Psychology 2011. Vol. 2, No. 1, 53-59 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.21009 Attention Problems and Learning Disabilities in Young Offenders in Detention in Greece Katerina Maniadaki1, Efthymios Kakouros2 1Department of Social Work, TE I of Athens, Athens, Gr eece; 2Department of Early Childhood Education, TEI of Athens, Athens, Greece. Email: katerina@arsi.gr Received June 22nd, 2010; revised December 10th, 2010; accepted December 13th, 2010. Background: The relationship between learning disabilities and juvenile delinquency is widely established. However, the nature of learning disabilities and the pathway through which they are linked to delinquency are not well understood yet. The contribution of third variables, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) seems as a promising field of research. The primary aim of this study was to investigate the schooling history of young offenders detained in Greek Correctional Centers in order to examine the extent to which learning disabilities may co-exist with psychosocial adversity and/or specific learning disabilities, in particular, attention problems. Method: The Greek version of the Youth Self Report (YSR), the Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC) and a questionnaire constructed by the authors were used in the study. Results: Schooling his- tory of the young offenders was characterized by low attendance, high levels of dropouts, grade retention and academic failure. High co-existence of both psychosocial adversity and attention problems, indicating possible presence of ADHD, was found as well. Conclusions: These findings underline the need for routine ADHD screening at schools for the identification and treatment of those children who are at particular risk to get in- volved in criminal activities. Moreover, the need for the identification of incarcerated youth with ADHD and/or learning disabilities as well as prison staff training are discussed. Keywords: Juvenile Offenders, ADHD, Juvenile Delinquency, Learning Disabilities, Gree ce Introduction There is a general agreement that juvenile delinquency may be better understood within a developmental psychopathology framework, wherein a paucity of protective factors and an ac- cumulation of risk factors during adolescence result in psycho- logical and behavioral disruption (Steiner, Williams, Ben- ton-Hardy, Kohler, & Duxbury, 1997). In addition, adult crimi- nal activity is often the result of a developmental progression from childhood conduct problems to later offending (Babinski, Hartsough & Lambert, 1999). Based on such evidence, Pajer (1998) suggested that the relationship between delinquent be- haviour among boys and criminal behaviour among men is an excellent example of “homotypic continuity”, meaning that there is a strong correlation between a disorder at one develop- mental stage and the same symptoms in the same or a similar disorder at a further developmental stage. Therefore, early identification of the factors that predispose some children for later persistent criminal involvement would provide a target group for prevention efforts in early childhood. Among multiple types of risk factors, learning disabilities are closely related to the likelihood of an adolescent becoming involved in the juvenile justice system (Maniadaki, Kakouros, & Karaba, 2009; Maniadaki, Kakouros, & Karaba, 2010; Shelley-Tremblay, O’Brien & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2007). Although the prevalence rate of learning disabilities among de- linquent youth varies from study to study according to different definitions of what constitutes a learning disability, evidence accumulates that this rate is disproportionate as compared to the general school-aged population (Skaret & Wilgosh, 198 9; Sno w- ling, Adams, Bowyer-Crane & Tobin, 2000). A broad definition of learning disabilities refers to a discrepancy between student performance and his/her academic age–or expected grade-level. In this sense, the U.S. Government General Accounting Office study found that nearly 100% of 129 randomly selected delin- quents from U.S. institutions had learning problems (Skaret & Wilgosh, 1989). More conservative estimates are given in a meta-analysis by Casey & Keilitz (1990) who reported that 35.6% of juvenile offenders were learning disabled and 12.6% were mentally retarded. These figures are three to five times higher than the percentage of students labelled as disabled in public schools (Leone & Meisel, 1997). These high prevalence estimates have raised the question about whether learning disabilities are contributing to juvenile delinquency and in what ways. Regarding the latter, a pertinent issue is the nature of the learning disabilities which frequently co-occur with delinquent behavior (Snowling, Adams, Bow- yer-Crane, & Tobin, 2000). In particular, it is important to establish the extent to which academic under-attainment can be explained in terms of environmental factors, such as psychoso- cial adversity or is associated with biological factors, such as a specific learning disorder. The first case concerns, for example, dysfunctional families where low educational and socio-economic level might co-exist with problems like poor parenting or a history of offending in parents themselves. A child growing up in such a family has usually limited opportunities to systematically attend school, displays