Open Journal of Leadership 2013. Vol.2, No.4, 87-94 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojl) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojl.2013.24014 Open Access 87 What Makes School Leaders Inspirational and How Does This Relate to Mentoring? Peter Hudson Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia Email: pb.hudson@qut.edu.au Received September 17th, 2013; revised October 15th, 2013; accepted October 21st, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Peter Hudson. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribu- tion License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Leadership comes in many forms (such as transactional, transformational, and distributed) and its effec- tiveness can inspire others to achieve organisational goals and visions. Inspiration as an emotional event requires receptiveness and an awareness of social interdependence. When mentees are inspired by mentor role models they can extend personal attributes and practices. Similar to other leaders, inspiring mentors can motivate mentees to develop a strength of character and achieve goals in the workplace. What makes school leaders inspirational and how does this relate to mentoring? This qualitative study collects data from 25 experienced teachers, which involved a written questionnaire, work samples, and audio-recorded focus group discussions. These participants indicated that inspirational school leaders were those who had: 1) organisational goals (e.g., visionary, goal driven, innovative, & motivational); 2) professional skills such as being knowledgeable, communicative, and acknowledging others’ achievements; and 3) personal attributes (e.g., integrity, active listening, respectful, enthusiastic, & approachable). This research shows how mentors and school leaders can consider the inspirational attributes and practices outlined by partici- pants in this study to inspire teaching staff. For example, an awareness of attentive listening, motivational and visionary practices, and acknowledging individual achievements can guide school leaders and men- tors to inspire others for achieving organsational goals and visions. Keywords: Leadership; Mentoring; Preservice Teachers; Mentor Leadership and Mentoring Leadership comes in many forms with past research identi- fying leadership in terms of traits, behaviours, and characteris- tics (Burns, 1978). However, identifying leadership continues to be elusive with many theories of education leadership (e.g., Bush, 2003); consequently considerable research has been un- dertaken during the last few decades, moving from trait leader- ship with characteristics of physical appearance, intelligence, skills and knowledge, and temperament (Yukl, 2006) to more flexible modes of leadership. Bass and Avolio (1997) drew from theories of leadership, including Burn’s (1978) notions about leadership, and categorised a full range leadership model with practices assigned to transactional, laissez-faire and trans- formational approaches. Avolio and Bass (2002) explain how strategies within these leadership practices can assist to deter- mine a person’s particular leadership practices and possibly predict the outcome of such leadership (see also Trottier, Van Wart, & Wang, 2008). To illustrate, transactional leadership focuses on providing rewards such as promotion and increased salary as a transaction for increased productivity. For a mentor teacher, this may entail rewards to the mentee such as favour- able practicum and internship reports in return for effective teaching that could lead towards securing a teaching position. Laissez-faire leadership may be considered as an absence or indifference in leadership, hence, it cannot be classified within effective leadership models. Yet, transformational leadership, with ethics and values at the centre of these practices, holds promise for inspiring others to advance workplace goals (Geijsel, Sleegers, Leithwood, & Jantzi, 2003). Transformational leadership focuses on motivat- ing people for quality and/or quantity increases in productivity (Boseman, 2008). It is within transformational leadership where organisational members are inspired to work collaboratively towards achieving organisational visions and missions (Gronn, 2002). Transformational leadership appears to have strong syn- ergies with mentoring arrangements, where a mentor teacher works in collaboration with the mentee to collectively advance teaching and learning goals in the classroom. As a subset of transformational leadership, distributed leadership can inspire others in roles to assist in achieving organisational goals (Harris, 2004), where workers share responsibility within an organisa- tion to advance workplace practices through an ethical and democratic investigative culture (Dean, 2007; Gronn, 2002; Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2001). Although Shoaf and Britt (2009) focus on behaviours instead of practices, they explain how a leader’s responsibility is to show how others can succeed with demonstrable links to suc- cessful work. In a behaviourist perspective, leaders “1) chal- lenge the process, 2), inspire a shared vision, 3) enable others to act, 4) model the way, and 5) encourage the heart” (Kouzes & Posner, 2007: p. 3), which can be aligned with mentoring proc- esses. Indeed, effective leadership appears inextricably linked to mentoring as “... mentoring is both an obligation and respon-  P. HUDSON sibility of leadership” (Kunich & Lester, 1999, p. 117). Indeed, they use the term mentoring as an acrostic (model, empathise, nurture, teacher, organise, respond, inspire, network, and goal-set) to provide an indication of practices that may also align with leadership. In the context of mentoring, Hudson and Hudson (2011) out- line distributed leadership where an extended community of mentors can take on informal leadership roles to guide mentees in their development of teaching practices. Distributed leader- ship transcends a single leader approach towards collaborative decision-making and may be noted as democratic leadership with an emphasis on empowering others within an organisation (Harris & Chapman, 2002), thus sharing responsibility and building capacity (Dean, 2007; Harris, 2004). In this respect, a