Modern Economy, 2013, 4, 696-705 Published Online November 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/me) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/me.2013.411075 Open Access ME Further Thoughts on Strategic Trade Policy under Asymmetric Information Chung Yuan Fu*, Shirley J. Ho Department of Economics National Chengchi University, Taiwan Email: *fu.chungyuan@gmail.com, sjho@nccu.edu.tw Received July 3, 2013; revised August 1, 2013; accepted August 9, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Chung Yuan Fu, Shirley J. Ho. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT We study the informational impacts of multilateral voluntary export restraints (henceforth VERs) in an international trade model with differentiated products [1]. We first show that with competing mechanisms, the two firms’ lying in- tentions are strategic complements and will increase with the degree of product differentiation. Next, we show that each government will design their VERs menus to allow for only partial revelation. Contrary to the single intervention case [2], a separating equilibrium where each country’s domestic firm truthfully reveals its private information does not exist under multilateral policy interventions. Finally, we demonstrate that trade retaliation, when the two governments’ VERs are positively related, will happen when the government believes that its domestic firm is more likely to be inefficient. Keywords: Strategic Trade Policy; Voluntary Export Restraints; Partial Information Revelation 1. Introduction It is now well known that government intervention can shift rents by providing a strategic advantage to the do- mestic firm. In particular, the pioneering work by Bran- der and Spencer [3] showed that under Cournot competi- tion, an export subsidy enables the domestic firm to be a Stackelberg leader, and thus it increases the domestic welfare at the expense of the foreign firm. Subsequently, Eaton and Grossman [4] demonstrated that the optimal policy will be an export tax, when the domestic firm competes with a foreign firm in prices1. This indicates that the type of export policy is sensitive to the form of competition. In addition, the literature has also noticed that information can also crucial in determining the ap- propriate policy. For example, Wong [5] demonstrated that in the Brander-Spencer model with asymmetric in- formation (about cost), the optimal export subsidy scheme derived from the full information case is no longer incentive compatible. Collie and Hviid [6] and Qiu [2] examined the use of strategic trade policy as a signalling device when the informational asymmetry is between domestic and foreign firms. With incomplete information, the Principal-Agent model can best describe the leader-follower relation be- tween uninformed government and informed firm. By applying the Revelation Principle, the uninformed gov- ernment can adopt a direct mechanism by offering a menu of policies and letting the informed domestic firm self-select the intended policy. When domestic firm is competing with foreign firms, this “self-selection” proc- ess becomes more informative. In Qiu’s [2] words, “it is a mix of screening and signalling problems”; by choos- ing among the menu of policies, the domestic firm also signals its private information to the rival firms [6]. The task of the government is then to trade off between the inefficiency from asymmetric information and the strate- gic advantage from trade policy; whether to have the informed domestic firm truly reveal its information, or to hide and enjoy the strategic benefit from asymmetric information? Qiu [2] showed that under Cournot compe- tition the uniformed government will choose a policy menu to truly reveal its cost information (separating equilibrium). *Corresponding author. 1De Meza [7] considered cost asymmetry between firms and shows that the countries with the lowest costs provide the highest export subsidies. Allowing a social cost of public funds that exceeds unity, Neary [8] similarly found that non-concavity of demand is a sufficient condition for the government to provide more subsidies to the more cost competi- tive firm. Bandyopadhyay [9] found the conventional result in De Meza [7] and Neary [8] is reversed for inelastic demand. While the analysis on unilateral policy intervention has proved to be powerful to describe the dilemma encoun- tered by the uninformed government, in reality we often  C. Y. FU, S. J. HO 697 see bilateral or multilateral policy interventions instead of unilateral policy. If we adopt a direct mechanism for these multiple contracting cases, will there be a separat- ing equilibrium? If not, how much information can be revealed? How does the degree of information revelation relate to the market structure? Will there be trade retalia- tion? In this paper, we provide answers to these questions by studying an incomplete information VERs game in an intra-industry trade model. The model we consider is an international trade model with differentiated products [1]. There are two countries and each country has only one producer, which sells its products to two countries. In order to capture intra-industry trade of this kind, we em- ploy the differentiated