Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

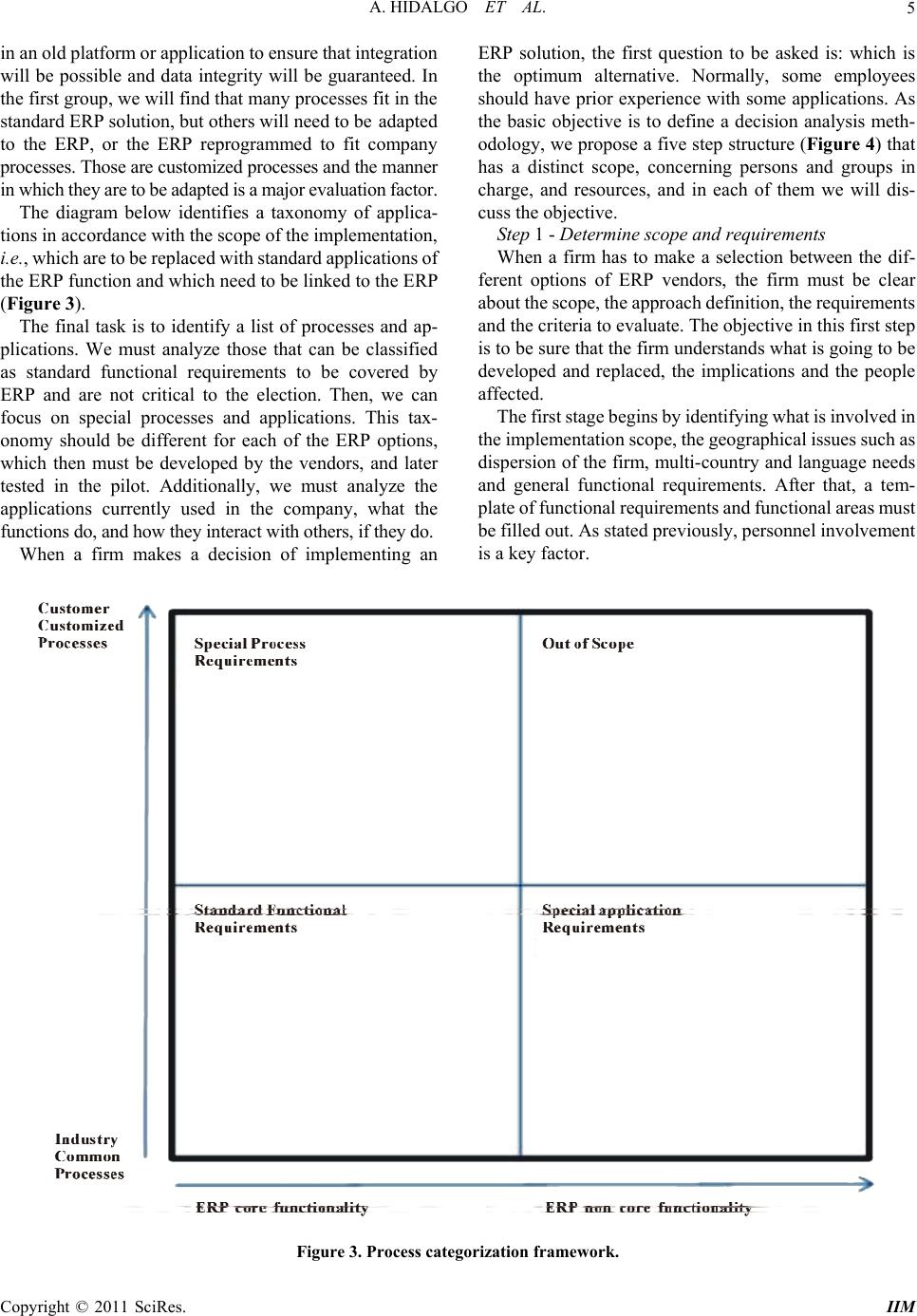

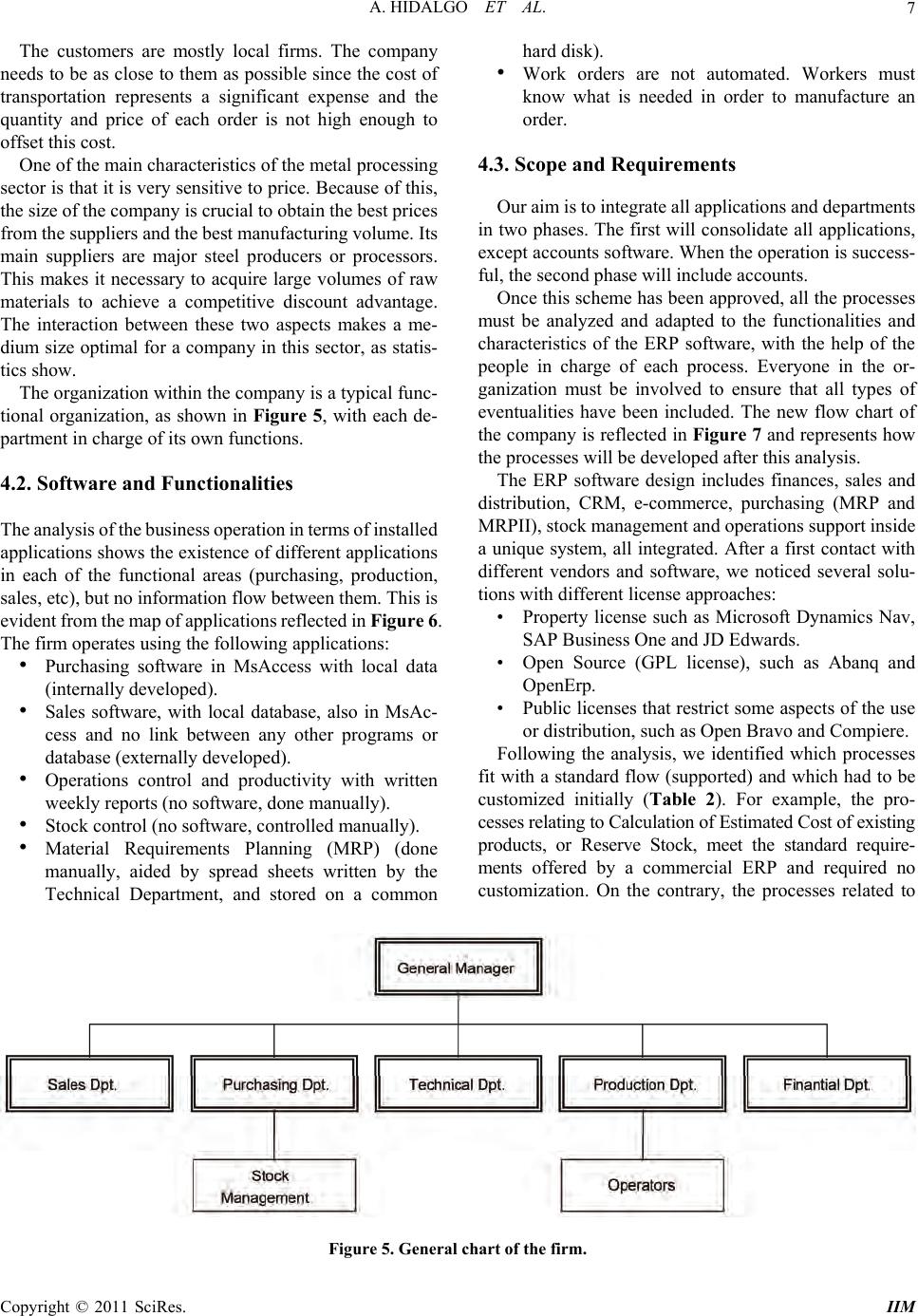

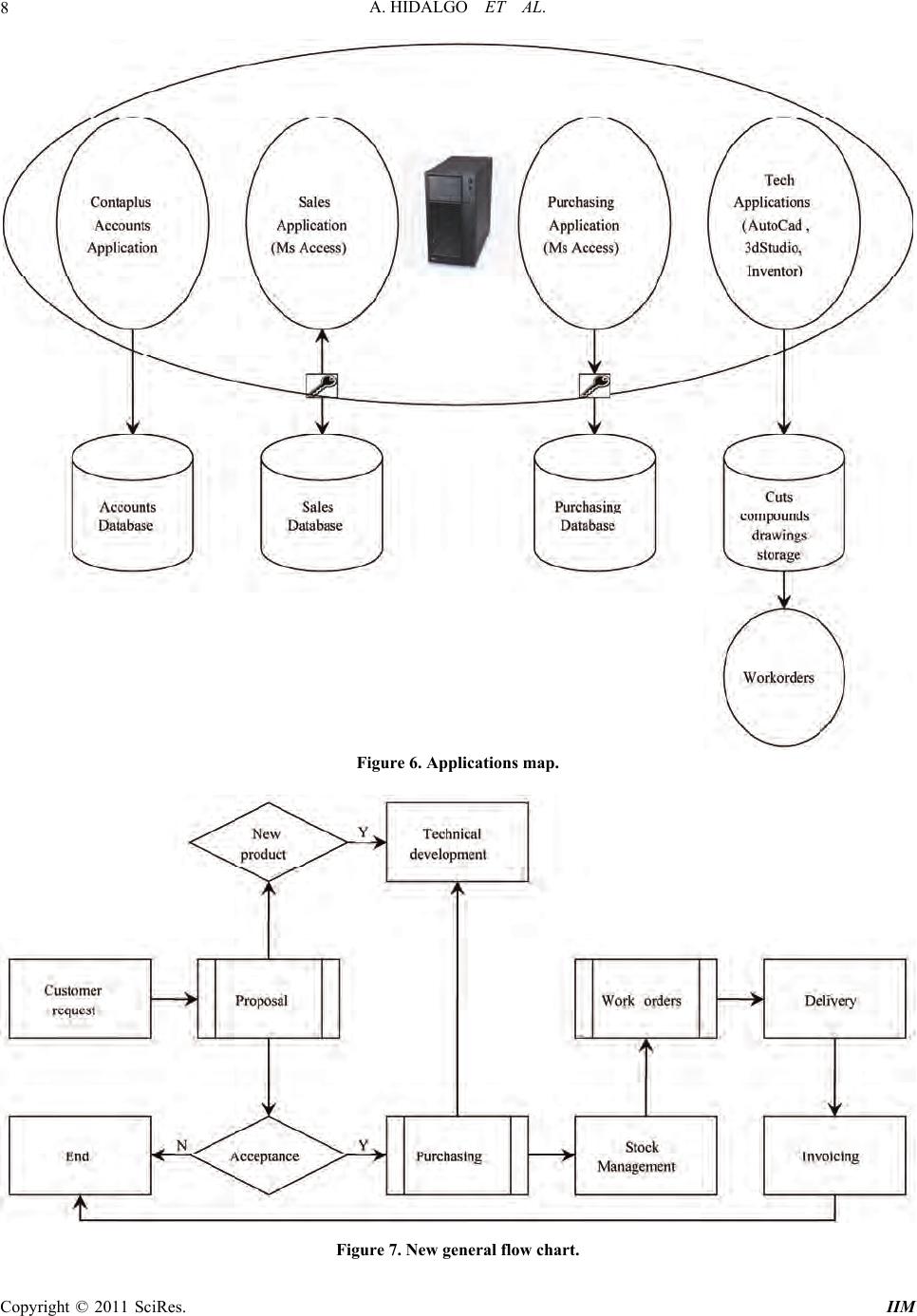

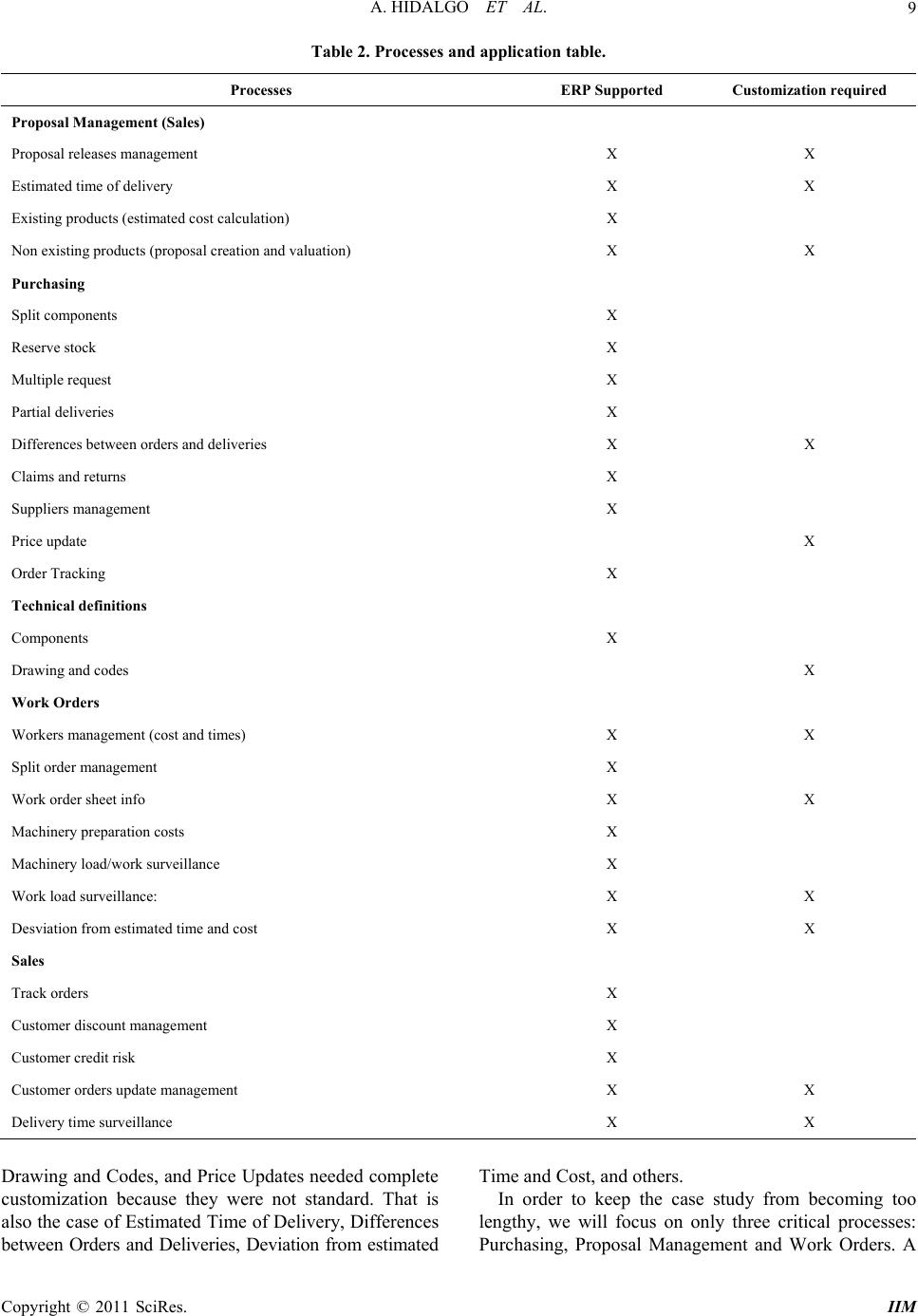

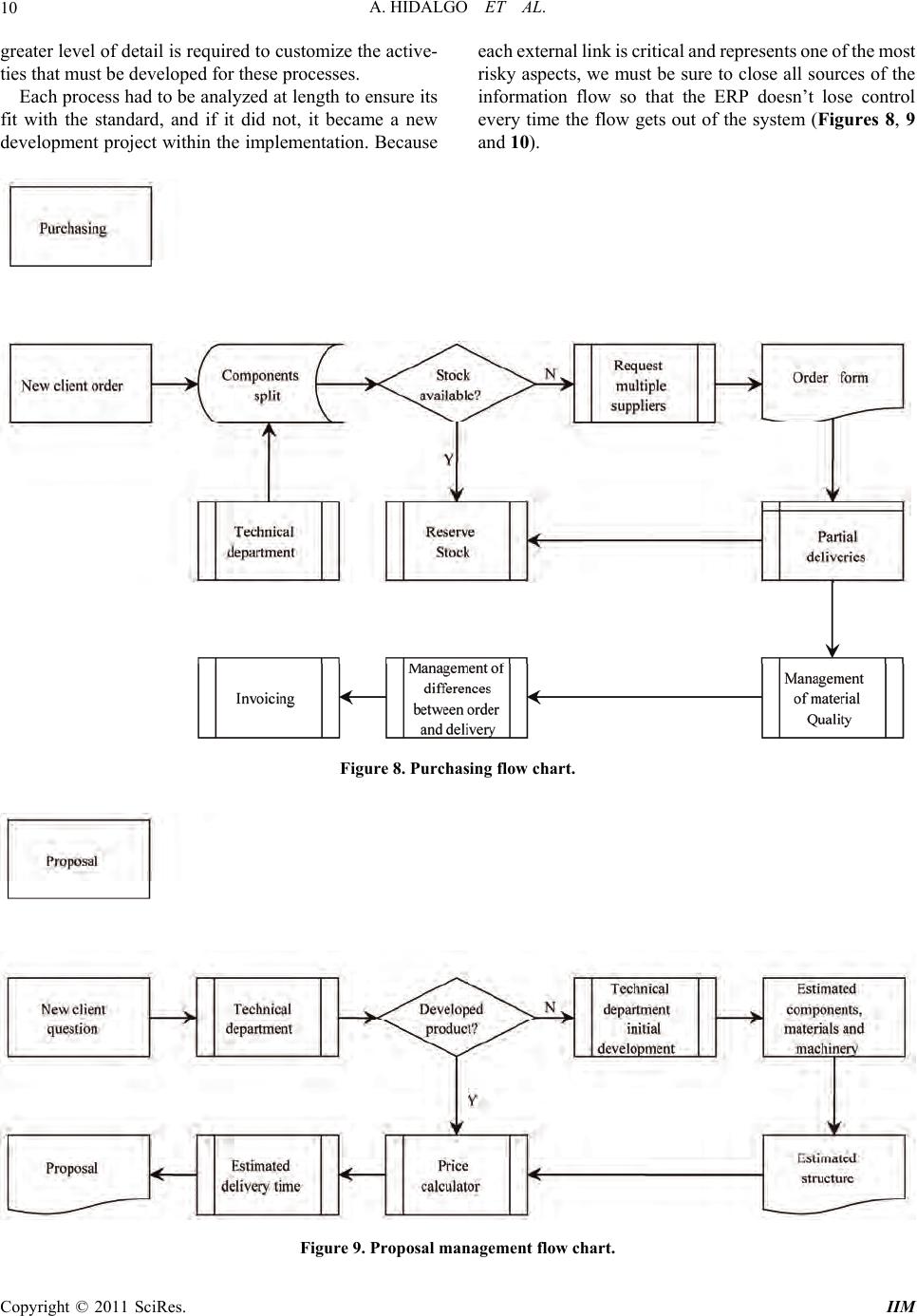

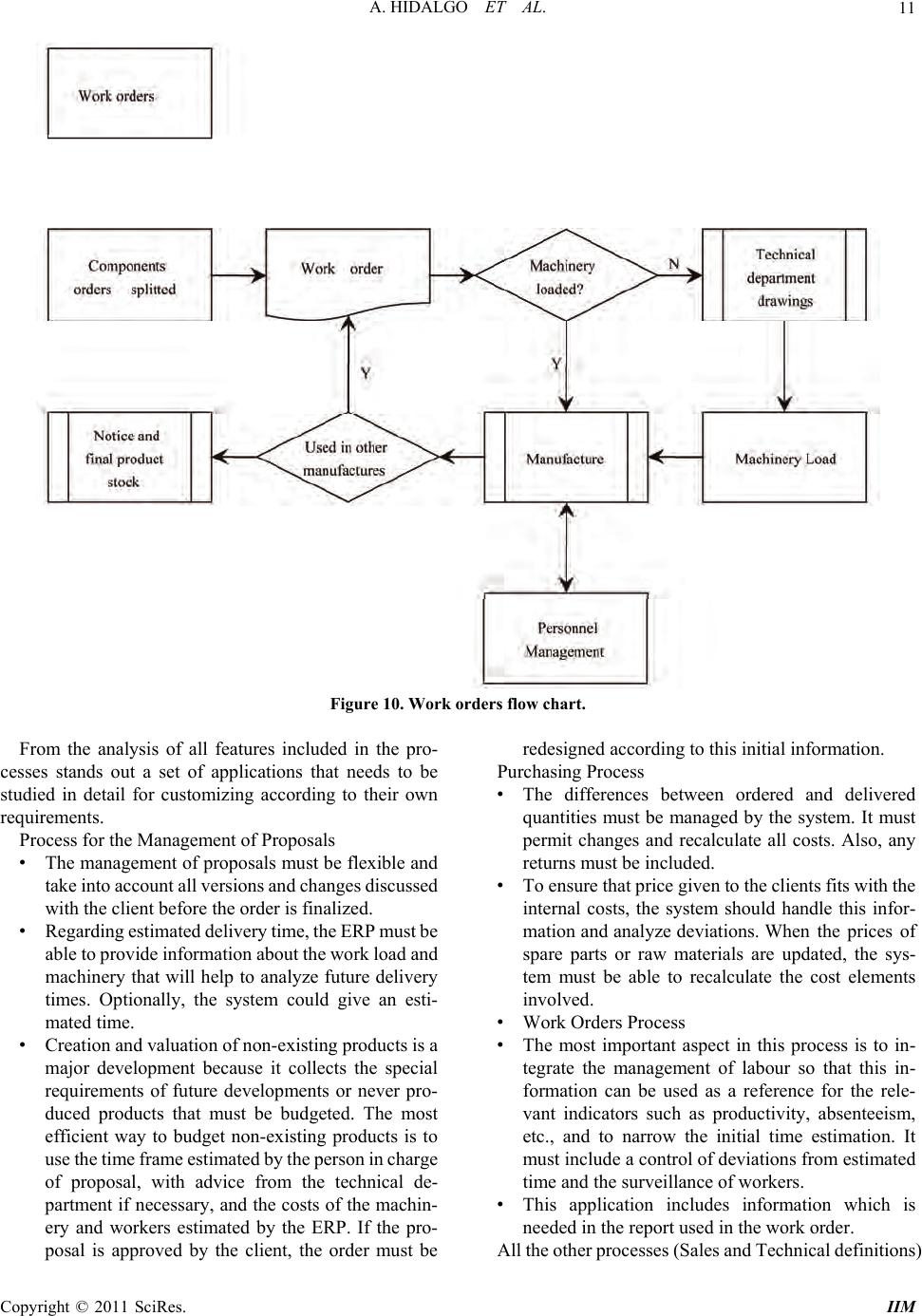

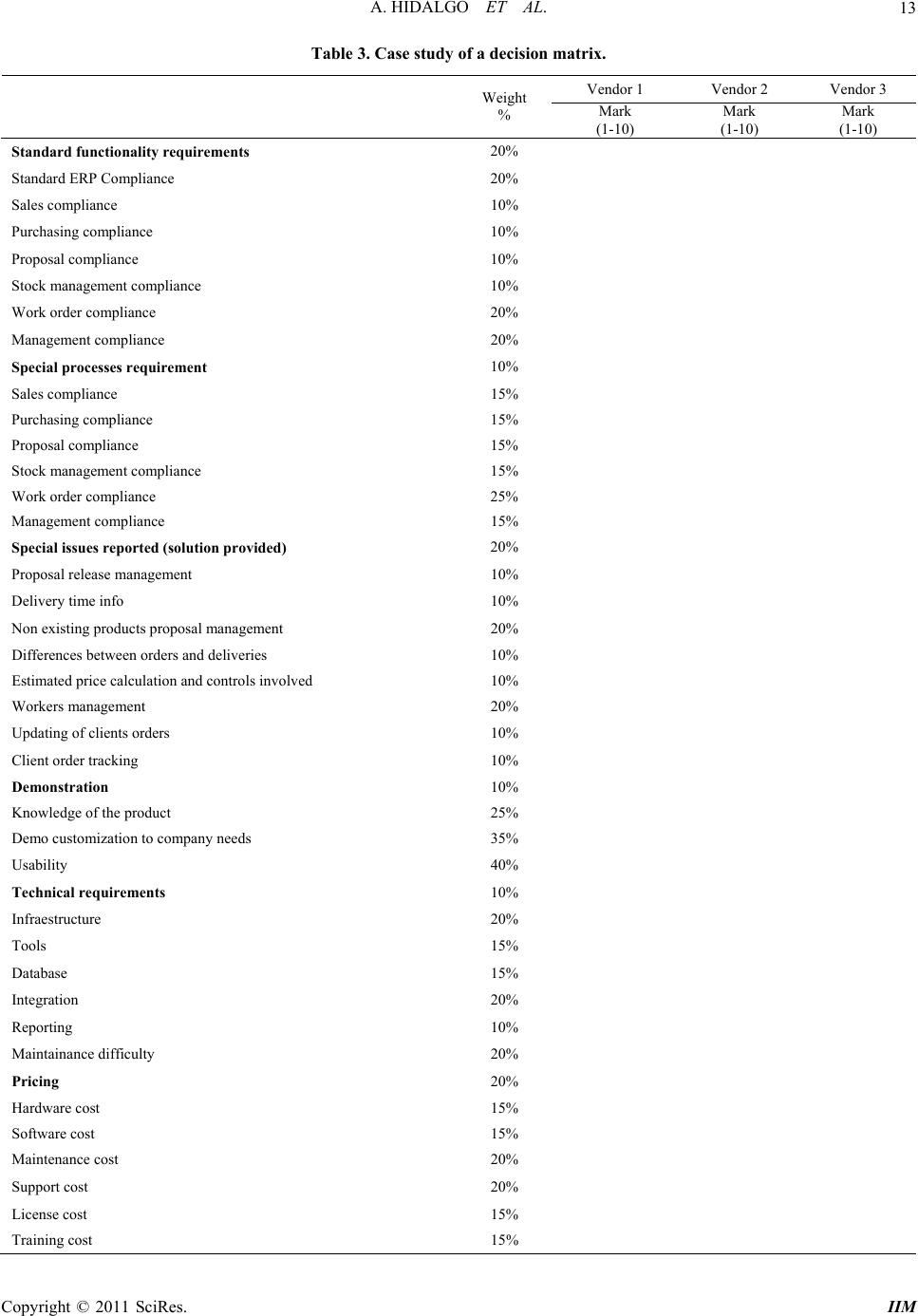

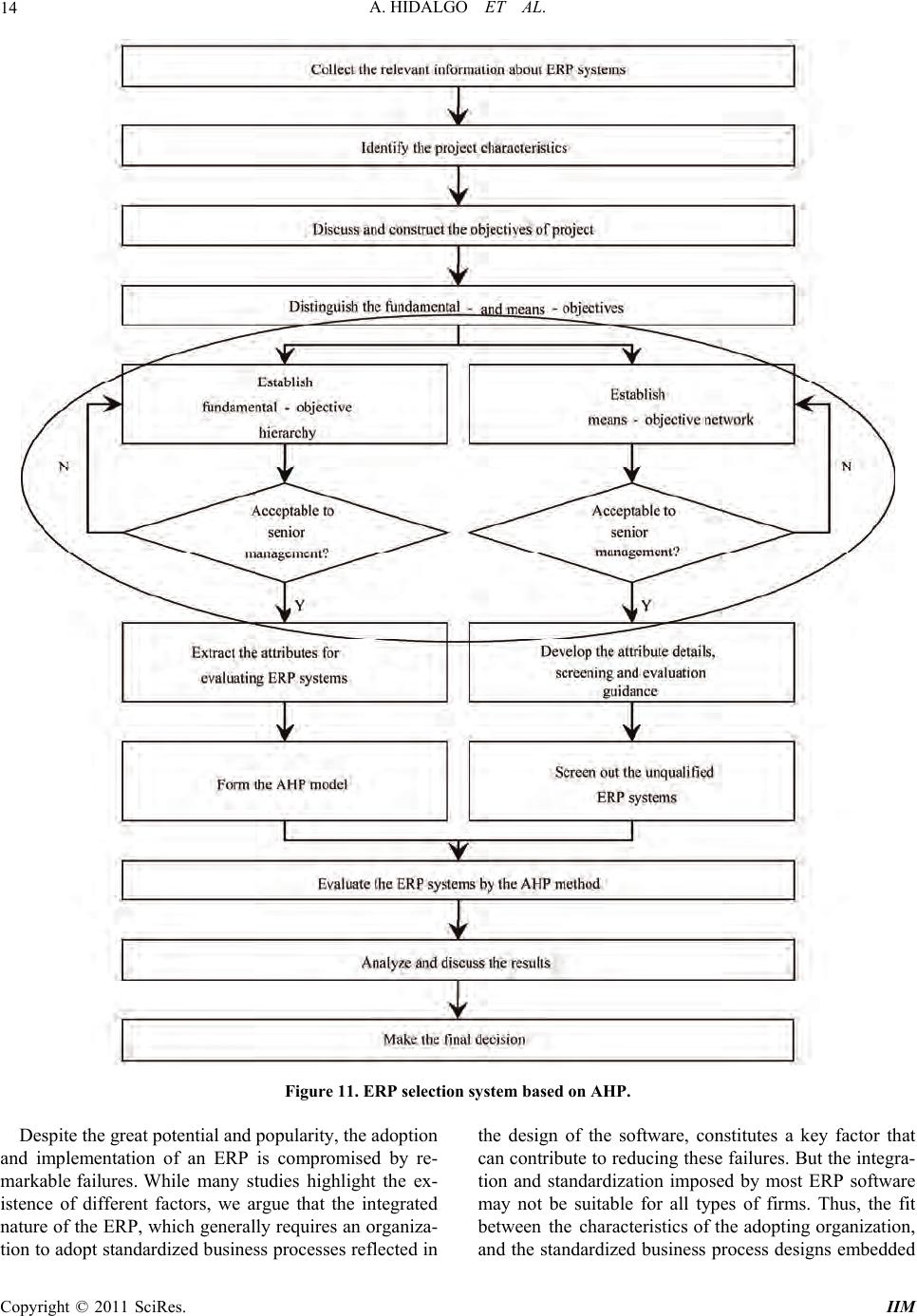

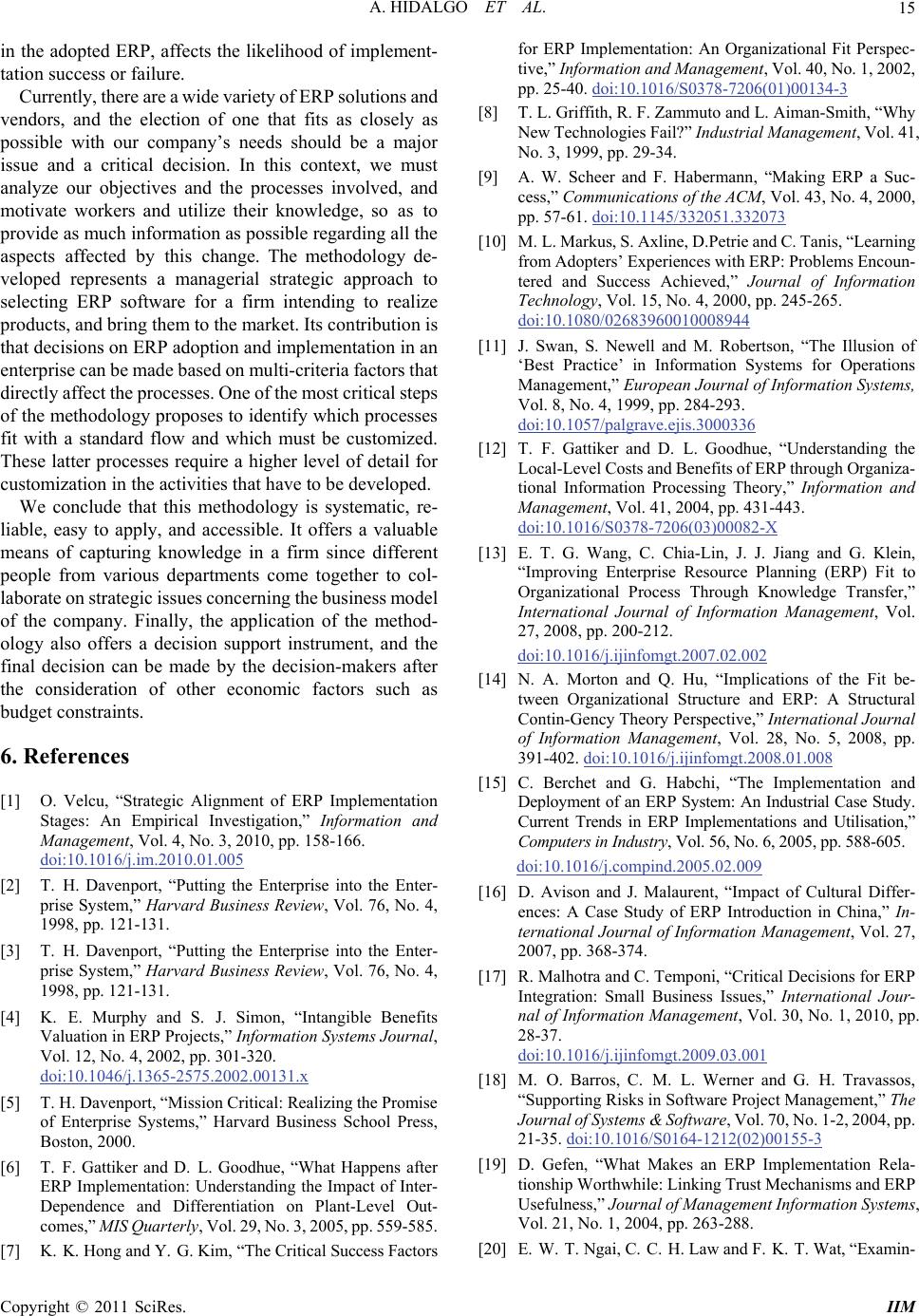

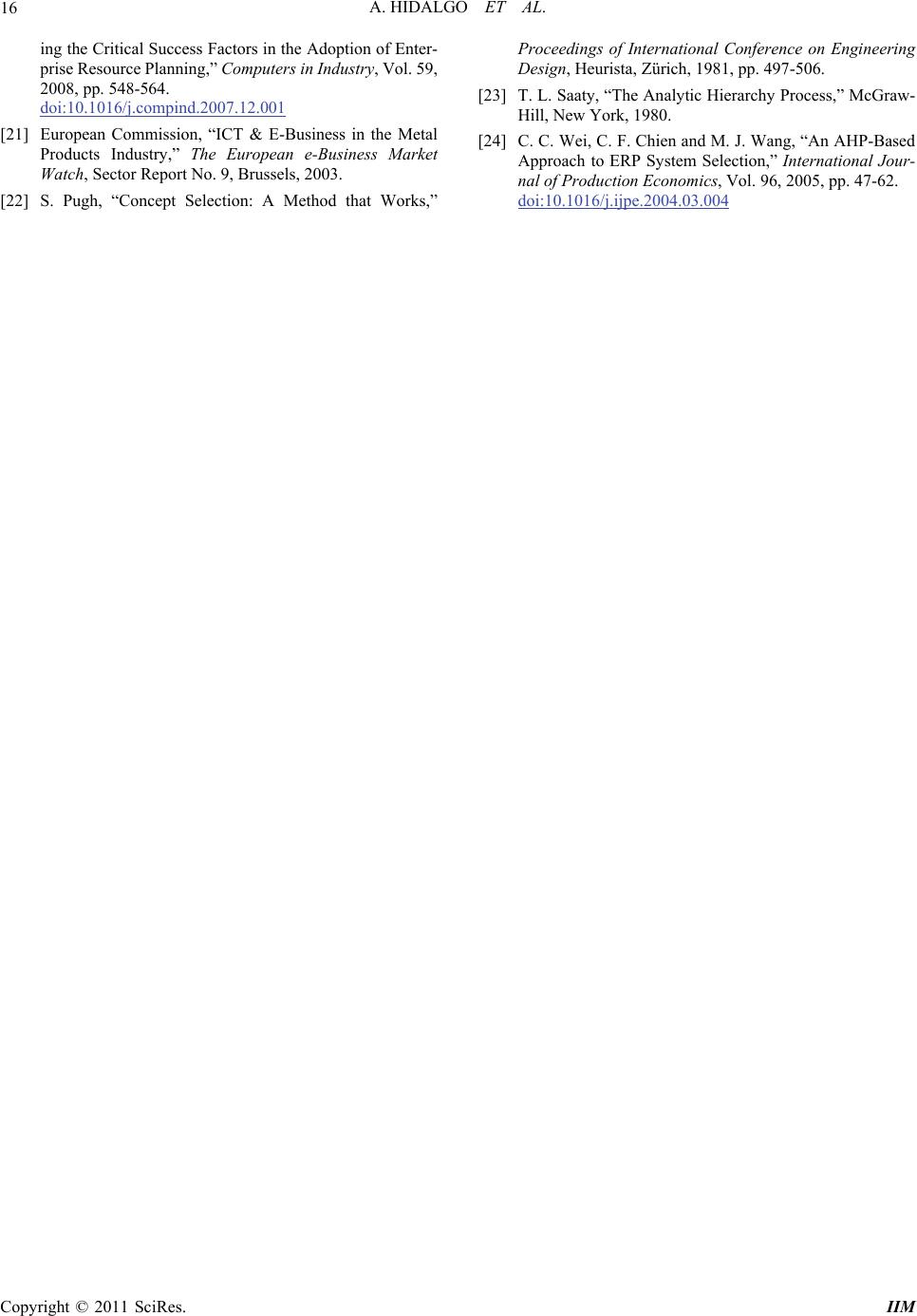

Intelligent Information Ma nagement, 2011, 3, 1-16 doi:10.4236/iim.2011.31001 Published Online January 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/iim) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM ERP Software Selection Processes: A Case Study in the Metal Transformation Sector Antonio Hidalgo1, José Albors2, Luis Gómez3 1Department of Busi ness Administration, Universidad Poli t écni c a de Ma drid, Madrid, Spain 2Department of Busi ness Administration, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia, Spain 3EMVS, S.A., Madrid, Spain E-mail: ahidalgo@etsii.upm.es, jalbors@omp.upv.es, gomezl@emvs.es Received December 13, 2010; revised January 8, 2011; accepted January 11, 2011. Abstract When a firm decides to implement ERP softwares, the resulting consequences can pervade all levels, includ- ing organization, process, control and available information. Therefore, the first decision to be made is which ERP solution must be adopted from a wide range of offers and vendors. To this end, this paper describes a methodology based on multi-criteria factors that directly affects the process to help managers make this de- cision. This methodology has been applied to a medium-size company in the Spanish metal transformation sector which is interested in updating its IT capabilities in order to obtain greater control of and better infor- mation about business, thus achieving a competitive advantage. The paper proposes a decision matrix which takes into account all critical factors in ERP selection. Keywords: ERP, Information Technologies, Metal Transformation Sector, Business Processes, Reengineering Processes 1. Introduction In our research Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) re- fers to software suites that integrate data and applications, the information flow, and the business processes used in the company, in order to have a fully integrated database, ensuring unique results for all the different queries [1]. These suites have developed complete modules for each standard functional area (finance, operations, purchasing, sales, projects, human resources, etc) in a standard en- terprise, in a standard market, although they sometimes require some customization to be adapted to the specific problems of each enterprise or market. These solutions are reshaping business structures be- cause they promise to solve the challenges posed by portfolios of su pposedly uncoordinated busin ess applica- tions, which are also related to business process innova- tion [2,3]. The aim of these kinds of software develop- ments is to integrate a process-oriented organization and information flow into the enterprise to help management be closer to accurate online information with an intelli- gent analysis of business data. Because the data available is the same for each person working within the company, software suites will also help organizations to manage their own r esources . The implementation of an ERP means removing barri- ers between persons, business processes, information and locations. The benefits associated with ERP systems are both tangible and intangible [4] and can be shown in all dimensions of a business. When ERP is implemented successfully, it can reduce development time of business transactions, facilitate better management and enable e-commerce integration [5]. Researchers have found that ERP implementation has become the largest information system project investment in companies worldwide and this investment is expected to continue for the coming years [6]. Compared to other business solutions, ERP implementation solutions are preferred because of their quicker implementation and development process than in-house developed software. External exclusive development also offers a high quality system, but with its own problems, such as acquisition uncertainty and hidden costs in implementation [7]. As these ideas reveal an important iss ue for enterprises, the fact that three quarters of the ERP projects have been judged unsuccessful by the ERP implementing firms [8] becomes a major problem or that one half of ERP im- plementations are judged to be failures [9] with serious  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 2 consequences, including bankruptcy [2,10]. The reasons could be due to the differences in interests between cus- tomers, who want a unique solution especially ad apted to their enterprise [11], and vendors who prefer generic solutions applicable to a broad market. Before ERP implementation can take place, the or- ganization m ust be reengineered as part of the total pro ject in order to adapt the enterprise to the stronger process- oriented way of work facilitated by the ERP. Several streams of literature have p roposed foundational theories for ERP implementation. One of them focuses on the interaction between ERP and organizations [12], identi- fying ERP implementation with organizational factors such as different types of organizations which require distinct organization fitting processes [13] as well as con- tingent approaches [14]. Another stream focuses on risk factors, identifying key risk factors in each implementa- tion