Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.10, 729-735 Published Online October 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.410103 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 729 The Role of Neuroticism in the Relation between Self-Esteem and Aggressive Emotion among 1085 Chinese Adolescents Zhaojun Teng1, Yanling Liu1,2* 1Research Center of Mental Health Education & Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing, China 2Key Laboratory for NeuroInformation of Ministry of Education & School of Life Science and Technology, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China Email: tzj450@swu.edu.cn, *ssq@swu.edu.cn Received July 24th, 2013; revised August 25th, 2013; accepted September 29th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Zhaojun Teng, Yanling Liu. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The present study aimed to reveal the role of neuroticism on the relationship between self-esteem and ag- gressive emotion. We conducted a cross-sectional study in which a battery of self-report questionnaires was used to assess self-esteem, neuroticism and aggressive emotion in 1085 Chinese adolescents (N = 1085, Mage = 16.38 years, 753 boys). We found that self-esteem could make a negative prediction of aggressive emo- tion both in males and females. And also, we found the mediating role of neuroticism was in both males and females, on the relations between self-esteem and aggressive emotion, especially, the moderating role of neuroticism among males in the aspect of relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotion. In conclusion, neuroticism was of importance for aggressive emotion, which was conducive to interventions. According to these findings, at the same time, implications and limitations were discussed in the content. Keywords: Self-Esteem; Aggressive Emotion; Neuroticism Introduction Aggression is thought to be predicted by individual personal- ity traits (e.g., self-esteem or the “Big 5” personality traits) that are influenced by emotions (e.g., anger or feelings of aggres- sion; Anderson, Anderson, & Deuser, 1996; Anderson, Deuser, & DeNeve, 1995; Bushman & Anderson, 2001). The General Aggression Model (GAM) posits that emotions, beliefs, and arousal interact to produce or inhibit aggressive behavior (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). Recently, a study with Chinese adolescents showed that they feel less happy and are less likely to employ strategies to regulate negative affect than adolescents of previous generations (Sang & Deng, 2010); this may be re- lated to the reported increase of aggressive emotions among Chinese adolescents (Liu & Zhu, 2010). Adolescents are also more likely to engage in vengeful acts (McCullough, Bellah, Kilpatrick, & Johnson, 2001). These findings suggested that aggressive emotions are affected by various factors, including personality traits and the external environment, as well as the complicated interaction between these factors, along with other constructs such as self-awareness and self-control. Because feelings of aggression are not always sufficient to produce aggressive behavior, predicting who will act out on their aggressive impulses requires investigating this interaction between personality and emotional variables. The present study focused on exploring the possible influence of neuroticism on the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotions. The current study found that neuroticism could be as mediator and moderator on relations between self-esteem and aggressive emotion in males, but only mediator in females. Self-esteem is an important part of a stable personality sys- tem. The relationship between self-esteem and aggression, however, is not clear. In addition, few studies have examined this issue, and those that have offer conflicting results. Accord- ing to one school of ego threat theory, people with low self- esteem are prone to aggression: researchers have shown that negative emotions among people with low self-esteem—such as depression, anxiety, and anger—may be predictive of ag- gression and violence (Lee & Hankin, 2009; Verona, Parick, & Lang, 2002). However, other researchers have proposed that people with high self-esteem are more aggressive (Donnellan, Trzesniewski, Robins, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2005) or that self- esteem and aggression are not related (Baumeister, Bushman, & Campbell, 2000; Thomaes, Bushman, de Castro, Cohen, & Denissen, 2009). Given this debate, empirical evidence of a possible relationship between aggression and self-esteem is necessary for the perspective of aggressive emotion. Some researchers have indicated that high self-esteem nega- tively predicts aggressive emotions, such as anger and hostility (for a review, see Arslan, 2009; Ostrowsky, 2010). However, there are discrepancies in existing results. For example, re- searchers have suggested that unstable high levels of self-es- teem strongly predict anger and hostility, that people with little anger and hostility have stable high levels of self-esteem, and that stability of high self-esteem predicts anger (Kernis, Gran- nemann, & Barclay, 1989; Waschull & Kernis, 1996). These studies seem to indicate that stability of self-esteem is a more important predictor of anger than level. However, a seven-year *Corresponding author.  