product framework by Dixit [10] and Singh and Vives [11]. There are three reasons to study an incomplete information VERs game of this form. First, there have been many discussions on the informa- tional impacts of taxes, subsidies or tariffs; we hope to complement the literature by investigating the informa- tional impacts of VERs, which are seen as equally im- portant strategic tools. Second, although we are aware that both the choice of policy instrument and the degree of information revelation can be sensitive to the form of competition (Cournot or Bertrand), since our focus is on the information aspects of multilateral interventions, we adopt a quantity competition setup to better handle the impacts from VERs. Third and most interestingly, we will show that in the complete information benchmark case, each govern- ment’s VER decision is as efficient as in the single gov- ernment case. There is no direct interaction between the two governments, so the policy efficiency can be retained even with bilateral interventions. The question of con- cern is: now that there is no game between the two gov- ernments, can we apply the revelation principle directly and look for a truth-telling direct mechanism in the in- complete information VERs game? Unfortunately, the answer is no, as we will demonstrate that the “signaling effect” of menu selection will change the rival firm’s per- ception about domestic firm’s private information. Con- sequently, each firm’s intention of information revelation will be related to the rival firm’s intention, and thus the two governments are no longer “independent” from each other. Our paper starts with the complete information bench- mark case, where we show that, by using VER each gov- ernment gains a first mover advantage in the rival coun- try [12-14]. However, when considering incomplete in- formation, we first demonstrate that with competing mechanisms, each firm’s intention to lie is positively related to the rival firm’s lying intention. The two firms’ lying intentions are strategic complements and will in- crease with the degree of product differentiation. Impor- tantly, we show that each government will design their VERs menus to allow for only partial revelation. Con- trary to the single intervention case [2], a separating equilibrium where each country’s domestic firm truth- fully reveals its private information does not exist with multilateral policy interventions. Finally, we demonstrate that trade retaliation, when the two governments’ VERs are positively related, will happen when the government believes that its domestic firm is more likely to be ineffi- cient. This result partly reflects the result by Martina and Vergoted [15], who discussed the role of retaliation in trade agreements and showed that retaliation is a neces- sary feature of any efficient equilibrium. The issues on “competing mechanisms” have received many discussions. Peck [16] and Martimort and Stole [17] first illustrated apparent failures of the standard revela- tion principle with competing mechanisms. Since there is no obvious way to deal with these problems, the litera- ture has responded by imposing ad hoc restrictions on the set of mechanisms from which Principals can choose [18-22]. This is the reason why we stick to direct mecha- nisms in this current paper. Next, our paper investigates ex-post information revelation under bilateral govern- ment interventions. This is different from ex-ante infor- mation revelation such as Creane and Miyagiwa [23], where duopoly firms make their revelation decisions be- fore they observe their own private information. From the information content, our model is closed to Collie and Hviid [6] and Qiu [2], but they mainly assumed uni- lateral policy design. Brainard and Martimort [21] con- sidered bilateral government interventions but restricted to truth-telling equilibria2. Finally, our results conclude that trade retaliation happens when the government be- lieves that its domestic firm is more likely to be ineffi- cient. This partly coincides with Martina and Vergoted’s [15] results. They showed that in the presence of private information, retaliation can always be used to increase the welfare derived from such agreements by the partici- pating governments. In particular, it is shown that retalia- tion is a necessary feature of any efficient equilibrium. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the complete information VERs game as a benchmark of comparison. We demonstrate that, by using VER, each government gains a first mover advan- tage in the rival country. Section 3 characterizes the equi- librium in the incomplete information VERs game. In equilibrium, each government will only implement par- tial revelation from its domestic firm, and there can be trade retaliation when the government believes that its 2Brainard and Martimort [21] restricted to truth revelation equilibrium, because Myerson [24] showed that in a bilateral principal-agent struc- ture, truth revelation will be an equilibrium, if each agent is associated uniquely with one principal. In our model, each firm will be related to oth governments, and hence truthful revelation does not constitute an equilibrium. Open Access ME  C. Y. FU, S. J. HO 698 domestic firm is more likely to be inefficient. Section 4 concludes the paper with some suggestions on further re- search. 