low academic motivation and reduced effort to meet school demands. Each one of these factors alone - and in combination as well - may lead to discrepancy between a  K. MANIADAKI & E. KAKOUROS 54 child’s performance at school and his/her academic age level, and, in turn, to the development of learning disabilities. Consequently, children and adolescents showing little interest in school and minimal involvement in school-related activities are more likely to engage in later violent behaviour (Bonny, Britto, Klostermann, Hornung, & Slap, 2000). Furthermore, incomplete schooling is often associated with disadvantages in the job market, which together with pre-existing conduct prob- lems may increase the risk of subsequent delinquent involve- ment (Bonny et al., 2000). The second case refers to the presence of neuropsychological deficits in the child, which interfere with learning abilities. Until recently, the majority of studies considering the relation- ship between specific learning disabilities and delinquency examined isolated learning domai ns, focusing mainly on sp eci fi c reading disabilities. Gellert and Elbro (1999) cite a number of studies pointing out a high occurrence of reading disabilities among juvenile delinquents. In a study by Meltzer, Levine, Karniski, Palfrey & Clarke (1984), it is reported that, by second grade, 45% of the delinquents were delayed in reading and 36% in writing. In a review by Snowling et al. (2000), 44% of 91 juvenile offenders was found to have specific reading difficult- ties. However, such epidemiological findings do not provide evidence for a direct role of reading disability in the genesis of antisocial behaviour and fail to shed light in the pathways through which specific learning disabilities may lead to delin- quency (Fergusson & Lynsky, 1997; Williams & McGee, 1994). As a result, the study of third variables, which may underlie both learning disabilities and delinquency, appears as a prom- ising research field. One factor that is emerging as a potentially important cor- relate of both learning disabilities and delinquent behaviour is the presence of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Pratt, Cullen, Blevins, Daigle, & Unnever, 2002). ADHD is associated with neuropsychological deficits, poor academic and cognitive skills, impulsivity, defiance and aggression (Barkley, 1998; Brown, Freeman, Perrin, Stein, Amler, Feldman et al., 2001). The combination of the above, coupled with negative parental and teacher responses, predisposes a child with ADHD both to the development of conduct problems and academic failure (Jorm, Share, Matthews & MacLean, 1986). Truancy may evolve as a result, which increases the likelihood of the child initiating delinquent acts. In other words, it seems possible that, on the one hand, cognitive deficits associated with ADHD may cause specific learning disabilities and school failure, which, in turn, facilitates delinquency. On the other hand, behavioural correlates of ADHD like impulsive behaviour, low threshold for emotional aro usa l and l o w s e l f-c o n t r o l may d i rec t l y facilitate both academic failure and delinquency (Goldstein, 1997). Thus, ADHD may lead to delinquency through both an indirect and a direct pathway. Epidemiologic studies provide support for the above scena- rios. Research has revealed that children with ADHD are at high risk of embarking on a criminal career (Langhinrichsen- Rohling, Rebholz, O’Brien, O’Farrill-Swails, & Ford, 2005; Mannuza, Gittelman-Klein, Bessler, Malloy & LaPadula, 1993; Moffitt, 1990). In a longitudinal study conducted in Greece with a sample of 41 children diagnosed with ADHD at school- age, it was found that 75% of those who still met the criteria of ADHD at adolescence had also developed Conduct Disorder and had some kind of involvement with justice (Kakouros, 1998). On the other hand, Otto, Greenstein, Johnson & Fried- man (1992) identified between 19% and 46% of youth in the juvenile justice system as having ADHD. Finally, the comor- bidity rate of ADHD with Oppositional Defiant Disorder and with Conduct Disorder, which, almost by definition, overlap with criminal offences, is 20% - 67% and 20% - 56% respec- tively (Barkley, 1998). Therefore, as Pratt et al. (2002) point out, to the extent that ADHD is a consistent predictor of youthful misconduct, its role in crime causation warrants fur- ther investigation and integration into extant theoretical ex- planations. Within this framework, the primary aim of this study was to investigate the schooling hi story of ninety-three young of fen ders in order to delineate the extent to which possible learning diffi- culties of the participants may co-exist with psychosocial ad- versity and/or specific learning disabilities, in particular, at- tention problems. Additionally, we sought to examine the par- ticipants’ self-perceptions regarding their academic competence and their relationships with their parents. We expected to find poor schooling history in the majority of the participants, low perceived academic competence, problematic behaviour with parents and higher percentages of attention problems compared to the general same-age population. Method Participants Participants in this study were ninety-three males, aged 13- 24 years, (mean age = 19.29; sd = 2.83) recruited at random from three Correctional Centers in Greece, described below (Ministry of Justice, 2003). It should be noted that these are the only correctional centers for minors in Greece. 