Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2013. Vol.3, No.4, 337-343 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2013.34043 Open Access 337 The Role of Religious Orientation, Psychological Well-Being, and Self-Esteem in Iranian EFL Learners’ Language Achievement Elham Moradi, Jahanbakhsh Langroudi Foreign Languages Department, Shahid Bahonar University, Kerman, Iran Email: elham.m.1988@gmail.com, jlangroudi@uk.ac.ir Received June 13th, 2013; revised July 14th, 2013; accepted July 23rd, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Elham Moradi, Jahanbakhsh Langroudi. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The present study aimed at finding the relationship of religious orientation (RO), psychological well-be- ing (PWB), and self-esteem (SE) with language achievement (LA) among Iranian EFL learners. Further- more, it investigated the predictability of dependent variable (LA) using all independent and predictor variables (RO, PWB, and SE). 126 senior and junior students majoring in English Translation and English Literature at Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman participated in the study. To obtain the required data, three questionnaires were utilized: Allport and Ross’s (1967) Intrinsic-Extrinsic Religious Orientation Scale (IEROS) to measure extrinsic and intrinsic religious orientations, Short Measurement of Psycho- logical Well-Being by Clarke, Marshall, Ryff, and Wheaton (2001) to measure psychological well-being, and finally, The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale by Rosenberg (1965) to assess self-esteem. Moreover, par- ticipants’ GPAs in major courses were used as indicators of their language achievement. For analysis of data, Pearson Product Moment Correlation and Regression analysis were used. The results revealed that there was a significant positive relationship between IRO, PWB, and SE with LA and a significant nega- tive relationship between ERO and LA. Additionally, all the independent variables together could predict LA and accounted for 95 percent of variability of students’ GPA. Keywords: Religious Orientation (RO); Extrinsic Religious Orientation (ERO); Intrinsic Religious Orientation (IRO); Psychological Well-Being (PWB); Self-Esteem (SE) Introduction Increasing interest toward language learning has made the parameters determining language achievement more signifi- cant. If effective and successful language learning is to be achieved, one solution would be Stevick’s (1980) claim about how successful language learning relies less on learning ma- terials, methods, tasks and language study and more on what is within and between learners and teachers. Many factors, internal and external to the learners, could affect their per- formance. This sheds more light on the significance of pa- rameters resulting in individual differences among learners. Rode et al. (2005) claimed that broader contextual and attitu- dinal variables might influence student’s achievement. Scho- lars, including psychologists, have conducted many research studies to identify the factors associated with academic per- formance, among which religious orientation (RO), psycho- logical well-being (PWB), and self-esteem (SE) have been found recognizably important (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furn- ham, 2005; Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Metzger, 2006; Stei- nberg & Morris, 2001). Religion has been reported to be effective in the daily functioning of the behavior (Shafranske, 1996) and it plays an important role in understanding a person’s psychological makeup (Maltby & Lewis, 1996). Moreover, religion has been shown to influence human decisions, choices, and ac- tions (Giddens, 2002) and to be significant in the develop- ment of competence and achievement (Hathaway & Parga- ment, 1990). A study by Astin and Astin (2004) showed that religious factors affect academic performance in college. Jeynes (2002) also reported that religious internalization and schooling are positively effective in academic achievement and also contribute to how one behaves in school. The well-being of college students has also been reported to be critical to their academic success. Those students with higher psychological well-being typically receive higher grades and are unlikely to experience academic failure (An- drews & Wilding, 2004; Daugherty & Lane, 1999; DeBerard, Speilmans, & Julka, 2004). Many studies have reported that university students’ psychological wellbeing is of paramount importance (El Ansari & Stock, 2010; Mikolajczyk et al., 2008). Self-esteem is perceived as a crucial factor in one’s social and cognitive development and is regarded as a predictor of academic performance (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003; Berndt, 2002; Peterson & Barrett, 1987; Peterson & Steen, 2002; Pulkkinen, Nygren, & Kokko, 2002; Wigfield, Battle, Keller, & Eccles, 2002). Researchers such as Coop- ersmith (1967) and Reasoner (1982) believed that a very im- portant trend in education has been shown to be a consideration of self-esteem. McCroskey, Daly, Richmond, and Falcione (1977) claim that both research and theory confirm that one’s perceptions of self have a significant effect on “… attitudes,  E. MORADI, J. LANGROUDI Open Access 338 behaviors, evaluations, and cognitive processes” (p. 269). They point out the important role that one’s self-concept plays in classroom research. The importance of self-esteem can be viewed in regard to learning generally and language learning specifically. Brown (2000) claimed that learner’s belief in her/his ability to accom- plish a task is central to all learning. Oxford and Ehrman (1995) also stated that learners’ positive/negative beliefs about them- selves and their