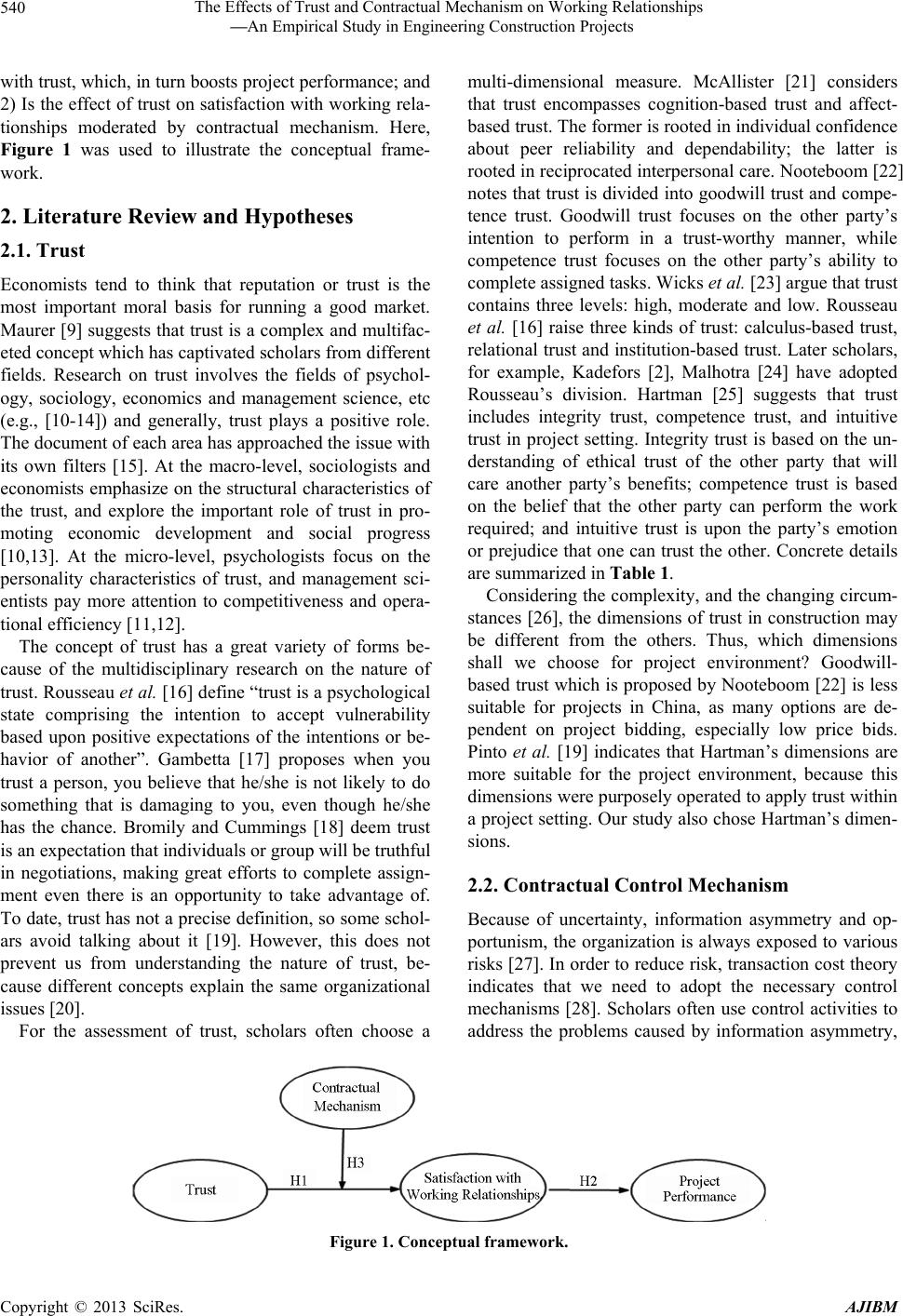

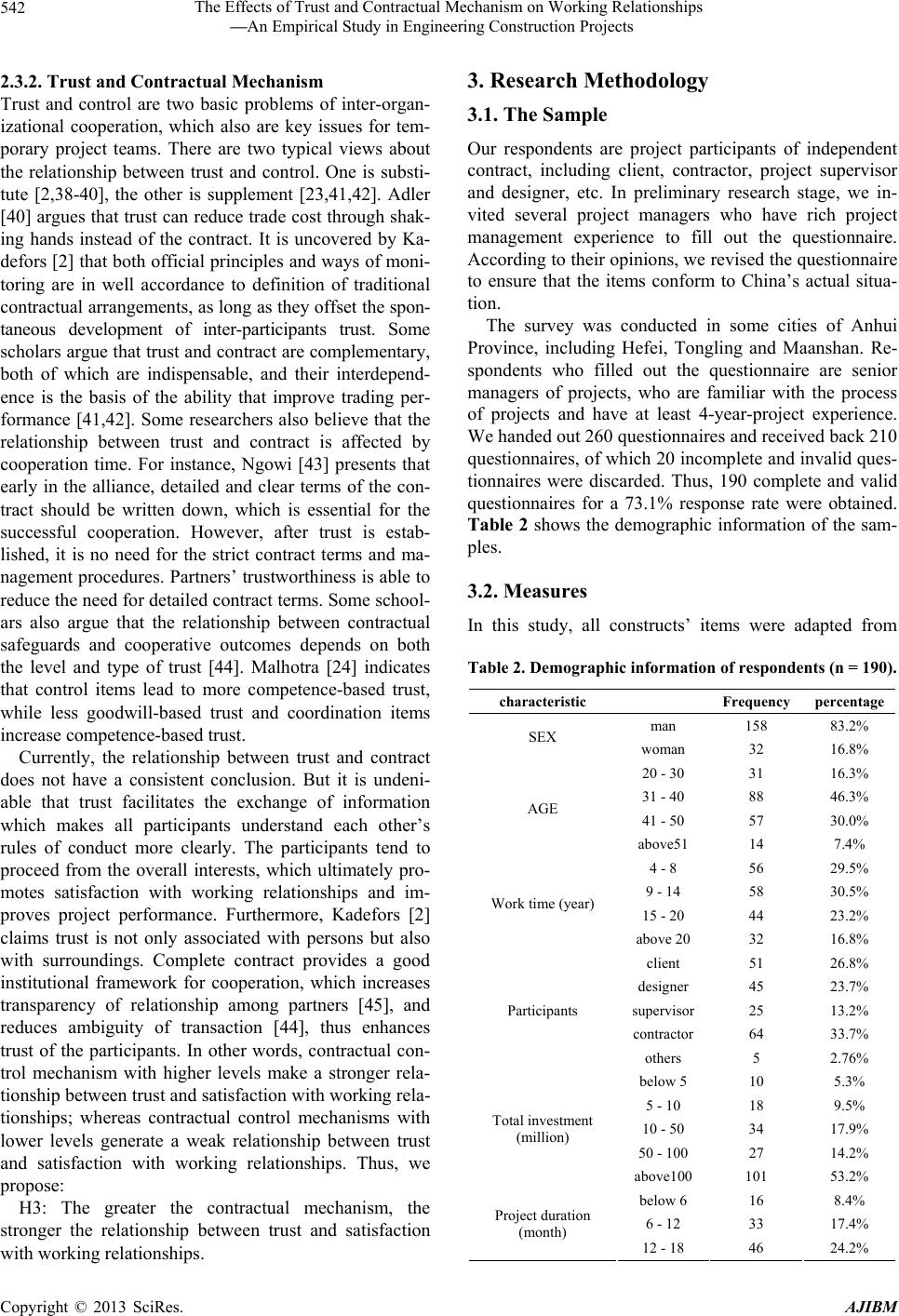

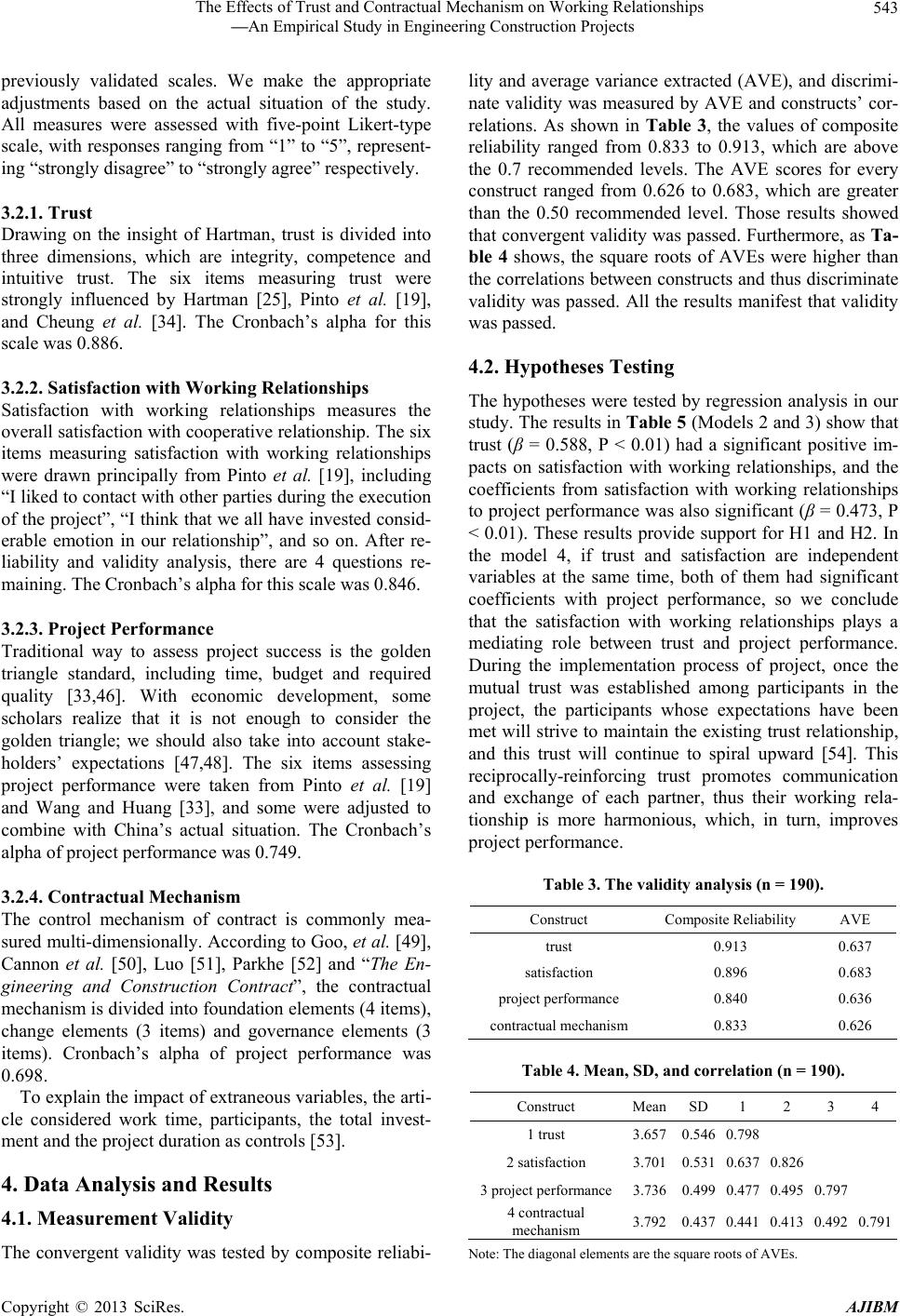

American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 2013, 3, 539-548 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2013.36062 Published Online October 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajibm) 239 The Effects of Trust and Contractual Mechanism on Working Relationships—An Empirical Study in Engineering Construction Projects Shuping Guo1, Ping Lu1, Yinqiu Song 2 1School of Management, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China; 2School of Management, Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China. Email: gsp725@mail.ustc.edu.cn Received August 2nd, 2013; revised September 2nd, 2013; accepted September 10th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Shuping Guo et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Inefficiency is usually one of the perceived ills within the construction projects and relationships among participants needing improvement. With the rising trend of partnerships in engineering construction projects, trust as an essential element in partnerships has become of increasing concern too. A growing stream of study has discussed the importance of trust in promoting interpersonal relationships among project participants. And formal contract has been closely watched which can mitigate exchange hazards. However, the relation between trust and contract is controversial. Based on cross-sectional survey data, regression analysis was used to test the impact of trust on satisfaction with working rela- tionships and project performance in engineering construction projects in China. Likewise, the moderating effect of contractual mechanism on the relationship between trust and working relationships is explored. The results show that working relationships are positively associated with trust and satisfying working relationships have significant impact on project performance. The empirical findings also support the moderating effect of contractual mechanism. The conclusions enrich the research of working relationship, and provide some practical implications for enterprises. Keywords: Trust; Contractual Mechanism; Working Relationships; Project Performance 1. Introduction Fragmented is a typical nature of engineering construc- tion projects [1]. The enforcement process of a project involves a plurality of different organizations with dif- ferent goals, cultures, and professional skills; therefore, in order to improve project performance, the question of how to promote cooperation among participants is a common problem for researchers and practitioners of project management. Further study shows that, trust as a unique, valuable and key resource [2] is an extremely important tool to obtain competitive advantages, and build sound coopera- tive relationships which, in turn improve project success. Based on relational exchange theory (RET), trust among participants can develop an effective coordination mechanism and plays an important role in preventing opportunism, reducing transaction costs, simplifying de- cision making and promoting the structure of the coop- eration stable [3]. As we known, Guanxi is a pervasive phenomenon in China, which is a direct outcome of the traditional culture value [4-6] and is viewed as a trust- building system [7]. Winch [8] notes that the project is regarded as a tem- porary coalition, which is simply based on the contract. In the construction field, most projects invite bidding; project participants often lack prior cooperation experi- ence [9]. Furthermore, Nguyen et al. [3] point out that large construction projects are inherently complex and dynamic. The problems which are urgently solved de- pend on whether the trust built up in such an environ- ment can significantly improve collaborators’ satisfaction with working relationships and how contractual mecha- nism affects trust. There are few empirical studies concerning relation- ships based on trust, working relationships, project per- formance and contractual mechanism in the context of engineering construction projects, much less in China. Therefore, using empirical research, this body of article addresses the following research questions: 1) whether the satisfaction with working relationships is associated Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  The Effects of Trust and Contractual Mechanism on Working Relationships —An Empirical Study in Engineering Construction Projects 540 with trust, which, in turn boosts project performance; and 2) Is the effect of trust on satisfaction with working rela- tionships moderated by contractual mechanism. Here, Figure 1 was used to illustrate the conceptual frame- work. 2. Literature Review and Hypotheses 2.1. Trust Economists tend to think that reputation or trust is the most important moral basis for running a good market. Maurer [9] suggests that trust is a complex and multifac- eted concept which has captivated scholars from different fields. Research on trust involves the fields of psychol- ogy, sociology, economics and management science, etc (e.g., [10-14]) and generally, trust plays a positive role. The document of each area has approached the issue with its own filters [15]. At the macro-level, sociologists and economists emphasize on the structural characteristics of the trust, and explore the important role of trust in pro- moting economic development and social progress [10,13]. At the micro-level, psychologists focus on the personality characteristics of trust, and management sci- entists pay more attention to competitiveness and opera- tional efficiency [11,12]. The concept of trust has a great variety of forms be- cause of the multidisciplinary research on the nature of trust. Rousseau et al. [16] define “trust is a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or be- havior of another”. Gambetta [17] proposes when you trust a person, you believe that he/she is not likely to do something that is damaging to you, even though he/she has the chance. Bromily and Cummings [18] deem trust is an expectation that individuals or group will be truthful in negotiations, making great efforts to complete assign- ment even there is an opportunity to take advantage of. To date, trust has not a precise definition, so some schol- ars avoid talking about it [19]. However, this does not prevent us from understanding the nature of trust, be- cause different concepts explain the same organizational issues [20]. For the assessment of trust, scholars often choose a multi-dimensional measure. McAllister [21] considers that trust encompasses cognition-based trust and affect- based trust. The former is rooted in individual confidence about peer reliability and dependability; the latter is rooted in reciprocated interpersonal care. Nooteboom [22] notes that trust is divided into goodwill trust and compe- tence trust. Goodwill trust focuses on the other party’s intention to perform in a trust-worthy manner, while competence trust focuses on the other party’s ability to complete assigned tasks. Wicks et al. [23] argue that trust contains three levels: high, moderate and low. Rousseau et al. [16] raise three kinds of trust: calculus-based trust, relational trust and institution-based trust. Later scholars, for example, Kadefors [2], Malhotra [24] have adopted Rousseau’s division. Hartman [25] suggests that trust includes integrity trust, competence trust, and intuitive trust in project setting. Integrity trust is based on the un- derstanding of ethical trust of the other party that will care another party’s benefits; competence trust is based on the belief that the other party can perform the work required; and intuitive trust is upon the party’s emotion or prejudice that one can trust the other. Concrete details are summarized in Table 1. Considering the complexity, and the changing circum- stances [26], the dimensions of trust in construction may be different from the others. Thus, which dimensions shall we choose for project environment? Goodwill- based trust which is proposed by Nooteboom [22] is less suitable for projects in China, as many options are de- pendent on project bidding, especially low price bids. Pinto et al. [19] indicates that Hartman’s dimensions are more suitable for the project environment, because this dimensions were purposely operated to apply trust within a project setting. Our study also chose Hartman’s dimen- sions. 