1) Volos Education Institution for Male Minors. This insti- tution has a capacity of 25 detainees, who are normally aged between 8 and 18 years of age and have been sub- jected to the reformative measure of placement to an education facility. Thirteen participants (14%) were re- cruited from this setting. 2) Special Juvenile Detention Facility for Males in Avlonas. This institution has a capacity of 280 detainees. Thirty- one participants (33.3%) were recruited from this setting. 3) Special Juvenile Detention Facility of Kassavetia. This institution has a capacity of 308 detainees. Forty-nine participants (52.7%) were recruited from this setting. Detention in the last two institutions can be imposed on youths between 8 to 18 years when the Juvenile Court consid- ers that a penal sanction is necessary to deter them from re- offending. However, young adults are also held in the above facilities if they have committed an offence before the age of 18 and are tried afterwards, due to administrative delays, or if they need to complete the vocational program they attend (Ministry of Justice, 2003; Spinellis & Tsitsoura, 2006). Measures Three questionnaires were used in the present study: 1) A questionnaire constructed by the authors, in order to obtain information about demographic and family char- acteristics, a n d youth’s schooling history. 2) The Greek version of the Youth Self Report (YSR;  K. MANIADAKI & E. KAKOUROS 55 Achenbach, 1991), as translated and standardized by Roussos, Francis, Zoubou, Kiprianos, Prokopiou & Richardson (2001). The YSR is a self-report question- naire for subjects aged 11-18 years for the assessment of adolescent competencies and behaviour problems. The response format for the 112 items is 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true. The YSR can be scored on a total problem score and on eight syndrome scales. Only data from the ‘Attention Problems’ scale will be reported here as the rest has been reported in detail elsewhere (Kakouros & Maniadaki, 2007; Maniadaki & Kakouros, 2008). The participants exceeding the 18th year of age were asked to complete the Young Adult Self-Report (YASR; Achenbach, 1997), which is the equivalent of the YSR for subjects aged 18-30 years. The reliability of the YSR is strongly sup- ported by a great number of international studies. (c.f. Ivarsson, Gillberg, Arvidsson & Broberg, 2002, for a comprehensive list). 3) The Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC; Harter, 1985), as adapted by Makri-Botsari and Robinson (1991) for use with Greek students. This scale contains nine separate subscales measuring eight specific domains of self-perception, as well as global self-esteem. Two sub- scales were used in the present study, regarding: a) scho- lastic competence and b) relationship with parents. Each subscale consists of five questions, which are written in a “structural alternative format” designed to reduce the tendency to give socially desirable responses. Items are scored 4, 3, 2, or 1, where a score of 4 represents the highest self-perception and 1 represents the lowest self- perception. The scale has good psychometric properties, as reported in a great number of studies (G ranl eese & J o- seph, 1994; Muris, Meesters & Fijen, 2003). Procedure Permission to carry out the investigation was granted by the Ministry of Justice. The details of the procedure for the collec- tion of the data were determined by the Social Service of each institution. The participants were assured about confidentiality and were informed about the aims of the study. The main crite- ria for inclusion in the study were: 1) consent to participate, and 2) a good understanding of the Greek language. The first ques- tionnaire was completed jointly by each participant and the social worker of each institution. The YSR and the SPPC were completed by the participants themselves, on an individual basis, in the presence of one of the researchers and the teacher or the social worker who read aloud and explained the ques- tions, whenever needed. Results Demographic and Family Chara cte ri stics The majority (72%) of the participants were Greeks and the remaining 28% were immigrants, half of which Albanians. Most of the participants (60.2%) came from fairly large fami- lies, with at least four children. Fifty seven percent of the par- ticipants’ mothers and 60.4% of fathers were totally illiterate or of very low educational level. The family’s economic situation was very bad for more than one third of the families (37.7%). In the 39.9% of cases, offending history of another member of the family had also been reported. Schooling History Inspection of Table 1 suggests that half of the participants had dropped out school while at primary school, one third had never attended school and one third had finished either the pri- mary school or the high school. In addition, almost half of those who attended school had repeated class once or more. Furthermore, it has been found that almost half of the parti- cipants (43.9%) had not been attending school systematically although the majority (60.9%) believed that they had their fam- ily’s support to do so. Attention Problems and Perceived Competence The percentages of participants scoring in the normal, bor- derline or abnormal range on the scale “Attention problems” of