Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

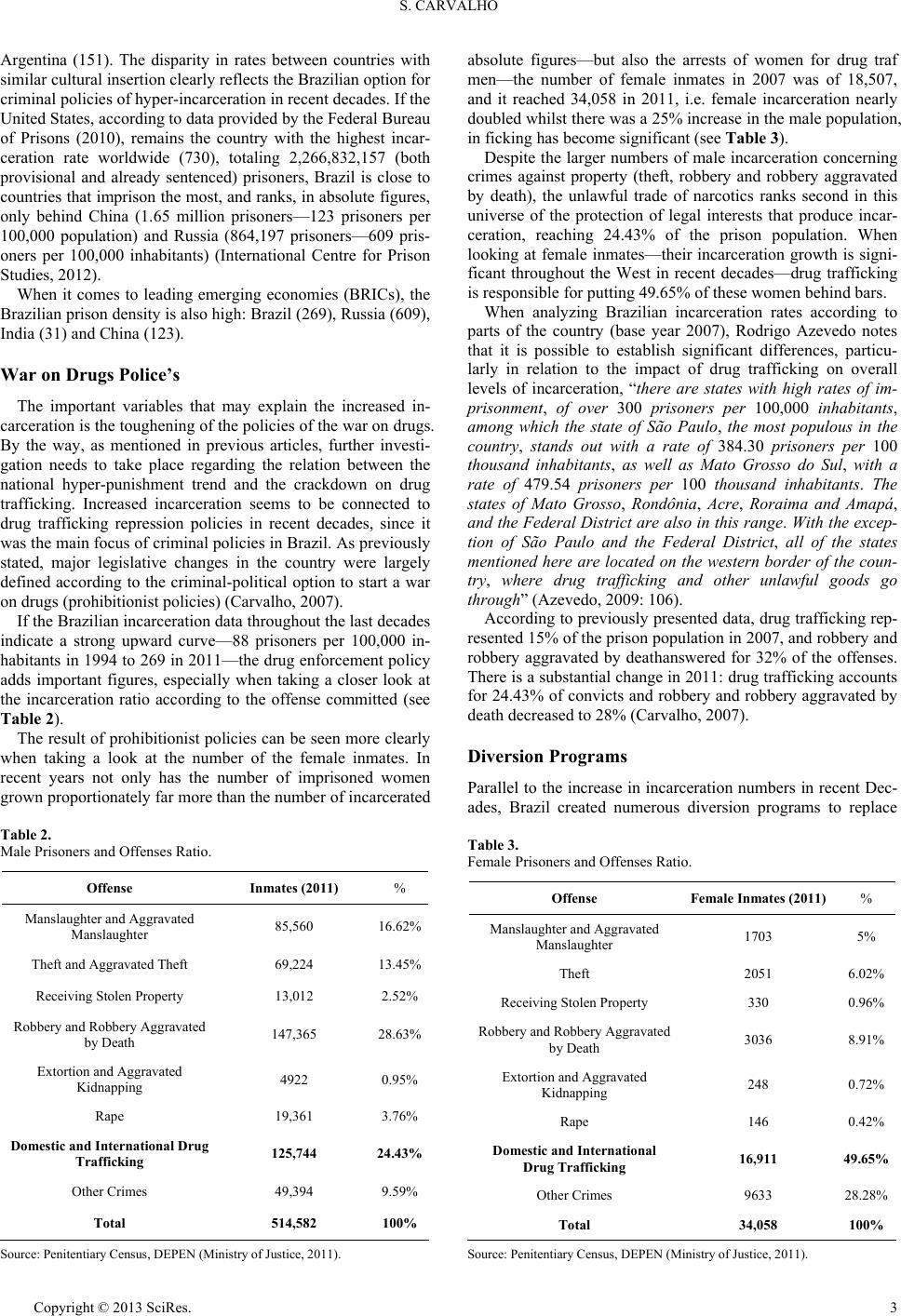

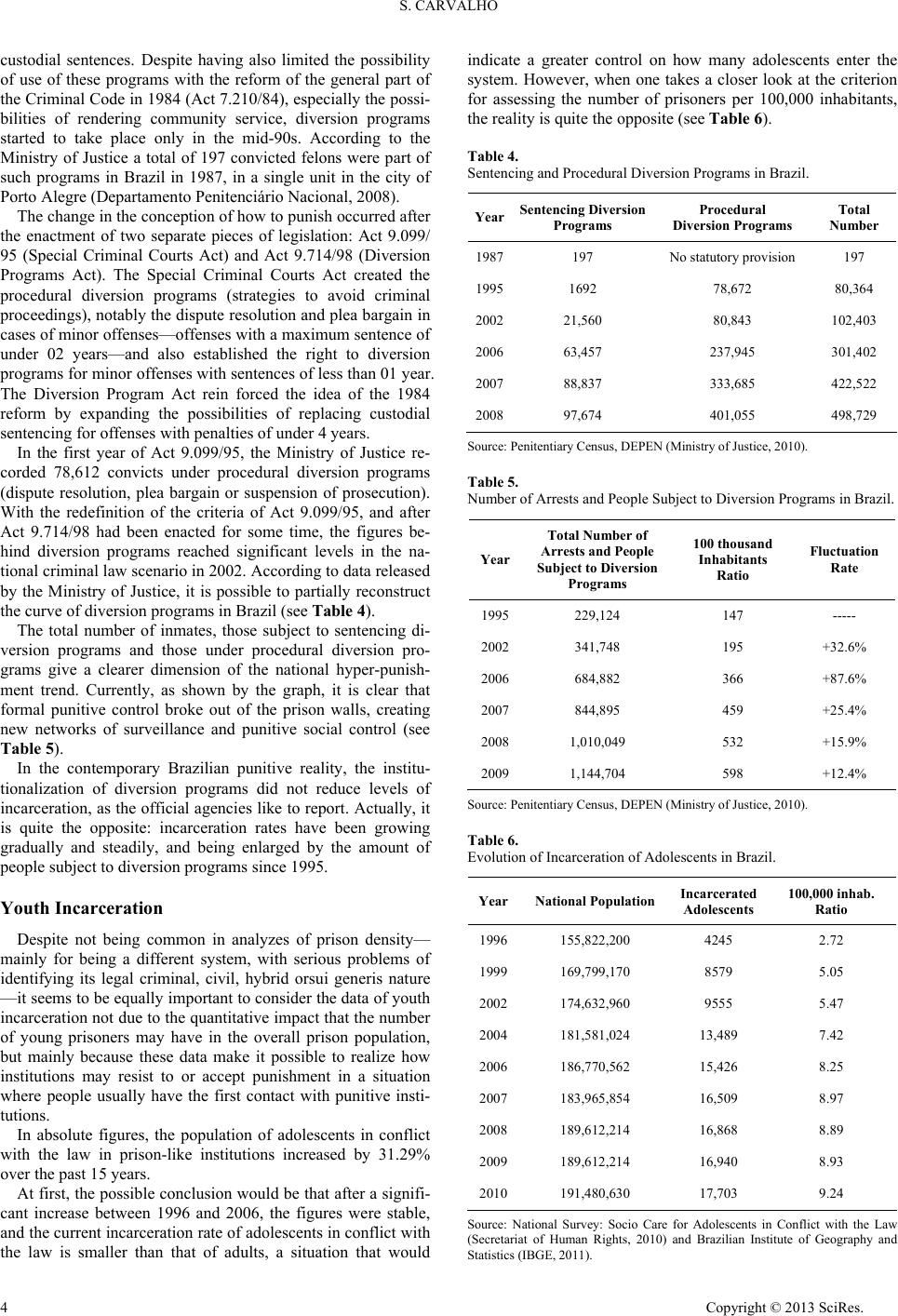

Open Journal of Social Sciences 2013. Vol.1, No.4, 1-12 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2013.14006 Published Online September 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss) Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 1 Theories of Punishment in the Age of Mass Incarceration: A Closer Look at the Empirical Problem Silenced by Justificationism (The Brazilian Case)* Salo Carvalho Universidade Federal de Santa M aria, Sa nta Mari a, Brazil Email: salo.carvalho@awsc.com.br Received August 6th, 2 013; revised September 6th, 2013; accepted September 13th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Salo Carvalho. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attri- bution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The paper examines three central problems involving punitive social control in recent decades: first, the steady increase in the number of incarcerated people (the phenomenon of great confinement), with special emphasis on the Brazilian case; second, the way criminology interprets contemporary confinement (New Penology); and finally, the lack of a (dogmatic) criminal law theory on the reality of mass incarceration. Incarceration data are presented here as premises in order to inquire about the relations between the (nor- mative-philosophical) theories regarding the justification of punishment and the (empirical) phenomena of mass incarceration. The questions behind the current reflection are therefore about what role criminal theories play in the expansion or contraction of the power to punish (potestas puniendi) and the explana- tions the justification models offer to the problem of hyper-punishment. Keywords: Punishment; Penology; Theories of Punishment The Urgency of Reality: Punitive Social Control Data in Brazil Expansion of Incarceration During the 1990s Brazilian legislators helped foster the ex- pansion of incarceration, partially boosted by the set of consti- tutional and criminal norms—due to the expansion of primary criminalization (the creation of new crimes) and the restriction of rights in the phase of the execution of the sentence. The re- sult of this experiment was the expansion of the number of inmates going into the system and the narrowing of the number of those who were ready to leave it. The most significant ex- ample of the punitive trend that guided criminal policies in the last decades was the enactment of Act 8.072/90, which in- creased punishment, withdrew progressive sentencing, in- creased the term for parole and obstructed the commutation and pardon for crimes known as heinous crimes. Despite the fact that Act 8.072/90 can be displayed as a milestone in the Brazilian punitive system, the legislative activ- ity in criminal matters in the post-democratic transition was intense. The creation of numerous crimes, the quantitative ex- pansion and stiffening of punishment made the system highly complex and also contradicting, a situation that fosters incar- ceration in a punitive culture. The fragmentation of the system created problems that led to the creation of committees of ex- perts by the Senate and House of Representatives in order to draft a new Criminal Code, governed by the principle “no pun- ishment out of the Criminal Code” (the gathering of the existing statutes in a single text, making sure the penalties are propor- tional among themselves). In criminal procedure, topical changes in the Code and the creation of independent laws fostered the expansion of secon- dary criminalization. Regarding provisional detention, not only were the possibilities for provisional detention (re)structured, e.g. temporary arrest (Act 7.960/89) as well as new restrictions and the impossibility to post bail for some crimes (Act 7.716/89, Act 8.072/90, Act 9.034/95 and Act 9.455/97)—but also a form of early implementation of the sentence before the judgment of a conviction becomes unappealable was created (Act 8.038/90). As previously anticipated, numerous factors contributed to the increased rates of incarceration in the legislative sphere: 1) the creation of new crimes based on the list of new legal inter- ests expressed in the Constitution (criminal arena); 2) the in- crease of the amount of custodial sentences in numerous and distinct offenses (criminal arena), 3) the shortening of criminal procedures, with the extension of precautionary detention hy- potheses (preventive detention and provisional detention) and a decrease on the possibilities of bail (criminal procedure arena), 4) the creation of the early execution of the sentence, regardless of a final conviction (criminal procedural and execution of the sentence arena), 5) the toughening on the serving of the sen- tence, with the extension of deadlines for implementing pro- gressive sentencing and parole (execution of the sentence arena), 6) the limitation of the possibility of extinguishing pun- ishment with the toughening of the criteria for pardon, grace, amnesty and commutation (execution of the sentence arena), 7) *This paper is dedicated to my friend Geraldo Prado. It was prepared for the 4th Session of the International Forum on Crime and Criminal Law in the Global Era (IFCCLGE), December 2012, Beijing, China (www.ifcclge.com).  S. CARVALHO the expansion of the powers of the prison administration to report the behavior of the convict, whose effects affect those serving the sentence (e.g. Act 10.792/03) (prison arena) (Car- valho, 2012: 35). Moreover, it is important to realize that incarceration rates do not stem exclusively from eminently legislative attitudes. Par- allel to the political and criminal expansion in the sphere of legal production, numerous studies demonstrate how punish- ment gradually seeped into the culture of the legal actors, espe- cially in the judiciary, a situation that hindered the effectiveness of normative minimizers of incarceration filters. Regarding the punitive culture of the actors of the criminal justice system, there are important investigations, some produced in the judi- cial institutions themselves, support the hypothesis (Associação dos Magistrados Brasileiros, 2006; Azevedo, 2005; Carvalho, 2010; Instituto Brasileiro de Ciências Criminais, 2007; Instituto Latino-Americano das Nações Unidas para Prevenção do Delito e Tratamento do Delinquente, 2005). Rates of Incarceration and Non-Custodial Punitive Control The effects of the rising punitive culture within the criminal agencies (Institutions of Production, Application and Enforce- ment of Criminal Law) had a direct impact on the rates of in- carceration and non-custodial punitive control (Sentencing and Procedural Diversion Programs). The staggering number of inmates and the outstanding failure of public officials in pro- viding minimally adequate conditions to maintain people in custodial sentences transformed the national punitive system into one of an explicit and permanent violation of human rights. The urgency limits have been long surpassed; there are numer- ous facts that, using the exact words of Geraldo Prado (2001), reveal the indecency of criminal enforcement in Brazil on a daily basis. But the urgency of the situation is not limited to the quantita- tive growth of the number of people arrested, but especially to the inhuman conditions prisoners are subject to. The national prison situation has been described in numerous academic arti- cles and institutional reports in recent decades. The lack of material (poor hygiene), medical, psychological, social, phar- maceutical, dental, legal and educational assistance is increased by the horror of a reality marked by the pathological violence of idleness, torture, ill-treatment and exploitation of prisoners and their families by public officials and by other convicts1. According to consolidated data by the National Penitentiary Department (DEPEN), the Brazilian prison population was of 514,582 inmates by the end of 2011. If these numbers are com- pared to the population index presented by the Brazilian Insti- tute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE)—later reproduced by the Ministry of Justice-Brazil would have reached, in December 2011, an index of 269.79 inmates per 100,000 inhabitants. Upon analyzing the increase of the prison population curve in the last two decades, one can see that the political-criminal option to toughen the punitive apparatus has achieved undeni- able success in increasing hyper-punishment. These numbers take alarming proportions from the point of view of the protec- tion and enforcement of human rights (see Table 1). If the results presented by Brazil (269) and the countries of the European Community (2010 data) are put together, it is clear that the degree of incarceration (number of prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants) largely overcomes those of countries like Portugal (109), Spain (160), France (102), Italy (112), England (153) and Germany (88), and are closer to those of Eastern European countries, such as Estonia (265) and Lithuania (260). These countries are only topped by Belarus (483), Ukraine (318) and, notoriously, Russia (609), the country with the largest incarcerated population density on the continent (International Centre for Prison Studies, 2012). Brazil ranks fourth in number of prisoners per 100,000 in- habitants in South America and is topped only by French Guiana (316), Suriname (356) and Chile (313). All other coun- tries in the continent have lower levels of incarceration: Argen- tina (151), Bolivia (93), Colombia (142), Ecuador (136), Para- guay (99), Peru (154) and Venezuela (85). The only countries with ratios closer to the Brazilian one are Uruguay (261) and Guyana (289) (International Centre for Prison Studies, 2012). When comparing Brazil and Argentina, due to their similar geographical, political, social and economic contexts, there is a significant difference in the punitive policies-Brazil (269) and Table 1. Number of inma tes p er 100,000 inhabitants in B razil. YearPopulation Inmates Inmates/100,000 inhab. 