Advances in Journalism and Communication 2013. Vol.1, No.3, 19-25 Published Online September 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajc) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2013.13003 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 19 Pulling the Plug on Grandma: Obama’s Health Care Pitch, Media Coverage & Public Opinion Shahira Fahmy1*, Christopher J. McKinley2, Christine R. Filer3, Paul J. Wright4 1School of Journalism, College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA 2Department of Communication Studies, Montclair State University, Montclair, USA 3Department of Communication, College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA 4Department of Telecommunications, Indiana University, Bloomington, USA Email: *sfahmy@email.arizona.edu Received June 8th, 2013; revised July 8th, 2013; accepted July 16th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Shahira Fahmy et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This study examined the agenda-building process, in which interpretive frames activated and spread from the top level through the news media to the public, in the context of Obama’s controversial health care reform. The authors examined the relationship among media coverage, presidential rhetoric and public opinion from President Obama’s inauguration in January 2009 to the date the “Patient Protection and Af- fordable Care Act” was signed into law in 2010. Results indicate the media were modestly successful at building the media agenda. However, results also showed that presidential rhetoric might have influenced public opinion. Limitations and suggestions for future research are discussed. Keywords: Agenda-Building; Health Care Reform; News Media; Public Opinion; Obamacare; The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Pulling the Plug on Grandma: Obama’s Health Care Pitch, Media Coverage & Public Opinion With growing unease over the trillions of dollars being spent on bailouts and economic stimulus on top of an already unpre- cedented level of debt, President Obama signed into law a his- toric health care overhaul that according to him “won’t pull the plug on grandma.” In March 2010, the President signed The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA). Contro- versies over the Obama’s health care reform emerged in public discourse however. The reform faced near unanimous oppose- tion from Republicans and a serious divide among Democrats and the American public. The failure among Democrats to sup- port Obamacare, intense Republican attacks against the issue, and sagging poll numbers pushed the President to address Con- gress specifically to fix the nation’s ailing health care system. As the President pitched to sell the country on the need to reform health care, coverage of the debate became widespread. Media outlets often had a tendency to frame the issue in terms of economic controversy, such as framing the issue as an eco- nomic necessity or as a bad economic policy. As a result, the way the President and the media framed the debate may have influenced the way the public understood, evaluated, and sup- ported Obamacare. This study uses the signing of the PPACA law to explore how interpretive frames activate and spread from public offi- cials through the news media to the public (Entman, 2003). While numerous studies have examined who sets the media agenda (Gandy, 1982; Wanta, Stephenson, Turk, & McCombs, 1989) less attention has been paid to investigating the influence of important news sources on health care reform. In fact, re- garding issues where health care and politics intersect, research examining agenda-building of health care reform appears to be scarce. Guided by agenda-building research, the current re- search focuses on the health care debate by examining the rela- tionship among media coverage, presidential rhetoric, and pub- lic opinion starting with President Obama’s inauguration in Ja- nuary 2009 to the date the PPACA was signed into law in March 2010. The Health Care Debate Obama placed health care reform on his agenda long before entering the White House. One month before Election Day, he chose to give a speech in Virginia focusing on health care re- form.1 He stated, “The real solution is to take on drug and in- surance companies; modernize our health care system for the twenty-first century; reduce costs for families and businesses; and finally provide affordable, accessible health care for every American. And that’s what I intend to do as President of the United States” (Obama, 2008). It should be noted that after winning the 2008 presidential election, Obama continued to cite health care reform as a priority (Obama, 2009). Over a year of debate followed Obama’s inauguration, as re- forming health care proved to be an arduous process. Govern- ment officials discussed not only what should be included in the health care plan, but also whether the federal government had the power to require that each citizen purchase health care. 1Obama focused on health care reform rather than the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, or the U.S. bank bailout law, which was passed merely a day prior. *Corresponding author.  