Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

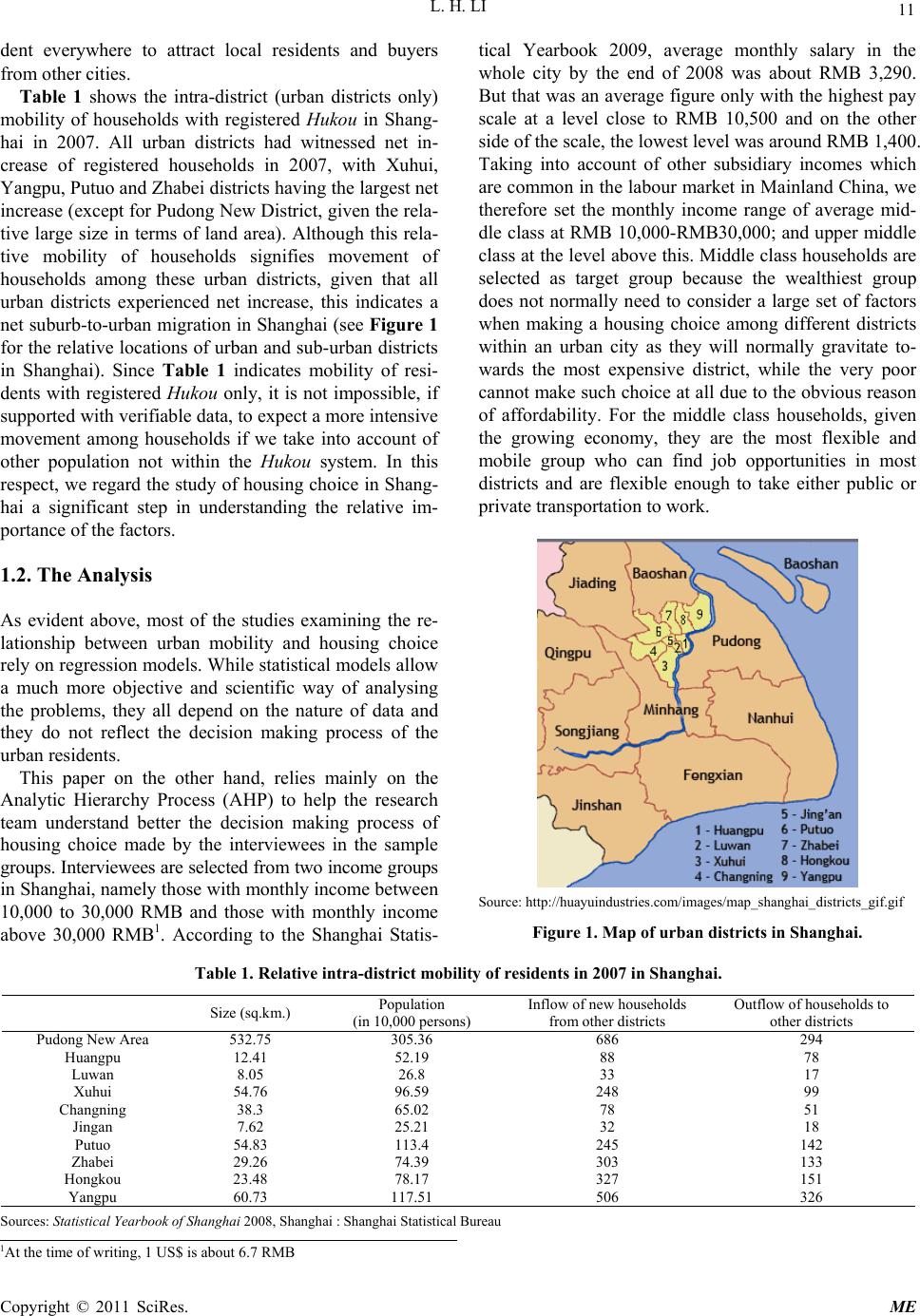

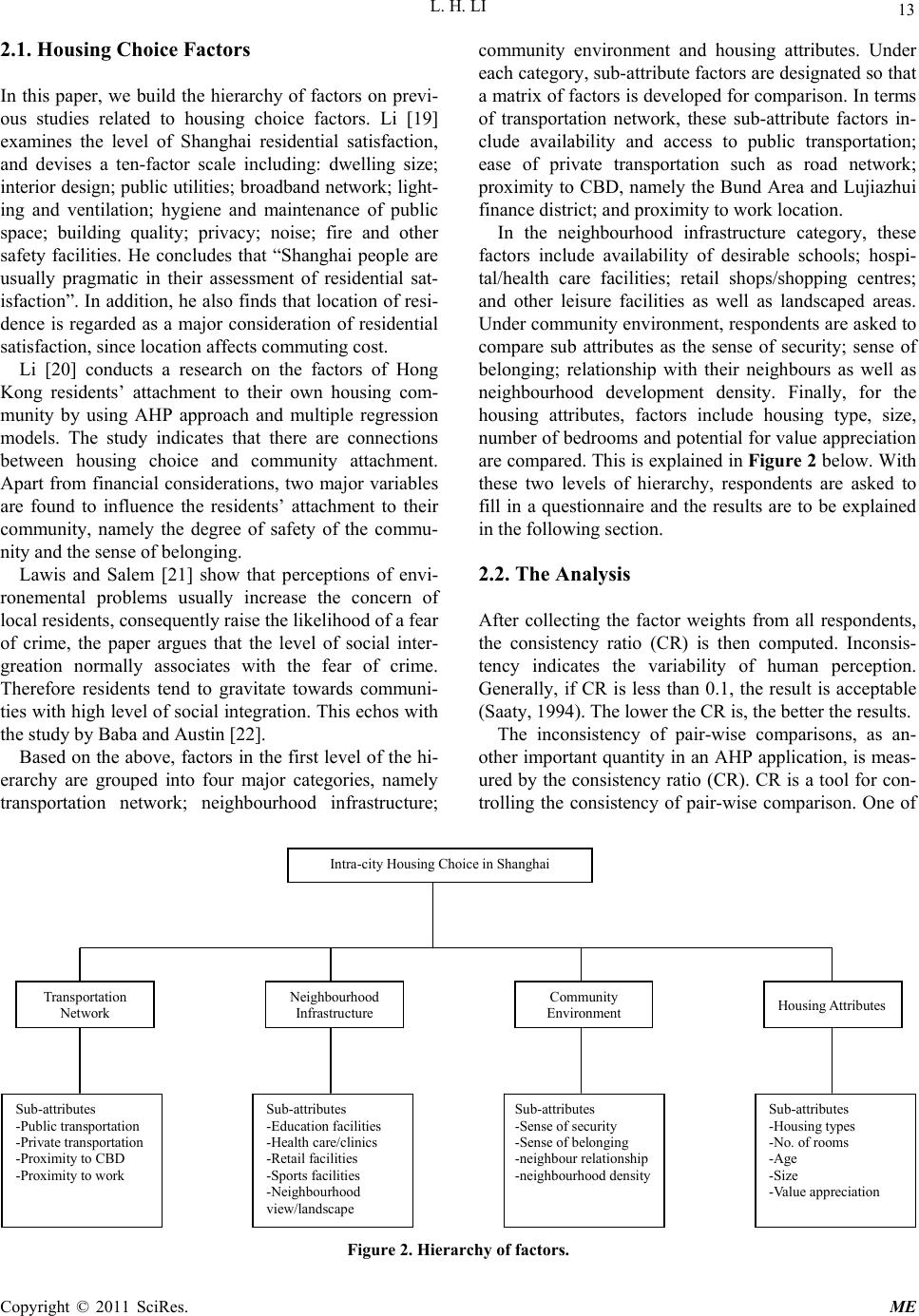

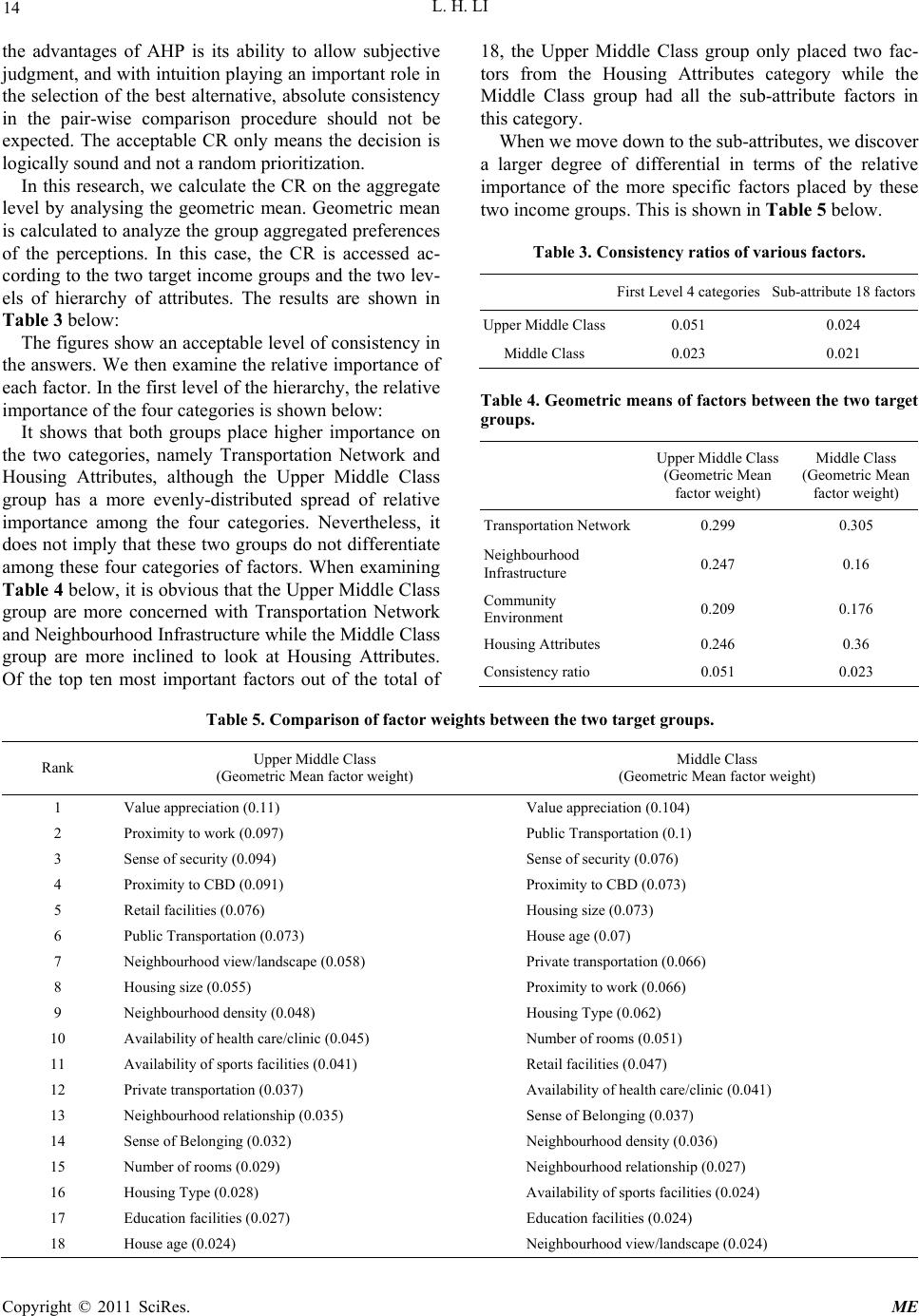

Modern Economy, 2011, 2, 9-17 doi:10.4236/me.2011.21002 Published Online February 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME Housing Choice in an Affluent Shanghai – Decision Process of Middle Class Shanghai Residents Linghin Li Department of Real Estate and Construction, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China E-mail: lhli@hku.hk Received August 29, 2010; revised September 10, 2010; accepted Se pt em ber 20, 2010 Abstract While most papers on housing choice concentrate on relatively disadvantaged groups in the society con- strained by financial ability, this paper looks at the affluent population in Shanghai. In examining their own perception of the relative importance of difference factors affecting such choice by way of an Analytical Hi- erarchy Process, we are able to understand that currently, most affluent households still regard proximity to the city centre as an important factor when making housing choice. More importantly, there seems to be a marked difference in the ranking of these factors between the upper middle class and the average middle class in this city. Our analysis shows that the upper middle class households place more importance on the transportation network and neighbourhood infrastructure, while the average middle class have more concern on the housing attributes. Keywords: Housing Choice, Housing Market, Shanghai 1. Introduction Housing market is a very unique market in the sense that it can be simply defined as a market for a simple com- modity, namely domestic housing unit, with a very wide price range. In this way, it may not be entirely different from other commodity markets such as motor cars or clothing. On the other hand, it can be completely segre- gated into very different segments in accordan ce with the household’s socio-economic background (or collectively known as affordability); tenure modes (purchase and rental); physical design (such as multi-level apartments and detached houses) and geographical sub-markets. Housing choice therefore can be deciphered from very different perspectives based on different research focus, such as aging society [1]; housing choice and race [2] as well as housing choice and senior citizens [3]. Housing choice attracts academic attention because there is a certain social element attached to the study of the market mechanism for this real asset. Housing in- variably means shelter for most people, especially for the lower working class in most societies. Housing also represents a core element in human settlement. Owusu [4] for example finds that new immigrants from Ghana to Canada tend to choose sub-urban areas to settle down. In addition, they tend to concentrate within certain nei- ghbourhood and even residential apartments, due to mainly affordability. Jones, et al. [5] examine the rela- tionship between mobility and housing sub-markets in Glasgow. They express doubts on standard hedonic models in examining such situation and instead advocate the use of case-study based migration analysis to under- stand such relationship as well as the dynamics of local housing market better. Colom and Molés [6] look at housing choice (in terms of tenure choice and size of dwelling) in Spain in the decade before year 2000 and find that housing choice changes in response to changes in social, economic and demographic factors such as age, education and income level. Based on Self-Congruity theory, Sirgy, et al. [7] explain the personal factors that may be specific to dif- ferent individuals such as experience, involvement and time pressure often play an important role in housing choice decision. Moreover, they also note that psycho- logical factor such as occupant’s image affects home- buyer’s evaluation process, which coupled with other factors shape the final housing choice. Because of the growing importance of the personal factors in the whole housing choice literature, this paper intends to examine further this aspect by investigating the “perception” of major factors when middle class households in Shanghai, China are contemplating intra-urban housing choice de-  L. H. LI Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 10 cisions. 