Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

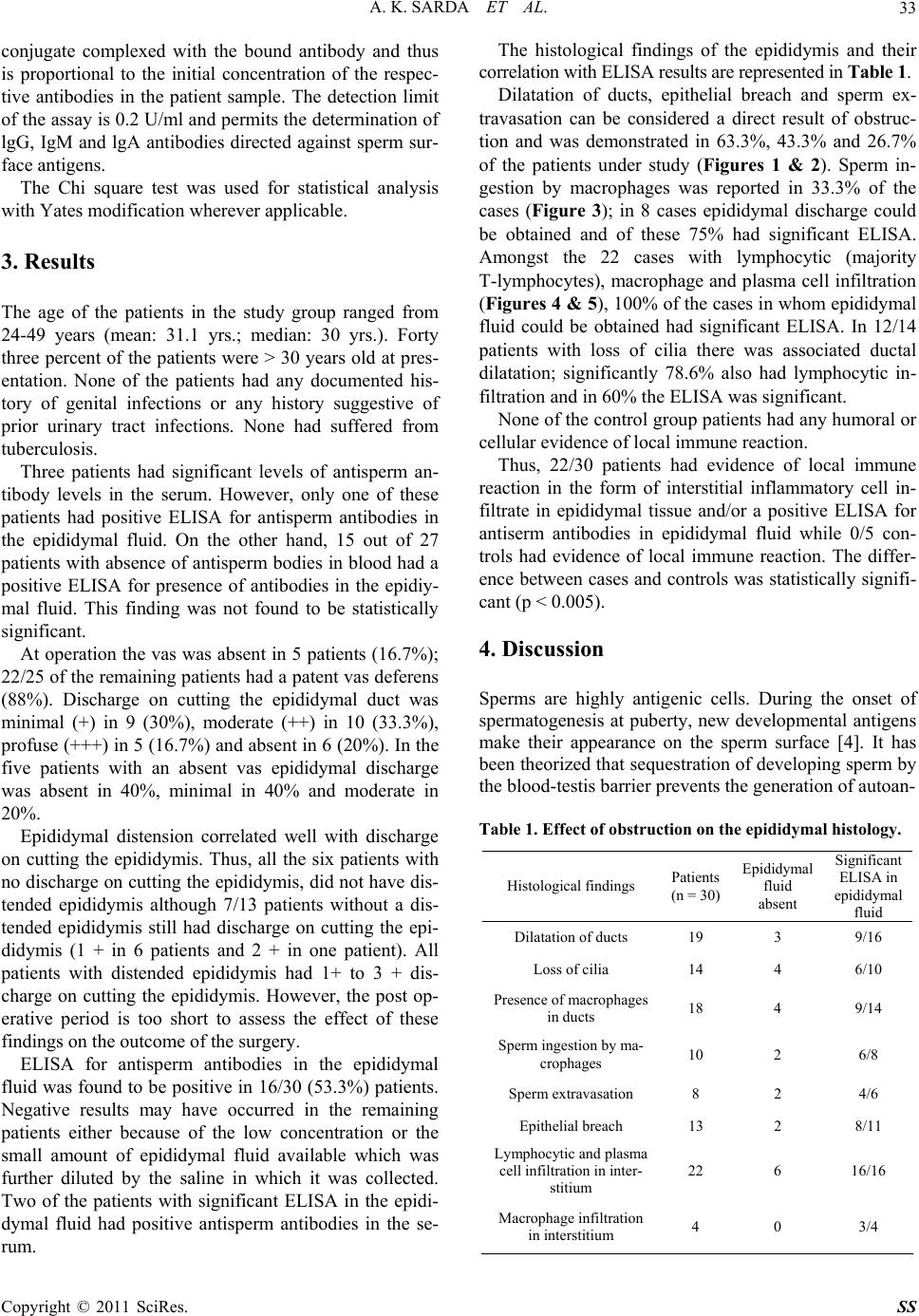

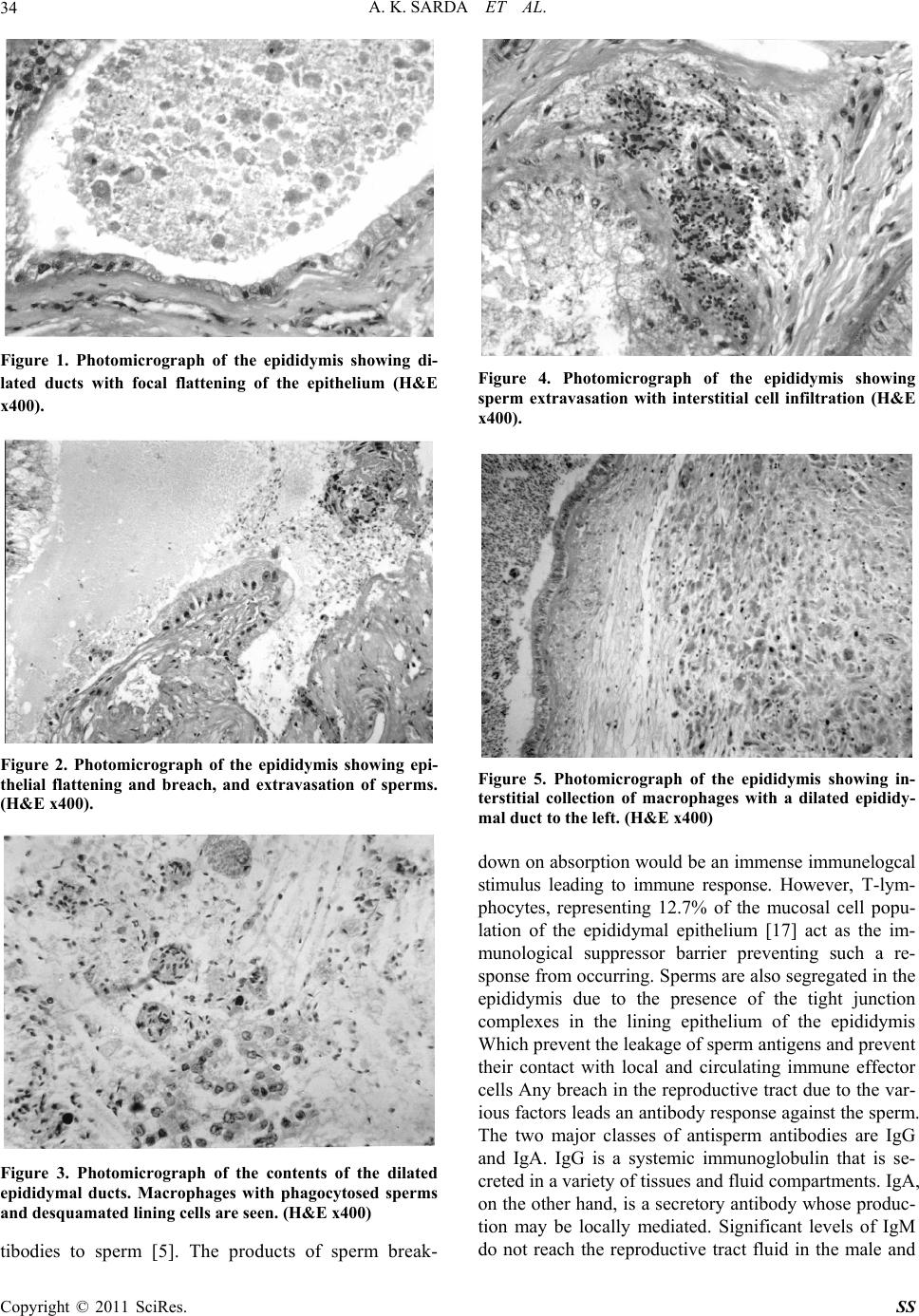

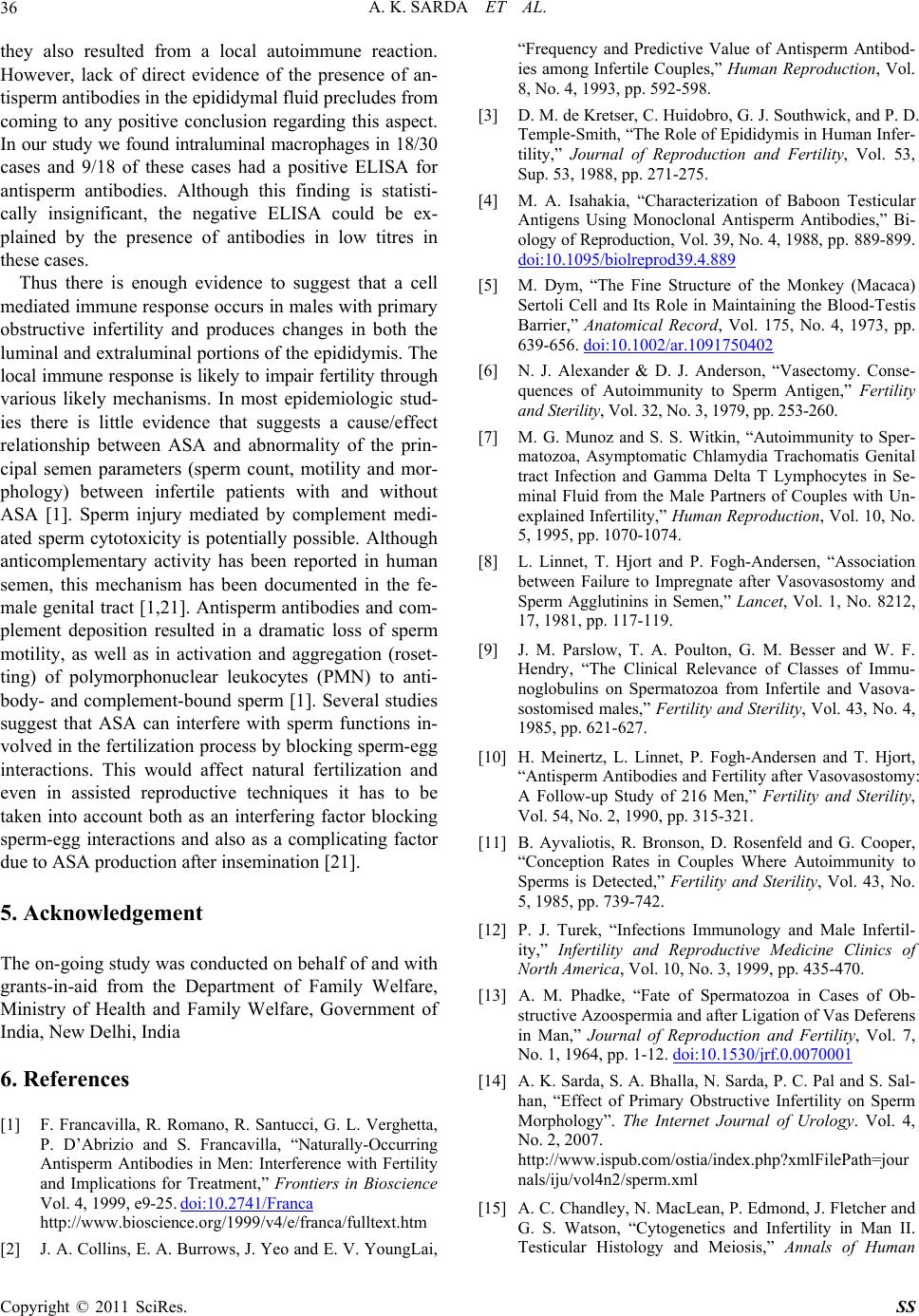

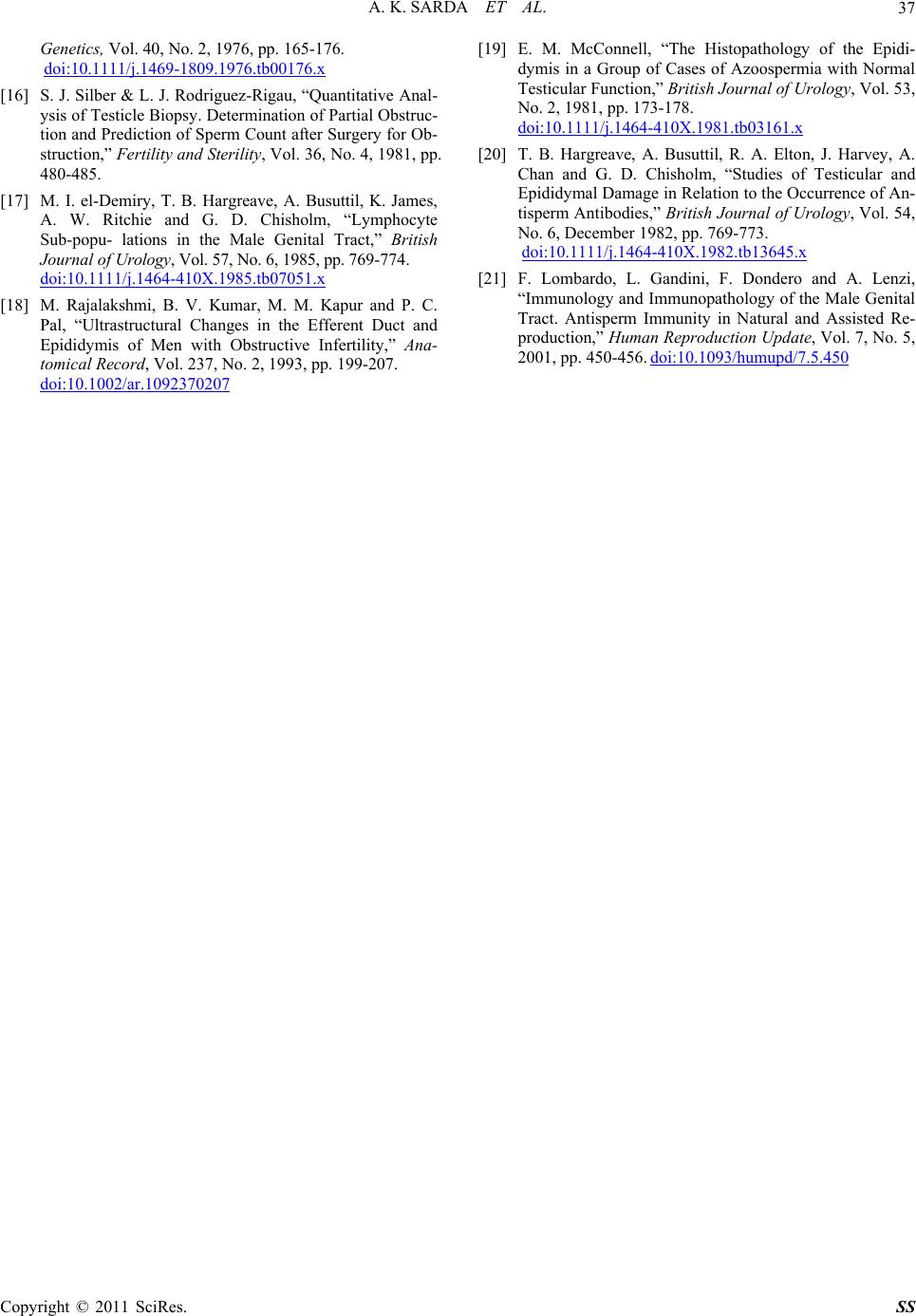

Surgical Science, 2011, 2, 31-37 doi:10.4236/ss.2011.21008 Published Online January 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ss) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS Local Cell Mediated Immune Reaction in Primary Obstructive Male Infertility Anil Kumar Sarda, Shweta Aggarwal Bhalla, Durgatosh Pandey, Shyama Jain* Departments of Surgery & Pathology*, Maulana Aza d Medical College & associated L. N. Hospital, New Delhi, INDIA. E-mail: aksarda@rediffmail.com Received August 9, 2010; revised October 15, 2010; accepted January 13, 2011 Abstract Increased intra-epididymal pressure due to obstruction causes a breach in the epididymal lining exposing the highly antigenic sperms to the interstitium. When the exposure is small and intermittent, it is likely to induce a local humoral response which may affect sperm maturation and also react with the epididymal epithelium producing irreversible histological changes. The present study on 30 patients of primary obstructive infertil- ity found direct and indirect evidence of the production of antisperm antibodies locally. ELISA for antisperm antibodies was positive in the epididymal fluid in 16/30 (53%) of the patients. Indirect evidence of the role of local antigen-antibody reaction in the epididymis is apparent in 22/30 (73%) patients who had a lymphocytic infiltrate. The local presence of antisperm antibodies in the epididymal fluid correlated well with the pres- ence of lymphocytic infiltration in the interstitium (p < 0.05). In our study 16/30 patients had a positive ELISA for antisperm antibody and all these patients had interstitial lymphocytic infiltration. In addition eight patients with a negative ELISA also showed interstitial lymphocytic infiltration. Thus 22/30 (73%) patients had an evidence of a local immune reaction directly in the form of a positive ELISA for antisperm antibodies in the epididymal fluid and / or indirect evidence in the form of lymphocytic infiltrate in the interstitium. None of the five controls had either a positive ELISA or lymphocytic infiltrate, this difference was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.005). Keywords: Male Infertility, Autoimmunity, Testis, Epididymis, Histology 1. Introduction The reported prevalence of antisperm antibodies (ASA) varies depending on the modality of the immunological screening. Circulating ASA detected with indirect tests ranges from 8.1% to 30.3% in unselected men with in- fertile marriages; at low titres they were also reported in 2.4% to 10% of fertile men [1]. When stricter criteria were used, the prevalence of ASA in men with infertile marriages was 4.7% to 7.5%. Obstruction leading to the production of antisperm antibodies is evidenced by the fact that 34% – 74 % men develop antisperm antibodies post vasectomy [2]. Though the association of epididy- mal occlusion with antisperm antibodies has not been widely studied, a recent report shows that antisperm an- tibodies are present in the serum of men with epididymal occlusion, whether of infective or congenital origin. The incidence is higher when occlusion is more distal [3]. During the onset of spermatogenesis at puberty, new developmental antigens make their appearance on the sperm surface [4]. Since immune tolerance for self-antigens is expressed neonatally, these newly ap- pearing sperm antigens may be immunogenic. It has been theorized that sequestration of developing sperm by the blood testis barrier prevents the generation of autoanti- bodies