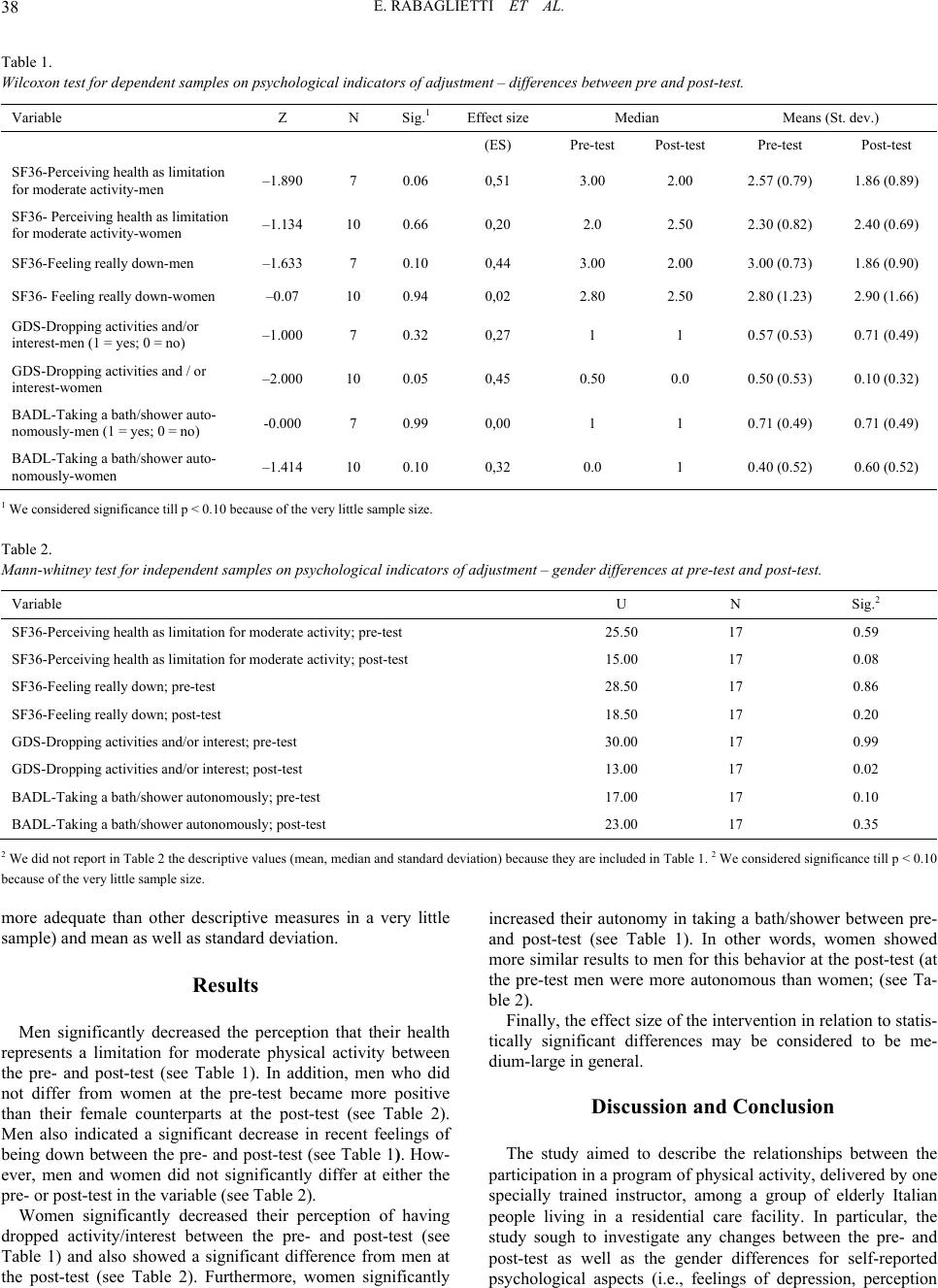

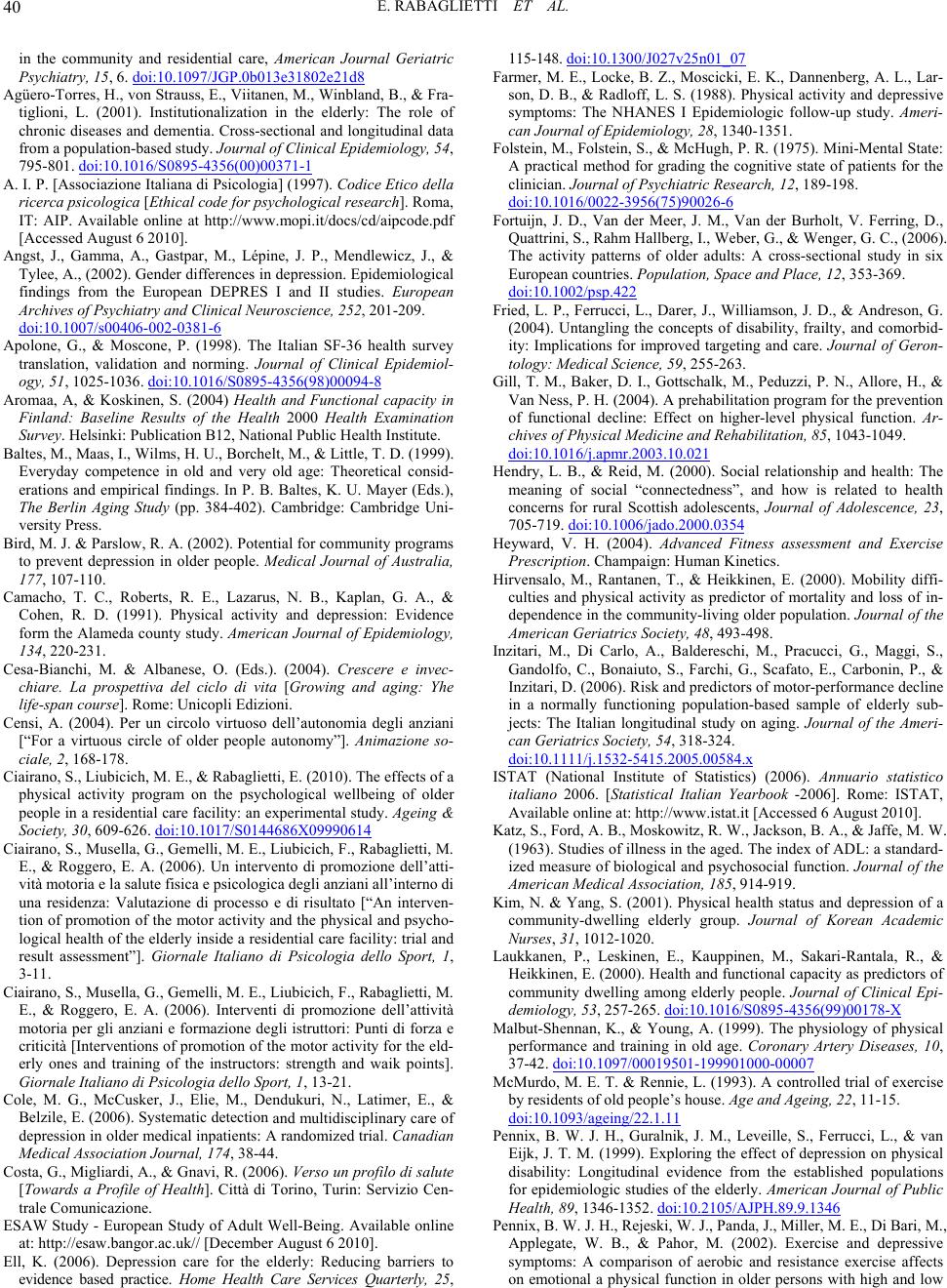

Psychology 2011. Vol. 2, No. 1, 35-41 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.21006 Gender Differences in the Relationships between Physical Activity and the Psychological and Physical Self-Reported Conditionof the Elderly in a Residential Care Facility Emanuela Rabaglietti1, Monica Emma Liubicich2, Silvia Ciairano1,2 1Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy; 2Motor Science Research Center, SUISM (University School of Motor & Sport Sciences), University of Turin, Turin, Italy. Email: emanuela.rabaglietti@unito.it Received November 23rd, 2010; revised December 13 rd, 2010; accepted December 28th, 2010. The present study aimed to investigate the differences pre- and post-test after introducing an aerobic program of physical activity in the psychological and physical self-reported condition (feelings of depression, perception that one’s own health limits physical activities, negative self-perception, and execution of activities of daily liv- ing) of a group of elderly Italians deemed to be slightly compromised based on the Mini Mental State Examina- tion (MMSE: median 23) and living in a residential care facility in northern Italy. The self-reported measures were drawn from the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), and the Italian short version of Scale of basic Activities of Daily Living (ADLs). The participants were 17 elderly people of both genders (10 women and 7 men), with a median age of 85.56 years. The findings (we used non-parametric statistical techniques) showed that: 1) dropping activities/interests (due to feelings of de- pression) and taking a bath/shower autonomously (from activities of daily living) improved in women; 2) per- ceiving health as a limitation to moderate physical activity and feeling really down (based on negative self-perception) improved in men. These results underscore the importance of considering gender differences when evaluating the relationships between participation in physical activity and the psychological and physical condition of the elderly. Keywords: Elderly People, Training, Psychological and Physical Condition, Ge n de r Differences. Introduction Demographic data and epidemiological studies have demon- strated that the prolongation of the life span leads to increasing disabilities in the oldest and frailest group of the population (Aromaa & Koskinen, 2004; Stenzelius et al., 2005; WHO, 2002). However, data also indicate that this age group repre- sents the fastest growing population group. The United Na- tional Department of Economics and Social Affairs (United Nation, 2009) reported that people older than 80 represent 1.5% of the worldwide population; this proportion is expected to increase to 4.3% by 2050. The same report also highlighted that the current gender difference - namely, that elderly women outnumber elderly men two to one - will disappear over time. These universal tendencies will ultimately transform the role of the elderly. However, the loss of autonomy together with the increasing likelihood of disease that often accompanies aging makes research into preventive and health promotion interven- tions increasingly important as it may contribute to improving seniors’ quality of life. Several aspects remain unclear, especially with respect to very old people and their institutionalization in residential care facilities. Among all the other potential protective factors, we are particularly interested in investigating the relationships between physical activity and the psychological and physical well-being of the elderly. Nevertheless, very few studies have investigated gender differences among very old people or among those in non-normative life conditions associated with residen- tial care facilities. This lack of research likely stems from the fact that currently the mean life expectancy among men is much lower than that among women, making it difficult to constitute groups of participants large enough to investigate the compari- son between genders. The life condition of the elderly institutionalized in residen- tial care facilities is unique with respect to the general popula- tion based on several indicators of psychological adjustment, including depression. For instance, elderly people living in residential care facilities have a higher probability of suffering from different forms of depression than their same-aged peers still living independently (Soondool, 2008). Concerning this, Baltes and collaborators (Baltes, Maas, Wilms, Borchelt, & Little, 1999) highlighted the controversial issue of causal rela- tionship between depression and autonomy, suggesting that the loss of autonomy constitutes the causal premise of the subse- quent high level of depression. However, family support still represents an important protective factor against the develop- ment of depression even among the elderly in residential care living conditions (Hendry & Reid, 2000; Kim & Yang, 2001). Furthermore, depressive conditions, which concern about one third of the general population older than 50 years, increase exponentially with age and are much more common in women than men (Bird & Parslow, 2002; Ell, 2006). Such depressive conditions often become a primary cause of disabilities, indi- vidual discomfort, high