Pain Studies and Treatment

Vol.2 No.1(2014), Article ID:42018,4 pages DOI:10.4236/pst.2014.21004

Use of oral ketamine for analgesia during reduction/manipulation of fracture/dislocation in the Emergency Room: An initial experience in a low-resource setting

![]()

1Department of Anaesthesia, Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Zaria, Nigeria; *Corresponding Author: drnwasor@yahoo.com

2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Zaria, Nigeria

Copyright © 2014 E. Ogboli-Nwasor et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property E. Ogboli-Nwasor et al. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian.

Received 15 November 2013; revised 22 December 2013; accepted 15 January 2014

KEYWORDS

Oral Ketamine; Analgesia; Fracture/Dislocation; Emergency Room

ABSTRACT

Background: The use of ketamine for relief of procedure-related pain is limited in our environment. Ketamine, a phencyclidine derivative commonly used for induction and maintenance of anaesthesia, is administered routinely via the intravenous and intramuscular routes. One of the concerns while using ketamine for analgesia via these two routes is that the drug may produce anaesthesia, rather than analgesia alone. Aims and Objectives: We sought to find out if ketamine given via the oral route could be used to provide analgesia during minor orthopaedic procedures in the Emergency Room. We also wanted to find out if there were side-effects peculiar to the oral route. Methods: A prospective observational pilot study in consecutive patients with fractures/dislocation presenting to our ER was recruited into the study. All patients gave informed consent. Reduction of fractures was done 15 minutes following the administration of ketamine 5 mg/kg orally. The patients were observed during and after the procedure and the findings entered into a proforma. The data obtained were analyzed using simple statistical methods and the results presented in a table. The findings are discussed. Results: There were 9 males and 2 females with an age range of 4 yrs to 48 yrs. Pain levels were assessed using verbal rating scales. Seven patients (64%) had severe pain before administration of ketamine while 2 patients (18%) each had mild and mod- erate pain respectively. Four patients had Colle’s fracture only and 1 patient had a Colle’s fracture with a supracondylar femoral fracture. Two patients had tibial fractures, one patient had a complete knee dislocation, while 2 others had ulnar/radial fractures. One other patient had humeral and tibial fractures. For up to 15 minutes after the procedures all but one patient were pain-free. Five (5) patients (45.5%) were noticed to have drowsiness, 3 patients (27%) were sedated while 2 patients (18%) had no side-effects at all. Five (5) patients (45.5%) reported excellent analgesia while 6 patients (64%) said the intra and post procedure analgesia was very good. Conclusions: Oral ketamine may be useful in providing analgesia for minor procedures in the emergency room. Ketamine when sweetened with a soda drink appears to be palatable with a rapid onset of action and few side effects. Thus ketamine given orally may be a cheaper and more accessible option for effective pain-relief in the emergency room. There is a need to conduct more studies on a larger number of patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

Procedural sedation is defined as a method “to induce a state that allows the patient to tolerate unpleasant procedures while maintaining cardiorespiratory function independently and continuously” [1]. According to O’Donnell et al., procedural sedation and analgesia is defined as a drug-induced state of diminished awareness, pain, and memory that allows a patient to maintain his or her own protective reflexes and ability to move purposefully [2].

The use of procedural sedation has been embraced by physicians and patients alike for enabling short turnaround noxious procedures to be performed entirely within the Emergency Department (ED)—in many cases curtailing the need for hospital admission. Numerous literature reviews have been published describing accepted methodology and limitations of procedural sedation [3-5], suitable pharmacologic agents [5,6], evidence of safety and increased patient satisfaction [7], in addition to the evidence behind fasting status recommendations [8,9].

Methods: Following institutional ethical approval, a total of 11 consecutive patients with fractures/dislocation were seen over a 1-month period in our emergency room and recruited into the study. All patients gave informed consent (informed consent for minors was given by the parent/guardian). There were 9 males and 2 females with an age range of 4 yrs to 48 yrs. Pain levels were assessed using verbal rating scales. Seven patients (64%) had severe pain before administration of ketamine while 2 patients (18%) each had mild and moderate pain respectively. Reduction of fractures was done 15 minutes following the administration of ketamine 5 mg/kg orally. The patients were observed during and after the procedure and the findings entered into a proforma. The data obtained were analyzed using simple statistical methods and the results presented in a table. The findings are hereby discussed.

