iBusiness, 2013, 5, 175-181 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ib.2013.53B037 Published Online September 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ib) Copyright © 2013 SciRes. IB FDI in Services and Manufacturing Efficiencies in Host Countrie s: Evidence from China* Libin Luo Beijing international Studies University. Received 2013 ABSTRACT The paper studies the correlations between FDI in services and manufacturing efficiencies in host countries. First a theoretical analysis is presented on the direct and indirect channels through which FDI in services enhances manufac- turing efficiencies in host countries. Then the forward linkages and backward linkages between FDI in services and manufacturing sector in host countries are tested empirically using China’s industrial panel data. We find that FDI in services has positive forward and backward linkage effects on China’s manufacturing sector, with forward linkages stronger than backward linkages, and the wholesale, retail, trade and restaurant sector has the strongest linkage effects. Keywords: FDI i n S ervic es; Manufacturing Efficiencies in Host Countries; Inter-industry Technical Spillover 1. Introduction and Literature Review This paper focuses on the correlations between FDI in services and efficiencies of manufacturing sectors in China. The issue is introduced mainly based on the fol- lowing thr ee phenomena: First, FDI in service sectors has been growing rapidly during the past few decades. Since 1990s, FDI in service sectors began to cover an increasing proportion of the total FDI, replacing manufacturing and became the most important sectors utilizing FDI. From 1990 to 2007, the share of global FDI stock in services was up from 48.61% to 63.84%. China witnessed the same trend in recent years. From 1997 to 2008, real FDI utilization in service sectors expanded by 214%; Its pr oportion in total FDI increased from 26.65% to 41.07%. Second, China’s manufacturing sector needs to im- prove its output efficiencies to stay competitive. Great changes occurred to China’s manufacturing sectors de- velopment environment. First of all, labor costs keep climbing up. From 2003 to 2008, average annual wages of Chinese manufacturing workers almost doubled, making it one of the fastest growing in the world. With the growth in Chinese economy and Chinese national income, labor costs will continue to increase. Second, natural resource constraint is intensified. Energy con- sumption has been higher than the production capacity. From 2001 to 2008, the gap between production and consumption increased from 57.54 million to 250 million tons of standard coal. In 2006, GDP per kilogram of oil in China is 3.2 dollars, below the world average of $5.2. Third, the appreciation of RMB will dampen the compe- tiveness of Chinese goods in international market. Chi- na's manufacturing industry can no longer rely solely on cheap l ab o r and int ensi ve ene r g y i nput , p r o duc ti vit y mu st be improved. Third, service sector is an important source of manu- facturing efficiency enhancement. Some producer service inputs, such as research and development, management consulting, mergers and acquisitions, legal services, are just like fixed assets in that their cost and revenues need to be shared for a long time, and they can improve pro- ductive technology and managerial skills of manufactur- ing enterprises; other producer services like product de- signing and marketing and other producer services and create product differentiation, giving enterprises their competitive advantages. In addition, producer services also help to achieve internal and external economies of scale. In recent years, more and more manufacturing companies contract producer services out, resulting in rapid growth of service outsourcing. Outsourcing brings cost savings and higher qualities. Through outsourcing, manufacturing companies can enhance their core compe- titiveness, respond to demand uncertainty. Service out- sourcing brings better division of labor, striking up the importance of service sector for manufacturing efficien- cies. The importance of producer services and development * This work is supported by a grant from visiting scholar program of Beij ing Municipa l Commis si on of Educat ion (No. 11530500015 ).  