Open Journal of Nursing, 2013, 3, 472-480 OJN http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2013.37064 Published Online November 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojn/) OPEN ACCESS Challenges and facilitators for patient and public involvement in England; focus groups with senior nurses Markella Boudioni1, Susan McLaren2 1Institute for Leadership and Service Improvement, Faculty of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London, UK 2Faculty of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London, UK Email: mboudioni@yahoo.co.uk, aboriginefidus@btinternet.com Received 2 October 2013; revised 22 October 2013; accepted 30 October 2013 Copyright © 2013 Markella Boudioni, Susan McLaren. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attri- bution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT The concepts of patient and public involvement (PPI) have been recognized and linked with quality in health services internationally and in Europe. In England, for more than a decade, NHS policies have increasingly quoted patient-centred services. Limited evidence exists about the implementation of PPI poli- cies and strategies within organisations; three studies only have explored health professionals’ perceptions of PPI. Although nurses’ positive support for patient and public involvement has been noted, compara- tively little is known about senior nurses’ experiences of embedding PPI. A national consultation utilising three focus groups aimed to explore senior nurses’ perceptions of challenges and facilitators for PPI im- plementat ion. Four Strateg ic Health Authorities (SHAs) and eleven Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) in England, with fifteen senior nurses with leadership roles and direct PPI experience, participated. Nurses’ percep- tions on patient and public involvement, challenges and facilitators for its implementation were discussed. Focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim; anonymised transcripts were validated by participants and analysed with thematic analysis. Limited resources, patient representation and re- cruitment, complexities of implementing PPI and na- tional policy changes were challenging. Commission- ing limitations, lack of feedback on patient experience, limited staff awareness, negative attitudes, manage- ment of patients and public expectations constituted further challenges. Nursing role characteristics and informal involvement activities, PPI policy and cul- tural change, commissioning PPI competencies, re- lated service frameworks, providing feedback on pa- tient experiences to staff and recognition of involve- ment benefits were recognised as facilitators. Find- ings provided new insights into senior nurses’ ex- periences and evidence that progress towards mean- ingful, effective PPI remains slow. However, recogni- tion of existing nursing role characteristics and po- tential delivery problems created by expanded nurs- ing roles, informal PPI practice and internal organ- isational sharing of patient feedback may bring an “emerging productive partnership” with nurses ena- bling and contributing to effective PPI. Keywords: Nursing; Patient and Public Involvement; Challenges and Facilitators; Focus Groups; Patient-Centred Care 1. INTRODUCTION The concepts of patient and public involvement (PPI) and empowerment have been recognized and linked with quality in health services internationally and in Europe [1,2]. Countries have implemented a wide range of patient empowerment measures, including patients’ rights legislation (Netherlands, Greece), introducing ombuds- person services (Austria, Finland, Hungary, No rway, Greece) and increasing patients’ involvement and participation in care decision-making (England) [3,4]. In England, for more than a decade, NHS policies have increasingly quoted patient-centred services. Not- able drivers h ave been the legal duty to involve and con- sult the public [5] and the increasing body of inter- national ev idence for involving peop le in health care and its benefits [6-8]. Most recently, the PPI agenda has permeated the World Class Commissioning vision, stat- ing that “to be world class commissioners we need to know the needs and preferences of our local com- munities, work with our partners on the health and well-being agenda and work with local people to tackle health inequalities”. Specific emphasis was placed on “building continuous and meaningful engagement with  M. Boudioni, S. McLaren / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 472-480 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 473 patient and public to shape services”, as one of its competencies [9]. Furthermore, the “High Quality Care for All” [10] called for an NHS “that gives patients and the public more information and choice, works in part- nership and has quality of care at its heart”. Many definitions exist for involvement; INVOLVE [11] summarised this as “everything that enables people to influence the decisions and get involved in the actions that affect their lives”. To enable policy im- plementation, the English NHS has adopted the “In- volvement Continuum” [12], encompassing giving and getting information, forums for debate and partici- pation (Figure 1). Although the research evidence supporting PPI varies in quality, benefits identified in systematic reviews have included improvements in health literacy, clinical de- cision making, self-care, chronic disease management and patient safety [13,14]. Others have also demonstrated improvements in the information clarity provided and patients’ knowledge [15]. However, limited evidence exists about the implementation of PPI policies and strategies within organisations [16]. National surveys found that although health services were putting systems in place to involve people in planning and improving services, many challenges remained. Barriers included lack of commitment by senior managers or clinicians, inadequa te resources, lack of incentives and poor quality of interpersonal care [17-20]. Other studies have also found that health services staff were often the most important change drivers, but strong management and leadership, acting on patient feedback and streng- thening an open and transparent culture were also vital [21]. Only three studies have explored health professionals’ perceptions of PPI [22-24] showing that progress to- wards achieving meaningful and effective PPI was slow. Deficiencies in financial and human resources, orga- nisational capacity, lack of relevant data, difficulties in supporting the public and accessing seldom heard groups were identified as barriers. Significant changes to the way that PCTs organised PPI in commissioning, indi- cated the start of a cultural shift; however, engaging beyond the ‘easy to reach’ was cited as a barrier [23,24]. An ethnographic study [23] found that health profes- sionals determined areas for service user participation, which covered a wide range of activities; understanding and practice relating to this varied according to pro- fessional ideologies and circumstances. An interesting finding was the challenge embedding user involvement across work streams and authority issues raised. Comparatively little is known about senior nurses’ experiences of embedding PPI, although nurses’ positive PPI support has been noted [6]. Nurses are key NHS frontline staff in terms of direct patient care; they also Figure 1. The involvement continuum. hold key management positions which require an understanding of PPI and its policy implementation chal- lenges. This article reports on a national consultation exercise commissioned by the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) to explore senior nurses’ perceptions of PPI challenges and facilitators in England. Further details of the project can be foun d in the full report [25]. 