potential benefits of home visits and experiential parenting programs tailored to adolescent mothers that could provide examples of effective parenting strategies.

The third theme of Parenting Ability-Valuation identified the characteristics that adolescent mothers believe contribute to the differentiation between a “good” mother and a “bad” mother. This finding highlights the importance of further understanding the impact of such evaluations on maternal competence, particularly because maternal competence could effectively be targeted in treatment programs.

The adolescents reported feeling a sense of Increased Maturity as the fourth most frequently discussed theme. Several participants discussed how they felt more able to handle challenges in their lives. This is similar to other studies when adolescents expressed hope and vision for their futures, and a sense that their lives had been positively affected by becoming a mother [12,33,34]. Other studies have reported that adolescent mothers “experienced a deep sense of regret over what could have been: a life with their friends, and planning for college and their futures” [12]. Future goals, or discussions of how motherhood affected plans for the future (i.e. education, career), was not a frequently discussed theme in this study (2.6%).

According to the CES-D scores, 35.3% of the sample reached a cut off that indicated high depressive symptoms. Yet, Motherhood-Drawbacks/Depression (3.8%) was not a frequently discussed theme. This code was used when there were discussions of negative feelings about being a mother or experiencing negative feelings/ emotions after becoming a mother, including direct or indirect discussions of depression. Although the participants were reporting depressive symptoms on the assessment measure, they rarely verbalized these depressive symptoms. Future research could help better understand how adolescent mothers experience and interpret depressive symptoms.

Social Stigma, a code used when adolescent mothers felt they were judged or misunderstood by others, although not one of the most frequently discussed themes (4.4%), provided interesting information about the treatment of adolescent mothers by some health care providers. Logsdon and Koniak-Griffin [35] identified the importance of assessing social support for postpartum adolescents during each encounter with a health care provider, and implementing support interventions when needed. Health care providers can improve their treatment of adolescent mothers by understanding the impact of their interactions.

The open ended format of the focus groups was a strength that allowed themes to authentically emerge as the adolescent mothers talked about their personal experiences. This format provided an opportunity for adolescent mothers to give voice to their experience without being limited to topics that historically have been emphasized with an adult mother population. The promise of anonymity also invited the adolescents to discuss their honest experience.

One limitation of the study was the small sample size. The mothers were primarily African American, Medicaid insured sample, and they volunteered to participate. These factors limit the generalizability. The aforementioned anonymity of specific statements was also a limitation, as we cannot discern if certain themes are more relevant to mothers who experience depressive symptoms.

The specific themes that the adolescents highlighted in this study can inform future studies of teenage mothers. Assessment measures, treatment, and prevention programs might benefit from specifically addressing the top themes that emerged from the focus groups: the impact of social support; comparisons between their experiences as a teen mother versus what they expected it would be like for older women; having role models; ideas about “good” and “bad” parenting; and the potential benefits of increased maturity. Development of more effective assessment measures, treatment protocols, and prevention programs for adolescent mothers have the potential to increase intervention benefits for the mother, infant, and family system.

REFERENCES

- Logsdon, M.C., Birkimer, J.C., Simpson, T. and Looney, S. (2005) Postpartum depression and social support in adolescents. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 34, 46-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0884217504272802

- Cutrona, C.E. and Troutman, B.R. (1986) Social support, infant temperament, and parenting self-efficacy: A mediational model of postpartum depression. Child Development, 57, 1507-1518. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1130428

- Logsdon, M.C., Birkimer, J.C. and Usui, W.M. (2000) The link of social support and postpartum depressive symptoms in African-American women with low incomes. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 25, 262-266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005721-200009000-00009

- Logsdon, M.C. and Usui, W. (2001) Psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression in diverse groups of women. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 23, 563-574.

- Flaherty, M.J. (1988) Seven caring functions of black grandmothers in adolescent mothering. Maternal-Child Nursing Journal, 17, 191-207.

- Stevenson, W., Maton, K.I. and Teti, D.M. (1999) Social support, relationship quality, and well-being among pregnant adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 109-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jado.1998.0204

- Gaynes, B.N., Gavin, N., Meltzer-Brody, S., Lohr, K.N., Swinson, T., Gartlehner, G., Brody, S. and Miller, W.C. (2005) Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (Summary), 1-8.

