American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 2013, 3, 595-600 Published Online November 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajibm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2013.37069 Open Access AJIBM 595 The Impact of Prevalent Destructive Leadership Behaviour on Subordinate Employees in a Firm Tran Quang Yen 1,2*, Yezhuang Tian1, Foday Pinka Sankoh1,3 1School of Management, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China; 2National Economics University, Hanoi, Vietnam; 3Portloko Teachers College, Portloko, Sierra Leone. Email: *yentq@neu.edu.vn Received August 5th, 2013; revised September 5th, 2013; accepted September 12th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Tran Quang Yen et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT This paper examines the impact of destructive leadership behaviours experienced by subordinate employees. Structured questionnaires based on the petty Tyranny in organizations scale to explore the scope and nature of destructive leader- ship were used. The study further explores the relationship among leadership experiences, various measures of subor- dinates’ satisfaction and turnover level. The results showed that despite the central role of leadership holds for many firms in Hanoi, Vietnam, subordinate employees reported experiencing toxic destructive leadership. There was a sig- nificant negative relationship among destructive leadership, all measures of satisfaction and turnover level. Surprisingly, there was not a significant negative impact on turnover level (inclination to remain in the employment) among the sub- ordinate population. Keywords: Destructive Leadership; Satisfaction; Turnover Level; Petty Tyranny; Subordinate Employee 1. Introduction 1.1. Destructive Leadership Behaviors Directed at Subordinates The concept of destructive leadership bahavior has sev- eral definitions as many researchers exist. Each of them tried to define this concept based on his orientation. A common one among them was given by this, “destructive leadership behavior refers to systematic and repeated behaviour by a leader, supervisor or manager that vio- lates the legitimate interest of the organization by un- dermining and/or sabotaging the organization’s goal, tasks, resources and effectiveness and/or the motivation, well-being or job satisfaction of subordinates.” However, any definition of this concept should consider one or all of the following: “work place bullying” [1], “verbal abuse” [2,3], “Petty tyranny” [4], “Abusive managerial behaviour or supervision” [5], “Intolerable bosses” [6], “Harassing leaders” [7], “derailed leaders”[8] and “Work place mistreatment” [9]. The success of an organization depends on the effectiveness of the leadership behaviour. If a leader has effective leadership traits and shows nega- tive leadership behaviour, this might result in negative effects on not only the organization [10] but to a large extent on his subordinates. Keashly, Trott and MacLean (1994) [11] identified two key criteria that help reinforce destructive leadership behaviors: Environments which are likely to facilitate toxic leadership, including organi- sations which are unstable with many perceived threats and a lack of checks and balances; a culture that allows a leader to develop a pattern of overt grandiosity, selffo- cus and self important behavior which is clearly exploita- tive and sometimes parasitic. Leaders are in a position of trusting and organizing resources, in effect, without su- pervision. They also tend to react more strongly to issues which are likely to have immediate effects, as opposed to those that will impact in the future. Destructive leader- ship behavior results