the YSR and in the high, normal or low range on the two SPPC scales are reported in Table 2. As indicated in the data, 25.8% of the participants fell at the abnormal band of the “Attention problems” scale and 18.3% at the borderline band, thus indi- cating a clearly higher prevalence of such problems in our sam- ple compared to the general population of same-age counter- parts. It is of importance to notice that, despite the above find- ing, only one of the participants had ever been referred to a special class during his schooling trajectory. Furthermore, it has been found that 40.9% of the participants had low perceived scholastic competence and 39.4% had low perceived compe- tence regarding their ability to effectively communicate with their parents. Finally, when perceived competence of the participants in the basic academic domains was examined, it was found that above 60% reported that, while in school, they performed bad or very bad in reading, writing and maths, with reading receiving the lowest ratings (Table 3). Table 1. Schooling trajectory and g r ad e r e t ention rates (percentages). Schooling trajectory Grade retention Finished primary school 12.9 Never 54.5 Finished high sch oo l 7.6 Once 22.7 Dropped ou t at primary sc hool 50.5 Twice 7.6 Never attended school 29 Three times 15.2 Total 100 Total 100 Table 2. Ratings (%) on the YSR ans the SPPC Scales. YSR Scale NormalBorderline Abnormal Total Attention problems 55.9 18.3 25.8 100 SPPC scales High Normal Low Total Scholastic competence 2.2 56.9 40.9 100 Relationship with parents 2.8 57.8 39.4 100  K. MANIADAKI & E. KAKOUROS 56 Table 3. Perceived performance (%) on the basic academic domains. Academic domain Perceived performance Very good/ good Average Bad/ very bad Total Reading 4.3 22.8 72.9 100 Writing 10.3 29.4 60.3 100 Mathematics 8.7 30.2 61.1 100 Discussion The primary aim of this study was to collect data regarding the schooling history of young people within the juvenile jus- tice system in Greece and to investigate the possible presence of specific learning disabilities, in specific, attention problems. The results showed that the schooling history of the young offenders was characterized by low attendance, high levels of dropouts, non-systematic effort, grade retention and academic failure. These findings are in accordance with a number of st ud- ies, reporting that typical inmates of correctional institutions are school dropouts (Winters, 1997). Moreover, it has been repeat- edly found that grade retention is an educational experience for approximately 40%-50% of incarcerated youth (Fejes-Men- doza, Miller, & Eppler, 1995; Mazerolle, 1998; Zabel & Nigro, 1999). Low school attendance has also been found in two stud- ies conducted in Greece. In the first one, the average duration of education was approximately four years in a sample of 55 juvenil e off enders (L ivaditis, Fot iadou, Koulouba rdou, Samakouri, Tripsianis, & Gizari, 2000) whereas in the second one, 63.3% of 60 juvenile offenders was not registered with any school at the time of the study (Papageorgiou & Vostanis, 2000). When asked about their academic achievement during their school attendance, the vast majority of the participants reported low and very low achievement in reading, writing and mathe- matics and overall low scholastic competence. This is consis- tent with studies reporting high prevalence rates of learning disabilities among young offenders, who seem to perform at significant lower levels than those expected for their academic age level (Shelley-Tremblay, O’Brien & Langhinrichsen- Rohling, 2007; Wang, Blomberg, & Spencer, 2005). Taken together, the above findings reveal that learning dis- abilities and antisocial behaviour co-exist to a high degree. The question that can be raised consequently concerns the nature of these learning disabilities and the ways through which they are linked to delinquency. The findings support the existence of high levels of psycho- social adversity within our sample, as indicated by the large family size, low parental educational level, bad financial situa- tion and parental offending history in a great number of cases. Psychosocial adversity may be related to delinquency in two ways. First, dysfunctional families may not encourage children to systematically attend school and invest in school effort which, in turn, may facilitate their engagement in delinquent activities. Alternatively, being raised up in deprived families might directly create the prerequisites for the development of antisocial behaviour, even without the mediation of school failure, through loose socialisation practices. However, a further finding of this study might shed more light to the possible link between learning disabilities and anti- social behaviour in the majority of the young offenders. About one quarter of the participants displayed attention problems at a clinical level, according to the YSR and another 18.3% of them displayed such problems at a borderline level. Although these rates represent screening estimates and not clinical diagnoses of ADHD, similar rates are reported by a number of other studies as well (Chae, 2001; Moffitt & Silva, 1988; Richardon, 2000). In addition, similar rates have been reported in studies using the CBCL, on which the YSR was modelled (Moser & Doreleijers, 1997). The possible presence of ADHD in young delinquents raises the hypothesis that, at