FDI in Services and Manufacturing Efficiencies in Host Countries: Evidence from China Copyright © 2013 SciRes. IB of service outsourcing have resulted in manufacturing sectors greater dependence on service input. Dependence rate of manufacturing sectors on service input in 9 OECD countries has been rising from 16% in 1970s to 27% in early 21 century (S. Li, C. Gao, 2008). While the calcu- lation based on input-output table of China, China's manufacturing industry's dependence on the service in- dustr y in d ecli ne, but i n the lo ng run, as Chi na's e conom- ic growth, China's dependence on manufacturing to the service sector will gradually increase. Most parts of FDI in services provide producer servic- es. For example, in 2007, 86.14% of world total stock of FDI in services was in areas like finance, trade, business services, transport, storage and communications sector. From 2004 to 2008, 75.8% of the service FDI utilized by China are in real estate, renting and business services, financial services and the postal industry, transportation, storage. On the one hand, FDI in producer service sectors can directly affect manufacturing efficiencies in the host country; on the other hand, FDI can promote host coun- try's service industry, thus indirectly affecting the manu- facturing efficiencies in the host co unt ry. Theoretical studies on the correlations between ser- vices sector liberalization and efficiencies of manufac- turing industry first appeared in 1980s. Markusen (1989) introduces producer services into the DS production function as intermediate inputs, finding that producer services liberalization can lead to large gains. Markusen et.al. (1990) established a model of producer services, further analyzing the economic benefits of services libe- ralization to the host country. Francois (1990) finds pro- ducer services t obtained by foreign trade or multination- al corporations promote specialization in developing countries, playing important roles in achieving domestic economies of scale. Compared with the theoretical research, very little em- pirical research in related fields can be found in the lite- rature. The earliest empirical literature is Jensen et.al. (2004), which studies the case of Russia's accession to the World Trade Organization, finding that elimination of barriers to FDI in business services enhances factor producti vit y in s ec to rs tha t us e b usiness se r vi ce as i np ut s. With Czech enterprise data from 1998 to 2003, Arnold et al. (20 06) finds that the overa ll liberalization of services, the presence of foreign service providers, and privatiza- tion of services all have a significant positive correla- tionwith the efficiency of the domestic downstream in- dustries, and liberalization of foreign investment in the service industry is the most substantial contributor among the three. Fernandes, Ana M. and Paunov, Caro- line (2008) employ Chile enterprise data between 1992- 2004 and finds substantial positive correlations between FDI in services and labor productivities of downstream manufacturing sectors. Jiang Xiaojuan (2008) finds the presence of foreign designing enterprises promotes man- ufac t uring ente rpr ises co mpetitiveness. Considering the fast growth of FDI in services and importance of manufacturing sector in China, we need further research on the mechanisms and relationship be- tween FDI in service sector and manufacturing efficien- cies in host countries, to help fully understand the role and significance of services FDI, and to help explore effective channels to expedite the transformation and upgrading of C hina's manufacturing indus try. The rest of thi s pap er is organized as follows: Part two analyzes the direct and indirect effects of FDI in services on manufacturing efficiencies in host countries. Part three tests the correlations between FDI in services and manufacturing efficiencies in China with China's indus- try panel data, with focus on the forward and backward linkage effects. Part four is conclusions. 2. Influence of FDI in Services on Manufacturing Efficiencies FDI in services influence manufacturing efficiencies in host countries through two channels. In the direct chan- nel, the output of foreign service enterprises is direct input into manufacturing sectors in host countries; while in the indirect channel, the presence of FDI in service local service sector, which in turn benefit manufacturing efficiencies. 