use of health services, and even suicide  E. RABAGLIETTI ET AL. 36 (Steffens et al., 2000; Serby & Yu, 2003; Cole et al., 2006). Changes in living conditions when the elderly are institu- tionalized in residential care facilities, which thus far has af- fected more women than men, represents a relevant challenge for individuals’ well-being. An elderly person often loses inter- est in things and activities not included in the immediate living area. As such, the elderly seem to anchor themselves and/or concentrate on the immediacy of the present, developing intol- erance toward change and frustration as well as often sharply reducing the range of social relationships while giving up self-determination and autonomy (Cesa-Bianchi & Albanese, 2004). Thus, residential care facilities must offer environmental conditions that help residents maintain and develop residual skills. In these institutions the quality of care relationships is much more important than the quality of care in general (Censi, 2004). The research by Anstey, von Sanden, Hons, Sargent-Cox, Hons and Luszcz (2007) on the passage from the normative condition of independent living to living in residential care facilities showed that this transition is very delicate. In fact, during this transition, depressive symptoms increase before the onset of physical and cognitive decline. Nevertheless, a high interindividual variability occurs with respect to reactions dur- ing this transition. Subjective well-being and self-concept were shown to be more similar than expected in men and women as well as strongly related to the economic and educational level of individuals and their social networks (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001). Several studies have demonstrated that motor difficulties, disabilities in mastering daily activities, and serious injuries are risk factors that increase the likelihood of institutionalization (Hirvensalo et al., 2000; Laukkanen et al., 2000; Agüero-Torres et al., 2001; Rockwood et al., 2001). Conversely, a longitudinal study by Farmer, Locke, Moscicki, Dannenberg, Larson, and Radloff (Farmer et al., 1988) showed that constant physical exercise reduces the risk of developing depression on the long term. Furthermore, the adoption of active lifestyles - even at advanced ages - fulfills the role of a general protective factor for health in both genders (Camacho et al., 1991). A study in- volving old people with depressive symptoms (Pennix et al., 2002) found that, at a follow-up after 18 months, aerobic activ- ity focused on walking reduced depression more efficiently than other kinds of physical training focused on muscular training for resistance. With respect to gender differences, we found contrasting previous findings. According to Stephens (Stephens, 1988), the association between physical activity and psychological health is stronger in women than men. This is also consistent with the study of Smith and Baltes (Smith & Baltes, 1999) that through cluster analysis showed as in most cases the less desirable pro- files belong to women rather than to men. Meanwhile, Yanagita et al. (2006) highlighted a strong correlation between physical disability and depression in men. However, movement was shown to be effective in improving motor skills useful for re- maining independent as long as possible in the elderly of both genders (Fried et al., 2004; Gill et al., 2004). Some studies (Malbut-Shennan & Young, 1999; Sullivan et al., 2007) indi- cated that participation in aerobic and resistance training may achieve changes in the individual’s functioning in terms of maintaining independence and reducing feelings of fatigue, even in ver y ol d people of about 80 years. Taking into account scientific evidence that has underlined the strong relationship among decreased motor skills, worsened health, and increased depression (Pennix et al., 1999), physical activity may fulfill a relevant preventive role, especially when the elderly person is in a condition of physical and/or psycho- social frailty, against the underlying processes of both physical and emotional discomfort. Health and skills for mastering daily living are fundamental in the life of every person. However, they become even more important for maintaining satisfactory levels of quality of life during aging. Furthermore, the increas- ing number of old people - including males - in reside ntial care facilities suggests the need to investigate the presence of gender differences in the relationship between physical activity, which is a relatively cheap and easy to introduce training, and general wellbeing also in order to make this training more efficient. The Study Aims The present longitudinal study represents the continuation of some our previous studies (Ciairano et al., 2010; Rabaglietti et al., 2010) that already demonstrated the positive effect of an aerobic program of physical activity on positive self-perception, the perception that health limits physical activities, and physical performance and condition among elderly Italian people in residential care facilities. In the present study, we further ex- tend our interest, focusing on the gender differences in the psychological and physical self-reported conditions during pre- and post-testing among a elderly group of people who partici- pated in an aerobic