Theoretical Economics Letters, 2013, 3, 292-296 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/tel.2013.35049 Published Online October 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/tel) Cash-in-Advance Constraint with Status in a Neoclassical Growth Model Ken-ichi Kaminoyama1*, Taketo Kawagishi2 1Department of Economics, Doshisha University, Kyoto, Japan 2Faculty of Economics, Tezukayama University, Nara, Japa n Email: *obenberg1029@hotmail.co.jp, tkawagishi@tezukayama-u.ac.jp Received August 22, 2013; revised September 25, 2013; accepted October 7, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ken-ichi Kaminoyama, Taketo Kawagishi. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT In this paper, we assume that a cash-in-advance (CIA) constraint itself depends on relative income, which implies the status. This constraint means that agents with higher income are more creditworthy and can make purchases with fewer money holdings. Under this assumption, we construct a one-sector neoclassical growth model and show that there exists a unique steady state that has saddle-path stability without specifying each function. Furthermore, we examine the ef- fects of money growth on capital accumulation. If the status elasticity of CIA constraint is large, the Tobin effect can arise. In contrast, if it is small, the anti-Tobin effect can arise. Keywords: Cash-in-Advance Constraint; Status; Money Growth; Neoclassical Growth Model; Tobin/Anti-Tobin Effect 1. Introduction There is a growing macroeconomic literature that exam- ines the effects of inflation (money growth) on capital accumulation. Tobin [1] regards money as a substitute for capital and concludes that money growth accelerates capital accumulation, known as the Tobin effect. There- after, many studies have discussed the effects of money growth in the context of cash-in-advance (CIA hence- forth) constraints. For example, Clower [2] and Lucas [3] show that if the CIA constraint applies only to consump- tion, then money growth has no effect on capital accu- mulation in the long run, known as the superneutrality of money. On the other hand, Stockman [4] considers a standard neoclassical growth model with the CIA con- straint applying to both consumption and investment, and shows that money growth decreases capital accumulation. This is because after the period of higher inflation the net rate of return on capital falls. In this case, the level of capital and the money growth rate are negatively corre- lated. This is referred to as the anti-Tobin effect. Recent studies on neoclassical growth models with CIA constraints capture the role of status in terms of a social device providing priority in the nonmarket goods sector, seen in Cole et al. [5].1 In this context, Chang et al. [8], Gong and Zou [9], and Chang and Tsai [10] in- troduce status, defined as capital holdings, into prefer- ences.2 Under the Clower-Lucas-type CIA constraint, Chang et al. [8] confirm that money growth and the steady-state level of capital are positiv ely correlated. It is because higher inflation increases the cost of money holdings, that the agent shifts his/her assets from money to capital, which provides utility. On the other hand, Gong and Zou [9] employ the Stockman-type CIA con- straint and show that whether money growth promotes capital accumulation or not depends on the measure of the agent’s desire for status.3 In a similar vein, Chang and Tsai [10] find that when the status seeking effect dominates the inflation tax effect, money growth and the steady-state capital stock are positively correlated under the general-type CIA constraint, which means that whole consumption and a positive fraction of investment are 1Zou [6] interprets utility from capital in terms of the spirit of capital- ism, based on Weber [7], and shows that endogenous growth can arise even if the interest rate is smaller than the time preference rate. 2This type of preferences had already been constructed mathematically by Kurz [11]. 