Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2013. Vol.3, No.4, 295-304 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2013.34037 Open Access 295 English and Malay Text Messages and What They Say about Texts and Cultures Ernisa Marzuki1, Catherine Walter2 1Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Sarawak, Malaysia 2University of Oxford, Oxford, UK Email: mernisa@cls.unimas.my, catherine.walter@education.ox.ac.uk Received September 11th, 2013; revised October 15th, 2013; accepted October 22nd, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ernisa Marzuki, Catherine Walter. This is an open access article distributed under the Crea- tive Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any me- dium, provided the original work is properly cited. This study of the pragmatics of cross-cultural text messages throws light on the evolution of new hybrid forms of literacy and on the complex ways that culture is expressed and mediated in second language/ second culture contexts. An investigation was carried out into the pragmatics of apology in first-language (L1) and second-language (L2) short messaging service text messages of adult Malay speakers who are proficient users of English, living and studying in an English-speaking university environment; and into L1 English users’ text apologies in the same context. Research questions included whether these profi- cient L2 English users would perform differently from L1 English users in this high-stakes speech act, and from their own L1 Malay use; and whether apologies in what has been called a hybrid medium would differ from those previously studied in writing, in speech and in other electronic media. Twenty-six native speakers of English and 26 native speakers of Malay responded via text messages to discourse completion tests (DCTs) in L1; the DCTs represented either high or low levels of offence calling for apologies. The Malay native speakers also responded to apology situations in L2 English. Data were coded using an adapted version of Cohen and Olshtain’s (1981) coding scheme. Analysis of the messages sent by par- ticipants revealed clear signs of a hybrid type of text that is differently conceptualised by the two commu- nities. It also showed that the Malay users’ second language literacy was shaped in a complex way that sometimes accommodated the second language/second culture and sometimes retained first language/first culture values. Keywords: Text Messages; Texting; Pragmatics; Apologies; Literacies; New Literacies Cross-Linguistic Apologies by Text Message Apology Apologies attempt to rectify social discord caused by norm violation (Scher & Darley, 1997). By apologising the speaker/ writer indicates acceptance of the violated norm, takes respon- sibility for the violation and expresses regret for it (Aijmer, 1996), thereby attempting to remedy the offence caused (Tros- borg, 1995). Apology attempts to preserve or restore the hearer’s/reader’s face (Linnell, Porter, Stone, & Chen, 1992), and is simultaneously face-threatening to the speaker/writer (Brown & Levinson, 1978). Given the importance of apology for social cohesion and the potential for loss of face in the failure of high-stakes apologies, it is not surprising that this speech act has received a great deal of attention. Characteristics of apology have been shown to be influenced by various factors, including the severity of the of- fence (e.g., Grieve, 2010; Wouk, 2005), the interlocutor rela- tionship (e.g. Mulamba, 2009; Shardakova, 2005), and gender (e.g., Holmes, 1989; Hobbs, 2003). Performances and percep- tions of apology have been extensively studied in the first lan- guage (L1) communication of native speakers of a range of varieties of English (NSEs), both adults (Grieve, 2010; Mu- lamba, 2009; Kim, 2008; Kasanga & Lwanga-Lumu, 2007; Sabate i Dalmau & Curelli i Gotor, 2007; Ancarno, 2005; Bha- ruthram, 2003; Hobbs, 2003; Nakano, Miyasaka & Yamazaki, 2000; Linnell, Porter, Stone, & Chen, 1992; Sugimoto, 1997; Olshtain, 1989) and children (Ely & Gleason, 2006; Kampf & Blum-Kulka, 2007). In Blum-Kulka, House and Kasper’s seminal 1989 work, they studied apologies in three varieties of English, and also in French, German, Danish, Russian and He- brew. They found little variation between languages in the use of the five main pragmatic strategies for apology. (Note, how- ever, that already in 1983 Olshtain and Cohen had found that, unlike English apologies, Hebrew apologies were less likely to include Offers of repair and Promises not to repeat offence than English ones.) Blum-Kulka et al. (1989) have called for more investigation of apologies in non-Western cultures. This is in large part in order to address the question of whether all human beings fol- low a universal set of politeness rules, which has been debated since Brown and Levinson’s (1978) original suggestion that faceis a universal need which is addressed by politeness. Leech (1983) proposes eight maxims of politeness; although he holds these to be universal, he concedes that different cultures vary in the extent to which they accept and/or use the maxims. Some researchers, for example Wierzbicka (1991), maintain that since each culture has its own unique norms, it is difficult to deter-  E. MARZUKI, C. WALTER Open Access 296 mine universal characteristics of politeness. Since the Blum- Kulka et al. (1989) study, there have been investigations of apologies as performed in non-Western languages, for example Sudanese Arabic (Nureddeen, 2008); Farsi (Afghari, 2007); Ciluba (Mulamba, 2009), Setswana (Kasanga & Lwanga- Lumu, 2007); Bahasa Indonesia (Wouk, 2005); Thai (Intachakra, 2004); Mandarin (Zhang, 2001); Japanese (Sugimoto, 1997); and Korean (Kim, 2008; Park, Lee & Song, 2005; Yang, 2002). Cross-Linguistic Apologies Cross-linguistic apologies have also, and just as under- standably, been investigated in several contexts. Whether po- liteness rules are universal but are realised differently in differ- ent cultures or cannot be considered as universal at all, it is clear, as Mey (2001) notes, that pragmatic meanings are based on societally-imposed conditions, and that at some level prag- matic rules may differ from one society to another, resulting in clashes of beliefs about what is polite and what is not. For this reason cross-cultural apologies, as a potentially sensitive area of politeness, have been the subject of several studies. There have been a number of studies of various L1 - L2 (and Dialect 1 - Dialect 2) pairings, for example English-French (Cohen & Shively, 2007); English-Spanish (Cohen & Shively, 2007; Shively & Cohen, 2008); English-Russian (Shardakova, 2005); German-French (Warga & Scholmberger, 2007); Aus- trian German-German German (Clyne, Fernandez, &Muhr, 2003); Swedish-German (Bohnke, 2001). However, the largest number of cross-cultural apology studies have compared apolo- gies by native speakers of English (NSEs) with those bynon- native speakers of English (NNSEs). Some studies of NNSE apologies have investigated a range of first languages (e.g., Linnell, Porter, Stone & Chen, 1992; Ancarno, 2005). Others have focused on NNSEs from specific L1 backgrounds, for example Catalan (Sabate iDalmau & Curelli iGotor, 2007); German (Grieve, 2010); Korean (Yang, 2002); Japanese (Na- kano, Miyasaka, & Yamazaki, 2000); Cantonese (Rose, 2000); Mandarin (Chang, 2008); and Setswana (Kasanga & Lwanga- Lumu, 2007). There is one investigation of Malay NNSE apologies (Maros, 2006), in which participants