Sociology Mind 2013. Vol.3, No.4, 290-297 Published Online October 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2013.34039 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 290 Violent Radicalisation and Recruitment to Terrorism: Perspectives of Wellbeing and Social Cohesion of Citizens of Muslim Heritage Priyo Ghosh1, Nasir Warfa1, Angela McGilloway1, Imran Ali2, Edgar Jones3, Kamaldeep Bhui1 1Centre for Psychiatry, Queen Mary University of London, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, London, UK 2Greater Manchester West, Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, UK 3King’s Centre for Military Health Studies at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College, London, UK Email: pghosh213@yahoo.co.uk, k.s.bhui@qmul.ac.uk Received June 29th, 2013; revised August 3rd, 2013; accepted August 19th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Priyo Ghosh et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. After the 7/7 bombings radicalisation became a homegrown issue in the UK with Muslims born and brought up here being responsible for the attacks. This has had a subsequent impact on wellbeing and so- cial cohesion in the UK. It feels that the Government’s strategy of tackling radicalisation is ineffective and may be paradoxically serving to increase recruitment to radical groups. There is limited primary re- search from a sociological or a psychological perspective on the issue of radicalisation amongst the Mus- lim community in the UK. Two focus groups with six men and ten women, aged between 22 and 56, were established to determine the meaning of radicalisation to Muslims, gather experiences of the impact of the concept of radicalisation on the wellbeing of the Muslim community, understand more about the socio- logical and psychological processes that lead to radicalisation and gather in-group perspectives on how to tackle radicalisation as a means to promote social cohesion. Islamophobic media coverage and discrimi- nation affected the wellbeing of the Muslim community resulting in a more orthodox religious identity. Drivers of radicalisation were perceived to include inequalities, and misrepresentation of Islamic teach- ings. Solutions to tackle radicalisation and promote social cohesion included authentic Islamic education, greater integration and reducing inequalities with greater acceptance by the Muslim community alongside more responsible journalism. Although further work is needed in Muslim communities, there also needs to be work done on non-Muslim communities to further understand the impact of extremism on social cohesion and wellbeing. Keywords: Radicalisation; Extremism; Wellbeing; Social Cohesion; Prevention; United Kingdom Introduction Terrorist attacks cause widespread loss of life, physical inju- ries, psychological trauma and economic damage. There are additional societal costs in terms of social division, vilification of and discrimination against those perceived to be associated with or sympathetic to terrorist actions (Bhui et al., 2012). In terms of direct loss of life, the 9/11 attacks claimed the lives of almost 3000 people and in 2005 the terrorist attacks in London (UK) claimed the lives of 52 people. In the last ten years, thou- sands of people were killed by suicide bombings in Iraq (Hicks et al., 2011) and in Pakistan (Mir, 2011). These events were followed by numerous counter-terrorism actions to prevent ter- rorist plots. These efforts increasingly acquired an international as well as pan-European dimension. The surprising fact that emerged is that the attacks in the EU were often by people who had been born and educated in the countries that they attacked. In a manner that remains unclear, these home-grown terrorists had formed links with radical Muslim groups creating a new threat of terrorism from people who felt it difficult to identify or notice as posing a threat to society. Radicalisation was pro- posed as the social and psychological process that transformed citizens into terrorists. Yet, despite widespread use of the term there is no widely accepted consensus on a definition nor is there research to show how radicalisation works and how it might be prevented. The UK Government’s Anti-Terrorism Prevent Strategy (2011) defined radicalisation as the process by which a person comes to support terrorism and forms of extremism leading to terror- ism. Extremism was defined as vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. Also included in the definition of extremism was calling for the death of members of British armed forces. The process of radicalisation is thought to occur during criti- cal periods of maturation in cognitive and emotional processes in adolescence when young people face numerous transitions. Young adults experiment with new identities, group relation- ships and political viewpoints. Questioning authority and con- sidering political alternatives are the norm for young people who are often ideologically driven and form commitments to a new cause or mission as part of this experimentation with a new identity.  