1.1. Housing Choice in China Over the last decades, substantial literature has been de- voted to the analysis of residents’ mobility and housing tenure. In the recent years, with the emergence of more data and analytical tools, more structured analyses have been carried out on the correlation between intra-urban mobility and housing choice. In addition, China with its immense economic growth and vast urban development also attracts academic interests in exploring such issue in this country. This is almost a natural progression in re- search agenda as residents’ mobility is more or less posi- tively correlated with the econo mic growth. Li and Siu’s [8] study is one of the first few atte mpts to try this angle by linking residential mobility in Chinese cities to the way housing provision is structured under market transi- tion. Li [9] finds that work unit and the housing bureau act as the major determinant in relocating residents to urban fringe. Moreover, he also finds that during the housing reform period in China, whether the housing is subsidized or not also influence significantly the direc- tion of move. Wu [10] examines intra-urban mobility in Shanghai and Beijing and finds that mobility is not driven by the need for tenure or amenity. Based on a regression analy- sis, Wu concludes that job opportunities account for a major reason for such mob ility incentive and institution al barriers such as Hukou (or household qualifications) con- tinue to pose as problems for most of the intra-urban movers who do not possess skills or capital. In this re- spect, Wu’s analysis pays relatively less emphasis on the factor of mobility of those who do possess skills and capital. Zheng, et al. [11] find that in China, a majority of households face three obstacles in making housing choice decisions, namely blurred or incomplete property rights leading to problems in reselling their own hous e; limited access to housing finance and mortgage facilities; and mis-match between the job-market and housing-market locations. They therefore conclude that to remove hin- drances, individual households and the government need to target at these three prob lems, such as providing more land for higher-density housing development. Liu, et al. [12] examine the housing affordability issue in Beijing, China and conclude that with the rapid economic devel- opment, housing prices increase more substantially than income level leading to an increasing gap of housing affordability. Con sequently, either the government has to provide financial assistance or rental sector remains a major source of housing choice for the majority of households. As mentioned above, this paper intends to investigate the issue of intra-urban housing choice in Shanghai by examining the perception of the elative importance of different factors affecting housing choice decisions among middle class households in this city. Middle class households are being examined as this group possesses a relatively better financial position to actually make a “choice”. As such, this paper does not aim at examining the problem of affordability but rather the issue of mak- ing housing choice at will and how households who can make a choice perceive the factors affecting this decision making process. We assume that the target group in the study has a larger degree of flexibility of choice and hence they tend to look at a broader set of housing at- tributes when making a housing choice. But we need to emphasize that affordability remains an important ele- ment for all levels of households as there are always housing products beyond the reach of a certain social group. This paper is therefore trying to fill the gap that while most of the literature concentrates on affordability in housing choice, we need to look at a wider spectrum of factors in order to understand how these various fac- tors are being weighed by households who are able to make a choice-based decision that is not limited entirely by affordability. This paper also hopes to contribute to this discussion of intra-urban mobility among different districts within a major metropolitan in China, namely Shanghai. In limit- ing the housing choice analysis within the same urban city, it helps to understand the more realistic housing choice factors facing most households. By focusing on the same urban city boundary, respondents in the analy- sis can actually relate to the issues more easily and hence provide a better-informed input into the dataset as these households will not need to hypothesize the conse- quences of finding a new job and school; losing family and social ties; as well as cultural and climatic differ- ences when considering housing choice in other parts of the country. Since this paper aims at analysing the “per- ception” of the relative importance of various factors, the thought process of conjuring up these “perceptions” needs to be realistic enough. Shanghai as the growth engine in the current Chinese economy has received substantial attention in the aca- demic world, especially in relation to its urban and housing development [13-15]. Within the current urban districts in Shanghai, Pudong New Area is the largest in terms of land area. While Huangpu is the traditional CBD of Shanghai, other urban districts also become more and more popular due to the active effort of various district governments in the decentralisation process of urban development [16]. As such, new residential pro- jects with high standard of development details are evi-  