Open Journal of Applied Sciences, 2013, 3, 5-11 doi:10.4236/ojapps.2013.32B002 Published Online June 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojapps) Supply Mix Optimization for Decentralized Energy Systems J. K. Gruber, J. L. Mínguez Fernández, M. Prodanovic Electrical Systems Unit, IMDEA Energy Institute, Móstoles (Madrid), Spain Email: jorn.gruber@imdea.org, joseluisminguezfernandez@gmail.com, milan.prodanovic@imdea.org Received 2013 ABSTRACT In recent years, the energy sector has undergone an important transformation as a result of technological progress and socio-economic development. The continuous integration of renewable energy sources forces a gradual transition from the traditional business model based on a reduced number of large power plants to a more decentralized energy produc- tion. The decentralization and the increased number of energy sources lead to a series of new challenges in the energy sector. This paper presents an approach to determine the optimal energy supply mix for small and medium sized build- ings or installations. The optimization algorithm considers the electricity and heat demand and determines the optimal combination of energy sources by minimizing an economic index. The optimization problem can be solved for multiple demand profiles and takes into account the possibility to integrate accumulator systems. The proposed approach pro- vides a high degree of flexibility and can be used to study the influence of the energy prices on the optimal energy sup- ply mix. The performance of the proposed optimization approach is illustrated by the results obtained from a simulation example. Keywords: Energy Supply Mix; Optimal Configuration; Decentralized Generation 1. Introduction The prosperity of modern societies is closely related to the availability of energy and the continuous supply is an important factor for the industrial development. In many countries a significant part of the energy demand is satis- fied with fossil fuels such as oil and gas or by means of nuclear power production. The constantly growing de- mand for fossil fuels and the shrinking reserves in com- bination with the necessary and more expensive modern extraction technologies lead to increased energy prices. Today, many economies depend highly on energy im- ports from a small group of countries with oil and gas reserves. The environmental impact of fossil fuels as well as the risks related to nuclear power generation gave rise to a serious discussion about the effects of traditional energy production. These drawbacks led in recent years to an increased research and development in alternative energy sources. In recent years, the significant increase in the integra- tion of renewable energy sources compensated, at least to some extent, the problems related to the traditional en- ergy production. The continuous increase of alternative energy sources, especially wind turbines and photo- voltaic panels, emphasizes the change from a centralized energy production with few large power plants to a more distributed generation. The power production near the place of consumption reduces the transmission losses, increases the energy efficiency and helps to ensure a high quality in the energy supply. Nowadays, buildings contribute strongly to the