S. FAHMY ET AL. Extensive media coverage followed the debate. Rather than attempt to explain what the proposed health care reform plans might mean for the average citizen, most news coverage fo- cused on controversial issues such as death panels and the eco- nomic implications of overhauling health care. With proposed plans costing anywhere from $750,000 to $1 trillion, much of the debate concerned the national debt and the financial effects of an expensive health care bill. At the same time, others argued for the economic benefits of extending health insurance coverage to millions of people. Some of the narrower financial issues discussed included cutting medicare, creating a public option plan, and making deals with pharma- ceutical companies (Holan, 2009; Klein, 2009, Health insurance reform and medicare: Making medicare stronger for America’s seniors, 2012). Coverage of the debate was also fueled by bipartisan divide. The media publicized intergovernmental disagreement over health care reform legislation along party lines, as well as rare instances of Republicans supporting the legislation and De- mocrats opposing it. Experts on health care, insurance industry executives, and task groups assigned to drafting legislation were cited in the news as they provided their opinions on not only the proposed plans but also the process of passing health care reform. Obama was often referenced throughout the debate, both championing support for legislation and recognizing ob- stacles faced in passing it. On November 7, 2009, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 3962, colloquially referred to as the Affordable Health Care for America Act. The Senate then passed H.R. 3590, or the PPACA, on December 24, 2009. Building upon the PPACA, Obama released his proposal on February 22, 2010. The PPACA (H.R. 3590) passed in the House on March 21 and was signed into law by Obama on March 23, 2010. Theoretical Framework: Agenda Building This study examines the agenda-building framework from the perspective of the reciprocal relationship among presiden- tial rhetoric, media coverage, and public opinion (Lang & Lang, 1983). It approaches the Obamacare debate as a form of politi- cal discourse controlled by competing perspectives toward the issue by examining the interaction among these three different variables through which different agendas are discerned (Fah- my, Wanta, Johnson & Zhang, 2011; Johnson & Wanta, 1996; Lang & Lang, 1983; Wanta & Kalyango, 2007). A review of the literature indicates other agenda-building studies have focused on this cyclical process involving a similar reciprocal agenda-building relationship. For example, Lang and Lang (1983) examined the relationship between the press and public opinion during the Watergate era. They found a cyclical three-way relationship among the press, the public, and the presidency, suggesting that more complicated issues go through the process of agenda-building. Johnson and Wanta (1996) examined the relationship among the public, the media, and the Nixon administration regarding the war on drugs. They found that real-world events set into motion the agenda-building process. This drove news media to increase their coverage of the issue that, in turn, led to the pub- lic learning of the importance of drugs as a major issue. Finally, the President reacted to public’s concern. Recently, Fahmy and colleagues (2011) examined the inter- action among the President, the media, and the public for an event that was not considered an existing “real-world” condi- tion. They found evidence that President Bush influenced me- dia coverage of the Iraq War, supporting the notion that news values and journalistic norms have traditionally placed a priori- ty on gathering information from authoritative and official sour- ces (Ragas, 2012). These studies and others adopting the cyclical process ap- proach of agenda-building have traditionally been guided by the use of public opinion polls and content analyses of media frames as well as frames used by the presidency (i.e. analyzing weekly compilation of presidential documents) (Fahmy, Wanta, Johnson, & Zhang, 2011; Wanta & Kalyango, 2007). Framing is the process of selecting, emphasizing, and inter- preting of a situation to promote a particular interpretation of an issue or event (Entman, 1993). Using content analysis to look at framing in media coverage and presidential rhetoric has been validated across studies. In the case of presidential rhetoric, numerous studies have indicated that the U.S. President is the nation’s first news source that gets cited regularly by the news media (Adams & Cozma, 2012; Fahmy, Relly, & Wanta, 2010; Fahmy, Wanta, Johnson, & Zhang, 2011; Wanta & Foote, 1994). Regarding content analysis, Borah (2011) found that the majority of framing research in the past decade consisted of content analyzing media coverage. Therefore, understanding the use of framing by the news media and the president, offers us an understanding of how competing views of Obamacare might have used the media to build a frame of coverage in ways that would create support for their cause. For example, Conway (2012) examined second- level agenda setting effects of six news outlets on public opi- nion about the health care reform bill proposed by President Obama. Her analysis revealed that cumulative affective attri- bute salience in the media was a significant predictor of support in public opinion polls (Adams & Cozma, 2012). Within the context of this study, government sources (in- cluding President Obama) could have carefully chosen strate- gies to build the agenda for public discourse regarding Obama- care over time. This would have allowed the diffusion of pre- ferred frames and policies to dominate the U.S. media, and the mobilization of the public toward support for health care reform advocated by the White House. The impact would have been substantial simply because how an issue is framed by public officials and the media comprise the principle arena within which controversial issues come to the attention of policy ma- kers and the public. For example, Adams and Cozma (2012) found that Obama