do not just come from leaders, but also their subordinates. A destructive leadership behav- ior’s degree of selfishness will affect the subordinates, whose responses constitute a form of feedback that either moderates or worsens the destructive behavior. Blaming others for their problems is an approach that some lead- ers adopt when they lack the necessary ability to lead. They become suspicious and mistrustful of those who are bright enough to cope, and become progressively more paranoid. As this paranoia spirals out of control, their behavior turns increasingly destructive as they become *Corresponding author.  The Impact of Prevalent Destructive Leadership Behaviour on Subordinate Employees in a Firm 596 more argumentative, belligerent, hostile, secretive, stub- born and consumed by mistrust. Therefore, Burke (2006) [12] categorized these destructive behaviors into: de- luded, paranoid, sociopathic and narcissistic. The de- luded leaders are in denial about themselves, the con- straints around their work and the details of past occur- rences. The deluded leaders display destructive behaviors in their inability to make timely decisions and get things done most simply. The paranoid leader is suspicious of others, always ready to fight seeming threats and with extreme worry for concealed motives and unique mean- ings. The paranoid leader exhibits destructive behavior that is characterized by an intense attention to spin, ra- tionalized by an all-pervading mistrust of others. The sociopathic leader consistently disregards and violates other people’s rights. They exhibit destructive behavior characterized by indifference to having hurt or mistreat- ing others and a consistent lack of remorse. The narcis- sistic leader is resistant to change. They know that their way is best and they have an inability to recognize their many limitations. The narcissistic leader displays de- structive behavior that is characterized by a lack of ca- pacity to learn from others or experience, and a refusal to take accountability or responsibility. Capable leaders differ widely in their personalities, strengths, weaknesses, values and beliefs, but they all have one thing in com- mon—they get the right things done. In large parts, lead- ers with destructive leadership behaviors believe they are special and entitled to more positive outcomes in life than others, so that they are more intelligent than they actually are, and they are better in their exertion of power and dominance than others. 1.2. Effects of Destructive Leadership It depends on the leader’s level in an organizational hier- archy; lower ranking leaders have fewer malevolent op- tions than senior leaders. Think of leaders as existing in three levels: 1) First line; 2) Middle; 3) Senior. First line supervisors destroy their teams almost exclusively through their behavior. There is a reasonably well de- fined taxonomy of bad managerial behavior captured by our dark side measure of personality [13]; these behav- iors include: bullying, harassing, exploiting, lying, be- traying, manipulating-in short, denying subordinates their basic humanity. These behaviors alienate the subordi- nates, who in response, engage in a wide range of passive and aggressive behaviors that undermine the perform- ance of the team. They also retaliate actively with law suits and, at times, direct violence. Destructive leaders at the second or middle level have at their disposal the full range of behavioral options just described. In addition, they can destroy their teams by making bad tactical deci- sions which are, through exercising bad judgment. The scope of the damage created by bad tactical decisions is relatively limited, for example a mid-level manager