total energy demand and account in some countries for up to 45% of the primary energy consumption [1, 2, 3]. A suit- able energy mix, especially the use of renewable energy sources, and an optimal supply system can improve the energy efficiency of buildings and reduce costs. The op- timal energy supply system for buildings in the tertiary sector is determined in [4] solving an economic minimi- zation problem by mixed integer linear programming (MILP). The algorithm in [5] considers both centralized and decentralized technologies and determines the opti- mal technology mix for a neighbourhood or a small town taking into account constraints such as a maximum emis- sion of CO2. The integrated approach presented in [6] improves the energy efficiency combining the computa- tion of the optimal energy supply mix with a proactive energy management. The multi-objective optimization of an energy supply system for an industrial district [7] in- cludes the costs of the energy supply system and the en- vironmental impact of a positive or negative CO2 balance with respect to traditional systems. In [8] the optimal technology mix is determined with a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJAppS  J. K. GRUBER ET AL. 6 special focus on the variability in energy production as a result of an increased wind power deployment. The au- thors underline the importance of storage systems which provide certain flexibility in the integration of intermit- tent energy sources. The prototype energy model pre- sented in [9] deals with the complex problem to consider social factors in the optimization of the energy supply mix. The approach translates energy policy goals, both quantitative and qualitative ones, into a set of mathe- matical expressions for the posterior optimization. This paper presents a method to determine the optimal energy supply mix for small and medium sized buildings under consideration of seasonal profiles for electricity and heat demand. The optimization approach focuses on distributed energy generation in combination with elec- tric batteries and backup grid connection. The minimiza- tion of the objective function, an economic index based on the initial inversion and the generation costs, is car- ried out with sequential quadratic programming (SQP). The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a detailed problem description and defines the objective function. The proposed approach for the minimization of the cost is given in Section 3. The implementation of the proposed optimization procedure and the obtained results for an office building are given in Section 4. Finally, in Section 5 the mayor conclusions are drawn. 2. Problem Description This work presents an approach to determine the optimal energy supply mix for a small or medium sized building minimizing an economic index. The general objective function to be minimized is given by: Jx ehb JJ JJxxxx (1) where x denotes the vector with the installed capacities and N is the total number of energy sources considered in the cost function. The terms e Jx e , h and represent the costs related to the electricity sources, the heat sources and the battery, re- spectively. The capacities are given by Jx b J x ex for the electricity sources, h hx ,, TT eh for the heat sources and b for