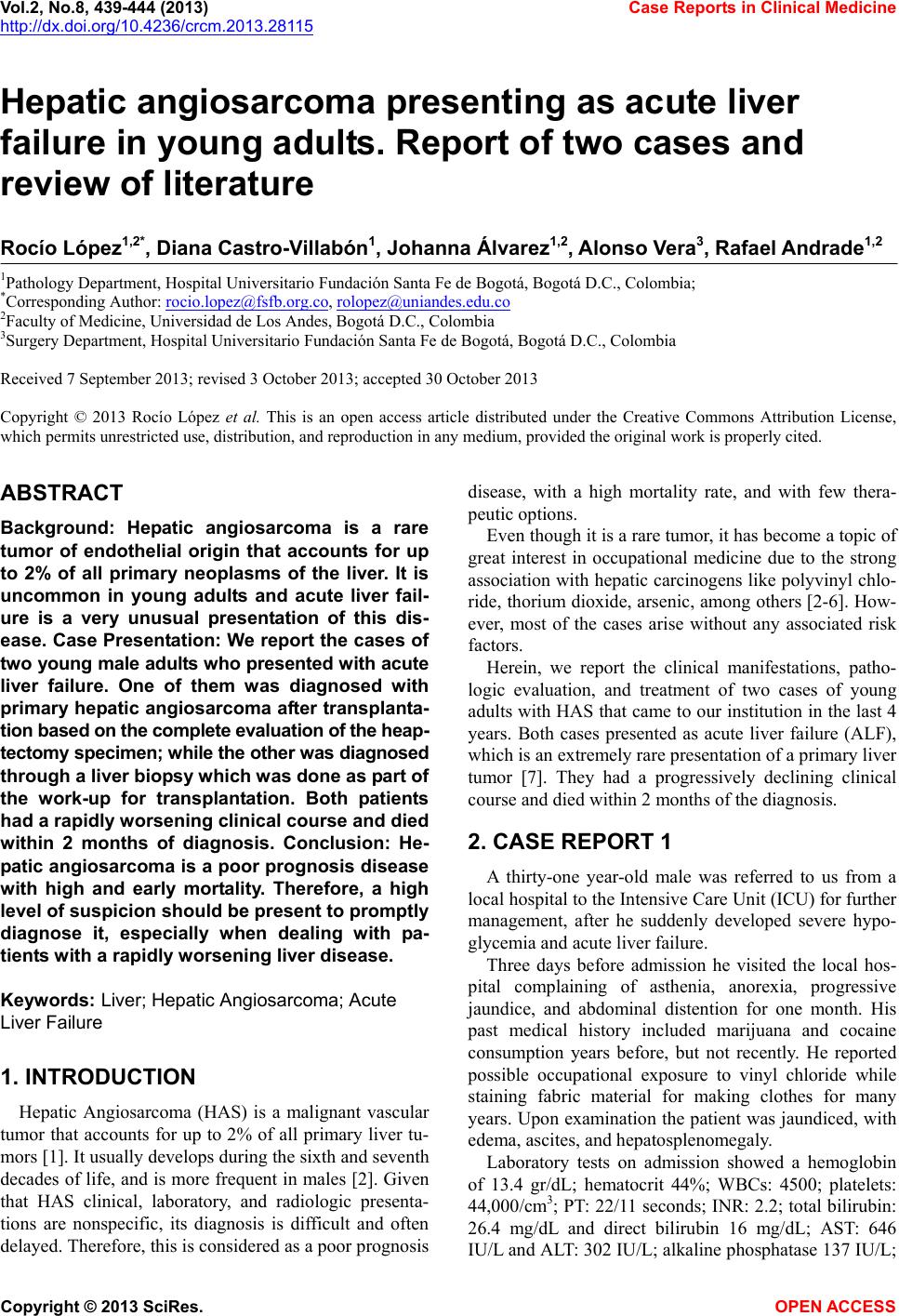

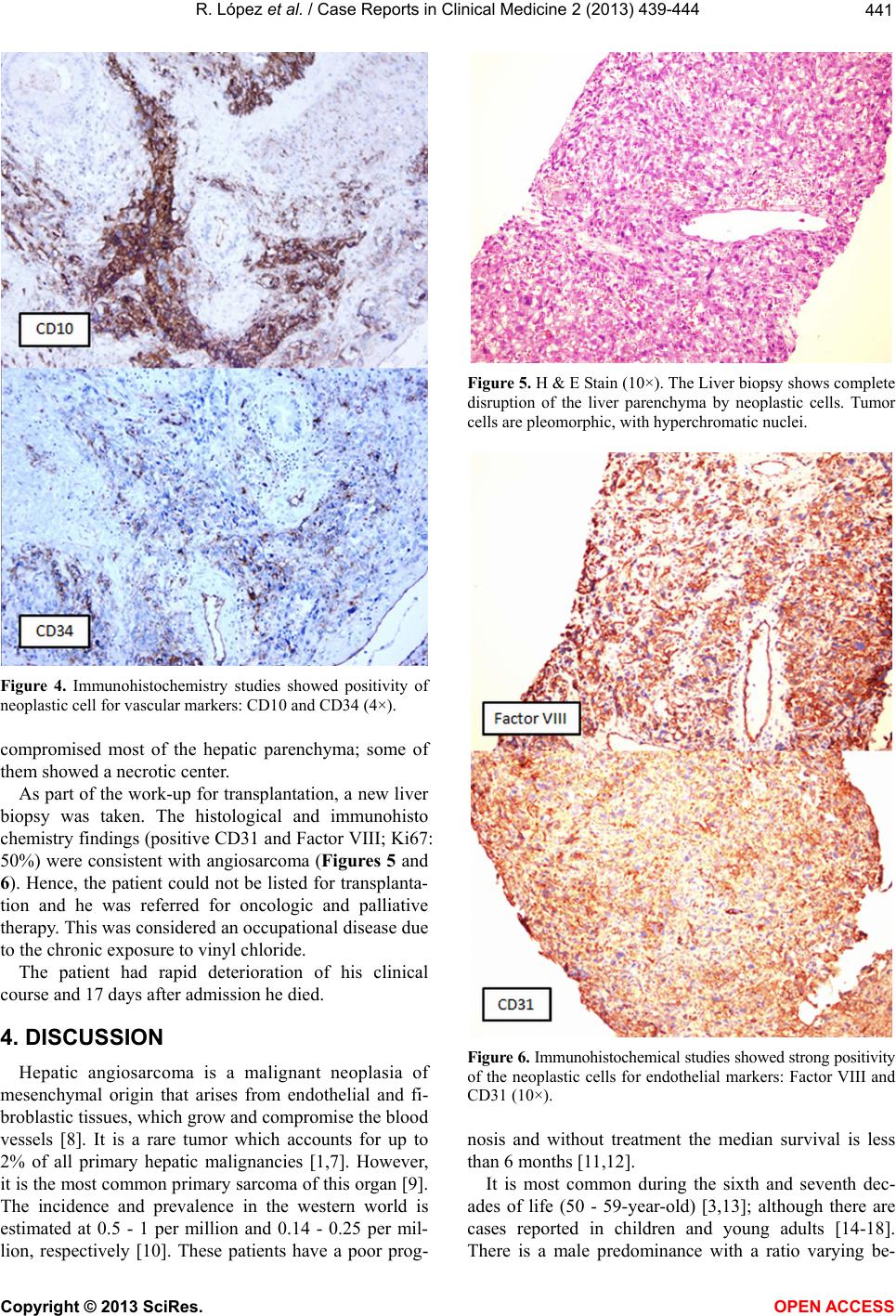

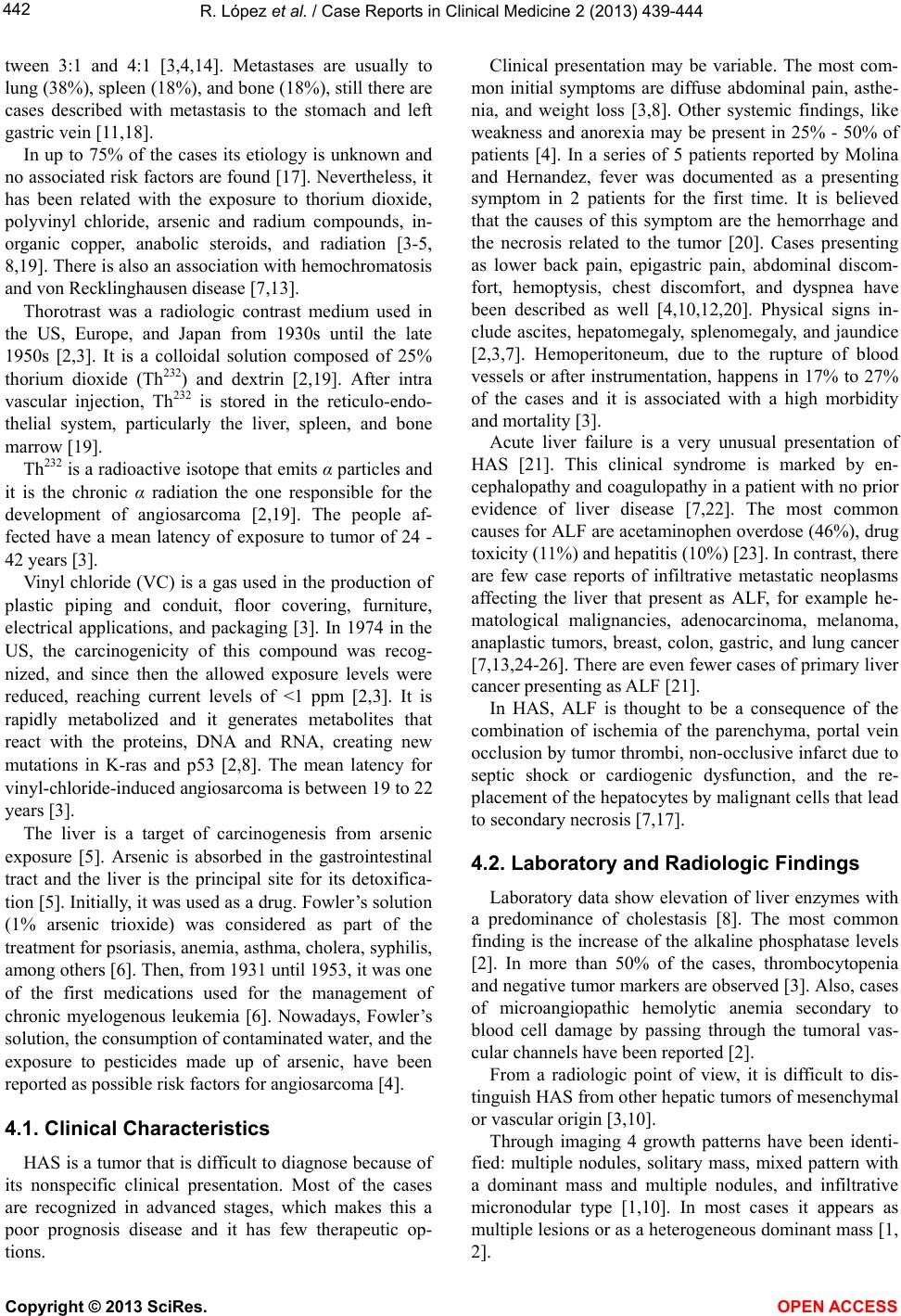

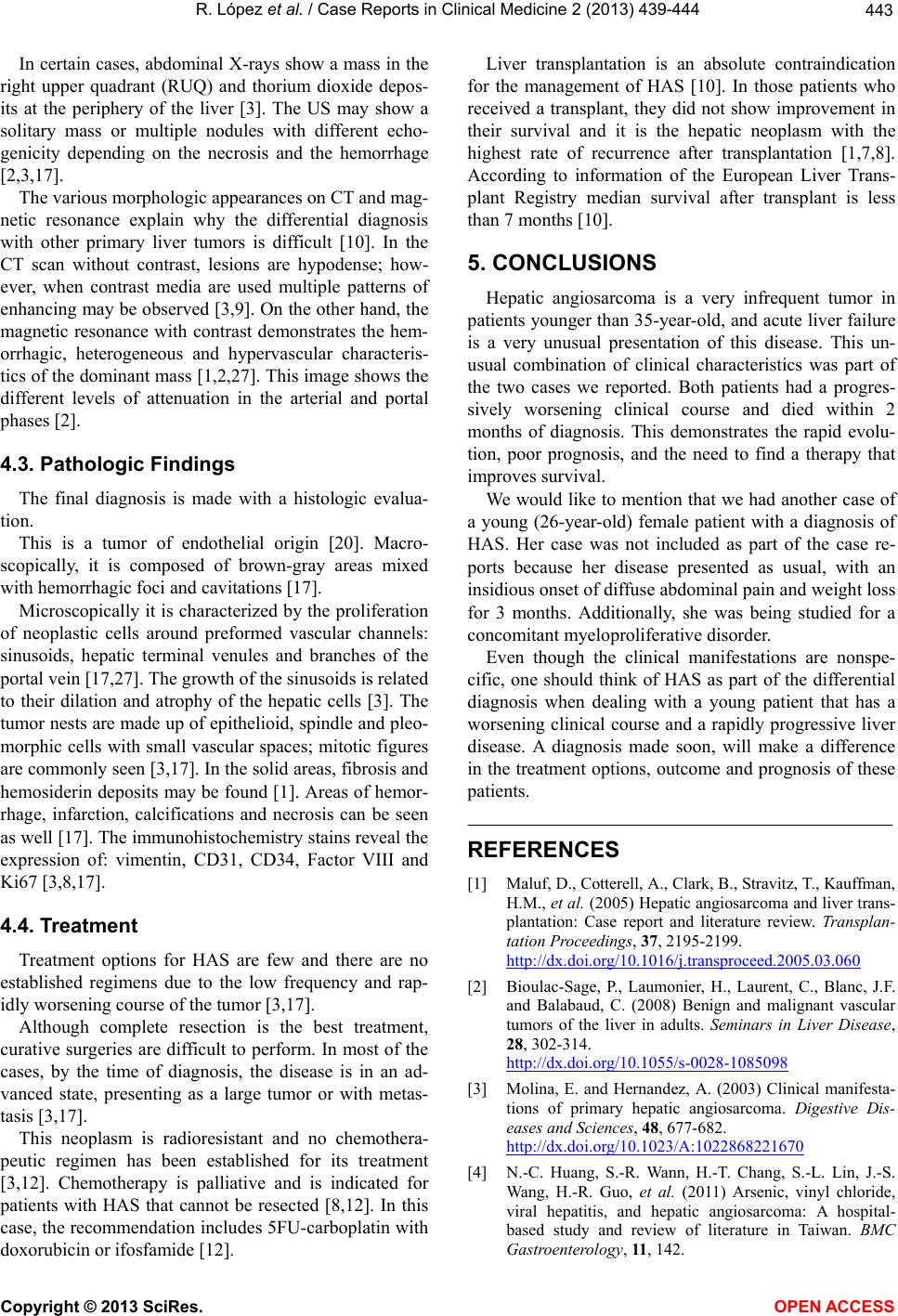

Vol.2, No.8, 439-444 (2013) Case Reports in Clinical Medicine http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/crcm.2013.28115 Hepatic angiosarcoma presenting as acute liver failure in young adults. Report of two cases and review of literature Rocío López1,2*, Diana Castro-Villabón1, Johanna Álvarez1,2, Alonso V era3, Rafael Andrade1,2 1Pathology Department, Hospital Universitario Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, Bogotá D.C., Colombia; *Corresponding Author: rocio.lopez@fsfb.org.co, rolopez@uniandes.edu.co 2Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de Los Andes, Bogotá D.C., Colombia 3Surgery Department, Hospital Universitario Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, Bogotá D.C., Colombia Received 7 September 2013; revised 3 October 2013; accepted 30 October 2013 Copyright © 2013 Rocío López et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Background: Hepatic angiosarcoma is a rare tumor of endothelial origin that accounts for up to 2% of all primary neoplasms of the liver. It is uncommon in young adults and acute liver fail- ure is a very unusual presentation of this dis- ease. Case Presentation: We report the cases of two young male adults who presented with acute liver failure. One of them was diagnosed with primary hepatic angiosarcoma after transplanta- tion based on the complete evaluation of the heap- tectomy specimen; while the other was diagnosed through a liver biopsy which was done as part of the work-up for transplantation. Both patients had a rapidly worsening clinical course and died within 2 months of diagnosis. Conclusion: He- patic angiosarcoma is a poor prognosis disease with high and early mortality. Therefore, a high level of suspicion should be presen t to promptly diagnose it, especially when dealing with pa- tients with a rapidly worsening liver disease. Keyw ords: Liver; Hepatic Angiosarcoma; Acute Liver Failure 1. INTRODUCTION Hepatic Angiosarcoma (HAS) is a malignant vascular tumor that accounts for up to 2% of all primary liver tu- mors [1]. It usually develops during the sixth and seventh decades of life, and is more frequent in males [2]. Given that HAS clinical, laboratory, and radiologic presenta- tions are nonspecific, its diagnosis is difficult and often delayed. Theref ore, this is con sid ered as a poor progno sis disease, with a high mortality rate, and with few thera- peutic o p tions. Even though it is a rare tu mor, it has be come a top ic of great interest in occupational medicine due to the strong association with hepatic carcinogens like polyvinyl chlo- ride, thorium dioxide, arsenic, among others [2-6]. How- ever, most of the cases arise without any associated risk factors. Herein, we report the clinical manifestations, patho- logic evaluation, and treatment of two cases of young adults with HAS that came to our institution in the last 4 years. Both cases presented as acute liver failure (ALF), which is an extremely rare presentation of a primary liver tumor [7]. They had a progressively declining clinical course and died within 2 months of the diagn