L. H. LI Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 11 dent everywhere to attract local residents and buyers from other cities. Table 1 shows the intra-district (urban districts only) mobility of households with registered Hukou in Shang- hai in 2007. All urban districts had witnessed net in- crease of registered households in 2007, with Xuhui, Yangpu, Putuo and Zhabei districts having the largest net increase (except for Pudong New District, given the rela- tive large size in terms of land area). Although this rela- tive mobility of households signifies movement of households among these urban districts, given that all urban districts experienced net increase, this indicates a net suburb-to-urban migration in Shanghai (see Figure 1 for the relative location s of urban and sub-urban districts in Shanghai). Since Table 1 indicates mobility of resi- dents with registered Hukou only, it is not impossible, if supported with verifiab le d ata, to expect a mo re in tens ive movement among households if we take into account of other population not within the Hukou system. In this respect, we regard the study of housing choice in Shang- hai a significant step in understanding the relative im- portance of the factors. 1.2. The Analysis As evident above, most of the studies examining the re- lationship between urban mobility and housing choice rely on regression models. While statistical models allow a much more objective and scientific way of analysing the problems, they all depend on the nature of data and they do not reflect the decision making process of the urban residents. This paper on the other hand, relies mainly on the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to help the research team understand better the decision making process of housing choice made by the interviewees in the sample groups. Interviewees are selected from two income groups in Shanghai, namely those with monthly income between 10,000 to 30,000 RMB and those with monthly income above 30,000 RMB1. According to the Shanghai Statis- tical Yearbook 2009, average monthly salary in the whole city by the end of 2008 was about RMB 3,290. But that was an averag e figure only with the highest pay scale at a level close to RMB 10,500 and on the other side of the scale, the lowest level was aro und RMB 1,400 . Taking into account of other subsidiary incomes which are common in the labour market in Main land China, we therefore set the monthly income range of average mid- dle class at RMB 10,000-RMB30,000; and upper middle class at the level above this. Middle class households are selected as target group because the wealthiest group does not normally need to consider a large set of factors when making a housing choice among different districts within an urban city as they will normally gravitate to- wards the most expensive district, while the very poor cannot make such choice at all due to the obvious reason of affordability. For the middle class households, given the growing economy, they are the most flexible and mobile group who can find job opportunities in most districts and are flexible enough to take either public or private transportation to work. Source: http://huayuindustries.com/images/map_shanghai_distric ts_gif.gif Figure 1. Map of urban districts in Shanghai. Table 1. Relative intra-district mobility of residents in 2007 in Shanghai. Size (sq.km.) Population (in 10,000 persons) Inflow of new households from other districts Outflow of households to other districts Pudong New Area 532.75 305.36 686 294 Huangpu 12.41 52.19 88 78 Luwan 8.05 26.8 33 17 Xuhui 54.76 96.59 248 99 Changning 38.3 65.02 78 51 Jingan 7.62 25.21 32 18 Putuo 54.83 113.4 245 142 Zhabei 29.26 74.39 303 133 Hongkou 23.48 78.17 327 151 Yangpu 60.73 117.51 506 326 Sources: Statistical Yearb ook of Shan ghai 2008, Shanghai : Shanghai Statistical Bureau 1At the time of writing, 1 US$ is about 6.7 RMB  L. H. LI Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 12 AHP can be characterized as a multi-criteria decision technique in which qualitative factors are of prime of importance. A model of the problem is developed using a hierarchical representation. At the top of the hierarchy is the overall goal or prime objective one is seeking to ful- fill. In this project, it is the housing choice among dif- ferent urban districts in Shanghai. The succeeding lower levels then represent the progressive decomposition of the problem. The knowledgeable parties complete a pair- wise comparison of all entries in each level relative to each of the entries in the next higher level of the hierar- chy. The composition of these judgments fixes the rela- tive priority of the entities at the lowest level relative to achieving the top-most objective. AHP has been adopted widely in the an alysis of situa- tions in which decision-makers face different choices with a set of interrelated attributes. Housing choice therefore falls into this category of situation