2.1. Direct Channels 1. Forward-linkage technology spillover. Since most FDI in services exist in the producer service sectors, they provide producer services to related manufacturing in- dustries. Compared with local service enterprises, TNCs with better technologies and human resources (Fernandez, 2001; Griffith et.al., 2004; Lombard, 1990; Karparty and Poldahl, 2006) may provide better services, which can better help improve efficiencies of manufacturing enter- prises in host countries. Amiti and Konings (2005) find substantial positive correlation between liberalization of trade in intermediate inputs and downstream manufac- turing productivities. Some case studies (Arnold et al, 2006; Fermandes and Caroline, 2008) also find substan- tial positi ve correlations between FDI in services and the growth of manu fact uring l abo r pr oductivities. 2. Backward-linkage technology spillovers. Take wholesaling and retailing industry as an example. Gereffi (1994) categorizes global production chains into two types, producer-driven and buyer-driven. The latter is driven by large retailers, which engage in designing and marketing, and outsource production process to manu- facturing suppliers. Large multinational retailers often require their suppliers to reduce costs and improve qual- ity. Moreover, because multinational retailers usually  FDI in Services and Manufacturing Efficiencies in Host Countries: Evidence from China Copyright © 2013 SciRes. IB have better distribution efficiencies, suppliers in manu- facturing sectors compete to enter, which gives manu- facturers incentives of improving quality and reducing costs. 3. St rengt hened te chnology spillover effect. Compared to FDI in manufacturing sectors, FDI in services have stronger technology spillover effects, because the spil- lover effect FDI in services has on manufacturing indus- tries is inter-industry, while in manufacturing FDI cases, there could be either inter-industry or intra-industry. Theoretical and empirical finds that inter-industry tech- nology spillover is e asier to occur1. Soft technology transfers brought by manufacturing multinationals are mainly organization-wide, therefore the producer services that produce soft technologies will only support the manufacturing process for local branches of multinationals, instead of being transferred by trade or licensing (Markusen, 1995). Local manufac- turing enterprises can onl y obtain soft technologies fro m manufacturing TNCs through non-market activities such as cooperative effect, competition effect and demonstra- tion effect and so on. FDI in service sectors, especially FDI in producer ser- vices are the manifestation of producer service ``externalization'' in globalized world, which expand specialization and division of labor to host countries. Market-seeking FDI in the services target local enter- prises in host co untries as clients fro m the very beginning ; those who fo llo w their exi sti ng cl ients into host cou ntries will finally extend their client base to local manufactur- ing companies. For example, at present, over 70% of revenues of the majority of foreign management con- sulti ng fi rms i n Chi na c ome fr om local custo mers. In this sense, services FDI has stronger technology spillover effects on local manufacturing enterprises in host coun- tries. 4. FDI in services has interactions with that in manu- facturing sectors. First of all, some FDI in services are from manufacturing multinational companies, providing support to their business in host countries, especially in trade and finance. Second, client-following FDI can en- hance operational efficiencies of foreign manufacturing companies in host countries. Moreover, the existence of services FDI provide sound infrastructure for manufac- turing companies; and with overseas business matures, service MNCs also encourage their customers in home countries to expand their business in host countries (Da- niel, 1993). Case studies on Japan finds in late 1980s and early 1990s, the presence of Japanese MNCs in service sectors brought new Japanese multinationals in manu- facturing sectors. The study proposes two reasons: tech- nological advances make services a more important input in manufacturing sectors; relative to large-scale manu- facturing enterprises, smaller manufacturing enterprises rely more o n existing service provider networks, and the presence of Japanese service multinationals reduced overseas investment cost. Chyau T uan and Linda FY Ng (2003) make a case study on Guangdong Province in China , which finds substan tial corre lations between loca- tion choices of manufacturing and service FDI, especial- ly between small and medium foreign manufacturing enterprises and FDI in services, and its large-scale ser- vice enterprises with FDI location choice of the highest correlation. 