Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

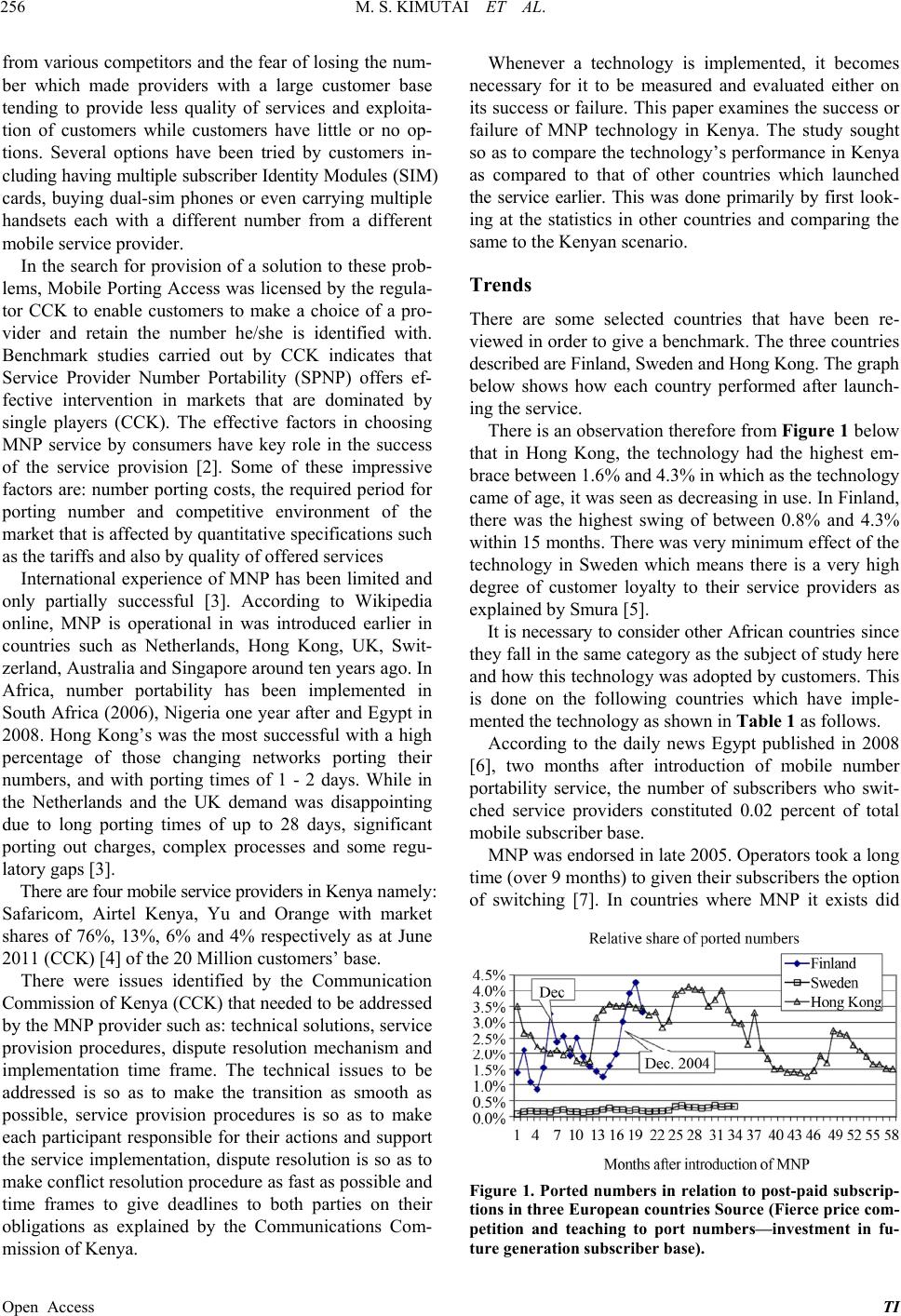

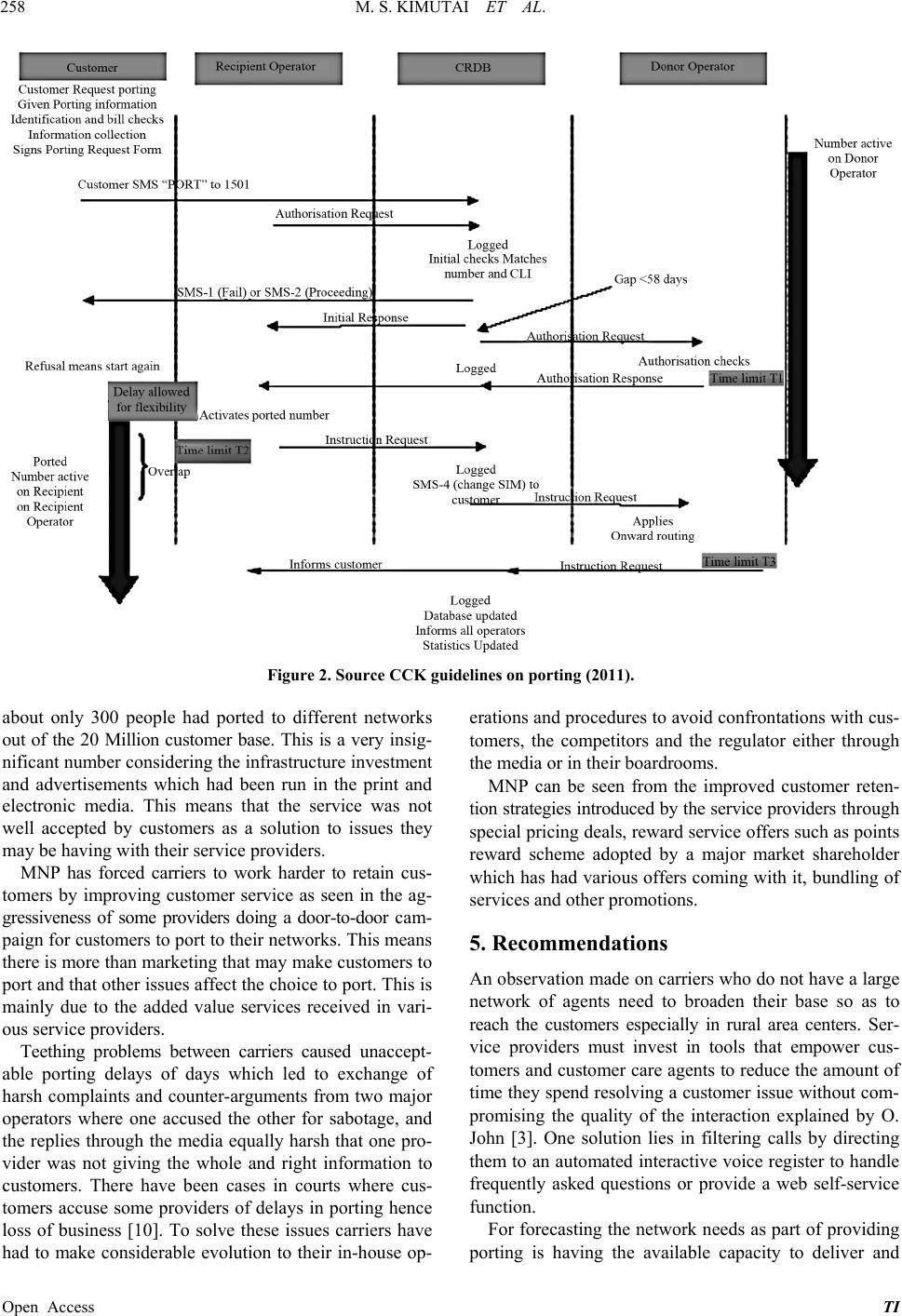

Technology and Investment, 2013, 4, 255-260 Published Online November 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ti) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ti.2013.44030 Open Access TI Mobile Number Portability: A Case Study of Kenya Metto S. Kimutai1, Kimeli V. Kimutai1, Awuor F. Mzee2 1Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Eldoret, Eldoret, Kenya 2Department of Computing Sciences, Kisii University, Kisii, Kenya Email: skmetto@yahoo.com, vkkimeli99@yahoo.com, fredrickawuor@gmail.com Received September 25, 2013; revised October 25, 2013; accepted November 2, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Metto S. Kimutai et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT In the telecommunications industry, mobile numbers are increasingly being seen as an asset of the regulato r. The free- dom of the customer using it is left to him/her to decide which service provider to use while retaining the same number. Mobile number portability (MNP) has been introduced to provide a platform for this freedom to the customer. The Telecommunications market Regulator in Kenya, the Communication Commission of Kenya (CCK), began the course of mobile number portability in 2010 through newspaper advertisement. The regulator had an aim that in the end, the right customer experience will be provided by the service providers, and help service providers to build profitable and lasting relationships b etween the service providers and th eir customer, and to differentiate themselves in the market. In this paper, we seek to evaluate the performance of MNP in Kenya since its launch. This paper seeks to find out how the service has performed after the first three months of operation. We survey and analyze MNP framework in Kenya and compare that to MNP in Japan, Finland, Sweden an d Hong Kong to establish the futur e of MNP in Kenya. It first looks at the MNP framework as used in Kenya and the procedure for reversal in case the customer is dissatisfied with a ser- vice provider who moves to and makes a reference to how the service has performed in other markets such as Finland, Sweden, and Hong Kong in order to enable comparative observations. Since there has been very little literature pub- lished for countries in Africa, it will only make comments on countries like Egypt, South Africa and Nigeria. Fu rther, it gives recommendations to the participating parties. Keywords: Communication Commission of Kenya; Customer; Mobile Number Portability; Service Provider 1. Introduction Mobile number portability (MNP) is the ability of a cus- tomer to change their mobile network operator and/or service provider while retaining the same mobile phone number for the provision of the same service as expl aine d by Durukan et al. [1]. It is aimed at deregulating the tele- communications sector by reducing the former fixed as- sociation between the service providers and the mobile subscriber while promoting competition in the market- place for mobile services. Mobile numbers are continu- ally being seen as a property of the regulators and so the freedom is left to the subscriber on which service pro- vider to use while retaining the same number. Telecommunications market regulator, the Communi- cation Commission of Kenya CCK initiated the process of mobile Number portability in 2010 throu gh newspaper advertisements asking the public to submit their views on the need for number portability service. CCK assigned a third party—Mobile Porting Access Limited, the duty of rolling out the MNP in Kenya in April 2010. This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the experiences in various countries; Section 3 presents the technical implementation of MNP, while Section 4 explains the findings and Section 5 deals with recom- mendations for adoption of newer technology in future. Conclusion and future work is presented in Section 6. 