2. The Model Specifically, let the superscript , index the two countries. Country ’s demand for firm 1 and firm 2’s products are given by 1, 2k k 11 kk pq 2 k q , 21 kk pq 2 k q , where subscript ,indexes firm . and denote firm i’s price and output in country k. The coefficients i1, 2,iik i pk i q and denote the own price effect and cross price effects, respectively. We assume to reflect that the own price effect is higher than the cross effects. Notice that the level of can be seen as a mea- sure for the substitution between the two products; When 0 the two products are almost homogenous; when the two products are almost differentiated. The reason we have considered a quantity instead of price competition model is because we can handle the quantity restraints easily. We are aware that the form of competitionmight changes the policy insights [4]. Since our focus is on the informational impacts of VERs, we will stick to this simple framework for a neat presenta- tion. Finally, since our focus is on the informational im- pacts of government interventions, we assume zero transportation cost for simplification. Each firm’s mar- ginal production is assumed to be . i Each firm’s profit is thus given by c πi π,1, ij ij iiiiii RRcqq i 2, ij where i and i denote firm ’s revenue in domestic and foreign countries, respectively. ii ii Rpqjj ii Rpq i i j We consider that the government of each country will choose a VER , to maximize social welfare i. Each country’s social welfare is the overall utility deducted by foreign firm’s revenue, added by domestic firm’s revenue in the foreign country, and minus the do- mestic firm’s total production cost. That is, , j i qi j SW , for1,2,and. ij ij iijiiii SWURRc qqiij This setup is firstly given by Singh and Vives [11], which assumed that 22 2 ijiii i iiii ijj Uqqqqqqi 2,.j The advantage of this setup is: since in differentiated product models, we cannot use the area under demand function to measure the consumer surplus. The setup of can help us easily measure the consumer surplus. Also, we can easily derive the country ’s demand func- tion by partial differentiating with respect to . i U i 1 1 1 2 i U 1 2 i i q Complete Information VERs Game As a benchmark of comparison, Section 2 discusses the complete information VERs game where both firms’ production costs are publicly known. We will show that, under complete information, each government’s VER decision will be as efficient as in the single government case. However, this policy efficiency will disappear when we consider incomplete information in Section 3. Not only because there is information rent in the VERs contract, but also because the two governments’ compet- ing mechanisms will increase firms’ strategic incentives to lie. The complete information VERs game proceeds as follows. First, government 1 and government 2 set their VERs, , and simultaneously. After observing the VER decisions, both firm 1 and firm 2 compete in the product markets of the two countries. By backward in- duction, we first solve the market equilibrium, given the two governments’ VER decisions, and then determine each government’s optimal VER. 2 1 q1 2 q Market Equilibrium Given the two governments’ VER decisions, and firm 1 and firm 2 maxi- mize their profits simultaneously. 2 1 q1 2 q 1 1 12 2 111 1 max π, q RRcqq 2 2 12 2 222 2 max π. q RRcqq Each firm’s best reply to the rival government’s VER is given by 12 22 q 12 211 2 12 and . qc qc q (1) Optimal VERs Now, given the two firms’ best replies in (1), each government chooses its VER to maximize its social welfare. In the case of country 1, the structural form of is: 1 SW 22 11111 2 22 11 qq 1 1121 2 111 12 2 2 12 1 1 . 2 SWqqqq qq qqq qc c q 1 2 1 1 22 q From the first order condition of maximization: 2 12 11 2 1 0 2 SWc qc q 3.Therefore 3The second order condition of maximization is satisfied. Open Access ME  C. Y. FU, S. J. HO 699 2 11 12 2 qc 2 c (2) Similarly, we can calculate government 2’s optimal VER: 1 22 12 2 qc 1 . c We will later refer 2 1 q and 1 2 q as the efficient VERs, as each government’s VER decision is as efficient as in the single government case. Accordingly, substitute , j i qi j, into firms’ best re- plies in (1), we have 11 1 32 4 cc q 2 and 221 2 32 . 4 cc q Here we make two remarks on these efficient VERs. First, we can compare j i q to the outputs in the free trade case, where each firm choose both and to maximize i i q , j i qi j,i . The free trade outputs in domestic and foreign markets are 2 3 ij i i cc q and 2 3 ij i i cc q , respectively. A direct comparison shows that The VER is higher than the foreign output in the free trade case. The advantage of using VER is that, by pre-committing to j i q, the government gains the po- sition of a leader in the rival country, and in output com- petition, there will be a first mover advantage. This strategic advantage is first mentioned by Harris [12], who analyzed the impacts of VERs in a Bertrand model. Rosendorff [25] explained why governments pre- fer VERs to tariff in a Cournot model. Also, Ishikawa [26] studied the effect of VERs on profit, market share, consumer