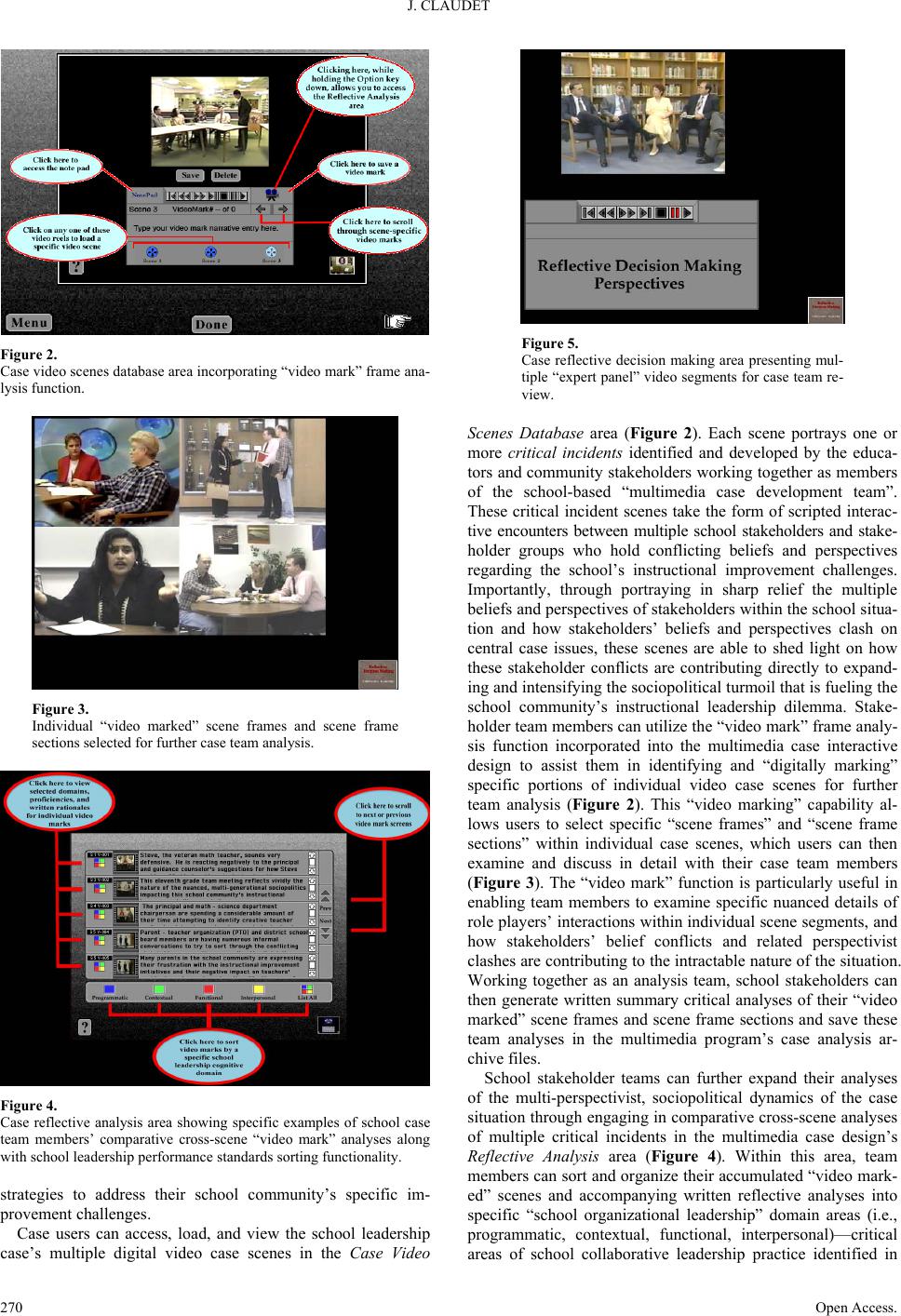

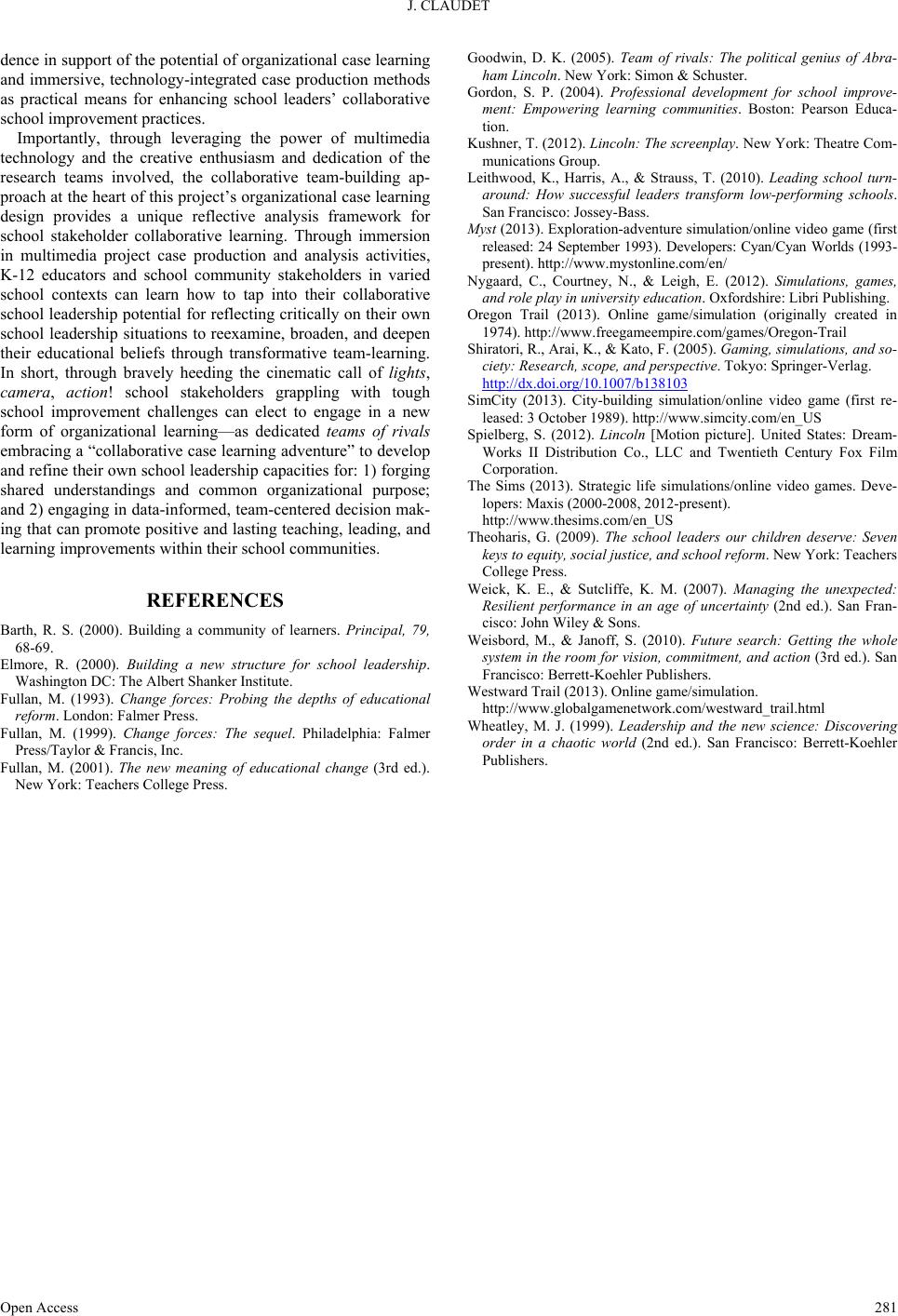

Advances in Applied Sociology 2013. Vol.3, No.7, 258-281 Published Online November 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2013.37035 Open Access 258 Instructional Leadership and the Sociopolitics of School Turnarounds: Changing Stakeholder Beliefs through Immersive Collaborative Learning Joseph Claudet Department of Ed uc a t i o n a l Ps ychology and Leadership, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA Email: joe.claudet@ttu.edu Received August 31st, 2013; revised September 30th, 2013; accepted October 7th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Joseph Claudet. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attri- bution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This article highlights case production and analysis efforts associated with a multi-year, multimedia case development project focused on providing alternative organizational learning opportunities to regional K-12 schools and school districts. The School Leadership Case Simulation (SLCS) Project utilizes a unique multi-entity partnership and school-based collaborative learning design in which teams of univer- sity-based education researchers, multimedia production specialists, and regional education service center school improvement consultants work in tandem with K-12 school educators and community members to help these school stakeholders develop and produce multimedia organizational learning cases about their own real-world, context-specific school dilemma challenges. Collaborative team learning efforts of one group of school educators and community stakeholders grappling with an organizationally entrenched set of instructional leadership and school improvement challenges in one regional high school community are presented. Project findings relating to the viability and usefulness of the project’s multi-entity, immersive collaborative teaming design and multimedia-integrated case learning tools for helping groups of K-12 school community stakeholders learn how to adopt a team-centered organizational learning approach to reframing their real-world school leadership dilemma challenges and engage directly in data-informed, collaborative decision-making are presented and discussed. Keywords: Multimedia Case Development; Organizational Learning; Instructional Teaming; School Turnaround Leadership Introduction As an organizational psychologist focusing on studying col- laborative leading and learning behavior in education settings, I am continually fascinated by the complex dynamics involved in the ways multiple stakeholders and stakeholder groups confront difficult, system-wide school improvement dilemma situations and navigate the challenges of enacting meaningful organiza- tional change. To explore as directly as possible the processes of change leadership and organizational learning in real-world education contexts, I have spent considerable time over the past 25 years serving as a staff developer and school improvement consultant to K-12 schools and school districts in the southern and southwestern United States. Within this capacity, I have worked with large numbers of education stakeholders (teachers, campus principals and assistant principals, instructional coach- es, district-level curriculum program coordinators and adminis- trators, parents, elected school board officials, and community members) to help these individuals learn how to work together effectively as collaborative leading and learning teams to di- rectly address and find creative solutions to their entrenched school improvement dilemma challenges. During the process of engaging in this work over many years, I have developed a penchant for employing phenomenological case methods in conjunction with a broad-based sociological inquiry approach to glean rich descriptions and case-specific detail about these school leaders, the varied school community contextual envi- ron me nt s wi th i n wh i c h t hey i nt e ra ct , an d t he multi-faceted, real- world instructional leadership challenges they face. Along this journey, I have also expended considerable time and energy in exploring the potential of using available multimedia technolo- gies in connection with theatrical production techniques as creative organizational learning tools to help school educators and associated community stakeholders engage in immersive “organizational case learning” projects to produce multimedia cases about their own complex school leadership experiences. These case-based learning projects are designed as an alterna- tive means for enabling education leaders to intently exam- ine—in a team-centered and data-intensive way—their school dilemma situations in order to: 1) reframe their organizational challenges; 2) focus on and energize their collaborative teaming practices; and 3) improve their school improvement decision- making. I have discovered that this kind of immersive, technol- ogy-integrated case learning method can be useful in helping large groups of education stakeholders who have reached an impasse in their school improvement efforts learn how to think differently and work together in new ways to better address the political pressures and myriad uncertainties that often accom- pany entrenched, organization-wide dilemma situations.  J. CLAUDET Steven Spielberg’s 2012 movie Lincoln captures well the kind of determined change agent leader skills and creative team- forging abilities that are needed by those attempting to lead organizations that are experiencing system-wide dilemma chal- lenges—challenges that are fueled by intense, multi-stake- holder perspectivist conflicts and political turmoil. As the coun- try’s 16th president during the American Civil War (1861-1865), Abraham Lincoln (played in the movie by Daniel Day-Lewis) had to confront head-on the intractable leadership impasse that arose as multiple, competing groups of stakeholders and stake- holder groups spreading across the American Union pro- claimed (and acted upon) their passionate and unbending con- flicting beliefs regarding the country’s proper organizational di- rection and purpose. The entire sociopolitical environment of the United States at the time was being torn apart by the fier- cely conflicting perspectives and beliefs of citizens concerning the legality of slavery and the rights of individual states to de- termine their own economic destiny. These issues and how they should be properly addressed were of central importance to both southern and northern states, and to the future of the entire country. And, as the Lincoln movie portrays, in the early months of 1865 (at a time when a recent succession of northern victo- ries was making it more and more probable that the war might soon be coming to a close), Lincoln knew that he had to act boldly and decisively (while the horrible atrocities of the war were still vivid in people’s minds) to get the Thirteenth Amend- ment to the nation’s Constitution—the amendment that would abolish slavery in the country forever for both present and fu- ture generations—passed by Congress. At this important time in the nation’s thus far brief history, the clashing southern and northern views regarding slavery were nowhere more passion- ately expressed and debated than in the United States Congress. Whereas a majority of Republican senators had enabled the proposed amendment to pass easily through the Senate, it was not at all clear whether the measure would be able to get enough support to gain passage in the House of Representatives, within which there were sizeable numbers of representatives putting forward passionate arguments both for and against the amend- ment. Rather than shrink from this conflict, Lincoln seized upon this rivalry and brought it close to himself by appointing men with differing perspectives and beliefs to serve on his Executive Cabinet. Although, as a group, these cabinet members favored preserving the Union, their varying temperaments and contrast- ing beliefs about the right way to go about accomplishing this task infused the Lincoln presidency cabinet meetings with tre- mendous energy (and, often, passionate disagreement). Lincoln tapped into the multi-perspectivist friction and political energy of his executive cabinet—his administrative team of rivals—as a source of leadership strength within his administration (Good- win, 2005). As an organizational change leader, Lincoln knew intuitively that in order to build a “team mentality” out of such disparate forces (both within his own cabinet and within the larger United States C ongress) he had to bring these fo rces close together. Lincoln knew he had to fashion a highly immersive collaborative team-learning environment within and through which these rival political leaders could discuss their differ- ences and, in doing so, learn to listen openly to and respect each others’ views, and from there begin to forge a workable con- sensus—to find “common ground” based on shared principles. Lincoln’s genius as an organizational change leader lay in his intuitive understanding that through bringing such strong- willed personalities with passionate conflicting beliefs close to- gether in a team-of-rivals environment, this very teaming envi- ronment could become a powerful catalyst that could motivate, challenge, and inspire these stakeholder leaders to use their combined energies and principled convictions to construct—out of their collective differences—a coherent team vision and prac- tical plan of leadership action. In an early scene in the movie, William H. Seward (played by David Strathairn), Lincoln’s Secretary of State, admonishes the President on the poor chances which the proposed Thir- teenth Amendment had, in Seward’s view, of gaining passage through the House of Representatives. Seward, a man of keen political intelligence, berates Lincoln for attempting such a bold move and attempts to dissuade Lincoln from embarking on an enterprise that will surely fail and mar his second term as president. Seward explains to Lincoln that they were twenty votes short of the number of votes necessary to ensure the amendment’s passage in the House of Representatives and that it would be very unlikely that these votes could be secured. As Seward emphasizes in this scene, the chances of building bi- partisan support for the amendment’s passage were practically non-existent: “Why tarnish your invaluable luster with a battle in the House [of Representatives]? It’s a rats’ nest in there, the same gang of talentless hicks and hacks that rejected the amendment ten months back. We’ll lose”. To which Lincoln, the ever-adept political consensus builder, replied: “I like our chances now” [emphasis added] (Kushner, 2012: p. 19). Lin- coln’s confidence as a change agent leader was firmly grounded in his realization that within such passionate rivalries resided the potential for deep common understanding—deeper insights and common ground could be forged in the crucible of multi- perspectivist conflict. And that, paradoxically, a team compris- ed of rivals harboring contrasting organizational beliefs and political views could become a practical vehicle for forging new shared vision and common purpose on how to move the nation forward decisively. The Lincoln movie presents a remarkably compressed and probing portrait of team-centered “change agent leadership”. Lincoln’s nuanced insights into the sociopolitics of his time and firm grasp of the American people’s fervent desire to address their challenges head-on and to make sense of their complex reality helped Lincoln realize that his central challenge and task as a leader was to find a creative way to reunite the people around core principles. And Abraham Lincoln, the insightful change agent leader, accomplished this through bringing people with conflicting ideas and beliefs close together in an immer- sive team-building environment within which passionate diffe- rences could be openly discussed and carefully examined, and ultimately refashioned to build common understandings—to create new organizational unity and sen se of purpose from, to use Doris Kearns Goodwin’s evocative phrase, a team of rivals (Goodwin, 2005). Lincoln intuitively understood that immersing strong-willed individuals with passionate views and beliefs in an intensive, extended team of rivals environment could become, paradoxically, a powerful organizational learning catalyst for challenging and enabling these stakeholders—motivated by the power of team-initiated cogent argument and carefully consid- ered evidential reasoning—to re-examine and ultimately change their beliefs for the sake of the organizational survival and fu- ture welfare of the country. In very similar ways, this manner of responding to the leading and learning needs of organization stakeholders experiencing multi-perspectivist dilemma challeng- es through utilizing immersive team-building and organizatio- Open Access 259  J. CLAUDET nal sense-making strategies has been a dominant feature of my own ongoing consultant work spanning two decades with edu- cators and community stakeholders in K-12 schools and school districts. A central emphasis of my consulting efforts has and continues to be on assisting groups of K-12 school community stakeholders—who also desire to address their school improve- ment challenges “head-on” and who strive to “make sense” of their complex school leadership situations—to find new ways to work together to engage collaboratively in data-informed de- cision making to enhance the overall quality of teaching, lead- ing, and learning in their schools and districts. Through my involvement, beginning in the early 1990s, as a school improvement a nd staff development consultant for sc hool districts in the Permian Basin region of West Texas, I have had the privilege of working with large numbers of education stake- holders in a number of regional elementary and secondary school communities and becoming familiar with the campus-specific school leadership and improvement challenges facing these school leaders. A singular focus of my ongoing consultant ef- forts in working with these school stakeholders has been on helping stakeholders in these communities reexamine and lev- erage their own contextual situations and school performance data to develop “organizational cases” about their own dilemma challenges. These organizational cases are designed as an al- ternative team-building means to enable these stakeholders to learn how to work together in new ways to generate deep colla- borative insights about their leadership challenges and fashion creative, actionable school improvement strategies—and, as a way to jumpstart these school stakeholders’ renewed commit- ment to their own ongoing organizational learning and devel- opment. During this time, my university-based, multimedia pro- ject research team and I have worked and continue to work di- rectly with stakeholder groups in several different school commu- nities in the region to develop a number of multimedia organ- izational learning cases about these school stakeholders’ own real-world school improvement dilemma challenges. The indi- vidual organizational case development project work completed by groups of school stakeholders and university-based, multi- media production teams at each participating regional campus site is designed as an alternative staff development approach to helping these K-12 school community stakeholders grow and realize their potential as organizational leading and learning teams. A central focus of this approach is on immersing school community stakeholders in each participating school (teachers, campus administrators, parents, community leaders, and asso- ciated central office staff) directly—in an intensive, in-depth way—in analyzing their own school community situational and performance data in order to develop a “multimedia organiza- tional case” about their school’s own school improvement chal- lenges. This alternative multimedia case development method is employed as a creative means to help school stakeholders at each participating school explore learning how to work together in a new way—as a school community multimedia case pro- duction and analysis team—to collaboratively reexamine their own school dilemma situations from different individual and group perspectives and to brainstorm new team-generated solu- tions to address their school improvement challenges. As an off-shoot of this ongoing school district-university partnership work, I sometimes receive calls from principals in neighboring schools and school districts in the region who have heard about the case development work my research team and I have been engaging in with other school communities, and who are interested in talking with me about their own school lead- ership challenges. This article reports on the collaborative case development and analysis project work my university col- leagues and I completed with one such group of school com- munity stakeholders. In responding to this principal’s request for assistance, I soon learned that she and her fellow campus educators and community stakeholders were struggling with a complex set of politically charged organizational challenges arising from an entrenched instructional leadership and school improvement dilemma situation—a situation that was boiling over into the larger district community and fraying the organi- zational fabric of their high school teaching and learning com- munity. A High School Community Struggling with an Entrenched School Improvement Dilemma Around the middle of August 2007 I received a telephone call from a principal of a large high school in one of the West Texas regional school districts who was very interested in speaking with me about her school community and the school improvement challenges she was facing. During this initial call, the principal indicated that she was just beginning her second year as the principal of this high school campus, having moved here from another area of the state. The principal informed me that her superintendent had told her that he had hired her be- cause he had high confidence in her abilities to bring together stakeholders at this school to “turn things around” and move the school community forward. In the last several years, this high school has been struggling to deal with a number of inter- related instructional leadership challenges, including: 1) an in- creasingly diversified district student population base with a continuously growing number of Hispanic families and students entering the district, many of whom become students at this high school; 2) an alarming trend of decreasing student exit exam performance scores in STEM-related (i.e., science, tech- nology, engineering, and math) content areas—particularly math and science; 3) a large and multi-generational teaching staff; and 4) continuing pressure from the district central office and area business community constituents to find creative ways to integrate technology effectively into classroom- and grade-le- vel instruction. The principal explained to me that she was at- tracted to this school district community, and specifically to this high school position, because she viewed herself as a com- munity change agent, and she was intrigued by the set of unique school community leadership challenges this school was facing. The principal also stated that she was impressed with the school community’s considerable potential—in her view—for being able to come together to address these challenges head-on to bring about positive change and improvement. This veteran principal’s evident enthusiasm for school change leadership came across clearly during our telephone conversation as she recounted a few of the efforts she had already made at her campus to become familiar with her teachers and parents, and the school’s various co mmunity stakeholders and education con- stituencies. Following our initial telephone conversation, I was able to learn that this particular principal was well respected by mem- bers of the state’s secondary school principal’s association and had developed a solid reputation as a no-nonsense “school turn- around change agent”. In her twelve years as a campus admin- istrator in previous school leadership positions, she had gar- Open Access. 