Open Journal of Political Science 2013. Vol.3, No.4, 175-183 Published Online October 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojps) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2013.34024 Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 175 Selling Politics? How the Traits of Salespeople Manifest Themselves in Irish Politicians Dónal Ó Mearáin, Roger Sherlock, John Hogan College of Business, Dublin Institute of Technology, Dublin, Ireland Email: domearain@hotmail.com, roger.sherlock@dit. ie , john.hogan@dit.ie Received July 23rd, 20 13 ; revised August 30th, 2013; accepted September 13th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Dónal Ó Mearáin et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This article seeks to uncover if some of the traits most associated with salespeople manifested themselves in the activities of candidates in the constituency of Dún Laoghaire during the 2007 Irish general election. Such a finding would suggest that just as political parties have looked to the marketing profession for their lead in developing political marketing, politicians are looking to, and adopting the traits of those in the sales profession. This would point to the traits that the modern politician must possess in order to get and remain elected. It would also raise significant questions in terms of how candidates present them- selves to the electorate, as well as how they go about campaigning and formulating policy. Keywords: Traits; Sales; Marketing; Election; Trust; Empathy; Ego Introduction Traditionally, in political science, election results received most of the attention (Campbell, 2000; Holbrook, 1996). The prevailing view was that the relative stability of party loyalties and values, left little room for analysis of the campaigns to persuade voters, while undecided voters—those most likely to be persuaded—paid little attention to campaigns (Campbell, 2000). The marketing efforts of parties were seen to negate each other. As a result, political campaigning and accompany- ing marketing were regarded as having little effect on voter choices and election results (Steger, Kelly, & Wrighton, 2006). However, over the last quarter century, political actors—in- terest groups, candidates and political parties—have been in- creasingly thinking in marketing terms (Henneberg, 2008). This is clear from their use of marketing management theories, with the result that today marketing is an integral part of politics (Moloney, 2004). “Political marketing is a global phenomenon with parties from all corners of the world developing manifes- tos based around the results of qualitative and quantitative marketing research” (Lilleker & Lees-Marshment, 2005: 1). A central issue in the broader marketing discipline is the ten- sion, gaps and fraught interactions between salespeople and marketing, rather than the assumed fit between these domains (Malshe, 2010; Malshe & Sohi, 2009; Oliva, 2006; Matthyssens & Johnston, 2006). The emergence of these tensions in the political domain reinforces the need to explore this issue. As consumers have become educated to marketing tech- niques, they have become more discerning in the political arena. In response, parties have sought to use cutting edge commercial techniques to gain their attention/support. According to Lilleker & Lees-Marshment (2005), many modern parties aim at per- suading voters through marketing, based on an understanding of how markets can be manipulated. This approach seeks to make the public desire what the party is offering—utilizing advertising and message construction research (Fill, 2002). While Irish political parties have traditionally competed less on policy and ideological differences, and more on what they can do for voters (Katz, 1984), the question we ask here is—are Irish politicians sales orientated? Specifically, in what way do the traits of a salesperson manifest themselves in the under- standing of the modern Irish candidate? This paper will, through an exploratory process, develop insights into the mani- festation of selling traits and practices among Irish politicians in one of the largest and most affluent constituencies in the county. The Electoral and Constituency Context Intraparty electoral competition is integral to the proportional representation single transferrable vote (PRSTV) electoral sys- tem in Ireland (Gallagher, 2005a). This PR system creates a situation where the primary decisions to be made by voters concern their choices of representatives for their constituency (Lynch & Hogan, 2012). The result is the concept of a connec- tion between voters and candidates that is stronger than the concept of party representation found in the PR list systems (Sinnott, 2009: 112). Over the past few decades there has been an ongoing debate concerning the extent to which PRSTV is to blame for the preoccupation of Teachtaí Dála (TDs) with con- stituency service (FitzGerlad, 2002). Katz (1984) points out that party competition in Ireland tends to be based on services pro- vided as opposed to policy differences. With the major parties running two to three candidates in each multi-seat constituency, these candidates are primarily competing with each other for the first preference votes of those constituents committed to their party, much more so than with candidates from rival parties (Gallagher, 2005a). This need to  D. Ó MEARÁIN ET AL. win as many first preference votes as possible can create a lack of harmony between running mates, where the individual can- didate is central to voter choice rather than the party (Benoit & Marsh, 2003). That said, all candidates would like to attract floating voters and the second and third preferences of con- stituents who would be supporters of rival parties. This need results in candidates wanting to be perceived as constituency workers. Consequently, TDs primary focus is perceived to be on constituency issues, with national affairs coming second in their consideration (Gallagher, 2005b). In this context, cam- paigning in Irish elections is dominated by face to face interac- tion between candidates and constituents. Over 60 per cent of people received some personal contact from either candidates, or their volunteers, in the 2007 general election (Sudulich & Wall, 2009: 459). Therefore, it is appropriate and suitable to explore the politician as a salesperson. The candidates whose traits will be examined all ran in the 2007 general election in the constituency of Dún Laoghaire. Of the 11 candidates who competed for the five seats the paper focuses upon: Mary Hanafin TD, (Fianna Fáil (FF))—Minister for Educa- tion and Science. Barry Andrews TD, (FF)—Minister of State for Children. Séan Barrett, (Fine Gael (FG))—a former minister, did not stand in the 2002 election. Eamon Gilmore TD, (Labour Party (LP))—opposition party leader. Eugene Regan (FG)—first time g e n er a l el e c ti o n candidate . The quota in Dún Laoghaire was 9,786 votes. The incumbent candidates were Hanafin, Andrews, Gilmore, O’Malley and Cuffe. Hanafin was elected on the first count. Of her surplus of 2,098 votes, 1,390 went to Andrews, electing