American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 2013, 3, 565-572 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2013.36065 Published Online October 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajibm) 565 Strategy of Innovation’s Management in the Pharmaceutical Industry Holds Intellectual Property Cássia Rita Pereira da Veiga, Claudimar Pereira da Veiga, Jansen Maia Del Corso, Anderson Catapan Business School, Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil. Email: anderson@catapancontadores.com.br Received August 2nd, 2013; revised September 2nd, 2013; accepted October 5th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Cássia Rita Pereira da Veiga et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribu- tion License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT In the management of innovation, intellectual property rights assume the primary role. In this sense, this paper aims to describe, with examples, the various strategies used by the pharmaceutical industry in the preservation of their legiti- mate rights of the intellectu al property system. This is an explor atory study by using do cumentary research and longitu- dinal time. Even with the difference in laws between countries, the pharmaceutical anti-competitive practices gain more space in the glob al economy. For patents become political too ls that foster innovation and diffusion of knowledge, it is suggested that revisions in the legislation, homogeneous international regulation and supervision of health authorities ensure quality of product and control of pharmaceutical marketing. This work also addresses political and social con- siderations on the subject while exploring some suggestions of ideal patent system. Keywords: Management of Innovation; Intellectual Property; Patent; Pharmaceutical Industry 1. Introduction In current information society, the management of inno- vation is seen as a key factor to the survival of the or- ganizations that function in high global competition and fast technological advances. The market competition to- day encompasses not only the excellence in the perfor- mance or the technical efficiency, but also the capacity of developing systematic processes through the production and application of knowledge. In the pharmaceutical field, in special, the companies recognize that the available technologies and the pieces of knowledge may come from the internal and external organization limits. The absorptive capacity is funda- mentally important for the creation of new medicines [1]. From this perspective, as much the internal actors as the external can influence the investments of the company in R & D, pushing the limits of the combination opportuni- ties and competences previously disconnected. To promote the continuous science progress, the gov- ernments authorize, for a limited period of time, the ex- clusive right for the creator in the form of patent con- cession. However, on the one hand, there is the increase of the pattern that the right of intellectual property provides an incentive for the production of new knowl- edge through heavy investments in R & D [2], on the other hand, the legislation in force makes that the patent expiration does not coincide necessarily with the loss of market exclusivity [3]. Although it is necessary for any company to recoup the costs of an innovation, it does not happen only during the period of the patent effect. The costs are often recovered after the patent expires if the market strategies of the pharmaceutical industry are well planned [4]. Also, the knowledge disseminated by the patent allows the “invention around of” [5] or “invention among pat- ents” [6], when the strategic benefit is not given to the production of knowledge anymore, but to the adoption and dissemination of the knowledge produced in other companies. In this case, generic versions or incremental innovations can be introduced in the Market by rival companies, which undermines substantially the market share of the medicine in the registered brand. There are innumerous ways for the pharmaceutical companies holders of patents to extend the market mo- nopoly privileges besides the period determined by law and processes that are usually called “evergreening” [7] or “term of the patent restoration” [8]. The majority of Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Strategy of Innovation’s Management in the Pharmaceutical Industry Holds Intellectual Property 566 these strategies are in compliance with the legislation rul- ing, although sometimes they weaken the competitive- ness of the market [7]. In order to prolong the profits, the industry tries to extend the validity of the patent, tries to guarantee new therapeutics indications for the product, tries the medicine’s own drug and, finally, tries to in- crease the portfolio of new products through the proc- esses of merging and acquisition. Meanwhile, in an at- tempt to obtain part of an extremely profitable market, the rival companies launch innovations for the original product, or try to anticipate the commercialization of generics. The current work has its goal to describe, through examples, the diverse strategies used by the pharmaceu- tical industry in the preservation of its legit rights and from the imperatives of the intellectual property’s system. This work is divided into three parts besides this intro- ductory phase. The following describes the methodology of the work and the development theoretical-documental that contemplate the management model of innovation in the pharmaceutical industry and the six strategies used on the market protected by intellectual property’s rights. The final part approaches the political and social consid- erations of these strategies. 