to sperm [5]. Normally the epididymal epith elium is well adapted to prevent transwall migration of immu- nologically active material. However, in case of obstruc- tive azoospermia, leakage of spermatozoal degradation fragments occurring proximal to th e site of obstruction in the epididymis [6], or trauma to the testis or a breach of the male reproductive tract allows the sperm antigens to escape into the microcapillaries surrounding the repro- ductive tract and then into the systemic circulation and stimulate a humoral immune response. Genital tract in- fections can also induce antisperm antibodies production  A. K. SARDA ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS 32 due to a breach in blood testis barrier due to inflamma- tion or by production of antibodies against the infective agents like Chlamydia which cross react with spermato- zoa [7]. Approximately 34% to 74% prevalence of ASA is reported in men who have undergone a vasectomy, with their persistence in 38% to 60% following success- ful vasovasostomy [1] which may have a negative impact on fertility. The deleterious effect of antisperm antibodies on fer- tility has been well documented [8-11]. Also, the epidi- dymis is considered to be the most likely source of anti- body secretion. It is populated with lymphocytes and macrophages [12]. The secretion of antibodies by the epididymis may be increased in cases of obstructive in- fertility as suggested by the presence of inflammatory cells including plasma cells, in the interstitium of these cases [13]. Increased intra-epididymal pressure due to obstruction has been reported to cause a breach in the epididymal lining exposing the highly antigenic sperms to the inter- stitium. When the exposure is large antisperm antibodies are produced in the serum. However, small, intermittent exposure to sperms is likely to induce a local humoral response which may not manifest itself in the serum. These antisperm antibodies secreted locally in the epidi- dymis would act on the already disintegrating spermato- zoa and further impair their function and maturation. It is possible that the antigen-antibody complexes also react with the epididymal epithelium producing irreversible histological changes, which impair the function of the epidididymis, in turn impairing sperm maturation. Thus, the persistence of infertility in patients with obstruction to the egress of sperms even after a patent anastomosis could be due to the abnormal morphology or impaired function of the spermatozoa caused by locally secreted antisperm antibodies. Further, with progress in assisted reproductive techniques, the role of ASA in male infer- tility is becoming better defined. We believe that repeated exposure to small amounts of extravasated sperms in the epid idymal interstitium would be sufficient to produce antisperm antibodies locally which could then initiate a local cell mediated immune reaction with its attendant effects on the epididymis and sperms. The role of local immune reaction in obstru ctive infertility has no t been widely studied . The present study focuses on the role of local cell mediated immune re- sponse in primary obstructive male in fertility. 