o sis. 2. CASE REPORT 1 A thirty-one year-old male was referred to us from a local hospital to the Inten sive Care Unit (ICU) for further management, after he suddenly developed severe hypo- glycemia and acute liver failure. Three days before admission he visited the local hos- pital complaining of asthenia, anorexia, progressive jaundice, and abdominal distention for one month. His past medical history included marijuana and cocaine consumption years before, but not recently. He reported possible occupational exposure to vinyl chloride while staining fabric material for making clothes for many years. Upon examination the patient was jaundiced, with edema, ascites, and hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory tests on admission showed a hemoglobin of 13.4 gr/dL; hematocrit 44%; WBCs: 4500; platelets: 44,000/cm3; PT: 22/11 seconds; INR: 2.2; total bilirubin: 26.4 mg/dL and direct bilirubin 16 mg/dL; AST: 646 IU/L and ALT: 302 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase 137 IU/L; Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  R. López et al. / Case Reports in Clinical Medicine 2 (2013) 439-444 440 albumin 2.5 g/dL; creatinine: 0.7 mg/dL. Serology for hepatitis A, B, C and autoimmune markers were negative. An abdominal paracentesis was performed and th e ascitic fluid evidenced proteins of 2.3 g/dL and a serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) of 1.1 g/dL. Doppler ultra- sound (US) of the liver demonstrated a heterogeneous parenchyma with irregular borders, and no focal lesions. Plus, the portal vein, hepatic artery, and suprahepatic vein blood flow was within normal limits. Following these findings a liver biopsy was done and it revealed venous blood flow obstruction suggestive of Budd-Chiari syndrome. The patient experienced rapid deterioration of his neurological status, renal failure, and he required hemo- dynamic and ventilatory support. As a consequence, he was listed for an urgent transplantation, and on the fifth day after his admission to our center, he underwent a successful liver transplantation. The hepatectomy specimen weighed 2489 gr; it had a spongy appearance and multiple hemorrhagic areas (Figure 1). Microscopically, there was massive invasion of the liver parenchyma by the tumor. Neoplastic cells were pleomorphic and spind le shap ed with high mitotic active- ity (Figures 2 and 3), and they were positive for CD31, CD34, factor VIII, and CD10 inmunohistochemistry markers (Figure 4). The proliferation index was estab- lished with the Ki67 marker (50%). One month after the transplantation the patient had recurrence of the tumor involving the bone marrow. He received 3 cycles of chemotherapy, but he had a torpid clinical course and died 2 months later. 3. CASE REPORT 2 A twenty year-old male, who worked as a car techni- cian, presented at the emergency room because of som- nolence, disorientation, and disturbances of the sleep- wake cycle for 5 days. Additionally, he presented with Figure 1. Gross appearance of the liver. The explanted speci- men shows multiple cystic and hemorrhagic areas. Figure 2. H & E Stain (20×). The microscopic section of the explanted liver shows diffuse infiltration of the hepatic paren- chyma by the tumor, vascular spaces of