naturally. Ball and Srinivasan [17] present a model of housing se- lection process using the AHP, which allows buyers to consistently evaluate property attributes. Schniederjans et al. [18] also present a Goal Programming model that utilizes the AHP to evalu ate property attributes and make an optimal house selection decision. The AHP addresses complex problems on their own terms of interaction. It allows people to lay out a problem as they see it in its complexity and to refine its definition and structure through iteration. To identify critical prob- lems, to define their structure, and to locate and resolve conflicts, the AHP calls for information and judgments from several participants in the process. Through a mathematical sequence it synthesizes their judgments into an overall estimate of the relative priorities of alter- native courses of action. The priorities yielded by the AHP are the basic units used in all types of analysis; for example, they can serve as guidelines for allocating re- sources or as probabilities in making predictions. AHP enables decision makers to represent the simul- taneous interaction of many factors in complex, unstruc- tured situations. It helps them to identify and set priori- ties on the basis of their objectives and their knowledge and experience of each problem. Normally, consumers’ feelings and intuitive judgments are probably more rep- resentative of their thinking and behavior than are their verbalizations of them. AHP determines the priority any alternative has rela- tive to the overall problem of the issue. The analyst/user creates a model of the problem by developing a hierar- chical decomposition representation. At the top of the hierarchy is the overall goal or prime objective one is seeking to fulfill. The succeeding lower levels then rep- resent the progressive decomposition of the problem. The analyst completes a pair-wise comparison of all the elements in each level relative to each of the program elements in the next higher level of the hierarchy. The composition of these elements fixes the relative priority of elements in the lowest level (usually solution alterna- tives) relative to achieving the top-most objective. The following four steps are used to solve a problem with the AHP methodology: Build a decision “hierarchy” by breaking the gen- eral problem into individual criteria. Gather relational data for the decision criteria and alternatives and encode using the AHP relational scale. Estimate the relative priorities (weights) of the de- cision criteria and alternatives. Perform a composition of priorities for the criteria which gives the rank of the alternatives (usually lowest level of hierarchy) relative to the top-most objective. 2. Data In the summer of 2009, we carried out questionnaire surveys with 30 identified middle class respondents, all of them work in the service industry or professional fields. 14 of them have a monthly income above 30,000 RMB (the Upper Middle Class Group) and 16 of them have a monthly income of 10,000 to 30,000 RMB (the Middle Class Group). The size of the sample looks small but given the nature of the questionnaire, almost each respondent was interviewed individually with a detailed explanation of pair-wise comparison given to them pre- ceding the filling in of the questionnaire. Pair-wise comparison is the cornerstone of the AHP philosophy and allows the user to systematically deter- mine the intensities of interrelationships of a great num- ber of decision factors. Respondents are asked to indicate their preference of these factors and categories, which means they need to indicate which one of the two cate- gories or factors is more important than the other, and then indicate the extent of the difference in importance. When making the pair-wise comparison, the respondent has to first choose which attribute is more important or has greater influence in the hierarchy. Secondly, the re- spondent decides the intensity of that importance. The intensity assessment is translated to a given scale. In this research, a five-point scale is used. The adapted scale is shown in Table 2. Table 2. Scale of preference on built environment attributes used in this survey. Degree of Importance Definition 1 Equal Importance 2 Slightly more importance 3 Moderate importance 4 Strong importance 5 Absolute importance  L. H. LI Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 13 2.1. Housing Choice Factors In this paper, we build the hierarchy of factors on previ- ous studies related to housing choice factors. Li [19] examines the level of Shanghai residential satisfaction, and devises a ten-factor scale including: dwelling size; interior design ; public utilities; broadband network ; light- ing and ventilation; hygiene and maintenance of public space; building quality; privacy; noise; fire and other safety facilities. He concludes that “Shanghai people are usually pragmatic in their assessment of residential