P. GHOSH ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 291 It is often asserted that radicalisation has its roots in an Is- lamic ideology that proposes Western liberalism to be intrinsi- cally evil and promotes a state of paradise to be achieveable by destroying such Western values (Stern, 2003). In contrast, Tess- ler (1997) argued that radical Muslim movements represent modern reactions to unemployment, poverty and marginalisa- tion. It is understandable that a stronger Islamic identity and keeping close associations with like-minded Muslims may help combat discrimination and offer support in the face of adversity. This view is challenged by the findings that many of those radicalised in Europe have come from educated, middle-class backgrounds (Bakker, 2006). Despite the emphasis on Muslim youth as being vulnerable to radicalisation, there is little open discussion with communi- ties from which these radicalised youth are purported to emerge. In contrast, the rhetoric that Muslim ideology drives terrorism is well known and overstated by terrorist organisations as this offers a ready source of support by placing practising Muslims in a conflict of identities and loyalties. This overstatement of the role of religion may also become a natural reaction of poli- ticians and policy makers responding to terrorist attacks in their countries. The use of Islamic fundamentalism as an explanation for terrorism provides the victim countries with an understand- able basis on which to react, but risks alienating groups of citi- zens who could be part of a counter-terrorism strategy. What responses have evolved in the UK without engagement of Muslim communities? New laws have increased the legal duration of detention without charge if terrorism is suspected; these laws have widened stop and search powers. The UK Gov- ernment also introduced the Prevent Strategy aimed at devel- oping co-operation with the Muslim community. However, ear- lier versions of the Prevent strategy were criticised as singling out Muslim communities, ignoring other forms of extremism, and serving as a vehicle for increased surveillance of British Muslims as suspects rather than involving them as citizen serv- ing to increase recruitment to radical groups whilst undermin- ing the health and well-being of the Muslim (Kundani, 2009). Others felt that the Prevent Strategy was allowing funding for Muslim groups that espoused illiberal and intolerant views thus damaging social cohesion (Maher & Frampton, 2010). There is currently a lack of empirical research conducted on radicalisation within the British Muslim community (Silke, 2008). As a result, we set up a series of studies to investigate this concept from a qualitative and quantitative perspective. This paper reports on the pilot work that informed a larger sur- vey of radicalisation in Muslim young people with the follow- ing research questions: What does the term radicalisation mean to Muslims? How has the discourse around radicalisation affected Mus- lims? What do Muslims feel are the sociological and psychological processes behind radicalisation? What strategies do they think will effectively tackle radicali- sation as a means to promote social cohesion? Methods A focus group study was adopted to explore opinions from a wide range of people of Muslim heritage. This design allows for views that are socially produced as in a community rather than only those that are discreetly formed at the level of the individual (Lunt & Livingstone, 1996: p. 90). Two focus groups were run with participants of Muslim heritage or participants who had converted to Islam, but participants were not necessarily orthodox or practicing their faith. All ethnicities and those be- longing to any Muslim sect were eligible. Participants had to be able to speak English. As part of the recruitment and the development of a commu- nity panel, contact was made with the Federation of Islamic Students (FOSIS). They enthusiastically supported the study. Participants were also invited from a local Muslim Community Panel. Many of these people were in touch with Queen Mary University or local health agencies, and some were interested in research themselves, so they saw the study as part of their wider efforts to improve the health and wellbeing of local populations in East London. Researchers also adopted a snowballing method to include people with a background in psychological and men- tal health fields to help formulate psychological and sociologi- cal based understandings as well as religious and cultural in- sights into radicalisation. So participants were offering an “in- sider’s” view about living in a Muslim community in Britain as well as a view informed by their experiences in professional life and research and teaching. A topic guide was developed in consultation with local re- searchers who were of Muslim heritage, and this was used in both focus groups. The groups were audio-recorded and the transcripts subjected to qualitative analysis. The recordings were listened to a number of times to familiarise the researchers with the data. Initial notes were taken to identify broad themes. The transcripts were then analysed again grouping categories to- gether to develop links between different participants and across the focus groups. This process followed the Thematic Content Analysis described by Green and Thurugood (2009). The analy- ses were undertaken by two researchers who worked inde- pendently during the first round of analyses, before meeting to reach consensus. A brief demographic questionnaire was also completed. All participants provided consent to take part in the study after being made aware of the topics to be discussed. No financial incentives were offered to participants. Ethical ap- proval was received from the research ethics committee at Queen Mary University of London. Results The focus groups consisted of 15 subjects (9 females and 6 males). The first focus group had 10 participants with a broad age range between 22 and 56, whilst the second focus group had 5 participants with a narrower age range between 27 and 35. Both focus groups lasted one hour and were audio-recorded. In the first focus group there was an over representation of Turk- ish female students together with an underrepresentation of Brit- ish females. Overall there was a range of ethnicities: South Asian (Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi), African and Middle Eastern origins and British nationals. To maintain anonymity there is no correlation between the order of participants in the table and the number assigned in the results section (see Table 1). Meanings of Radicalisation The groups spent some time discussing what radicalisation and their distinct interpretations as well as how the media por- trayed radicalisation. The main definitions and issues are sum- marised below in Table 2.  