2. Literature Review Some of the issues mentioned to have caused the need for introduction of MNP center on network quality and calling rates. Specific issues mentioned include: Dropped calls, international calling rates, Static and unclear calls, over charging on calls claims, SMS adverts from specific mobile service providers (which often are broadcasted at night causing unnecessary attention), delays in delivery of services such as sms, failure to deliver services at all, low quality of network value added services such as launching of 3 G services, higher calling rates, offers  M. S. KIMUTAI ET AL. 256 from various competitors an d the fear of losing the nu m- ber which made providers with a large customer base tending to provide less quality of services and exploita- tion of customers while customers have little or no op- tions. Several options have been tried by customers in- cluding having multiple subscriber Identity Modules (SI M) cards, buying dual-sim phones or even carrying multiple handsets each with a different number from a different mobile service provider. In the search for provision of a solution to these prob- lems, Mobile Porting Access was licensed by the regula- tor CCK to enable customers to make a choice of a pro- vider and retain the number he/she is identified with. Benchmark studies carried out by CCK indicates that Service Provider Number Portability (SPNP) offers ef- fective intervention in markets that are dominated by single players (CCK). The effective factors in choosing MNP service by consumers have key role in the success of the service provision [2]. Some of these impressive factors are: number porting costs, the required period for porting number and competitive environment of the market that is affected by quantitative specifications su ch as the tariffs and also by quality of offered services International experience of MNP has been limited and only partially successful [3]. According to Wikipedia online, MNP is operational in was introduced earlier in countries such as Netherlands, Hong Kong, UK, Swit- zerland, Australia and Singapore around ten years ago. In Africa, number portability has been implemented in South Africa (2006), Nigeria one year after and Egypt in 2008. Hong Kong’s was the most successful with a high percentage of those changing networks porting their numbers, and with porting times of 1 - 2 days. While in the Netherlands and the UK demand was disappointing due to long porting times of up to 28 days, significant porting out charges, complex processes and some regu- latory gaps [3]. There are four mobile service providers in Kenya namely: Safaricom, Airtel Kenya, Yu and Orange with market shares of 76%, 13%, 6% and 4% respectively as at June 2011 (CCK) [4] of the 20 Million customers’ base. There were issues identified by the Communication Commission of Kenya (CCK) that needed to be addre sse d by the MNP provider such as: technical solutions, service provision procedures, dispute resolution mechanism and implementation time frame. The technical issues to be addressed is so as to make the transition as smooth as possible, service provision procedures is so as to make