Psychology 2011. Vol. 2, No. 1, 29-34 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.21005 Factors Influencing the Development of “Purpose in Life” and Its Relationship to Coping with Mental Stress Riichiro Ishida1, Masahiko Okada2 1Faculty of Medicine, Niigata University, Niigata, Japan; 2Division of Clinical Preventive Medicine, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Niigata University, Niigata, Japan. Email: ishida@med.niigata-u.ac.jp Received September 30th, 2010; revised December 22nd, 2010; accepted December 26th, 2010. Purpose: Factors influencing the development of purpose in life (PIL) were examined. Methods: We recruited 67 healthy students of Niigata University (34 males and 33 females, 18-35 years of age). PIL and approval mo- tivation (AM), and memories of experiences (IME) were measured using the PIL test, Martin-Larsen Approval Motivation Scale (MLAM), and the Early Life and Youth Experiences Inventory. Confusion, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and thumb-tip temperature were measured before and during “Evaluating-Integrating Words Task (EIWT).” Results: In the Profile of Mood States (POMS) tests, changes in the confusion scores were sig- nificantly higher in the weak PIL compared to the firm PIL group. The scores were significantly higher for the firm AM compared to the weak AM group. Changes in heart rate were significantly higher in the weak PIL compared to the firm PIL group. IME scores for memories of the beauty of nature, empathetic listening from parents and teachers were positively or negatively correlated with PIL test scores or MLAM scores for life stag- es: infancy, junior high school, and university. Conclusion: PIL and AM seemed to grow through the experi- ences of the beauty of nature and empathic understanding by parents and teachers during various developmental stages. Purpose in life had greater influence on emotional response and the autonomic nervous system response during psychologica l st ress compared to approval motivation Keywords: Purpose in Life, Approval Motivation, S tress, Confusion, Sympathetic Nervous Activity Introduction Every person has the “will” to seek meaning in life or to achieve purpose in life (PIL) that is a concept drawn from exis- tentialism (Frankl, 1972; Ishida, 2008). Every person is moti- vated to win the approval of others (Ishida, 2008). Recently it was reported that variations in the stress response, including emotional and sympathetic nervous system activity depends on one’s view of life (Ishida, 2008). Crumbaugh and Maholick (Crumbaugh & Maholic, 1964) developed the PIL test to assess the intensity of response related to personal meaning in one’s life, and Sato and Tanaka modified the test for use with a Japa- nese population (Sato & Tanaka, 1974). Larsen and Martin developed Martin-Larsen Approval Motivation Scale (MLAM) to assess the intensity of approval motivation (AM) (Ueda & Yoshimori, 1991), and Ueda and Yoshimori adapted it (Ueda & Yoshimori, 1991). Motivation can be classified as intrinsic and extrinsic (Bundra, 1977). The former relates to PIL (Frankl, 1972; Crumbaugh & Maholic, 1964; Sato & Tanaka, 