Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.10A, 82-89 Published Online October 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.410A012 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 82 Enhancing Student Engagement with Their Studies: A Digital Storytelling Approach Eunice Ivala1, Daniela Gachago1, Janet Condy2, Agnes Chigona2 1Fundani Centre for H i g he r Education Development, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, South Afr ica 2School of Education a nd Social Sciences, Ca pe Peninsula University of Technology, Cape To wn , South Africa Email: ivalae@cput.ac.za Received August 2nd, 2013; revised September 2nd, 2013; accepted September 9th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Eunice Ivala et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Higher education institutions in South Africa are faced with low throughput rates, and the need to enhance students’ interest in their studies is a key objective for higher education institutions. Student engagement is one of the factors shown empirically to enhance student success at higher education institutions. The paper reports on the potential of digital storytelling in enhancing student engagement with their studies, amongst 29 final year pre-service student teachers at a large University of Technology in South Africa, as part of their assessment in their final year professional course. The reason for doing this research was due to the limited adoption of digital storytelling in conventional educational settings globally and the fact that little research has been done internationally and particularly in South Africa, into how digital storytelling can be a vehicle for expanding learning. The study was framed around the engagement construct involv- ing qualitative methods of collecting data. Focus group interviews were conducted with the students and the facilitators of the project to elicit whether the production of digital stories led to student engagement. Focus group interviews were analyzed using inductive strategy. Results showed that the production of digital stories enhanced student engagement with their studies which led to high levels of reflection on the subject matter, which as a result led to a deep understanding of the subject matter. Findings of this study will contribute knowledge in the field which may be valuable in increasing student engagement with their studies. Keywords: Student Engagement; Engagement Construct; Digital Storytelling; Digital Stories; Digital Literacy Skills Introduction Higher education institutions (HEIs) in South Africa are faced with low throughput rates (Swanepoel et al., 2009; Scott et al., 2007), and the need to enhance students’ engagement in their studies is a key objective. Student engagement (the amount of physical and psychological energy that students de- vote to educationally purposeful activities) is one of the factors shown empirically to enhance student success at HEIs (Astin, 1977, 1985; Gellin, 2003; Pike, Kuh, & Gonyea, 2003; Pike, Schroeder, & Berry, 1997). In response to the above challenge, this study investigated the potential of digital storytelling in en- hancing student levels of engagement with their studies, amongst 29 final year pre-service student teachers at a large University of Technology in South Africa, as part of their as- sessment in their final year professional course. The study was formed by the engagement construct (Kuh, 2009) which helped the researchers in understanding the potential of digital story- telling in enhancing student engagement with their studies. The engagements construct holds that the level of student engage- ment is positively related to gains in the desired outcomes, their general abilities or critical thinking; is also positively linked to grades and retention rates. The above tenets guided the re- searchers in this study. The study utilized qualitative methods of collecting data. Focus group interviews were conducted with the students and their facilitators (inclusive of the lecturer) to elicit whether the production of digital stories led to student engagement with the subject matter. Findings of the study showed that the produc- tion of digital stories enhanced students’ level of engagement with their studies, which led to high levels of reflection on the subject matter, which as a result, led to a deep understanding of the subject matter. The researchers recommend that digital storytelling should be used more in pre-service teacher pro- grammes because they expand learning beyond the traditional face-face methods of teaching and learning and lead to high levels of student engagement with their studies. Additionally, the researchers suggest that there is need to implement digital storytelling in disciplines other than education to ascertain whether the results are replicable or not. Literature Review: Digital Storytelling and Student Engagement Digital stories are defined differently by different authors (Banaszewski, 2005; Barrett, 2006; Mills, 2010; Long, 2011).  E. IVALA ET AL. However, the working definition for this study is that, digital stories are short, first person video-narratives created by com- bining recorded voice, still and moving images and music or other sound. Digital stories are produced by someone who is not a media professional, and usually constructed as a thought piece on a personal experience (Matthews-DeNatale, 2008). These non-professionals position themselves as “authors”, com- posers, and designers who are expert and powerful communi- cators, with things to say that the world should hear (Hull et al., 2006: p. 10). Digital stories have a variety of uses: telling of personal tales, recounting of historical events, or as a mean to inform or instruct on a particular topic etc. Digital storytelling shifts the focus of the classroom away from the teacher, a model that has dominated education since the 18th Century, to the student (Banaszewski, 2005; Knapper, 2001). The basic paradigm shift is from an educational emphasis on people as recipients of information and knowledge to an emphasis on people as participants in the creation of information and knowl- edge (Freire, 2001; Ohler, 2006; Tyner, 1998). The creation of the digital stories involves incorporating multimedia compo- nents such as images, music, video, and narration, which is usually the author’s own voice (Barrett, 2006, 2008; Dogan & Robin, 2006) and to deliberately make explicit their own thoughts and actions whereby fostering reflection. If well integrated in schools/universities, digital storytelling can enhance facilitation of a wide range of substantial educa- tional benefits: acquisition and consolidation of knowledge and skills; heightened engagement, motivation towards learning activities, and also acquisition of digital literacy skills (Blas, Garzotto, Paolini, & Sabiescu, 2009). Digital storytelling allows students to develop their personal and academic voice, present knowledge to a community of learners and receive situated feedback from their peers. Due to their affective involvement with this process and the novelty effect of the medium, students are more engaged than in traditional assignments. These factors can create a “spiral” of engagement, drawing students into deeper and deeper engagement with their topics or studies (Co- ventry & Oppermann, 2009). Digital storytelling’s combina- tion of video, sound, images and student voice creates an envi- ronment where students become deeply invested in their topics or subjects under study. Digital storytelling increases engage- ment through interactivity. It improves students’ teamwork capabilities through the thick social interaction students engage in during the production, than other school activities do (Blas, Garzotto, Paolini, & Sabiescu, 2009). Digital stories mediate the academic conversations students conduct with their peers and with staff, management of their learning, how they document, distribute and apply their knowledge, or the time they spend really trying to understand a topic. Furthermore, creating digital stories increases students’ motivation and engagement levels (Dogan & Robin, 2008; Salpeter, 2005), especially the direc- tor’s chair effect, self expression and opportunity to utilize technology as a key factors in captivating and motivating stu- dents (Banaszewski, 2005; Paul, 2002; Dogan & Robin, 2008). Despite growing recognition of the importance of student engagement and the potential impact of digital stories on stu- dent engagement, little research has been done internationally and in South Africa into how the adoption of digital storytelling as a vehicle for expanding learning is creating new patterns of engagement. Additionally, the adoption of digital storytelling in conventional educational setting is currently limited; most re- ported educational projects based on these systems are largely based on episodic, short-term experiences involving a limited number of teachers and students for a short period (Blas, Gar- zotto, Paolini, & Sabiescu, 2009) and the little research avail- able is from developing countries. As a result, only limited research is available to guide best practice. Thus, the reason why the researchers in this study set to investigate the potential of digital storytelling in enhancing student levels of engage- ment with their studies in an African context, specifically amongst 29 final year pre-service student teachers at a large University of Technology in South Africa. The study aims to- further research in this field, and is guided by the following question: what is the potential of digital storytelling in enhanc- ing pre-service teacher students’ levels of engagement with their studies? Theoretical Framework The study was informed by the engagement construct which has been in the literature for more than seventy years, with the meaning of the construct evolving over time (Kuh, 2009). The earliest use of the engagement construct was by Ralph Tyler, who showed the positive effects of time on task on learning (Merwin, 1969). In the 1970s, Pace developed the College Stu- dent Experiences Questionnaire (CSEQ), which was based on what he termed “quality of efforts”. He showed that students gained more from their studies and other aspects of the college experience when they invest more time and energy in educa- tionally purposeful tasks such as: studying; interacting with their peers and teachers about substantive matters; applying what they are learning to concrete situations and tasks etc. (Pace, 1990). Alexander Astin (1984) fleshed out and popular- ized the quality of effort concept with his “theory of involve- ment” in which he emphasized importance of involvement to student achievement. Since then, different scholars have con- tributed lots of papers addressing different dimensions of stu- dent effort and time on task and their relationship to various desired outcomes of college (Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005; Pike, 2006; Tinto, 1987, 1993). Today, engagement is the term usually used to represent constructs such as quality of effort and involvement in produc- tive learning activities (Kuh, 2009) and student engagement is measured differently by different scholars. Engagement is con- ceptualized as the time and effort students invest in educational activities that are empirically linked to desired college out- comes (Kuh et al., 2008). Engagement encompasses various factors, namely: investment in the academic experience of col- lege; interactions with faculty; involvement in co-curricular activities, and interaction with peers (Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005; Kuh, 2009). Kuh (2009) emphasizes two major facets: in-class (or academic) engagement and out-of-class engagement in educationally relevant (co-curricular) activities, both of which are important for student success. Thus, the factors that influence student’s level of engagement are either student-based or institution-linked (Strydom et al., 2010). Student behaviours which are linked to engagement include study habits, time on task1, interaction with staff, peer involvement, and motivation (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). Ac- cording to the Student-engagement construct (Astin, 1984, 1Time on task has two meanings: one is to do with how long the students have been in college; the other is to do with how many hours a week the students usually spend on activities related to their school work (Pace, 1982: p. 22; Spanjers et al., 2008). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 83  E. IVALA ET AL. 1985), institutional policies and practices influence levels of student engagement on campus. Certain institutional practices are known to lead to high levels of student engagement (Chick- erring & Reisser, 1993; Pascarella & Terenzini 1991). These include student-faculty contact, cooperation among students, active learning, prompt feedback, time on task, high expecta- tions, and respect for diverse talents and ways of learning. Also important to students’ learning are institutional environments that are perceived by students as inclusive and affirming and where expectations for performance are clearly communicated (Kuh, 2001). Institutions influence student engagement by the way in which they “allocate resources and organise learning opportunities and services to induce students to participate in and benefit from such activities” (Kuh et al., 2005: p. 9). Thus, measures of student engagement that guided the researchers in understanding the issue under investigation in this study were: interaction with staff; interaction with peers; time on task (in-class and out-of-class engagement in educationally rele- vant activities (Kuh, 2009); policies and practices; applying what they are learning to concrete situations and tasks (Pace, 1990); motivation; active learning; prompt feedback; respect for diverse talents and ways of learning (Chickering & Reiser, 1993; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991). Background of the Case Study The project2 was carried out in 2010, with final year pre- service students in the Faculty of Education and Social Sci- ences at a large University of Technology in South Africa. The lecturer considered using of digital storytelling in the profes- sional development course in order to help students acquire reflective skills. The course was structured into two block ses- sions, a face-to-face and teaching practice sessions. Students produced their digital stories during the face-to-face sessions whereby they were provided an environment where facilitators actively encouraged them to speak their minds, were interested to hear what the students had to say, responded respectively to students’ ideas and treated them as knowledgeable members of the class. It is in this kind of environment that 60 pre-service student teachers were introduced to the art of digital storytelling. Before embarking on their own stories, students were shown a model story developed by their lecturer as they were not famil- iar with the digital story genre. The seed story shown was on the lecturer’s reflection on her thirty years of being a teacher. After the introduction to the art of digital storytelling, 31 stu- dents opted to write a paper-based portfolio for their assessment, leaving 29 students to embark on the journey of digital storytel- ling for their final year assessment in the professional course. In this assessment, all the 60 students were required to reflect- on-action3 on the seven roles of a teacher4. The project took eight weeks, commencing with students writing a script for their stories. After each student wrote drafts of the story, the facilitators provided constructive feedback, on each draft, giving suggestions on how to shape the stories to not exceed the required word count of 500 words. It is important to note that the first drafts of the students story scripts were too long (in some cases more than 5 pages) and content followed the examples shown by their lecturer and therefore had no con- nection with the seven roles of the teacher as per the assign- ment brief. This resulted in students writing several drafts. Students worked in groups (self-selected) mostly based on lan- guage and race and within and across these groups, students gave feedback on each other’s script. After writing the script, students turned their written script into digital audio files by recording their voices as they read their stories using a software programme called Audacity5. They then located, scanned or took digital photographs to accompany their words, found im- ages on the Internet to enrich their stories, recorded background songs or downloaded songs from the Internet. They ended the process by bringing these multiple media together (using MS Movie Maker)6 to make a short (around 5 minutes long) pow- erful and personally meaningful digital stories that clearly and movingly spoke to the other members of the class. The produc- tion of the story took place both off and on-campus in a dedi- cated student laboratory. The final story was presented to staff of the Faculty of Education and Social Sciences, students’ par- ents and the students themselves. See Figure 1 below for a schematic representation of the digital storytelling process. Methodology The study utilized qualitative methods of collecting data. Participants and Context The study was conducted in 2010, with 29 final year pre- service students in the Faculty of Education and Social Sci- ences. The study was located in this faculty and subject, be- cause of the lecturer’s and students’ willingness to participate in the study. Three staff members from the academic develop- ment centre at this university facilitated the project. Conven- ience sampling was therefore used for this study. 