2. Materials and Methods Thirty patients of primary obstructive infertility with azoospermia, presence of fructose in the semen and nor- mal spermatogenesis were included. Details of material and methods have been described in an earlier report [14]. Six patients with bilateral absence of vas deferens were also included in our study because of our policy to con- firm absence of vas by scrotal exploration and in these patients to an artificial spermatocele in these patients to give them a chance for utilizing one of the cheaper me- thods of assisted reproduction, i.e. intra-uterine insemi- nation of aspirated sperms. The remaining patients were subjected to a single layer side-to-side vasoepididymostomy if the epididymal ducts were dilated, microscopic examination of the epidi- dymal fluid revealed the presence of sperms and the dis- tal vas was patent [14]. The epididymis was incised and tissue taken for histo logical examination. The epididymal fluid was taken with a micro-pipette was diluted with normal saline for determination of anti-sperm antibodies in the supernatant fluid with the precipitated sperms be- ing used to study sperm morphology and other studies. The procedure was completed after taking a testicular biopsy which included part of tunica albuginea. Five controls were also studied. They were of proven fertility. Testicular biopsy and epididymal wedge biopsy were taken at the time of autopsy or from patients who underwent orchiectomy for any reason except for tes- ticular torsion or testicular malignanc y. Epididymal fluid was also aspirated for cytology for sperm morphology and also for analysis of antisperm antibodies. Grade of spermatogenesis in the testicular tissue was done according to the accepted criteria [15]. The inter- stitium was specially screened for presence of lympho- cytes, plasma cells, histiocytes. Mature spermatids will be identified as oval cells with dark densely stained chro- matin. The number of mature spermatids will be totaled in twenty tubules and the total be divided by twenty to give an estimate of number of mature spermatids per tubule for quantitation of mature spermatids per tubule [16]. The histologic features were recorded on a pre-deter- mined performa as described earlier [14]. ELISA technique was used to detect antisperm anti- bodies by utilizing a commercially available kit. The kit is an indirect noncompetitive enzyme immunoassay for the semiquantitative and qualitative determination of antibodies directed to spermatozoa surface antigen. The wells of a microtiter plate are coated with spermatozoa surface antigen. Sperm specific antibodies present in the patient sample bind to the antigen. In a second step the antigen-antibody co mplex reacts with an enzyme labeled second antibody (Enzyme Conjugate) which leads to the formation of an enzyme labeled antigen-antibody sand- wich complex. The enzyme label converts added sub- strate to form a colored solution. The rate of color for- mation from the chromogen is a function of enzyme  A. K. SARDA ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS 33 conjugate complexed with the bound antibody and thus is proportional to the initial concentration of the respec- tive antibodies in the patient sample. The detection limit of the assay is 0.2 U/ml and permits the determination of lgG, IgM and lgA antibodies directed against sperm sur- face antigens. The Chi square test was used for statistical analysis with Yates modification wherever applicable. 3. Results The age of the patients in the study group ranged from 24-49 years (mean: 31.1 yrs.; median: 30 yrs.). Forty three percent of the patients were > 30 years old at pres- entation. None of the patients had any documented his- tory of genital infections or any history suggestive of prior urinary tract infections. None had suffered from tuberculosis. Three patients had significant levels of antisperm an- tibody levels in the serum. However, only one of these patients had positive ELISA for antisperm antibodies in the epididymal fluid. On the other hand, 15 out of 27 patients with absence of antisperm bodies in blood had a positive ELISA for presence of antibodies in the epidiy- mal fluid. This finding was not found to be statistically significant. At operation