surplus and welfare in a Cournot model. Berry, et al. [27] evaluated VERs that was initially placed on automobiles exports from Japan in 1980’s. They found that VERs had increased both prices and the profits of domestic firms, while leaving consumer welfare worse off. Feenstra and Lewis [28] considered a domestic gov- ernment with political pressure to negotiate over the volume of trade and the transfer of rents. They charac- terized the globally optimal, incentive-compatible trade policies, in which the domestic government has no in- centive to overstate (or understate) the pressure for pro- tection. De Santis [14] studied the impact of VERs on exporting countries. He showed that VERs at the free-trade level would favour the concentration of indus- try, and raise the price mark-up in the domestic market. However, the impact on welfare is indeterminate de- pending upon the effect on global efficiency. Second, j i q in (2) tells us something about the moti- vation of mimicking. Notice that j i q is decreasing in i, and this indicates that a more efficient firm will have a higher VER. In particular, if i has two possible values: c c c and c with L cc, then we have jH jL ii qc qc. This, however, does not imply that the less efficient firm will mimic the efficient firm. Ac- tually, since i is concave in , and by the definition of maximization, the less efficient firm j i q H c is better off choosing jH qc i than choosing jL i qc c . In the words of Spence [29], the inefficient firm does not envy the efficient firm. This means that when we consider incomplete information in a unilateral intervention case, a separating equilibrium where each type of i chooses its intended VER j ii qc i might exist. Hence, our model would suggest the same result as Qiu [2] in the unilateral intervention case. In the next section, we will show that with multiple mechanisms, a separating equilibrium does not exist. 3. Incomplete Information VERs Game Section 3 discusses the incomplete information VERs game where i c is only privately known by firm . Neither government nor government i or firm knows this value. To simplify the analysis, we assume a binary type set, , LH ccc i with L cc. We have shown that with complete information, each government’s VER decision is as efficient as in the sin- gle government case. There is no direct interaction be- tween the two governments, so the policy efficiency can be retained even with bilateral interventions. With in- complete information, we will show that the “signaling effect” of menu selection will change the rival firm’s perception about domestic firm’s private information. Consequently, each firm’s intention of information reve- lation will be related to the rival firm’s intention, and the two governments are no longer “independent” from each other. The incomplete information VERs game proceeds as follows. First, each government announces a VERs i menu jH i qc c , jL i qc independently. Second, each firm self selects a VER from the menu, and this choice is publicly observed. Third, according to the ob- served policy choices, the two firms update their beliefs about the rival firm’s production cost, and then compete in the product markets of the two countries. By backward induction, we first solve the market equilibrium given the two firms’ menu selection. Then we characterize the two firms’ menu selection equilibrium. Finally, we determine each government’s VERs menu. i Before proceeding with the derivation of market equi- librium, we define more notations for the prior and pos- terior beliefs on i. First, as said, we assume that , LH i ccc is only privately known by firm i. All other players (including government , government i , and firm ) have common prior beliefs that the prob- Open Access ME  C. Y. FU, S. J. HO 700 ability for c is , 01 and the probability for c is 1 j . After observing the rival firm’s menu se- lection strategy, each firm i can update its belief on . , j ci Let , L i qc H i ,, jL ii denote firm i’s selection strat- egy from the menu . It is assumed that for . That is, in , jLj i qc qc jH i qc i H i L H ii ji , the selection strategy for type c of firm i is , and for type L qc 1 L i j H i qc Lj ii c of firm , it is i 1 jL i H i 1, LH ii j i qc H ii qc . In particular, 1, L 0 H ii denotes the separating strategy where each type of firm selects its intended VER. As an- other example, i denotes the hybrid strategy where type c of firm i selects its intended VER, while type c of firm i randomly selects be- tween jL qc i and jH i qc with a probability i . 