Vol.3, No.7, 429-440 (2013) Open Journal of Preventive Medicine http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2013.37058 Feasibility, effectiveness, and perceptions of an Internet- and incentive-based behavioral weight loss intervention for overweight and obese college freshmen: A mixed methods approach Brenda M. Davy1*, Kerry L. Potter2, Elizabeth A. Dennis Parker3, Samantha Harden1, Jennie L. Hill1, Tanya M. Halliday1, Paul A. Estabrooks1,4 1Department of Human Nutrition, Foods and Exercise, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, USA; *Corresponding Author: bdavy@vt.edu 2Bon Secours Health System, Porstmouth, USA 3Office of Minority Health & Health Disparities Research, Georgetown University, Washington DC, USA 4Department of Family and Community Medicine, Carilion Clinic, Roanoke, USA Received 10 August 2013; revised 15 September 2013; accepted 1 October 2013 Copyright © 2013 Brenda M. Davy et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Challenges inherent with the transition to col- lege are often accompanied by weight gain among college freshmen. Weight gain and dura- tion of obesity increase metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk in young adulthood, which supports the need for weight loss inter- ventions tailored to college students. The pur- pose of this investigation was to conduct a mixed methods pilot trial to determine the effi- cacy and acceptability of a semester long Inter- net- and incentive-based weight loss interven- tion for overweight/obese college freshmen. Par- ticipants (n = 27, aged >18 yrs, BMI >25) were randomly assigned to a 12-week social cognitive theory (SCT)-based intervention (Fit Freshmen [FF]) or a health information control group. The FF intervention also included modest financial incentives for weight loss. Primary outcomes included body weight/composition, dietary and physical activity (PA) behaviors, and psychoso- cial measures (i.e. self-efficacy, self-regulation) associated with diet, PA, and weight loss. Stu- dents in the FF intervention participated in focus groups to provide qualitative feedback on pro- gram structure and design. FF participants demonstrated significant reductions (all group differences p < 0.10) in body weight (−1.2 kg), fat mass (−0.6 kg), dietary energy (−673 kcal/d), fat (−37 g/d) and added sugar intake (−41 g/d), and increases in diet and PA-related self-regulatory skills at week 12 compared to control partici- pants (+1.0 kg, +1.1 kg, −334 kcal/d, −15 g/d, −13 g/d, respectively). No changes in PA were noted, but FF participants demonstrated increases in self-efficacy to overcome barriers to PA relative to control participants. Themes for content im- provement from focus groups included reducing email contact and increasing in-person interac- tions. Program characteristics that were posi- tively evaluated included incentives for weight loss and access to an onsite weigh station kiosk. Overall, this efficacious SCT Internet- and incen- tive-based weight loss intervention was well received and can be adapted for larger-scale use in the college population. Keywords: College Freshmen; Weight Gain; Social Cognitive Theory; Diet; Physical Activity 1. INTRODUCTION Weight gain is common in young adulthood (18 to 29 years) [1], with young adults in the United States gaining an average of 0.8 kilograms per year [2]. The college- aged population is susceptible to weight gain, experi- enceing a mean weight gain of 1.8 to 4 kilograms dur- ing their first year of college [2-5]. In addition, women living on campus, such as in a dormitory, gain weight 36 times faster compared to women of the same age living off-campus [6]. More importantly, metabolic syndrome risk is increased with weight gain in young adults, re- gardless of initial weight status [7]. Although research Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 430 has demonstrated that weight loss programs are effective in middle-aged adults [8], these programs may not trans- late to younger populations such as college students, who deal with typical barriers such as demands on time and financial issues, but also have additional challenges such as peer and academic pressure [9-11]. Yet, recent data from the CARDIA study [12] emphasize the need for interventions promoting the adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviors, including achievement and maintenance of healthy weight status through appropriate dietary intake and physical activity levels. Students’ positive health behaviors such as healthful eating and regular exercise often decline upon entering college [13-15]. Students report less physical activity in college as compared to high school, and increased con- sumption of energy-dense foods from fast food restau- rants and vending machines [13-15]. Further, weight loss programs targeting college students may not be success- ful when they target only physical activity or nutrition knowledge, do not include behavioral strategies, fail to address population specific barriers and motives and are not developed using established behavior change theories or models (e.g., the Social Cognitive Theory, Transtheo- retical Model) [15-18]. In addition, a qualitative analysis of college student preferences for different weight man- agement strategies included the provision of incentives for program participation [15]. To date, few studies in college students have included monetary incentives [19- 21] and these trials focus on weight-related health be- haviors and/or prevention of weight gain, and not on weight loss. While participant retention was high (likely because students were enrolled in an official university course for credit), intervention effectiveness was limited [19]. Social cognitive factors such as goal setting, plan- ning, self-monitoring, and self-efficacy also play a sig- nificant role in preventing weight gain in college stu- dents and could be incorporated into university-based health promotion programs [18,19,22,23]. Additionally, behavioral skills such as planning and tracking are asso- ciated with lower energy intake as well as increased fruit and vegetable consumption [15]. Unfortunately, college students rarely report using dietary strategies to regulate and track food intake, and only occasionally use them to incorporate more fruit and vegetables into their diets [15]. Prior work in non-overweight college students found that frequent, required online tracking of diet and physical activity behaviors was not rated favorably [19]. Although a social cognitive theory (SCT)-based intervention that provides training across these areas for college students may lead to changes in physical activity, healthful eating, and facilitate weight control, optimal self-monitoring fre- quency or mode is uncertain. Given the challenges related to the transition from high school to college, the channel of delivery of inter- ventions for college freshmen is an important considera- tion. The high-level of electronic communication and media use by the college-aged population [24,25] sug- gests that Internet-based weight loss programs [26,27], which may be less resource-intensive to deliver than tra- ditional in-person interventions, are a promising option. There is support for the positive effects of Internet-based programs that can be accessed through a personal com- puter or smartphone to address a wide range of health behaviors including weight loss and eating habits [18,21, 28,29]. In a university setting where Internet access via computers or mobile phones is ubiquitous, this delivery mechanism could increase the reach of tailored weight- loss programs [30]. However, the optimal way in which the Internet can be utilized for delivery of a weight loss and/or health-related behavior change intervention is yet to be determined [19,20]. Weight loss programs should include a combination of diet, physical activity and behavior-change strategies [31]. An efficient and effective interactive technology- based intervention could be used to access a large popu- lation and incorporate important weight loss program components. Our primary aim was to conduct a mixed methods pilot trial to determine if an Internet-and incen- tive-based weight loss program is feasible and effective for overweight and obese college freshmen, over a 12- week period. 