Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

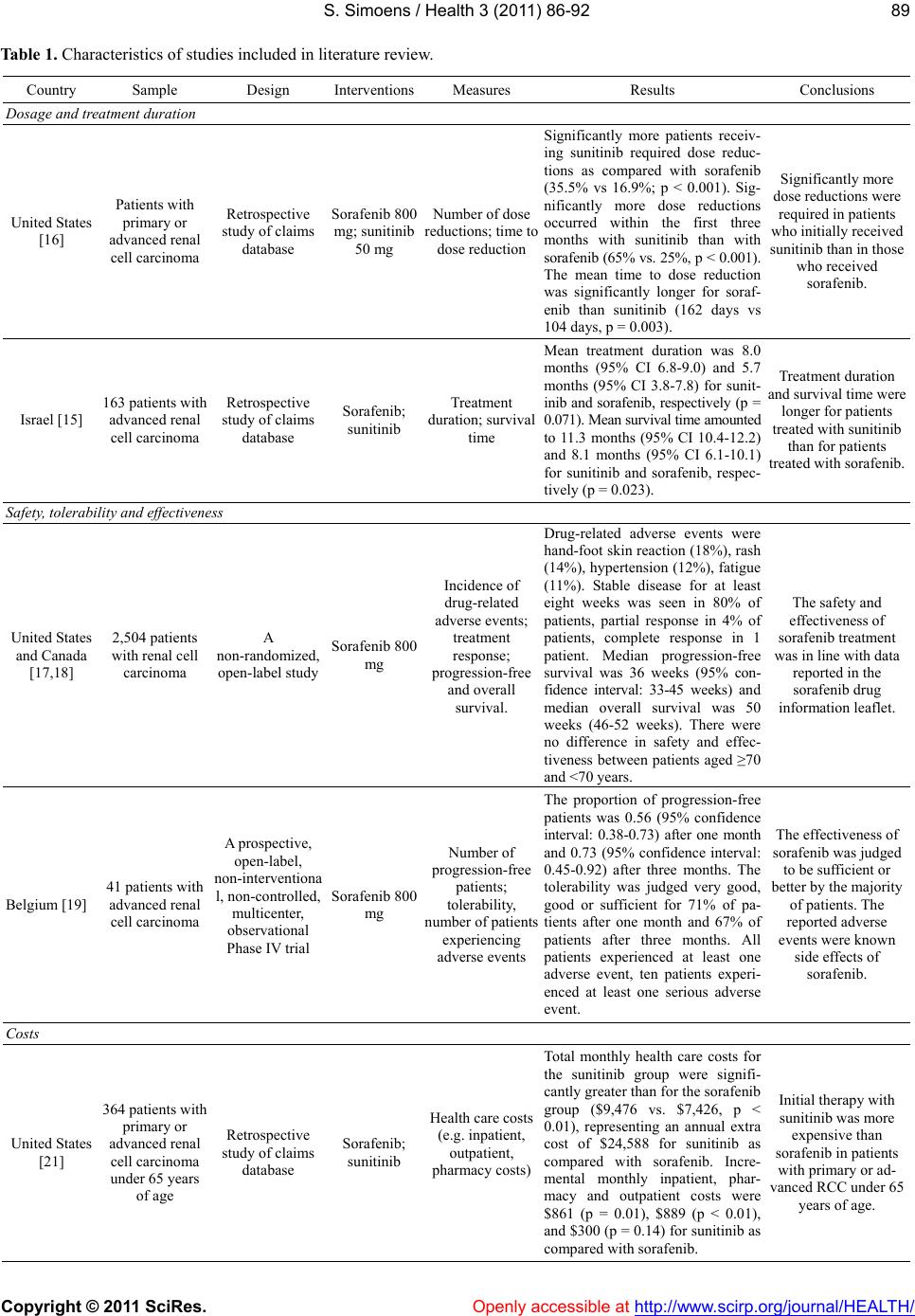

Vol.3, No.2, 86-92 (2011) Health doi:10.4236/health.2011.32016 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Sorafenib for advanced renal cell carcinoma in real-life practice: a literature review* Steven Simoens Research Centre for Pharmaceutical Care and Pharmaco-economics, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; steven.simoens@pharm.kuleuven.be Received 3 November 2010; revised 12 January 2011; accepted 17 January 2011 ABSTRACT Sorafenib is a new treatment indicated for pa- tients with advanced renal cell carcinoma who have failed prior cytokine-based therapy or are considered unsuitable for such therapy. Al- though treatment with sorafenib under ‘ideal trial conditions’ has been extensively studied, registration and reimbursement authorities are also interested in the behavior of sorafenib in real-life practice. This study aims to conduct a literature review of the dosage and treatment duration; safety, tolerability and effectiveness; costs and cost-effectiveness of sorafenib in routine clinical care. Studies were identified by searching PubMed, Embase, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination databases, Cochrane Data- base of Systematic Reviews, and EconLit up to November 2010. The literature search included articles published in peer-reviewed journals, congress abstracts, and internal studies of Bayer Schering Pharma. Eight studies were in- cluded. An open-label study observed stable disease for at least eight weeks in 80% of pa- tients. The most common drug-related adverse events were hand-foot skin reaction, rash, hy- pertension, and fatigue. Although treatment with sorafenib led to fewer dose reductions, it was also associated with a shorter treatment duration, less time to progression and a shorter survival time as compared to sunitinib. Monthly health care costs were lower with sorafenib as compared to sunitinib. A post-marketing sur- veillance study showed that patients rated the tolerability and effectiveness of sorafenib as very good, good or sufficient. In conclusion, the current evidence is too limited to derive con- clusions and existing studies suffer from me- thodological shortcomings. Keywords: Sorafenib; Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma; Real-Life Practice; Literature Revie w 1. INTRODUCTION Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for approxi- mately 2% of all cancer cases [1]. It is the most common form of kidney cancer and 25%–30% of patients present with advanced (metastatic) disease at time of diagnosis. An epidemiological literature review reported an annual incidence of advanced RCC in major European countries, the United States and Japan ranging from 1,500 to 8,600 cases [2]. The economic burden of advanced RCC has been estimated at $107–$556 million in the United States in 2006 [2]. Advanced RCC is a treatment-resistant malignancy: patients who present with advanced disease have a poor prognosis and median survival after diagnosis is less than one year. Few effective therapeutic options are available [3]. Surgery has limited or no effect. Cytokines, which have been the mainstay of therapy for RCC, are associated with significant toxicities. High dose inter- leukin-2 provides clinical benefit to a relatively small percentage of patients and has a significant toxicity pro- file. Interferon alpha is associated with a modest re- sponse rate and limited tolerability for many patients. For patients who fail cytokine therapy or for whom these therapies are not suitable, therapeutic options are limited. Therefore, the need for new and more effective therapies is high. Treatment of advanced RCC may benefit from novel agents, such as molecularly targeted therapies. One such therapy, sorafenib (Nexavar®), is indicated for patients with advanced RCC who have failed prior cyto- kine-based therapy or are considered unsuitable for such therapy [4]. In preclinical models, sorafenib decreased angiogenesis through upstream inhibition of receptor tyrosine kinases Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor (VEGFR) and Platelet Derived Growth Factor Receptor (PDGFR) as well as serine/threonine kinases in *Financial support was received from Bayer Schering Pharma.  