2. METHODS A qualitative exploratory design utilising focus groups with senior nurses—nurses with leadership roles—across England, was employed. Focus groups have the ad- vantage of making use of group dynamics to stimulate discussion, gain insights and generate ideas to pursue a topic in greater depth. It is a useful technique for ex- ploring values and beliefs about health, disease and systems; they are popular in health promotion and action research, organisational research and development [26]. Being relatively economic and gathering views of many in a relatively short space of time were additional reasons for choosing focus groups [27]. SHAs in England were selected as the first points of contact, having the advantage of being able to access all PCTs and a range of senior nurses across England. All nine SHAs were invited to send representatives to par- ticipate in focus groups. Letters informing and inviting senior nurse managers were sent directly from the RCN to Chief Executives for approval; they allocated a key stakeholder to co-ordin ate and explore the feasib ility of a focus group locally. Stakeholders invited senior nurse managers to participate voluntarily. Recruitment was very slow, although the Chief Executives and key stake-  M. Boudioni, S. McLaren / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 472-480 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 474 holders were reminded with second letters and follow-up phonecalls; reasons given were work overload and other priorities. All communication regarding recruitment and selection took place between June 2008 and October 2008. Ethical approval from a Trust or an external body was not required; the University Ethics Committee was informed for this national consultation. All participants were given an information sheet and consented in writing to participation and digital recor- ding of the focus group. Confiden tiality was ensured and all participants were aware of their right to withdraw. A semi-structured topic guide was drafted in collaboration with RCN and used for all focus groups; they were fa- cilitated by MB, a university researcher, independent from the RCN, SHAs and PCTs. They lasted between 80 and 120 minutes and took place in private meeting rooms at SHAs’ premises. Digital recordings were transcribed verbatim by pro- fessional transcribers. Data was analysed manually by MB using the principles of thematic analysis, thus coding data line by line and forming codes, categories and themes [28,29]. Fifteen sub-themes emerged within the main themes comprising challenges (9 sub-themes) and facilitators (6 sub-themes). Transcripts were checked against recordings for relia- bility. Anonymised summaries of the individual focus groups findings were sent to participants of each group for participant validation. Only two participants res- ponded citing no comments; one of them reinforced a suggestion already made at the group. 3. RESULTS Fifteen senior nurses, with leadership roles and direct PPI experience, employed in eleven PCTs from four SHAs participated. Participants, all RCN members with a variety of roles (Table 1), took part in three focus groups at north, west central and south England locations, con- ducted between September and October 2008. 3.1. Challenges for Effective PPI Nursing Practice (Figure 2) 3.1.1. Limited Resources, Capacity and Time The importance of resources was highlighted among all groups. On one hand, the organisational rationing of general resources allocated to specific projects and events including PPI, was discussed. On the other, al- located PPI resources, capacity and time for PPI activi- ties were also recognised as limited. These limitations also affected the time for change implementation emerg- ing from PPI; in one case, it had taken three to four year s for the recommendations to be implemented. Addi- tional PPI capacity for specific services and subgroups of service users, i.e. children, was also needed. Figure 2. Challenges for patient involvement. Table 1. Professional roles of participants. Focus Group 1 Focus Group 2 Focus Group 3 Director of Quality and Performance (Executive Nurse) Clinical Audit Manager Lead Infection Policy Chief Nurse Head of Service Development (Children Services)Lead Educator Director of Nursing (Executive Nurse) Head of Clinical Strategy Director of Nursing Head of Clinical Governance and Effectiveness Head of Infection Prevention and ControlHead of Clinical Services Head of Service Reform Commissioning Manager (Sexual Health) Matron (Senior Clinical Nurse) Public Involveme nt Lead and Health Improvement Manager Participants spoke extensively about availability of resources, capacity and time at a workforce planning level especially at the initial PPI stages and dev elopment, and also through the different levels of the involvement continuum. Resources were also important when “real” involvement and partnership had been “achieved”, for sustainability, as patients’ expectations from the services might have been increased. Well as you work up the continuum again, if you’re working towards real involvement and real partnership, it takes time and to go out to community groups, to link with Sure Start, to set up your days, to… The maternity  M. Boudioni, S. McLaren / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 472-480 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 475 services are like the Mental Health Services, they’ve got a long history of involvement, haven’t they? And it takes time to work in partnership with the public in whatever way is appropriate for that particular issue or service. (FG2, P4, p24, 19-25) Effective management, setting up and maintenance of memberships, i.e. of Patients Forums, and involving everyone individually also required staff time and re- sources. These elements should also be seen in con- junction with the other responsibilities of nurses, espe- cially when staff shortages were considered. The ad- ditional nursing roles and absorbing different roles with various deliverables could be challenging for PPI. I mean as nurses have taken on more and more of the medics roles, which they have but actually even with skilled nurses, they still haven’t dropped a lot of the other roles that they had… And to a certain extent I think a lot wouldn’t want to as well, it comes to a point where the NHS has worked on goodwill for years, hasn’t it? We’ve all done it but this, you start to get to a point where sometimes it’s just that bit too much and people are starting to get a bit more protective of their time. (FG1, P3, p27, 