each participant responsible for their actions and support the service implementation, dispute resolution is so as to make conflict resolution procedure as fast as possible and time frames to give deadlines to both parties on their obligations as explained by the Communications Com- mission of Kenya. Whenever a technology is implemented, it becomes necessary for it to be measured and evaluated either on its success or failure. This paper examines the success or failure of MNP technology in Kenya. The study sought so as to compare the technology’s performance in Kenya as compared to that of other countries which launched the service earlier. This was done primarily by first look- ing at the statistics in other countries and comparing the same to the Kenyan scenario. Trends There are some selected countries that have been re- viewed in order to give a benchmark. The three countries described are Finland, Sweden and Hong Kong. The graph below shows how each country performed after launch- ing the service. There is an observation therefore from Figure 1 below that in Hong Kong, the technology had the highest em- brace between 1.6% and 4. 3 % in which as the technology came of age, it was seen as decreasing in use. In Finland, there was the highest swing of between 0.8% and 4.3% within 15 months. There was very minimum effect of the technology in Sweden which means there is a very high degree of customer loyalty to their service providers as explained by Smura [5]. It is necessary to consider other African countries s ince they fall in the same category as the subject of study here and how this technology was adopted by customers. This is done on the following countries which have imple- mented the technology as shown in Table 1 as follows. According to the daily news Egypt published in 2008 [6], two months after introduction of mobile number portability service, the number of subscribers who swit- ched service providers constituted 0.02 percent of total mobile subscriber base. MNP was endorsed in late 2005. Oper ators too k a long time (over 9 months) to given their subscribers the option of switching [7]. In countries where MNP it exists did Figure 1. Ported numbers in relation to post-paid subscrip- tions in three European countries Source (Fierce price com- petition and teaching to port numbers—investment in fu- ture generation subscriber base). Open Access TI  M. S. KIMUTAI ET AL. 257 Table 1. MNP implementation in some countries. Year Country 1997 Singapore 1999 Hong Kong, UK, The Netherlands 2000 Switzerland, Spain 2001 Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Portugal, Austr alia, Cyprus 2002 Italy, Belgium, Germany 2003 Finland, France, Iceland, Greece, Irelan d , Luxembourg 2004 Slovakia, South Korea, Austria, USA, Hungary 2005 Taiwan 2006 Czech Republic, Croatia, Saudi Arabia, Oman, South Africa 2007 Canada, Pakistan, Israel, Nigeria 2008 Brazil, Malaysia, Mexico, Bulgaria, Egypt 2009 Ecuador 2010 Peru, Thailand, Jordan, Kuwait, Albania 2011 India Kenya Source: Wikipedia online. not imply any radical increase in switching activities. But it provided an alternative that ensures that operators treat their customers better [8]. It had to be right so that it does not experience a down-fall. MNP implementation was a welcome idea for the cus- tomers but did not gather the required force; it was not widely accepted as a long-term solution for high call and interconnection rates but provide an avenue to control. MNP created an exciting competition among the mobile phone service providers with each determined to retain customers. The parties