2. Materials and Methods This pilot study was designed as a randomized con- trolled trial including both quantitative and qualitative data collection. A mixed methods approach was used to enhance and clarify quantitative findings [32]. Focus groups were conducted with participants in the interven- tion group to provide insight on the barriers and facilita- tors for adherence to the program as well as perceptions related to intervention features and structure, in order to inform the development of a future intervention in this target population. Participants were recruited from the 2009 Virginia Tech Freshmen class. The Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures and par- ticipants provided informed consent before enrollment. 2.1. Participants Eligible participants were first time college freshmen, at least 18 years of age, with a BMI> 25 kg/m2, who were not pregnant or pregnant in the last 12 months, and free from eating disorder symptoms, as assessed by the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26). Students with a score >20 on the EAT-26 were excluded from the study [33]. Additionally, students with a chronic disease such as diabetes, lung disease, heart disease or a thyroid disorder were excluded due to the potential risk in not meeting the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 431 needs of a special population through a generalized diet prescription and exercise regimen. 2.2. Data Collection An overview of the study design and participant recruitment/retention is provided in Figure 1. Briefly, two research assistants posted signs in student areas across the university and made announcements in 3 large undergraduate classes with a goal to recruit approxima- tely 40 participants during the first week of classes. Eli- gible participants completed a series of questionnaires and laboratory-based measurements including health history and health behavior surveys, body weight meas- urement, waist circumference and dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). Participants were paid $10 upon completion of baseline and 12-week (post interven- tion) measurements and $5 upon completion of monthly in-laboratory weigh-ins. Focus groups with randomly selected participants from the SCT-based intervention group (Fit Freshmen [FF]) were completed to determine program feasibility and acceptability following the 1st, 6th, and 12th week of the intervention. Participants were paid $20 upon completion of a focus group. 2.3. Quantitative Methodology At baseline and the conclusion of the study (week 12) the following laboratory measurements were completed by a research assistant blinded to participants’ group assignment. Height was measured in inches without shoes using a wall-mounted stadiometer. Body weight was assessed to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital scale calibrated for accuracy prior to each assessment period (Scale-Tronix model 5002, Wheaton, IL). Body mass index was calculated as weight(kg)/height(m)². Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.5cm using a Gulick tape measure (Gulick, Country Technology, Gays Mill, WI) at the level of the umbilicus. Body fat per- centage, absolute fat mass and fat-free mass were meas- ured using DEXA (GE Lunar Prodigy; GE Healthcare, Madison, WI). To assess habitual energy intake, participants were in- structed in proper methods to record their food intake and provided with two-dimensional food models to assist in accurate portion size determination. The food record covered four consecutive days, including three weekdays and one weekend day. Records were reviewed for accu- racy and completeness upon their return and analyzed using diet analysis software (NDS-R 4.05, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN). Habitual physical activity was measured using Godin’s Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire [34,35]. The ques- tionnaire assesses time and intensity of physical activity by evaluating weekly minutes and days spent doing mild, moderate and vigorous exercise as well as strength train- ing. The scales were scored based upon published proto- cols [35-37]. Psychosocial measures associated with physical ac- tivity, dietary intake and weight loss in a college-aged population were assessed using with a validated health beliefs survey [38]. This 102-item SCT survey consists of measures of self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and self-regulation for both physical activity and nutrition [39]. The survey assesses SCT determinants of eating behaviors and for physical activity behaviors using a 5 point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always) for self- regulatory skills and outcome expectations [38] and a scale from 0 to 100 (0 = Certain I cannot to 100 = Cer- tain I can) for self-efficacy regarding dietary and PA behaviors. The scales have adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.68 − 0.90 in this study) and are predict- tive of physical activity [3] and dietary intake [15,40]. 2.4. Qualitative Methodology The three focus groups were conducted using ran- domly selected participants (n = 4 − 5 per focus group; Figure 1, [41]) from the experimental condition to col- lect specific feedback on the structure and design of the intervention and to provide directions for future refine- ments. Students were ineligible to participate in future focus groups after participating in one in order to give each participant in the experimental condition an equal opportunity to share their perceptions on the content and structure of the program [42]. Each semi-structured focus group lasted one hour. We used a standard protocol of developing focus group questions [41]. We derived the questions to align with the study purpose (to create an effective weight loss program for overweight college freshmen) and allow for members of the target audience to provide iterative feedback on program content and structure to enhance the likelihood of having a gener- alizable effect and reaching a large proportion of the in- tended audience. One of the graduate research assistants (K.P.) led each focus group through a series of standard- ized semi-structured, open-ended questions. The ques- tions focused on the following areas: feasibility and ac- ceptability of the FF eating and exercise plan; percep- tions of overall intervention including barriers to and facilitators of program adherence; perceptions of daily e-mails and attitudes towards e-mail content. Two trained research assistance facilitated the focus groups. Qualitative data were verified by summarizing key points with the participants and asking if the sum- mary was accurate and inclusive of the discussion. Upon participant authorization, the sessions were recorded us- ing a digital voice recorder and written transcripts were generated using Transana 2.30 (Madison, Wisconsin). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 432 Data were transcribed, coded and interpreted using both inductive and deductive methods to allow for exploration and discovery of new themes and strategies for inter- venetions [43]. 2.5. Intervention Development and Delivery Both the intervention and control weight loss pro- grams were developed to help overweight college fresh- men lose weight. Both groups received identical health- related information (i.e., educational content) that in- cluded exercise and eating plans, strategies to maintain the plans, and expert advice on weight loss. In both pro- grams, nutrition information incorporated nutritional guidelines set by the United States Department of Agri- culture (USDA) 2005 Guidelines [44] as a foundation of the program and also included suggestions provided by the National Weight Control Registry such as eating smaller more frequent meals across the day (i.e., 5 to 6 rather than 3 meals a day) [45]. Participants were pro- vided with the tools to create a 12-week exercise pro- gram that could be executed in their dormitories or in the university fitness facility. To aid in retention efforts par- ticipants received $5 for completing a monthly weigh-in. Each program also encouraged participants to select a workout option that was reflective of their current health and fitness status. 2.6. Fit Freshmen Intervention Group Fit Freshmen (FF) participants received daily e-mail support, access to a comprehensive website with educa- tional and skill related information, and monthly mone- tary incentives for both weight loss from baseline and self-monitoring of nutrition, physical activity, and body weight. Body weight could be tracked weekly via weigh- ins on a weigh station located in an academic building on campus. The weigh-station was originally created to promote healthy lifestyles for employees in corporate companies (incentaHealth, LLC, Denver, CO). Weigh station data, which included body weight and a photo- graph of the participant, was uploaded to the intervention website so students could track their progress over the course of the program. The images were used to provide motivation for the participant over the course of the in- tervention. Additionally, the camera and weigh station were linked via a computer that provided a connection to the Internet for the two-way transmission of data to in- tervention staff (all data encrypted). Daily e-mails. Participants received daily e-mails to support increased physical activity and healthful eating. The content of the daily e-mails was targeted to a col- lege-aged population and explicitly included strategies to improve self-efficacy and self-regulation [15,16,46]. Each day of the week had a specific focus on issues that would be relevant to college students in order to sustain healthful weight habits and aligned with SCT constructs [47]. Additionally, there was a consistent SCT theme for each of the 12 weeks of the program, which included focusing on outcome expectations, developing self-effi- cacy through small successes, strategies to track physical activity and eating, ongoing goal setting, and relapse prevention strategies. Daily topics began with a success story (Sunday), ex- ercise opportunities (Monday), nutrition information (Tuesdays), barriers and strategies to overcome them (Wednesdays), ask the expert (Thursdays), portion size strategies (Fridays), and goals (Saturdays). Participants were also taught self-regulatory behaviors relevant to weight management through e-mails such as “Ask the Expert” focusing on knowledge of benefits and risks of different health behaviors. The weekly “Success Stories” of other college freshmen who had succeeded in losing weight emphasized observational learning and vicarious experiences modeled by relevant peers [46]. Barriers to adopting healthier lifestyle behaviors faced by young adults in an academic setting were targeted once a week in order to address reciprocal determinism between an individual, his/her behavior, and the environment. On days focusing on goals, short- and long-term goal setting were emphasized and aligned with outcome ex- pectations relevant to each participant [15]. Additionally, participants could access an online health coach with specific questions or issues. E-mails included sample menus stressing the importance of fruit and vegetable consumption and low-fat food options. The menus also included specific information from on campus dining halls to ensure it was relevant to the sample. While this intervention was completed before My Plate recommen- dations (www.choosemyplate.gov), a plate method was used to help students consider appropriate portion sizes. It was recommended that at each main meal, students should cover one quarter of their plate with a complex carbohydrate, one quarter with a serving of protein and the remainder with non-starchy vegetables. In addition, every Wednesday, nutrition e-mails addressed certain SCT variables addressing different dietary issues such as frequent self-monitoring of intake, methods to avoid overeating in buffet style student dining centers and emotional coping strategies other than eating when stressed. There were also links included throughout the weekly e-mails to Dining Services online nutrient infor- mation. Monetary Incentives. At the end of each month during the intervention period, participants who lost 1% - 5% of their initial body weight received $5, those that lost 5.1% - 10% received $10 and those that lost 10.1% and higher received $20. To enhance self-regulation, modest incen- tives were also provided for weekly completion of Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 433 weigh-ins and self-monitoring of physical activity and eating. Participants who lost weight each month and weighed in at least once a week for a month received an additional $5. Participants that completed weekly online self-monitoring for a month also received an additional $5. 2.7. Control Group The control group received two electronic newsletters, one at the start of the study and one six weeks after base- line. The newsletters highlighted messages about a healthy lifestyle similar to those messages highlighted in the intervention group. The key difference between the newsletters delivered to the control group and the daily e-mails delivered to the intervention group was the newsletters focused on general educational information that could be found from any reputable Internet health site, whereas the daily FF e-mails addressed SCT vari- ables and self-regulation related to eating and physical activity. The control group participants did not have ac- cess to the health coach or the modest monetary incen- tives for weight loss or tracking. 