routinely overspends the budget. Senior leaders have much greater discretion to act destructively [14]. They can avail themselves of the full range of behavioral op- tions described above-bullying, exploitation, harassment, etc. In addition, like mid-managers, they are empowered to make bad tactical decisions. But it is at the level of strategic decision making that senior managers can be most destructive, and in ways that vastly exceed the ca- pacity of lower level managers. The big reason most people behave badly is that they are self-centered; they are preoccupied with their own agendas, and unable or unwilling to consider how their actions might affect oth- ers [15]. These self-centered focus behaviors are caused by insecurity and arrogance [16]. People who are inse- cure lack of confidence and are primarily concerned with their own psychic survival; they live in a nearly constant state of panic, and react emotionally to real and imagi- nary perceived threats. If a subordinate makes a mistake, it may reflect badly on the “leader”, who then reacts an- grily and disproportionately to the subordinate’s mistake. When confronted with data indicating that they have made bad decisions, they explode and blame the mistake on external factors [17]. Leaders who are arrogant have too much confidence, and see others (and especially sub- ordinates) as objects to be used for their own purposes. Arrogant leaders feel entitled to exploit and abuse their subordinates because the subordinates are existentially unworthy. They are like farm animals that can be slaughtered for an evening meal. When confronted with data indicating that they have made bad decisions, they typically ignore the feedback and say that it is time “to move on” [18]. In this paper, we begin an exploration of destructive leadership as experienced by senior and mid- dle ranked employees in an effort to obtain some quanti- tative data about the extent of the phenomenon in a lim- ited, yet important, population. Various demographic groups would be examined to determine whether experi- ence with negative leadership behaviour varies across such groups. The article then describes the fifteen most frequently experienced negative behaviours before turn- ing to the relationship among destructive leadership, subordinate satisfaction and turnover level. Because of prior focus group research [17], we developed two spe- cific hypotheses for testing. Hypothesis 1: An increased level of contact with nega- tive leadership behaviours will negatively affect subor- dinates job satisfaction level. Hypothesis 2: An increased level of contact with nega- tive leadership behaviours will negatively affect subo- rdinates turnover level. 2. Methods 2.1 Sample This study administered structured questionnaires based Open Access AJIBM  The Impact of Prevalent Destructive Leadership Behaviour on Subordinate Employees in a Firm 597 on Ashforth’s Petty Tyranny in Organizations Scale as the primary measure of destructive leadership [4]. The questionnaires were administered to 400 employees from 20 enterprises in Hanoi, Vietnam. These 20 enterprises were the most highly developed enterprises with many employees in Hanoi. Only employees with potential for greater levels of responsibility and thought that they were treated fairly by their management were selected for the survey. How ever, there are those in this study that have an axe to grind due to perceptions of institutional mal- treatment. 