24-34) 3.1.2. Representation and Recruitment of Patients and the Public High representation of people with certain characteristics in conjunction with their self-selection, were discussed extensively. Patient representatives were often people who had time, were more vocal and active, and perhaps had an interest in specific issues. Other people were less represented, i.e. those who could not read English, were less educated or illiterate, less well off, employed or with childcare issues. Thus, as a result the same patients were involved in all activities creating “real” representation challenges. I’m just thinking about some of the parents we’ve got who can barely read, who are very hard to reach and who would be completely fazed by having to go through that kind of process but probably wouldn’t go through it anyway, we already know that those who are not so well off are less likely to attend because either they’re work- ing or they’ve got issues of, childcare issues or this, that and the other. (FG1, P3, p27, 24-34) Recruiting and influencing people to participate using a variety of approaches were also challenging. Lack of guidelines for getting a wide range of people was high- lighted. Involving the public, “the man in the street” in particular, presented a challenge for many participants. Involving certain population groups and its organi- sational challenges were also discussed. For example, the difficulties and time required for children and young people’s involvement may be challenging to particular groups of professionals, i.e. children’s nurses. Additional challenges were associated with staff being equipped and trained to deal with black and ethnic minorities (BME) and the disabled, i.e. answering telephone lines appro- priately and presentations with interpreters were cited. I think a couple of challenges from my perspective, the BME community and the deaf, the hard to reach com- munities, because there’s nothing more terrifying than standing up doing a presentation, seeing it sign lang- uaged, hearing it being interpreted in Cantonese and seeing somebody else, you know, and are we equipped and trained to do that? (FG3, P1, p17, 6- 10) 3.1.3. Complexity of PPI Implementation The plethora of complex dimensions and involvement areas, i.e. many clinical practices, various professional cultures and subsequent organisational issues created additional difficulties. It was recognised that ch ang es and development had to be implemented across the spectrum of clinical services and professions, so cultural change could be facilitated. The additional complexity of PPI being linked with people’s immediate personal exper- iences, sometimes with unpredictable events, was also recognised. Set up a consultation event, here’s the ground rules, here’s the parameters, here’s what we will do with your information, here’s what we (it is easy), but we’re talking about day to day lived experiences that pop up when you least expect them, or you get put in a situation where you hear something. (FG3, P1, p17, 6- 10) 3.1.4. National PPI Policy and Changes in Structures Additionally, concerns were expressed that changes in national PPI policies and bodies, notably, the abo- lishment of Community Healt h Cou ncils and PPI Fo ru ms and the creation of LINKs, had temporarily brought wider engagement to a halt. …because we had a very active Patient and Public Involvement Forum, the LINKs host wasn’t appointed until the beginning, their contracts started at the be- ginning of August, then the manager within the host… host organisation was identified to start the work went off sick, you know, and now we’re here into September and really, and there’s a sense of frustration building amongst particularly the old PPI forum members, so here we are six months on from the abolishment of the forum and they still haven’t got an engagement group. (FG2, P2, p20, 44-51 and p21, 1-4) NHS structural changes also affected the implemen- tation of the world class commissioning competencies, as potential co llaborations with patient representatives were interrupted. These changes had also led to organisational and team changes that subsequently had a PPI impact, i.e.  M. Boudioni, S. McLaren / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 472-480 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 476 amalgamation or restructuring of teams impacted on PPI. Additionally, the Patient Advice and Liaison Services (PALSs) were not considered well-integrated within the whole NHS system; dealing with patients with specific issues was considered to limit PALS’ objectiveness of feedback. 3.1.5. Commissioning Limitations: Organisational Issues It was believed that PPI projects were still very tokenistic; there were some good examples, but the world class commissioning PPI competencies, had not yet been reach- ed. If the organisational participation culture, as revealed from the organisational strategy and actions, was not open and transparent, then PPI was not perceived to be effective. Control and representativeness were other issues to be considered. PPI controlled either by com- mittees or people, staff or patient representatives was considered problematic; this might be linked with user representation issues discussed. …I think the committees, it’s how the organisation is set up, you can have co ntrolling PPI, can’t you? You can have… it was Dignity and Compassionate Care group we’ve just set up and someone suggested a name and obviously new into the organisation I didn’t know who this person was, so I did a bit of, well, you know, she’s been around a few years, she’s been awarded an OBE for her contribution to the NHS but, you know, does she truly represent a user? So, you know, it’s that control, you can have a control system that says yes we have got PPI but then when you sort of dig down, you think is that really Joe Bloggs on the street’s view? (FG2, P3, p21, 21-33) 3.1.6. Staf f PPI Awareness a nd Negative Atti t ud es Participants across groups reco gnised low PP I awaren ess among nurses. This was expressed with nurses per- forming patient involvement activities, i.e. informing, sharing and discussing care issues with patients, without recognising or labeling them as such. They actually wel- comed the informality and flexibility; th ey were resistant in such labels. I would want, not want to label it as I have PPI, you know, I had a PPI today, I just think that it would be a complete disaster because we’d lose some of the freedom but I do think nurses would benefit from understanding how we could use the information in perhaps a more beneficial way and they wouldn’t feel like they’re not doing it but I wouldn’t like to lose that informal… (FG2, P1, p6, 1-5) A diversity of medical attitudes, both PPI positive and negative, was also identified. These attitudes may have further implications for the PPI nursing practice; for example more effort may be required for nurses to ensure PPI good practice. …some of our consultants are fabulous, absolutely fabulous and we’ve got certain dynamic groups, diabetes and various other things but we’ve got others where the patients would never be, have a voice if it was down to the doctor. Whereas I don’t think nurses