varying shapes and sizes, areas of hemorrhage, and extramedullary hematopoiesis. Figure 3. H & E Stain (20×). The microscopic section of the explanted liver shows vascular spaces lined by atypical endo- thelial cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. Giant pleomorphic neoplastic cells are observed. upper abdominal pain and increased abdominal girth. Initially, he was admitted to a local hospital and an abdominal US, a paracentesis, and a liver biopsy were performed. The results demonstrated a mass in the liver suggestive of hemangioendothelioma. His past medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination on admission revealed a patient who had altered level of consciousness, mucocutaneous jaundice, ascites, hepatosplenomegaly, and edema of the lower limbs. Laboratory data: hemoglobin: 14.4 gr/dL; hematocrit: 43.2%; WBCs: 4900; platelets: 18,000/ cm3; PT: 39.5/27.5 seconds; INR: 1.7; AST: 446 IU/L and ALT 140 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase: 285 IU/L; total bilirrubin: 17.65 mg/dL and direct bilirrubin: 10.45 mg/dL; albumin: 0.94 g/dL. The abdominal CT scan showed hepatomegaly and multiple focal lesions that Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  R. López et al. / Case Reports in Clinical Medicine 2 (2013) 439-444 441 Figure 4. Immunohistochemistry studies showed positivity of neoplastic cell for vascular markers: CD10 and CD34 (4×). compromised most of the hepatic parenchyma; some of them showed a necrotic center. As part of the work-up for transplantation, a new liver biopsy was taken. The histological and immunohisto chemistry findings (positive CD31 and Factor VIII; Ki67: 50%) were consistent with angiosarcoma (Figures 5 and 6). Hence, the patient could not be listed for transplanta- tion and he was referred for oncologic and palliative therapy. This was considered an occupational disease due to the chronic exposure to vinyl chloride. The patient had rapid deterioration of his clinical course and 17 days after admission he died . 4. DISCUSSION Hepatic angiosarcoma is a malignant neoplasia of mesenchymal origin that arises from endothelial and fi- broblastic tissues, which grow and compromise the bloo d vessels [8]. It is a rare tumor which accounts for up to 2% of all primary hepatic malignancies [1,7]. However, it is the most common p rimary sarcoma of this organ [9]. The incidence and prevalence in the western world is estimated at 0.5 - 1 per million and 0.14 - 0.25 per mil- lion, respectively [10]. These patients have a poor prog- Figure 5. H & E Stain (10×). The Liver biopsy shows complete disruption of the liver parenchyma by neoplastic cells. Tumor cells are pleomorphic, with hyperchromatic nuclei. Figure 6. Immunohistochemical studies showed strong positivity of the neoplastic cells for endothelial markers: Factor VIII and CD31 (10×). nosis and without treatment the median survival is less than 6 months [11,12]. It is most common during the sixth and seventh dec- ades of life (50 - 59-year-old) [3,13]; although there are cases reported in children and young adults [14-18]. There is a male predominance with a ratio varying be- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  R. López et al. / Case Reports in Clinical Medicine 2 (2013) 