S. BANDYOPADHYAY, B. C. MCCANNON 43

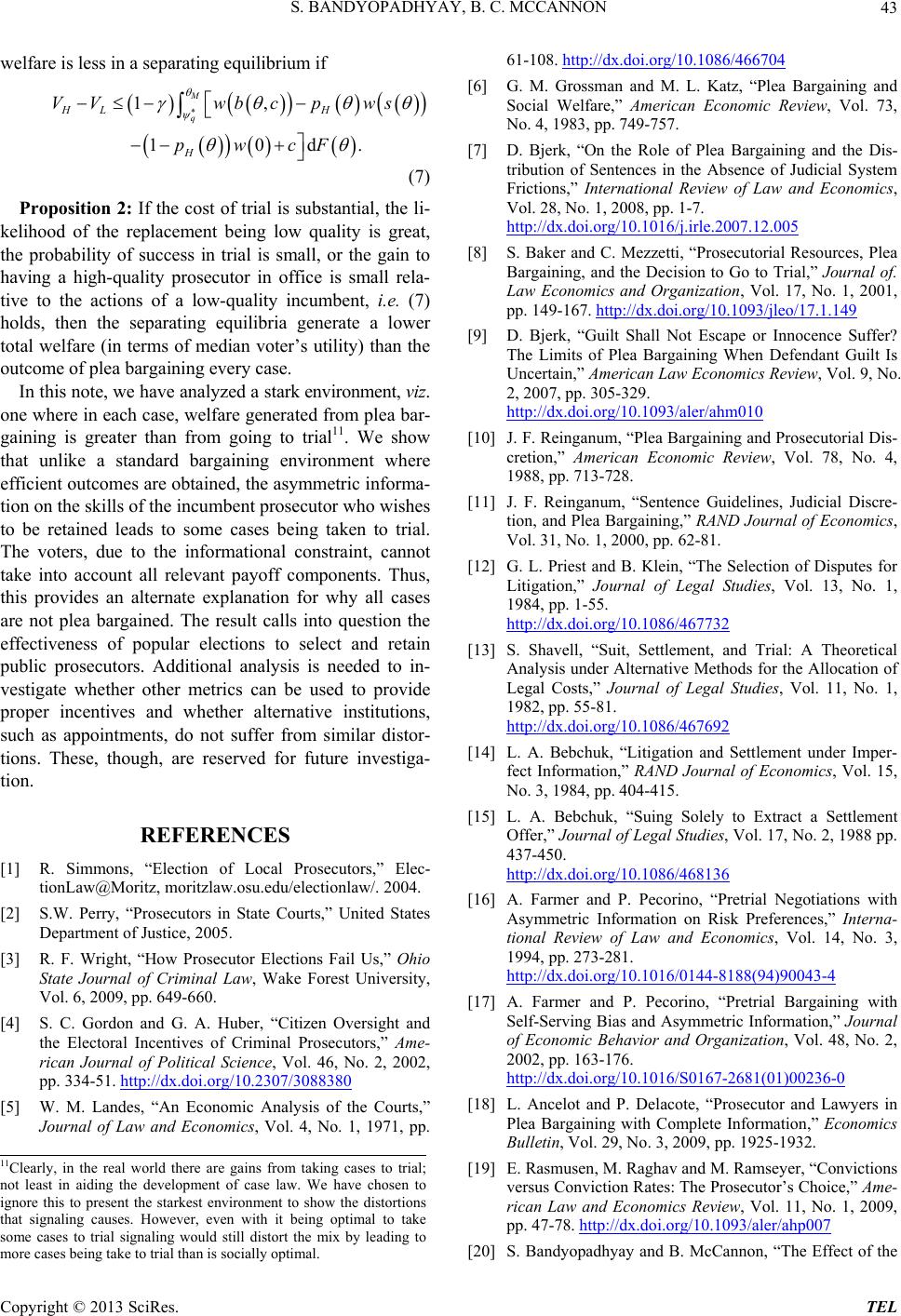

welfare is less in a separating equilibrium if

1,

10d.

M

q

HL H

H

VVwbc pws

pwcF

(7)

Proposition 2: If the cost of trial is substantial, the li-

kelihood of the replacement being low quality is great,

the probability of success in trial is small, or the gain to

having a high-quality prosecutor in office is small rela-

tive to the actions of a low-quality incumbent, i.e. (7)

holds, then the separating equilibria generate a lower

total welfare (in terms of median voter’s utility) than the

outcome of plea bargaining every case.

In this note, we have analyzed a stark environment, viz.

one where in each case, welfare generated from plea bar-

gaining is greater than from going to trial11. We show

that unlike a standard bargaining environment where

efficient outcomes are obtained, the asymmetric informa-

tion on the skills of the incumbent prosecutor who wishes

to be retained leads to some cases being taken to trial.

