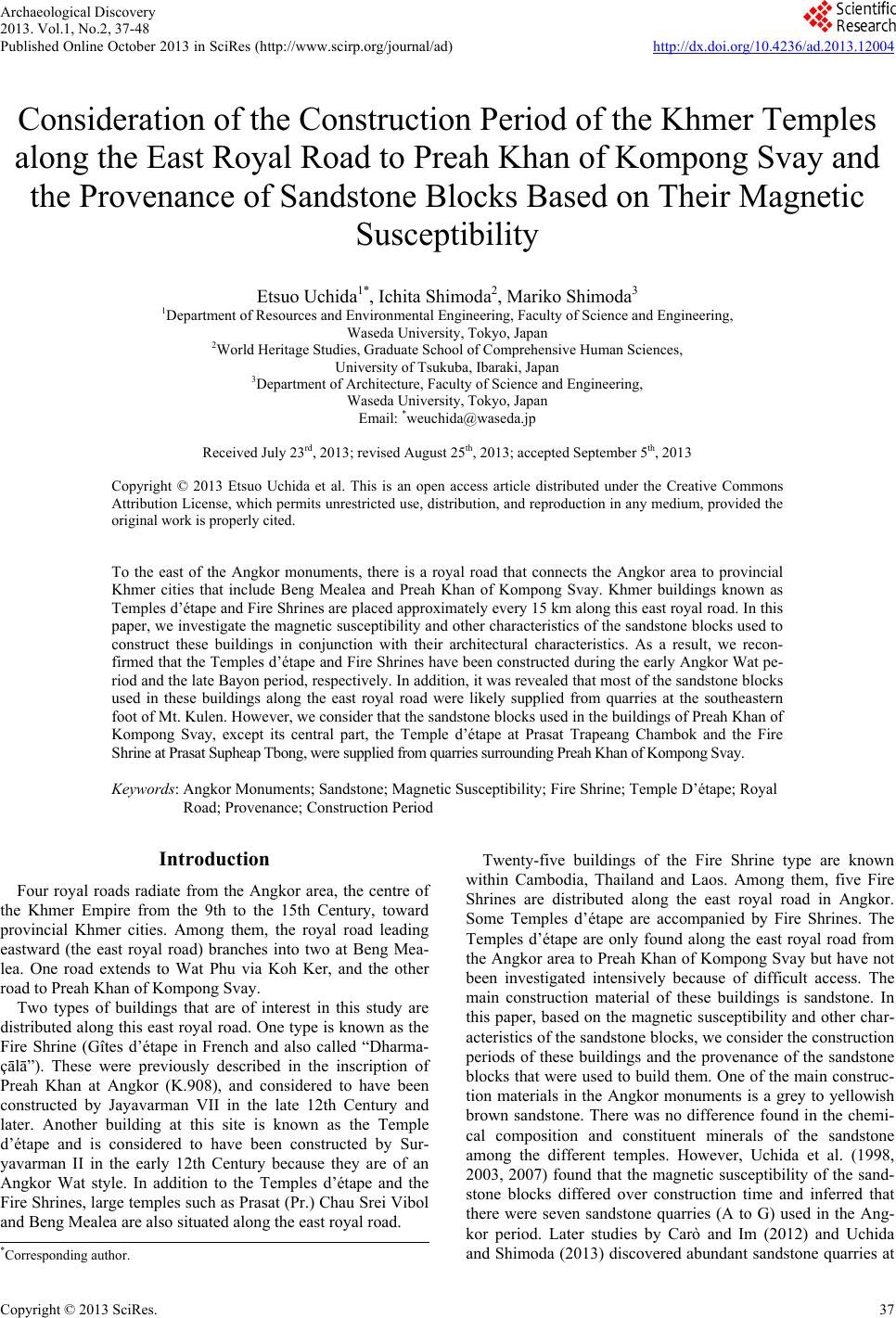

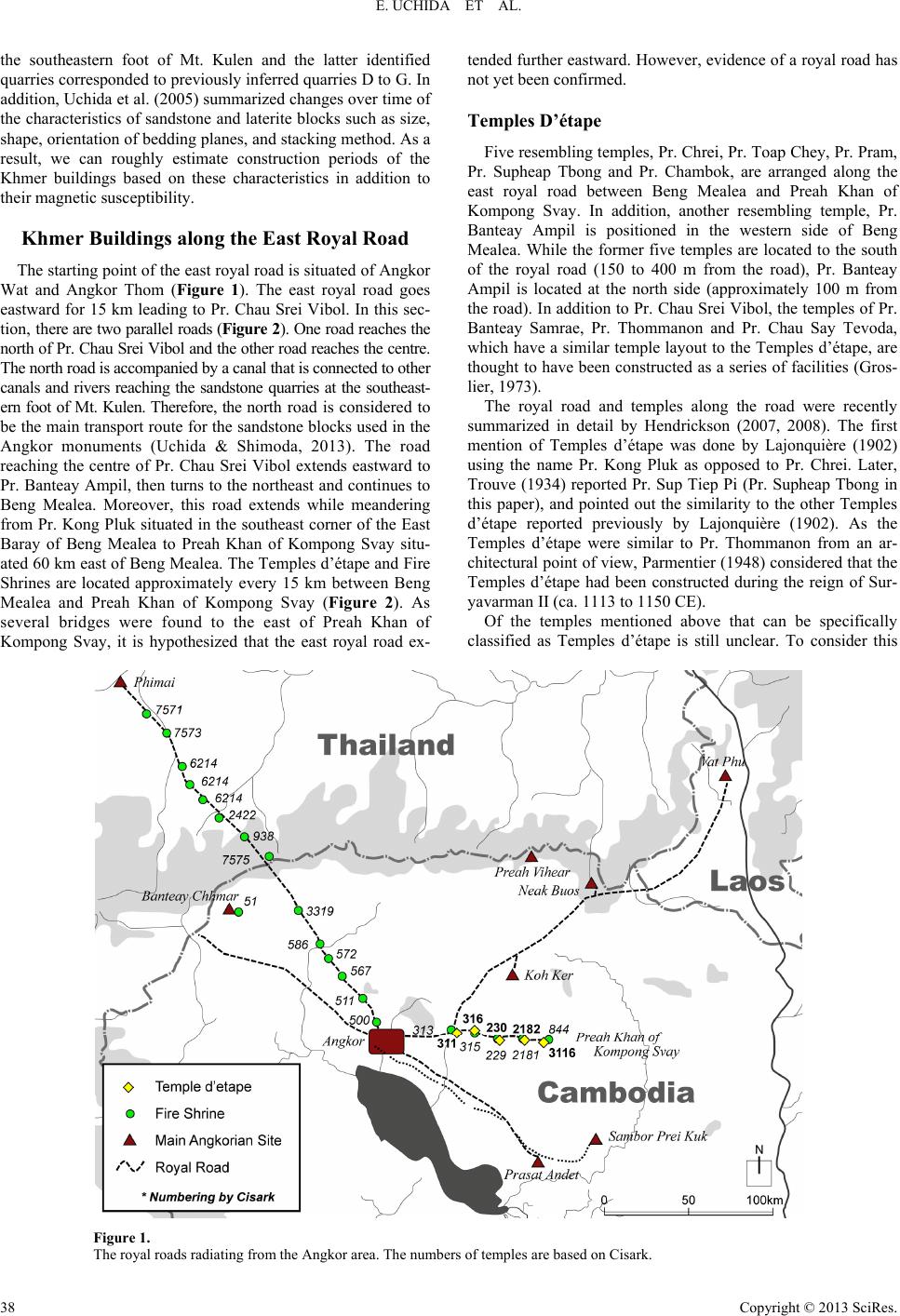

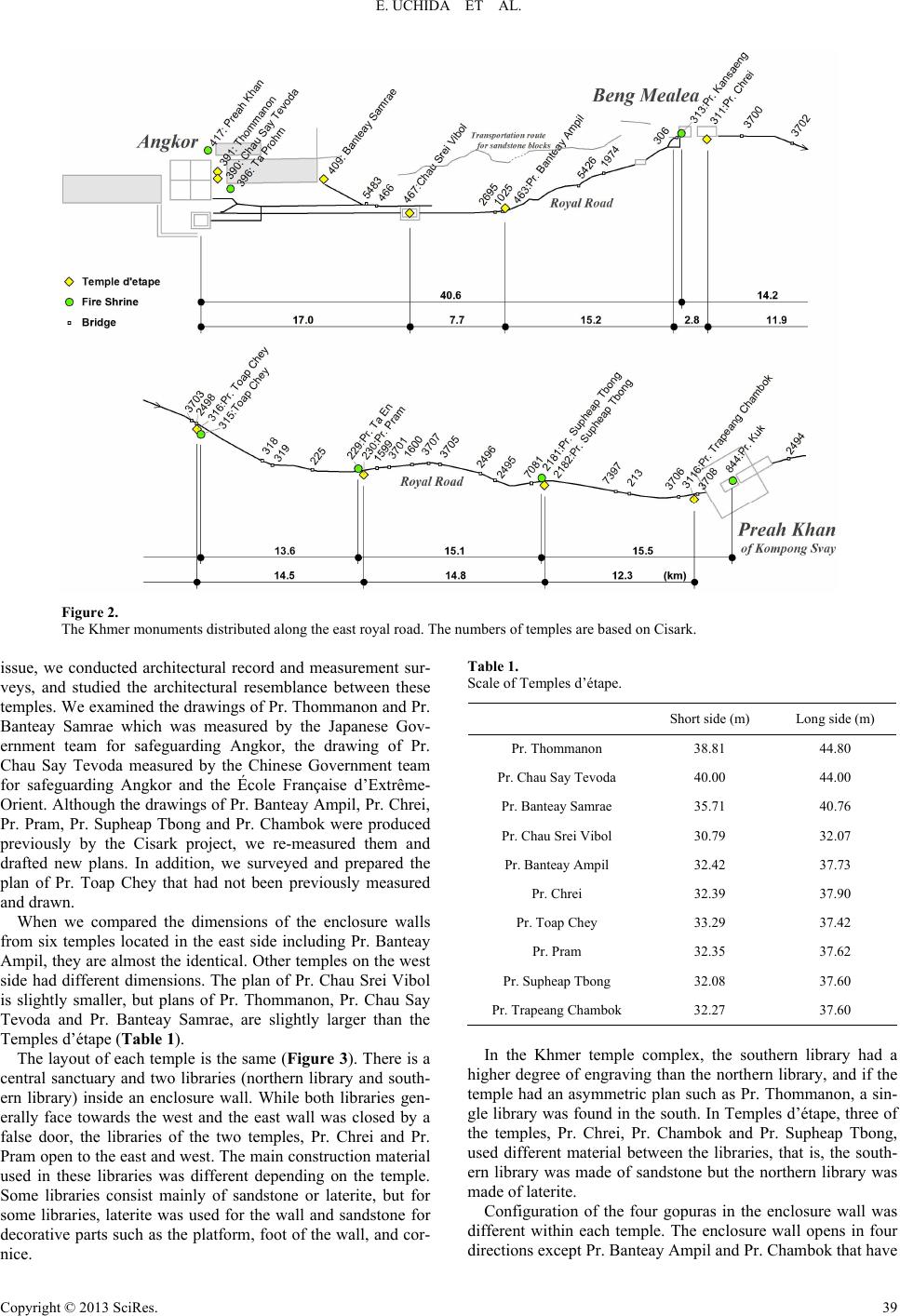

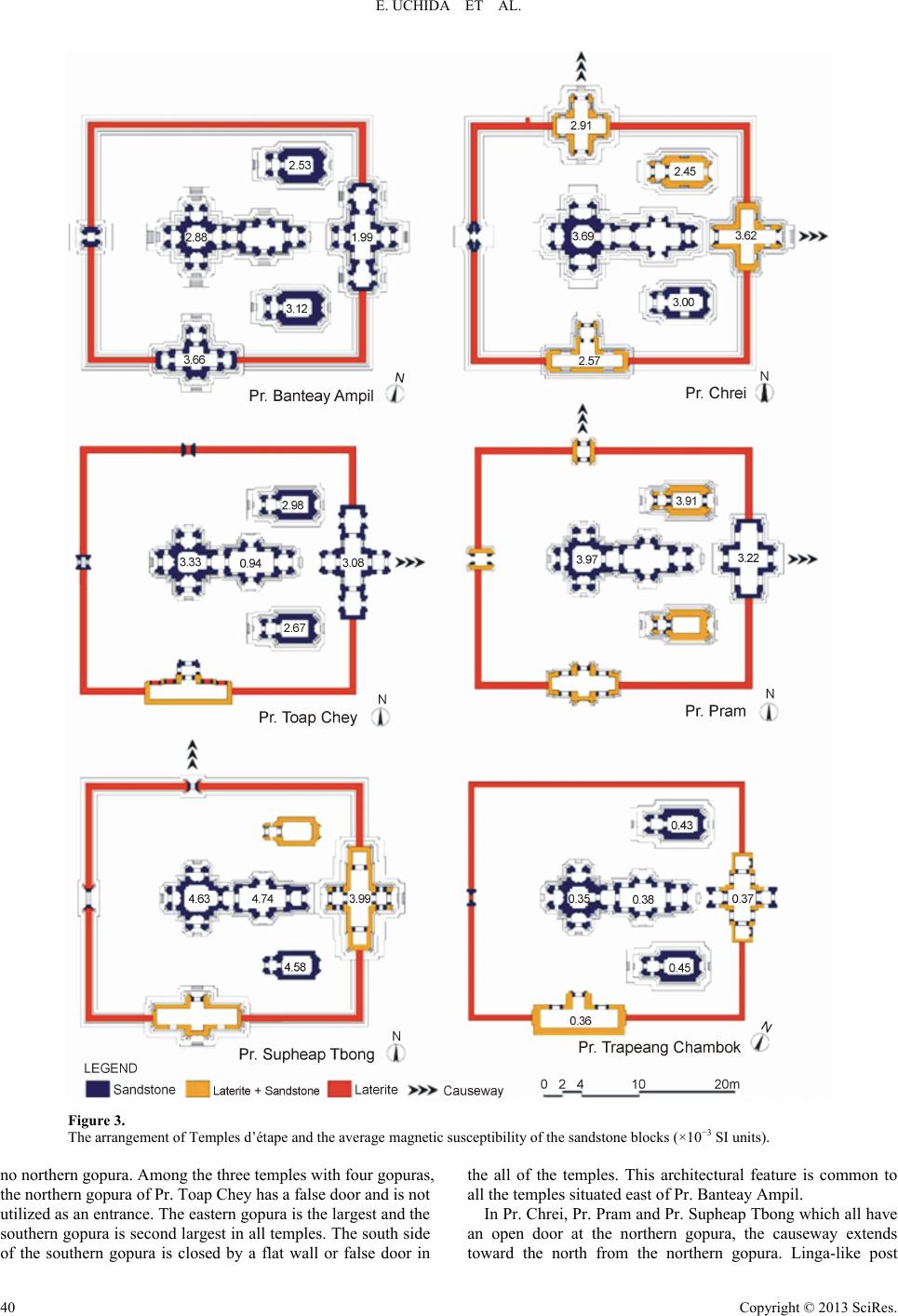

Archaeological Discovery 2013. Vol.1, No.2, 37-48 Published Online October 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ad) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ad.2013.12004 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 37 Consideration of the Construction Period of the Khmer Temples along the East Royal Road to Preah Khan of Kompong Svay and the Provenance of Sandstone Blocks Based on Their Magnetic Susceptibility Etsuo Uchida1*, Ichita Shimoda2, Mariko Shimoda3 1Department of Resources and Environmental Engineering, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan 2World Heritage Studies, Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan 3Department of Architecture, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan Email: *weuchida@waseda.jp Received July 23rd, 2013; revised August 25th, 2013; accepted September 5th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Etsuo Uchida et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. To the east of the Angkor monuments, there is a royal road that connects the Angkor area to provincial Khmer cities that include Beng Mealea and Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. Khmer buildings known as Temples d’étape and Fire Shrines are placed approximately every 15 km along this east royal road. In this paper, we investigate the magnetic susceptibility and other characteristics of the sandstone blocks used to construct these buildings in conjunction with their architectural characteristics. As a result, we recon- firmed that the Temples d’étape and Fire Shrines have been constructed during the early Angkor Wat pe- riod and the late Bayon period, respectively. In addition, it was revealed that most of the sandstone blocks used in these buildings along the east royal road were likely supplied from quarries at the southeastern foot of Mt. Kulen. However, we consider that the sandstone blocks used in the buildings of Preah Khan of Kompong Svay, except its central part, the Temple d’étape at Prasat Trapeang Chambok and the Fire Shrine at Prasat Supheap Tbong, were supplied from quarries surrounding Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. Keywords: Angkor Monuments; Sandstone; Magnetic Susceptibility; Fire Shrine; Temple D’étape; Royal Road; Provenance; Construction Period Introduction Four royal roads radiate from the Angkor area, the centre of the Khmer Empire from the 9th to the 15th Century, toward provincial Khmer cities. Among them, the royal road leading eastward (the east royal road) branches into two at Beng Mea- lea. One road extends to Wat Phu via Koh Ker, and the other road to Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. Two types of buildings that are of interest in this study are distributed along this east royal road. One type is known as the Fire Shrine (Gîtes d’étape in French and also called “Dharma- çālā”). These were previously described in the inscription of Preah Khan at Angkor (K.908), and considered to have been constructed by Jayavarman VII in the late 12th Century and later. Another building at this site is known as the Temple d’étape and is considered to have been constructed by Sur- yavarman II in the early 12th Century because they are of an Angkor Wat style. In addition to the Temples d’étape and the Fire Shrines, large temples such as Prasat (Pr.) Chau Srei Vibol and Beng Mealea are also situated along the east royal road. Twenty-five buildings of the Fire Shrine type are known within Cambodia, Thailand and Laos. Among them, five Fire Shrines are distributed along the east royal road in Angkor. Some Temples d’étape are accompanied by Fire Shrines. The Temples d’étape are only found along the east royal road from the Angkor area to Preah Khan of Kompong Svay but have not been investigated intensively because of difficult access. The main construction material of these buildings is sandstone. In this paper, based on the magnetic susceptibility and other char- acteristics of the sandstone blocks, we consider the construction periods of these buildings and the provenance of the sandstone blocks that were used to build them. One of the main construc- tion materials in the Angkor monuments is a grey to yellowish brown sandstone. There was no difference found in the chemi- cal composition and constituent minerals of the sandstone among the different temples. However, Uchida et al. (1998, 2003, 2007) found that the magnetic susceptibility of the sand- stone blocks differed over construction time and inferred that there were seven sandstone quarries (A to G) used in the Ang- kor period. Later studies by Carò and Im (2012) and Uchida and Shimoda (2013) discovered abundant sandstone quarries at *Corresponding author.  