P. GHOSH ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 292 Table 1. Focus group demographics. Focus Group Age Range 22 - 56 Gender Ethnicity Nationality Occupation Female Bangladeshi British Psychologist Male Pakistani British Psychiatrist Male Iraqi British Psychiatrist Female Turkish Turkish Student Female Turkish Turkish Student Female Turkish Turkish Student Female Turkish Turkish Student Male Black African British IT Professional Male Black African British Mental Health Professional Female Iranian Iranian Student Focus Group 2 Age Range 27 - 35 Gender Ethnicity Nationality Occupation Male Pakistani British Psychiatrist Male Pakistani British Psychiatrist Female Pakistani Pakistani Researcher Female Bangladeshi British Social Worker Female Indian British Lecturer Table 2. Meanings of radicalisation. Meanings of Radicalisation Participant Comments Specifically Used for Muslims Radicalisation is a term purely used for Muslim communities. (male2, group1) Never heard them associated with any other religions. (male1, group1) There are extremist Muslim groups, we are not denying that but the words are used exclusively with Islam. (male1, group3) The problem with the word extremism is used for specifically for Muslims and not for the British National Party who are very extreme and do commit violent crimes. (male2, group1) Associations with Violence and Terrorism Now these words are associated with Islam, Muslims, terrorism, pain and feeling unsafe. The words have powerful connotations. (female1, group1) And so my immediate association is that they are things, word association with terrorist, with anger. (female2, group2) Anything That is Seen to Be Culturally Foreign Radicalisation is seen as anything that does not fit in with any Western values or concepts. Anything that is not part of this country. (male1, group1) Anything that does not conform with Western ideas are seen as extreme and in an negative way. (male3, group1) Increased Religiosity Praying five times or covering your head and not talking/touching to guys which are personal beliefs makes you be seen as a strict or extreme Muslim. (female2, group1) There is something about people who are more religious than I am a little wary of. I see the beard, I see the dress, is see the veil, people who say God Willing too much. I just get a little bit nervous. (female1, group1)  P. GHOSH ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 293 Wellbeing of the Muslim Community There was heightened criticism of the media by participants saying those with extreme viewpoints were given dispropor- tionate representation at the expense of the wellbeing of the wider community. Whenever the press report on it, issues to do with Islam, they always have one kind of normal Muslim, and then they have to get a slightly extreme one. (female1, group2) Al Muhajiroun and Hizbut-Tahrir, two groups widely con- sidered by the Muslim community as holding extreme views, were highlighted as being given a greater platform than their actual influence in the Muslim Community. This created a ne- gative stereotype that all Muslims were extreme. People like Al Muhajiroun and others with extreme views always create friction for their own political benefit and use the media platform unfortunately which is offered to them. So they are over represented in the media compared to the majority of Muslims. (male3, group1) It was felt that Muslims had faced greater alienation and dis- crimination since 9/11, creating a sense of fear and anxiety. Some stated that since 9/11 they had directly experienced ra- cism for the first time and they were now exposed to racism on a more frequent basis. I remember I was working in a large international furniture store, I was doing my undergrad degree, and a customer com- plained about me because I was brown skinned and working behind the counter, and I shouldn’t be there because we are all terrorists. She actually put in a formal complaint about me, and there was another black girl who was working there, and she put a complaint against her as well. And that was my first ex- perience of racism, and yeah for me I started to experience more and more racism after 9/11. (female2, group2) Another participant described a sense of anxiety due to on- going discrimination demonstrated by a reported increase in hate crimes against Muslims. It was felt this climate of alien- ation and discrimination resulted in Muslims turning inwards to their own community to feel a greater sense of belonging and closeness to their Islamic identity. Some were now leading a more traditional and religious life. It’s like the whole racism thing as well, you know how you adhere more to your own communities or ideas. (female1, group2) Some participants stated that although they did not consider themselves to be strong Muslims, they found themselves iden- tifying more as