Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

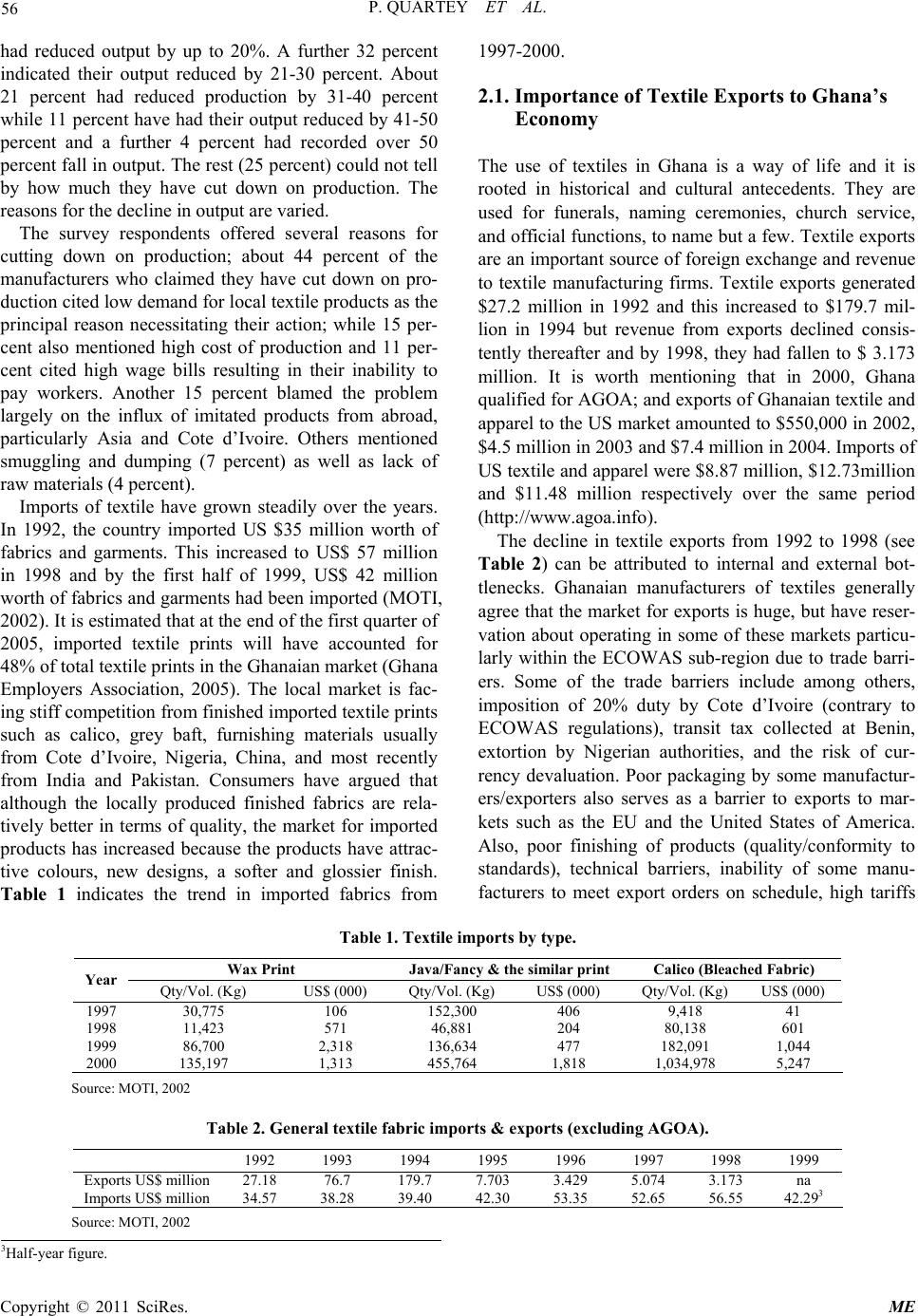

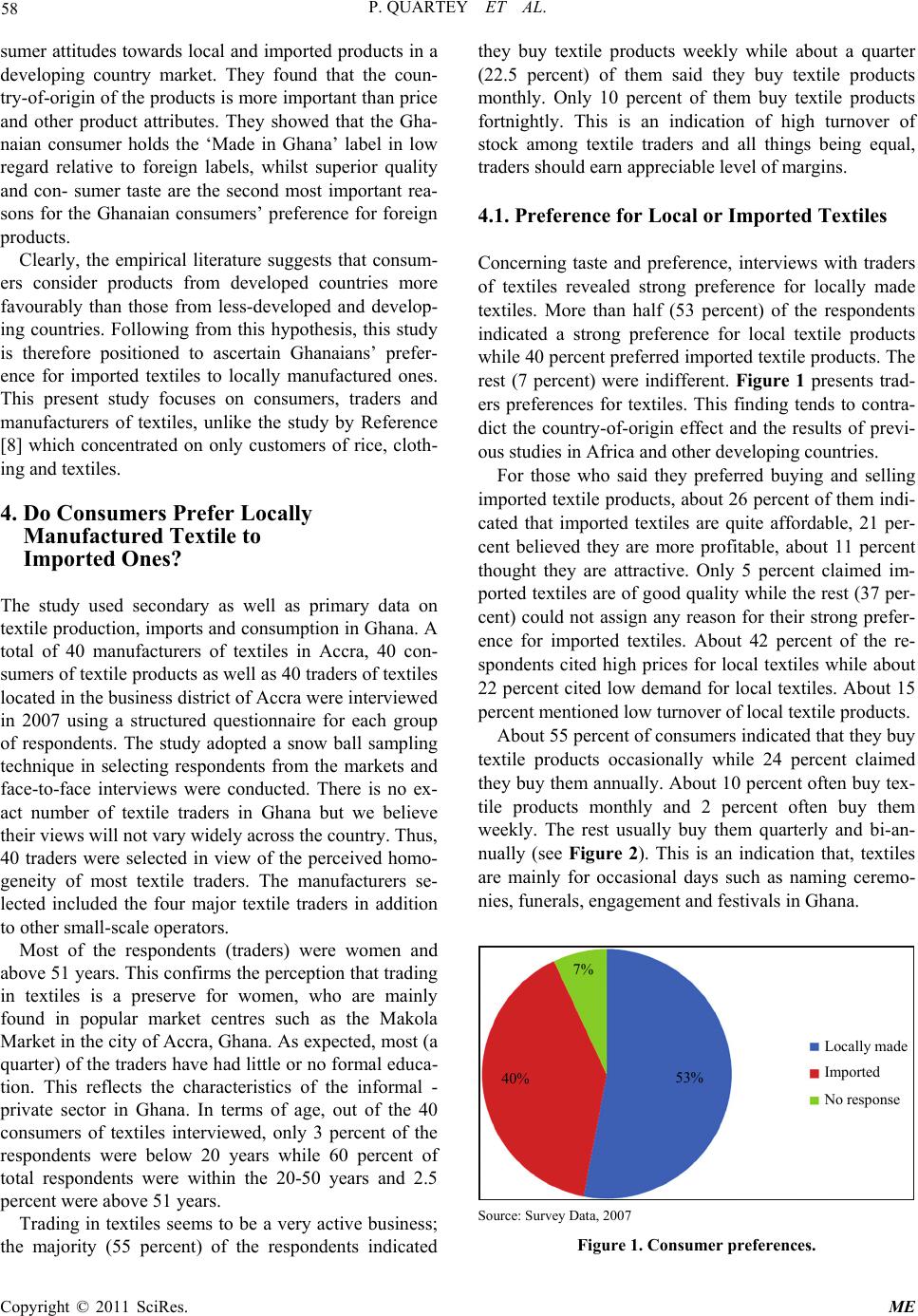

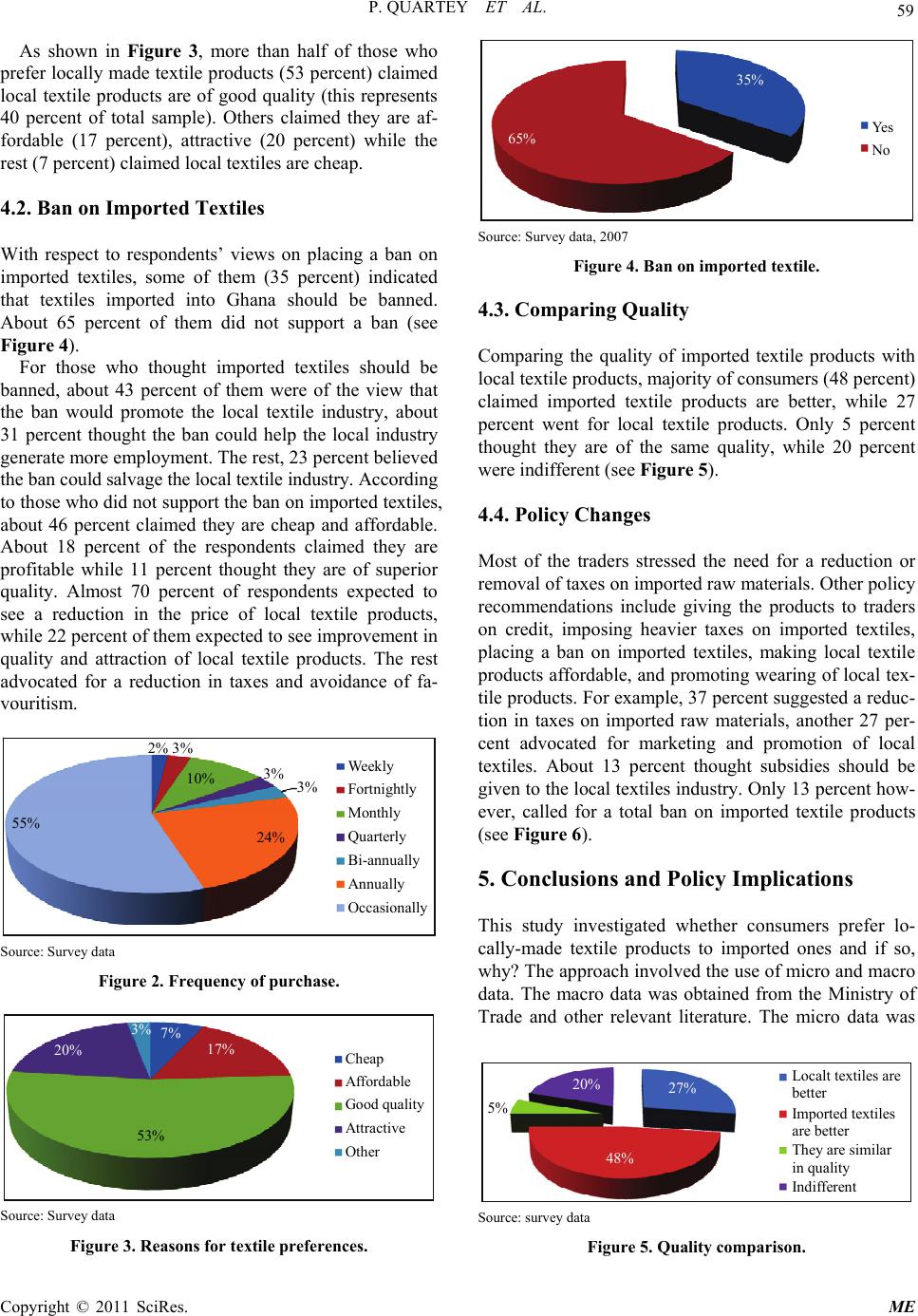

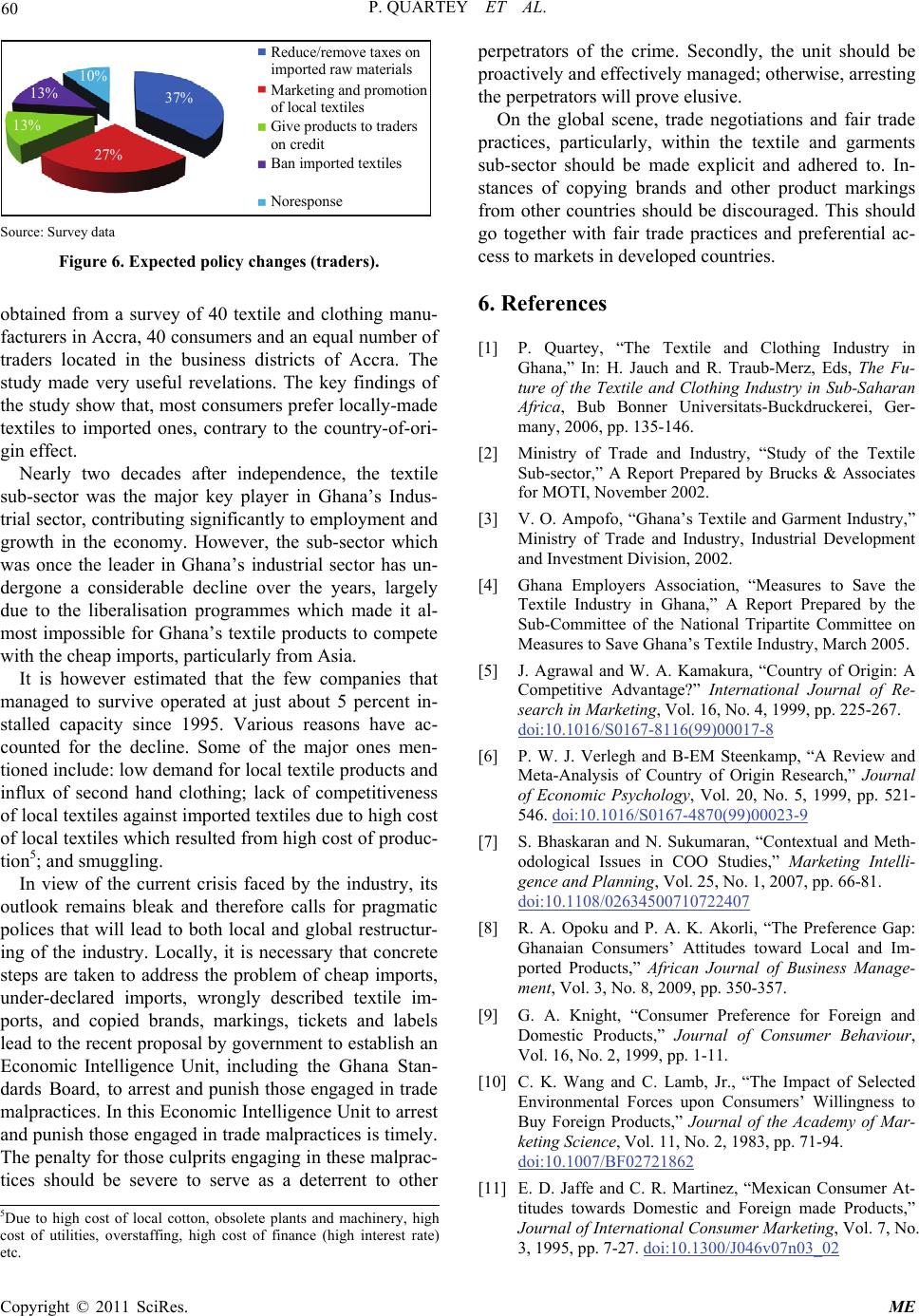

Modern Economy, 2011, 2, 54-61 doi:10.4236/me.2011.21009 Published Online February 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME Do Ghanaians Prefer Imported Textiles to Locally Manufactured Ones?* Peter Quartey1, Joshua Abor2 1Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana 2Department of Finance, University of Ghana Business School, Legon, Ghana E-mail: pquartey@ug.edu.gh Received October 2, 2010; revised October 20, 2010; accepted October 26, 2010 Abstract This paper ascertains whether consumers prefer locally made textile to imported ones or vice versa and what accounts for the choice. The study uses survey data of industry, traders and consumers to explain the issue. The results show that most consumers prefer locally-made textiles to imported ones. More than half of those who prefer locally-made textiles claimed local textile products are of a better quality. Others claimed they are more affordable and attractive while a few claimed local textiles are cheaper. This appears to contradict the country-of-origin effect and the results of previous studies in Africa and other developing countries. Im- plications for traders, governments and local manufacturers are also discussed. The study provides insights with respect to Ghanaians’ preference of locally-produced textiles to foreign-made ones. Keywords: Country-of-Origin, Imports, Ghana 1. Introduction Ghana’s current trade policy, which aims at promoting accelerated economic development and reducing poverty, supports two parallel strategies, namely, export-led in- dustrialization and domestic market-led industrialization based on import competition. The success of both stra- tegies depends on the competitiveness of local producers in both the domestic and international markets. For some years now, import competing industries have been facing a number of challenges which are alleged to have inhib- ited their growth [1]. The key factors usually noted as being responsible for aggravating the situation have in- cluded the inflow of un-customed goods through unfair trading practices, infringement on intellectual property rights and the importation of imitation products that may usually carry lower prices to mention but a few. Local manufacturers of textiles in particular, are those signifi- cantly affected by these developments. For instance, while in the mid 1970’s, the textile in- dustry’s production capacity was approximately 130 mil- lion metres and employed about 25,000 workers; by 2002, production capacity and employment levels had dropped to 36 million metres and 2,000 workers respec- tively [2]. In some African countries where this has hap- pened, governments have responded to reverse the de- clining trend. For instance, the Federal Government of Nigeria in September 2002 took various drastic measures which included a total ban on importation of all finished textiles in order to assist the Nigerian Textile Industry and save it from total collapse. Thus, while the textile industries in Nigeria enjoy duty incentive of 10%, ex- port expansion grant of 30% and; 0% Value Added Tax (VAT) and National Health Insurance Levy (NHIL), Ghanaian industries have no duty incentives and export expansion grant, but rather are made to pay a 12.5% VAT and 2.5% NHIL on their finished products, thereby, making Ghana’s products more expensive. The limited incentive structure has led to unemploy- ment, loss of government revenue and loss of access to the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). Local producers of textiles have identified some ‘safeguard op- tions’ in the World Trade Organization (WTO) stipula- tions such as Bi-lateral negotiations to limit exports, emergency measures to limit imports and countervailing duty which Ghana can take advantage of. Stakeholders have advocated for certain measures to revive the textiles sector, namely, removal of duty on inputs for the produc- tion process; increase in duty on finished fabrics im- ported; proper collection of duties and taxes on imports; *This study was funded partially by the Think Tank Initiative (TTI) Core Grant provided by IDRC to ISSER.  