was the top news source in newspaper stories covering the health care reform. While this study offered an in-depth investigation of sources and specific types of media frames addressing health care reform, it did not examine tone of coverage, presidential documents and/or compare them to pub- lic opinion. Thus, it remains unclear whether this particular issue supports the traditional perspective on agenda-building. Furthermore, historically within the processes of frame- building and agenda-building, competing sources have operated as news sources to provide strategic information to the media (Lambert & Wu, 2011; Wu & Lambert, 2010). For example, Wu and Lambert (2010) found that government sources were relied on the most in news coverage of the health care debate, and that public opinion toward Republicans and Democrats trended downward, a finding traced to these sources being used more frequently in media. While that study in many ways mir- rors this investigation, the current study applies a more com- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 20  S. FAHMY ET AL. prehensive assessment of the links among presidential rhetoric, media coverage, and public opinion. It adapts from Robert Entman’s (2003) cascading activation model that explains how interpretive frames activate and spread from the top level of a stratified system (the White House) to the network of non ad- ministration elites, and on to news organizations, their texts, and the public. Thus, by focusing on tracing the diffusion of frames by the White House (President Obama) and media cove- rage, the current study hopes to add to agenda-building litera- ture by exploring how interpretive frames might have activated and spread from the top level in the context of one of the most controversial national health care policies. Method The news sources sampled in this study included news arti- cles and opinion pieces published between January 20, 2009 and March 23, 2010 in The New York Times, LA Times, Chi- cago Tribune, and The Washington Post. These newspapers were selected based on their influence and prestige. The litera- ture suggests national coverage of news tends to follow the elite media (Bennett, 1990; Fahmy, Wanta, Johnson, & Zhang, 2011; Nisbet & Lewenstein, 2002). Therefore, as newspapers of re- cord (that have knowledgeable news professionals) these four elite major metropolitan publications tend to set the news agen- da for regional news organizations. The time frame analyzed represents Obama’s inauguration (January 20, 2009) and the date the PPACA was signed into law. Coverage containing both “Health Care” and “Obama” anywhere in the text was retained (N = 2856: The Chicago Tribune = 1146; The Washington Post = 746; The New York Times = 743; The LA Times = 221). Fifteen percent of the arti- cles including these terms and relating to health care reform were then randomly selected from each paper’s pool, resulting in a final sample size of 428 articles. Of the 428 articles sam- pled, 40.2 percent (n = 172) were selected from the Chicago Tribune, 26.2 percent (n = 112) from The Washington Post, 25.9% (n = 111) from The New York Times, and 7.7 percent (n = 33) from the LA Times. Weekly presidential compilation documents were also ex- amined. The documents were downloaded from the U.S. Go- vernment Printing Office’s Federal Digital System, which has electronic versions of the White House Press Secretary’s offi- cial publications available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collection.action?collectionC ode=CPD. To be included in our analysis, each document had to be published between inauguration and bill passage and con- tain both “Health Care” and “Obama”. These initial require- ments yielded 26 documents. Of these documents the ones that did not mention Obamacare or health care reform were ex- cluded from the sample, leaving 17 documents to be analyzed.2 Coding Categories Each article was coded for the content categories described below, while each presidential document was only coded for focus and tone. The weekly presidential compilation documents were not coded for source frequency or dominant source, as they were comprised of statements by Obama and transcripts from Obama’s speeches and town halls. Focus. Each article’s/document’s primary focus was assess- ed by its lead. To ensure that the dominant focus was captured, the expanded definition of a news lead that includes up to three paragraphs was used (Hillback, Dudo, Wijaya, Dunwood, & Brossard, 2008). Possible foci included the ethics of health care reform (i.e., emphasis on religious perspectives, moral views, the obligations of a civilized society), political/policy implica- tions (i.e., laws, regulations, partisanship), economic implica- tions (i.e., cost to private companies, government, individuals), the public view of the reform(i.e., polling data, public support, public concerns), and humanistic concern about the reform (i.e., an individual’s narrative; the fate of a particular group in need). Themes that fell outside of these parameters were given an alternative synopsizing moniker. Tone. The overall valence of each article and document was determined by coding each paragraph as “positive,” “negative”, or “neutral” towards Obama’s health care reform plan and then assigning a single summary valence code based on the most frequently occurring tone. Articles/opinion pieces and docu- ments with an equal number of positive and negative para- graphs were coded “neutral”. To provide a few examples, a paragraph would have been coded positive if it emphasized “good news” for Obama’s plan (i.e., a report indicating that the plan would alleviate participants’ health costs), reported that particular noteworthy individuals favored the plan, or in the case of an editorial, if the writer openly advocated for the plan. A paragraph would have been coded negative if it exhibited themes converse to these. Paragraphs coded neutral either lack- ed valence or featured an equal number of positive and negative statements. Source frequency. Sources were coded each time they were referenced in the articles. Citations could have been cumulative both within and between sources. For example, an article sourc- ing President Obama four times would be allotted a “4” code for the category President Obama. An article citing three dif- ference private physicians a single time each would be allotted a “3” code for the category private physicians. Possible sources included physicians in private practice, government or aca- demic physicians, economists, academics, political figures (i.e., secretary of state, speaker of the house, senate majority leader), government bureaucrats (i.e., behind the scenes government workers), tea party members, President Obama, insurance company officials, pharmaceutical company officials, nonpro- fits (i.e., advocacy groups, lobbyists, religious figures), citizens, international sources (including politicians or scientists abroad), and anonymous. Sources that fell outside of these parameters were given an alternative synopsizing moniker. Source categories were then combined for each article into “elite” and “non-elite” based on previous research (Fahmy, Wanta, Johnson, & Zhang, 2011): (1) physicians in private practice; (2) government or academic physicians; (3) econo- mists; (4) political figures; (5) academics; and (6) President Obama were categorized as “elite”. All other categories were coded as “non-elite”. Dominant source. Each source category was tabulated every time it was referenced in an article. A “dominant source” code was awarded to the category mentioned most frequently for each article or opinion piece. Coding Reliability 2Regarding the nine documents removed, eight focused on US Veterans’ health care and one referenced the Recovery Act’s effects on health centers. In other words they were not directly related to the topic under study. Two of the authors were involved in the coding process. Practice coding was carried out on non-sample articles until a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 21  S. FAHMY ET AL. keen degree of synchronicity was achieved. Ten percent of articles were ultimately selected at random for a formal reliabi- lity assessment. Reliability was calculated using the reformu- lated Pi equation (Potter & Levine-Donnerstein, 1999). Results indicated favorable reliability for all variables: source frequen- cy = 0.92; tone = 0.87, dominant source = 0.86, focus = 0.76. Reliability was then calculated for the presidential documents. Coder training and practice coding were carried out before 11.5 percent of documents were randomly selected for a formal re- liability assessment. Reliability measures were strong for both variables: focus = 1.00, tone = 1.00. Public Opinion Public opinion data gathered between inauguration and bill passage regarding health care reform were obtained. Because different polls were taken on the same date and time periods for different polls overlapped (i.e., Gallup poll from 2/6 - 2/8, ABC news from 2/5 - 2/8), Rasmussen, which conducted the most polls during this time period, was the only public opinion data examined in this analysis. Rasmussen provided data on the percentage of Americans who, at the time the poll was con- ducted, either favored or opposed Obamacare. The earliest poll employed was conducted between 10 and 11 July, 2009. The lat- est poll employed was conducted between 5 and 6 March, 2010. Proposed Analyses To explore the agenda-building process, this study used fre- quency tests to assess percentage differences across categories of dominant frame, valence (tone), source categories, over-time changes in valence and over-time changes in public opinion. In addition, inferential analyses using independent samples t-tests, Pearson correlation tests, and simple regression models were used as post-hoc assessments of source categories. It is impor- tant to note that the post-hoc simple regression tests were solely employed for exploratory purposes. Specifically, by using the Rasmussen polling data (as will be subsequently discussed), the researchers could not control for key outside factors, including demographics and media use, that may impact the fluctuations in the main outcome variable (favorability ratings). Thus, sim- ple regression analysis was only run to address the possibility that a relationship may exist between these variables. Results Roughly two-thirds (64.5%, n = 276) were coded as news, while roughly 35 percent (35.5%, n = 152) were coded as opi- nion. Regarding dominant news frame, politics/policy implica- tions of health care reform was by far the most common (69.9%, n = 299). The second most frequent dominant news frame fell under the ‘economics/financial’ category (15.4%, n = 66). The remaining portion of the sample—roughly 16 percent of the total—represented mostly the public view concerning health care reform (11.4%, n = 49). Less than 4 percent of the articles on health care reform focused on humanistic concerns (n = 10) or ethics (n = 4).It is important to note that when examining every sample month individually, politics/policy was found to be the dominant theme in at least 50% of all news articles dis- cussing the health care reform bill. In fact, in 7 of the 15 months sampled, the politics/policy theme was the dominant focus of 75% or more of all