successful mentor-mentee relationship would see the mentor distributing leadership to the mentee and building the mentee’s capacity towards eventual autonomy in a classroom, depending on circumstances (e.g., preservice teacher’s university year level). Collaboration and sharing of common goals has strong association with the distributed model of leadership (Kark- kainen, 2000) and strong associations within effective men- tor-mentee partnerships (e.g., see journal Mentoring & Tutor- ing). Successful mentoring relationships can be viewed progres- sively as a power exchange, which can operationally change the nature and dynamics of the relationship (Rippon & Martin, 2006). Effective leadership during mentoring would transform the mentee into an independent role, whereby the mentee be- gins to gain credibility and be recognised as a teacher with a teacher identity through an “emerging colleagueship” (Rippon & Martin, 2006: p. 92). Some researchers (Beutel & Spooner- Lane, 2009; Hudson, 2006) recognise that being an effective practitioner in the classroom does not presuppose mentoring ability or leadership skills. As Zachary (2009) reflects, some mentors may be willing and committed to participate but “don’t know what they don’t know” about mentoring (p. 43). An ex- perienced teacher may have expert knowledge and understand- ing on teaching practices, yet, mentoring requires learning new skills that both includes and extends beyond classroom teaching. A teacher in a mentoring role needs to deconstruct pedagogical practices and articulate understandings in ways that support another adult’s learning for becoming a teacher. Mentoring is not inherent but rather these skills must be learnt, thereby Hudson (2006) advocates that mentors can im- prove their methods of mentoring in much the same way as teachers aim to improve their methods of teaching (e.g., profes- sional development, sound planning and preparation, and re- flection on practice). To be effective in mentoring, mentors need to recognise their roles and, although models of mentoring are becoming more available (e.g., Hudson, 2010), there needs to be recognition of mentoring as a leadership role to inspire the mentee into teaching. Indeed, “mentors must have the vision to develop the leadership potential” (Kunich & Lester, 1999: p. 126). Offstein, Morwick, and Shah (2008) explain how men- toring is related to contingency leadership through roles such as modelling, counselling, coaching and sponsorship (e.g., a men- tor teacher sponsoring a preservice teacher on a class). Inspiration as an emotional event requires receptiveness and an awareness of social interdependence (Hart, 1998). When mentees are inspired by mentor role models they can develop resilience and extend personal attributes such as kindness, em- pathy and sensitivity (Moberg, 2008). Mentees can “develop moral character in the aftermath of profound inspiration” (Mo- berg, 2008: p. 99). Lockwood, Jordan, and Kunda (2002, cited in Moberg, 2008) claim that inspiring mentors can motivate mentees to develop a strength of character and achieve goals in the workplace. Mentoring can inspire leadership in others (John, 2008), with effective mentors conveying inspiration though their practices (Simmons, 2007). Determining relationships between inspirational school leadership and mentoring may assist both leaders and mentors to understand connections be- tween their roles, particularly what others perceive as being inspirational. The research question for this study was: What makes school leaders inspirational and how does this relate to mentoring? Demographics and Context for the Study Demographics for 25 participants (11 secondary teachers, 14 primary teachers) involved 7 males and 18 females. Four par- ticipants were between the ages of 22 - 29 years, 14 were be- tween 30 - 49 years and the rest older than 50 years of age. Three had not mentored a preservice teacher previously, 13 mentored between 1 to 4 mentees, 4 mentored between 5 - 9 mentees and 5 mentored 10 or more mentees. Although 4 par- ticipants had only taught between 1 - 4 years, the rest had taught for more than 5 years, including 13 who had taught for more than 10 years. Only seven participants had received pre- vious mentoring professional development, which included being on a mentoring committee, a one day conference (8 years ago), Specialist Teacher Assistant Course Mentoring course in the UK, and a two-day Mentoring for Effective Teaching (MET) professional development. Five participants claimed they were in leadership positions within their secondary schools (i.e., deputy principal, head of department, director of learning, head of curriculum, coordinator of Indigenous education). Two par- ticipants “strongly disagreed” they would want to be in a lead- ership position, five were “uncertain” and the rest either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” they wanted to become a leader in an educational role. These mentor teachers were involved in a professional development MET program. Method This qualitative study was conducted within a constructivist epistemology and used a grounded-theory approach as data formed “initial categories of information about the phenomenon being studied by segmenting information” (Creswell, 2012: p. 424). Data were collected from 25 experienced teachers at the commencement of a professional development program titled Mentoring for Effective Teaching (MET, see www.tedd.net.au). Data involved an extended written response questionnaire, au- dio-recorded focus group discussions, and work samples. The questionnaire was administered at the school site during the professional development program about mentoring and lead- ership, questions included: 1) Do you believe you have leader- ship potential? Why? 2) Think of an inspirational school leader: What were the leader’s practices that inspired you? Participants were asked to elaborate on their responses through a focus group. Furthermore, they extended their responses with work samples that focused on the qualities of inspiration leaders. “Inspirational leaders” was a category for axial coding to occur, that is, other categories were identified that related to this cen- tral category. As a result of inductive, comparative method, a model was