the battery. The vector of capacities used in (1) is defined as x T b xxx The cost related to the electricity sources is defined as: . () e x e J ,, ()() () eeef eeve JJ Jxxx (2) being , the annual fixed costs and , the variable costs. The fixed costs are given by: () ef e Jx() ev e Jx ,() ef e Jx () () ,() 1 () eii N ee ef ei ie I Jy x (3) where ()i e , ()i e and ()i e are the installed capacity, the necessary initial investment costs per installed capacity and the technical lifetime of the i-th electricity source, respectively. Note that the capacity ()i e corresponds to the i-th element of the vector e. The variable electric- ity costs are defined as: x () ( ii e ,() ev e Jx , ev ) 1 () e N e ee i Jp e s x (4) where ()i e is the amount of energy of the i-th electric- ity source consumed during a year and is the cor- responding price per energy unit. The shortfall of electric energy is considered as an additional term based on the amount of missing energy e ()i e p and the corresponding penalization cost e per unit. In the case of heating, the cost is given by: () hh x hv J J , () f h, () () hh hh JJ xx ,hf J x (5) with the annual fixed costs and the variable costs defined as: (x) h ,() hv h xJ () () () ii hh i h ,() hf h 1 h N i I ()ii h Jy x s () h (6) , 1 () h N hv hhh i Jp x (7) where ()i h , ()i h and h ()i are the installed capacity, the initial investment per installed capacity and the technical life cycle of the i-th heat source, respectively. It is im- portant to mention that ()i h is the i-th element of the capacity vector The variable . h x()i h denotes the amount of energy of the i-th heat source consumed during a year and is the price per energy unit. Besides, the vari- able costs consider the case of a shortfall where h ()i h p de- notes the amount of missing heat and h is the penali- zation price of each energy unit. For the battery, the cost () bb x , () b is defined as: , () ) bb bfb ( bv xJ xxJ ) b (8) with the fixed costs ,( bf x and the variable costs ,( bv b ) x given by: ,() b b b bf b I y () 1 e N b Jx (9) ()ii e,() bv b i x p (10) where b denotes the installed battery capacity, b represents the necessary initial investment per storage capacity and b is the lifetime of the battery. The vari- able costs depend on the amount of energy y ()i b from the electricity sources used for battery charging and the corresponding price per energy unit. ()i e p The amounts of consumed (()i e , ()i h and b ()i ) and missing energy (e and h ) are determined during the optimization as these values depend directly on the ca- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJAppS  J. K. GRUBER ET AL. 7 pacities of the energy sources. The initial investments (()i e ,()i h and b ), the technical lifetimes (()i e ,()i h and b), the prices per energy unit ( and ) as well as the costs for each missing energy unit ( y()i e p()i h p ()i e and ()i h ) are constant parameters and their values are known. 3. Optimization Procedure The objective of the optimization procedure is to mini- mize the energy costs (1) for a given electricity and heat demand. The use of multiple profiles allows considering the variations in the demands throughout the year and provides a more realistic estimation of the energy costs. For a given set of capacities and given demand profiles, the chosen approach calculates the amount of energy consumed from each source and the amount of missing energy to satisfy the demand. The following sections explain in detail the use of the available energy sources to cover the demands. 