2. The Innovation’s Management in the Pharmaceutical Industry On the first half of the 19th century it was already no- ticeable the commercialization of medicines in Europe and in the New World. “This way, even before the emergence of effective medicine, the pharmaceutical business (…) didn’t market products, but promises of cure. In another words, the pharmaceutical industry was born before the medicines” [9] and since the beginning was promis ing i nn ovat i ve solutions. The global pharmaceutical industry appeared only during the decades of 1940 and 1950 with the develop- ment of a higher scale of new products. Despite the im- portance of the innovation for the improvement in the quality of life of a man and for the survival of the phar- maceutical segments, launching a new chemic identity on the market is a hard work, long and full of risks. The development of a new drug takes approximately 11,5 years and consumes 800 million dollars until its approval throughout all the clinical p hases [10]. Furthermore, only one on each five thousand candidates for medicine make it to the market and only one on each one thousand sur- vives the clinical tests and generate the register of a pat- ent. For the assurance of a patent, the government pro- vides exclusive rights for the innovation’s owner during a limited time of 20 years. The concession of a new patent, however, makes pub- lic the information about the invention, and these can be shared by a big number of rival companies. That allow the “invention around of” [5], or “invention among pat0 ents” [6] where the strategy advantage is not given to the knowledge production anymore, but to the adoption and dissemination of the knowledge produced in another companies. The knowledge and competence dissemina- tion can occur also on the researchers technical meetings, chats between employees from rival companies, contrac- tion new employees from competitor companies [11] by the reverse engineering od products with the use of technological platforms or by the analysis of the patents data, scientific articles and the use of specific software [12]. The systemic nature of the innovation process must consider the interactions, cooperation, and exchange in- volving producers, suppliers, and users of the technol- ogy. In addition to these incremental innovations, by the end of the validity for exclusivity con ced ed by th e pa tent, the rival companies can produce chemically identical copies and bioequivalent to the original product, what is called generic medicine. Either through incremental in- novations or generic medicines, the introduction of simi- lar products by rival companies erodes substantially the original medicine’s market share. For this reason, the pharmaceutical industry uses many regulatory ways to extend the patent’s period of application, using legal factors that vary from country to country. In Brazil, the legislation about the expiration of the patent period passed through changes after 1995, when the country joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) and signed the TRIP agreement. Today, the protection of the medicine’s patent is guaranteed by a further maxi- mum of 20 years since the register date in the country where it was the first patent’s deposit. Once the deposit is made in Brazil, eventual subsequent modifications in the patent’s original country don’t apply in Brazilian terri- tory. For this reason, the validity term of the patent in Brazil is not the same as its correspondent abroad. Nev- ertheless, in Brazil, Argentina, Canada, China, Colombia, Ecuador, Hungary, India, Malaysia, Peru, South Africa, and Venezuela, there isn’t a tool of extension for the term of validity, as regulated by the American legislation [7]. Besides, due to the globalization, every country is af- fected direct or indirectly by the economic and social challenges facing other nations. Currently, for the pharmaceutical industry as important as a new medicine is the innovation’s management and the right of Intellectual Property (IP) of the products in place. These practices of management are known as the drugs cycle of life management [10], “evergreening” [7] or “term of patent’s restoration” [8]. Within this process, after the achievement of a patent, a consecutive number of patents for new combinations, use, formulations, and processes of production or molecules are also requested to the regulatory body. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Strategy of Innovation’s Management in the Pharmaceutical Industry Holds Intellectual Property 567 3. Methodological Procedures This study is a research of historical nature, descriptive and documental that used books, periodic, and websites from regulatory entities of intellectual property from many countries. The research problem was approached in a qualitative way justified by the nature of the study ob- ject as well as the procedure used for the data collection. The strategy of both pharmaceutical companies involved with the system of intellectual pro perty were classified in proportion to the risk for the development of a medicine [13], as detailed in Figure 1 and explained on the next section. 