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 38 the southeastern foot of Mt. Kulen and the latter identified quarries corresponded to previously inferred quarries D to G. In addition, Uchida et al. (2005) summarized changes over time of the characteristics of sandstone and laterite blocks such as size, shape, orientation of bedding planes, and stacking method. As a result, we can roughly estimate construction periods of the Khmer buildings based on these characteristics in addition to their magnetic susceptibility. Khmer Buildings along the East Royal Road The starting point of the east royal road is situated of Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom (Figure 1). The east royal road goes eastward for 15 km leading to Pr. Chau Srei Vibol. In this sec- tion, there are two parallel roads (Figure 2). One road reaches the north of Pr. Chau Srei Vibol and the other road reaches the centre. The north road is accompanied by a canal that is connected to other canals and rivers reaching the sandstone quarries at the southeast- ern foot of Mt. Kulen. Therefore, the north road is considered to be the main transport route for the sandstone blocks used in the Angkor monuments (Uchida & Shimoda, 2013). The road reaching the centre of Pr. Chau Srei Vibol extends eastward to Pr. Banteay Ampil, then turns to the northeast and continues to Beng Mealea. Moreover, this road extends while meandering from Pr. Kong Pluk situated in the southeast corner of the East Baray of Beng Mealea to Preah Khan of Kompong Svay situ- ated 60 km east of Beng Mealea. The Temples d’étape and Fire Shrines are located approximately every 15 km between Beng Mealea and Preah Khan of Kompong Svay (Figure 2). As several bridges were found to the east of Preah Khan of Kompong Svay, it is hypothesized that the east royal road ex- tended further eastward. However, evidence of a royal road has not yet been confirmed. Temples D’étape Five resembling temples, Pr. Chrei, Pr. Toap Chey, Pr. Pram, Pr. Supheap Tbong and Pr. Chambok, are arranged along the east royal road between Beng Mealea and Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. In addition, another resembling temple, Pr. Banteay Ampil is positioned in the western side of Beng Mealea. While the former five temples are located to the south of the royal road (150 to 400 m from the road), Pr. Banteay Ampil is located at the north side (approximately 100 m from the road). In addition to Pr. Chau Srei Vibol, the temples of Pr. Banteay Samrae, Pr. Thommanon and Pr. Chau Say Tevoda, which have a similar temple layout to the Temples d’étape, are thought to have been constructed as a series of facilities (Gros- lier, 1973). The royal road and temples along the road were recently summarized in detail by Hendrickson (2007, 2008). The first mention of Temples d’étape was done by Lajonquière (1902) using the name Pr. Kong Pluk as opposed to Pr. Chrei. Later, Trouve (1934) reported Pr. Sup Tiep Pi (Pr. Supheap Tbong in this paper), and pointed out the similarity to the other Temples d’étape reported previously by Lajonquière (1902). As the Temples d’étape were similar to Pr. Thommanon from an ar- chitectural point of view, Parmentier (1948) considered that the Temples d’étape had been constructed during the reign of Sur- yavarman II (ca. 1113 to 1150 CE). Of the temples mentioned above that can be specifically classified as Temples d’étape is still unclear. To consider this Figure 1. The royal roads radiating from the Angkor area. The numbers of temples are based on Cisark.  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 39 Figure 2. The Khmer monuments distributed along the east royal road. The numbers of temples are based on Cisark. issue, we conducted architectural record and measurement sur- veys, and studied the architectural resemblance between these temples. We examined the drawings of Pr. Thommanon and Pr. Banteay Samrae which was measured by the Japanese Gov- ernment team for safeguarding Angkor, the drawing of Pr. Chau Say Tevoda measured by the Chinese Government team for safeguarding Angkor and the École Française d’Extrême- Orient. Although the drawings of Pr. Banteay Ampil, Pr. Chrei, Pr. Pram, Pr. Supheap Tbong and Pr. Chambok were produced previously by the Cisark project, we re-measured them and drafted new plans. In addition, we surveyed and prepared the plan of Pr. Toap Chey that had not been previously measured and drawn. When we compared the dimensions of the enclosure walls from six temples located in the east side including Pr. Banteay Ampil, they are almost the identical. Other temples on the west side had different dimensions. The plan of Pr. Chau Srei Vibol is slightly smaller, but plans of Pr. Thommanon, Pr. Chau Say Tevoda and Pr. Banteay Samrae, are slightly larger than the Temples d’étape (Table 1). The layout of each temple is the same (Figure 3). There is a central sanctuary and two libraries (northern library and south- ern library) inside an enclosure wall. While both libraries gen- erally face towards the west and the east wall was closed by a false door, the libraries of the two temples, Pr. Chrei and Pr. Pram open to the east and west. The main construction material used in these libraries was different depending on the temple. Some libraries consist mainly of sandstone or laterite, but for some libraries, laterite was used for the wall and sandstone for decorative parts such as the platform, foot of the wall, and cor- nice. Table 1. Scale of Temples d’étape. Short side (m) Long side (m) Pr. Thommanon 38.81 44.80 Pr. Chau Say Tevoda 40.00 44.00 Pr. Banteay Samrae 35.71 40.76 Pr. Chau Srei Vibol 30.79 32.07 Pr. Banteay Ampil 32.42 37.73 Pr. Chrei 32.39 37.90 Pr. Toap Chey 33.29 37.42 Pr. Pram 32.35 37.62 Pr. Supheap Tbong 32.08 37.60 Pr. Trapeang Chambok 32.27 37.60 In the Khmer temple complex, the southern