3.1. Initial Considerations Consider a sampling time of and the installed capacities 1h s t ()i e for , 1, , e iN ()i h for 1,i,h N and b . Furthermore, consider the electricity and heat profiles for a certain day given by the hourly demand and with . ( e d)j j () ()j , 2 ()ii ee h The amount of energy which can be produced in each sample by a source is given by the expres- sions d0,3, 2 s j 0, 3 () () ()e i jf ()ii hh jxt with 1,,e iN and ()() () ()h i s jfjxt with 1,,h iN where the parameters () () i e j and ()i h() j are used to consider external or internal influences on the energy production. For controllable energy sources, e.g. gas tur- bines, grid connection or biomass boiler, the possible energy production is assumed to be () () i e fj1 and . In the case of the non-controllable energy sources, i.e. renewable sources such as wind turbines, photovoltaic panels or solar thermal collectors, the en- ergy production also depends on some environmental conditions leading to and . For controllable energy sources with simultaneous heat and energy production, e.g. combined heat and power (CHP), the parameters e ()i h()fj1 () 0 i e () ()fj ()fj ()ii 1() 0( i fj)1 h and () h () () i fj i with are used. () ( )1 ii The operation modes of the considered battery does not admit simultaneous charging and discharging, i.e. in a given moment the battery represents either an energy source or an energy sink. Another limitation arises from the power rate capabilities c and d for charging and discharging, respectively. The amount of energy that can be drawn from or stored to the battery in each sample, without taking into account the current state of the bat- tery, must not exceed vj m m m cs () ct and () dt ds vj m with 0,, 23j . The considered capacities ()i e , ()i h and b allow computing the fixed costs of the energy sources given by (3), (6) and (9). The variable costs (4), (7) and (10) have to be calculated after determining the amount of energy supplied by each source. 3.2. Assignment of Electricity Sources The satisfaction of the energy demand using different sources is based on economic rules with the objective to minimize the costs. For a given set of installed capacities x, priority is given to sources with a cheaper generation. The optimization satisfies the electricity demand using an iterative procedure with the following assignment order: renewable sources, CHP and controllable sources. For simplicity of the notation and without loss of generality it is assumed that the electricity sources with the capacities ()i e for e i1,, N (0) () () e rjd are already sorted according to the sequence of assignment. With the initially unsatisfied electricity demand given by for e j0,, 23j , in the i-th iteration with 1,, e iN the amount of energy drawn from the corresponding source is given by: 1) () ()(),0,0, ,23 i e r jgjj () ( () max ii ee cj () ( () ee rj () () ee uj () 0,, 23j e (11) Then, the remaining unsatisfied demand becomes: 1) () ()(),0, ,23 ii i e rjcj j (12) and the unused amount of energy