S. Simoens / Health 3 (2011) 86-92 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 8787 the RAF/MEK/Extracellular signal Regulated Kinase (RAF/MEK/ERK) pathway. Sorafenib also decreased tumor cell proliferation through upstream inhibition of receptor tyrosine kinases KIT and Fms like Tyrosine Kinase 3 (FLT-3) [5-7]. In a randomized discontinuation Phase II study, pa- tients with metastatic malignancies, including RCC pa- tients with stable disease on sorafenib therapy, were randomized to placebo or continued sorafenib therapy [8]. Progression-free survival in patients with RCC was significantly longer in the sorafenib group (163 days) than in the placebo group (41 days) (p = 0.0001, hazard ratio = 0.30). In the largest, international, Phase III study in ad- vanced RCC, the Treatment Approaches in Renal Cancer Global Evaluation Trial [TARGET] [9], sorafenib dou- bled median progression-free survival, 24 weeks versus 12 weeks, as compared with placebo (p < 0.000001; haz- ard ratio = 0.40; 95% confidence interval: 0.40-0.55). Age, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) prognostic group, Eastern Cooperative Cancer Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) and prior therapy did not significantly affect the treatment effect size. In the second interim analysis for overall survival, the median survival was 19.3 months for patients randomized to sorafenib as compared to 15.9 months for placebo pa- tients (hazard ratio = 0.77; 95% confidence interval: 0.63-0.95; p = 0.015). This second interim analysis was conducted following cross-over from placebo patients to active treatment at the recommendation of the data monitoring committee. The most common drug-related adverse events associated with sorafenib therapy are diarrhea, rash, alopecia and hand-foot skin reaction [4]. Treatment of advanced RCC with sorafenib under “ideal trial conditions” has been extensively studied. Literature studies have reviewed the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profile, therapeutic efficacy, toler- ability, dosage and administration of sorafenib [10-12]. The cost-efficacy has been assessed in a number of eco- nomic evaluations [13]. In addition to such evidence, registration and reimbursement authorities are interested in the behavior of a drug in real-life practice, its effec- tiveness and cost-effectiveness. Such data provide evi- dence of the impact of a drug when for example patients do not fulfill the inclusion criteria for randomized con- trolled trials or do not fully comply with pharmacother- apy. The aim of this study is to conduct a review of the in- ternational literature examining the treatment of ad- vanced RCC with sorafenib in routine clinical care. The literature study focuses specifically on the dosage and treatment duration; safety, tolerability and effectiveness; costs and cost-effectiveness of sorafenib. The findings may serve to aid local decision-makers in allocating scarce health care resources and to inform the prescrib- ing behavior of physicians. 2. METHODS 2.1. Search Strategy Studies were identified by searching PubMed, Embase, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination databases (Data- base of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database, and Health Technology Assessments Database), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and EconLit up to November 2010. Additionally, the bibliography of included studies was checked for other relevant studies. Search terms included ‘renal cell carcinoma’, ‘kidney cancer’, ‘ad- vanced’, ‘metastatic’, ‘nexavar’, ‘sorafenib’, ‘dosage’, ‘treatment duration’, ‘safety’, ‘tolerability’, ‘effective- ness’, ‘costs’, ‘cost-effectiveness’, ‘economic evalua- tion’, ‘real life’, ‘routine clinical care’ alone and in com- bination with each other. The literature search included articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Relevant congress abstracts were identified by searching the congress database of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Out- comes Research Digest, an electronic database of ab- stracts presented at conferences of the International So- ciety of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. Finally, Bayer Schering Pharma was contacted for any unpublished studies. 