3.1. Market Equilibrium Belief Updating We now solve the market equilibrium given the two firms’ menu selection. After observing firm ’s selection strategy, firm i can update its belief on i. That is, according to the Bayes’ rule, given the observation c i , the on-equilibrium path belief is given by: 1 L i LH ii i (3) For simplification, we assume that the off-equilibrium path belief will be the same as the prior . If H ii then it can be calculated that i . In particular, for the separating strategy ii , we have 1, L 0 H1 i 1, . As another example, for the hybrid strategy LH iii , we have 1 i L i ii LH and 1 i . Finally, given the posterior belief i , let i 1 ii H c i Ec c denote firm ’s posterior expected cost. i Market Competition Let j ii q denote country ’s VER associated with selection strategy i i . Since each firm’s profit will be affected by their selection strategies, we rewrite the profits as , where 12 ,, 11 ,π1,2 1 ii ci ,, 22 21 22 2 21111 1 , Eqq qq q 111 1 12 11 1 cq cq q π (4) 11 1 2122122 22 22 211 12 22 22 π,, . cqqq qEq q cq q 2 2 (5) In the case of 112 π,, i c , there is an expected term 1 22 Eq . The reason for the expectation form is because firm 1 cannot observe 2 c, and by observing 2 , firm 1 will guess firm 2’sVER as: 11 2222 2 1 22 1 111 LHL LH Eqq c qc 2 . H Given 222 , LH , the probability that type c of firm 2 takes 1 2 qc is 2 , and the probability that type c of firm 2 takes 1 2 qc is 2 . So the ex- pected probability of taking 1 2 qc is 2 12 H . The expected probability of taking 2 1 qc can be explained similarly. In the product market, each firm chooses to maximize i i q 12 π,, i c i , given the selection strategy 12 , . Notice that ,qi j ii , will be determined by the menu selection strategy. By the first order condi- tion of maximization4, we have j 12 22 111 2 12 12 and . 22 EqcEq c qq (6) This is similar to (1) in the complete information case, except that the expected VERs will be determined in the menu selection game. Substitute the two best replies in (6) to (4) and (5), we can rewrite 12 π,, ii c as: 2 22 1 221 1121 2 112 2 11 1 221 2 11 π,, 2 2 , 2 Eq c c qEc q Eq c cq 1 (7) 1 22 2 11 2 2122 1 221 1 22 2 1121 22 π,, 2 2 . 2 Eqc c qEc q Eq c cq 2 (8) 4The second order condition of maximization is satisfied. Open Access ME  C. Y. FU, S. J. HO Open Access ME 701 In the case of , notice that there is a posterior expected cost term . From (6), we know 1121 ,,c 2 E 2 c useful for equilibrium characterization. Lemma 1 10 i i Ec that firm 2’s best reply is 2 Eq11 2 2 c . But since Proof. Since 10 iHL i Ec cc and 2 10 11 i ii , we have firm 1 cannot observe 2, it can only use the observation of c 2 to update its belief to be 22 2 1 2 H c c Ec . The similar argument ap- plies to firm 2. 3.2. Menu Selection 1 2 10 11 iHL ii Ec cc .■ First, recall that in the complete information case, we conclude that type c is better off choosing jH i qc than jL i qc. In the unilateral intervention case, a sepa- rating equilibrium where each type of i chooses its intended VER c jH qc i might exist. Hence, to simplify the discussion, we restrict the selection strategy to be , LH iii Next, we derive the equilibrium selection strategies 12 , 1, 2i , given the best replies in (6). That is, for and , H i ccc, firm i maximizes 12i with respect to ,,c i i . In the case of firm 1, after replacing 1, ii , in (7) is re- written as (see Equation (11) ): 21 ,,c 1, ii . That is, we assume that type c will take the intended VER, while type c might mimic type c b H y taking a mixed strategy ii i i. With this restriction, 1 jL qc j qc 0 i will indicate the separating strategy where each type chooses its intended VER, and 1 i denotes the pool- ing strategy where both types c and c choose jL i qc. 11 In 1 1, 1 , type c will take the intended VER, and type cwill mimic type c by taking a mixed strategy 22 1 11 1 1 H qc qc . So in (11), we have replaced 2 11 q in (7) by 2 1 qc . Also in (12), we have replaced 2 q11 in (7) by 2 1 12 111 H qc c qc . Also, we have replaced 22 and E 1 2 Eq 2 with the definitions given in (9) and (10). The similar argument applies to firm 2. (7) and (8) can be rewritten accordingly. 1 E n be written as i c ca Selection Equilibrium Given the announced VERs 11, 1. 11 ii LH i H i Ec cc cc H L c (9) menu , jL jH ii qc qc, 12 , will constitute a Bayesian equilibrium iff for 1, 2,i 12 max, ,for,. i H iii cccc and 1 j ii Eq can be rewritten as 11 11 jj ii ii jH ii Eqq c qc L (10) We need to show that for , 1, 2i1 L i and i H i can maximize 12 ,, ii c for , H c i cc 1 L , respectively. First, from (11), if we require 1 to be best reply for type c, the intended VER must be set at the following level Lemma 1 concludes a preliminary result which will be 2 2 2 12 221 2 2 112 1 1 22 2 1 π,, 22 , 2 LL L L LL EqcqcE c cq Eq c cqc c (11) 2 2 2 1 22 112 22 111 1222 111 1 1 22 22 111 1 π,, 2 1 1 2 1. 2 H H LH L H HLH Eq c c qcqcEc qc qc Eq c cqcqc H (12)  C. Y. FU, S. J. HO 702 2 2 1 12 2 LL qcc Ec 2 , (13) which is obtained by differentiating (11) with respect to 2 1 qc . In other words, if 2 1 qs set to be (13), then c 11 L will be best reply. Next, for type c, 11 H needs to be best reply to 2 1, 2 . That is, given 2 , the first order condition of maximization for (12) is: i 2 112 22 222 111 111 1 222 1111 2 22 11 22 11 π,, 2 2 . H LH HLH HLH LH HL H cqc qcqcqc qc qcqc qcEc qc qc cqc qc Let 22 11 1 LH Bqcqc , firm 1’s best reply is: 2 2H 12 1 1 22 . 2 qc B (14) Similarly, we can calculate firm 2’s best reply to H c Ec 11 1, : 1 1 2 2 2 22 , 2 HH qcc Ec B 1 (15) where 11 22 2 LH Bqcqc . Notice that i is re- lated to j through the term j E qu c . The eilibrium 12 , s to simultaneously sa need tisfy (14) and (15). r, since the structure forms of equilibrium 12 , Howeve are complicated, we derive the following properthe menu selection equilibrium. First, from (14), it can be calculated that ties on 22 1 21 2 2 12 1 2 1 10. 