2This study is a continuation of the study by Ivala et al. (2011) on digital storytelling and enhancement of reflection amongst 29 pre-service student teachers and their lecturers at CPUT. 3Reflection-on-action involves students reflecting and contemplating on issues after the issue had taken place (Schön, 1983). 4Currently the South African national teacher curriculum is based around the seven roles of the teacher, which include: mediator of learning; inter- preter and designer of learning programmes and materials; leader, adminis- trator or and manger; community, citizenship and pastoral role; scholar, researcher and lifelong learner; assessor; and learning area/subject/dis- cipline/phase specialist (South African Government Gazette No. 20844). Figure 1. Digital storytelling p rocess. 5For details on what audacity is see http://wikieducator.org/Using_Audacity/What_is_Audacity 6For details on what Wi n dow Movie Maker is see htt ://en.wiki edia.or /wiki/Windows Movie Make . Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 84  E. IVALA ET AL. Data Collection and Analysis Data was gathered from three focus group interviews with the students and one focus group interview with the facilitators (inclusive of the lecturer) of the project to elicit whether the production of digital stories led to student engagement. Focus group interview data was recorded on tape and transcribed ver- batim. The interviews were analyzed focusing on the identifica- tion of conceptual themes and issues emerging from the data, using techniques such as clustering, and making contrast and comparisons (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The researchers were especially interested in moments in the project that could be construed as the focal points for students’ engagement with their studies. Trustworthiness The trustworthiness of information gathered in this study was ensured by members of the research team discussing the re- search process, the congruency of the emerging findings with the raw data, and tentative interpretations which promoted va- lidity. Descriptive validity (Maxwell, 1992) was ensured by tape recording participants’ focus group discussions and tran- scribing the discussions verbatim with an aim of quoting as accurately as possible what the participants’ had said. Interpre- tive validity was also adhered to as the researchers in this study sought to understand the phenomena from the participants’ perspectives and categories (Bohman, 1991). The researchers also employed the engagement construct to understand the issue under investigation, thus promoting theoretical validity. The researchers in this study acknowledge that findings of this study are not generalisable, but offer valuable insights, which others interested in the implementation of digital storytelling in their curriculum delivery, could draw from. Statement of Ethics During the course of the study, all participants were treated with respect and sensitivity. Activities carried out during the study were negotiated with the participants and informed con- sent was sought from every participant participating in the study. Participants were also assured anonymity. Furthermore, ethical clearance was obtained from Research Ethics Commit- tee of the institution. Limitations of the Study The purpose of this study was neither to measure students’ attitudes to digital storytelling, nor to focus on the impact of digital storytelling on student performance. The study focused on the potential of digital storytelling in enhancing student engagement with their studies, as perceived by the students and the facilitators of the digital storytelling project. This means that no statistics on student attitudes and performance will be presented in this paper. Further research will need to be carried out to establish students’ attitudes on digital storytelling and the impact of digital storytelling on students’ performance. Results and Discussion The paper reports on the potential of digital storytelling in enhancing student engagement with their studies from a stu- dents’ and facilitators’ perspective. Based on the analysis of the data, both the facilitators’ and the students’ who participated in this project reported that digital storytelling enhanced students’ engagement with the subject matter at hand. Participants indi- cated that the following factors enhanced their engagement with their studies: extended opportunities for study beyond the classroom time; motivation to interact with the subject content; student control of their own learning; the process of producing digital stories; peer learning and increased student-lecturer interactions and promotion of high levels of reflection. Results on digital storytelling and enhancement of student engagement will be discussed under the aforementioned factors. Extended Opportunities for Study beyond the Classroom Time One of the factors given for enhancing students’ levels of engagement with their studies by both the facilitators and the students who participated in the digital storytelling project was the extended opportunities for study beyond the classroom time. Carroll and Carney’s (2005) argued that giving students’ a chance to communicate their personal stories prompts them to invest much more time and effort in the project than it may be required (see also Coventry & Oppermann, 2009). Findings of this study showed that students engaged deeply with the pro- duction of their stories and hence the subject matter both at home and on campus, as indicated in the following staff and student quotes: Staff A: … there is this student, I helped her with her story throughout…I helped her edit her story, I helped her record her story, I helped her put it together, the music. I knew what was in her story but when it came to the pre- senting, I was shocked because I had no idea of the words that were coming out of that machine. Meaning that