2.2. Survey Instrument The questionnaire addressed demographics (race, gender, service component, pay grade, and years of service), sat- isfaction with various aspects of the job and relationships with others, turnover level (inclination to remain in the job), and specific positive and negative behaviors ex- perienced in the enterprises. The Petty Tyranny in Or- ganizations Scale was originally designed to explore as- pects of ineffective leadership along six dimensions: ar- bitrariness and self aggrandizement, belittling subordi- nates, lack of consideration, a forcing style of conflict resolution, discouraging initiative, and non-contingent punishment. Ashforth (1994) [4] reported that the mean correlation between dimensions was 0.58 (p < 0.001), and inter-rater reliability was r = 0.52, which was com- parable to other measures of leadership. His description of the petty tyrant fits the general description of toxic leaders obtained from other qualitative researches. “They are unconcerned about, or oblivious to subordinates’ morale and/or climate. They are seen by the majority of subordinates as arrogant, self-serving, inflexible, and petty” [17]. The questionnaire consist of forty-five ques- tions which compose the Petty Tyranny in Organizations Scale addressed specific behaviors over a delimited time frame such as, “how often were you in circumstances where a superior belittled or embarrassed subordinates?” Participants indicated frequency of experience by select- ing from five options ranging from very seldom to very often. A number of questions were reverse-coded to ex- press positive leadership behaviors such as, “encouraged subordinates to speak up when they disagreed with a de- cision.” The use of this scale resulted in a measure of destructive leadership that provided a continuous vari- able that ranged from 50 to 400, suitable for a variety of common statistical analyses. Demographics were in- cluded to determine whether the phenomenon of destruc- tive leadership varies by group membership. Of particu- lar interest was the degree to which experience with de- structive leadership varies by race, gender, and branch of service. The eight questions about satisfaction served as an impact variable. They asked participants to indicate their levels of satisfaction on a 5-point Likert type scale ranging from very dissatisfied to very satisfied. The questionnaire also asked respondents to indicate whether they had experience with multi-rater feedback tools and asked them to indicate their level of satisfaction with 360-degree assessment instruments. Of specific interest was the level of satisfaction with direction and supervi- sion received and relationships with coworkers and peers, superiors, and subordinates as well as overall satisfaction with the work that they did and their job as a whole. As another form of impact variable, participants were asked to suppose that they needed to decide whether to remain in the service or not. Assuming that they could remain, and they were under no service obligation and eligible for retirement, they were asked to indicate the likelihood that they would remain in service on a 5-point scale (very unlikely to very likely). We asked respondents to indicate whether they seriously considered leaving their enter- prises because of the way they were treated by a super- visor. A series of follow-up questions about the supervi- sor and situation were included in an effort to identify particularly problematic or frequent behaviors that caused the respondent to consider leaving the job. 2.3. Data Analysis We used both descriptive and inferential statistics to analyze the data and test hypotheses including percent- ages, analysis of variance, correlation, and regression. The scale data were ordinal, yet we treated them as con- tinuous for the purpose of our analysis because the Petty Tyranny in Organizations Scale and Satisfaction Scale produce quantitative discrete ordinal variables with a sufficiently wide range of values [19]. Most of the demo- graphics were categorical. We used analysis of variance to determine if experiences with destructive leadership varied by demographic categories. Correlations were used to determine the significance of associations be- tween destructive leadership and satisfaction and turn- over level (inclination to remain in the job). Regression analyses were used to identify the impact of destructive leadership on subordinates’ satisfaction and turnover level (inclination to remain in the job). 