The voters, due to the informational constraint, cannot

take into account all relevant payoff components. Thus,

this provides an alternate explanation for why all cases

are not plea bargained. The result calls into question the

effectiveness of popular elections to select and retain

public prosecutors. Additional analysis is needed to in-

vestigate whether other metrics can be used to provide

proper incentives and whether alternative institutions,

such as appointments, do not suffer from similar distor-

tions. These, though, are reserved for future investiga-

tion.

REFERENCES

[1] R. Simmons, “Election of Local Prosecutors,” Elec-

tionLaw@Moritz, moritzlaw.osu.edu/electionlaw/. 2004.

[2] S.W. Perry, “Prosecutors in State Courts,” United States

Department of Justice, 2005.

[3] R. F. Wright, “How Prosecutor Elections Fail Us,” Ohio

State Journal of Criminal Law, Wake Forest University,

Vol. 6, 2009, pp. 649-660.

[4] S. C. Gordon and G. A. Huber, “Citizen Oversight and

the Electoral Incentives of Criminal Prosecutors,” Ame-

rican Journal of Political Science, Vol. 46, No. 2, 2002,

pp. 334-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3088380

[5] W. M. Landes, “An Economic Analysis of the Courts,”

Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1971, pp.

61-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/466704

[6] G. M. Grossman and M. L. Katz, “Plea Bargaining and

Social Welfare,” American Economic Review, Vol. 73,

No. 4, 1983, pp. 749-757.

[7] D. Bjerk, “On the Role of Plea Bargaining and the Dis-

tribution of Sentences in the Absence of Judicial System

Frictions,” International Review of Law and Economics,

Vol. 28, No. 1, 2008, pp. 1-7.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2007.12.005

[8] S. Baker and C. Mezzetti, “Prosecutorial Resources, Plea

Bargaining, and the Decision to Go to Trial,” Journal of.

Law Economics and Organization, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2001,

pp. 149-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jleo/17.1.149

[9] D. Bjerk, “Guilt Shall Not Escape or Innocence Suffer?

The Limits of Plea Bargaining When Defendant Guilt Is

Uncertain,” American Law Economics Review, Vol. 9, No.

2, 2007, pp. 305-329.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aler/ahm010

[10] J. F. Reinganum, “Plea Bargaining and Prosecutorial Dis-

cretion,” American Economic Review, Vol. 78, No. 4,

1988, pp. 713-728.

[11] J. F. Reinganum, “Sentence Guidelines, Judicial Discre-

tion, and Plea Bargaining,” RAND Journal of Economics,

Vol. 31, No. 1, 2000, pp. 62-81.

[12] G. L. Priest and B. Klein, “The Selection of Disputes for

Litigation,” Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 13, No. 1,

1984, pp. 1-55.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/467732

[13] S. Shavell, “Suit, Settlement, and Trial: A Theoretical

Analysis under Alternative Methods for the Allocation of

Legal Costs,” Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1,

1982, pp. 55-81.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/467692

[14] L. A. Bebchuk, “Litigation and Settlement under Imper-

fect Information,” RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 15,

No. 3, 1984, pp. 404-415.

[15] L. A. Bebchuk, “Suing Solely to Extract a Settlement

Offer,” Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 17, No. 2, 1988 pp.

437-450.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/468136

[16] A. Farmer and P. Pecorino, “Pretrial Negotiations with

Asymmetric Information on Risk Preferences,” Interna-

tional Review of Law and Economics, Vol. 14, No. 3,

1994, pp. 273-281.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0144-8188(94)90043-4

[17] A. Farmer and P. Pecorino, “Pretrial Bargaining with

Self-Serving Bias and Asymmetric Information,” Journal

of Economic Behavior and Organization, Vol. 48, No. 2,

2002, pp. 163-176.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(01)00236-0

[18] L. Ancelot and P. Delacote, “Prosecutor and Lawyers in

Plea Bargaining with Complete Information,” Economics

Bulletin, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2009, pp. 1925-1932.

11Clearly, in the real world there are gains from taking cases to trial;

not least in aiding the development of case law. We have chosen to

ignore this to present the starkest environment to show the distortions

that signaling causes. However, even with it being optimal to take

some cases to trial signaling would still distort the mix by leading to

more cases being take to trial than is socially optimal.

[19] E. Rasmusen, M. Raghav and M. Ramseyer, “Convictions

versus Conviction Rates: The Prosecutor’s Choice,” Ame-

rican Law and Economics Review, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2009,

pp. 47-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aler/ahp007

[20] S. Bandyopadhyay and B. McCannon, “The Effect of the

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL