American Journal of Operations Research

Vol.05 No.06(2015), Article ID:61218,10 pages

10.4236/ajor.2015.56041

A Dynamic Active-Set Method for Linear Programming

Alireza Noroziroshan*, H. W. Corley, Jay M. Rosenberger

IMSE Department, The University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, USA

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 25 October 2015; accepted 15 November 2015; published 18 November 2015

ABSTRACT

An efficient active-set approach is presented for both nonnegative and general linear programming by adding varying numbers of constraints at each iteration. Computational experiments demonstrate that the proposed approach is significantly faster than previous active-set and standard linear programming algorithms.

Keywords:

Constraint Optimal Selection Techniques, Dynamic Active-Set Methods, Large-Scale Linear Programming, Linear Programming

1. Introduction

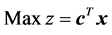

Consider the linear programming problem

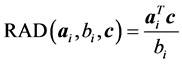

(P) (1)

(1)

s.t.

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

where x and c are the n-dimensional column vectors of variables and objective coefficients, respectively, and z represents the objective function. The matrix A is an m × n matrix  with row vectors

with row vectors ; b is an m-dimensional column vector; and 0 is an n-dimensional column vector of zeros. The non-polynomial simplex methods and polynomial interior-point barrier-function algorithms illustrate the two different approaches to solve problem P. There is no single best algorithm [1] . For any existing approach, there is a problem instance for which the developed method performs poorly [2] [3] . However, interior point methods do not provide efficient post-optimality analysis, so the simplex algorithm is the most frequently used approach [2] , even for sparse large scale linear programming problems where barrier methods perform extremely well. In fact, the simplex method has been called “the algorithm that runs the world” [4] ; yet it often cannot efficiently solve the large scale LPs required in many applications.

; b is an m-dimensional column vector; and 0 is an n-dimensional column vector of zeros. The non-polynomial simplex methods and polynomial interior-point barrier-function algorithms illustrate the two different approaches to solve problem P. There is no single best algorithm [1] . For any existing approach, there is a problem instance for which the developed method performs poorly [2] [3] . However, interior point methods do not provide efficient post-optimality analysis, so the simplex algorithm is the most frequently used approach [2] , even for sparse large scale linear programming problems where barrier methods perform extremely well. In fact, the simplex method has been called “the algorithm that runs the world” [4] ; yet it often cannot efficiently solve the large scale LPs required in many applications.

In this paper we consider both the general linear program (LP) and the special case with  and

and ,

, ;

; ; and

; and , which is called a nonnegative linear program (NNLP). NNLPs have some useful properties that simplify their solution, and they model various practical applications such as determining an optimal driving route using global positioning data [5] and updating airline schedules [6] , for example. We propose active-set methods for LPs and NNLPs. Our approach divides the constraints of problem P into operative and inoperative constraints at each iteration. Operative constraints are those active in a current relaxed subproblem Pr,

, which is called a nonnegative linear program (NNLP). NNLPs have some useful properties that simplify their solution, and they model various practical applications such as determining an optimal driving route using global positioning data [5] and updating airline schedules [6] , for example. We propose active-set methods for LPs and NNLPs. Our approach divides the constraints of problem P into operative and inoperative constraints at each iteration. Operative constraints are those active in a current relaxed subproblem Pr,  of P, while the inoperative ones are constraints of the problem P not active in Pr. In our active-set method we iteratively solve Pr,

of P, while the inoperative ones are constraints of the problem P not active in Pr. In our active-set method we iteratively solve Pr,  of P after adding one or more violated inoperative constraints from (2) to

of P after adding one or more violated inoperative constraints from (2) to  until the solution

until the solution  to Pr is a solution to P.

to Pr is a solution to P.

