B. B. FREY ET AL.

52

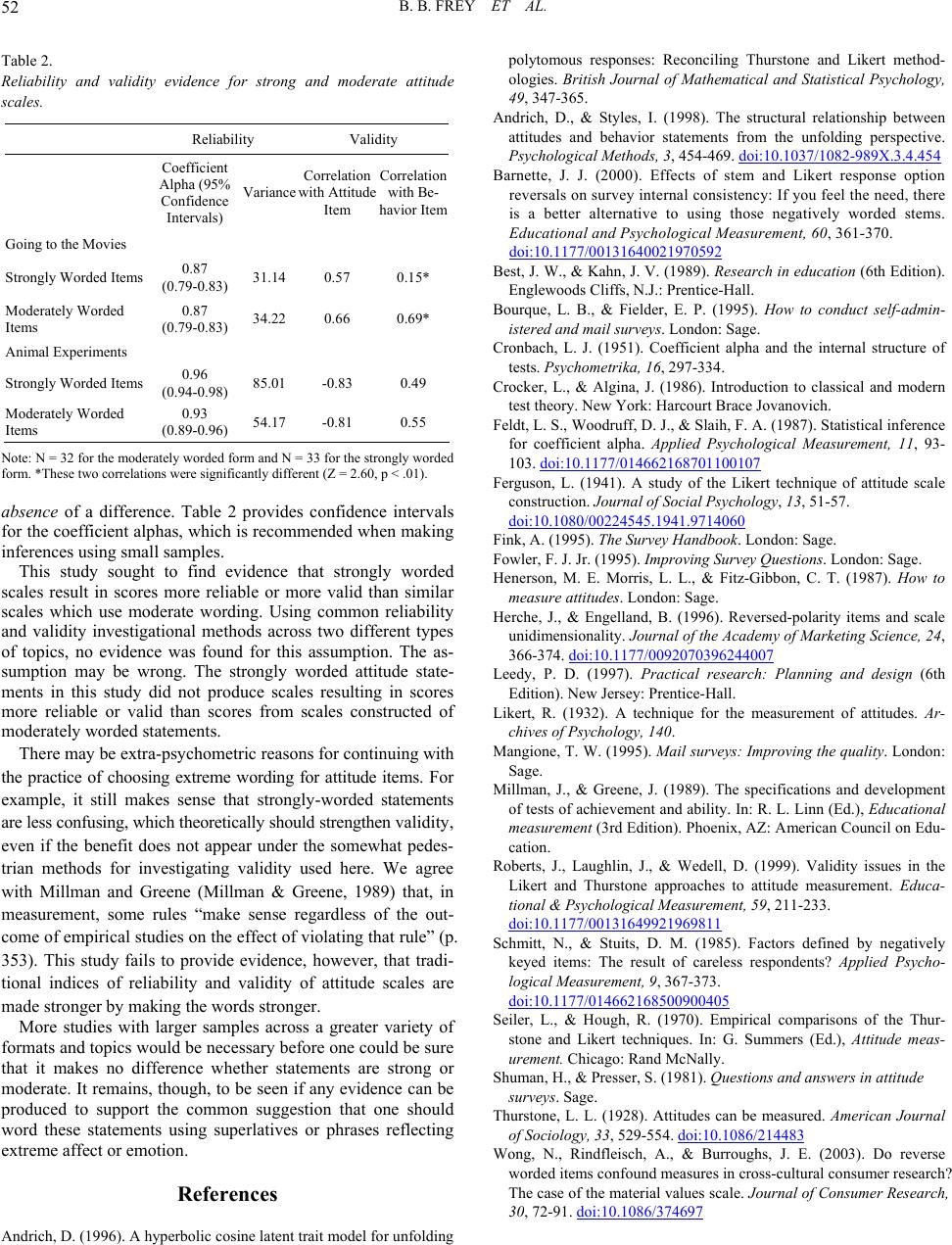

Table 2.

Reliability and validity evidence for strong and moderate attitude

scales.

Reliability Validity

Coefficient

Alpha (95%

Confidence

Intervals)

Variance

Correlation

with Attitude

Item

Correlation

with Be-

havior Item

Going to the Movies

Strongly Worded Items 0.87

(0.79-0.83) 31.14 0.57 0.15*

Moderately Worded

Items

0.87

(0.79-0.83) 34.22 0.66 0.69*

Animal Experiments

Strongly Worded Items 0.96

(0.94-0.98) 85.01 -0.83 0.49

Moderately Worded

Items

0.93

(0.89-0.96) 54.17 -0.81 0.55

Note: N = 32 for the moderately worded form and N = 33 for the strongly worded

form. *These two correlations were significantly different (Z = 2.60, p < .01).

absence of a difference. Table 2 provides confidence intervals

for the coefficient alphas, which is recommended when making

inferences using small samples.