think like that, so I think it is very relevant about how boards are made up, where we’re going with all of these new Trusts, who’s the decision making people and how we involve our customers, so I do think it’s quite crucial. (FG2, P1, p19, 40-47) 3.1.7. Lack of Feeding Back Evidence on Patients’ Experience The mentioned resistance of nurses towards labeling cer- tain activities as PPI had consequences on capturing and measuring patient involvement and experience properly. Thus PPI evidence was not collected; it was difficult to be identified an d demonstrated, resulting to limited feed- back to the management. Clinical and other decisions were based only on demonstrable or available evidence and not on anecdotal patient experiences; thus the pro- cess of shaping services accordingly was hindered. …actually sometimes it’s very hard to find the evi- dence to actually demonstrate that and say for instance there might be notice of a meeting but they might not say “xx is the patient representative”, you know, so it maybe just had a list of names… You know, how can you de- monstrate this for your, this particular assessment pro- cess or that process? Actually because it’s part of what we do on a day to day. (F G2, P2, p14, 15-24) 3.1.8. Man agement of Patient and Publi c Feedb ack and Expectations Effective management of patient and public expectations was also perceived as difficult, requiring good judgment and balancing all complexities around them. Ineffective management could cause delays in resolving issues and result to patients’ frustration. …and they’re still at the end of that session frustrated because we still haven’t worked out how we’re going to get them their tablets more quickly. And they’ve been really honest. I’m frustrated because I can see that it should be simple but I know it isn’t because of all these other complex things happening, therefore our part- nership’s thwarted really because we can’t get to where they want to get to very easily. (FG1, P1, p21, 27-33) In some occasions, utilising the feedback, expectations or outcomes from PPI activities to shape services was difficult. This was due to practical, financial or orga- nisational reasons. Incapacity to fulfill certain expec- tations, because they were outside somebody’s juris- diction was also hig hl i ghted.  M. Boudioni, S. McLaren / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 472-480 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 477 P3: My concern is that we can sort them and don’t necessarily use the information we get to shape the ser- vice if we’re not careful. P2: Or that we don’t have the resources to provide. P3: Yes, which is where the honesty bit comes in. (FG1, p12, 38-4 4) 3.2. Facilitators for Effective PPI Nursing Practice (Figure 3) 3.2.1. Nurses ’ Rol e and Informal PPI Ac tivities The nurses’ skills, their informal caring and interactive activities-although not labeled as PPI were recognised as facilitators. General comments were made about nurses having transferable skills and gaining new skills all the time. The nursing carin g role included continuous rapport with patients, engagement and on-going feedback from them. This feedback, including comments, com- pliments and complaints—when evidenced—was taken into account in shaping services. As a profession I think it is… that caring side of nurs- ing, that one to one rapport that you get when you’re caring for a patient and the feedback…, so I still have that engagement and I know as leaders we’re very con- scious of the fact that we need to be taking on board patient stories and we need to be identifying good and bad comments, you know, that we’re getting back from the patients and acting upo n them and I think that’s how we’re going to shape our services. (FG1, P4, p2, 24- 32) Nurses were considered to conduct PPI in practice, in every single interaction with patients, even if not reco- Figure 3. Facilitators for patient involvement. gnised as such. One to one and non-patronising in- teraction with patients, listening to communities, indi vidual patients and working towards their best care and services were considered to be both PPI and nursing professionalism elements. They were seen to be integral to a nurse’s role at different levels and settings, i.e. in community or acute settings. However, it was recog- nised that this might vary in different departments, clinics, or wards. In maternity, for example, involve- ment might be greater than in other clinics. In addition , specific professional roles such as the modern matrons were considered having a better PPI understanding than others. I think if you looked at the, the modern matron role that was brought in they do have an understanding of public patient involvement as well as patient safety and the governance aspects but maybe the frontline nursing staff, it’s about that one to one interaction for patients. (FG3, P1, p27, 11-14) 3.2.2. NHS Policy Changes and Subsequent Cultural Change It was recognised that most recen t NHS national policies had been patien t-centred and facilitated a cultural ch ange, including a focus on self-care and self-management, both closely related to PPI. Although new developments, i.e. LINKs at the time, were recognised as capable of bringing changes and shaping services, lack of clarity about their processes and membership were also men- tioned. 3.2.3. Commissioning PPI Competencies The world class commissioning PPI competencies and organisational drivers for their implementation had some- how influenced and facilitated PPI. The push for in- tegrated services and the recognition of the third sector also reinforced patient-centred services. Well, yes, one of the world class commissioning com- petencies is around Patient Public Involvement… It’s about your structure as a commissioning PCT and how you’ve structured yourself and what your hierarchy looks like and how you’re going to engage the public in, right at that front end, your health needs assessment works because at the moment they’re kind of brought in after that, aren’t they? (FG3, P1, p32, 28-36) The organisational strategy or requirements-revealing perhaps a positive pa rticipation culture, i.e. patient repre- sentatives on the Board-facilitated higher involvement le vels. Organisational structures might also enable involve- ment at the higher level. I mean for instance our Board now has two patient representatives who are, and their function has evolved and their participation in that Board has evolved, so for  M. Boudioni, S. McLaren / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 472-480 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 478 instance when our new PCT was first set up one of the early Board meetings, our Chairman made the comment that said this is a meeting held in public, not a public meeting. (FG2, P2, p20, 9-13) 3.2.4. Other PPI Supportive Frameworks Several participants referred to existing frameworks, i.e. the Essence of Care Standards, the Knowledge and Skills Framework, the Standards of Nursing, an d customer care standards. Their relevant to PPI competencies or ele- ments were identified as helpful for PPI overall. Some participants also referred to evaluation, monitoring and appraisal