him on the sec- ond count. Gilmore was elected on the 7th count, with Barrett following on the 9th (Table 1). The last seat went to Cuffe on the 10th country. Of the incumbents only O’Malley lost her seat. Campaign spending has been linked to election results—spe- cifically with a greater share of first preference votes (Benoit & Marsh, 2004). However, Table 1 shows that the candidate who spent the least, Hanafin, won the highest percentage of first preference votes. Quinn and O’Malley, the first and third high- est spending candidates finished 9th and 10th respectively, high- lighting that expenditure and incumbency, do not always guar- antee success. That said, Cuffe, Andrews and Barrett had the second, fourth and fifth highest expenditures. Research Motivation: The Selling Traits of Politicians The aim of this paper is to uncover if the traits of a salesper- son manifested themselves in the campaigning activities and understandings of the selected candidates. Greenberg and Greenberg (1976) argue that the traits sales- people possess, and how these are combined, differentiate them from other professions. The importance of these traits has come to the fore as we have moved away from assuming that a sales- person’s function is to sell—and that success depends on them alone—to seeing the selling/buying process as actively engaged in by salespeople and customers (Grikscheit, Cash, & Young, 1993). The most important traits associated with salespeople are integrity and trustworthiness (Peterson & Lucas, 2001), a strong ego (Rasmussen, 1999), empathy (Hogan, 1969), posi- tioning and communicating persuasively (Karr, 2009) and per- sistence due to the perpetually challenging nature of sales (Duran, 2004). ‘Trust is an integral component of the sales relationship’ (Haan & Berkey, 2006: 122). People will purchase from those they trust. According to Swan, Trawick & Silva (1985) trust is at the heart of enduring relationships with customers. However, trustworthiness is paradoxical in business, as a salesperson’s instinct is to be opportunistic (Oakes, 1990). What allows trust to be built (consistency) is broken by this opportunistic instinct. Ego, in the form of a strong desire to succeed, is seen as crucial for the success and survival of a salesperson (Mayer & Green- berg, 2006). “To top salespeople, the sale—the conquest—pro- vides a powerful means of enhancing the ego” (Allen, 2010: 120). Many psychologists feel that empathy, the ability to accu- rately perceive the feelings of clients, is crucial in selling and developing trust (Lee & Dubinsky, 2003). Empathy goes be- yond being sympathetic, as one can understand what another feels without agreeing with that feeling (Allen, 2010). Findings suggest successful salespeople show moderate empathy. The Table 1. Candidate expenditure and first preference votes in Dún Laoghaire (2007). Candidate Total expenses €000 Expenditure Ranking % of total constituency expenditure % of first preference votes won Count elected Andrews, Barry FF 25.72 4th 11.2 14.6 2nd Bailey, John FG 20.50 7th 8.9 7.4 Barrett, Séan FG 22.41 5th 9.2 9.1 9th Boyd Barrett, Richard PBP 16.76 9th 7.3 8.9 Cuffe, Ciarán GP 29.47 2nd 12.9 7.7 10th Gilmore, Eamon LAB 20.06 8th 8.7 12.4 7th Hanafin, Mary FF 14.47 10th 6.3 20.2 1st O’Malley, Fiona PD 31.08 1st 13.5 6.7 Quinn, Oisín LAB 28.97 3rd 12.5 3.8 Regan, Eugene FG 20.66 6th 9 7.1 Eoin O Broin SF 18.40 11th 0.8 2.1 Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 176  D. Ó MEARÁIN ET AL. salesperson with too much empathy will be considered “nice”, but will often miss a sale (Mayer & Greenberg, 2006). The US government’s own Department of Labor has pointed out that the ability to communicate persuasively is vital for anyone planning a career in marketing, sales or public relations (Labor Department, 2010). Persistence is something all sales people must to possess. According to Zeller (2011: 202) “persistence is a resolved mindset to continue on even in the face of adversity or preliminary negative results”. “Political parties no longer pursue grand ideologies, fervently arguing for what they believe in and trying to persuade the masses to follow them” (Lees-Marshment, 2001: 1). This is because, in many countries, they have seen the social founda- tions of their support evaporating—as the homogenous social classes that gave rise to the m become difficult to define (Chad- wick, 2006). In such heterogeneous political environments voters are likely to be more issue orientated (Kotler & Kotler, 1999). As a result parties have adopted a market orientated approach—seeking to satisfy the voters (customers) demands. This has engendered fundamental shifts in all aspects of their behaviour, as they adopt a marketing philosophy (Lilleker, Jackson & Scullion, 2006). However, in Ireland, ideological differences between the parties have never been at the centre of electoral competition—services have (Katz, 1984). To be market orientated involves a set of behaviours based on the ability to act upon market intelligence with a focus upon customers, competitors and how the various parts of the busi- ness act in concert (Ormrod & Henneberg, 2006). In the market orientated political party “its members are sensitive to the atti- tudes, needs and wants of both external and internal stake- holders, and use this information within limits imposed by all stakeholder groups in order to develop policies and pro- grammes that enable the party to reach its aims” (Ormrod, 2005: 51). Ormrod’s (2005) conceptual model of Political Market Orientation (PMO) focuses on the attitudes of party members to voters, competitors, and other external stakeholder groups. In this context, and in light of the above traits associ- ated with salespeople, viewing political campaigning as a form of sales involving interpersonal communication recognizes the politician and voter as active participants—like seller and prospect. The need satisfaction approach to selling fits well with politics, as it is the voter’s (prospects’) needs that are the priority of the politician (seller). This is a customer orientated approach to selling—as their point of view and unique needs are being addressed. In this approach, it is the politician’s (salesperson’s) task to identify the need that is to be met and then to help the voter (buyer) meet that need (Ingram et al., 2007). Research Methodology As the paper is seeking to understand, but not to quantify, the nature of politicians as salespeople, a qualitative, interpretive research approach is the most appropriate here. An interpreta- tive approach stresses the difference between the humanities and natural sciences in its quest for understanding rather than explanation or prediction (Holbrook & O’Shaughnessy, 1988). The most common method used to access such understanding is the in-depth interview. This technique aims to uncover a par- ticipant’s outlook on the world and in so doing give a deeper insight into a research problem. It has been described as a con- versation with a purpose (Kahn & Cannell, 1957). As such, the information is expressed in words—descriptions, accounts, opinions and feelings (Walliman, 2005). Purposive sampling was used in this research. The principle of purposive sampling is to “maximise discovery of the hetero- geneous patterns” and not to generalize to the broad population (Erlandson et al., 1993). The nature of the simultaneous genera- tion of the data and its analysis creates an emergent design and also impacts on the sampling process. The objective is to “bot- tom out” on the phenomenon; continuing to research the topic until each subsequent interview provides no new dimensions on the phenomenon. While there are no upper or lower limits to sample size for such a study, a sample of ten is typical, with 3 to ten respondents being utilized by McCracken (1998) and Mick & Buhl (1992). As McCracken (1998: 17) describes it, “qualitative research does not survey the terrain, it mines it. It is, in other words, much more intensive than extensive in its ob- jectives”. Of the 43 constituencies in the 2007 general election, Dún Laoghaire was one of 12 five seat constituencies and one of only three five seaters in Dublin, the remainder being three or four seat constituencies. This made Dún Laoghaire one of the larger constituencies in the county. In 2007, Dún Laoghaire was the most affluent and prosperous five seat constituency, with more than twice as many constituents, as the national average, possessing third level degrees and a high proportion of profes- sionals1. Following the election, the constituency was changed to a four seater upon the recommendations of the Independent Constituency Commission2. As there were five seats available in this constituency, each of the larger parties, Fianna Fáil (FF), Fine Gael (FG) and Labour ran two candidates, generating the usual intraparty competition, with the remaining five candidates coming from the minor parties and an independent. Thus, there were 11 candidates competing for the constituency’s five seats, encompassing a party leader, senior and junior ministers, senior opposition TDs as well as some very junior candidates. The five candidates selected for interview were representative of this vast experiential range. Consequently, the interviewees possessed similar and simultaneously different characteristics. This research is heavily contextualised, framed within na- tional politics, local politics, campaign expenditure and the importance of temporality and location. Herein, reality is con- structed socially and behaviour is determined by multiple and changing variables (Hudson & Ozanne, 1988). In this environ- ment the interpretivist approach is ideal, as it is intended to explore the behaviour of the politicians through their own un- derstandings of how they act (Mason, 2002). This allows for meanings, views, opinions and attitudes to be interpreted through construction of their responses (Creswell, 2003). As there is an absence in the literature on whether politicians model their practices on those of salespeople (Chisnall 2005), analyzing the in-depth interviews will permit us discover if the traits most associated in the literature with salespeople—integ- rity and trustworthiness, a strong ego, empathy, positioning and communicating persuasively and persistence—are to be found amongst the selected politicians. The interviewees’ awareness of marketing in politics will be addressed—as the role of mar- keting in sales led to the development of relationship selling and an awareness of the important traits salespeople possess. 1http://www.oireachtas.ie/documents/library/constituencies_profiles/Dun_La oghaire.pdf 2http://www.constituency-commission.ie/docs%5Ccon2007.pdf Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 177  D. Ó MEARÁIN ET AL. Examination of the Selling Traits of Dún Laoghaire Candidates The Importance of Integrity and Trustworthiness In as much as the traits of integrity and trustworthiness in salespeople are of crucial importance in the literature and yet seem paradoxical, logic suggests that trusting someone who is representing you, and your interests, as well as believing in their integrity, is imperative. Killinger (2007: 12) defines integ- rity as “a personal choice, an uncompromising and predictably consistent commitment to honour moral, ethical, spiritual, and artistic values and principles”. Integrity is an essential trait for a politician. Newton (2007: 343) defines trust as “the belief that others will not deliberately or knowingly do us harm, if they can avoid it, and will look after our interests, if this is possible”. Trust is indispensable from representative relationships in modern democracies (Bianco, 1994). How career minded poli- ticians pursue reelection is built upon assumptions of integrity and trustworthiness (Hetherington, 2005). However, being a politician is a role accompanied by a level of suspicion found in few professions (McGraw, Lodge, & Jones, 2002). They worry that distrust can be resolved by voters through electoral replacement (Keele, 2005). As Regan told us, it is “critical for politicians that they are seen to abide by the standards set for themselves in legislation”, as otherwise they will be tarnished and discredited. Almost paradoxically, all interviewees admitted that a can- didate had to be willing to be unpopular to be successful. They all knew of instances where constituents did not appreciate decisions they made, or policies they advocated. But, they were nonetheless convinced the public respected them for these hard decisions. Barrett felt that if a politician achieves a reputation for honesty respect follows. This relates to interviewees em- phasizing the importance of ethics in politics. To be perceived as acting according to a certain standard, or upholding certain commitments, is a basis of trustworthiness (Levi, 1998). As Gilmore says, “people have to trust, and are entitled to trust, their public representatives”. The kind of trust in the Irish con- text is referred to as thick trust—that found in small bonded communities made up of largely homogenous population (Wil- liams, 1988). Trust has been found to clearly correlate with electoral suc- cess (Hetherington, 1999). Studies show competence, integrity and honesty are attributes often ascribed to candidates by the citizens who vote for them (Mattes et al., 2010). Awareness of the importance of trust can allow politicians suppress more opportunistic tendencies (Bromiley & Cummings, 1995). In politics, “the absence of opportunistic behaviour is a crucial condition for the trustor to place trust in a trustee” (Six, 2005: 18). Alternatively, salespeople are opportunistic by nature and therefore tend to be inconsistent. Being perceived as consistent may allow a politician avoid the kind of opportunism that can diminish trust and damage a career. Consequently, in addition to the importance of ongoing ethical behavior there is a histori- cal element at work, in that a candidate’s past record is impor- tant to an electorate with long memories (Lloyd, 2006). The Importance of Empathy In relation to salespeople, Greenberg, Weinstein & Sweeney (2003) point out that the trait of empathy and the capacity to empathize relates to ones motivation to do so. For the