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 55 seizure of goods which are found to be undervalued, misrepresented, pirated, copied or sub-standard. Ironi- cally, while the job losses continue and stakeholders continue to advocate for a ban on imported textile, Gha- naians continue to patronize imported textile products. One may therefore ask, why do Ghanaians continue to import these products at the expense of local substitutes? Could price or quality be a factor? These issues remain the focus of investigation in this report. This paper uses survey data of industry, traders and consumers to explain whether consumers prefer locally made textile to imported ones or vice versa and what accounts for the choice. The rest of the paper is organ- ized as follows: section two presents the stylized facts on the textile and clothing industry in Ghana. The third sec- tion provides a brief overview of extant literature. Sec- tion four discusses the research findings in terms of whether Ghanaians prefer locally made textile products to imported ones and if so what were the major reasons. The final section provides concluding remarks and draws the policy implications of the study. 2. The Textile Industry in Ghana As at mid 1970’s, about 16 large1 and medium sized tex- tile companies had been established in Ghana. The gar- ment industry also had some 138 medium and large-scale garment manufacturing companies during that time. However, inconsistent government policies over the years have contributed greatly to the decline in the sub- sector’s activity levels. As at 2002, the four major com- panies that survived the turbulence in the sub-sector were the Ghana Textile Manufacturing Company (GTMC), Akosombo Textile Limited (ATL), Ghana Textile Prod- uct (GTP), and Printex with GTP maintaining the lead in the industry. The garment industry comprised of numer- ous small-scale enterprises which took the form of sole proprietorship and were engaged in making garments for individuals as well as uniforms for schools, industries and governmental institutions such as the police, the army, hospitals, etc, and also for the exports market. The garment industry however, depended directly on the tex- tile industry. Investments within the textile industry were mainly by local firms. A survey of 40 textile and garment industries within Accra-Tema revealed that only 5% of these firms were involved in joint ventures with foreign investors. The rest (95 percent) were locally-owned and none was solely foreign owned. Ghana’s textile industry employed about 25,000 peo- ple and accounted for 27 percent of total manufacturing employment in 1977. However, by 1995 employment within the sub-sector declined to a mere 7,000 and de- clined further to 5000 by the year 2000 [3]. The declin- ing trend has not changed and employment continues to decline. As at March 2005, the four major textile compa- nies in Ghana employed a mere 2961 persons [4]. A sur- vey of 40 textile and garments industries in 2007 also confirmed that the situation is getting worse2. Ghana’s textile industry is mainly concerned with the production of fabrics for use by the garment industry and also for the export market. The sub-sector is predomi- nantly cotton-based although the production of man- made fibres is also undertaken on a small scale. The main cotton-based textile products include: African prints (wax, java, fancy, bed sheets, and school uniforms) and household fabrics (curtain materials, kitchen napkins, diapers and towels). These products form the core of the sub-sector. The main products of the man-made fibres (synthetics) and their blends include: uniforms, knitted blouses, socks etc. These are mainly made from polyes- ter, acrylic and other synthetics. There are also a number of small firms hand-printing their designs into bleached cotton fabrics, also known as tie and dye or batik cloth. Also, traditional or indigenous textiles such as Kente cloth (traditional woven fabric), Adinkra cloth (tradi- tional hand printing fabric) and other types of woven fabrics used for various purposes such as smock making etc. are proposed. Total industry output peaked at 129 million yards in 1977 with capacity utilization rate of about 60 percent. GTP maintained the lead in the industry with an annual production of 30.7 million yards (includes the outputs of Juapong and Tema plants). This was followed by GTMC, ATL, and Printex with production levels of 15 million, 13 million and 6 million yards respectively. Unfortu- nately, total industry output declined from its 1970 level to 46 million yards in 1995 but recovered to 65 million yards in 2000. As at March 2005, GTP was producing 9 million yards, ATL 18 million yards GTMC 2.24 million yards and Printex 9.84 million yards. A total annual out- put of 39.04 million yards was produced by the industry as at March 2005, which translates to an average of 49.4% of initially installed