Muslims to combat feelings of isolation from the wider community around them. It has made us feel we have to question ourselves but in a negative way. Not in a positive way, not kind of a spiritual growth it is a fear that we are different and don’t fit in with our neighbours. We are questioning ourselves and also worried about what our neighbours, what the people around are think- ing about us. (female1, group1) A similar theme was expressed by a male participant who had been forced to become more knowledgeable about Islam as he had to challenge viewpoints about radicalisation as well as respond to attacks on his faith. I think that after September 11th, there was a shift in the wider Muslim community, that everyone was forced to take that position where you became more defensive. I found myself hav- ing to…whereas before I didn’t care about Islam, I wouldn’t feel the need to talk about it particularly at all, whereas people wanted my opinion about terrorism and about where I thought it came from, and suddenly I found I had to be knowledgeable about it and I had to have an opinion about it. (male2, group2) The same participant also noticed the wider Muslim commu- nity (giving his parents as an example) harboured a sense of fear regarding the wider process surrounding radicalisation and as a result becoming more observant of their faith. And I feel that communities have felt they are kind of threat- ened by it, and what I’ve seen happen is that even people who might be described as moderate Muslims, everyone has to take a position and their views kind of shift subtly. So my parents for example, they started to…they became more religious as a re- sult of it, they thought this is something important we have to…maybe as a defence against that kind of terrorism, they wanted to say we are proper Muslims, we’re doing these things the right way, and people started to go to the mosque more. (male2, group2) Pathways and Psychological Processes of Radicalisation 1) Misinterpretations of Islamic Teachings It was suggested that radicalised groups took advantage of the ambiguity in the translations of Islamic texts and thereby purposefully misinterpreted Islamic teachings. If you start reading the different kind of translations that ex- ist, there’s a lot of disagreement with translations. Not that ambiguous, but there is ambiguity. So again it depends, how it is being interpreted, in certain context. (female3, group2) Groups such as Al Muhajiroun misinterpret certain verses that don’t agree with their own views. (male2, group1) It was thought that a general lack of knowledge of the key fundamental principles of Islam amongst the Muslim commu- nity played a part in misunderstanding of the true spirit of Islam. This allowed pseudo-scholars to misinterpret religious texts leading to the indoctrination of younger people. Brainwashing tends to happen at an earlier age. You go to someone and ask for an interpretation of Islamic verse or story and it’s that misinterpretation that fuels that person. I think one of the issues of the Muslim community is that they are not edu- cated about Islam. (male1, group1) Another point highlighted was the language barrier. It was felt some Muslims were unable to fully understand Islamic sources and therefore have only a superficial grasp of Islamic concepts because they lacked knowledge of Arabic and thus took at face value the misinterpretations of others. Socio-Economic Inequalities There was disagreement amongst participants about whether inequalities played a part in radicalisation. Some felt depriva- tion, disadvantaged backgrounds, and poor education created psychological vulnerabilities in young people allowing them to be radicalised. The main reason why people turn to any kind of crime or violence is due to deprivation, lack of education and poverty, and poor parenting. I personally think that these people have nowhere to go and all of a sudden they find a bunch of people they feel a part of, like being a part of a family; and they will make sacrifices as they have nothing to live for anyway. It’s poor self-confidence, poor self-worth, low self-esteem. (female2, group2)  P. GHOSH ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 294 I think that subtle wider community mind shift is something which has played out in those vulnerable people, whether that is through deprivation or poverty, or people who are more psychologically vulnerable and more inclined to hold extreme views, and it’s pushed them into that. (female3, group2) Parallels were also drawn between the 7/7 bombers and those taking parts in the London riots. It was felt that the London riots were also a result of deprivation, economic hardship and a lack of access to education. When the London riots happened, oh it’s because of these children, you know, they’ve got no hope, they’re deprived, and tuition fees are going up and therefore they did this because they’re desperate. That to me, is a similar argument for the 7/7 bombers, it kind of feels like, well no actually hang on a minute, yeah there are these issues going on when there is economic hardship. (female1, group2) This was countered by others who highlighted the fact many misled young people who held extreme views were well edu- cated and from relatively well-off backgrounds and had not experienced any major personal traumas or adversity. When you look at most of those people who committed these acts or atrocities, they were educated to degree level qualifica- tions. It’s not just a particular kind of naïve people from the village. (male4, group1) And I think we have to ask what made those