phase [ 10], and a nother in vestigates the k ey factors in process fit and user fit [15]. Finally some authors have outlined cultural aspects [16] and those problems related with ERP integration in SMEs [17]. Generally, we can say that ERP vendor s and enterprises have been aware of these risks that affect the success of software implementation [18], and the important role management has in it. The implementation requires an enormous effort from the firm; it involves organizational, operative and internal changes. However, the organiza- tions that have successfully adopted ERP systems view them as one of the most important innovations that they have carried out, including tangible and intangible im- provements in a variety of different areas. Another chal- lenge is to decide whether it is necessary to change the company processes to fit the ERP or whether it is neces- sary to adapt the ERP to the processes of the company [17]. This issue is critical in cost and time. Failures in ERP implementations have been related to different causes and these must be analyzed before the implementation begins, in each case taking active actions to decrease failure risks. These causes have been docu- mented by critical success fact ors re views [19,20]: • Active management of the changing environment. • Culture of the organizati on. • Adequacy between organizational structure and ERP. • Business process reengineering approach. • Enterprise organizational characteristics. • Communication. • ERP teamwork, composition and leadership. • Monitoring and evaluation of performance. • Project management. • Software development and testing. • Top management support. • Data management. • ERP strategy and implementation methodology. • Training and education. • ERP vendors. With these reviews of the most common problems cited by literature, we must note that not all ERP software has the same scope, neither has it the same process orientation or specialty. Each developer has designed the software with his own view of a standard enterprise in mind, and it is possi ble to fi nd ERP designe d for sm all or medium -size firms oriented to hundreds of movements per year and others for large firms for thousands or hundreds of thou- sand movem ents per year. Therefore, it does not mean that the software cannot work in either size company, but rather that the hardware requirements, the internal proc- esses, and the data have been created for and optimized with these quantities. You can also find different types of ERP vendors and types of licenses. License type should represent a long term commitment to a technology or with a specific vendor. We identified at least three major types of li- censes: Open Source GPL, public licenses that restrict some aspects of the use or distribution, and owner licenses. Being sure that the ERP selected is the most adequate for our company processes and way of work will help im- plementation success. Therefore, we want to focus on the choice of the ERP software to be installed, after carrying out an analysis of the scope, processes, requirements, pricing, etc. The objective of this paper is proposing a relevant de- cision matrix, with the different options available, by following a methodology and organizing a close-to-real pilot test that probes the critical issues. We must also determine what personalization or developments should be carried out to fit the standard ERP to the bus iness, the scope of these developments and to distinguish between software development, reports, adaptations or renaming of fields or labels, and the cost involved. This paper has the following structure. After this in- troduction, we describe the indu stry context: the Spanish metal transformation firms in Section 2. In Sectio n 3, we discuss the ERP evaluation factors and the analytical process involved, and then in Section 4, we apply this methodology to a Spanish metal transformation firm, obtaining a decision matrix to help us to decide the ERP software brand to be installed. Finally, Section 5 con- cludes the main recommendations obtained in the im- plementation of the methodology. 2. The Spanish Metal Transformation Firms ERP philosophy has been designed in an attempt to satisfy all kinds of companies in almost all sectors, using pa- rameters to fit each one. This aspect requires implement-  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 3 tation teams to have a profound knowledge of the sector in order to fit the ERP to the profile of each company. At the European level, the e-Business Watch survey, financed by the European Commission [21], compared the IT situation of the metal transformation sector with all sectors. Figure 1 shows the average diffusion of on-line technologies for the different types of applica- tions. In two applications, the metal transformation sec- tor outperforms the average: the usage of ERP systems (25% in metal products and 20% on the average) and in Internet-based knowledge management solutions (12% in metal products and 10% on the average). In order to discuss the ERP implementation state of the sector, we have found data which shows the percent- age of ERP implementation in firms segmented by size. Figure 2 illustrates the differences in each size. While Source: European Commission, 2003.CRM Figure 1. Average diffusion of information technologies. Source: European Commission, 2003. Figure 2. Usage of online technology for internal processes.  