library had a higher degree of engraving than the northern library, and if the temple had an asymmetric plan such as Pr. Thommanon, a sin- gle library was found in the south. In Temples d’étape, three of the temples, Pr. Chrei, Pr. Chambok and Pr. Supheap Tbong, used different material between the libraries, that is, the south- ern library was made of sandstone but the northern library was made of laterite. Configuration of the four gopuras in the enclosure wall was different within each temple. The enclosure wall opens in four directions except Pr. Banteay Ampil and Pr. Chambok that have  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 40 Figure 3. The arrangement of Temples d’étape and the average magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks (×10−3 SI units). no northern gopura. Among the three temples with four gopuras, the northern gopura of Pr. Toap Chey has a false door and is not utilized as an entrance. The eastern gopura is the largest and the southern gopura is second largest in all temples. The south side of the southern gopura is closed by a flat wall or false door in the all of the temples. This architectural feature is common to all the temples situated east of Pr. Banteay Ampil. In Pr. Chrei, Pr. Pram and Pr. Supheap Tbong which all have an open door at the northern gopura, the causeway extends toward the north from the northern gopura. Linga-like post  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 41 stones stand along the causeway, and a cruciform terrace is laid at Pr. Supheap Tbong. These suggest that the northern cause- way was the important connection to the royal road through the north side of each temple. In addition, Pr. Chrei, Pr. Toap Chey and Pr. Pram also have an eastern causeway, and effectively these temples had two causeways toward the north and east. The plan of the central sanctuary is relatively common among these nine temples except for Pr. Chau Srei Vibol, which has a single chamber without antechambers. Observing these nine temples carefully, four temples that are located to the east of Pr. Toap Chey have the same distinguishing configuration. The feature appears as two chambers at the east of main chamber in an exterior view because of a false window, but the actual inte- rior composition is a single antechamber. In this way, the eastern six temples from Pr. Banteay Ampil share similarity in the fundamental temple plan such as dimen- sion of the enclosure wall, composition of the temple layout, and closure to outside at the southern gopura. Moreover, the eastern four temples have remarkable similarity in the simplifi- cation in the interior chamber. Fire Shrines Along the east royal road, five temples known as Fire Shrines are positioned as follows: Pr. Kansaeng in Beng Mealea, Pr. Kuk in Preah Khan of Kompong Svay, Pr. Toap Chey, Pr. Ta En and Pr. Supheap Tbong. These temples have been previ- ously described by Lajonquière (1902). He reported two tem- ples, Pr. Kuk Top Thom and Pr. Teap Chei that we subse- quently refer to as Pr. Kansaeng and Pr. Toap Chey. Lajon- quière (1902) suggested that four temples, Pr. Kansaeng, Pr. Toap Chey, Pr. Ta En and Pr. Kuk, were of the same type as the facility, classified as Toap Chey type temples (Lajonquière, 1911). He interpreted these temples as rest houses for pilgrims. Foucher (1903) proposed another term “Dharmaçālā” (in San- skrit) for these temples because of the resembling buildings in India. Based on the agreement of the function as “Dharmaçālā” for these temples, Finot (1925) pointed out that these temples were the buildings of mercy (maison de charité). This was be- cause of the Lokeshvara sculpture on the pediment. Cœdés (1941) has interpreted them as fire houses (maison du feu) judging from the inscription of Preah Khan at Angkor (K.908). In the inscription, a total of 121 Fire Shrines have been re- corded, 57 temples along the road from Yaçodharapura to Campā, 17 temples along the road to the city of Vimāy, 44 temples along the circular road around the capital city, and 3 temples at other locations. The road from Yaçodharapura to Campā may be identified as the southeast royal road or the east royal road as called by Lajonquière (1902). However, it is rea- sonable to consider the road as the east royal road because Fire Shrines have never been found along the southeast royal road as Cœdés (1941) noted. There are several discussions on this type of temple by Welch (1997), Jacques and Lafond (2004) and Hendrikson (2007). The Fire Shrine consists of a single building with a size of 4 to 5 m wide and 14 to 15 m long (Finot, 1925; Hendrickson, 2007, 2008). With the exception of Pr. Toap Chey, the other four Fire Shrines are located on the north side of the east royal road. All the Fire Shrines are commonly positioned closer to the royal road than the Temples d’étape. Although the Fire Shrine is situated along the eastern causeway in the temple complex, Pr. Kansaeng in Beng Mealea temple complex is located along the western causeway. Therefore, it is suggested that worshipers accessed Beng Mealea temple complex from the west side that is also the direction to the capital city Ang- kor. Based on the lower quality of construction and engraving work and the decoration style, it is considered that all Fire Shrines were constructed in the Bayon period (1182 to 1270 CE). Traces of the additional wooden