she worked on it in class but when she found the skills that she needed she went and re-did it… so it means that when she got home she went back to it and started it again… Student C: I also did most of my work at home, like writing out the story and asking when I came to campus, asking the lecturers maybe to edit and just to check if my story is according to how it’s supposed to be… and would do the typing on campus. The above results demonstrate that literacy demands and practices of college life infiltrated home life and that students spend considerably more time (than when doing usual paper based portfolios or assignments) on campus, outside of class time and off-campus to work on their stories. These results are in line with the engagement construct factor of in-class and out- of-class engagement in educationally relevant activities (Kuh, 2009). Motivati o n to Interact w i t h th e S u bject Conte nt The motivation to interact with the subject content was an- other factor given for enhancing student levels of engagement with their studies. In this regard, finding servealed that the digi- tal storytelling project motivated students to interact with the content on the seven roles of the teacher: Student B: ... it [producing a digital story] was so much exciting than rather doing…all the paper based assign- ments that we always have to do…you know it actually Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 85  E. IVALA ET AL. was something that we wanted to come, we wanted to do it and we loved every minute of it. It’s not often that you get an assignment that y ou actuall y really enjoy doing. Based on the above results, the lecturer’s choice of using digital stories for assessment motivated these students’ in han- dling the task in question more than any of the previously used paper based ways of assessment (Ames, 1992; Blas, Garzotto, Paolini, & Sabiescu, 2009). These findings are in line with the engagement construct point of view that certain institutional practices are known to lead to high levels of student engage- ment (Astin, 1985; Chickering & Reisser, 1993; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991). As a result of this practice [digital storytel- ling], the students were deeply involved in their learning. Student Control of Their Own Learning Another factor which enhanced students’ levels of engage- ment in their studies was the student control of their own learn- ing. Students reported that the production of digital stories gave them control of their learning and enabled them to tell their stories in their own voice: Student D: … its [producing of digital stories] is very personalized. It comes from your perspective and then other people can relate to that…whereas when you write something [paper based assignment] it comes out very factual especially at this university level… people read something that you’ve written and they have a slightly different interpretation as you do in your head. Whereas this [digital story] you’ve got the images right there and you’ve got the words and the music. The tone is set. The mood is set and the pictures are there to show things from how you experience it and how you see it. So I think it’s much more affective actually. These results show that through the production of digital sto- ries, students actively engaged (had internal interactions with themselves) in making sense of their experiences (Chickering & Reisser, 1993; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991) and reflected more deeply about the design process (McKillop, 2005) and the sub- ject matter. This internal interaction is important since it is the process of intellectually interacting with content that results in changes in the learner’s understanding, perspective, or the cog- nitive structure of the learners mind (Moore, 1989) and initiates learners’ internal interaction about the information and ideas they encounter in a course and constructs it into knowledge with personal application and value (Dewey, 1916). The Process o f Producing Digital Stories An additional factor given by the facilitators and students for enhancing their levels of engagement with their studies was the process of producing digital stories. Results revealed that the whole process of producing digital stories enhanced students’ engagement with the subject matter. Staff B: … I must say most of them took it really seri- ously to a point that they wanted it to be as we said…, they re-did it and re-did it and re-did it and some of them just recorded again in class, two, three, four times on their own and they also went back… and recorded a back- ground song again… Student A: … I have to look at how long we had to take just to write that thing [the story script] out. You write it out, that’s the first draft. Then you’re going to write it out again. That’s your second draft. Third draft, fourth draft. You know it takes long, just thinking because you need to okay that sentence doesn’t fit there… That takes time and I mean even the pictures… it took me eight hours getting pictures from Flicker… The results show that all stages of the digital storytelling production process (writing the story, directing their own digi- tal story, illustrating and collecting images, selecting images, combining images, music and voice and sequencing them to make the story) appeared to stimulate students’ emotional con- nection, effort and interest in the subject matter and hence stu- dent engagement. Thus the above experiences may have re- sulted in a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Peer Learning and Increased Student-Lecturer Interactions Furthermore students indicated that their levels of engage- ment with their studies were enhanced by peer learning and increased student-lecturer interactions. Results showed that through the production of digital stories, students benefited immensely from the influence and expertise of peers, as evi- denced