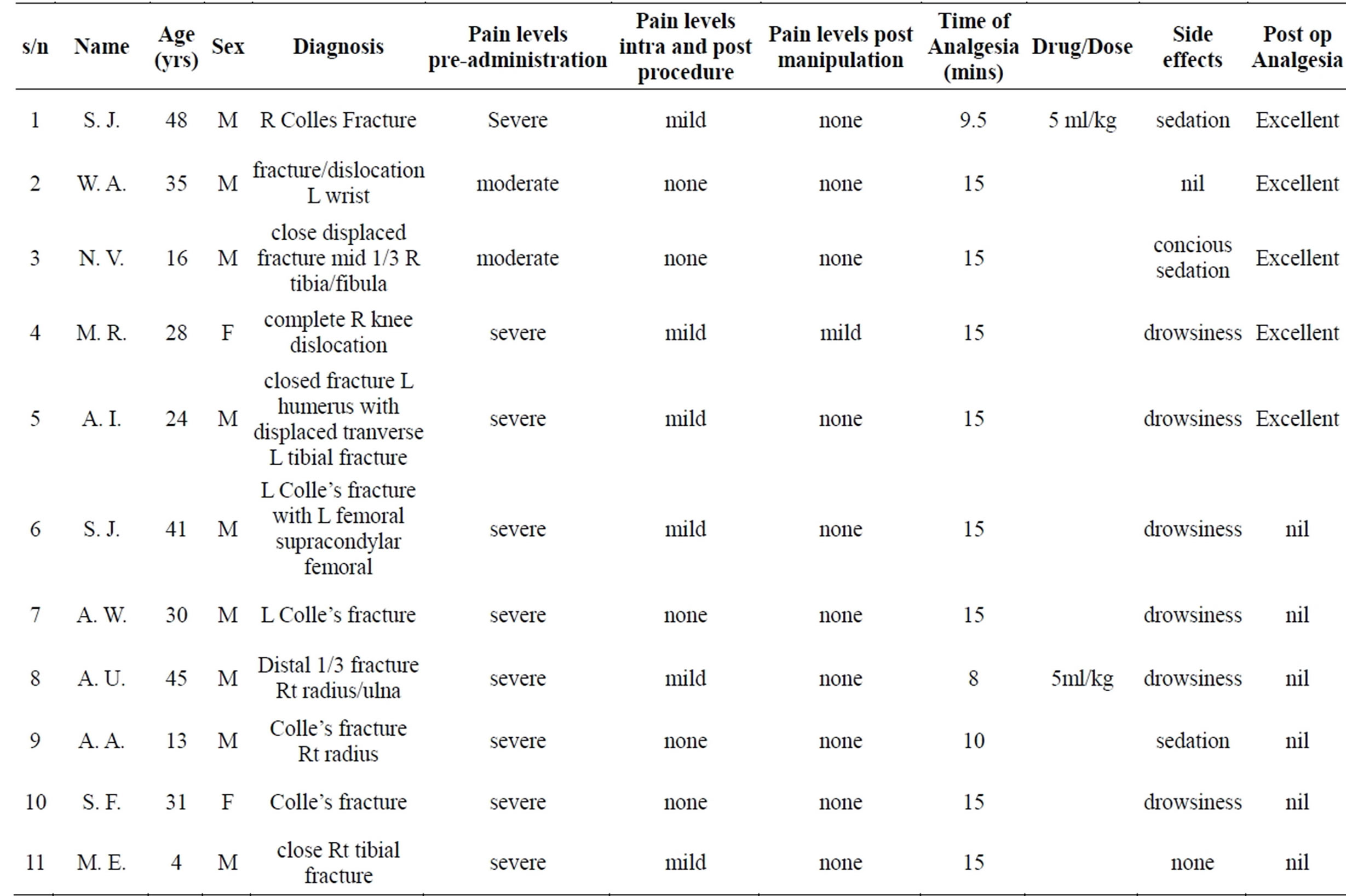

Results: Four patients had Colle’s fracture only and 1 patient had a Colle’s fracture with a supracondylar femoral fracture. Two patients had tibial fractures, one patient had a complete knee dislocation while 2 others had ulnar/radial fractures. One other patient had humeral and tibial fractures. During the procedure, only one patient (11%) reported moderate pain while all others had mild pain. For up to 15 minutes after the procedures, all but one patient were pain-free. On side-effects, 5 patients (45.5%) were noticed to have drowsiness, 3 patients (27%) were sedated while 2 patients (18%) had no side-effects at all. When asked to comment on the analgesia experience, 5 patients (45.5%) reported being completely pain-free during and shortly after the procedure while 6 patients (64%) reported mild pain in the intra and postoperative period (see Table 1).

Table 1. Patients demographics and pain experience.

2. DISCUSSION

Ketamine is an ideal agent to facilitate short painful procedures, especially in children, who might otherwise require other general anaesthetic agents. It has many features that are attractive in the ED setting: rapid onset (less than 5 minutes IM or IV), consistently effective analgesia and amnesia, and airway stability [10].

Ketamine can be administered intravenously, intramuscularly, orally, nasally, and rectally [11]. Most clinical use involves the intravenous and intramuscular routes, by which the drug rapidly achieves therapeutic levels. Ketamine can also be given epidurally and intrathecally for operative and postoperative pain control. The dose used in cancer pain is 1.0 mg (with benzethonium chloride as preservative and 0.05 mg morphine) twice daily, with additional morphine as required [12].

Ketamine has also been administered orally in doses of 3 to 10 mg/kg, with 6 mg/kg providing optimal conditions in 20 to 25 minutes in one study and 10 mg/kg providing sedation in 87 percent of children within 45 minutes in another study [13,14]. In our study we used a dose of 5 mg/kg orally and we noted onset of action within 15 minutes and optimal conditions within 20 minutes in most patients.

The use of concomitant drugs such as benzodiazepines permits a lower dose requirement for ketamine while enhancing recovery by reducing emergence reactions. Though we did not administer diazepam concomitantly, emergence reactions and hallucinations were not noted in our patients.