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 4 large companies have an ERP implementation level close to 60%, in medium-sized enterprises it reaches 30% and in small firms around 8%. It can observed that ERP has been largely implemented in large size companies, as the benefits for them in relation to location and importance of real time data access are more obvious. Also, the cost involved in this implementation is a minor factor com- pared to that for small and medium size co mpanies. These results have to be extrapolated to the Spanish environ- ment. To analyze the Spanish market and examine the pro- file of the metal transformation firms, we used the data from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (INE). The total number of Spanish firms is about 47,002, dis- tributed by sub-sectors according to Table 1. Over 50% of the firms belong to the sub-sector of the manufacture of metal products for construction, and 20% are in the sector of metal treatment and coating. The remaining companies are located in other sub-sectors as the manu- facture of articles of cutlery, tools and hardware, the manufacture of metal products, except furniture, and forg- ing and stamping. The distribution of firms by size clearly shows that the main group of the metal transformation sector consists of companies with fewer than 10 employees (83%), while the medium -sized ent erprises c omprise 15%, and o nly 2% are large companies. Therefore, we can say that the typical firm in this sector is a small size company with less than 20 workers. In order to analyze the fit between the various ERPs and the firms, it is necessary to begin by identifying the basic business processes in all activities of a metal trans- formati on company . In gen eral, we can identify five basic activities: purchasing, sales, production, stocks, and finan- cial. The main processes in each activity are the following: • Purchasing: orders, partial or total deliveries, price or quantity variations, consultation of price, stock availability, reserved stock, management of pro- viders. • Sales: quotations, delivery times, sales prices, new products, customer relationship management (CRM), client discounts, special offers. • Productio n: op e rat i ons, product i on or der s . • Stocks: value and cost of stock (average, medium, LIFO (last in, first out)), reserved or availabl e stock, automatic reordering at minimum stock levels, mi- nimum stock warnings, raw materials, stock de- valuation, obsolete stock. • Financial: accounts, fixed assets, taxes formats and communications, bank communication, structure, data imports from past years. Our aim is to identify the flow of information of all processes inside the activities, especially those aspects considered in the normal management of the business, in order to analyze the processes and applications require- ments. To analyze fit between ERP and business proc- esses, attention must be paid to the flow diagram of each process. 3. Evaluation Factors and Analytical Process The scope of an ERP implementation project should vary in each case, but when analyzing processes, all possible interactions between these processes must be contem- plated. Another important consideration is whether the main area processes have been included in the scope. If they have been excluded from the implementation scope, the information we get from the data will not be as valid as we need. All requirements should be structured taking into ac- count two ideas: those processes within the scope that must be integrated in the ERP, and those that consider ERP as external software. These needs must be contem- plated especially if some areas are not to be integrated. This could be the case if in the project, some processes have to work with an older application. In this case, we must be sure that, for example, the scope of implementa- tion takes into account that such processes will be working Table 1. Total number of Spanish firms by princ i pal ac tivity. Sub-sectors No. of firms % Manufacture of metal products for co nstruction 25.450 54,1 Manufacture of tanks, reservoirs and metal containers, radiators 1.306 2,8 Manufacture of steam generators 60 0,1 Forging, stamping and forming of steel, powder metallurgy 1.961 4,2 Metal treatment/coating 9.521 20,3 Manufacture articles of cutlery, tools and hardware 4.413 9,4 Manufacture of metal products, except furniture 4.291 9,1 Total 47.002 100,0 Source: INE, 2008  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 5 in an old platform or application to ensure that integration will be possible and data integrity will be guaranteed. In the first group, we will find that many processes fit in the standard ERP solution, but others will need to be adapted to the ERP, or the ERP reprogrammed to fit company processes. Those are customized processes and the manner in which they are to be adapted is a major evaluation factor. The diagram below identifies a taxonomy of applica- tions in accordance with the scope of the implementation, i.e., which are to be replaced with standard applications of the ERP function and which need to be linked to the ERP (Figure 3). The final task is to identify a list of processes and ap- plications. We must analyze those that can be classified as standard functional requirements to be covered by ERP and are not critical to the election. Then, we can focus on special processes and applications. This tax- onomy should be different for each of the ERP options, which then must be developed by the vendors, and later tested in the pilot. Additionally, we must analyze the applications currently used in the company, what the functions do, and how they i nteract with others, if they do. When a firm makes a decision of implementing an ERP solution, the first question to be asked is: which