articles. However, while there did not appear to be substantial variability in the focus of articles across the sample period, from April to June 2009, the eco- nomics tied to health care did become a substantially more prevalent theme in news articles, reflecting 42.9% of dominant focus in April and June, respectively. Of the 17 presidential documents dealing the health care re- form act, the dominant frame used by the President also center- ed on the politics/policy implications of health care reform (n = 9). No other dominant frame was used more than two times in the president’s speeches on health care reform during the time period analyzed. The valence of the articles was fairly evenly split between positive and negatively-toned articles, although a slighter great- er number of articles addressing Obama’s health care plan had a positive tone (46.0%, n = 197) compared to those that were negative (41.1%, n = 176). Less than 13 percent of articles were neutral in tone (12.9%, n = 55). While there appeared to be little difference in the overall percentage of positively versus negatively toned articles, tone varied more substantially based on article type. In particular, results showed that 56.5 percent of news articles had a positive tone compared to only 27 percent of opinion articles, whereas 58.6 percent of opinion articles had a negative tone compared to only 31.5 percent of news articles. In addition, cross-tabulations were run to assess whether the percentage of negatively vs. positively-toned articles varied based on focus of article. Given that the dominant focus of the majority of articles (414 out of 428) comprised the three cate- gories representing politics/policy, economics, and public view, these were the only categories examined for analysis. Results showed that there was an association between dominant focus and tone, χ2 (4, N = 414) = 17.33, p < 0.01). Interestingly, among articles with the dominant focus being politics/policy, fully 48.2% (n = 144) had a positive tone, whereas 36.5% (n = 109) were negative in tone. Conversely, among articles with the dominant focus being the public view of health care reform, only 32.7% (n = 16) were positive in tone, while 63.3% (n = 31) had a negative tone. Roughly equivalent percentages of positive (45.5%; n = 30) and negative (48.5%, n = 32) toned articles were present when the dominant focus was economics of health care. The next analyses involved the dominant sources for news stories on health care reform. Initial tests showed that nearly 19 percent of articles (18.9%, n = 81) had no clear dominant source. Furthermore, an additional 7.2 percent of articles (n = 31) had multiple dominant sources. Thus, articles that had nei- ther dominant source nor multiple dominant sources were re- moved prior to subsequent analyses involving dominant source. Results showed that more than two-thirds of the dominant sources for the remaining articles (n = 316) were elites (69.3%). Subsequent analyses comparing frequencies and percentages of dominant sources across article tone showed that elite source categories were slightly more positive in tone (51.1%) than non-elite source categories (45.4%). In addition, it is important to note that in less than 12 percent of articles was President Obama either the only dominant source or one of the major sources (11.5%). However, refer- ences to Obama varied based on article type. In particular, the President was cited significantly more frequently [t (368.08) = 4.56, p < 0.01] in news articles (M = 1.37) than opinion articles (M = 0.43). In the 41 articles where President Obama was the sole dominant source, 24 of these had a positive tone whereas only 13 had a negative tone. Furthermore, results showed there was a significant positive correlation between the frequency Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 22  S. FAHMY ET AL. that Obama was cited in an article and the tone of the article (measured on a 1 - 3 scale, with 1 = negative, 2 = neutral, 3 = positive): r (428) = 0.18, p < 0.01. Overall, the more frequently President Obama was cited in an article, on average, the more positive the tone of the article. Over-Time Changes in Article Tone, Public Opinion Tests were done to examine whether any changes occurred in the tone of articles discussing Obama’s health care plan be- tween his inauguration and the date the PPACA was signed into law. Tables 1 and 2 break down percentage of positive and negative tone articles in one and two month time frames. The percentage of positively toned articles appears to have peaked between March and May 2009, with roughly 70 percent of all articles discussing Obama’s health care plan reflecting a more positive tone (see Table 2). In particular, nearly 80 percent of articles from late April through late May had a positive tone. However, following this time period, the percentage of posi- tively toned articles diminished substantially. When examined on a one-by-month basis, in only 2 of the final 10 months of the time frame did the percentage of positively toned articles ex- ceed 50 percent (see Table 1). Conversely, the percentage of negatively toned articles was equivalent or higher than the per- centage of positively toned articles for 7 of the final 10 months of this time frame. Interestingly, the percentage of positively toned media arti- cles across the sample time period was found to be significantly correlated with the number of presidential speeches given on this topic (r = 0.76, p < 0.05). This indicates that the more speeches President Obama gave on the health care act in any given month corresponded with an increase in the positive tone of articles discussing this