in the following quotes: Student E: … Because like [student] C knew exactly what was going on with all the programming whereas with writing and stuff, I would be fine on my own. Just like [student] A, but without C my movie would have been very different and without sort of D saying this sounds good, that sounds bad, or you know we kind of, we bounced ideas off each other. Student C: … working with other students, I mean, there might have been students that you never even spoke to. I mean for four years we’ve been together and to be honest you’ve never said a word t o that person but durin g this, do- ing this [production of digital stories] we just opened up. The above findings revealed that students learned enor- mously from each other by advising and giving feedback to each other. According to Bruce and Lin (2009), this kind of students’ dialogues constitute an intellectual layer of meaning making, one that inspires the students to think seriously about effective communication and the quality of their stories (Blas, Garzotto, Paolini, & Sabiescu, 2009). Furthermore, the results also indicate that the project helped students to create a learning community which did not exist before. Wenger, McDermott and Snyder (2002) argue that peer interactions is critical to the development of communities of learning that allow students to develop interpersonal skills, and to investigate tacit knowledge shared by community members as well as a formal curriculum of studies. Students also benefited from the high levels of in- teraction with the facilitators. Facilitators of the project, who were themselves lecturers at the university assisted students by giving continuous feedback when needed, on all the steps needed for the production of the digital stories. Staff C: One, interpersonal relationships with the students. That was really interesting because initially we showed them a video and they tried to copy what they saw. And in the first instances you had to basically get them away Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 86  E. IVALA ET AL. from what they saw and get them to be busy with the five or the seven roles of the teacher and that took a bit of confrontation… the moment they realized what they had to do, then they allowed me in and there was an incredible mix, … a linkage between me and the students after a while which was lekker [means good] to play around with… Student B: I also did most of my work at home like writ- ing the story and… asking the lecturers maybe to edit and just check if my story is according to how it’s supposed to be… according to the criteria. The above results suggest that digital storytelling supported a learning environment rich with student-student, student-lecture and student-content interactions. Anderson (2003) argued that sufficient levels of deep and meaningful learning can be devel- oped, as long as one of the above types of interactions is at very high levels. Additionally, the results are in line with the stu- dents’ and institutional factors that influence student levels of engagement. These fac tors are time on task, t ime spend in class and out-of-class on educationally purposeful activities, interac- tion with lecturers, and interaction with peers and motivation (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005; Kuh, 2009). Promotion of Hi g h Levels of Reflection The promotion of high levels of reflection is another factor given by both the facilitators and the students for enhancing their levels of engagement with their studies. Both staff and students unanimously felt that digital storytelling promoted high levels of reflection which led to deep learning or under- standing of the subject matter, as evidenced in the following quotes: Staff: This particular experience was a brilliant way of doing it because they [the students] really had to engage with their studies, the last four years. What they have done, what they accomplished, how they learnt to be a better teacher, so it really got them to engage… they said they can see now what they’ve learnt and if they left uni- versity without doing it [digital storytelling] it would be leaving in a vacuum… this experience helped them to crystallize all their learning… Student: … it made me understand more what they meant [seven roles of the teacher], because I’ve always known what the seven roles of the teacher are, but I didn’t actu- ally know what they meant and what they meant to me, but now doing it with the digital story and actually incur- porating it to my story, I kind of understood what they’re about and what those seven roles-basically I didn’t under- stand what they were but after the story now I know what they mean and what they are. The deeper reflection promoted by digital storytelling is said to have promoted a deeper understanding in a subject content which had previously been taught using the lecture method and understood superficially by the students. Conclusion and Recommendations In general, findings of this study showed that digital storytel- ling provided expanded opportunity for the students to engage and plug deeper into the subject matter. Factors which led to high levels of student engagement were: extended opportunities for study beyond the classroom time; motivation to interact with the subject content; student control of their own learning; the process of producing digital stories; peer learning, increased student-lecturer interactions and promotion of high levels of reflection. The researchers echo Herrington’s (2003) finding that student engagement is paramount to learning success as the provision of expanded opportunity to interact with the subject matter in the course understudy, led to high student levels of engagement with the subject matter which enhanced student motivation and interest in the subject matter and hence deep and meaningful understanding of the subject content. Based on the findings of this study, the