This study sought to find evidence that strongly worded

scales result in scores more reliable or more valid than similar

scales which use moderate wording. Using common reliability

and validity investigational methods across two different types

of topics, no evidence was found for this assumption. The as-

sumption may be wrong. The strongly worded attitude state-

ments in this study did not produce scales resulting in scores

more reliable or valid than scores from scales constructed of

moderately worded statements.

There may be extra-psychometric reasons for continuing with

the practice of choosing extreme wording for attitude items. For

example, it still makes sense that strongly-worded statements

are less confusing, which theoretically should strengthen validity,

even if the benefit does not appear under the somewhat pedes-

trian methods for investigating validity used here. We agree

with Millman and Greene (Millman & Greene, 1989) that, in

measurement, some rules “make sense regardless of the out-

come of empirical studies on the effect of violating that rule” (p.

353). This study fails to provide evidence, however, that tradi-

tional indices of reliability and validity of attitude scales are

made stronger by making the words stronger.

More studies with larger samples across a greater variety of

formats and topics would be necessary before one could be sure

that it makes no difference whether statements are strong or

moderate. It remains, though, to be seen if any evidence can be

produced to support the common suggestion that one should

word these statements using superlatives or phrases reflecting

extreme affect or emotion.

References

Andrich, D. (1996). A hyperbolic cosine latent trait model for unfolding

polytomous responses: Reconciling Thurstone and Likert method-

ologies. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology,

49, 347-365.

Andrich, D., & Styles, I. (1998). The structural relationship between

attitudes and behavior statements from the unfolding perspective.

Psychological Methods, 3, 454-469. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.454

Barnette, J. J. (2000). Effects of stem and Likert response option

reversals on survey internal consistency: If you feel the need, there

is a better alternative to using those negatively worded stems.

Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60, 361-370.

doi:10.1177/00131640021970592

Best, J. W., & Kahn, J. V. (1989). Research in education (6th Edition).

Englewoods Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Bourque, L. B., & Fielder, E. P. (1995). How to conduct self-admin-

istered and mail surve y s. London: Sage.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of

tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334.

Crocker, L., & Algina, J. (1986). Introduction to classical and modern

test theory. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Feldt, L. S., Woodruff, D. J., & Slaih, F. A. (1987). Statistical inference

for coefficient alpha. Applied Psychological Measurement, 11, 93-

103. doi:10.1177/014662168701100107

Ferguson, L. (1941). A study of the Likert technique of attitude scale

construction. Jour na l o f So cial Psychology, 13, 51-57.

doi:10.1080/00224545.1941.9714060

Fink, A. (1995). The Survey Han db ook. London: Sage.

Fowler, F. J. Jr. (1995). Improving Survey Questions. London: Sage.

Henerson, M. E. Morris, L. L., & Fitz-Gibbon, C. T. (1987). How to

measure attitudes. London: Sage.

Herche, J., & Engelland, B. (1996). Reversed-polarity items and scale

unidimensionality. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 24,

366-374. doi:10.1177/0092070396244007

Leedy, P. D. (1997). Practical research: Planning and design (6th

Edition). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Ar-

chives of Psychology, 140.

Mangione, T. W. (1995). Mail surveys: Improving the quality. London:

Sage.

Millman, J., & Greene, J. (1989). The specifications and development

of tests of achievement and ability. In: R. L. Linn (Ed.), Educational

measurement (3rd Edition). Phoenix, AZ: American Council on Edu-

cation.

Roberts, J., Laughlin, J., & Wedell, D. (1999). Validity issues in the

Likert and Thurstone approaches to attitude measurement. Educa-

tional & Psychological Measurement, 59, 211-233.

doi:10.1177/00131649921969811

Schmitt, N., & Stuits, D. M. (1985). Factors defined by negatively

keyed items: The result of careless respondents? Applied Psycho-

logical Measurement , 9, 367-373.

doi:10.1177/014662168500900405

Seiler, L., & Hough, R. (1970). Empirical comparisons of the Thur-

stone and Likert techniques. In: G. Summers (Ed.), Attitude meas-

urement. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Shuman, H., & Presser, S. (1981). Questions and answers in attitude

surveys. Sage.

Thurstone, L. L. (1928). Attitudes can be measured. American Journal

of Sociology, 33, 529-554. doi:10.1086/214483

Wong, N., Rindfleisch, A., & Burroughs, J. E. (2003). Do reverse

worded items confound measures in cross-cultural consumer research?

The case of the material values scale. Journal of Consumer Research,

30, 72-91. doi:10.1086/374697