5. Helping upgrade the structure of exportation. Since many services are not internationally tradable, it is gen- erally believed that FDI in services has minor influences on the exports of the host country. (UNCTAD, 2006). However, many producer services can provide critical input to manufacturing sectors in host countries, thus changing the comparative advantages of manufactured goods and improving their export competitiveness (Mar- kusen et. Al., 2005). Francois and Woerz (2007) find that services make the largest contributions to exportation of goods. Producer service liberalization is significantly positively correlated with exportation competitiveness of service- and technology-intensive products, but has a significant negative correlation with exportation perfor- mance of non-service-intensive products. Wolfmayr.Y. (2008) tests the correlations between service linkage and market share of the exported manufactured goods, and finds international service linkage has the significant positive effects on high-tech. products exportation. 2.2. Indirect Channels 1. Encouraging local service providers to improve ser- vice quality. Blind and Jungmittag (2004) found that FDI and imports of services have significant positive effects on the service product and process innovation. Some case studies also proved the effect of international service on local service innovation. For example, during the priva- tization of communications industries in Argentina in 1980s, the introduction of foreign equity participation have a very big effect on the improvement of communi- cation infrastructure and the quantity and quality of ser- vices. Within two years of the reform, the two major communications companies, Telefonica and Telecom, increased 330,000 and 270,000 lines respectively, while in the five years prior to the reform, Telecom, originally known as ENTel only increased 98,000 lines; In addition, the companies also update their technologies to digital systems (Bernard Hoe kman et a l., 1997). 2. Bringing more service varieties. Services are more 1For a literature review about inter-industry and intra-industry tech- nology spillover, see Jing Peng, Co- development of MNCs and Local Enterprises: From Backward Linkage to Horizontal Linkage. CASS Dissertation, 2 00 5.  FDI in Services and Manufacturing Efficiencies in Host Countries: Evidence from China Copyright © 2013 SciRes. IB differentiated than manufactured goods. Therefore, ser- vices by multinational providers are more of comple- mentary than substitution with local service providers. Case study about FDI liberalization in services in Russia find s tha t , FDI in services brings a net increase of service varieties, though competition forced some local service providers to exit the market2. Other case studies about Turky, Hungary, Mexico, and Chili also provide such evidences (Denizer, 1999; McBride, 2004; Cardenas et al., 2003; ECLAC, 2000). More service varieties help generate Dixit-Stiglitz-Either effect, raising the down- stream manufacturing enterprises total factor productivity (Dixit, A. and J . Stiglitz, 1977; Either, WJ , 19 82). 3. Pushing the service price down. The reasons are twofold. First, FDI intensifies competition, forcing ser- vice companies to reduce costs. Sometimes the presence of multinational corporations breaks the monopoly mar- ket structure. T he original monopol y is no longer able to obtain monopoly rents (Fernandes, Ana M.and Paunov, Caroline, 2008) Classen et.al. (2001) finds that between 1988 and1995, introductions of foreign banks intensified the competition in the local banking sector, and profit rates were lowered. Second, for the transnational service corporations, expanding into foreign markets help them achieve economies of scale, resulting in possible lower costs. Service production is differentiated and enjoys increasing marginal returns, which rely on bigger market to achieve scale economies (Markusen, 1989). Case stu- dies about Chili, Mexico and Australia provide some evidences3. 4. Posing a demonstration effect. FDI in services brings multinatio nal service corporations, who, with bet- ter service output and more experienced management, are a very good opportunity for local firm to learn. The demonstration effects of service MNCs is easier to occur than that of manufacturing MNCs, because most service production and consumption cannot be separated, making it difficult to keep for technical secret. (Jiang Xiaojuan, 2004). 