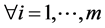

Active-set methods have been studied by Stone [7] , Thompson et al. [8] , Myers and Shih [9] , and Curet [10] , for example. More explicitly, Adler et al. [11] suggested a random constraint selection rule, in which a violated constraint was randomly added to the operative set. Bixby et al. [1] developed a sifting method for problems having wide and narrow structure. In effect, the sifting method is an active-set method for the dual. Zeleny [12] used a constraint selection rule called VIOL here, which added the constraint most violated at each iteration. Mitchell [13] used a multi-cut version of the VIOL for an interior point cutting plane algorithm. Corley et al. [14]

developed a cosine simplex algorithm where a single violated constraint maximizing  was

was

added to the operative set. Junior and Lins [15] used a similar cosine criterion to determine an improved initial basis for the simplex algorithm.

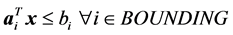

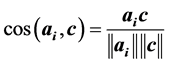

References [6] [16] and [17] are the most directly related to the current work. The constraint optimal selection technique (COST) RAD was introduced in [6] and [16] as a constraint selection metric for NNLPs, and then generalized in [17] to GRAD for LPs. In RAD and GRAD, an initial problem P0 is formulated from P such that all variables are bounded by at least one constraint, which may be an artificial bounding constraint

The paper is organized as follows. The constraint selection metric and dynamic active-set conjunction with RAD and GRAD is given in Section 2. In Section 3, we describe the problem instances and CPLEX preprocessing settings. Section 4 contains computational experiments for both NNLPs and LPs. Then the performance of the new methods is compared to the previous ones as well as the CPLEX simplex, dual simplex, and barrier method. In Section 5, we present conclusions.

2. A Dynamic Active-Set Approach

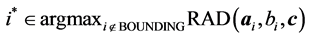

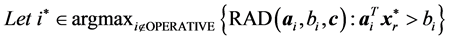

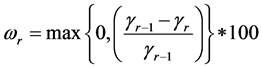

The purpose of our dynamic active-set method is to add violated constraints to problem Pr more effectively than in [6] and [17] . In COST RAD of [6] for NNLPs we use the constraint selection metric

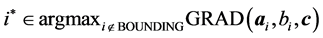

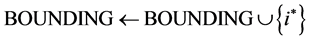

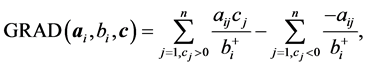

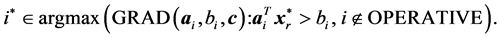

to order constraints from highest to lowest value of RAD as a geometric heuristic for determining the constraints most likely to be binding at optimality. Moreover, at each iteration in [6] we add violated constraints in order of decreasing RAD until the added constraints contain non-zero coefficients for all variables. In similar fashion for COST GRAD of [17] , we use the constraint selection metric

where

for a small positive constant ε and

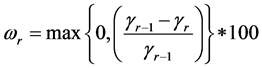

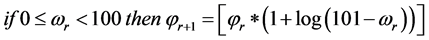

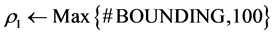

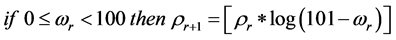

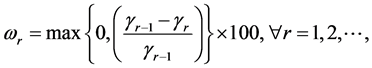

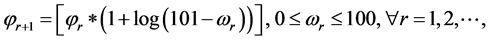

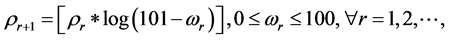

In this paper we propose a dynamic method that adds a varying number of constraints to Pr that depends on the progress made at

2.1. Dynamic Active-Set Approach for NNLP

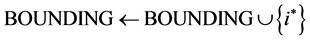

The dynamic active-set approach developed for solving NNLPs is as follows. Constraints are initially ordered by the RAD constraint selection metric (4). To construct P0, we choose constraints from (2) in descending order of RAD until each variables xj has an

where

where

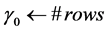

Pseudocode for the dynamic active-set NNLPs is as follows.

Step 1―Identify constraints to initially bound the problem.

1:

2: while

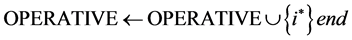

3: Let

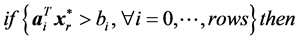

4: if

5:

6: end if

7:

8:

9: end while

Step 2―Using the primal simplex method, obtain an optimal solution

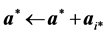

Step 3―Perform the following iterations until an optimal solution to problem P is found.