439-444 442 tween 3:1 and 4:1 [3,4,14]. Metastases are usually to lung (38%), spleen (18%), and bone (18 %), still there are cases described with metastasis to the stomach and left gastric vein [11,18]. In up to 75% of the cases its etiology is unknown and no associated risk factors are found [17]. Nevertheless, it has been related with the exposure to thorium dioxide, polyvinyl chloride, arsenic and radium compounds, in- organic copper, anabolic steroids, and radiation [3-5, 8,19]. There is also an association with hemochromatosis and von Recklingh ausen disease [7,13]. Thorotrast was a radiologic contrast medium used in the US, Europe, and Japan from 1930s until the late 1950s [2,3]. It is a colloidal solution composed of 25% thorium dioxide (Th232) and dextrin [2,19]. After intra vascular injection, Th232 is stored in the reticulo-endo- thelial system, particularly the liver, spleen, and bone marro w [ 19]. Th232 is a radioactive isotope that emits α particles and it is the chronic α radiation the one responsible for the development of angiosarcoma [2,19]. The people af- fected have a mean latency of exposure to tumor of 24 - 42 years [3]. Vinyl chloride (VC) is a gas used in the production of plastic piping and conduit, floor covering, furniture, electrical applications, and packaging [3]. In 1974 in the US, the carcinogenicity of this compound was recog- nized, and since then the allowed exposure levels were reduced, reaching current levels of <1 ppm [2,3]. It is rapidly metabolized and it generates metabolites that react with the proteins, DNA and RNA, creating new mutations in K-ras and p53 [2,8]. The mean latency for vinyl-chloride-induced angiosarcoma is between 19 to 22 years [3]. The liver is a target of carcinogenesis from arsenic exposure [5]. Arsenic is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and the liver is the principal site for its detoxifica- tion [5]. Initially, it was used as a drug. Fowler’s solution (1% arsenic trioxide) was considered as part of the treatment for psoriasis, anemia, asthma, cholera, syphilis, among others [6]. Then, from 1931 until 1953, it was one of the first medications used for the management of chronic myelogenous leukemia [6]. Nowadays, Fowler’s solution, the consumption of contaminated water, and the exposure to pesticides made up of arsenic, have been reported as possible risk factors for angiosarcoma [4]. 4.1. Clinical Characteristics HAS is a tumor that is difficult to diagnose because of its nonspecific clinical presentation. Most of the cases are recognized in advanced stages, which makes this a poor prognosis disease and it has few therapeutic op- tions. Clinical presentation may be variable. The most com- mon initial symptoms are diffuse abdominal pain, asthe- nia, and weight loss [3,8]. Other systemic findings, like weakness and anorexia may be present in 25% - 50% of patients [4]. In a series of 5 patients reported by Molina and Hernandez, fever was documented as a presenting symptom in 2 patients for the first time. It is believed that the causes of this symptom are the hemorrhage and the necrosis related to the tumor [20]. Cases presenting as lower back pain, epigastric pain, abdominal discom- fort, hemoptysis, chest discomfort, and dyspnea have