211 HL Ec B cc B A similar argument on 2 also shows that 2 1 0 . This indicates that 1 and 2 are strategic comple- ments. Since the level of i denotes the degree that type c of firm i will miic type m c the more that type c of firm i lies will trigger c type of the rival firm to lie more. Next, recall that the level of measures the degree of substitution, and the smaller indicates a higher degree of product differentiation. If we take the partial differentiation of 1 2 with respect to , we know that the degree of strategic complements is positively related to the degree of product differentiation. Lemma 2 1 and 2 are strategic complements, and 1 2 is decreasing in . Second, it is interesting to know if t he separating equi- librium exists. That is, in the case of firm 1, we ask if 10 is a best reply to 20 in (14). To find out, substitute 20 in (14), so we have 22 Ecc and s best reply in (14) be firm 1’comes 2 1 1 22 2 HL qcc c . Th B e only chance for 10 is to let 2 1 12 2 HL qcc c Compare this level to the efficient VER 1 2 2 2 H cc c . We can conc 2 1 1 qlude that if 2 cc , these two values are identical, but if 2 cc, 2 1 q is higher. In other words, the efficien d t VERs can ly whenindeeinduce a truth-telling equilibrium but on 2 cc . More interestingly, if we consider an arbitrary positive 2 , the VER for (14) to be zero is: level of 22 2 1 2H HcEc qc 2 Also recall 2 1 qc from (13). We theore have the m ref enu ,qc e truth, no words, given the 22LH 11 qc , which will induce each type of m 1 to tell th matter what the rival will do. In fir other menu 22 11 , LH qcqc , the dominant strategy for each type of firm 1 is to tell the truth and pick the intended VER. Lemma 3 1) Given the menu 22 11 , LH qcqc , the dominant strategy for each type of firm 1 is to tell the 2) The efficient V truth and pick the intended VER. ERs can indeed induce a truth-telling equilibrium but only when 2 cc . In the incomplete information VERs game, the “sig- Open Access ME  C. Y. FU, S. J. HO 703 naling oeffect”f menu selection will change the rival fir ary results. m’s perception about domestic firm’s private informa- tion. Consequently, each firm’s intention of information revelation will be related to the rival firm’s intention. The question of concern is whether the government will find it optimal to induce truthtelling, no matter how the rival firms might lie. Will it be better off for the govern- ment to induce a certain degree of lying in equilibrium? How will this degree relate to the market structure? We will provide answers to these questions shortly in next subsection. Finally, it can be calculated from (14) for the follow- ing prelimin Lemma 4 1 2H qc 1 0 and 10 . ed in Figur creasinAs illustrate 1, ing 2 1 H qc will shift the best reply of 1 inward. When 2 1 H qc l move in- creases, the menu selection equilibrium wilfrom 0 E to 1 E. Since 1 and 2 are strategple- ments, this indicates that both 1 ic com and 2 will de- se. Next, crea 10 indicates that th smalle er is, the m best reore theply of 1 will shift outward. In other words, when the two pructs become more differenti-od ated, the more likely that type c will lie. Intuitively, when the two products are more differentiated, each firm will hope to increase their actual eport to counteract the demand reduction from a smaller x . Since we are re- stricting 22 11 LH qc qc, type c of each firm has more intention to lie and hence 1 becomes higher. 3.3. Equilibrium VERs Given the market equilibriu tion equilibrium determined m in (6) and the menu selec- by (14) and (15), we now 0 0 2 1 2 λ 1 20 11 2 11 0, 0 H qc 2 121 ,H qc 1 λ 2 Figure 1. Increasing 2 1H qc shifts the best replies left- ward. nment e simplified the discussion by restrict the selection determine each gover’s menu of VERs. As said, we hav strategy , LH iii to be 1, ii . In the case of firm 1, according to the discussion on menu selection, if we require 11 L to be best type reply for c, the intended VER must be set at the following level 22 2 1 2. 2 L LcEc qc (16) The same argument can apply to firm left with the determination on 2. Hence we are jL i qc. As mentioned in Lemma 3 that the menu 22 11 , LH qcqc (from (13) and (16)) can induce 10 folevel of 2 r any . The question of concern is wheent will find it optimal to induce truth-telling from its own frm, no matter how the rival firms might lie. To answer the question, we first calculate the first or der condition of maximization: ther trnmhe gove i 0 i jH i qc . In the EW case of firm 1, recall 11 SW c from Section 2: 11 111 22 iiii SW cUcRc qq 1 11111 1 12112 2 12 12 2111111 22 . ij ij j c R qqqqq q RcRccqq c The expected social welfare is: 11 1 1 LH EWSW cSWc fo f . Since the structural or the detailed deri- rms are complicated, we omitted vation of i jH i qc. Then, by applying the implicit EW5 function theorem, we can calculate jH i qc of which can tell us wether the two policies are strategic iH j qc, the sign complements or substitutes. Finally, we check whether it is dominant for government 1 to choose 22 11 , LH qcqc , such that 10 . The same argu- ment can apply to firm 2. Proposition 5 2 1 H qc and 1 2 qc are strategic complements for * , and they are strategic substi- tutes for * . Recall from Le2 and 4 that 1 mma and 2 are