processes, dealing with staff developmental issues, including PPI, as PPI supportive. The consensus in one group was that the existing competency frame- works were sufficient and adding another framework would make clinicians feel overload ed. A participant felt that the continuum of involvement could be mapped through existing frameworks, although its implemen- tation needed work. ….because you’ve got the continuum of involvement that is recognised and actually in a sense you could put your different levels of involvement as with the gradings, you could make a model basically, you could use the continuum of involvement and then you’ve got your essence of care standards, you’ve got your KSF… you’ve got your customer care standards, which is all integral into a nurses role at different levels in different ways, wherever they may be working in the community or in an acute setting or in a community hospital. So actually there is a kind of framework there already, it’s how you apply it. (FG2, P4, p29, 25-36) 3.2.5. Recognition of PPI Benefits Participants referred to the PPI benefits; notably that it was powerful, influential and the whole process provided the argument for cultural and organisational change. The awareness and recognition of these benefits facilitated effective PPI further. P4: And I think nothing’s more powerful is it, than a patient or a carer challenging a consultant or a doctor or a nurse or a Social Worker? P2: It’s very powerful. P4: To, or the Head of Social Care, it is much more powerful and it actually speaks volumes, you know, that they will turn and pull so mething up… (FG3, p4, 36-42) It was also recognised that the core of true patient care started with asking p atients’ about individual needs. Real involvement should also have a re-energising effect for everybody in the system. Other benefits included better understanding of the NHS bureaucratic system, chal- lenging NHS staff, bringing in simple changes, speeding up procedures, making the NHS more transparent and accountable. 3.2.6 Organisational Feedback to Staff Providing feedback to staff on various aspects of patient experiences and involvement, for example, patient expe- rience surveys, complaints and various incidents, was considered another facilitator. Organisational feedback could be linked with action plans. The feedback provided to individual nurses could help them recognise the different aspects’ importance and any actions or reso- lutions necessary. Well we do a lot of feeding back to staff on just, of things that we’ve done, so obviously our satisfaction surveys, it would, you kno w, it’s a key thing to go back to staff and involve them in determining an action plan. And but also things like complaints where we know we’ve made a change and on a regular basis we’ll kind of list some of those things so some of the issues that arose, so even from a complaint or a survey or an audit or some- where that’s involved the patient and then kind of outline what was a result really, kind of what was the outcome for that? (FG2, P 5, p6, 2 6-33) 4. DISCUSSION Although the consultation exercise yielded valuable in- sights into the evolving process of implementing PPI in NHS Trusts in England from a senior nursing perspective —which is under-researched—its limitations should be considered. Five focus groups, representative of nine SHAs, were initially intended. However, recruitment and their facilitation organised in collaboration with Trust gatekeepers, proved very difficult. Issues such as po- tential participants’ workload or perhaps not-treating the topic as a priority need to be considered; these may also help us understanding PPI perceptions of these profes- sionals. The findings are based on three focus groups only, and fifteen self-selected participants representing four SHAs; this cannot preclude bias. Furthermore, participants were all in strategic senior management po- sitions; their experiences are not necessarily repre- sentative of a wider nursing PPI experience. This con- sultation was conducted in late 2008. However, guide- lines for PPI implementation have not be en issued yet in England, and another study exploring senior nurses’ ex- perience of PPI has not been identified internationally. Importantly, similar issues may affect implementation of patient and public involvement not only in England, but internationally. With regard to PPI challenges, participants’ exper- iences were consistent with those identified elsewhere;  M. Boudioni, S. McLaren / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 472-480 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 479 limited resources, time, complexities of working across service boundaries and professional cultures [22,23]. An interesting new finding was the impact on continually expanding nursing roles of taking on new PPI and other responsibilities, which co uld result in delivery problems. Participants also identified difficulties recruiting repre- sentative patients, with concerns expressed about hard to reach groups and the need for recruitment guidelines; these findings were consistent with those of others [22, 24]. PPI control by committees and professional staff were seen to be problematic in terms of commissioning practices. Others have also found that health profes- sionals determined the areas of participation by service users [23]. Although many medical staff were supportive of PPI, some participants had encountered unhelpful at- titudes; an earlier study [6] noted similar issu es raised by giving up c ontrol. Important new findings emerged in relation to PPI facilitators. Significant facilitators identified here corres- ponded to some world class commission ing pr iorities [9]. Participants discussed services based on patient expe- rience, people’s choices, control and more person- alisation, alongside work with community partners and engagement with public and patients, all of which were highlighted within the world class commissioning vision, associated competencies in England. Similar issues have also been iden tified in national and internation al policies elsewhere [2-4]. A strong message was that another PPI implementation framework was not needed, as some PPI related benchmarks and competencies were incorporated in the Essence of Care and Knowledge and Skills Frame- work in England [30,31]. It appears that nurses felt overwhelmed by frameworks and regulations. A con- sensus existed that nurses in practice, because of the nursing characteristics and nature, performed PPI in its pragmatic sense, even if they did not recognise or label it as such. PPI, its learning and achievement has not been given sufficient recognition, nor has it been robustly shared and systematised-especially within practice. This is perhaps one of the most important findings, together with that of the need for open and transparent feedback of patient experience evidence to shape services and expedite action planning at the frontline [21]. 