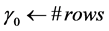

1:

2:

3:

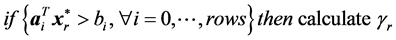

4:

5:

6:

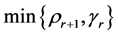

7: Calculate

8:

9:

10: for (i = 0 to

11: Solve the following Pr by the dual simplex method to obtain

12: else if (ωr = 100) then Optimized ¬ true//

13: end if

14: else Optimized ¬ true//

15: end if

16: end while

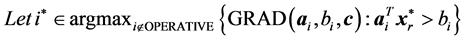

2.2. Dynamic Active-Set Approach for LP

The dynamic active-set approach for solving LP similar to the one for NNLPs. We construct P0 by choosing a number of constraints

where the value

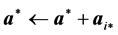

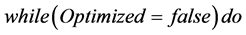

Pseudocode for the dynamic active-set for LPs is as follows.

Step 1―Identify constraints to initially bound the problem.

1:

2: while

3: Let

4: if

5:

6: end if

7:

8: Optimized ¬ false

9: end while

Step 2―Using the primal simplex method, obtain an optimal solution

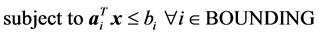

subject to

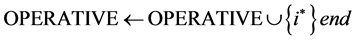

Step 3―Perform the following iterations until an optimal solution to problem P is found.

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7: Calculate

8:

9:

10: for (i = 0 to

11: Solve the following Pr by the dual simplex method to obtain

12: end if

13: else Optimized ¬ true//

14: end if

15: end while

3. Problem Instances and CPLEX Preprocessing

Four sets of NNLPs used in [6] are considered to evaluate the performance of the developed algorithm. Each problem set contains five problem instances for 21 different density levels and for varying ratios of (m constraints)/(n variables) from 200 to 1. Each set contains 105 randomly generated NNLPs with various densities p ranging from 0.005 to 1. Randomly generated real numbers between 1 and 5, 1 and 10, 1 and 10 were assigned to the elements of A, b and c respectively. To avoid having a constraint in the form of an upper bound on a variable, each constraint is required to have at least two non-zero

Two parameters that CPLEX uses for solving linear programming are PREIND (preprocessing pre-solve indicator) and PREDUAL (preprocessing dual). As described in [17] and [6] , when parameter setting PREIND = 1 (ON), the preprocessing pre-solver is enabled and both the number of variables and the number of constraints is reduced before any type of algorithm is used. By setting PREIND = 0 (OFF) the pre-solver routine in CPLEX is disabled. PREDUAL is the second preprocessing parameter in CPLEX. By setting parameter PREDUAL = 0 (ON) or −1 (OFF), CPLEX automatically selects whether to solve the dual of the original LP or not. Both are used with the default settings for the CPLEX primal simplex method, the CPLEX dual simplex method, and the CPLEX barrier method. Neither CPLEX pre-solver nor PREDUAL parameters were used in any part of the developed dynamic active-set methods for NNLPs and LPs.

4. Computational Experiments

The computations were performed on an Intel Core (TM) 2 Duo X9650 3.00 GHz with a Linux 64-bit operating system and 8 GB of RAM. The developed methods use IBM CPLEX 12.5 callable library to solve linear programming problems. The dynamic RAD and dynamic GRAD are compared with the previously developed COST RAD and COST GRAD, respectively, as well as VIOL, the CPLEX primal simplex method, the CPLEX dual simplex method, and the CPLEX barrier method.

4.1. Computational Results for NNLP

Table 1 illustrates the performance comparison between dynamic RAD method and the previously defined constraint selection technique COST RAD on Set 1 to Set 4 for various dimensions of the matrix A used in [6] . Both methods are compared with the CPLEX barrier method (interior point), the CPLEX primal simplex method, and the CPLEX dual simplex method. The worst performance occurs at m/n ratio of 200, where on average, dynamic

Table 1. Results from dynamic RAD and COST RAD for set 1-set 4, (random, NNLP aij = 1 − 5, bi = 1 − 10, cj = 1 − 10).

+Used CPLEX preprocessing parameters of presolve = off and predual = off. ++Average of 5 instances of LPs at each density.