2.8. Data Analysis Quantitative statistical analysis was conducted using statistical analysis software (SPSS v.12.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Analyses included descrip- tive statistics (means, standard error, and frequencies) and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Multivariate, repeated measure analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using a two-group design assessed treatment effect (i.e. weight loss, percent body fat lost). Bivariate correlations were used to determine the relationships between changes in SCT variables, physical activity, dietary intake, and weight loss. Due to the sample size and pilot nature of this trial, we set an a priori level of significance at p < 0.10. Focus group transcripts were reduced to meaning units using both an inductive and deductive approach. We used a framework approach [43] using prior qualitative literature on this population to code deductively and then took an inductive approach solely from this qualitative data [43]. After the focus groups were transcribed, each investigator became familiar with the data by reading through the transcripts several times. Meaning units were organized into the themes associated with different components of the FF content and structure. Additionally, prior knowledge from qualitative data about barriers and motivators college students face when leading a healthy lifestyle was used [10,15,16]. To identify themes and patterns from focus group data, investigators developed classification codes during the analysis of data. These codes were obtained from the research questions used during the focus groups as well as keywords that con- stantly appeared in the text from conversations between participants during the focus groups. For example, the FF intervention revolved around a meal plan, exercise plan, self-monitoring and self-regulation skills through the use of a weigh-in station and regular journaling, as well as daily e-mails and modest incentives. Thus, codes were developed around these components of the intervention when analyzing the data from the focus groups. Every time words or phrases related to these concepts appeared in the text, sentences or paragraphs containing them were bracketed and the code written next to the bracket ac- cording to standard procedures [48]. In this way, during the first phase of qualitative analysis, text was organized based on the codes. In addition, codes were derived using the constant comparison method [43] where newly gath- ered data from the second and third focus group was compared with data from the first focus group and its coding in order to refine the development of new theo- retical categories. 3. RESULTS The sample population was ~18 years of age (age 18.5 ± 0.6 yrs) and predominantly white (83%) and female (76%). At baseline, the mean weight status of the sample classified as obese (BMI~31 kg/m2). No baseline group differences were detected. 3.1. Quantitative Findings Participants in the FF group demonstrated significant decreases in body weight, fat mass and BMI at 12 weeks when compared with the control group, whose weight had increased over the 3-month period (Table 1). How- ever, there were no group differences over time in body fat %, total lean body mass or waist circumference. Diet, physical activity, and SCT outcomes at baseline and at week 12 are presented in Table 1. At 12 weeks, FF participants reported consuming significantly less energy and fat (g and % of total energy) and more pro- tein (% of total energy) compared to control participants. The % of total energy from carbohydrates did not differ between groups at baseline or 12 weeks, but there was a significant group difference in reduction in added sugar (AS) intake in the FF group compared to control partici- pants. Importantly, this reduced level of AS consumption in FF participants is similar to that recommended by the American Heart Association (AHA; 25 to 37.5 grams/d or 100 - 150 kcals/d) [49]. Changes in physical activity were not significant by time or condition (Table 1). FF participants demonstrated increases in self-regulatory skills related to portion sizes, planning and tracking, fruits and vegetables and physical activity as compared to control participants. Self-efficacy to overcome barriers Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 434 Table 1. Body weight and composition, social cognitive theory (SCT) factors and self-reported dietary intake and physical activity in Fit Freshmen and Control group participants before and after a 12-week weight loss intervention. Control Group Fit Freshmen Group Between Group Comparisons Baseline (SD) Week 12 (SD) ∆ Wk 12 - Baseline Baseline (SD) Week 12 (SD) ∆ Wk 12 - Baseline p Body weight and composition Weight (kg) 87.5(4.9)88.5(5.0)1.0 93.1(5.1)91.9(5.1) −1.2 0.06** Fat Mass (kg) 38.0(4.6)39.1(4.8)1.1 42.9(4.8)42.3(5.0) −0.6 0.09** Lean Mass (kg) 50.5(3.5)50.4(3.4)−0.1 48.4(3.6)47.7(3.5) −0.7 0.51 Body Mass Index (kg/m2) 29.5(1.4)29.9(1.4)0.4 32.3(1.4)31.9(1.5) −0.4 0.06** Body Fat (%) 38.4(2.2)39.4(2.4)1.0 42.5(2.3)42.2(2.5) −0.3 0.15 Waist Circumference (cm) 95.6(3.8)96.8(3.8)1.2 105.2(3.9)104.4(4.0) −0.8 0.14 Dietary Intake Energy (kcal/d) 2170(154)1836(149)−334 2224(148)1551(143) −673 0.07** Fat (g/d) 88(8) 73(7) −15 90(7) 53(7) −37 0.02** Protein (g/d) 83(6) 70(7) −13* 84(6) 72(7) −12* 0.89 Carbohydrate (g/d) 265(20) 232(19)−33* 276(19)203(18) −73* 0.12 Alcohol (g/d) 0.08 (0.03)0.03(0.7)−0.05 0.08(0.03)0.98(0.69) 0.9 0.35 % Fat (% energy) 36(1) 36(2) 0 36(1) 30(2) −6 0.02** % Protein (% energy) 16(0.7) 15(0.7) −1 15(0.7) 18(0.7) 3 0.03** % Carbohydrate (% energy) 49(2) 50(2) 1 50(2) 53(2) 3 0.47 % Alcohol (% energy) 0.03(0.01)0.0(0.2)−0.03 0.02(0.01)0.26(0.19) 0.24 0.33 Added sugars (g/d) 76(10) 63(6) −13 80(9) 39(6) −41 0.04** Fiber intake (g/d) 16(1) 15(1) −1 15(1) 12(1) −3 0.26 Fiber intake per 1000 kcal (g/d) 7(0.7) 8(0.6) 1 7(0.6) 8(0.6) 1 0.99 Physic al Activit y (P A) Moderate PA (min/wk) 246(138)115(26)−131 71(144)111(27) 40 0.42 Vigorous PA (min/wk) 121(36) 163(48)42 88(38) 123(50) 35 0.89 Strength Training (min/wk) 68(32) 90(33) 22 35(33) 56(34) 21 0.98 SCT constructs: PA and Dietary Behavior scores Regulating Calories and Fat Self-Efficacy# 2.9(0.2) 3.5(0.2)0.6 2.7(0.2)4.0(0.2) 1.3 0.02** Planning and Tracking Self-Regulation# 2.2(0.1) 2.9(0.1)0.7 2.4(0.1)3.7(0.1) 1.3 <0.01** Regulating Fruits and Vegetables# 3.8(0.3) 3.6(0.2)−0.2 3.1(0.3)4.2(0.2) 1.1 <0.01** Self Regulation Keeping Track ## 83.1(4.6)80.3(4.1)−2.8 72.6(4.8)75.8(4.3) 3.2 0.38 Physical Activity Self Regulation# 3.0(0.2) 3.4(0.2)0.4 2.7(0.3)4.0(0.2) 1.3 <0.01** Self Regulatory Self-Efficacy for Fruits and Vegetables## 74.0(4.2) 76.3(4.1) 2.3 71.2(4.4)72.6(4.3) 1.4 0.87 Positive Outcome Expectancies for Fruits and Vegetables# 4.4(0.1) 4.5(0.1)0.1 4.5(0.2)4.6(0.1) 0.1 0.81 Negative Outcome Expectancies for Fruits and Vegetables# 2.5(0.2) 2.5(0.2)0.0 3.0(0.2)3.1(0.3) 0.1 0.42 Self-Efficacy to Integrate Physical Activity into Daily Life## 77.3(3.2)78.4(3.4) 1.1 71.2(3.5)81.5(3.7) 10.3 0.02** Self-Efficacy to Overcome Barriers to Physical Activity## 73.2(4.3) 70.2(4.1)−3.0 61.1(4.6)74.2(4.4) 13.1 0.01** Physical Activity Positive Outcome Expectancies# 4.1(0.1) 4.4(0.1)0.3 4.2(0.1)4.3(0.1) 0.1 0.83 Physical Activity Negative Outcome Expectancies# 2.4(0.2) 2.5(0.2)0.1 2.3(0.2)2.4(0.2) 0.1 0.92 *Significant time effect, p < 0.10. **Significant group x time effect, p < 0.10. #Scored on a scale of 1 to 5. ##Scored on a scale of 0 to 100.  