is the optimum alternative. Normally, some employees should have prior experience with some applications. As the basic objective is to define a decision analysis meth- odology, we propose a five step structure (Figure 4) that has a distinct scope, concerning persons and groups in charge, and resources, and in each of them we will dis- cuss the objective. Step 1 - Determine scope and requirements When a firm has to make a selection between the dif- ferent options of ERP vendors, the firm must be clear about the scope, the approach definition, the requirements and the criteria to evaluate. The objective in this first step is to be sure that the firm understands what is going to be developed and replaced, the implications and the people affected. The first sta ge begins by ide ntifying what i s involved in the implementation scope, the geographical issues such as dispersion of the firm, multi-country and language needs and general functional requirements. After that, a tem- plate of functional requirements and functional areas must be filled out. As stated previously, personnel involvement is a key factor. Figure 3. Process categorization framework.  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 6 Figure 4. Methodology steps. The most intense work load is normally the identifica- tion of p rocesses. First, the global f unction involve d in the implementation scope must be identified. For example, inside purchasing we must consider all the general ac- tivities or sub-processes: orders documentation, mainte- nance providers, delivery times, non-storable products such as transports, etc. For each sub-process, a flow chart has to be designed to identify th e decisions involved, the beginning and end of the process, and the interactions with other processes. At this point in the project, col- laborat ion bet ween ma nagement and wor kers is i mporta nt because a correct identification and definition of proc- esses will help in all steps of the implementation. Finally, a spreadsheet with the all sub-processes is made up, with a flow chart of each sub-process and an explanation how it works. It is important to identify a short ERP vendors list which can be m anaged comfortably. Step 2 - Criteria to be evaluated and RFP In this step, a criteria evaluation must be generated together with a weighted column of those points that should be determinants in the implementation, such as the completion of the initial processes list, technology archi- tecture needed, cost and duration of implementation, maintenance, training. The weights are assigned accord- ing to the firm’s needs, priorities and overall objectives. After this step, a Request for Proposal (RFP) is devel- oped with all criteria that must be evaluated, with an ex- planation of the requirements about compliance or devia- tions, the vendor’s assumptions, implementation success experiences and pricing. Finally, the RFP must be sent to all the ERP vendors included on the list. Step 3 - Compile questions and responses for the RFP The purpose of this step is to answer the ERP vendors’ questions and to be sure that all requirements are under- stood correctly. Afterwards, all ERP vendor responses must be compiled into the RFP and the implementation alternatives, solutions for special processes, and applica- tion requirement s given by the vendors studied. Once this step has been completed, ensuring that spe- cial requirements, alternatives and technical solutions are checked, different demos should be prepared with each vendor to clarify any weak points. After the pilot is pre- pared, and all the information is compiled, the complete offers are ready to be evaluated. Step 4 - Analysis of offers, costs involved and resources needed When the offers are received, all aspects of them must be analyzed: the responses to special requirements, the resources proposed, the range of costs, and the imple- mentation plan, including time, work load and resources involved. After this analysis, any doubts must be identi- fied and the questions resent to the ERP vendor. It is important to remember that errors may occur; therefore, our summary for each ERP vendor must be revised by other colleagues. Step 5 - Select i on and procurement of licens es Once the ERP vendor has bee n selected, the next step is to initiate negotiations to adjust licensing, prices, the maintenance con tract, and actualization issues. This final step must comprise all points of our criteria to ensure a global context implementation and specify the teams involved, the people in charge, the schedule and penalties, if need be. Another critical aspect is the communication of deci- sions to the e nt ire com pany, keeping workers informed of the schedule and scope, especially those affected by strategic tasks inside the company. Resistance to change is always a critical aspect in the implementation period. 4. The Methodology Approach The case study is focused on a medium size company (20 workers) in the Spanish metal transformation sector which was interested in updating its IT capabilities to attain greater control of and better information about business, thus achieving a competitive advantage. The approach represents step one and two of the methodology in a real situation. 4.1. Characteristics of the Firm The company is completely automated having highly robotized productio n lines. It has two business lines. Th e first pro duces standa rd produc ts, with a yearl y deman d for large quantities at a low cost. The second is focused on projects on-demand, with engineering, design, prototype- ing and a short life cycle. The response time must be expeditious, with delivery in 24 hours.  