Z. J. TENG, Y. L. LIU longitudinal study with children reported that declines in de- pression and anger predicted increases in self-esteem (Galam- bos, Barker, & Krahn, 2006). As can be seen, the relationship between self-esteem and ag- gressive emotions is complex. Recently, study samples have expanded from those composed of the general population to those including special groups, such as people with schizophre- nia spectrum disorders (Lysaker, Davis, & Tsai, 2009), sexually abused adolescents (Asgeirsdottir, Gudjonsson, Sigurdsson, & Sigfusdottir, 2010), and persons dependent on alcohol and other substances (Pekala, Kumar, Maurer, Elliott-Carter, & Moon, 2009). Studies with such samples have shown that high self-esteem can significantly predict low anger. In addition, researchers have found gender differences in the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotions, for example, females stronger positively correlation than males between those variables (Nunn & Thomas, 1999). In sum, despite the seeming importance of the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotion, the mechanisms underlying this relationship have not been adequately clarified, and the variables that may mediate or moderate this relationship have not yet been fully identified. Neuroticism is not only a crucial personality variable—being one of the Big 5—but it has also been shown to be positively correlated with aggressive emotions (Sharpe & Desai, 2001). Egan and Lewis (2011) found that affective aggression was predicted by neuroticism alone, whereas narcissistic aggression was underpinned by low agreeableness, extraversion, and per- ceived masculinity. With a general overview of previous re- search, we noted two points: 1) neuroticism may serve as a mediator in the relationships between self-esteem and aggres- sive emotion, and 2) neuroticism may serve as a moderator by directly affecting how self-esteem predicts aggressive emotion. Regarding the first point, neuroticism has been shown to positively predict negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, depression; Muris, Roelofs, Rassin, Franken, & Mayer, 2005). Persons with anxiety and depression tend to score high on instruments meas- uring neuroticism. It may be that neuroticism negatively pre- dicts subjective well-being by acting as a mediator between negative emotions and subjective well-being (Payne, 1988). Furthermore, research indicates that neuroticism is a mediator in the association between the serotonin transporter gene and lifetime major depression (Munafò, Clark, Roberts, & Johns- tone, 2006). Hence, neuroticism has usually been considered a mediating emotional variable. As to the second point, neuroticism may also play a moder- ating role as a personality variable. Persons with a high neurotic tendency tend to react excessively to threatening stimuli and feel nervous in all kinds of situations; consequently, they show poor emotion adjustment and experience rapid mood swings. Furthermore, neuroticism could be a moderator influencing the negative effects of stress on health (Jin & Su, 2009). Taking into consideration previous research (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Barlett & Anderson, 2012; Galambos et al., 2006; Kernis et al., 1989; Lee & Hankin, 2009; Liu & Zhu, 2010; Muris et al., 2005; Sharpe & Desai, 2001; Waschull & Kernis, 1996), and by referring to the GAM model (Anderson & Bushman, 2002) and ego threat theory (Baumeister et al., 2000; Baumeister, Smart, & Boden, 1966), we predicted a strong negative correlation between self-reported neuroticism and self-esteem, as well as a positive correlation between ag- gressive emotions and neuroticism. Finally, we hypothesized that neuroticism would be both a mediating and a moderating variable in the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotion. According to these hypotheses, we created the model shown in Figure 1. Methods Sample By a random group sampling method, a questionnaire was administered to 1300 students from seven Chinese high schools (Mage = 16.38 years, SD = 1.07; range: 15 - 18 years) located in the city of Chengdu in Sichuan province, and 1085 valid re- sponses were obtained (valid response rate: 83.46%). The sam- ple included 753 boys, 321 girls, and 11 students who did not provide gender information. Measures Self-Esteem Participants completed the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965), a ten-item self-report scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .83) scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“doesn’t describe me at all”) to 5 (“describes me completely”). A sample item is, “I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others.” The total score range of this scale is 0 to 50 points, with higher scores indicating higher explicit self-esteem. Neuroticism Participants completed only the neuroticism subscale of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975; Qian, Wu, Zhu, & Zhang, 2000). The Chinese version of this questionnaire, translated by Zhonggeng Chen (1983), has dem- onstrated sufficient reliability and validity. The neuroticism subscale consists of 24 yes/no items. Scores can range from 0 to 24 points, with higher scores indicating higher levels of neu- roticism. Aggressive Emotions Participants completed the anger and hostility subscales of the Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss and Perry, 1992) to measure aggressive emotions (Barlett & Anderson, 2012). The Chinese version of this questionnaire has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity in adolescents (Liu, Zhou, & Gu, 2009). The trait anger subscale contains Self-esteem × Neuroticism Neuroticism Self-esteem Aggressive emotion ( + ) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) Figure 1. A model of self-esteem, neuroticism, and aggressive emotion. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 730  Z. J. TENG, Y. L. LIU seven items (e.g., “I am sometimes eaten up by jealousy.” Cronbach’s alpha = .72) and the hostility subscale eight items (e.g., “When people are especially nice, I wonder what they want”; Cronbach’s alpha = .83). Procedure Students from the aforementioned seven high schools were randomly selected to receive the questionnaires. After giving informed consent, the students completed the questionnaires in their classrooms. The questionnaire took about ten minutes to complete. Data Analysis SPSS 16.0 for Windows and AMOS 7.0 software were used to analyze the data. First, we computed the correlations be- tween the three main variables—aggressive emotion (which contained trait anger and hostility; Barlett & Anderson, 2012), neuroticism, and self-esteem. The moderating effect of neuroti- cism was examined using hierarchical regression analysis (Wen, Hau, & Chang, 2005). The mediating effect of neuroticism on the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotion was analyzed via structural equation modeling, and various indices were used to evaluate model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Quintana & Maxwell, 1999). The indirect effect of neuroticism on self-esteem as a predictor of aggressive emotion was calcu- lated with a bootstrap estimation procedure (1000 reiterations). We used bootstrap estimation because we did not know the distribution of the indirect effects, even though the predictor variables followed a Gaussian distribution. Results Descriptive Statistics As reported in Table 1, aggressive emotions were signifi- cantly negatively correlated with self-esteem and significantly positively correlated with neuroticism for both male and female participants. Unexpectedly, female participants self-reported higher levels of aggressive emotion than did male participants (t = 4.63, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .3), but scored lower on self-esteem than did male participants (t = −2.46, p = .01, Cohen’s d = .2). Table 1. Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for all measures. 1 2 3 4 5 M (SD) 1. Trait anger - .46** .34 ** −.17** .85 ** 2.63 (.81) 2. Trait hostility .50** - .32 ** −.24** .85 ** 2.65 (.74) 3. Neuroticism .26** .25** - −.14** .39** 8.70 (2.45) 4. Self-esteem −.16** −.34** −.19** - −.23** 3.45 (.61) 5. Aggressive emotion .88** .85** .3 0 ** −.28** - 2.64 (.67) M (SD) 2.35 (.74) 2.54 (.73) 8.81 (2.67) 3.56 (.64) 2.44 (.63) - Note: Correlation coefficients for males (n = 753) are below the diagonal and correlation coefficients for females (n = 321) are above the diagonal. For males, values greater than .14 or less than −.14 were statistically significant (**p < .01). For females, values greater than .16 or less than −.16 were statistically significant (**p < .01). Mediating and Moderating Effects of Neuroticism The mediating effect of neuroticism is presented in Table 2. Sex was not found to mediate the effect of neuroticism. Neu- roticism partially mediated self-esteem and aggressive emotions for male participants, as the fit indices for Model C were supe- rior to those for the full-factor model (Model A, χ2(4, n = 753) = 134.87, p < .01) and the full-mediating-role model (Model B, χ2(3, n = 753) = 115.96, p < .01); for instance, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) for Model C was less than .08 and the SRMR was less than .05. Analogous results were found for female participants: the fit indices for Model F were superior to those for the full-factor (Model D, χ2(4, n = 