good salesperson, while they might genuinely like meeting people and wanting to serve them through the product they are offering, they nevertheless see people as a means of making a sale. De- spite this cold and hard calculation of selling, empathy is inte- gral to a good sales technique (Greenberg, Weinstein, & Swee- ney, 2003). All interviewees enjoyed working with the public. They be- lieved empathy critical to being able to engage constituents. Empathy relates to sensitivity towards the needs of others, compassion and a willingness to cooperate (Caprara et al., 2003). They felt it vital to be able to understand constituents, their needs, and how they expressed themselves. Regan re- marked that it was necessary for a politician to like meeting people—as they encounter constituents under a variety of cir- cumstances—so they can develop a connection with constitu- ents, wherein they are perceived as the ideal constituency rep- resentative. Hanafin felt that a politician had to have “a genuine interest in people and in the work”. She went on to say “the day you stop enjoying it is the day you shouldn’t be a public repre- sentative”. For Funk (1997) empathy—that trait which can fa- cilitate relationship building—is crucial when dealing with constituents. The interviewees emphasized the need for empathy through listening. In sales, being able to listen is a large part of being empathetic and building trust (Ramsey & Sohi, 1997). They consider the skill of listening vital to making a connection with the electorate. Such listening permitted them get at what they interpreted as the deeper meaning of messages coming from the public. While empathy is not often considered as important to a politician’s success as integrity—it is crucial in the develop- ment of an overall evaluation of candidates and is important for a politician attempting to build relationships. Recognition of the importance of empathy by the candidates comes from the realization that emotional reactions play a powerful role in attracting people to candidates (Westen, 2007). The implication of this finding is that candidate preference amongst constituents can be impelled by the personality, as much as by the policies they advocate (Iyer et al., 2010). Ac- cording to the congruency model of political preference, voters select politicians whose traits match their own (Caprara & Zimbardo, 2004). This fits with the argument that similarity breeds liking (Byrne, 1997). Similarities between voters and politicians constitute the “humanizing glue”, which has a clear impact upon various emotional and cognitive appraisals of can- didates (Iyer et al., 2010: 295). The Importance of Ego Strength Ego strength is the degree to which an individual likes them- selves. “If an individual possessed a high level of ego-strength, then failures can motivate the person toward the next try” (Greenberg, Weinstein & Sweeney, 2003: 43). In sales, pos- sessing the trait of a strong ego is vitally important, as other- wise rejection will lead to a diminished sense of self and self confidence and ultimately the ability to bounce back from dis- appointments. Thus, while ego strength is a very important trait in sales, it is also crucial in politics, where rejection and failure are ever present realities. Barrett has particularly mixed feeling about elections. He describes them as popularity contests—but ones where everyone knows the result. He worries about how family and friends will perceive him if defeated. He sees elections as Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 178  D. Ó MEARÁIN ET AL. distinctive events, full of emotional highs and lows that are impossible to describe. An election can be regarded as a refer- endum on a candidate’s pervious performance (O’Shaugh- nessey, 2001). But, despite Barrett’s concerns, he must possess a high level of ego strength, as he has been a politician for over thirty years. Andrews admitted that being in the public eye had its pros and cons. He said “the worst thing would be if you did some- thing wrong and it affected somebody negatively, that’s where it would be hard to get over”. However, this is to ignore the fact that it has long been recognized that voters form opinions based upon candidate’s images and not on campaign issues (Sears, 1969). The interviewees’ admitted public life can be emotionally challenging, but that setbacks are part of the job—just as in sales (Mayer & Greenberg, 2006). Regan regarded his finishing 7th in such a competitive constituency as gratifying, but in re- sponse embarked upon a Senate campaign. Once elected to the Senate he felt he was able to put the Dáil defeat behind him. Gilmore remarked that after the defeat of the Rainbow Coali- tion government in 1997, in which he served as a minister of state, he concentrated on constituency work, and on whatever “spokespersoship” he was appointed to. Hanafin looked with equanimity upon what she once considered career setbacks— failure to get elected to the Dáil in 1989, losing her seat in Dub- lin City Council in 1991, being appointed chief whip in 2002. This enabled her rationalize these events. Ego, and particularly ego strength, is crucial to the success and survival of politi- cians. The Importance of Positioning and Communicating Persuasively Salespeople are purposeful when it comes to the first impres- sion, they are innately conscious of how they position them- selves (Karr, 2009). This positioning sets the framework for the subsequent interaction and relationship that develops between the seller and customer. They also seek to communicate per- suasively, delivering their message with eloquence and style (Karr, 2009). Both of these traits—positioning and persuasive communica- tion—are crucial in politics. The interviewees discussed how their parties’ conducted market research and spoke of the ne- cessity of de livering a clea r and consistent message. Regan said focus groups had been carried out by FG prior to the election and their findings fed into the party’s policies. He admitted that, as a candidate, he tried to ensure his policy messages were the same as the party’s. His language betrayed how much a party’s market research drives a campaign and is crucial in what can- didates do. In contrast, Barrett portrayed FG as a lecturing/ sermonizing entity, using its platform to deliver decrees and decide the course of action. Barrett said “we were trying to preach a message that we were heading into trouble and unfor- tunately people didn’t want to listen”. This suggests some poli- cies were not based on the electorate’s input—but the party’s vision. Lees-Marshment (2001) refers to this as a product ori- entated approach. As Gilmore is a party leader, he provided a national and con- stituency perspective on the 2007 election. He said that in the election Labour sought to present the option of an alternative government—a Labour/FG collation. Feedback on Labour’s policies was filtered through its social democratic lens, but was also tempered by the need to coordinate its campaign with FG. In addition to public opinion influencing policy formulation, political neces s ity played a