which could be pro- duced by the i-th energy source is: () () ()(),0, ,23 iii e gjcjj (13) Finally, finishing the iterative procedure, the total amount of energy generated by each source throughout an entire year can be calculated by: 23 () 0 365( ),1,, ii ee j cj iN (14) After using the energy sources, the remaining electric demand for has to be satisfied by the battery. e N () ( e N e r)j0,, 23j 3.3. Assignment of Battery The battery is charged by means of the electricity sources using an iterative procedure and the previously described assignment order. Taking into account only the power rate limitations, the theoretical amount of energy that can be stored to the battery in a sample is for (0) ()() cc wjvj . With the known initial state of charge and the still unsatisfied demand for (0) c q j () (0) () () e N be rjr j0,, 23, the amount of energy charged to the battery in the i-th iteration with 1,i,e N (the charged energy is drawn Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJAppS  J. K. GRUBER ET AL. 8 from the i-th source) is calculated as: ()()( )(1) () min(),, iik bebc cj ujxqw i c (15) if and (0) ()0 b rj() () 0 i b cj if with and being a counter. Evidently, charging will take place only in samples without demand, i.e. (0) ()0 b rj 0,, 23j24 (kji (0) ()0 b rj 1) . After storing in the battery, the remaining amount of energy that could be stored in a sample is given by: () () i b cj ()( 1)() ()()(),0, ,23 ii i cc b wjwjcj j (16) and the state of charge of the battery can be written as: (1)()() (),0, ,23 kki ccb qqcjj (17) The state of charge depends on the charging in previous samples due to the recursive character of (17). As a direct consequence, (15)-(17) have to be evaluated together for each sample in the i-th iteration. (1)k c q After charging the battery using the different energy sources, the state of charge is given by (24 ) (0) e dc qq and represents the initial state considered in the dis- charging procedure. The amount of energy drawn from the battery in each sample is defined as: (0) () min(),(), (),0, ,23 bbdd zjr jqjvjj e (18) The resulting unsatisfied demand after using the bat- tery can be written as: (1) (0) ()()(),0, ,23 bb b rjrjzj j (19) and the amount of energy stored in the battery is: (1)() (),0,,23 ddb qjqjzjj (20) Finally, after the charging and discharging procedures, the amount of energy taken from each source throughout the year and stored in the battery is given by: 23 () () 0 365( ),1,, ii bb j cj iN (21) and the overall unsatisfied demand becomes: 23 (1) 0 365( ) eb j rj (22) 3.4. Assignment of Heat Sources The heat demand is covered step by step using an itera- tive procedure that gives priority to sources with a cheaper energy production. Based on this simple eco- nomic rule, the assignment order applied by the proce- dure is: renewable sources, CHP and controllable sources. For simplicity of the notation and without loss of gener- ality it is assumed that the considered heat sources with the capacities ()i h with are already sorted in the given assignment order. 