learning ability definitely contribute to their success/failure in learning. Regarding the importance of self-esteem in the process of language learning specifically, Brown (1977) mentioned that a person with high self-esteem is able to act more freely and to be less reserved while learning a language. Such a person, because of his self strength, sees the indispensable mistakes in the proc- ess of learning not a threat to his identity and self. Religious Orientation It was since the time of Freud when the religious concept has been presented in the realm of psychology but psychology of religion has been studied empirically only since the mid fifties. From then on, psychologists began to acknowledge the crucial role of religion in “historical, cultural, social and psychological realities that humans confront in their lives” (Hood, Spilka, Hunsberger, & Gorsuch, 1996: p. 2). Early works on religiosity viewed it as a unidimensional concept (Freud, 1907; James, 1902; Jung, 1952; Pratt, 1920) and the ideas about it were reached only by the retrospective observation of isolated and extreme individuals, and were not supported empirically. But in the latter half of the twentieth century, the psychology of religion became a salient subject of study and developed by empirical evaluation. In all these studies religiosity as a multi- dimensional concept has its own dimensions and components (Hills, Francis, Argyle, & Jackson, 2004: pp. 62-63). Included here are the work of Fukuyama (1960) four dimensions, Lenski (1961) four dimensions, King (1967) ten dimensions, Allport’s intrinsic-extrinsic typology (Allport & Ross, 1967), and Glock’s (1972) five dimensional typology. Although some researchers such as Clayton and Gladden (1974) still argue against multi- dimensionality of religiosity, many others strongly support it (Faulkner & DeJong, 1966; Glock & Stark, 1965; King & Hunt, 1972a, 1972b, 1975; Lenski, 1961). As mentioned before, Allport (1959) introduced two dimen- sions for religiosity. At first, Allport (1950) called them “im- mature” and “mature”, but later on he used the terms “extrin- sic” and “intrinsic”, which are the focuses of the current study. To put the distinction in a nutshell, Allport and Ross (1967) stated that Extrinsics use their religion, while Intrinsics live their religion. Extrinsics see religion as a source of “security and solace, sociability and distraction, status and self justification” (Rodri- guez & Henderson, 2010: p. 85). For extrinsically oriented individuals, religion acts as a means to achieve some self- serving end. In contrast, individuals with intrinsic religious orientation view their needs and wants as of less significance and make them compatible with their own religious beliefs and directions. Intrinsics’ find their master motive in religion (Rodriguez & Henderson, 2010: p. 85). For the intrinsically inclined, religion itself is the eventual end and guideline of life (Allport, 1966). Psychological Well-Being Concept of well-being has long been under investigation since ancient Greece by philosophers such as Socrates, Plato and Aris- totle who attempted to define the essential constituents of positive human experience leading to the furtherance of pleasure and happiness. Aristotle, one of those philosophers, was the first one who mentioned two distinct dimensions of wellbeing (Ryan & Deci, 2001). In his view, well-being can be divided into two components; Hedonistic and Eudaimonic. Recently, hedonism is operationalized as subjective well-being (SWB), and eudaimon- ism as psychological well-being (PWB). Keyes, Shmotkin, and Ryff (2002) elaborate on the distinction between SWB and PWB and state although both evaluate well-being, they highlight different characteristics of well-being. “SWB involves more global evaluations of affect and life quality, whereas PWB examines perceived thriving vis-à-vis the existen- tial challenges of life” (Keyes et al., 2002: p. 1007). The second conceptualization of well-being is the focus of the current study. PWB pertains to a constructive and socially beneficial function- ing which leads to personal growth. In eudaimonism, well-being is a result of an endeavor for be- ing perfect which is to fulfill one’s true potential (Ryff, 1995: p. 100). In other words, happiness or well-being is a product of full engagement and optimal performance in existential challenges of life (Keyes et al., 2002). Ryan and Deci (2001) state that eudai- monim well-being constitutes the realization of one’s daimon or true nature. Ryff’s (1989b) psychological well-being model (PWB) was among the first to adopt the concept of eudaimonia. In his model, PWB includes six dimensions: Self-acceptance, Positive Rela- tions with Others, Autonomy, Environmental Mastery, Purpose in Life, and Personal Growth. Self-Esteem Self-esteem is one of those factors internal to the learner and crucial to the learning process. It is viewed as the image one forms of himself or the way he perceives himself. One’s self-esteem is determined by evaluation of that self (either negatively or positively). Self-esteem refers to the way indi- viduals assess their various capabilities and characteristics. Rubio (2007) describes self-esteem as “a psychological and social phenomenon” (p. 5) in which one assesses his/her com- petence and own self based on some principle. This evaluation may lead to various emotional states, and becomes growingly stable but still subject to change depending on personal condi- tions. Rosenberg’s (1965) definition of self-esteem is the most broad and frequently cited one which described it as a favorable or unfavorable attitude toward the self. Coopersmith (1967) described self esteem in this way: By self-esteem we refer to the evaluation which the individ- ual makes and customarily maintains with regard to himself; it expresses an attitude of approval or disapproval, and indicates the extent to which the individual believes himself to be capa- ble, significant, successful, and worthy (pp. 4-5). He added that self-esteem shows how a person judges his worthiness and what attitudes he has towards himself. Self- esteem as a subjective experience is conveyed by the individual to others through verbal and nonverbal behavior.  