RAD is 8% faster than COST RAD for densities less than 0.2 and 18% slower for densities above 0.2. When the density increases, dynamic RAD shows an increase in computation time more than that of COST RAD. On the other hand, for an m/n ratio of 20 the CPU times decrease with an increase in density. For higher densities above 0.01, dynamic RAD is more efficient and takes less computation times than COST RAD. On average, dynamic RAD is 10% more efficient than COST RAD. For an m/n ratio of 2 at densities higher than 0.009, the data show that COST RAD starts taking significantly more time than dynamic RAD. Dynamic RAD was 5.5% faster than COST RAD over all densities and 21% faster on average for densities above 0.5. For an m/n ratio of 1 with densities greater than 0.01, dynamic RAD is about 8% more efficient than COST RAD. On average, dynamic RAD is superior performance to COST RAD for problem sets 2, 3, and 4.

Table 2 from [6] is presented to provide an immediate comparison of the developed dynamic RAD method with the standard CPLEX solvers. A reporting limit of 3000 seconds was used. On average, the CPU times for dynamic RAD were faster than any of the CPLEX solvers across all densities and ratios. However, CPLEX barrier methods show smaller CPU times when ratio m/n = 20 and the density is less than or equal to 0.01.

Table 2. Results from the CPLEX primal, the dual simplex, and the barrier method for set 1-set 4, (random, NNLP aij = 1 − 5, bi = 1 − 10, cj = 1 − 10) [6] .

−−Used CPLEX preprocessing parameters of presolve = ON and predual = Auto; ++Average of 5 instances of LPs at each density; bRuns with CPU times > 3000 s are not reported.

4.2. Computational Results for LP

Table 3 shows computational results for the CPLEX primal simplex method, the dual simplex method, and the interior point barrier method for the general LP problem set used in [17] . CPU times for COST GRAD and VIOL using both the multi-cut technique and dynamic approaches are presented for comparison. Dynamic GRAD is stable over the range of densities. In addition, its performance is superior to multi-cut GRAD for every problem instance. Average CPU times for GRAD using multi-cut method and dynamic approach are 43.87 and 24.57 seconds, respectively, a 42% improvement in computation time. Average computation times for GRAD and VIOL using dynamic approach are 24.57 seconds vs. 33.82 seconds, respectively.

It should be noted that GRAD captures more information than VIOL in higher densities to discriminate between constraints. Interestingly, when the dynamic active-set is used for both GRAD and VIOL, their CPU

Table 3. Comparison of computation times of CPLEX solvers, GRAD, and VIOL using both dynamic active-set and multi- cut method on general LP problem set (random LP with 1000 variables and 200,000 constraints [17] ).

+Used CPLEX preprocessing parameters of presolve = off and predual = off. 1Tx ≤ M = 1010 was used as the bounding constraint; ++Average of 5 instances of LPs at each density; −−Used CPLEX preprocessing parameters of presolve = ON and predual = Auto.

times are significantly faster than the same metrics with the multi-cut method. GRAD using the multi-cut technique takes the longest computation time in comparison to others at higher densities. Unlike the proposed dynamic approach, the LP algorithm

For comparison purposes, Table 4 shows GRAD and VIOL computation times when a fixed number of violated constraints is added at each iteration. Adding a fixed number of constraints is examined for both GRAD and VIOL. At densities below 0.03, dynamic GRAD takes less CPU time than the fixed-cut approach. GRAD

Table 4. Comparison of computation times of GRAD using dynamic active-set and fixed cut method on general LP problem set (random LP with 1000 variables and 200,000 constraints [17] ).

+Used CPLEX preprocessing parameters of presolve = off and predual = off. 1Tx ≤ M = 1010 was used as the bounding constraint; ++Average of 5 instances of LPs at each density.