the vas was absent in 5 pa tients (16.7%); 22/25 of the remaining patients had a patent vas deferens (88%). Discharge on cutting the epididymal duct was minimal (+) in 9 (30%), moderate (++) in 10 (33.3%), profuse (+++) in 5 (16.7%) and absent in 6 (20%). In the five patients with an absent vas epididymal discharge was absent in 40%, minimal in 40% and moderate in 20%. Epididymal distension correlated well with discharge on cutting the epididymis. Thus, all the six patients with no discharge on cutting the epididymis, did no t have dis- tended epididymis although 7/13 patients without a dis- tended epididymis still had discharge on cutting the epi- didymis (1 + in 6 patients and 2 + in one patient). All patients with distended epididymis had 1+ to 3 + dis- charge on cutting the epididymis. However, the post op- erative period is too short to assess the effect of these findings on the outcome of the surgery. ELISA for antisperm antibodies in the epididymal fluid was found to be positive in 16/30 (53.3%) patients. Negative results may have occurred in the remaining patients either because of the low concentration or the small amount of epididymal fluid available which was further diluted by the saline in which it was collected. Two of the patients with significant ELISA in the epidi- dymal fluid had positive antisperm antibodies in the se- rum. The histological findings of the epididymis and their correlation with ELISA results are represented in Table 1. Dilatation of ducts, epithelial breach and sperm ex- travasation can be considered a direct result of obstruc- tion and was demonstrated in 63.3%, 43.3% and 26.7% of the patients under study (Figures 1 & 2). Sperm in- gestion by macrophages was reported in 33.3% of the cases (Figure 3); in 8 cases epididymal discharge could be obtained and of these 75% had significant ELISA. Amongst the 22 cases with lymphocytic (majority T-lymphocytes), macrophage and plasma cell infiltration (Figures 4 & 5), 100% of the cases in whom epididymal fluid could be obtained had significant ELISA. In 12/14 patients with loss of cilia there was associated ductal dilatation; significantly 78.6% also had lymphocytic in- filtration and in 60% the ELISA was significant. None of the control group patients had any humoral or cellular evidence of local immune reaction. Thus, 22/30 patients had evidence of local immune reaction in the form of interstitial inflammatory cell in- filtrate in epididymal tissue and/or a positive ELISA for antiserm antibodies in epididymal fluid while 0/5 con- trols had evidence of local immune reaction. The differ- ence between cases and controls was statistically signifi- cant (p < 0.005). 4. Discussion Sperms are highly antigenic cells. During the onset of spermatogenesis at puberty, new developmental antigens make their appearance on the sperm surface [4]. It has been theorized that sequestration of developing sperm by the blood-testis barrier prevents the generation of autoan- Table 1. Effect of obstruction on the epididymal histology. Histological findings Patients (n = 30) Epididymal fluid absent Significant ELISA in epididymal fluid Dilatation of ducts 19 3 9/16 Loss of cilia 14 4 6/10 Presence of macrophages in ducts 18 4 9/14 Sperm ingestion by ma- crophages 10 2 6/8 Sperm extravasation 8 2 4/6 Epithelial breach 13 2 8/11 Lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration in inter- stitium 22 6 16/16 Macrophage infiltration in interstitium 4 0 3/4  A. K. SARDA ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS 34 Figure 1. Photomicrograph of the epididymis showing di- lated ducts with focal flattening of the epithelium (H&E x400). Figure 2. Photomicrograph of the epididymis showing epi- thelial