been described as well [4,10,12,20]. Physical signs in- clude ascites, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and jaundice [2,3,7]. Hemoperitoneum, due to the rupture of blood vessels or after instrumentation, happens in 17% to 27% of the cases and it is associated with a high morbidity and mortality [3]. Acute liver failure is a very unusual presentation of HAS [21]. This clinical syndrome is marked by en- cephalopathy and coagulopathy in a patient with no prior evidence of liver disease [7,22]. The most common causes for ALF are acetaminophen overdose (46%), drug toxicity (11%) and hepatitis (1 0%) [23 ]. In co ntrast, there are few case reports of infiltrative metastatic neoplasms affecting the liver that present as ALF, for example he- matological malignancies, adenocarcinoma, melanoma, anaplastic tumors, breast, colon, gastric, and lung cancer [7,13,24-26]. There are even fewer cases of primary liver cancer presenting as ALF [21]. In HAS, ALF is thought to be a consequence of the combination of ischemia of the parenchyma, portal vein occlusion by tumor thrombi, non-occlusive infarct due to septic shock or cardiogenic dysfunction, and the re- placement of the hepatocytes by malignant cells that lead to secondary necrosis [7,17]. 4.2. Laboratory and Radiologic Findings Laboratory data show elevation of liver enzymes with a predominance of cholestasis [8]. The most common finding is the increase of the alkaline phosphatase levels [2]. In more than 50% of the cases, thrombocytopenia and negative tumor markers are observed [3]. Also, cases of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia secondary to blood cell damage by passing through the tumoral vas- cular c h annels h a v e been reported [2]. From a radiologic point of view, it is difficult to dis- tinguish HAS from other hepatic tumors of mesenchymal or vascular origin [3,10]. Through imaging 4 growth patterns have been identi- fied: multiple nodules, solitary mass, mixed pattern with a dominant mass and multiple nodules, and infiltrative micronodular type [1,10]. In most cases it appears as multiple lesions or as a heterogeneous dominant mass [1, 2]. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  R. López et al. / Case Reports in Clinical Medicine 2 (2013) 439-444 443 In certain cases, abdominal X-rays show a mass in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) and thorium dioxide depos- its at the periphery of the liver [3]. The US may show a solitary mass or multiple nodules with different echo- genicity depending on the necrosis and the hemorrhage [2,3,17]. The various morphologic appearances on CT and mag- netic resonance explain why the differential diagnosis with other primary liver tumors is difficult [10]. In the CT scan without contrast, lesions are hypodense; how- ever, when contrast media are used multiple patterns of enhancing may be observed [3,9]. On the other hand, the magnetic resonance with contrast demonstrates the hem- orrhagic, heterogeneous and hypervascular characteris- tics of the dominant mass [1,2,27]. This image shows the different levels of attenuation in the arterial and portal phases [2]. 