5. CONCLUSIONS This consultation explored “an emerging productive part- nership”, with regard to senior nurses enabling patient and public involvement. Notwithstanding its limitations, rich qualitative data shed light on involvement barriers and facilitators, as experienced by senior nurses in ma- nagement positions, an area that is under-researched. New findings highlighted the importance of two-way feedback of evidence based on patient experience be- tween frontline nurses and managers; the utility of exist- ing policy and service frameworks to enable imple- mentation of involvement mechanisms; the need for guidelines to recruit hard to reach groups and the poten- tial for a negative impact of relevant responsibilities on expanding nursing roles. Of particular interest, was the view that nurses performed patient involvement in a pragmatic sense, by virtu e of t he n at u re o f n ursing. International and national policies elsewhere [2-4], and NHS policies in England [5-10,12], place a great emphasis on patient involvement and empowerment. However, these findings suggest that although progress has been made, many challenges still remain in trans- forming the way that healthcare services in England are commissioned and provided, if current aspirations on shared-decision making as “the norm” are to be met [8]. Enhancing awareness about patient involvement could benefit the development of more effective monitoring and feedback mechanisms at organisational levels. In addition, the creation of nursing involvement networks may be helpful in harnessing collective experiences to benefit patient-centred services and empowerment of patients, in England and elsewhere. 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank all the participants, senior nurses working in different organisational settings in four Strategic Health Authorities in England, for giving up their time to take part in this consultation. We would also like to thank Professor David Sines for his support, the late Professor Bob Sang for his initial contribution and his comments on the project, and Dr. Sophie Staniszewska for her comments on the final report. Ms Helen Caulfield of the RCN Policy Department negotiated access within NHS organisations to enable focus groups to be con- ducted. REFERENCES [1] World Health Organisation (1986) Ottawa charter for health promotion. The move towards a New Public Health. WHO, Ottawa. [2] World Health Organisation (1997) The Jakarta declara- tion on leading health promotion into the 21st century. 4th International Conference on Health Promotion, Ja- karta, 21-25 July 1997. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previou s/jakarta/declaration/en/# [3] World Health Organisation (2009) The European Health Report 2009: Health and health systems. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen. [4] Fallberg, L. and Mackenney, S. (2004) Conclusion. In: Mac- kenney, S. and Fallberg, L., Eds., Protecting Patients’ Rights? A Comparative Study of the Ombudsman in Health- care, Radcliffe, Oxon, 137-148. [5] Department of Health (2003) Strengthening accountabil- ity: Involving patients and the public. DH, London.  M. Boudioni, S. McLaren / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 472-480 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 480 [6] Department of Health (Farrell, C.) (2004) Patient and pu- blic involvement in health: The evidence for policy im- plementation. DH, London. [7] Department of Health (2004) “Getting over the wall” How the NHS is improving the patients’ experience. DH, London. [8] Department of Health (2010) Equity and excellence: Lib- erating the NHS. The Stationary Office, London. [9] Department of Health (2007) World class commissioning: Vision summary. DH, London. [10] Department of Health (2008) High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. DH, London. [11] Involve (2005) People & participation: How to put citi- zens at the heart of decision-making. Involve, London. http://www.involve.org.uk [12] Department of Health (2008) Real involvement: Working with people to improve services. DH, London. [13] Coulter, A. and Ellins, J. (2006) Patient focused interven- tions: A review of evidence. Quest for quality and im- proved performance (QQUIP). The Health Foundation, London. [14] Coulter, A. and Ellins, J. (2007) Effectiveness of strate- gies for informing, educating and involving patients. British Medical Journal, 335, 24-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80 [15] Nilsen, E.S., Johansen, M., Oliver, S., Oxman, A.D. (2010) Methodological considerations involved in devel- oping healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. Cochrane Col- laboration, John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey. [16] Sang, B. (2009) Chapter 22. User involvement: The in- volved and involving community health care nurse. In: Sines, D., Saunders, M. and Forbes-Burford, J., Eds., Community Health Care Nursing, Wiley-Blackwell, Ox- ford, 352-362. [17] National Centre for Involvement (2007) A baseline as- sessment of the current state of patient and public in- volvement in English NHS trusts. NCI, Warwick. [18] National Centre for Involvement (2008) The current state of patient and public involvement in NHS trusts across England; findings of the national survey full report. NCI, Warwick. [19] Picker Institute Europe (2007) Patient and public involve- ment in primary care commissioning. Picker Institute Europe, Oxford. [20] National Audit Office (2007) Improving quality and safe- ty progress in implementing clinical governance in pri- mary care: Lessons for the new primary care trusts. The Stationery Offic e , L o n d o n . [21] Healthcare Commission (2009) Listening, learning, work- ing together? A national study of how well healthcare organisations engage local people in planning and im- proving their services. Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, London. [22] Chishold, A., Redding, D., Cross, P. and Coulter, A. (2007) Patient and public involvement in PCT commissioning: A survey of primary care trusts. Picker Institute Europe, Oxford. [23] Fudge, N., Wolfe, C.D.A. and McKevitt, C. (2008) As- sessing the promise of user involvement in health service development: Ethnographic study. British Medical Jour- nal, 336, 313-318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39456.552257.BE [24] Picker Institute Europe (2009) Patient and public engage- ment. The early impact of world class commissioning: A survey of primary care trusts. Picker Institute Europe, Oxford. [25] Boudioni, M. and McLaren, S. (2009) Nurses and patient and public involvement: A consultation in four strategic health authorities in England. London South Bank Uni- versity, London. [26] Barbour, R.S. and Kitzinger, J. (1998) Developing focus group research: Politics, theory and practice. Sage, Lon- don. [27] Darlington, Y. and Scott, D. (2002) Qualitative research in practice: Stories from the field. Open University Press, Buckingham. [28] Boyatzis, R.E. (1998) Transforming qualitative informa- tion: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage, London. [29] Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77- 101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [30] Department of Health (2007) Essence of care: Bench- marks for care environments. Department of Health, Lon- don. [31] Department of Health (2004) The NHS knowledge and skills framework: Development and review process. De- partment of Health, London.