In a study by Damle et al comparing oral ketamine and oral midazolam as sedative agents in pediatric dentistry in India, the sedative drugs used as premedication for the study were oral ketamine 5 mg/kg and oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg [15]. The oral route was chosen in this study as it was the most acceptable and familiar mode of drug administration [16-18]. Ketamine and midazolam are not available for oral administration in India and hence the syrup made was up of (levulose 40.5%, dextrose 34.02%, sucrose 1.9%, water 17.7%, and gum and dextrin) to bring volume to 10 ml; was mixed with honey this served to mask the bitter taste of the drug [19]. In Nigeria, Ketamine is not available for oral administration, so we used 10 - 20 mls of a soda drink (Fanta®) to sweeten it. This combination appears to be palatable as none of the patients complained about the taste.

Ketamine provides well-documented anaesthesia and analgesia. It has a wide margin of safety, as the protective reflexes are usually maintained [20,21]. This is a report of our initial experience in our emergency room. None of our patients had nausea or vomiting and there was no case of regurgitation or aspiration. The small volume of the oral dose (max 20 mls) is useful in ensuring that the volume of the gastric contents is minimal.

3. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The numbers in this preliminary report are inadequate to draw far reaching conclusions. There is a need to conduct more studies on a larger number of patients.

4. CONCLUSION

Orally administered ketamine may be useful in providing analgesia for minor procedures in the Emergency Room. Ketamine when sweetened with a soda drink appears to be palatable with a rapid onset of action and few side effects. This will avoid the fear of opioids and opioidrelated side-effects. Opioids are often not available and may be expensive. Thus ketamine given orally may be a cheaper and more accessible option for effective painrelief in the emergency room. However, the number in this preliminary report is too few to draw far reaching conclusions. There is a need to conduct more studies on a larger number of patients.