generated around this central category (Charmaz, Open Access 88  P. HUDSON 2011). Analysis occurred by collating data into themes as they emerged (Charmaz, 2011). For instance, participants’ written responses, focus group recordings and written work samples (i.e., words used to describe inspirational school leaders) during the professional development were collated into themes with frequencies of each theme tabulated across the range of re- sponses. For example, “knowledge”, “knowledgeable”, and “knows” were collated under the word “knowledgeable” and provided with a numerical figure indicating the number of re- sponses. The Microsoft Word thesaurus was used to connect synonyms with one word (e.g., approachable: open-minded, accessible, social, and easy to talk to) and words that did not align with the Microsoft Word thesaurus but had strong con- nections were also collated (e.g., practical: down-to-earth). The focus group discussions produced six audio-recorded narratives about inspirational school leaders, which were transcribed for the purposes of providing more elaborate examples to the ques- tionnaire and work samples. As these participants were allo- cated randomly into groups, they were not identified by number in the same way as their questionnaire responses. Results and Discussion Mentors involved in the MET program were asked about their leadership potential with 6 outlining existing leadership roles and 17 claiming they wanted to be in leadership roles. The participants wrote about personal attributes (e.g., supporting, listening, and enthusiasm) and interrelationships within the school community, professional sharing with colleagues, past leadership experiences, and a professional sharing with col- leagues. To illustrate, positive personal attributes and school community relationships as indicators of leadership potential was noted by nine participants (4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 14, 18, 21, & 22) with opening remarks such as “I am able to listen and under- stand people’s concerns” (Participant 5), “I have a strong con- nection with people in my school community” (Participant 4), “daily interactions with all types of personalities” (Participant 12) and “I am a personal and relational leader. My strength is building relationships across my school” (Participant 21). In addition, enthusiasm and passion “about quality teaching and quality learning” were attributes highlighted by three partici- pants (16, 17 & 24). Facilitating positive relationships within a school community requires positive personal attributes and is advocated as a leadership quality (see also Hudson & Hudson, 2011). Professional sharing with colleagues was noted by four par- ticipants (9, 15, 16, & 22) and was connected strongly with vision, knowledge, and capacity for leadership roles. Participant 9 stated, “I have a vision around what I would like to see hap- pen in our school/education system and how I would like peo- ple to behave and operate within that setting” and Participant 16 wrote, “Professional sharing, particularly in regards to progres- sive/innovative and non-traditional methods with the goal of educational progress is something about which I am passionate and determined” (Participant 16). There was recognition of one’s knowledge and capacity for undertaking leadership roles, to illustrate, Participant 22 claimed, “capacity to develop poten- tial of myself through collaborative practice, synthesis of edu- cational priorities, organisational and relational skills to drive change to improve pedagogy and student achievement” and Participant 15 noted, “Interest in professional development, curriculum, self improvement, leadership qualities”. Others within an organisation rely on the expertise of school leaders to share their professional knowledge and project a collective vision for moving an organisation forward (e.g., Bush, 2003; Gronn, 2002). In the context of mentoring, the mentee relies on the mentor’s knowledge and vision for teaching, particularly during the mentee’s formative stages of development. As the mentee matures in pedagogical practices, the mentor-mentee interaction becomes more of a shared arrangement, which can be likened to distributed leadership (e.g., Karkkainen, 2000). Six participants (2, 5, 8, 10, 20, & 21) were in leadership roles of varying intensities and drew upon past experiences for viewing their leadership potential and synergies with the men- toring role. For example, Participant 10 stated, “I have been a Deputy Principal for 12+ years”, while Participant 2 had “acted in a deputy capacity on 2 occasions. I am Year Level Coordi- nator and regular mentor for preservice teachers”. Participant 5 who was in a leadership role related to past experiences where she was able to “create an action plan and follow through and people love that I demonstrate consistency and I always do what I say and it’s practical”. There was also recognition that leadership required continuous learning, “I believe that as a leader I am constantly learning and seeking feedback in order to become a more effective school leader” (Participant 20). The practicalities of school leadership were outlined, especially the notion of continual growth development for the betterment of the school, which also may be achieved by taking on mentoring roles (e.g., Avalos, 2011). Although these participants were mentors, four participants appeared tentative about the idea of taking a permanent leader- ship role in a school. To illustrate, “I enjoy being part of a PLC and discussing key issues and philosophies, although I feel I can be reticent/unconfident in leading others to achieve goals I believe are important to attain” (Participant 18) and a willing- ness to commit to leadership roles: “I enjoy the challenge and satisfaction of leading and being a role model but feel I lack the time to move in this direction as well as effectively teach at times” (Participant 1). Yet some other participants believed they had potential to be leaders but appeared unsure on how to advance their ambitions. To illustrate, Participant 11 waited for recognition of leadership potential: “Our past deputy was trying to persuade me to apply for higher roles i.e. Deputy Principal’s position”, and Participant 19 believed she