260  J. CLAUDET nered praise from educators and community members alike for being “tough, but fair” in her approach to instructional leader- ship and school reform. Eager to meet this principal in person and learn more about her school and the intriguing leadership challenges she had briefly described to me via telephone, I scheduled an on-campus visit in early Septemb er. I arrived at the campus early on a Monday morning in Sep- tember. The principal greeted me in the administrative suite, welcomed me to the campus, and invited me into her office. The principal was clearly very interested in continuing our initial conversation about her school’s instructional improve- ment challenges. To help me more fully understand her school’s overall instructional environment and some of the leadership challenges she has been facing, she offered to share with me a summary overview of the history of her leadership efforts to date at the school. The principal explained that the student demographics at the high school and the district have changed in the past three years because of a redistricting effort in response to burgeoning population growth that has caused some students from neighboring areas to be bused to the cam- pus. Many of the new students the high school is now serving are minorities—predominantly Hispanic students, reflecting the continuing large growth in the Hispanic population occurring throughout the West Texas region. In addition, the school’s teaching staff reflects a broad spectrum of professional teaching experience, with a little over a third of the staff consisting of veteran faculty who have been teaching in the district for 15 to 20 years or more, several of whom have been teaching at this school for most or all of that time. Some recent teacher retire- ments, in conjunction with the school’s student enrollment growth, have enabled the district to recruit and hire a number of new faculty members, and this principal stated that recruiting and hiring new faculty had been a particular priority of hers du- ring the summer preceding her first year at this school. Most importantly, as the principal had briefly mentioned during our initial telephone conversation, the campus is currently strug- gling to deal with decreasing student “end-of-course” exit exam performance scores, particularly in math and science content areas. The principal emphasized that district central office ad- ministrators have been unrelenting in their efforts to “pressure” campus principals to engage proactively with their teachers to respond to the state’s student performance accountability de- mands, particularly in “STEM” (i.e., science, technology, engi- neering, and math) content areas. As a result, the principal ex- plained that a large part of her time during her first year here has been devoted to instructional oversight in getting to know and working with her teachers in addressing these instructional improvement challenges. The principal further explained that during the past three years the superintendent had moved aggressively to seek and acquire funding to implement several district improvement ini- tiatives, including a district-wide dropout recovery program, expanded staff development opportunities for teachers, and a new instructional teaming initiative designed to bolster teach- ers’ collaborative planning to enhance student learning. To ad- dress student learning performance challenges at her school, the principal indicated she has been working with the district’s cur- riculum director to help teachers at her campus implement a STEM-focused, collaborative teaching model that emphasizes involving grade-level teachers in active instructional team plan- ning as a means to enhance the quality and effectiveness of STEM-related teaching and learning in secondary classrooms. The principal recounted how, as part of her focused efforts to get to know her teachers during her first year at the campus and “to get a pulse” on the school’s teaching and learning environ- ment, she spent a good deal of her time engaging in unsched- uled, informal walk-throughs during individual teachers’ vari- ous classroom teaching periods followed by scheduled collegial conversations with each teacher. The principal explained that she emphasized to teachers that these informal walk-throughs and follow-up conversations were a way for her to: 1) observe student-teacher interactions in each grade level within specific content area classes; 2) become familiar with individual teach- ers’ classroom teaching styles; and 3) begin to develop an in- formed sense of the overall teaching and learning climate at the school. The principal noted that while a number of her teachers were open to her informal classroom observation and conversation strategies (as well as her interests in encouraging teachers’ col- laborative planning and integration of technologies into class- room teaching), some others were not. One veteran teacher in particular, the principal stated, was especially unappreciative of her instructional supervisory approach, and openly derided the new principal as being “intrusive” and “prone to meddling in teachers’ work”. This teacher, “Steve”, has been at this high school campus for fifteen years and also currently serves as the math department chairperson. The principal characterized Steve as a well-respected, long-time member of the high school teaching staff, as well as a sometimes outspoken and stalwart proponent of staunchly conservative educational values—val- ues grounded firmly in “traditional ways of doing things” that have been nurtured and reinforced over multiple generations in this tight-knit West Texas school district community. In es- sence, Steve’s educational beliefs centered around a “back-to- the-basics” approach to instruction, placing heavy emphasis on teaching essential content with “tried and true” teaching meth- ods, namely: classroom lecture/direct instruction, student math problem worksheets, and follow-up instructional intervention strategies for individual students when needed (typically, one- on-one diagnostic tutoring via additional problem-specific work- sheets). According to the principal, Steve has consistently opposed her efforts to encourage departmental faculty to work together to integrate available mobile technologies (such as ipads, ipods, and the like) into their classroom teaching. In addition, Steve is particularly adamant in eschewing requests from other faculty within his multidisciplinary STEM-teaching team to engage together with them in cross-content instructional planning, ar- guing that this kind of integrated team planning is just “too time consuming” and doesn’t really enhance classroom instruction. Steve’s passionate beliefs about teaching and the kinds of classroom learning environments that work best for secondary students emanate from his sincere commitment to his profes- sional teaching craft and to his students, and he is quite vocal in sharing these beliefs with teaching colleagues in the math de- partment as well as with other content area faculty throughout the campus. Several of Steve’s veteran teaching colleagues at this high school, in fact, share his views on teaching and in- structional quality, and also resent the district’s new interdisci- plinary team planning and technology integration initiatives as unwanted intrusions into their professional autonomy. More- over, the principal further explained, a lot of the “old guard” members of the community strongly support Steve and his Open Access 261  J. CLAUDET ideas about teaching. In fact, many parents whose families have been in the community for generations (a majority of whom attended school in this district and graduated from this high school) feel that Steve and other teachers with similar instruc- tional beliefs represent the exact kind of “quality teaching” that their children need. And these community members don’t un- derstand why Steve and other “valued teachers” at the school are being asked to radically change the way they teach. This clash of instructional values has even worked its way into dis- trict school board meetings, the principal added, since Steve and several of his like-minded veteran teacher colleagues are well-connected in the community and enjoy long-term friend- ships with many prominent community business leaders, some of whom are also current school board members. At this point in our conversation, the principal leaned back in her chair for a moment and stared pensively at an impressive array of curriculum binders and team planning guides filling one bookshelf on her office wall. Then, with a hint of frustra- tion in her voice but still exuding determination, she explained to me that she has spent considerable time in the past several weeks reflecting on what she believes, in her words, is a “po- litical impasse” existing among her faculty regarding instruc- tional change. Steve and several other veteran teachers’ impas- sioned ridiculing and rejection at recent campus faculty meet- ings of her efforts to encourage departmental and grade-level teams to move forward in their work to implement instructional team planning and mobile technology integration have served to frame in stark terms what she believes is the essence of this school community’s instructional improvement dilemma chal- lenge: a clash of conflicting teacher (and community stake- holder) beliefs at a fundamental level regarding the nature of instructional effectiveness and the purpose of instructional planning. This principal’s story of clashing educational beliefs and the accompanying sociopolitical turmoil spilling over into her school community regarding instructional change and teaching effectiveness resonated in my own mind with similar campus stories which I had heard over several years from other ele- mentary and secondary principals in the region. Her story, in fact, closely followed a pattern of recurring themes that typi- cally emerge in similar school communities centering around: 1) the “entrenched nature” of some educational stakeholders’ be- liefs about classroom teaching and learning; 2) a collective fear by teachers in general of “externally imposed” change initia- tives; and 3) the resulting resistance to change mentality that can ensue from these beliefs. Taken together, these themes serve to put into stark relief what are considered by many to be a set of “intractable roadblocks” that are often associated with the challenges of enacting successful school turnaround leader- ship and meaningful instructional improvement in elementary and secondary school communities. This story of heightened student learning challenges in STEM and related content areas, sociopolitical gridlock ema- nating from stakeholders’ conflicting teaching and learning be- liefs, and the pressing need for instructional change in a secon- dary school setting was one that appealed directly to my own interests as a “change agent leadership” consultant, and I read- ily agreed to begin working with this principal and her high school community stakeholders on their instructional change dilemma. Through my ongoing experiences in working with principals and teachers in several other school communities in the region, I was keenly aware of the need to immerse myself directly in the school’s instructional culture to learn as much as possible about the multiple educational beliefs and perspectives of the various role players (teachers, department chairs, instruc- tional support specialists, parents, etc.) who are so intimately involved in the day-to-day instructional life of the school com- munity. Thus, I proposed to the principal that I spend a few weeks at the school early in the fall sitting in on a number of teachers’ regularly scheduled departmental and grade-level ins- tructional team meetings as a means to get to know her teachers and their perspectives and to observe teachers’ daily conversa- tions and interactions during their instructional planning. The principal readily agreed to this plan of action and proceeded to arrange my schedule of on-site observations to take place in October of this same school year. What’s the Point of Teaming, Anyway? From my past experiences in working with educators at other regional campuses, I knew that sitting in on teacher team meet- ings and observing teachers interacting with each other during their daily instructional planning was an effective way to: 1) learn about teachers’ instructional practices; 2) glean important insights about teachers’ instructional values and beliefs; and 3) get an informed sense of teachers’ own perspectives regarding current campus and district improvement initiatives that they were being asked to implement. These kinds of informal, direct observations were essentially a great way to get a “pulse” on the overall professional learning climate existing on the campus. Using this informal observational method, I began attending se- veral grade-level team meetings at this high school campus in early October. One of the teams I observed early on was a ninth grade in- structional team. Like many teacher teams at this campus, this instructional team was comprised of educators with varied years of teaching experience, both in and out of the district. This ninth grade team consisted of Phil, a social studies teacher who has been teaching for eighteen years, the last ten of which has been in this district; Lois, a math teacher in her seventh year of teaching, and beginning her third year at this campus; Megan, a science teacher with three years teaching experience at this campus; and Kelly, a new literature and language arts teacher at this campus and district, who was beginning her sec- ond year of teaching. As part of the planning conversations at this instructional team meeting, Kelly shared with her team members some creative ideas she had been exploring about leveraging internet-enabled communication technologies to de- sign an “international learning project” for her ninth-grade stu- dents. The other team members listened attentively as Kelly ex- plained that this project idea would enable the team’s ninth grade students to learn and share broader “world-culture” per- spectives on their reading assignments through collaborating on book reading and creative writing critique project assignments with fellow students in Sydney, Australia—using the internet to engage in critical readings and discussions of literature. Kelly became quite animated as she talked about the prospect of util- izing wikis, blogs, RSS feeds, twitter, and other digital com- munication tools to broaden and enliven the interactive learning environment for her students. It was clearly evident that Kelly was a teacher who was already very familiar with using digital technologies as she described to her team the educational po- tential of leveraging internet/world-wide we b resources and so- Open Access. 262  J. CLAUDET cial media to motivate students to engage dynamically with other students to bring some 21st century learning excitement to the study of language arts and literature. Kelly’s enthusiasm was contagious, and other team members who had been listen- ing attentively congratulated Kelly on her creative instructional design thinking and began to offer their own ideas on how Kelly’s collaborative “international learning project” design might be potentially broadened to incorporate their own content teaching areas as well. After several minutes of open team conversation in reaction to Kelly’s international learning project ideas, Phil—the most experienced teacher on the team—who had been sitting quietly and pensively during this time, broke in with his own observa- tions: “I think Kelly’s project ideas are very creative and have some real potential for motivating our ninth grade students to get them excited about literature and sharing their critical reading with other students. And, I’m generally supportive of our team’s efforts to explore these ideas in our instructional planning. But, we’re talking about digital technologies, using wikis, blogs, social media, and so on—technologies that many of us are not very familiar with. I’m not comfortable enough yet with these communication tools to feel like I can confidently use them in my teaching. I feel like I, as well as other teachers like me, need some help to get up to speed on these tools to have the confidence to be able to use them effectively in the classroom.” As it turned out, Phil wasn’t the only teacher on this ninth grade team who was feeling some “technology anxiety”. Other teach- ers on the team were also feeling that they lacked the requisite knowledge and skills to be able to integrate digital technologies effectively into their classroom teaching. In fact, Phil’s com- ments triggered other team members to voice their own con- cerns about their lack of familiarity with many of these new digital learning tools. Lois, the team’s math teacher, offered her perspective: “You know, in the last couple of years the district has offered a few introductory staff development sessions for teachers on available content-specific internet resources, such as in math, science, and other content areas, that teachers can utilize to broaden and enrich their lesson planning. But, the kind of project Kelly is talking about is taking technology inte- gration [emphasis added] to a whole new level. How are we going to be successful in integrating these new digital commu- nication technologies into our instructional planning if we don’t have the required knowledge and skills?” Lois paused re- flectively for a moment as she surveyed the other members of her team, and then exclaimed: “Many teachers like myself are going to need some additional specific training to learn how to incorporate social media and digital communication tools into our teaching—tools that many of the kids in this school are already very comfortable with.” The team’s conversation ended with no clear sense of how to go about bridging the real gap between the “teaching and learning potential” of Kelly’s inter- national learning project instructional planning ideas and the “evident need” for more focused professional development for teachers in the area of technology-integrated instruction using digital technologies and social media. Following this ninth grade team meeting, I then sat in on an eleventh grade team meeting later on during the week. Interest- ingly, this eleventh grade team reflected rather well the mix of old and new instructional perspectives about which the princi- pal and I had talked during our preliminary meeting. This parti- cular eleventh grade faculty team consisted of two recent teacher hires, both new to the district and in their initial three years of teaching. One of the new teachers, Nick, is an enthusi- astic social studies teacher, who is beginning his third year of teaching at this campus, having moved to the district two years ago and hired by the former principal. Jocelyn, the other new teacher, is a science teacher in her second year of teaching, having been hired by the school’s current new principal just this past year. Teaching chemistry and physical science courses at this campus, Jocelyn is a science teacher with strong science educator interests in physical science, technology, and engi- neering design, and who is a strong advocate of building a ro- bust STEM-integrated curriculum—a curriculum that develops students’ critical thinking skills through focused STEM teach- ing. She is especially interested in brainstorming and discover- ing ways to creatively integrate Next Generation Science Stan- dards (NGSS) directly into her own classroom teaching and instructional team planning with colleagues. The other mem- bers of this eleventh grade team include Christie, a literature and language arts teacher with seven years of teaching experi- ence (three years at this particular campus), and who also serves as the high school’s director of student drama produc- tions, and Steve, a fifteen-year veteran math teacher and the current math department chairperson on the campus. At the outset of this eleventh grade team meeting, I listened attentively as Christie and Nick engaged in an enthusiastic discussion re- garding a creative plan put forward by Christie to perhaps work together to develop a “language arts/social studies” collabora- tive instructional unit around the idea of a “Readers’ Theatre”. Christie explained that she felt utilizing a “Readers’ Theatre” as a teaching and learning design format might be an effective way to creatively engage students in “active, immersive learn- ing” through involving them directly in dynamic reading and interactive role playing as complementary means to explore key concepts that Christie and Nick would be teaching during the upcoming nine weeks period. Christie also noted that she felt involving eleventh grade students in an experiential “Readers’ Theatre” environment would be a creative, practice-oriented way to provide additional “English language literacy” immersive- learning opportunities for the Hispanic students in their classes. It was apparent that both Christie and Nick enjoyed brain- storming creative ideas for potential new classroom teaching units and instructional strategies to better reach their students, and their dialogue on the possibilities of Christie’s “Readers’ Theatre” idea continued for several minutes as they explored various directions they might pursue in incorporating this col- laborative content idea into their team’s overall instructional unit planning efforts. Reacting to this conversation her social studies and language arts team colleagues were having regarding their creative plans to design a “Readers’ Theatre” instructional unit for students, Jocelyn, the second year science teacher, turned enthusiastically toward Steve, the team’s veteran math teacher, and stated: “Steve, what Nick and Christie are talking about—using a ‘Readers’ Theatre’ format to develop a collaborative instruc- tional unit in