researchers argue for recognition of and support for digital storytelling as an alterna- tive method of assessment in teacher education, which extends teaching and learning beyond the classroom and hence high levels of student engagement with their studies. The researchers are of the opinion that for appropriate integration, digital story- telling should be embedded in the curriculum and not used as an add-on or a fad way of assessing learning. While the study demonstrates the potential of digital storytelling for students engagement in teacher education, a major question of sustain- ability and replication to other disciplines remains. The re- searchers suggest that there is need to implement digital story- telling in other disciplines other than education in order to es- tablish whether the results are replicable or not. The researchers also suggest that there is need for more re- searches to ascertain if higher levels of engagement would be experienced by students through using digital storytelling to engage with subject content which has not been previously taught using a different delivery method. Since Dewey (1913) pointed out the relationship between effort and interest and how this interacts in producing good result, the researchers suggest that further research is needed to gauge whether the increased levels of student engagement promoted by digital storytelling translate to improved student performance (in terms of marks). Acknowledgements An earlier version of the paper appears in the proceedings of the 7 International Conference on e-Learning: Ivala, E., Chi- gona, A., Gachago, D. & Condy, J. (2012). Digital Storytelling and Student Engagement: A Case of Pre-service Student Teachers and their Lecturers at a University of Technology. This paper has been substantially revised based on the discus- sions at the conference as well as the valuable comments from the editor of special issue of Electronic Journal of e-Learning who had selected the paper for possible publication in the spe- cial issue. REFERENCES Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures and student motivation. Journal of Educational P sychology, 84, 261-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.261 Anderson, T. (2003). Getting the mix right again: An updated and theo- retical rationale for interaction. The International Review of Research in Open and distance lear n i ng , 4. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/149 Astin, A. W. (1977). Four critical years. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 25, 297- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 87  E. IVALA ET AL. 308. Astin, A. W. (1985). Involvement: The cornerstone of excellence. Change, 17, 35-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00091383.1985.9940532 Banaszewski, T. M. (2005). Digital storytelling: Supporting digital literacy in grades 4-12. Masters of Science thesis, USA: Georgia In- stitute of Technology. Barrett, H. (2006). Digital stories in eportfolios: Multiple purposes and tools. http://electronicportfolios.org/digistory/purposes.html Barrett, H. (2008). Multiple purposes of digital stories and podcasts in eportfolios. http://electronicportfolios.com/portfolios/SITE2008DSpaper.pdf Blas, N. D., Garzotte, F., Paolini, P., & Sabiescu, A. (2009). Digital storytelling as a whole-Classlearning activity: Lessons from a three- year project. Proceedings of the 2nd Joint International Conference on Interactive Digita l Storytelling. H eidelberg,: Spring e r -Verlang. Bohman, J. (1991). New philosophy of social science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Bruce, B., & Lin, C (2009). Voices of youth: Podcasting as a means of inquiry-based community engagement. E-Learning and Digital Me- dia, 6, 230-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/elea.2009.6.2.230 Carroll, D., & Carney, J. (2005). Personal perspectives: Using multi- media to express cultural identity: Contemporarily issues in Tech- nology and Teacher Education. http://www.citejournal.org/vol4/iss4/currentpractice/article2.cfm Chickering, A. W., & L. Reisser, L. (1993). Education and identity (2nd ed.). San Francis co: J ossey-Bass. Chickering, A. W., &Garmson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. American Association for Higher Education Bulletin, 39, 3-6. Coventry, M., & Oppermann, M. (2009). From narrative to database: Multimedia inquiry in across-classroom scholarship of teaching and learning. http://www.academiccommons.org/commons/essay/narrative-database Dewey, J. (1913). Interest and effort in education. New York: Hough- ton Mifflin. Dogan, B., & Robin, B. (2006). Implementation of digital storytelling in the classroom by teachers trained in a digital storytelling work- shop. http://digitalstorytelling.coe.uh.edu/pdfs/Dogan-DS-Research-2008.p df Dogan, B., & Robin, B. (2008). Implementing of digital storytelling in the classroom by teachers trained in a digital storytelling workshop. In Proceedings of society for Information Technology and Teacher Education Internation a l C o nf e re n c e. Chesapeake, VA: AACE. http://www.edtlib.org/f/27287 Eccles, J. S., &Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Revi e w o f Psychology, 53, 109-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153 Freire, P. (2001). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy and civic courage. London: Rowmanand Littlefield Publishers. Gellin, A. (2003). The effect of undergraduate student involvement on critical thinking: A meta-analysis of the literature, 1991-2000. Jour- nal of College Student Development, 44, 746- 762. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/csd.2003.0066 Herrington, J., Oliver, R., & Reeves, C. (2003). Patterns of engagement in authentic online learning environments. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 19, 51-55. Hull, G., Kenny, N. L., Marple, S., & Forman-Schneider, A. (2006). Many versions of masculine. After school matters. The Robert Browne Foundation. http:///www.uclinks.org/rreference/research/Hulletal.Masculinitypap er.pdf Ivala, E., Gachago, D., Condy, J., & Chigona, A. (2011). Digital story- telling and reflection in higher education: A case of pre-service stu- dent teachers and their lectures’ at a University of Technology. Paper submitted for consideration for publication to The Journal for Trans- disciplinary Research in Southern Afr i ca. Knapper, C. (2001). The challenge of educational technology. The In- ternational Journal for Academic Development, 6, 92-95. Kuh G. (2009). Improving undergraduate success through student en- gagement. Presentation to Council for Higher Education, Pretoria: SA. Kuh, G. D. (2001). Assessing what really matters to student learning: Inside the national survey of student engagement. Change, 33, 10-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00091380109601795 Kuh, G. D., & Others (2008). Unmasking the Effects of Student En- gagement on College Grades and Persistence. Journal of Higher Education, 79, 540-563. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jhe.0.0019 Kuh, G. D., Schuh, J. H., Whitt, E. J., & Associates (1991). Involving colleges: Encouraging student learning and personal development through out-of-class experiences. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Kuh, G. D., Whitt, E. J., & St range, C. C. (1989). The contributions of institutional agents to high quality out-of-class experiences for col- lege students. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco. Kuh, G. G., Kinze, J., Shuh, J. H, Whitt, E. J., & Associates (2005). Student success in college: Creating conditions that matter. San Franisco: Jossey-Bass. Long, B. (2011). Digital storytelling and meaning making: Critical re- flection, creativity and Technology in pre-service teacher education. http://lillehammer2011.files.wordpress.com/2010/10/bornie-long-con ference-paper.pdf Maehr, M. L., & Midgley, C. (1991). Enhancing student motivation: A school-wide approach. Educational Psychologist, 26, 399-427. Matthews-DeNatale, G. (2008). Digital storytelling—Tips and re- sources. http://www.educause.edu/Resources/DigitalStoryMakingUnderstandi n/162538 Maxwell, J. A. (1992). Understanding and validity in qualitative re- search. Harvard Education Review, 62, 279-299. McKillop, C. (2005). Storytelling grows up: Using storytelling as a reflective too in higher education. Paper Presented at the Scottish Educational Research Association Confe r ence, 24-25 November. Merwin, J. C. (1969). Historical review of changing concepts of eva- luation. In R. L. Tyler (Eds.), Educational evaluation: New roles, new methods: The sixty-eighth yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, Part II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Thousa n d Oa ks : S ag e . Mills, K. A. (2010). A review of the “digital turn” in the new literacy studies. Review of Edu c ational Research, 80, 246-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0034654310364401 Ohler, J. (2006). The world of digital storytelling. Learning the digital age. Educational Leaders, 63, 44-47. Pace, C. R. (1990). The undergraduates: A report of their activities and college experiences in the 1980s. Los Angeles: Center for the Study of Evaluation, UCLA Graduate School of Education. Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1991). How college affects stu- dents: Findings and insights from twenty years of research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects stu- dents: A third decad e of research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Paul, C. N. (2002). Self-perceptions and social connects: Empowerment through digital storytelling in adult education. Dissertation Abstracts International (UMI No. 3063630 ). Pike, G. R. (2006). The convergent and discriminant validity of NSSE scalelet scores. Journal of College Student Development, 47, 551- 564. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/csd.2006.0061 Pike, G. R., Kuh, G. D., & Gonyea, R. M. (2003). The relationship between institutional missions and students’ involvement and educa- tional outcomes. R es ea rc h i n Hi gh er Education, 44, 243 -263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022055829783 Pike, G. R., Schroeder, C. C., & Berry, R. R. (1997). Enhancing the educational impact of residence halls: The relationship between resi- dential learning communities and first-year college experiences and persistence. Journal of College Student Development, 38, 609-621. Salpeter, J. (2005). Telling tales with technology. Technology and Learning, 25, 18,2 0,22,24. Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. How professionals think Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 88  E. IVALA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 89 in action. London: Temple. Scott, I., Yeld, N., & Hendry, J. (2007). Higher education monitor No.6: A case for improving teaching and learning in South African Higher Education. The Council o n Hi g h e r Education, Pretoria. Strydom, J. F., Mentz, M., & Kuh, G. D. (2010). Enhancing success in higher education by measu ring student engagement in South Africa. http://sasse.ufs.ac.za/dl/userfiles/documents/SASSEinpresspaper_1.p df Swanepoel, E., De Beer, A., & Müller, A. (2009). Using satellite classes to optimize access to and participation in first year Business Management: A case at an open and distance learning university in South Africa. Pe r spectives i n Education, 27, 311-319. Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Pres s . Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Tyner, K. (1998). Literacy in a digital world: Teaching and learning in the age of information. New Jersey: LEA. Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating commu- nities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

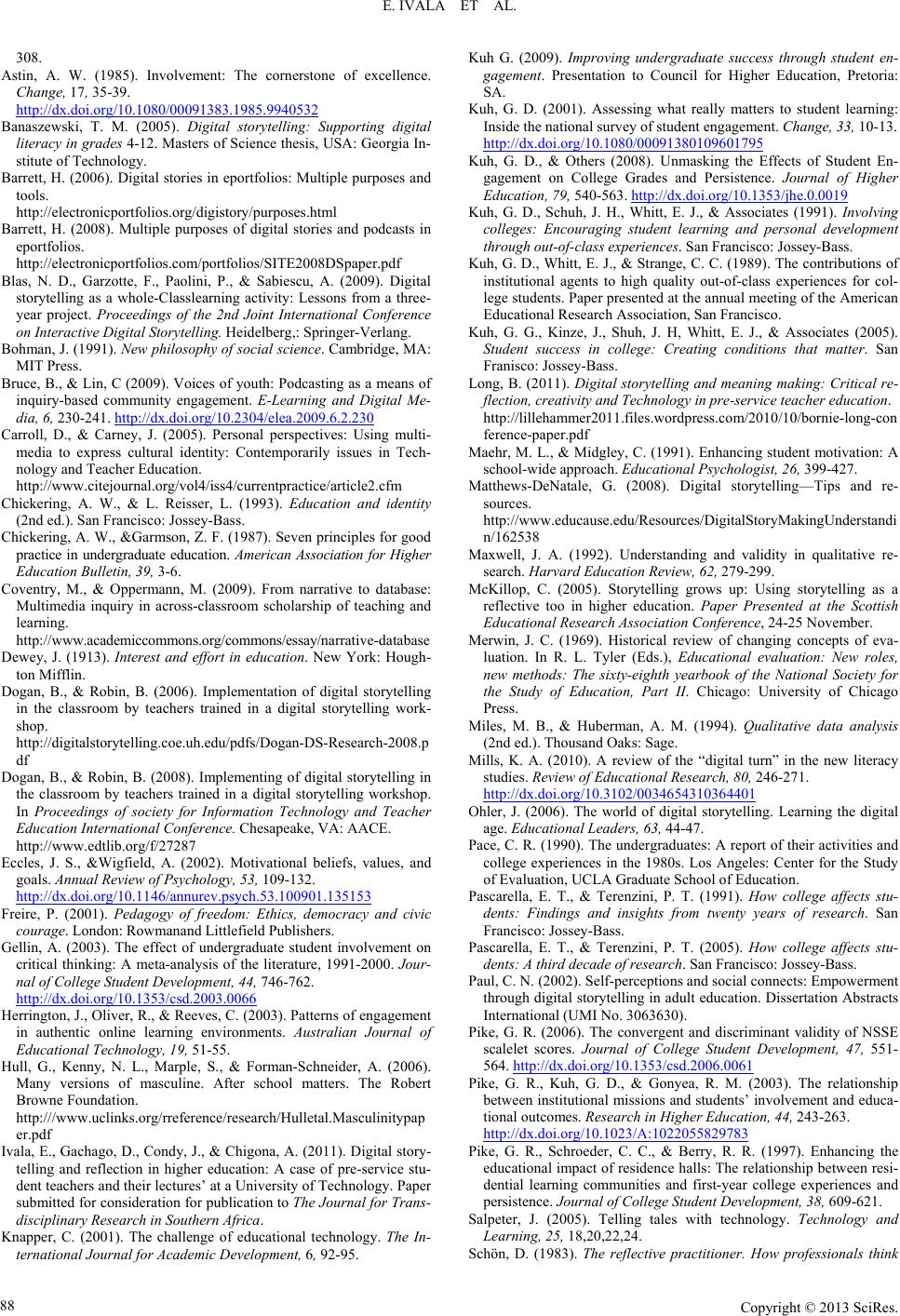

|