bill. When examining public opinion, average favorability ratings for Obama’s health care plan across all polls during this time Table 1. One month time frame for percentage of positive and negative tone articles. Time Frame % Positive Tone % Negative Tone 1/21/2009-2/20/2009 50% 31.3% 2/21/2009-3/20/2009 56.7% 30% 3/21/2009-4/20/2009 78.9% 21.1% 4/21/2009-5/20/2009 60% 30% 5/21/2009-6/20/2009 38.9% 38.9% 6/21/2009-7/20/2009 44% 44% 7/21/2009-8/20/2009 38.2% 47.3% 8/21/2009-9/20/2009 45.6% 41.2% 9/21/2009-10/20/2010 50% 27.8% 10/21/2009-11/20/2010 43% 43% 11/21/2009-12/20/2010 37.5% 50% 12/21/2009-1/20/2010 33.3% 45.8% 1/21/2009-2/20/2010 30% 60% 2/21/2010-3/23/2010t 52.9% 41.2% Note: The final sample period was longer by three days to incorporate all articles sampled. For the time period restricted to 2/21/10-3/20/10 (n = 46): 50% pos., 43% neg. Table 2. Two month time frame for percentage of positive and negative tone articles. Time Frame % Positive Tone % Negative Tone 1/21/2009-3/20/2009 54.3% 30.4% 3/21/2009-5/20/2009 69.2% 25.6% 5/21/2009-7/20/2009 41.9% 41.9% 7/21/2009-9/20/2009 42.3% 43.9% 9/21/2009-11/20/2009 45.8% 37.5% 11/21/2009-1/20/2010 35.4% 47.9% 1/21/2010-3/23/2010t 44.4% 48.1% Note: The final sample period was longer by three days to incorporate all articles sampled. For the time period restricted to 1/21/10-3/20/10 (n = 76): 42.1% pos., 50% neg. frame was slightly greater than 40 percent (M = 41.93). The percentage favorability for the health care reform bill ranged from 25 percent (8/11-13/2009) to 53 percent (3/1/2010). How- ever, when examining month-by-month averages across polls, there was little variability. In particular, from the first month where multiple polls were taken (July 2009) until the final month of the sample (March 2010), average percentage favora- bility ranged from a high of roughly 44 percent (M = 44.4) to a low of roughly 40 percent (M = 40.73). Additional analyses were performed comparing article tone across the study time period with public support for Obama’s health care plan. Results from these analyses showed that media tone at time 1 significantly predicted favorability ratings at time 2 (β = 0.76, p < 0.05). Table 3 provides the comparison of per- cent articles with positive tone during a specific time period with the earliest favorability rating taken in the following month. Although there was little overall variability in favorabi- lity ratings across the time period, it is interesting that in the two months where the least percentage of articles were positive in tone (November, 2009, January, 2010), subsequent favora- bility ratings in the next month’s poll were also the lowest for the entire sample period (see Table 3). However, while the percentage of positively-toned news articles in November, 2009 (29%) and January 2010 (24%) were substantially less positive than the tone of the respective preceding months [October, 2009 (54%); December, 2010 (40%)], this did not correspond with a similar dramatic drop in favorability across the same time period. Specifically, favorability only dropped four per- cent between the first November poll and the first December poll, and only three percent between the first January poll and the first February poll. The final analyses examined the same time period listed in Table 3 to assess whether frequency of presidential statements predicted subsequent favorability ratings. Results of simple re- gretssion analysis showed that frequency of presidential state- ments in time 1 (i.e., August) was a significant predictor of favorability ratings in time 2 (i.e., September), β = 0.72, p < 0.05. Furthermore, it is important to note that the poll taken in February 2010, which showed the lowest favorability ratings across the entire sample period, was conducted following the only month where President Obama did not give a single spee- ch discussing the health care act. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 23  S. FAHMY ET AL. Table 3. Comparison of percentage of positively tone articles by month and Rasmussen favorability ratings for first poll taken in following month. Month of Published Articles % Positive Tone Date of First Rasmussen Poll Taken in Following Month % Favorability June 42.9% July 10-11, 2009 46 July 38.9% August 9-10, 2009 42 August 40.4% September 8-9, 2009 44 September 46.4% October 2-3, 2009 46 October 53.6% November 7-8, 2009 45 November 28.6% December 4-5, 2009 41 December 40% January 4, 2010 42 January 24.2% February 9-10, 2010 39 February 48.1% March 5-6, 2010 42 Note: Larger font indicates the 2 time periods with smallest percentage of posi- tively toned articles, as well as the lowest favorability ratings based on Rasmus- sen polling. Discussion This study makes several meaningful contributions. While two previous studies have employed the agenda-building fra- mework to examine how presidential rhetoric and elite sourcing may contribute to the news media and publics’ perception to- ward controversial topics such as stem cell research (Fahmy, Relly, & Wanta, 2010) and war (Fahmy, Wanta, Johnson, & Zhang, 2011), this is one of the first studies to apply a compre- hensive approach of agenda-building in the context of Obama’s health care reform (Lambert & Wu, 2011; Wu & Lambert, 2010). Adapting from Robert Entman’s (2003) cascading acti- vation model, this study traced the diffusion of frames by the President and the network of elites through the media to the public, and thus added to the body of agenda-building literature by examining how interpretive frames regarding a health care issue activated and spread in the context of a domestic and con- troversial public health debate. This study also