completed writ- ten DCTs to record what they would say in spoken English situations; this study will be discussed below. Malay “Cultural Scripts” and Apology Previous studies have linked cultural concepts to perceptions of politeness. For example, Chang (2008) investigated the per- ceptions of Taiwanese NS of Mandarin and Australian NSEs who listened to recordings of apologies and completed both a questionnaire and a post-listening interview about levels of politeness in apologies; Chang concluded that the Taiwanese participants’ perceptions were linked to Chinese cultural con- cepts. The Taiwanese participants in this study were argued to base their perceptions on the Chinese cultural concepts of bu- haoyisi (I feel embarrassed) and chengyi (sincerity). Notably for the current discussion, Goddard (1996, 1997) has carried out a careful analysis of a number of Malay “cultural scripts”, based on his own data and on a re-analysis of data reported by a range of Malay and non-Malay researchers of the culture, using Wierzbicka’s (1996) Natural Semantic Metalan- guage framework. This means that there is a solid foundation for reflecting on possible cultural influences on Malay NNSE apologies. Findings relevant to the present investigation of apologies are that in the Malaysian culture: It is important to be well-mannered or refined (halus) as opposed to coarse (kasar). “A great deal of what it means to be halus hinges on one’s speech” (Goddard, 1997: p. 186). It is not appropriate to make explicit reference to one’s own feelings or to the feelings of others; people are expected to be sensitive enough to understand how other people are feeling, and to be considerate towards their interlocutor’s feelings. Rather than make direct reference to an offence, “[i]f I must say something, it should be vague” (Goddard, 1997: p. 193). Goddard gives as an example of an appropriate utterance “If yesterday I did/said something [uncouth], I ask for pardon” (Goddard, 1997: p. 193). It is not polite to voice wishes about what other people should do. It is interesting to compare Goddard’s findings to the socio- pragmatic components of apologies as categorised by the stan- dard taxonomy introduced by Cohen and Olshtain in 1981 (later expanded by Blum-Kulka et al., 1989): 1) Illocutionary force indicating device (IFID): an explicit expression of apology, e.g. “sorry”, “forgive me”, “I apologise” 2) Explanation or account, e.g. “someone bumped into me” 3) Acknowledgment of responsibility, e.g. “I was careless” 4) Offer of repair, e.g. “I will buy you a new vase” 5) Promise not to repeat offence1 In the Malay context, two of the sample IFIDs would seem to be problematic: “sorry” would appear to be excluded as refer- ring to one’s own feelings; “I apologise” appears to be too di- rect a reference to the offence. In this regard it is interesting that Maros’s (2006) 27 Malay participants, who each completed written English DCTs reporting what their oral response would be in six situations, often used “Please forgive me” or “Excuse me” in situations of serious offence or of offence to a high- status interlocutor. “Please forgive me” comes closer to God- dard’s (1997) “I ask for pardon” than does a straightforward apology—as does “Excuse me” if its literal meaning rather than its standard illocutionary force is taken into account. The other four categories appear to make direct reference to the offence. However, the L1 Malay avoidance of direct refer- ence was not evident in the English responses of Maros’ (2006) Malay participants, for whom Explanation or account was the most frequent strategy, followed by Acceptance of responsibil- ity. In Maros’ study, 27 Malay NNSEs’ written DCT apologies in English were collected for six situations. Maros attributed some of the characteristics of her participants’ responses to transfer from Malay cultural norms, e.g. over-formality in low- risk encounters. Maros’ participants had not lived outside Ma- laysia, and she attributes the persistence of L1 pragmatic pat- terns to the fact that their English had been spoken almost ex- clusively with other Malaysians; this hypothesis will be tested by the present study, where the Malay speakers were all living and studying in the UK. Note too that Maros’ results can only be suggestive. The written DCT format has been criticised, for example by Woodfield, whose (2008) study of NSEs’ responses to written DCTs found that written responses deviated from 1This is commonly called promise of forbearance in the literature (e.g., Blum-Kulka et al., 1989; Olshtain, 1989; Trosborg, 1987; Scher & Darley, 1997), but this does not correspond to the standard meaning of forbearance in English. Therefore, we have chosen to use Bataineh and Bataineh’s (2008) more transparent label.  E. MARZUKI, C. WALTER Open Access 297 corresponding spoken responses. Further, in Maros’ study there was no comparison NSE group, there were no comparison DCTs completed in Malay, Olshtain’s (1983) taxonomy was not applied in a conventional way, and the results are not re- ported in detail. Medium of Apology: Speech, Writing, and E-Communication A further variable taken into account in this study was the medium in which the apology is performed. Most of the studies cited above have dealt with either written or spoken apologies. While there has been some recent interest in apologies con- veyed electronically, we found only one study of the pragmatics of text messages, and we argue that within the general category of electronic communication text messages present specific affordances. Some authors (Collot & Bellmore, 1996; Gains, 1999; Gi- menez, 2000; Crystal, 2008a, 2008b) argue that the language used in electronic means of communication such as emails, instant messaging (IM) and Short Message Service (SMS) text messages (henceforth text messages or texting) manifests a sufficient number of distinctive characteristics for it to be con- sidered a new medium alongside speech and writing. Electronic communication, it is suggested, is a hybrid medium manifesting some features of written language and some features of spoken language. Some writers (e.g. Baron, 2000) argue that electronic communication presages a move towards a unified standard which will have more characteristics of spoken language than of written language. While spoken and written language can be seen as existing on a continuum, prototypical spoken language happens in real time, is unplanned, is face to face, and reflects an immediate interpersonal situation (Carter & McCarthy, 2006: p. 164); while prototypical written language enjoys relative permanence; lacks face-to-face contact, forcing both increased explicitness (because of fewer shared contextual elements and because of the lack of contemporaneous feedback) and the need for proxies for suprasegmental and paralinguistic features; and adheres to formal conventions (Crystal, 2005: pp. 149-151). The degree to which the affordances of text messaging can be said to correspond to these characterisations of speech or writ- ing is problematic. Table 1 demonstrates the difficulty of situ- ating text messages within the paradigm. Indeed, within the general category of electronic communi- cation, it can be argued that the affordances of text messages differ substantially even from those of email and instant mes- saging (IM). Differently from email, although there is no longer, Table 1. Comparing characteristics of spoken and written language with texting. Prototypical Speech Prototypical Writing Text Messages