4. Data’s Analysis and Description After the Following, the inn ovation’s management in the pharmaceutical industry is exemplified and described. This is a study theme of big importance once the legisla- tion needs to be constan tly reviewed in order to keep the fragile balance between the legit rights and the impera- tives of the intellectual’s property system [7]. 4.1. Delay or Limit the Generic Competition Generic medicines are bioequivalent to the brand prod- ucts, in other words, they are chemically identical and generate the same therapeutics actio n. The generic medi- cines are available by the competition only after they receive the approval of bioequivalence by the competent organ and the expiration of the original patent. They re- late to the low risk of development of pharmaceutical products (Figure 1). Delaying the introduction of a ge- Incremental Innovation New Chemical Entity Current Situation Supergeneric Evergreen Supergenérico Low Low High High Mechanism/Activity Chemical Structure Risck Generic F&A Figure 1. Development of a medicine on the basis of risk. Source: adapted from Grau and Serbedzjia [13]. neric product in one day could mean millions of dollars in profits for a pharmaceutical brand monopoly holder. On average, a patent-off generates a loss of US$2.6 mil- lion a day [14]. This way, the main strategic approach of the patent holders companies includes practices to delay or limit the generics competition in a specific market. The generics industry, on the other hand, seeks defi- ciency on medicine patents of brand such as mistakes, false statements, omissions or inconsistency, in order to truncate the life of the patent and anticipate the access to a potential profit market. The delay of the generics entrance on the market after the patent expiration can occur for many reasons. First of all, there is a necessary time for the medicine to get an approval from the regulating organ. Second, the entrance of generics can be staggered due to the uncertainly around the market opportunities, the real time of the pat- ent validity [4,8 ,14,15] and the reaction of the marketing from the patent holder company, mainly through the re- duction of price of the original brands [4,16]. The delay in the diffusion of generics can also occur because many buyers remain reluctant to adopt a new product until there is enough evidence about the security and quality for the exchange [7,15,16]. Although less frequent, this strategy of defamation is still explored in markets sensi- tive to the perceived quality [3 ,16]. In 2011, in Brazil, according to the National Health Surveillance Agency, before the expiration of the Via- gra’s patent there were already five register registration requests to produce generic medication. By the end of 2013, the pharmaceutical industry of generics will be able to launch products that treat cancer (everolimus, rituximab, imatinibe, capecitabina), migraine (almotrip- tano), psychological distress (ziprasidona), malaria (ato- vaquona), ulvers (famotidine, aprepitante) and trans- plants (sirolimus). 4.2. Preventive Launching of a Generic The model of business of the multinational pharmaceuti- cal companies is highly dependent of the protection of the patent and the rigidity of the rights of intellectual protection. The big pharmaceutical companies are con- stantly treated by the entrance of generic versions of their medicines, making the price of the product increase one fifth of the original price [7]. In order to fight th e loss of receipts, a pharmaceutical company tries to prolong the cycle of life of its drug as much as possible. An alterna- tive is the introduction of its own generic, what is called “authorized generic” [14]. The authorized generic is launched in the same they as the first competitor generic. The titular plan of the patent is to change its profits of short term to net gain in long term. The rational basis for the authorized generic strategy is illustrated on Figure 2. The area OABD represents the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Strategy of Innovation’s Management in the Pharmaceutical Industry Holds Intellectual Property Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM 568 A O DY XC B W Z Drug obsolence Patent expiration Typical generic introdu ction Patent pre-expiration Generic introduction Profits TIME Figure 2. Evaluation of merits relating to the generic introduction. Source: Pearce [14]. profit obtained by the brand company during the period of protection of the patent. When the patent expires, the profits drop drastically until reduced to zero (DCZ). However, if the company plans on introducing a new generic of its medicine before the patent expiration (time Y, point X), the profits of the company on long term will be represented as area OAWXZ. This way, if the receipts with the protected patent of YWBD are estimated to be lower than the receipts of generic YXZ, the company of brand will introduce a generic form of the drug. The strategy of generic substitution allows the patent holder to increase the total profits and to dissuade the generic manufactures to join a specific market [14]. It’s worth highlighting that the fabrication and disclo- sure