- Turner, R.J., Grindstaff, C.F. and Phillips, N. (1990) Social support and outcome in teenage pregnancy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 31, 43-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2137044

- Beardslee, W.R., Zuckerman, B.S., Amaro, H. and McAllister, M. (1988) Depression among adolescent mothers: A pilot study. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 9, 62-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004703-198804000-00002

- Barnet, B., Joffe, A., Duggan, A.K., Wilson, M.D. and Repke, J.T. (1996) Depressive symptoms, stress, and social support in pregnant and postpartum adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 150, 64-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170260068011

- Schmidt, R.M., Wiemann, C.M., Rickert, V.I. and Smith, E.O. (2006) Moderate to severe depressive symptoms among adolescent mothers followed four years postpartum. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 712-718. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.023

- Clemmens, D.A. (2002) Adolescent mothers’ depression after the birth of their babies: Weathering the storm. Adolescence, 37, 551-565.

- Beck, C.T. (1998) The effects of postpartum depression on child development: A meta-analysis. Arch Psychiatr Nurs, 12, 12-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9417(98)80004-6

- Gross, D. (1989) Implications of maternal depression for the development of young children. Image—The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 21, 103-107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1989.tb00108.x

- Murray, L. (1992) The impact of postnatal depression on infant development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 33, 543-561. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00890.x

- Uddenberg, N. and Englesson, I. (1978) Prognosis of post partum mental disturbance. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 58, 201-212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1978.tb06933.x

- Cogill, S.R., Caplan, H.L., Alexandra, H., Robson, K.M. and Kumar, R. (1986) Impact of maternal postnatal depression on cognitive development of young children. British Medical Journal, 292, 1165-1167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.292.6529.1165

- Whiffen, V.E. and Gotlib, I.H. (1989) Infants of postpartum depressed mothers: Temperament and cognitive status. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98, 274-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.98.3.274

- Gross, D., Conrad, B., Fogg, L., Willis, L. and Garvey, C. (1995) A longitudinal study of maternal depression and preschool children’s mental health. Nursing Research, 44, 96-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199503000-00006

- Mercer, R.T. (1985) The process of maternal role attainment over the first year. Nursing Research, 34, 198-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006199-198507000-00002

- Nunes, A.P. and Phipps, M.G. (2013) Postpartum depression in adolescent and adult mothers: Comparing prenatal risk factors and predictive models. Maternal-Child Nursing Journal, 17, 1071-1079.

- Radloff, L.S. (1977) The CES-D scale A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385-401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Roberts, R.E. (1992) Manifestation of depressive symptoms among adolescents. A comparison of Mexican Americans with the majority and other minority populations. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180, 627-633. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199210000-00003

- Beeghly, M., Weinberg, M.K., Olson, K.L., Kernan, H., Riley, J. and Tronick, E.Z. (2002) Stability and change in level of maternal depressive symptomatology during the first postpartum year. Journal of Affective Disorders, 71, 169-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00409-8

- Barkin, J.L., Wisner, K.L., Bromberger, J.T., Beach, S.R. and Wisniewski, S.R. (2010) Assessment of functioning in new mothers. Journal of Women’s Health, 19, 1493- 1499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2009.1864

- Boyatzis, R.E. (1998) Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications, Incorporated, Thousand Oaks.

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K.M. and Namey, E.E. (2011) Applied thematic analysis. Sage Publications, Incorporated, Thousand Oaks.

- Cutrona, C.E. and Russell, D.W. (1990) Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In: Sarason, B. R., Sarason, I. G. and Pierce G. R. Eds., Social Support: An Interactional View, Wiley, New York, 319-366.

- Franks, F. and Faux, S.A. (1990) Depression, stress, mastery, and social resources in four ethnocultural women’s groups. Research in Nursing & Health, 13, 283-292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770130504

- Cox, J.E., Buman, M., Valenzuela, J., Joseph, N.P., Mitchell, A. and Woods, E.R. (2008) Depression, parenting attributes, and social support among adolescent mothers attending a teen tot program. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 21, 275-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2008.02.002

- Hudson, D.B., Elek, S.M. and Campbell-Grossman, C. (2000) Depression, self-esteem, loneliness, and social support among adolescent mothers participating in the new parents project. Adolescence, 35, 445-453.

- Koniak-Griffin, D., Verzemnieks, I.L. Anderson, N.L., Brecht, M.L., Lesser, J., Kim, S., and Turner-Pluta, C. (2003) Nurse visitation for adolescent mothers: Two-year infant health and maternal outcomes. Nursing Research, 52, 127-136. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200303000-00009

- Arenson, J.D. (1994) Strengths and self-perceptions of parenting in adolescent mothers. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 9, 251-257.

- Leonard, L.G. (1998) Depression and anxiety disorders during multiple pregnancy and parenthood. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 27, 329- 337. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02656.x

- Logsdon, M.C. and Koniak-Griffin, D. (2005) Social support in postpartum adolescents: Guidelines for nursing assessments and interventions. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 34, 761-768. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0884217505281855

NOTES

*Declaration of Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Heinz Endowments.

#Corresponding author.