E. MORADI, J. LANGROUDI Open Access 339 Literature Review Religious Orientation and Language Achievement Researchers have found that religiosity is positively corre- lated with language achievement. For example, Hathaway and Pargament (1990), using a largely middle-aged sample, point out the important role that religiosity plays in the development of competence and achievement. Researchers have found that religiosity is positively correlated with grade point average (Walker & Dixon, 2002; Zern, 1989). Many other studies con- firm these findings (Abar, Carter, & Winsler, 2009; Brown, Ndubuisi, & Gary, 1990; Gary, 1990; Jeynes, 1999; Muller & Ellison, 2001; Trusty & Watts, 1999; Sikkink & Hernandez, 2003). Psychological Well-Being and Language Achievement Concept of well-being has been reported as critical to aca- demic success. Researches show that students with high sense of well-being receive better grades and are unlikely to drop out of college (Hysenbegasi, Hass, & Rowland, 2005; Pekrun, Goetz, Titz, & Perry, 2002). While some claim that more proficient people experience well-being during their life (Bowling & Windsor, 2001; Saun- ders, 1996), many others show the exact opposite (e.g. Tsou & Liu, 2001). Recently, lots of studies have detected that profi- ciency has a small and positive partial effect on well-being (Chow, 2005; Easterlin, 2001; Rode et al., 2005; Steinberg & Darling, 1994). Self-Esteem and Language Achievement A considerable amount of research has studied the role of self-esteem in the process of language learning and it has been found to be related to academic performance (Beane & Lipka, 1984; Chapman, 1988; Hansford & Hattie, 1982; Harter, 1983; Marsh, Byrne, & Shavelson, 1988; Wylie, 1979). Many studies show that Self-esteem influences achievement; and a positive correlation is found (Byrne, 1984; Covington, 1989; Klein & Keller, 1990; Solley & Stagner, 1956). Oxford and Ehrman (1995) asserted that learner’s positive beliefs about himself and his learning ability would definitely contribute to learning suc- cess. Conversely, other studies view self-esteem as the result of achievement (Calysn, 1971; Hoge, Smit, & Crist 1995; Ross & Broh, 2000; Schmidt & Padilla, 2003). Notably, Helmke and Van Aken (1995) acknowledge that academic achievement is more a cause of self-esteem than its outcome. However, some researchers report a negative or no correla- tion (Mecca, Smelser, & Vasconcellos, 1989). Baumeister et al. (2003) concluded that self-esteem has no relationship with subsequent achievement. Additionally, Crocker and Luhtanen (2003) reported that self-esteem cannot be a reliable predictor of academic achievement among college students. Methodology Participants The participants of this study were 126 male and female jun- ior and senior students majoring in English Literature and Eng- lish Translation at Shahid Bahonar university of Kerman. Ran- dom sampling was employed in the present study as in this procedure “all members of the population have an equal and independent chance of being included in the sample” (Ary, Jacobs, & Razavieh, 1972: p. 162). Instruments In order to obtain data on the variables, three questionnaires were administered: 1) Intrinsic-Extrinsic Religious Orientation Scale (IEROS, Allport & Ross, 1967). 2) Short Measurement of Psychological Well-Being (Clarke et al., 2001). 3) The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Intrinsic-Extrinsic Religious Orientation Scale (IEROS, Allport & Ross, 1967) Intrinsic-Extrinsic Religious Orientation Scale was devel- oped by Allport and Ross (1967). There are two distinctive subscales in this questionnaire, namely extrinsic orientation and intrinsic orientation. This instrument consists of 20 items and based on its original construction, nine items are related to in- trinsic and 11 items represent the extrinsic subscale. IEROS is based on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The separate summation of scale items yields score ranges of 11 - 55 and 9 - 45 for the extrinsic and intrinsic subscales, respectively. The Religious Orientation Scale has demonstrated good psy- chometric properties, with high internal consistency for both subscales (Hill & Hood, 1999). Hill and Hood (1999) noted that the intrinsic subscale has been found to be more internally con- sistent than the extrinsic, with α > 0.80 and α > 0.70, respec- tively. Validity and reliability in this self-report scale were acceptable by Taylor and Mac Donald (1999). Short Mea surement of Psy chological Wel l- Bei ng (Clarke et al., 20 01) PWB was operationalized with a short version (18 items, 3 for each construct) of Ryff’s (1989a) Measure of Psychological Well-being. Items are rated on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) Likert scale. The scale is presently regarded as the best objective measure of psychological well-being (Con- way & Macleod, 2002) and has received extensive cross-cul- tural validation (Staudinger, Baltes, & Fleeson, 1999). The combined scores can also provide an overall well-being total. Higher values for the whole scale correspond to higher levels of well-being, the values ranging between 18 and 126. Its validity and reliability were extensively measured and accepted in a study by Sirigatti et al. (2009). The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES, Rosenberg, 1965) Self-esteem was assessed by the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965), which is a 10-item self-report meas- ure of global self-esteem thereby providing good indication of general rather than specific views of the self (Baumeister et al., 2003). Each item is answered on a 4-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The scores can range from 10 (low level of self-esteem) to 40 (high level of self-esteem). The scale consists of five positively- worded and five negatively-worded items.  