activity. Specifically, we examined a group of elderly living in a residential care facility and who were shown to be slightly impaired according to the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE). The study aims to describe the changes between the pre- and post-test separately in old men and women and the gender differences at each wave for self-reported psychological aspects (feelings of depression, perception that one’s own health limits physical activities, and negative self-perception) and physical aspects (execution of activities of daily living). Description of the Intervention The intervention was introduced in a residential care facility in northern Italy that is a private structure linked to public health service through a funding agreement. This structure was selected at random among all those present in the region. Par- ticularly it was selected among those with a intermediate condi- tion in terms of social and economical levels of the elderly. This facility houses both self-sufficient (i.e., they can still walk, eat, and go to the bathroom by themselves) and dependent (i.e., requiring assistance with essential activities of daily living) elderly people. It also provides self-sufficient guests with a daily physiotherapy session. The intervention consisted of one 45-minute session per week for 15 weeks (roughly 4 months). The intervention was addressed to a group of self-sufficient older people living in a residential care facility. The sessions were conducted by one instructor who had a university degree in physical education and sports-related fields and specialized in physical fitness  E. RABAGLIETTI ET AL. 37 training for the elderly (Ciairano et al., 2006a; Ciairano et al., 2006b). Particularly this instructor was selected among those who (during the previous academic year) successfully passed the subject of “Health and the elderly” getting a grade upper the 95% percentile of the grades distribution. The instructor re- ceived a little reimbursement for the implementation of the program of physical activity and he got the acknowledgment of his activity as a kind of professional practicum. The aerobic program aimed to achieve five main goals: • to improve respiratory function through deep breathing techniques; • to promote the awareness of incorrect or compensative posture and to learn to modify these problems on one’s own; • to execute movements addressed to the various joints, trying to reach the maximum possible exertion, without exceeding personal limitations; • to reach a correct perception of one’s body in various conditions of static and dynamic equilibrium; and • to strengthen interpersonal relationships and re disc over the joys of “playing” and using abilities that may have been perceived as lost by exercising in pairs or small groups. The intervention was tailored to engage participants gradu- ally and interest them in a variety of different kinds of activities, using both conventional and unconventional instruments (e.g., stools, sticks, clubs, hoops, balloons, foam balls, towels, paper cups, pins, bowls, paper tissues, scarves, and trays) as well as stressing playful qualities. In addition, the instructor received daily updates by other personnel regarding participants’ condi- tions, including minor physical problems, in order to avoid potentially dangerous movements. Furthermore, special care was taken to provide participants wi th plenty of time to execut e each movement, avoiding activities that could have been per- ceived as too intens e, embarrassing, or difficult. Participants The director of the residential care facility, who is a trained physician, selected the elderly people to participate in the aero- bic program from among all those living in the facility. The two criteria for inclusion were: 1) self-sufficiency (as previously defined herein), and 2) absence of serious chronic and/or acute diseases, which was verified directly by the researchers. The MMSE was used to evaluate cognitive capacity (Folstein, Fol- stein & McHugh, 1975). All participants were assessed as mild cognitively impaired; the median score was 23, and the MMSE tests scored ranged between 18 and 24. The participants were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and con- fidential. All those selected agreed to participate and gave in- formed consent, in accordance with Italian law and the Asso- ciation of Italian Psychologists’ ethical code (A.I.P., 1997). The group of participants comprised 17 elderly people, in- cluding 7 (41%) men and 10 (59%) women. The median age was 85.00 years (Mean = 85.23, SD = 6.05; range 74-96). All participants were permanent residents of the residential care facility. All except one, who was born in the center of Italy, were from the same region in which the facility is located. With regard to marriage status, the majority (N = 10, 59%) were widows, 29% (N = 5) were married, and the remaining had never been married (N = 1) or were divorced (N = 1). In terms of education, two levels were considered: ‘low’ corresponding to compulsory education (primary and secondary school), and ‘high,’ corresponding to additional non-compulsory education (including high school and university). The average level of education for both men and women in the sample was similar at the national statistics of age-matched population (ISTAT, 2006; Costa, Migliardi & Gnavi, 2006). Among participants, 65% (N = 11) had received compulsory education compared to about 70% in the national population. Former occupations were di- chotomized into manual (N = 12, 71%) and non-manual labor (N = 5, 29%). This ratio closely reflects the national population. In addition, 53% (N = 9) had never participated in organized exercise or sport activities. Of those who had (N = 8, 47%), the preferred sports were bowling, gymnastics, soccer, and walking. No gender differences emerged with respect to age (U Mann-Whitney = 29.00, p = 0.91), former occupation (2 = 3.57, d. f. = 3, p = 0.31), or level of education (2 = 0.71, d.f. = 1, p = 0.79). However, a difference did exist with respect to marital status (2 = 7.09, d. f. = 3, p < 0.03): Women were more likely to be widowed than men (80% vs. 17%), while men were more likely to be married than women (50% vs. 20%). In addition, the two persons who were not married (i.e., never married or divorced) were both men. Procedure We selected two questions from the Italian version of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) (Apolone & Moscone, 1998; Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). The first investigates the perception of limitation to moderate phys- ical activity according to one’s own health (How much your health limit you in Moderate activities, such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or riding a bicycle range of possible answers: 1 “not at all” - 3 “much”). The second investigates how many times in the last four weeks the person has felt really down (Have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up? range of possible answers: 1 “never” - 3 “always”). Participants also answered a question from the Italian short version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (Segulin & Deponte, 2007; Yesavage et al., 1983): Have you dropped many of your activities and interests? It had a dichotomous answer: 0 “no”, 1 “yes.” Finally, we used a ques- tion from the Italian short version of the Scale of basic Activi- ties of Daily Living (ADLs) (Inzitari et al., 2006; Katz et al., 1963) to investigate the autonomy in taking a bath / shower (To go to toilet room, to use toilet, to arrange clothes, and to return without any assistance. This question has dichotomous answers: 1 “by oneself, no help”, 0 “with help”). All measures were col- lected by specially trained researchers. Strategy of Analysis We used the Wilcoxon test for dependent samples for ana- lyzing the presence of differences between pre- and post-testing in the sub-groups of men and women (see Table 1). To evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention, we calculated the width of a non-parametric effect size, which is more appropriate with very little samples than other kinds of measures (Valentine & Cooper, 2003). We also used the Mann-Whitney test for inde- pendent samples to analyze the presence of differences between men and women separately at each time (see Table 2). Finally , in all cases, we described our data using both median (which may be  E. RABAGLIETTI ET AL. 38 Table 1. Wilcoxon test for dependent sample s on p s ychological indicators of adjustment – differe nces between pre and post-test. Variable Z N Sig.1 Effect size Median Means (St. dev.) (ES) Pre-test Post-test Pre-test Post-test SF36-Perceiving health as limitation for moderate activity-men –1.890 7 0.06 0,51 3.00 2.00 2.57 (0.79) 1.86 (0.89) SF36- Perceiving health as limitation for moderate activity-wome n –1.134 10 0.66 0,20 2.0 2.50 2.30 (0.82) 2.40 (0.69) SF36-Fee lin g really down-men –1.633 7 0.10 0,44 3.00 2.00 3.00 (0.73) 1.86 (0.90) SF36- Fee ling really down-women –0.07 10 0.94 0,02 2.80 2.50 2.80 (1.23) 2.90 (1.66) GDS-Dropping activities and/or interest-men (1 = yes; 0 = no) –1.000 7 0.32 0,27 1 1 0.57 (0.53) 0.71 (0.49) GDS-Dropping activities and / or interest-women –2.000 10 0.05 0,45 0.50 0.0 0.50 (0.53) 0.10 (0.32) BADL-Taking a bath/shower auto- nomously-men (1 = yes; 0 = no) -0.0 00 7 0.99 0,00 1 1 0.71 (0.49) 0.71 (0.49) BADL-Taking a bath/shower auto- nomously-women –1.414 10 0.10 0,32 0.0 1 0.40 (0.52) 0.60 (0.52) 1 We considered significance till p < 0.10 because of the very little sample size. Table 2. Mann-whitney test for independent samples on psychological indicators of adjustm e nt – g ender differences at pre-test and post-test. Variable U N Sig.2 SF36-Perceiving health as limitation for moderate activity; pre-test 25.50 17 0.59 SF36-Perceiving health as limitation for moderate activity; post-test 15.00 17 0.08 SF36-Fee ling re a lly down; pre -te st 28.50 17 0.86 SF36-Fee ling re a lly down; pos t-te st 18.50 17 0.20 GDS-Dropping activities and/or interest; pre-te st 30.00 17 0.99 GDS-Dropping act ivities and/or interest; post-test 13.00 17 0.02 BADL-Taking a bath/shower autonomously; pre-test 17.00 17 0.10 BADL-Taking a bath/shower autonomously; post-test 23.00 17 0.35 2 We did not report in Table 2 the descriptive values (mean, median and standard deviation) because they are included in Table 1. 