flattening and breach, and extravasation of sperms. (H&E x400). Figure 3. Photomicrograph of the contents of the dilated epididymal ducts. Macrophages with phagocytosed sperms and desquamated lining cells are seen. (H&E x400) tibodies to sperm [5]. The products of sperm break- Figure 4. Photomicrograph of the epididymis showing sperm extravasation with interstitial cell infiltration (H&E x400). Figure 5. Photomicrograph of the epididymis showing in- terstitial collection of macrophages with a dilated epididy- mal duct to the left. (H&E x400) down on absorption would be an immense immunelogcal stimulus leading to immune response. However, T-lym- phocytes, representing 12.7% of the mucosal cell popu- lation of the epididymal epithelium [17] act as the im- munological suppressor barrier preventing such a re- sponse from occurring . Sperms are also segregated in the epididymis due to the presence of the tight junction complexes in the lining epithelium of the epididymis Which p r ev en t th e le ak ag e of sperm an tig ens and pr event their contact with local and circulating immune effector cells Any breach in the reproductive tract due to the v ar- ious factors leads an antibod y response against th e sperm. The two major classes of antisperm antibodies are IgG and IgA. IgG is a systemic immunoglobulin that is se- creted in a variety of tissues and fluid compartments. IgA, on the other hand, is a secretory antibody whose produc- tion may be locally mediated. Significant levels of IgM do not reach the reproductive tract fluid in the male and  A. K. SARDA ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS 35 it is unlikely that IgM an tibodies contribute to infertility. We studied the antisperm antibodies (IgA, IgG and IgM) in the serum of our patients and found that 3/30 patients were positive for the same. de Kretser et al have reported that antisperm antibodies occur more frequently in the serum of men with obstructive infertility than th e normal population [3]. This finding was confirmed in our study where 3/30 (10%) of our patients had positive serum antisperm antibodies as compared to 2% in the normal fertile men. Various authors have studied the effect of obstruction on the epididymal histology and on the sperms. Rajalakshmi et al found degenerative changes due to pressure effects [18], while McConnel observed fibrosis, sperm granuloma and interstitial macrophages [19]. Phadke observed epithelial breach, sperm extrava- sation, macrophages and interstitial inflammatory cells [13]. Hargreave et al observed interstitial infiltration by lymphocytes, macrophages and plasma cells with fibrosis and perivasculitis [20]. Phadke also observed ingestion of sperms by macrophages [13]. Rajalakshmi et al ob- served a higher percentage of morphological abnormali- ties and poor motility [18]. The commonest abnormal forms were sperms with pyriform head, the others being round, tapering, long and large heads as well as abnor- malities in midpiece and tail. We believe that breach of epididymal epithelium causes extravasation of sperms into the interstitium and brings then into contact with the antibody producing cells. If the exposure is not large enough to reach the lymph nodes, antisperm antibodies will not result in the serum. However, the exposure would be sufficient to produce antisperm antibodies locally which could then initiate a local cell mediated immune reaction with its attendant effects on the epididymis and sperms. Direct evidence for the production of antisperm anti- bodies locally was obtained in the present study where we found that ELISA for antisperm antibodies was posi- tive in the epididymal fluid in 16/30 (53%) of our pa- tients. This is an important observation