structures on the pedi- ment and the expunged deity motifs from the ridge stones show there was later modification to this structure. Methods Magnetic Susceptibility The magnetic susceptibility measurement was conducted non-destructively using a portable magnetic susceptibility meter SM-30 (ZH Instruments, Czech Republic) on a flat surface perpendicular to the bedding plane. The measurement accuracy is 1 × 10−6 SI units and the measurement time is approximately two seconds for one point. The sandstone blocks showed a considerable variation in magnetic susceptibility from block to block, so we measured 50 randomly selected sandstone blocks from each area and report their average value (Uchida et al., 2003, 2007). Magnetite is considered to be the main reason for the magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone. Based on these magnetic susceptibilities, 11 construction stages could be distinguished during the Angkor period (Uchida et al., 2003, 2007). In the Khmer buildings in the Angkor area, the magnetic susceptibility of the grey to yellowish brown sandstones tend to increase from 1.1 to 4.3 × 10−3 SI units from the Baphuon period to the Angkor Wat period. However, the value decreased abruptly to around 1.0 × 10−3 SI units in the main Bayon period, and then increased gradually to around 2.1 × 10−3 SI units in the later Bayon period. Characteristics of Stone Blocks The change over time of characteristics of sandstone and lat- erite blocks used in the Khmer monuments such as size, shape, orientation of bedding planes, and stacking method were sum- marized by Uchida et al. (2005). The stone blocks have square ends in the Baphuon style period, whereas they have rectangu- lar ends as well as square ends in the Angkor Wat period. After that, the stone blocks have rectangular ends. Until the early Bayon period, the stone blocks were stacked so that they were of uniform height and had a successive bed joint (coursed ash- lar masonry). The stone blocks after this period however, have different shapes and sizes, and show a non-successive bed joint (random range ashlar masonry). In addition, the orientation of bedding planes of the stone blocks is random until the Baphuon period, and became horizontal in the Angkor Wat period and later. Results and Discussion Pr. Chau S r ei V i bo l Pr. Chau Srei Vibol is surrounded by a moat 1500 m east- west by 1050 m north-south and is situated on a natural hill about 20 m high. A gallery surrounds the central sanctuary and northern and southern libraries on the top of the hill. There is a laterite enclosure wall at the foot of the hill. A building known as “palace” is situated at the southern foot of the hill. No in-  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 42 scription was found from Pr. Chau Srei Vibol, but it is consid- ered to have been constructed in the Baphuon period based on the decoration and architectural technique (Aymonier, 1901; Lajonquière, 1911). In Pr. Chau Srei Vibol, the stone block ends are square and their bedding planes orientation is random. As trenches were carved in the bottom face of the horizontal long sandstone blocks in the wall, it is surmised that the wooden beam that is invisible from an exterior viewpoint was installed in this space from the beginning of its construction. This reinforcement technique is widely used in the masonry of the Baphuon period (Cunin, 2004) and such characteristics may suggest that Pr. Chau Srei Vibol was constructed during that period. However, there was a slight difference in the magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks between buildings on the hilltop and the gopuras of the enclosure wall at the foot. The magnetic suscep- tibility of the buildings and the gallery on the hilltop are rela- tively high (1.41 to 3.71 × 10−3 SI units, av. 2.85 × 10−3 SI units) (Figure 5(b)), whereas those of the gopuras in the foot are lower, (1.28 to 2.18 × 10−3 SI units, av. 1.72 × 10−3 SI units) (Figures 4 and 5(a)). As the magnetic susceptibility of the sandstones increase gradually from the Baphuon period to the Angkor Wat period, their magnetic susceptibilities may suggest that the gopuras of the enclosure wall at the foot was con- structed prior to the buildings and gallery on the hilltop. The magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks used in the gopuras of the enclosure wall coincides with those in the Baphuon period, whereas the magnetic susceptibility of the buildings and gallery on the hilltop suggest they were con- structed in the early Angkor Wat period. However, the stone blocks used in the buildings and gallery on the hilltop have a random orientation of bedding planes, which is one of the characteristics of stone blocks used in the buildings constructed up until the Baphuon period. These characteristics contradict each other and may suggest that Pr. Chau Srei Vibol was con- structed in the transitional period between the Baphuon and the Angkor Wat period. Beng Mealea Beng Mealea is situated about 40 km east of Angkor Wat in the southeastern foot of Mt. Kulen (Figure 2). Boisselier (1952) considered from an art history viewpoint that Beng Mealea was constructed in the transitional period between the Angkor Wat and the Bayon period. Traces of reconstruction at later periods have been found in several places at Beng Mealea. Beng Mealea was built mainly of