involved in rolling out MNP in Kenya in- clude: The mobile service providers: Safaricom, Airtel Kenya, Yu and Orange and their agents who have been contracted to carry out customer service on their behalf. The regulator: In Kenya the regulating body is the Com- munications Commission of Kenya (CCK). This is the body responsible for enhancing fair play and resolving conflicts. The MNP service provider: Mobile Porting Ac- cess Limited and the customers, who consume this prod- uct. Before one considers porting, one need to register his/ her number the government of Kenya gave a directive that all mobile numbers be registered by some identifica- tion documents that ar e required to authorize porting ju st like any other count r y . 3. Technological Implementation of MNP The basis of MNP technology implementation entails an extensive amount of effort and revision in the tel eco mmu - nications infrastructure. The implementation includes a number portability database; the number portability da- tabase (NPDB) keeps track of the ported numbers, their respective service providers and a selection of an appro- priate routing method for different types of calls and other value added services. The diagram (in Figure 2) [9] shows a summary as put by the Communications Com- mission of Kenya on MNP. The procedure for postpaid customers is however dif- ferent due to their business model, it has various detailed business rules including contracts signed with the pro- vider, the authorizing person to take care of corporate and individual accounts, offers that accompanied the package during migration to post pay, needs to be taken care of by the p olicy. The basic guideline to porting your number as pro- vided by the regulator is that when porting, you need to change your subscriber Identity Module (SIM) card. Much as the process seems to be like acquiring a new connec- tion, you retain your number. According to the CCK (2011) the general procedur es in number portability are: 1) The Subscriber opens an Account with the new (Recipient) Operator and pays the Per-Port Charge (Ksh. 200 Approx. $2.3). This is for them to be known by the recipient. 2) The subscriber installs a new SIM that has the number that they are already using with the old (Donor) Operator. To enable p ort i ng t o be po ssi bl e. 3) The subscriber requests the new operator to close their account with the old (donor) operator; to enable them start activate a new account at the recipient. 4) A request is made to all operators to change their routing arrangements so that calls can be routed directly to the new operator; this will enable the subscriber to continue with the service as usual. 5) The total tu rnaround time in th e porting process is a maximum two (2) working days including all stages; this is the service level agreed time. 6) Any porting process beyond two porting days shall be recorded by the CRDB and shall also form part of the key performance indicators reporting. Which will be used as a measure of performance of the individuals working there as part of annual appraisal. If a customer is dissatisfied by the service, there is an option given called cooling off. It is a 14-day time after porting in which you are per- mitted to go b ack to you r dono r o perator. You will no t be charged early termination fees if you exercise this option. 