B. DEHURY

Continued

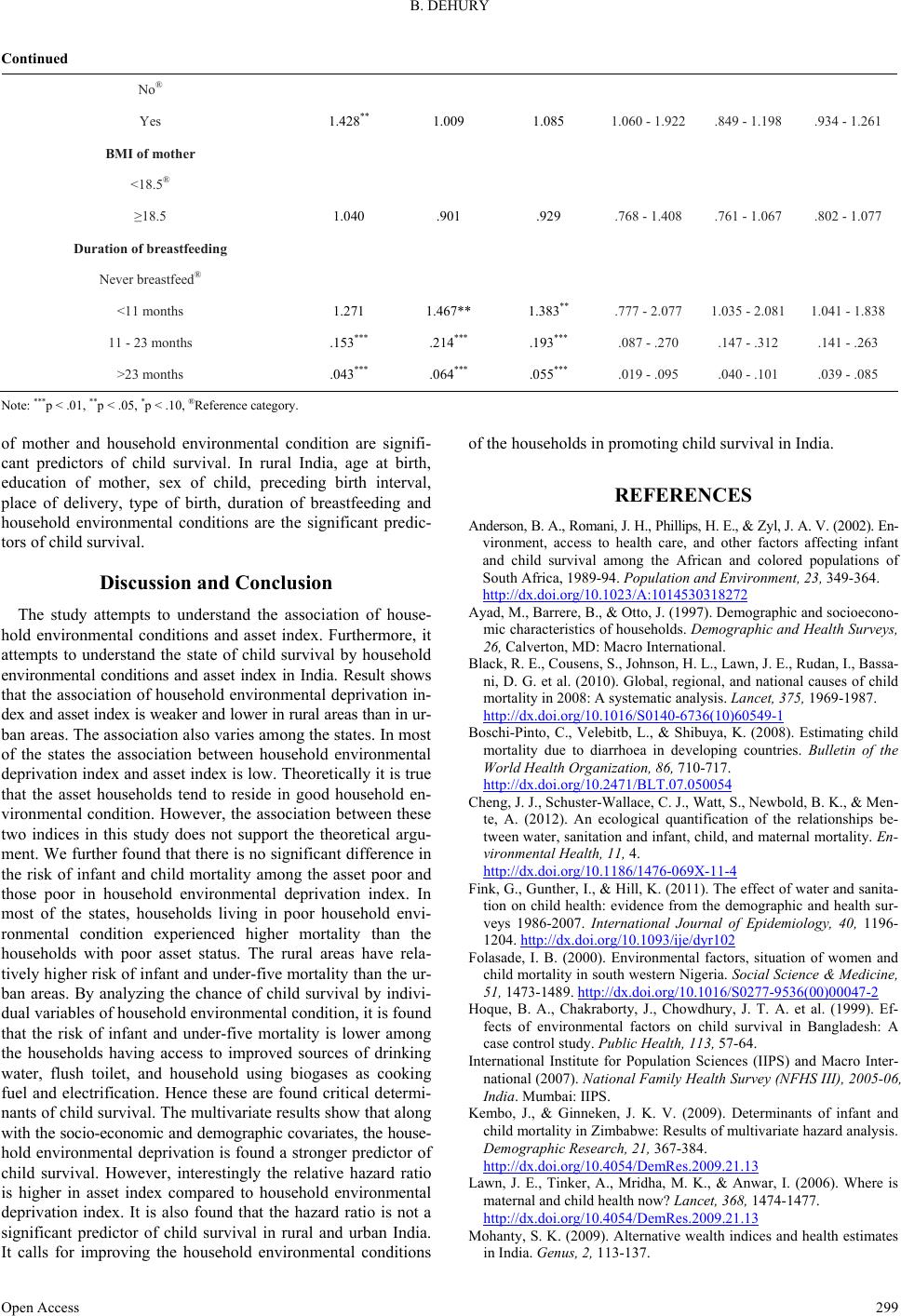

No®

Yes 1.428** 1.009 1.085 1.060 - 1.922 .849 - 1.198 .934 - 1.261

BMI of mother

<18.5®

≥18.5 1.040 .901 .929 .768 - 1.408 .761 - 1.067 .802 - 1.077

Duration of breastfeeding

Never breastfeed®

<11 months 1.271 1.467** 1.383** .777 - 2.077 1.035 - 2.081 1.041 - 1.838

11 - 23 months .153*** .214*** .193*** .087 - .270 .147 - .312 .141 - .263

>23 months .043*** .064*** .055*** .019 - .095 .040 - .101 .039 - .085

Note: ***p < .01, **p < .05, *p < .10, ®Reference category.

of mother and household environmental condition are signifi-

cant predictors of child survival. In rural India, age at birth,

education of mother, sex of child, preceding birth interval,

place of delivery, type of birth, duration of breastfeeding and

household environmental conditions are the significant predic-

tors of child survival.