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 435 to physical activity significantly increased after the 12-wks in FF participants, relative to control group par- ticipants. 3.2. Qualitative Findings All 13 FF participants attended one of the three semi-structured focus groups (Figure 1). Themes that emerged were similar across all three focus groups sug- gesting that saturation was reached. Findings are pre- sented in detail with selected illustrative quotes in Table 2. In general, participants felt that spreading their meals into smaller, more frequent meals across the day was not Individuals screened for eligibility (n = 77)Excluded (n = 42): BMI < 25 kg/m 4 (n = 33) EAT-26 score >20 (n = 6) Not current freshmen (n = 3) Eligible, but declined (n = 6) Initial Laboratory Tests Height, Weight, Waist Circumference, Body Compiosition, Food Records, Questuinnaires $10 Compensation * Randomized n = 29 Withdrew after randomization, but prior to intervention implementation (n = 2) FF Group (n = 1) Control Grou n = 1 Control (n = 14) Fit Freshmen (Intervention) n = 13 Weeks 1-4 Daily e-mail support and health-related information, access to study website for self-monitoring, access to weight-station for weekly weigh-ins. Weeks 1-4 healthy Lifestyle information Newsletter #1 Month 1 Weigh-In $5 Compensation * Month 2 Weigh-In $5 Compensation Weeks 6 healthy Lifestyle information Newsletter #2 Month 2 Weigh-In Monetary incentives provided for weight loss goals and self-monitoring $5 Compensation Month 1 Weigh-In Monetary incentives provided for weight loss goals and self-monitoring 5 Com ensation * Weeks 5 - 8 Daily e-mail support and health-related information, access to study website for self-monitoring, access to weigh-station for weekly weigh-ins Weeks 9 - 12 Daily e-mail support and health-related information, access to study website for self-monitoring, access to weigh-station for weekly weigh-ins FF Focus Group Following Week 1, n = 4 FF Focus Group Following Week 6, n = 4 FF Focus Group Following Week 12, n = 5 Post-Intervention Laboratory Tests Height, Weight, Waist Circumference, Body Composition, Food Records, Questionnaires $10 Compensation Included in analysis (n = 14) Post-Intervention Laboratory Tests Height, Weight, Waist Circumference, Body Composition, Food Records, Questionnaires Monetary incentives provided for Month 3 weight goals and self-monitoring $10 Compensation Included in anal sis n = 13 Figure 1. Overview of the Internet- and incentive-based weight loss intervention. *Compensation paid for completion of measurements and was not dependent upon meeting weight-loss goals. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 436 Table 2. Qualitative findings: Perceptions from Fit Freshmen participants of weight loss program components. Intervention Component Common Themes Illustrative Quote(s) Availability of healthy foods “During the snack times of the day I’m over on the academic side of campus and not close to anywhere where I can just grab a snack.” “I did not like it (recommended meal plan) because it would recommend things such as lightly grilled salmon and I have a campus meal plan!” Time Management and Frequency of Meals “You are so busy as a college kid, I think 6 small meals is a lot to ask.” Self-regulation “Just having to write it down all the time and knowing someone is going to look at it helps.” “It made me more aware of what to eat and what not to eat and how much. It really helped me focus on my portion (size) more than anything.” Detail of meal plan “I think it would be neat if meal plan could be taken to the next step to where the program had full meal suggestions like at D2 (dining hall).” Meal Plan Socializing around meals “I always eat with friends, so it makes it a little harder if you do have a little time [to go to the dining center] if you have no one to go with.” Time “If I have a test tomorrow, I try to make time for the gym, but I mean sometimes, it doesn’t happen.” Structure “I’ve actually been following the exercise program because I used to only do cardio. I always thought I had to do cardio every single day and so I actually try to stay on track when it says to run and when it says to lift weights.” Variety and Flexibility “Now I am on the home plan because, gyms and I don’t get along and I can do it by myself and I like it because it motivates me just to go do it because once I get this done, I’m done.” “The thing about the program is it gives us directions and you can do it at your own pace and in your own time.” Exercise Plan Social Support “I think it would be cool if on a weekly basis you could meet with a group and see how everyone is progressing. It’s kind of a support group.” “If it (group interaction) were to be consistent throughout the program, it could only help. It would only motivate you more because you would be like ‘Oh I have to go meet up and go workout’” Frequency of E-mails “I think the e-mails are too frequent. I think if it was just once per week, I think it would be more effective.” Daily E-mails E-mail Topics on Success, Specific Foods, and Portions “The success stories are motivating because you see somebody else that looks like you is doing the same thing you are and they are succeeding at it.” “I know the one e-mail that had the food suggestions was really good about actual places on campus to eat.” “There was one (e-mail) about looking at your plate in four sections… two vegetables and a protein and a starch or carb. That one really set a visual in my mind and when I eat now I always picture dividing my plate into four sections.” Monetary Incentives Format “The fact that I can get paid just to lose weight is priceless and I love that system” “I think it (money) helps a little bit. If you don’t feel like going across campus to weigh in on a Friday afternoon, I remind myself, ‘If I do this, I will get 5 dollars at the end.’” “If there was some type of competition between a group of 50 or smaller (participants), people would be more inclined to lose weight. Like the top weight loss for the week gets a gift card to Blockbuster or something or the top weight loss over the whole program gets a $25 gift certificate to some place. It’s just that people by nature are competitive and they want to do better than anyone else.” Weigh Station (Kiosk) Self-regulation and Tracking Progress “It [the kiosk] helps me keep track of what’s going on. So that’s a good thing to do.” “I like the pictures. I mean I hate looking at myself, but I know eventually that I will like them.” Online Journaling Self-regulation “I like to have the same questions to where one week I can look and be like “WOW” I really didn’t do well this week on this particular thing and then I can work to do better next week on that thing.” Format of