4. Findings The Communication Commission of Kenya (CCK) had anticipated that the service will have a high demand but the reception has been rather low such that after a week Open Access TI  M. S. KIMUTAI ET AL. Open Access TI 258 Figure 2. Source CCK guidelines on porting (2011). about only 300 people had ported to different networks out of the 20 Million customer base. This is a very insig- nificant number considering the infrastructure investment and advertisements which had been run in the print and electronic media. This means that the service was not well accepted by customers as a solution to issues they may be having with their service providers. erations and procedures to avoid confrontations with cus- tomers, the competitors and the regulator either through the media or in their boardrooms. MNP can be seen from the improved customer reten- tion strategies introduced by the service providers thr ough special pricing deals, reward service offers such as points reward scheme adopted by a major market shareholder which has had various offers coming with it, bundling of services and other promotions. MNP has forced carriers to work harder to retain cus- tomers by improving customer service as seen in the ag- gressiveness of some providers doing a door-to-door cam- paign for customers to por t to their networks. This means there is more than marketing that may make customers to port and that other issues affect the choice to port. This is mainly due to the added value services received in vari- ous service providers. 5. Recommendations An observation made on carriers who do not have a large network of agents need to broaden their base so as to reach the customers especially in rural area centers. Ser- vice providers must invest in tools that empower cus- tomers and customer care agents to reduce the amount of time they spend resolving a custo mer issue without com- promising the quality of the interaction explained by O. John [3]. One solution lies in filtering calls by directing them to an automated interactive vo ice register to handle frequently asked questions or provide a web self-service function. Teething problems between carriers caused unaccept- able porting delays of days which led to exchange of harsh complaints and counter-arguments from two major operators where one accused the other for sabotage, and the replies through the media equally harsh that one pro- vider was not giving the whole and right information to customers. There have been cases in courts where cus- tomers accuse some providers of delays in porting hence loss of business [10]. To solve these issues carriers have had to make considerable evolution to their in-house op- For forecasting the network needs as part of providing porting is having the available capacity to deliver and  M. S. KIMUTAI ET AL. 259 receive the traffic that flows between the interconnecting networks. To do so, a planning process must be followed between the interconnecting operators so that investment for additional capacity can be agreed, budgeted, and in- stalled in time to meet the forecasted demand [3]. Each carrier needs to identify their particular problems and remedy each through software patches, improved systems, well trained shop-front staff and enhanced cus- tomer education with other carriers and customers as explained [2]. According to a press release by one of the service provider (2011) [11], there was concern that cus- tomers are not given the right information. Customer care agents need to deliver superior customer service experi- ences as they help customers from answering their ques- tions about MNP to providing number por ting and re late d technical support and knowledge management [12]. Ser- vice providers must invest in training their ag ents in rural areas to carry out the porting requests on their behalf. Procedures to resolve