1,, h i Defining the initial heat demand as for (0) () () hh rjdj 0,, 23j , the amount of energy generated in the i-th iteration by the corresponding source is given by: ()( 1)() () max()(),0,0, ,23 iii hhh cjr jgjj h j (23) with the generated energy , the remaining unsat- isfied demand becomes: () () i h cj ()(1)() ()()(),0, ,23 ii i hh h rjrjcj j (24) Finally, after finishing the iterative procedure the total amount of heat generated by each source during an entire year is given by: 23 () () 0 365( ),1,, ii hh j cj iN (25) and the overall unsatisfied heat demand becomes: 23 () 0 365( ) h N hh j r (26) 3.5. Cost minimization The generated energy (()i e ,()i b ,()i h ) and the missing energy (e ,h ) determined with the assignment proce- dures are used to calculate the variable costs (4), (7) and (10). Furthermore, the fixed costs are given by (3), (6) and (9) for a given set of capacities . Finally, the fixed and variable costs allow computing the overall cost (1) related to the energy supply. x Now, the optimal capacities of the energy sources are calculated solving the following minimization prob- lem under consideration of constraints: * x *argmin() s.t. J A x xx xb (27) with c N and c b where c denotes the number of constraints. The optimization problem based on several iterative assignment procedures can then be solved with nonlinear programming (NLP). N 4. Implementation & Results The proposed approach for the minimization of the cost related to the energy supply of small and medium sized buildings has been implemented in Matlab. The optimal capacities are computed solving the optimization problem (27) with Matlab’s built-in function for sequen- tial quadratic programming (fmincon). * x 4.1. Implementation For the satisfaction of the electric demand, wind turbines, photovoltaic systems, gas turbines, CHP plants, grid connection and batteries have been considered. Heat pumps, oil boilers, CHP plants, solar thermal collectors N Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJAppS  J. K. GRUBER ET AL. 9 and biomass boilers have been taken into account for heating. The technical lifetimes (()i e ,()i h ,), the initial investments per capacity unit ( b y ()i e ,()i h ,b ) and the prices per energy unit (,) of the energy sources are given in Table 1. In the case of an energy shortfall, a penalization of ()i e p 10 ()i h p 00 €/kWh eh is used for elec- tricity and heat. The parameters () () i e j and () () i h j 0.3 for photovoltaic and solar thermal systems located in Madrid (Spain) have been taken from the Photovoltaic Geographical Informa- tion System (PVGIS) [10], see Figure 1. For wind tur- bines an average performance of 30%, i.e., has been assumed and for CHP systems the electric- ity/heat ratio is given by and . For all other electricity and heat sources, () () 0.3 i e fj () 0.7 i () () 1 i e fj ()i and have been used. () () 1 i h fj Two demand profiles (see Figure 2), one for winter and one for summer, have been used for the considered medium sized office building in Madrid. The optimiza- tion procedure of the energy supply mix considers half year of summer and half year of winter. Table 1. Technical lifetimes, investments per capacity and energy prices of the considered energy sources. Source Investment [€/kW] Price [€/kWh] Lifetime [a] wind turbine 2400 0.04 20 photovoltaic system 4000 0.02 25 gas turbine 1200 0.08 10 CHP plant 1300 0.06 10 grid connection 15.97 0.12 1 battery 500 €/kWh − 5 geothermal heat pump 1500 0.07 20 oil boiler 600 0.08 10 solar thermal collector 1000 0.03 25 biomass boiler 350 0.08 20 Figure 1. Efficiency of the photovoltaic and solar thermal systems in summer (dash-dotted line) and in winter (solid line) and for the wind turbine in all seasons (dashed line). 