3. Results and Discussion 3.1. Demographics Of those who participated in the study, 80 percent were male and 20 percent were female. Most of the respon- dents were middle level employees (89 percent), but 11 percent were senior level workforce. All respondents were in the grades of O5 (middle level 48 percent), O6 (senior level, 5 percent), and GS-14 (lower level, 47 per- cent), and Time in service ranged from five years (2 per- cent) to more than Twenty years (15 percent) with a mode of twelve years (21 percent). Whites (Vietnamese) Open Access AJIBM  The Impact of Prevalent Destructive Leadership Behaviour on Subordinate Employees in a Firm 598 constituted 89 percent of respondents, whites (non-Viet- namese) 7 percent, and 3 percent Africans. 3.2. Experiences with Destructive Leadership All respondents indicated some experience with destruc- tive leadership behaviors. When asked whether they se- riously considered leaving their employment due to treatment at the hands of a superior, 274 (68.4 percent) answered yes. Of those, when asked how long ago the incident occurred that caused them to consider leaving, 17.7 percent indicated that it occurred recently (less than one year ago), 32.3 percent said that the incident oc- curred one to three years prior, 13.5 percent indicated three to five years prior, and 36.5 percent pointed to an incident that occurred more than five years ago. Analysis of the Petty Tyranny in Organizations Scale indicated insignificant differences with regard to experiences with destructive leadership on the basis of gender, branch of employment, and race. Senior level respondents reported experiencing less destructive leadership (M = 116.2, SD = 45) than did their middle level counterparts (M = 147.6, SD = 52.7) and lower level counterparts (M = 113.4, SD = 45). The difference between components were signifi- cant (F = 7.503, p = 0.007). Also, senior level respon- dents reported experiencing less destructive leadership (M = 113.4, SD = 45) than did those in the lower level (M = 134, SD = 43.2). The differences between compo- nents were significant (F = 3.93, p = 0.010). Similarly, middle level respondents in O5 grade experienced more destructive leadership from superiors (M = 119.5, SD = 45.2) than did senior level at the grade of O6 (M = 113.3, SD = 44.9). Also, lower level respondents in the grade of GS-14 experienced more destructive leadership (M = 153.5, SD = 52.2) than did those in the grade of 05 (M = 142.8, SD = 55.4). Differences by pay grade were sig- nificant (F = 2.790, p = 0.042); however, post hoc testing indicates that most of the variance in pay grade is ac- counted for by the difference between the different levels of employment. Table 1 shows the most frequently ex- perienced negative leadership behaviors. The list reflects most of constructs that Ashforth suggested were part of petty tyranny in organizations with one notable exception. There were few responses indicating a problem with non-contingent punishment. 