2 We considered significance ti ll p < 0 .10 because of the very lit tle sample size. more adequate than other descriptive measures in a very little sample) and mean as well as standard deviation. Results Men significantly decreased the perception that their health represents a limitation for moderate physical activity between the pre- and post-test (see Table 1). In addition, men who did not differ from women at the pre-test became more positive than their female counterparts at the post-test (see Table 2). Men also indicated a significant decrease in recent feelings of being down between the pre- and post-test (see Table 1). How- ever, men and women did not significantly differ at either the pre- or post-test in the variable (see Table 2). Women significantly decreased their perception of having dropped activity/interest between the pre- and post-test (see Table 1) and also showed a significant difference from men at the post-test (see Table 2). Furthermore, women significantly increased their autonomy in taking a bath/shower between pre- and post-test (see Table 1). In other words, women showed more similar results to men for this behavior at the post-test (at the pre-test men were more autonomous than women; (see Ta- ble 2). Finally, the effect size of the intervention in relation to statis- tically significant differences may be considered to be me- dium-large in general. Discussion and Conclusion The study aimed to describe the relationships between the participation in a program of physical activity, delivered by one specially trained instructor, among a group of elderly Italian people living in a residential care facility. In particular, the study sough to investigate any changes between the pre- and post-test as well as the gender differences for self-reported psychological aspects (i.e., feelings of depression, perception  E. RABAGLIETTI ET AL. 39 that one’s own health limits physical activities, and negative self-perception) and physical aspects (i.e., execution of activi- ties of daily living). The study identified three main sets of descriptive findings. First, we found that at the pre-test, some symptoms of depres- sion, negative self-evaluation, and lack of autonomy in abilities of daily living were similarly present in both genders. Men were slightly more likely than women to take a shower/bath independently at the pre-test. However, we do not know if the particular condition of psychological and physical frailty is the cause and/or the outcome of their living condition in a residen- tial care facility. In order to further clarify this point, we would need data before and after institutionalization. What we high- lighted with this finding is that - in the living conditions in a residential care facility and at a very old age - men and women seem much more similar than was expected based on previous studies among the independently living population (Angst et al., 2002), which tend to find a higher proportion of women in comparison to men showing symptoms of psychological dis- comfort, if not depressive symptoms. A second relevant issue is that the program of physical activ- ity had some powerful effects on the psychological and physi- cal condition of participants, mostly in terms of maintaining the pre-test condition rather than improving. These findings con- firm what we already concluded in previous studies (Ciairano, et al., 2010; Rabaglietti et al., 2010). To change th e self-perception of the elderly living in residential care facilities is very difficult. Our participants already suffered great many limitations to their autonomy. Furthermore, very old people - especially those who already show at least mild cognitive impairment - may find it difficult to cognitively detect and report on little changes in their psychological and physical conditions. Given the frailty of our participants, registering that they did not become worse over time may be considered a success of the intervention. However, we lack a comparable control group to be able to claim this phenomenon as a positive effect of the participation in the physical activity. Third, the specific kind of analyses we performed in the pre- sent study enabled us to move one step further from one our previous study (Rabaglietti et al., 2010), in which we found that depression was substantially stable between pre- and post-test periods. This finding seemed to contradict what other scholars have found. For instance, McMurdo and Rennie (McMurdo & Rennie, 1993), albeit with younger samples than our study, found a positive effect of physical activity on depression in older people. Going more in-depth by analyzing singularly different indicators of psychological discomfort, we found that - despite a similar initial condition - the participation in the physical activity might affect the well-being of the elderly dif- ferently in relation to gender. Men decreased both the percep- tion that their health is a limitation to their activity and the per- ception of feeling really down, becoming better adjusted than women at the post-test. Women decreased their dropping of interest and activity while also improving their skills to master independent living - an important ability of daily living (e.g., taking a bath/shower), becoming better adjusted than men at the post-test. We certainly need to investigate such differences further. However, at this stage of the research, we can interpret our findings by reflecting on the great differences in socialization processes that the present cohort of elderly experienced. To support our interpretation we can also refer to the study by Fortuijn et