establishing the role of local antigen-antibody reaction in patients of pri- mary obstructive infertility. If taken into conjunction with the fact that only three of the patients under study had raised antisperm antibodies in the serum, out of which only two patients had a positive ELISA for antis- perm antibodies in the epididymal fluid, this finding as- sumes further significance in establishing the importance of local production of antisperm antibodies in the epidi- dymis. We were unable to access any reported literature on this subject. Indirect evidence of the role of local antigen-antibody reaction in the epididymis is app arent in the observations on epididymal biopsy. We found that 22/30 (73%) pa- tients showed a lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate in the interstitium which is an indirect evidence of the oc- currence of an immune reaction. The local presence of antisperm antibodies in the epididymal fluid correlated well with the presence of lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration in the interstitium (p < 0.05). In our study 16/30 patients had a positive ELISA for antisperm anti- body and all these patients had interstitial lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration. In addition eight patients with negative ELISA also showed interstitial lympho- cytic and plasma cell infiltration. Thus 22/30 (73%) pa- tients had an evidence of a local immune reaction di- rectly in the form of a positive ELISA for antisperm an- tibodies in the epididymal fluid and/or indirect evidence in the form of lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate in the interstitium. None of the five controls had either a positive ELISA or lymphocytic infiltrate, this difference was found to be statistically signif icant (p < 0.005). Thus, we found a definite evidence of the presence of a local autoimmune reaction in patients of primary ob- structive infertility included in our study. It is possible that in six patients where lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration was present but ELISA for antisperm anti- body was negative and those cases with macrophage infiltration but negative ELISA, the local secretion of antibodies may have been in low concentration and was not detected by ELISA. The local antibody response was not studied in previ- ous reports of epididymal histology in obstructive infer- tility [13,18]. Phadke reported epithelial breach with sperm extravasation in patients of obstructive infertility [13]. He also found increased number of intraluminal and interstitial macrophages and suggested that these cells present the antigens to the local lymphatic sites where antibodies against spermatic antigens are produced. He suggested that it is likely that in cases of obstructive in- fertility some antigenic components of spermatozoa are also absorbed through intact epithelium and transferred to basal capillaries which may be responsible for devel- opment of autoantibodies against spermatozoa. Other authors also in their studies of the effect of obstruction on the epididymal histology have found an increased interstitial cell inflammatory infiltrate in cases of ob- structive azoospermia which is an evidence of the pres- ence of a local immune reaction [13,18,19], Phadke re- ported macrophage infiltration in the interstitium in 8/32 cases and perivascular accumulation of plasma cells in two cases [13], while a lymphocytic infiltration and fi- brosis was reported by McConnel [19]. These are pre- sumptive evidence of the presence of an antigen – anti- body reaction although a direct evidence of the presence local antibodies in these cases was not obtained. Since the histologic findings of the epididymis in their