1974), and the latter relates to the desire to get praise or to avoid pun- ishment by others, such as parents or school teachers. Extrinsic motivation relates to AM (Ishida, 2008). Persons with a firm PIL exhibit lower anxiety, less tension, and less acute sympa- thetic nervous system response un der stressful conditions such a s meeting unfamiliar persons (Ishida, 2008), or watching a kalei- doscopic roller coaster video (Ishida & Okada, 2006). A strong sense of PIL is widely recognized as an asset for coping with stress, but the underlining mechanism needs further clarification. Persons feel comfortable (less confused) when psychological events are readily integrated and mentally processed. Discom- fort (more confused) occurs when there is difficulty in intellec- tually and emotionally incorporating these events (Ueda & Yoshimori, 1991; Stanga et al., 2007). Feeling comfortable or uncomfortable leads to lesser or greater sympathetic nervous response, respectively (Ishida & Okada, 2006). Our previous study showed that persons with a firm PIL had an ability to integrate psychological events wit h less confusion (Ishida, 2008). Also, a firm PIL produced less sympathetic nervous system activity under stressful conditions. In contrast, persons with a strong need for appro val tended to have more anxiety and greater sympathetic nervous system activity during a mental arithmetic task than persons with less need for approval (Ishida, 2008). We hypothesized that PIL and AM during the various devel- opmental stages played an important role in the ability to cope with stressful psychological events. In the present study, we investigated the correlations between PIL and AM and factors influencing the development of PIL and AM. We used various experiences, such as being surrounded by beautiful natural scenery, or a scenario where parents or school teachers are providing active and empathetic listening. Self-report ques- tionnaires and autonomic nervous function tests were used to measure responses to these scenarios. Method Subjects We recruited 67 students (34 males and 33 females, 18-35  R. ISHIDA ET AL. 30 years of age) from a variety of departments from Niigata Uni- versity. Subjects were instructed not to drink any alcohol or tea and not to smoke on the day of the experiment. We did not give any instructions as for food intake. Each subject was tested separately. Three subjects were excluded because their behavior was affecting the autonomic nervous function tests. The sub- jects were assigned to firm PIL group (F-PIL group) or to weak PIL group (W-PIL group) based on test scores. Subjects were also assigned to a firm approval motivation group (F-AM group) or a weak approval motivation group (W-AM group). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medi- cine of Niigata University (No. 562) and written informed con- sent was obtained from all subjects. Measuring PIL and AM The PIL test was used to measure the intensity of PIL and consisted of 20 questions, such as, “I have definite goals and aims,” “My life is filled with exciting and good things,” and “I would feel my life was worthwhile even if I died today”. The subjects responded using a 7-point scale (1: not at all, through 7: very strongly). The total scores were standardized to 50, and standard deviation (SD) to 10. Higher scores indicated a strong- er sense of PIL. MLAM was used to measure the intensity of AM and consisted of 20 items such as “conforming to the ex- pectations of others,” “never begging a person’s pardon,” and “acceptance of punishment by others”. The subjects responded using a 5-point scale (1: not at all, through 5: very strongly). MLAM scores ranged from 20 to 100 points. Higher scores indicated a st ronger AM. Evaluatin g the Intensity of Memories of Experiences (IME) We used the Early Life and Youth Experiences Inventory (EYEI), which is a newer version of the Early Life, Youth, and Adulthood Experiences Inventory (EYAEI) (Ishida, 2008). In this test, the subjects were asked: “Do you remember having feelings that were associated with the beauty of nature?” “Do you remember if your parents listened to you with empathy and support?” and “Do you remember if your teachers listened to you with empathy and support?” These questions were sepa- rately directed towards times of infancy ( < 6 years of age), elementary school (6-11 years of age), junior high school (12-14 years of age), senior high school (15-17 years of age), and university (18 years of age to the present). The subjects answered using a 7-point scale (1: not at all, through 7: very strongly). Experimental Stress Using “Evaluating-Integrating Words Ta sk (EIWT)” We prepared a 30 cm × 50 cm sheet printed with six open circles; “My purpose in life” was written in the center circle (Figure 1). Twenty chips (3 cm in diameter) were labeled with words relating to psychological events. These words were ob- tained from random samples of “Word Association Norms” (Umemoto, 1969). In order to avoid biased responses, two sets of 20 words were prepared, and then one set was randomly assigned to each subject. After completion of the psychological tests, subjects performed a four-minute task in the presence of Figure 1. An example of Evaluating-Integrating Words Task (EIWT), using a set of 20 words. The alternative set included 20 different words: school, long, question, black, swim, escape, back, friendship, want, shout, abandonment, wages, eruption, crow, debt, cause, plan, publicity, rea- son, and popularity. the experimenter (male, 59 years of age). The experimenter said, “You should place the 20 words within six open circles in four minutes. If the word more accurately describes your purpose in life, you should place it closer to the center of the circle. Place words of similar value at the same distance from the center. After the task, you should explain your arrangement of the words. Any talking during the experiment is prohibited.” We originally developed this protocol: “Evaluating-Integrating Words Task (EIWT)”. Autonomic Nervous Function Tests The parameters of the autonomic nervous activity were heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and thumb-tip tem- perature (TTT). These were measured before and during EIWT, after sitting comfortably in a chair for 20 minutes (Munir