1994 147,000,000 129,169 87.87 1995 155,822,200 148,760 95.47 1997 157,079,573 170,207 108.36 2000 169,799,170 232,755 137.08 2001 172,385,826 233,859 135.66 2002 174,632,960 239,345 137.06 2003 176,871,437 308,304 174.31 2004 181,581,024 336,358 185.24 2005 184,184,264 361,402 196.22 2006 186,770,562 401,236 214.83 2007 183,965,854 419,551 228.06 2008 189,612,214 451,219 238.10 2009 189,612,214 473,626 247.35 2010 191,480,630 496,251 260.18 2011 190,732,694 514,582 269.79 1In this s ense, in o rder to check the l ack of stat e action in the las t decades , it is interesting to compare the report published in 2009 by the House of Rep- resentatives, the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry about the Prison System, with some important documents of the 1990’s—for example, Am- nesty International, 1993; Amnesty International, 1999; Confederação Na- cional dos Bispos do Brasil, 1997; Human Rights Watch, 1998. The reports only state the facts anticipated by national scholars in two landmark studies: Fragoso, C ato & Sussenkind, 1980; Thompson, 1991. Source: Penitentiary Census, DEPEN (Ministry of Justice, 2011) and the Brazil- ian Institute of Geogr a phy and Stat istics (IBGE , 2011)2. 2The wide range of the data regarding the number of inhabitants is due to differen ces between t he data repo rted by the Pen itentiary Dep artment ( Min- istry of Just i ce) and the IBGE. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 2  S. CARVALHO Argentina (151). The disparity in rates between countries with similar cultural insertion clearly reflects the Brazilian option for criminal policies of hyper-incarceration in recent decades. If the United States, according to data provided by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (2010), remains the country with the highest incar- ceration rate worldwide (730), totaling 2,266,832,157 (both provisional and already sentenced) prisoners, Brazil is close to countries that imprison the most, and ranks, in absolute figures, only behind China (1.65 million prisoners—123 prisoners per 100,000 population) and Russia (864,197 prisoners—609 pris- oners per 100,000 inhabitants) (International Centre for Prison Studies, 2012). When it comes to leading emerging economies (BRICs), the Brazilian prison density is also high: Brazil (269), Russia (609), India (31) and China (123). War on Drugs Police’s The important variables that may explain the increased in- carceration is the toughening of the policies of the war on drugs. By the way, as mentioned in previous articles, further investi- gation needs to take place regarding the relation between the national hyper-punishment trend and the crackdown on drug trafficking. Increased incarceration seems to be connected to drug trafficking repression policies in recent decades, since it was the main focus of criminal policies in Brazil. As previously stated, major legislative changes in the country were largely defined according to the criminal-political option to start a war on drugs (prohibitionist policies) (Carvalho, 2007). If the Brazilian incarceration data throughout the last decades indicate a strong upward curve—88 prisoners per 100,000 in- habitants in 1994 to 269 in 2011—the drug enforcement policy adds important figures, especially when taking a closer look at the incarceration ratio according to the offense committed (see Table 2). The result of prohibitionist policies can be seen more clearly when taking a look at the number of the female inmates. In recent years not only has the number of imprisoned women grown proportionately far more than the number of incarcerated Table 2. Male Prisoners and Offenses Ratio . Offense Inmates (2011) % Manslaughter and Aggravated Manslaughter 85,560 16.62% Theft and Aggravated Theft 69,224 13.45% Receiving S t olen Prope rt y 13,012 2.52% Robbery an d Robbery Aggravated by Death 147,365 28.63% Extortion and Aggravate d Kidnapping 4922 0.95% Rape 19,361 3.76% Domestic and Internat ional Drug Trafficking 125,744 24.43% Other Crimes 49,394 9.59% Total 514,582 100% Source: Penitentiary Census, DEPEN (Ministry of Justice, 2011). absolute figures—but also the arrests of women for drug traf men—the number of female inmates in 2007 was of 18,507, and it reached 34,058 in 2011, i.e. female incarceration nearly doubled whilst there was a 25% increase in the male population, in ficking has become significant (see Table 3). Despite the larger numbers of male incarceration concerning crimes against property (theft, robbery and robbery aggravated by death), the unlawful trade of narcotics ranks second in this universe of the protection of legal interests that produce incar- ceration, reaching 24.43% of the prison population. When looking at female inmates—their incarceration growth is signi- ficant throughout the West in recent decades—drug trafficking is responsible for putting 49.65% of these women behind bars. When analyzing Brazilian incarceration rates according to parts of the country (base year 2007), Rodrigo Azevedo notes that it is possible to establish significant differences, particu- larly in relation to the impact of drug trafficking on overall levels of incarceration, “there are states with high rates of im- prisonment, of over 300 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants, among which the state of São Paulo, the most populous in the country, stands out with a rate of 384.30 prisoners per 100 thousand inhabitants, as well as Mato Grosso do Sul, with a rate of 479.54 prisoners per 100 thousand inhabitants. The states of Mato Grosso, Rondônia, Acre, Roraima and Amapá, and the Federal District are also in this range. With the excep- tion of São Paulo and the Federal District, all of the states mentioned here are located on the western border of the coun- try, where drug trafficking and other unlawful goods go through” (Azevedo, 2009: 106). According to previously presented data, drug trafficking rep- resented 15% of the prison population in 2007, and robbery and robbery aggravated by deathanswered for 32% of the offenses. There is a substantial change in 2011: drug trafficking accounts for 24.43% of convicts and robbery and robbery aggravated by death decreased to 28% (Carvalho, 2007). Diversion Programs Parallel to the increase in incarceration numbers in recent Dec- ades, Brazil created numerous diversion programs to replace Table 3. Female Prisoners and Offenses Ratio. Offense Female Inm ates (2011)% Manslaughter and Aggravated Manslaughter 1703 5% Theft 2051 6.02% Receiving S tolen Property 330 0.96% Robbery an d Robbery Aggravated by Death 3036 8.91% Extortion and Aggravate d Kidnapping 248 0.72% Rape 146 0.42% Domestic and I nt ernational Drug Trafficking 16,911 49.65% Other Crim es 9633 28.28% Total 34,058 100% Source: Penitentiary Census, DEPEN (Ministry of Justice, 2011). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 3  S. CARVALHO custodial sentences. Despite having also limited the possibility of use of these programs with the reform of the general part of the Criminal Code in 1984 (Act 7.210/84), especially the possi- bilities of rendering community service, diversion programs started to take place only in the mid-90s. According to the Ministry of Justice a total of 197 convicted felons were part of such programs in Brazil in 1987, in a single unit in the city of Porto Alegre (Departamento Penitenciário Nacional, 2008). The change in the conception of how to punish occurred after the enactment of two separate pieces of legislation: Act 9.099/ 95 (Special Criminal Courts Act) and Act 9.714/98 (Diversion Programs Act). The Special Criminal Courts Act created the procedural diversion programs (strategies to avoid criminal proceedings), notably the dispute resolution and plea bargain in cases of minor offenses—offenses with a maximum sentence of under 02 years—and also established the right to diversion programs for minor offenses with sentences of less than 01 year. The Diversion Program Act rein forced the idea of the 1984 reform by expanding the possibilities of replacing custodial sentencing for offenses with penalties of under 4 years. In the first year of Act 9.099/95, the Ministry of Justice re- corded 78,612 convicts under procedural diversion programs (dispute resolution, plea bargain or suspension of prosecution). With the redefinition of the criteria of Act 9.099/95, and after Act 9.714/98 had been enacted for some time, the figures be- hind diversion programs reached significant levels in the na- tional criminal law scenario in 2002. According to data released by the Ministry of Justice, it is possible to partially reconstruct the curve of diversion programs in Brazil (see Table 4). The total number of inmates, those subject to sentencing di- version programs and those under procedural diversion pro- grams give a clearer dimension of the national hyper-punish- ment trend. Currently, as shown by the graph, it is clear that formal punitive control broke out of the prison walls, creating new networks of surveillance and punitive social control (see Table 5). In the contemporary Brazilian punitive reality, the institu- tionalization of diversion programs did not reduce levels of incarceration, as the official agencies like to report. Actually, it is quite the opposite: incarceration rates have been growing gradually and steadily, and being enlarged by the amount of people subject to diversion programs since 1995. Youth Incarceration Despite not being common in analyzes of prison density— mainly for being a different system, with serious problems