3.3. Satisfaction Our indicators of satisfaction consisted of eight Likert- type 5-point questions ranging from very dissatisfied (1) to very satisfied (5). Three of the questions addressed the level of satisfaction with relationships such as with co- workers, supervisors, and subordinates. They were also asked to indicate satisfaction with pay and benefits as well as promotion opportunities. One question asked how satisfied they were with the kind of direction they received from superiors, and there were two general questions relating to satisfaction. One addressed satisfac- tion with the kind of work they do, and another asked how satisfied they were with their job as a whole. As one would expect, this group of senior level employees indi- cated a generally high satisfaction level. As indicated in Table 2, the lowest levels of satisfaction were with the kind of direction they received from superiors, pay and benefits, and relationships with supervisors. By combin- ing the numerical values of the questions relating to sat- isfaction, we obtained a numerical scale that reflects a combined measure of satisfaction level. Chronbach’s alpha is a statistical test that measures the degree of in- Table 1. Top fifteen most frequently experienced negative leadership behaviours. Behavior Mean Standard deviation Played favorites 2.42 1.23 Relied on authority 2.32 1.11 Imposed his or her solution 2.23 1.24 Guarded turf against outsiders 2.23 1.25 Lost temper 2.12 1.02 Insisted on one solution 2.02 1.17 Administered policies unfairly 2.00 1.05 Forced acceptance of his or her point of view 1.98 1.19 Would not take no for an answer 1.98 1.23 Treated subordinates in condescending manner 1.97 1.16 Demanded to get his or her way 1.92 1.16 Show off, bragged or boasted 1.89 1.13 Criticized subordinates in front of others 1.89 1.09 Delegated work he or she did not want 1.84 1.05 Claimed credit for the work of others 1.77 1.10 Note: N = 400. Table 2. Areas of satisfaction. Question MeanSD How satisfied with subordinate relationships? 4.45 0.634 How satisfied with co worker relationships? 4.41 0.571 How satisfied with the job as a whole? 4.21 0.719 How satisfied with the work you do? 4.21 0.774 How satisfied with promotion opportunities? 4.10 0.883 How satisfied with supervisor relationship? 4.03 0.914 How satisfied with pay/benefits? 3.97 0.741 How satisfied with the recerved direction form superiors? 3.83 0.912 Note: N = 400; SD = Standard deviation. Open Access AJIBM  The Impact of Prevalent Destructive Leadership Behaviour on Subordinate Employees in a Firm 599 ternal consistency or, in other words, how well a number of items represent a single construct. The Satisfaction Scale showed a high degree of internal consistency with a Chronbach’s alpha of 0.805. The question relating to satisfaction with direction of superiors was removed from the scale because of excessive inter-item correlation with the question about satisfaction with supervisor rela- tionships. Only 5 of the 400 respondents indicated that it was highly unlikely that he or she would remain in the job. Surprisingly, 43.2 percent said that they were not inclined to remain, and 10.9 percent indicated a neutral opinion on the question. Most, however, said that it was likely that they would not remain in the employment (N = 252, 63 percent), while 148 (37 percent) indicated it was very likely they would remain in the employment. 