5. Being the key channel of cross-border technology spillover in service area. Since service consumption and production cannot be separated, the soft technology in services can only be transferred internationally through FDI. Moreover, human resources is the main carrier of the soft technology, and multinational corporations pro- vide the best organizational and institutional arrange- ments for cross-border mobility of human resources. In some service areas (e.g. advertising and management consulting), technologies are ``embedded'' in the com- plex relation ships and co mmunications within the organ- izations, which is very hard to be copied by other com- panies. But it becomes much easier when it is between headquarters and local branches of one multinational company. Finally, value chain in the production of most services can hardly be decomposed, therefore the tech- nology gap between multinational headquarter and branches in host countries is much smaller than that in manufacturing industries, making it easier for host coun- try to obtain the service technologies(Jiang Xiaojuan, 2004). Grosse (1996) finds that only a very small part of the service firms transfer technologies through channels other than FDI. 3. Model The regr essio n equat ion is the foll owing: Regression 1: ititit ititit SizeCap ForlinkBacklinkPro εαα ααα +++ ++ lnln lnln=ln 43 210 Where is the labor productivity of manufacturing industry i at the year t, which is calculated as value added divided by number of working staff. it is the capital per person, calculated as physical capital formation di- vided by number of working staff. is the avera ge size of firms in the manufacturing industry i at year t, calculated as total number of working staff divided by number of firms in the industry. it Cap and it Size are control variables, representing technological levels and economies of scale. and it Backlink are the key variables we are examining, respectively referring to forward-linkage and backward linkages between manufacturing industry and FDI in services. When constructing the two variables, the basic idea is as follows: first obtain ``the service in- put in manufacturing industries'' and ``manufacturing output that is put into the service sectors'', then catch the part of two values that is related to foreign service firms with some structural variables.. Since the dependant va- riable is labor productivity, it Forlink and it Backlink should also be per capita value, therefore number of la- bors is used to calculate the average value. Therefore, the two variables are constructed as fol- lows. = = t it it t it t it it t it SerFDI SerInput Forlink SerInv Labor SerFDI InputSer Backlink SerInv Labor × × where measures service input per person in manufacturing industry i in year t that is provided by foreign service providers; t t SerFDI SerInv is the percentage of 2 See Jesper Jense, Thomas Rutherford and David Tarr, The Impact of Liberalizing Barriers to Foreign Direct Investment in Services: The Case of Russian Acces s ion to the World Trade Organization. 3See Bernar d Hoekman et.al.(1997)  FDI in Services and Manufacturing Efficiencies in Host Countries: Evidence from China Copyright © 2013 SciRes. IB service FDI in total investment in service sectors, which give the importance of foreign firms in the service sector. it it SerInput Labor is service input per person into industry i at year t. measures the per-person average manu- facturing output that is put into foreign service firms; is the output per person of industry i in year t that is put into the service sect ors. Two points need to be mentioned here. First, for structural variable, it is better to use the percentage of output of foreign service firms in total service output. However, due to data availability problem, percentage of investment is used instead. Second, the variable con- struction can also be used to reflect the backward and forward linkage between manufacturing industries and FDI in some particular service industries. Therefore, we can have regression 2 as follows: Regre ssion 2: 01 2 34 5 6 78 9 ln= lnln ln lnln lnln ln (1) itit it itit it it itit it Protran btran rnd brandsale bsale CapSize AR αα α αα α α αα αε ++ ++ + + ++ ++ where , it trand and it sale measure forward- lin- kage effect between manufacturing industry i and FDI in transportation, R&D and retailing & wholesaling indus- tries; and the backward linkage are measured by it btran , it brnd and it bsale , respectively. Transportation, R&D and retailing & wholesaling in- dustries are chosen as typical producer services for two reasons. First, they are more of producer service