sat- isfaction”. In addition, he also finds that location of resi- dence is regarded as a major consideration of residential satisfaction, since location affects commuting cost. Li [20] conducts a research on the factors of Hong Kong residents’ attachment to their own housing com- munity by using AHP approach and multiple regression models. The study indicates that there are connections between housing choice and community attachment. Apart from financial considerations, two major variables are found to influence the residents’ attachment to their community, namely the degree of safety of the commu- nity and the sense of belonging. Lawis and Salem [21] show that perceptions of envi- ronemental problems usually increase the concern of local residents, consequently raise the likelihood of a fear of crime, the paper argues that the level of social inter- greation normally associates with the fear of crime. Therefore residents tend to gravitate towards communi- ties with high level of social integration. This echos with the study by Baba and Austin [22]. Based on the above, factors in the first level of the hi- erarchy are grouped into four major categories, namely transportation network; neighbourhood infrastructure; community environment and housing attributes. Under each category, sub-attribute factors are designated so that a matrix of factors is developed for comparison. In terms of transportation network, these sub-attribute factors in- clude availability and access to public transportation; ease of private transportation such as road network; proximity to CBD, namely the Bund Area and Lujiazhui finance district; and proximity to work location. In the neighbourhood infrastructure category, these factors include availability of desirable schools; hospi- tal/health care facilities; retail shops/shopping centres; and other leisure facilities as well as landscaped areas. Under community environment, respondents are asked to compare sub attributes as the sense of security; sense of belonging; relationship with their neighbours as well as neighbourhood development density. Finally, for the housing attributes, factors include housing type, size, number of bedrooms and po tential for value appreciation are compared. This is explained in Figure 2 below. With these two levels of hierarchy, respondents are asked to fill in a questionnaire and the results are to be explained in the following section. 2.2. The Analysis After collecting the factor weights from all respondents, the consistency ratio (CR) is then computed. Inconsis- tency indicates the variability of human perception. Generally, if CR is less than 0.1, the result is acceptable (Saaty, 1994). The lower the CR is, the better the results. The inconsistency of pair-wise comparisons, as an- other important quantity in an AHP application, is meas- ured by the consistency ratio (CR). CR is a tool for con- trolling the consistency of pair-wise comparison. One of Intra-city Housing Choice in Shanghai Community Environment Neighbourhood Infrastructure T ransportation Network Sub-attributes -Public transportation -Private transportation -Proximity to CB D -Proximity to work Sub-attributes -Educat i on facilities -Health care/clinics -Retail facilities -Sports facilities -Neighbourhood view/landscape Sub-attributes -Sense of security -Sens e of belonging -neighbour relationship -neighbo urho od density Housing Attributes Sub-attributes -Housi ng t ypes -No. of rooms -Age -Size -Va lu e appreciation Figure 2. Hierarchy of factors.  L. H. LI Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 14 the advantages of AHP is its ability to allow subjective judgment, and with intuition playin g an important role in the selection of the best alternative, absolute consistency in the pair-wise comparison procedure should not be expected. The acceptable CR only means the decision is logically sound and not a random prioritization. In this research, we calculate the CR on the aggregate level by analysing the geometric mean. Geometric mean is calculated to analyze the group aggregated preferences of the perceptions. In this case, the CR is accessed ac- cording to the two target in come groups and the two lev - els of hierarchy of attributes. The results are shown in Table 3 below: The figures show an acceptable level of consistency in the answers. We then examine th e relative importance of each factor. In the first level of the hierarchy, the relative importance of the four categories is shown below: It shows that both groups place higher importance on the two categories, namely Transportation Network and Housing Attributes, although the Upper Middle Class group has a more evenly-distributed spread of relative importance among the four categories. Nevertheless, it does not imply that these two groups do not differentiate among these four categories of factors. When examining Table 4 below, it is obvious that the Upper Middle Class group are more concerned