social studies and language arts—sounds great. I’m wondering if you and I could work together in a similar way to design a collaborative unit in science and math around the metric system? This could be a way for you and I to work together to develop an exciting unit to help our students learn how to transition naturally into integrated STEM thinking— through ‘putting the math in science, and the science in math’.” “As you know,” Jocelyn added, “the metric system is something our students need to become familiar with. We could incorpo- Open Access 263  J. CLAUDET rate using the metric system into some STEM-focused word problems that we could develop together to help students see natural connections in the areas of science learning and math application.” Steve, who had been diligently grading papers at the team table throughout the team’s discussion, looked up for a moment and then responded in a monotone voice, “I don’t teach the metric system, I teach Algebra. Anyway, if they don’t have it by now, they never will.” At this point, Christie, the literature and language arts teacher, who was also the group’s instructional team leader, looked worriedly at Steve and then turned her chair to face the members of her team directly and declared, “The stakes here are high! Our grade level team’s end-of-course test scores—in math and science as well as in other content areas—have to improve. The reason the district has mandated this ‘instructional teaming initiative’ is to ensure that teachers in schools throughout the district are motivated to engage actively in instructional planning for student learning improvement. Steve, I know change is hard. But, we’re all go- ing to have to learn how to do things differently if we’re going to improve the quality of instruction to meet our students’ needs.” Steve took some time to reflect on what Christie had just said, and then addressed the team: “I’ve been teaching here a long time; and, overall, my students have been pretty suc- cessful over the years. I don’t know why I have to change my teaching practices—practices that I have perfected over the years and that I have used effectively with my students. What’s the point of teaming, anyway? [emphasis added] This is just the latest ‘instructional fad’, and we all know how those come and go. This ‘instructional teaming’ initiative is just being pushed on us by administrators who don’t really understand the reali- ties of classroom teaching and don’t know what our students need to succeed.” “And, let me tell you something else,” Steve continued. “I’ve been talking with my friends on the school board about this ‘instructional teaming initiative’ our principal and the superintendent are advocating, and they are not at all happy about this either. These school board members are very supportive of the long-term teaching efforts of veteran teachers in this district and they want this kind of teaching—quality teaching that has been part of the tradition of excellence in our community for generations—to continue. They’ve told me they have some serious questions they are planning to bring up at the next board meeting regarding the value of the instructional changes that the superintendent has been implementing.” The other members of this eleventh grade instructional team stared silently at each other as they reflected on the implications of Steve’s comments. These two teacher teams were representative of the dynamic mix of instructional beliefs and educator interactions I was able to observe over a three-week period sitting in on multiple tea- cher team planning meetings at this campus. As had happened many times before in working with groups of teachers and ad- ministrators in other regional schools and districts in which I had served as an educational change consultant, through attend- ing these instructional team meetings I was able to collect im- portant first-hand observer information relating to: 1) teachers’ perceptions regarding current school and district improvement initiatives; 2) teachers’ individual and collective views regard- ing the perceived supportiveness of campus and district admin- istrators; and 3) teachers’ own professional sense (from their unique classroom and instructional planning perspectives) of what they felt were the realistic prospects for positive instruc- tional change and improvement on their campus. Moreover, this information provided an important backdrop to help me deve- lop a more complete, multi-layered picture of the sociopolitics of organizational change presently existing and evolving within this school and district community. My observations confirmed that there were definitely conflicting perspectives existing among teachers at this campus regarding a number of core areas of professional teaching practice, including: 1) the appropriate overall structure for classroom teaching and learning; 2) the purpose of instructional planning; and 3) the practical useful- ness of externally imposed school- and district-level change ini- tiatives and their impact on school improvement. These con- flicting teacher perspectives were all driven by deep-seated teacher beliefs about instructional quality, student performance, and organizational effectiveness that were held and espoused by individual teachers working within the grade-level teams I ob- served on this campus. Armed with these sets of observational data and organizational insights, I scheduled a follow-up meet- ing with the principal to share what I had learned and to plan next steps. Coming Together as a School-wide Community to Reassess the Purpose of Instructional Change As I began planning for my next meeting with the principal, I was very aware that I would need to not only report on my organizational analysis of the various faculty team interactions and related observational data I had collected over the previous three-week period, but also be prepared to offer this principal some concrete strategies on how to address the instructional malaise currently existing at this campus and to recommend a workable plan for moving forward. The principal at this high school had already been expending considerable time and effort over a period of several months to encourage her teachers to realize the need for change in their instructional planning and to motivate them to work together as grade-level teacher teams to embrace the district’s instructional improvement initiatives. But, as the principal had made resoundingly clear to me at our initial meeting, the increasing student diversity at this high school campus, in conjunction with the nature and complexity of tea- chers’ multi-generational beliefs about classroom teaching and learning and some teachers’ adamant negative views regarding the “improvement potential” of the change initiatives themselv- es, were combining to form major roadblocks inhibiting her efforts. I would need to provide this principal with some new creative strategies that could be genuinely useful to her and the school community’s stakeholders in helping to break down the organizational gridlock that had stymied instructional improve- ment at this campus thus far. As part of my data collection activities at this campus, I had learned that during the past two years the school had been en- gaging in a number of potentially worthwhile, albeit disjunctive and disconnected, staff development emphases. A variety of in- dividual staff development “events” were planned and sched- uled at different times during the school year by the school’s Campus Improvement Team (CIT)—a school-wide team con- sisting of department chairs and teacher representatives from each grade-level instructional team. This CIT group identified staff development topics for the upcoming year’s series of quar- terly staff development offerings through surveying faculty in the spring to identify teacher interests and topic area recom- mendations. At the time of my consultant work at this school, the slate of staff development events included program topics Open Access. 264  J. CLAUDET focused on such things as “teacher stress and wellness”, “bul- lying prevention”, “remediation strategies”, and the like. While these topics were certainly worthwhile in terms of the individ- ual professional learning content they could provide, I quickly pointed out to the principal that, in my estimation, these kinds of “stand-alone” staff development offerings were disjunctive at best and were providing only surface-level content informa- tion to teachers. Most importantly, these staff development to- pic selections were certainly not doing anything to address in any coherent and systematic way the deep-structural organiza- tional and instructional change issues that stakeholders at this campus were currently grappling with. As the principal and I continued our conversation, I emphasized to her that based on my overall analyses of the school’s performance data and the collective observational notes I had compiled, teachers, admin- istrators, and community members at this high school were struggling with a number of interrelated systemic challenges, including: 1) the increasing student population diversity at this school and throughout the district which was presenting new (and difficult) instructional planning and student learning sup- port challenges for teachers; 2) coping with the accountability pressures resulting from the state’s new, much more rigorous End of Course (EoC) exams and the district’s new instructional improvement initiatives in response to these increased student performance demands; 3) teachers’ multiple perspectives regar- ding instructional planning and technology integration—fueled, in some cases, by teachers’ longstanding, entrenched beliefs re- garding teaching and learning, their roles as classroom teachers, and the nature (and limits) of instructional effectiveness; and 4) the fomenting anger and disgruntled reactions of multiple stake- holders and stakeholder groups both within the high school and throughout the district who were becoming more forceful of late in voicing their strong objections to the district’s change and improvement initiatives—initiatives which, in their view, were unnecessarily disruptive and which were undermining the history of instructional excellence that has been a longstanding source of pride within this district community for generations. Collectively, these systemic challenges were creating a hotbed of sociopolitical instability within this campus community. This instability was contributing to and exacerbating a dysfunc- tional professional and community-wide educational environ- ment that was effectively creating an impassable roadblock to any meaningful instructional change and improvement. The principal agreed with my organizational assessment and readily acknowledged that a new, more targeted approach to the prob- lem was needed. Following an approach I had been utilizing in my consulting work with several other schools and districts in the region who were grappling with similar organizational change and im- provement challenges, I shared with the principal my experi- ences in using future search meetings as a means to bring to- gether multiple stakeholders throughout an organization—par- ticularly an organization that is experiencing internal conflict and whose members are having difficulty identifying and im- plementing workable strategies for addressing needed organiza- tional improvement. These future search events are adapted from “future search conferences” which are often used in cor- porate settings as a structured means to enable organization stakeholders to engage in open, reflective group conversations to: 1) assess their organization’s history; 2) examine multiple stakeholders’ perspectives on the organization’s present per- formance; and 3) construct a communal vision grounded in real-world strategies of a preferred future direction for the or- ganization that can ensure the organization’s continued com- petitive advantage and optimal growth. Importantly, future search meetings can “enable organizations and communities to learn more together than any one person can discover alone through bringing the ‘whole system into the room’, [to make] feasible a shared encounter with complexity and uncertainty leading to clarity, hope, and action” (Weisbord & Janoff, 2010: p. 4). Due to the entrenched and politically charged nature of the multiple stakeholder perspectivist conflicts existing at this campus (as well as throughout the district), I knew I would need to adapt and customize a series of future search meetings for this campus in very specific ways if they were to be genu- inely useful to the educational stakeholders at this campus and within this school district community. Given the limited suc- cess of this principal’s recent change leadership efforts and her negative experiences involving some teachers’ and other com- munity stakeholders’ entrenched attitudes at her campus, the principal was understandably skeptical about the prospects of the future search meetings idea for positively addressing the instructional gridlock existing at her campus. But with hope in the possibility of change and a willingness to support any effort that could potentially bring about meaningful instructional im- provement on her campus, she agreed to convene a meeting of the school’s Campus Improvement Team (CIT) the following week so that I could present the future search meetings idea myself to the school’s leadership team. As I anticipated, the Campus Improvement Team shared the principal’s skepticism about my future search meetings pro- posal and expressed their concerns about involving teachers in “yet more meetings and additional work” on top of their already demanding classroom teaching and grade-level team planning responsibilities. To underscore the point, one CIT member ref- erenced an incident that had just occurred at the most recent school board meeting the past Monday evening. At this board meeting, which was widely attended by a variety of local community members (parents and area business leaders, as well as a large contingent of the district’s teachers), tempers had evidently boiled over during some verbal interchanges that occurred between school board members, district leadership, and some community members in attendance regarding the dis- trict’s new change initiatives. As this teacher recounted the event, stakeholder perspectives were in sharp contrast at the board meeting as some board members siding with vocal com- munity members took the floor at the meeting to voice in no uncertain terms their adamant opposition to the instructional teaming and related district “instructional improvement” initia- tives the superintendent and the district leadership team were implementing. These school board and community members were intent on making it clear that they considered these new initiatives to be misguided change efforts that were being forc- ed on teachers by an out-of-touch superintendent and central office staff who did not fully understand the instructional reali- ties of classroom teaching or the legitimate professional support needs of the district’s teachers. In response to this teacher’s report, I used this new information to impress upon the CIT group and the principal the even greater sense of urgency this turn of events signaled within their school community on the need for the school’s leadership team to make some proactive move to demonstrate that they were actively addressing stake- holders’ concerns and were working to move their school com- munity forward in a positive way that would be best for all Open Access 265  J. CLAUDET concerned—especially, for the students. After some further in- tense discussion among CIT members, the principal, and my- self, in which these campus leaders considered the implications of these latest school board clashes which clearly reflected the escalating stakeholder tensions within the community and the increasingly unstable instructional climate across the district, the group conceded, albeit reluctantly, that they had exhausted their ideas on how to address what had now clearly become an intractable instructional improvement dilemma at their campus. In view of the evident need to find creative ways to address their school improvement challenges, CIT members agreed that it was in their best interest to embrace any new creative strate- gies available that might have potential for helping school stakeholders tackle their school’s instructional challenges and move their school community forward. I readily seized this opportunity to share with this high school CIT group my successful experiences over the years in utilizing the future search meeting process in several other schools and districts within the region. As I explained to these high school campus leaders, the power of the future search process is in leveraging this open meeting format as a means to bring multiple stakeholders together within a school community in a non-threatening way to review their organization’s rich his- tory and accomplishments, to explore the changing conditions and events that have combined to help create their present or- ganizational reality, and to openly share stakeholder perspec- tives on their school’s current instructional challenges. I em- phasized that, if engaged in properly, these community-wide future search conversations can serve as an initial useful spring- board for identifying commonalities in stakeholder thinking— which can become an important foundation to support school stakeholders’ subsequent extended efforts in building organiza- tional cohesiveness and eventually arriving at shared consensus on how best to move their school community forward. With some anxiety about the unknown, but with determined hope and a firm commitment to explore this new possibility for posi- tive change, the members of this school’s campus improvement team agreed to work with the principal and myself in planning and scheduling a series of future search meetings to take place at this high school during the winter months of the current school year. On my recommendation, participants in the future search meetings included representatives from all major constituent groups involved in this high school community, and consisted of the following stakeholders and stakeholder groups: 1) several parents of current high school students, some of whom were elected parent officials serving on the school’s parent-teacher organization (PTO); 2) an expanded Campus Improvement Team (consisting of the various grade-level department chair- persons, plus five to seven teacher representatives from each grade level); 3) the school principal and two assistant principals; and 4) the school district’s assistant superintendent for curricu- lum and instruction, along with instructional specialists and other central administration staff members from the district cen- tral office. Because of the large number of stakeholder partici- pants involved in the search conference meetings, the meetings were held in the school’s expansive cafeteria, with the school library and nearby classrooms used for breakout sessions. As the school’s organizational change consultant, I served as both conference facilitator and process observer for the series of three future search meetings that was conducted at this campus in January and February. The series of three day-long future search meetings was or- ganized into two parts: Part One was delivered on “Day One” and focused on exploring the history and development of the school community; Part Two encompassed “Day Two” and “Day Three” of the future search meetings and was devoted to examining the school community’s present overall organizatio- nal environment and the instructional challenges the school was facing. Each of the all-day meetings was structured to include a number of “full group” sessions interspersed with smaller “break- out” sessions to facilitate further brainstorming and informal discussion among smaller groups of participants. Fully aware of the volatile nature of the political climate existing in the district and the intensity of the perspectivist views held by many stake- holders regarding the district’s instructional change initiatives, I emphasized at the opening of the first future search meeting that the purpose of these meetings was not for stakeholders to be critical and/or judgmental of each other, or even to attempt to arrive at definitive sets of school leadership action strategies, but to use these meetings as creative opportunities for stake- holder participants to explore each others’ educational beliefs and perspectives (including differences) regarding their school community, and from this beginning to explore and identify potential commonalities (i.e., areas of agreement in educational values and beliefs) in their thinking. “Day One” of the future search meetings focused on encour- aging participants to explore the rich history of their school community organization—and, particularly, to listen to and in- ternalize this history as related through the multiple lenses and perspectives of the diverse stakeholders and stakeholder groups that were and are an integral part of the school’s communal fa- bric. As school consultant and facilitator for the future search meetings, I took special care during this important “Day One” meeting to encourage each participant (parents and other com- munity members, teachers, administrators, etc.) to contribute their own perspectives and stories to help create a rich, multi- dimensional “composite picture” of the historical journey these school community stakeholders have taken and experienced to- gether over the years. I was particularly interested in assisting participants in developing a broad understanding of the multiple contributions various stakeholders and stakeholder groups have made to the school community over many years, in order to help participants develop a larger “communal sense” of the multi-dimensional, shared history of the organization. This “Day One” future search work provided an important founda- tion for the subsequent “Day Two” and “Day Three” future search meetings which were devoted to examining the school’s present organizational environment and the challenges school community members were currently facing. As I had anticipated, it wasn’t long into Part Two of the fu- ture search meetings before the major topic on participants’ minds—the highly contentious district “instructional teaming” initiative—took center stage in the discussion. It was during the second and third days of the future search meetings that the political tensions percolating throughout the school and district community began to spill over into the future search meetings and infiltrate into full-group discussions. As it turned out, sev- eral of the school’s teachers had come to these future search meetings fully prepared and eager to share their views on the district’s instructional teaming/campus learning improvement initiative. During the final “Day Three” meeting, one veteran teacher (one of the most experienced educators in the district who has been teaching at this high school for almost two dec- Open Access. 266  J. CLAUDET ades) took the floor during one of the full group sessions to vent her anger at district and campus administrators for their “heavy-handed implementation tactics” and “callous disregard” for the professional autonomy of teachers—particularly, teach- ers who “have been teaching effectively in this district for many years”. Relishing this opportunity to address the full group, this teacher openly voiced her concerns about what she perceived to be an ill-conceived and misguided initiative: “You all know me well. I grew up in this community, went through this school system as a youngster, and as an educator I’ve been teaching here in this district—and at this high school—for many years. And, you all know that I’m usually very up-front in making it known how I feel about things, especially when it comes to what’s needed to ensure quality instruction for the students of this district.” The full group of future search participants— teachers, administrators, and parents assembled in the high school’s cafeteria—were listening intently as this veteran tea- cher continued, “The teaching strategies many of us have been using consistently in our classrooms over the years have been very effective in helping the students in our community be suc- cessful, from one generation to the next—and these same tea- ching strategies are exactly the ones we should be continuing to use today. You do n’t change tried and true instructional strate- gies just because central office administrators are feeling in- creased student performance accountability pressures from the state. The best way to address the state’s performance ac- countability demands is to provide teachers with additional classroom aides and other kinds of instructional resources to make sure we have the ongoing support we need to continue our present efforts in our classrooms. We don’t need instruc- tional change, we need instructional support!” The reaction from meeting participants to this veteran teacher’s impassioned rhetoric was palpable as several groups of teachers and parents sitting at small-group tables across the cafeteria meeting room could be seen nodding to each other and echoing their agree- ment with this veteran teacher’s views. After a few moments of nervous fidgeting throughout the conference room, the district’s assistant superintendent for secondary instruction, who had been in attendance through all three days of future search meeting events, stood to address the full group. Stakeholders in the room turned in her direction as she spoke, “I’ve been privileged to be able to attend these three days of future search meetings, and I’ve been listening very attentively to the perspectives that many of you have put for- ward here regarding the quality of teaching and learning in our classrooms and the excellent efforts of teachers both at this high school campus and throughout the district who have been working tirelessly to continue the tradition of educational ex- cellence our district has been justly known for over the years. And, this spirit of instructional leadership and commitment to quality teaching and learning effectiveness is something that all of us in our school district community should rightly celebrate and be very proud of. This is a touchstone of excellence and pride that those of us who are educators and school adminis- trators, as well as those of us, myself included, who are parents of children attending our schools can all draw inspiration from as we look toward the future [emphasis added]. This focus on the future will be especially important as we continue to work together to find new, creative ways to address the real present and future learning challenges of our diverse student popula- tions and their learning needs .” A hushed silence permeated the conference room as future search participants listened atten- tively as this district instructional leader continued to address the full group: “The present reality,” the assistant superinten- dent proclaimed (pausing briefly to highlight her point), “is that the students in our school district community have changed. Our student populations have become much more diverse, and the students sitting in our district’s classrooms today come to us with different cultural heritages and backgrounds—and also with different kinds of learning needs and challenges. And, as educators, our job is to provide all of our district’s students with the appropriate kinds of instructional support they need to be successful. But, we will have to think differently and work in new ways to leverage new 21st century teaching tools and technologies that are available, and put in place the right kinds of instructional support programs to meet our students’ needs. And, in order to do all of this, we’re all going to have to work to reinvent ourselves as instructional leaders [emphasis added]. We will all need to learn how to work collaboratively in new ways to be able to examine effectively our students’ individual learning needs and to make data-driven team decisions that enable us to make informed choices on the appropriate mix of instructional tools and support strategies that will ensure that our district’s celebrated tradition of teaching and learning excellence will continue.” The assistant superintendent con- cluded her remarks by stating emphatically, “Our unwavering commitment to instructional quality has not changed. But, we as instructional leaders will need to change! [emphasis added] We will need to change how we think about instruction, how we select the kinds of instructional tools and strategies that we use, and how we leverage these tools and strategies to work to- gether in new and more effective ways—in order to continue to provide that level of classroom teaching and learning effec- tiveness and quality instructional support to our students that is the hallmark of excellence in our district.” As a final full-group task to culminate the series of three day- long future search meetings, participants were asked to collabo- ratively review the various perspectives that were articulated by stakeholder participants during the future search meetings and generate a summary list of shared “common perceptions” regar- ding the organizational realities and challenges facing the high school and school district community. The “common percep- tions” that were generated by future search meeting participants included: 1) a broader recognition of the systemic impact of the demographic changes that have irreversibly altered the makeup of the student populations being served within this school and district community; 2) a more focused realization of the kinds of complex challenges involved in planning for and delivering quality classroom instruction to diverse student learners, par- ticularly in STEM content areas; 3) a better grasp of the perva- sive feeling held by a majority of teachers at this high school that they are ill-equipped to learn about and use digital tech- nologies in their own teaching; and 4) a new, collective recog- nition among participants that the intense, multi-stakeholder perspectivist conflicts and resulting sociopolitical gridlock cur- rently affecting this school and district community was not sustainable, and that new creative ideas on how to bring about meaningful organizational change were needed. This final list of “common perceptions” which these future search partici- pants generated reflected well both the nature and extent of the instructional dysfunction existing within this high school and district community, as well as participants’ evolving collabora- tive insights—as a communal group—on the compelling need for a major shift in their collective thinking regarding the pur- Open Access 267  J. CLAUDET poses of organization-wide instructional change. The culminating sets of “communal perceptions” and “col- laborative insights” generated by meeting participants as a re- sult of the collective future search activities conducted at this high school campus provided the necessary frame for me, working as the school’s organizational change consultant, to propose to these stakeholders an alternative approach to ad- dressing their dilemma situation—an approach that thus far they had not yet considered. This alternative approach would involve stakeholders becoming immersed in the realities of school change leadership in a radically new way—as a multi- media case learning team investigating anew their school com- munity’s organizational challenges as a “school leadership mo- vie production crew”. After much further discussion (including the airing of anxieties about the prospects of embarking on an “unknown adventure”), these education stakeholders—empo- wered by their future search meeting efforts and exuding a re- newed, resolute commitment to look toward the future—de- cided to take up my challenge. Embracing a New Focus on Organizational Learning… Lights, Camera, Action! Organizational case production efforts completed at this high school campus followed the design of similar sets of organiza- tional cases that were developed and produced over a ten-year period in participating schools and school districts in the West Texas Permian Basin and Texas Panhandle regions. These case production activities were part of a decade-long research and development project to investigate the use of multimedia or- ganizational case methods as a creative tool to assist school stakeholders in implementing collaborative change leadership practices in school communities experiencing tough, real-world school leadership dilemma challenges. The multi-year project research and development work conducted at these regional schools was made possible through initial funding in 1996 through 1998 (totaling US $400,000) provided by the Sid W. Richardson Foundation (Fort Worth, Texas), the Abell-Hanger Foundation (Midland, Texas), and the Franklin Charitable Trusts (Post, Texas). This initial funding provided support for the creation of a school leadership multimedia case production research and development lab housed in the College of Educa- tion at Texas Tech University. This R&D lab was equipped with sets of betacam SP cameras, audio mixing and dubbing equipment, and nonlinear digital video and audio editing hard- ware and software to support multimedia case filming and post- production work. Researchers and multimedia specialists in digital video filming, audio mixing, and multimedia post-pro- duction were key members of a university research team who worked closely with school stakeholder case development teams at individual schools participating in the funded project’s over- arching university—K-12 collaborative partnership design. A unique feature of the organizational case development pro- ject work undertaken at the high school profiled in this report (as well as with similar case development efforts completed at other schools and districts throughout the region) was in the use of multimedia case learning as an alternative approach to per- sonnel staff development and school stakeholder organizational learning. This approach centered on immersing multiple school community stakeholders directly in the critical examination and reflective analysis of their own context-specific organizational dilemma situation through involving stakeholders as collabora- tive developers and producers of a “multimedia case” about their own lived school community dilemma experiences. As part of production work, school stakeholders participating in case development activities became immersed together—as mo- vie production crew collaborators—in developing dynamic multimedia portrayals of stakeholders’ multiperspectivist con- flicts surrounding key case issues that were fueling their school community’s organizational dilemma. This collaborative im- mersive learning aspect of the project’s organizational case learning design directly parallels and reflects the intense kind of “creative immersion” experienced by movie production crews on location as they are engaged in “scene shoots” and related scene editing and production act ivities. Case production work at this high school began in earnest in the spring of 2008. Beginning in March, campus-based produc- tion team members (consisting of thirty stakeholders directly involved with this high school community and its organizatio- nal and instructional change challenges—teachers, grade-level department chairpersons, campus administrators, central office instructional specialists, and parents) worked closely with uni- versity multimedia production team specialists to begin the pro- cess of “storyboarding” the organizational case and developing detailed interactive scripts for individual case scenes. Because of the intense nature of the perspectivist conflicts existing be- tween and among various stakeholders and stakeholder groups regarding the instructional change initiatives taking place at the high school, university production specialists spent a great deal of time early-on within initial case development project activi- ties coaching campus stakeholders on how to adopt a proactive critical reflective stance toward their case storyboarding and scene scripting efforts. Campus-based stakeholder team mem- bers were encouraged to strive for perspectivist accuracy and detail in the development of their preliminary “case storyboard” depicting the evolution of important aspects of their “organiza- tional leadership case”. As stakeholder team members proceed- ed to work on developing and refining individual case scenes, campus stakeholders (with assistance from university produc- tion specialists) spent a great deal of time engaging in open cri- tical review and discussion of multiple iterative drafts of indi- vidual case scenes depicting decisive interactive encounters be- tween various stakeholders holding competing views regarding case challenges. The goal of these activities was to develop a set of well-crafted case scenes and scene scripts that accurately captured the dynamic nature and contextual depth of the mul- ti-perspectivist organizational dilemma situation which these campus stakeholders were actively experiencing and were so directly involved in within their school and district community. Storyboarding and case scenes development work was com- pleted by the end of May. The next phase of case production work involved campus stakeholders directly in the actual stag- ing and filming of individual case scenes. Case scene filming was conducted during the summer months of June and July at the high school campus. Importantly, as a creative way to ex- pand and deepen stakeholders’ inclination toward sustained critical reflective thinking during this phase of case production activities, individual stakeholders were directed by university production specialists to select and assume different roles than their “real-life” stakeholder roles for the purposes of case film- ing. For example, individual stakeholders who were teachers in their “real-life” organizational roles assumed other stakeholder roles (such as campus-level administrator or parent) in “acting out” various case production scenes. Doing this forced stake- Open Access. 268  J. CLAUDET holders to think deeply and critically about the perspectives and beliefs of “other” stakeholders regarding the school commu- nity’s instructional change initiatives. Interestingly, this role- swapping strategy triggered multiple spontaneous events during scene film shoots in which one or more of the campus-based production team “stakeholders-turned-actors” would become agitated and repeatedly call for time-outs within a particular shoot in order to coach their fellow actors on the “correct” in- terpretation and delivery of their own real-life stakeholder per- spectives—perspectives which they insisted their stakeholder- actor colleagues were not projecting correctly. These kinds of impromptu peer coaching sessions occurred throughout the filming of the case’s multiple scenes and they were recognized early-on by university production specialists as important or- ganizational learning opportunities for campus stakeholders participating in the overall case production immersive experi- ence. In addition to the filming of various case scenes, campus stakeholder production team members were also involved in developing a number of important multimedia databases that would become part of the completed multimedia case. These databases included information files presenting multi-year overview summaries of such things as: 1) the high school’s student population demographics; 2) grade-level and school- level profiles of student academic performance scores; 3) stu- dent progress monitoring and intervention data; and 4) detailed descriptions of the instructional improvement initiatives that were being implemented at the school. Finally, several campus stakeholder production team members also participated in the filming of a number of Reflective Decision Making video seg- ments that were incorporated into the overall organizational learning design of the multimedia case. These video segments highlighted conversations among multiple school leadership experts (regional Education Service Center school improvement consultants, secondary school association state-wide executives, seasoned administrative and instructional leaders from school districts across the state, etc.) who were invited to review the case scenes and databases and provide their “expert panel per- spectives” on the context-specific organizational change lead- ership challenges portrayed in this high school multimedia case. As part of their case review, these experts were encouraged to share their real-world insights on potential collaborative lead- ership strategies that could be adapted and employed by stake- holders in the case situation to creatively address this high school’s leadership challenges and help move the school com- munity forward. Multimedia Case Design Elements Project designers and multimedia specialists working over many years in collaboration with multiple groups of school stakeholders have developed an interactive navigational design template for the multimedia cases which have been produced at the various school campuses involved in the project, including the high school instructional leadership case highlighted in this article. The various components of this navigational design template were developed to create an overall multimedia case analysis and decision making environment within which school educators and associated school community stakeholders could work together as a team to: 1) review the overall dimensions of their school’s current instructional leadership and organiza- tional improvement challenges; 2) easily access and examine case-specific school accountability data and related resource information pertaining to the campus (including Public Educa- tion Information Management System [PEIMS] data and Aca- demic Excellence Indicator System [AEIS] student performance information from the state-level Texas Education Agency [TEA] school performance accountability databases); 3) view, criti- cally analyze, and discuss multiple case scenes depicting inter- active encounters between key stakeholders and stakeholder groups harboring conflicting beliefs and perspectives regarding their school’s improvement challenges; and 4) deliberate on the merits of possible sets of short- and long-term action strategies that could be implemented to effectively move their school community forward. The project’s multimedia case design template incorporates a number of interactive elements. These design elements are illustrated in Figures 1 through 5. The overall multimedia case design employs a “school leadership office” visual metaphor as the interactive interface for case users (Figure 1). This school leadership office serves as the interactive team-learning envi- ronment and digital portal within and through which school stakeholders can access and examine multiple school docu- ments such as curriculum maps, instructional planning summa- ries, progress monitoring and intervention records, grade- and school-level student performance files, and other databases relating to the case dilemma situation. School stakeholder teams can utilize the interactive links embedded in this school leadership office environment to: 1) review student demo- graphic profiles and personnel staffing information for the campus; 2) examine multi-year school accountability summa- ries and related database information on aggregated and disag- gregated student standardized test performance data; 3) view individual multimedia case scenes; 4) interact online with team colleagues, district administrators, and Education Service Cen- ter (ESC) program specialists and consultants about case details; 5) analyze selected video frame segments of individual case scenes and store their team’s video segment written reflective analyses in a digital case analysis program archive; and 6) lev- erage all available case information files and databases in con- junction with team case scene analysis results to propose, dis- cuss, and finalize detailed sets of short- and long-term action Figure 1. Navigational design template featuring “school leadership office” in- teractive team-learning environment and multiple resource database links. Open Access 269  J. CLAUDET Figure 2. Case video scenes database area incorporating “video mark” frame ana- lysis function. Figure 3. Individual “video marked” scene frames and scene frame sections selected for further case team analysis. Figure 4. Case reflective analysis area showing specific examples of school case team members’ comparative cross-scene “video mark” analyses along with school leadership perform ance standards sorting functionality. strategies to address their school community’s specific im- provement challenges. Case users can access, load, and view the school leadership case’s multiple digital video case scenes in the Case Video Figure 5. Case reflective decision making area presenting mul- tiple “expert panel” video segments for case team re- view. Scenes Database area (Figure 2). Each scene portrays one or more critical incidents identified and developed by the educa- tors and community stakeholders working together as members of the school-based “multimedia case development team”. These critical incident scenes take the form of scripted interac- tive encounters between multiple school stakeholders and stake- holder groups who hold conflicting beliefs and perspectives regarding the school’s instructional improvement challenges. Importantly, through portraying in sharp relief the multiple beliefs and perspectives of stakeholders within the school situa- tion and how stakeholders’ beliefs and perspectives clash on central case issues, these scenes are able to shed light on how these stakeholder conflicts are contributing directly to expand- ing and intensifying the sociopolitical turmoil that is fueling the school community’s instructional leadership dilemma. Stake- holder team members can utilize the “video mark” frame analy- sis function incorporated into the multimedia case interactive design to assist them in identifying and “digitally marking” specific portions of individual video case scenes for further team analysis (Figure 2). This “video marking” capability al- lows users to select specific “scene frames” and “scene frame sections” within individual case scenes, which users can then examine and discuss in detail with their case team members (Figure 3). The “video mark” function is particularly useful in enabling team members to examine specific nuanced details of role players’ interactions within individual scene segments, and how stakeholders’ belief conflicts and related perspectivist clashes are contributing to the intractable nature of the situation. Working together as an analysis team, school stakeholders can then generate written summary critical analyses of their “video marked” scene frames and scene frame sections and save these team analyses in the multimedia program’s case analysis ar- chive files. School stakeholder teams can further expand their analyses of the multi-perspectivist, sociopolitical dynamics of the case situation through engaging in comparative cross-scene analyses of multiple critical incidents in the multimedia case design’s Reflective Analysis area (Figure 4). Within this area, team members can sort and organize their accumulated “video mark- ed” scenes and accompanying written reflective analyses into specific “school organizational leadership” domain areas (i.e., programmatic, contextual, functional, interpersonal)—critical areas of school collaborative leadership practice identified in Open Access. 270  J. CLAUDET state and national school leadership standards. These compara- tive cross-scene analyses enable school stakeholder teams to carefully examine observable patterns in stakeholders’ school community behaviors and actions across the overall timeline and trajectory of the school case situation, including allowing team members to engage in standards-informed discussions to pinpoint strengths and weaknesses in stakeholders’ collabora- tive organizational leadership and decision making. In addition to these kinds of reflective analyses of interactive behaviors and actions that are portrayed within and across multiple case scenes, school stakeholder teams can also engage in various advance consequence analyses focused on brainstorming and discussing multiple “what-if scenarios”—that is, potential al- ternative (and more positive) situational outcomes that might have been realizable under different conditions influenced by different sets of stakeholder beliefs. As case team members work together to develop their individual scene and compara- tive cross-scene analyses, school stakeholders have access to the full array of case-specific digital databases and information resources available within the overall multimedia case-learning environment. Finally, school stakeholder teams can synthesize and lever- age their collective case scene reflective analysis discussions to inform their team-centered strategic leadership action planning within the multimedia case’s Reflective Decision Making area (Figure 5). Within this area, school stakeholder teams can re- view several multiple “expert panel” video segments led by groups of K-12 education consultants and seasoned school community leaders who share their perspectives and insights on the school dilemma challenges portrayed in the multimedia case. Through studying these “expert panel” segments, school case team members can glean important additional insights from experienced education leaders regarding specific leadership dimensions of their case situation, including insights on various “organizational impact factors and implications” that should be considered when engaging in collaborative school leadership decision-making (such as: understanding the importance of “data-informed, comprehensive planning” to guide school re- newal; avoiding common school improvement “decision-mak- ing pitfalls”; managing and optimizing school-community “multiple stakeholder communications” to positively support the ongoing school change and improvement process; etc.). Case team members can leverage the real-world school leader- ship insights provided in these “expert panel” video segments to further inform and refine their own collaborative efforts as they work together to generate detailed sets of short- and long- term action strategies to move their school community forward. The above design elements were incorporated into the mul- timedia case interactive design to enable case users as a school leadership team to focus directly on: 1) exploring both the “macro” and “micro” organizational and sociopolitical aspects of their school leadership dilemma situation, with special atten- tion to examining the multiple dimensions and underlying root causes of their school dilemma situation; 2) examining the nu- anced interactive dynamics of stakeholder belief conflicts and how these conflicts were contributing to and deepening their school community’s overall dilemma situation; and 3) utilizing their own case scene analyses to “reframe” and “recalibrate” their school leadership and improvement thinking based on new team-centered insights and shared understandings to generate realistic, implementable sets of school improvement action stra- tegies. In combination, the above multimedia case design ele- ments provided these high school community stakeholders (turned case production team members) with a new set of case- specific digital tools and resources to assist them in exploring how to think differently and work together in new ways to de- velop their own collaborative teaming and school improvement decision making capacities. Discussion The multimedia case production and analysis project efforts detailed in this report engaged multiple groups of school com- munity members, multimedia production specialists, and school improvement researchers in collaborating together in a unique way to address the instructional change and improvement di- lemma challenges confronting educators and other key stake- holders in this West Texas high school community. The cumu- lative production team efforts of participants involved in this project resulted in the generation of a number of key insights regarding the viability and usefulness of multi-entity, collabo- rative teaming designs and multimedia-integrated organizatio- nal case learning tools for assisting school community stake- holders in: 1) reframing and refocusing their real-world school leadership dilemma challenges in ways that can facilitate data- informed, actionable decision-making; and 2) learning how to work together more creatively and effectively as organizational leading and learning teams. These insights are highlighted and discussed below. The Organizational Case Learning Project’s Multi-Entity, Collaborative Design Expanded the Prospects for Meaningful Organization-Wide Learning and G enera ted Ne w Insights among Participants Regardin g the Nature of Organiz ational Change Leadership. Multimedia case development efforts reported in this article utilized a funded project “multi-entity cluster design”. This col- laborative design set the stage for and enabled multiple groups of stakeholders representing several education entities (a high school campus and associated school district community, a state university, and a regional education service center) to come together to address the real-world “problems of practice” challenges of K-12 educators and community stakeholders in a highly immersive and intensive organizational case learning project environment. Certainly, the high school teachers and administrators, parents, business leaders, and district central office personnel involved in this high school campus case deve- lopment effort were presented with new opportunities for inter- acting and learning together in a different kind of collaborative learning enterprise. But, the case development project’s colla- borative design also enabled the direct involvement of multiple higher education faculty and specialists working in a number of different areas within a university (i.e., curriculum and instruc- tion; school leadership and improvement; adult learning; com- puter technology; dramatic arts and theatre; sociology; organ- izational communication), as well as engaging the expertise and contributions of math and science instructional content and staff development specialists from a regional education service cen- ter. The K-12 school district-university-service center multi-en- tity partnership design of this project was widely perceived from the very beginning of funded project efforts as a unique way to bring together diverse educators and researchers with multiple specializations to collaborate in new ways to investi- Open Access 271  J. CLAUDET gate and seek creative solutions to deeply entrenched problems of K-12 school leadership practice. Similar to the way a Kand- insky painting brings together many different colors, hues, and shapes and juxtaposes them in unfamiliar ways to engender in- triguing new visual insights and meanings, the multi-entity partnership design of this case development project enabled project participants to “team together” in non-routine ways that generated new opportunities for: 1) critically examining multi- ple sets of relevant school case data; 2) engaging in rich colle- gial conversations about this high school community’s organi- zational change and instructional leadership challenges; and 3) sharing and discussing stakeholders’ multiple case analysis per- spectives and insights—including collaboratively brainstorming and deliberating on multiple “best-scenario” school improve- ment decision making options. One important insight regarding the “organizational learning potential” of case production activities that emerged from pro- ject work was the realization that the quality and depth—as well as sustainability—of the project’s multimedia case devel- opment “process” and “products” (and the impact of these on participants) were magnified significantly as a direct result of the multidimensional nature of the interactions occurring among participating stakeholders and organizational entities. Many of the education stakeholders involved in the project noted that this was their first experience in collaborating to- gether so intensively within this kind of multi-entity design. The diverse kinds of stakeholders and stakeholder groups par- ticipating together in project activities infused the combined project teams’ case analysis reflective conversations with an added richness and depth that would not otherwise have been possible. These conversations facilitated a cross-pollination of creative ideas across multiple perspectives and engendered new, deeper kinds of organizational insights. This kind of involve- ment in multi-stakeholder, cross-pollinating conversations about real-world dilemmas of practice and how to solve them became “infectious” and “exhilarating” for those participating, and be- came a catalyst for engaging school community team members in ever-deeper conversations about the nature of organizational change and instructional leadership in schools. These conversa- tions challenged and empowered stakeholder participants to ex- plore new ideas, to investigate new avenues of change agent thinking, and to push the boundaries of stakeholders’ own be- liefs and understandings regarding what is possible in terms of refashioning and rejuvenating a school community’s instruc- tional leadership cultur e. A majority of the high school educators and community stakeholders participating as “case production team members” in this multimedia case development project were convinced at the outset of project activities that the entrenched, conflicting beliefs permeating their school and district communities— con- flicting beliefs which had stymied change implementation ef- forts to date at their campus—were intractable and, in effect, were permanently undermining any real prospect for open col- legial conversations that could lead to meaningful change. However, as stakeholders became actively involved in the pro- ject’s case production activities, the immersive nature and in- tensity of the collaborative participation necessary to actually engage in and complete the case development project work enabled these stakeholders to experience first-hand a new kind of team-learning environment that challenged and expanded their organizational thinking. Through their sustained involve- ment in the project’s case development and analysis activities, school stakeholders began to discover that they could actually leverage their belief conflicts to advantage to engage in new kinds of more open and deeper conversations about those very belief conflicts—conflicting school community member beliefs about instructional effectiveness and organizational change that stakeholders had for so long been convinced were intractable. And, importantly, stakeholders were developing new under- standings (as well as new confidence) on how their own per- spectivist differences, if addressed openly and honestly, could become a starting-off point for building more multi-dimen- sioned and nuanced sets of “team-centered” common values and shared understandings about the nature of organizational change and the prospects for positive instructional leadership in their school community. Moreover, these new team-centered understandings could serve as catalysts for opening up potential new avenues of creative change leadership thinking and strate- gic action planning that could help move their school organiza- tion forward in positive ways. This process of evolving shared values and reciprocal ways of thinking involved discovering common ground and developing a sense of collegial agreement regarding the overall nature and quality of the classroom-based, grade-level, and school-wide teaching and learning environ- ments stakeholders desired for students, as well as the kinds of student progress monitoring and learning intervention and sup- port mechanisms that should be in place on their campus to ensure that all students can be successful. These initial team- centered understandings regarding “standards of quality” relat- ing to the school’s overall teaching and learning environments then became an important foundation upon which stakeholders could begin to build further consensus regarding the desired focus and direction of their instructional leadership and school improvement practices. These critical reflective “team conversations” were an ongo- ing, integral component of the overall project’s multiple case development and analysis activities. Collectively, these team conversations served as an important foundational impetus for helping stakeholders begin the process of learning how to work together in new team-oriented ways as school change leaders (without at first necessarily being consciously aware that they were doing so)—a process of immersive, collaborative organ- izational learning in which the teaming process itself becomes a new way. Case Development Activities Provided Participants with an Alternative Organizational Learning Platform to Explore the Teaming Process in New Ways and to Reinve nt Themselves as Col l aborative Learning Communities. The creative ways that communities of people throughout history have come together as leading and learning communi- ties to cope with adversity, to adapt to new environments, and to deal with the challenges of limited resources have long fas- cinated cultural anthropologists and organizational sociologists. There are numerous accounts throughout history of communal groups of people connected together via tight-knit social and cultural bonds who have displayed remarkable ingenuity and resourcefulness in responding effectively to the myriad limita- tions and challenges of their immediate environments. These communal groups have also exhibited an intriguing propensity for learning how to work together creatively in win-win ways that can benefit the entire group. The French Acadians (Les Acadiens de France) of south Louisiana, for example, have evolved a rich and fascinating Open Access. 272  J. CLAUDET cultural heritage—a heritage hard-won over time as a result of having to learn how to creatively adapt to the challenges of surviving in a new hostile land: the unforgiving marsh and swamp environments of the lower Mississippi River delta re- gion and surrounding bayous and tributaries. The French Aca- dians’ rich cultural heritage and collaborative teaming propen- sities evolved to a large extent as a direct result of the difficult historical circumstances that befell the Acadians, and through which they had to both survive and learn how to reinvent themselves as a people. In the mid-1750s war between the Brit- ish and the French in North America was imminent. To prevent the French Acadians from allying with the French forces, the British decided to expel this entire group of people from their settlements in Nova Scotia. Deported from Nova Scotia by the British in 1755, the French Acadians were forced en masse to board ships and sail south down the Atlantic seaboard, around the tip of the Florida peninsula, and across the Gulf of Mexico to eventually find a new homeland in the marshes and bayous of south Louisiana. Their constant struggles to cope with the hardships of everyday survival in harsh, semi-tropical environ- ments, along with the attendant challenges of having to obtain sustenance through foraging for wild game in dense swamps and marshes and fishing in muddy bayous, molded these south Louisiana French immigrants into a tough people with a fiercely loyal and team-oriented communal culture. The need to survive in difficult circumstances and an unfamiliar environ- ment helped to shape the distinctive communal culture of these French Acadians in unique ways. Notably, these French immi- grants were compelled early-on as a people to quickly respond to the challenges of their new south Louisiana surroundings through: 1) adapting hunting and fishing techniques gleaned from indigenous Indian tribes in the region; 2) learning how to creatively extend and maximize available limited resources; and 3) developing and refining distinctive cultural mores that focused on the ingenious use of collaborative teaming methods as a means to extend the quality of life for their families and enhance the overall prospects for these French Acadians—as a collective group—of surviving and flourishing in their new homeland. The need to find creative ways to extend and maximize their limited food resources compelled Acadian communities to in- vent and engage in various kinds of creative communal events that were designed to ensure the survival of their close-knit communities. Acadian community members of all ages partici- pated enthusiastically in these social gatherings that served as a means for the Acadians to learn and share new cooking tech- niques and new ways of teaming together to prepare food that could feed large numbers of families and sustain them, often through long winter months. The fierce, survivalist mentality of the French Acadian people—and, in particular, their penchant for infusing variations of collaborative teaming into all facets of their everyday lifestyle—was especially evident in their group-oriented approach to the preparation and sharing of food within their communities. For example, this emphasis on team- ing as a fundamental aspect of daily life was clearly evident in the boucherie—a French Acadian communal event that was commonly practiced for hundreds of years in Acadian commu- nities, and continues on as an integral part of Acadian cultural life to the present day. The boucherie, as developed and prac- ticed in French Acadian culture, involved families throughout an Acadian settlement coming together to slaughter and cook a hog as a means to provide meat for the whole community. One family would donate the hog, which would then be butchered, cooked, and prepared for distribution throughout the commu- nity. The traditional boucherie was (and still is) a day-long communal event in which multiple groups of community mem- bers would spontaneously form ad hoc cooking teams to turn particular segments of the hog into specially prepared delicacies for consumption. Some of these cooking teams, for example, would focus on cutting away the backbone meat from the hog and cooking it in large pots to prepare backbone stew. Other teams would work on cooking down the head to make hogs- head cheese. Still other teams would prepare andouille sausage, and on and on until every bit of the animal (including ears, snout, brains, feet, and all) was boned-out, carved, cooked, and consumed. These cooking teams were multi-generational col- laborative affairs in which older, more experienced family eld- ers worked side by side with younger adults in the slaughtering and multiple cooking activities to share their expertise and time-tested best practices. In addition, community members participating in the boucherie also engaged in a good deal of “role swapping”, frequently taking on multiple roles both within and across various cooking teams during the boucherie event (e.g., cleaning the hog, chopping firewood and stoking fires, preparing necessary ingredients to cook different parts of the hog, etc.). These kinds of multi-generational collaborative teaming and peer coaching group-oriented behaviors were in- tegral socio-cultural aspects of Acadian communal events. The active participation and ad hoc teaming aspects of the boucherie served to generate an infectious joie de vivre and camaraderie that was felt by all participants and which helped to define the overall communal cultural nature of the boucherie event. Col- lectively, this emphasis on multi-generational collaborative teaming, in combination with a practical ingenuity in using available tools and resources, and a pronounced focus on real- world problem solving were distinctive characteristics of the French Acadians’ way of life—characteristics which enabled these immigrants to survive and flourish in their new environ- ment. Very much like the French Acadians of south Louisiana who immersed themselves in culturally rich, communal learning events as a way to share knowledge and ensure their own con- tinued survival, the high school educators and school commu- nity stakeholders participating in the high school campus mul- timedia case learning project reported in this article were able—through their direct involvement in case production and analysis activities—to leverage their project experiences to develop a more mindful and engaged critical reflective stance toward their organization and its challenges. As project work progressed and as school community stakeholders became im- mersed in case development activities, these “school stakehol- ders—turned multimedia case developers” were able to move gradually, but decisively, from simply reacting passively to or- ganizational change via attempting to cling to old status quo methods, to becoming more inventive and resourceful in their organizational thinking and decision making. As a result of their project-based “team-learning experiences”, these stake- holders began to engage more consciously and purposefully as a collaborative production team with their own high school community’s current challenges with renewed confidence and a determination to utilize their school organization’s limited re- sources in new, creative ways (as “resource assets embodying great potential” rather than as “limiting liabilities”) to benefit the entire school community. This kind of practical ingenuity Open Access 273  J. CLAUDET in the use of limited resources was extended and amplified as stakeholders began in earnest to collaboratively explore and reflect on their own school data. As an integral part of case development and analysis activities, campus stakeholders ac- tively participated in numerous critical reflective “team con- versations” about their own school community data. This team- oriented approach engaged many stakeholders (espousing mul- tiple individual role perspectives and beliefs) in a dynamic process of interacting directly with their school’s data and sharing their individual and group assessments and interpreta- tions of these data. Acting as members of a collaborative team, these school community stakeholders then began to look much more carefully and critically at their own school community data in new ways—examining their school’s data (e.g., student population demographics; grade- and school-level content area- specific student performance profiles; progress monitoring re- sults; response to instructional intervention data; etc.) with a new sense of collegial awareness and a new discriminatory at- tention to details in the data. These ongoing, data-driven team conversations generated a rich palette of multi-stakeholder school leadership interactions that served as a dynamic means to inform the shape and direction of stakeholders’ collaborative organizational thinking and guide their group instructional de- cision-making. For example, during case team “action planning” activities in which campus stakeholders focused intently on critically ana- lyzing their school community situational data in order to de- velop specific short- and long-term action plan strategies to move their school community forward, several teacher mem- bers of the campus production team began to openly express their new-found enthusiasm for the mobile digital technologies (laptops, ipads, ipods, etc.) and social media resources (e.g., blogs, wikis, online pinboards, facebook, twitter) they were us- ing in their multimedia case production work. These teachers, some of whom had been decidedly negative in response to re- cent pressures from the district to integrate technology into their instructional practices, were beginning to see the potential of these technologies as “digital tools” that they might be able to adapt and apply directly to inform the design of their own ongoing professional development as teachers. During their case team’s analysis conversations, these teachers began to reflect openly and positively about the broad application poten- tial of these digital technologies and to ask some very practical questions: “If these technologies can work for us in helping us analyze our overall school situation within this case project, could they also be potentially useful in assisting us with our own ongoing professional development as teachers?” and “How could we leverage these technologies which we are learning about and employing in our multimedia project case develop- ment work—in particular, mobile technologies and social me- dia resources—to directly inform our own daily instructional planning and classroom teaching practices?” These teachers, in fact, were beginning to realize that they could actually leverage digital technology itself (via mobile technologies and social media) to work smarter and more efficiently. These teachers were learning that these technologies could be viewed as “help- ful resources” that these teachers and their colleagues could use to acquire and share the practical kinds of real-world profes- sional development knowledge they needed to help them inte- grate technology effectively into their science and math teach- ing (for example: through sharing helpful tips among teachers on how to develop instructional videos or “vodcasts” that stu- dents could access and download to enhance their individual content learning). Educators at this high school, in essence, were discovering new ways, prompted by their own case learn- ing project experiences, that they—working together as a lead- ing and learning team—could leverage and apply available technology resources to create e-learning networks throughout their school community to benefit both students and teachers. In effect, stakeholders’ participation in project work enabled them to experience first-hand—in an intensive, immersive way—the positive payoffs of collaborative teaming. And, these payoffs included the experience of learning how to think dif- ferently and work together in new ways to extend and maximize their school community’s own available resources to develop “just-in-time creative solutions” to real-world problems. The teaming process itself effectively created a new kind of organ- izational learning environment within which “purposive gains” in both individual and team-oriented organizational learning could be achieved. These new learning insights accumulated as the project progressed and set the stage for the team to generate sets of practical action strategies that could lead to meaningful organizational change. These kinds of “incremental gains” in stakeholder thinking can be very important in building team confidence as stakeholders embark on the journey of learning how to work synergistically and effectively as a collaborative team to deal with complex, and often unforeseen, organiza- tional challenges. Moreover, these team-acquired insights can be very beneficial in terms of helping to “institutionalize” the practice of collaborative learning as an integral part of a culture of continuous improvement in a school district community. In recent years, researchers investigating the challenges of man- aging real-world organizational change have underscored the significance of these kinds of “incremental gains” for helping stakeholder teams cope with difficult, unexpected problems and build organizational resilience: “Small wins have their impact through the tangible examples they provide for others, through the allies they attract and the opponents they deter, through doing something tangible, and through creating a context with- in which change is now seen as possible [emphasis added]” (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007: p. 140). The multimedia case production project completed at this high school essentially presented participating educators and school community stakeholders with an “alternative team- learning platform” for exploring their organizational change leadership thinking—using their own school community data to do so. This team-learning environment enabled participants to explore and experience first-hand the real pay offs of communal decision making through learning how to think differently and work together in new ways. The “teaming itself” became a new way as stakeholders experimented and discovered together how to creatively apply their own practical ingenuity and collabora- tive problem-solving acumen to their school’s real-world chal- lenges to reinvent themselves as collaborative learning commu- nities. Sustained Immersion in Organiz ational Case Development Ac tivities Became a Powerful Collabora ti ve L earni ng Catalys t for Changing Stakeholder Beliefs and Jumpstarting the School Turnaround Pr ocess. Through participating in the project’s collective case devel- opment and refinement activities, campus stakeholder team members were engaging for the first time in a new kind of or- Open Access. 274  J. CLAUDET ganizational learning experience that was purposely designed to expand and deepen their individual and collaborative “lead- ership thinking” about their own context-specific dilemma situation. This expansion and deepening of stakeholders’ lead- ership thinking as the project progressed was fueled by the emergence of fundamental changes in stakeholders’ core teach- ing, leading, and learning beliefs. These transformations in stakeholder beliefs evolved incrementally and coalesced during the course of project work within three identifiable areas: 1) the change process itself; 2) the nature of instructional leadership in their school; and 3) the potential of the instructional improve- ment initiatives for jumpstarting the school turnaround process and positively impacting student learning. The Change Process School leaders rely on multiple sources of information (in- formation about programs, personnel, student performance levels, etc.) to help them make informed decisions relating to selecting and implementing the most appropriate and poten- tially effective sets of school improvement strategies. And, all information (i.e., “data”) in school communities really exists in its raw form as a gestalt of potentials—“data” that, if engaged with correctly, can be analyzed and interpreted by school community stakeholders to generate creative action strategies to assist them in implementing appropriate change initiatives that can help move a school forward. The creative action plans gen- erated might take the form of new “departmental improvement action strategies” that team members could derive from spend- ing time reflecting with and on their own data, or perhaps new “district-wide implementation plans” that stakeholders could arrive at together regarding the most cost effective and educa- tionally sound way a district could move forward with a pro- posed organizational change initiative. In this sense, an organi- zation’s information (data) is a rich well or resource that must be continuously tapped by multiple stakeholders throughout the organization—stakeholders approaching their organization’s data from multiple directions, perspectives, and departmental vantage points. To counteract the negative effects of “information analysis collapse” (i.e., a phenomenon that often occurs when only one or a very few administrators and other educational personnel have access to and analyze available school data) school com- munity leaders can work proactively to include as many stake- holders as possible in collegial conversations to “analyze” and “interpret” their school’s instructional programs and student performance data to generate “multiple creative ideas” from teachers and administrators on how to enhance instructional planning and daily classroom teaching and learning. Research- ers investigating the leadership challenges associated with en- acting system-wide change in leading and learning organiza- tions have noted the advantages of encouraging multiple mem- bers to interact directly and continuously with their organiza- tion’s data: “As each observer interacts with the data, he or she develops their own interpretation. We can expect these inter- pretations to be different, because people are. Instead of losing so many of the potentials contained in the data, multiple ob- servers elicit multiple and varying responses, giving a genuine richness to the observations. An organization rich with many interpretations develops a wiser sense of what is going on and what needs to be done [emphasis added]” (Wheatley, 1999: p. 67). Assisting school stakeholders in learning how to refashion their “organizational thinking” to embrace the win-win payoffs of this kind of collaborative team approach to analyzing, inter- preting, and leveraging their school data in order to expand and deepen the potential sets of creative action strategies they are able to generate is a critical element of school organizational learning support programs that can directly influence the qual- ity of stakeholders’ “involvement” in the change process, as well as the overall “effectiveness” of the change initiatives themselves. Engaging with educators and community stake- holders in their own organizational setting within the parame- ters of a context-specific case learning project to help these stakeholders learn to develop and internalize a collaborative team approach to mining and analyzing their own school data—and then using the insights obtained to inform their real- world instructional decision making—was a central focus of the multimedia case development project described in this report. Through participating in case production activities, including an extended series of team conversations focused on analyzing their own situational data and critically exploring multiple school improvement options emanating from these analyses, these school community stakeholders began to develop a new appreciation for the rich diversity of leadership perspectives espoused by individual team members. As campus stakeholders became immersed in case development work and as the case analysis component of the project progressed, team members began to recognize that these different stakeholder perspectives (considered individually as well as combined in various nu- anced ways) could be leveraged and applied directly by the team during their data analysis conversations to generate multi- ple interpretations of their school data that, in turn, could lead to a richer array of creative action plan options. School com- munity stakeholders, in effect, were beginning to look more carefully and critically at their own school data—examining their data through the varied lenses of multiple team member perspectives, causing stakeholders to develop a new sense of collegial awareness and discriminatory attention to details in the data. This ability to engage in self-referential communal conversations through leveraging and applying stakeholders’ multiple perspectives to enhance their analyses and interpreta- tions of their school data and to then use these conversations as a springboard to tap into and refine their critical reflective deci- sion-making potential as a school leadership team was seen by all involved as an important positive “organizational learning benefit” emerging from case project activities. Collectively, these team-oriented attributes and behaviors which stakeholders developed for engaging with and within the change process—namely: 1) adopting a critical reflective stance toward their school’s data; 2) discussing and applying stake- holders’ varied perspectives to analyze and generate multiple interpretations of these data; and 3) developing an evolving collegial awareness and an enhanced discriminatory attention to identifying details in their school data—were seen as important latent organizational core competencies that emerged and were strengthened as a result of stakeholders’ participation in project activities. Through exploring and developing their own teaming potential within these core competency areas, these campus stakeholders gained increased confidence in their ability to work together effectively—a new collaborative team confi- dence that enabled them to successfully engage in and complete their case production and analysis project work and to then fur- ther leverage and directly apply this newly acquired team con- fidence as they moved forward with their school community’s instructional improvement efforts. Open Access 275  J. CLAUDET The Nature of Instructional Leadership in Schools School stakeholders’ continuous involvement in multimedia case development and analysis activities associated with project work served as a catalyst for encouraging these stakeholders to begin to think differently about their own school instructional data, and to think in new ways about their own responsibilities as instructional leaders. To facilitate and enhance case project development work, university multimedia technology special- ists involved in the multi-entity case effort set up a number of online discussion boards and chat rooms for campus stake- holders to use as they collaborated together within the various case development and analysis activities. While a few of the teachers on the case production team were already familiar with these kinds of online information sharing and collaboration tools, a majority of the teachers and other stakeholder members of the team were not. Thus, as part of project activities, univer- sity technology specialists spent some time at the outset of pro- ject production work providing “on-the-spot training support” to these campus team members to help them become comfort- able with using and interacting with these digital tools. These kinds of digital information sharing and collaboration tools (e.g., online discussion boards, chat rooms, and the like) proved invaluable to campus case production team members through- out the project, enabling school stakeholder team members to begin to work together in new ways and to forge new collegial bonds within a safe, mutually agreed upon virtual organiza- tional learning environment. School stakeholders were able to effectively utilize this virtual online environment to engage in numerous dynamic team member interactions on a number of important issues relating to their school community’s instruc- tional leadership challenges, including discussions that focused on: 1) identifying and utilizing appropriate interpersonal com- munication strategies for managing the difficult “team conver- sations” that often surfaced during case development and analy- sis activities; 2) brainstorming creative strategies for interacting more effectively with multiple school constituencies to enhance boundary spanning and strengthen school-family-community partnerships; 3) generating multiple ideas on how to go about nurturing a positive school educational and social climate in an era of increasing learner diversity; and 4) reflecting critically on how campus stakeholders might be able to begin to work to- gether differently to foster a genuine teaching, leading, and learning organizational team mentality among all stakeholders and stakeholder groups throughout their school learning com- munity. Intriguingly, as teachers and other stakeholder team members began to actively use these digital tools during the project’s case production activities to informally communicate with their team colleagues (through brainstorming and sharing case de- velopment ideas; identifying and discussing various features of team members’ nuanced perspectivist views on case issues, etc.), these educators began to realize that they might also be able to leverage and use these very same digital tools more expansively on their campus on a daily basis to support their individual grade-level and school-wide instructional leadership efforts. Moreover, these educators were also discovering that these digital tools could be used quite effectively to facilitate teachers’ own ongoing individual and collaborative profes- sional learning. Through using these digital tools to engage with their colleagues during case production activities, teachers began to develop a more informed understanding and apprecia- tion of the notion that the overall fabric of teaching, leading, and learning in their school must include their own professional learning and development as educators, and that they—as edu- cational leaders—will need to play a committed, proactive leadership role in shaping the direction and foci of their own ongoing professional learning and development. These educa- tors were developing a more informed awareness of the critical importance of developing a greater sense of responsibility for and ownership in their own professional learning as a vital component of instructional leadership in their school—and, importantly, that these new kinds of digital technologies could provide them with the kinds of information sharing and infor- mal communication tools that would enable them to take charge of their own staff development and professional learning needs. Teachers and administrators were learning first-hand through their involvement in multimedia project activities about the leveraging power of mobile computing technologies and social media to enhance their own access to high quality, “just-in- time” informal kinds of professional learning. These newer, informal professional learning opportunities emphasized the use of technology-mediated social networking to expand and deepen educators’ ongoing learning, and included such things as collegial sharing of instructional best practices and peer coaching support—professional development opportunities that were not readily available within the school community and district before the advent of these kinds of technologies. Most importantly, through their technology immersion experiences as part of the multimedia case-learning project these educators began evolving their own context-specific understandings re- garding the role and usefulness of technology in enhancing overall teaching and learning effectiveness. As a result, these high school educators began to actively embrace a more in- formed and critically reflective stance regarding the nature and functions of technology-integrated instructional leadership within a school and district learning community. Moreover, in an intriguing way, these high school educators’ involvement during case analysis project activities in directly using mobile computing technologies and social media to facilitate their team’s informal peer coaching and information sharing case analysis work also served to create a new and powerful kind of multi-generational communications bridge connecting veteran teachers’ strong beliefs regarding the importance of traditional instructional “quality” with other teachers’ interests in engaging actively in technology-integrated “instructional planning and teaching”. This evolving technology-mediated communications bridge became a springboard for opening up new professional learning insights among school team members on how they might reconcile their diverse multi-generational instructional beliefs to explore new ways to work together to meet the needs of 21st century learners. In connection with this, a key insight that was widely shared and discussed by campus team members was their realization that in order to be competent and effective 21st century instructional leaders—that is, to be able to suc- cessfully integrate technology into their classroom instructional practices, which of necessity must include being able to effec- tively model and foster technology-integrated learning in their students—these teachers would first have to fully embrace, internalize, and integrate technology into their own ongoing professional learning practices. This insight regarding the na- ture, purposes, and scope of instructional leadership in schools underscores the importance of developing and nurturing a rich instructional leadership culture in school communities—an instructional leadership culture that is multi-dimensioned and Open Access. 276  J. CLAUDET expansive enough to include teachers’ own career-long profes- sional learning. There is widespread agreement among school improvement researchers concerning the centrality of teachers’ ongoing professional learning as an essential component of effective school instructional leadership. As Gordon (2004) asserts, “Professional development is needed to foster collegial- ity and professional dialogue, to help teachers develop a com- mon educational purpose, and to facilitate collaborative plan- ning, experimentation, and critique of teaching practice.” Addi- tionally, professional development can help educators “identify and critically examine aspects of a school’s culture that are inconsistent with the empowerment of students as life-long learners, and can lead to both cultural change and changes in curriculum, instruction, and student assessment” (Gordon, 2004: p. 7). Moreover, integrating robust and meaningful professional learning and development experiences directly into teachers’ daily work life can help transform schools into what Roland Barth (2000) describes as a “community of learners, a culture of adaptability, and a place of continuous experimentation and invention” (Barth, 2000: p. 69). One noteworthy dividend that emerged following completion of the multimedia case project was that these high school edu- cators, many of whom were exposed for the first time to the positive teaching and learning potential of digital communica- tion tools through participating in project activities, continued to expand and deepen their interest in utilizing these digital technologies to enhance their classroom instructional practices as well as their own professional learning. With ongoing post- project assistance from university technology integration spe- cialists, educators in this high school community have contin- ued to explore ways to creatively leverage available digital technologies (including mobile technologies such as laptops, ipads, ipods, and the like) along with widely accessible social media resources (e.g., facebook, twitter, pinterest, LinkedIn, blogs, wikis, social bookmarking, shared annotation services, RSS readers) as new kinds of teaching and learning enabling tools for building flourishing e-learning communication net- works for both students and educators in their school and dis- trict co mmuni ty. Change Initiatives and School Turnaround Efforts A unique feature of the multimedia organizational case learning project reported in this article is that the education stakeholders (teachers, parents, community members, and cam- pus- and district-level administrators) who became involved in project activities were brought together purposefully by the demands of their own organizational circumstances. These stakeholders’ involvement in this multimedia case development and analysis project represented a collaborative attempt on their part to try to better understand and respond to a complicated set of instructional and sociopolitical leadership challenges that had evolved over time and that had come to define a very diffi- cult and intransigent teaching, leading, and learning impasse situation within their school community. In this important sense, the “challenging situation itself” served as the primary catalyst to bring these people together to work collaboratively to extend the limits of their organizational leading and learning poten- tial—in effect, to explore and learn how to think differently and work together in new ways as a school leading and learning community. Robust population growth in the region in recent years re- sulting in a dramatic expansion of the Hispanic student demo- graphic profile at this high school (as well as throughout the district) along with increasing student performance account- ability demands imposed by the state had converged to create new sets of instructional leadership challenges for educators and other stakeholders in this high school community. As a result of these demographic shifts, the larger regional environ- ment within which this high school resides had now changed so dramatically that the school and its educational leaders had reached a “tipping point” where the status quo instructional practices of the past (which were developed and employed by many teachers at this high school over several years) were no longer as relevant to the learning needs of the school’s pre- sent—much more culturally diverse—student population. The reality of the new population diversity in the larger regional environment within which the school and district were situated was now necessitating the need to remake or transform the instructional culture of this high school. However, many ex- perienced educators in this school community and district were continuing to display a passionate commitment to their own well-worn instructional beliefs, including their belief in the continued usefulness of the “traditional, time-tested instruc- tional practices” which they had been using for years. Moreover, these highly entrenched, status quo beliefs were engendering an openly observable and ultimately counterproductive profes- sional attitude bordering on “instructional complacency” among many of these veteran teachers—teachers who, over time, had become stuck in their own “instructional comfort zones”, and who were still operating from a traditional set of instructional beliefs and practices that they were highly committed to and believed were in the best interests of students and their learning. These attitudes were shared as well by many parents and other members of the community who were also supportive of these same status quo instructional practices. These sets of en- trenched instructional beliefs were on clear display as many of these same teachers and other stakeholders participated in case project team conversations. Additionally, these beliefs clashed directly with the contrasting, more progressive beliefs of other educational leaders within the campus and district community (some of whom were also participants on the case project team)—particularly those leaders espousing the merits of the new instructional change initiatives. What was needed was a “new way of thinking about instruc- tional effectiveness”—a new, creative way of reframing in- structional leadership practice in this high school that was broad and expansive enough to accommodate the school’s new student diversity as well as focused and rigorous enough to be able to respond to these students’ learning challenges. Intrigu- ingly, such a potential “new way of thinking” emerged in a very spontaneous way during one of the multimedia project team’s case analysis sessions. As these high school stakeholders were brainstorming possible practical strategies for dealing with their instructional improvement challenges, one team member—a tenth grade teacher of Hispanic descent at this high school who had been both listening reflectively and participating intently in the team’s conversations—at one point decided to share with her fellow project team members a “cultural practice story” she was very familiar with from her own upbringing. This teacher’s “story” involved describing to her team colleagues an annual celebratory event that she indicated was a common practice in Hispanic communities: dias de fiestas. This teacher explained to her team colleagues that during dias de fiestas locals typi- cally show their generosity toward others through welcoming in Open Access 277  J. CLAUDET all who come to share in the meals and festivities. Tourists and visitors to the town are openly embraced and become an inte- gral part of the dias de fiestas celebrations, as they are viewed by locals as contributing in very positive ways to the overall richness and diversity of the fiesta. Furthermore, there is a widespread understanding among local community members that displaying generosity and a welcoming spirit to others actually is a way of giving to oneself—the act of inclusiveness and cyclical reciprocity actually enriches oneself. This teacher explained to her team colleagues that these dias de fiestas are celebratory events in Hispanic culture—community-wide events that emphasize the value and importance of nurturing harmonious relationships and inclusiveness. As this teacher continued sharing her story and reflecting out loud as she spoke, she indicated that her own personal reflections on the cultural practice of dias de fiestas were helping her to begin to reevalu- ate and expand her own thinking about the notion of “instruc- tional effectiveness” in a high school community. This cultural practice analogy was helping her come to a new realization that a “diverse learning culture” can be a source of organizational strength rather than a liability, and that adopting a proactive focus on fostering broad community engagement and inclu- siveness can actually be a positive means for facilitating and enhancing school-wide instructional improvement. This tea- cher’s story—highlighting the culturally enriching benefits that can accrue to both oneself and an entire community through setting and maintaining a conscious focus on inclusiveness and relationship building—was one that impressed her fellow team colleagues and captured the team’s collective imagination. The story resonated so strongly with team members particularly be- cause of the rich insights it seemed to offer these stakeholders in terms of helping them gain a deeper understanding of the po- tential of their own school district’s change initiatives as crea- tive celebratory means for: 1) recognizing and valuing the con- tributions of multiple diverse learners; 2) increasing the level and quality of overall learner engagement; and 3) nurturing a broader and more inclusive instructional leadership culture within their own school community setting. Project team members continued to discuss and reflect at length on this teacher’s “cultural practice story” as they pro- gressed in their case analysis conversations and strategic action planning sessions. In particular, team members’ ongoing col- laborative reflections on their colleague’s story began to chal- lenge and expand their own “team thinking” about instructional effectiveness. These high school stakeholders, reflecting to- gether as a leadership team, began to identify and crystallize multiple school community leadership insights drawn from their colleague’s story—insights that they were able to inter- nalize as a leadership team and apply directly to their own si- tuation to help them better understand their own school’s in- structional leadership challenges. Indeed, at one point during their case analysis and strategic planning conversations these school stakeholders, working together as a case project team, appeared to arrive at a collective “aha moment”. A growing “team realization” began to evolve and take shape among team members during their deliberations: the idea that proactively embracing the practical strategy of including students and par- ents directly in the process of collaborative instructional plan- ning could be both a creative and a realistic way to approach instructional planning in their school and simultaneously ad- dress their school change and improvement dilemma challenges. In essence, these stakeholders were beginning to embrace the “win-win” organizational leadership insight that instructional planning in their school could be usefully viewed as a school community-wide collaborative team and instructional culture- building endeavor—that is, as a multi-stakeholder, communal school-family-community partnering enterprise. And, this com- munal partnering approach to instructional planning, in fact, could be a potentially very practical, real-world “instructional team leadership” strategy that school stakeholders could proac- tively enact together to address the teaching and learning chal- lenges in their school community. The adoption of this kind of practical “instructional team leadership” strategy, in fact, would directly reflect the inclusive celebratory spirit of the dias de fiestas, in which local community members recognize and ho- nor all new visitors and guests as important integral partici- pants in the fiesta, as well as active contributors to defining the fiesta itself. Importantly, as a substantive outgrowth of their case project team deliberations, these educators and school community stakeholders were developing their own collective team under- standing that perhaps the very same kind of “leveraging digital technologies to engage in immersive collaborative learning” process they were engaging in within their multimedia project activities could be expanded and applied broadly to their own daily academic teaming efforts to enhance the quality and ef- fectiveness of instructional planning and implementation within their school. These stakeholders would be able to accomplish this through taking a more inclusive approach to the “idea” of instructional planning through finding creative ways to include students and parents more directly in the instructional planning process. Embracing this communal partnering approach to instructional planning, educators at this high school began to incorporate several new school-community outreach strategies into school improvement action planning, including: 1) utiliz- ing social media tools (such as twitter and facebook) to enable teachers at this high school to communicate informally with each other as well as with teachers in other schools within the district for the purpose of brainstorming and sharing ideas on instructional planning and classroom teaching practices; 2) setting up monthly school-home liaison visits in which teachers and administrators could meet directly with parents in the fam- ily-home setting to discuss their child’s learning progress; 3) staging multiple “school-community education celebrations” in the evenings and on weekends to nurture a “culture of family- connected learning” throughout the entire school community; 4) scheduling bi-weekly teacher/parent meetings to keep parents informed regarding their child’s teaching and learning class- room progress; 5) utilizing the school’s classrooms and com- puter labs in the evenings to provide interested parents with adult literacy classes and technology training; etc. In actively embracing this team-centered communal partnering approach to instructional effectiveness through designing and implement- ing these new school-community outreach strategies, these high school educators and community stakeholders were, in fact, de- monstrating that they had internalized a new, inclusive “com- munity-wide team mentality” regarding instructional effective- ness in their school. And, as part of this team mentality, these stakeholders were beginning to realize that the school and dis- trict’s instructional planning and technology integration initia- tives were not simply burdensome initiatives that were at cross-purposes with their own teaching, leading, and learning goals for the school. On the contrary, these initiatives could actually be utilized directly to help these stakeholders engage Open Access. 278  J. CLAUDET together dynamically to bring about substantive change in their school community ’s instructional learning culture. Indeed, these instructional improvement initiatives could be utilized by these educators and community stakeholders—working together as a school community partnering team—as a means to jumpstart their school’s turnaround process and help them positively im- pact students’ learning. The positive value of this “synergistic strategy” of utilizing a communal partnering approach in con- cert with well-designed, targeted instructional improvement ini- tiatives to positively impact a school community’s overall “fa- mily-connected instructional learning culture” has been affirm- ed by researchers examining the present challenges of enacting social justice leadership in schools who emphasize the need for school leaders to make “concerted efforts to reach out to fami- lies who traditionally may not be active in their school and to make bridges to the community, [including] making purposeful positive contact with families of color, families who struggle financially, and families who are non-native English speakers” (Theoharis, 2009: p. 138). These high school stakeholders’ adoption of a new “com- munal team mentality” focused specifically on expanding and deepening their school’s instructional planning and learning culture as a means to turn around their school’s recent lacklus- ter performance and spur their school community toward posi- tive organizational change and improvement (i.e., to jumpstart the “school turnaround” process) resonates well with insights found in the recent literature on systemic school change. Re- searchers examining the challenges involved in bringing about system-wide change in school organizations recognize that to be able to effect meaningful change in teaching and learning in a school setting, educators must go beyond simply putting in place new change structures (i.e., change initiatives of various kinds). Fullan (1993, 1999, 2001), for example, has repeatedly made clear that “restructuring (which can be done by fiat) oc- curs time and time again, whereas reculturing (how teachers come to question and change their beliefs and habits) is what is needed” (Fullan, 2001: p. 34). In other words, in order to real- ize substantive change in teaching and learning attitudes and performance levels, the entire instructional culture of the school organization must be changed at a fundamental level. And this kind of fundamental school reculturing requires that educators engage directly in intentional experimentation and social dis- covery. As Elmore (2000) states, “[e]xperimentation and dis- covery can be harnessed to social learning by connecting peo- ple with new ideas to each other in an environment in which the ideas are subjected to scrutiny, measured against the collective purposes of the organization, and tested by the history of what has already been learned and is known” (Elmore, 2000: p. 25). And importantly, as Leithwood et al. (2010) emphasize, the process of connecting people and ideas must include connecting the school directly to the home family environment and directly to parents: “Without doubt, parental engagement in children’s learning makes a difference and remains one of the most pow- erful school improvement levers that school leaders have. But effective parental engagement will not happen without con- certed effort, time, and commitment from both parents and schools. It will not happen unless parents know the difference that they make and unless schools actively reinforce their active engagement in learning [emphasis added]. Parental engagement has to be a priority, not a bolt-on extra. It must be embedded in teaching and learning policies and school improvement policies, so that parents are seen as an integral part of the student learn- ing process” (Leithwood et al., 2010: p. 253). Moreover, this kind of organization-wide cultural change can not be accom- plished simply through the extraordinary efforts of individual change agents working in isolation—no matter how dedicated they may be to their school community or how passionately they believe in the change initiatives themselves. Enacting sys- temic cultural change in a school community requires the sus- tained commitment of a critical mass of education stakeholders who have developed an appropriate change-oriented “tea m men- tality” and who are motivated to respond to their school’s im- provement challenges in action-oriented ways. As a result of their immersive collaborative learning experi- ences in this multimedia case project, these high school educa- tors and school community stakeholders were able to form im- portant new professional and organizational bonds that cut across stakeholder roles and personalities. These new relational connections among stakeholders enabled a new “team mental- ity” to evolve among these stakeholders—a new collegial way of thinking that could support the emergence of generative breakthrough leadership insights and new collaborative under- standings across the team. This new way of thinking was forged through the very act of participation in the case learning process itself. Through the positive organizational leadership insights these team members realized as a result of their case learning project experiences (as well as through the sense of collabora- tive accomplishment these stakeholders felt upon completing this challenging project together), these educational leaders were now empowered with a new team confidence and a re- newed sense of their own collegial leadership efficacy. The new “team mentality” that emerged was characterized by a number of distinguishing features, including a shared sense among these educational stakeholders of: 1) their own organ- izational capacity as a school leadership team to enact mean- ingful change; 2) a greater conscious awareness and under- standing of the power of community engagement as a collabo- rative partnering tool to facilitate school-wide instructional improvement; 3) a new appreciation of the role of social net- working as a means to enhance information sharing and to sup- port the overall organizational learning vitality of their school community; and 4) a greater confidence in the distributive lead- ership potential of the group to design and implement team- centered, targeted instructional improvement strategies that can realize demonstrable student learning gains. Collectively, these newly observed “team characteristics” reflected a set of emerg- ing school turnaround leadership capabilities that was serving to reshape and redefine who these educational stakeholders were as school leaders and what they were capable of accom- plishing. At an informal gathering of school stakeholder team mem- bers and university project specialists following project post- production work to celebrate the completion of project activi- ties, these school turnaround leadership capabilities and the newly minted “team mentality” they reflected were in clear evidence as the members of the project’s high school case de- velopment team—teachers, parents, community members, and the school’s principal—shared some final reflections on their overall project experiences. One school stakeholder team mem- ber, a veteran teacher, captured well the sentiments of the group as she reflected on her own and her team members’ experiences participating in project activities: “This project was a real eye-opening experience for many of us. The work was intensive, and we were challenged to stretch our reflective thinking ca- Open Access 279  J. CLAUDET pacities in new ways—to enlarge our perspectives and broaden our mindsets. But, you know, I think the most important result of participating in this project is that we’ve developed a new respect for each other and our differences, and we’ve come to learn that our differences can be a source of strength. Through this project we’ve learned to respect and leverage our differ- ences to build some common understandings as a school com- munity team. And, I think we now have a new and better sense of what we are capable of achieving as a leading and learning team.” This teacher’s remarks echoed the feelings of other members of this high school stakeholder team and reflected well the new “team spirit” of the group. Finally, it was the school’s principal who possibly summed up best the collective feelings of the entire high school team as she congratulated her high school case production team on their collective project efforts: “As a result of this project and the team conversations we’ve had together, we now know that the school turnaround process is as much about turning around ourselves as it is about turning around our school. During our project work we’ve engaged together in critically examining and turning around our own thinking and behaviors—and learning from this self-reflecting process as we go. We ’ve been working con- scientiously on building our understandings as a team, and we’ve been reinventing ourselves in the process. However, let’s be honest—we still have a lot more work to do to realize the kinds of meaningful improvements we all want in our instruc- tional programs. But armed with our new ability to think and work together more effectively as a school community team, I believe we can now look toward our school’s future—and to- ward the future learning success of all of our students—with new confidence.” Conclusion The case development and analysis project work reported in this article is part of a larger, multi-year research and develop- ment effort that focuses on engaging education researchers, multimedia production specialists, expert practitioners, and education stakeholders from multiple education entities (i.e., a state university, a regional education service center, and multi- ple regional K-12 schools and school districts) in working to- gether in collaborative partnership to address and find creative solutions to vexing, entrenched problems of K-12 school lead- ership practice. A unique aspect of this project is the use of available multimedia computer technologies in conjunction with theatrical production techniques to involve K-12 school community stakeholders in the development and analysis of context-specific organizational learning cases about their own real-world school improvement dilemma situations. The pro- ject’s collaborative case learning design reflects a convergence of concepts and tools across three areas of creative activity: 1) multimedia computer simulations; 2) cinematography; and 3) dramatic arts. The high school “instructional leadership” case development project detailed and discussed in this article re- presents one completed case that has become part of a larger, continually expanding body of multimedia cases that are being developed to focus specifically on the context-specific organi- zational leading and learning challenges of groups of education stakeholders in multiple campuses and school districts through- out West Texas. The organizational case learning methods and design of this project are grounded in a rich history of research and develop- ment in computer-based simulations and educational gaming that has evolved over the past two decades. The success of such “strategic life simulation” games as The Sims (2000-2008, 2012-present) and its various renditions (The Sims Online, The Sims Stories, MySi ms, The Sims Carnival, The Sims Medieval, The Sims Social), “fictional-world graphic adventure” video games such as Myst (1993-present), “urban planning and de- velopment/municipal engineering” simulations such as SimCity (1989-present), and immersive “historical learning/adventure” educational simulations such as Oregon Trail (1974-present) and Westward Trail (2013) which are widely used by elemen- tary and secondary teachers to engage students dynamically in immersive, multi-disciplinary learning, have served to firmly anchor online simulations and gaming as both recreational gam- ing and educational learning tools in the popular imagination. These individual- and multi-player simulation games offer rich, interactive digital environments within which users can explore a variety of social, organizational, engineering, and manage- ment challenges integrated into multi-dimensional, online “vir- tual-world” simulations. The direct application and use of these kinds of computer simulations and video games in elementary and secondary educational settings have continued to expand in recent years. In addition, a variety of immersive digital learning tools and interfaces are now being used in multiple higher edu- cation learning contexts (e.g., business, economics, political studies, science and engineering, languages, education) to in- crease student engagement and retention and to stimulate learning, including: serious games, multiple role-play, whole- enterprise simulations, video simulations, augmented reality, robotics laboratories, and virtual learning environments to en- hance active learning and encourage interactive reflection (Ny- gaard et al., 2012). These kinds of virtual worlds, games, and simulations are being utilized in higher education settings to en- gage learners within interactive digital environments that are highly immersive, collaborative, and focused on real-world pro- blem solving (Shiratori et al., 2005). The multimedia case learning project efforts profiled in this article seek to extend and apply these computer simulation/ virtual world development efforts directly to the area of K-12 school leadership practice through involving groups of elemen- tary and secondary educators and associated school community stakeholders in immersive, collaborative team-learning project experiences to develop multimedia cases about their own real- world, context-specific school improvement challenges. The overarching goal of these immersive case-learning projects is to jumpstart school stakeholders’ “team-learning” abilities to fo- cus on and enhance the overall quality and effectiveness of these school leaders’ collaborative decision making. This mul- timedia organizational case learning project work is part of a larger, decade-long R&D initiative to develop immersive team- learning designs and attendant sets of school leadership learn- ing cases that are of practical use for enhancing the organiza- tional learning and collaborative leadership development of educators and community stakeholders in K-12 school settings. Collectively, these multimedia cases (and the larger immersive team-learning design approach of which these cases are an integral part) seek to contribute to the literature on the devel- opment and use of educational games, simulations, and virtual worlds through direct application of case learning simulations and collaborative teaming techniques to the real-world chal- lenges of K-12 school leadership practice. Results of cumula- tive project efforts to date provide encouraging positive evi- Open Access. 280  J. CLAUDET Open Access 281 dence in support of the potential of organizational case learning and immersive, technology-integrated case production methods as practical means for enhancing school leaders’ collaborative school improvement practices. Importantly, through leveraging the power of multimedia technology and the creative enthusiasm and dedication of the research teams involved, the collaborative team-building ap- proach at the heart of this project’s organizational case learning design provides a unique reflective analysis framework for school stakeholder collaborative learning. Through immersion in multimedia project case production and analysis activities, K-12 educators and school community stakeholders in varied school contexts can learn how to tap into their collaborative school leadership potential for reflecting critically on their own school leadership situations to reexamine, broaden, and deepen their educational beliefs through transformative team-learning. In short, through bravely heeding the cinematic call of lights, camera, action! school stakeholders grappling with tough school improvement challenges can elect to engage in a new form of organizational learning—as dedicated teams of rivals embracing a “collaborative case learning adventure” to develop and refine their own school leadership capacities for: 1) forging shared understandings and common organizational purpose; and 2) engaging in data-informed, team-centered decision mak- ing that can promote positive and lasting teaching, leading, and learning improvements within their school communities. REFERENCES Barth, R. S. (2000). Building a community of learners. Principal, 79, 68-69. Elmore, R. (2000). Building a new structure for school leadership. Washington DC: The Albert Shanker Institute. Fullan, M. (1993). Change forces: Probing the depths of educational reform. London: Falmer Press. Fullan, M. (1999). Change forces: The sequel. Philadelphia: Falmer Press/Taylor & Francis, Inc. Fullan, M. (2001). The new meaning of educational change (3rd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press. Goodwin, D. K. (2005). Team of rivals: The political genius of Abra- ham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster. Gordon, S. P. (2004). Professional development for school improve- ment: Empowering learning communities. Boston: Pearson Educa- tion. Kushner, T. (2012). Lincoln: The screenplay. New York: Theatre Com- munications Group. Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Strauss, T. (2010). Leading school turn- around: How successful leaders transform low-performing schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass . Myst (2013). Exploration-adventure simulation/online video game (first released: 24 September 1993). Developers: Cyan/Cyan Worlds (1993- present). http://www.mystonlin e . com/en/ Nygaard, C., Courtney, N., & Leigh, E. (2012). Simulations, games, and role play in university education. Oxfordshire: Lib ri Publishing. Oregon Trail (2013). Online game/simulation (originally created in 1974). http://www.freegameempire.com/games/Oregon-Trail Shiratori, R., Arai, K., & Kato, F. (2005). Gaming, simulations, and so- ciety: Research, scope, and perspectiv e. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/b138103 SimCity (2013). City-building simulation/online video game (first re- leased: 3 October 1989). http://www.simcity.com/en_US Spielberg, S. (2012). Lincoln [Motion picture]. United States: Dream- Works II Distribution Co., LLC and Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. The Sims (2013). Strategic life simulations/online video games. Deve- lopers: Maxis (2000-2008, 2012-presen t). http://www.thesims.com/en_US Theoharis, G. (2009). The school leaders our children deserve: Seven keys to equity, social justice, and school reform. New York: Teachers College Press. Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty (2nd ed.). San Fran- cisco: John Wiley & Sons. Weisbord, M., & Janoff, S. (2010). Future search: Getting the whole system in the room for vision, commitment, and action (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Westward Trail (2013). Online game/simulation. http://www.globalgamenetwork.com/westward_trail.html Wheatley, M. J. (1999). Leadership and the new science: Discovering order in a chaotic world (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.