part. In terms of positioning, Hanafin regarded it as a requirement of the job for politicians to set high standards in how they pre- sent themselves—the way they dress, comportment and per- form for the media. As Kotler & Kotler (1999) suggest, when talking about marketing in general, clothes, behavior and statements all shape the impression created. Hanafin regarded FF, and its policy vision for the economy, as being in control of the agenda throughout the campaign. To some extent, her lan- guage suggests, as Barrett’s did, that the party preaches a vi- sion. However, Hanafin’s running mate, Andrews, had a different perception of how public opinion influences policy. He re- cognized that while FF might have liked to talk about their successes in the Northern Ireland peace process, or in relations with the European Union (EU), the public set the agenda through their concerns over the economy. By “the public” he is referring to feedback from constituents, as well as information gleaned from national polling data collected by the party. An- drews’ likened policy making to sailing a yacht, “you can work the tiller all you like but it’s which direction the wind blows is crucial. The public determine which way the wind blows!” That his perceptions strongly influenced his positioning and the manner in which he communicated his policies ties in with recent work in social psychology which points to the “gut- level” intuitive processes that underlie a significant amount of political decision making (Greene & Haidt, 2002; Westen, 2007). The candidates’ approaches to devising and communi- cating policies fits with Lees-Marshment’s (2001) argument that the market oriented party and candidates conduct research, design policies around that research and adjusts their offerings to make them achievable, popular and suitable to the party’s ideals while still different to its competitors. More significantly, all respondents echoed the fraught sales-marketing interface (Malshe, 2010; Oliva, 2006; Malshe & Sohi, 2009; Matthyssens & Johnston, 2006) whereby central planning by the Headquar- ters (the political “marketing department”) could be at odds with the individual candidates approach (the “sales depart- ment”). As a result, the need for integration, communication and coordinated planning at the interface between sales and marketing is of e q u al i mportance in the sphere of politics as it is in the commercial sphere. The Importance of Persistence Due to the Perpetual Political Campaign “If you are in sales you are perpetually in a state of war” (Martin, 2006: 9). Once a sale is completed the game is not over, but begins anew. It is a process that never ends. Thus, persistence is an important trait for the salesperson to possess (Duran, 2004). The same is now true of politicians, as political campaigning, in most countries, is now seen as perpetual, where elections serve to mark the ending of one campaign and the beginning of another (Polsby et al., 2012). While some people may feel politicians are rarely seen out- side of election time, the interviewees presented an under- standing of the need to remain in contact with the electorate on a personal level to achieve a presence in their consciousness. Barrett and Andrews commented on the long campaigning cy- cle developing in Ireland, as opposed to the “three week elec- Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 179  D. Ó MEARÁIN ET AL. tion campaign” that Barrett experienced in the early 1980s. According to Andrews, the regularity of the five year general election cycle since 1992 has meant candidates are effectively involved in what Blumenthal’s (1982) refers to as the “perpet- ual campaign”, as they have a greater degree of certainty when the next election is to be held. Gilmore observed that the next election campaign begins the day a candidate is elected. While political marketing was once episodic, it is now a constant for political actors (Henneberg & O’Shaughnessy, 2007). Thus, politicians need to be perpetually active in their constituencies and by so doing are perpetually campaigning for their next election bid. This creates a situation where on the one hand constituents have more expectation of, and place greater demands upon, candidates; while candidates must have a longer term approach to campaigning and working with the electorate. Andrews said that he was always “out and about” seeking to “build relation- ships” with constituents. He recognized that the number of citi- zens encountered in a clinic was relatively small—a limitation in terms of overall campaign exposure. Gilmore observed that, in the context of the long campaign, the candidate has to adopt a long term view of building relationships with constituents and be persistent in that approach. The importance of relationships to political marketing was recognized by Gronroos (1998) when he conceptualized political marketing as existing within an overarching paradigm of relationship marketing. Barrett de- scribed this activity as “selling yourself”. This is consistent with Saxe and Weitz’s (1982) argument that relationship selling arises when the needs of customers are particularly complex and in response the salesperson becomes focused upon the cus- tomer. Andrews admitted there is little point in a candidate present- ing themselves to the public in the run up to an election if they have not been in the constituency dealing with citizens’ com- plaints over the preceding years. He observed “people aren’t stupid, for all the campaign smarts you may have and how clever you are at the door, people know they haven’t seen you in five years”. This fits with Dean & Croft’s (2001) argument that political campaigning should be focused on building life- time relationships with voters. Barrett said that he was never more than 24 hours away from a face to face meeting with any constituent. All interviewees recognized building relationships by solving problems was critical. Hannifin said working for constituents was a positive experience that connected her to the electorate. She also recognized the potential payoff such work generated in terms of kudos. Andrews considered such close interaction vital to enable a candidate preempt constituents’ needs. This desire, to be ahead of constituents, is something all interviewee’s wanted to achieve—they feared missing out upon important local issues. The result of this continuous unofficial campaigning is that when the election campaign proper begins the interviewees seemed to treat it as a short period during which they simply intensify what they are already doing. Election canvassing sim- ply involves more advertising, leafleting, and knocking on doors. The criteria associated with relationship selling are evi- dent in the candidates’ perceptions of how persistently seeking to build relationships is critical in politics. Conclusion In the literature, the most important traits associated with salespeople are integrity and trustworthiness, a strong ego, em- pathy, positioning and communicating persuasively and persis- tence. The ability to build trust with customers is vital. A strong ego is crucial