In real time Yes No Optionally Unplanned Yes No Optionally Face to face Yes No No Immediate interpersonal situation Yes No Optionally Explicitness No Yes Yes? Formal conventions No Yes ? as before, a strict limit on the number of characters in a text message, text message format still tends to be restricted by the size of the mobile/cellphone screen. Differently from IM, text messages are sent without the knowledge of when the inter- locutor will receive the message, and with the possibility but not the firm expectation of an immediate response. These dif- ferences lead to the hypothesis that the pragmatics of text mes- saging may be substantially different from those of email or IM. Some support for this hypothesis is provided by Baron (2004: p. 84), who found that US American university students consid- ered that emails (in contrast with IM) should be “edited, punc- tuated, spellchecked, and more formal”. Studies of electronic communication thus far (e.g. the various chapters in Danet & Herring, 2007; Ling & Baron, 2007), in- cluding one study of text messaging in Malay (Badrul Redzuan, 2006) have mainly concentrated on the word-and sentence-level characteristics of the medium or on the patterns of code- switching and code-mixing in text messages. Less work has focused on the discourse/pragmatic features of the medium, and only Maros (2006) focuses on the pragmatic features of text messages. There have been a few studies of the pragmatics of apologies by email. Hatipoğlu (2004) studied 126 emails: (a) one-to-one (n = 56); (b) group from individual (n = 46); and (c) group from official representative (n = 32) email apologies sent between 2002 and 2004, in English, in the context of a British university department. The most marked difference was in the degree to which apologies were intensified in the different conditions, with intensified apologies containing words such as very, really and so occurring much more often in the one-to-one condition and only once in the group-from-official condition; group- from-individual apologies split almost equally between intensi- fied and non-intensified apologies. Ancarno (2005) investigated a corpus of 66 letters and 86 emails to and from the editors of research journals written in English by NSEs and NNSEs in three academic disciplines, looking inter alia at the apologies in these emails. He found that the writers of conventional letters tended to use “full” apologies, with clear acknowledgment of responsibility, or to use intensifiers in expressing their apologies, more than writers of emails, who tended more towards “elliptical” apologies. However, the email apologies tended to be for lower-stakes offences, which may have been a confounding variable. An- carno found no significant variations between NSEs and NNSEs in the pragmatic characteristics of the apologies. Research Questions This study focuses on two areas: the potentially distinctive characteristics of a representative speech act, apology, as real- ised in text messages; and the potential for cross-cultural prag- matic differences between the apologies of NSEs and Malay NNSEs, as an under-researched linguistic/cultural pairing. Three research questions emerge from the intersection of these areas: 1) Can text message apologies in L1 and L2 English and L1 Malay be characterised in any sense as a hybrid medium be- tween speaking and writing? 2) What if any are the pragmatic differences between text message apologies in L1 English and those in L1 Malay? 3) Do highly proficient Malaysian speakers of English dem- onstrate any Malay pragmatic characteristics in their English  E. MARZUKI, C. WALTER Open Access 298 text messages? Methodology Participants 26 native speakers of Malay (NSMs) (11 males, 15 females) and 26 NSEs (10 males, 16 females) participated in the study. All participants were undergraduate or postgraduate students in universities in the United Kingdom. The participants ranged in age between 19 and 41 years of age, with a mean age of 24.8 for English participants (SD: 5.32) and 25.5 for Malay partici- pants (SD: 3.71). NSM participants had obtained at least a 6.5 on the International English Language Testing System (IELTSTM) examination, 550 on the paper TOEFL®, 213 on the computer-based TOEFL®, or A1 in GCSE O-level plus the International Baccalaureate®. At the time of the study, all NSM participants had been in the UK for no less than 2 months and no more than 44 months (mean 16 months, SD: 10). Partici- pants were selected through snowball sampling. Even though the use of snowball sampling decreases the possibility of the sample being representative of the whole population, this sam- pling method was chosen to increase the possibility of recruit- ing participants who met the criteria, and especially the criteria for the NSM group. Materials Data was collected by Discourse Completion Task (DCT) through text messages. This methodology gives a degree of ecological validity to the data and is less vulnerable to the criti- cisms of written DCTs for spoken situations voiced by Wood- field (2008). The DCT scenarios were designed specifically for text messaging. Since there was no precedent for texted apol- ogy situations, the situations were designed by the researchers based on previous apology studies such as those in the Cross- Cultural Speech Act Realisation Project (Blum-Kulka et al., 1989). A preliminary study was carried out to identify 4 situations to be used in the main research. Eleven situations were de- signed and evaluated. The 11 situations were then given to 10 participants (five NSMs and five NSEs) who were not involved in the main research. The participants were asked to rank the 11 situations from No Risk to Very High Risk of continuing or exacerbating the offence. Risk was defined in relation to how serious the norm violation was, and the consequent likelihood that the receiver would be offended by an apology that they perceived as insufficient. To avoid participants’ choosing a middle ground such as Neutral or Unsure, a six-point Likert scale was employed, with 1 representing a No Risk Situation and 6 representing a Very High-Risk Situation. This yielded four situations for the main study: the two with the highest medians (of 5 and 4) for use as High Risk (HR) situations (for- getting a meeting with a lecturer, forgetting to return a library book for one’s supervisor) and the two with the lowest medians (of 2 and 1) as Low Risk (LR) situations (forgetting to meet a cousin, accidentally sending a text message to a wrong number). These four situations were then edited in English and Malay versions in order to make them more text message-like. The receiver of the apology was specified as female in three of the situations and unspecified in the fourth situation. This is be- cause in Holmes’ (1989) study of 183 remedial interchanges by New Zealanders in various contexts, male and female-directed apologies were shown to differ: both men and women apolo- gised more often to women. Note that the differences in social status between the apologiser and the receiver contribute to the risk level in all four cases, and we do not intend to investigate social distance separately in this study. A pilot study was conducted one month before the main study. Four NSMs and four NSEs selected from the same sam- ple pool as the main study responded to the four situations. As a result of the pilot study, one of the situations was slightly edited for clarity; and participants in the main study were given a choice