of identifying its legal criminal, civil, hybrid orsui generis nature —it seems to be equally important to consider the data of youth incarceration not due to the quantitative impact that the number of young prisoners may have in the overall prison population, but mainly because these data make it possible to realize how institutions may resist to or accept punishment in a situation where people usually have the first contact with punitive insti- tutions. In absolute figures, the population of adolescents in conflict with the law in prison-like institutions increased by 31.29% over the past 15 years. At first, the possible conclusion would be that after a signifi- cant increase between 1996 and 2006, the figures were stable, and the current incarceration rate of adolescents in conflict with the law is smaller than that of adults, a situation that would indicate a greater control on how many adolescents enter the system. However, when one takes a closer look at the criterion for assessing the number of prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants, the reality is quite the opposite (see Table 6). Table 4. Sentencing and Procedural Di v e rsion Programs in Brazil. Year Sentencing Diversion Programs Procedural Diversion Pr ograms Total Number 1987197 No statutory provision 197 19951692 78,672 80,364 200221,560 80,843 102,403 200663,457 237,945 301,402 200788,837 333,685 422,522 200897,674 401,055 498,729 Source: Penitentiary Census, DEPEN (Ministry of Justice, 2010). Table 5. Number of Arrests and People Subject to Diversion Programs in Brazil. Year Total Number of Arrests and P eople Subject to Diversion Programs 100 thousand Inhabitants Ratio Fluctuation Rate 1995229,124 147 ----- 2002341,748 195 +32.6% 2006684,882 366 +87.6% 2007844,895 459 +25.4% 20081,010,049 532 +15.9% 20091,144,704 598 +12.4% Source: Penitentiary Census, DEPEN (Ministry of Justice, 2010). Table 6. Evolution of Incarceration of Adoles cents in Brazil. YearNational Population Incarcerated Adolescents 100,000 inhab. Ratio 1996155,822,200 4245 2.72 1999169,799,170 8579 5.05 2002174,632,960 9555 5.47 2004181,581,024 13,489 7.42 2006186,770,562 15,426 8.25 2007183,965,854 16,509 8.97 2008189,612,214 16,868 8.89 2009189,612,214 16,940 8.93 2010191,480,630 17,703 9.24 Source: National Survey: Socio Care for Adolescents in Conflict with the Law (Secretariat of Human Rights, 2010) and Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE, 2011). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 4  S. CARVALHO As one can see, the number of adolescents incarcerated per 100,000 inhabitants grew from 2.72 to 9.24 between 1996 and 2010, i.e. 239.7%. In absolute figures, the number of incarcer- ated adolescents increased from 4245 to 17,703, or 317.03%. In the same period (1995-2010), there was a variation of 95.47 to 259.17 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants in the adult impris- onment rate, representing an increase of 171%. In absolute figures, the number of adults incarcerated rose from 148,760 to 496,251, or 233.59%. It is important to emphasize that during the same time the national population increased only by 22.88%. The numbers indicate that the incarceration of adolescents due to the so-called “juvenile offenses” significantly beats the incarceration rates of adults convicted of offenses, which clearly shows the national trend of hyper-punishment at all levels of formal control. The Criminological Critic to the Punitive Trend Hypotheses for Contemporary Punitive Trend The steep increase in global levels of incarceration in recent decades has become a fact that challenged criminology to draft explanatory schemes. It can be argued, also, that the phenome- non of great confinement went in the opposite direction of the trend of gradual decrease of the carceral archipelago (Foucault), as foreseen by the criminal science of the 1970s. Pavarini (2009) summarizes some of the explanatory hy- potheses for contemporary punitive trend: 1) increased crime; 2) increased repressive criminal legislation (primary criminaliza- tion), 3) a great support among actors of the criminal justice system to hyper-punishment (secondary criminalization), and 4) new forms of social control in a structured actuarial and tech- nocratic management of public safety. The first three hypothe- ses were kind of single-cause explanatory schemes, unlike the last one that would reestablish the macro-level sociological model of social construction. The first possible conclusion, according to him, would be that there are significant flaws in the single-cause explanations models, a reason that would make it clear of why it was not feasible to reduce the phenomenon of incarceration to a deterministic causal ap pr oach. Criminological researches have shown, for example, that there is not a clear relation between the growth of crime record rates and the increase in the incarceration rate. Crime and in- carceration are distinct phenomena, although some explanatory variables are related to both of them3. Similarly, it is possible to say that the social perception of rising crime, which deepens the sense of fear and insecurity (moral panics) also do not match the reality of the phenomenon of crime, i.e., feelings of insecu- rity are not an accurate reflection of changes in crime rates4. Furthermore, evidence regarding legislative policies (primary criminalization)—as well as judicial and administrative policies (secondary criminalization)—is also not an isolated factor. The change in the normative structure (primary criminalization) is artificially induced; crime is a political entity and not a natural one. However, despite crime being a phenomenon and not an assumption, criminal and political changes often appear linked to concrete phenomena as the improvement of record keeping (official crime numbers) and overestimation of contingent situations that increase the perception of social insecurity. De- spite the difficult construction of evaluation methodologies, both phenomena (crime records and sense of insecurity) can be analytically seen in criminological diagnosis through empirical research—one should point out, of course, the difference be- tween the statistical accuracy of crime record rates and the sense of insecurity rates. On the other hand, criminological research has shown that agencies that help shape the criminal justice system (mass me- dia, for example) explore crime and insecurity rates as an im- portant factor in triggering contingent punitive responses (puni- tive populism), revealing a close relationship between the first and second theses about increased incarceration. One can also note that, despite being strategic in the chain of criminality, the attitude of the actors of the criminal system (secondary criminalization) does not have an isolated role and cannot, by itself, determine an incarceration policy. There is no doubt that the inclusion of operators of the criminal justice system in an inquisitorial culture fosters the punitive trend, for the way to interpret and apply the rules allows the expansion of the filters that could halt the number of inmates going into the system. However, especially in the judiciary system, due to the liberal tradition and normative force that the Constitutions have acquired from the second half of the last century on, there are frequent resistance movements. Also, thinking about the con- nection between the actors of the criminal justice system and the experience of the great confinement would necessarily im- ply the inclusion of these practices in the economic, criminal and political context, for they are not isolated from the cultural processes (historical, social and political ones) that shape the inquisitorial (or guarantism-focused) mindset (instrumental rationality). The failures (gaps and contradictions) presented by single- cause models stem from the fragmentation of the effects of the punitive culture (incarceration based) at a fixed point that represents the source of the problem (increased crime, legisla- tive processes of criminalization, attitude of the actors of the criminal system). Penal State Besides the single-cause hypotheses highlighted by pavarini, there would still be a fourth explanation of a macro-level criminological nature that seeks to locate the problem of the punitive trend as a result of political and economic changes in Western countries after the crisis of the social welfare states and the consolidation of the penal state among the critical criminological trends it is possible to identify a general agree- ment that understands the mass incarceration phenomenon as a consequence of the consolidation of the neo liberal political economy. The dismantling of the welfare state institutions crushed assistance and social inclusion policies, eventually affecting criminal matters. 