Journals “I just feel like I go over it way too fast because it’s multiple choice.” feasible due to lack of time, money to buy healthy foods and accessibility of certain foods offered at campus din- ing halls. In addition, a barrier to adhering to 5 - 6 small meals a day was a lack of social support from friends and the difficulty of following the plan when friends were eating what they wanted during meal times. However, participants reported that tracking their daily energy in- take helped them to follow the recommended meal plan- and portion sizes accordingly and that the specificity of the meal plan helped to emphasize portion control skills. While significant changes in physical activity were not detected, participants expressed approval and likability Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 437 for the exercise component of the program. Most par- ticipants agreed that the exercise program offered a wide variety of options including gym and dorm options, and different types of activities/intensities, making it possible for many types of college students to enjoy. Participants only felt that lack of time when studying for tests was a barrier, and expressed a desire for a face-to-face social support system to encourage physical activity. Participants felt that the success stories were the most relevant e-mails to help college students develop behave- ioral strategies for maintaining a healthful weight. Viewing successful peers lose weight helped build con- fidence in the participants. Specific e-mails that focused on portion control and self-regulatory skills were also seen as a positive program component. Still, the majority of participants felt that daily e-mails, as college freshmen already on multiple e-mail listserves for other academic organizations, were overwhelming. Overall, participants found the small monetary incen- tives related to weight loss to be an attractive program component. Focus group members suggested that small financial incentives can be used as an external motivator when trying to lose weight and they did not feel that the incentives affected their internal motivation to participate in the program. Participants also indicated that tying the incentive to weighing in each week motivated them to complete that task. Participants reported that the weigh station (kiosk) scale was a helpful program feature, though one theme that was derived from the data included having the kiosk or kiosks more widely accessible across campus to en- hance access. Findings related to the weekly self-moni- toring journal were equivocal. Some participants felt that they were not reflective on their weight management habits due to the repetitiveness of the weekly questions. However, others saw the repetition in questions as a tool to track their weekly and monthly progress and to under- stand their barriers to maintaining a healthy weight. 4. DISCUSSION These findings indicate that the 12-week Internet- and incentive-based weight loss program was effective at promoting weight loss among overweight and obese col- lege freshmen. Significant reductions were also noted in total energy, fat and AS intake, as well as improvements in planning and tracking self-regulatory skills and self-efficacy to incorporate physical activity. The need for behavior-based interventions designed to lower die- tary intake of solid fats and AS, and improve energy balance, has been recently highlighted [50]. This issue may be particularly pressing in the college population as high sugar-sweetened beverage intake (the primary source of dietary AS) is associated with increased car- diometabolic risk in adolescents and young adults [51]. Therefore, the reduction of AS intake to AHA-recom- mended levels is an important outcome, and suggests components of the FF intervention approach should be evaluated among young adults, who tend to be high AS consumers. Using the mixed methods approach, improvements in the intervention content and structure were also identi- fied which may improve the feasibility and acceptability of an Internet and incentives-based program targeting college freshmen. Major themes included reducing the recommended number of meals associated with the pro- vided meal plan due to time constraints and difficulty adhering to the plan while in a buffet-style, social dining environment typical of college dining facilities, which is consistent with recent research on meal frequency and weight loss [52]. Major themes also included the need to reduce e-mail frequency to one time per week, with a focus on self-regulation strategies and success stories from similar peers, and the need for in-person interaction such as weekly group activities or incentive-based com- petitions between peers. These themes are consistent with prior research in this area. For example, college students have reported that environmental barriers to eating healthy include the time constraints associated with being a student, thus making it difficult to fit in healthy snacks or obtain healthful meals; unhealthful food served at university dining halls, encouraging over- eating; a lack of access to healthful food and the inability to travel to a grocery store; and the high costs of healthy foods [16]. These barriers align with feedback from stu- dents in the present investigation. Future interventions in this population segment could include healthful meal suggestions that align with foods accessible in campus dining halls, meals plans with less frequent eating occa- sions (i.e., three meals/day), and intervention approaches which are sensitive to the time constraints faced by col- lege students (i. e., weekly vs. daily e-mails). Previous work in this area [15,16] has indicated that social support from peers motivates students to be more physically active. Despite time constraints, college stu- dents have expressed a desire for more frequent in-per- son interactions as part of a weight management inter- vention program [19]. Our findings are consistent with this, as students were interested in regular small group interaction as a social support network. The weigh sta- tion kiosk was also viewed favorably, as a novel method to promote weekly self-weighing, which appears to be important for long-term successful weight management [53]. This preliminary investigation has several strengths, including the mixed-methods approach to develop and evaluate an intervention addressing multiple health be- haviors which resulted in weight loss, improvements in Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 438 dietary habits and in self-efficacy for physical activity. The attrition rate was very low (only two participants withdrew), which has also been noted in previous incen- tive-based weight management interventions in college students [19-21]. The small sample size, 12-week inter- vention duration and lack of a long-term follow-up are limitations of this preliminary investigation. Neverthe- less, these findings could be used to develop a lar- ger-scale Internet-and incentive-based weight loss pro- gram targeting overweight and obese college students. 