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 7 The customers are mostly local firms. The company needs to be as close to them as possib le since the cost of transportation represents a significant expense and the quantity and price of each order is not high enough to offset this cost. One of the main characteristics of the metal processing sector is that it is very sensitive to price. Because of this, the size of the company is crucial to obtain the best prices from t he su ppl i e rs a nd the best m anufac t uri n g vol u m e. Its main suppliers are major steel producers or processors. This makes it necessary to acquire large volumes of raw materials to achieve a competitive discount advantage. The interaction between these two aspects makes a me- dium size optimal for a company in this sector, as statis- tics show. The organization within the co mpany is a typical fu nc- tional organization, as shown in Figure 5, with each de- partment in charge of its own functions. 4.2. Software and Functionalities The analysis of the business operation in terms of installed applications show s the existence of different applicatio ns in each of the functional areas (purchasing, production, sales, etc), but no information flow between them. This is evident from the map of applications reflected in Figure 6. The firm operates using the following applications: • Purchasing software in MsAccess with local data (internally developed). • Sales software, with local database, also in MsAc- cess and no link between any other programs or database (externally developed). • Operations control and productivity with written weekly reports (no software, done manually). • Stock control (no software, controlled manually). • Material Requirements Planning (MRP) (done manually, aided by spread sheets written by the Technical Department, and stored on a common hard disk ). • Work orders are not automated. Workers must know what is needed in order to manufacture an order. 4.3. Scope and Requirements Our aim is to integrate all applications and departments in two phases. The first will consolidate all applications, except accounts software. When the operation is success- ful, the second phase will include accounts. Once this scheme has been approved, all the processes must be analyzed and adapted to the functionalities and characteristics of the ERP software, with the help of the people in charge of each process. Everyone in the or- ganization must be involved to ensure that all types of eventualities have been included. The new flow chart of the company is reflected in Figure 7 and represents how the processes will be developed after this analysis. The ERP software design includes finances, sales and distribution, CRM, e-commerce, purchasing (MRP and MRPII), stoc k ma nagem ent and operat io ns supp ort insi de a unique system, all integrated. After a first contact with different vendors and software, we noticed several solu- tions with different license approaches: • Property license such as Microsoft Dynamics Nav, SAP Business One and JD Edwards. • Open Source (GPL license), such as Abanq and OpenErp. • Public licenses that restrict some aspects of the use or distribution, such as Open Bravo and Compiere. Following the analysis, we identified which processes fit with a standard flow (supported) and which had to be customized initially (Table 2). For example, the pro- cesses relating to Calculation of Estimated Cost of existing products, or Reserve Stock, meet the standard require- ments offered by a commercial ERP and required no customization. On the contrary, the processes related to Figure 5. General chart of the firm.  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 8 Figure 6. Applications map. Figure 7. New general flow chart.  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 9 Table 2. Processes and application table. Processes ERP Supported Customization required Proposal Management (Sales) Proposal releases management X X Estimated time of delivery X X Existing products (estimated cost calculation) X Non existing products (proposal creation and valuation) X X Purchasing Split components X Reserve stock X Multiple request X Partial deliveries X Differences between orders and deliveries X X Claims and returns X Suppliers management X Price update X Order Tracking X Technical definitions Components X Drawing and codes X Work Orders Workers management (cost and times) X X Split order management X Work order sh eet info X X Machinery preparation costs X Machinery load/work surveillance X Work load surveillance: X X Desviation from estimated time and cost X X Sales Track orders X Customer discount management X Customer credit risk X Customer orders update management X X Delivery time surveillance X X Drawing and Codes, and Price Updates needed complete customization because they were not standard. That is also the case of Estimated Time of Delivery, Differences between Orders and Deliveries, Deviation from estimated Time and Cost, and others. In order to keep the case study from becoming too lengthy, we will focus on only three critical processes: Purchasing, Proposal Management and Work Orders. A  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 10 greater level of detail is req uired to custo mize the active- ties that must be developed for these processes. Each process had to be analyzed at length to ensure its fit with the standard, and if it did not, it became a new development project within the implementation. Because each external link is critical and re presents one of the most risky aspects, we must be sure to close all sources of the information flow so that the ERP doesn’t lose control every time the flow gets out of the system (Figures 8, 9 and 10). Figure 8. Purchasing flow chart. Figure 9. Proposal management flow chart.  