2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria The review was limited to the use of sorafenib in ad- vanced RCC. Other registered indications (i.e. hepato- cellular carcinoma) fell outside the scope of this study. The literature review included studies on the treatment of advanced RCC with sorafenib in real-life practice. Clinical studies exploring the safety, tolerability and efficacy of sorafenib under “ideal trial conditions” were excluded. Cost studies were included if they compared health care and/or other costs of sorafenib and an alter- native treatment for advanced RCC. Evidence about cost-effectiveness was derived from economic evalua- tions. An economic evaluation was defined as a study comparing sorafenib with an alternative treatment in terms of both costs and consequences [14]. Economic evaluations were excluded if treatment of advanced RCC did not involve sorafenib or if studies analyzed a single intervention without a comparator. The review was limited to studies published in Eng- lish, French, Dutch, or German for practical reasons.  S. Simoens / Health 3 (2011) 86-92 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 88 3. RESULTS 3.1. Search Results Few studies have focused on the treatment of ad- vanced RCC with sorafenib in real-life practice. The researcher identified 89 citations, but only eight studies were included in the review: two studies exploring dos- age and treatment duration [15,16], two pre-marketing surveillance studies [17,18] and one post-marketing sur- veillance study [19], two analyses of a claims database [20,21], and one economic evaluation [22]. The charac- teristics of included studies are presented in Table 1. 3.2. Dosage and Treatment Duration A retrospective analysis of a US claims database in- vestigated dose-reduction patterns in patients with pri- mary or advanced RCC treated with sorafenib or sunit- inib [16]. The initial daily dosage was sorafenib 800 mg or sunitinib 50 mg. Demographic characteristics were similar between the two groups, except for a higher in- cidence of stroke (7.9% vs 3.6%, p = 0.037) and other cancer site (93.7% vs. 87.8%, p = 0.036) in the sorafenib group. Significantly more patients receiving sunitinib required dose reductions as compared with sorafenib (35.5% vs 16.9%; p < 0.001). Significantly more dose reductions occurred within the first three months with sunitinib than with sorafenib (65% vs. 25%, p < 0.001). The mean time to dose reduction was significantly long- er for sorafenib than sunitinib (162 days vs 104 days, p = 0.003). These findings show that more dose reductions were required in patients who initially received sunitinib than in those who received sorafenib. An Israeli study explored treatment duration and sur- vival in patients with advanced RCC receiving first-line treatment with either sorafenib or sunitinib [15]. Demo- graphic and claims data were extracted from a health services database. Treatment duration and patient sur- vival were calculated and compared using a Kap- lan-Meier analysis. The sample included 134 patients receiving sunitinib and 29 patients receiving sorafenib. There were no differences in demographic characteris- tics between patient groups. Mean treatment duration was 8.0 months (95% CI 6.8-9.0) and 5.7 months (95% CI 3.8-7.8) for sunitinib and sorafenib, respectively (p = 0.071). Mean survival time amounted to 11.3 months (95% CI 10.4-12.2) and 8.1 months (95% CI 6.1-10.1) for sunitinib and sorafenib, respectively (p = 0.023). It should be noted that this analysis enrolled a small num- ber of patients receiving sorafenib. Also, future analyses must control for patient clinical characteristics, which may have been a major factor in treatment preferences, and might have influenced treatment duration and sur- vival. 