differences over forecasts must be defined as well as what constitutes a bona fide request for additional interconnection capacity [13]. At a mini- mum, a mutual obligation to notify the other party of network changes and upgrades well in advance is needed to avoid disadvantaging one competitor over another. With average revenue per user declining, quality of servic e and customer exp erience play a decisive role in a subscriber’s choice of an operator. Mobile carriers need to adopt a multi-pronged strategy that focuses on the overall user experience so as to avoid losing customers to competitors. The greatest beneficiaries receiving customers should develop the capability to handle a potential surge of in- bound phone calls, respond substantively and accurately to inquiries, making offers in a way that persuades high- value customers to continue to stay and engaging suc- cessfully with prospective subscribers. The regulator should negotiate the movement of the money transfer service among service providers to be just like any other value added service such as SMS now that it is an SMS-based service. There have been cases of migration delay as reported by the media, though a clear format of dispute resolution has been put in place by the regulator, there have been cases in the courts and it takes long to be resolved if left to the courts. The regulator should take up and resolve the cases instead. The regulator should facilitate the in- troduction of industry-wide regulatory changes to reflect changing technologies and sector conditions to enable fast resolutions of conflicts. The regulator also should consider supporting more research on how best to implement MNP and other new Information Communications Technologies in a very dy- namic environment of the mobile service sector in terms of technical solutions, policy and implementation. The MNP provider should try to reach a near-real-time porting solution by establishing a complex solution be- tween carriers to manage the messaging between the los- ing mobile carrier, the gaining mobile carrier, carriage service pro viders and oth er parties that need to route calls to the ported customer [14]. The provider should try to provide an integrated money transfer framework such that irrespective of the customer’s network, he/she should be able to send or receive money provided it is in the same currency. The provider should also consider investing in further research on how best to sell the MNP technology to cu s- tomers and reduce barriers to the access of this service and develop an online porting platform to allow for a wider access to the customers who may be limited by time and location. The provider may also consider assisting in developing a transp arent banking solution via the various mon ey tr a n s- fer services such as M-PESA (A mobile money transfer service) on the M-KESHO (a platform in equity bank) and I&M Visa Card platforms. To mitigate effects of casual decision, based on in- complete information and done by the roadside at the instigation of commission-hungry agents, the customers must first confirm that they are well informed on cus- tomer procedures involved in MNP before making a de- cision to port and know the reasons and the time frame the porting process could be blocked before the service is resumed to avoid inconvenience. One should also under- stand how value added service such as Short message services(SMS), Voice Mail and Money transfer services would be handled when a number is ported; and under- stand how limited the disruption would be during the actual changeover. 