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 11 Figure 10. Work orders flow chart. From the analysis of all features included in the pro- cesses stands out a set of applications that needs to be studied in detail for customizing according to their own requirements. Process for the Management of Proposals • The management of proposals must be flexible and take i nto acco unt all versi ons a nd cha nges di scussed with the client before the order is finalized. • Regarding estimated delivery time, the ERP must be able to pr ovide inform ation a bout the work load an d machinery that will help to analyze future delivery times. Optionally, the system could give an esti- mated time. • Creation and val uati on of non -exist ing p rod uc ts i s a major development because it collects the special requirements of future developments or never pro- duced products that must be budgeted. The most efficient way to budget non-existing products is to use the time frame estim ated by the person in charge of proposal, with advice from the technical de- partment if necessary, and the costs of the machin- ery and workers estimated by the ERP. If the pro- posal is approved by the client, the order must be redesigned according to this initial information. Purchasing Process • The differences between ordered and delivered quantities must be managed by the system. It must permit changes and recalculate all costs. Also, any returns must be included. • To ensure that price given to the clients fits with the internal costs, the system should handle this infor- mation and analyze deviations. When the prices of spare parts or raw materials are updated, the sys- tem must be able to recalculate the cost elements involved. • Work Orders Proces s • The most important aspect in this process is to in- tegrate the management of labour so that this in- formation can be used as a reference for the rele- vant indicators such as productivity, absenteeism, etc., and to narrow the initial time estimation. It must include a control of deviations from estimated time and the surveillance of workers. • This application includes information which is needed in the report used in the work order. All the other processes (Sal es and Technical definit ions)  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 12 required for an efficient ERP design also require a set of applications that need to be customized. In the sales processes, the major problem reported by workers is the constant updating of the order by the customers, and its implications. This suggests the need for constant real-time information between client sales and manufacturing on the state of the order. The sales department must also ensure that tracking the order is always possible. Finally, the integration of the system with the technical department requires a specific design of drawings and code applications. 4.4. Concept Evaluation. Decision Matrix and Evaluation Criteria Once all processes have been analyzed in accordance with the requirements identified in the flow of information, it will be possible to decide which provider and alternativ e of ERP will be best. All requirements should be listed on a spreadsheet with the information collected from the ERP vendors, the demonstrations, and our general im- pressions. The Concept comparison and Evaluation proposed by Pugh [22] is a well known and referred method for con- cept selection. It is based in the selection of the evaluation criteria for the concepts. The spreadsheet with the dif- ferent main aspects must be organized to collect the im- pressions from employees in each functional department, on usability and user friendliness, in addition to techn ical IT aspects and the costs involved. The decision-m atrix is a quantitative tech nique used to rank the multi-dimensional options of an option set and is a form of prioritization matrix. The basic decision matrix consists of establishing a set of weighted criteria upon which the potential options can be analyzed, scored and balanced to obtain a score ranking. These scores are organized in order to rate each concept, the higher the so cre the higher its compatibility. It is a useful iterative method for the comparison of alternative concepts. The advantage of this approach to decision-making is that subjective opinions about alternatives can be made more objective. Another advantag e of this method is that sensitivity studies can be performed. The major advantage of this method is that it facilitates analytical and synthetic thinking and that new concepts can be generated as a consequence. In reference to the firm being analyzed, six principal aspects were identified: standard compliance, develop- ments compliance for software adaptations, solutions offered by the different departments of the firm for criti- cal issues reports, skills and confident in the demonstra- tion, technical requirements and fit with the IT depart- ment, and finally cost involved. The main and secondary weights were established by the management staff, ac- cording to the IT department and consultant’s analysis (Table 3). 