3In this sense, Larrauri argues, “the fact that increasing incarceration is no t correlated to crime rates is a conclusion widely accepted by criminologica l literature, whatever its ideological orientation” (Larrauri, 2009: 04). The data presented by Garland on crime and im p risonment records in the United States and in Great Britain between 1950 and 1998 (Garland, 2001: 208) and the comparative figures given by Wacquant regarding crimes as well as prison population in the US in 1975 and in 1999 (Wacquant, 2008: 10) leaves no doubt about it. 4“Crime and fear of crime are not like an object and its reflection on the mirror. Feeling threatened and insecure are not mere reflection s of rea l threats, but also the consequence of circumstances of de- s ocialization an d social unrest ” (Hassemer, 1994: 163). The structure of correctionalism, created based on the posi- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 5  S. CARVALHO tive special prevention models, is unthinkable outside of the interventionist state. Not for any other reason Garland calls the predominant model in the last century (correctionalism) as pe- nal-welfare. Prison represents a strategic institution in this con- text because it is responsible for correcting individual learning deficits that were not sufficiently reinforced by other agencies of social control, particularly school. It would up to the crimi- nological lab, therefore, to (re)create favorable conditions so that the offender could be reinstated to social life. But if during the implementation period of the Liberal State to Welfare State the absenteeism conception became more interventionist-based on policies that built welfare institutions, with the financial and political crisis of the welfare state these same structures were reduced to minimum acceptable ones according to the designs of public policies established on the basis of efficiency and the actuarial management approach. The actions of punitive agencies are therefore redirected due to the impact of neo liberal economic policies in the structures of correctionalism. In this respect, the interpretation resources provided by critical criminology remain valid, allowing the understanding of the decisive influence of the neoliberal project in the (re)training of the punitive approach, especially in pris- ons and its legitimating discourses (punishment the ories). Among the critical readings, the one made by Wacquant can be highlighted. When analyzing economic processes of recent decades and the new techniques of punishment, Wacquant (2004) brings prisons and the experience of ghettos produced in the new capitalism together. According to the author, the ghettos today are two-fold instruments of ethnoracial closure and control, a social-organizational device that employs space to reconcile the two antinomic purposes: economic exploitation and social os- tracization. When faced with the reality of the predominant and growing representation of African-Americans in the punitive system, Wacquant argues there is a process of redefinition of prison in the new order: to offset and complement the bank- ruptcy of the ghetto as a mechanism for refraining the hazard- ous and superfluous population from both an economic and a political point of view—“prison is merely the ultimate manifes- tation of a policy of exclusion of which the ghetto has been a means and an end since it first appeared in history” (Wacquant, 2008:13). The urban ghetto—a special form of collective violence typical of large population areas—would represent an ideal type, a hypothesis matrix, a symbolic incubator, which allows the interpretation of other similar institutions of forced confinement of marginalized groups such as prisons and refugee camps. Prison, therefore, acquires a new feature in the Penal State, one that is totally different from the one sanctioned by theories of positive special prevention. In the void left by the Welfare State and its correctional policies, prisons are conceived to control segregation, acting as one of the mechanisms for man- aging poverty and the technocratic control of unwanted groups (ill-adjusted individuals and social misfits)—“the ‘punitive refraining’ of the layers of the precarious new urban proletar- iat policy has spread across the planet in the wake of economic neoliberalism” (Wacquant, 2009: 12). In the same track, Bauman brings together the phenomena of the reinventing of prison and the sanctioning of punishment with the crisis of the welfare policies and the social experience of chronic unemployment: “in the current circumstances, con- finement is an alternative to employment, a way to use or neu- tralize a considerable portion of the population that is not nec- essary for production and for which there is no work to which they can be reinstated to” (Bauman, 1999: 119). Thus, the re- awakening of prison is directly connected to the need to create an isolated space (confinement) for the surplus population. New Penology After discrediting the single cause theories that explain mas- sive incarceration, Pavarini shifts his critique to the social con- struction of punitive models, emphasizing its geopolitical rela- tivity according to the author, “the theories that refer to the paradigm of social construction, although interesting for being more intellectually sophisticated, insist on the hegemonic presence of economic, political and cultural aspects—from the production of surplus populations to the need to impose new ethics, the role of the military lobby and the control of the irre- versible crisis of endogenous forms of social control—that are certainly present and decisive, but only in some geopolitical areas and not in others” (Pavarini, 2009: 246). While acknowledging the theoretical difficulty, Pavarini suggests an explanation to the phenomenon of mass confine- ment. The author argues that it would be possible to see, espe- cially after the end of the East West fragmentation (capitalism and communism), the incorporation of the US social control models by marginal countries. Due to the economic, political and cultural hegemony, there would have been a sort of “Americanization of the outskirts”. Thus, US political and criminal models and criminological theories would have been diffused everywhere, as a sort of a habit. The author argues that the worldwide increase of incarcera- tion rates could be explained by the single cause or macro-level sociological models only if, in this historical contingency, 1) the increase in crime, 2) the spread of insecurity, 3) the exclu- sionary practices imposed by the market, 4) the new processes of mobility determined by globalization and 5) the reduction of the Welfare State were perceived as “elements through which— the predominant effects of “Capitalism”—a new moral phi- losophy, a certain ‘point of view’ about good and evil, about lawful and unlawful, about the worthiness of inclusion or ex- clusion is constituted and spread in an universal way” (Pavarini, 2009: 249). The new universal philosophy about the (un) lawful and spread across nations from the center to the outskirts as a model (or art) of social control would be represented in the new dis- courses on punishment (New Penology). The New Penology—or fundamentalist Penology, in the words of Pavarini (2009)—operates through the diffusion of a populist culture of punishment sanctioned “from below”. It is a culture of repression that is sprayed in the speeches of the population (common sense), disseminated by the media and incorporated by major theorists of the academic community (scientific legitimacy). It is a new way of perceiving punish- ment, with criminal policies of strong populist appeal and that cannot be solely classified as a “right-wing policy” for it is shared by numerous left and center-left wing governments (for example, some experiences of the new realism of the left). The new penal discourse that emerges from the 1990s in the United States 1) politically inspired in the zero tolerance ideas, 2) academically grounded in situationist authoritarian theories (the broken windows theory, for example) and 2) normatively crystallized with the institutionalization of the “three strikes” Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 6  S. CARVALHO criminal laws in important US states—seeks to recover the prestige of prison by abandoning traditional purposes attributed to punishment (correction, intimidation or retribution). The romantic appeal of (re)socializing is left behind in favor of the idea of controlling and managing the risks posed by certain individuals or dangerous groups. Garland, when analyzing the managerial models, notes that the new punitive approach changes the foundations of the criminological discourse in its most significant aspects: the functions of punishment and the image of the criminal individ- ual. As he highlights, one of the features of the New Penology is that the criminological discourse became more statistical, more actuarial, aimed at identifying risk groups and populations, unlike correctionalism when the individual was the core of the punitive discourse (Garland, 2004: 55). If the correctional mod- els of positive special prevention perceived crime as a result of an individual pathology, the actuarial theories (Wilson & Clarke) seek to explain the phenomenon based on the economic approach of rational choice and utility. Wilson admits hypotheses built based on and through com- mon sense (popular opinion) in the sense that it would be pos- sible to explain how people become criminals in the same way as they become carpenters or even buy a car. According to the author, popular knowledge is based on a certain theory of hu- man nature that understands that people act thinking about the estimate between costs and benefits—“people lead their lives electing rewards and penalties of all kinds”. (Wilson, 2005: 336) So criminals would act according to the expectation of the penalty “as sanctions become more likely, crime become less common” (Wilson, 2005: 337). He emphasizes, however, that due to high social risk, the formula of rational choice would not be applied in some situations (pathological personalities, for example). This equation used to explain the individual deviant act is significantly magnified. This is because the actuarial policies seek to recognize and neutralize hazardous groups who threaten stability and security. Besides creating an explanatory model of the criminal act, the New Penology seeks to identify risk groups and manage potential offenders. The correctionalist idea of individual dangerousness is converted into a collective danger- ousness. Punishment—as a normative response to crime—and prison—as an institution that makes criminal sanction possible- will be justified as mechanisms of disabling dangerous indi- viduals or groups (positive general prevention). The perception of