*Corresponding author.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, dynamic active-set methods have been proposed for both NNLPs and LPs. In particular, these new approaches were compared to existing methods for problems with various sizes and densities. On average, dynamic RAD shows superior performance over COST RAD for the NNLP problem sets 2, 3, and 4. In the LP problem set, dynamic GRAD significantly outperformed the COST GRAD as well as the CPLEX primal simplex and the dual simplex. In this LP problem set, however, the barrier solver did outperform all methods for densities up to 0.03. In addition, dynamic GRAD outperformed a dynamic version of VIOL, which was a standard method in column generation and decomposition methods.

Cite this paper

Alireza Noroziroshan,H. W. Corley,Jay M. Rosenberger, (2015) A Dynamic Active-Set Method for Linear Programming. American Journal of Operations Research,05,526-535. doi: 10.4236/ajor.2015.56041

References

- 1. Bixby, R.E., Gregory, J.W., Lustig, I.J., Marsten, R.E. and Shanno, D.F. (1992) Very Large-Scale Linear Programming: A Case Study in Combining Interior Point and Simplex Methods. Operations Research, 40, 885-897.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/opre.40.5.885 - 2. Rosenberger, J.M., Johnson, E.L. and Nemhauser, G.L. (2003) Rerouting Aircraft for Airline Recovery. Transportation Science, 37, 408-421.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/trsc.37.4.408.23271 - 3. Todd, M.J. (2002) The Many Facets of Linear Programming. Mathematical Programming, 91, 417-436.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s101070100261 - 4. Elwes, R. (2012) The Algorithm That Runs the World. New Scientist, 215, 32-37.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(12)62078-8 - 5. Dare, P. and Saleh, H. (2000) GPS Network Design: Logistics Solution Using Optimal and Near-Optimal Methods. Journal of Geodesy, 74, 467-478.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001900000104 - 6. Saito, G., Corley, H.W., Rosenberger, J.M., Sung, T.-K. and Noroziroshan, A. (2015) Constraint Optimal Selection Techniques (COSTs) for Nonnegative Linear Programming Problems. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 251, 586-598.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2014.11.080 - 7. Stone, J.J. (1958) The Cross-Section Method, an Algorithm for Linear Programming. DTIC Document, P-1490, 24.

- 8. Thompson, G.L., Tonge, F.M. and Zionts, S. (1996) Techniques for Removing Nonbinding Constraints and Extraneous Variables from Linear Programming Problems. Management Science, 12, 588-608.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.12.7.588 - 9. Myers, D.C. and Shih, W. (1988) A Constraint Selection Technique for a Class of Linear Programs. Operations Research Letters, 7, 191-195.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-6377(88)90027-2 - 10. Curet, N.D. (1993) A Primal-Dual Simplex Method for Linear Programs. Operations Research Letters, 13, 233-237.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-6377(93)90045-I - 11. Adler, I., Karp, R. and Shamir, R. (1986) A Family of Simplex Variants Solving an m× d Linear Program in Expected Number of Pivot Steps Depending on d Only. Mathematics of Operations Research, 11, 570-590.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/moor.11.4.570 - 12. Zeleny, M. (1986) An External Reconstruction Approach (ERA) to Linear Programming. Computers & Operations Research, 13, 95-100.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0305-0548(86)90067-5 - 13. Mitchell, J.E. (2000) Computational Experience with an Interior Point Cutting Plane Algorithm. SIAM Journal on Optimization, 10, 1212-1227.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/S1052623497324242 - 14. Corley, H.W., Rosenberger, J., Yeh, W.-C. and Sung, T.K. (2006) The Cosine Simplex Algorithm. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 27, 1047-1050.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00170-004-2278-1 - 15. Junior, H.V. and Lins, M.P.E. (2005) An Improved Initial Basis for the Simplex Algorithm. Computers & Operations Research, 32, 1983-1993.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2004.01.002 - 16. Corley, H.W. and Rosenberger, J.M. (2011) System, Method and Apparatus for Allocating Resources by Constraint Selection. US Patent No. 8082549.

- 17. Saito, G., Corley, H.W. and Rosenberger, J. (2012) Constraint Optimal Selection Techniques (COSTs) for Linear Programming. American Journal of Operations Research, 3, 53-64.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajor.2013.31004

NOTES

*Corresponding author.