4.5. Analytical Hierarchy Process Method (AHP) An alternative comprehensive method has been proposed by Saaty [23 ]. It de termines the priority of a set of alter- natives and the relative i mportance of attributes in a mul- tiple criteri a decision-m aking pr oblem. It has been used in various applicati ons such as inform ation syst em select ion, as well as ERP selection [24]. The basic approach of this method relies on bu ilding a hierarchy of all objectives derived from the strategic analysis in order to distinguish fundamental-objectives from means-objectives. The former being those that de- cision makers really want to accomplish while the latter are those which help the fulfillment of other objectives. Consequently, fundamental-objectives are organized into a hierarchy which will help the decision makers in order to identify the relevance of ERP attributes. Thus, the priority of alternatives can be obtained by aggregating the weights over the hierarchy. This can speed up the development of a consensus in relation to the ERP sys- tem and vendors alternatives [24]. The Figure 11 illus- trates this selection alternativ e. In relation to fundamental-objectives, it must be taken into account the limitations of decision factors and the changing business environment. Means-objectives are usually organized into networks relating them (i.e. flexi- bility and ease of integration may be related with common program mi ng langua ge, pl at form inde pe nde n ce or syst em maturity). The set of ERP candidates and vendors can be shortened by examining means-objectives and also de- velop detailed attribute specifications to assess the ERP systems. Alternatives for attributes and inter-attribute relative relevance can be converted into numerical scales in order to weight them. 5. Conclusions For a firm to gain competitive advantage, managers need to outline a set of objectives. Normally these object- tives reflect both the business drivers and the market. Conversely, firms are facing significant challenges in order to become suppliers of larger customers due to the excessive costs associated with accessi ng a vast market of potential customers. For these reasons, it is essential for companies to adopt an ERP system to maintain control of their operations and to compete globally. An ERP im- plementat ion is expe nsive and risky f or all busi nesses, but it is even more challenging for small businesses, which have particular characteristics.  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 13 Table 3. Case study of a decision matrix. Vendor 1 Vendor 2 Vendor 3 Weight % Mark (1-10) Mark (1-10) Mark (1-10) Standard functionality requirements 20% Standard ERP Compliance 2 0% Sales compliance 10% Purchasing compliance 10% Proposal compliance 10% Stock management compliance 10% Work order compliance 20% Management compliance 20% Special processes requirement 10% Sales compliance 15% Purchasing compliance 15% Proposal compliance 15% Stock management compliance 15% Work order compliance 25% Management compliance 15% Special issues reported (solution provided) 20% Proposal release management 10% Delivery time info 10% Non existing produc ts proposal management 20% Differences between orders and deliveries 10% Estimated price calculation and controls involved 10% Workers management 20% Updating of clients orders 10% Client order tracking 10% Demonstration 10% Knowledge of the product 25% Demo customiz a tion to company needs 35% Usability 40% Technical requirements 10% Infraestructure 20% Tools 15% Database 15% Integration 20% Reporting 10% Maintainance difficulty 20% Pricing 20% Hardware cost 15% Software cost 15% Maintenance cost 20% Support cost 20% License cost 15% Training cost 15%  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 14 Figure 11. ERP selection system based on AHP. Despite the great potential and popularity, the adoption and implementation of an ERP is compromised by re- markable failures. While many studies highlight the ex- istence of different factors, we argue that the integrated nature of the ERP, which generally requires an organiza- tion to adopt standardized business processes reflected in the design of the software, constitutes a key factor that can contribute to reducing th ese failures. But the integra- tion and standardization imposed by most ERP software may not be suitable for all types of firms. Thus, the fit between the characteristics of the adopting organization, and the standardized business process designs embedded  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 15 in the adopted ERP, affects the likelihood of i mplement- tation success or failure. Currently, there are a wide variety of ERP solutions and vendors, and the election of one that fits as closely as possible with our company’s needs should be a major issue and a critical decision. In this context, we must analyze our objectives and the processes involved, and motivate workers and utilize their knowledge, so as to provide as much information as possible regarding all the aspects affected by this change. The methodology de- veloped represents a managerial strategic approach to selecting ERP software for a firm intending to realize products, an d b ri n g t hem to the m arket . It s contribution i s that decisions on ERP adoption and imple mentatio n in an enterprise can be made based on multi-criteria factors that directly affect the processes. One of the most critical steps of the methodology proposes to identify which processes fit with a standard flow and which must be customized. These latter processes require a higher level of detail for customization in the activ ities that have to be developed. We conclude that this methodology is systematic, re- liable, easy to apply, and accessible. It offers a valuable means of capturing knowledge in a firm since different people from various departments come together to col- laborate on strategic issue s concerning t he business model of the company. Finally, the application of the method- ology also offers a decision support instrument, and the final decision can be made by the decision-makers after the consideration of other economic factors such as budget constraints. 