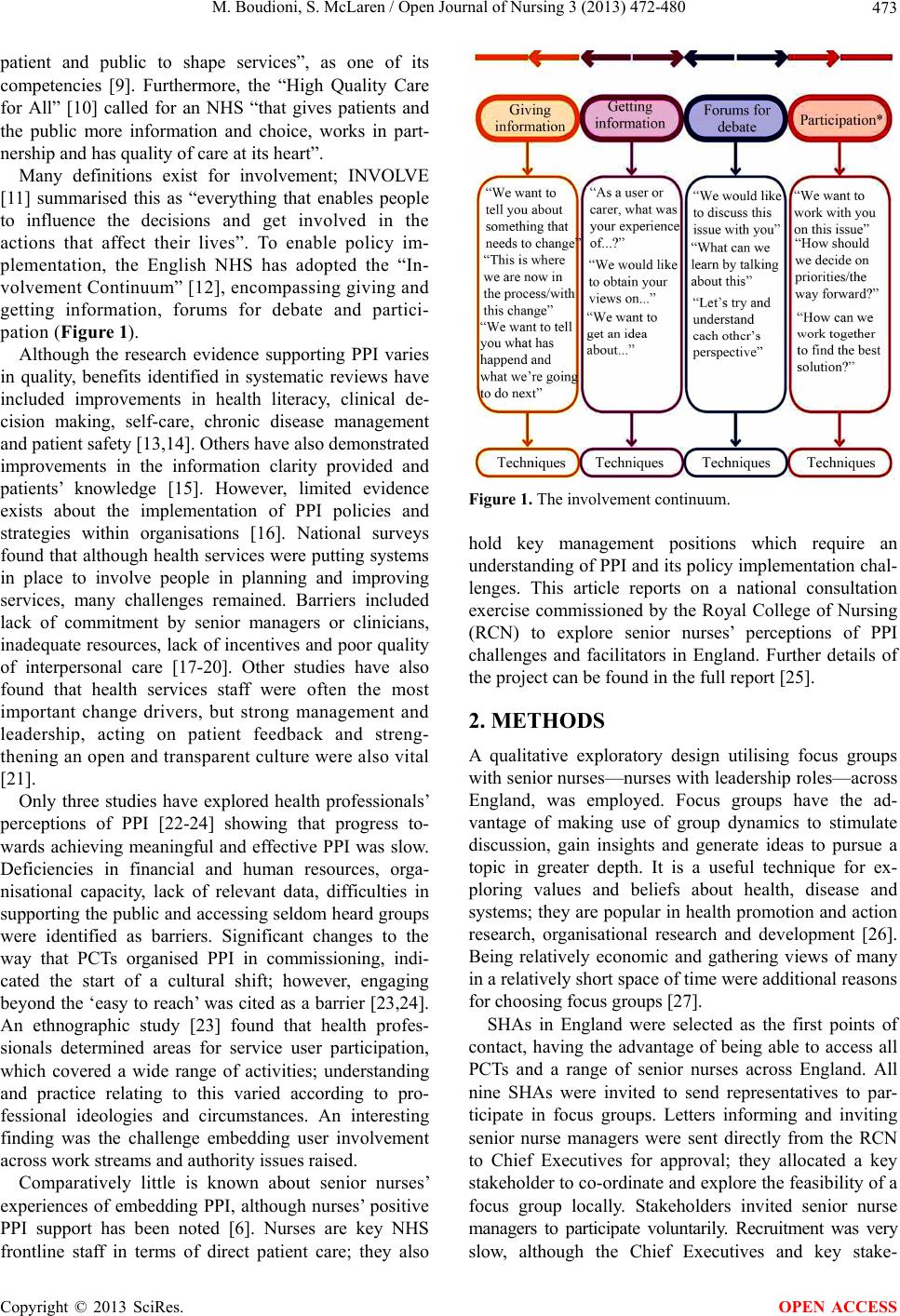

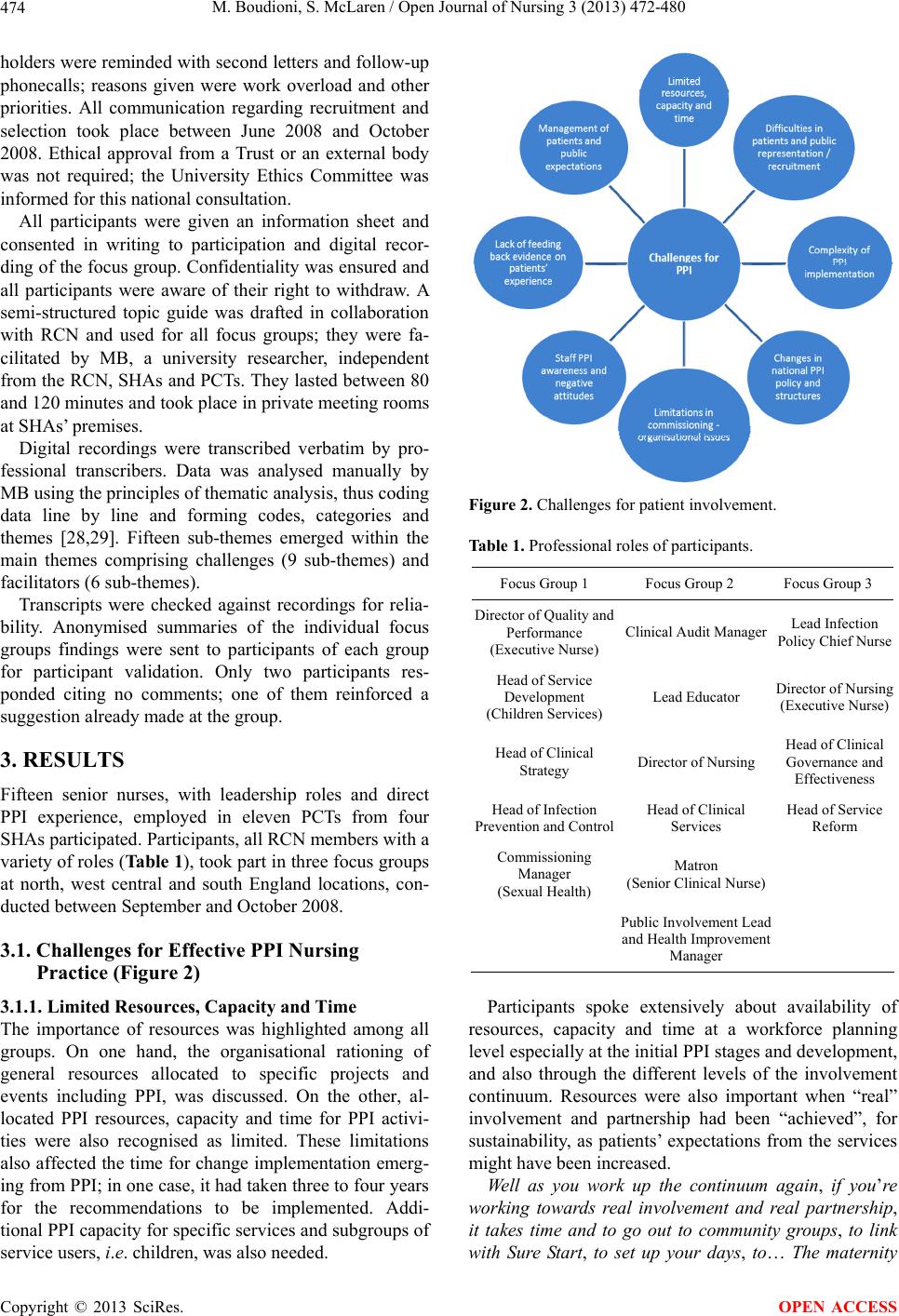