strategic m compleents and 0 i jH i qc 5 . Proposition e strategic rsays that the key to judge thelation between 2 1 H qc 1 2 qc and is the size of prior belief . In the case of government 1, if she thinks that the domestic more likely to be efficient (i.e ., * firm is ),hen when government 2 increases 1 2 t qc , the best reply of 5Detailed derivations are available upon request. Open Access ME  C. Y. FU, S. J. HO 704 2 will shift inward. Since 1 and 2 are strategic complements, the equilibrium 12 , will both de- ase. Now, if cre 2 1 H qc decreases, thethe best reply of 2 n will shift outward, which cuse the equilib- rium 1 ould ca to increer than decrease. Ctrarily, if government 1 thinks the domestic firm is more likely to have ase rath on c (i.e., * ), then it is better to allure the type c of the rival firm to lie less. To do so, when governmentncrease 2 is 1 2 qc and move the best reply of 2 rd, government 1 must also in- crease inwa 2 1 H qc and move the bef 1 st reply o inward to decrease bothf 1 o and 2 in equilibrium. MartVergoted [15] discussed the role of re- taliation in trade agements. They showed that ina and re in the presence of private information, retaliation can always be used to increase the welfare derived from such agree- ments by the participating governments. In particular, it is shown that retaliation is a necessary feature of any ef- ficient equilibrium. Our results show that retaliation can only happen when * . Proposition 6 Given any level of j , it is optimal for the government to ienmplemt 0 i . eIn the case of firm 1, to see wheth it is optimal for government 1 to choose r 22 11 q (from (13) , LH qcc 0 and (15)) to implement 1 , we substitute 2 1 qc and 2 1 H qc into the first order condition i H qc . In j EW i the Appendix, we show that 0 jH i qc i EW VERs menu under the 22 , LH qcqc 6oncavity of i EW , we can conce optimal 11 lude t . Due c to the hat th 2 1 H qc must smaller than be 2 1 H qc . By Lemmsince a 2, 1 20 H qc , we cade that givenany level of 1 2 n conclu , it is optimal for government 1 to implement 1 . Concluding Remarksss 4. We study the informational impa untary export restraints in a he cts oltilateral vol- teroges version of sms, the two firms’ lying intentions are stra- te -industry trade model, for both an ENCES [1] H. H. Wang, Ciffication and Wel- fare in a Diffe World Economy, f mu nou Brander and Krugman’s [30] international trade model. Similar to the unilateral intervention case such as Qiu [2] and Collie and Hviid [6], we ask if separating equilib- rium where each country’s domestic firm truthfully re- veals its private information still exists. If not, how much information can be revealed? How does information revelation relate to market structure? Will there be trade retaliation? To these questions, we first showed that with compet- ing mechani gic complements and will increase with the degree of product differentiation. Next, we showed that each gov- ernment will design their VERs menus to allow for only partial revelation. Contrary to the single intervention case [2], a separating equilibrium where each country’s do- mestic firm truthfully reveals its private information does not exist with multilateral interventions. Finally, we demonstrated that trade retaliation, when the two gov- ernments’ VERs are positively related, will happen when the government believes that its domestic firm is more likely to be inefficient. As mentioned, we have restricted our discussion on the VERs game to an intra alytical convenience and for complementation to the literature. It is also interesting to extend our model to dis- cuss other policy instruments such as subsidies or taxes, and in another form of competition such as Cournot and Bertrand models. The literature has shown that the type of export policy is sensitive to the form of competition. In the case of subsidies or taxes, the informational im- pacts will not be as surprising as in VERs game, as the two governments are already related to each other with complete information. We will leave these interesting issues for further research. REFER . Peng and H. Wu, “Tar erentiated Duopoly,” Th Vol. 36, No. 7, 2013, pp. 899-911. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-1996(94)90007-8 [2] L. D. Qiu, “Optimal Strategic Trade metric Information,” Journal of International Eco Policy under Asym- nomics, Interna- Vol. 36, No. 3-4, 1994, pp. 333-354. [3] J. A. Brander and B. J. Spencer, “Export Subsidies and International Market Share Rivalry,” Journal of tional Economics, Vol. 18, No. 1-2, 1985, pp. 83-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-1996(85)90006-6 [4] J. Eaton, and G. Grossman, “Optimal Trade and Industri Policy under Oligopoly,” Quarterly Journal of Econo al mics, Vol. 101, No. 2, 1986, pp. 383-406. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1891121 [5] K. Wong, “Incentive Incompatible, Im Subsidies,” University of Washing miserizing Export ton Discussion Paper ss,” Scandinavian Journal of Economics, No. 9020, 1990. [6] D. R. Collie and M. Hviid, “Export Subsidies as Signals of Competitivene Vol. 95, No. 3, 1993, pp. 327-339. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3440359 [7] D. De Meza, “Export Subsidies an Cause or Effect,” Canadian Journa d High Productivity: l of Economics, Vol. 19, No. 2, 1986, pp. 347-350. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/135289 [8] J. P. Neary, “Cost Asymmetries in International Subsidy 6Detailed derivations are available upon request. Open Access ME  C. Y. FU, S. J. HO Open Access ME 705 p Winners or Losers?”Games: Should Governments Hel Journal of International Economics, Vol. 37, No. 3-4, 1994, pp. 197-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-1996(94)90045-0 [9] S. Bandyopadhyay, “Dema and Strategic Trade Policy,” Journal of Internation nd Elasticities, Asymmetry al Eco- nomics, Vol. 42, No. 1-2, 1997, pp. 167-177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(96)01453-5 [10] A. Dixit, “A Model of Duopoly Suggesting a Entry Barriers,” Bell Journal of Economics, Vol. 1 Theory of 0, No. 1, 1979, pp. 20-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3003317 [11] N. Singh and X. Vives, “Price and Quantity Competition in a Differentiated Duopoly,” The RAND Journal of Eco- nomics, Vol. 15, No. 4, 1984, pp. 546-554. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2555525 [12] R. Harris, “Why Voluntary Export Restraints tary’,” The Canadian Journal of Ec Are ‘Volun- onomics, Vol. 18, No. 4, 1985, pp. 799-809. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/135091 [13] C. C. Mai and H. H. W straints Are Voluntary: An Extensi ang, “Why Voluntary Export Re- on,” The Canadian Jou- rnal of Economics, Vol. 21, No. 4, 1988, pp. 877-882. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/135273 [14] R. A. De Santis, “Why Exporting Countries Agree t Voluntary Export Restraints: The o Oligopolistic Power of the Foreign Supplier,” Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 50, No. 3, 2003, pp. 247-263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9485.5003009 [15] A. Martina and W. Vergoted, “On the Role of in Trade Agreements,” Journal of Internationa Retaliation l Econom- ics, Vol. 76, No. 1, 2008, pp. 61-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2008.03.009 [16] J. Peck, “A Note on Competing Mech velation Principle,” Ohio State University, Mime anisms and the Re- o, 1 281-1312. 995. [17] D. Martimort and L. Stole, “Communication Spaces, Equi- libria Sets and the Revelation Principle under Common Agency,” University of Chicago Graduate School of Bu- siness, Discussion Paper STE019, 1997. [18] P. McAfee, “Mechanism Design by Competing Sellers,” Econometrica, Vol. 61, No. 6, 1993, pp. 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2951643 [19] M. Peters, “On the Equivalence of Walrasian and N Walrasian Equilibria in Contract Ma on- rkets,” Review of Eco- nomic Studies, Vol. 64, No. 2, 1997, pp. 241-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2971711 [20] M. Peters and S. Severinov, “Competition among Sellers Who Offer Auctions Instead of Prices,” Journal of Eco- nomic Theory, Vol. 75, No. 1, 1997, pp. 141-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jeth.1997.2278 [21] S. L. Brainard and D. Martimort, “Strategic Trade Policy with Incomplete Informed Policymakers,” Journal of In- ternational Economics, Vol. 42, No. 1-2, 1997, pp. 33-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(96)01446-8 [22] L. G. Epstein and M. Peters, “A Revelation Principle for 542 Competing Mechanisms,” Journal of Economic Theory, Vol. 88, No. 1, 1999, pp. 119-160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jeth.1999.2 and Disclosure 2 [23] A. Creane and K. Miyagiwa, “Information in Strategic Trade Policy,” Journal of International Eco- nomics, Vol. 75, No. 1, 2008, pp. 229-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2007.11.00 s in Gen-[24] R. Myerson, “Optimal Coordination Mechanism eralized Principal-Agent Problems,” Journal of Mathe- matical Economics, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1982, pp. 67-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-4068(82)90006-4 [25] B. P. Rosendorff, “Voluntary Export Restraints, Antidum- ort Re- 1/1467-9396.00092 ping Procedure, and Domestic Politics,” American Eco- nomic Review, Vol. 86, No. 3, 1996, pp. 544-561. [26] J. Ishikawa, “Who Benefits from Voluntary Exp straints?” Review of International Economics, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1998, pp. 129-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.111 ntary Export [27] S. Berry, J. Levinsohn and A. Pakes, “Volu Restraints on Automobiles: Evaluating a Trade Policy,” American Economic Review, Vol. 89, No. 3, 1999, pp. 400-430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.3.400 [28] R. C. Feenstra and T. R., Lewis, “Negotiated Trade Re- g/10.2307/2937965 strictions with Private Political Pressure,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 106, No. 4, 1991, pp. 1287-1307. http://dx.doi.or Quarterly Journal of [29] M. Spence, “Job Market Signaling,” Economics, Vol. 87, No. 3, 1973, pp. 355-374. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1882010 [30] J. A. Brander and P. Krugman, “A Reciprocal Dumping Model of International Trade,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 15, No. 3-4, 1983, pp. 313-321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(83)80008-7

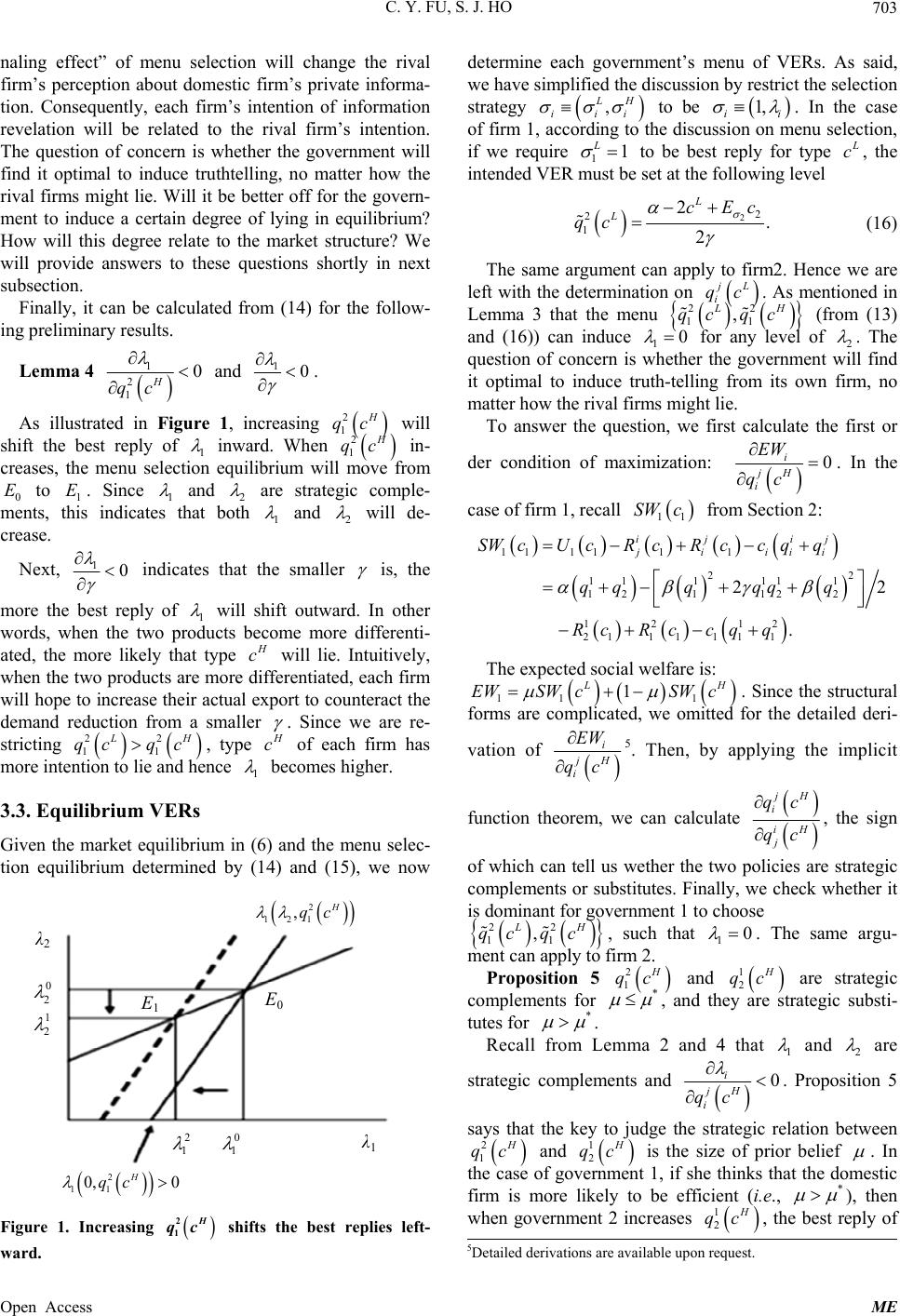

|