6. References [1] O. Velcu, “Strategic Alignment of ERP Implementation Stages: An Empirical Investigation,” Information and Management, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2010, pp. 158-166. doi:10.1016/j.im.2010.01.005 [2] T. H. Davenport, “Putting the Enterprise into the Enter- prise System,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 76, No. 4, 1998, pp. 121-131. [3] T. H. Davenport, “Putting the Enterprise into the Enter- prise System,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 76, No. 4, 1998, pp. 121-131. [4] K. E. Murphy and S. J. Simon, “Intangible Benefits Valuation in ERP Projects,” Information Systems Journal, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2002, pp. 301-320. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2575.2002.00131.x [5] T. H. Davenport, “Mission Critical: Realizing the Promise of Enterprise Systems,” Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 2000. [6] T. F. Gattiker and D. L. Goodhue, “What Happens after ERP Implementation: Understanding the Impact of Inter- Dependence and Differentiation on Plant-Level Out- comes,” MIS Qu arterly, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2005, pp. 559-585. [7] K. K. Hong and Y. G. Kim, “The Critical Success Factors for ERP Implementation: An Organizational Fit Perspec- tive,” Information and Management, Vol. 40, No . 1, 2002, pp. 25-40. doi:10.1016/S0378-7206(01)00134-3 [8] T. L. Griffith, R. F. Zammuto and L. Aiman-Smith, “Why New Technologies Fail?” Industrial Management, Vol. 41, No. 3, 1999, pp. 29-34. [9] A. W. Scheer and F. Habermann, “Making ERP a Suc- cess,” Communications of the ACM, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2000, pp. 57-61. doi:10.1145/332051.332073 [10] M. L. Markus, S. Axline, D.Petrie and C. Tanis, “Learning from Adopters’ Experiences with ERP: Problems Encoun- tered and Success Achieved,” Journal of Information Technology, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2000, pp. 245-265. doi:10.1080/02683960010008944 [11] J. Swan, S. Newell and M. Robertson, “The Illusion of ‘Best Practice’ in Information Systems for Operations Management,” European Journal of Information Systems, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1999, pp. 284-293. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000336 [12] T. F. Gattiker and D. L. Goodhue, “Understanding the Local-Level Costs and Benefits o f ERP through O rganiza- tional Information Processing Theory,” Information and Management, Vol. 41, 2004, pp. 431-443. doi:10.1016/S0378-7206(03)00082-X [13] E. T. G. Wang, C. Chia-Lin, J. J. Jiang and G. Klein, “Improving Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Fit to Organizational Process Through Knowledge Transfer,” International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 27, 2008, pp. 200-212. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2007.02.002 [14] N. A. Morton and Q. Hu, “Implications of the Fit be- tween Organizational Structure and ERP: A Structural Contin-Gency Theory Perspective,” International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 28, No. 5, 2008, pp. 391-402. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2008.01.008 [15] C. Berchet and G. Habchi, “The Implementation and Deployment of a n ERP System: An Industrial Case Study . Current Trends in ERP Implementations and Utilisation,” Computers in Industry, Vol. 56, No. 6, 2005, pp. 588-605. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2005.02.009 [16] D. Avison and J. Malaurent, “Impact of Cultural Differ- ences: A Case Study of ERP Introduction in China,” In- ternational Journal of Information Management, Vol. 27, 2007, pp. 368-374. [17] R. Malhotra and C. Temponi, “Critical Decisions for ERP Integration: Small Business Issues,” International Jour- nal of Information Management, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2010, pp. 28-37. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2009.03.001 [18] M. O. Barros, C. M. L. Werner and G. H. Travassos, “Supporting Risks in Software Project Management,” The Journal of Systems & Software, Vol. 70, No. 1-2, 2004, pp. 21-35. doi:10.1016/S0164-1212(02)00155-3 [19] D. Gefen, “What Makes an ERP Implementation Rela- tionship Worthwhile: Linking Trust Mech anisms and ERP Usefulness,” Jou rnal of Management Information Sy stems, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2004, pp. 263-288. [20] E. W. T. Ngai, C. C. H. Law and F. K. T. Wat, “Examin-  A. HIDALGO ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IIM 16 ing the Critical Success Factors in the Adoption of Enter- prise Resource Planning,” Computers in Industry, Vol. 59, 2008, pp. 548-564. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2007.12.001 [21] European Commission, “ICT & E-Business in the Metal Products Industry,” The European e-Business Market Watch, Sector Report No. 9, Brussels, 2003. [22] S. Pugh, “Concept Selection: A Method that Works,” Proceedings of International Conference on Engineering Design, Heurista, Zürich, 1981, pp. 497-506. [23] T. L. Saaty, “The Analytic Hierarchy Process,” McGraw- Hill, New York, 1980. [24] C. C. Wei, C. F. Chien and M. J. Wang, “An AHP-Based Approach to ERP System Selection,” International Jour- nal of Production Economics, Vol. 96, 2005, pp. 47-62. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2004.03.004 |