reports are similar to those in the presen t stud y, it is po ssible that  A. K. SARDA ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS 36 they also resulted from a local autoimmune reaction. However, lack of direct evidence of the presence of an- tisperm antibodies in the epidid ymal fluid precludes from coming to any positive conclusion regarding this aspect. In our study we found intraluminal macrophages in 18/30 cases and 9/18 of these cases had a positive ELISA for antisperm antibodies. Although this finding is statisti- cally insignificant, the negative ELISA could be ex- plained by the presence of antibodies in low titres in these cases. Thus there is enough evidence to suggest that a cell mediated immune response occurs in males with primary obstructive infertility and produces changes in both the luminal and extraluminal portio ns of the epididymis. The local immune response is likely to impair fertility through various likely mechanisms. In most epidemiologic stud- ies there is little evidence that suggests a cause/effect relationship between ASA and abnormality of the prin- cipal semen parameters (sperm count, motility and mor- phology) between infertile patients with and without ASA [1]. Sperm injury mediated by complement medi- ated sperm cytotoxicity is potentially possible. Although anticomplementary activity has been reported in human semen, this mechanism has been documented in the fe- male genital tract [1,21]. Antisperm antibodies and com- plement deposition resulted in a dramatic loss of sperm motility, as well as in activation and aggregation (roset- ting) of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) to anti- body- and complement-bound sperm [1]. Several studies suggest that ASA can interfere with sperm functions in- volved in the fertilization process by b locking sperm-egg interactions. This would affect natural fertilization and even in assisted reproductive techniques it has to be taken into account both as an interfering factor blocking sperm-egg interactions and also as a complicating factor due to ASA production after insemination [21]. 5. Acknowledgement The on-going stud y was conducted on behalf of and with grants-in-aid from the Department of Family Welfare, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, India 6. References [1] F. Francavilla, R. Romano, R. Santucci, G. L. Verghetta, P. D’Abrizio and S. Francavilla, “Naturally-Occurring Antisperm Antibodies in Men: Interference with Fertility and Implications for Treatment,” Frontiers in Bioscience Vol. 4, 1999, e9-25. doi:10.2741/Franca http://www.bioscience.org/1999/v4/e/franca/fulltext.htm [2] J. A. Collins, E. A. Burrows, J. Yeo and E. V. YoungLai, “Frequency and Predictive Value of Antisperm Antibod- ies among Infertile Couples,” Human Reproduction, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1993, pp. 592-598. [3] D. M. de Kretser, C. Huidobro, G. J. Southwick, and P. D. Temple-Smith, “The Role of Epididymis in Human Infer- tility,” Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, Vol. 53, Sup. 53, 1988, pp. 271-275. [4] M. A. Isahakia, “Characterization of Baboon Testicular Antigens Using Monoclonal Antisperm Antibodies,” Bi- ology of Reproduction, Vol. 39, No. 4, 1988, pp . 