321) = 139.62, p < .01) and full-mediating-role models (Model E, χ2(3, n = 321) = 109.43, p < .01); The RMSEA for Model F was less than .08 and the SRMR was less than .05. Hierarchical regression analysis was used to analyze the moderating effect of neuroticism (Table 3). For the hierarchical regression analysis, aggressive emotion was set as the depend- ent variable, and we entered self-esteem and neuroticism into the regression on the first step, and the interaction between self-esteem and neuroticism, for both males and females, on the second step. A significant moderating effect (p < .01) was found for male participants, but not for female participants (p > .10). To analyze the moderating effect found for the male partici- pants, we used a method devised by Aiken and West (1991): the sample was divided into a high self-esteem group (scoring at least one SD above the mean on the self-esteem scale) and a low self-esteem group (scoring at least one SD below the mean). The sample was then divided into a high neuroticism group and a low neuroticism group in the same manner (Figure 2). We found that male participants with low levels of neuroticism also had low levels of aggressive emotion, while those with high levels of neuroticism also had high levels of aggressive emotion, irrespective of levels of self-esteem. This result suggests that levels of neuroticism moderate the ability of self-esteem to predict aggressive emotions. Results Summary We used a mixed model to examine the mediating and mod- erating effects of neuroticism on the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotion (Figure 3). For male participants (Model X), neuroticism was found to have a mediating and moderating effect on the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotion, as determined 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 Low Self-esteemHigh Self-esteem Low Neuroticism High Neuroticism Figure 2. The moderating effect of neuroticism on the relationship be- tween self-esteem and aggressive emotion among males. (Note: The Y-axis shows the level of aggressive emotion). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 731  Z. J. TENG, Y. L. LIU Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 732 Table 2. Model fit indices for the effects of neuroticism on self-esteem and aggressive emotion. Gender Models χ2 df χ2/df NFI TLI CFI RMSEA SRMR Δχ2 Δdf Male Model A 270.55** 10 27.05 .93 .81 .93 .07 .10 Model B 135.68** 6 22.61 .87 .63 .88 .10 .04 134.87 4 Model C 19.71** 3 6.56 .98 .90 .98 .05 .03 115.96 3 Female Model D 271.61** 10 27.16 .91 .76 .92 .08 .11 Model E 131.99** 6 21.99 .85 .55 .85 .11 .04 139.62 4 Model F 22.56** 3 7.52 .97 .86 .97 .06 .04 109.43 3 Note: Models A, B, and C show sample indices for male participants, and Models D, E, and F show those for female participants. Models A and D: the full-factor models for self-esteem, neuroticism, and aggressive emotion (no mediating effect of neuroticism). Models B and E: the full mediating effect of neuroticism on self-esteem as a predictor of aggressive emotion. Models C and F: the partial mediating effect of neuroticism on self-esteem as a predictor of aggressive emotion. NFI, normed fit index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis index; CFI, comparative fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual (**p < .01). Table 3. Hierarchical regression analysis of the predictive relationship of aggressive emotion by self-esteem and neuroticism, separated by gender. Gender Independent variable ΔR2 β t p Male Self-esteem .06 −.20 −5.93 p < .01 Neuroticism .13 .38 11.41 p < .01 Self-esteem × Neuroticism .02 .10 2.95 p < .01 Female Self-esteem .08 −.24 −4.54 p < .01 Neuroticism .06 .26 4.86 p < .01 Self-esteem × Neuroticism .01 .07 1.42 p = .15 Note: Self-esteem × Neuroticism indicates the interaction of self-esteem and neuroticism variables. Model X Model Y Self-esteem × Neuroticism Neuroticism Self-esteem Aggressive emotion .09 −.57 −.18 .09 Self-esteem × Neuroticism Neuroticism Self-esteem Aggressive emotion .08 −.78 −.25 .07 Figure 3. Results of the mixed model analysis for the model of self-esteem, neuroticism, and aggressive emotion. Model X shows results for male partici- pants, and Model Y shows the results for female participants. Solid lines indicate significant effects (**p < .01), while the dashed line indicates a non-significant effect (p > .05). with the Preacher and Hayes (2004) method. Self-esteem sig- nificantly predicted neuroticism (β = −.57, p < .01), neuroticism significantly predicted aggressive emotions (β = .09, p < .01), and self-esteem significantly predicted aggressive emotions (β = −.18, p < .01). A bootstrap estimation procedure (1000 reit- erations) found significant direct and mediating effects of self-esteem and neuroticism on aggressive emotion, as well as an indirect effect (−.05, p < .01, 95% confidence interval [−.09, −.02]). The indirect to total effect