with Transportation Network and Neighbourhood Infrastructure while the Middle Class group are more inclined to look at Housing Attributes. Of the top ten most important factors out of the total of 18, the Upper Middle Class group only placed two fac- tors from the Housing Attributes category while the Middle Class group had all the sub-attribute factors in this category. When we move down to the sub-att ri but es, we discover a larger degree of differential in terms of the relative importance of the more specific factors placed by these two income groups. This is shown in Table 5 belo w. Table 3. Consistency ratios of various factors. First Level 4 cate gories Sub-attribute 18 factors Upper Middle Class0.051 0.024 Middle Class 0.023 0.021 Table 4. Geometric means of factors between the two target groups. Upper Middle Class (Geometric Mean factor weight) Middle Class (Geometric Mean factor weight) Transportation Network0.299 0.305 Neighbourhood Infrastructure 0.247 0.16 Community Environment 0.209 0.176 Housing Attributes 0.246 0.36 Consistency ratio 0.051 0.023 Table 5. Comparison of factor weights between the two target groups. Rank Upper Middle Class (Geometric Mean factor weight) Middle Class (Geometric Mean factor weight) 1 Value appreciation (0.11) Value appreciation (0.104) 2 Proximity to work (0.097) Public Transportation (0.1) 3 Sense of security (0.094) Sense of security (0.076) 4 Proximity to CBD (0.091) Proximity to CBD (0.073) 5 Retail facilities (0.076) Housing size (0.073) 6 Public Transportation (0.073) House age (0.07) 7 Neighbourhood view/landscape (0.058) Private transportation (0.066) 8 Housing size (0.055) Proximity to work (0.066) 9 Neighbourhood density (0.048) Housing Type (0.062) 10 Availability of health care/clinic (0.045) Number of rooms (0.051) 11 Availability of sports facilities (0.041) Retail facilities (0.047) 12 Private transpo rtation (0.037) Availability of health care/clinic (0.041) 13 Neighbourhood relationshi p (0.035) Sense of Belonging (0.037) 14 Sense of Belonging (0.032) Neighbourhood density (0.036) 15 Number of r ooms (0.029) Neighbourhood relationship (0.027) 16 Housing Typ e (0.028) Availability of sports facilities (0.024) 17 Education facilitie s (0.027) Education facilities (0.024) 18 House age (0.024) Neighbourhood view/landscape (0.024)  L. H. LI Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 15 As expected, housing choice is a very specific and personal decision to be made by all families, to the extent that it can even be idiosyncratic. Therefore, we do not find any significant differences between the two target groups in terms of the broadly-defined “categories” of attributes. Statistically, most people will therefore not be able to provide a logical explanation of their perception of the relative importance of these broadly-defined terms. It is only when these categories are further sub-divided into more specific factors are respond ents able to config- ure more meaningful choice. In this stage, differences between the two income groups in the overall affluent population become more conspicuous and significant. Having said that, we find that all middle class (probably all other) households are majorly and equally concerned with capital appreciation prospect of their housing choice. This is understandable as capital appreciation prospect of housing is basically the aggregate effect of all other fac- tors affecting popularity of housing units. For other factors, differences in housing choice per- ception between the two target groups begin to show. First of all, the second most influential factor the Upper Middle Class have considered is “Proximity to work” while the Middle Class Group ranked “Public Transpor- tation” as the second factor. While the two factors weight more or less the same in each group, the implication is that Upper Middle Class group would more likely be clustering around commercial districts while the Middle Class Group would have a much wider choice of housing location along the very extensive underground network as well as the ring road system in Shanghai. This is also reflected in Rank number 4 of both groups. While both groups placed “Proximity to CBD” as number four factor, the factor weights differ by more than 20%. Similarly, the two target groups both ranked the factor “sense of security” as number three on the list, but the degree of importance in Upper Middle Class apparently outweighed Middle Class again by more than 20%. Further more, we also notice that the factor of the availability of retail facilities was given a much higher weighting by the Upper Middle Class group than the Middle Class Group. This represents cultural differences between these two groups. It is apparent that higher in- come households place higher importance on shopping experience in their daily life because of higher afforda- bility and relatively more luxurious lifestyle. Such im- portance also echoes with their