5. CONCLUSION SCT-based interventions with modest incentives de- livered via Internet can significantly decrease weight and improve eating behaviors (decreased energy, fat and AS intake), psychosocial mediators of physical activity and dietary intake in overweight and obese college students. Future Internet-based interventions should include more frequent in-person interaction, such as group meetings for social support and possibly friendly competition. Fu- ture research should also include a more diverse popula- tion and include environmental components using multi- level approaches to promote weight loss efforts. Qualita- tive feedback from this study suggests opportunities to further adapt this weight loss intervention to weight gain prevention programs for a broader weight range of stu- dents and not just overweight/obese students. REFERENCES [1] McTigue, K.M., Garrett, J.M. and Popkin, B.M. (2002) The natural history of the development of obesity in a cohort of young US adults between 1981 and 1998. An- nals of Internal Medicine, 136, 857-864. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-12-200206180- 00006 [2] Lewis, C.E., Jacobs Jr., D.R., McCreath, H., Kiefe, C.I., Schreiner, P.J., Smith, D.E., et al. (2000) Weight gain continues in the 1990s: 10-year trends in weight and overweight from the CARDIA study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 151, 1172-1181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010167 [3] Anderson, E.S., Wojcik, J.R., Winett, R.A. and Williams, D.M. (2006) Social-cognitive determinants of physical activity: The influence of social support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and self-regulation among partici- pants in a church-based health promotion study. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 25, 510-520. [4] Racette, S.B., Deusinger, S.S., Strube, M.J., Highstein, G.R. and Deusinger, R.H. (2005) Weight changes, exer- cise, and dietary patterns during freshman and sophomore years of college. Journal of American College Health: Journal of ACH, 53, 245-251. http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JACH.53.6.245-251 [5] Holm-Denoma, J.M., Joiner, T.E., Vohs, K.D. and Heat- herton, T.F. (2008) The “freshman fifteen” (the “freshman five” actually): Predictors and possible explanations. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 27, S3-9. [6] Hovell, M.F., Mewborn, C.R., Randle, Y. and Fowler- Johnson, S. (1985) Risk of excess weight gain in univer- sity women: A three-year community controlled analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 10, 15-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(85)90049-8 [7] Lloyd-Jones, D.M., Liu, K., Colangelo, L.A., Yan, L.L., Klein, L., Loria, C.M., et al. (2007) Consistently stable or decreased body mass index in young adulthood and lon- gitudinal changes in metabolic syndrome components: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Circulation, 115, 1004-1011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.6486 42 [8] Anderson, L.M., Quinn, T.A., Glanz, K., Ramirez, G., Kahwati, L.C., Johnson, D.B., et al. (2009) The effec- tiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity inter- ventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37, 340-357. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.003 [9] Gokee-LaRose, J., Gorin, A.A., Raynor, H.A., Laska, M.N., Jeffery, R.W., Levy, R.L., et al. (2009) Are stan- dard behavioral weight loss programs effective for young adults? International Journal of Obesity, 33, 1374-1380. [10] Walsh, J.R., White, A.A. and Greaney, M.L. (2009) Using focus groups to identify factors affecting healthy weight maintenance in college men. Nutrition Research (New York, NY), 29, 371-378. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2009.04.002 [11] Wang, Y. (2008) Tai Chi exercise and the improvement of mental and physical health among college students. Medicine and Sport Science, 52, 135-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000134294 [12] Liu, K., Daviglus, M.L., Loria, C.M., Colangelo, L.A., Spring, B., Moller, A.C., et al. (2012) Healthy lifestyle through young adulthood and the presence of low car- diovascular disease risk profile in middle age: the Coro- nary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults (CAR- DIA) study. Circulation, 125, 996-1004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.0606 81 [13] Anding, J.D., Suminski, R.R. and Boss, L. (2001) Dietary intake, body mass index, exercise, and alcohol: Are col- lege women following the dietary guidelines for Ameri- cans? Journal of American College Health: Journal of ACH, 49, 167-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07448480109596299 [14] Edmonds, M.J., Ferreira, K.J., Nikiforuk, E.A., Finnie, A.K., Leavey, S.H., Duncan, A.M., et al. (2008) Body weight and percent body fat increase during the transition from high school to university in females. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 108, 1033-1037. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 439 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2008.03.002 [15] Strong, K.A., Parks, S.L., Anderson, E., Winett, R. and Davy, B.M. (2008) Weight gain prevention: Identifying theory-based targets for health behavior change in young adults. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 108, 1708-1715. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2008.07.007 [16] Greaney, M.L., Less, F.D., White, A.A., Dayton, S.F., Riebe, D., Blissmer, B., et al. (2009) College students’ barriers and enablers for healthful weight management: A qualitative study. Journal of Nutrition Education and Be- havior, 41, 281-286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2008.04.354 [17] Calfas, K.J., Sallis, J.F., Nichols, J.F., Sarkin, J.A., John- son, M.F., Caparosa, S., et al. (2000) Project GRAD: Two-year outcomes of a randomized controlled physical activity intervention among young adults. Graduate Ready for Activity Daily. American Journal of Preventive Medi- cine, 18, 28-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00117-8 [18] Kelly, N.R., Mazzeo, S.E. and Bean, M.K. (2013) Sys- tematic review of dietary interventions with college stu- dents: Directions for future research and practice. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 45, 304-313. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2012.10.012 [19] Dennis, E.A., Potter, K.L., Estabrooks, P.A. and Davy, B.M. (2012) Weight gain prevention for college fresh- men: Comparing two social cognitive theory-based inter- ventions with and without explicit self-regulation training. Journal of obesity, 2012, 803769. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/803769 [20] Greene, G.W., White, A.A., Hoerr, S.L., Lohse, B., Schem- bre, S.M., Riebe, D., et al. (2012) Impact of an online healthful eating and physical activity program for college students. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP, 27, e47-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.110606-QUAN-239 [21] Dour, C.A., Horacek, T.M., Schembre, S.M., Lohse, B., Hoerr, S., Kattelmann, K., et al. (2013) Process evalua- tion of Project WebHealth: A nondieting web-based in- tervention for obesity prevention in college students. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 45, 288- 295. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2012.10.001 [22] Hivert, M.F., Langlois, M.F., Berard, P., Cuerrier, J.P. and Carpentier, A.C. (2007) Prevention of weight gain in young adults through a seminar-based intervention pro- gram. International Journal of Obesity, 31, 1262-1269. [23] Von Ah, D., Ebert, S., Ngamvitroj, A., Park, N. and Kang, D.H. (2004) Predictors of health behaviours in college students. Journal of advanced nursing, 48, 463-474. [24] Escoffery, C., Miner, K.R., Adame, D.D., Butler, S., Mc- Cormick, L. and Mendell, E. (2005) Internet use for health information among college students. Journal of American College Health: Journal of ACH, 53, 183-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JACH.53.4.183-188 [25] Park, A., Nitzke, S., Kritsch, K., Kattelmann, K., White, A., Boeckner, L., et al. (2008) Internet-based interven- tions have potential to affect short-term mediators and in- dicators of dietary behavior of young adults. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 40, 288-297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2008.02.001 [26] An, J.Y., Hayman, L.L., Park, Y.S., Dusaj, T.K. and Ayres, C.G. (2009) Web-based weight management programs for children and adolescents: a systematic review of random- ized controlled trial studies. ANS Advances in Nursing Science, 32, 222-240. [27] Stevens, V.J., Funk, K.L., Brantley, P.J., Erlinger, T.P., Myers, V.H., Champagne, C.M., et al. (2008) Design and implementation of an interactive website to support long- term maintenance of weight loss. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 10, e1. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.931 [28] Neuhauser, L. and Kreps, G.L. (2003) Rethinking com- munication in the E-health era. Journal of Health Psy- chology, 8, 7-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105303008001426 [29] Abrantes, A.M., Lee, C.S., MacPherson, L., Strong, D.R., Borrelli, B. and Brown, R.A. (2009) Health risk behav- iors in relation to making a smoking quit attempt among adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 142-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9184-1 [30] Couper, M. (2000) Web surveys: A review of issues and approaches. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64, 464-494. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/318641 [31] American Dietetic Association (2007) Adult weight man- agement toolkit. American Dietetic Association, Chicago. [32] Mendlinger, S. and Cwikel, J. (2008) Spiraling between qualitative and quantitative data on women’s health be- haviors: A double helix model for mixed methods. Quali- tative Health Research, 18, 280-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049732307312392 [33] Garner, D.M., Olmsted, M.P., Bohr, Y. and Garfinkel, P.E. (1982) The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12, 871- 878. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700049163 [34] Courneya, K.S., Jones, L.W., Rhodes, R.E. and Blanchard, C.M. (2004) Effects of different combinations of intensity categories on self-reported exercise. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 75, 429-433. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2004.10609176 [35] Pereira, M.A., Fitzer Gerald, S.J., Gregg, E.W., Joswiak, M.L., Ryan, W.J., Suminski, R.R., et al. (1997) A collec- tion of Physical Activity Questionnaires for health-related research. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 29, S1-205. [36] Gionet, N.J. and Godin, G. (1989) Self-reported exercise behavior of employees: A validity study. Journal of Oc- cupational Medicine, 31, 969-973. [37] Godin, G., Jobin, J. and Bouillon, J. (1986) Assessment of leisure time exercise behavior by self-report: A concur- rent validity study. Canadian Journal of Public Health= Revue canadienne de sante publique, 77, 359-362. [38] Winett, R.A., Anderson, E.S., Wojcik, J.R., Winett, S.G. and Bowden, T. (2007) Guide to health: Nutrition and physical activity outcomes of a group-randomized trial of an Internet-based intervention in churches. Annals of Be- havioral Medicine, 33, 251-261. [39] Bandura, A. (2001) Social cognitive theory: An agentic Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  B. M. Davy et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 3 (2013) 429-440 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 440 perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 [40] Anderson, E.S., Winett, R.A. and Wojcik, J.R. (2000) Social-cognitive determinants of nutrition behavior among supermarket food shoppers: A structural equation analysis. Health psychology, 19, 479-486. [41] Krueger, R. (2000) Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 3rd Edition, Sage, Thousand Oaks. [42] Patton, M. (1990) Qualitative evaluation and research. 2nd edition, Sage, Thousand Oaks. [43] Pope, C., Ziebland, S. and Mays, N. (2000) Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. British Medical Journal, 320, 114-116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114 [44] US Department of Health and Human Services (2005) Dietary guidelines for Americans. [45] Raynor, H.A., Jeffery, R.W., Phelan, S., Hill, J.O. and Wing, R.R. (2005) Amount of food group variety con- sumed in the diet and long-term weight loss maintenance. Obesity Research, 13, 883-890. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/oby.2005.102 [46] Bandura, A. (1997) Self efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Co., New York. [47] Bandura, A. (2004) Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31, 143-164. [48] Neutens, J.J. and Robinson, L. (2002) Research tech- niques for the health sciences. Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco. [49] Johnson, R.K., Appel, L.J., Brands, M., Howard, B.V., Lefevre, M., Lustig, R.H., et al. (2009) Dietary sugars in- take and cardiovascular health: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 120, 1011-1020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.1926 27 [50] Myers, E.F., Khoo, C.S., Murphy, W., Steiber, A. and Agarwal, S. (2013) A critical assessment of research needs identified by the dietary guidelines committees from 1980 to 2010. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113, 957-971 e951. [51] Ambrosini, G.L., Oddy, W.H., Huang, R.C., Mori, T.A., Beilin, L.J. and Jebb, S.A. (2013) Prospective associa- tions between sugar-sweetened beverage intakes and car- diometabolic risk factors in adolescents. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 98, 327-334. http://dx.doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.051383 [52] Bachman, J.L. and Raynor, H.A. (2012) Effects of ma- nipulating eating frequency during a behavioral weight loss intervention: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Obesity, 20, 985-992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.360 [53] Butryn, M.L., Phelan, S., Hill, J.O. and Wing, R.R. (2007) Consistent self-monitoring of weight: A key component of successful weight loss maintenance. Obesity, 15, 3091- 3096. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.368

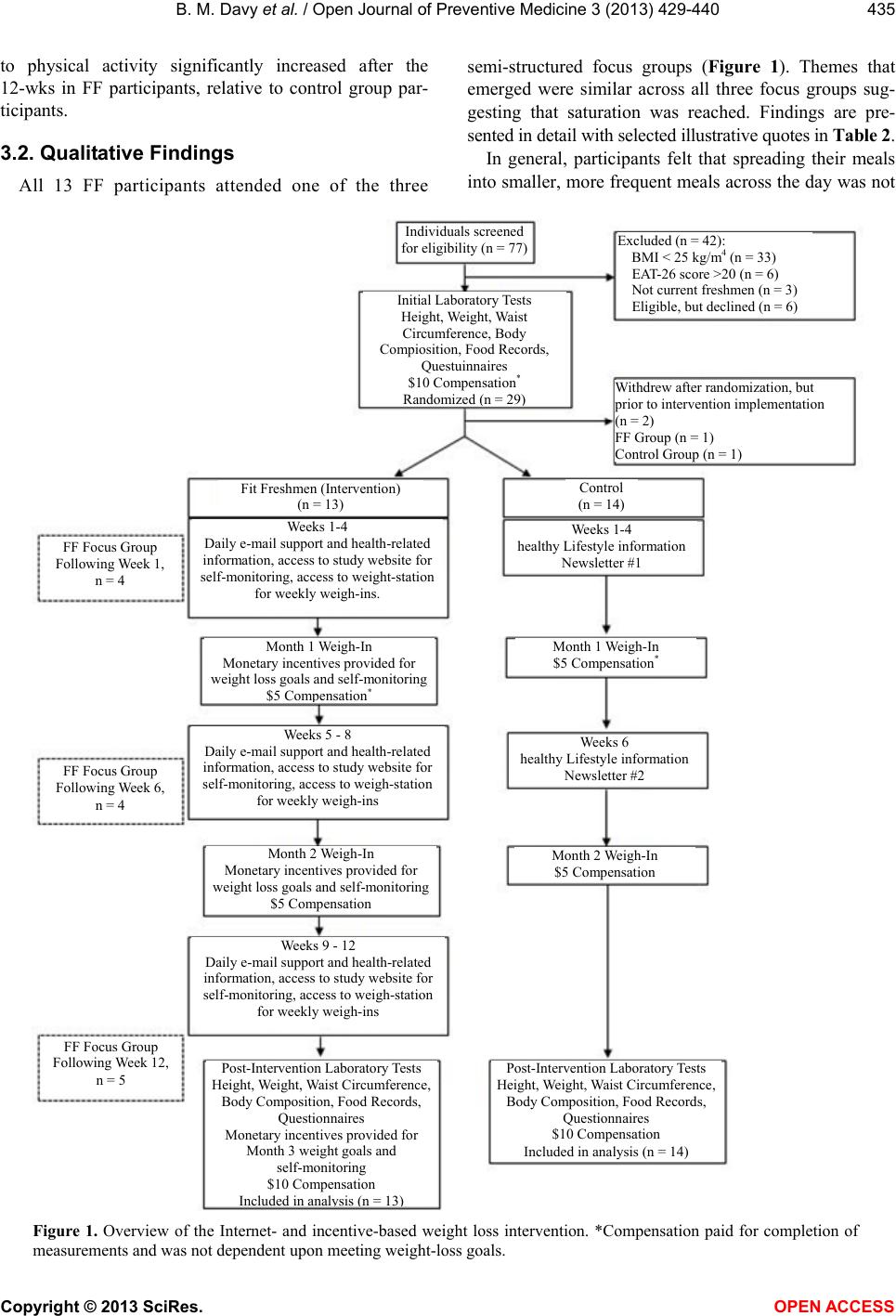

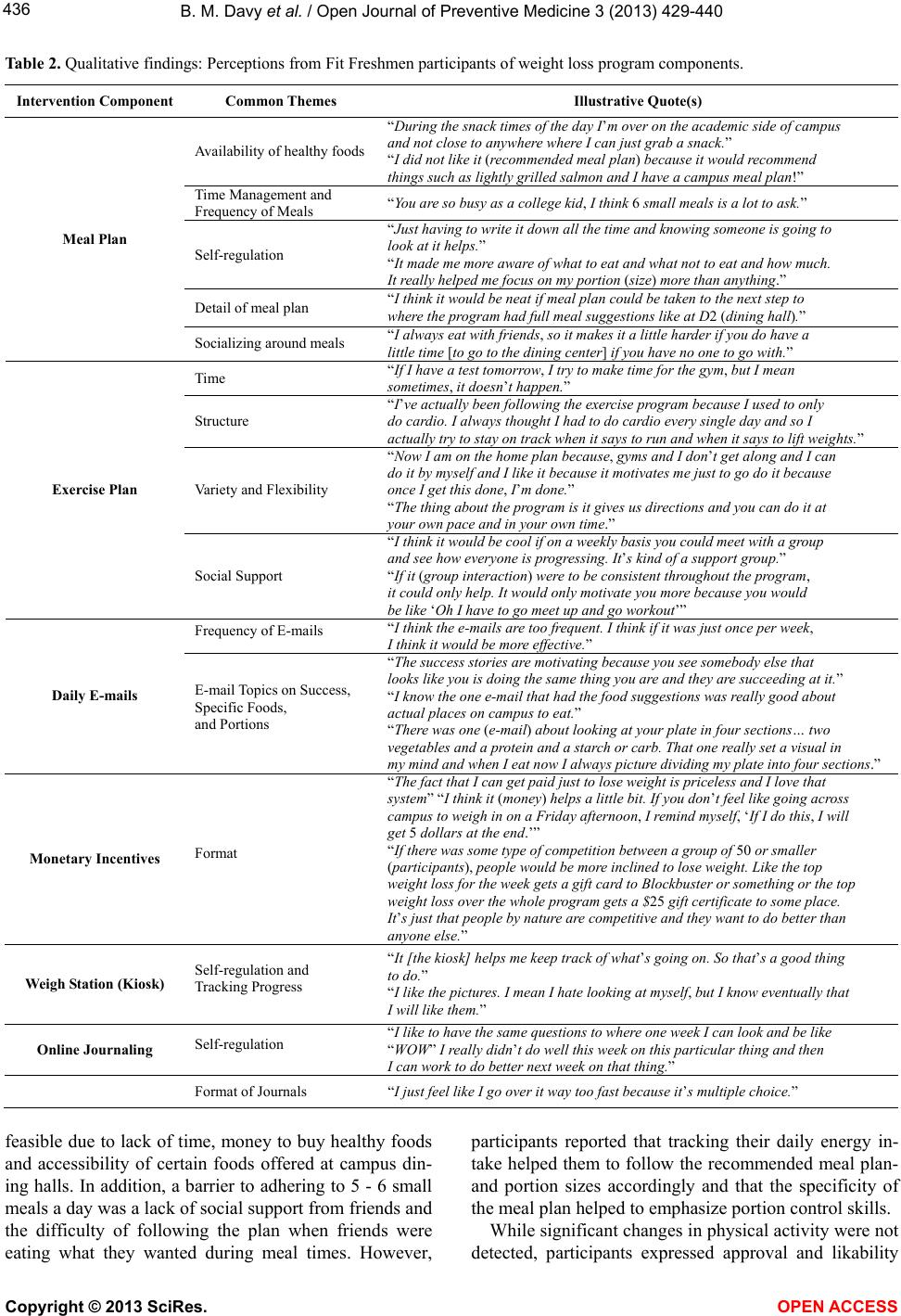

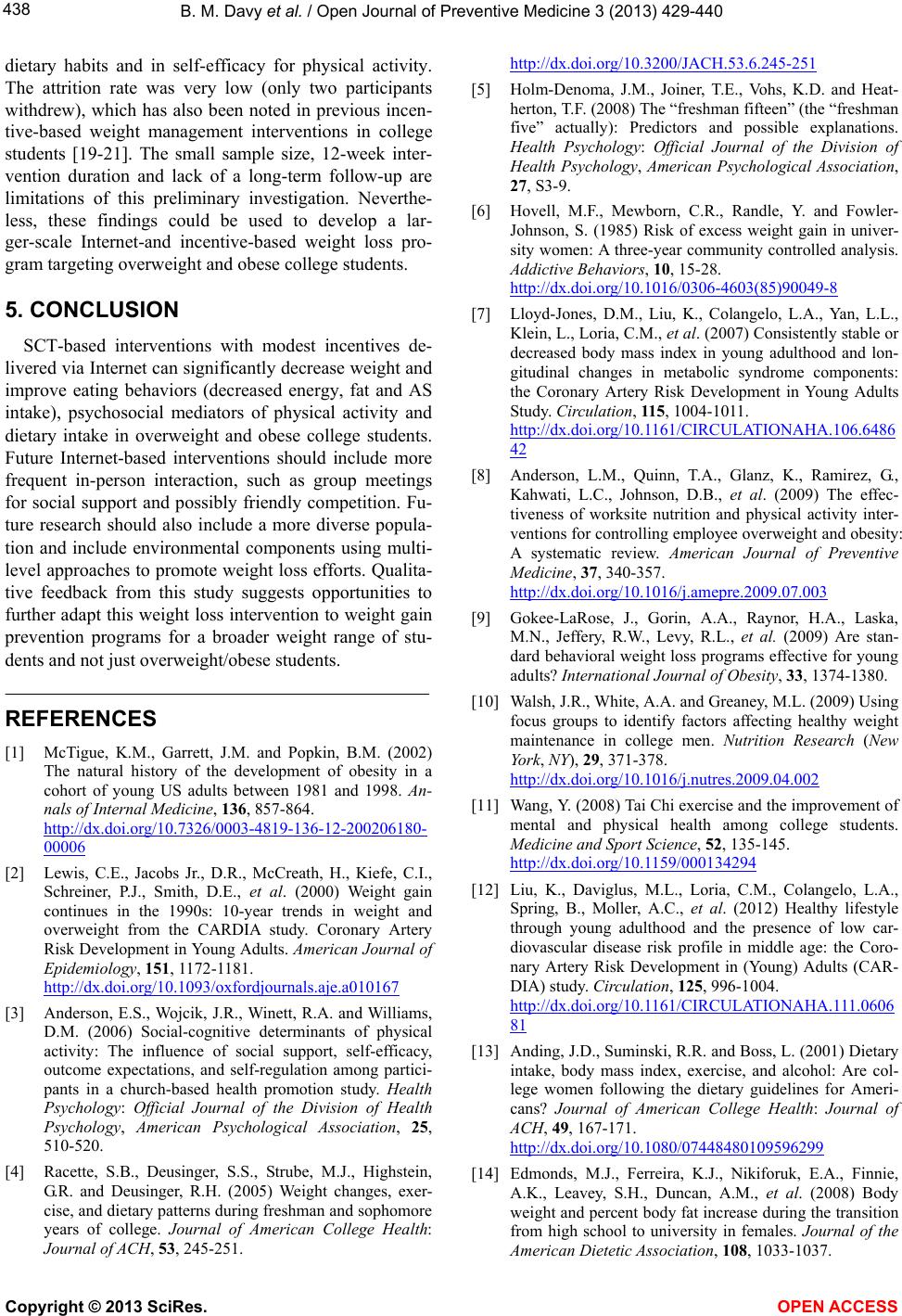

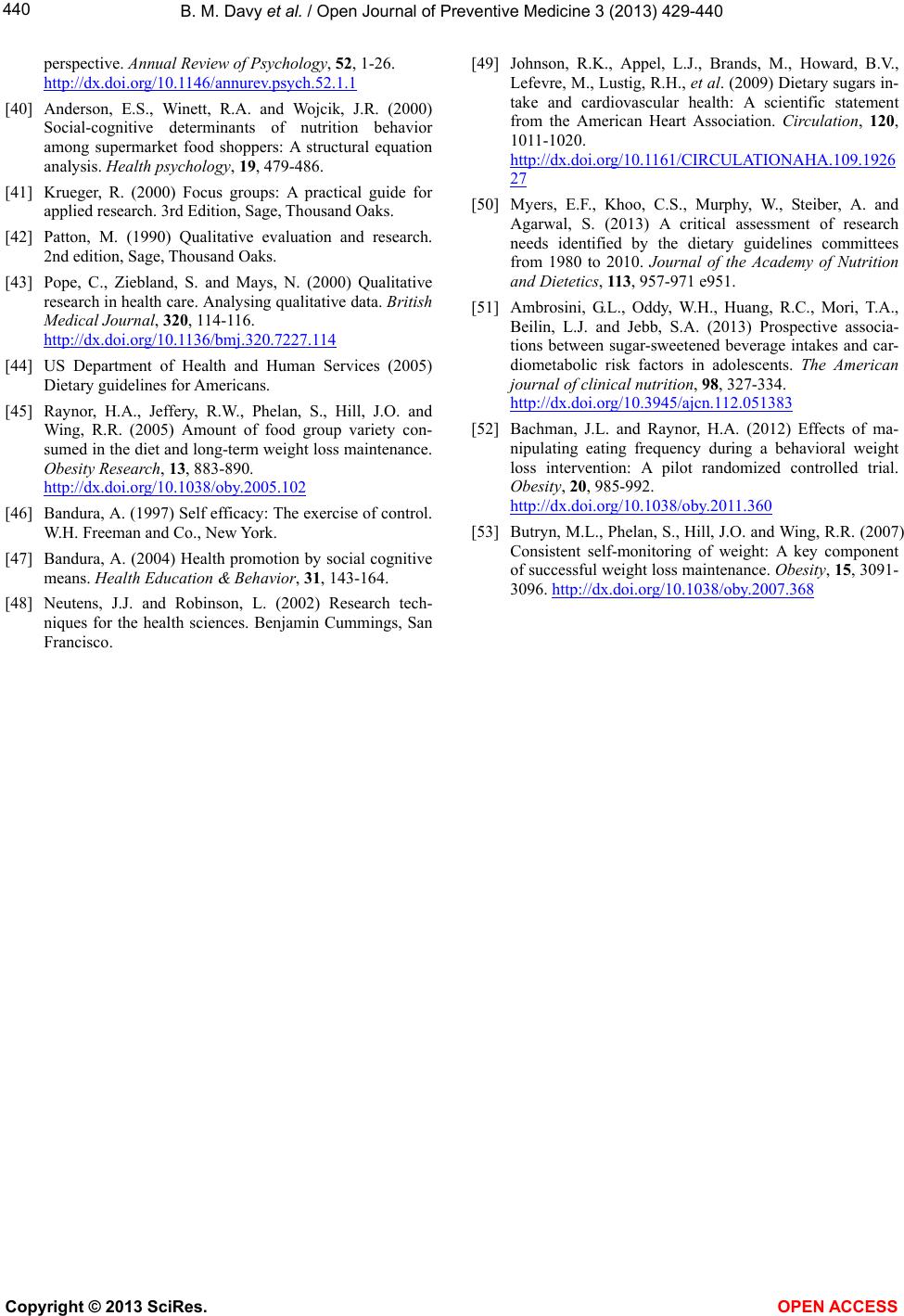

|