et al., 1996). HR and SBP were recorded with an electric sphygmo- manometer (ES-P100 0, TERUMO-Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Jpan), and TTT was measured with a skin thermometer (D717, TECH- NOL7-Co., Ltd.). Room temperature was set at 23.99 ± 1.27℃, humidity at 54.90 ± 2.15%, illumination at 757.76 ± 60.70 lx, and noise level at 39.96 ± 0.27 dB. Atmospheric pressure (1017.81 ± 5.97 hPa) was measured at the time of the experi- ment. The data were expressed as mean ± SD. Measuring Mood In order to measure mood, we used the Profile of Mood States (POMS) which is a self-report test developed by McNair et al. (Aroian et al., 2007) and revised by Yokoyama (Yoko- yama, 2006). The test included questions about six moods:  R. ISHIDA ET AL. 31 confusion, tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, fatigue, an- ger-hostility, and vigor. Confusion, for example, included five elements: “confused”, “unable to concentrate”, “bewildered”, “efficient”, and “forgetful.” Responses were set on a 5-point scale (1: not at all, through 5: very strongly). Mean and SD of scores for each subscale were 50 and 10 points, respectively. Higher scores indicated more confusion (Yokoyama, 2006). Statistical Analyses Chi-square test was used for evaluating differences in gender between the F-PIL and W-PIL groups and the F-AM and W-AM groups. An unpaired 2-tailed t test was used for evalu- ating differences in age, PIL test scores, MLAM test scores, and environmental conditions between the two groups. A paired 2-tailed t test was used for evaluating the changes in scores of POMS and each of the three autonomic indicators before and during EIWT. The odds ratios (OR) of IME scores (strong memory: 5 points, and weak memory: 4 points), gender, and age were obtained to predict PIL and AM. ANCOVA was done for evaluating change of scores in the POMS test. AN- COVA was also done for PIL, MLAM scores, and gender. ANOVAs were performed for evaluating change in heart rate (CH-HR), change in systolic blood pressure (CH-SBP), change in thumb-tip temperature (CH-TTT), PIL, MLAM score, gender, and age. Pearson’s correlation analyses and partial correlation analyses were done for correlations between PIL test scores and MLAM scores and between CH-CS and CH-HR, CH-SBP, and CH-TTT. Statistical significance was accepted at the p < 0.05 level. Bonferroni correction was also applied. SPSS software (SPSS Japan Inc, Tokyo, Japan) was used for the statistical analyses. Figure 2. Correlations between purpose in life test scores and Martin-Larsen Approval Motivation Scale (MLAM) scores. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is -0.305 (p < 0.05) and partial correlation coefficient con- trolling for gender and age is -0.270(p < 0.05). Line indicates regres- sion. IME Scores IME scores of remembering feelings associated with the beauty of nature during infancy, junior high school, and univer- sity were positively correlated with PIL test scores; however IME scores were negatively correlated with MLAM scores for the university age time period (Table 2). IME scores for memo- ries of empathetic listening from parents during the