the risk (of commiting crimes) sanctions the restraint of freedom. In Feeley and Simon’s (2005) point of view, the New Pe- nology emerges in order to innovate the techniques of identify- ing subpopulations, defining new risk groups. Michelle Brown (2006) argues that the focus of managerial theories in hazard- ous or risk groups resumes a key category of processes of criminalization criticized by radical criminology (Marxist criminology)—the dangerous classes. In this scenario, new instruments and new surveillance tech- niques are incorporated into the administration of the criminal justice system in order to increase the performance of manage- ment, with the subsequent expansion of punitive control. Thus, automation projects are inserted into the spaces of prison ad- ministration and into the management of urban public safety. If in the penal welfare project the ideal of rehabilitation depended on the interaction between the convict and those responsible for the penal treatment (psychologists, social workers or teachers), in the managerial approach, humans are replaced by surveil- lance cameras, electronic monitoring, drug testing, computer- ized CT scans. As stressed by Feeley and Simon, these innovations in the punitive control field lead to the expansion of criminal sanc- tions and the inversion of punitive approach, especially when it comes to assessing the levels of recidivism. In the old correc- tional model, “the high rates of return to prison while serving parole indicated flaws in the program; now they provide indi- cators of efficiency and effectiveness of probation as a control device” (Feeley & Simon, 2005: 436). Punishment Justification Theories and Mass Incarceration Based on the hypotheses presented by Pavarini, especially in relation to macro-level criminological explanations of the phe- nomenon of great confinement, it is possible to elaborate a concept map composed of some conclusions and new questions that seek to evaluate the remodeling of the functions of prison and punishment in the new phase of global capitalism, espe- cially in the outskirts. The first defiance that seems relevant is about the real (non)necessity of a central hypothesis explaining the phenomenon of mass incarceration. The defiance concerns the tendency of modern science of determining an origin to the phenomena. The definition of a source or emergency point would make it possible to historically rebuild the object of study, a procedure that would allow its full understanding. This approach derives from the Cartesian idea that to get to the truth the investigator must dismember the object to the smallest par- ticle possible, researching the parts individually to later make its reunification. Understanding the particles would allow therefore the understanding of the entire object of the research. But this model of interpretation cannot explain complex phe- nomena of contemporary life, such as mass incarceration. All variables presented (single cause ones and macro-level sociological ones) acquire a high degree of importance when examined together, though they cannot alone explain mass incarceration. However this is not just a simple addition, as punishment philosophers would like it to be when they merge theories of justification (hybridtheories), for example. The ex- planatory hypotheses relate to each other in a discontinuous manner: in certain circumstances of time and space they be- come stronger; in others, they are interdependent or mutually excluding. In certain contexts, it would be possible to reverse the causal relation and point to incarceration as a factor that triggers the growth of crime rates and the toughening of pri- mary criminalization (criminal laws) and secondary (the atti- tude of the actors of the criminal justice system). The second defiancegoes on this difficulty to propose a uni- versal explanation as to the different geopolitical context of the processes of incarceration and the impact of different manage- ment punitive policies that criminalized poverty in the countries of peripheral capitalism, notably in Latin America. One may note, for example, that completely different results are obtained by comparing incarceration numbers of Brazil with other South American countries (particularly Argentina) and with other leading economies (BRICs). This means that the trans national criminal policy adapts to regional characteristics (central and peripheral), increasing or decreasing its lethality according to each culture’s level of resistance to punishment. Similarly, it is possible to understand the difficulty in determining the factors Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 7  S. CARVALHO regarding the national culture that decisively impact increasing incarceration. Incidentally, faced with a plurality of factors, the suggestion is that incarceration stems from a dense and com- plex network of variables, which greatly reduces the theoretical expectations of an idealistic slant towards the development of a universal explanatory model. In the Brazilian case, the reinvention of prison undeniably acquires an instrumental role in the new conception of capital- ism. However, unlike other Latin American countries, the vul- nerability to incarceration affects very specific groups i.e., the target groups identified as misfits needing to be neutralized— and have an unique characteristic normally associated with the labels assigned to the black, poor and marginalized youth, linked, either directly or indirectly, to the unlawful drug traf- ficking of urban outskirts (war on drugs). Moreover, it is also possible to argue that, in the Brazilian experience, punishment never abandoned a latent function of violently controlling dangerous and inconvenient individuals and groups, even in the times of (formal) correctionalism. Nowadays, with the abandonment of the (material) penal-wel- fare policies and the new meaning given to prison as a mecha- nism of exclusion and control, institutional violence reaches indecent levels. The perverse equation that adds the historical omission of integrative social policies with the active interven- tion of increasing the chances of (primary and secondary) criminalization results in brutal spaces of incarceration—i.e., brutal prisons, completely inappropriate for the rehabilitation programs disclosed by official agencies; hazardous places that, due to the lack of investments, do not provide even the minimal living conditions for inmates in prisons, asylums and youth detention cen te rs. The third defiance relates to the emergence of new discourses of justification and legitimation of punishment (New Penology) in the new political order. New Penology emerges at the same time as the punitive policies of the Penal State. Thus, the macro-level criminology hypothesis (paradigm of social con- struction) and the diagnosis of incarceration as a result of the new managerial criminal policies seem to go together. Rather, it can be said that this new discourse is the unfolding of the criminal policies created by the PenalState. The perception of the expansion of incarceration as a result of an economic and political model that needs to transform flawed consumers by neutralizing them into ghettos is not a statement opposite to the theses of actuarial justification of punishment. Notoccasionally these flawed consumers are identified as risk groups. Thus, the propositions do not seem divergent but complementary in the interpretation of the new geopolitics of confinement. The control and neutralization of risk groups are rhetorical structural elements in building a punitive culture as they easily converse with common sense (punitive populism), and obtain the sanctioning of punishments and prisons as a result. Thus, if the paradigm of social construction exposes the macro-level political movement of the punitive power, the New Penology defines the assumptions of the political-criminal frequency and presents a new theoretical hypothesis (theory of justification of punishment). The convergence of the macro-level criminology explanation (Penal State) with the criminal-political perspective (New Pe- nology) also makes it possible to draw some hypotheses to be worked out. First, the New Penology turns criminology into an empty space of critical theoretical analysis of the phenomena of crime and criminalization, turning it into a mere public safety management tool (by both right and left wing governments)5; second, the New Penology enters the field of bio political con- trol of the population by operating under the actuarial control of dangerous groups. The fourth defianceaims at bringing critical criminology from the foucauldian critique of prison as adisciplinary institu- tion (Discipline & Punish, 1975) and update it to the bio poli- tics perspective (History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge, 1976). Foucault’s critique of the prison has a precise delimita- tion of time: it is directed at the prison inserted into the correc- tional logic of industrial capitalism. The appropriation of the theses brought forth in Discipline and Punish by critical crimi- nology made it possible to uncover the correctional discourse, especially when it opposed the official duties borne by the theories of positive special prevention (rehabilitation of the convict) to the actual functions performed by the institutional power. However, despite this hypothesis being extremely useful to strengthen the critic to correctionalism, nowadays the idea of disciplining through confinement cannot be shared in an un- critical manner. As previously stated, intervention policies cor- roded with the welfare state crisis, which led to the collapse of the positive special prevention model. Moreover, in the geopo- litical and economic reconfiguration of globalized capitalism of the 21st century, prisons do not perform