889-899. doi:10.1095/biolreprod39.4.889 [5] M. Dym, “The Fine Structure of the Monkey (Macaca) Sertoli Cell and Its Role in Maintaining the Blood-Testis Barrier,” Anatomical Record, Vol. 175, No. 4, 1973, pp. 639-656. doi:10.1002/ar.1091750402 [6] N. J. Alexander & D. J. Anderson, “Vasectomy. Conse- quences of Autoimmunity to Sperm Antigen,” Fertility and Sterility, Vol. 32, No. 3, 1979, pp. 253-260. [7] M. G. Munoz and S. S. Witkin, “Autoimmunity to Sper- matozoa, Asymptomatic Chlamydia Trachomatis Genital tract Infection and Gamma Delta T Lymphocytes in Se- minal Fluid from the Male Partners of Couples with Un- explained Infertility,” Human Reproduction, Vol. 10, No. 5, 1995, pp. 1070-1074. [8] L. Linnet, T. Hjort and P. Fogh-Andersen, “Association between Failure to Impregnate after Vasovasostomy and Sperm Agglutinins in Semen,” Lancet, Vol. 1, No. 8212, 17, 1981, pp. 117-119. [9] J. M. Parslow, T. A. Poulton, G. M. Besser and W. F. Hendry, “The Clinical Relevance of Classes of Immu- noglobulins on Spermatozoa from Infertile and Vasova- sostomised males,” Fertility and Sterility, Vol. 43, No. 4, 1985, pp. 621-627. [10] H. Meinertz, L. Linnet, P. Fogh-Andersen and T. Hjort, “Antisperm Antibodies and Fertility after Vasovasostomy: A Follow-up Study of 216 Men,” Fertility and Sterility, Vol. 54, No. 2, 1990, pp. 315-321. [11] B. Ayvaliotis, R. Bronson, D. Rosenfeld and G. Cooper, “Conception Rates in Couples Where Autoimmunity to Sperms is Detected,” Fertility and Sterility, Vol. 43, No. 5, 1985, pp. 739-742. [12] P. J. Turek, “Infections Immunology and Male Infertil- ity,” Infertility and Reproductive Medicine Clinics of North America, Vol. 10, No. 3, 1999, pp. 435-470. [13] A. M. Phadke, “Fate of Spermatozoa in Cases of Ob- structive Azoospermia and after Ligation of Vas Deferens in Man,” Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, Vol. 7, No. 1, 1964, pp. 1-12. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0070001 [14] A. K. Sarda, S. A. Bhalla , N. Sarda, P. C. Pal and S. Sal- han, “Effect of Primary Obstructive Infertility on Sperm Morphology”. The Internet Journal of Urology. Vol. 4, No. 2, 2007. http://www.ispub.com/ostia/index.php?xmlFilePath=jour nals/iju/vol4n2/sperm.xml [15] A. C. Chandley, N. MacLean, P. Edmond, J. Fletcher and G. S. Watson, “Cytogenetics and Infertility in Man II. Testicular Histology and Meiosis,” Annals of Human  A. K. SARDA ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS 37 Genetics, Vol. 40, No. 2, 1976, pp. 165-176. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.1976.tb00176.x [16] S. J. Silber & L. J. Rodriguez-Rigau, “Quantitative Anal- ysis of Testicle Biopsy. Determination of Partial Obstruc- tion and Prediction of Sperm Count after Surgery for Ob- struction,” Fertility and Sterility, Vol. 36, No. 4, 1981, pp. 480-485. [17] M. I. el-Demiry, T. B. Hargreave, A. Busuttil, K. James, A. W. Ritchie and G. D. Chisholm, “Lymphocyte Sub-popu- lations in the Male Genital Tract,” British Journal of Urology, Vol. 57, No. 6, 1985, pp. 769-774. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1985.tb07051.x [18] M. Rajalakshmi, B. V. Kumar, M. M. Kapur and P. C. Pal, “Ultrastructural Changes in the Efferent Duct and Epididymis of Men with Obstructive Infertility,” Ana- tomical Record, Vol. 237, No. 2, 1993, pp. 199-207. doi:10.1002/ar.1092370207 [19] E. M. McConnell, “The Histopathology of the Epidi- dymis in a Group of Cases of Azoospermia with Normal Testicular Function,” British Journal of Urology, Vol. 53, No. 2, 1981, pp. 173-178. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1981.tb03161.x [20] T. B. Hargreave, A. Busuttil, R. A. Elton, J. Harvey, A. Chan and G. D. Chisholm, “Studies of Testicular and Epididymal Damage in Relation to the Occurrence of An- tisperm Antibodies,” British Journal of Urology, Vol. 54, No. 6, December 1982, pp. 769-773. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1982.tb13645.x [21] F. Lombardo, L. Gandini, F. Dondero and A. Lenzi, “Immunology and Immunopathology of the Male Genital Tract. Antisperm Immunity in Natural and Assisted Re- production,” Human Reproduction Update, Vol. 7, No. 5, 2001, pp. 450-456. doi:10.1093/humupd/7.5.450 |