4.2. Results The implemented procedure was used to determine the optimal energy supply mix for the office building. The costs were optimized using current market prices (see Table 1) for the different energy sources. The obtained results of the energy consumption are given for the summer profile in Figure 3 and for the winter profile in Figure 4. It can be observed that that the major part of the electricity and heat demands are covered by fossil energy sources and only a reduced proportion is satisfied by renewable energy. Furthermore, some of the available technologies are not included in the optimal energy mix (batteries, geothermal heat pumps, solar thermal collectors and oil boilers) due to economic reasons. The capacities of the energy sources and the amount of energy produced by each source are given in Table 2. With the current prices, 82.7% of the energy demand is covered with fossil fuels, 5.2% is drawn from the grid and 12.1% is taken from renewable energy sources. In spite of the high capital costs of wind turbines Figure 2. The considered electricity and heat demands for winter (solid line) and summer season (dashed line). Figure 3. Satisfaction of the electricity (top) and heat de- mand (bottom) in summer. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJAppS  J. K. GRUBER ET AL. 10 and photovoltaic systems, these sources satisfy 14.1% of the yearly electricity demand. With the continuously decreasing prices of renewable energy sources and the rising fossil fuel prices, decen- tralized generation will be more important in the future. Furthermore, it is expected that the improvements in storage technologies will reinforce the use of batteries and other accumulator systems. Figure 4. Satisfaction of the electricity (top) and heat de- mand (bottom) in winter. Table 2. Capacities of the energy sources and amounts of energy generated during the year. Source Capacity [kW] Annual gen. [MWh] wind turbine 98.2 (6.0%) 258.0 (4.5%) photovoltaic system 191.3 (11.6%) 392.2 (6.8%) gas turbine 501.3 (30.4%) 2304.0 (39.9%) CHP plant 593.2 (36.0%) 2469.1 (42.8%) grid connection 191.2 (11.6%) 301.0 (5.2%) battery 0 0 geothermal heat pump 0 0 oil boiler 0 0 solar thermal collector 0 0 biomass boiler 73.7 (4.5%) 46.4 (0.8%) 5. Conclusions A procedure for the computation of the optimal supply mix for decentralized energy systems has been developed and implemented. The presented approach minimizes an objective function for a given energy demand using basic economic rules. The use of multiple profiles allows con- sidering seasonal variations in the electricity and heat demand. The described algorithm has been implemented in Matlab considering ten energy sources, including bat- teries and CHP systems. The optimization algorithm re- gards capital costs and variable costs resulting from the energy generation. Additional costs resulting from de- commissioning, waste management, CO2 transport and storage, fixed operating costs and others can be included easily in the minimization problem for a differentiated optimization and analysis