university period were positively correlated with PIL test scores. The IME scores of elementary school age were negatively correlated with PIL test scores. The IME scores of elementary school age were positively correlated with MLAM scores. IME scores for em- pathetic listening by teachers during the junior high school age were positively correlated with PIL test scores. The IME scores in senior high school age were positively correlated with MLAM scores. The IME scores during infancy were negatively correlated with MLAM scores. Age was positively correlated with PIL test scores. Results Basic Characteristics The F-PIL group was significantly older than the W-PIL group (Table 1). MLAM scores were significantly higher for the W-PIL group compared to the F-PIL group. Significant negative correlations were observed between PIL test scores and MLAM scores using Pearson’s coefficients and also by partial correlation coefficients (Figure 2). Parameters of the Autonomic Nervous System After Bonferroni corrections, POMS scores showed significant Table 1. Demographic and psychological characteristics of firm purpose in life (F-PIL) and weak purpose in life (W-PIL) groups and firm approval motiva- tion (F-AM) and weak approval motivation (W-AM) groups. PIL AM Parameters F-PIL group (n = 36) W-PIL group (n = 31) p F-AM group (n = 34) W-AM group (n = 33) p Demographic parameters Subjects (male/female): n (17/19) (17/14) 0.627 (16/18) (18/15) 0.628 Age, y 21.50 ± 2.89 20.19 ± 1.35 * 20.50 ± 1.58 21. 30 ± 2.97 0. 171 Psychological parameters PIL test scores (points) 59.78 ± 4.22 45.23 ± 6.86 *** 51.94 ± 9.72 54.18 ± 8.59 0.32 2 MLAM sco res (points) 60.58 ± 7.48 65.55 ± 7.19 ** 68.88 ± 4.93 56.70 ± 4.44 *** n: number of subjects, PIL: purp ose in li fe, MLAM: Martin-Lar sen App roval Motivation Scale, AM: approval motivation. Data are mean ± standard deviation (SD). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.  R. ISHIDA ET AL. 32 Table 2. Correlations of purpose in life test (PIL) scores and Martin-Larsen Approval Motivation Scale (MLAM) scores, and intensity of memories of experi- ences (IME) score for five developmental sta ges and demographic characteristics: Logistic re g r e s s i o n a nalysis (N = 67). PIL AM Memories of the beauty of nature Empathetic listening by parents Empathetic listening by teachers Memories of the beauty of nature Empathetic listening by parents Empathetic listening by teachers Parameters Coef p Coef p Coef p Coef p Coef p Coef p IME scores Infancy 3.97 * 0.86 0.5832.46 0.073–0.64 0.692 –0.52 0.705 –4.48 ** Elementary school –2.35 0.059 –3.78 * –1.22 0.316–0.71 0.578 4.51 * 1.71 0.198 Junior high school 2.62 * 0.69 0.5033.28 * –1.71 0.134 –0.96 0.386 1.28 0.218 Senior high school –1.66 0.223 1.36 0.2560.15 0.894–0.27 0.853 0.35 0.778 4.75 ** University 4.66 ** 2.62 * –0.60 0.640–2.45 * –2.44 0.072 –1.99 0.096 Gender –1.68 0.148 –0.56 0.549 Age 0.76 * 0.08 0.662 Constant –22.45 * 0.61 0.862 Odds ratio Odds ratio Odds ratio Odds ratio Odds ratio Odds ratio IME scores Infancy 52.79 2.37 11.74 0.53 0.60 0.01 Elementary school 0.10 0.02 0.30 0.49 90.93 5.50 Junior high school 13.69 1.99 26.56 