3Gong and Zou [9] analyze the effects of money growth in the case o the Clower-Lucas-type CIA constraint and that of the Stockman-type CIA constraint. Under the Clower-Lucas-type CIA constraint, Gong and Zou [9] obtain the same results as in Chang et al. [8]. *Corresponding a uthor. C opyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  K. KAMINOYAMA, T. KAWAGISHI 293 purchased using real money balances. In this paper, on the other hand, we capture the status in terms of social credibility when making purchases. Specifically, we embody this concept by assuming that individuals with higher income (higher status) are more creditworthy and can make purchases with fewer money holdings. Avery et al. [12] show that high income indi- viduals use cash and cash plus checks for a smaller frac- tion of their total transactions than low income individu- als; and Wolff [13], Kessler and Wolff [14], and Ken- nickell and Starr-McCluer [15] find that the fraction of household wealth held in liquid assets decreases with income and wealth. Hence, in the present study, we as- sume that the CIA constraint itself depends on relative income, which implies status, and that this CIA constraint applies to consumption and investment. Under such a CIA constraint, we consider a neoclassical growth model and clarify how status has an impact on the relationship between the rate of money growth and the steady-state level of capital, as well as a uniqueness of the steady state and its stability. 2. Model 2.1. CIA-Status Constraint The representative agent faces the following CIA con- straint: ,0< ,1, ci ci mlcli ll (1) where is consumption, i is investment, and m is real money balances defined as nominal money balances divided by the price level.4 In addition, c and i l are the ratios of consumption and investment goods which require cash, respectively. c l From the observations mentioned in the Introduction (Avery et al. (1987) etc.), we assume that c and depend on the agent ’s credit when makin g purcha se s: li l ,,0 ci yy llx yy 1,x (2) where and y are private income and average in- come in the economy respectively, and yy stands for the agent’s own relative income.5 Note that we regard relative income as status. Add itionally, represents the relative strength of the liquidity constraint applying to investment expenditure. Along the lines of the standard CIA literature, we assume that the liquidity constraint on consumption is stricter than that on investment. More- over, we posit that is decreasing and convex with respect to yy: 0, 0. yy yy (3) From (1) and (2), we have . y mc y xi (4) In the following analysis, we impose (4), referred to as the CIA-status constraint. 2.2. Optimal Conditions and Dynamic System The economy is inhabited by a continuum of identical, infinite-lived agents endowed with a unit of labor. The size of the population is constant and is normalized to unity. Each agent consumes a continuum of non-perish- able consumption goods produced with a simple neoclas- sical production technology. We assume that each con- sumption commodity is perfectly complementary. The representative agent maximizes the following lifetime utility: 0ed, t uc t (5) where u is an instantaneous utility function which satisfies >0u, <0u and the Inada conditions 00 ,lim limcc uc uc . In addition, 0 is the constant rate of time preference. The budget constraint of the repr esentative agent is ,mfkcim (6) where is capital stock and k is the rate of inflation. Output is produced using a neoclassical production func- tion, , satisfying , and the Inada conditions f>0 <0f 0 limkk 0fk , limkf . The law of motion of capital stock is 0 ,given >0.ki k (7) For simplicity, the depreciation rate of capital is as- sumed to be zero. In (6), is the seigniorage that the agent receives from the monetary authority as a lump- sum transfer: ,m (8) where is the constant, time-invariant money growth rate. By using , the nominal money supply, , is expressed as 0 e,given> 0. t t MM M 0 (9) Assuming a representative agent and a neoclassical technology, from (4), we find that the CIA-status con- straint becomes 4To simplify the notation, we drop the time index from each variable. 