2.2. Contractual Control Mechanism Because of uncertainty, information asymmetry and op- portunism, the organization is always exposed to various risks [27]. In order to reduce risk, transaction cost theory indicates that we need to adopt the necessary control mechanisms [28]. Scholars often use control activities to address the problems caused by information asymmetry, Figure 1. Conceptual framework. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  The Effects of Trust and Contractual Mechanism on Working Relationships —An Empirical Study in Engineering Construction Projects 541 Table 1. Dimension of trust. Scholars Dimension and definition McAllister (1995) 1) Cognition-based trust—rooted in individual confidence about peer reliability and dependability 2) Affect-based trust—rooted in reciprocated interpersonal care Nooteboom (1996) 1) Goodwill trust—focus on the other party’s intention to perform in a trust-worthy manner 2) Competence trust—focus on the other party’s ability to finish assigned tasks Rousseau et al. (1998) 1) Calculus-based trust—motivated by self-interest or the existence of economic incentives for cooperation or contractual sanctions for breach of trust 2) Relational trust—derives from repeated interactions over time 3) Institution-based trust—refers to the role of legal institutions, teamwork cultural etc. in promoting trust Wicks, Berman and Jones (1999) 1) High trust—rely extensively on affect-based belief 2) Moderate trust—firms depend primarily on rational, prediction-based inducements to limit opportunism 3) Low trust—a relatively balanced reliance on affect-based belief in moral character and incentives to preclude opportunism Hartman (2002) 1) Integrity trust—the understanding of “ethical trust” of the other party that will care another party’s benefits 2) Competence trust—the belief that the other party can perform the work required 3) Intuitive trust—the party’s emotion or prejudice that one can trust the other and agent opportunism. Formal control methods contain regime, rules, formal contract, the formal standard and ex-post control, etc. Explicit contractual control is an important formal control mechanism for fragmented pro- ject [29]. Contractual control emphasizes on the applica- tion of formal and legally-binding agreements to regulate the relationships among participants in the transaction [30,31]. Construction project contracts make the rights, responsibilities and interests clear among stakeholders, which control and guarantee the enforcement of the whole project. A full equipped construction contract not only deter- mines the outcome of the project, but also details provi- sions of partners’ obligations and duty, which should include the procedures, rules and penalties for violations, and also contain the procedures and method to resolve claims and termination of agreement. In projects, the contract control contains schedule control, quality control, cost control, etc. Therefore, firms generally prefer arm’s- length contractual agreements to protect themselves from risks [32]. Yunnan Lubuge Hydroelectric project is a sign that the modern project management was first introduced into China. Lubuge Hydroelectric project was a great success and as a “the Lubuge Shock” promoted the establishment of CPMS (the Construction Project Management System) [33]. The modern project management adopts competi- tive bidding and normative project contract management. In China, the most significant is the enforcement of con- struction project contract in the evolution process of pro- ject management system. 2.3. Trust, Working Relationships, Project Performance and Contractual Mechanism 2.3.1. Trust, Working Relationsh ips and Pro je ct Performance The stakeholder theory has had a rapid development in recent years, thus the project goal is no longer simply to consider time, cost and quality. Wang and Huang [33] explain that project success criteria has been expanded, encompassing organizational objectives, stakeholders’ satisfaction, future potential to organization, etc. Satis- faction with relationships refers to itself qualitative, over- all satisfaction in cooperation, and the degree of pleasure to work together, which can reduce the friction and con- flicts among participants and improve project perform- ance. Project participants’ satisfaction with working rela- tionships includes customer loyalty, leadership and ef- fectiveness [34]. During the life of the project, there are many key factors affecting working relationships, and trust is one of the key factors [15]. Summarizing previous studies, we find that trust can significantly reduce the transaction costs of the partners [35], which reduce the search for trading, negotiation, contracting and compliance costs. Schurr and Ozanne [36] find trust is central to the process of achieving coopera- tive problem solving and constructive dialogue. Trust can facilitate communication, information sharing, reduce asymmetric information among organizations and im- prove individual working satisfaction, thereby improve the performance of individuals and organizations [37]. Therefore, trust as informal control mechanism can im- prove the satisfaction with working relationships and positively influence the final project deliverables. Pinto et al. [19] argues that when trust levels are low, the working relationship is likely at risk and conflicts may appear. When working relationships are under an un- healthy state, it is obviously that the likelihood of project success decreases. According to above analysis, we pro- pose: H1: Higher levels of trust will lead to higher levels of satisfaction with working relationships among project participants. H2: Higher levels of satisfaction with working rela- tionships will lead to higher levels of project perform- ance. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  The Effects of Trust and Contractual Mechanism on Working Relationships —An Empirical Study in Engineering Construction Projects 542 2.3.2. Trust and Contractual Mechanism Trust and control are two basic problems of inter-organ- izational cooperation, which also are key issues for tem- porary project teams. There are two typical views about the relationship between trust and control. One is substi- tute [2,38-40], the other is supplement [23,41,42]. Adler [40] argues that trust can reduce trade cost through shak- ing hands instead of the contract. It is uncovered by Ka- defors [2] that both official principles and ways of moni- toring are in well accordance to definition of traditional contractual arrangements, as long as they offset the spon- taneous development of inter-participants trust. Some scholars argue that trust and contract are complementary, both of which are indispensable, and their interdepend- ence is the basis of the ability that improve trading per- formance [41,42]. Some researchers also believe that the relationship between trust and contract is affected by cooperation time. For instance, Ngowi [43] presents that early in the alliance, detailed and clear terms of the con- tract should be written down, which is essential for the successful cooperation. However, after trust is estab- lished, it is no need for the strict contract terms and ma- nagement procedures. Partners’ trustworthiness is able to reduce the need for detailed