sandstone blocks with high processing precision. The sandstone blocks have successive horizontal joints and horizontal bedding planes with generally rectangular ends mainly of 27 to 35 cm by 45 to 50 cm. How- ever, larger sandstone blocks were used in two palaces in the south side between the middle and the outer galleries and also in the central sanctuary. The size of the larger sandstone blocks is mainly 50 to 80 cm by 80 to 220 cm on the wall surface. Judging from an architectural point of view, no difference in the construction period could be confirmed between the palaces and the galleries. Such large sandstone blocks were used in Angkor Wat and Wat Athvea constructed in the Angkor Wat period. In addition, larger sandstone blocks are also found in several buildings in Koh Ker. The above-mentioned character- istics suggest that Beng Mealea was constructed in the Angkor Wat period. The magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks is dif- ferent from place to place and ranges from 1.8 to 4.4 × 10−3 SI units (Figures 5(c) and 6). Their magnetic susceptibility sug- gests that Beng Mealea was constructed during the same period as Pr. Thommanon and Pr. Chau Say Tevoda, that is, in the early Angkor Wat period. This suggests that the sandstone Figure 4. The average magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks used in Chau Srei Vibol (×10−3 SI units).  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 43 blocks used in Beng Mealea were supplied from the southeast- ern foot of Mt. Kulen as with other Khmer buildings in the Angkor area. However, some decorations have the characteris- tics of the transitional period between the Angkor Wat period and the Bayon period suggesting a time lag between the con- struction period and the decoration period. Preah Khan of Kompong Svay Preah Khan of Kompong Svay is situated about 100 km east of Angkor Wat. The inscription K.161 in Pr. Kat Kdei of Preah Khan of Kompong Svay suggests that Pr. Kat Kdei was con- structed in the reign of Suryavarman I (1002 to 1050 CE). This temple is purported to be the oldest one in Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. It is considered that almost all the temples in Preah Khan of Kompong Svay were built later by Suryavarman II (the Angkor Wat period) and Jayavarman VII (the Bayon period) (Mauger, 1939; Stern, 1965; Cunin, 2004). The exis- tence of a standing Buddha building in the southeast of the central part suggests that the Preah Khan of Kompong Svay had been used as a religious site until the post Bayon period. The sandstone blocks used in Preah Khan of Kompong Svay have relatively high magnetic susceptibility of 1.4 to 2.0 × 10−3 SI units in the eastern and western gopuras of the outer gallery, the four gopuras of the inner gallery, the central sanctuary, and the northern and southern libraries (Figures 5(d) and 7). The sandstone blocks used in Pr. Kat Kdei mentioned above also have relatively high magnetic susceptibility. On the other hand, the sandstone blocks with relatively low magnetic susceptibili- ties of 0.3 to 0.6 × 10−3 SI units were used in the building situ- ated just east of the eastern gopura of the inner gallery (Figures 5(e) and 7), the northern and southern gopuras of the outer gal- lery, the inner gallery and a part of the outer gallery. In addition, the sandstone blocks used in the eastern and western gopuras of the outermost enclosure wall, Pr. Preah Thkol, Pr. Preah Stung and Pr. Damrei have lower magnetic susceptibilities of 0.2 to 0.5 × 10−3 SI units. The sandstone blocks with relatively high magnetic susceptibilities were processed with high precision, and have successive horizontal joints, square ends and horizon- tal bedding planes. These are characteristics of the buildings constructed during the Angkor Wat period. As for their mag- netic susceptibility, these sandstone blocks are concordant with those of Khleang, Baphuon and early Angkor Wat periods. These characteristics suggest that the buildings with relatively high magnetic susceptibility were constructed in the early Ang- kor Wat period, and that these sandstone blocks were supplied from Mt. Kulen the same as those used in the buildings in the Angkor area. The sandstone blocks with relatively low magnetic suscepti- bility have rectangular ends and horizontal bedding planes, and are of random range ashlar. In addition, the processing preci- sion of these sandstone blocks is relatively low. These charac- teristics suggest that the buildings constructed with sandstone blocks with relatively low magnetic susceptibility were con- structed in the main Bayon period and onwards. Pr. Preah Stung has a tower decorated with faces, which is one of the architectural characteristics in the main Bayon period. The magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks used in these buildings is different from those used in the Angkor area during the main Bayon period. This fact suggests that these sandstone blocks were supplied from quarries that are different from Mt. Kulen, but probably from quarries close to Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. Figure 5. Histograms of magnetic susceptibilities of sandstone blocks used in Chau Srei Vibol, Beng Mealea and Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. av.: average magnetic susceptibility, and s.d.: standard deviation. Temples D’étape This