5Note that, from (1) and (2), 0,1 . Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  K. KAMINOYAMA, T. KAWAGISHI 294 , fk mc fk xi (10) where k is average capital stock in the economy. The representative agent maximizes (5) subject to (6), (7) and (10). In this problem, the representative agent is assumed to take the sequences, 0 tt k , as given. To derive the necessary conditions for an optimum, we set up the following current-value Hamiltonian function: , Hucfk cim fk im cxi fk where and are the shadow prices of real money balances and the capital stock, respectively, and is the Lagrange multiplier associated with the CIA-status constraint (10). The first-order conditions for optimiza- tion are given as follows: , fk uc fk (11) , fk xfk (12) , fkfk fk cxi fk fk (13) , (14) and the transversality conditions for and m are k e lim t tk 0, 0 capital stock in the economy: (15) e lim t tm . (16) Equation (11) implies that the marginal utility of con- sumption equals the marginal cost of consumption, which is the marginal utility of having an additional unit of real money balances. Equations (12) and (13) together indicate the evolution of capital over time, where the last term on the left-hand side in (13) represents the mar- ginal benefit from the higher income position (i.e. higher status). This benefit implies that the agent gets relatively higher credibility and can make purchases with fewer money holdings. Equation (14) implies that the marginal value of real money balances equals the marginal cost. Since the agents are assumed to be symmetric and the size of the population is unity, in equilibrium, the level of the agent’s capital stock is equal to the average level of .kk (17) Additionally, in equilibri an um, the goods market clears, d money demand is equal to money supply: ,kfkc (18) .m m We assume that the CIA const in (19) raint is always binding equilibrium, as is common in the CIA literature. Thus, from (10) and (1 7), we get c 1m .xi (20) From (7) and (11) - (20), we obta na in the following dy- mic system after some manipulation: 111 1 1, xfk k cD x fk xc uc fk xuc fk uc xfkxcfk (21) 1 1, 1 uc fkkxc xfkx c (22) ,kfkc (23) where 2 1<0, 1 x Dxuc xfkx c 1>0. 1 Note that expresses the elasticity of the CIA con- st s ady state and its sta- raint with repect to status. 2.3. Steady State and Stability In this subsection, we consider a ste bility. In a steady state, the economy is characterized by 0ckm . Substituting this condition into (2ting them, we obtain 1)-(23) and calcula *11fk 11 x . (24) Since the production function, a , satisfies concav- ity and the Inada conditions, we haveunique solution, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  K. KAMINOYAMA, T. KAWAGISHI 295 *, which represents the steady-state level of capital. Equation (24) implies that when the CIA constraint itself ends on status >0 , the steady-state level of capital is not determined only by the constant rate of time preference (i.e. the d golden rule k dep modifie fk does not hold), even if the CIA constraint applies only to consumption 0x. In this case, the leve hinges on money growth, that is, the superneutrality of money is not n the next section, we conduct the analysis concerning the effects of money growth on capital stock and consumption. Next, we consider the stability of the steady state. Linearizing the dynamic syste l of capital ) around the valid. I m (21)-(23 steady state, we obtain the following relationships among the three characteristic roots, 1 , 2 and 3 (note that c* represents the steady-state level of consumption):6 12 3 1xfkuc ggg 1 Df fk D 0, 1 k uc x (25) 123 11 0, c (26) 1 fku ggg re D whe 2 1 d (26) t one negati <0 . dicate that the dy- positive eigen- 11 xu c xucfk Equations (25) anogether in ic system has ve and two D nam values. Since consumption, c, and the shadow price of real money balances, , are jumpable variables and capital stock, k, is a state vriable, the steady state ex- hibits the saddle-point stability. Proposition. In a neoclassical growth model with the CIA-status constraint (4), the a 1re exists a th on Ca unique steady pital Stock state that is saddle-path stable. 