of the supply mix. The optimal energy supply mix for a medium sized of- fice building located in Madrid (Spain) was determined using the proposed optimization procedure. The obtained results showed a predominance of energy production from fossil fuels for current market prices and only a reduced use of renewable energy. The high flexibility of the procedure allows studying changes in the optimal energy supply in function of the investment costs and energy prices. REFERENCES [1] L. Pérez-Lombard, J. Ortiz and C. Pout, “A Review on Buildings Energy Consumption Information,” Energy and Buildings, Vol. 40, No. 3, 2008, pp. 394-398. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2007.03.007 [2] J. Iwaro and A. Mwasha, “A Review of Building Energy Regulation and Policy for Energy Conservation in De- veloping Countries,” Energy Policy, Vol. 38, No. 12, 2010, pp. 7744-7755. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.08.027 [3] A. H. C. dos Santos, M. T.W. Fagá and E. M. dos Santos, “The Risks of An Energy Efficiency Policy for Buildings Based Solely on the Consumption Evaluation of Final Energy,” International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2013, pp. 70-77. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2012.07.017 [4] M. A. Lozano, J. C. Ramos, M. Carvalho and L. M. Serra, “Structure Optimization of Energy Supply Systems in Tertiary Sector Buildings,” Energy and Buildings, Vol. 41, No. 10, 2009, pp. 1063-1075. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2009.05.008 [5] C. Weber and N. Shah, “Optimisation Based Design of A District Energy System for An Eco-town in the United Kingdom,” Energy, Vol. 36, No. 2, 2011, pp. 1292-1308. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2010.11.014 [6] M. Prodanovic, T. Gafurov and M.B. Téllez, “A Demand Based Approach to Optimisation of Energy Supply Mix for Smart Buildings,” Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference, Wash- ington, 2012, pp. 1-8. doi:10.1109/ISGT.2012.6175731 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJAppS  J. K. GRUBER ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJAppS 11 [7] D. Buoro, M. Casisi, A. De Nardi, P. Pinamonti and M. Reini, “Multicriteria Optimization of A Distributed En- ergy Supply System for An Industrial Area,” Energy, 2013. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2012.12.003 [8] C. De Jonghe, E. Delarue, R. Belmans and W. D’haeseleer, “Determining Optimal Electricity Technol- ogy Mix with High Level of Wind Power Penetration,” Applied Energy, Vol. 88, No. 6, 2011, pp. 2231-2238. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.12.046 [9] A. Chee Tahir and R. Bañares-Alcántara, “A Knowledge Representation Model for the Optimisation of Electricity Generation Mixes,” Applied Energy, Vol. 97, 2012, pp. 77-83. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.12.077 [10] T. Huld, R. Müller and A. Gambardella, “A New Solar Radiation Database for Estimating PV Performance in Europe and Africa,” Solar Energy, Vol. 86, No. 6, 2012, pp. 1803-1815. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2012.03.006

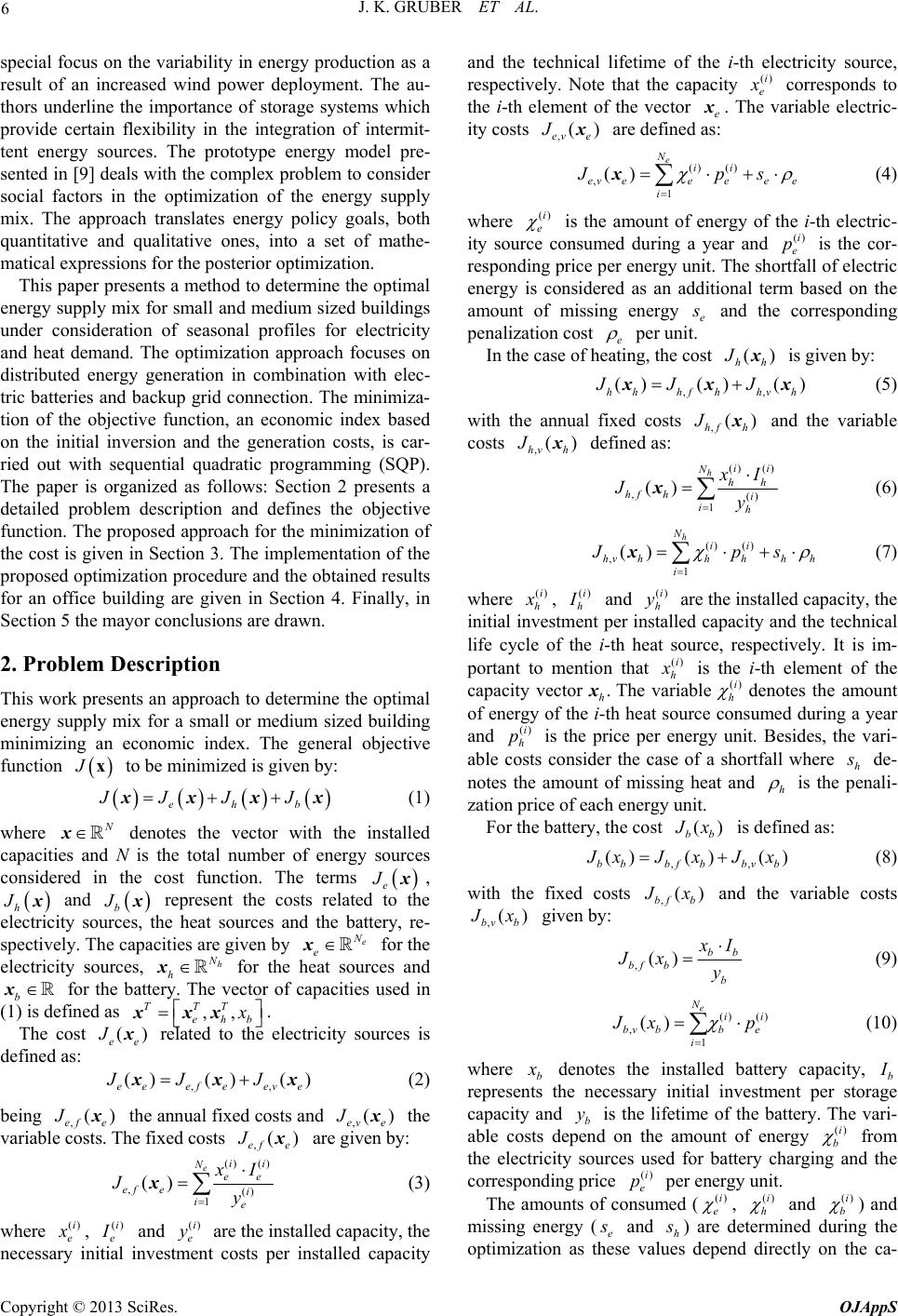

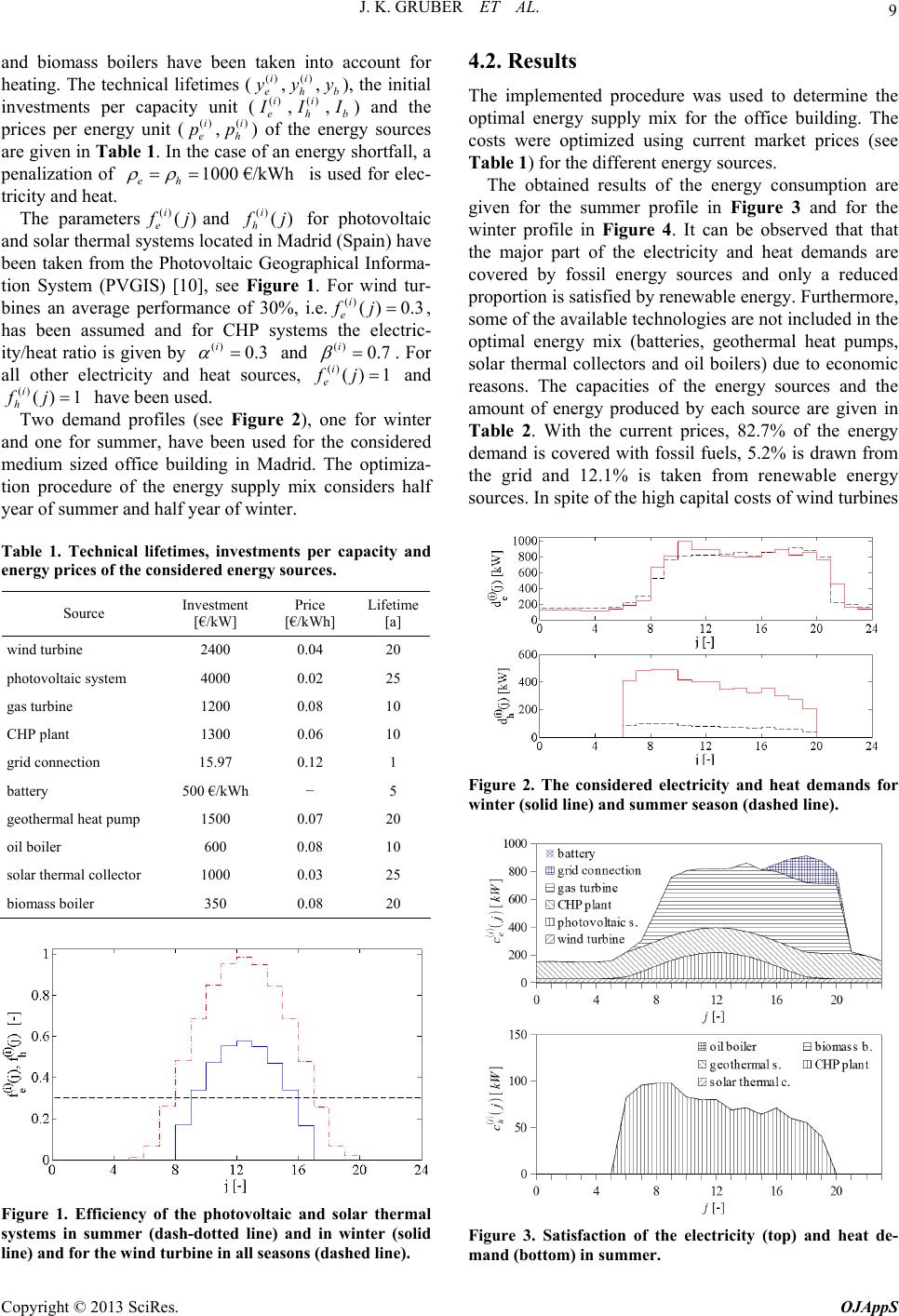

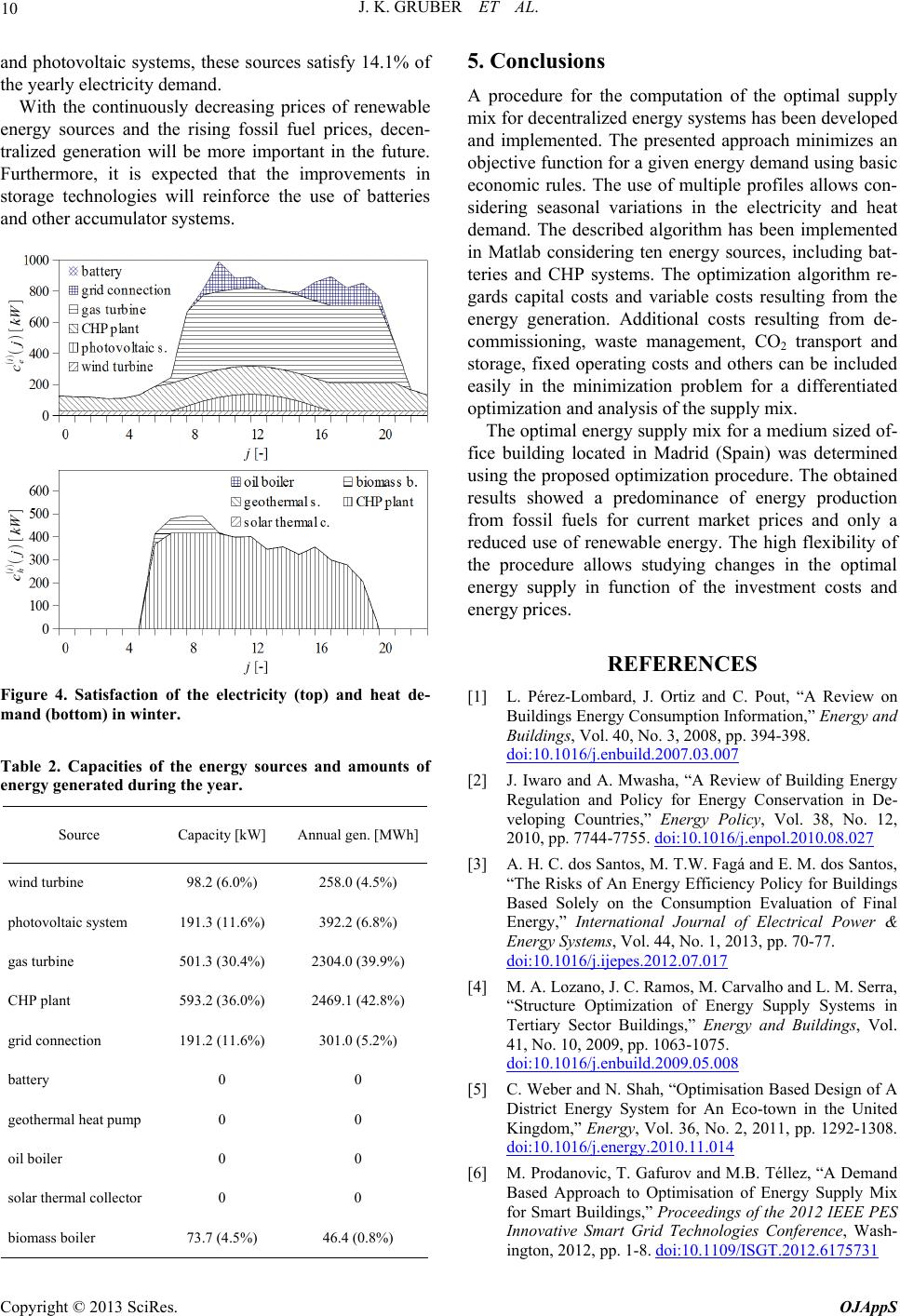

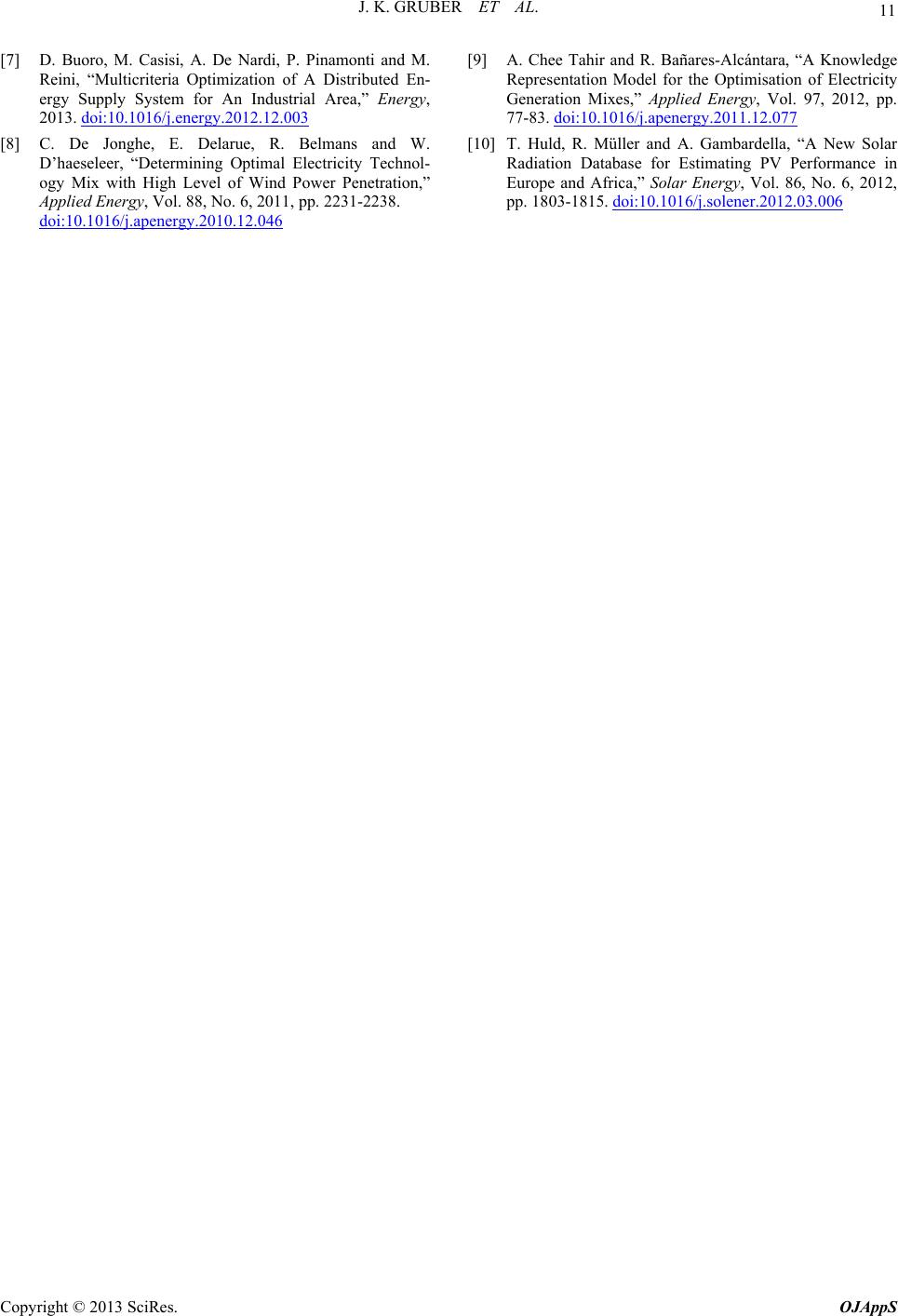

|