3.3. Safety, Tolerability and Effectiveness A non-randomized, open-label expanded access pro- gramme included 2,504 patients from the United States and Canada who were treated with oral sorafenib 400 mg twice daily [18]. This programme provided access to sorafenib prior to regulatory approval and did not im- pose strict patient inclusion criteria. The most common drug-related adverse events were hand-foot skin reaction (18%), rash (14%), hypertension (12%), and fatigue (11%). Stable disease for at least eight weeks was ob- served in 80% of patients, partial response in 4% of pa- tients, and complete response in one patient. Median progression-free survival amounted to 36 weeks (95% confidence interval: 33-45 weeks) and median overall survival was 50 weeks (95% confidence interval: 46-52 weeks). An additional analysis did not observe any sub- stantial differences in safety and effectiveness of soraf- enib between patients aged ≥70 and <70 years [17]. A prospective, open-label, non-interventional, non- controlled, multicenter, observational Phase IV trial evaluated the effectiveness and safety of sorafenib treatment under daily-life conditions in Belgium [19]. A small sample of 41 patients was enrolled from 32 study centers. Twenty-four patients discontinued the study prematurely. The reason indicated most frequently was disease progression (11 patients). Only 34 and 15 pa- tients could be evaluated after one and three months of observation, respectively. The effectiveness of sorafenib was judged sufficient, good or very good (as opposed to ‘insufficient’) for most patients after one month and after three months. The proportion of progression-free pa- tients was 0.56 (95% confidence interval: 0.38-0.73) after one month and 0.73 (95% confidence interval: 0.45-0.92) after three months. The proportion tended to increase over time, though the fact that these proportions were calculated over the patients still observed (i.e. the “healthier” patients) could explain this trend. The toler- ability was judged very good, good or sufficient for 71% of patients after one month and 67% of patients after three months. All patients experienced at least one ad- verse event, ten patients experienced at least one serious adverse event. Among the reported adverse events, there were eight patients with diarrhea, six patients with ano- rexia, five patients with hand foot skin reaction and five patients with rash. These adverse events are known side effects of sorafenib [4]. 3.4. Costs Based on an analysis of a US claims database, a retro- spective study quantified the health care costs of patients  S. Simoens / Health 3 (2011) 86-92 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 8989 Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in literature review. Country Sample Design InterventionsMeasures Results Conclusions Dosage and treatment duration United States [16] Patients with primary or advanced renal cell carcinoma Retrospective study of claims database Sorafenib 800 mg; sunitinib 50 mg Number of dose reductions; time to dose reduction Significantly more patients receiv- ing sunitinib required dose reduc- tions as compared with sorafenib (35.5% vs 16.9%; p < 0.001). Sig- nificantly more dose reductions occurred within the first three months with sunitinib than with sorafenib (65% vs. 25%, p < 0.001). The mean time to dose reduction was significantly longer for soraf- enib than sunitinib (162 days vs 104 days, p = 0.003). Significantly more dose reductions were required in patients who initially received sunitinib than in those who received sorafenib. Israel [15] 163 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma Retrospective study of claims database Sorafenib; sunitinib Treatment duration; survival