of the authorized generic can be done by the original patent holder company or by an outsourced organization [4]. The patent holder company preserves its market power for the high margin medicines and avoids the du- plication of costs, especially those associated with the manufacturing, marketing and distribution of a generic brand. The generic manufacturers, on the other hand re- duce the excess of productive capacity when commer- cializing a medicine that holds pharmaceutical market guarant eed [1 4]. In order to fight this competition in the Brazilian mar- ket, in April of 2010, Pfizer set an agreement with the national Eurofarma [17]. Also in 2010, Pfizer bought 40% of the national laboratory Teuto, with the possibility to acquire the full control of the company starting in 2014. Since September from 2010, Teuto started com- mercializing generic versions of Viagra® and Lipitor® [18]. Besides Pfizer, the French laboratory Sanofi-Aventis also entered in the generic market for the acquisition of the national company Medley, process that happened in 2010 [19]. 4.3. Supergenerics Strategy In the decade of 2000, some scientific works started to report a strategic change in the pharmaceutical industry related to the “barrier for generic products”. Against to the commodities generics, which are copies of the origi- nal drugs, the new strategy covers the production of su- pergenerics. These are different from the original product relating to the formula or to the method of administration and, many times, related to the effectiveness. The supergenerics offer a price alternative of high value for the generics because the products are eligible for the protection of the patent and three years of exclu- sivity of the market in the United States [20]. As such, the supergenetics represent better therapeutics entities of fast development, less risks (Figure 1) and, mainly, prof- itable for the pharmaceutical companies [21,22]. Examples of supergenetics involve inhaled versions of capreomicina to treat tuberculosis [22]; nifedipina with slow liberation that reduces the side effects of dizziness, flushing, headache, and edema; fluvastatina that reduces the risk of myopathy and predinisona modified, that re- duces the morning stiffness for patients with rheumatoid arthritis [21]. The performed in an generic to make it a supergeneric can also be performed in original drugs in order to increase the cycle of useful life, strategies really used by the pharmaceutical industry holder of intellectual property, as described below. 4.4. Stratification of Innovation The pharmaceutical companies perform the stratification of their innovations to guarantee a new patenting from a basis product [8,7,14,23]. The goal is submit many pat- ents for the new drug with the purpose of extend its market monopoly and to protect it in many ways against the production of generic medicines. This process is called stockpiling, in another words, the companies store protection for their prod ucts when patenting many attrib- utes of a single innovation and obtain the extension of the exclusivity term for each new patent submitted [7,8, 23].  Strategy of Innovation’s Management in the Pharmaceutical Industry Holds Intellectual Property 569 Through this strategy, the patent holders companies also take advantage of the consumer confidence on the original product brand to “patent a patent” and to con- tinue the innovations [24]. This way, before the original product’s patent expire, the company presents a version supposedly better of the medicine in order to generate a patients commutation. When most of the consumers have already replaced on product by other, the entrance of generic medicines doesn’t generate meaningful loss of market [7,14,23,25]. Many innovations of successor drugs are, in practice, more superficial than the radicals [25]. They depend more on detail accumulation than big technological find- ings and offer low or none advantage about the original medicine. In a general way, it could be aid that a new life cycle of the product can be initiated by the development of a new therapeutics indication, through the administra- tion or use conditions [4]. Other possible types of secon- dary patents are: 1) composition patents, 2) patents of new polymorphs, 3) patents of new formulas, 4) patents of synthesis, 5) patents for new therapeutics regimen, 6 patents of metabolites or pro-drugs and 7) patents for stereoisomers [7,8]. Examples of the use of stereoisomers for new patent- ing are the amoxicillin in 1980 (antibacterial drug), iso- flurane and desflurane in 1992 (inhaled anesthetics), ibu- profen in 1976 (no n-steroidal anti-inflammatory), fluoxe- tine in 1997 (anti-depressive), and omeprazole in 1998 (against hearthburn) [26-28]. An example of the “me- tabolite defense” evolves omeprazole in the decade of 1990. A generic version of Prilosec® (omeprazol, medi- cine for heartburn) was only provided on the market in 2002 despite the expiration of the primary patent antici- pated for 200 1 [25]. In relation to the patents for new therapeutics regimes, it could be mentioned sildenafil (Viagra®), approved by FDA in July 3rd, 2005 for the adjunct treatment of pul- monary hypertension [29]. Pfizer Laboratory continues with diverse studies using the active principle of silde- nafil, it can be to achieve a new therap eutics indication or to an approval of a new pharmacological presentation. Extending the expiration date of a patent through the stratification of the innovation, the innovator company blocks the introduction of generic medicines and extends its exclusivity and profits in the pharmaceutical market [7,8,23]. 