contract terms. Some school- ars also argue that the relationship between contractual safeguards and cooperative outcomes depends on both the level and type of trust [44]. Malhotra [24] indicates that control items lead to more competence-based trust, while less goodwill-based trust and coordination items increase competence-based trust. Currently, the relationship between trust and contract does not have a consistent conclusion. But it is undeni- able that trust facilitates the exchange of information which makes all participants understand each other’s rules of conduct more clearly. The participants tend to proceed from the overall interests, which ultimately pro- motes satisfaction with working relationships and im- proves project performance. Furthermore, Kadefors [2] claims trust is not only associated with persons but also with surroundings. Complete contract provides a good institutional framework for cooperation, which increases transparency of relationship among partners [45], and reduces ambiguity of transaction [44], thus enhances trust of the participants. In other words, contractual con- trol mechanism with higher levels make a stronger rela- tionship between trust and satisfaction with working rela- tionships; whereas contractual control mechanisms with lower levels generate a weak relationship between trust and satisfaction with working relationships. Thus, we propose: H3: The greater the contractual mechanism, the stronger the relationship between trust and satisfaction with working relationships. 3. Research Methodology 3.1. The Sample Our respondents are project participants of independent contract, including client, contractor, project supervisor and designer, etc. In preliminary research stage, we in- vited several project managers who have rich project management experience to fill out the questionnaire. According to their opinions, we revised the questionnaire to ensure that the items conform to China’s actual situa- tion. The survey was conducted in some cities of Anhui Province, including Hefei, Tongling and Maanshan. Re- spondents who filled out the questionnaire are senior managers of projects, who are familiar with the process of projects and have at least 4-year-project experience. We handed out 260 questionnaires and received back 210 questionnaires, of which 20 incomplete and invalid ques- tionnaires were discarded. Thus, 190 complete and valid questionnaires for a 73.1% response rate were obtained. Table 2 shows the demographic information of the sam- ples. 3.2. Measures In this study, all constructs’ items were adapted from Table 2. Demographic information of respondents (n = 190). characteristic Frequency percentage man 158 83.2% SEX woman 32 16.8% 20 - 30 31 16.3% 31 - 40 88 46.3% 41 - 50 57 30.0% AGE above51 14 7.4% 4 - 8 56 29.5% 9 - 14 58 30.5% 15 - 20 44 23.2% Work time (year) above 20 32 16.8% client 51 26.8% designer 45 23.7% supervisor 25 13.2% contractor 64 33.7% Participants others 5 2.76% below 5 10 5.3% 5 - 10 18 9.5% 10 - 50 34 17.9% 50 - 100 27 14.2% Total investment (million) above100 101 53.2% below 6 16 8.4% 6 - 12 33 17.4% Project duration (month) 12 - 18 46 24.2% Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  The Effects of Trust and Contractual Mechanism on Working Relationships —An Empirical Study in Engineering Construction Projects 543 previously validated scales. We make the appropriate adjustments based on the actual situation of the study. All measures were assessed with five-point Likert-type scale, with responses ranging from “1” to “5”, represent- ing “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” respectively. 3.2.1. Trust Drawing on the insight of Hartman, trust is divided into three dimensions, which are integrity, competence and intuitive trust. The six items measuring trust were strongly influenced by Hartman [25], Pinto et al. [19], and Cheung et al. [34]. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.886. 3.2.2. Satisfaction with Working Relationships Satisfaction with working relationships measures the overall satisfaction with cooperative relationship. The six items measuring satisfaction with working relationships were drawn principally from Pinto et al. [19], including “I liked to contact with other parties during the execution of the project”, “I think that we all have invested consid- erable emotion in our relationship”, and so on. After re- liability and validity analysis, there are 4 questions re- maining. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.846. 3.2.3. Project Performance Traditional way to assess project success is the golden triangle standard, including time, budget and required quality [33,46]. With economic development, some scholars realize that it is not enough to consider the golden triangle; we should also take into account stake- holders’ expectations [47,48]. The six items assessing project performance were taken from Pinto et al. [19] and Wang and Huang [33], and some were adjusted to combine with China’s actual situation. The Cronbach’s alpha of project performance was 0.749. 3.2.4. Contrac tual Mechanism The control mechanism of contract is commonly mea- sured multi-dimensionally. According to Goo, et al. [49], Cannon et al. [50], Luo [51], Parkhe [52] and “The En- gineering and Construction Contract”, the contractual mechanism is divided into foundation elements (4 items), change elements (3 items) and governance elements (3 items). Cronbach’s alpha of project performance was 0.698. To explain the impact of extraneous variables, the arti- cle considered work time, participants, the total invest- ment and the project duration as controls [53]. 4. Data Analysis and Results 4.1. Measurement Validity The convergent validity was tested by composite reliabi- lity and average variance extracted (AVE), and discrimi- nate validity was measured by AVE and constructs’ cor- relations. As shown in Table 3, the values of composite reliability ranged from 0.833 to 0.913, which are above the 0.7 recommended levels. The AVE scores for every construct ranged from 0.626 to 0.683, which are greater than the 0.50 recommended level. Those results showed that convergent validity was passed. Furthermore, as Ta- ble 4 shows, the square roots of AVEs were higher than the correlations between constructs and thus discriminate validity was passed. All the results manifest that validity was passed. 4.2. Hypotheses Testing The hypotheses were tested by regression analysis in our study. The results in Ta ble 5 (Models 2 and 3) show that trust (β = 0.588, P < 0.01) had a significant positive im- pacts on satisfaction with working relationships, and the coefficients from satisfaction with working relationships to project performance was also significant (β = 0.473, P < 0.01). These results provide support for H1 and H2. In the model 4, if trust and satisfaction are independent variables at the same time, both of them had significant coefficients with project performance, so we conclude that the satisfaction with working relationships plays a mediating role between trust and project performance. During the implementation process of project, once the mutual trust was established among participants in the project, the participants whose expectations have been met will strive to maintain the existing trust relationship, and this trust will continue to spiral upward [54]. This reciprocally-reinforcing trust promotes communication and exchange of each partner, thus their working rela- tionship is more harmonious, which, in turn, improves project performance. Table 3. The validity analysis (n = 190). Construct Composite Reliability AVE trust 0.913 0.637 satisfaction 0.896 0.683 project performance 0.840 0.636 contractual mechanism 0.833 0.626 Table 4. Mean, SD, and correlation (n = 190). Construct MeanSD 1 2 3 4 1 trust 3.6570.546 0.798 2 satisfaction 3.7010.531 0.637 0.826 3 project performance3.7360.499 0.477 0.495 0.797 4 contractual mechanism 3.7920.437 0.441 0.413 0.4920.791 Note: The diagonal elements are the square roots of AVEs. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  The Effects of Trust and Contractual Mechanism on Working Relationships —An Empirical Study in Engineering Construction Projects Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM 544 Table 5. Regressions analysis (n = 190). Variable Model 1Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6 Control variables work time −0.013 −0.053 0.131 0.105 −0.048 −0.052 participants −0.027 −0.020 −0.003 −0.004 −0.006 −0.008 total investment −0.151 −0.086 0.034 0.041 −0.145 −0.159* project duration 0.274 0.162* −0.153 −0.162 0.215 0.222** Independent variables trust 0.588** 0.347** 0.469** 0.424** satisfaction 0.473** 0.265** contractual mechanism (cm) 0.248** 0.269** trust *cm 0.124* F 2.033 22.503** 10.995** 13.453** 22.607** 20.386** R 2 0.042 0.379 0.230 0.306 0.426 0.439 Adjusted R2 0.021 0.363 0.209 0.283 0.407 0.418 ΔR2 0.384** 0.014* Note: **P < 0.01 (2-tailed), *P < 0.05 (2-tailed);In Model 1, Model 2, Model 5 and Model 6, dependent variable was satisfaction with working relationships; in Model 3 and Model 4, dependent variable was project performance. The regression analysis also shows that project dura- tion has a significant positive impact on the satisfaction with working relationships (Model 2). Generally, project participants are simply linked by the contract, so long project duration means the participants have enough time to understand each other, and the working relationships among participants will be more harmonious with deeper understanding. The moderating effect of contractual mechanism on the relationship between trust and satisfaction with working relationships was tested by hierarchical regres- sion analysis. In order to minimize the possible presence of multicollinearity, the independent and moderator variables were mean-centered in the study [55]. In Model 6, the product term of trust and contractual mechanism had a significant positive impact on satisfaction with working relationships (β = 0.124, P < 0.05, F = 20.386**). To research the moderating effect fully, the study com- pared the impact of trust on satisfaction with working relationships at low and high levels of the contractual mechanism [55]. In Figure 2, the horizontal axis repre- sents the levels of trust; the vertical axis represents the levels of satisfaction with working relationships; blue line represents a high level of contractual mechanism, and red line represents a low level of contractual mecha- nism. We use a standard that uses mean to plus or minus one standard deviation to describe the high and low lev- els of contractual mechanism. The figure reveals that when the level of contractual mechanism is high, trust has a stronger positive effect on satisfaction with work- ing relationships than when the level is low. The regres- sion analysis and the figure both provide support for H3. 5. Discussion This study examines how trust affects working relation- ships, and how such relationship is moderated by con- tractual mechanism in China’s engineering construction projects. Our findings are as followings: First, trust can promote satisfaction with working rela- tionships, which in turn improves project performance. Trust in construction projects has its features, that is not based on familiarity, similarity, future necessity and or- ganizational security [56], so the role of trust is some- times perceived controversial. The current study provides evidence that trust in engineering construction industry can positively affect working relationships and, then, boost project performance, which corroborate the general positive conclusions (e.g., social exchange theory and relational capital theory). Trust encourages well interac- tion among the participants [32], which enables them to share information, exchange knowledge, solve conflicts and reduce the fear of opportunism. Thus, trust plays an important role in building a benign business relationship [57] and this sound working relationship is critical to the project success. Although the participants involved in construction projects have come to understand the importance of trust, during the actual enforcement of the project, the partici- pants don’t devote sufficient time, energy, and resources to cultivate trust. The conclusions of this study will con- tribute to the project participants’ attention to trust-buil- ding. The project is a one-off, but cooperative relation- ship can be repeated. Inter-organizational activities are typically embedded in social network and if one party who has a reputation for untrustworthy will be punished  The Effects of Trust and Contractual Mechanism on Working Relationships —An Empirical Study in Engineering Construction Projects 545 Figure 2. The moderating effect. in the broader network [41]. Therefore, in engineering construction industry, building corporate reputation mechanism can avoid partners’ opportunistic behavior and promote the long-term cooperative relation. Second, the greater the contractual mechanism, the stronger the relationship between trust and satisfaction with working relationships. The result indicates that con- tractual mechanism can positively moderate the relation- ship between trust and working relationships. Under the same level of trust, if contractual control mechanism is more perfect, the impact of trust on working relationships will be more effective. As Li et al. [29] suggested a well-designed contract can offer a legal framework, and this framework strengthen the role of trust. The tradi- tional view is that detailed contract may signify distrust so managers generally emphasize one of them, but the study shows that the two are mutually affected. This re- sult is partly consistent with the Poppo and Zenger [41] finding that relational governance and contracts function are complements. In the actual enforcement of the project, trust should be combined with contractual mechanism to improve participants’ satisfaction, which furthermore promotes higher project performance. In China, the low trust phenomenon is widespread, and trust has two obvious flaws: one is non-obligatory and the other tends to guidance rather than supervision. For- mal contracts for the alliance provide a cooperation framework, which addresses the most critical issues of cooperation in basic rights and obligations, the distribu- tion of benefits as well as conflict resolution. As such if the provisions are more detailed, the alliance will operate more smoothly, and the cooperation expectations of other participants can be higher. Mayer and Argyres [58] con- ducted a detailed case study and argue that formal con- tract can promote cooperation expectations, resulting in a commitment to the relationship, such that detailed con- tracts help enhance mutual trust. Under contract safe- guard, trust can operate more effectively. But everything has an optimum degree, and in fact, paying excessive attention to formal and detailed contract may bring a se- ries of defects, thereby breaking the rules of relations and development of the trust relationship [41]. According to the actual situation of the local and the project, we need to develop a reasonable control level of contract to en- able trust to be of maximum effectiveness; after all, too complex contracts are too costly to craft and enforce [41]. Meanwhile, overreliance may be harmful, such as the overburdening of corporate obligations, collective biases, etc [6]. Jeffries and Reed [59] also find that it is not a good way to develop too much or too little trust. We should promote a check-and-balance system to ensure project’s success. 