al. (2006), from the ESAW Study (2010). Accord- ingly to this study gender differences are more prominent in Italy than in others countries perhaps because of differential educational processes. We have to acknowledge that this popu- lation lived a completely different life as either a man or a woman. Given that the participants were approximately 85 years old, they were born around 1925, when all western socie- ties clearly segregated the tasks of men and women as well as the goals for them to accomplish. Usually men were responsible for the financial well-being of their families and they were not involved in any kind of daily care. In other words, they were almost completely dependent on their wives for the satisfaction of basic needs, such as chores and hygiene. Conversely women usually did not work outside the home, devoting their lives to the daily care of their husbands, children, and other relatives. This reflection may help explain something of the underlying processes of changes introduced by a program of physical ac- tivity. The intervention seems to affect what is more important for the two genders. The perception of being limited in an ac- tivity not directly involved in daily care (e.g., climbing stairs and carrying items) might be important for men whereas the skill of mastering independence in one of the few aspects of daily care allowed in residential care facility (i.e., taking a shower and/or bath) might be more important for women. Fur- thermore, the training seems to positively affect the fact that women become less likely to drop their interests and activities. This study has several limitations. Among the most impor- tant is the small sample size and lack of a equivalent control group. These limitations do not allow us to generalize our find- ings to different situations and populations. Furthermore, we failed to consider relevant and objective clinical parameters, such as blood pressure and other biochemical parameters. Despite these and other limitations, our findings are relevant as they suggest that even moderate physical training may con- tribute - at least in the short term (Bij, Laurant & Wensing, 2002) - to ameliorating the psychological discomfort of the elderly, who are at risk of developing serious injuries and gen- eral disabilities precisely due to their low levels of activity and high levels of discomfort (Heyward, 2004). Even a little ex- perience in movement may start changing processes. Ultimately, our findings suggest, such as highlighted also by Baltes and colleagues (Baltes et al., 1999) about the possibility of improv- ing well-being in old age, the need to look more carefully at gender differences in the underlying mechanisms leading eld- erly men and women to higher or lower levels of risk and to collocate the present condition in the whole life history. Acknowledgments The authors wants to acknowledge the contribution of Re- gione Piemonte, Direzione Sanità, Settore Igiene, and Sanità Pubblica to this study. References Anstey, K. J., von Sanden, C., Hons, B. S., Sargent-Cox, K., Hons, B. A., & Luszcz, M. A. (2007). Prevalence and risk factors for depres- sion in a longitudinal, population-based study including individuals  E. RABAGLIETTI ET AL. 40 in the community and residential care, American Journal Geriatric Psychiatry, 15, 6. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31802e21d8 Agüero-Torres, H., von Strauss, E., Viitanen, M., Winbland, B., & Fra- tiglioni, L. (2001). Institutionalization in the elderly: The role of chronic diseases and dementia. Cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiol o g y , 54, 795-801. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00371-1 A. I. P. [Associazione Italiana di Psicologia] (1997). Codice Etico della ricerca psicologica [Ethical code for psychological research]. Roma, IT: AIP. Available online at http://www.mopi.it/docs/cd/aipcode.pdf [Accessed August 6 2010]. Angst, J., Gamma, A., Gastpar, M., Lépine, J. P., Mendlewicz, J., & Tylee, A., (2002). Gender differences in depression. Epidemiological findings from the European DEPRES I and II studies. European Archives of Psychiatry and C l i n i c a l Neuroscience, 252, 201-209. doi:10.1007/s00406-002-0381-6 Apolone, G., & Moscone, P. (1998). The Italian SF-36 health survey translation, validation and norming. Journal of Clinical Epidemiol- ogy, 51, 1025-1036. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00094-8 Aromaa, A, & Koskinen, S. (2004) Health and Functional capacity in Finland: Baseline Results of the Health 2000 Health Examination Survey. Helsinki: Publica tion B12, National Public Health Institute. Baltes, M., Maas, I., Wilms, H. U., Borchelt, M., & Little, T. D. (1999). Everyday competence in old and very old age: Theoretical consid- erations and empirical findings. In P. B. Baltes, K. U. Mayer (Eds.), The Berlin Aging Study (pp. 384-402). Cambridge: Cambridge Uni- versity Press. Bird, M. J. & Parslow, R. A. (2002). Potential for community programs to prevent depression in older people. Medical Journal of Australia, 177, 107-110. Camacho, T. C., Roberts, R. E., Lazarus, N. B., Kaplan, G. A., & Cohen, R. D. (1991). Physical activity and depression: Evidence form the Alameda county study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 134, 220-231. Cesa-Bianchi, M. & Albanese, O. (Eds.). (2004). Crescere