4.5. Incremental Innovation In a world where innovations are duplicated quickly, the patenting process is a relatively effective answer to the vulnerability inherent to the product information. The patent doesn’t guarantee full protection to the innovation because itself already reveals the information that, on the other hand, could be protected by a con fidentiality agree- ment. In this contest, the rival companies can use the successor drug strategy to create their own version of innovation, and to enter a new market demonstrably pro- fitable and expandable. Besides this, the companies pro- ducing incremental findings use the advantage of lower costs and risks in relation to the original research [10]. The most known Family of incremental innovations is estantinas, medicines used to reduce the cholesterol level [25]. Estatinas are used to prevent ischemic heart dis- eases and brain vascular diseases, and they are response- ble for the biggest pharmaceutical market in history [1]. The development of estatinas started in 1973 and th e first product of this class was launched on the market in 1987 by the name of Mevacor® (lovastatine) by Merck Sharp & Dohme. In 1991 Pravacol® (pravastatine) by Bristol- Myers Squibb and Zocor® (sinvastatina) by Merk arrived. In 1991, Lípitor® (atorvastatina) by Pfizer was launched and in 2000 Crestor® (rosuvastatina) by AstraZeneca [1]. Currently all estatatinas are already offered as a generic medicine. With the present patent there is only a new class of medicine that has a centered action in the bowel, exetimibe. Other pharmaceutical Market that should be pointed out in relation to the incremental innovation is the seg- ment related to the male sexual impotence. In the d ecade of 1990 researches of Pfizer Laboratory showed that the inhibition of the phosphodiesterase enzyme 5 (PDE-5) increased the volume of blood in the penis. Until now, besides Viagra®, three other inhibiting substances of PDE-5 received the approval of FDA for the male sexual impotence, Levitra® (vardanafil) by Bayer and Cialis® (tadalafil) by Eli Lilly in 2003 and Stendra ® (avanafil) by Vivus Laboratory in 2012. Recently, though still without international expression and without license by FDA, it was launched three other incremental innovation s for the erectile dysfunction: Zydena® (udenafil) by Dong A Farmacêutica Co. Ltda approved in Corea and in the Russian Federation [30], Helleva® (lodenafil) by Cristália Laboratory, approv ed in Brazil in October of 2007 and o Mvix® (mirodenafil) recently licensed in South Korea [30]. Among the diverse PDE-5 inhibitors, the scientific works published until now don’t support differences in the effectiveness profile and security between the prod- ucts. The incremental innovation must prove superiority to the original model or the pharmaceutical company must invest big resources in marketing so the product be- came commercially well succeed. 4.6. Merges and Acquisitions between Pharmaceutical Companies The pharmaceutical industry has been becoming ex- tremely concentrated on the past 15 years due to the high taxes of merges and acquisitions (R & D) from the past two decades. Many of the big pharmaceutical companies Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Strategy of Innovation’s Management in the Pharmaceutical Industry Holds Intellectual Property 570 are today the result of some big merges, including the transnationals processes. Many scientific words demon- strate the existence of mergers waves on the pharmaceu- tical sector, but there isn’t a consensus about the deter- minants of the process. In the neoclassic explanation, the merges waves happen as an answer to regulatory, eco- nomics or technological industrial shocks that require relocation of capital assets on a large scale. In general, the reasons usually used are: the existence of scale economy in R & D, sales, and marketing, reach of global competitiveness, pipeline and products enrichment ac- quisition of new technologies and expansion of corpora- tive control [31]. In the 21st century, in special, the mergers and acquisi- tions were intensified due to the scarcity of pipeline, creation stagnation of new drugs and patent expiration of high sales products [32]. According to IBM Business Consulting Service [33], between 2002 and 2007, the patents of 35 blockbusters expired generating a billing loss of US$73 billion for the pharmaceutical companies and the loss of more than 200 .000 job s in the pa st 5 years [32]. On this occasion, Pfizer became the biggest phar- maceutical company in the world by using a notable se- quence of acquisitions. These results, however, didn’t show strength, instead, they are deriving from a threat: the patent expiration of some medicines of high sales, such as Lipitor® and Viagra® [34]. Using this same strat- egy, in 2009, Pfizer bought Wyeth and created a new structure of 71 billion dollars on annual sales and the reduction of operational costs of 4 billion dollars [34]. Besides Pfizer, other big companies of the pharmaceu- tical sector such as GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, San- ofi-Aventis and MSD are result of the union of compa- nies that kept their last names in the same time as they add others. 