6. Limitations and Future Research As with any research, there are several limitations in the current study. First, this study only explores the rele- vance of trust for working relationships and contractual mechanism, which has not examined the antecedents of trust in project settings. The engineering construction project has its unique environment; therefore seeking antecedents of trust will have certain practical signifi- cance. Second, the research was conducted only in Anhui. This may limit the generalization of the results, because broader districts and their legal systems may alter the effectiveness of trust and contractual mechanism. Third, this cross-sectional data design obviously limits our abil- ity to fully test the nature of relationships. So subsequent research should undertake a longitudinal design, which is more convincing. 7. Conclusion With survey data collected from engineering construction projects in China, this paper has explored the positive effects of trust and contractual mechanism on project performance. Trust is pivotal in projects as a means to promote good working relationships and project success. Trust can be considered as the glue among project participants through boosting cooperation. Further, the moderating effect of contractual mechanism reminds managers that trust will be more effective when com- bined with contractual mechanism. Overall, the results of this article extend existing research on working relation- ship and provide some guidance for practitioners. REFERENCES [1] P. Mitropoulos and C. Tatum, “Forces driving adoption of new information technologies,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 126, No. 5, 2000, pp. 340-348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2000)126:5( Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  The Effects of Trust and Contractual Mechanism on Working Relationships —An Empirical Study in Engineering Construction Projects 546 340) [2] A. Kadefors, “Trust in Project Relationships—Inside the Black Box,” International Journal of Project Manage- ment, Vol. 22, No. 3, 2004, pp. 175-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(03)00031-0 [3] L. D. Nguyen, S. O. Ogunlana and D. T. X. Lan, “A Study on Project Success Factors in Large Construction Projects in Vietnam,” Engineering, Construction and Ar- chitectural Management, Vol. 11, No. 6, 2004, pp. 404- 413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09699980410570166 [4] K. Hwang, “Face and Favor: The Chinese Power Game,” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 92, No. 4, 1987, pp. 944-974. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/228588 [5] K. R. Xin and J. L. Pearce, “Guanxi: Connections as Sub- stitutes for Formal Institutional Support,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 39, No. 6, 1996, pp. 1641- 1658. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/257072 [6] F. F. Gu, K. Hung and D. K. Tse, “When Does Guanxi Matter? Issues of Capitalization and Its Dark Sides,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 72, No. 4, 2008, pp. 12-28. [7] J. Wu and X. Chen, “Leaders’ Social Ties, Knowledge Acquisition Capability and Firm Competitive Advan- tage,” Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2012, pp. 331-350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10490-011-9278-0 [8] G. M. Winch, “The Construction Firm and the Construc- tion Project: A Transaction Cost Approach,” Construction Management and Economics, Vol. 7, No. 4, 1989, pp. 331-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01446198900000032 [9] I. Maurer, “How to Build Trust in Inter-Organizational Projects: The Impact of Project Staffing and Project Re- wards on the Formation of Trust, Knowledge Acquisition and Product Innovation,” International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 28, No. 7, 2010, pp. 629-637. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2009.11.006 [10] M. Granovetter, “Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness,” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 91, No. 3, 1985, pp. 481-510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/228311 [11] J. B. Barney and M. H. Hansen, “Trustworthiness as a Source of Competitive Advantage,” Strategic Manage- ment Journal, Vol. 15, No. S1, 1994, pp. 175-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150912 [12] R. C. Mayer, H. D. James and F. D. Schoorman, “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, 1995, pp. 709-734. [13] P. Bromiley and L. L. Cummings, “Transactions Costs in Organizations with Trust,” Research on Negotiation in Organizations Greenwich, Vol. 5, 1995, pp. 219-250. [14] S. Chow and R. Holden, “Toward an Understanding of loyalty: The Moderating Role of Trust,” Journal of Managerial Issues, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1997, pp. 275-298. [15] R. J. Lewicki and B. B. Bunker, “Developing and Main- taining Trust in Work Relationships,” In: R. M. Kramer and T. R. Tyler, Eds., Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research, Sage Publications, New York, 1996, pp. 114-139. [16] D. M. Rousseau, S. B. Sitkin, R. S. Burt and C. Camerer, “Not So Different After All: A Cross-Discipline View of Trust,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 23, No. 3, 1998, pp. 393-404. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1998.926617 [17] D. Gambetta, “Can We Trust Trust?” In: D. Gambetta, Ed., Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, Electronic Edition, University of Oxford, Oxford, pp. 213-237. [18] P. Bromily and L. L. Cummings, “Transacfion Costs in Organizations with trUst,” In: S. M. R. Center, Ed., Uni- versity of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 1992. [19] J. K. Pinto, D. P. Slevin and B. English, “Trust in Projects: An Empirical Assessment of Owner/Contractor Rela- tionships,” International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 27, No. 6, 2009, pp. 638-648. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.09.010 [20] G. A. Bigley and J. L. Pearce, “Straining for Shared Meaning in Organization Science: Problems of Trust and Distrust,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 23, No. 3, 1998, pp. 405-421. [21] D. McAllister, “Affect- and Cognition-Based Trust as Foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation in Organiza- tions,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 1, 1995, pp. 24-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/256727 [22] B. Nooteboom, “Trust, Opportunism and Governance: A Process and Control Model,” Organization Studies, Vol. 17, No. 6, 1996, pp. 985-1010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/017084069601700605 [23] A. C. Wicks, S. L. Berman and T. M. Jones, “The Struc- ture of Optimal Trust: Moral and Strategic Implications,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 24, No. 1, 1999, pp. 99-116. [24] D. Malhotra, “Trust and Collaboration in the Aftermath of Conflict: the Effect of Contract Structure,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 54, No. 5, 2011, pp. 981-998. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0683 [25] F. T. Hartman, “The Role of Trust in Project Manage- ment,” In: D. P. Slevin, D. I. Cleland and J. K. Pinto, editor, The Frontiers of Project Management Research, Project Management Institute, Newtown Square, 2002, pp. 225-235. [26] P. S. Wong and S. Cheung, “Trust in Construction Part- nering: Views from Parties of the Partnering Dance,” In- ternational Journal of Project Management, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2004, pp. 437-446. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2004.01.001 [27] A. Parkhe, “Understanding Trust in International Alli- ances,” Journal of World Business, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1998, pp. 219-240. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(99)80072-8 [28] O. E. Willaimson, “The Economic Institutions of Capital- ism,” Free Press, New York, 1985. [29] Y. Li, E. Xie, H. Teo and M. Peng, “Formal Control and Social Control in Domestic and International Buyer- Supplier Relationships,” Journal of Operations Manage- ment, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2010, pp. 333-344. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  The Effects of Trust and Contractual Mechanism on Working Relationships —An Empirical Study in Engineering Construction Projects 547 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.11.008 [30] R. J. Ferguson, M. Paulin and J. Bergeron, “Contractual Governance, Relational Governance, and the Performance of Interfirm Service Exchanges: The Influence of Bound- ary-Spanner Closeness,” Journal of the Academy of Mar- keting Science, Vol. 33, No. 2, 2005, pp. 217-234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0092070304270729 [31] R. F. Lusch and J. R. Brown, “Interdependency, Con- tracting, and Relational Behavior in Marketing Chan- nels,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60, No. 4, 1996, pp. 19- 38. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1251899 [32] Y. Lee and S. T. Cavusgil, “Enhancing Alliance Per- formance: The Effects of Contractual-Based versus Rela- tional-Based Governance,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 59, No. 8, 2006, pp. 896-905. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.03.003 [33] X. Wang and J. Huang, “The Relationships between Key Stakeholders' Project Performance and Project Success: Perceptions of Chinese Construction Supervising Engi- neers,” International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 24, No. 3, 2006, pp. 253-260. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2005.11.006 [34] S. Cheung, T. S. T. Ng, S. Wong and H. C. H. Suen, “Behavioral Aspects in Construction Partnering,” Inter- national Journal of Project Management, Vol. 21, No. 5, 2003, pp. 333-343. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00052-2 [35] A. Zaheer, B. McEvily and V. Perrone, “Does Trust Mat- ter? Exploring the Effects of Interorganizational and In- terpersonal Trust on Performance,” Organization Science, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1998, pp. 141-159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.9.2.141 [36] P. H. Schurr and J. L. Ozanne, “Influences on Exchange Processes: Buyers' Preconceptions of a Seller's Trustwor- thiness and Bargaining Toughness,” Joumal of Consumer Research, Vol. 11, No. 4, 1985, pp. 939-953. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/209028 [37] K. T. Dirks and D. L. Ferrin, “The Role of Trust in Or- ganizational Settings,” Organization Science, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2001, pp. 450-467. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.4.450.10640 [38] R. Gulati, “Does Familiarity Breed Trust? The Implica- tions of Repeated Ties for Contractual Choice in Alli- ances,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 1, 1995, pp. 85-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/256729 [39] S. Ghoshal and P. Moran, “Bad for Practice: A Critique of the Transaction Cost Theory,” The Academy of Man- agement Review, Vol. 21, No. 1, 1996, pp. 13-47. [40] P. Adler, “Market, Hierarchy, and Trust: The Knowledge Economy and the Future of Capitalism,” Organization Science, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2001, pp. 214-234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.2.215.10117 [41] L. Poppo and T. Zenger, “Do Formal Contracts and Rela- tional Governance Function as Substitutes or Comple- ments?” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 23, No. 8, 2002, pp. 707-725. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.249 [42] Y. Liu, Y. Luo and T. Liu, “Governing Buyer-Supplier Relationships through Transactional and Relational Me- chanisms: Evidence from China,” Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2009, pp. 294-309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2008.09.004 [43] A. B. Ngowi, “The Role of Trustworthiness in the Forma- tion and Governance of Construction Alliances,” Build and Environment, Vol. 42, No. 4, 2007, pp. 1828-1835. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2006.02.013 [44] S. S. Lui and H. Ngo, “The Role of Trust and Contractual Safeguards on Cooperation in Non-Equity Alliances,” Journal of Management, Vol. 30, No. 4, 2004, pp. 471- 485. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.02.002 [45] J. Reuer and A. Ariño, “Strategic Alliance Contracts: Dimensions and Determinants of Contractual Complex- ity,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 28, No. 3, 2007, pp. 313-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.581 [46] E. Westerveld, “The Project Excellence Model: Linking Success Criteria and Critical Success Factors,” Interna- tional Journal of Project Management, Vol. 21, No. 6, 2003, pp. 411-418. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00112-6 [47] K. Jugdev and R. MÜller, “A Retrospective Look at Our Evolving Understanding of Project Success,” Project Management Journal, Vol. 36, No. 4, 2005, pp. 19-31. [48] P. Nixon, M. Harrington and D. Parker, “Leadership Per- formance is Significant to Project Success or Failure: A Critical Analysis,” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, Vol. 61, No. 2, 2012, pp. 204-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17410401211194699 [49] J. Goo, R. Kishore, H. R. Rao and K. Nam, “The Role of Service Level Agreements in Relational Management of Information Technology Outsourcing: An Empirical Study,” Mis Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 1, 2009, pp. 119-145. [50] J. P. Cannon, R. S. Achrol and G. T. Gundlach, “Con- tracts, Norms, and Plural form Governance,” Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2000, pp. 180-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0092070300282001 [51] Y. Luo, “Contract, Cooperation, and Performance in In- ternational Joint Ventures,” Strategic Management Jour- nal, Vol. 23, No. 10, 2002, pp. 903-920. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.261 [52] A. Parkhe, “Messy Research, Methodological Predisposi- tion, and Theory Development in International Joint Ventures,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 18, No. 2, 1993, pp. 227-268. [53] K. Z. Zhou, D. K. Tse and J. J. Li, “Organizational Change in Emerging Economies: Drivers and Conse- quences,” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 37, No. 2, 2006, pp. 248-263. [54] J. R. John K. Butler, “Reciprocity of Trust between Pro- fessionals and Their Secretaries,” Psychological Reports, Vol. 53, No. 2, 1983, pp. 411-416. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1983.53.2.411 [55] L. S. Aiken and S. G. West, “Multiple Regression: Test- ing and Interpreting Interactions,” Sage Publications, New York, 1991. [56] R. Zolin, R. E. Levitt, R. Fruchter and P. J. Hinds, “Mod- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM  The Effects of Trust and Contractual Mechanism on Working Relationships —An Empirical Study in Engineering Construction Projects Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJIBM 548 eling & Monitoring Trust in Virtual A/E/C Teams, A Re- search Proposal,” CIFE Working Paper 62, Stanford University, 2000. [57] J. T. Karlsen, K. Graee and M. J. Massaoud, “Building Trust in Project-Stakeholder Relationships,” Baltic Jour- nal of Management, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2008, pp. 7-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17465260810844239 [58] K. J. Mayer and N. S. Argyres, “Learning to Contract: Evidence from the Personal Computer Industry,” Or- ganization Science, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2004, pp. 394-410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0074 [59] F. L. Jeffries and R. Reed, “Trust and Adaptation in Rela- tional Contracting,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 25, No. 4, 2000, pp. 873-882.