nature; second, better data are available for them. Data A panel data of 15 industries with time series from year 2001 to 2008 is used. The Industry classification is based on input-output table in China. The industry classifica- tions i n ``C hina S tatist ical Ye arb ook'' a nd ``C hina I ndus- trial Economy Statistical Yearbook'' are adjusted and combined to match the input-output tables cla ssification. Data sources include China Statistics Yearbook, China Industrial Statistics Yearbook, Input- Output Table of China(2002, 2005, 2007). All the data has been adjusted to be comparable. Because input-output data are availa- ble for only limited years, input-output data for 2002 are used to represent year 2001-2003; data for 2005 represent year 2004-2005; data for 2007 are used to represent year 2006-2008. 4. Resul t Table 1 presents the estimation results, which is quite consistent with our anticipations. We have the following Table 1. Dependant variable: . Dependant variables Model 1 Model 2 Constant 6.034951*** 6.157733*** ln B acklink 0.047701** ln Forlink 0.064076** ln tran -0.267967*** ln btran 0.077903** ln rnd 0.162076*** ln brand -0.013762 ln sale 0.245397*** ln bsale 0.062997*** ln Cap 0.466369*** 0.327844*** ln 0.148883** 0.284671*** ln AR(1 ) 0.898923*** 0.903330*** Fix ef f ects 1--C 0.360211 0.312150 2--C -0.252174 -0.089820 3--C -0.582144 -0.547706 4--C -0.233206 0.160792 5--C -0.538998 -0.193214 6--C 0.296038 0.782074 7--C -0.001599 0.179099 8--C 0.035685 0.594953 9--C 0.904339 0.754525 10--C 0.060737 0.179189 11--C 0.371601 0.238329 12--C 0.091197 -0.618255 13--C 0.082510 -0.047681 14--C -0.594732 -1.381561 15--C 0.000534 -0.322864 R2 0.994580 0.998631 Adjusted R2 0.993369 0.997756 F statistics 820.9578 1141.658 D--W statistics 2.488180 2.974735 Prob(F-statistic) 0.0000 00 0.000000 Note:***, ** represent 1% and 5% significance findings: First, both forward and backward linkage ef- fects between FDI in services and manufacturing sectors are positive and significant, which indicates, on the one hand, services FDI can enhance manufacturing labor productivity through providing services inputs to the manufacturing secto rs. O n the o ther ha nd, ma nufac turin g efficiencies can also be enhanced when manufacturing firms provide inputs to Foreign Service firms, probably because foreign service firms set higher standards for their inputs, which force manufacturing firms improve their output. Secondly, we find that overall forward lin- kage is stronger than back ward linkage. FDI in transpor- tation, storage and communications has a substantial negative forward linkage effect on manufacturing effi- ciencies, but the backward linkage is positive. The nega- tive forward linkage is inconsistent with anticipation,  FDI in Services and Manufacturing Efficiencies in Host Countries: Evidence from China Copyright © 2013 SciRes. IB possibl y because there is still substantial barr ier blocking foreign investment in the industry, especially in areas like railroad transportations, basic communications and postal services. The positive backward linkage is easy to understand considering the substantial inter-industry connections with this industry. FDI scientific research and c ompr ehe nsi ve tec hno log ic al ser vice s ha s sub sta ntia l positive forward linkage effect with manufacturing in- dustries. They provide research and development, which could be direct input into manufacturing sectors, helping improve manufacturing efficiencies. FDI in retailing and wholesaling services presents the most substantial in- ter-industry linkage effects with manufacturing sectors. Both forward and backward linkages are substantially positive, and the combination of the two is the biggest among all the service industries examined. In Chinas service sectors, retailing and wholesaling is the most open to foreign investment, thus the linkage effects is easier to be realized. Retailers and wholesalers are dis- tributions channels of manufactured goods, which deter- mine the product availability, sales efficiencies and cus- tomer services. With more experienced logistic manage- ment and better technologies, foreign distributors, espe- cially multinational distributors, provides better services. On the other hand, by providing input to foreign distrib- utors, manufacturing companies efficiencies are im- proved, probably because of the higher requirement and more intense competition i n multinational distr ibutors. 