time Mean treatment duration was 8.0 months (95% CI 6.8-9.0) and 5.7 months (95% CI 3.8-7.8) for sunit- inib and sorafenib, respectively (p = 0.071). Mean survival time amounted to 11.3 months (95% CI 10.4-12.2) and 8.1 months (95% CI 6.1-10.1) for sunitinib and sorafenib, respec- tively (p = 0.023). Treatment duration and survival time were longer for patients treated with sunitinib than for patients treated with sorafenib. Safety, tolerability and effectiveness United States and Canada [17,18] 2,504 patients with renal cell carcinoma A non-randomized, open-label study Sorafenib 800 mg Incidence of drug-related adverse events; treatment response; progression-free and overall survival. Drug-related adverse events were hand-foot skin reaction (18%), rash (14%), hypertension (12%), fatigue (11%). Stable disease for at least eight weeks was seen in 80% of patients, partial response in 4% of patients, complete response in 1 patient. Median progression-free survival was 36 weeks (95% con- fidence interval: 33-45 weeks) and median overall survival was 50 weeks (46-52 weeks). There were no difference in safety and effec- tiveness between patients aged ≥70 and <70 years. The safety and effectiveness of sorafenib treatment was in line with data reported in the sorafenib drug information leaflet. Belgium [19] 41 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma A prospective, open-label, non-interventiona l, non-controlled, multicenter, observational Phase IV trial Sorafenib 800 mg Number of progression-free patients; tolerability, num b er of patients experiencing adverse events The proportion of progression-free patients was 0.56 (95% confidence interval: 0.38-0.73) after one month and 0.73 (95% confidence interval: 0.45-0.92) after three months. The tolerability was judged very good, good or sufficient for 71% of pa- tients after one month and 67% of patients after three months. All patients experienced at least one adverse event, ten patients experi- enced at least one serious adverse event. The effectiveness of sorafenib was judged to be sufficient or better by the majority of patients. The reported adverse events were known side effects of sorafenib. Costs United States [21] 364 patients with primary or advanced renal cell carcinoma under 65 years of age Retrospective study of claims database Sorafenib; sunitinib Health care costs (e.g. inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy costs) Total monthly health care costs for the sunitinib group were signifi- cantly greater than for the sorafenib group ($9,476 vs. $7,426, p < 0.01), representing an annual extra cost of $24,588 for sunitinib as compared with sorafenib. Incre- mental monthly inpatient, phar- macy and outpatient costs were $861 (p = 0.01), $889 (p < 0.01), and $300 (p = 0.14) for sunitinib as compared with sorafenib. Initial therapy with sunitinib was more expensive than sorafenib in patients with primary or ad- vanced RCC under 65 years of age.  S. Simoens / Health 3 (2011) 86-92 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 90 United States [20] 321 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma Retrospective study of claims database Intravenous bevacizumab; sorafenib; sunitinib Health care costs (e.g. inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy costs) Total mean health care costs amounted to $13,351, $6,998, and $8,213 per patient per month for bevacizumab, sorafenib and sunit- inib, respectively (p < 0.05). Health care costs of sorafenib treatment were lower than those of treatment with bevacizumab or sunitinib. Cost-effectiveness Czech Repub- lic [22] 31 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma Economic evaluation based on cohort study Sorafenib; sunitinib Adverse events; time to progression; costs to progression; mortality The main adverse events were skin toxicity, oedema, arthralgia and other pain. The mean time to pro- gression was 8.3 months with sorafenib and 10.4 months with sunitinib. The mean cost to pro- gression was €1,069 with sorafenib and €1,566 with sunitinib. Nine patients died. The analysis of direct medical costs in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma proved high costs concerned with multikinase inhibitors´ therapy. with primary or advanced RCC who are privately in- sured and are aged under 65 years [21]. Health care costs included inpatient, outpatient and pharmacy costs. The sample consisted of 144 patients receiving sorafenib and 220 patients receiving sunitinib as initial therapy. At baseline, demographic characteristics between the two patient groups were similar. Total monthly health care costs for the sunitinib group were significantly greater than for the sorafenib group ($9,476 vs. $7,426, p < 0.01), representing an annual extra cost of $24,588 for sunitinib as compared with sorafenib. Incremental monthly inpatient, pharmacy and outpatient costs were $861 (p = 0.01), $889 (p < 0.01), and $300 (p = 0.14) for sunitinib as compared with sorafenib. This analysis showed that initial therapy with sunitinib was more ex- pensive than sorafenib in patients with primary or ad- vanced RCC aged under 65 years. A US retrospective claims database analysis quanti- fied the incremental costs associated with intravenous administration of bevacizumab as compared to sunitinib or sorafenib for the treatment of advanced RCC [20]. Patients receiving bevacizumab (n = 109) were matched 1:1 to patients receiving sorafenib or sunitinib. Drug, inpatient, outpatient and pharmacy costs were calculated per patient per month. Total mean health care costs amounted to $13,351, $6,998, and $8,213 per patient per month for bevacizumab, sorafenib and sunitinib, respec- tively (p < 0.05). Assuming a median progression-free survival of 8.5 months as shown for bevacizumab, the incremental costs would be estimated at $39,188-42,080 per patient as compared to those treated with sorafenib or sunitinib. 3.5. Cost-effectiveness An economic evaluation assessed the cost-effectiveness of sorafenib and sunitinib in routine clinical care in the Czech Republic from a health care payer perspective [22]. Disease progression and costs (i.e. drugs, labora- tory tests and hospitalization) were assessed every two months. Seventeen patients started therapy with sunitinib, eight of whom converted to sorafenib after progression. Three patients discontinued sunitinib therapy due to ad- verse events. Fourteen patients started sorafenib therapy, two of whom converted to sunitinib due to adverse events. Two other patients converted to sunitinib fol- lowing progression. The main adverse events were skin toxicity, oedema, arthralgia and other pain. The mean time to progression was 8.3 months with sorafenib and 10.4 months with sunitinib. The mean cost to progres- sion was €1,069 with sorafenib and €1,566 with sunit- inib. Nine patients died. Cost and outcome measures were not combined into an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. 4. DISCUSSION This article has conducted a literature review of the treatment of advanced RCC with sorafenib in routine clinical care. The evidence is too limited to derive con- clusions and studies suffer from methodological short- comings. The current evidence base is restricted to a few studies presented at international conferences, one peer-reviewed article and one internal study of Bayer Schering Pharma. Furthermore, as advanced RCC is an orphan disease, the majority of studies suffered from small sample sizes. Existing studies have primarily compared treatment with sorafenib or with sunitinib. Although treatment with sorafenib led to fewer dose reductions, it was also asso- ciated with a shorter treatment duration, less time to progression and a shorter survival time as compared to sunitinib. Monthly health care costs were lower with sorafenib as compared to sunitinib. A post-marketing surveillance study showed that patients rated the toler- ability and effectiveness of sorafenib as very good, good or sufficient, although this study suffered from a small sample size and limited time horizon.  