e invec- chiare. La prospettiva del ciclo di vita [Growing and aging: Yhe life-span course]. Rome: Unicopli Edizioni. Censi, A. (2004). Per un circolo virtuoso dell’autonomia degli anziani [“For a virtuous circle of older people autonomy”]. Animazione so- ciale, 2, 168-178. Ciairano, S., Liubicich, M. E., & Rabaglietti, E. (2010). The effects of a physical activity program on the psychological wellbeing of older people in a residential care facility: an experimental study. Ageing & Society, 30, 609-626. doi:10.1017/S0144686X09990614 Ciairano, S., Musella, G., Ge melli, M. E., Liubicich, F., Rabaglietti, M. E., & Roggero, E. A. (2006). Un intervento di promozione dell’atti- vità motoria e la salute fisica e psicologica degli anziani all’interno di una residenza: Valutazione di processo e di risultato [“An interven- tion of promotion of the motor activity and the physical and psycho- logical health of the elderly inside a residential care facility: trial and result assessment”]. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia dello Sport, 1, 3-11. Ciairano, S., Musella, G., Ge melli, M. E., Liubicich, F., Rabaglietti, M. E., & Roggero, E. A. (2006). Interventi di promozione dell’attività motoria per gli anziani e formazione degli istruttori: Punti di forza e criticità [Interventions of promotion of the motor activity for the eld- erly ones and training of the instructors: strength and waik points]. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia dello Sport, 1, 13-21. Cole, M. G., McCusker, J., Elie, M., Dendukuri, N., Latimer, E., & Belzile, E. (2006). Systematic detection and multidisciplinary care of depression in older medical inpatients: A randomized trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174, 38-44 . Costa, G., Migliardi, A., & Gnavi, R. (2006). Verso un profilo di salute [Towards a Profile of Health]. Città di Torino, Turin: Servizio Cen- trale Comunicazione. ESAW Study - European Study of Adult Well-Being. Available online at: http://esaw.bangor.ac.uk// [December August 6 2010]. Ell, K. (2006). Depression care for the elderly: Reducing barriers to evidence based practice. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 25, 115-148. doi:10.1300/J027v25n01_07 Farmer, M. E., Lo cke, B. Z., Moscicki, E. K., Dannenberg, A. L., Lar- son, D. B., & Radloff, L. S. (1988). Physical activity and depressive symptoms: The NHANES I Epidemiologic follow-up study. Ameri- can Journal of Epidemiology, 28 , 1340-1351. Folstein, M., Folstein, S., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal o f Psychiatric Research, 12, 189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 Fortuijn, J. D., Van der Meer, J. M., Van der Burholt, V. Ferring, D., Quattrini, S., Rahm Hallberg, I., Weber, G., & Wenger, G. C., (2006). The activity patterns of older adults: A cross-sectional study in six European countries. Population, Space and Place, 12, 353-369. doi:10.1002/psp.422 Fried, L. P., Ferrucci, L., Darer, J., Williamson, J. D., & Andreson, G. (2004). Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbid- ity: Implications for improved targeting and care. Journal of Geron- tology: Medical Science, 59, 255-263. Gill, T. M., Baker, D. I., Gottschalk, M., Peduzzi, P. N., Allore, H., & Van Ness, P. H. (2004). A prehabilitation program for the prevention of functional decline: Effect on higher-level physical function. Ar- chives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85, 1043-1049. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.10.021 Hendry, L. B., & Reid, M. (2000). Social relationship and health: The meaning of social “connectedness”, and how is related to health concerns for rural Scottish adolescents, Journal of Adolescence, 23, 705-719. doi:10.1006/jado.2000.0354 Heyward, V. H. (2004). Advanced Fitness assessment and Exercise Prescription. Champaign: Human Kinetics. Hirvensalo, M., Rantanen, T., & Heikkinen, E. (2000). Mobility diffi- culties and physical activity as predictor of mortality and loss of in- dependence in the community-living older population. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48, 493-498. Inzitari, M., Di Carlo, A., Baldereschi, M., Pracucci, G., Maggi, S., Gandolfo, C., Bonaiuto, S., Farchi, G., Scafato, E., Carbonin, P., & Inzitari, D. (2006). Risk and predictors of motor-performance decline in a normally functioning population-based sample of elderly sub- jects: The Italian longitudinal study on aging. Journal of the Ameri- can Geriatrics Society, 5 4, 318-324. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00584.x ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) (2006). Annuario statistico italiano 2006. [Statistical Italian Yearbook -2006]. Rome: ISTAT, Available online at: http://www.istat.it [Accessed 6 August 2010]. Katz, S., Ford, A. B., Mosko witz, R. W. , Jackso n, B. A., & Jaf fe, M. W. (1963). Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standard- ized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Journal of the American Medical Association, 185, 914-919. Kim, N. & Yang, S. (2001). Physical health status and depression of a community-dwelling elderly group. Journal of Korean Academic Nurses, 31, 1012-1020. Laukkanen, P., Leskinen, E., Kauppinen, M., Sakari-Rantala, R., & Heikkinen, E. (2000). Health and functional capacity as predictors of community dwelling among elderly people. Journal of Clinical Epi- demiology, 53, 257-265. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00178-X Malbut-Shennan, K., & Young, A. (1999). The physiology of physical performance and training in old age. Coronary Artery Diseases, 10, 37-42. doi:10.1097/00019501-199901000-00007 McMurdo, M. E. T. & Rennie, L. (1993). A controlled trial of exercise by residents of old people’s ho use . Age and Ageing, 22, 11-15. doi:10.1093/ageing/22.1.11 Pennix, B. W. J. H., Guralnik, J. M., Leveille, S., Ferrucci, L., & van Eijk, J. T. M. (1999). Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: Longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1346-1352. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1346 Pennix, B. W. J. H., Rejesk i, W. J., Panda, J., Miller, M . E. , Di Bari, M., Applegate, W. B., & Pahor, M. (2002). Exercise and depressive symptoms: A comparison of aerobic and resistance exercise affects on emotional a physical function in older persons with high and low  E. RABAGLIETTI ET AL. 41 depressive symptomatology. Journal of Gerontology, 57 B, 124-132. Pinquart, M. & Sorensen, S. (2001). Gender differences in self-concept and psychological well-being in old age: a meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 568, 195-213. Rabaglietti, E., Liubicich, M. E., & Ciairano, S. (2010). Physical and psychological condition of senior people in a residential care facility. The effects of an aerobic training. Health, 2, 773-780. doi:10.4236/health.2010.27117 Rockwood, K., Howlett, S. E., MacKnight, C., Beattie, B. L., Bergman, R., Hèbert, H., Hogan, D. B., Wolfson, C., & McDowell, I. (2001). Prevalence, attributes, and outcomes of fitness and frailty in commu- nity-dwelling older ad u l t s : R e p o rt from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 59A, 1310- 1317. Segulin, N. & Deponte, A. (2007). The evaluation of depression in the elderly: A modification of the geriatric depression scale (GDS). Ar- chives of Gerontology and Ger iatrics, 44, 10 5-112. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2006.04.002 Serby, M., & Yu, M. (2003). Overview: depression in the elderly. Mount Sinai Journal of Med ic i n e , 70, 38-44. Smith, J., & Baltes, P. B. (1999). Trends and profiles of psychological functioning in very old age. In P. B. Baltes, K. U. Mayer (Eds.), The Berlin Aging Study (pp. 197-226). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Soondool, C. (2008) Residential status and depression among Korean elderly people: A comparison between residents of nursing home and those based in the community. Health and Social Care in the Com- munity, 16, 370-377. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00747.x Steffens, D. C., Skoog, I., Norton, I., M. C., Hart, A. D., Tschanz, J. T., Plassman, B. L., Wyse, B. W., Welsh-Bohmer, K. A., & Breitner, J. C. S. (2000). Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: The cache country study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 601-607. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.601 Stenzelius, K., Westergreen, A., Thorneman, G., & Rahm Hallberg, I. (2005). Patterns of health complaints among people 75 + in relation to quality of life and need of help. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 40, 85-102. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2004.06.001 Stephens, T. (1988). Physical activity and mental health in the United States and Canada: Evidence form four populations surveys. Preven- tive Medicine, 17, 35-47. doi:10.1016/0091-7435(88)90070-9 Sullivan, D. H., Roberson, P. K., Smith, E. S., Price, J. A., & Bopp, M. M. (2007). Effects of muscle strength training and megestrol acetate on strength, muscle mass, and function in frail older people. Journal of American Geriatric Society, 55, 20-28. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01010.x United National Department of Economics and Social affairs, (2009). Word Population Agein 2009. United Nation. Valentine, J. C., Cooper, H. (2003). Effect size substantive interpreta- tion guidelines: Issues in the interpretation of effect sizes. Washing- ton, D.C.: What Works Clearinghouse. Van der Bij, A. K., Laurant, M. G. H., & Wensing, M. (2002). Effec- tiveness of physical activity interventions fo r older adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22, 120-133. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00413-5 Ware, J. E. Jr. & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36). Conceptual frame-work and item selec- tion. Medical Care, 30, 473-481. doi:10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002 WHO, (2002). Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. Ageing and Life Course. Genève: WHO. Yanagita, M., Willcox, B. J., Masaki, K. H., Chen, R., He, Q., Rodri- guez, B. L., Ueshima, H., & Curb, J. D. (2006). Disability and de- pression: Investigation a complex relation using physical perform- ance measures. American Journal of Ge r i a t r ic Psychiatry, 14, 12. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000224364.70515.12 Yesavage, J. A., Rose, T. L., Lum, O., Huang, V., Adey, M., & Leirer, V. O. (1983). Development and validation of geriatric depression screening: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17, 37-49. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4

|