had leadership poten- tial but required more development: “I think that I have some of the qualities of a leader, which I’m hoping to develop with more experience”. Participant 12 claimed a readiness for transi- tioning from classroom practitioner to a leadership role high- lighting her foundational experiences: “Organising and manag- ing a classroom have given me a foundation on which to build and extend leadership skills. I believe I have something to offer others”. It seemed that some teachers wait to be recognised for their leadership potential; indeed existing school leaders need to be proactive in identifying leadership qualities within teaching staff (Pont, Nushe, & Moorman, 2008). This current study in- ferred that these classroom teachers may need to learn proactive skills for seeking leadership opportunities and positions, for which mentoring another adult (e.g., preservice teacher, begin- ning teacher) may be an initial step towards such roles. Opportunities for Leadership in Schools The participants (n = 25) wrote about their opportunities for leadership within their schools. Although many responses Open Access 89  P. HUDSON ranged from organising parent helpers and year level coordina- tion to executive leadership meetings, some of their comments did not explicitly state mentoring as a leadership opportunity. Nevertheless, their comments inferred mentoring practices as leadership, for instance, professional learning communities (PLCs) with common interests were outlined (e.g., ICT and Curriculum, Participant 10; Gifted and Talented Committee, Participant 16) and statements such as “Our teachers work closely together in sector groups which include a ‘Learning co-teacher’; they discuss, problem solve, plan and evaluate everything they do as a team” (Participant 4) and “Literacy coaching model” (Participant 9) inferred co-mentoring frame- works. Only one response explicitly mentioned mentoring as a leadership opportunity that is: “Through the mentor program developed we have the opportunity to observe each other’s practice in a non-threatening way and provide critical feedback to enhance our skills” (Participant 25). There appeared to be multiple opportunities for involvement in PLCs within schools with further opportunities to mentor others within these PLCs. When asked if mentoring preservice teachers supports the development of the teaching profession, all agreed with elabo- rations on why mentoring supports the profession. It was writ- ten that “mentoring during practice is critical for preservice teachers to effectively apply, reflect and improve” (Participant 1) and “sometimes a rewarding prac experience can stay with you for many years” (Participant 2). There was also the dual learning role of mentor and mentee, the notion of growth for both: “preservice teachers may have new ideas and knowledge to bring to classrooms and schools” (Participant 12) and “men- toring forces one to reflect on their own abilities” (Participant 16). Teachers’ professional growth can include mentoring processes (Avalos, 2011) where, in the mentor’s role, leader- ship capacities can be nurtured. Several participants were firm on why they were in or wanted to be in a leadership position. For instance, Participant 4, who was in a leadership role, stated unequivocally, “I need to challenge my teachers to be effective mentors and build the capacity of our future teaching workforce—not just have them for 4 weeks and say ‘well done’”. Participant 18 recognised that mentoring preservice teachers “provides opportunities for lead- ership for class teachers; promotes discussion and reflection of pedagogy” and that “every teacher (especially preservice teachers) needs a mentor, or a support person throughout their teaching careers” (Participant 19). Two participants emphasised the capacity building of mentoring by drawing on the expertise, to illustrate: “valuing and empowering these preservice teachers to provide education that is of the highest quality and makes a difference” (Participant 17), and “They are our future. So many years of experience is worth so much and the heartache we’ve been through at different times can be of benefit—there was a reason for the pain” (Participant 24). This presents a transfor- mational leadership approach where values and ethics appear at the centre of building capacity for achieving the organisational goals (see Avolio & Bass, 2002; Geijsel et al., 2003). Organisational Goals, Professional Skills, and Personal Attributes The participants were asked to think of an inspirational leader and determine the leader’s practices that inspired them. There was not one response that pointed to a single inspira- tional attribute or practice, instead they had multiple responses about inspirational leadership, for instance: Participant 12 out- lined an inspirational school leader who “has both a working relationship and a social relationship with staff, available to provide support and leadership with classroom issues (e.g. stu- dents) and practices”, Participant 1 wrote “Her enthusiasm and organisational skills and the perception that she had enough time to do everything effectively”, and: How they were able to improve the quality in the teaching going on in classrooms using various strategies. Their ability to inspire others to reach high expectations. Supportive of the teaching staff in every shape and form; being available to dis- cuss positives and grievances; able to improve standards (from dress code to thorough planning). Great conflict resolution skills. (Participant 17) Yet, their responses could be collated into three theoretical themes on inspirational school leaders, namely: 1) organisa- tional vision and goals, 2) professional skills, and 3) personal attributes (Figure 1). Leaders were considered inspiring if they were active and had clarity on the school’s goals, projecting a shared vision and ownership for achieving the goals. For example: “Clear articu- lation of personal vision and values; ability to persuade and motivate others so the vision becomes shared (collaborative ownership); delegating responsibility for outcomes and en- couraging ownership” (Participant 20). Organisational goals were further linked to how an inspirational school leader would assist the teacher to