3.4. Relationships between Experience with Destructive Leadership, Satisfaction, and Turnover Level (Inclination to Remain in the Job) To examine the relationship between experience with destructive leadership and satisfaction, a series of simple linear regressions were performed that indicated destruc- tive leadership was significantly correlated with all the satisfaction variables. A linear regression was also per- formed using the results of the Petty Tyranny in Organi- zations Scale as the independent variable and the Satis- faction Scale as the dependent variable. The results dis- played in Table 3 indicate that experience with destruc- tive leadership was a significant predictor of dissatisfac- tion. Table 4 indicates that the leadership style experi- enced remained a significant predictor of satisfaction even after component status (active service) and pay grade were added to the model. Collinearity diagnostics confirmed that fit of the model was not affected by multi- collinearity. Based on these findings, we can state that there is sufficient evidence to suggest that an increased level of contact with negative leadership behaviors will negatively affect middle level workers’ job satisfaction (hypothesis 1). We then conducted a logistic regression that examined the relationship between several inde- pendent variables (active status, pay grade, and destruct- tive leadership) and inclination to remain in the job as the dependent variable (Table 5). This analysis indicates that there is insufficient evidence to accept hypothesis 2. There is insufficient evidence to suggest that an in- creased level of contact with negative leadership behave- iors will negatively affect the inclination of middle level employees to remain in the job. 4. Conclusion As anticipated, we found that members of this population reported experience with a range of leadership styles and Table 3. Regression indicating the relationship of destruc- tive leadership experience (petty tyranny) to satisfaction level. Variable RC SE SC P Petty tyranny−0.034 0.691 −0.439 0.000 Constant 33.48 Note: N = 400; R2 = 0.192; RC = Regression coefficient (Not standardized); SE = Standard Error; SC = Standardized Coefficient; p = probability. Table 4. Regression indicating the relationship of destruc- tive leadership experience (petty tyranny), component sta- tus, and pay grade to satisfaction level. Variable RC SE SC P Petty tyranny −0.034 0.006 −0.437 0.000 Component statues 0.34 0.828 0.031 0.682 Pay grade 0.473 0.521 0.068 0.365 Constant 31.856 Note: N = 400; R2 = 0.196; RC = Regression coefficient (Not standardized); SE = Standard Error; SC = Standardized Coefficient; p = probability. Table 5. Logistic regression of destructive leadership ex- perience, component status, and pay grade as a predictor of likelihood to remain in service. VariableRC SE W P EOR CI Petty tyranny0.0050.0060.819 0.366 1.005 0.994 - 1.016 Component statues −0.8751.0830.652 0.419 0.417 0.050 - 3.482 Pay grade−0.2160.5560.151 0.698 0.806 0.271 - 2.398 Constant −1.830 Note: N = 400; RC = Regression coefficient (Not standardized); SE = Stan- dard Error; W = Wald; OER = Estimated Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Intervals (odds); p = probability. behaviors. They were no strangers to destructive leader- ship styles, and all experienced at least some of the nega- tive behaviors included in Ashforth’s Petty Tyranny in Organization scale. Because employees at the senior lev- el reported less destructive behaviour than the middle level employees, and because employees in the middle level experienced less destructive behaviour than the lower level employees, there is some support for the as- sertion of an inverse relationship between destructive leadership and job position. In terms of the type of de- structive leadership that was most frequently experienced by employees, we saw the evidence of many, but not all, of Ashforth’s six dimensions of petty tyranny: arbitrari- ness and self-aggrandizement, belittling subordinates, lack of consideration, a forcing style of conflict resolu- tion, discouraging initiative, and noncontingent punish- ment. Although we expected that experience with de- Open Access AJIBM  The Impact of Prevalent Destructive