for a salesperson, as otherwise they might give up. Empathy is essential in developing trust. Positioning and com- municating persuasively allows salespeople to create a good first impression and establish interaction. Persistence is neces- sary as the business of selling never ends. Yet, these traits are not exclusive to salespeople—they are to be found in the inter- views conducted with the five candidates in the Dún Laoghaire constituency in the 2007 Irish general election. Trust and integrity are crucial in the political environment. The public needs to know that its representatives will honor their commitments and stay loyal to their values, while looking after the public’s interests and not harming us. Relationships between salespeople and prospects and between politicians and voters hinge on a level of trust being established and main- tained. But, while salespeople are opportunistic by nature and as a result tend to be inconsistent, a politician cannot be incon- sistent lest they be accused of flip-flopping on an issue and eroding the electorate’s trust. Thus, building trust can help poli- ticians suppress the more opportunistic urges to which they are sometimes prone. However, being trusted and being popular are two different things for a politician and most interviewees ad- mitted they had to be willing to make unpopular decisions. This is the opposite of opportunism associated with salespeople. Nevertheless, the interviewees were convinced that in taking hard decision they earn the electorate’s respect and long term trust. All interviewees felt empathy was a vital trait for a politician to possess, as it enables them to engage with constituents. The same is true in sales, as the ability to empathize with the pros- pect can help in the selling process. Empathy permits us be sensitive to others’ needs and as such, is a trait central to build- ing relationships and trust. Emphatic listening was something interviewees considered vital in allowing them to connect with constituents. Ego strength, strong self belief, allows people to maintain emotional stability and handle stresses life throws at them. If a salesperson had little ego strength then failure might erode their self confidence and ultimately discourage them from continuing to try to sell. This was the third trait the interviewees recog- nized as necessary for a politician. The ability to bounce back from defeats is critical in politics, as otherwise one’s self con- fidence will be ground down. One needs to have high levels of confidence in oneself to recover from such setbacks. Barrett disliked the stresses elections brought and how they laid failure bare for everyone to see, but he has remained in politics for decades. Regan accepted that failure was part of politics, while Hanafin was very philosophical on earlier setbacks, now re- garding them as va l uable experiences. Positioning and being able to communicate persuasively are important traits for the salesperson. But, they are equally of value in politics. The politicians interviewed seek to position themselves in relation to their constituents’ needs and their parties’ policies. The candidates formulate their policies through a combination of their parties’ market research and their own findings from interacting with constituents. Some- times, this can create a difficult middle ground for the politi- cians to negotiate, as the party wants its candidates to preach a message that constituents might not be interested in listening to —such as FG warnings of a looming economic crisis facing Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 180  D. Ó MEARÁIN ET AL. Ireland in 2007 when everything still seemed fine. Such a find- ing in the political sphere reflects the broader tensions evident in the commercial sphere where central marketing approaches can be at odds with local sales approaches. The domain of what constitutes “marketing” remains a contested space. Hanafin felt presentation was important for a politician—as how they pre- sent themselves shapes the impression created and the position they occupy in the voters’ mind. Sales are a perpetual business where persistence is all impor- tant. The same is true of politics with the advent of the perma- nent campaign. All candidates interviewed recognized that there is a continuous political campaigning cycle that begins at the end of an election. The interviewees felt it necessary to always be in contact with constituents, to be active in the con- stituency and by this means to build relationships with voters. They saw themselves as always campaigning for the next elec- tion. However, this development, along with the PRSTV voting system, has a down side. It contributes to TDs preoccupation with constituency service to the detriment of their role as na- tional legislators, as well as the problem that electoral competi- tion in Ireland is based upon services to the community, as opposed to policy differences. Trust and integrity, empathy, ego strength, positioning and communicating persuasively, and finally persistence—the traits associated with salespeople—were regarded as critically im- portant by the candidates interviewed. However, politicians’ commitment to the behaviours associated with these traits runs deeper than the importance they are given in sales. A politician, especially an incumbent, cannot afford to break the public’s trust under any circumstances, as such a breach, for whatever reason, creates an inconsistency in the public’s mind that could end their careers. The need for empathy is vital as the politician needs to be compassionate to the range of issues constituents present. The politician needs to have large reserves of ego strength, as they have to be able to recover from setbacks, in- cluding election defeats. Politician must know instinctively how to position themselves and be able to communicate in a persuasive manner. And finally, persistence is vial in politics. These findings highlight how the most important traits asso- ciated with salespeople manifested themselves in the behaviors of the politicians interviewed. Just as political parties have looked to the marketing industry for leadership in developing political marketing, politicians have adopted traits similar to those working in sales. A strong point of the findings is the in-depth nature of the interviews—providing an insight into the interviewees’ traits. However, a weakness of the approach is also its qualitative nature (the authors only spoke with 5 candi- dates) and as a result the findings cannot be extrapolated to other candidates. REFERENCES Allen, S. (2010). Being successful at sponsorship sales. Bloomington, IA: Trafford Publishing. Benoit, K., & Laver, M. (2002). Incumbent and challenger campaign spending effects in proportional electoral systems: The Irish elections of 2002. Political Research Quarterly, 63, 159-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1065912908325081 Bianco, W. T. (1994). Trust: Representatives and constituents. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Blumenthal, S. (1982). The permanent campaign. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. Bromiley, P., & Cummings, L. L. (1995). Transaction costs in organi- sations with trust. Research on negotiation in organizations. Bren- wich, CT: JAI Press. Byrne, D. (1997). An overview (and underview) of research and theory within the attraction paradigm. Journal of Social and Personal Rela- tionships, 14, 417- 431. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407597143008 Campbell, J. E. (2000). The American campaign. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Consiglio, C., Picconi, L., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2003). Personalities of politicians and voters: Unique and syn- ergistic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 849-856. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.849 Caprara, G. V., & Zimbardo, P. (2004). Personalizing politics. Ameri- can Psychologist, 59, 581-594. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X Chadwick, A. (2006). Internet politics: States, citizens, and new com- munication technologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chisnall, P. (2005 ). Marketing research. UK: McGraw-Hill. Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA : Sa g e . Dean, D., & Croft, R. (2001). Friends and relations: Long-term ap- proaches to political campaigning. European Journal of Marketing, 35, 1197-1216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006482 Duran, J. J. (2004). Start it, sell it & make a mint. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Erlandson, D. A., Harris, E. L., Skipper, B., & Allen, S. D. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry: A guide to methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Fill, C. (2002). Marketing communication. London: Prentice-Hall. FitzGerald, G. (2002). Reflections on the Irish state. Dublin: Irish Aca- demic Press. Funk, Carolyn L. (1997). Implications of political expertise in candi- date trait evaluations. Political Research Quarterly, 50, 675-697. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/106591299705000309 Gallagher, M. (2005a). Ireland: The discreet charm of PR-STV. In M. Gallagher, & P. Mitchell (Eds.), The Politics of Electoral Systems (pp. 511-532). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gallagher, M. (2005b). Parliament. In J. Coakley and M. Gallagher (Eds.), Politics in The Republic of Ireland, (4th ed., pp. 211-241). Abingdon: Routledge and the PSAI Pre ss. Greenberg, H., Weinstein, H., & Sweeney, P. (2003). How to hire and develop your next top performer: The five qualities that make sales- people great. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Greenberg, J., & Greenberg, H. M. (1976). Predicting sales success- myths and reality. Personnel Journal, 55, 621-627. Greene, J., & Haidt, J. (2002). How (and where) does moral judgment work? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6, 517-523. Griksheit, G. M. Cash, H. C., & Young, C. E. (1994) Handbook of sell- ing: Psychological, managerial and marketing dynamics (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Gronroos, C. (1998). Marketing services: The case of a missing product. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 13, 322-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/08858629810226645 Haan, P., & Berkey, C. (2006). Puffery: Its effects on consumers’ trust in the sales dyad. Innovative Marketing, 2, 122-128. Henneberg, S. C. (2008). An epistemological perspective on research in political marketing. Journal of Political Marketing, 7, 151-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15377850802053158 Henneberg, S. C., O’Shaughnessy, & Nicholas J. (2007). Theory and concept development in political marketing. Journal of Political Marketing, 6, 5- 31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J199v06n02_01 Hetherington, M. J. (1999). The effect of political trust on the presiden- tial vote. American Political Science Review, 93, 311-326. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2585398 Hetherington, M. J. (2005). Why trust matters: Declining political trust and the demise of American liberalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Hogan, R. (1969). Development of an empathy scale. Journal of Con- sulting and Clinical Psychology, 33, 307-316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0027580 Holbrook, M., & O’Shaughnessy, J. (1988). On the scientific status of Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 181  D. Ó MEARÁIN ET AL. consumer research and the need for an interpretive approach to studying consumption behaviour. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 398-402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/209178 Holbrooke, T. M. (1996). Do campaigns matter? Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Hudson, L. A., & Ozanne, J. L. (1988). Alternative ways of seeking knowledge in consumer research. Journal of Consum e r Research, 14, 508-521. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/209132 Ingram, T. N., LaFo rge, R. W., Avila , R. A., Schwepk er, C. H., & Wil- liams, M. R. (2007). Professional selling: A trust-based approach. Mason, OH: Thomson Southw e st e rn. Iyer, R., Graham, J., Koleva, S., Ditto, P., & Haidt, J. (2010). Beyond identity politics: Moral psychology and the 2008 democratic primar y. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 10, 293-306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2010.01203.x Kahn, R. L., & Cannell, C. F. (1957). The dynamics of interviewing: Theory, technique and c ases. New York: Wiley. Karr, R. (2009). Lead, sell, or get out of the way: The 7 traits of great sellers. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118257876 Katz, R. S. (1984). The single transferrable vote and proportional rep- resentation. In A. Lijphart, & B. Grofman (Eds.), Choosing an elec- toral system: Issues and alternatives (pp. 135-145). New York: Praeger Press. Keele, L. (2005). The authorities really do matter: Party control and trust in government. The Journal of Politics, 67, 873-886. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00343.x Killinger, B. (2007). Integrity: Doing the right thing for the right rea- son. Queens University Press. Kotler, P., & Kotler, N. (1999). Political marketing: Generating effec- tive candidates, campaigns and causes. In B. I. Newman (Ed.), Hand- book of political marketing (pp. 3-18). London: Sage Publications. Labor Department. (2010). Occupational outlook handbook. Wa- shington DC: Burea u of Labour Statis tics. Lee, S., & Dubinsky, A. J. (2003). Influence of salesperson characteris- tics and customer emotion on retail dyadic relationships. The Inter- national Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 13, 21-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09593960321000051666 Lees-Marshment, J. (2001). Political marketing and British political parties: The party’s just begun. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Levi, M. (1998). A state of trust. In V. Braithwaite, & M. Levi (Eds.), Trust and governance (pp. 77-101) . New York: Sage. Lilleker, D. G., Jackson, N. A., & Scullion, R. (2006). Introduction. In D. G. Lilleker, N. A. Jackson, & R. Scullion (Eds.), The marketing of political parties (pp. 1-30). Manchester: Manchester University Press. Lilleker, D. G., & Lees-Marshment, J. (2005). Introduction: Rethinking political party behaviour. In D. G. Lilleker, & J. Lees-Marshment (Eds.), Political marketing: A comparative perspective (pp. 1-14). Manchester: Manchester University Press. Lloyd, J. (2006). Square peg, round hole? Can marketing-based con- cepts such as the “product” and the “marketing mix” have a useful role in the political arena? In W. W. Wymer Jr., & J. Lees-Marsh- ment (Eds.), Current issues in political marketing (pp. 27-46). Bing- hamton, NY: Best Business Books. Lynch, K., & Hogan, J. (2012). How Irish political parties are using social networking sites to reach generation Z: An insight into a new online social network in a small democracy. Irish Communications Review, 13, 83-98. Malshe, A. (2010). How is marketers’ credibility construed within the sales-marketing interface? Journal of Business Research, 63, 13-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.01.004 Malshe, A., & Sohi, R. S. (2009). Sales buy-in of marketing strategies: Exploration of its nuances, antecedents, and contextual conditions. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 2 9, 207-226. http://dx.doi.org/10.2753/PSS0885-3134290301 Martin, S. W. (2006). Heavy hitter sales wisdom. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons Inc. Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative researching (2nd ed.) Lond on : S age . Mattes, K., Spezio, M., Hackjin, K., Todorov, A., Adolphs, R., & Al- varez, R. M. (2010). Predicting election outcomes from positive and negative trait assessments of Candidate Images. Political Psychology, 31, 41-58. Matthyssens, P., & Johnston, W. J. (2006). Marketing and sales: Opti- mization of a neglected relationship. Journal of Business & Indus- trial Marketing, 21, 338-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/08858620610690100 Mayer, D., & Greenberg, H. M. (2006). What makes a good salesman? Harvard Business Review, 84, 164-171. McCracken, G. D. (1998). The long interview. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. McGraw, K. M., Lodge, M., & Jones, J. M. (2002). The pandering politicians of suspicious minds. The Journal of Politics, 64, 362-383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00130 Mick, D. G., & Buhl, C. (1992). A meaning based model of advertising experiences. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 317-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/209305 Moloney, K. (2004). Is political marketing new words or new practice in UK politics? Lincol n: Paper presented at the PSA Conference. Newton, K. (2007). Social and political trust. In R. J. Dalton, & H.-D. Klingemann (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political behaviour (pp. 342-361). Oxford: Oxford University Pre s s . http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199270125.003.0018 Oakes, G. (1990). The sales process and the paradoxes of trust. Journal of Business Ethics, 9, 671-679. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00383394 Oliva, R. A. (2006). The three key linkages: Improving the connections between marketing and sales. Journal of Business & Industrial Mar- keting, 21, 395-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/08858620610690155 Ormrod, R. P. (2005). A conceptual model of political market orienta- tion. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, 14, 47-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J054v14n01_04 Ormrod, R. P., & Hennenberg, C. M. (2006). “Are you thinking what we’re thinking?” Or “are we thinking what you’re thinking?” An ex- ploratory analysis of the market orientation of the UK parties. In D. G. Lilleker, N. A. Jackson, & R. Scullion (Eds.), The marketing of political parties (pp. 31-58). Manchester: Manchester University Press. O’Shaughnessy, N. (2001). The marketing of political marketing. European Journal of Marke tin g, 35, 1047-1057. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090560110401956 Peterson, R. M., & Lucas, G. H. (2001). Expanding the antecedent component of the traditional business negotiation model: Pre-nego- tiation literature review and planning-preparation propositions. Jour- nal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 9, 37-50. Polsby, N. W., Wildavsky, A., Schier, S. E., & Hopkins, D. A. (2012). Presidential elections: Strategies and structures of American politics (12th ed.). Lanham, MA: The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Company. Ramsey, R. P., & Sohi, R. S. (1997). Listening to your customers: The impact of perceived salesperson listening behavior on relationship outcomes. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Sciences, 25, 127- 137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02894348 Rasmussen, E. (1999). The 10 traits of top salespeople. Sales and Mar- keting Management, 151, 34-38. Saxe, R., & Weitz, B. A. (1982). The SOCO scale: A measure of the customer orientation of salespeople. Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 343-351. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3151568 Sears, D. O. (1969). Political behavior. In G. Lindzey, & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 315-458). Reading, MA: Addison-We sley. Sinnott, R. (2009). The electoral system. In J. Coakley, & M. Gallagher (Eds.), Politics in the Republic of Ireland (pp. 111-136). Dublin: Routledge and the PSAI Press. Six, F. (2005). The trouble with trust: The dynamics of interpersonal trust building. Nor thampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing Inc. http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9781845426873 Steger, W. P., Kelly, S. Q., & Wrighton, J. M. (2006). Campaigns and political marketing in political science Context. In W. P. Steger, S. Q. Kelly, & J. M. Wrighton (Eds.), Campaigns and political marketing Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 182  D. Ó MEARÁIN ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 183 (pp. 1-10). N ew York: Routledge. Sudulich, L. M., & Wall, M. (2009). Keeping up with the Murphys? Candidate cyber campaigning in the 2007 Irish general election. Par- liamentary Affairs, 62, 456-475. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsp008 Swan, J. E., Trawick, I., & Silva, D. W. (1985). How industrial sales- people gain customer trust. Industrial Marketing Management, 14, 203-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0019-8501(85)90039-2 Walliman, N. (2005). Your research project: A step-by-step guide for the first-time researcher (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications Ltd. Westen, D. (2007). The political brain. New York: Public Affairs. Williams, B. (1988). Formal structures and social reality. In D. Gam- betta (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative Relations (pp. 3-15). Oxford: Blackwell. Zeller, D. (2011). Telephone sales for dummies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing Inc.

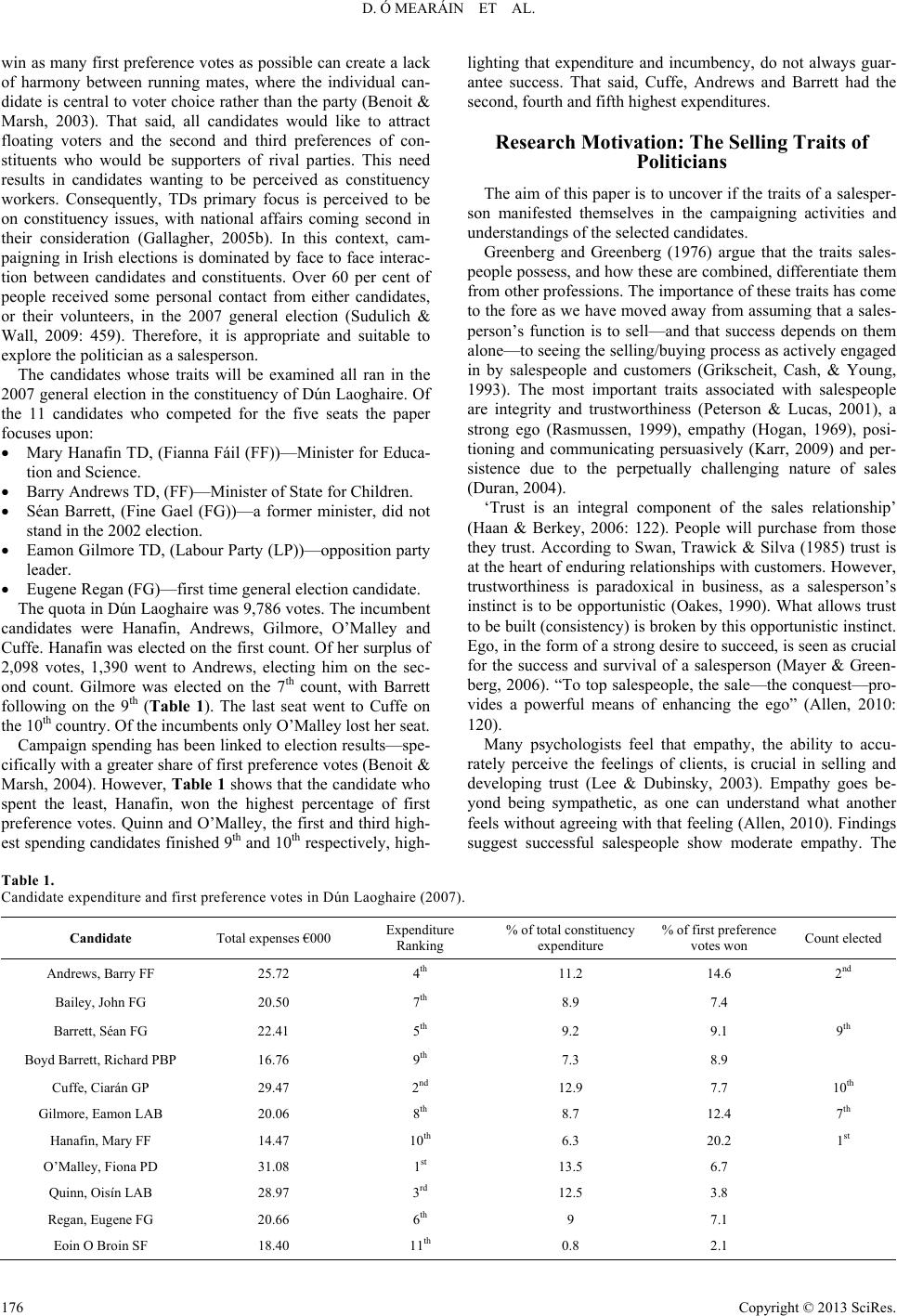

|