E. MORADI, J. LANGROUDI Open Access 340 The RSES has good levels of reliability and validity (Kong & You, 2011; Zhao, Kong, & Wang, 2012). The reliability index of the scale is α = 0.79. This scale has been used in vari- ous populations and has excellent reliability and validity (Bau- meister et al., 2003; Corcoran & Fischer, 1987). It “has re- ceived more psychometric analysis and empirical validation than any other self-esteem measure” (Robins, Hendin, & Trzesniewski, 2001: p. 151). Additionally, In order to evaluate the participants’ language achievement, their GPAs were used based on their major courses, not counting the general courses. Rolfhus and Acker- man (1999) have pointed out that grades represent a better pre- dictor of knowledge acquisition than any ability test. Therefore, they should be considered a variable and valid measure of po- tential achievement. Procedure The present study was carried out during the class time in the second semester of the academic year (2012). The question- naires for the measurement of RO, PWB, and SE were given to the subjects, simultaneously. During the completion process of the questionnaires, the researcher was present physically to monitor and also to provide the respondents with accompany- ing instructions whenever needed. Respondents were informed that the information they gave would be kept confidential and be used for research purposes only. Pearson Product Moment Correlation analysis was used to seek any meaningful relations between the independent vari- ables and dependent variable. Moreover, Regression Analysis was used to measure the predictability of LA using ERO, IRO, PWB, and SE. Results Descriptive Statistics of the Variables The descriptive statistics of the variables of the study, name- ly extrinsic and intrinsic orientations, psychological well-being, self-esteem, and language achievement (GPA) have been pre- sented in Table 1. In order to find any possible relationship between each of independent variables (ERO, IRO, PWB, and SE) and the de- pendent variable (GPA), Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient was conducted (Table 2). According to Table 2, there is a significant negative rela- tionship between ERO and LA (r = −.619). Concerning the relationship between IRO and GPA, a significant positive rela- tionship was found (r = .774). There is also a significant posi- tive relationship between PWB and GPA (r = .934). Finally, Table 1. The descriptive statistics of the variables. N Range Min Max Mean SD ERO 126 21 22 43 34.19 7.42 IRO 126 18 12 40 23.45 10.21 PWB 126 55 55 110 84.74 20.80 SE 126 23 14 37 24.63 8.76 GPA 126 6.02 13 19.02 16.56 2.13 Table 2. Correlations of the dependent variables and language achievement. ERO IRO PWB SE GPA Pearson Correlation−.619** .774** .934** .962** Sig. (2-tailed) .000 .000 .000 .000 N 126 126 126 126 Note: **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). concerning SE and GPA, a significant positive relationship was found (r = .962). In order to answer the second research question, concerning the predictability of GPA by using predictor variables (ERO, IRO, PWB, and SE), Regression Analysis was used. The regression variance analysis of GPA in relation with pre- dictor variables (Table 3) showed that R2 = .959 (R2 is the common variance between GPA and independent variables) and P = .000. Since R2 > 0and P < .05, the Multiple Linear Regression is significant. The R-squared is .959, meaning that approximately 95% of the variability of GPA is accounted for by all other variables. With regard to the linear relationship between the independ- ent variables and the dependent variable, the regression coeffi- cient for each variable of ERO, IRO, PWB, and SE has been presented in Table 3. The coefficients for each of the variables indicates the amount of change one could expect in GPA given a one-unit change in the value of that variable, given that all other variables in the model are held constant. For example, considering the variable SE, we would expect a decrease of .282 in the GPA score for every one unit increase in SE, assuming that all other variables in the model are held constant. In order to compare the strength of coefficient of one vari- able to the coefficient for another variable, we can refer to the column of Beta coefficients, also known as standardized re- gression coefficients. The beta coefficients are used to compare the relative strength of the various predictors. In a descending order, SE (β = .282), IRO (β = −.108), ERO (β = .052), and PWB (β = .018) have the largest to the smallest Beta coeffi- cients. Discussion The aim of the present study was to examine the relationship of extrinsic and intrinsic religious orientation, psychological well-being, and self-esteem with language achievement among EFL learners in Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients suggest that there are a negative relationship between ERO and LA and a positive significant relationship between IRO and LA. This can be explained by the fact that Intrinsics may benefit from ex- periencing less academic stress and better well-being while attending college. So they can perform better academically in comparison with extrinsic