0.18 0.38 3.60 Senior high school 0.19 3.89 1.16 0.77 1.42 115.49 University 106.03 13.74 0.55 0.09 0.09 0.14 Gender 0.19 0.57 Age 2.14 1.08 AM: approval motivation. In the logistic regression analyses, ‘1’ and ‘0’ were assigned to the F-PIL and W-PIL groups, F-AM and W-AM groups were the dependent variables, IME scores ( strong memory: 5 points, and weak memory: 4 points) were the independent variables: memories of the beauty of nature, empathetic listening by parents a nd teachers, and male and female. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. increase in confusion before and during EIWT; HR and SBP were significantly increased, and TTT was significantly de- creased before and during EIWT. In POMS test, changes in confusion (CH-CS) were significantly higher for the W-PIL compared to the F-PIL group. The scores were significantly higher for F-AM compared to the W-AM group (Table 3). CH-HR was significantly higher for W-PIL compared to the F-PIL group after Bonferroni correction. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r = 0.309) and partial correlation coefficients (r = 0.333) between CH-CS and CH-SBP were significant after Bonferroni corr e ction. Discussion We developed EIWT as a psychological test to assess the ability to cope with stressful psychological events. We found that confusion and autonomic nervous responses such as HR, SBP, and TTT changed significantly during the test. The results showed that the test itself might be a source of emotional stress for the subjects. We found that the intensity of PIL was in- versely correlated with AM. Persons with a firm PIL showed fewer changes in the scores that reflected less confusion during EIWT. Whereas, persons with a firm AM showed much larger changes in scores that reflected confusion compared to those with a firm PIL. It can be concluded that PIL and AM grown and developed through the stages of infancy, elementary school, junior high school, senior high school and university. A firm purpose in life including weak approval motivation can be controlled with conscious regulation, while autonomic nervous functions can not (Ishida & Okada, 2006). Strong memories of the beauty of nature during infancy, junior high school, and university, in fact, facilitated the growth of intrinsic motivation and a firm PIL (Table 2). Strong memories of such experiences during the university period decreased extrinsic motivation and AM. Strong memories of empathic understand- ing from parents during the university age facilitated the  R. ISHIDA ET AL. 33 Table 3. Change in scores reflecting confusion (CH-CS) and cardiovascular measures for F-PIL and W-PIL groups and for F-AM and W -A M groups: Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for CH-CS and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for change in heart rate (CH-HR), systolic blood pressure (CH-SBP), and thumb-tip temperature (CH-TTT). PIL AM Parameters F-PIL group (n = 36) W-PIL group (n = 31) p F-AM group (n = 34) W-AM gro u p (n = 33) p CH-CS (point s) 5.92 ± 11.84 12.19 ± 12.07 * 9.97 ± 14.60 7.64 ± 9.36 * CH-HR (beats/min) 8.78 ± 6.09 12.00 ± 7.19 + 10.32 ± 6.34 10.21 ± 7.27 0.610 CH-SBP (mmHg) 4.89 ± 7.30 5 .10 ± 7.09 0.367 4.35 ± 7. 