Discussion and Conclusion

The study attempts to understand the association of house-

hold environmental conditions and asset index. Furthermore, it

attempts to understand the state of child survival by household

environmental conditions and asset index in India. Result shows

that the association of household environmental deprivation in-

dex and asset index is weaker and lower in rural areas than in ur-

ban areas. The association also varies among the states. In most

of the states the association between household environmental

deprivation index and asset index is low. Theoretically it is true

that the asset households tend to reside in good household en-

vironmental condition. However, the association between these

two indices in this study does not support the theoretical argu-

ment. We further found that there is no significant difference in

the risk of infant and child mortality among the asset poor and

those poor in household environmental deprivation index. In

most of the states, households living in poor household envi-

ronmental condition experienced higher mortality than the

households with poor asset status. The rural areas have rela-

tively higher risk of infant and under-five mortality than the ur-

ban areas. By analyzing the chance of child survival by indivi-

dual variables of household environmental condition, it is found

that the risk of infant and under-five mortality is lower among

the households having access to improved sources of drinking

water, flush toilet, and household using biogases as cooking

fuel and electrification. Hence these are found critical determi-

nants of child survival. The multivariate results show that along

with the socio-economic and demographic covariates, the house-

hold environmental deprivation is found a stronger predictor of

child survival. However, interestingly the relative hazard ratio

is higher in asset index compared to household environmental

deprivation index. It is also found that the hazard ratio is not a

significant predictor of child survival in rural and urban India.

It calls for improving the household environmental conditions

of the households in promoting child survival in India.

REFERENCES

Anderson, B. A., Romani, J. H., Phillips, H. E., & Zyl, J. A. V. (2002). En-

vironment, access to health care, and other factors affecting infant

and child survival among the African and colored populations of

South Africa, 1989-94. Population and E nvir on men t, 23, 349-364.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1014530318272

Ayad, M., Barrere, B., & Otto, J. (1997). Demographic and socioecono-

mic characteristics of households. Demographic and Health Surveys,

26, Calverton, MD: Macro International.

Black, R. E., Cousens, S., Johnson, H. L., Lawn, J. E., Rudan, I., Bassa-

ni, D. G. et al. (2010). Global, regional, and national causes of child

mortality in 2008: A systematic analysis. Lan ce t , 375, 1969-1987.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1

Boschi-Pinto, C., Velebitb, L., & Shibuya, K. (2008). Estimating child

mortality due to diarrhoea in developing countries. Bulletin of the

World Health Organization, 86, 710-717.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.07.050054

Cheng, J. J., Schuster-Wallace, C. J., Watt, S., Newbold, B. K., & Men-

te, A. (2012). An ecological quantification of the relationships be-

tween water, sanitation and infant, child, and maternal mortality. En-

vironmental Health, 11, 4.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-11-4

Fink, G., Gunther, I., & Hill, K. (2011). The effect of water and sanita-

tion on child health: evidence from the demographic and health sur-

veys 1986-2007. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40, 1196-

1204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr102

Folasade, I. B. (2000). Environmental factors, situation of women and

child mortality in south western Nigeria. Social Science & Medicine,

51, 1473-1489. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00047-2

Hoque, B. A., Chakraborty, J., Chowdhury, J. T. A. et al. (1999). Ef-

fects of environmental factors on child survival in Bangladesh: A

case control study. Public Health, 113, 57-64.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro Inter-

national (2007). National Family Health Survey (NFHS III), 2005-06,

India. Mumbai: IIPS.

Kembo, J., & Ginneken, J. K. V. (2009). Determinants of infant and

child mortality in Zimbabwe: Results of multivariate hazard analysis.

Demographic Research, 21, 367-384.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2009.21.13

Lawn, J. E., Tinker, A., Mridha, M. K., & Anwar, I. (2006). Where is

maternal and child health now? Lancet, 368, 1474-1477.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2009.21.13

Mohanty, S. K. (2009). Alternative wealth indices and health estimates

in India. Genus, 2, 113-137.

Open Access 299