the same penal-welfare functions. This means that they essentially cannot be construed as disciplinary spaces. Vera Batista argues that neoliberal policies have brought the penal system to the center of the political activity: “Prison has not lost its meaning (...), the particular aspect of neoliberalism was to combine the penal system with new control and surveil- lance technologies, turning the world’s poor neighborhoods into concentration camps” (Batista, 2011: 99). Therefore, the question to be addressed is not how to adapt the Foucauldian idea of discipline in the new criminal geopo- litical order, but to notice how the disciplines that founded great institutions of social control (prison, school) are nowadays part of a complex network of political administration of bodies and a rational management of life. In this respect, it is important to realize that Foucault sees two main forms of exercise of power over life that are intertwined. Two poles that are not antithetical. The first forms around the body as a machine and projects the necessity of its training (correctionalist hypothesis). However, parallel to the idea of disciplining, Foucault refers to a second pole, focused on the body as species body (population) and its biological processes (proliferation, fertility, mortality, health, longevity, for example). The second form of intervention aims at regulatory controls and is incorporated as a biopolitics of the population. Thus, “the disciplines of the body and the regula- tions of the population are the two poles around which the or- ganization of power over life was developed (...)” (Foucault, 1988: 152). The connection between the disciplines and biopolitics, i.e., the exercise of power over the body as a machine and the body as species body can be seen in contemporary punitive policies. It is interesting to see how, despite the crisis, some correctional practices remain active in control devices, maintaining a mini- mum of residue discipline. In this respect, despite prison being 5Vera Batista (2011) demonstrates exactly how part of the left was seduced b y managerialism, a situation that shows how some critical criminologists were incorporated into the structuresof power and began to collaborate with the governing of the State Criminal. 5 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 8  S. CARVALHO increasingly identified as an area of neutralization and refrain- ing, it is possible to note the maintenance of some correctional- ist procedures. And this happens not only to maintain some resemblance of social utility or of a certain humanitarian foun- dation for criminal punishment, but especially to make sure certain control techniques are still being used. In this scenario, the criminological reports and administrative disciplinary pro- cedures (disciplinary sanctions) are highly functional for the surveillance of the prisoner, delaying his/her departure from the institution or controlling his/her return to freedom. Parallel to the body as a machine control, the prison ap- proach goes beyond the boundaries of the prison and becomes a part of daily life as (or through) the public safety policies. As previously highlighted, management and actuarial punitive control, sanctioned by the New Penology, appear to be “the great political-criminal novelty” in the age of great confine- ment. The objectives of identifying and managing potentially criminal risk groups are the parameters that govern this prison procedure that becomes a part of the life of the non-incarcerated population. The technocratic control network enables therefore not only keep the convict who served his/her sentence under surveillance, but also identifies individuals or risk groups (po- tential criminal offenders—social dangerousness) and develops neutralizing actions that imply his/her segregation. As de- scribed by Foucault, this is a large and complex network, and brings together a number of government agencies, i.e., it is not limited to traditional punitive policies. For no other reason, the concept and public safety policies nowadays seem to have a high power of attraction, becoming a path for the main political actions. This is a key concept in the instrumentalization of management policies. In the theoretical field, the bio political concentration of punitive procedures in the idea of public safety causes a depletion of criminology—if understood as a field of knowledge focused on critical reflec- tive thinking and punitive practices (critical criminology). Critical reflection and the exposure of institutional violence are replaced by a very clear guideline: drafting actuarial analysis projects or management programs and crime control (technoc- racy). The experi ences of the contemporary emphasis on safety management—shared by right or left wing political trends— halt any possibilities of thinking concrete alternatives or models that overcome the prison-focused approach because the funda- mentals of punitive culture are not seen as a problem and their premises are naturalized. The fifth defiance exposes the central problem of this paper: what is the role of penal dogmatic theory when faced with the phenomenon of great confinement? Or, Even: How Punishment Justification Theories Explain Mass Incarceration? The justifi- cation of punishment is one of the pillars of dogmatic dis- courses. In many systems, the fundamentals of (dogmatic) criminal science are all about theories of punishment. The form of justification of punishment sets, in most cases, 1) the princi- ples of interpretation of the criminal law (criminal law theory), 2) the criteria of imputation and premises of criminal liability (tort theory) and 3) the instrumentalization (implementation and execution) of the legal response to crime (theory of punish- ment). Thus, it seems imperative to confront the dogmatic penal theory with the problems that have been exposed by critical criminology in recent decades; questioning legal criminal sci- ence to manifest about the reality it c r e a t e s i t s theories upon. Punishment Theories and Mass Incarceration: A Criminological Questioning to Criminal Law (Justification) Punishment theories—characterized by the doctrine of criminal law in a normative arena—seek to answer the question why punish? It is, therefore, according to the crite- ria for defining the horizons (and limits) of legal research (epistemological problem) a question regarding the philosophi- cal foundations of criminal law. Ferrajoli’s (1998) answer to the question why discipline? can be understood in two different ways: 1) why is there punishment? or why should one punish? and 2) why should there be a penalty? or why should one pun- ish? The first would be a scientific problem that admits only empirical answers to verifiable and disputable (true or false) assertions. The second sense of the matter would reveal a phi- losophical problem that admits only political and ethical an- swers thought according to normative propositions, neither true nor false, but only acceptable and unacceptable as fair or unfair. In other words, Ferrajoli understands that the first question is sustained on the existence of the phenomenon punishment, or of punishment itself as a fact that translates problems of a his- torical or sociological (criminological, above all) perspective. The second question reveals the should be legal aspect of pun- ishment, i.e., the right to punish, which refers to the prescriptive normative aspects. The (neo)positive epistemological model in criminal science divides the problem into two: criminology would have the task to reflect upon the empirical phenomenon of punishment, and criminal law would be left with the task of the legal duty of punishment. In this framework, criticism that empirically dis- regards the normative theories and vice versa would be un- thinkable. The stiff demarcation of the boundaries of criminal and criminological knowledge thus produces two absolutely inde- pendent fields, two distinct scientific universes, with methods, objects and language of their own, despite dealing with the same problem: punishment. The impossibility to cross penal and criminological knowledge stems from the idea according to which one cannot achieve moral or prescriptive conclusions based on factual or descriptive elements. The positive interdic- tion of the possibility of deriving value from objective facts determines that a normative perspective cannot come from positive perspective, and, on the contrary, that a positive per- spective cannot come from a normative one (Hume’s Law). The transposition of Hume's Law to criminal science pre- vents, for example, that criminological critique based on em- pirical data of the phenomenological reality of punishment annuls normative premises or dogmatic foundations of punish- ment. Thus, the valid critical levels would be only those estab- lished in their own area of competence: dogmatic critical theo- ries to criminal law and critical criminology theories to crimi- nology. In the deepening of the boundaries between criminal law and criminology, in specific terms, and between law and sociology, in general terms, Ferrajoli (1998) states that responses to the problem of punishment (to the question why punish?) based on the confrontation between its function (historical or sociologi- cal descriptive use) or its motivation (legal descriptive use) and its purpose (axiological normative use) stem from a methodo- logical addiction, or even, that such responses that do not dif- ferentiate positive aspects (in fact or according to the law) from the (axiological) normative aspects of punishment. The meth- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 9  S. CARVALHO odological error would be clear in the use of an explanation as justification or vice versa. The doctrines and theories that over- lap justification models