of receiving the prompts for the DCTs via phone calls or text messages (although in the event no main study participants opted for phone calls). The exact texts as sent to the main study participants in English and Malay are given in Appendix A. Procedure NSMs were required to respond to all four different situa- tions, two in Malay and two in English. NSEs were only re- quired to respond to two different situations, both in English. Each NSE responded to one HR situation and one LR situation; the situations were counterbalanced across the sample, so that each situation received an approximately equal number of NSE responses. For the NSM participants, the language used for each situation was counterbalanced across the group to avoid an effect of situation. The order of administration of the situations was also counterbalanced to avoid practice and fatigue effects. Participants were asked to respond to the situations by texting the message which they would text if they were in the situations described. The inclusion of textisms in the stimulus texts im- plicitly encouraged the use of this convention. On the agreed day, a researcher contacted the participants to ensure that they were prepared to send and receive text mes- sages. In cases where participants could not be reached or had to postpone texting, new dates were set. Only after the partici- pants declared that they fully understood what was expected from them did the data collection began. The participants were required to send a text message which stated “OK” to start the data collection. Once this was received, the researcher sent the first situation to the participant via text message. For ecological validity, there was no time limit, as in an authentic context, a person might take some time to compose a text message. How- ever, the participants were reminded that they had to treat the situation as urgent, thus discouraging them from taking too long. In the three cases (two NSMs and one NSE) where par- ticipants did not respond after 1.5 hours, the researcher re-sent the situation, which successfully prompted all participants’ responses. Upon receiving the response to the first situation, the researcher sent the second situation. In the case of the NSM participants, the process was repeated until the fourth situation. After the final response by the participant, the researcher sent a text message indicating that the data collection was complete and thanked the participant. The researcher offered compensa- tion (GB £1.00 phone credit for each participant); all partici- pants except two declined. Results Sociopragmatic Coding System A total of 156 responses were collected from participants, with 26 High-Risk (HR) and 26 Low-Risk (LR) responses in each of three categories:  E. MARZUKI, C. WALTER Open Access 299 NSM-L1: L1 Malay responses from native speakers of Malay NSM-L2: L2 English responses from native speakers of Malay NSE-L1: English responses from native speakers of English A coding scheme was developed based on Cohen and Olshtain’s (1981) scheme as revised by Blum-Kulka et al. (1989), comprising categorisation of component sociopragmatic strategies, each with several different potential pragmalinguistic realisations. Changes to the scheme were based on the patterns which emerged from the actual responses from the participants. As a result, ten types of pragmalinguistic realisations were omitted from the Blum-Kulka et al. (1989) scheme and three sociopragmatic strategy categories were added. The resulting sociopragmatic categories are given below (new categories emerging from the data are marked with asterisks), and the full coding scheme is given in Appendix B. 1) Alerter: word(s) used to start the message and thus alert the receiver to the message. 2) Illocutionary Force Indicating Device (IFID) 3) Taking/minimising/denying responsibility 4) Explanation or account: an explanation of how the event was out of the apologiser’s control 5) Offer of repair 6) Promise not to repeat offence 7) Distracting from offence 8) Closing statement*: a type of complimentary close (e.g. “best wishes”, “regards”). 9) Thanking receiver* 10) Concern for receiver/show of empathy*: a show of concern or empathy for the receiver who may be affected by the offence 11) Others: other strategies which do not fit into to any of the previous codes. Initial coding involved dividing each text message into seg- ments. Thus a text message like “sorry for the earlier msg. ac- cidentally send [sic] it to the wrong person. sorry” would be considered as containing three segments. Each segment was then coded into its sociopragmatic moves and their pragmalin- guistic realisations. 72 of the 156 messages (24 selected randomly from each of the three categories) were coded by a second rater to test reli- ability. The second rater was a university lecturer with a Mas- ter’s degree in psycholinguistics who was teaching at a public university in Malaysia at the time of the study. Inter-rater reli- ability was 86.1%. Cases of disagreement were discussed and consensus reached, and the remaining 74 messages were coded on the basis of these discussions. This produced a rich data set, of which only the most relevant results will be reported in detail and discussed below. Analysis of So ci opragmatic Str ategy Use Strategy Differe nc e s between Groups and Languages The frequency of each category of sociopragmatic strategy was calculated. In the very rare cases where the same strategy appeared more than once in the same text message it was only counted once. Significant differences were calculated; the re- sults are given in Tables 2 and 3. High and Low Risk Categories The situations had been designed to represent risk-level catego- ries, High-Risk (HR) and Low-Risk (LR), and there were two situations in each category. Fisher’s exact tests (because of small numbers in cells) were carried out by risk category and participant group to test the validity of the categories. There were no significant differences between the two situations in each risk level for any strategy except Offer of repair, where the NSM group showed significant differences between both the two HR situations and the two LR situations (p < 0.01) and the NSE group showed significant differences between the two situations for the LR category only (p < 0.01); and Alerters, where the NSM group showed a significant difference between the two LR situations only (p < 0.01). Therefore, these catego- ries were excluded from analysis of differences between the two risk levels. A small number of differences were found between HR and LR responses; all differences are reported here as determined Table 2. First-language apologies by English and Malay native speakers. Sociopragmatic strategies in L1 Malay L1 (NSM) English L1 (NSE) Alerter 36 33 Illocutionary force indicating device 52 52 Taking/minimising responsibility 52 50 Explanation 1 2 Offer of repair 27 30 Promise not to repeat offence 1 2 Distracting strategy 12 6 *Closing statement 1 20 Thanking the receiver 4 1 Expressing concern/empathy 10 4 Note: *Fisher’s exact test (one-tailed) shows a significant difference at p < 0.05. Table 3. Apologies by native speakers of Malay (NSMs) in two languages. Sociopragmatic strategies of Native Speakers of Malay (NSM) Malay L1 English L2 Alerter 36 35 Illocutionary force indicating device 52 51 Taking/minimising responsibility 52 52 Explanation 1 2 Offer of repair 27 29 Promise not to repeat offence 1 2 Distracting strategy 12 14 *Closing statement 1 7 Thanking the receiver 4 4 *Expressing concern/empathy 10 2 Note: *Fisher’s exact test (one-tailed) shows a significant difference at p < 0.05.  