ratio was .27, which implies that the indirect effect of neuroticism was 27%. We also found an interaction between self-esteem and neuroticism (β = .09, p < .01), which implies that the moderating effect of neuroticism significantly predicted aggressive emotions by self-esteem. For female participants (Model Y), neuroticism was found to have only a mediating effect on the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotions. Self-esteem significantly predicted neuroticism (β = −.78, p < .01), and neuroticism pre- dicted aggressive emotions (β = .08, p < .05). A bootstrap esti- mation procedure (1000 reiterations) found that self-esteem had a significant direct predictive effect on aggressive emotions (β = −.25, p < .01) as well as an indirect effect (−.06, p < .01, 95% confidence interval [−.10, −.02]), indicating a substantial me- diator effect. The interaction between self-esteem and neuroti- cism was not significant (β = .07, p > .05), which suggests the absence of a moderator effect of neuroticism for female par- ticipants.  Z. J. TENG, Y. L. LIU Discussion This study demonstrates a relationship between the two per- sonality variables of self-esteem and neuroticism and the emo- tional variable of aggressive emotions. Our analysis revealed both a mediating and moderating role of neuroticism in the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotions for male adolescents, but only a mediating effect for female ado- lescents. Variables can act as both mediators and moderators simulta- neously (Cui & Conger, 2008)—in other words, a third variable can have both a mediating and a moderating effect on the rela- tions between independent variables and dependent variables when this variable also has an strong influence on the depend- ent variables (MacKinnon & Fairchild, 2009). Neuroticism predicted the level of aggressive emotion, consistent with pre- vious findings (e.g., Sharpe & Desai, 2001) and mediated the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotion. This finding extends existing evidence on the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive behavior. Aggressive emotions were previously considered to directly produce aggressive behavior (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Barlett & Anderson, 2012), but the present study suggests that neuroticism has an important role in this pathway. Furthermore, the lack of a moderating role of neuroticism in the relationship between self-esteem and ag- gressive emotions for our female participants implies that gen- der plays an important role in the moderating effects of neuroti- cism. This paper presents evidence that favors the theory that low self-esteem might produce aggressive behavior due to aggres- sive emotions (Donnellan et al., 2005). Participants with low self-esteem are prone to high levels of self-abasement and de- pression (Cong, Tian, & Zhang, 2005). They are often reclusive, with little confidence to act even though they feel the need to protect themselves when their self-esteem is threatened. People with low self-esteem easily fall prey to aggressive emotions such as anger and hostility. However, in some people with low self-esteem, negative emotions take the place of aggressive behavior. Hence, we could conclude that some emotional vari- able (e.g., neuroticism) is necessary to activate aggressive be- havior in people with low self-esteem. Self-esteem predicted aggressive emotions for both male and female participants, and this was partially mediated by neuroti- cism. Neuroticism functions as both a personality and an emo- tional variable, and from the personality perspective, neuroti- cism is stable and not easily changed. Neuroticism, therefore, could also play a moderating role in the relationship between aggressive emotion and self-esteem. However, for our female participants, no moderating effect was found. This implies that the personality and emotional functions of neuroticism could have an interactive effect on people’s actions in daily life. The behavior of women is thought to be more affected by emotion. Our finding a mediating effect, but no moderating effect, of neuroticism on the relationship between self-esteem and ag- gressive emotion may indicate that neuroticism functioned as an emotional variable more than as a personality variable among our female sample. Additionally, the fact that the male students did present a moderating effect of neuroticism on ag- gressive emotion and self-esteem suggests that they are more prone to action than female students. However, we must note that it is possible that the sample size for female participants was not large enough to detect an existing moderator effect. As mentioned previously, neuroticism is an emotional vari- able because it highly linked to emotional information process- ing. People with high scores on the neuroticism scale have con- stantly changing moods; hence, previous research has consid- ered