need to be near to the CBD where most high-end retail facilities will b e found. On the other hand, while we will expect car ownership ratio is relatively higher among Upper Middle Class households within the affluent population, they did not place the factor of Private Transportation in a higher rank. In fact, judging from the factor weight, the importance of this factor to the Middle Class outweighs that of the Up- per Middle Class by more than eighty percent. One pos- sible explanation is the relative higher degree of impor- tance of the factor “proximity to CBD” to this group such that relative travelling time to workplace and other activities is not a major concern to them. On the other hand, given the more dispersed pattern of housing choice manifested by the Middle Class group, travelling time is a core factor in their daily activities and hence both pub- lic and private transportation networks are important. A further observation is noted from the two sub-at- tribute factors, namely Neighbourhood View/Landscape and Neighbourhood Density. These two factors ranked 7th and 9th respectively in the Upper Middle Class’ per- ception, while they only ranked 14th and the last one among the Middle Class group. This significant differ- ence represents the importance of “neighbourhood” to higher income households as a representation of their socio-economic status. To this group, their perception of a good housing choice goes beyo nd the ph ysical qu alities of the housing itself into the community environment that they can enjoy. Similar to their western counter-part, they would seek neighbourhood with better landscape planning and lower density. However, one may find a certain contradiction here as no ticed from above that this group of households also prefer city centre than the pe- ripheral. 3. Conclusions Housing choice is normally associated with the degree of affordability. Most of the studies on housing choice therefore examine how certain groups in the society make that choice under financial constraints. When a target group in the society is not entirely constrained by affordability, their perception of the relative importance of a wide range of factors represents a more thorough analysis of the “choice” issue. In this paper, we examine the “perception” of the relative importance of 18 factors under 4 categories of attributes in housing choice deci- sion from the perspective of the relatively affluent households in Shanghai. We target at this middle class population as they are the group who would consider both affordability and other environmental attributes with more or less equal importance in making housing choice. We find that the relatively affluent households in Shanghai are still clus tering around the urban centre as a housing location close to the CBD and their workplace is more important than the other factors. This reflects the current of traffic congestion problem in the city centre that leads to the affluent class’ unwillingness to move to sub-urban districts, just like their western counter-parts.  L. H. LI Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 16 On the other hand, to this group of population, social identity and aesthetic factor of the neighbourhood are also important so that it is not unforeseeable that with improved road system and other infrastructure networks, an outward migration to lower density communities with better landscape features will be witnessed, especially towards the Pudong New District. But that will not hap- pen shortly. On the other hand, the ordinary middle class in Shanghai exhibits a higher degree of flexibility in terms of housing choice. Their reliance on public tran spor tation , especially the underground railway system, allows them to have a wider choice in most districts, given the highly- development underground railway system in the city. It is therefore expected that more and more new communi- ties or redevelopment projects will be resulted along the different stations on the underground railway system that target at this income group, where new housing units with larger flats can be found. Given that this affluent population (in general) actu- ally has the financial and economic ability to move within the different urban districts in Shanghai, we find that middle class households in this city still regard proximity to the CBD and transportation network as im- portant consideration when making a housing choice. The differences in the two income groups within this middle class population represent more on their focus of daily necessity to commute t o work and shop rather th an their difference in financial ability in affording a decent house. The results of this paper have important implica- tion on the future urbanisation process as well as housing market development in Shanghai. 