56 5.64 ± 6.76 0.580 CH-TTT (℃) 1.00 ± 0.91 1 .07 ± 0.97 0.420 1.09 ± 0.92 0.97 ± 0.96 0.503 PIL: purpose in life; AM: approval motiva tion; F-PIL: fi rm purpose in life; W-PIL : weak purp ose in li fe; F-A M: firm approval m otivation; W- AM: weak approval motiva- tion. *p < 0.05, +p < 0 .05 / 3 = 0. 0 16 after Bonferroni c orrection. development of firm PIL. Furthermore, the strong memories of empathic understanding from teachers in junior high school age facilitated firm PIL. Strong memories of empathic understand- ing from teachers during infancy decreased AM. Shirasa re- ported that children showed rapid mental and physical devel- opment during infancy, rejected their parents, and rejected or showed respect for teachers during junior high school age. Adolescents also worried about and were willing to establish PIL during university age (Shirasa, 1981). Existing data indi- cated that personality was affected by traits that were estab- lished during each developmental stage (Shirasa, 1981; Allen, 2000). The present data supports these studies. Surprisingly, strong memories of empathic understanding by parents during elementary school age decreased PIL; whereas strong memories of empathic understanding from teachers during senior high school age increased AM. A previous study showed that con- formation to others’ expectation decreased intrinsic motivation and increased extrinsic motivation (Ishida, 2008; Bundra, 1977). Children imitate parental lifestyle without any criticisms during elementary school age (Shirasa, 1981), and will willingly dem- onstrate behaviors, such as preparing to enter into a “good uni- versity” and seeking out “good company” (Shirasa, 1981). This may support the decrease of PIL. Regarding PIL, the changes in both CH-CS and CH-HR were lower in the F-PIL group than the W-PIL group. CH-CS was positively correlated with CH-HR. Regarding AM, changes in CH-CS were greater in the F-AM group than in the W-AM group. CH-CS was not significantly correlated with CH-HR, but was positively correlated with CH-SBP. These findings suggest that PIL influences emotion and the autonomic nervous system more strongly than AM. It is apparent that strong mem- ories during the various developmental stages play an important role in the ability to cope with stressful psychological events (Shirasa, 1981; Allen, 2000). There are some limitations in this study. The subjects were students. Future studies should include various age groups and occupations. Since elementary school spans 6 years, data col- lection was arbitrarily divided into a lower age and a highe r age (Shirasa, 1981). The experiments were performed using the hypothesis that EIWT reflected “evaluation and integration of psychological events.”; however, we did not define this concept. Experimenter bias might also be a factor. Conclusion Purpose in life had a greater influence than approval motiva- tion on emotional response and autonomic nervous system function during psychological stress. Purpose in life and moti- vation based on the need for approval seem to grow through experiences such