section describes the characteristics of the sandstone blocks used in the Temples d’étape. The sandstone blocks have rectangular ends of a size mainly of 31 to 40 cm by 42 to 59 cm, and were of coursed ashlar masonry. In addition, the orientation of the bedding planes is horizontal. These characteristics are concordant to those of sandstone blocks used in the Angkor area from the Angkor Wat period to the early Bayon period. The magnetic susceptibility values from each temple are shown in Figures 3 and 8. With the exception of Pr. Trapeang Cham- bok, the magnetic susceptibility ranges from 2.0 to 4.7 × 10−3 SI units. Judging from these values, it is suggested that these temples were constructed in the early Angkor Wat period. The average magnetic susceptibilities are 2.84 × 10−3 SI units for Pr. Banteay Ampil; 3.03 × 10−3 SI units for Pr. Chrei; 3.05 × 10−3 SI units for Pr. Toap Chey; 3.77 × 10−3 SI units for Pr. Pram, and 4.48 × 10−3 SI units for Pr. Supheap Tbong. As a whole, the magnetic susceptibility values increase eastward (Figure 8). This may suggest that these temples have been constructed eastward in this order, and that the sandstone  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 44 Figure 6. The average magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks used in Beng Mealea (×10−3 SI units). blocks were supplied from Mt. Kulen. On the other hand, the magnetic susceptibility of the sand- stone blocks used in Pr. Trapeang Chambok is as low as 0.39 × 10−3 SI units, similar to the sandstone blocks with low magnetic susceptibility used in Preah Khan of Kompong Svay (0.2 to 0.6 × 10−3 SI units). From the temple layout, Pr. Trapeang Chambok is likely to have been constructed in the early Angkor Wat pe- riod, the same period as the other Temples d’étape. Therefore, it is likely that the change from the sandstone blocks with high magnetic susceptibility to those with low magnetic susceptibil- ity occurred in the early Angkor Wat period, not in the transi- tional period from the Angkor Wat to the Bayon period. As the magnetic susceptibility values of the sandstone blocks with relatively low magnetic susceptibility are different from those of the sandstone blocks supplied from Mt. Kulen at that period, they are considered to have been supplied from quarries around Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. The magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks used in the mandapa of Pr. Toap Chey is clearly low compared with those in the other parts. Almost all sandstone blocks used in the mandapa have magnetic susceptibilities of approximately 0.3 × 10−3 SI units, whereas a small number of sandstone blocks have higher magnetic susceptibilities that range from 1.0 to 6.0 × 10−3 SI units. This fact may suggest that the sandstone blocks with low magnetic susceptibility were supplied from quarries situated near Preah Khan of Kompong Svay, and that the sand- stone blocks with high magnetic susceptibility supplied from Mt. Kulen were mixed with them. However, no architectural evidence supporting that the mandapa was constructed after the other parts was observed. In addition, although there is a difference in scale (Table 1), Pr. Thommanon and Pr. Chau Say Tevoda were the buildings constructed in the early Angkor Wat period (Uchida et al., 2007) and have a similar temple arrangement to the Temples d’étape along the east royal road to Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. These facts suggest that Pr. Thommanon and Pr. Chau Say  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 45 Figure 7. The average magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks used in Preah Khan of Kompong Svay (×10−3 SI units).  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 46 Figure 8. Histograms of magnetic susceptibilities of sandstone blocks used in Temples d’étape. av.: average magnetic susceptibility, and s.d.: standard deviation. Tevoda were constructed as a series of Temples d’étape. The magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks used in Pr. Thommanon ranges from 2.0 to 2.9 × 10−3 SI units and the average is 2.54 × 10−3 SI units. These values are slightly lower than those of the Temples d’étape. This may suggest that Pr. Thommanon was constructed earlier than the Temples d’étape. On the other hand, the range of magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks used in Pr. Chau Say Tevoda is even wider from 1.1 to 5.5 × 10−3 SI units with an average of 3.20 × 10−3 SI units. The value of 1.1 × 10−3 SI units is lowest among the Temples d’étape and the value of 5.5 × 10−3 SI units is highest. The magnetic susceptibility values may suggest that the con- struction of Pr. Chau Say Tevoda started before the Temples d’étape, but ended after them. In summary, it is considered that Pr. Thommanon and Pr. Chau Say Tevoda began construction before the Temples d’étape and that the Temples d’étape were constructed eastward including Pr. Thommanon and Pr. Chau Say Tevoda. Fire Shrines The buildings of Fire Shrines were constructed with sand- stone blocks with rectangular ends mainly of 30 to 35 cm by 43 to 51 cm. They show a variation in size and were stacked ran- domly. The orientation of bedding planes is generally horizon- tal. The magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks is also high in the Fire Shrines situated in the western area such as Pr. Kansaeng (2.71 × 10−3 SI units), Pr. Toap Chey (3.14 × 10−3 SI units) and Pr. Ta En (2.66 × 10−3 SI units) (Figure 9). On the other hand, the magnetic susceptibility of the sandstone blocks is low in Pr. Supheap Tbong (0.36 × 10−3 SI units) and Pr. Kuk (0.40 × 10−3 SI units) situated in the eastern area. This suggests that the sandstone blocks with higher magnetic susceptibility were supplied from quarries at the southeastern foot of Mt. Kulen, but that those with lower magnetic susceptibility were supplied from quarries near Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. The magnetic susceptibilities therefore suggest that Pr. Kansaeng (2.71 × 10−3 SI units), Pr. Toap Chey (3.14 × 10−3 SI units) and Pr. Pram (2.66 × 10−3 SI units) were constructed in the Angkor Wat period to the early Bayon period or in the late Bayon pe- riod. As the processing precision of the sandstone blocks was low compared with those used in the Temples d’étape and the sandstone blocks were stacked randomly, they are considered to have been constructed in the late Bayon period. There are also Fire Shrines in Ta Prohm and Preah Khan in the Angkor area. They have an average magnetic susceptibility of 1.12 and 0.92 × 10−3 SI units, respectively (Figure 9). These values suggest that they were constructed during the main Bayon period. As mentioned above, the Fire Shrines along the east royal road are considered to have been constructed in the late Bayon period. This means that the Fire Shrines of Ta Prohm and Preah Khan were constructed before them and sug- gests that the Fire Shrines were also constructed eastward. The Provenance of the Sandstone Blocks The sandstone blocks used in Preah Khan of Kompong Svay can be divided into two based on their magnetic susceptibility. The sandstone blocks with higher magnetic susceptibility (1.4 to 2.0 × 10−3 SI units) have square ends and horizontal bedding planes, were stacked regularly, and are of a high precision processing. Combined, these characteristics are concordant with those in the early Angkor Wat period indicating that the sand- stone blocks were supplied from Mt. Kulen. The sandstone blocks with lower magnetic susceptibility (0.2 to 0.6 × 10−3 SI units) have rectangular ends and horizontal bedding planes, were stacked randomly, and are of a low precision processing. These characteristics are concordant with those in the main Bayon period and later. As the sandstone blocks with low magnetic susceptibilities can be found only locally in the Ang- kor area, it is considered that the sandstone blocks were sup- plied from the surrounding area of Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. Based on the architectural style and the characteristics of the sandstone blocks, the Temples d’étape were probably con- structed during the early Angkor Wat period. The magnetic  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 47 Figure 9. Histograms of magnetic susceptibilities of sandstone blocks used in Fire Shrines. av.: average magnetic susceptibility, and s.d.: standard deviation. susceptibility of the sandstone blocks from the Temples d’étape of Pr. Banteay Ampil to Pr. Pram is concordant with those used in the buildings constructed during the early Angkor Wat pe- riod, e.g. Pr. Thommanon and Pr. Chau Say Tevoda. This sug- gests that the sandstone blocks used in these Temples d’étape were supplied from quarries at the southeastern foot of Mt. Kulen. The sandstone blocks used in Pr. Trapeang Chambok, the nearest to Preah Khan of Kompong Svay have low magnetic susceptibility. As sandstone blocks with low magnetic suscep- tibility can be found only locally in the Angkor area, the sand- stone blocks of Pr. Trapeang Chambok are likely to have been supplied from the surrounding area of Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. As for the Fire Shrines, the sandstone blocks used in Pr. Ta En and those situated in the western area have high magnetic susceptibility. Their values are concordant with the sandstone blocks used in the buildings in the Angkor area constructed during the late Bayon period and later. This implies that the sandstone blocks used in the Fire Shrines were supplied from Mt. Kulen. However, Pr. Supheap Tbong situated in the nearest position to Preah Khan of Kompong Svay and Pr. Kuk in Preah Khan of Kompong Svay have low magnetic susceptibility and the values are not concordant with those of the sandstone blocks used in the Angkor area in the main Bayon period and later. Thus, it is considered that the sandstone blocks used in these two Fire Shrines were supplied from quarries around Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. Using these data, we suggest that the sandstone blocks were transported to Preah Khan of Kompong Svay from Mt. Kulen in the Baphuon period to the beginning of the Angkor Wat period. In the early Angkor Wat period, the sandstone blocks were transported to Pr. Supheap Tbong from Mt. Kulen, but the sandstone blocks of Pr. Trapeang Chambok were supplied from quarries around Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. In the late Bayon period, sandstone blocks from Mt. Kulen were trans- ported to Pr. Ta En, but those of Pr. Supheap Tbong were transported from quarries around Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. Old quarries consisting of grey to yellowish brown sandstone have