4. References [1] W. A. V. Clark and A. M. C. Deurloo, “Aging in Place and Housing Over-Consumption,” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, Dordrecht, September 2006, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 315-335. [2] N. Denton, “The Geography of Opportunity: Race and Housing Choice in Metropolitan America,” Contempo- rary Sociology, Vol. 36, No. 2, March 2007, pp. 135-136. doi:10.1177/009430610603600210 [3] K. E. Lahey, M. L. Newman and D. Kim, “Housing Choices and Mortgage Financing Options for Seniors,” Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, May- ugust 2006, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 103-119. [4] T.Y. Owusu, “Residential Patterns and Housing Choices of Ghanaian Immigrants in Toronto, Canada,” Housing Studies, Vol. 14, No. 1, 1999, p. 77-98. doi:10.1080/02673039983019 [5] C. Jones, C. Leishman and C. Watkins, “Intra-Urban Migration and Housing Submarkets: Theory and Evi- dence,” Housing Studies, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2004, pp. 269- 283. doi:10.1080/0267303032000168630 [6] M. Consuelo Colom and M. Cruz Molés, “Comparative Analysis of the Social, Demographic and Economic Fac- tors that Influenced Housing Choices in Spain in 1990 and 2000,” Urban Studies, Vol. 45, No. 4, 2008, pp. 917-941. doi:10.1177/0042098007088474 [7] M. J. Sirgy, S. Grzeskowiak and C. Su, “Explaining Housing Preference and Choice: The Role of Self-Con- gruity and Functional Congruity,” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, Vol. 20, No. 4, 2005, pp. 329- 347. doi:10.1007/s10901-005-9020-7 [8] S. M. Li and Y. M. Siu, “Residential Mobility and Urban Restructuring under Market Transition: Study of Guang- zhou, China,” Professional Geographer, May 2001, Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 219-229. doi:10.1111/0033-0124.00281 [9] S. Li, “Housing Tenure and Residential Mobility in Ur- ban China: A Study of Commodity Housing Develop- ment in Beijing and Guangzhou,” Urban Affairs Review, Vol. 38, No. 4, 2003, pp. 510-534. doi:10.1177/1078087402250360 [10] W. P. Wu, “Migrant Intra-Urban Residential Mobility in Urban China,” Housing Studies, Vol. 21, No. 5, 2006, pp. 745-765. doi:10.1080/02673030600807506 [11] S. Q. Zheng, Y. M. Fu and H. Y. Liu, “Housing-Choice Hindrances and Urban Spatial Structure: Evidence from Matched Location and Location-Preference Data in Chi- nese Cities,” Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 60, No. 3, 2006, pp. 535-557. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2006.05.003 [12] M. Liu, R. Reed and H. Wu, “Challenges Facing Housing Affordability in Beijing in the Twenty-First Century,” International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2008, pp. 275-287. doi:10.1108/17538270810895114 [13] S. Chen and K. Karwan, “Innovative Cities in China: Lessons from Pudong New District, Zhangjiang High Tech Park and SMIC Village,” Innovation: Management, Policy & Practice, Vol. 10, No. 2-3, 2008, pp. 247-256. [14] Y. R. Yang and C. H. Chang, “An Urban Regeneration Regime in China: A Case Study of Urban Redevelopment in Shanghai’s Taipingqiao Area,” Urban Studies, 2007. Vol. 44, No. 9, pp. 1809-1826. doi:10.1080/00420980701507787 [15] J. M. Zhu, “From Land Use Right to land Development Right: Institutional Change in China’s Urban Develop- ment,” Urban Studies, Vol. 41, No. 7, 2004, pp. 1249- 1269. doi:10.1080/0042098042000214770 [16] T. W. Zhang, “Decentralization, Localization, and the Emergence of a Quasi-participatory Decision-Making Structure in Urban Development in Shanghai,” Interna- tional Plann i n g S t udies, Vol. 7, No. 4, 2002, pp. 303-323. doi:10.1080/1356347022000027738 [17] J. N. Ball and V. C. Srinivasan, “Using the Analytic Hi- erarchy Process in House Selection,” Journal of Real Es- tate Finance & Economics, Vol. 9, No. 1, 1994, pp. 69- 85. doi:10.1007/BF01153589 [18] M. J. Schniederjans, J. J. Hoffman and G. S. Sirmans “Using Goal Programming and the Analytic Hierarchy Process in House Selection,” The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, Vol. 11, No. 2, 1995, pp. 167-  L. H. LI Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 17 176. doi:10.1007/BF01098660 [19] S. M. Li, Y. L. Song and N. Chiang, “Displacement, Housing Conditions and Residential Satisfaction: An Analysis of Shanghai Residents,” The Centre for China Urban and Regional Studies, Occasional Paper, Vol. 78, August 2007, pp. 1-24. [20] L. H. Li, “Community Attachment and Housing Choice in Hong Kong,” Property Management, 2009, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 42-57. doi:10.1108/02637470910932665 [21] D. A. Lawis and G. Salem, “Community Crime Preven- tion: An Analysis of a Developing Strategy,” Crime and Delinquency, Vol. 27, No. 3, July 1981, pp. 405-421. doi:10.1177/001112878102700307 [22] Y. Baba and M. D. Austin, “Neighborhood Environ- mental Satisfaction, Victimization, and Social Participa- tion as Determinants of Perceived Neighborhood Safety,” Environment and Behavior, Vol. 21, No. 6, 1989, pp. 763-780. doi:10.1177/0013916589216006 |