as the exposure to the beauty of nature and supportive and empathic understanding from parents and teachers during various developmental stages. Acknowledgement This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Science Re- search from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 19927018; 2007). The authors wish to express their grati- tude to Yuko Ishida for the data analysis. References Al-Ani, M., Munir, S. M., White, M., Townend, J., & Coote, J. H. (1996). Changes in R-R variability before and after endurance train- ing measured by power spectral analysis and by the effect of isomet- ric contraction. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 74, 397- 403. Allen, B. P. (2000). Personality Theories (3rd Edition). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Aroian, K. J., Kulwick i, A., Kaskiri, E. A., Te mplin, T. N., & Wells, C. L. (2007). Psychometric evaluation of the Arabic language version of the Profile of Mood States. Research in Nursing & Health, 30, 531-541. doi:10.1002/nur.20211 Bundra, A. (1977). Social learning theory: Upper saddle river. N. J: Pren- tice Hall. Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholic, L. T. (1964). An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal o f C l in i c al Psychology, 20, 200-207. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(196404)20:2<200::AID-JCLP2270200203> 3.0.CO;2-U Frankl, V. E. (1972). The meaning of meaninglessness: A challenge to psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychoanalys is, 32, 85-89. doi:10.1007/BF01872487  R. ISHIDA ET AL. 34 Ishida, R. (2008). Correlations between purpose in life (ikigai) and state anxiety in schizoid temperament with considerations of early life, youth, and adulthood experiences. Acta Medica et Biologica, 56, 27-32. Ishida, R. (2008). Correlation between social desirability and auto- nomic nervous function under goal-oriented stress (mental arithmetic) with consideration of parental attitude. Autonomic Nervous System, 45, 242-249. Ishida, R., & Okada, M. (2006). Effects of a firm purpose in life on anxiety and sympathetic nervous activity caused by emotional stress: Assessment by psycho-physiolo gica l method. Stress Health, 22, 275- 281. Sato, F., & Tanaka, H. (1974). An experimental study on the existential aspect of life: Part Ⅰ. Tohoku Psychologica Folia, 33, 20- 46. Shirasa, T. (1981). Textbook of developmental psychology. Tokyo: Kawashima-Shoten. Stanga, Z., Field, J., Iff, S., Stucki, A., Lobo, D. N., & Allison, S. P. (2007). The effect of nutritional management on the mood of mal- nourished patients. Clinical Nutrition, 26, 379-382. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2007.01.010 Ueda, S., & Yoshimori, M. (1991). An attempt to make the Japanese version of the Martin-Larsen Approval Motivation Scale. Annual report of studies of Department of Education, Hiroshima university, 39, 151-156. (in Japanese) Umemoto, T. (1969). Word asociation norms. Tokyo: Tokyo university press. (in Japanese) Yokoyama, K. (2006). POMS short form. To kyo: Kaneko-Shobo.

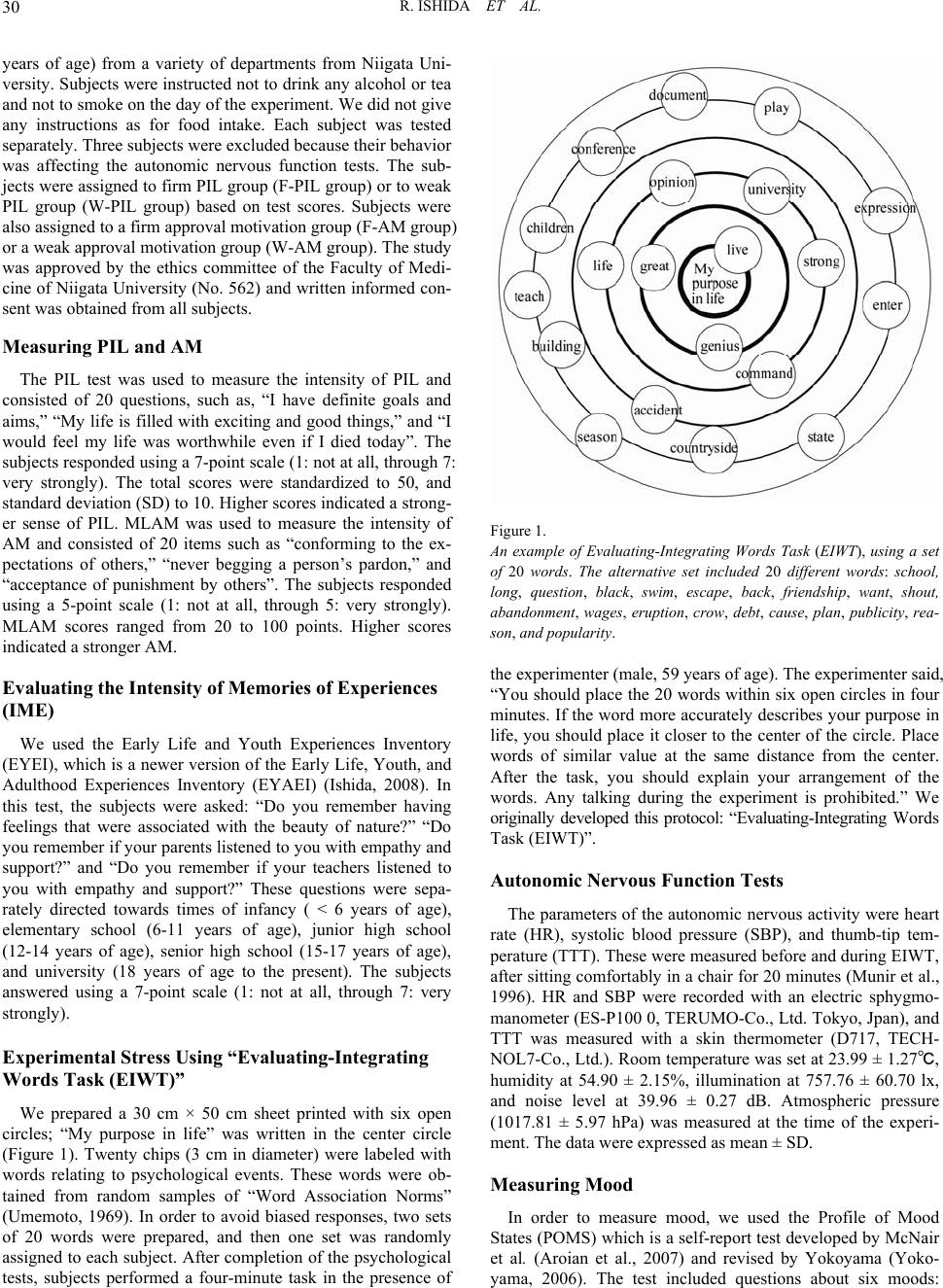

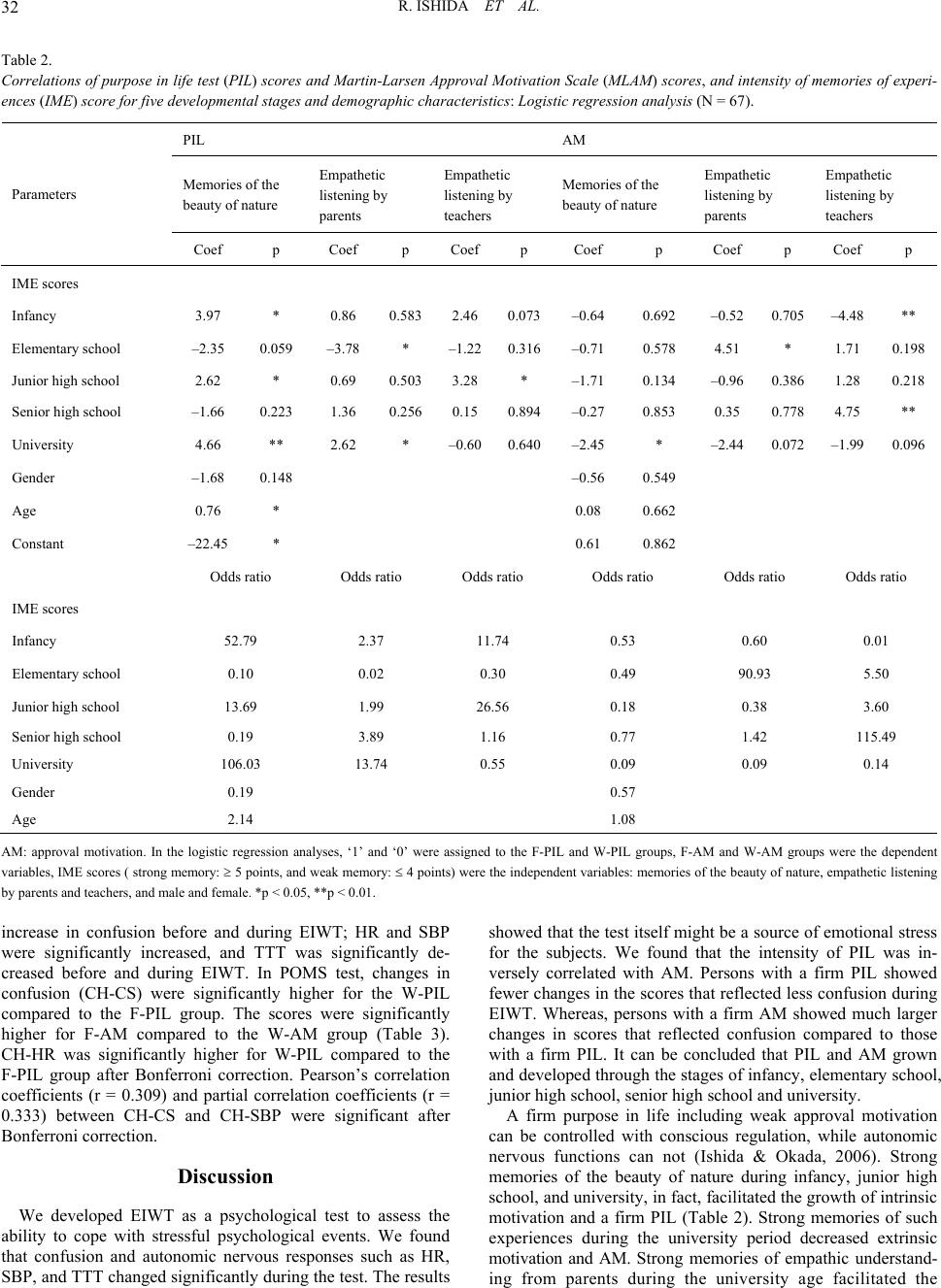

|