to the schemes of explanation and the theories that mix the normative aspects and the positive aspects (of punishment) would violate Hume’s Law and reveal a fun- damentally ideological character. The epistemological positive pattern in criminal sciences, brought forth in the legal dogmatism and in the criminological orthodoxy, therefore limits the understanding and the critique of the foundations of criminal law to the exclusively normative sphere. The prohibition is expressed: reality is constituted as another problem, something autonomous, independent. In this context, the legal-criminal science philosopher should adopt a system of understanding (criminal law or criminology), and based on the premises and foundational principles of that specific field, guide his/her discussion based over the funda- mentals and the validity of the questioning hypotheses. The separation from the positive asepsis and its subsequent withdrawal in confronting the phenomena of everyday life— Especially in a field of knowledge marked by the radicalism of individual and institutional violence—Happens upon the emer- gence of the critical theory of (Criminal) law and, in particular, critical criminology. In the field of punishment, critical crimi- nology highlighted the deep discrepancy between the official discourses developed by the theories of justification (normative theories) and the effectively exercised functions of the punish- ment agencies (phenomenological experience). Despite the never-ending resistance, the confrontation between the criminal theories with the reality of the criminal punitive system made the process of recognition of criminological knowledge by dogmatic irreversible. Critical criminology repealed Hume’s Law from criminal sciences, allowing the empirical knowledge about the reality of the criminal control agencies to serve as a tool of deconstruc- tion, modification and implementation of dogmatic knowledge. Critical criminology as a critique of criminal law was devel- oped in this line of thought in Western countries of the Roman and Germanic legal tradition. Based on this critical perspective, Muñoz Conde and Hasse- mer state that “the importance to prevent blindness towards reality that often has legal regulation, the normative knowledge, i.e. the legal aspect, should always go together, be supported and illustrated by empirical knowledge, i.e. by knowing reality (...)”. (Hassemer & Conde, 2008: 05) However, as the authors note, “the relation between empirical knowledge and normative knowledge, according to how each of them approach reality, is not, nevertheless, idyllic, but a conflicting one and one with many points of contact, where sometimes the normative and the empirical knowledge clash regarding the solution given by the other part and it is not uncommon that sometimes this is a cause of dysfunction and inefficiency of the criminal-legal standards in solving conflicts or that even that empirical knowledge itself lacks influence in the regulation of a specific legal problem”. (Hassemer & Conde, 2008: 06) Vera Batista, cautious of the warnings given by Zaffaroni, seems to precisely understand the problem: “punishment can not be thought ac- cording to normative theories, but according to the lethal real- ity of our concrete penal systems” (Batista, 2011: 91). In this aspect, this paper explicitly assumes the ideological addiction (pejoratively) described by Ferrajoli. The choice for the critical criminological perspective makes it possible to leave Hume’s Law behind on behalf of an effective concern for the lives of people who suffer in the gaps created by the grand nar- ratives of theoretical justification of punishment and the real experience of punitive distress. For no other reason does Zaf- faroni bring forth a system of understanding criminal law with the aim of limiting the punitive power and built on its empirical data (Zaffaroni, Alagia, & Slokar, 2006: 77). Geraldo Prado shows that, giving context to the methodo- logical dispute between causalism and finalism, the bearers of the official scientific capital in criminal law rarely base their investigations on the contradictions of everyday performance of the repressive apparatus, and not invariably, develop compre- hensive schemes “disregarding the consequences produced by adopting one or another way to interpret/apply the criminal law. (...) Positivism [according to the author] annuls the his- toricist aspect of the social sciences” (Prado, 2011:30). Ac- cording to Michel Löwy’s interpretation, the effort of positive thinking of achieving objectivity, freeing up from the ethical, social or political assumptions, “is a feat that irresistibly brings to mind the famous story of Baron Munchausen, this pictur- esque hero who manages, through a genius stroke, to escape from the swamp where he and his horse were being dragged by pulling himself by the hair... Those who claim to be truly objec- tive beings are simply those who carry their assumptions more deeply” (Lowy, 1994: 32). The purpose of this paper is to present Brazilian data regard- ing incarceration in the last decades as premises with serious ethical, social and political implications, and therefore explic- itly inquire about the necessary relationship between the (nor- mative philosophical) justification theories of punishment and the (empirical) phenomena of the great incarceration. The ques- tion behind the current reflection is the role that punishment theories play in the expansion or contraction of the power to punish (potestas puniendi). The question that pervades the text is about what are the possible explanations that the punishment theories would offer to the problem of hiper-punishment. The theoretical exercise based on empirical criminalization data seeks to reverse the question traditional punishment theo- ries seek to answer. Instead of questioning the criminal law theory why punish? (why should there be punishment?) the goal here is to question how criminal dogmatic justifies the concrete punitive system it sanctions. It is, undeniably, a theo- retical questioning: if the penal doctrine, especially in the last two centuries, made a huge effort to assign a positive meaning to the existence of punishment, the proposal is to subvert the apparently logical premises made since the positive era. The goal here is not to simply question a normative system of justi- fication that will be later verified or discredited in real life by criminology, but to have the penal doctrine explain, with its sophisticated theoretical resources, the contemporary phe- nomenon of mass incarceration. The defiance is justified by the urgent need for the criminal law theory to take on some ethical and social responsibility, i.e. one that does not evade reality and, in particular, the effects its legitimacy models produce. Based on Bourdieu, Geraldo Prado argues that it is necessary to escape the narcotic temptations of the “pure science” per- spective (unrelated to social needs) on one hand and the “sci- ence as a slave” perspective (subject to political and economic demands) on the other. This is exactly why he takes on the starting points not as data but as constructions. In criminal law, one of the key elements will be that of the offense—“penal theories emerged in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 10  S. CARVALHO sanction the operation of the criminal justice system, according to the discourse of modernity, not questioning straight from the beginning one of its key elements, the offense, something con- sidered a social element and not a creation of the political power itself” (Prado, 2011: 26). But if criminal law assumes offense to be a social element (and not a political construct), it shall think of punishment as such as well, for the criminal sanction represents the natural consequence of wrongdoing in this orthodox model. Crime and punishment, understood by criminal dogmatic as natural phe- nomena—and criminology will add the third element of the natural criminal to this equation—are free from any prior ques- tioning. Criminal law would be only entitled to establish the assumptions of attribution and accountability (theory of crime) and the justification for the execution of the sentence (theory of punishment). Those responsible for the theory would only per- form an exclusively instrumental task of justifying the use of the categories; they would be free from the debate on the sub- stance and effect of their technique. When confronted with the questioning over the grounds of their theories (punishment theories), they refrain from the question about its necessity and impacts on reality. However, faced by the blatant failure of the empirical phe- nomenon of punishment and the outright disregard of the theo- retical justifications for punishment, it seems crucial to question how does criminal law justifies or, at least, explains the massive incarceration that marks the first decades of the twenty-first century. Conclusion The paper sought to present problems considered to be cen- tral to the theme that involves punitive social control in con- temporary times: First, the steady increasing number of incar- cerated people, especially in the west, with special focus on the Brazilian case. Second, the form of interpretation of the crimi- nological phenomenon of incarceration. Third, the existing gap in criminal law theory concerning the reality of the great con- finement. Criminological theories, even the most orthodox ones, have demonstrated the importance of thinking about the theme. Thus, despite the numerous and dichotomous responses to the prob- lem, criminology—especially penology—has shown intense concern in analyzing the reality of world incarceration, sug- gesting some explanatory hypotheses and proposing alterna- tives. From the empirical problem of prisons, different trends of