capacity of the four firms. Thus output had declined from 65 million yards in 2000 to 39 million yards in 2005 (see Table 1). A recent survey of textile and garment firms in Accra- Tema indicated that firms have cut down significantly on output, in fact, more than half (about 75 percent) of tex- tile and garment manufacturers answered in the affirma- tive. About 7 percent of this number indicated that they 1Size categories: small-scale (has 5-29 employees), medium-sized (has 30-99 employees), large-scale (employs 100 or more people) 2About 44 percent of industry respondents have cut down on employ- ment. From the total number of firms that had shed staff, 59 percent have laid off up to 5 percent of their workforce, 24 percent laid off up to 6-10 percent and 11 percent have cut down employment by over 70 p ercent between 2000 and 2005.  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 56 had reduced output by up to 20%. A further 32 percent indicated their output reduced by 21-30 percent. About 21 percent had reduced production by 31-40 percent while 11 percent have had their output reduced by 41-50 percent and a further 4 percent had recorded over 50 percent fall in output. The rest (25 percent) could not tell by how much they have cut down on production. The reasons for the decline in output are varied. The survey respondents offered several reasons for cutting down on production; about 44 percent of the manufacturers who claimed they have cut down on pro- duction cited low demand for local textile products as the principal reason necessitating their action; while 15 per- cent also mentioned high cost of production and 11 per- cent cited high wage bills resulting in their inability to pay workers. Another 15 percent blamed the problem largely on the influx of imitated products from abroad, particularly Asia and Cote d’Ivoire. Others mentioned smuggling and dumping (7 percent) as well as lack of raw materials (4 percent). Imports of textile have grown steadily over the years. In 1992, the country imported US $35 million worth of fabrics and garments. This increased to US$ 57 million in 1998 and by the first half of 1999, US$ 42 million worth of fabrics and garments had been imported (MOTI, 2002). It is estimated that at the end of the first quarter of 2005, imported textile prints will have accounted for 48% of total textile prints in the Ghanaian market (Ghana Employers Association, 2005). The local market is fac- ing stiff competition from finished imported textile prints such as calico, grey baft, furnishing materials usually from Cote d’Ivoire, Nigeria, China, and most recently from India and Pakistan. Consumers have argued that although the locally produced finished fabrics are rela- tively better in terms of quality, the market for imported products has increased because the products have attrac- tive colours, new designs, a softer and glossier finish. Table 1 indicates the trend in imported fabrics from 1997-2000. 2.1. Importance of Textile Exports to Ghana’s Economy The use of textiles in Ghana is a way of life and it is rooted in historical and cultural antecedents. They are used for funerals, naming ceremonies, church service, and official functions, to name but a few. Textile exports are an important source of foreign exchange and revenue to textile manufacturing firms. Textile exports generated $27.2 million in 1992 and this increased to $179.7 mil- lion in 1994 but revenue from exports declined consis- tently thereafter and by 1998, they had fallen to $ 3.173 million. It is worth mentioning that in 2000, Ghana qualified for AGOA; and exports of Ghanaian textile and apparel to the US market amounted to $550,000 in 2002, $4.5 million in 2003 and $7.4 million in 2004. Imports of US textile and apparel were $8.87 million, $12.73million and $11.48 million respectively over the same period (http://www.agoa.info). The decline in textile exports from 1992 to 1998 (see Table 2) can be attributed to internal and external bot- tlenecks. Ghanaian manufacturers of textiles generally agree that the market for exports is huge, but have reser- vation about operating in some of these markets particu- larly within the ECOWAS sub-region due to trade barri- ers. Some of the trade barriers include among others, imposition of 20% duty by Cote d’Ivoire (contrary to ECOWAS regulations), transit tax collected at Benin, extortion by Nigerian authorities, and the risk of cur- rency devaluation. Poor packaging by some manufactur- ers/exporters also serves as a barrier to exports to mar- kets such as the EU and the United States of America. Also, poor finishing of products (quality/conformity to standards), technical barriers, inability of some manu- facturers to meet export orders on schedule, high tariffs Table 1. Textile imports by type. Wax Print Java/Fancy & the similar print Calico (Bleached Fabric) Year Qty/Vol. (Kg) US$ (000) Qty/Vol. (Kg)US$ (000) Qty/Vol. (Kg) US$ (000) 1997 30,775 106 152,300 406 9,418 41 1998 11,423 571 46,881 204 80,138 601 1999 86,700 2,318 136,634 477 182,091 1,044 2000 135,197 1,313 455,764 1,818 1,034,978 5,247 Source: MOTI, 2002 Table 2. General textile fabric imports & exports (excluding AGOA). 