people? Many are highly educated, good background, and I know, I mean I completely agree that there are maintaining factors, there is deprivation, what happens in their families, but you would be surprised many of them who have been accused of these acts, they were otherwise described as very reasonable, very normal. (male1, group2) Tackling Radicalisation as a Means to Promote Social Cohesion 1) Challenging Ideology through Islamic Values Improved Islamic education highlighting Islamic principles based on authentic sources was thought an effective way to combat radicalisation. One participant highlighted that the Quran states that killing innocent civilians is prohibited (Haram) thus implying that using any acts of violence were against Islam. Every Muslim also knows that suicide killing an innocent ci- vilian is haram, it is clearly written in the Quran. (male2, group1) Another participant stated the Sunnah (practices, sayings and tacit approvals of the Prophet Muhammed) expected Muslims to adopt the middle path and not to stray away from this path which may lead to extreme beliefs. His path, the Prophet said in the Sunnah is the middle path which teaches tolerance and from the middle path, the sub paths emerge which are evils thus straying away from the mid- dle path is like extremism. (male3, group1) It was felt the promoting the true meaning of Jihad in its wider context could be used to challenge extreme violent ide- ologies because in Islamic teachings Jihad can only be carried out under certain conditions and did not allow for the killing of unarmed innocent civilians. Say if you look at rules of Jihad, Islam has got a complete doctrine of Jihad which is basically about principles of war. And there are certain conditions which are laid down very ex- plicitly. So say, for example, it has to be authorised by a le- gitimate ruler of the state. You cannot kill someone who has surrende red, you cannot kill someone who is unarmed, you can- not kill a woman, you cannot kill children, you cannot destroy crops, you cannot destroy trees, you cannot destroy buildings. (male1, group2) 2) Fairer and More Inclusive Society To combat radicalisation, it was argued that there needed to be a focus on greater integration between different communities with a broader education strategy aimed at the younger genera- tion. Coming from Bristol to London, you know it’s very segre- gated, and there is not enough being done to integrate commu- nities together. Even in terms of mosques, there’s a separate mosque for every community, so you know, I think people need to integrate. And people need to learn about each other, there isn’t enough psychosocial education out there. (female2, group2) Participants felt the onus for integration was often placed upon Muslims alone and that all communities needed to be actively involved in the process of integration. It was indicated that Muslims often felt they were unwelcome and thus could not integrate. But integration needs to be from all sides. (female1, group2) I think it’s not just a one way process of, oh Muslims don’t integrate, I think you need to feel like you are wanted to inte- grate. (female1, group2) Inequalities were not thought to be limited to the Muslim community and that general social inequalities between rich and poor led to deep divisions based along class lines. Conse- quently subjects said that a fairer and inclusive society, one that promoted a greater redistribution of wealth, would go some way to tackling to help tackling radicalisation. It is not just the Muslim community that’s a victim of depri- vation etc. there are these wider social issues which have noth- ing to do with Muslims or Islam, but are much more to do with how the state is structured, the nature of the fact that people go to…the way London I guess is set up, with these really big di- vides between rich and poor. That people feel the need to find some community so they all go together in one area, that is a way I guess of providing that validation. (male2, group2) Acceptance and Representation There also needed to be greater acceptance by the Muslim community of the existence of a problem involving radicalised individuals and organisations and this may result in greater chance of actively tackling radicalisation. So I think the people should stop denying that there is no problem because there is a problem. Again you can talk…until unless you acknowledge that, you can’t do something about it. (male1, group1) Unfortunately there are a lot of people in the Muslim com- munity who bury their heads in the sand and say these people don’t exist. They do exist. (male3, group1) The Muslim community also had to make they were properly represented by limiting the influence of voices considered ex- treme and who misrepresent Islam. One of the things they have to do is to get rid of self-pro- claimed Muslim community leaders. There are people inside Muslim communities in Britain who are just very much vocal about their views, and they just happen to get more attention, and there is a vast majority. (male1, group2) The participants strongly believed that the media had to be more responsible in reporting Muslim issues and be more ac-  P. GHOSH ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 295 curate in their representation of Muslims. So I guess there’s maybe educational work in terms of the media and how they portray that, and where they go to look for Muslim voices. (female3, group2) And I guess separating Islam, so for example, if on behalf of media and people who talk about it, rather than labelling that as a version of Islam, I