E. MARZUKI, C. WALTER Open Access 300 by Fisher’s exact tests, p < 0.05. When each group was ana- lysed separately, the Native Speakers of Malay used a signifi- cant number of Low-Risk but no High-Risk Distracting strate- gies, both in L1 Malay (HR = 0, LR = 12) and in L2 English (HR = 0, LR = 14). The Native Speakers of English used sig- nificantly more High Risk than Low Risk Closing statements (HR= 15, LR = 5). When L1 performance was compared, Na- tive Speakers of Malay used significantly more L1 Low Risk Distracting strategies than their NSE counterparts (NSM = 12, NSE = 5). Unlike the Native Speakers of Malay in L1, the Na- tive Speakers of English used a significant number of Closing statements in L1 High Risk situations (NSM = 0, NSE = 15) (but the low number of Low Risk Closing statements did not differ significantly in the two groups’ L1 use (NSM = 1, NSE = 5)). Pragmalinguistic Realisations of Strategies This section examines the pragmalinguistic realisations of those socio pragmatic categories where significant differences between groups, first and second language or levels of risk were found; it also examine show pragmalinguistic realisations of other categories may contribute to answering the research questions. Closing Statements In the two L1s, the only significant difference between the NSM and NSE groups was in the English native speakers’ fre- quent use of closing statements. In addition, there is evidence that the NSEs and the NSMs were using this strategy in very different ways. Most of the English L1 Closing statements were used in High Risk situations. These statements were either conventional complimentary closes like “Best wishes” and “Regards” (in 5 of the 15 NSE responses) or a quasi-signature, i.e. the name of the sender (in all 15 of the responses), occur- ring in all cases at the end of the message. This clearly indicates that some NSEs in the study conceptualise high risk text mes- sage apologies as written medium texts requiring adherence to formal conventions. On the other hand, in only 6 of the 15 HR responses where NSEs made these statements did they begin the message with a formal Alerter, such as a title or “Dear X” or both; their writers may have been responding to the enforced brevity of the text message, or they may have been, consciously or not, crafting a message that was a hybrid between writing and speech. The hybridity of this text creation is reinforced by the fact that these same messages also contain approximations of speech such as ellipsis (“Just wanted to say again how sorry I am”) and indications of prosody (“I’m *very* sorry”). How did this use of Closing statements by the NSEs compare to the NSMs’ use of the strategy? Only one NSM used a Clos- ing statement in L1, in a Low Risk situation, and this was a code-shift to English (“Luv ya. X.”). NSMs used quasi-signa- tures three times in L2 English, all in HR situations; but they all came at the beginning of the message (“Hello mdm. this is reza”; “Dr, its Sara”; “Hi, Mrs Smith, this is maya”). The NSMs’ use of quasi-signatures in English is very different from the NSEs’ use of them: it resembles phone conversation con- ventions. Likewise, although the four Closing statements that NSMs used in LR situations were complimentary closes, they were not formal ones: there were three tokens of “Cheers!” and one of “Enjoy your weekend!”. Again, these are arguably more like spoken than written language. In other words, not only did the NSMs hardly use Closing statements in L1, but all of their uses of this strategy were more speech-like than writing-like, marking an even clearer difference between the two groups and a more uniform use of this strategy by each group than the ini- tial quantitative analysis indicates. Alerters While there were no overall differences in the use of this strategy, how it was realised did differ between the two groups. Notably, the NSM used formal address in 23 cases in L1 Malay, compared to only 4 cases of formal address by the NSE group— all of these in HR situations, unsurprisingly. This seemed to carry over to the NSMs’ L2 responses, with 12 cases of formal address in English. Given the great importance in Malay culture of being refined, and of appearing to be so, it is perhaps not surprising that the Malay respondents used formal address even in their English texts. However, formal forms of address co- existed with abbreviations and speech-like language in the same texts, underlining once again the hybrid nature of these texts. Minimising Responsibility: Avoiding Mentioning the Offence Although more often than not the offence was explicitly mentioned as a means of acknowledging responsibility, par- ticipants in both groups also frequently avoided mentioning the offence too directly (e.g. “I thought that our meeting will be tomorrow and I just realized it just now”; “[I’m sorry for] not been able to meet you today”. “i js realized tht I hvnt returned ur book 2libry yet”. There was no indication of a difference between the two groups in this area. This less explicit way of alluding to the offence might be seen as appealing to the kind of common ground that is more usual in spoken than in written exchanges. Interestingly, both groups pushed their responsibility into the background in this way more often in High Risk than Low Risk situations (NSE: HR = 12, LR =4; NSM L1: HR = 10, LR =3; NSM L2: HR = 15, LR = 7). This may reflect the greater threat to the apologiser’s face posed by a High Risk apology. Expressing Concern or Empathy One difference in L1 and L2 use by the NSMs was in the number of expressions of concern/empathy (10 in L1, of which 4 in HR, 6 in LR situations; only 2 in L2, both in LR situations). In L1 HR situations the concern regards the receiver’s having had to wait unnecessarily for the apologiser. In the L1 LR situations, concern is also expressed about making the receiver wait (twice), but also about disturbing the receiver (twice), about the receiver’s whereabouts (once) and generally about the receiver’s well-being (once). This increased attention to the receiver’s feelings in the L1 Malay situations over the L2 situa- tions appears to correspond to Goddard’s (1997) observation that in Malay culture it is important to be considerate towards other people’s feelings without having to be alerted to these: “Part and parcel of being brought up Malay is learning to an- ticipate others” wishes and, as far as possible, to accommodate them (Goddard, 1997: p. 194). The increased attention to other people’s feelings is what would be predicted if texting in Malay evoked Malay cultural values for the NSMs in a way that tex- ting in English did not. Distracting Strategies The L1 Malay speakers used a significant number of low-risk  E. MARZUKI, C. WALTER Open Access 301 but no high-risk Distracting strategies, in L1 Malay (LR = 12, HR = 0) and in L2 English (LR = 14, HR = 0). (The L1 English speakers only used 6 Distracting moves, but the difference between these and the L1 Malay users’ Distract- ing moves did not reach significance.) Most of the Distracting moves (9 out of 12 for L1 Malay, 10 out of 14 for L2 English) were requests to the offended party for something other than forgiveness, e.g. “Plz,plz say u’r not mad at me :p”, “Call me back please?”, “Erm, pls ignore it”; there were also some in- stances of humour and of offers of unrelated