meet these goals. Instigating teachers’ re- flective abilities appeared as a key for focusing on these goals, to illustrate: the leader’s “ability to make you reflect on your own practice with an excellent knowledge and understanding of curriculum” (Participant 14). There were multiple professional skills of inspirational school leaders indicated by these partici- pants, but knowledge, acknowledging individuals, realistic expectations, and communication dominated their responses. To illustrate, one of these professional skills was acknowledg- ing individuals, which was claimed to instil confidence to suc- ceed, demonstrated through the following four comments: ● Currently at my school my principal inspires me to con- stantly strive to enhance my teaching practices. She is in- Figure 1. Synergies between inspirational leaders and mentors. Open Access 90  P. HUDSON Open Access 91 spirational as her leadership and diverse practices lead me to believe more in my own abilities as a teacher (Participant 11). ● She never failed to comment on your achievements and no matter how small (Participant 6). ● A strong belief in the potential of others around them and the willingness to give opportunities to other staff members —not just the big noters and noise makers of the group. Their belief in me (Participant 24). ● Their understanding of communication skills—importance of valuing and listening, non-judgemental of the small is- sues, guide with the big issues. Be real—understand we all need mentoring and coaching to be the best we can be (Par- ticipant 13). Inspirational school leaders were identified as having spe- cific personal attributes that allowed them to interact success- fully with others. Integrity, active listening, conflict resolution and enthusiasm (passion) were among the attributes, demon- strated in the following: ● A personal approach that showed integrity, which was used at all times with parents, staff and students (Participant 3). ● Ability to listen and understand and support through action and resolving of conflict through a plan. They were pas- sionate—had a bigger picture about the care of people (not tasks) (Participant 5). ● Energy and passion towards the advancement of education (teaching and learning practices); willingness/openness to ensure a shared or collaborative process (Participant 16). ● Willingness to actively listen; willingness to have hard conversations and make hard decisions (Participant 9). After these participants wrote about their inspirational school leaders, they wrote words that described their inspirational leaders on individual “Stick It” notes and then categorised on a word wall (i.e., notes were placed on a wall) where one group then attempted to categorise these responses. Table 1 presents these words aligned with three theoretical themes, viz: 1) or- ganisational vision and goals, 2) professional skills, and 3) personal attributes. At the conclusion of the exercise, partici- pants were invited to highlight any word that did not align with being a mentor. This presented as a high-level cognitive task as they evaluated words to determine which ones may not align. Surprisingly to the participants, they did not find one word not aligned with mentoring and, instead, comments from partici- pants concurred that, in the words of one participant, “if you mentor then you lead” and “they (pointing to the words) apply to both roles”. Narrative about Inspirational School Leaders Six small groups of participants stood in circles and were provided 15 minutes to talk about a school leader who had in- spired them. One person from each of the six groups was pro- vided with an audio recorder and their narratives were later transcribed by an experienced research assistant with a PhD. A leader’s personal attributes (e.g., enthusiasm and charisma) and professional skills (communicative) tended to be emphasised in their narratives, for instance, a male participant said: One of the first principals I taught under was a principal at a private Christian school. He was charismatic, passionate, pa- tient, knew how to speak to people to get the most calm sensible thing out of the most crazy, aggressive or emotional person. He spoke and people just listened. Nearly all participants had a specific narrative with an identi- fiable inspirational school leader. However, one female partici- pant explained how difficult it was to identify only one inspira- tional leader. When I’m thinking about a leader but I find to get someone who has all the things you look for in a leader I think is really difficult. Often you get little bits and pieces from everyone so you could put them all together and they’d be this person on a pedestal. But everyone brings something to the profession and I don’t know I find it difficult to pick out just one person but dif- ferent traits from each person and sometimes, someone might have the humour that I think is necessary in teaching but someone else might have the organisational skills, bits and pieces from everybody. I think ability to consider somebody else’s opinion and acknowledge the benefit of that even if you don’t implement it is important and not just to put it aside. Another participant focused on herself in a beginning teacher role and identified a colleague as an inspirational leader be- cause of her mentoring. Synergies between leadership and mentoring were made very clear through her narrative. To il- lustrate: When I first started teaching the person who I was put beside probably sticks in my mind a lot. She was probably a mentor to me as such and she just gave me the confidence. She inspired me to be the best teacher I can be, to be like her I guess. And yeah, I guess she took on a mentoring role without me probably knowing it at the time. Even the following year, I remember having heart failure because I wasn’t going to be beside her anymore. But she had a way about her ... lots of the things that she taught me have stuck with me and she was just a good sup- port and brought out the best in me. She inspired me to be better and to do better so I am better. She commands respect but the main thing about her is she walks the walk. She doesn’t just talk, she leads by example. She’s very charismatic, she’s quite an inspirational speaker in the staff meetings