4.3. Pathologic Findings The final diagnosis is made with a histologic evalua- tion. This is a tumor of endothelial origin [20]. Macro- scopically, it is composed of brown-gray areas mixed with hemorrhagic foci and cavitations [17]. Microscopically it is characterized by the proliferation of neoplastic cells around preformed vascular channels: sinusoids, hepatic terminal venules and branches of the portal vein [17,27]. The growth of the sinuso ids is related to their dilation and atrophy of the hepatic cells [3]. The tumor nests are made up of epithelioid, spindle and pleo- morphic cells with small vascular spaces; mitotic figures are commonly seen [3,17]. In the solid areas, fibrosis and hemosiderin deposits may be found [1]. Areas of hemor- rhage, infarction, calcifications and necrosis can be seen as well [17]. The immunohistochemistry stains reveal the expression of: vimentin, CD31, CD34, Factor VIII and Ki67 [3,8,17]. 4.4. Treatment Treatment options for HAS are few and there are no established regimens due to the low frequency and rap- idly worsening course of the tumor [3,17]. Although complete resection is the best treatment, curative surgeries are difficult to perform. In most of the cases, by the time of diagnosis, the disease is in an ad- vanced state, presenting as a large tumor or with metas- tasis [3,17]. This neoplasm is radioresistant and no chemothera- peutic regimen has been established for its treatment [3,12]. Chemotherapy is palliative and is indicated for patients with HAS that cannot be resected [8,12]. In this case, the recommendation includes 5FU-carboplatin with doxorubicin or ifosfamide [12]. Liver transplantation is an absolute contraindication for the management of HAS [10]. In those patients who received a transplant, they did not show improvement in their survival and it is the hepatic neoplasm with the highest rate of recurrence after transplantation [1,7,8]. According to information of the European Liver Trans- plant Registry median survival after transplant is less than 7 m o n ths [10]. 5. CONCLUSIONS Hepatic angiosarcoma is a very infrequent tumor in patients younger than 35-year-old, and acute liver failur e is a very unusual presentation of this disease. This un- usual combination of clinical characteristics was part of the two cases we reported. Both patients had a progres- sively worsening clinical course and died within 2 months of diagnosis. This demonstrates the rapid evolu- tion, poor prognosis, and the need to find a therapy that improves survival. We would like to mention that we had another case of a young (26-year-old) female patient with a diagnosis of HAS. Her case was not included as part of the case re- ports because her disease presented as usual, with an insidious onset of diffuse abdominal pain and weight loss for 3 months. Additionally, she was being studied for a concomitant myeloproliferative disorder. Even though the clinical manifestations are nonspe- cific, one should think of HAS as part of the differential diagnosis when dealing with a young patient that has a worsening clinical course and a rapidly progressive liver disease. A diagnosis made soon, will make a difference in the treatment options, outcome and prognosis of these patients. REFERENCES [1] Maluf, D., Cotterel l, A., Cla rk, B., Stravitz, T., Kauffman, H.M., et al. (2005) Hepatic angiosarcoma and liver trans- plantation: Case report and literature review. Transplan- tation Proceedings, 37, 2195-2199. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.03.060 [2] Bioulac-Sage, P., Laumonier, H., Laurent, C., Blanc, J.F. and Balabaud, C. (2008) Benign and malignant vascular tumors of the liver in adults. Seminars in Liver Disease, 28, 302-314. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1085098 [3] Molina, E. and Hernandez, A. (2003) Clinical manifesta- tions of primary hepatic angiosarcoma. Digestive Dis- eases and Sciences, 48, 677-682. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022868221670 [4] N.-C. Huang, S.-R. Wann, H.-T. Chang, S.-L. Lin, J.-S. Wang, H.-R. Guo, et al. (2011) Arsenic, vinyl chloride, viral hepatitis, and hepatic angiosarcoma: A hospital- based study and review of literature in Taiwan. BMC Gastroenterology, 11, 142. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  R. López et al. / Case Reports in Clinical Medicine 2 (2013) 439-444 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 444 http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-11-142 [5] Liu, J. and Waalkes, M.P. (2008) Liver is a target of arse- nic carcino-genesis. Toxicological Sciences, 105, 24-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfn120 [6] Jolliffe, D.M. (1993) A history of the use of arsenicals in man. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 86, 287- 289. [7] Bhati, C.S., Bhatt, A.N., Starkey, G., Hubscher, S.G. and Bramhall, S.R. (2008) Acute liver failure due to primary angiosarcoma: A case report and review of literature. World Journal of Surgical Oncology, 6, 104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-6-104 [8] Egea, J., López, M., Pérez, F.J., Garre, C., Martínez, E., et al. (2009) Hepatic angiosarcoma. Presentation of two case s. Revista Espanola de Enfermedades Digestivas, 101, 430- 437. [9] Fulcher, A.S. and Sterling, R.K. (2002) Hepatic neo- plasms: Computed tomography and magnetic resonance features. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 34, 463- 471. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004836-200204000-00019 [10] Orlando, G., Adam, R., Mirza, D., Soderdahl, G., Porte, R.J., Paul, A., et al. (2012) Hepatic hemangiosarcoma: An absolute contraindication to liver transplantation—The European liver transplant registry experience. Transplan- tation, 95, 872-877. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/TP.0b013e318281b902 [11] Kim TO, Kim GH, Heo J, Kang DH, Song GA and Cho M. (2005) Metastasis of hepatic angiosarcoma to the sto- mach. Journal of Gastroenterology, 40, 1003-1004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00535-005-1665-1 [12] Kim, H.R., Rha, S.Y., Cheon, S.H., Roh, J.K., Park, Y.N., et al. (2009) Clinical features and treatment outcomes of advanced stage primary hepatic angiosarcoma. Annals of Oncology, 20, 780-787. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdn702 [13] Alexopoulou, A., Koskinas, J., Deutsch, M., Delladetsima, J., Kountouras, D., et al. (2006) Acute liver failure as the initial manifestation of hepatic infiltration by a solid tumor: Report of 5 cases and review of the literature. Tumori, 92, 354-357. [14] Bernardos, L., Garcia, A., Rey, C., Martin, J. and Turé- gano, F. (2008) Hepatic angiosarcoma. Revista Espanola de Enfermedades Digestivas, 100, 804-806. http://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1130-01082008001200017 [15] Deyrup, A.T., Miettinen, M., North, P.E., Khoury, J.D., Tighiouart, M., et al. (2009) Angiosarcomas arising in the viscera and soft tissue of children and young adults. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 33, 264-269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181875a5f [16] Geramizadeh, B., Safari, A., Bahador, A., Nikeghbalian, S., Salahi, H., Kazemi, K., et al. (2011) Hepatic angiosar- coma of childhood: a case report and review of literature. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 46, e9-e11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.09.005 [17] Granados-López, S.L., Gómez-Jiménez, L.M., Chávez- Bravo, N.C. and Sánchez-Rodríguez, C. (2012) Angio- sarcoma hepático idiopático. Informe de un caso. Revista Médica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 50, 445-448. [18] Nakayama, H., Masuda, H., Fukuzawa, M., Takayama, T. and Hemmi, A. (2004) Metastasis of hepatic angiosar- coma to the gastric vein. Journal of Gastroenterology, 39, 193-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00535-003-1274-9 [19] van Kampen, R.J., Erdkamp, F.L. and Peters, F.P. (2007) Thorium dioxide related haemangiosarcoma of the liver. The Netherlands Journal of Medicine, 65, 279-282. [20] Duan, X.F. and Li, Q. (2012) Primary hepatic angiosar- coma: A retro-spective analysis of 6 cases. Journal of Digestive Diseases, 13, 381-385. http:/ /d x.doi.org/10 .1111/j.1751-2980.2012.00600.x [21] Baumhoer, D., Lorf, T., Gunawan, B., Ar mbrust, T., Füzesi, L., et al. (2005) Hepatic tumorigenesis in acute hepatic failure. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepa- tology, 17, 1125-1130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00042737-200510000-00019 [22] Lee, W.M. (2012) Recent developments in acute liver failure. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroente- rology, 26, 3-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2012.01.014 [23] Lee, W.M., Squires Jr., R.H., Nyberg, S.L., Doo, E., Hoofnagle, J.H. (2008) Acute liver failure: Summary of a workshop. Hepatology, 47, 1401-1415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hep.22177 [24] Hanamornroongruang, S. and Sangchay, N. (2013) Acute liver failure associated with diffuse liver infiltration by metastatic breast carcinoma: A case report. Oncology Letters, 5, 1250-1252. [25] Miyaaki H, Ichikawa T, Taura N, Yamashima M, Arai H, Obata Y, et al. (201) Diffuse liver metastasis of small cell lung cancer causing marked hepatomegaly and fulminant hepatic failure. Internal Medicine, 49, 1383-1386. http://dx.doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3296 [26] Rowbotham, D., Wendon, J. and Williams, R. (1998) Acute liver failure secondary to hepatic infiltration: A single centre experience of 18 cases. Gut, 42, 576-580. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.42.4.576 [27] Yang, K.F., Leow, V.M., Hasnan, M.N. and Subramaniam, M.K. (2012) Primary hepatic angiosarcoma: Difficulty in clinical radiological, and pathological diagnosis. Medical Journal of Malaysia, 67, 127-128.

|