thought have presented new criminological theories of legiti- macy or illegitimacy, in models that are not limited to the de- scription, but have justified or deconstructed punishment. The (dogmatic) science of criminal law, cloistered in the positive paradigm, justifies its omission based on the require- ments summarized in Hume’s Law. Thus, it limits itself to the proposition of normative theories of justification, preventing the empirical reality of the system on which it operates being debated. But the experience of mass incarceration turns this silence into a loud noise. The paper, besides reporting the prison situation in Brazil, sought to defy the traditional theories of criminal law, by re- versing the dogmatic logic and the traditional penal sci- ence—specifically the punishment theories—in order to explain the phenomenon of incarceration. In very simple terms, the research problem could be summarized in the following ques- tion: What do theories of punishment have to say about the mass incar ceration? In fact, the question here seeks to convene punishment theo- ries to make an ethical reflection, posing a critical judgment about its functionality (instrumentality) and its social (ir)res- ponsibility. The questions, which go beyond idealism, are: first, how does criminal law face the problem of actual incarceration, since it is a direct consequence of the punishment discourse? Second, what are the alternatives proposed by criminal law to the phenomenon of mass incarceration, considering that this strategy is not getting the expected results of reducing crime rates, on the contrary, the system ends up creating even more violence (crime-prison-strengthening of criminal identity- crime-prison)? And as a result, the third question is: is it rea- sonable to propose more incarceration as an alternative to the punishment crises? At this stage of the criminal sciences, especially after the ir- reversibility of deconstruction performed by critical criminol- ogy, it seems that it is no longer possible that a theoretical model justifies punishment in an abstract manner without wor- rying about the impact that this justification produces on the reality of the criminal justice system. Otherwise, by choosing to keep silent, criminal law theory will completely lose its ability to (self-)criticize; seduced by the will to be pure, it will remain as a slave science, an innocent technique useful to political demands. REFERENCES Anistia Internacional (1993). Chegou a morte: Massacre na “Casa de Detenção” de São Paulo. São Paulo: Seção Brasileira da Anistia Internacional (Amnesty International, Massacre in the São Paulo Detention House). Anistia Internacional (1999). Aqui Ninguém Dorme Sossegado: Violações dos Direitos Humanos contra Detentos. São Paulo: Seção Brasileira da Anistia Internacional (Amnesty International, Violation against Prisoner’s Human Rights). Associação Dos Magistrados Brasileiros (2006). Pesquisa AMB. Brasília: AMB (Brazilian Judges Associat i on, Research). Azevedo, R. G. (2009). Justiça penal e segurança pública no Brasil: Causas e consequências da demanda punitiva in revista brasileira de segurança pública, 03, 04 (Criminal Justice and Public Safety in Brazil: Causes and Consequences of the Punitive Demand). Azevedo, R. (2005). Perfil socioprofissional e concepções de política criminal do ministério público gaúcho. Porto Alegre; MPRS (Socio-Professional Profile and Conceptions of Criminal Policy among prosecutors in th e s ta te of Rio Grande do Sul). Baratta, A. (1997). Criminologia crítica e crítica do direito penal: Introdução à sociologia do direito penal. Rio de Janeiro: Revan (Critical Criminology and a Critique of Criminal Law: An Introduc- tion to the Sociology of Criminal Law). Batista, V. (2011). Introdução crítica à criminologia brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Revan (C ritical Introduction do Brazili a n Criminlogy). Bauman, Z. (1999). Globalização: As Conseqüências Humanas. São Paulo: Jorge Zahar (Globalization: The Hu m an Consequences). Bitencourt, C. (1993). Falência da pena de Prisão. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais (The Brankruptcy of Custodia l Sentences). Blomberg, T. G., & Lucken, K. (2009). American penology: A history of control. London: Aldine Transaction. Brown, M. (2006). The new penology in a critical context. In W. S. Dekeseredy, & B. Perry, (Eds.), Advancing Critical Criminology: Theory and Application (Critical Perspectives on Crime and Inequal- ity). Lexington: L exington Books. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Departament of Justice (2007). Prisioners in 2006. Washington: Office Press. Câmara dos Deputados (2009). CPI do sistema carcerário. Brasília; Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 11  S. CARVALHO Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 12 Edições Câmara (House of Representatives, Parliamentary Commis- sion of Inquiry about the Prison System). Carvalho, S. (2010). O papel dos atores do sistema penal na era do punitivismo. Rio de Janeiro: Lumen Juris (The Role of the Actors of the Penal System in the Age of the Punitive Trend). Carvalho, S. (2007). A política criminal de drogas no Brasil: Estudo criminológico e dogmático (4th ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Lumen Juris (The Criminal Drug Policy in Brazil: A criminological and dogmatic approach). Confederação Nacional dos Bispos do Brasil (1997). A fraternidade e os encarcerados. Campinas: CnBB (National Bishops Association of Brazil, Brotherhood among Inmates). Departamento Penitenciário Nacional (2008). Evolução histórica das penas e medidas alternativas (PMAS). no Brasil. Brasília: MJ (Na- tional Penitentiary Department, Historical Evolution of Diversion Programs in Brazil). Departamento Penitenciário Nacional (2008). Histórico do programa nacional de penas e medidas alternativas. Brasília: MJ (National Penitentiary Department, A History of the National Diversion Pro- grams). Departamento Penitenciário Nacional (2012). Censo penitenciário naci- onal. Brasília: Depen (National Penitentiary Department, National Prison Census). Feeley, M. M., & Simon, J. (2005). The new penology. In E. McLaugh- lim, J. Muncie, & G. Hughes, (Eds.), Criminological Perspectives: Essential Readings (2nd. Ed). London: Sage. Ferrajoli, L. (1998). Diritto e ragione: Teoria del garantismo penale (5th ed.). Roma: Laterza. Foucault, M. (1988). História da sexualidade: A vontade de saber. Rio de Janeiro: Graal (History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge). Fragoso, H. C., Catão, Y., & Sussekind, E. (1980). Direitos dos presos: Os problemas de um mundo sem lei. Rio de Janeiro: Forense (Pris- oner’s Rights: The Problems of a World without Law s ). Garland, D. (2004). Penal modernism and postmodernism. In Punish- ment and Social Control. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Garland, D. (2001). The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporar y society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hassemer, W. (1994). Segurança pública no estado de direito in revista da Ajuris, ano XXI, 62, Porto Alegre (Public Safety in the Democ- ratic State). Hassemer, W., & Muñoz Conde, F. (2008). Introdução à criminologia. Rio de Janeiro: Lumen Juris (Introduction to Criminology). Human Rights Watch (1998). O Brasil atrás das grades. Nova Iorque: HRW Americas (Brazil Behind Bars). Instituto Brasileiro De Ciências Criminais (2007). Visões de política criminal entre operadores da justiça criminal de São Paulo: Relatório de Pesquisa. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais (Criminal Policy Views among Operators of the Justice System). Instituto Latino-Americano das Nações Unicas para Prevenção do Delito e Tratamento do Delinquente (2005). Levantamento nacional sobre execução de penas alternativas. São Paulo: Ilanud (National Report on Diversion Prog r a ms). International Centre for Prison Studies (2012). World prison brief. http://www.prisonstudies.org/ Larrauri, E. (2009). La economia política del castigo in revista electrónica de ciência penal y criminologia (RECPC). 11, 06. Lemos, C. (2011). Política criminal no Brasil neoliberal. Dissertação apresentada no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Direito da UERJ. Rio de Janeiro (Criminal Policy in Neo Liberal Brazil). Lowy, M. (1994). As aventuras de Karl Marx contra o Barão de Münchhausen (5th ed.). São Paulo: Cortez (Karl Marx's Adventures against the Baron Münchhausen). Pavarini, M. (2009). El Grotesco de la penología contemporânea in revista Brasileira de ciências criminais (Vol. 81). São Paulo. Prado, G. (2011). Campo jurídico e capital científico. Ensaio apre- sentado no departamento de história das ideias da Universidade de Coimbra. Coimbra (Legal field and scientific capital). Thompson, A. (1991). A questão penitenciária (3rd ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Forense (The prison matter). Wacquant, L. (2001). As prisões da miséria. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar (Prisons of poverty). Wacquant, L. (2009). O corpo, o gueto e o estado penal in sinal de menos (Commodifying bodies). Wacquant, L. (2008). O lugar da prisão na nova administração da pobreza in dossiê segurança pública, novos estudos CEBRAP, São Paulo (Prison in th e new management of poverty ). Wacquant, L. (2001). Punir os pobres. Rio de Janeiro: Freitas Bas- tos (Punishing the poor: The neoliberal government of social insecu- rity). Wacquant, L. (2004). O que é gueto? In revista de sociologia e política, curitiba (What is a ghetto?). Wilson, J. Q. (2005). On deterrence. In E. McLaughlim J. Muncie, & G. Hughes, (Eds.), Criminological Perspectives: Essential Readings. London: Sage. Zaffaroni, E. R., Alagia, A., & Slokar, A. (2006). Manual de derecho penal (2nd ed.). Bu en os A ires: Ediar (Handbook o f Cr iminal Law). |