it as a potential mediator in a variety of cognitive-emo- tional relationships. Aggressive people usually exhibit negative emotions (e.g., anger or sadness), both of which are strongly linked to aggression (Lee & Hankin, 2009; Stucke & Sporer, 2002; Verona et al., 2002). Thus, we conclude that neuroticism might mediate the relationship between personality variables (e.g., self-esteem) and emotion variables (e.g., aggressive emo- tion). Even though this study revealed the role of neuroticism in self-esteem and aggressive emotions, no interaction between aggressive emotion and self-esteem was found. However, we did not explore the relationship between implicit self-esteem and aggressive emotion, which has been widely examined in previous research (Baccus, Baldwin, & Packer, 2004; Schröder-Abé, Rudolph, & Schütz, 2007). The relationship between implicit self-esteem and aggression has already been well explored. For instance, research has shown that implicit and explicit self-esteem might influence aggressive behaviors (Thomaes & Bushman, 2011), and implicit self-esteem could be considered a mediator in the relationship between self-en- hancement and explicit self-esteem (Bosson, Brown, Zeigler- Hill, & Swann, 2003). Therefore, the relationship between im- plicit and explicit self-esteem and aggressive emotion requires further explanation. Future research could also examine whether neuroticism plays a mediating or moderating role in such relationships. Another limitation of the present study concerns its correla- tional design and use of questionnaires. To our knowledge, no research has explored the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotion using an experimental design, which would allow direct testing of the mediating and moderating effects of neuroticism. This point should be addressed in future research. The final limitation concerns the use of Rosenberg’s Self-esteem Scale, which has only ten items. This might have affected the generalizability of our conclusion that self-esteem negatively predicts aggressive emotion. Considering the various types of self-esteem, it is difficult to measure self-esteem ac- cordingly, which might be why the relationship between self-esteem and aggression has not been made clear (Ostrowsky, 2010). Furthermore, it would be worthwhile to investigate the relationships among ego, self-awareness, and aggressive emo- tion in future studies. To further explore the relationship be- tween self-esteem and aggressive emotion, comprehensive assessments utilizing diverse paradigms should be performed. In this regard, further cross-sectional and longitudinal research would be useful. Conclusions This paper revealed that neuroticism had a mediating and moderating effect on the relationship between self-esteem and aggressive emotion for males, but only a mediating effect for females. For male participants, low or high levels of neuroti- cism were associated with low or high levels of aggressive emotion, respectively, regardless of levels of self-esteem. A result suggests that neuroticism moderates the ability of self-esteem to predict aggressive emotions. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 733  Z. J. TENG, Y. L. LIU Acknowledgements This study was supported by the fund of Construction Re- search Team of Project “Effect of Network Media on the Ag- gression of Youth and Its Neural Mechanism” at Faculty of Psychology of SWU (TR201204-5). REFERENCES Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions (pp. 28-61). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Anderson, C. A., Anderson, K. B., & Deuser, W. E. (1996). Examining an affective aggression framework: Weapon and temperature effects on aggressive thoughts, affect, and attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 366-376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167296224004 Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 27-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231 Anderson, C. A., Deuser, W. E., & DeNeve, K. M. (1995). Hot tem- peratures, hostile affect, hostile cognition, and arousal: Tests of a general model of affective aggression. Personality and Social Psy- chology Bulletin, 21, 434-448. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167295215002 Arslan, C. (2009). Anger, self-esteem, and perceived social support in adolescence. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 37, 555-564. http://dx.doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2009.37.4.555 Asgeirsdottir, B. B., Gudjonsson, G. H., Sigurdsson, J. F., & Sigfusdot- tir, I. D. (2010). Protective processes for depressed mood and anger among sexually abused adolescents: The importance of self-esteem. Personality and Individu a l Differences, 49, 402-407. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.04.007 Baccus, J. R., Baldwin, M. W., & Packer, D. J. (2004). Increasing im- plicit self-esteem through classical conditioning. Psychological Sci- ence, 15, 498-502. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00708.x Barlett, C. P., & Anderson, C. A. (2012). Direct and indirect relations between the Big 5 personality traits and aggressive and violent be- havior. Personality an d Individual Differen c e s , 52, 870-875. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.01.029 Baumeister, R. F., Bushman, B. J., & Campbell, W. K. (2000). Self- esteem, narcissism, and aggression does violence result from low self-esteem or from threatened egotism? Current Directions in Psy- chological Science, 9, 26-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00053 Bosson, J. K., Brown, R. P., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Swann Jr., W. B., (2003). Self-enhancement tendencies among people with high ex- plicit self-esteem: The moderating role of implicit self-esteem. Self and Identity, 2, 169-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15298860309029 Bushman, B. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2001). Is it time to pull the plug on hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychological Review, 108, 273-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.1.273 Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Socia l Psychology, 63, 452-459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452 Chen, Z. (1983). Item analysis of Eysenck personality questionnaire tested in Beijing district. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 15, 211-218. Cong, X., Tian, L., & Zhang, X. (2005). Self-esteem: The core of men- tal health. Journal of Northeast Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 31, 144-148. Cui, M., & Conger, R. D. (2008). Parenting behavior as mediator and moderator of the association between marital problems and adoles- cent maladjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18, 261- 284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00560.x Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2005). Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychological Science, 16, 328-335. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01535.x Egan, V., & Lewis, M. (2011). Neuroticism and agreeableness differen- tiate emotional and narcissistic expressions of aggression. Personal- ity and Individual Differences, 50, 845-850. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.007 Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1975). Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (junior and adult). London: Hodder and Stoughton. Galambos, N. L., Barker, E. T., & Krahn, H. J. (2006). Depression, self-esteem, and anger in emerging adulthood: Seven-year trajecto- ries. Developmental Psychology, 42, 350-365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.350 Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in co- variance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alterna- tives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 Jin, J., & Su, Y. (2009). The effect of neuroticism on health: The role of stress and health related behaviors. Journal of Southwest University (Social Science Edition), 35, 5-10. Kernis, M. H., Grannemann, B. D., & Barclay, L. C. (1989). Stability and level of self-esteem as predictors of anger arousal and hostility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 1013-1022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.6.1013 Lee, A., & Hankin, B. L. (2009). Insecure attachment, dysfunctional attitudes, and low self-esteem predicting prospective symptoms of depression and anxiety during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38, 219-231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374410802698396 Liu, H. & Zhu, L. (2010). Happen and expression of anger in teenagers. Chinese Journal of School Health, 31, 1288-1290. Liu, J., Zhou, Y., & Gu, W. (2009). Reliability and validity of Chinese version of buss-perry aggression questionnaire in adolescents. Chi- nese Journal of Clinical P syc ho lo gy , 17, 449-451. Lysaker, P. H., Davis, L. W., & Tsai, J. (2009). Suspiciousness and low self-esteem as predictors of misattributions of anger in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Research, 166, 125-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.03.014 MacKinnon, D. P., & Fairchild, A. J. (2009). Current directions in me- diation analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 16-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x McCullough, M. E., Bellah, C. G., Kilpatrick, S. D., & Johnson, J. L. (2001). Vengefulness: Relationships with forgiveness, rumination, well-being, and the Big Five. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 601-610. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167201275008 Munafò, M. R., Clark, T. G., Roberts, K. H., & Johnstone, E. C. (2006). Neuroticism mediates the association of the serotonin transporter gene with lifetime major depression. Neuropsychobiology, 53, 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000089915 Muris, P., Roelofs, J., Rassin, E., Franken, I., & Mayer, B. (2005). Mediating effects of rumination and worry on the links between neuroticism, anxiety and depression. Personality and Individual Dif- ferences, 39, 1105-1111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.04.005 Nunn, J. S., & Thomas, S. L. (1999). The angry male and the passive female: The role of gender and self-esteem in anger expression. So- cial Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 27, 145- 153. http://dx.doi.org/10.2224/sbp.1999.27.2.145 Ostrowsky, M. K. (2010). Are violent people more likely to have low self-esteem or high self-esteem? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 69-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.004 Payne, R. (1988). A longitudinal study of the psychological well-being of unemployed men and the mediating effect of neuroticism. Human Relations, 41, 119-138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/001872678804100203 Pekala, R. J., Kumar, V. K., Maurer, R., Elliott-Carter, N. C., & Moon, E. (2009). Self-esteem and its relationship to serenity and anger/im- pulsivity in an alcohol and other drug-dependent population. Implica- tions for Treatment. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 27, 94-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07347320802587005 Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Re- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 734  Z. J. TENG, Y. L. LIU Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 735 search Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717-731. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553 Qian, M., Wu, G., Zhu, R., & Zhang, S. (2000). Development of the revision Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Short Scale for Chinese (EPQ-RSC). ActaPsychologica Sinica, 32, 317-323. Quintana, S.M., & Maxwell, S.E. (1999). Implications of recent devel- opment in structural equation modeling for counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 27 , 485-527. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011000099274002 Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Sang, B., & Deng, X. (2010). Emotion development of Chinese ado- lescents under the social change. Psychological Development and Education, 26, 549-553. Schröder-Abé, M., Rudolph, A., & Schütz, A. (2007). High implicit self-esteem is not necessarily advantageous: discrepancies between explicit and implicit self-esteem and their relationship with anger expression and psychological health. European Journal of Personal- ity, 21, 319-339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/per.626 Sharpe, J. P., & Desai, S. (2001). The revised Neo Personality Inven- tory and the MMPI-2 Psychopathology Five in the prediction of ag- gression. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 505-518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00155-0 Stucke, T. S., & Sporer, S. L. (2002). When a grandiose self-image is threatened: Narcissism and self-concept clarity as predictors of nega- tive emotions and aggression following ego-threat. Journal of Per- sonality, 70, 509-532. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.05015 Thomaes, S., & Bushman, B. J. (2011). Mirror, mirror, on the wall, who’s the most aggressive of them all? Narcissism, self-esteem, and aggression. In P. R. Shaver, & M. Mikulincer (Eds.), Human ag- gression and violence. CAUSES, manifestations, and consequences (pp. 203-219). Washington, DC: American Psychological Associa- tion. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/12346-011 Thomaes, S., Bushman, B. J., de Castro, B. O., Cohen, G. L., & Denis- sen, J. J. A. (2009). Reducing narcissistic aggression by buttressing self-esteem: An experimental field study. Psychological Science, 20, 1536-1542. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02478.x Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Show your pride evidence for a discrete emotion expression. Psychological Science , 15, 194-197. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.01503008.x Verona, E., Patrick, C. J., & Lang, A. R. (2002). A direct assessment of the role of state and trait negative emotion in aggressive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 249-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.111.2.249 Waschull, S. B., & Kernis, M. H. (1996). Level and stability of self- esteem as predictors of children’s intrinsic motivation and reasons for anger. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 4-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167296221001 Wen, Z., Hau, K. T., & Chang, L. (2005). A comparison of moderator and mediator and their applications. ActaPsychologica Sinica, 37, 268-274.

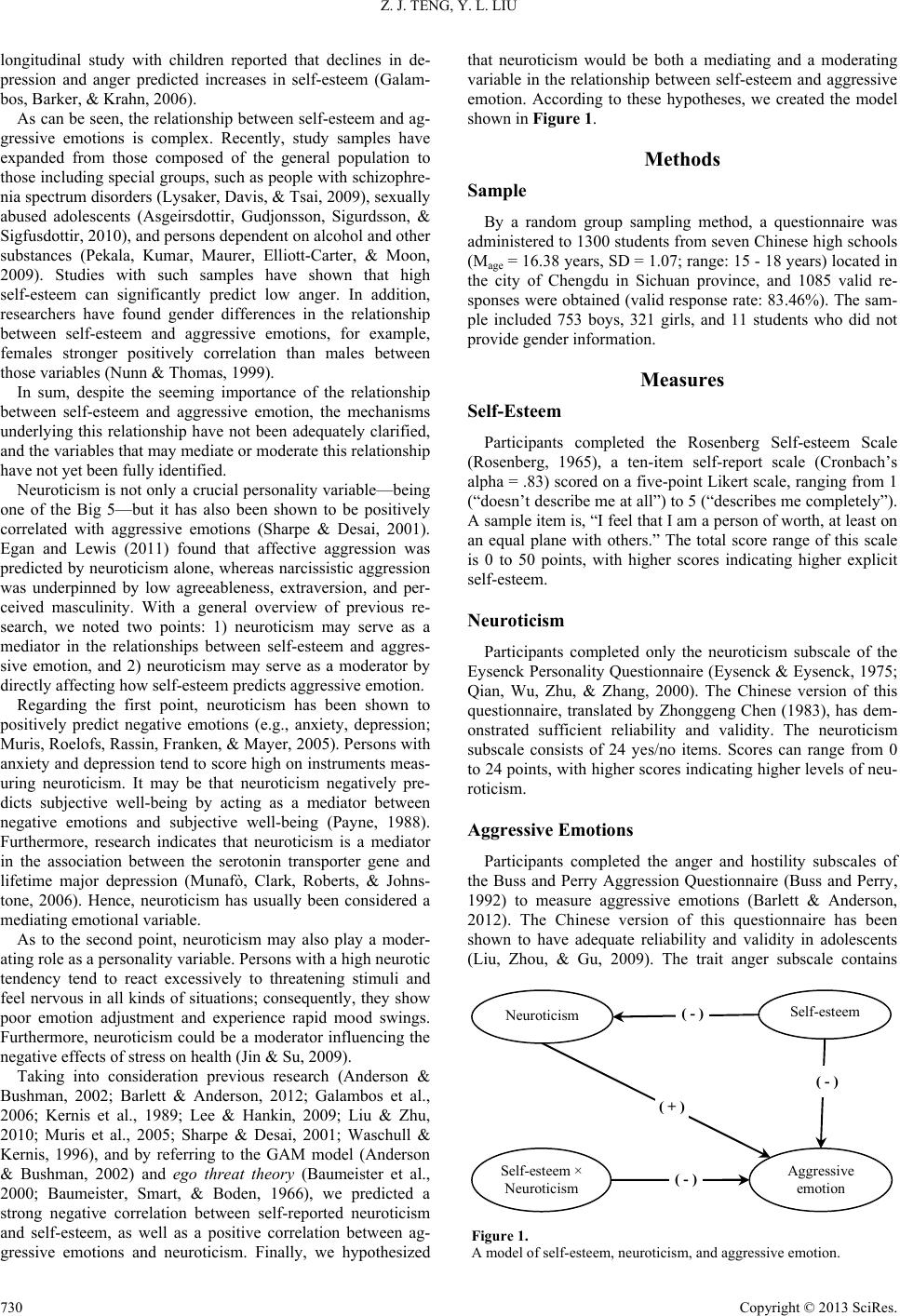

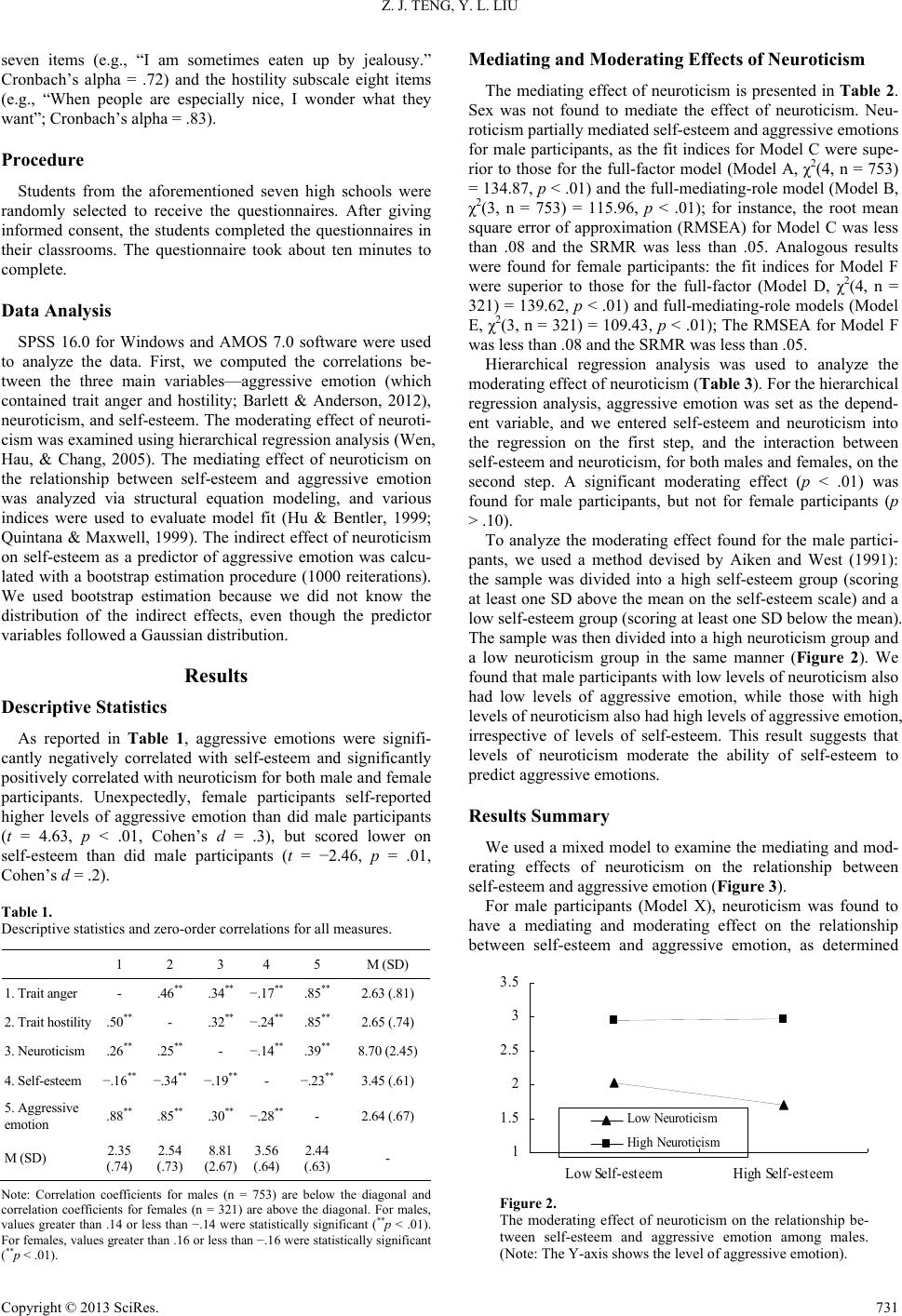

|