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Exports US$ million 27.18 76.7 179.7 7.703 3.429 5.074 3.173 na Imports US$ million 34.57 38.28 39.40 42.30 53.35 52.65 56.55 42.293 Source: MOTI, 2002 3Half-year figure.  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 57 charged in some export destinations of Ghanaian textiles4 are among the barriers to exports to external markets. The main export destination for made-in-Ghana tex- tiles as at 2004 included EU countries (55%), the U.S. (25%), and ECOWAS (15%). The remaining 5 percent are exported to other countries, mostly Southern and East African states (mainly South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Ethiopia etc). Textile and garment exports from Ghana comprise fancy prints, wax prints, Java prints, calico smock, ladies dresses, men’s wear, etc. The indigenous textile products like Kente, a special fabric produced on a traditional loom, Adinkra (hand prints) and smock or fugu are also exported. Batik or tie and dye fabrics are also used to produce all kinds of products for the export markets. These products include: a unique brand of carefully crafted handbags, casual wear for ladies and gentlemen, shirts, dresses; napkins, cushion covers, bed- spreads, chair backs, curtains, toys and many others. 3. Brief Overview of Literature The country-of-origin effect has been identified as an im- portant factor explaining customers’ product preference [5-7]. Reference [8] define country-of-origin image as how a product designed, manufactured, or branded in a developed country is perceived in a developing country. Reference [9] argues that the country of manufacture and product quality strongly influence consumer decision making in globally available product categories. The extant empirical literature from developed coun- tries suggests that consumers in those countries tend to prefer products from developed countries to those from less developed countries [10,11]. They explain that con- sumers prefer products from their own countries first, followed by products from other developed countries before considering those from other countries. Normally (in Mexico), consumers tend to have a preference for local products in countries where there is strong patriot- ism, national pride, or consumer ethnocentrism [12]. Reference [9] also suggests that consumers prefer do- mestically manufactured goods and are willing to pay higher price for them. It is only when imported goods are of a significantly superior quality that consumers will move to obtain those. With respect to developing countries, the existing lit- erature suggests that customers prefer western to domes- tic products. Reference [13,14] for instance found that consumers in the former socialist countries of eastern and central Europe prefer western to domestic products. Reference [14] showed that the price effect was not as important as the country-of-origin effect in explaining customer choice in Russian, Polish and Hungarian. Ref- erence [11] reported that Mexicans have a poor percep- tion of local products and they tend to rate American and Thailand household electronic products above Mexican- made brands. Reference [15,16] also explain that high income levels in Mexico account for more preference for foreign goods. Reference [17] reported that there is a great demand for western consumer goods among Indian consumers. In a study in Czech, Reference [18] found that customers had a preference for German products as compared to products from the Czech Republic. Refer- ence [19] found that Bangladeshi consumers signifi- cantly preferred western-made products, though there were differences in their perceptions across product classes as well as degree of suitability of sourcing coun- tries. In a Chinese study, Reference [20] showed that there was huge preference for western products among the Chinese people. A study by Reference [21] also re- vealed that the elite in Pakistan consider country of ori- gin of products in taking purchasing decisions. A number of studies have also been carried out in Af- rican countries with respect to the country-of-origin ef- fect. Reference [22] argues that, in economically under- developed countries, preference for domestic products tends to be weaker. Reference [23], in a Nigerian study, found that the Nigerian consumer obsession with for- eign-made goods has had a detrimental effect on the do- mestic manufacturing industry. They found that the country-of-origin is significantly more important than price and other product attributes in consumer preference. Nigerian consumers have a negative image of the ‘Made in Nigeria’ label, rating it lower than labels from more economically developed countries. They also found that the superior reliability and technological advancement of foreign products are the most important correlates of the Nigerian consumer’s likelihood to purchase foreign pro- ducts. Reference [24] examined the impact of coun- try-of-origin effects and consumer attitudes towards buy local campaign initiatives. They found that, the attitudes of consumers to buy locally-made campaigns can be cha- racterized as protectionist, nationalistic, and self-interest seeking. In a study on five West African countries, Reference [25] investigated the country-of-origin effects in service evaluation and found that situational personal character- istics, such as motivation and ability to process informa- tion, may influence use of country-of-origin attributes in evaluating a service. Besides, individual characteristics, such as ethnocentrism and culture orientation, may in- fluence country-of-origin preference in service evalua- tion. In a Ghanaian study, Reference [8] examined con- 4The survey of 40 textile manufacturers cited transit taxes as the major constraint to exports (about 29%), followed by haulage and high trans- p ort cost (24 percent), extortion at the borders (12 percent), and poo r infrastructure (12 percent). About 18 percent cited some other prob- lems.  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 58 sumer attitudes towards local and imported products in a developing country market. They found that the coun- try-of-origin of the products is more important than price and other product attributes. They showed that the Gha- naian consumer holds the ‘Made in Ghana’ label in low regard relative to foreign labels, whilst superior quality and con- sumer taste are the second most important rea- sons for the Ghanaian consumers’ preference for foreign products. Clearly, the empirical literature suggests that consum- ers consider products from developed countries more favourably than those from less-developed and develop- ing countries. Following from this hypothesis, this study is therefore positioned to ascertain Ghanaians’ prefer- ence for imported textiles to locally manufactured ones. This present study focuses on consumers, traders and manufacturers of textiles, unlike the study by Reference [8] which concentrated on only customers of rice, cloth- ing and textiles. 4. Do Consumers Prefer Locally Manufactured Textile to Imported Ones? The study used secondary as well as primary data on textile production, imports and consumption in Ghana. A total of 40 manufacturers of textiles in Accra, 40 con- sumers of textile products as well as 40 traders of textiles located in the business district of Accra were interviewed in 2007 using a structured questionnaire for each group of respondents. The study adopted a snow ball sampling technique in selecting respondents from the markets and face-to-face interviews were conducted. There is no ex- act number of textile traders in Ghana but we believe their views will not vary widely across the country. Thus, 40 traders were selected in view of the perceived homo- geneity of most textile traders. The manufacturers se- lected included the four major textile traders in addition to other small-scale operators. Most of the respondents (traders) were women and above 51 years. This confirms the perception that trading in textiles is a preserve for women, who are mainly found in popular market centres such as the Makola Market in the city of Accra, Ghana. As expected, most (a quarter) of the traders have had little or no formal educa- tion. This reflects the characteristics of the informal - private sector in Ghana. In terms of age, out of the 40 consumers of textiles interviewed, only 3 percent of the respondents were below 20 years while 60 percent of total respondents were within the 20-50 years and 2.5 percent were above 51 years. Trading in textiles seems to be a very active business; the majority (55 percent) of the respondents indicated they buy textile products weekly while about a quarter (22.5 percent) of them said they buy textile products monthly. Only 10 percent of them buy textile products fortnightly. This is an indication of high turnover of stock among textile traders and all things being equal, traders should earn appreciable level of margins. 4.1. Preference for Local or Imported Textiles Concerning taste and preference, interviews with traders of textiles revealed strong preference for locally made textiles. More than half (53 percent) of the respondents indicated a strong preference for local textile products while 40 percent preferred imported textile products. The rest (7 percent) were indifferent. Figure 1 presents trad- ers preferences for textiles. This finding tends to contra- dict the country-of-origin effect and the results of previ- ous studies in Africa and other developing countries. For those who said they preferred buying and selling imported textile products, about 26 percent of them indi- cated that imported textiles are quite affordable, 21 per- cent believed they are more profitable, about 11 percent thought they are attractive. Only 5 percent claimed im- ported textiles are of good quality while the rest (37 per- cent) could not assign any reason for their strong prefer- ence for imported textiles. About 42 percent of the re- spondents cited high prices for local textiles while about 22 percent cited low demand for local textiles. About 15 percent mentioned low turnover of local textile products. About 55 percent of consumers indicated that they buy textile products occasionally while 24 percent claimed they buy them annually. About 10 percent often buy tex- tile products monthly and 2 percent often buy them weekly. The rest usually buy them quarterly and bi-an- nually (see Figure 2). This is an indication that, textiles are mainly for occasional days such as naming ceremo- nies, funerals, engagement and festivals in Ghana. Locally made Imported N o response 7% 40% 53% Source: Survey Data, 2007 Figure 1. Consumer preferences.  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 59 As shown in Figure 3, more than half of those who prefer locally made textile products (53 percent) claimed local textile products are of good quality (this represents 40 percent of total sample). Others claimed they are af- fordable (17 percent), attractive (20 percent) while the rest (7 percent) claimed local textiles are cheap. 4.2. Ban on Imported Textiles With respect to respondents’ views on placing a ban on imported textiles, some of them (35 percent) indicated that textiles imported into Ghana should be banned. About 65 percent of them did not support a ban (see Figure 4). For those who thought imported textiles should be banned, about 43 percent of them were of the view that the ban would promote the local textile industry, about 31 percent thought the ban could help the local industry generate more employment. The rest, 23 percent believed the ban could salvage the local textile industry. According to those who did not support the ban on imported textiles, about 46 percent claimed they are cheap and affordable. About 18 percent of the respondents claimed they are profitable while 11 percent thought they are of superior quality. Almost 70 percent of respondents expected to see a reduction in the price of local textile products, while 22 percent of them expected to see improvement in quality and attraction of local textile products. The rest advocated for a reduction in taxes and avoidance of fa- vouritism. Weekly For t n i gh tl y Monthly Quarterly Bi-annually Annually Occasionall y 2% 24% 55% 3% 3% 3% 10% Source: Survey data Figure 2. Frequency of purchase. Cheap Aff o r dabl e Good qualit y Attractive Other 53% 3% 20% 17% 7% Source: Survey data Figure 3. Reasons for textile preferences. Yes N o 35% 65% Source: Survey data, 2007 Figure 4. Ban on imported textile. 4.3. Comparing Quality Comparing the quality of imported textile products with local textile products, majority of consumers (48 percent) claimed imported textile products are better, while 27 percent went for local textile products. Only 5 percent thought they are of the same quality, while 20 percent were indifferent (see Figure 5). 4.4. Policy Changes Most of the traders stressed the need for a reduction or removal of taxes on imported raw materials. Other policy recommendations include giving the products to traders on credit, imposing heavier taxes on imported textiles, placing a ban on imported textiles, making local textile products affordable, and promoting wearing of local tex- tile products. For example, 37 percent suggested a reduc- tion in taxes on imported raw materials, another 27 per- cent advocated for marketing and promotion of local textiles. About 13 percent thought subsidies should be given to the local textiles industry. Only 13 percent how- ever, called for a total ban on imported textile products (see Figure 6). 5. Conclusions and Policy Implications This study investigated whether consumers prefer lo- cally-made textile products to imported ones and if so, why? The approach involved the use of micro and macro data. The macro data was obtained from the Ministry of Trade and other relevant literature. The micro data was Localt textiles are better Imported textiles are better They are similar in quality Indifferent 20% 27% 48% 5% Source: survey data Figure 5. Quality comparison.  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 60 Reduce/remove taxes on imported raw materials Marketing and promotion of local textiles Give products to traders on credit Ban imported textiles N ores p onse 27% 13% 37% 13% 10% Source: Survey data Figure 6. Expected policy changes (traders). obtained from a survey of 40 textile and clothing manu- facturers in Accra, 40 consumers and an equal number of traders located in the business districts of Accra. The study made very useful revelations. The key findings of the study show that, most consumers prefer locally-made textiles to imported ones, contrary to the country-of-ori- gin effect. Nearly two decades after independence, the textile sub-sector was the major key player in Ghana’s Indus- trial sector, contributing significantly to employment and growth in the economy. However, the sub-sector which was once the leader in Ghana’s industrial sector has un- dergone a considerable decline over the years, largely due to the liberalisation programmes which made it al- most impossible for Ghana’s textile products to compete with the cheap imports, particularly from Asia. It is however estimated that the few companies that managed to survive operated at just about 5 percent in- stalled capacity since 1995. Various reasons have ac- counted for the decline. Some of the major ones men- tioned include: low demand for local textile products and influx of second hand clothing; lack of competitiveness of local textiles against imported textiles due to high cost of local textiles which resulted from high cost of produc- tion5; and smuggling. In view of the current crisis faced by the industry, its outlook remains bleak and therefore calls for pragmatic polices that will lead to both local and global restructur- ing of the industry. Locally, it is necessary that concrete steps are taken to address the problem of cheap imports, under-declared imports, wrongly described textile im- ports, and copied brands, markings, tickets and labels lead to the recent proposal by government to establish an Economic Intelligence Unit, including the Ghana Stan- dards Board, to arrest and punish those engaged in trade malpractices. In this Economic Intelligence Unit to arrest and punish those engaged in trade malpractices is timely. The penalty for those culprits engaging in these malprac- tices should be severe to serve as a deterrent to other perpetrators of the crime. Secondly, the unit should be proactively and effectively managed; otherwise, arresting the perpetrators will prove elusive. On the global scene, trade negotiations and fair trade practices, particularly, within the textile and garments sub-sector should be made explicit and adhered to. In- stances of copying brands and other product markings from other countries should be discouraged. This should go together with fair trade practices and preferential ac- cess to markets in developed countries. 6. References [1] P. Quartey, “The Textile and Clothing Industry in Ghana,” In: H. Jauch and R. Traub-Merz, Eds, The Fu- ture of the Textile and Clothing Industry in Sub-Saharan Africa, Bub Bonner Universitats-Buckdruckerei, Ger- many, 2006, pp. 135-146. [2] Ministry of Trade and Industry, “Study of the Textile Sub-sector,” A Report Prepared by Brucks & Associates for MOTI, November 2002. [3] V. O. Ampofo, “Ghana’s Textile and Garment Industry,” Ministry of Trade and Industry, Industrial Development and Investment Division, 2002. [4] Ghana Employers Association, “Measures to Save the Textile Industry in Ghana,” A Report Prepared by the Sub-Committee of the National Tripartite Committee on Measures to Save Ghana’s Textile Industry, March 2005. [5] J. Agrawal and W. A. Kamakura, “Country of Origin: A Competitive Advantage?” International Journal of Re- search in Marketing, Vol. 16, No. 4, 1999, pp. 225-267. doi:10.1016/S0167-8116(99)00017-8 [6] P. W. J. Verlegh