aids in explication of agenda-building in the health care sphere. In exploring the connections among elite sourcing (i.e. President Obama), tone of coverage, and public opinion, results of this study indicate that there was, at best, only a modest link between President Obama’s stance on health care reform and the news coverage of this issue—contradicting findings that suggest the President was the top source of news in the coverage of the health care reform debate (Adams & Cozma, 2012). Consistent with other recent studies involving this issue (Wu & Lambert, 2010), our findings showed more than two-thirds of dominant sources cited were elites; however, in less than 12 percent of the articles analyzed in this study was President Obama either the only dominant source or one of the major sources. Particularly, while the President continued to campaign for his health care plan in 2009-2010, nearly half of all articles sampled emphasized the negative aspects of the plan. In addition, the percentage of negatively-toned articles conti- nued to increase leading up to passage of the bill. That said, the percentage of positively toned articles was significantly corre- lated with the number of presidential speeches discussing the bill. In other words, an increase in presidential speeches on the topic was associated with a similar increase in positive articles during this time period. However, this only indicates that there is a relationship between these factors—it does not show that frequency of presidential speeches led to an increase in the per- centage of positively-toned articles. In fact, results of post-hoc analyses showed that there was no significant association be- tween the frequency of presidential speeches given in one mon- th (i.e., August), and the percentage of positively-toned articles in the following month (i.e., September). Although frequency of positively-toned articles did signifi- cantly predict public opinion in the following month, a closer inspection of the data showed that, surprisingly, public opinion toward health care reform appeared to be mostly unaffected by media coverage. Specifically, average support for the health care bill from June, 2009 through March, 2010 ranged between 40-44 percent. Even following months where articles’ tone be- came substantially less positive, public support did not seem to change significantly, only dropping a few percentage points. The lack of variability in public support across the sample pe- riod may be linked to how the news media chose to frame this issue. Recall that the majority of articles framed this issue as politics or policy. This precise frame may be of less interest to the public because it may not specifically address how the re- form would affect them. In particular, within stories dealing with the politics surrounding this issue, many articles likely focused on health care reform as a ‘contest/game’ or stressed elements of conflict for dramatic effect (Adams & Cozma, 2012). Public opinion data taken around this time frame show- ed that a large percentage of Americans perceived the debate over health care to be negative in tone and disrespectful (Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, 2009). Therefore, by focusing attention on this debate, news media outlets may have turned off readers. Furthermore, those articles that paid more attention to the policy implications of health care reform may have failed to engage readers (McManus, 1992). Conversely, if more articles focused on the economics of health care, humanistic concerns, or general support from U.S. citizens, this may have resonated more with the public, and therefore, led to greater fluctuations in public favorability. Fu- ture experimental research should examine the ways in which different news frames concerning health care influence public support. Furthermore, given how media are increasingly be- coming more fragmented, it is possible that the public is turning to more diverse outlets to gain information on important social topics. Thus, the influence of any one media outlet on public opinion may be diluted by access to more information sources. The modest percentage of positively-toned articles can at least partially be linked to results indicating that news stories covering the health care bill rarely relied on President Obama as a main information source. Moreover, the less frequently Obama was cited in articles, the more negative the tone of the coverage. These findings contradict assumptions made by prior researchers (Wanta & Foote, 1994), which posit that journalis- tic values allow presidents to dominate news frames. Overall, this suggests that within the context of health care reform, the media were modestly successful at building the media agenda. However, results also indicated that presidential rhetoric might have influenced public opinion. Specifically, findings showed the frequency of Obama’s speeches regarding the bill in time 1 significantly predicted subsequent favorability ratings in time 2. Given that there were only 17 presidential speeches dedicated to this topic from June, 2009 through March 2010, these results suggest that there may have been greater support Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 24  S. FAHMY ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 25 for the bill during this timeframe if a larger number of the president’s speeches were focused on this issue. Limitations and Areas for Future Re sea rch As noted in the methods section, a key limitation of the ana- lyses was the inability to control for key factors that may ex- plain fluctuations in public support for health care reform. More specifically, to examine