3. Effects of Money Grow In this section, we clarify how money growth affects the steady-state level of capital stock and that of consump- tion in our framework. From (24), we have * d d k0. Expressions (27) indicate that when t of the CIA constraint, (27) he status elasticity , of th is great the relative strength e liquidity constraint applying er (resp. smaller) than to investment expenditure, , an increase in the rate of money growth, , induces an increase (resp. a decrease) in capital stock. The positive (resp. negative) relationship between the rate of money growth and capital stock can be considered as the presence of the Tobin (resp. the anti-Tobin) effect. These results can be interpreted through the relation- ship between the benefit of holding additional capital stock and the cost of purchasing investment goods. Here, the benefit is generated from the status enhancement ef- fect, which arises when the agent makes the CIA con- straint less restricted by investing more. This benefit can be captured through the parameter . On the other hand, the cost is caused by the inflation tax effect, which oc- curs when the agent purchases investment goods after the policy of raising money growth indes higher inflation. This cost can be measured by the parameter uc . The intuition is as follows. Suppose that the economy is in the steady state initially, and that the rate of money growth rises. When is greater than , the status en- hancement effect dominates the inflation tax effect; that is, the benefit of holding additional capital stock gener- ated from the status enhancement effect is greater than the cost of purchasing investment goods caused by the inflation tax effect. In this case, if the agent holds addi- tional capital stock, his/her income increases, so that he/she obtains higher status and holds less money bal- ances through the CIA-status constraint. This implies that the agent can avoid paying the higher inflation tax caused by the money growth on the future consumption, which leads to an increase in the future real consumption. Thus, since the net rate of return on capital in utility terms in- creases, the agent shifts his/her demand from current consumption to capital stock.7,8 As a result, a rise in the money growth rate accelerates capital accumulation, which leads to an increase in output and that in consump- tion in the long run. In contrast, when is smaller than , the inflation tax effect dominates the status enhancement effect. Thus, an increase in money growth depresses the steady-state leh evel of capital, whicleads to a decreas in output and that in consumption in the long run. Proposition 2. In a neoclassical growth model with the CIA-status constraint (4), if the status elasticity of the 7Actually, as the third effect, there is the inflation tax effect on pur- chasing current and future consumption goods. When 0x , we can extract only this third effect. However, Stockman (1981) focuses on this case and shows that the net rate of return on capital in utility (consumption) terms is unaffected by higher inflation. Thus, we ignore this third effect. 8Note that the agent obtains the higher net rate of return on capital by investing more and enhancing his/her status. 6Details for the linearization of the dynamic system are available from the authors on request. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  K. KAMINOYAMA, T. KAWAGISHI Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL 296 ) than the relative st CIA constraint is greater (smaller rength of the liquidity constraint applying to investment expenditure (i.e. >< ), then a rise in the money growth rate increases (decreases) the steady-state level of capital and that of consumption. 