you find yourself captivated by her. As a leader she’s very, she’s just really supportive. She wants the best fo r all teache rs . She would pick up on what she thought was your strength Table 1. Words describing inspirational school leaders. Category Descriptive words Organisational goals innovative (n = 11), motivational/enabler (9), goal driven (8), visionary (5), organised (4), willingness to change (3), high standards (2) Professional skills knowledgeable (n = 11), acknowledges individual’s achievements (11), realistic expectations (7), communicative (6), conflict resolution (6), supportive (3), positive role model (3) Personal attributes integrity (n = 8), attentive listener (6), sense of humour (6), charasmatic/confident (5), empathetic (3), approachable (3), respectful (3), consistent (2), enthusiastic (2), maintaining positive relationships (2) Noe: Numbers represent the number of participants aligned with these words. t  P. HUDSON and then she would tailor you into doing more and more and more in your strength area and she really brought out, made the people shine, so it made you feel special and recognised. Further Leadership and Mentoring Connections They were asked what they intended to gain from this pro- fessional development, which was collated as: Knowledge and skills for mentoring (n = 15); leadership skills (10); achieving education system aims (6); and confidence to mentor (2). One participant wanted the professional development as a way to critical reflect on mentoring practices and another participant wanted connections with university. Examples of participant quotes about the knowledge and skills for mentoring included: “A specific mentoring program/module to present to teachers - encourage, promote, persuade, mentoring at our school” (Par- ticipant 21), “Personal knowledge and skills about effective mentoring” (Participant 4), and “Refine my own mentoring practices” (Participant 16). Only two specifically used the word leadership when asked what they hoped to gain from the pro- fessional development (e.g., “Further develop mentoring, and thus, leadership skills”, Participant 18; and “Confidence and leadership skills and ability to pay it forward for children’s benefit in general”, Participant 1). Nevertheless, eight other participants expressed leadership in different ways, for instance: “Empowerment—help others to mentor” (Participant 8) and “I hope to gain an understanding of how I can develop mentoring skills among my staff so that mentors can be used across the school for a variety of purposes including preservice teachers” (Participant 20). Capacity building also inferred leadership, such as the comment from Participant 22: “Build capability of teachers to learn from each other in context to develop peda- gogy to improve student achievement”. These participants were asked why they wanted to be men- tors, for which 15 indicated to develop successful, quality fu- ture teachers, particularly nurturing preservice teachers in sup- portive classroom environments. Their comments included: “To be able to share and develop in others ‘best’ practice. I believe in the importance of building capacity” (Participant 9), “I want to have the opportunity to be involved in increasing the amount of ‘quality’ teachers in state education” (Participant 12), and “I enjoy working with others and have a desire for them to suc- ceed” (Participant 6). Participant 8 stated simply, “I’m a nur- turer—‘beginners’ need to feel safe to risk take”. Leadership must embed capacity building to ensure an organisation con- tinues to grow (Dimmock, 2012). Indeed, there were 11 par- ticipants who wanted to share knowledge and experience on teaching practices (including praxis) with 4 who wanted to help school students as a result of their mentoring. Three were mo- tivated to provide more effective mentoring experiences be- cause of their own inadequate mentoring experiences as men- tees. For example, Participant 11 wrote, “Going through uni- versity I had one mentor who I felt didn’t support my growth as a teacher and I didn’t want that to happen to someone else” (Participant 11) and I had a terrible experience as a preservice teacher when I was 18 and as a result did not enter the teaching profession until 10 years later! I have had a good experience when men- toring and believe I am supportive and owe it to others. (Par- ticipant 5) There were values, ethics and morals intertwined within various comments, such as “so that preservice teachers don’t see it as a job but a privilege to make a difference to a child’s world” (Participant 17) and “to inspire the passion of teaching children” (Participant 3). Two participants wanted to mentor more effectively as they believed that the university provided theory but the schools were required to ensure preservice teachers had theory-practice connections, for example, “I al- ways felt with uni that you were given plenty of theories, but not enough time for prac—where you put these theories into action and learn the most” (Participant 19) and “I firmly believe that practical classroom experience for preservice teachers is extremely important to put theory and research into practical real-world situations” (Participant 2). Teachers step into lead- ership roles where they identify gaps that require addressing (e.g., Hudson, English, Dawes, & Macri, 2012; Ritchie & Hudson, 2009), for which these two participants in this study claimed gaps in contextualising university learning, where pos- sibly unknowingly, these participants have stepped up into leadership roles. Finally, two participants highlighted the pro- fessional development on mentoring as a way forward in lead- ership: “I believe it will make me a better leader. I wish to fur- ther develop my ability to provide feedback and improve my relational leadership” (Participant 20) and “Transfer to others my skills and beliefs around teaching and learning and inspire others to become good teachers” (Participant 21). A valuable aspect of mentoring is the mentor’s reflection on the mentoring process and relationships not only with the men- tee but also with other colleagues (Beutel & Spooner-Lane, 2009). As a result of this Mentoring for Effective Teaching (MET) professional development program, these participants had