REFERENCES

- American College of Emergency Physicians (1998) Clinical policy for procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 31, 663-677. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70216-1

- O’Donnell, J., Bragg, K. and Sell, S. (2003) Procedural sedation: Safely navigating the twilight zone. Nursing, 33, 36-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00152193-200304000-00035

- Flood, R. and Krauss, B. (2003) Procedural sedation and analgesia for children in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, 21, 121- 139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0733-8627(02)00084-6

- Innes, G., Murphy, M., Nijssen-Jordan, C., et al. (1999) Procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Canadian consensus guidelines. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 17, 145-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0736-4679(98)00135-8

- Meredith, J., O’Keefe, K. and Galwankar, S. (2008) Pediatric procedural sedation and analgesia. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma and Shock, 1, 88-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0974-2700.43189

- Mace, S., Barata, I., Cravero, J., et al. (2004) Clinical policy: Evidence based approach to pharmacological agents used in pediatric sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 39, 1472-1484. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.07.002

- Freeston, J., Leal, A. and Gray, A. (2010) Procedural sedation and recall in the emergency department: The relationship between depth of sedation and patient recall and satisfaction (a pilot study). Emergency Medicine Journal, in press.

- Thorpe, R. and Benger, J. (2010) Pre-procedural fasting in emergency sedation. Emergency Medicine Journal, 27, 254-261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/emj.2008.069120

- Green, S. and Krauss, B. (2002) Pulmonary aspiration risk during emergency department procedural sedation—An examination of the role of fasting and sedation depth. Academic Emergency Medicine, 9, 35-42.

- Babl, F., Theophilos, T., Barrett, T. and McKenzie, I. (2008) Paediatric Procedural Sedation Emergency Department, Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Australia, Sedation Manual, 2nd Edition. http://www.rch.org.au/emplibrary/emerg_rch/SedationManualDec2008_final.pdf

- Gerald Reves, J., Peter, S.A. Glass and Lubarsky, D.A. (2000) Scientific principles part B: Intravenous anesthetics Chapter 9: Nonbarbiturate intravenous anesthetics. Churchill Livingstone. http://web.squ.edu.om/med-Lib/MED_CD/E_CDs/anesthesia/site/content/v02/020260r00.htm

- Yang, C.Y., Wong, C.S., Chang, J.Y., et al. (1996) Intrathecal ketamine reduces morphine requirements in patients with terminal cancer pain. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 43, 379. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03011718

- Gutstein, H.B., Johnson, K., Heard, M.B., et al. (1992) Oral ketamine preanesthetic medication in children. Anesthesiology, 76, 28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199201000-00004

- Tobias, J.D., Phipps, S., Smith, B., et al. (1992) Oral ketamine premedication to alleviate the distress of invasive procedures in pediatric oncology patients. Pediatrics, 90, 537.

- Damle, S.G., Gandhi, M. and Laheri, V. (2008) Comparison of oral ketamine and oral midazolam as sedative agents in pediatric dentistry. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, 26, 97-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0970-4388.43186

- Alderson, P.J. and Lerman, J. (1994) Oral premedication for pediatric ambulatory anaesthesia: A comparison of midazolam and ketamine. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 41, 221-226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03009834

- Kogan, A., Katz, J., Efrat, R. and Eidelman, L.A. (2002) Premedication with midazolam in young children: A comparison of four routes of administration. Pediatric Anesthesia, 12, 685-689. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00918.x

- Sullivan, D.C., Webb, M.D. and Wilson, C.F.G. (2001) A comparison of two oral ketamine-diazepam regimens for sedation of anxious pediatric dental patients. Pediatric Dentistry, 23, 233-237.

- Vetter, T.R. (1993) A comparison of midazolam, diazepam and placebo as oral anesthetic premedicants in younger children. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 5, 58- 61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0952-8180(93)90090-2

- Alfonzo-Echeverri, E.C., Berg, J.H., Wild, T.W. and Glass, N.L. (1993) Oral ketamine for pediatric outpatient dental surgery sedation. Pediatric Dentistry, 15, 182-185.

- Sekerci, C., Dφnmez, A., Ate, Y. and Okten, F. (1997) Oral ketamine premedication in children (placebo controlled double-blind study). European Journal of Anaesthesiology, 13, 606-611. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003643-199611000-00011