and B-EM Steenkamp, “A Review and Meta-Analysis of Country of Origin Research,” Journal of Economic Psychology, Vol. 20, No. 5, 1999, pp. 521- 546. doi:10.1016/S0167-4870(99)00023-9 [7] S. Bhaskaran and N. Sukumaran, “Contextual and Meth- odological Issues in COO Studies,” Marketing Intelli- gence and Planning, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2007, pp. 66-81. doi:10.1108/02634500710722407 [8] R. A. Opoku and P. A. K. Akorli, “The Preference Gap: Ghanaian Consumers’ Attitudes toward Local and Im- ported Products,” African Journal of Business Manage- ment, Vol. 3, No. 8, 2009, pp. 350-357. [9] G. A. Knight, “Consumer Preference for Foreign and Domestic Products,” Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 16, No. 2, 1999, pp. 1-11. [10] C. K. Wang and C. Lamb, Jr., “The Impact of Selected Environmental Forces upon Consumers’ Willingness to Buy Foreign Products,” Journal of the Academy of Mar- keting Science, Vol. 11, No. 2, 1983, pp. 71-94. doi:10.1007/BF02721862 [11] E. D. Jaffe and C. R. Martinez, “Mexican Consumer At- titudes towards Domestic and Foreign made Products,” Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 7, No. 3, 1995, pp. 7-27. doi:10.1300/J046v07n03_02 5Due to high cost of local cotton, obsolete plants and machinery, high cost of utilities, overstaffing, high cost of finance (high interest rate) etc.  P. QUARTEY ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 61 [12] L. A. Heslop and N. Papadopoulos, “But Who Knows Where or When: Reflections on the Images of Countries and Their Products. In: N. Papadopoulos and L. A. Heslop, Eds., Product-Country Images: Impact and Role in International Marketing, International Business Press, New York, 1993. [13] N. Papadopoulos, L. A. Heslop and J. Beracs, “National Stereotypes and Product Evaluations in a Socialist Coun- try,” International Marketing Review, Vol. 7, No. 1, 1990, pp. 32-47. doi:10.1108/02651339010141365 [14] R. Ettenson, “Brand Name and Country of Origin Effects in the Emerging Market Economies of Russia, Poland, and Hungary,” International Marketing Review, Vol. 10, No. 5, 1993, pp. 314-336. doi:10.1108/02651339310050057 [15] J. Almonte, C. Falk, R. Skaggs and M. Cardenas, “Coun- try of Origin Bias among High Income Consumers in Mexico: An Empirical Study,” Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 8, No. 2, 1995, pp. 27-44. doi:10.1300/J046v08n02_03 [16] W. Bailey and S. A. G. de Pineres, “Country of Origin Attitudes in Mexico: The Malinchismo Effect,” Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1997, pp. 25-41. doi:10.1300/J046v09n03_03 [17] M. Jordan, “In India, Repealing Reform is a Tough Sell: Leaders Decry Foreign Goods, But Consumers Love Them,” In: Wall Street Journal (Eastern Edition), 22 May 1996, p. A18. [18] D. B. Klenosky, S. B. Benet and P. Chatraba, “Assessing Czech Consumers’ Reactions to Western Marketing Practices: A Conjoint Approach,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 6, No. 2, 1996, pp. 189-198. doi:10.1016/0148-2963(95)00121-2 [19] E. Kaynak, O. Kucukemiroglu and A. S. Hyder, “Con- sumers’ Origin (coo) Perceptions of Imported Products in a Homogenous Less-developed Country,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 34, No. 10, 2000, pp. 1221- 1241. doi:10.1108/03090560010342610 [20] N. Zhou and R. W. Belk, “Chinese Consumer Readings of Global and Local Advertising Appeals,” Journal of Advertising, Vol. 33, No. 3, 2004, pp. 63-73. [21] H. Khan and D. Bamber, “Market Entry Using Coun- try-of-Origin Intelligence in an Emerging Market,” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2007, pp. 22-35. doi:10.1108/14626000710727863 [22] V. V. Cordell, “Effects of Consumer Preferences for For- eign Sourced Products,” Journal of International Busi- ness Studies, Vol. 23, No. 2, 1992, pp. 251-269. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490267 [23] C. Okechuku and V. Onyemah, “Nigerian Consumer Attitudes toward Foreign and Domestic Products,” Jour- nal of International Business Studies, Vol. 30, No. 3, 1999, pp. 611-622. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490086 [24] K. Saffu and J. Walker, “The Country-of-Origin Effects and Consumer Attitudes to Buy Local Campaign: The Ghanaian Case,” Journal of African Business, Vol. 7, No. 1-2, 2006, pp. 183-199. doi:10.1300/J156v07n01_09 [25] J. L. Ferguson, K. Q. Dadzie and W. J. Johnston, “Coun- try-of-origin Effects in Service Evaluation in Emerging Markets: Some Insights from Five West African Coun- tries,” Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, Vol. 23, No. 6, 2008, pp. 429-437. doi:10.1108/08858620810894472 |