least in a number of cases, learning dis- abilities were the result of neuropsychological deficits, thus leading to under-attainment, poor school attendance and low effort rather than resulting from them (Maniadaki & Kakourou, 2007). This point of view is also supported by other researchers who pinpoint that attention difficulties might underlie the asso- ciation between learning problems and delinquency (Manguin, Loeber, & Lemahieu, 1993; Shelley-Tremblay, O’Brien & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2007). Of course, once a child who presents specific learning difficulties goes undiagnosed and experiences repeated academic failures, he or she may avoid school effort in general and enter a vicious cycle where specific learning difficulties causes abstinence from school and absti- nence of school aggravates learning difficulties (Wang, Blom- berg, & Spencer, 2005). Research on the academic characteristics of incarcerated youth supports the above scenario. It has been found that these adolescents usually function in the low-average to belowaver- age range of intelligence (Foley, 2001) and show general verbal deficits (Rincker, Reilly, & Braaten, 1990) and language im- pairment (Gellert & Elbro, 1999). On the other hand, children with ADHD also present wit h si milar cognitive profiles (Barkley, 1998). Therefore, it is possible that much of the cognitive deficit associated with delinquency could be e xplai ned b y the pres ence of a significant number of cases with histories of ADHD among delinquent samples (Moffitt & Silva, 1988). In other words, it is possible that ADHD underlies, to a certain degree, learning disabilities experienced by a lot of juvenile delinquents. Besides learning disabilities, other individual risk factors usually associated with juvenile delinquency include impulsive- ity, inability to grasp future consequences of behavior, inability to delay gratification, difficulty to self-regulate emotion, need for stimulation and excitement, low frustration tolerance, etc. (Keilitz & Dunivant, 1986; Thornberry, 1994). These inborn traits, related to personality, temperament and cognitive ability, make children more susceptible to other risks in the environ- ment. Most of the above characteristics are very common in children with ADHD (Hawkins, 1995; Sonuga-Barke, 2003). Conclusion Therefore, it seems reasonable to suggest that ADHD, with its cognitive and behavioural deficits may be linked to delin- quency: 1) indirectly through school failure which results from specific learning disabilities, which usually co-exist with the disorder, and 2) directly through functional deficits in self- control abilities which have been consi stently related to ele vated  K. MANIADAKI & E. KAKOUROS 57 involvement in delinquency and crime (Pratt et al., 2002). Impulsive children have little ability to draw from past ex- periencees or to anticipate future consequences. In addition, lack of impulse control reflects handicaps in verbally mediated control over one’s behaviour (Tarter, Hegedus, Alterman, & Katz-Garris, 1983). Due to the above deficits, children with ADHD usually experience repeated failures at school and face peer rejection as well. Parents and teachers who struggle on a daily basis with getting these children to adhere to family and school rules often display disapproval, fewer rewards and over- all negative behaviour towards them (Johnston, 1996). These reactions usually lead to the escalation of conflicts and increase the likelihood of the establishment of cycles of reciprocated aggression. The accumulation of negative experiences may lead to low self-esteem at adolescence and facilitate linkage with deviant peers. Such a choice seems promising for these children in order to prove themselves through their participation in de- linquent acts since they don’t consider themselves able to do this through positive ways (Tarolla, Wagner, Rabinowitz & Tubman, 2002). However, all children with ADHD do not become delin- quents and all delinquent juveniles do not display ADHD (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001). It has been suggested that there is a specific subgroup of children with ADHD who are at special risk for delinquent offending. These children are characterized not only by neuropsychological dysfunction and aggressive behaviour, but by adverse family circumstances as well (Moffitt & Silva, 1988). Thus, ADHD appears to be a catalyst with primarily family variables increasing the risk that ADHD be- haviour will lead to delinquency (Goldstein, 1997). This study strongly supports the existence of such a pathway to delin- quency, among others. These findings have important public policy implications. Routine ADHD screening at schools seems critical for the diagnosis and appropriate treatment of underperforming stu- dents. The identification of those children with ADHD who are at particular risk to get involved in criminal activates due to the presence of additional risk factors, such as psychosocial adversity, and the consequent administration of support and treatment, might be a powerful preventive method of juvenile delinquency (Schweinhart & Weikart, 1980). Furthermore, the identification of those incarcerated youth who present ADHD and/or learning disabilities is of the utmost importance. It seems likely that ADHD is impairing the ability of offenders to cope effectively with the strains and