6. Conclusions MNP has brought a unique challenge for mobile opera- tors and intensified the competition for retaining sub- scribers. Much utilization of the serv ice was expected by the regulator, it did not meet its expectation hence there has been a miss of the technology in the market. The statistics as for the first three months are approximately 143,000 requests made out of the 20 Million customers, which makes 0.715% which is insignificant. This implies a great maintenance of the status quo and this option acts as a regulation to other service providers who don’t act in an anti-competitive behavior. Considering the investments done where one service provider invested Ksh. 10 million (Approximately $116 280) as released by Safaricom [12] which means if each of the four operators invested approximately the same amount using the 2010 (which has been dropping) aver- age rate of spending per user (ARPU) of Ksh 437 ($5) annually, it would take over 8 months to recover the in- Open Access TI  M. S. KIMUTAI ET AL. Open Access TI 260 vestment from the same customers excluding any opera- tional costs. This low response on the service also means that either, there is a high degr ee of customer lo yalty among th e sub- scriber base to their service providers [15] or there is an uninformed population especially among the people liv- ing in rural areas on the number portability. In the end, MNP has been good to the customer in that it has made service providers more responsive in pro- tecting their customer territories and locking out com- petitors. The service providers have been forced to seek the right customer experience that will help them build profitable, lasting relationships and differentiate them- selves in an increasingly competitive market. REFERENCES [1] T. Durukan, I. B. Taylan and T. Dogan, “Mobile Number Portability in Turkey: An Empirical Analysis of Consu- mer Switching Behavior,” European Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 20, No. 4, 2011. [2] H. G. Shakouri, “Impact on Dynamic Behavior of a Two- Competitor Mobile Market: Stability versus Oscillations,” 2010. [3] O. B. John, “Telcorum Case Study 2,” 2005. [4] C. C. O. Kenya, “Statistics,” Nairobi, Kenya, 2010. [5] T. Smura, “Mobile Number Portability: Case Finland,” 2004. [6] E. M. Sherine, “Vodafone Numbers Drop as Mobile Subscribers Make the Switch,” Daily News Egypt, 2008. [7] K. Naidoo, “Middle East & Africa Market Perspective,” Vol. 6, 2006. [8] A. Oladejo, “Mobile Number Portability in Nigeria: A Note For the NCC,” 2011. [9] C. C. O. Kenya, “Procedures and Guidelines for the Pro- vision of Mobile Number Portability Services in Kenya,” 2011. [10] Airtel, “10 reasons to HAMA to Airtel,” 2011. http://www.nikuhama.com/what-is-mobile-number-porta bility.aspx [11] C. C. O. Kenya, “Public Consultation Document on Intro- duction of Number Portability in Kenya,” Nairobi, 2010. [12] Safaricom, “Press Release,” Safaricom Limited, Nairobi, 2011. [13] C. K. N. Bashar, J. Hamza, N. K. Noordin, M. F. A. Rasid and A. Ismail, “The Seamless Vertical Handover between (Universal Mobile Telecommunications System) UMTS and (Wireless Local Area Network) WLAN by Using Hybrid Scheme of Bi-mSCTP in Mobile IP,” 2010. [14] S. A. Odunaike, “The Impact of Mobile Number Port- ability on TUT Students On-Line Connectivity,” Pre- sented at the Information Systems Educators Conference, Nashville, 2010. [15] A. Caruana, “The Impact of Switching Costs on Cust- omer Loyalty: A Study among Corporate Customers of Mobile Telephony,” Journal of Targeting, Measurement, and Analysis for Marketing, Vol. 12, 2004. |