S. Simoens / Health 3 (2011) 86-92 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 9191 To date, little is known about the (cost-) effectiveness of sorafenib as compared with other approaches to treat advanced RCC in routine clinical care. Although analy- ses based on cohort studies, case-control studies, or be- fore-and-after studies may suffer from a number of bi- ases and do not always establish a causal relationship, such studies would provide information about the safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of sorafenib in real-life practice. Information derived from such studies could be integrated with cost information to conduct an economic evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of sorafenib as compared with other approaches to treat advanced RCC. It is important to examine the impact of a drug in real-life practice. Registration authorities wish to gain insight into the health gain of the drug in real-life pa- tients, to identify rare adverse events, to explore the ef- fectiveness in the long run, or to study the drug as a treatment for other diseases. Also, reimbursement au- thorities in some countries grant conditional reimburse- ment to a drug based on its cost-efficacy, while final reimbursement is granted based on its cost-effectiveness after the drug has been on the market for a number of years. For instance, on 1st April 2007, Belgian reim- bursement authorities conditionally approved the reim- bursement of sorafenib treatment for advanced RCC for a period of three years. The sponsor was obliged to sub- mit complementary observational data including clinical and economic data within 1.5 to 3 years after conditional approval. Final reimbursement approval was granted in August 2010. One instrument to sustain the ongoing evaluation of a drug may be the implementation of patient registries designed to collect the necessary data to follow up and evaluate uncertainties surrounding the longer-term effec- tiveness and cost-effectiveness of a drug [23]. The use of patient registries would support the decision-making process, inform clinical practice, and could provide in- formation about long-term adverse events. However, patient registries have their limitations. A patient registry may be biased if the patient aetiology and disease sever- ity change over time. Also, patient registries tend to col- lect data on a specific drug, but not on alternative treat- ments, thus providing partial information to calculate the cost-effectiveness of the drug relative to an alternative treatment. Furthermore, new treatment strategies may become available during the period covered by the reg- istry. Therefore, patient registries need to be set up in a flexible way to collect sufficient data and to account for the evolution in patient population and treatment strate- gies over their lifetime. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author has no conflicts of interest that are relevant to the content of this manuscript REFERENCES [1] Belgian Cancer Registry. (2010) Cancer registry data. http://www.registreducancer.be. [2] Gupta, K., Miller, J.D., Li, J.Z., Russell, M.W., Char- bonneau, C. (2008) Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a lit- erature review. Cancer Treat Review, 34, 193-205. [3] Ather, M.H., Masood, N., Siddiqui, T. (2010) Current management of advanced and metastatic renal cell carci- noma. Urology Journal, 7, 1-9. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.001 [4] European Medicines Agency. (2006) EU Summary of Product Characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/me dicines/human/medicines/000690/human_med_000929. jsp&murl=menus/medicines/medicines.jsp. [5] Adjei, A.A., Hidalgo, M. (2005) Intracellular signal transduction pathway proteins as targets for cancer ther- apy. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 5386-5403. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.23.648 [6] Kim, W.Y., Kaelin, W.G. (2004) Role of VHL gene muta- tion in human cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22, 4991-5004. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.05.061 [7] Wilhelm, S.M., Carter, C., Tang, L. et al. (2004) BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and an- giogenesis. Cancer Research, 64, 7099-7109. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443 [8] Ratain, M.J., Eisen, T., Stadler, W.M. et al. (2006) Phase II placebo-controlled randomized discontinuation trial of sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24, 2505-2512. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6723 [9] Escudier, B., Eisen, T., Stadler, W.M. et al. (2007) Sora- fenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine, 356, 125-134. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060655 [10] Flaherty, K.T. (2007) Sorafenib in renal cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research, 13, 747-752. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2063 [11] Flaherty, K.T. (2007) Sorafenib: delivering a targeted drug to the right targets. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy, 7, 617-626. doi:10.1586/14737140.7.5.617 [12] McKeage, K., Wagstaff, A.J. (2007) Sorafenib: in ad- vanced renal cancer. Drugs, 67, 475-483. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767030-00009 [13] Norum, J., Nieder, C., Kondo, M. (2010) Sunitinib, sora- fenib, temsirolimus or bevacizumab in the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a review of health eco- nomic evaluations. Journal of Chemotherapy, 22, 75-82. [14] Drummond, M., Sculpher, M.J., Torrance, G.W., O'Brien, B.J., Stoddart, G.L. (2005) Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [15] Hammerman, A., Klang, S., Liebermann, N. (2009) Real life treatment duration of sorafenib or sunitinib in first line metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients - a compara- tive analysis. 12th ISPOR Annual European Congress,  S. Simoens / Health 3 (2011) 86-92 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 92 Paris. [16] Keefe, M., Moyneur, E., Barghout, V. (2009) A retro- spective claims database comparison of sorafenib and sunitinib dosing patterns in patients with renal cell car- cinoma. 14th ISPOR Annual International Meeting, Or- lando. [17] Bukowski, R.M., Stadler, W.M., McDermott, D.F. et al. (2010) Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in elderly patients treated in the North American advanced renal cell carci- noma sorafenib expanded access program. Oncology, 78, 340-347. doi:10.1159/000320223 [18] Stadler, W.M., Figlin, R.A., McDermott, D.F. et al. (2010) Safety and efficacy results of the advanced renal cell car- cinoma sorafenib expanded access program in North America. Cancer, 116, 1272-1280. doi:10.1002/cncr.24864 [19] Simoens, S., Parmet, B., van Dijck, W. (2010) Prospec- tive open-label non-interventional non-controlled multi- center observational Phase IV trial to evaluate the effec- tiveness and safety of Nexavar® treatment under dai- ly-life treatment conditions. Data on file. [20] Duh, M.S., Dial, E., Choueiri, T.K. et al. (2009) Cost implications of IV versus oral anti-angiogenesis therapies in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: retro- spective claims database analysis. Current Medical Re- search and Opinion, 25, 2081-2090. doi:10.1185/03007990903084800 [21] Quinn, D., Barghout, V., Moyneur, E. (2009) Retrospec- tive claims database analysis of the direct medical costs associated with sorafenib and sunitinib in the treatment of patients with renal cell carcinoma who are under 65 years old. 14th ISPOR Annual International Meeting, Or- lando. [22] Demlova, R., Ondrackova, B., Kominek, J. (2009) The economic evaluation of sunitinib and sorafenib in MRCC patients in the Czech Republic. 12th ISPOR Annual Eu- ropean Congress, Paris. [23] Denis, A., Mergaert, L., Fostier, C., Cleemput, I., Si- moens, S. (2010) Issues surrounding orphan disease and orphan drug policies in europe. Applied Health Econom- ics and Health Policy, 8, 343-350. doi:10.2165/11536990-000000000-00000 |