5. Final Considerations In the management of innovations, the rights of intellec- tual property assume a primary role. The intellectual property is based on the idea that the exclusivity of mar- ket is necessary to create motivation to the innovation, but the expiration of the patent, and specially the compe- tition created by it, is also necessary to guarantee the diffusion of innovations and their social benefits [2,3,35]. There were big changes in the patents system during the past two decades, and the majority of them on the same direction: the expansion and the reinforcement of the in- vention’s protection. In the same way, recent tendencies in the system of patents indicate a weakness in pat- entability requirements [35]. Medicines aren’t any commodities, but an element necessity to keep the health of the population. At this point the conflict of interest starts, sin ce there is the right of the pharmaceutical industry in obtaining benefits that incentive the investments in research, while on the other hand there is the right of health, on which all human be- ings should enjoy. Questions about the cost of research, price practiced by the pharmaceutical companies and ideal level of protection of the patent system are in the forefront of ongoing politic debates. In every case, the central question spines around of the achievement of appropriate balance between the IP and the access of health treatment. In order to benefit this delicate balance, the innovator companies use many strategies to protect and apply their rights of intellectual property. The preference for the generic product launching by the patent holder shows particular promise, since it guarantees a considerable flux of income, keeping the costs of production low, and dis- suade the generic companies to enter market. The strati- fication of the innovations generally involves low risks of failure of the product and the rejection of the market. However, it’s also used to bring less financial return it it’s not made a good marketing with the doctor’s class. This strategy is advisable when the market niches iden- tify themselves with the adapted version of the product, or when the number of clients is enough in size and fi- nancial capacity, to support the additional costs. The mergers and acquisitions can generate scale economy, global competitiveness reach, enrichment of pipeline, acquisition of new technologies and expansion of corpo- rative control, although can also generate the destruction of values for the shareholders and overestimation of effi- ciency gains. Generics, in turn, represent the new phar- maceutical market reality. With the decline of efficiency of R & D activities in the past 15 years, the models of traditional business are giving place to the management of the life cycle. Besides every strategy used by the companies to prolong the validity of their patents, the generics will occupy the high profitable pharmaceutical market of blockbusters. However, even the generic com- panies need to worry about future profits. Soon, many products will be supplied as generics, what will generate competition in prices and lower return abou t inve stments. On this situation, the supergenerics can represent an al- ternative strategy. These strategies are summarized in Table 1. The majority of the strategies used by the patent holder companies are clearly in conflict with the purpose of the intellectual property system, which isn’t to protect the inventor, but to promote the development through crea- tivity. These strategies eliminate the noble intention of the patent law when using the existent gaps in the regula- tion. These practices, although according to the law, are anti-competitive and against the interest of the consu mer. The pharmaceutical industry is aware of its importance as a strategic sector in the national economy, that’s why it puts strong political and economic pressure in the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Strategy of Innovation’s Management in the Pharmaceutical Industry Holds Intellectual Property 571 Table 1. Strategy of Inovation. Strategy Feature Delay or limit the generic competition Markets sensitive to perceived quality. Preventive launching of a generic Change its profits of short term to net gain in long term. Supergenerics Strategy Offer a price alternative of high value for the generics because the products are eligible for the protection of the patent and three years of exclusivity of the market in the United States [20]. Stratification of innovation Guarantee a new patenting from a basis product [7,8,14,23]. Incremental Innovation The rival companies can use the suc- cessor drug strategy to create their own version of innovation, and to enter a new market demonstrably profitable and expandable. Merges and acquisitions between pharmaceutical companies The existence of scale economy in R & D, sales, and marketing, reach of global competitiveness, pipeline and products enrichment acquisition of new technologies and expansion of corporative control [31]. management of its own interests. To combat the anti- competitive strategy diffusion used by the pharmaceuti- cal industry, constant reviews of the existing regula- tions are necessary in order to verify