counterparts. Along the same way, Jeynes (2003) found that urban high school students reporting high religiosity achieved higher performance on standardized academic measures. This is in line with findings by Lehrer (1999), Regenerus and Elder (2003), and Loury (2004). Moreover, a positive significant relationship between PWB  E. MORADI, J. LANGROUDI Open Access 341 Table 3. Regression analysis for GPA using each of the predictor variables. Unstandardized Coefficients B Std. Error Standardized Coefficientst Sig. F P R R2 Constant 12.017 .926 - 12.974 .000 ERO −.041 .021 −.142 −1.960 .052 IRO −.108 .020 −.515 −5.425 .000 PWB .018 .007 .170 2.717 .008 SE .282 .019 1.156 14.628 .000 716.059 .000 .980 .959 and LA was found. Findings by Gilman and Huebner (2006), Quinn and Duckworth (2007), Yasin and Dzulkifli (2009), and Yasin and Dzulkifli (2009) support the importance of psycho- logical well-being in academic achievement. Concerning the relationship between SE and LA, a positive relationship was found. Many studies confirm this finding (Aryana, 2010; Heyde, 1979; Oxford & Ehrman, 1993). Rastegar (2002, 2003) in two separate studies on Iranian EFL students found a substantial relationship between global or trait self- esteem and FL achievement. The Multiple Regression also suggested that ERO, IRO, PWB, and SE account for unique variance in higher GPA. On the whole, all the independent together variables explained 95 percent of variability of students’ GPA. REFERENCES Abar, B., Carter, K. L., & Winsler, A. (2009). The effects of maternal parenting style and religious commitment on self-regulation, aca- demic achievement, and risk behavior among African-American pa- rochial college students. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 259-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.03.008 Allport, G. W. (1950). The individual and his religion: A psychological interpretation. New York: Macmillan. Allport, G. W. (1959). Religion and prejudice. Crane Review, 2, 1-10. Allport, G. W. (1966). The religious context of prejudice. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 5, 447-457. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1384172 Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality an d Social Psychology, 5, 432-443. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0021212 Andrews, B., & Wilding, J. M. (2004). The relation of depression and anxiety to life-stress and achievement in students. British Journal of Psychology, 95, 509-521. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/0007126042369802 Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., & Razavieh, A. (1999). Introduction to research in education. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. Aryana, M. (2010). Relationship between self-esteem and academic achievement amongst pre-university students. Journal of Applied Sciences, 10, 2474-2477. http://dx.doi.org/10.3923/jas.2010.2474.2477 Astin, A. W., & Astin, H. (2004). A research report on spirituality development and the college experience. Los Angeles, CA: Univer- sity of California, Higher Education Research Institute. Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal suc- cess, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1-44. Beane, J. A., & Lipka, R. P. (1984). Self-Concept, self-esteem, and the curriculum. Newton: Allyn and Bacon. Berndt, T. J. (2002). Friendship quality and social development. Cur- rent Directions in Psychological Science, 11, 7-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00157 Bowling, A., & Windsor, J. (2001). Towards the good life: A popula- tion survey of dimensions of quality of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 55-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1011564713657 Brown, D. R. (1977). Introduction to snow and Ferguson. In C. Snow and C. Ferguson (Eds.), Talking to children (pp. 1-27). New York: Cambridge University Press. Brown, D. R., Ndubuisi, S. C., & Gary, L. E. (1990). Religiosity and psychological distress among blacks. Journal of Religion and Health, 29, 55-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00987095 Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Byrne, B. (1984). The general/academic self-concept nomological net- work: A review of construct validation research. Review of Educa- tional Research, 54, 427-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543054003427 Calsyn, R. J. (1971). The causal relation between self-esteem, locus of control, and achievement: Cross-lagged panel analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Evanston, IL: Northwestern University. Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2005). Personality and intel- lectual competence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence-Erlbaum Associates. Chapman, J. W. (1988). Learning disabled children’s self-concept. Re- view of Educational Research, 58, 347-371. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543058003347 Chow, H. P. H. (2005). Life satisfaction among university students in a Canadian prairie city: A multivariate analysis. Social Indicators Re- search, 70, 139-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-7526-0 Clarke, P. J., Marshall, V. M., Ryff, C. D., & Wheaton, B. (2001). Measuring psychological well-being in the Canadian study of health and aging. International Psychogeriatrics, 13, 79-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1041610202008013 Clayton, R. R., & Gladden, J. W. (1974). The Five dimensions of re- ligiosity: Toward demythologizing a sacred artifact. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 13, 135-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1384375 Coopersmith, S. (1967). The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman. Conway, C., & Mac1eod, A. (2002). Well-being: It’s importance in clinical research. Clinical P sycho logy, 16, 26-29. Corcoran, K., & Fischer, J. (1987). Measures for clinical practice: A sourcebook. New York: The Free Press. Covington, M. V. (1989). Self-esteem and failure in school. The social importance of self-esteem. Berkeley, CA: University of Cambridge Press. Crocker, J., & Luhtanen, R. K. (2003). Level of self-esteem and con- tingencies of self-worth: Unique effects on academic, social, and fi- nancial problems in college students. Personality and Social Psy- chology Bulletin, 29, 701-712. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167203029006003 Daugherty, T. K., & Lane, E. J. (1999). A longitudinal study of aca- demic and social predictors of college attrition. Social Behavior and Personality, 27, 355-362. http://dx.doi.org/10.2224/sbp.1999.27.4.355  E. MORADI, J. LANGROUDI Open Access 342 DeBerard, M. S., Speilmans, G. I., & Julka, D. C. (2004). Predictors of academic achievement and retention among college freshman: A longitudinal study. College Studen t J ou r n al , 38, 66-80. Donahue, M. J. (1985). Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 400-419. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.2.400 El Ansari, W., & Stock, C. (2010). Is the health and wellbeing of uni- versity students associated with their academic performance? Cross sectional findings from the United Kingdom. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 7, 509-527. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7020509 Faulkner, J. E., & DeJong, G. (1966). Religiosity in 5-D: An empirical analysis. Social Forces, 45, 246-254. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2574395 Freud, S. (1907). Obsessive acts and religious practices. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete works of Sigmund Freud. London: Hogarth Press. Fukuyama, Y. (1960). The major dimensions of church membership. Review of Religious Research, 2, 154-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3510955 Giddens, A. (2000). Runaway world: How globalisation is reshaping our lives. London: Routledge. Gilman, R., & Huebner, E.S. (2006). Characteristics of adolescents who report very high life satisfaction. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 293-301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9036-7 Glock, C. Y. (1972). On the study of religious commitment. In J. E. Faulkner (Ed.), Religion’s influence in contemporary society, read- ings in the sociology of religion (pp. 38-56). Marietta, OH: Charles E. Merril. Glock, C. Y., & Stark. R. (1965). Religion and society in tension. Chi- cago: Rand McNally. Hansford, B. C., & Hattie, J. A. (1982). The relationship between self and achievement/performance measures. Review of Educational Re- search, 52, 123-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543052001123 Harter, S. (1983). Developmental perspectives on the self-system. In E. M. Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 275-385). New York: John Wiley. Hathaway, W. L., & Pargament, K. I. (1990). Intrinsic religiousness, religious coping and psychosocial competence: A covariance struc- ture analysis. Journal fo r the Scientific S tudy of Religion, 29, 423-441. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1387310 Helmke, A., & Van Aken, M. A. G. (1995). The causal ordering of academic achievement and self-concept of ability during elementary school: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87, 624-637. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.4.624 Heyde, A. (1979). The relationship between self-esteem and the oral production of a second language. Ph.D. Thesis, Michigan: Univer- sity of Michigan. Hill, P. C., & Hood, R. W. (1999). Measures of religiosity. Birmingham, Alabama: Religious Education Press. Hills, P., Francis, L. J., Argyle, M., & Jackson, C. J. (2004). Primary personality trait correlates of religious practice and orientation. Per- sonality and Individual Diffe r en c e s, 36 , 61-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00051-5 Hoge, D. R., Smit, E. K., & Crist, T. J. (1995). Reciprocal effects of self-concept and academic achievement in sixth and seventh grade. Journal of Youth a n d Adolescence, 24, 295-314. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01537598 Hood Jr., R. W., Spilka, B., Hunsberger, B., & Gorsuch, L. (1996). The psychology of religion: An empirical approach (2nd ed.). New York Guilford Press. Hysenbegasi, A., Hass, S. L., & Rowland, C. R. (2005). The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 8, 145-151. James, W. (1902). The varieties of religious experience. New York: Longman. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10004-000 Jeynes, W. H. (1999). The effects of religious commitment on the aca- demic achievement of Black and Hispanic children. Urban Educa- tion, 34, 458-479. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0042085999344003 Jeynes, W. H. (2002). Why religious schools positively impact the academic achievement of children. International Journal of Educa- tion and Religion, 3, 16-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/157006202760182418 Jeynes, W. H. (2003). The effects of religious commitment on the aca- demic achievement of urban and other children. Education and Ur- ban Society, 36, 44-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0013124503257206 Jung, C. G. (1952). Symbols of transformation: an analysis of the prel- ude to a case of schizophrenia. In H. Read, M. Fordham, & G. Adler (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 1007-1022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007 King, M. (1967). Measuring the religious variable: Nine proposed di- mensions. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 6, 173-185. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1384044 King, M. B., & Hunt, R. A. (1972a). Measuring religious dimensions: Studies in congregational involvement. Dallas: Southern Methodist University. King, M. B., & Hunt, R.A. (1972b). Measuring the religious variable: Replication. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 11, 240-251. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1384548 King, M. B., & Hunt, R. A. (1975). Measuring the religious variable: National replication. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 14, 13-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1384452 Klein, J. D., & Keller, J. M. (1990). Influence of student ability, locus of control, and type of instructional control on performance and con- fidence. Journal of Educational Research, 83, 140-146. Kong, F., & You, X. (2011). Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. So- cial Indicators Research, 110, 271-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9930-6 Lehrer, E. L. (1999). Religion as a determinant of educational attain- ment: An economic perspective. Social Science Research, 28, 358- 379. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/ssre.1998.0642 Lenski, G. E. (1961). The religious factor. New York: Doubleday. Loury, L. (2004). Does church attendance really increase schooling? Journal for the Scientific S tu d y o f R e ligion, 43 , 119-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2004.00221.x Marsh, H. W., Byrne, B., & Shavelson, R. J. (1988). A multifaceted academic self-concept. Its’ hierarchical structure and its’ relation to academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 366- 380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.3.366 McCroskey, J. C., Daly, J. A., Richmond, V. P., & Falcione, R. L. (1977). Studies of the relationship between communication apprehend- sion and self-esteem. Human Communication Research, 3, 269-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1977.tb00525.x Mecca, A. M., Smelser, N. S., & Vasconcellos, J. (1989). The social importance of self-esteem. Berkeley: University of California Press. Mikolajczyk, R. T., Maxwell, A. E., Naydenova, V., Meier, S., & El Ansari, W. (2008). Depressive symptoms and perceived burdens re- lated to being a student: Survey in three European countries. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 4, 19. Muller, C., & Ellison, C. G. (2001). Religious involvement, social ca- pital, and adolescents’ academic progress: Evidence from the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988. Sociological Focus, 34, 155- 183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2001.10571189 Oxford, R. L., & Ehrman, M. (1995). Cognition plus: Correlates of language learning success. The Modern Language Journal, 79, 67-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb05417.x Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emo- tions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A pro- gram of quantitative and qualitative research. Educational Psycholo- gist, 37, 91-105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4 Peterson, C., & Barrett, L. C. (1987). Explanatory style and academic performance among university freshmen. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 53, 603-607. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.603 Peterson, C., & Steen, T. A. (2002). Optimistic explanatory style. In C. R. Snyder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology  E. MORADI, J. LANGROUDI Open Access 343 (pp. 244-256). New York: Oxford University Press. Pratt, J. B. (1920). The religious consciousness. New York: Macmillan. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10884-000 Pulkkinen, L., Nygren, H., & Kokko, K. (2002). Successful develop- ment: Childhood antecedents of adaptive psychosocial functioning in adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 9, 251-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1020234926608 Quinn, P. D., & Duckworth, A. L. (2007). Happiness and academic achievement: Evidence for reciprocal causality. In The Annual Meet- ing of the American Psychological Society, Washington, DC: The American Psychological Society. Rastegar, M. (2002).The effect of self-esteem, extroversion and risk- taking on EFL proficiency of TEFL students. Journal of Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, 10, 9-35. Rastegar, M. (2003). Affective, cognitive, and personality predictors of foreign language proficiency among Iranian EFL learners. Ph.D. Thesis, Shiraz: Shiraz University. Reasoner, R. (1982). Building self-esteem: A comprehensive program for schools. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc. Regenerus, M., & Elder, G. (2003). Staying on track in school: Reli- gious influences in high- and low-risk settings. Journal for the Scien- tific Study of Religion, 42, 633-659. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-5906.2003.00208.x Robinson, J. P., & Shaver, P. R. (1973). Measures of social psycho- logical attitudes. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research. Robins, R. W., Hendin, H. M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Measur- ing global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psy- chology Bulletin, 27, 151-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167201272002 Rode, J. C., Arthaud-Day, M. L., Mooney, C. H., Near, J. P., Baldwin, T. T., Bommer, W. H., & Rubin, R. S. (2005). Life satisfaction and student performance. Academy of Management Learning & Educa- tion, 4, 421-433. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2005.19086784 Rodriguez, C. M., & Henderson, R. C. (2010). Who spares the Rod? Religious orientation, social conformity, and child abuse potential. Child Abuse and Neglec t , 34, 84-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.002 Rolfhus, E. L., & Ackerman, P. L. (1999). Assessing individual differ- ences in knowledge: Knowledge structures and traits. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 511-526. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.3.511 Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Ross, C. E., & Broh, B. A. (2000).The roles of self-esteem and the sense of personal control in the academic achievement process. Soci- ology of Education, 73, 270-284. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2673234 Rubio, F. (2007). Self-Esteem and Foreign Language Learning: An introduction. In F. Rubio (Ed.), Self-esteem and foreign language learning (pp. 2-12). Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141-166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141 Ryff, C. D. (1989a). Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful ageing. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12, 35-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/016502548901200102 Ryff, C. D. (1989b). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069-1081. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 Ryff, C. D. (1995). Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Di- rections in Psychological Science, 4, 99-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772395 Saunders, P. (1996). Income, health and happiness. The Australian Economic Review, 29, 353-366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8462.1996.tb00941.x Schmidt, J. A., & Padilla, B. (2003). Self-esteem and family challenge: an investigation of their effects on achievement. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 32, 37-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1021080323230 Shafranske, E. P. (1996). Religion and the clinical practice of psychol- ogy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10199-000 Sikkink, D., & Hernandez, E. (2003). An interim report on religion matters: Predicting schooling success among Latino youth. Notre Dame, IN: Institute for Latino Studies, University of Notre Dame. Sirigatti, S., Stefanile, C., Giannetti, E., Iani, L., Penzo, I., & Mazzeschi, A. (2009). Assessment of factor structure of Ryff’s psychological well-being scales in Italian adolescents. Bollettino Di Psicologia Ap- plicata, 259, 30-50. Smetana, J. G., Campione-Barr, N., & Metzger, A. (2006). Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 255-284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124 Solley, C. M., & Stagner, R. (1956). Effect of magnitude of temporal barriers, types of perception of self. Journal of Experimental Psy- chology, 51, 62-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0049139 Staudinger, V. M., Baltes, P. B., & Fleeson, W. (1999). Predictors of subjective physical health and global well-being: Similarities and dif- ferences between the United States and Germany. Journal of Per- sonality and Social Psychology, 76, 305-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.2.305 Steinberg, L., & Darling, N. (1994). The broader context of social in- fluence in adolescence. In R. K. Silbereisen, & E. Todt (Eds.), Ado- lescence in context: The interplay of family, school, peers, and work in adjustment. New York: Springer-Verlag, Inc. Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83 Stevick, E. W. (1980). Teaching languages: A way and ways. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. Taylor, A., & McDonald, D. A. (1999). Religion and five factor model of personality: An exploratory investigation using a Canadian univer- sity sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 1243-1259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00068-9 Trusty, J., & Watts, R. E. (1999). Relationship of high school seniors’ religious perceptions and behavior to educational, career and leisure variables. Counseling and V alues , 44, 30-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.1999.tb00150.x Tsou, M. W., & Liu, J. T. (2001). Happiness and domain satisfaction in Taiwan. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 269-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1011816429264 Walker, K., & Dixon, V. (1989). Spirituality and academic performance among African American college students. Journal of Black Psy- chology, 28, 107-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0095798402028002003 Wigfield, A., Battle, A., Keller, L. B., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). Sex dif- ferences in motivation, self-concept, career aspiration and career choice: Implications for cognitive development. In A. V. McGillicuddy-De Lisi, & R. De Lisi (Eds.), Biology, society, and behavior: The devel- opment of sex differences in cognition (pp. 93-124). Greenwich, CT: Ablex. Wylie, R. C. (1974). The self-concept: A review of methodological con- siderations and measuring instruments. Lincoln, NE: University of Ne- braska Press. Yasin, M. A. S. M., & Dzulkifli, M. A. (2011). Differences in depress- sion, anxiety and stress between low-and high-achieving students. Journal of Sustainability Science a nd Management, 6, 169-178. Zern, D. (1989). Some connections between increasing religiousness and academic accomplishment in a college population. Adolescence, 24, 141-154. Zhao, J. J., Kong, F., & Wang, Y. H. (2012). Self-Esteem and humor style as mediators of the effects of shyness on loneliness among Chinese college students. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 686-690. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.024

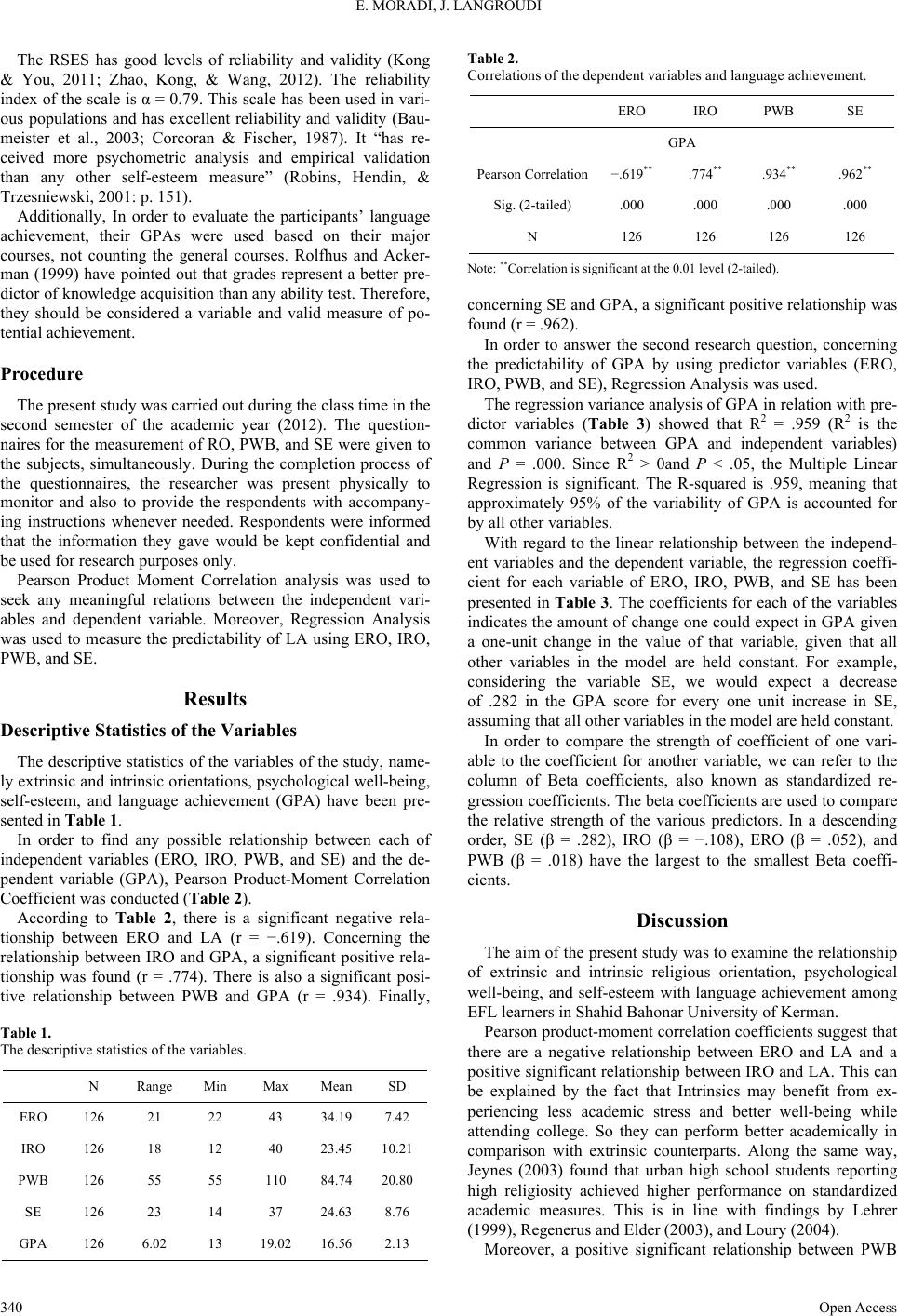

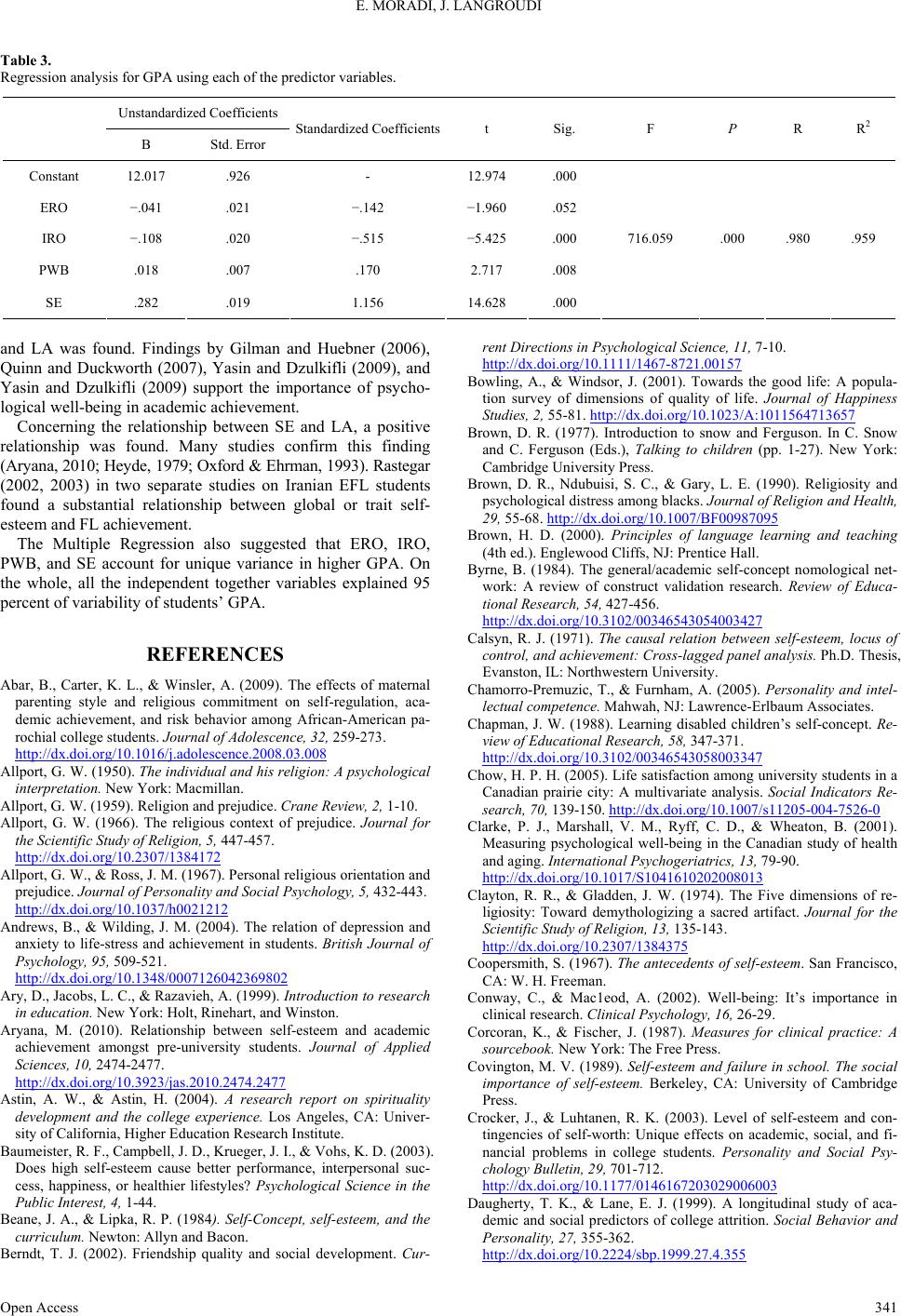

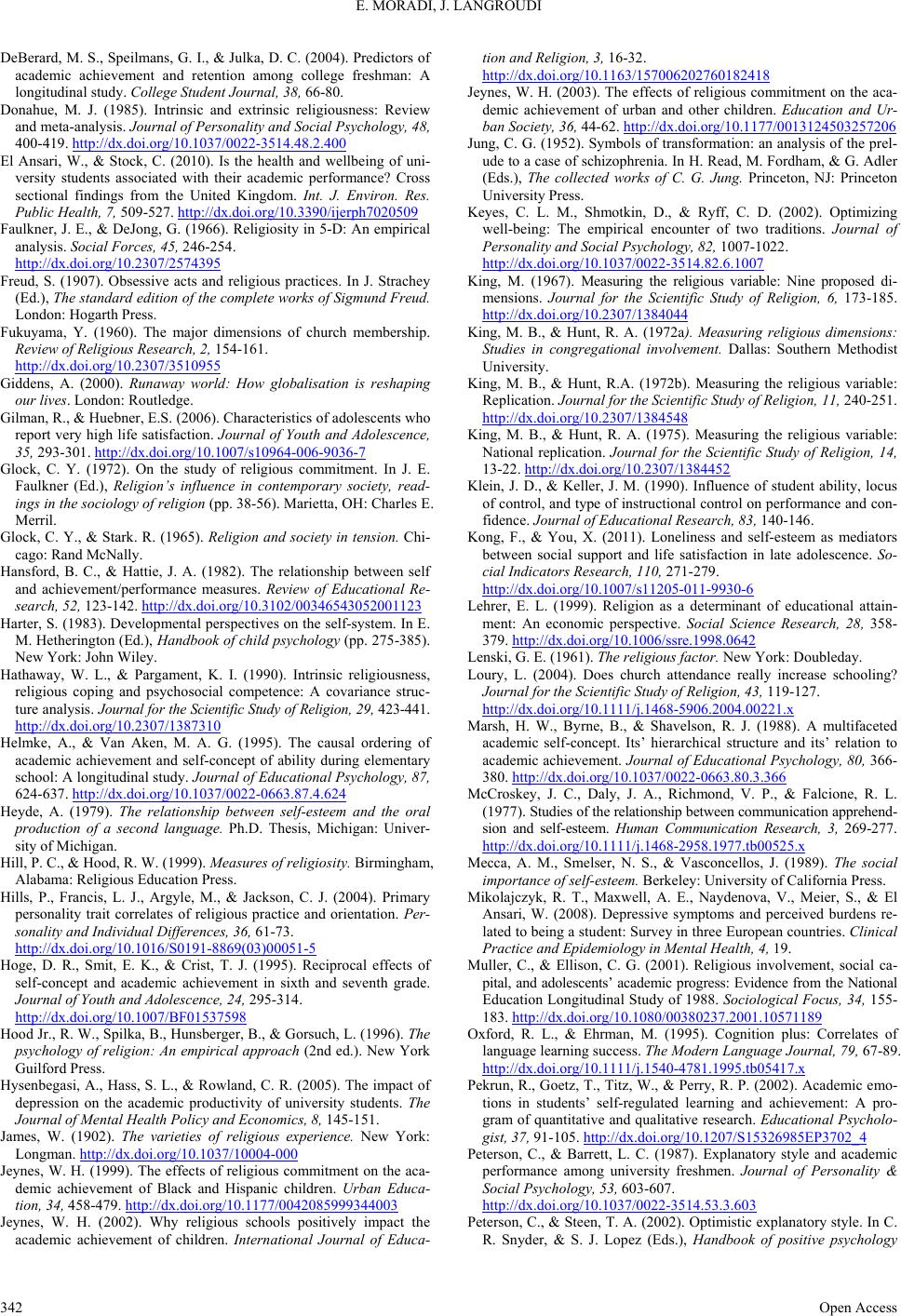

|