not yet been found around Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. However, there is an operating quarry consisting of grey to yellowish brown sandstone 35 km northeast of Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. The magnetic susceptibility of that sandstone is low (0.22 × 10−3 SI units). This suggests the possibility that there are quarries of grey to yellowish brown sandstone with low magnetic susceptibility around Preah Khan of Kompong Svay that remain to be found. Acknowledgements This study was supported financially by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Project No. 23401001 (E. Uchida)) and by UNESCO/Japanese Funds-in-Trust for the Preservation of the World Cultural Heritage. REFERENCES Boisselier, J. (1952). Bĕn Mãlã et la chronologie des monuments du style d’Angkor Vat. Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient, 46, 187-226. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/befeo.1952.5162 Carò, F., & Im, S. (2012). Khmer sandstone quarries of Kulen Moun- tain and Koh Ker: A petrographic and geochemical study. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39, 1455-1466. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2012.01.007 Cœdés, G. (1941). La stele du Práh Khan d’Ankor. Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient, 41, 255-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/befeo.1941.5711 Cunin, O. (2004). De Ta Prohm au Bayon. Analyse comparative de  E. UCHIDA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 48 l’histoire architecturale des principaux monuments du style du Bayon. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Nancy: L’Institut National Poly- technique de Lorraine. Finot, L. (1925). Dharmaçalas au Cambodge. Bulletin de l’École Fran- çaise d’Extrême-Orient, 25, 417-422. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/befeo.1925.3060 Foucher, A. (1903). Nouvelles et Mélanges. Critique de E. Lunet de Lajonquière, 1902, Inventaire descriptif des monuments du Cam- bodge. Journal Asiatique, 10, 174-180. Groslier, B. P. (1973). Les Inscriptions du Bayon, Le Bayon (pp. 116-118). Paris: EFEO. Hendrickson, M. (2007). Arteries of empire—An operational study of transport and communication in Angkorian Southeast Asia. Unpub- lished Ph.D. Thesis, Sydney: University of Sydney. Hendrickson, M. (2008). People around the houses with fire: Archaeo- logical investigation of settlement around the Jayavarman VII “rest- house” temples. UDAYA, 9, 63-79. Jacques, C., & Lafond, P. (2004). L’Empire Khmer, Cités et Sanc- tuaires Vème-XIIIème siècle. Paris: Fayard. Lunet de Lajonquière, E. (1902). Inventaire descriptif des monuments du Cambodge, vol. 1. Paris: E. Leroux. Lunet de Lajonquière, E. (1911). Inventaire descriptif des monuments du Cambodge, vol. 3. Paris: E. Leroux. Mauger, H. (1939). Prah khan de kompon svay. Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient, 39, 197-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/befeo.1939.3722 Parmentier, H. (1948). L’Art khmer classique. Monuments du Quadrant Nord-Est, Les Éditions et D’histoire. EFEO, 1948, 112-113. Stern, P. (1965). Les Monuments Khmer du Style du Bàyon et Jay- avarman VII, vol. 11. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. Trouve, G. (1934). Chronique de L’Année 1932, Cambodge. Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient, 33, 524-525. Uchida, E., & Shimoda, I. (2013). Quarries and transportation routes of Angkor monument sandstone blocks. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40, 1158-1164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2012.09.036 Uchida, E., Cunin, O., Shimoda, I., Suda, C., & Nakagawa, T. (2003). The construction process of the Angkor monuments elucidated by the magnetic susceptibility of sandstone. Archaeometry, 45, 221-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1475-4754.00105 Uchida, E., Cunin, O., Suda, C., Ueno, A., & Nakagawa, T. (2007). Consideration on the construction process and the sandstone quarries during Angkor period based on the magnetic susceptibility. Journal of Archaeological Science, 34, 924-935. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2006.09.015 Uchida, E., Ogawa, Y., & Nakagawa, T. (1998). The stone materials of the Angkor monuments, Cambodia. The magnetic susceptibility and the orientation of the bedding plane of the sandstone. Journal of Mineralogy, Petrology and Economic Geology, 93, 411-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.2465/ganko.93.411 Uchida, E., Suda, C., Ueno, A., Shimoda, I., & Nakagawa, T. (2005). Estimation of the construction period of Prasat Suor Prat in the Angkor monuments, Cambodia, based on the characteristics of its stone materials and the radioactive carbon age of charcoal fragments. Journal of Archaeological Science, 32, 1339-1345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2005.03.011 Welch, D. J. (1997). Archaeological evidence of Khmer state political and economic organization. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 16, 69-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.7152/bippa.v16i0.11648

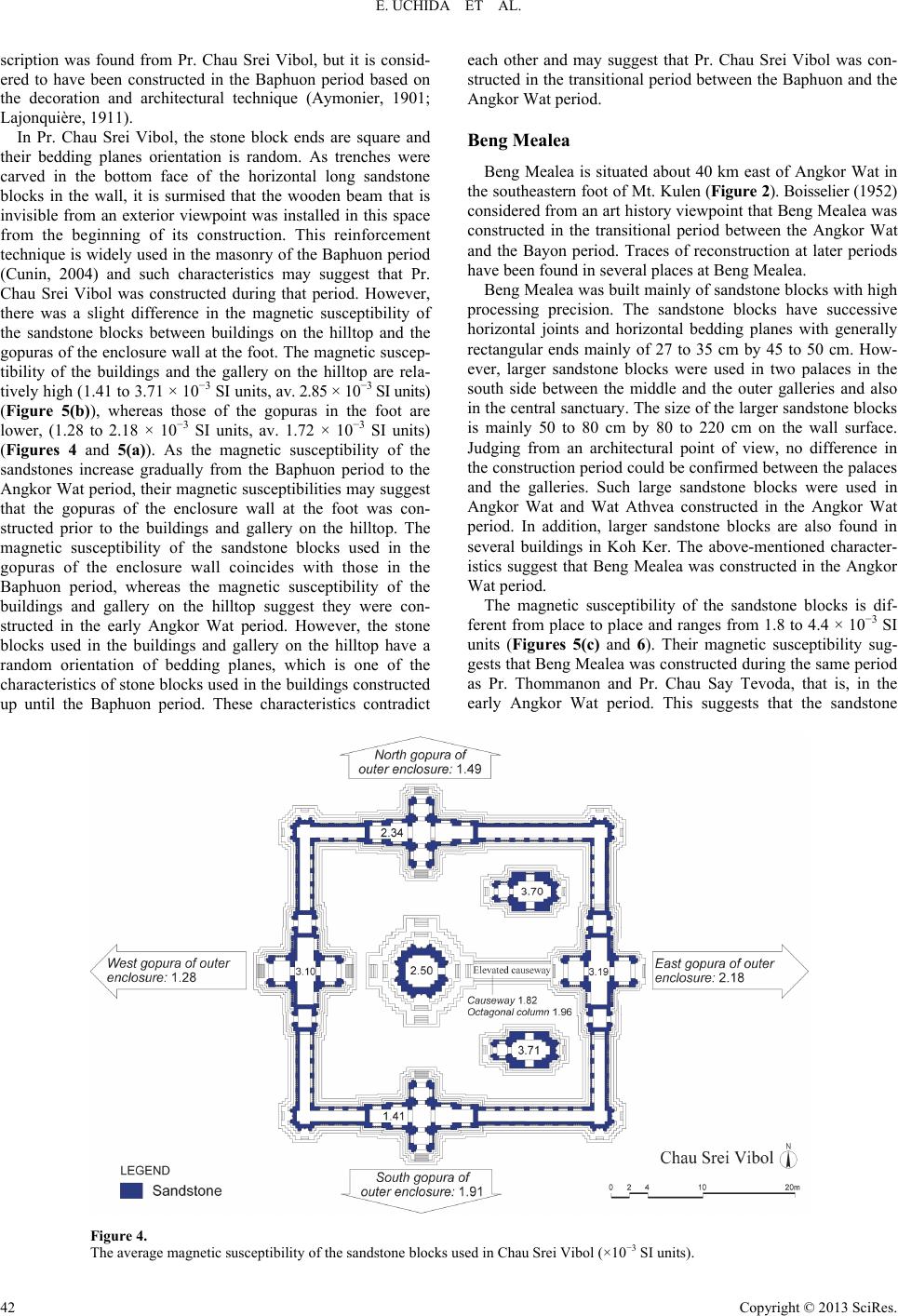

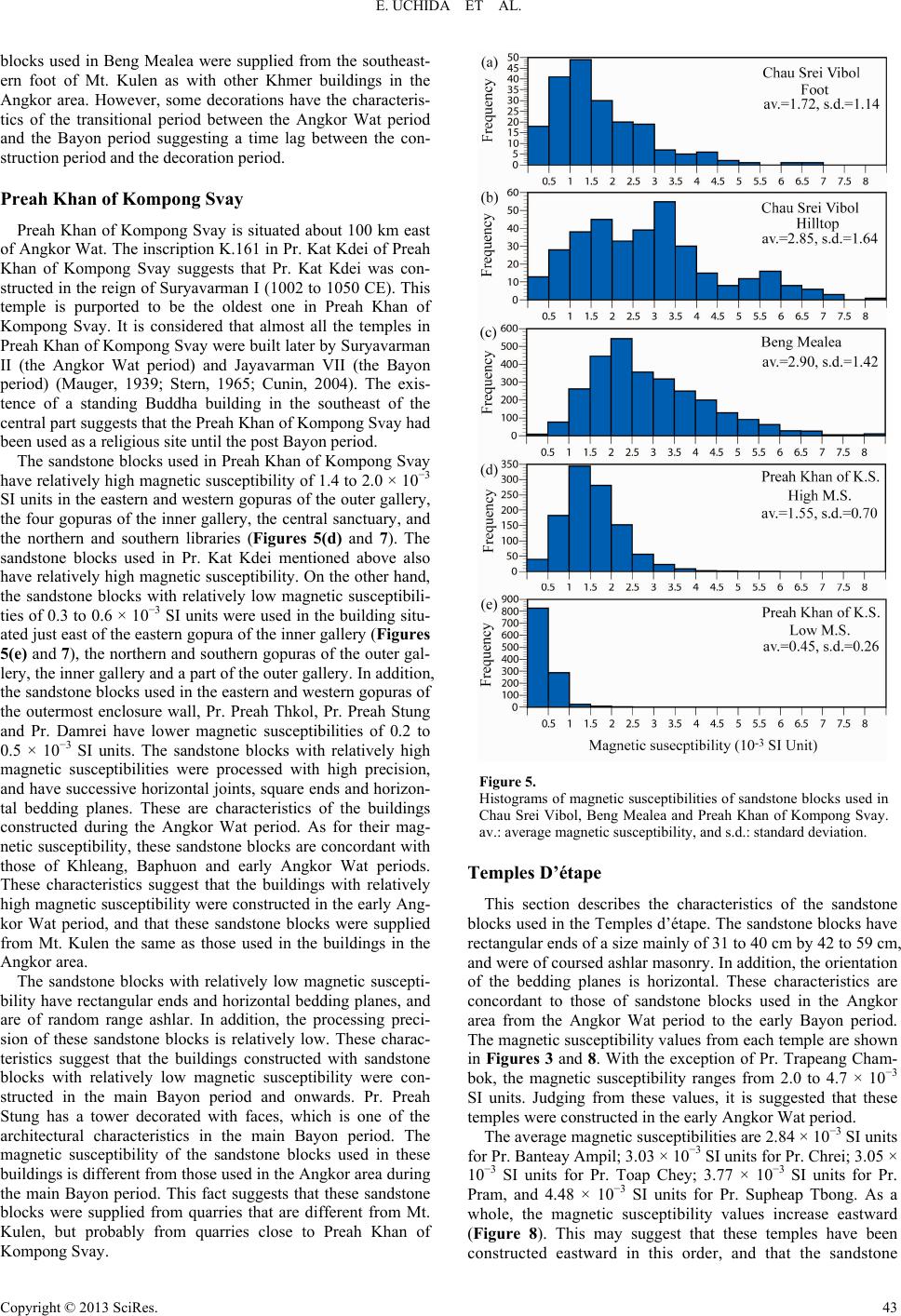

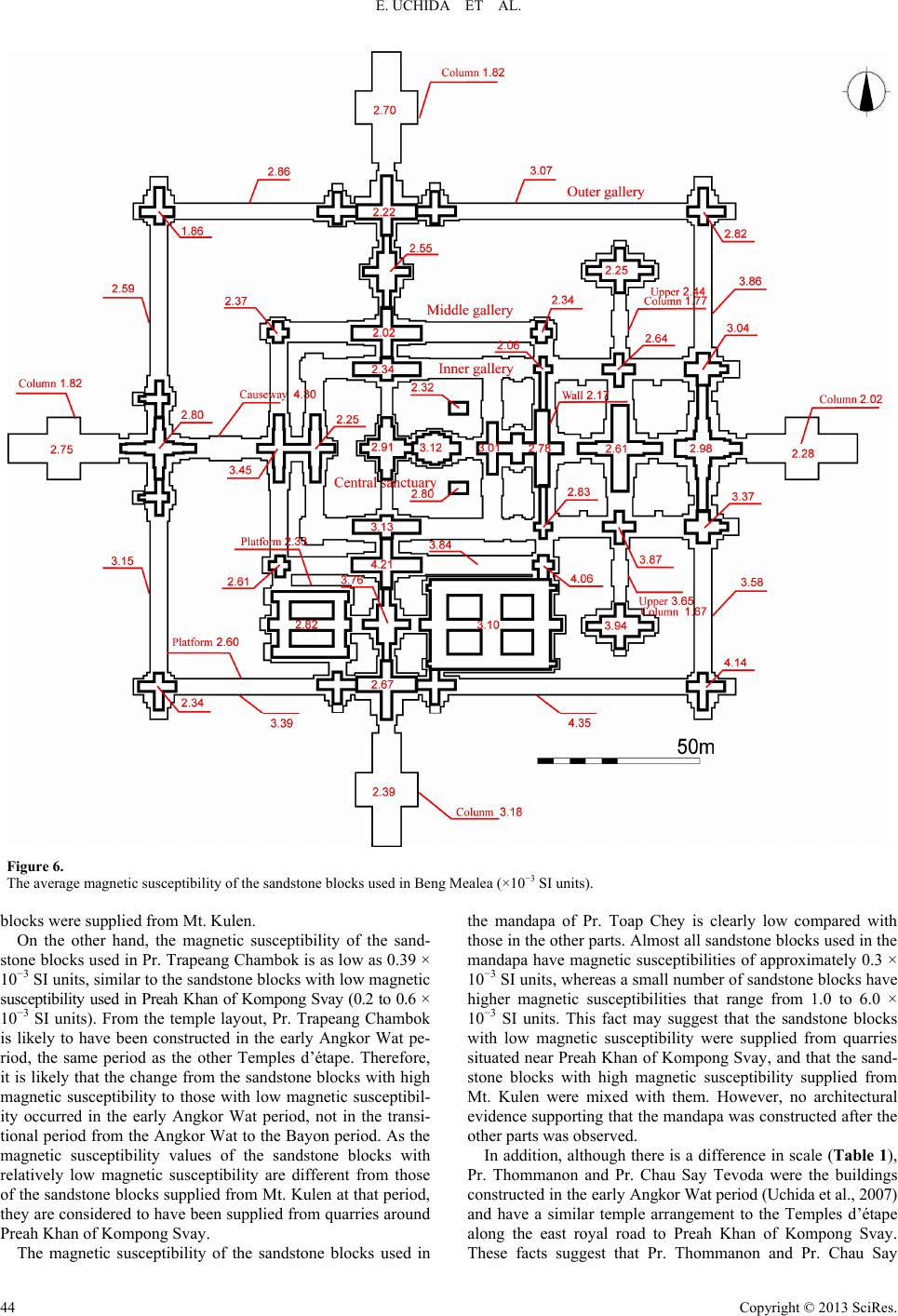

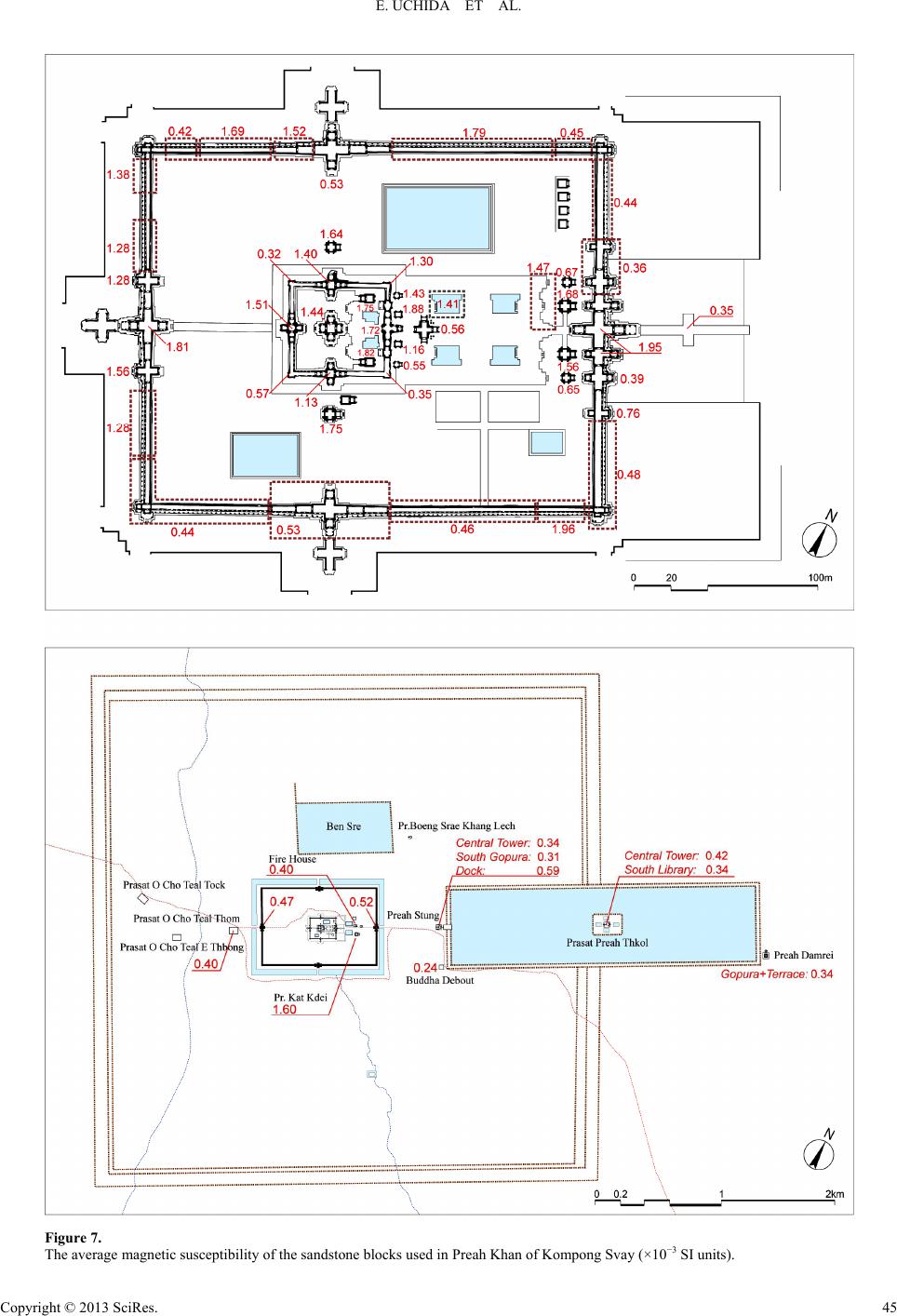

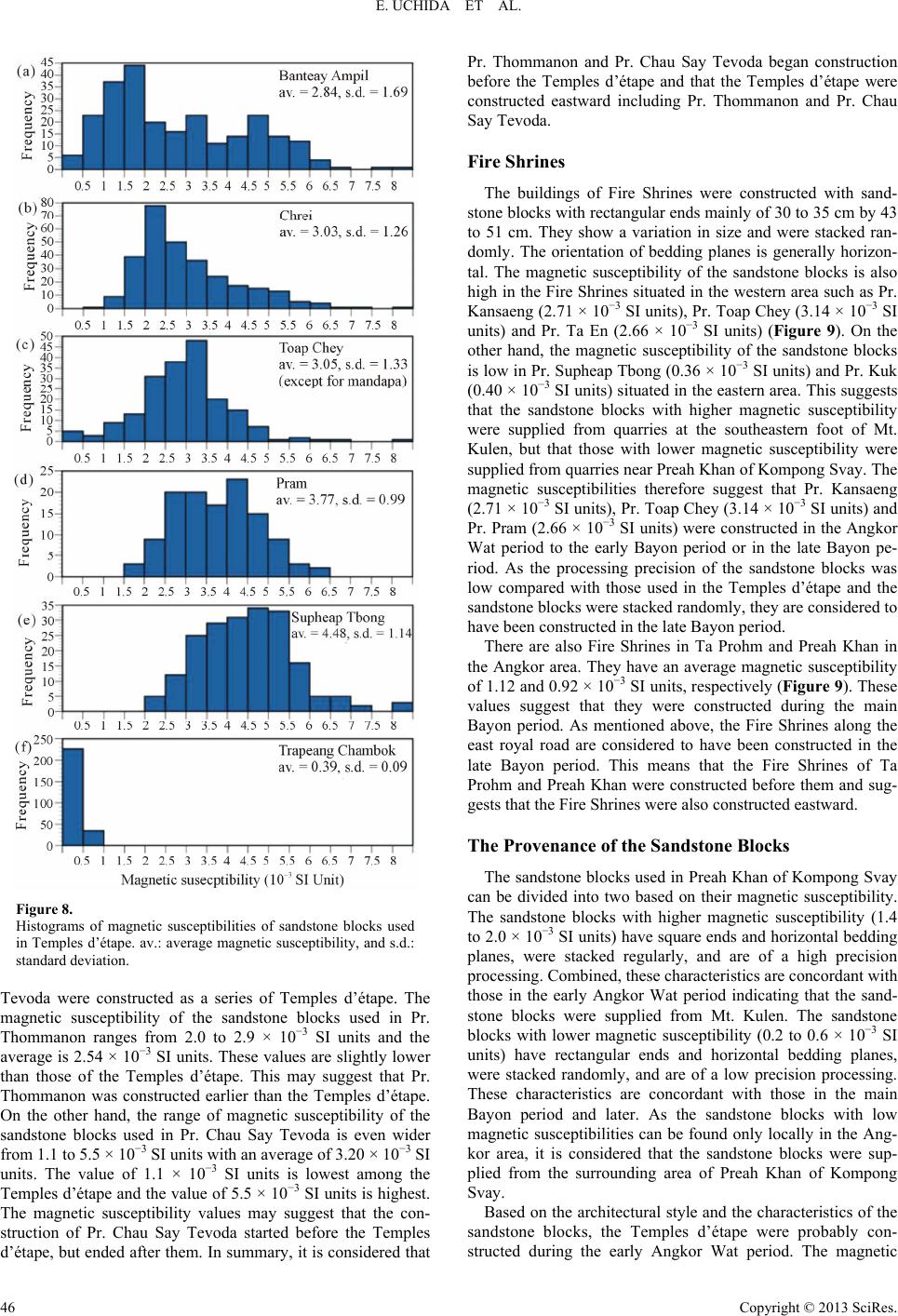

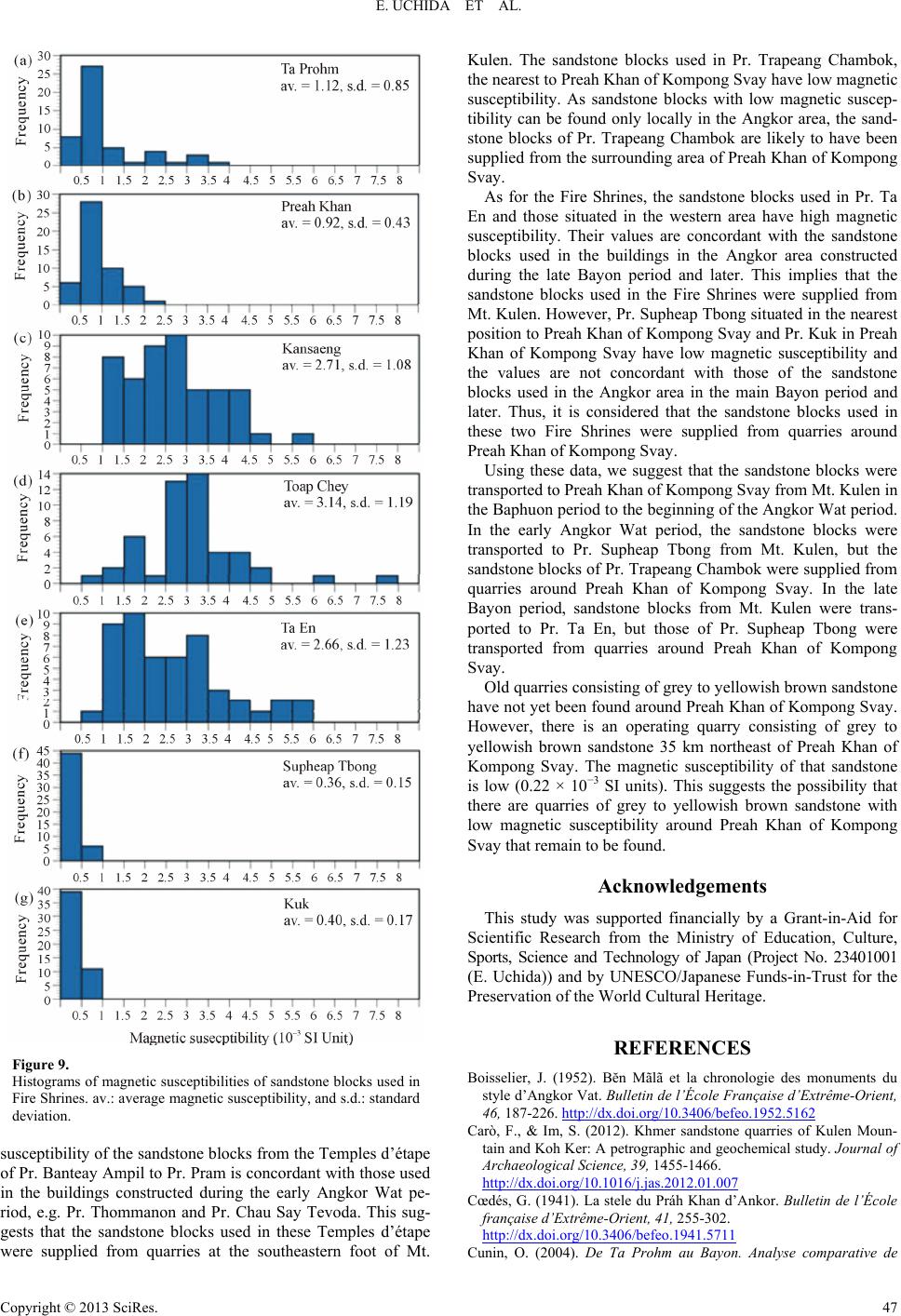

|