the failures that could be explored. The legal system should also be aware of these strategies so the courts can be faster on their decisions to avoid the extension of the patent’s validity only because of the delays in justice [7]. The health authorities could guarantee the security about the therapeutics equivalence between brand prod- ucts and generics and, in the same time, reduce the per- suasive advertisements of the brand medicines, not through bureaucratic imposition, but limiting the ex- penses of the companies with pharmaceutical marketing. Finally, there is also the necessity of international ho- mogeneous regulation about the intellectual property right, mainly due to the market globalization. The dis- crepancy of regulation among the countries creates dis- parity of treatment among inventors of different regions and complicates the work of examiners, what leaves open space for the dispute. Therefore, to become a political instrument that aim encourage the innovation and diffusion of knowledge, the patents should maybe present a menu of different degrees of protection [35], with the selected evaluation and compensation due to the inventive value and to the effort destined to the R & D pro cess. The pa tenting crite- rion, as novelty and not obviousness, should be strict enough to avoid the concession of patents for the inven- tions with low social value, which only increase the sys- tem’s costs. At the same time, the protection force of the intellectual property system should provide enough in- centives for the unique development of high social value inventions. Even though this theme was already explored in an- other scientific works, it treats about a complex subject that requires new investigations, mainly because the pat- ent system does not represent an incentive for all kinds of inventions, as well as the great level of patent protection may differ between the different technological fields [35]. Finally so the system of ideal system became true, the legislation needs to be constantly reviewed to keep the fragile balance between legit rights and the imperatives of the intellectual property [7]. To build a fair society, it’s urgent a new innovation order in the health manage- ment, based in the rupture of ruling systems and with new and real opportunities of economic growth. 6. Conclusion In the academic literature there are many examples of strategies used by the pharmaceutical industry in the postponement of its patents, but many of the research questions aren’t answered yet. The realization of other studies may contribute to the validation of the necessity of improvement of technical guidelines of the patents and, consequently, of the innovations management. REFERENCES [1] Y. Baba and J. Walsh “Embeddedness, Social Episte- mology and Breakthrough Innovation: The Case of the Development of Stations,” Research Policy, Vol. 39, No. 4, 2010, pp. 511-522. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.016 [2] G. Dosi, L. Marengo and C. Pasquali, “Ho w Much Should Society Fuel the Greed of Innovators? On the Relations between Appropriability, Opportunities and Rates of In- novation,” Re search Policy, Vol. 35, No. 8, 2006, pp. 1110- 1121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.09.003 [3] G. Duflos and F. R. Lichtenberg, “Does Competition Stimulate Drug Utilization? The Impact of Changes in Market Structure on US Drug Prices, Marketing and Utilization,” International Review of Law and Economics, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2012, pp. 95-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2011.08.003 [4] M. Agrawal and N. Thankkar, “Surviving Patent Ex- piration: Strategies for Marketing Pharmaceutical Prod- ucts,” Journal of Product & Brand Management, Vol. 6, No. 5, 1997, pp. 305-314. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10610429710179471 [5] S. G. Winter. “Conhecimento e Competência Como Ati- vos Estratégicos,” In: D. A. Klein, Ed., A Gestão Estraté- gica do Capital Intellectual, Qualitymark Editora, Rio de Janeiro, 1998, pp. 251-286. [6] F. R. Lichtenberg and T. J. PhilipsoNo. “The Dual Effects of Intellectual Property Regulations: Within- and Be- tween- Patent Competition in the US Pharmaceuticals Industry,” NBER Working Paper Series, 2002. http://www.nber.org/papers [7] G. Dwivedi, S. Hallihosur and L. RangaNo, “Evergreen- ing: A Deceptive Device in Patent Rights,” Technology in Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  Strategy of Innovation’s Management in the Pharmaceutical Industry Holds Intellectual Property Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM 572 Society, Vol. 32, No. 4, 2010, pp. 324-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2010.10.009 [8] D. S. Fernandez and J. T. Huie, “Balancing US Patent and FDA Approval Processes: Strategically Optimizing Mar- ket Exclusivity,” Drug Discovery Today, Vol. 9, No. 12, 2004, pp. 509-512. [9] J. C. Gerez, “Indústria Farmacêutica: Histórico, Mercado e Competição,” Ciência Hoje, Vol. 15, No. 89, 1993. pp. 21-30. [10] C. Sternitzke, “Knowledge Sources, Patent Protection, and Commercialization of Pharmaceutical Innovations,” Research Policy, Vol. 39, No. 6, 2010, pp. 810-821. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.03.001 [11] D. M. Carolis, “Competencies and Imitability in the Pharmaceutical Industry: An Analysis of Their Relation- ship with Firm Performance,” Journal of Management, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2003 pp. 27-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014920630302900103 [12] S. Gupta, “Diffusing Knowledge-Based Core Competen- cies for Leveraging Innovation Strategies: Modeling Outsourcing to Knowledge Process Organization (KPOs) in Pharmaceutical Networks,” Industrial Marketing Man- agement, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2009, pp. 219-227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarmaNo.2008.12.010 [13] D. Grau and G. Serbedzjia, “Innovative Strategies for Drug Repurposing,” Drug Discovery & Development, 2007. http://www.dddmag.com/articles/2007/09/innovative-strat egies-drug-repurposing. [14] J. A. Pearce, “How Companies Can Preserve Market Dominance after Patents Expire,” Long Range Planning, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2006, pp. 71-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lrpp.2005.04.006 [15] A. T. Ching, “Consumer Learning and Heterogeneity: Dynamics of Demand for Prescription Drugs after Patent Expiration,” International Journal of Industrial Organi- zation, Vol. 28, No. 6, 2010, pp. 619-638. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2010.02.004 [16] J. Hudson, “Generic Take-Up in the Pharmaceutical Market Following Patent Expiry: A Multi-Contry Study,” International Review of Law and Economics, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 205-221, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0144-8188(00)00030-2 [17] A. Vieira, “Pfizer Fecha Parceria com a Eurofarma,” Desenvolva, 2010. http://www.treinamentosparafarmacia.com/2010/04. [18] Valor Econômico, “Teuto Investe para Duplicar a Pro- dução de genÉrico,” 2011. http://www.dignow.org/post. [19] M. Scaramuzzo, “Pfizer e Sanofi vão Exportar Genéricos do Brasil para a AL,” Valor Econômico, 2012. http://clippingmpp.planejamento.goVol.br/cadastros/notic ias/2012/4/26/pfizer-e-sanofi-vao-exportar-genericos-do- brasil-para-al. [20] S. A. Charles, “Supergenerics: A Better Alternative for Biogenerics,” Drug Discovery Today, Vol. 10, No. 8, 2005, pp. 533-535. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03410-0 [21] S. Stegemann, “Improved Therapeutic Entities Derived from Known Generics as an Unexplored Source of Inno- vative Drug Product,” European Journal of Pharmaceu- tical Science, Vol. 44, No. 4, 2011, pp. 447-454. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2011.09.012 [22] A. Schoubben, “Capreomicin Supergenerics for Pulmo- nary Tuberculosis Treatment: Preparation in Vitro, and in Vivo Characterizati on,” European Journal of Pharmaceu- tics and Biopharmaceutics, Vol. 83, No. 3, 2013, pp. 388-395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.11.005 [23] D. I. Gorlin, “Staving off Death: A Case Study of the Pharmaceutical Industry’s Strategies to Protect Block- buster Franchise,” The Food and Drug Law Journal, Vol. 63, 2005, pp. 1-51. [24] T. X. Witkowski, “Intellectual Property and Other Legal Aspects of Drug Repurposing,” Drug Discovery Today: Therapeutic Strategies, Vol. 8, No. 3-4, pp. 131-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ddstr.2011.06.008 [25] M. Angell, “A Verdade Sobre os Laboratórios Far- macêuticos: Como Somos Enganados e o que Podemos Fazer a Respeito,” 3rd Edition, Editora Record, Rio de Janeiro, 2008. [26] I. Agranat and H. Caner, “Intellectual Property and Chirality of Drugs,” Drug Discovery Today, Vol. 4, No. 7, 1999, pp. 313-321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6446(99)01363-X [27] H. Caner, “Trends in the Development of Chiral Drugs,” Drug Discovery Today, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2004, pp. 105-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02904-0 [28] I. Agranat and S. R. Wainschtein, “Th e Strategy of Enan- tiomer Patents of Drugs,” Drug Discovery Today, Vol. 15, No. 5-6, 2010, pp. 163-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2010.01.007 [29] B. Cremers and M. Bohm. “Non Erectile Dysfunction Application of Sildenafil,” Herz, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2003, pp. 325-333. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00059-003-2473-0 [30] E. R. MacNamara and C. F. Donatucci, “Newer Phos- phodiesterase Inhibitors: Comparison with Established Agentes,” Urologic Clinics of North America, Vol. 38, 2011, pp. 155-163. [31] S. Shibayama, “Effect of Mergers and Acquisitions on Drug Discovery: Perspective from a Case Study of a Ja- panese Pharmaceutical Company,” Drug Discovery To- day, Vol. 13, No. 1-2, 2008, pp. 86-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2007.10.015 [32] I. Khana, “Drug Discovery in Pharmaceutical Industry: Productivity Challenges and Trends,” Drug Discovery Today, Vol. 17, No. 19-20, 2012, pp. 1088-1102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2012.05.007 [33] IBM Business Consulting Service. http://www-935.ibm.com. [34] Revista Exame, “Setor Farmacêutico Mantém Ritmo de Fusões e Aquisições,” 2010. http://www.consultaremedios.com.br/noticia.php? [35] D. Encaoua, D. Guellec and C. Martínez, “Patent Systems for Encouraging Innovation: Lessons from Economic Analysis,” Research Policy, Vol. 35, 2006, pp. 1423-1440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.07.004

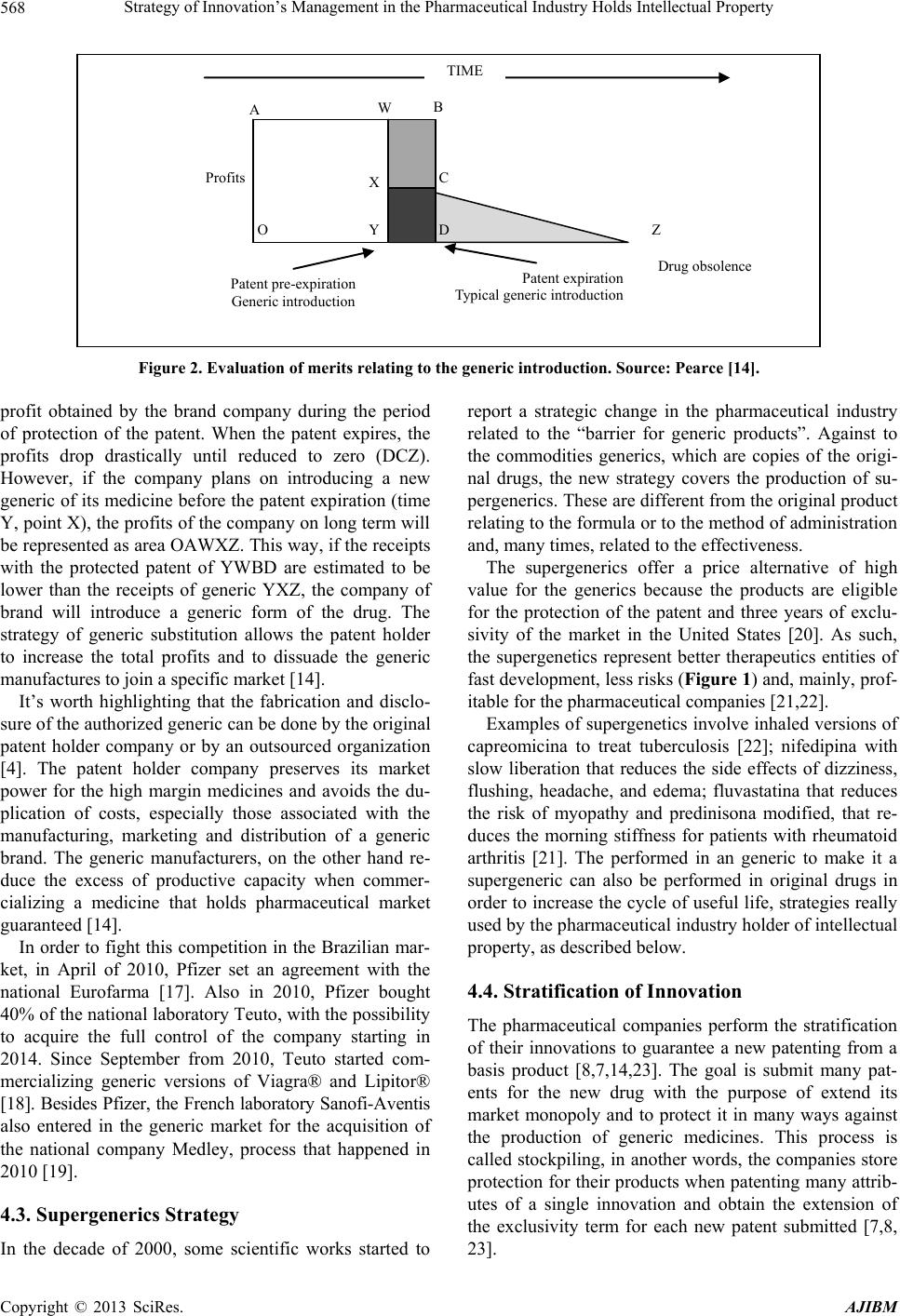

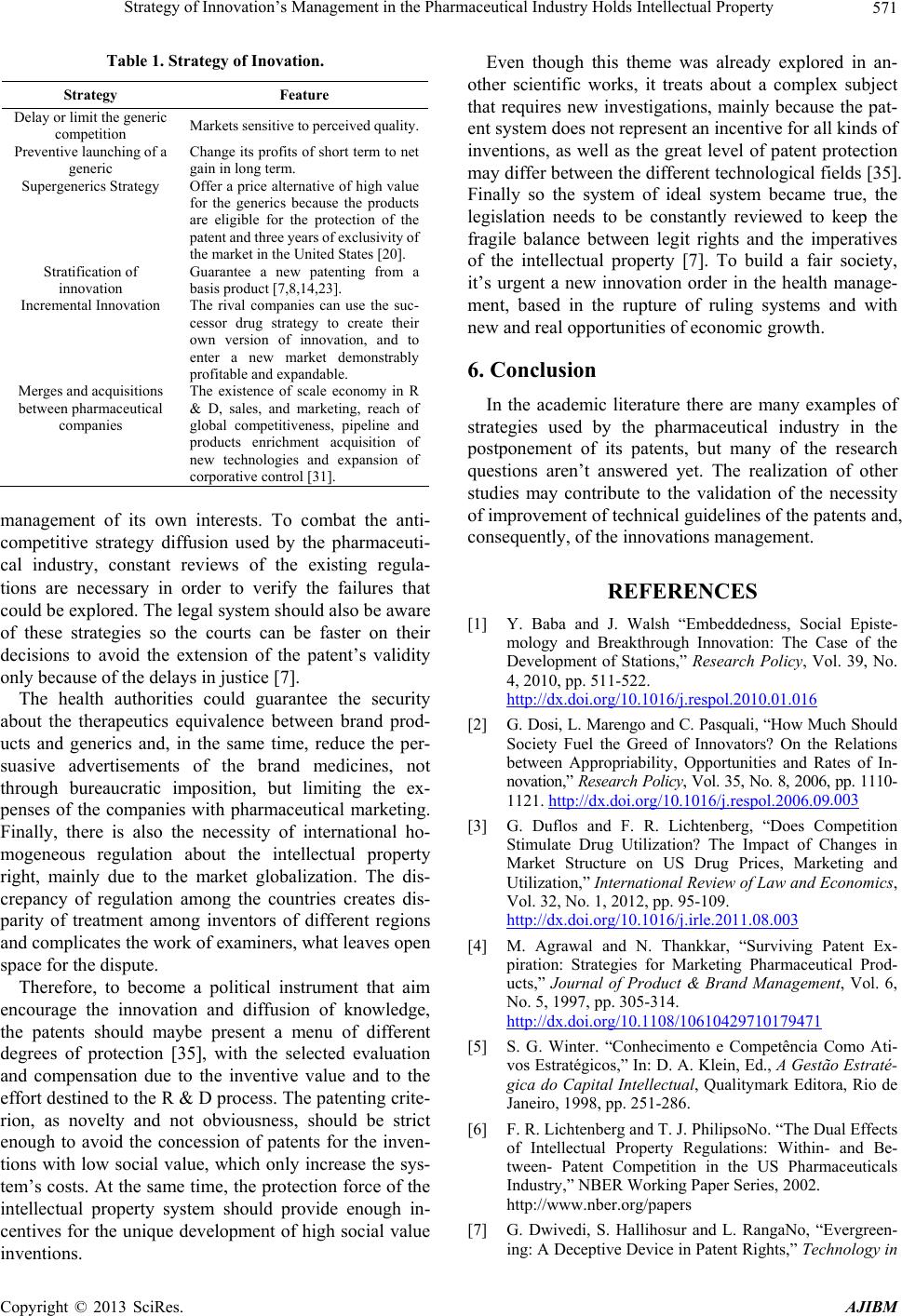

|