5. Conclusions The paper first theoretically analyses the influences of FDI in services on efficiencies of manufacturing sectors in host co untries, then studies the forward and backward linkage effects of FDI in services on manufacturing sec- tors with an industry panel data in China. We find both positive forward and backward linkage effects exist be- tween FDI in services and Chinese manufacturing effi- ciencies. FDI in retailing and wholesaling industry has the most substantial inter-industry linkages. The finding implies that we need to have a comprehensive under- standing of the significance of service liberalization, which can not only boost the development of local ser- vice sector by injecting more completion and demonstra- tion effects, but also benefit the efficiency in manufac- turing sect ors through inter-industry linkages. The study is preliminary for the following reasons. First, due to data availabili ty proble ms, the study d oesn ’t precisely capture the input-output relationship between FDI in services and manufacturing sectors in host coun- tries. If we can get service output data and input-output data for more years, the empirical study will be more convincing. Moreover, many other channels where FDI in services influence manufacturing industries in host countries is not studied in this paper, for example, FDI in services and export of manufactured goods, interaction between FDI in services and in manufacturing sectors, which also give space for future research. REFERENCES [1] M. Amiti and J. Konings, Trade Liberalization, Interme- diate Inputs and Productivity: Evidence from Indonesia. CEPR Dis c us s ion Paper 51 04. [2] B. Hoekman and C. A. P. Braga (1997), “Protection and Trade in Services: A Survey,” Open Economies Review, Vol. 8, No. 3, 1997, pp. 285-308. doi:10.1023/A:1008246932328 [3] K. Blind and J. Andre, “Foreign Direct Investment, Im- ports and Innovations in the Service Industry,” Review o f Industrial Organization,” Vol. 25, 2004, pp. 205-207. doi:10.1007/s11151-004-3537-x [4] J. J. Boddewyn, Halbrich, Marsha Baldwin and A. C. Perry, “Service Multinationals: Conceptualization, Mea- surement and Theory,” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 17, No. 3. pp. 41-57. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490860 [5] M. Casson (1986), The Firm and the Market: Studies on Transactions Cost and the Strategy of the Firms, Chapter 2. London: Basil Blackwell/Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. [6] C. Tuan and F. Y. Ng Linda, FDI Facilitated by Agglo- meration Economies: Evidence from Manufacturing and Services Jo int Ventures in China,” Journal of Asian Eco- nomics, Vol. 13, 2003, pp. 749-765. doi:10.1016/S1049-0078(02)00183-5 [7] R. Cowan, L. Soete and O. Tchervonnaya, “ Knowledge Transfer an d t he Service S ecto r in the C ontext o f the New Economy,” MERIT-Infonomics Research Memorandum series. June, 2001. [8] P. W. Daniels, Service Industries in the World Economy, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1993. [9] A. Dixit and J. Stiglitz, “Monopolistic Competition and Optimum Product Diversity,” American Economic Re- view, 1977, Vol. 67, pp. 297-308. [10] W. J. Ethier, `National and International Returns to Scale in the Modern Theory of International Trade'', American Econ omic Review, Vol. 72, No. 2, 1982, pp . 389-405. [11] W. Ethier, “Internationally Decreasing Costs and World Trade,” Journal of International Economics, February 1979. 9. [12] Ana M. Fernandes, C. Paunov, Service FDI and Manu- facturing Productivity Growth: There is a Link. Working Paper, World Bank, April 2008. [13] J. F. Francois, “Producer Services, Services, and the Di- vision of Labor,” Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, Vol. 42, No. 4, 1990, pp.715-729. [14] J. Francoi s and J. Woerz, “Producer Services, Manufac- turing Linkages and Trade,” Tinbergen Institute Discus- sion Paper, TI2007-045/2, 2007, downloadable at http://ssrn.com/abstract=993361 [15] G. Gereffi, “The Organization of Buyer-Driven Global  FDI in Services and Manufacturing Efficiencies in Host Countries: Evidence from China Copyright © 2013 SciRes. IB Commodity Chains: How US Retailers Shape Overseas Production Networks,” In G. Gereffi & M.