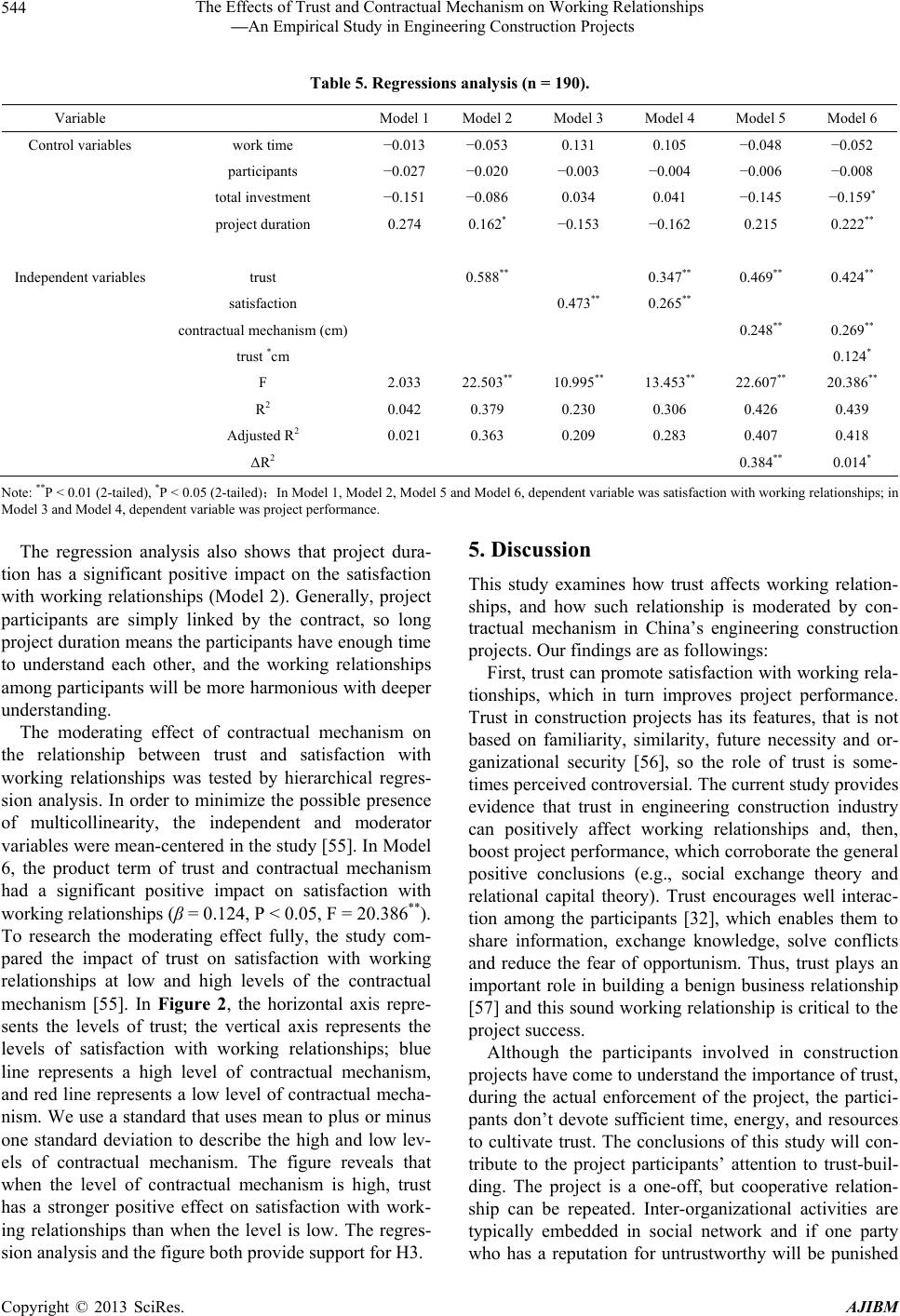

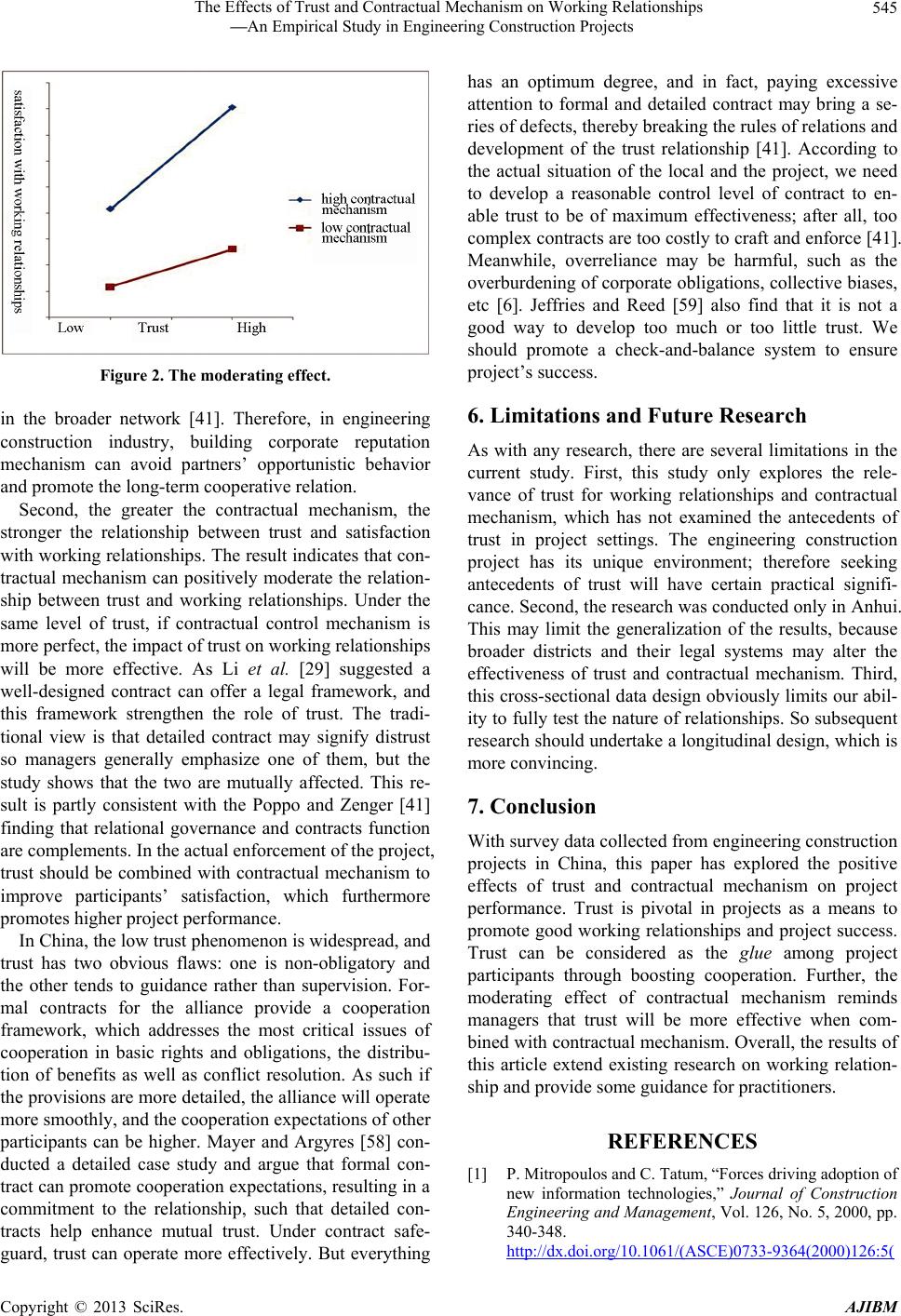