think it would be helpful to label that as what it is, which is Al Qaeda, which is Taliban, which is Wahhabis. (male1, group2) Discussion Meanings of Radicalisation The focus groups felt radicalisation radicalisation was a term that was associated with Muslims with connotations of terror- ism and violence. This relationship between Islam and violence was seen by Langhor (2004) who believed use of the term radical Islamist was a euphemism for violent Islamist. It was felt that the wider community viewed anything that was culturally foreign to this country as being radical. This view that Islam is at odds to the Western way of life was described by Kirkby (2007) who argued wider society saw radical Muslims as being a danger to their cultural and political values. Research done by Gallup (2009) solidified this belief showing that over a quarter of British people believed that Islamic religious practices threa- tened their way of life. Wellbeing of the Muslim Community The focus group subjects suggested that media coverage was Islamophobic magnifying the influence of radical organisations such as Al Muhajiroun. The UK Islamic Human Rights Com- mission (2009) have argued that the media legitimised the voice of those who held extreme beliefs by focusing on fringe groups that the majority of Muslims found unacceptable. The core aim of Al Mujahroun, a group that has been repeatedly banned and so it operated under different disguises, was to overthrow the British Government for the formation of an Islamic Caliphate and implementation of an extreme interpretation of Shariah law (Briggs & Birdwell, 2009). However, focus group participants distanced themselves from these aims and felt they were not in keeping with the wishes of the wider and majority Muslim community. Participants themselves felt a growing sense of alienation since September 11th citing both personal and the Muslim communities’ experiences of discrimination and hostility caus- ing feelings of fear and anxiety. Clearly experiences of dis- crimination may make Muslims more vulnerable to developing mental illness as well as undermine their feelings of wellbeing (Karlsen & Nazroo, 2002; Williams et al., 2003). There was a noticeable increase in expression of a religious identity in the Muslim community with greater attendance at mosques and Islamic forms of dress. These changes were thought to be a response to a need to belong and a sense of anxiety due to growing alienation and more discrimination. This increase in a Muslim, as opposed to British, identity was seen in work done by the Pew Institute (2006) who stated that more than three quarters of British Muslims saw an increasing sense of a reli- gious identity amongst their community. Some in the focus group felt females who had adopted an increased Muslim iden- tity found their freedoms curtailed. This in contrast to a study done by Glynn (2002) in East London where Bengali females believed by drawing on their religious identity they were able to gain greater personal freedoms. Whilst Bhui et al. (2008) also in East London found that Bengali Muslim girls who expressed a more traditional identity in terms of their clothing were less likely to suffer from emotional distress. Soriano et al. (2004) found a stronger sense of ethnic identity amongst minorities in the US was protective against violence. Sociological and Psychological Processes of Radicalisation There was a feeling that deprivation resulted in hopelessness and a lack of belonging in young people resulting in low levels of self-esteem and poor confidence and that this in turn made them vulnerable to radicalisation. These thoughts fall in line with Gurr (1970) who cited that relative deprivation created a psychological discomfort causing rebellion. In support of this inequality theory Bloomberg (2004) found a direct association between economic decline of a nation and the occurrence of terrorist activity. There is also clear evidence that Muslims suffer from significant levels of socio-economic deprivation in the UK. One third of Muslims of working age have no qualifi- cations, the highest proportion for any faith group while unem- ployment amongst British Muslims is three times the national average (Choudhary et al., 2005). However, the inequality hy- pothesis for radicalisation was challenged by participants in our focus group study; they highlighted that recruits into radical Muslim organisations were often well educated and from rela- tively well-off backgrounds. Krugger and Malečková (2009) found Hizbullah recruits had higher than average educational attainment whilst in the West Bank and Gaza wealthier mem- bers of the community were likelier to advocate violent action. In the UK those convicted of terrorist related offences are simi- lar in their socio-economic profile to the wider public. There was agreement in the focus group that extremists mis- interpreted teachings from Islamic teachings taking advantage of the lack of religious literacy in the Muslim community. A similar viewpoint was expressed by Choudhary (2007) who argued that young British Muslims were less able to resist ex- treme Islamic doctrine because they lacked the religious educa- tion and that foreign-born Imams found it difficult to counter the message of extremists as they themselves did not know English and could not relate to the experiences of Muslims who were born and brought up in the UK. Tackling Radicalisation as a Means to Promote Social Cohesion The groups felt that reducing inequalities and promoting in- tegration would allow Muslims and the wider community to live in a fairer and more