gifts or favours (“I will buy you dinner”, “aku belanja makan”). The Malay users’ extensive use of distraction strategies relates well to Malay cultural scripts as described by Goddard (1997). Firstly, all of these ways of distracting allow the apologiser to avoid making direct reference to the offence, which is highly preferable in Malay culture to avoid loss of face for the apologiser. Secondly, given the Malaysian social stricture against expressing wishes about what other people should do, it may well be the perceived higher social status of the receivers in the HR situations that prevent NSM participants from asking them to say or to do something and means that all of the NSM distracting moves were in Low Risk situations. It is interesting that the Malay users have not differentiated between the L1 and L2 situations here, given that they have done so for some other pragmalin- guistic realisations; perhaps hierarchical relationships tend to feel similar between their two cultures. Discussion Written or Spoken, or Hybrid? This study has provided evidence that text apologies can in- deed be characterised as a hybrid genre; and differentially so for different communities of users. One indication that texts resemble spoken discourse is the prevalence of moves in the corpus where members of both groups avoided mentioning the offence they were texting about when communicating in L1, contrary to the expectation of explicitness in written text. Omit- ting to mention the offence was more frequent in high-risk than in low-risk situations, and whereas in other cases in the study, high-risk situations seemed to prompt more formal, more writ- ten-like text, in the domain of mentioning the offence this was not the case. It is striking that both of the language/culture groups avoided mentioning the offence in their L1 apologies. It will be interesting to investigate text apologies in other L1s, to examine whether this lack of explicitness in referring to an offence is a common aspect of this aspect of the developing genre across cultures. An even more powerful demonstration of the hybrid nature of these texts is the case of the openings and closings of the high risk text apologies. When finishing their high risk apology texts, the English L1 users employed complimentary closes that would have been appropriate in a traditional letter, and often added quasi-signatures as well; yet these same writers were far from systematic in beginning these texts formally. In contrast, the Malay L1 users never used formal complimentary closes, and when they did give their names in their texts, they did so at the beginning, as if in a telephone call; at the same time, they used formal letter-type salutations and professional titles, often in their first language texts and sometimes in those they wrote in the second language. These two groups of texters appear to have developed distinctive language/culture-specific genre conventions which, in different ways for each culture, posi- tioned the text apology somewhere between writing and speech. Culturally Specific Pragmatics In this study’s examination of the differences between the first-language sociopragmatics of the two groups and the ways in which strategies were realised pragmalinguistically, an initial impression of uniformity gave way to a more nuanced picture. For example, on a macro level, there appear to be few differ- ences between the L1 text messages of native speakers of Ma- lay and the L1 text messages of native speakers of English. Both groups use the same sociopragmatic strategies, and for all but one strategy (Closing statements) the frequencies of use were not significantly different. However, closer examination reveals that the pragmalinguistic realisations of these strategies did differ, sometimes in important ways. For example, while the difference did not reach significance, NSEs did not express concern or empathy as often as NSMs; and more importantly, the NSMs expressed concern or sympathy significantly more often in L1 Malay than they did in L2 English, in ways that corresponded well to the cultural scripts that Goddard (1996, 1997) has articulated to characterise Malay culture. This sug- gests that the Malay native speakers were, consciously or not, tailoring their responses to the perceived norms of two different cultures. In the case of strategies for distracting from the offence, a different pattern obtained. Again, the NSEs used fewer of these strategies than the NSMs, and again without this difference reaching significance. However, what is interesting here is that while the NSMs made a clear distinction between low risk and high risk situations—with abundant use of these strategies in low risk situations and none in high risk ones—they did this in the same way in first and second languages. Although they are highly proficient speakers of English, living and working in an English speaking environment, it appears that the NSMs retain in the second culture those first-culture norms which prompt them to distract interlocutors with a request for action in a low risk situation, but not in a high-risk one, when the offence is a serious one with substantial face-threatening potential for the interlocutor. This runs counter to the conclusions of Maros (2006), who argued that adherence to first-culture norms in apologies was probably an effect of her participants having spoken English almost exclusively with Malay interlocutors. The current study suggests that some cultural norms may be more resistant to acculturation than others. These two examples of expressions of concern/empathy, on the one hand, and distracting strategies, on the other, reveal a nuanced negotiation of second language/second culture mem- bership by L2 users navigating their two worlds in a complex way, sometimes accommodating to the second culture and sometimes retaining first culture pragmatic usages. It is only detailed study of particular cases that allows this kind of insight to emerge. Implications and Future Research The phenomena that have come to light in the present study have obvious implications for cross-cultural texting. In a cross- cultural text apology, differing practices and expectations have the potential to lead to the offended party’s perceiving the be- haviour of the apologiser as inappropriate, with potentially  E. MARZUKI, C. WALTER Open Access 302 serious consequences. The resistance of the acculturated L2 English texters in the current study to alteration of some aspects of their first-culture apology convention suggests that implicit learning of new norms in this area may not be effective. There- fore, an obvious next step is to examine perceptions of cross- cultural texters receiving apologies that do not correspond to their (possibly unconscious) expectations. This in turn can lead to the incorporation in language teaching materials of aware- ness raising with regard to these issues. In a situation where English is a lingua franca, it may be worth carrying out similar studies with each of the first language/culture groups involved, to inform the development of appropriate teaching materials. REFERENCES Afghari, A. (2007). A sociopragmatic study of apology speech act realization patterns in Persian. Speech Communication, 49, 177-185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2007.01.003 Aijmer, K. (1996). Conversational routines in English. Convention and creativity. New York: Addison Wesley Longman Limited. Ancarno, C. (2005). The style of academic e-mails and conventional letters: Contrastive analysis of four conversational routines. Iberica, 9, 103-122. Badrul Redzuan, A. H. (2006). New media language: “Txtgda trickster talk”. In L. S. Chin, & T. K. Hua (Eds.), Composing meanings: Me- dia text and language (pp. 41-59). Bangi: UKM. Baron, N. S. (2000). Alphabet to email: How written English evolved and where it’s heading. London: Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203194317 Baron, N. S. (2004). Rethinking written culture. Language Sciences, 26, 57-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2003.06.001 Bataineh, R. F., & Bataineh, R. F. (2008). A cross-cultural comparison of apologies by native speakers of American English and Jordanian Arabic. Journal of Pragmatics, 40, 792-821. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.01.003 Bharuthram, S. (2003). Politeness phenomena in the Hindu sector of the South African Indian English speaking community. Journal of Prag- matics, 35, 10-11. Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., & Kasper, G. (1989). Cross-cultural prag- matics: Requests and apologies. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation. Bohnke, C. (2001). On the acquisition and learning of linguistic-prag- matic competence exemplified by the speech act “apologizing”. Moderna Sprak, 95, 165-191. Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1978). Universals in language use: Polite- ness phenomena. In E. N. Goody (Ed.), Questions and politeness (pp. 56-289). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Carter, R., & McCarthy, M. (2006). Cambridge grammar of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chang, W. (2008). Australian and Chinese perceptions of (im)polite- ness in an intercultural apology. Griffith Working Papers in Prag- matics and Intercultural Communication, 1, 59-74. Clyne, M., Fernandez, S., & Muhr, R. (2003). Communicative styles in a contact situation: Two German national varieties in a third country. Journal of German Linguistics, 15, 95-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1470542703000278 Cohen, A. D., & Olshtain, E. (1981). Developing a measure of so- ciocultural competence: The case of apology. Language Learning, 31, 113-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1981.tb01375.x Cohen, A. D., & Shively, R. L. (2007). Acquisition of requests and apologies in Spanish and French: Impact of study abroad and strat- egy-building intervention. Modern Language Journal, 91, 189-212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00540.x Collot, M., & Belmore, N. (1996). Electronic language: A new variety of English. In S. C. Herring (Ed.), Computer mediated communica- tion: Linguistic, social and cross-cultural perspective (pp. 13-28). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins. Crystal, D. (2005). How la n gu a g e w orks. London: Penguin Books. Crystal, D. (2008a). Texting. ELT Journal, 62, 77-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccm080 Crystal, D. (2008b). Txtng. The gr8 db8. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Danet, B., & Herring, S. C. (2007). The multilingual internet: Lan- guage, culture, and communication online. Oxford: Oxford Univer- sity Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195304794.001.0001 Ely, R., & Gleason, J. B. (2006). I’m sorry I said that: Apologies in young children’s discourse. Journal of Chi ld L angu age, 33, 599-620. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0305000906007446 Gains, J. (1999). Electronic mail—A new style of communication or just a new medium?: An investigation into the text features of e-mail. English for Specific Purposes, 18, 81-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(97)00051-3 Gimenez, J. C. (2000). Business e-mail communication: Some emerg- ing tendencies in register. English for Specific Purposes, 19, 237-251. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(98)00030-1 Goddard, C. (1996). The “social emotions” of Malay (BahasaMelayu). Ethos, 24, 426-464. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/eth.1996.24.3.02a00020 Goddard, C. (1997). Cultural values and “cultural scripts” of Malay (BahasaMelayu). Journal of P r agm atics, 27, 183-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.106/S0378-2166(96)00032-X Grieve, A. (2010). “Aberganzehrlich”: Differences in episodic structure, apologies, and truth-orientation in German and Australian workplace telephone discourse. Journal o f Pragmatics, 42, 190-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.05.009 Hatipoğlu, Ç. (2004). Do apologies in e-mails follow spoken or written norms? Some examples from British English. Studies about Lan- guages, 5, 21-29. Hobbs, P. (2003). The medium is the message: Politeness strategies in men’s and women’s voice mail messages. Journal of Pragmatics, 35, 243-262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00100-5 Holmes, J. (1989). Sex differences and apologies: One aspect of com- municative competence. Applied Linguistics, 10, 194-213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/applin/10.2.194 Intachakra, S. (2004). Contrastive pragmatics and language teaching: apologies and thanks in English and Thai. RELC Journal, 35, 37-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/003368820403500105 Kampf, Z., & Blum-Kulka, S. (2007). Do children apologize to each other? Apology events in young Israeli peer discourse. Journal of Politeness Research, 3, 11-37. Kasanga, L. A., & Lwanga-Lumu, J.-C. (2007). Cross-cultural linguis- tic realization of politeness: A study of apologies in English and Setswana. Journal of Politeness Research, 3, 65-92. Kim, H. (2008). The semantic and pragmatic analysis of South Korean and Australian English apologetic speech acts. Journal of Pragmatics 40, 257-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.11.003 Leech, G. (1983). Principles of pragmatics. London: Longman. Ling, R., & Baron, N. S. (2007). Text messaging and IM: linguistic comparison of American College Data. Journal of Language and So- cial Psychology, 26, 291-298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0261927X06303480 Linnell, J., Porter, F. L., Stone, H., & Chen, W. (1992). Can you apolo- gize me? An investigation of speech act performance among non-native speakers of English. Educational Linguistics (University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education), 8, 33-53. Maros, M. (2006). Apologies in English by adult Malay speakers: Pat- terns and competence. The International Journal of Language, Soci- ety and Culture, 19, 1-14. Mey, J. L. (2001). Pragmatics: An introduction. Oxford: Blackwell. Mulamba, K. (2009). Social beliefs for the realization of the speech acts of apology and complaint as defined in Ciluba, French and English. Pragmatics, 19, 543-564. Nakano, M., Miyasaka, N., & Yamazaki, T. (2000). A study of EFL discourse using corpora: an analysis of discourse completion tasks. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 4, 273- 297. Nureddeen, F. A. (2008). Cross cultural pragmatics: Apology strategies in Sudanese Arabic. Journal of Pra g m at i cs , 40, 279-306.  