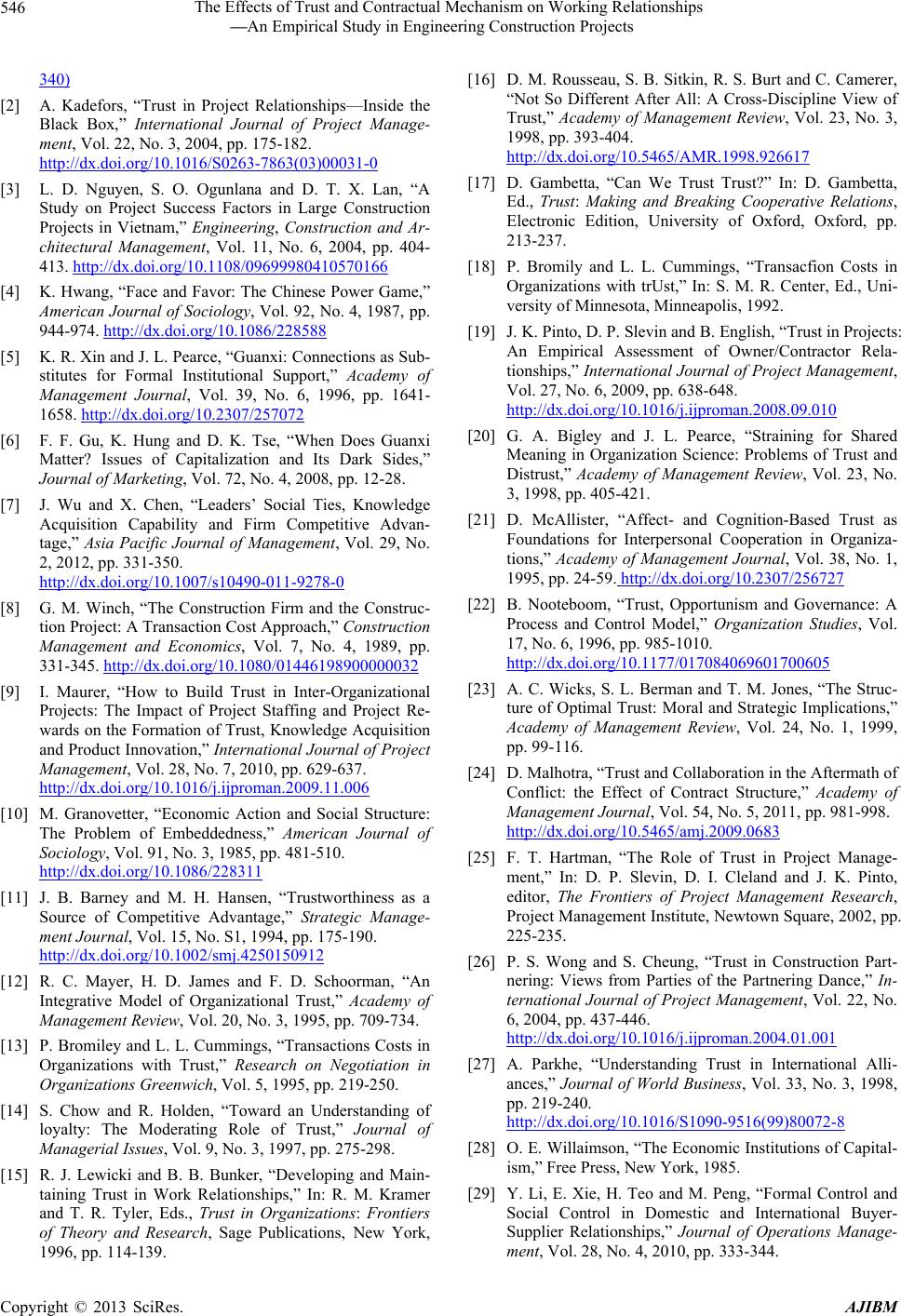

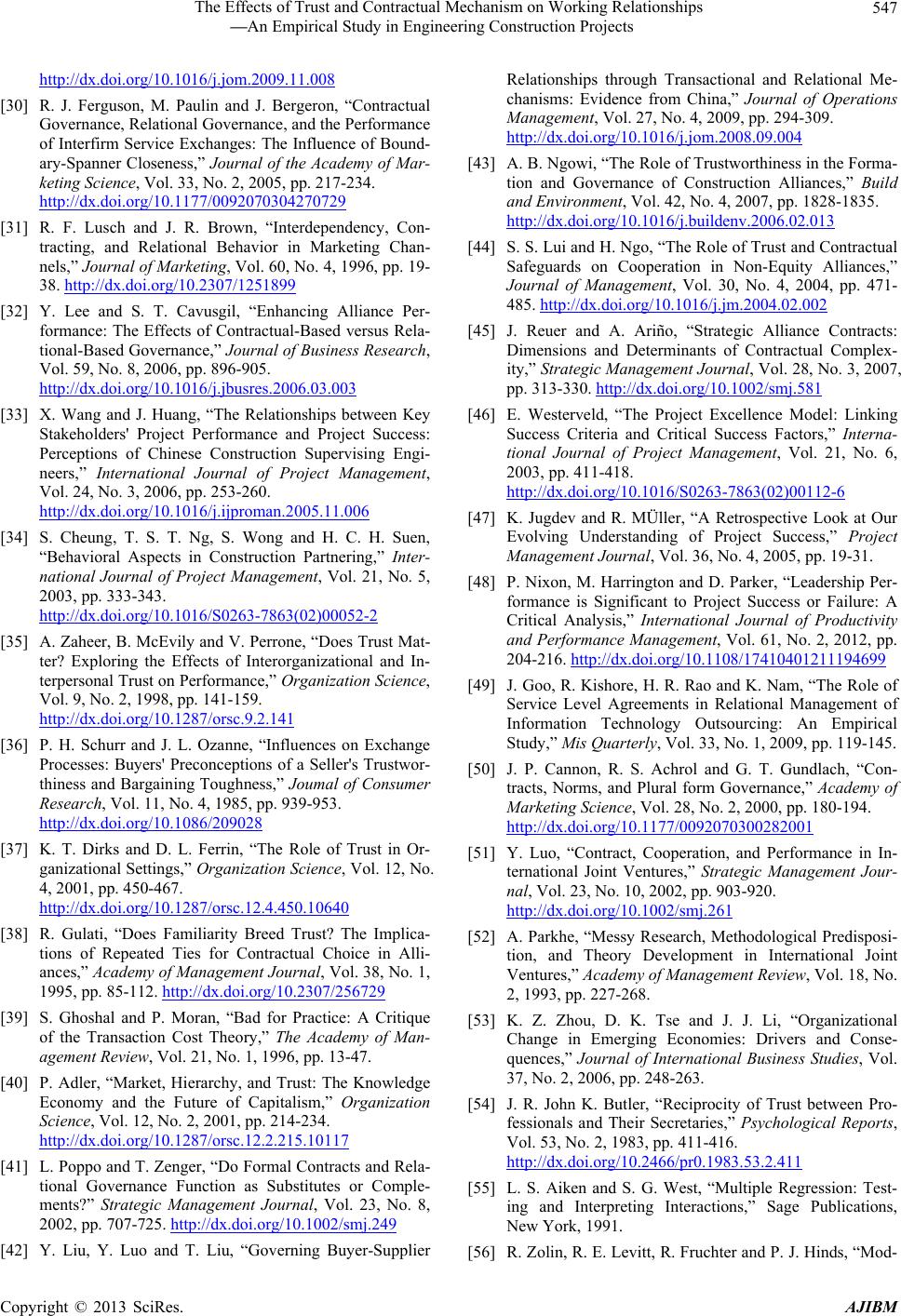

|