inclusive society enhancing wellbeing and cohesion. Educational strategies aimed at the younger gen- eration to inform them of other cultures were thought to be a strategy to promote mutual respect and integration. Furthermore, integration can improve educational opportunities, yet currently, in high Muslim population areas such as Bradford and Black- burn, young people are attending schools which are over 90% Muslim (Burgess & Wilson, 2004). Segregation along ethnic lines was also seen as the root cause of violent disturbances in former mill towns involving Muslims and white working class youths (Cantle, 2001). There was agreement that challenging extremist organisa-  P. GHOSH ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 296 tions that perpetuate violent ideologies using legitimate Islamic scriptures and warning against extremism, preaching tolerance and forbidding the killing of innocent civilians was an effective way of combating radicalisation. The view that Islamic educa- tion can reduce radicalisation can be seen from the idea that increased religiosity results in individuals rejecting violence due to fear of moral and ethical wrongdoing created by follow- ing their religion properly (Taarnby, 2005). All interventions may attract criticism from one or other sec- tors of society. The Prevent strategy itself has been criticised for its mono-cultural focus on the Muslim community leading its members to feel that they have been singled out as a threat (Kundani, 2009). There has also been criticism from white working class communities that large amounts of public re- sources are being used on projects and organisations purely for use by Muslims(An-Nisa Society, 2009) with some funds sup- porting radical Muslim groups that oppose British political and social systems and so undermining social cohesion (Maher & Frampton, 2010). Limitations A weakness of the study was that in the first focus group there was recruitment of overseas female students who had not resided in the United Kingdom for a lengthy period of time. This was rectified in the second focus group by specific snow- ball sampling aiming to recruit females who had been living in the country for more than five years. Another issue was there was a clear age gap in the first focus group between male and female participants that may have resulted in some female par- ticipants finding it more difficult to speak up amongst elders. Older participants and men did speak more often. The vast majority of participants were residing in the London area with little representation from Muslims living elsewhere in the coun- try. There was an absence of converts to the Islamic faith, and this group is important given that one-fifth of convictions for terrorism relate to converts (Roy, 2008). It may have been dif- ficult to garner the true opinions of individuals in a focus group as participants are unlikely to disclose viewpoints that are ex- treme or in support of violence for fear of possible prosecution and expressing opinions that are different from the majority of participants. There was varied representation of different eth- nicities and religions amongst the researchers, with both non- Muslims and Muslims having input but any bias borne out of an individuals’ background and beliefs has to be considered. Conclusion Islamophobic media coverage, alienation and discrimination affected the wellbeing of the Muslim community, resulting in more orthodox religious identity and practice. This intensifica- tion may make such youth vulnerable to radicalising influences. Drivers of radicalisation were perceived to include inequalities and misrepresentation of Islamic teachings. Solutions to tackle radicalisation in order to promote social cohesion included authentic Islamic education, increased integration, reducing ine- qualities and greater acceptance by the Muslim community alongside more responsible journalism. Although further work can be undertaken and is needed in Muslim communities, there also needs to be work done on non-Muslim communities, to assess the impact of extremism on social cohesion and wellbe- ing. Acknowledgements Priyo Ghosh assembled and ran the second focus group, analysed the data for both focus groups as part of his MSc The- sis and completed the first draft. Nasir Warfa helped design the study and secure ethics approvals, chaired the Community panel to help aid recruitment, ran the first focus group and supervised Priyo Ghosh’s MSc thesis. Angela McGilloway helped with the second focus group and analysis of the data. Imran Ali worked to engage with community panel to assemble the focus groups, and commented on drafts of the thesis, offering specific Islamic insights on the data. Edgar Jones designed the study and help secure ethics approvals as part of a large mixed methods study of radicalisation. Kamaldeep Bhui was lead investigator, de- signed the study and secured ethics approvals as part of a large mixed methods study of radicalisation, worked to engage with the community panel to assemble the focus groups, ran the first focus group and edited the final draft. These drafts were then reviewed by all authors who commented on a final version. There were no sources of funding or conflicts of interest. REFERENCES An-Nisa Society (2009). Memorandum from An-Nisa Society (PVE39), for parliamentary select committee on communities and local gov- ernment. House of Commons. London: The Stationery Office Lim- ited. Bakker, E., & Donker, T. H. (2006). Jihadi terrorists in Europe: Their characteristics and the circumstances in which they joined the jihad: An exploratory study. The Hague: Netherlands Institute of Interna- tional Relations Clingendael. Bhui, K., Hicks, M., Lashley, M., & Jones, E. (2012). A public health approach to understanding and preventing violent radicalization. BMC Medicine, 10, 16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-10-16 Bhui, K., Khatib, R., Viner, E., Klineberg, E., Clark, C., Head, J., & Stansfeld, S. (2008). Cultural identity, clothing and common mental disorder: A prospective school-based study of white British and Bangladeshi adolescents. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62, 435-441 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.063149 Blomberg, S. B., Hess, G. D., & Weerapana, A. (2004). Economic con- ditions and terrorism European. Journal of Political Economy, 20, 463-478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2004.02.002 Briggs, R., & Birdwell, J. (2009). Radicalisation among Muslims in the UK. MICROCON Policy Working Paper 7, Brighton: MICROCON. Burgess, S., & Wilson, D. (2004). Ethnic mix: How segregated are English schools? Bristol: Centre for Market and Public Organisation. Cantle, T. (2001). Community cohesion—A report of the independent review team. London: Home Office Choudhury, T., Malik, M., Halstead, J. M., Bunglawala, Z., & Spalek, B. (2005). Muslims in the UK: Policies for Engaged citizens. OSI/ EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program, London. Choudhury, T. (2007). The role of Muslim identity politics in radicali- sation commissioned by the preventing extremism unit. Department of Communities and Local Government. Gallup Coexist Index (2009). A global study of interfaith relations. With an in-depth analysis of Muslim integration in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Washington DC: Gallup Poll Consulting University Press. Glynn, S. (2002). Bengali Muslims: The new east end radicals? Ethnic and Racial Studies, 25, 980. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0141987022000009395 Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2004) Qualitative methods for health re- search (2nd ed., pp. 198-202). London: Sage Publications. Gurr, T. R., & Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs (1970). Why men rebel. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.  P. GHOSH ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 297 Hicks, M. H., Dardagan, H., Bagnall, P. M., Spagat, M., & Sloboda, J. A. (2011). Casualties in civilians and coalition soldiers from suicide bombings in Iraq, 2003-2010: A descriptive study. Lancet, 378, 906- 914. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61023-4 Islamic Human Rights Commission (2012) Annual report 2009-2010. http://www.ihrc.org.uk/attachments/9486_IHRC-Annual%20Report- V08.pdf Karlsen, S., & Nazroo, J. Y. (2002). The relationship between racial discrimination, social class and health among ethnic minority groups. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 624-631. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.92.4.624 Kirkby, A. (2007). The London bombers as “self-starters”: A case study in indigenous radicalization and the emergence of autonomous cliques. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 30 , 415-428. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10576100701258619 Krugger, A., & Malečková, J. (2003). Education, poverty and terrorism: Is there a causal connection? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17, 119-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/089533003772034925 Kundani, A., & Institute of Race Relations (2009). Spooked: How not to prevent violent extremism. London: Institute of Race Relations. Lunt, P., & Livingstone, S. (1996). Rethinking the focus group in media and communications research. Journal of Communication, 46, 79-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1996.tb01475.x Maher, S., & Frampton, M. (2009). Choosing our friends wisely: Crite- ria for engagement with Muslim groups. Policy Exchange, London. Mir, A. (2012). Ten years after 9/11: Suicide attacks declining in Paki- stan. http://www.thenews.com.pk/TodaysPrintDetail.aspx?ID=67173&Cat=2 Pew Institute (2012). Global attitudes survey. http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/counter-terrorism/prvent /prevent-strategy/prevent-strategy-review?view=Binary Roy, O. (2008). Islamic terrorist radicalisation in Europe. In S. Amghar, A. Boubekeur, & M. Emerson (Eds.), European Islam. Challenges for public policy and society. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies. Silke, A. (2008). Holy warriors: Exploring the psychological process of jihad radicalization. European Journal of Criminol ogy , 5, 99-123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1477370807084226 Soriano, F. I., Rivera, L. M., Williams, K. J., Daley, S. P., & Reznik, V. M. (2004). Navigating between cultures: The role of culture in youth violence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34, 169-176. Stern, J. (2003). Terror in the name of God: Why religious militants kill. New York: Ecco. Taarnby, M. (2005). Recruitment of Islami s t terrorists in Europe: Trends and perspectives. Aarhus: Centre for Cultural Research, University of Aarhus. Tessler, M. (1997). The origins of support for Islamist movements. In J. Entelis (Ed.), Islam, democracy, and the state in North Africa . Bloom- ington: Indiana University Press. Williams, D. R., Neighbors, H. W., & Jackson, J. S. (2003). Racial/ ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 200-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200

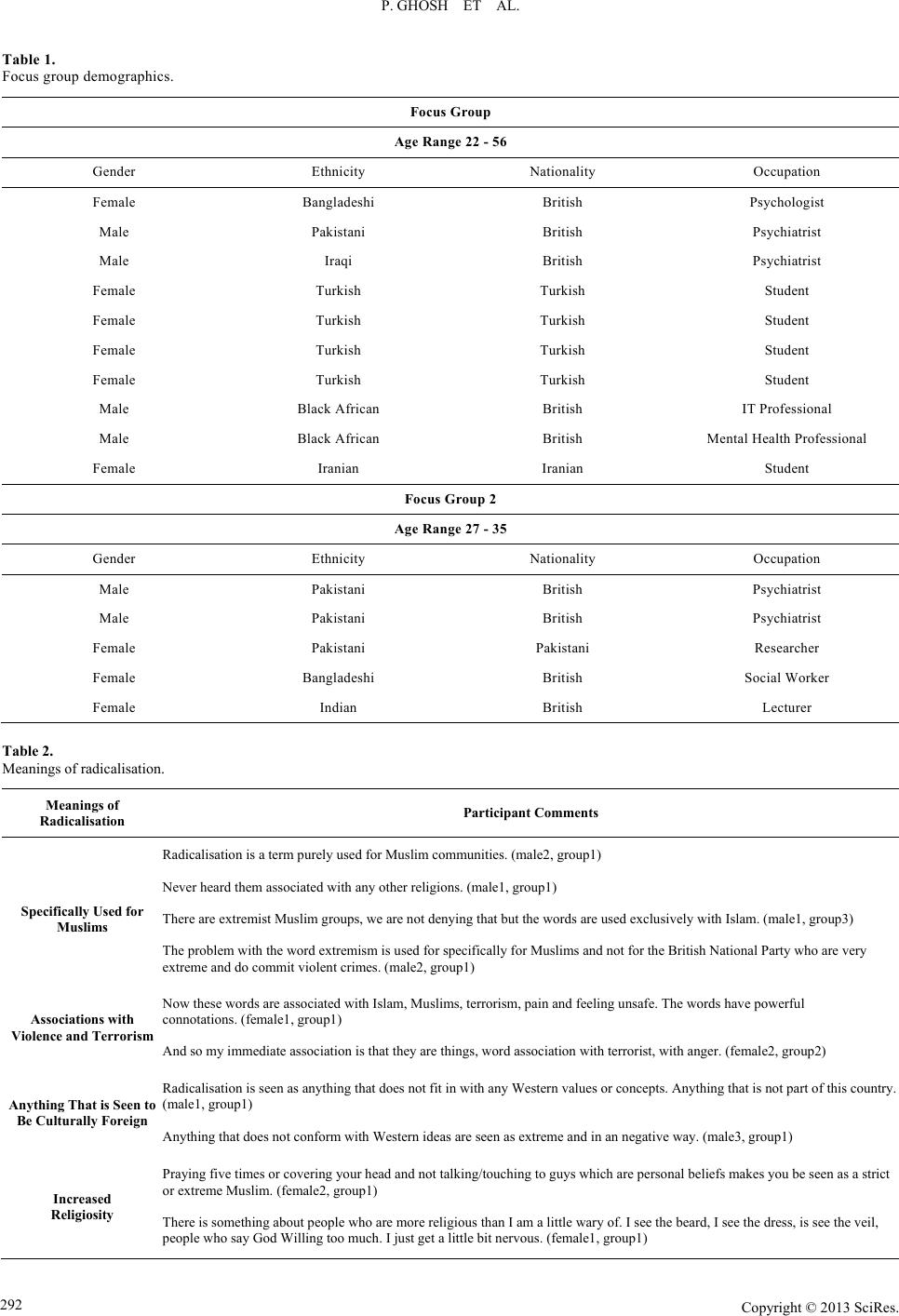

|