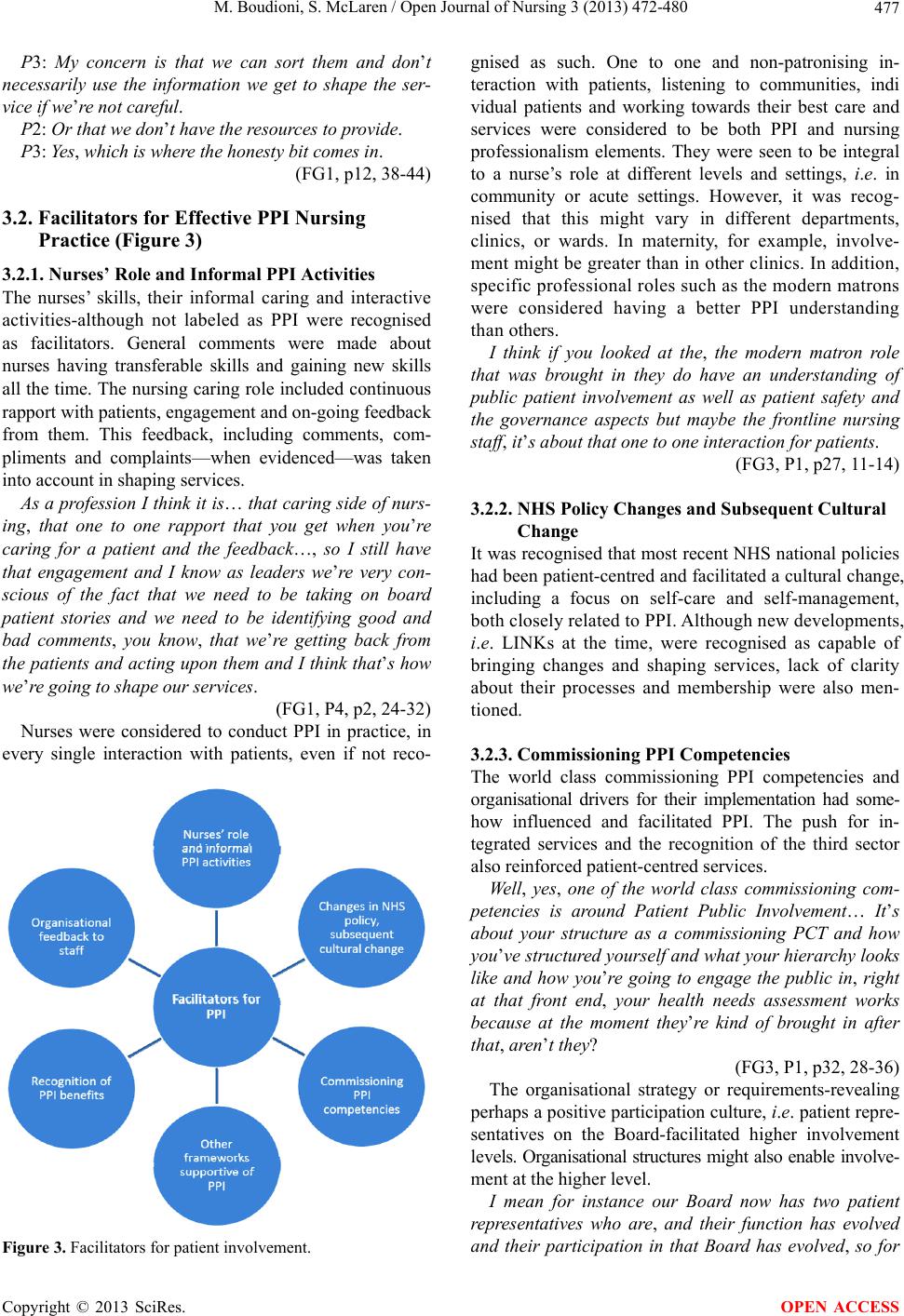

|