4. Conclusions This paper has investigated a neoclassical growth model int and itself depends on relative i s status. Under this assumption, we h function, and 2) the To t s referee, who gave us help- while we were writing this [1] J. Tobin, “Money and Economic Growth,” Econometrica Vol. 33, No. 4 http://dx.doi.o with a CIA constra come, which implien- have examined how status, which affects the CIA con- straint, has an impact on the relationship between mo- ney growth and capital stock, as well as a uniqueness of the steady state and its stability. Und er the CIA-status constraint, we have shown that 1) there exists a unique steady state that has saddle-path stability without specifying eac bin or the anti-Tobin effect arises depending on the magnitude relationship between the status elasticity of the CIA constraint and the relative strength of the liquid- ity constraint applying to investment expenditure. 5. Acknowledgements We would like to express our profound gratitude o Ka- zuo Mino and the anonymou ful and valuable comments paper. REFERENCES , , 1965, pp. 671-684. rg/10.2307/1910352 [2] R. W. Clower, “A Reconsideration of the Microfounda- tions of Monetary Theory,” Weste Vol. 6, No. 1, 1967, pp. 1-8. rn Economic Journal 65-7295.1980.tb00570.x , [3] R. E. Lucas, “Equilibrium in a Pure Currency Economy,” Economic Inquiry, Vol. 18, No. 2, 1980, pp. 203-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.14 [4] A. C. Stockman, “Anticipated Inflation and the Capital Stock in a Cash-in-Advance Economy,” Journal of Mo tary Economics, Vol. 8, No. 3, 1981, pp. 387-393. ne- http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(81)90018-0 [5] H. L. Cole, G. J. Mailath and A. Postlewaite, “Social Norms, Savings Behavior, and Growth,” The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 100, 1992, pp. 1092-1125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/261855 [6] H. F. Zou, “‘The Spirit of Capitalism’ and Long-Run Growth,” European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 10, No. 2, 1994, pp. 279-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0176-2680(94)90020-5 [7] M. Weber, “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capi- tatus, talism,” Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1958. [8] W. Y. Chang, Y. N. Hsieh and C. C. Lai, “Social S Inflation and Endogenous Growth in a Cash-in-Advance Economy,” European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2000, pp. 535-545. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0176-2680(00)00011-2 [9] L. Gong and H. F. Zou, “Money, Social Status, and Capi- tal Accumulation in a Cash-in-Advance Model,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 33, No. 2, 2001, pp. 284-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2673886 [10] W. Y. Chang and H. F. Tsai, “Money, Social Status, and Capital Accumulation in a Cash-in-Advance Model: A Comment,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 35, 2003, pp. 657-661. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/mcb.2003.0027 [11] M. Kurz, “Optimal Economic Growth and Wealth Ef- fects,” International Economic Review, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1968, pp. 348-357. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2556231 [12] R. Avery, G. Elliehausen and A. Kennickell, “Changes in “The Size Distribution of Household Dispos- the Use of Transaction Accounts and Cash from 1984 to 1986,” Fe deral Reserv e Bulletin, Vol. 73, No. 3, 1987, pp. 179-195. [13] E. Wolff, able Wealth in the United States,” Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 29, 1983, pp. 125-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.1983.tb00636.x [14] D. Kessler and E. Wolff, “A Comparative Analysis of Household Wealth Patterns in France and the United States,” Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 37, No. 3, 1991, pp. 249-266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.1991.tb00370.x [15] A. Kennickell and M. Starr-McCluer, “Household Saving and Portfolio Change: Evidence from the 1983-1989 SCF Panel,” Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 43, No. 4, 1997, pp. 381-399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.1997.tb00232.x

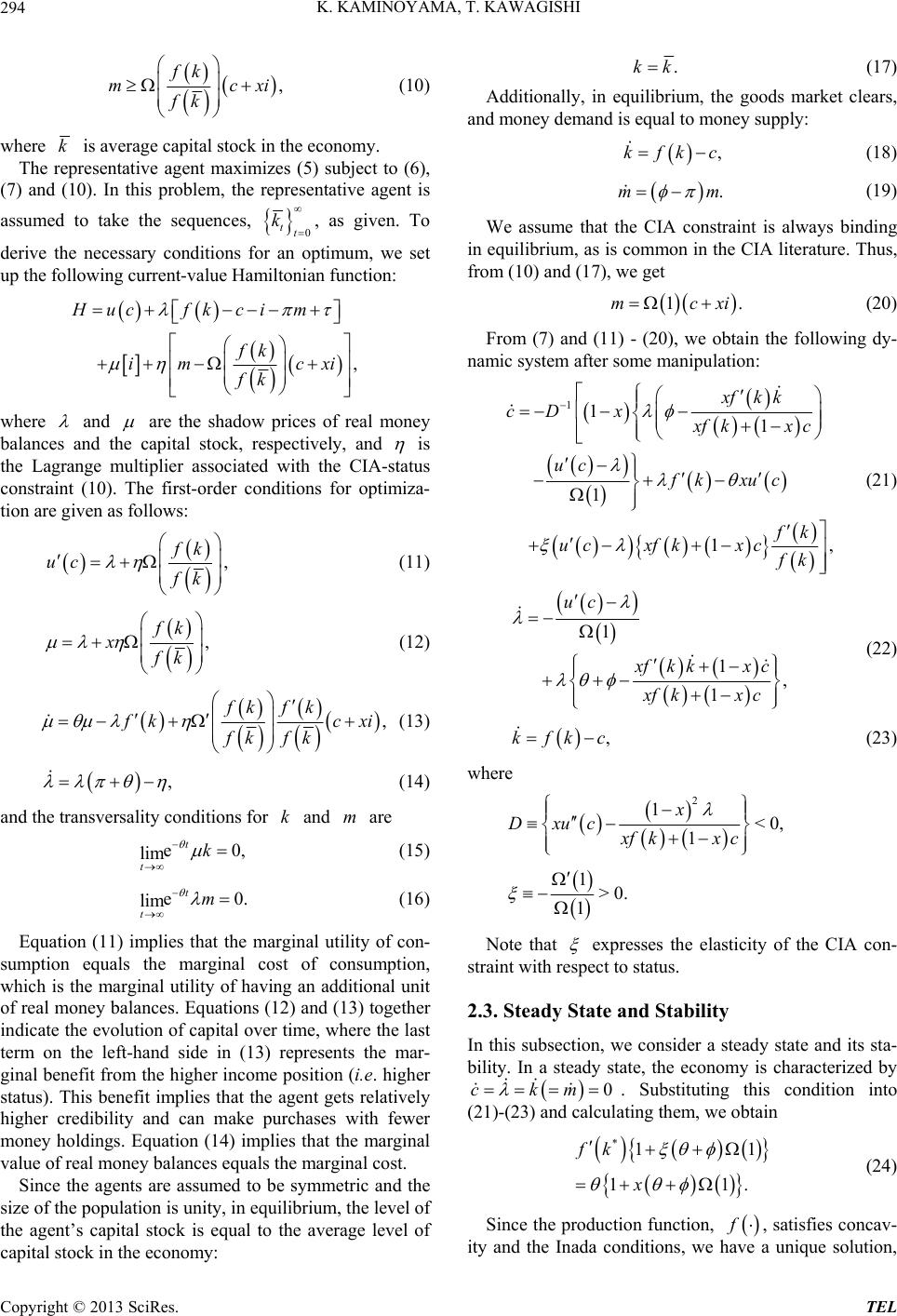

|