demands of imprisonment (McCallon, 2000). In addition, educational re- mediation that can help young people with ADHD overcoming their literacy deficits may be these people’s last opportunity to acquire academic and vocational skills. Juvenile offenders that possess higher literacy levels have been found to have lower rates of recidivism and enjoy a more successful transition from the correctional facility to the community (Foley, 2001). Finally, the criminal justice community may benefit consi- derably from an expanded understanding of ADHD, as this could assist law enforcement personnel to better understand the dysfunctions that bring a significant number of offenders into conflict with the criminal justice system (Goldstein, 1997). Despite general agreement of our findings with similar stu- dies, there are a number of methodological limitations which need to be considered. First, the study shares in the weakness of all self-report studies regarding the prevalence of attention pro- blems. However, this method is widely accepted for use with this population (Corneau & Lanctot, 2004). Second, this study cannot yield any causal relationships as it was restricted to prevalence estimates. Thus, the scenarios proposed are highly speculative and need testing through longitudinal studies and more sophisticated statistical analyses. Finally, it is acknow- ledged that antisocial behaviour is the result of the interaction of multiple risk factors and we do not claim that the identi- fication and treatment of ADHD would be a panacea for the elimination of juvenile delinquency. However, this study provides a basis for future studies that will move from the investigation of the correlation of delin- quency with disabilities in specific learning domains, for exam- ple reading, to the investigation of more complex interactions, including disorders with both cognitive and behavioral correlates, like ADHD, taking into account psychosocial adversity as well. Furthermore, future studies should consider gender differences in the study of juvenile delinquency since it is very possible that different pathways to crime may exist for boys and gir ls. References Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychia- try. Achenbach, T. M. (1997). Manual for the young adult self-report and young adult behaviour. Burlington: University of Vermont, Depart- ment of Psychiatry. Babinski, L. M., Hartsough, C. S., & Lambert, N. M. (1999). Childhood conduct problems, hyperactivity-impulsivity, and inattention as pre- dictors of adult criminal activity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 347-355. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00452 Barkley, R. A. (1998). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A hand- book for diagnosis and treatment (2nd Edition). New York: Guilford. Bonny, E. A., Britto, T. M., Klostermann, K. B., Hornung, W. R., & Slap, B.G. (2000). School disconnectedness: Identifying adolescents at risk. Pediatrics, 106, 1017-1031. doi:10.1542/peds.106.5.1017 Brown, R. T., Free man, W. S ., Pe rrin , J. M., Stein, M. T ., A mler, R. W., Feldman, H. M., Pierce, K., & Wolraich, M. L. (2001). Prevalence and assessment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in pri- mary care settings. Pediatrics, 107, 1-11. doi:10.1542/peds.107.3.e43 Casey, P., & Keilitz, I. (1990). Estimating the prevalence of learning disabled and mentally retarded juvenile offenders: A meta-analysis. In P. E. Leone (Ed.), Understanding troubled and troubling youth (pp. 82-101). Newbur y Park, CA: Sage. Chae, P. K. (2001). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Korean juvenile delinquents – statistical date included. Adolescence, 36, 702-725. Corneau, M. & Lanctot, N. (2004). Mental health outcomes of adjudi- cated males and females: The aftermath of juvenile delinquency and problem behaviour. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 14, 251-262. doi:10.1002/cbm.592 Fejes-Mendoza, K., Miller, D., & Eppler, R. (1995). Portraits of dys- function: criminal, educational, and family profiles of juvenile fe- male offenders. Education and Tre atment of Children, 18, 309-321. Fergusson, D. M., & Lynsky, M. T. (1997). Early reading difficulties and later conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psy- chiatry, 38, 899-907. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01609.x Foley, R. M. (2001). Academic characteristics of incarcerated youth and correctional educational programs: A literature review. Journal of Emotional and Be h av io ra l D is or ders, 9, 248-259.  K. MANIADAKI & E. KAKOUROS 58 doi:10.1177/106342660100900405 Gellert, A., & Elbro, C. (1999). Reading disabilities, behaviour prob- lems and delinquency: A review. Scandinavian Journal of Educa- tional Research, 43, 131-155. doi:10.1080/0031383990430202 Goldstein, S. (1997). Attention-deficit/hypearctivity disorder: Impli- cations for the criminal justice system. Law Enforcement Bulletin, 66, 11-16. Granleese, J., & Joseph, S. (1994). Reliability of the harder self-per- ception profile for children and predictors of global self-worth. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 1 55, 487-492. doi:10.1080/00221325.1994.9914796 Harter, S. (1985). Manual for the self-perception profile for children. Denver, CO: University of De nv er Press. Hawkins, J. (1995). Controlling crime before it happens: Risk-focused prevention. National Institute of Justice Journal, 229, 10-18. Ivarsson, T., Gillberg, C., Arvidsson, T., & Broberg, A. G. (2002). The Youth Self-Report (YSR) and the Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS) as measures of depression and suicidality among adolescents. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 11, 31-37. doi:10.1007/s007870200005 Johnston. C. (1996) Parent characteristics and parent-child interactions in families of non-problem children and ADHD children with higher and lower levels of oppositional-defiant behaviour. Journal of Ab- normal Child Psychology, 24, 85-104. doi:10.1007/BF01448375 Jorm, A. F., Share, D. L., Matthews, R., & MacLean, R. (1986). Be- haviour problems in specific reading retarded and general reading backward children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychiatry, 27, 33-43. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb00619.x Kakouros, E. (1998). The outcome of specific learning disabilities at adolescence. Archives of the Association of Psychology and Psychia- try for Adults and Children, 19, 89- 92. (in Greek) Kakouros, E., & Maniadaki, K. (2007). Signs of psychopathology among juvenile offenders in Greek prisons for minors. Paper pre- sented at the 1st European SEBCD Conference, Book of Abstracts (p. 49), Malta. Keilitz, I., & Dunivant, N. (1986). The relationship between learning disability and juvenile delinquency: Current state of knowledge. Re- medial and Special Education, 7, 18-26. doi:10.1177/074193258600700305 Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Rebholz, C. L., O’Brien, N., O’Farrill- Swails, L., & Ford, W. (2005). Self-reported co-morbidity of depres- sion, ADHD, and alcohol/substance use disorders in male youth of- fenders residing in an alternative sentencing program. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work: Advances in Practice, Programming, Research and Policy, 2, 1-17. Leone, P. E., & Meisel, S. (1997). Improving education services for students in detention and confinement facilities. Children’s Legal Rights Journal, 17, 1- 12. Livaditis, M., Fotiadou, M., Kouloubardou, F., Samakouri, M., Trip- sianis, G., & Gizari, F. (2000). Greek adolescents in custody: Psy- chological morbidity, family characteristics and minority groups. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 11, 597-607. Makri-Botsari, E., & Robinson, P. (1991). Harter’s self-perception profile for children: A cross-cultural validation in Greece. Evaluation and Research in Education, 5, 135- 143. doi:10.1080/09500799109533305 Manguin, E., Loeber, R., & Lemahieu, P. G. (1993). Does the rela- tionship between poor reading and delinquency hold for males of different ages and ethnic groups? Journal of Emotional and Behav- ioral Disorders, 1, 88-99. doi:10.1177/106342669300100202 Maniadaki, K., & Kakouros, E. (2008). Social profiles and mental health problems of young offenders in detention in Greece. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 18, 207-215. doi:10.1002/cbm.698 Maniadaki, K., & Kakourou, N. (2007). The contribution of untreated learning disabilities to the development of juvenile delinquency. Poster presented at the 1st European SEBCD Conference, Book of Abstracts (pp. 54), Malta. Maniadaki, K., Kakouros, E., & Karaba, R. (2009). Juvenile delin- quency and mental health. In A. Kakanowski & M. Narusevich (Eds.), Handbook of Social Justice (pp. 1-44). New York: Nova Pub- lishers. Maniadaki, K., Kakouros, E., & Karaba, R. (2010). Psychopathology in juvenile delinquents. New York: Nova Science Publishers. Mannuza, S., Gitte lman-Klein, R., Be ssler, A., Malloy, P., & LaPadu la, M. (1993). Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: Educational achi- evement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Archives of Gen- eral Psychiatry, 50, 565-576. Mazerolle, P. (1998). Gender, general strain, and delinquency: An empirical examination. Justice Quarterly, 15, 65-91. doi:10.1080/07418829800093641 McCallon, D. (2000). Diagnosing and treating ADHD in a men’s prison. In D.H. Fishbein (Ed .), The science, treatment, and prevention of an- tisocial behaviors: Application to the criminal justice system (pp. 17-1 to 17-21). Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute. Meltzer, L. J., Lev ine, M. D., Karniski , W., Palfrey, J. S., & Clarke, S . (1984). An analysis of the learning style of adolescent delinquents. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 17, 600-608. doi:10.1177/002221948401701006 Ministry of Justice (2003). Issues of Correctional Policy. Retrieved 19 June 2007 from http://www.ministryofjustice.gr /eu 2003/ pj-pd f/ke f11. pdf Moffitt, T. E. (1990). Juvenile delinquency and attention deficit disor- der: Boys’ developmental trajectories from age 3 to age 15. Child Development, 61, 893-910. doi:10.2307/1130972 Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2001). Childhood predictors of life-course persistent and adolescent-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 355-375. doi:10.1017/S0954579401002097 Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1988). Self-reported delinquency, neuro- psychological deficit, and history of attention deficit disorder. Jour- nal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 16, 553-569. doi:10.1007/BF00914266c Moser, F., & Doreleijers, T. A. H. (1997). An explorative study of juvenile delinquents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. European Journal on Crimina l Policy and Research, 5, 67-81. doi:10.1007/BF02677608 Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Fijen, P. (2003). The self-perception profile for children: Further evidence for its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Perso n a lity and Individual Differences, 35, 1791-180 2. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00004-7 Otto, R. K., Greenstein, J. J., Johnson, M. K., & Friedman, R. M. (1992). Prevalence of mental disorders among youth in the juvenile justice system. In J. J. Cocozza, & W.A. Seattle (Eds.), Responding to the mental health needs of youth in the juvenile justice system (pp. 7-48). WA: The National Coalition for the Mentally Ill in the Crimi- nal Justice System. Pajer, K. A. (1998). What happens to “bad” girls: A review of the adult outcomes of antisocial adolescent girls. American Journal of Psy- chiatry, 155, 862-870. Papageorgiou, V., & Vostanis, P. (2000). Psychosocial characteristics of Greek young offenders. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 11, 390-400. Pratt, T. C., Cullen, F. T., Blevins, K. R., Daigle, L., & Unnever, J. D. (2002). The relationship of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder to crime and delinquency: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 4, 344-360. doi:10.1350/ijps.4.4.344.10873 Richardson, W. (2000). Criminal behaviour fuelled by Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and addiction. In D. H. Fishbein (Ed.), The science, treatment, and prevention of antisocial behaviors: Applica- tion to the criminal justice system (pp. 18-1 to 18-15). Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute. Rincker, J. L., Reilly, T. F., & Braaten, S. (1990). Academic and intel- lectual characteristics of adolescent juvenile offenders. Journal of Correctional Education, 41, 124-131.  K. MANIADAKI & E. KAKOUROS 59 Roussos, A., Francis, K., Zoubou, V., Kiprianos, S., Prokopiou, A., & Richardson, C. (2001). The standardization of Achenbach’s Youth Self-Report in Greece in a national sample of high school students. European Child and Adolesc ent Psychiatry, 10, 47-53. doi:10.1007/s007870170046 Schweinhart, L. J ., & Weikart, D. P. (1980). Young children grow up: The effects of the Perry preschool program on youths through age 15. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope. Shelley-Tremblay, J., O’Brien, N., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2007). Reading disability in adjudicated youth: prevalence rates, current models, traditional and innovative treatments. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 12, 376-392. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2006.07.003 Skaret, D., & Wilgosh, L. (1989). Learning disabilities and juvenile delinquency: A causal relationship? International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 12, 113-123. doi:10.1007/BF00117209 Snowling, M., Adams, J. W., Bowyer-Crane, C., & Tobin, V. (2000). Levels of literacy among juvenile offenders: The incidence of spe- cific reading difficulties. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 10, 229-241. doi:10.1002/cbm.362 Sonuga-Barke, E. J. (2003). The dual pathway model of AD/HD: An elaboration of neuro-developmental characteristics. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 27, 593-604. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.005 Spinellis, C., & Tsitsoura, A. (2006). The emerging juvenile system in Greece. In J. Junger-Tas & S. H. Decker (Eds.), International hand- book of juvenile justice. Berlin: Springer. Steiner, H., Williams, S. E., Benton-Hardy, L., Kohler, M., & Duxbury, E. (1997). Violent crime paths in incarcerated juveniles: Psychologi- cal, environmental, and biological factors. In A. Raine, D. Farrington, & B. Brennan (Eds.), The biosocial basis of violence (pp. 325-328). New York: Plenum. Tarolla, S. M., Wagner, E. F., Rabinowitz, J., & Tubman, J. G. (2002). Understanding and treating juvenile offenders: A review of current knowledge and future directions. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 7, 125-143. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00041-0 Tarter, R. E., Hegedus, A. M., Alterman, A. L., & Katz-Garris, L. (1983). Cognitive capacities of juvenile violent, non-violent, and sexual offenders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 171, 564-567. doi:10.1097/00005053-198309000-00007 Thornberry, T. (1994). Risk factors for youth violence. In L. McCart (Ed.), Kids and Violence (pp. 8-14). Washington, DC: National Gov- ernors Association. Wang, X., Blomberg, T. G., & Spencer, D. (2005). Comparison of the educational deficiencies of delinquent and nondelinquent students. Evaluation Review, 29, 291-312. doi:10.1177/0193841X05275389 Williams, S., & McGee, R. (1994). Reading attainment and juvenile delinquency. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35, 441- 461. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01733.x Winters, C. A. (1997). Learning disabilities, crime, delinquency and special education pla cement. Adolescence, 32, 451-462. Zabel, R. H., & Nigro, F. A. (1999). Juvenile offenders with behavioral disorders, learning disabilities and no disabilities: Self-reports of personal, family and school characteristics. Behavioral Disorders, 25, 22-40.

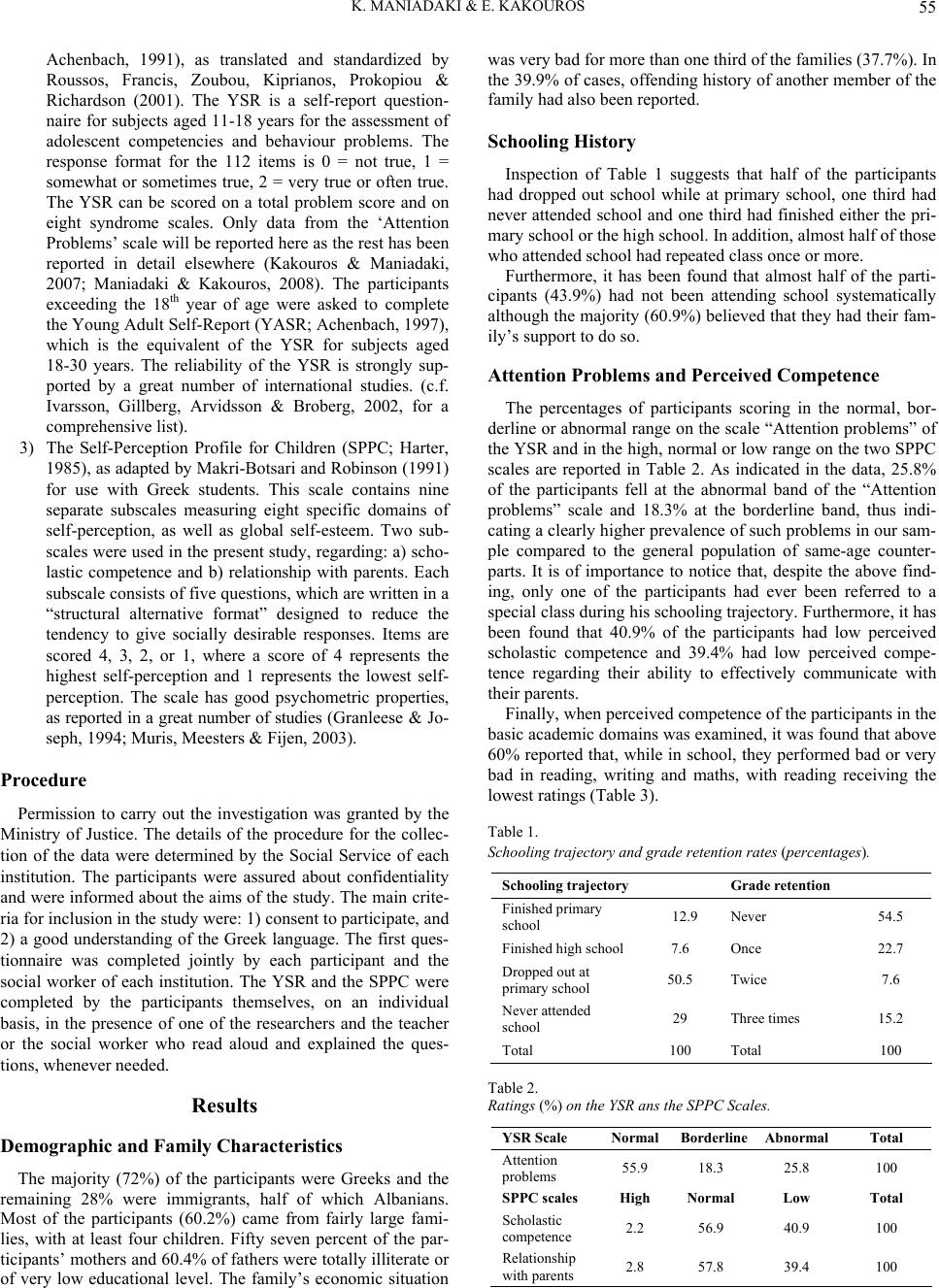

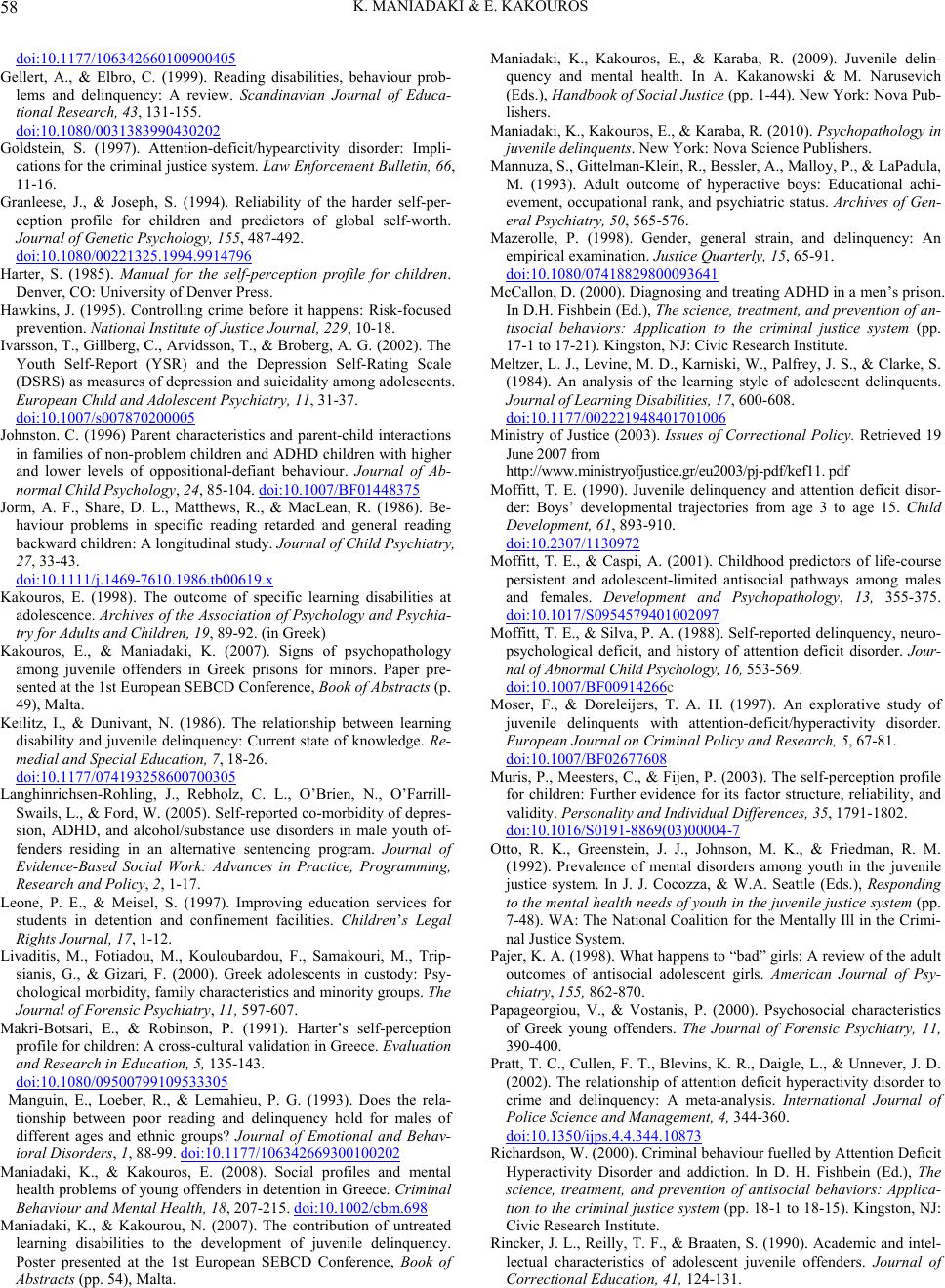

|