Leadership Behaviour on Subordinate Employees in a Firm Open Access AJIBM 600 structive leadership would negatively impact inclination to remain in the service, we were unable to find support for this hypothesis. This study examined the impact of destructive leadership in a narrow sense. Our impact va- riables were limited to satisfaction and turnover level (inclination to remain in the services of the employer). Therefore, there is a need for additional research to deter- mine if there are other negative impacts of destructive leadership. REFERENCES [1] G. Namie, R. Namie, and P. Lutgen-Sandvik, “Challeng- ing Workplace Bullying in the United States: An Activist and Public Communication Approach,” In: S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf and C. L. Cooper, Eds., Bullying and Har- assment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Re- search, and Practice, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2010, pp. 447-467. http://dx.doi.org/10.1201/EBK1439804896-25 [2] I. I. Rosovsky, “Leadership and the Abuse of Power,” In: M. F. R. Kets de Vries, Ed., Leaders, Fools, and Impos- tors: Essays on the Psychology of Leadership, Jossey- Bass, San Francisco, 1993, p. 143. [3] H. A. Hornstein, “Brutal Bosses and Their Prey,” 1996, Riverhead books, New York. [4] B. Ashforth, “Petty Tyranny in Organizations,” Human Relations, Vol. 47, No. 7, 1994, pp. 755-778. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/001872679404700701 [5] E. Bassman, “Abuse in the Workplace,” Management Remedies and Bottom Line Impact, 1992. [6] M. M. Lombardo and M. W. McCall, “Coping with an In- tolerable Boss”, Center for Creative Leadership Special Report, Greensboro, 1984, [7] C. M. Brodsky, “The harasSed Worker,” DC Heath & Co., 1976. [8] V. Shackleton, “Leaders Who Derail,” Business Leader- ship, 1995, pp. 89-100. [9] J. Blase, and J. Blase, “The Dark Side of Leadership: Teacher Perspectives of Principal Mistreatment,” Educa- tional Administration Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 5, 2002, pp. 671-727. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0013161X02239643 [10] B. J. Tepper, “Consequences of Abusive Supervision,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 43, No. 2, 2000, pp. 178-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1556375 [11] L. Keashly, et al., “Conflict, Conflict Resolution, and Bullying,” In: S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf and C. L. Cooper, Eds., Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2011, pp. 423-445. [12] C. S. Burke, et al., “Understanding Team Adaptation: A Conceptual Analysis and Model,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 91, No. 6, 2006, p. 1189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1189 [13] R. Hogan, “Hogan Development Survey Manual,” Hogan Assessment Systems, 2009. [14] R. B. Kaiser, R. Hogan and S. B. Craig, “Leadership and the Fate of organizations,” American Psychologist, Vol. 63, No. 2, 2008, p. 96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.2.96 [15] S. Kile, “Helsefarleg Leierskap (Health Endangering Leadership),” Universitetet I Bergen, Bergen, 1990. [16] J. A. Conger and R. Kanungo, “A Behavioral Attribute Measure of Charismatic Leadership in Organizations”, Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, San Francisco, 1990. [17] C. Bullis and G. Reed, “Assessing Leaders to Establish and Maintain Positive Command Climate”, A Report to the Secretary of the Army, 2003. [18] J. Lipman-Blumen, “Toxic Leadership,” 2010. [19] W. D. Berry, “Understanding Regression Assumptions,” Vol. 92, SAGE Publications, New York, 1993.

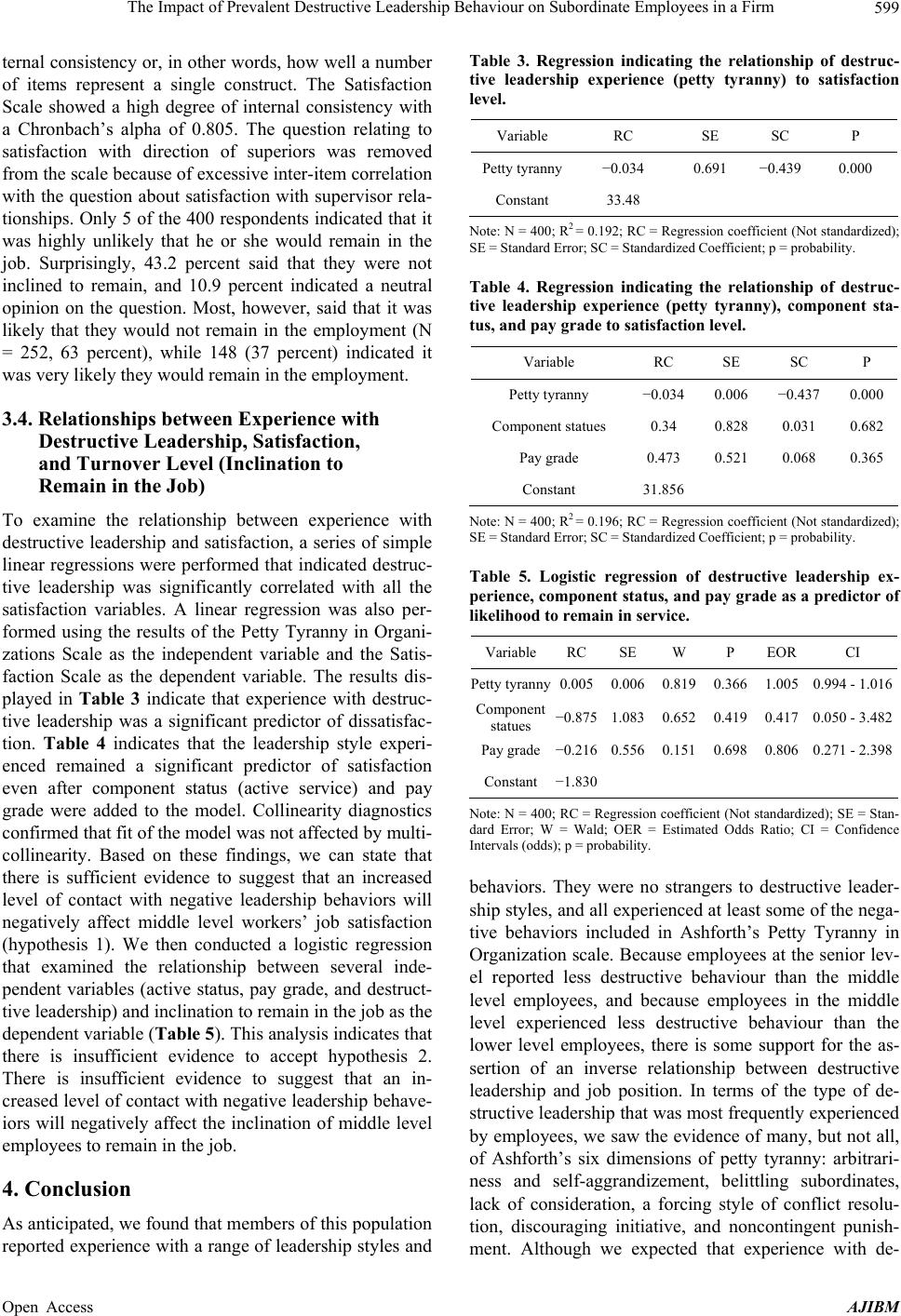

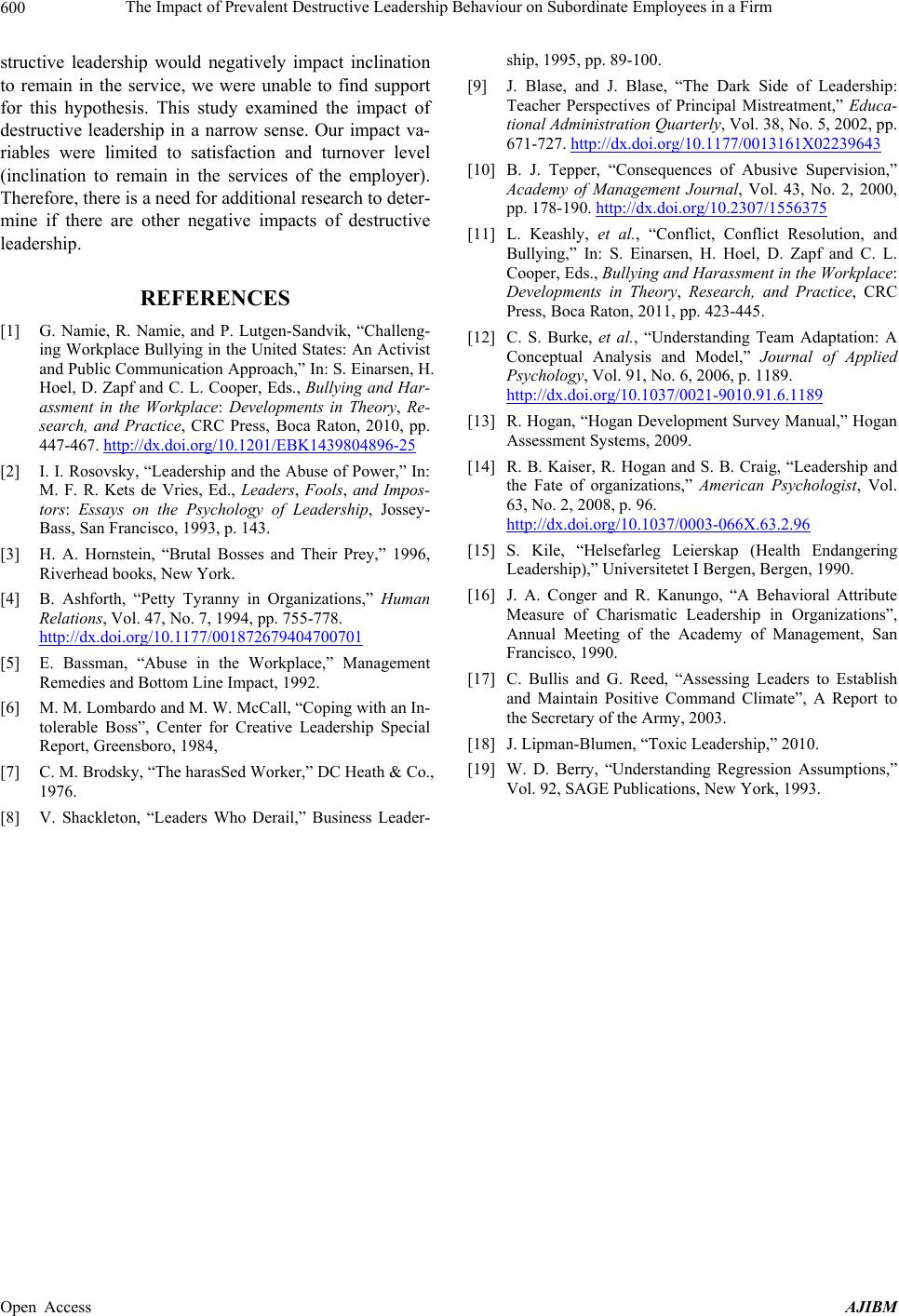

|