opportunities to critically self reflect on practices about mentoring and leadership. Correspondingly, critical self reflec- tion can enhance a mentor’s own outcomes with evidence cited to include: revitalisation or re-engagement with the profession; the gaining of new ideas, perspectives, teaching styles and strategies; increased confidence in their own teaching; in- creased empathy of the needs of their mentees; and satisfaction and pride in their own and their mentees’ accomplishments (Hobson, Ashby, Malderez, & Tomlinson, 2009). Experimen- tal-control group studies (Giebelhaus & Bowman, 2000; Hud- son & McRobbie, 2004) also show that professional develop- ment in mentoring can make a difference to the quality of men- toring received by preservice teachers. This study presented clear evidence that mentors are in lead- ership roles and that classroom teachers who take on mentoring roles become leaders. For many mentors, this may be their first opportunity to display leadership attributes and practices. Leadership comes in many forms with past research identifying leadership in terms of traits, behaviours, and characteristics (Bush, 2003; Burns, 1978; Yukl, 2006) and extending to trans- actional, transformational (Avolio & Bass, 2002), and distrib- uted leadership (Gronn, 2002). Scandura and Williams (2004) outline that transformational leadership with inspirational mo- tivation and respect produces commitment to the work and appears consistent with mentoring relationships. In addition, mentors provide opportunities to their mentees based on indi- vidualised consideration. However, this current study does not categorise participants’ identification of inspirational leadership attributes and practices in terms of previous models but instead presents a view that leaders and mentors considering these at- tributes and practices may assist to inspire others in their work. More research is needed to uncover how inspirational leader- ship attributes and practices can be presented as a complemen- tary or alternative model to existing models. Nevertheless, there Open Access 92  P. HUDSON were inferences that the leadership attributes and practices in this study may be indicative of transformational leadership and distributed leadership with particular links to mentoring situa- tions. Distributed leadership can act in co-leadership ways such as co-principalship (Gronn & Hamilton, 2004); similarly men- toring often extends to co-teaching situations. Distributed lead- ership holds promise for understanding mentor teachers who take up a leadership role in guiding their mentees towards pedagogical autonomy. It is argued in this paper that an effec- tive mentor distributes the leadership role to the mentee as a form of progressive pedagogical development. Conclusion In this study, there were strong synergies between mentoring and inspirational leadership. The theoretical contribution in- cluded determining similarities between leaders and mentors. According to the 25 participants, leaders were considered to be inspirational when they articulate organisational vision and goals, and have professional skills and exhibit personal attributes. When these participants reflected on the attributes and practices of inspirational school leaders and were provided opportunities to reflect on how these connected with mentoring, not one par- ticipant could single out an “inspirational school leader” attrib- ute or practice that would not apply to a mentor teacher. That is, it was highlighted by the participants that organisational vision and goals, professional skills and personal attributes of inspira- tional school leaders also apply to inspirational mentors. School leaders and mentor teachers need to take note on what constitutes inspirational leadership as a way of re-thinking their own attributes and practices. Indeed, mentor teachers can draw upon the attributes and practices of inspirational leaders to in- spire their mentees in teaching. Simultaneously, this research shows how school leaders can consider the inspirational attrib- utes and practices outlined by these participants to inspire teaching staff. For example, an awareness of attentive listening, motivational and visionary practices, and acknowledging indi- vidual achievements can guide school leaders and mentors to inspire others for achieving organsational goals. More research around the alignment of practices and attributes between lead- ers and mentors may uncover models to assist mentors in their leadership roles. Acknowledgements This work was conducted within the Teacher Education Done Differently (TEDD) project funded by the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Work- place Relations (DEEWR). Any opinions, findings, and conclu- sions or recommendations expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the DEEWR. I would like to acknowledge Dr Sue Hudson as the Project Leader. REFERENCES Altheide, D. L., & Johnson, J. M. (2011). Reflections on interpretive adequacy in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 581-594). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in Teaching and Teacher Education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 10-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007 Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (2002). Developing potential across a full range of leadership. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1997). Full range leadership development: Manual for the multifactor leadership questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Mindgarden. Beutel, D., & Spooner-Lane, R. (2009). Building mentoring capabilities in experienced teachers. The International Journal of Learning, 16, 351-360. Boseman, G. (2008). Effective leadership in a changing world. Journal of Financial Service Professionals, 62, 36-38. Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper Torchbooks. Bush, T. (2003). Theories of educational leadership and management (3rd ed.). London: SAGE Publications. Charmaz, K. (2011). Grounded theory methods in social justice re- search. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 359-380). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall. Dean, D. (2007). Thinking globally: The national college of school leadership: A case study in distributed leadership development. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 2, 1-62. Dimmock, C. (2012). Leadership, capacity building and school im- provement: Concepts, themes and impact. Abingdon: Routledge. Geijsel, F., Sleegers, P., Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2003). Transfor- mational leadership effects on teacher’s commitment and effort to- ward school reform. Journal of Educational Administration, 41, 228- 256. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09578230310474403 Giebelhaus, C. R., & Bowman, C. (2000). Teaching mentors: Is it worth the effort? Orlando, FL: The Annual Meeting of the Associa- tion of Teacher Educators. Gronn, P., & Hamilton, A. (2004). A bit more life in the leadership: Co-principalship as distributed leadership practice. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 3, 3-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1076/lpos.3.1.3.27842 Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership. In K. Leithwood, P. Hallinger, K. Seashore-Louis, G. Furman-Brown, P. Gronn, W. Mulford, & K. Riley (Eds.), Second international handbook of educational leader- ship and administration (pp. 653-696). Dordrecht: Kluwer. Harris, A. (2004). Distributed leadership and school improvement— Leading or misleading? Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 32, 11-24. Harris, A., & Chapman, C. (2002). Democratic leadership for school improvement in challenging contexts. Copenhagen: The International Congress on School Effectiveness and Improvement Conference. Hart, T. (1998). Inspiration: Exploring the experience and its meaning. Journal of Humanistic P sy c ho l o gy , 38, 7-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/00221678980383002 Hobson, A. J., Ashby, P., Malderez, A., & Tomlinson, P. D. (2009). Mentoring beginning teachers: What we know and what we don’t. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 207-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.001 Hudson, P. (2006). The status of mentoring primary science teaching in Australia. In Haigh, M., Beddoe, E., & Rose, D. (Eds.), Towards ex- cellence in PEPE: A collaborative endeavour: Proceedings of the Practical Experiences in Professional Education Conference. Auck- land, NZ: University of Auckland. Hudson, P. (2010). Mentors report on their own mentoring practices. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35, 30-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2010v35n7.3 Hudson, P., English, L., Dawes, L., & Macri, J. (2012). Contextualising university-school STEM education collaboration: Distributed and self-activated leadership for project outcomes. Educational Man- agement, Administration, and Leader ship, 40, 770-783. Hudson, P., & Hudson, S. (2011). Distributed leadership and profes- sional learning communities. Australian Journal of University- Community Engagement, 6, 1-17. Hudson, P., & McRobbie, C. (2004). Evaluating a specific mentoring intervention for preservice teachers of primary science. Action in Teacher Education, 1 7 , 7-35. John, K. (2008). Sustaining the leaders of children’s centres: The role Open Access 93  P. HUDSON Open Access 94 of leadership mentoring. European Early Childhood Education Re- search Journal, 16, 53-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13502930801897012 Karkkainen, M. (2000). Teams as network builders: Analysing network contacts in Finnish elementary school teacher teams. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 44, 371-391. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713696683 Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2007). The leadership challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Kunich, J. C., & Lester, R. I. (1999). Leadership and the art of mentor- ing: Tool kit for the time machine. Journal of Leadership, 1-2, 117- 127. http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/au-24/kunich.pdf Lockwood, P., Jordan, C.H., & Kunda, Z. (2002). Motivation by posi- tive and negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 83, 854- 864. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.854 Moberg, D. J. (2008). Mentoring for protege character development. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partne rs hi p in Learning, 16, 91-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13611260701801056 Pont B., Nushe, D., & Moorman, H. (2008). Improving school leader- ship, volume 1: Policy and practice. Paris: OECD. www.oecd.org/dataoecd/6/52/40545479.pdf Rippon, J. H., & Martin, M. (2006). What makes a good induction supporter? Teaching and Tea che r Education, 22, 84-99. Ritchie, S. M., & Hudson, P. (2009). Science teacher leadership for transforming the curriculum and classroom practice. In S. M. Ritchie (Ed.), The world of science education: Handbook of research in Aus- tralasia (pp. 273-283). Rotterdam: Sensepublishers. Scandura, T. A., & Williams, E. A. (2004). Mentoring and transforma- tional leadership: The role of supervisory career mentoring. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65, 448-468. Shoaf, M., & Britt, M. M. (2009). Leadership and mentoring: How different are they? Proceedings of ASBBS Conference, 16, 4. http://asbbs.org/files/2009/PDF/B/BrittM.pdf Simmons, S. R. (2007). “Amazing Grace”: A memoir of mentoring. Journal of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Educat io n , 36, 1-5. Spillane, J., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. B. (2001). Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educational Researcher, 30, 23-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X030003023 Trottier, T., Van Wart, M., & Wang, X. H. (2008). Examining the na- ture and significance of leadership in government organizations. Public Administration Review, 68, 319-333. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00865.x Vaughan, G. M., & Hogg, M. A. (2011). Social psychology (6th ed.). Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Australia. Yukl, G. A. (2006). Leadership in organisations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Zachary, L. (2009). Examining and expanding mentoring practice. Adult Learning, 1, 43-45.

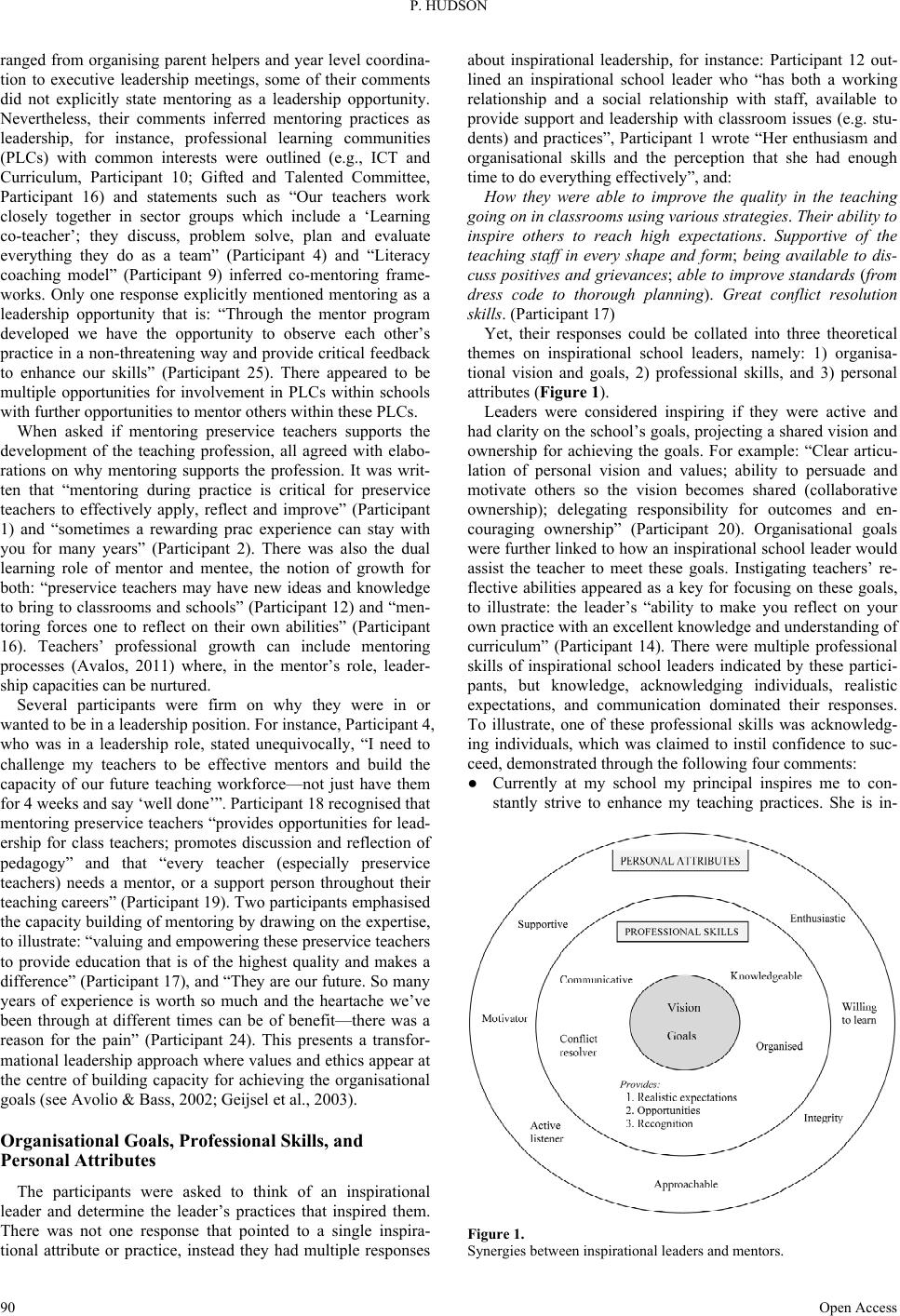

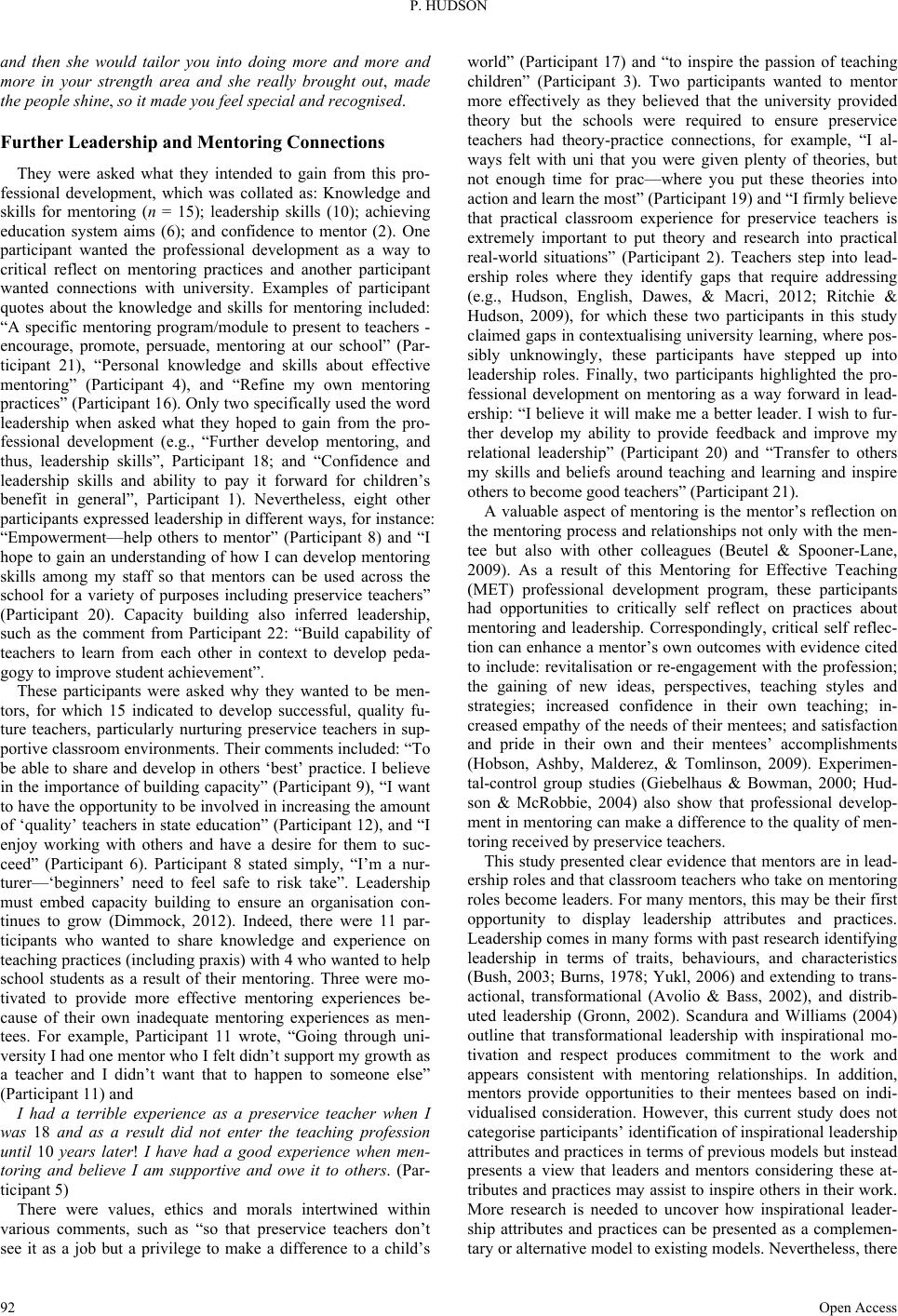

|