E. MARZUKI, C. WALTER Open Access 303 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.11.001 Olshtain, E. (1989). Apologies across languages. In S. Blum-Kulka, J. House & G. Kasper (Eds.), Cross-cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies (pp.155-173). New Jersey: Ablex Publishing Corporation. Olshtain, E., & Cohen, A. (1983). Apology: A speech act set. In N. Wolfson, & E. Judd (Eds.), Sociolinguistics and language acquisi- tion (pp. 18-36). Rowley, MA: Newbury House. Park, H. S., Lee, H. E., & Song, J. A. (2005). “I am sorry to send you SPAM”. Cross-cultural differences in use of apologies in email ad- vertising in Korea and the U.S. Human Communication Research, 31, 365-398. Rose, K. R. (2000). An exploratory cross-sectional study of interlan- guage pragmatic development. Studies in Second Language Acquisi- tion, 22, 27-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100001029 Sabate i Dalmau, M., & Curell i Gotor, H. (2007). From “Sorry very much” to “I’m ever so sorry”: Acquisitional patterns in L2 apologies by Catalan learners of English. Intercultural Pragm a ti c s, 4, 287-315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/IP.2007.014 Scher, S. J., & Darley, J. M. (1996). How effective are the things peo- ple say to apologize? Effects of the realization of the apology speech act. Journal of Psycholinguistic R esearch, 26, 127-140. Shardakova, M. (2005). Intercultural pragmatics in the speech of American L2 learners of Russian: Apologies offered by Americans in Russian. Intercultural Pragmatics, 2, 423-451. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/iprg.2005.2.4.423 Shively, R. L., & Cohen, A. D. (2008). Development of apologies and requests during study abroad. Ikala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 13, 57-118. Sugimoto, N. (1997). A Japan-U.S. comparison of apology styles. Communication Research, 24, 349-369. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/009365097024004002 Supyan, H. (2006). The features in Malay SMS Texts. In L. S. Chin, & T. K. Hua (Eds.), Composing meanings: Media text and language (pp. 61-73). Bangi: UKM. Trosborg, A. (1995). Interlanguage pragmatics. Requests, complaints and apologies. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110885286 Warga, M., & Scholmberger, U. (2007). The acquisition of French apologetic behavior in a study abroad context. Intercultural Prag- matics, 4, 221-251. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/IP.2007.012 Wierzbicka, A. (1991). Cross-cultural pragmatics: The semantics of human interaction. New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Wierzbicka, A. (1996). Semantics: Primes and universals. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Woodfield, H. (2008). Problematising discourse completion tasks: Voices from verbal report. Evaluation and Research in Education, 21, 43-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.2167/eri413.0 Wouk, F. (2005). The language of apologizing in Lombok, Indonesia. Journal of Pragmatics, 38, 1457-1486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2005.09.011 Yang, T.-K. (2002). A study of Korean EFL learners’ apology speech acts: Strategy and pragmatic transfer influenced by sociolinguistic variations. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 6, 225-243. Zhang, H. (2001). Culture and apology: The Hainan Island incident. World Englishes, 20, 383-391. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-971X.00222  E. MARZUKI, C. WALTER Open Access 304 Appendix A Texts Sent to Participants English HR1: U were supposed to meet ur lecturer (female) at 2pm. However, u only remembered at 5pm. U called 2 apologise bt she was not in. Send an apology thru SMS. HR2: Ur supervisor (female) asked u to return a library book which she borrowed. U agreed to help bt forgot to return d book. A week later she sends a text msg/SMS inquiring whether the book has been returned. Reply to the text msg to apologise. LR3: U were supposed to meet a female cousin at 11am, but u only remembered around 2pm. U called but it was not answered. Apologise thru a text msg/SMS. LR4: U send an SMS from mobile to a friend, but when d reply comes back u realise tht u hv sent it to a stranger. Send an SMS to d person to apologise. Malay HR1: Anda membuat temujanji dgn seorg pensyarah perem- puan pd pkl 2 ptg, ttp hanya terigt pd pkl 5 ptg. Anda mnelefon pensyarah itu utk meminta maaf ttp dia tiada d pejabat. SMS pensyarah itu utk meminta maaf. HR2: Pensyarah penyelia anda (perempuan) mminta anda me- mulangkn buku ppustakaan yg dipinjam olehnya. Anda brsetuju utk mbantu ttp lupa utk memulangkn buku tsebut. Sminggu kmudian, dia mhantar SMS bertanyakn ttg buku itu. Bls SMS tsb utk mminta maaf. LR3: Anda bjanji dgn sepupu perempuan anda utk bjumpa pd pkl 11 pg, ttp anda hanya teringat janji itu pd pukul 2 ptg. Sepupu anda tidak mjawab pggilan telefon anda. Hantar SMS kpd sepupu anda utk meminta maaf. LR4: Anda mhantar mesej (SMS) kpd seorg rakan, ttp apabila anda mdapat balasan SMS tsebut, anda mdapati yg anda ter- salah hantar kpd org yg tidak dikenali. Hantar SMS utk mminta maaf. Appendix B Coding Scheme Sociopragmatic strategies Pragmalinguistic realisations and examples 1) Alerter 1a) greetings (hi, hello, hey, good morning, salam) 1b) formal address (Dr., Professor, Madam) 1c) name 1d) formal phrasing (Dear Mr., Dear Dr.) 1e) endearments (babe, love) 2) Illocutionary Force Indicating Device (IFID) 2) I’m sorry, I apologise, Please forgive me, Maaf 3) Taking responsibility (or attempts at minimising responsibility) 3a) explicit mention of offence (I forgot...Saya terlupa, Wrong number! ... salah hantar mesej) 3b) implicit mention of offence (It slipped my mind, ...tidak ingat, meant to send that to..., saya nak hantar kepada...) 3c) avoiding mentioning offence (I missed the meeting, …tidak menghadirkan diri...) 3d) explicit self-blame/reproach (My mistake, it was wrong of me ... kecuaian saya) 3e) earlier failed attempt at mitigating offence (I tried to call… I called but... Saya cuba call Puan) 3f) expression of embarrassment (I feel awful/bad) 3g) self-defence/validation (This is not me, I was busy with…saya sibuk dengan...) 3h) justify receiver’s reaction to offence (You must be mad at me... mesti marah kan) 3i) implicit self-blame/reproach (I should return it last week, sepatutnya saya buat minggu lepas... 4) Explanation/account 4) external, out-of-control circumstances which led to the offence (I was trapped in the elevator for 3 hours, my sister was involved in an accident, adahaltadi, ada org datang...) 5) Offer of repair 5a) compensatory offer directly related to offence (Could I arrange another appointment? Boleh buat temujanji lain?) 5b) additional compensatory offer directly related to offence, may explicitly take into account receiver’s con- venience (If it’s possible..., to your convenience, I’ll pay for the fines, Sekiranya tak menyusahkan...). 6) Promise to not repeat offence 6) (This will not happen again, I will be there, saya janji akan datang) 7) Distracting from offence 7a using humour (I must’ve been blind, ... nanti kene jual...) 7b appeaser (I will buy you dinner, aku belanja makan) 7c plea/request to receiver for something other than forgiveness (I hope you understand? Ignore the message, tolong abaikan) 8) Closing statement (both formal and informal–wish-like) 8a) complimentary close (Regards, Best wishes, Enjoy your weekend, Take care) 8b) sender’s name/initials 9) Thanking receiver 9) (Thanks, tq, Terima kasih) 10) Concern for receiver/show of empathy 10) (I know you’re busy, are u ok? ... buat puan tertunggu2, lama tak tunggu?) 11) Others Intensifiers of apology Red i) IFID internal intensifier Bold (very, truly, extremely, so, sangat, banyak2) ii) Emotional expression/exclamation Underlined (Whoops, OMG, Alamak)

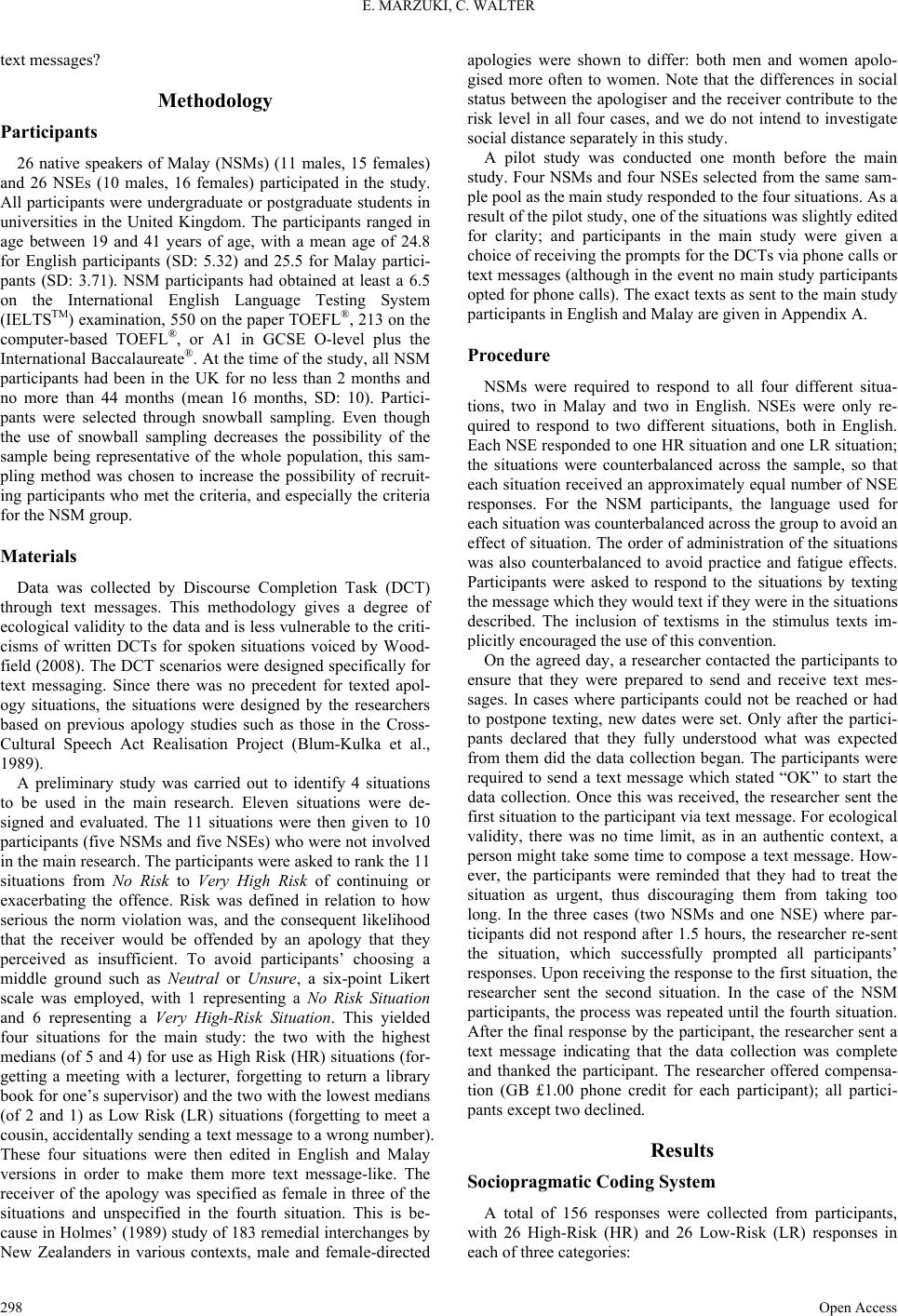

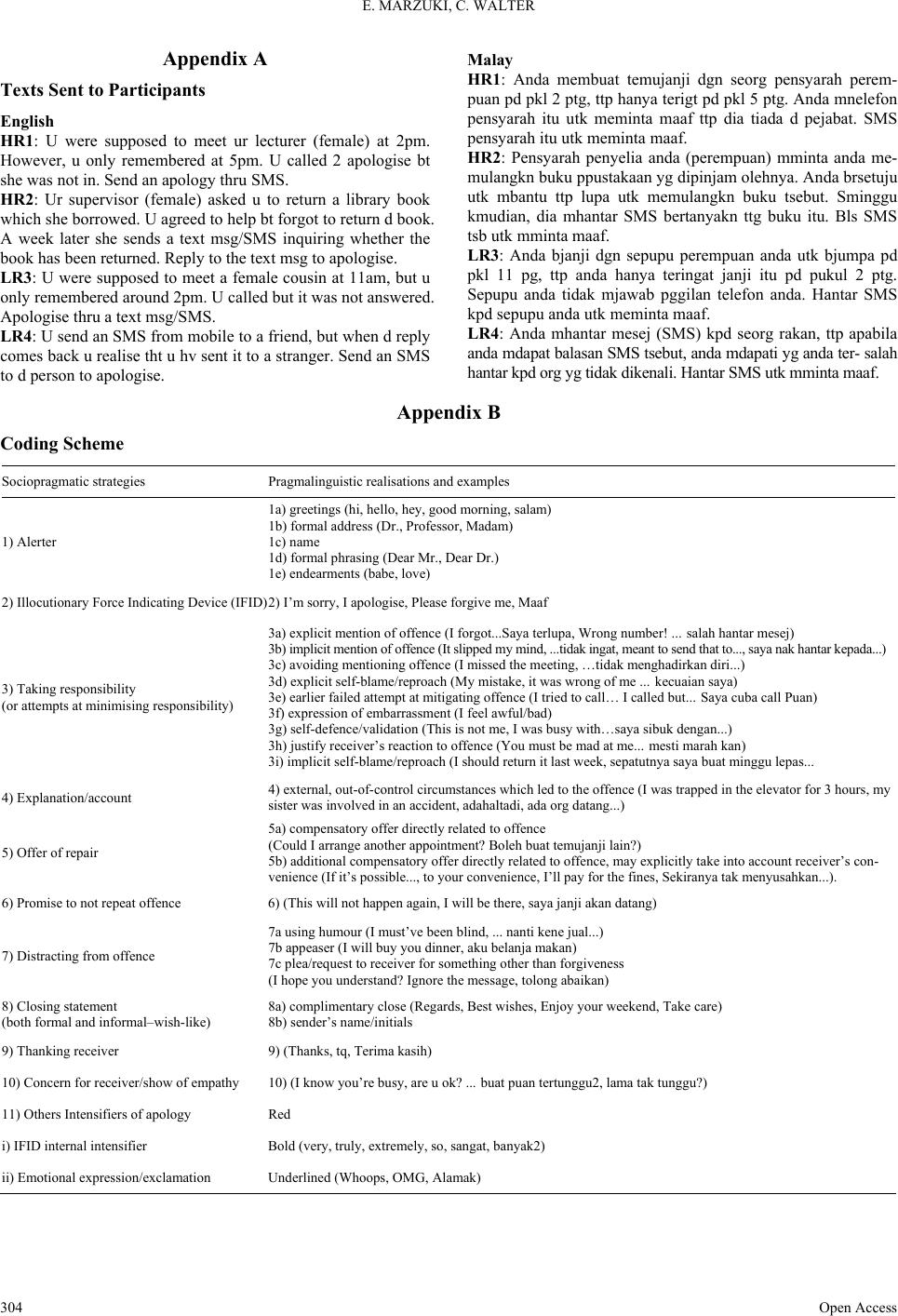

|