(Eds.), Com- modity Chains and Global Capitalism,.Westport, CT: Praeger, pp. 92-122. [16] B. Gold, “On Size, Scale, and Returns: A Survey,” Jour- nal of Economic Literature, Vol. 19, 1981, pp. 5-33. [17] H. I. Greenfield, Manpower and the Growth of Producer Services, New York & London: Columbia University Press, 19 66. [18] R. Griffith, S. Redding and H. Simpson, “Foreign Own- ership and Productivity: New Evidence from the Service Sector and the R&D Lab,” Working Paper, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, 04/22, 20 04. [19] D. M. Gross, H. Raff and M. J. Ryan, Intra- and In- ter-Industry Linkage in Foreign Direct Investment: Evi- dence from Japanese Investment in Europe. [20] R. Grosse, “International Technology Transfer in Servic- es,” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 781-800. [21] E. Helpman, M. Melitz and S. Yeaple, “Export Versus FDI with Heterogeneous Firms,” American Economic Review, 2004. doi:10.1257/000282804322970814 [22] B. Hoekman, Trade in Services a t 25: Theory, Policy and Evidence, World Bank, mimeo. [23] I. J. Horstmann and J. R. Markusen, “Firm-Specific As- sets and the Gains from Direct Foreign Investment,” Economic, New Series, Vol. 56, No. 221, pp. 41-48. [24] J. R. Markusen, “The Boundaries of Multinational Enter- prises and the Theory of International Trade,” The Jour- nal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1995, pp. 169-189. doi:10.1257/jep.9.2.169 [25] J. Arnold, B. S. Javorcik and A. Mattoo, “Does Services Liberalization Benefit Manufacturing Firms?” Evidence from the Czech Republic. September, 2006. [26] J. Jensen, T. F. Rutherford and D. G. Tarr, “The Impact of Liberalizing Barriers to Foreign Direct Investment in Ser- vices: Th e Case of Russian Accession to the World Trade Organization,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 3391. August 2004. Downloadable at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=6252 68. [27] J. Jensen, T. Rutherford and D. Tarr, The I mpact o f Libe- ralizing Barriers to Foreign Direct Investment in Services: The Case of Russian Accession to the World Trade Or- ganization. [28] J. R. Lombard, “Foreign Direct Investment in Producer Services: t he Role and Impact upon the Economic Growth and Development of Singapore,” Doctorate Dissertation of State University of New York at Buffalo. [29] M. A. Atouzian , “The Development of the Service Sector: A New Aproach,” Oxford Economic Papers, Vol. 22, 1970, pp. 362-383. [30] M. Teresa Fernandez Fernandez, “Performance of Busi- ness Services Multinational in Host Countries: Contrast- ing Different Patterns of Behaviour between Foreign Af- filiates and National Enterprises,” The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 21, No. I, pp. 5-18. [31] J. R. Markusen, T. F. Rutherford and D. G. Tarr, “Foreign Direct Investment i n Services and the Domestic Market for Expertise,” NBER Working Paper No. W7700. Downloadable at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2289 92 [32] J. R. Markusen, “Trade in Producer Services and in Ot her Specialized Intermediate Inputs,” The American Eco- nomi c Review, Vol. 79, No. 1.1989, pp. 85- 95. [33] J. M. Markusen, T. F. Rutherford and D. Tarr, “Trade and Direct In vestment in Produ cer Services and the Domestic Market for Expertise,” Canadian Journal of Economics, Vol. 38, No. 3, 2005 . doi:10.1111/j.0008-4085.2005.00301.x [34] P. Karaty and A. Poldahl, “The Determinants of FDI Flows: Evidence from Swedish Manufacturing and Ser- vice Sector,” Apr il 28, 2006. [35] R. Gross e, International Technology Transfer in Services . Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 27, No. 4, 1996, pp. 781-800. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490153c [36] A. M. Rugman, 1981, Inside the Multinationals: The Economics of Internal Markets. London: Croom Helm/New York: Columbia University P ress. [37] Y. Wolfmayr, “P ro d ucer Services and Co mpetitiveness o f Manufacturing Exports,” FIW Research Report No 009/Export of Services, June 2008. [38] N. H. Gu, D. D. Bi and W. B. Ren, Interactive Develop- ment between Producer Servicve Sectors and Manufac- turing Sectors: A Literature Review, Economist, 2006.6. [39] X. J. Jian, Service Globalization and Outsourcing: Status Quo, Trends and Theoretical Analysis, Beijing: People Press, 20 08.11. [40] X. J. Ji an g, Policy Suggestions on Expediting Service Sector Development, Review of Economic Research, 2004, 15. [41] S. T. Li and C. S. Gao, Devel op ment of Ch in ese Producer Service Sector and Upgrading of the Manufacturing In- dustrie s , Sha nghai S a nli a n Pre s s , 2008. 11 [42] L. B. Luo, FDI in Services and Efficiencies of Manufac- turing Sectors in Host Countries, International Economics and Trad e Research, 2009.8. [43] X. H. Wang, Chinese Design: Service Outsourcing and Competitiveness, Be ij ing: People Pre s s , 2008. 7

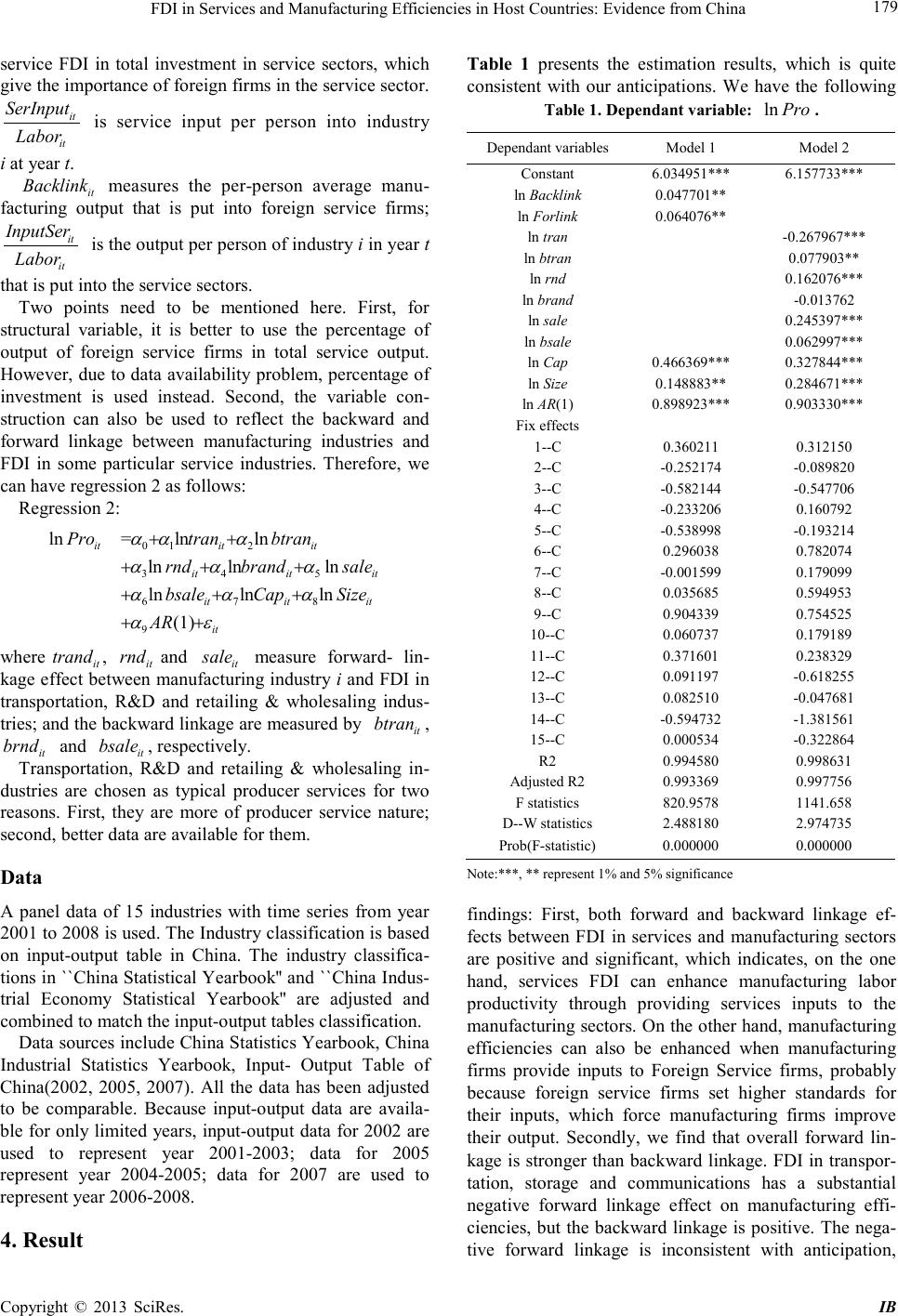

|