over-time support and its relationship with presidential speeches and tone of news stories, this study used data from Rasmussen, one of the leading polling compa- nies as well as the source that conducted the most polls during this time period. Essentially, the simple regression analyses were performed at an aggregated, macro-level to examine asso- ciations between percentages. Unfortunately, by using Rasmus- sen data, it was not possible to assess demographics, political beliefs, media use habits, or any other attributes that may factor into individual attitudes toward this issue. Future researchers should conduct more individual-level analyses of personal cha- racteristics to control for these factors and ultimately provide a clearer assessment of how presidential communication and news coverage influence public opinion of health care. Further research should continue to explore the role of agen- da building regarding controversial issues and how this role might differ between domestic versus foreign policy debates. Another fruitful area of research would be to explore the con- troversy after passing the bill. Since so much of the subsequent coverage appeared to be negative, perhaps as a result, public opinion turned against it. Furthermore, because the Republican Party strongly opposed the bill from its inception it would be interesting to examine the effects the Republican Party had on framing the debate in the public sphere. Finally, the authors ac- knowledge that this study did not include the analysis of online media. Specifically the role of social media—sparked by Face- book, Twitter, YouTube and other online outlets—in agenda- building appears to be a further area of research. It would be in- teresting for example to look at how competing sources operate online to provide strategic information and influence the way interpretive frames activate and spread to the public. REFERENCES Adams, S., & Cozma, R. (2012). Health care reform coverage improves in 2009-10 over Clinton era. Newspaper Research Journal, 32, 24- 39. Bennett, W. L. (1990). Toward a theory of press-state relations in the United States. Journal of Communication, 40, 103-125. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02265.x Borah, P. (2011). Conceptual issues in framing theory: A systematic examination of a decade’s literature. Journal of Communication, 61, 246-263. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01539.x Conway, B. A. (2012). Addressing the “medical malady”: Second-level agenda setting and public approval of “Obamacare”. Paper present- ed at the annual meeting of the International Communication Asso- ciation (ICA), Phoenix, AZ. Health insurance reform and medicare: Making medicare stronger for America’s. HealthReform. gov. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Health Reform. https://www.healthcare.gov Hillback, E., Dudo, A., Wijaya, R., Dunwoody, S., & Brossard, D. (2008). News leads and news frames in stories about stem cell re- search. Paper presented at the in Association for Education in Jour- nalism & Mass Communication (AEJMC), Chicago, IL. Entman, R. M. (2003). Cascading activation: Contesting the White House’s frame after 9/11,” Political Communication, 20, 415-432. doi:10.1080/10584600390244176 Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a paradigm. Journal of Communication, 4 3, 51-58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x Fahmy, S., Wanta, W., Johnson, T., & Zhang, J. (2011). The Path to War: Exploringa second-level agenda building analysis examining the relationship among the media, the public and the president. In- ternational Communication Gazette, 73, 322-342. doi:10.1177/1748048511398598 Fahmy, S., Relly, J. E., & Wanta, W. (2010). President’s power to frame stem cell views limited. Newspaper Research Journal, 31, 62- 74. Gandy Jr., O. H. (1982). Beyond agenda-setting: Information subsidies and public policy. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Holan, A. D. (2009). Health care reform: A simple explanation. Politi- Fact.com http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/article/2009/aug/13/health-c are-reform-simple-explanation/ Hillback, E. Dudo, A., Wijaya, R., Dunwood, S., & Brossard, D. (2008). News leads and news frames in stories about stem cell research. Pa- per presented at the Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication (AEJMC), Chicago, IL. Johnson, T., & Wanta, W. (1996). Influence dealers: A path analysis model of agenda building during Richard Nixon’s war on drugs. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 73, 181-194. doi:10.1177/107769909607300116 Klein, E. (2009). Health care reform for beginners: The many flavors of the public plan. Washingtonpost.com http://voices.washingtonpost.com/ezra-klein/2009/06/health_care_ref orm_for_beginne_3.html Lambert, C. A., & Wu, D. (2011). Influencing forces or mere interview sources? What media coverage about health care means for key con- stituencies. Paper presented at the in Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication (AEJMC), St Louis, MO. Lang. G. E., & Lang K. (1983) The battle for public opinion: The pre- sident, the press and the polls during Watergate. New York: Colum- bia University press. McManus, J. H. (1992). What kind of commodity is news. Communi- cation Research, 19, 787-805. doi:10.1177/009365092019006007 Nisbet, M. C., & Lewenstein, B. V. (2002). Biotechnology and the American media: The policy process and the elite press, 1970 to 1999. Science Communication, 23, 359-391. doi:10.1177/107554700202300401 Obama, B. (2008). One month to go: Focus on health care [speech transcript]. http://www.presidentialrhetoric.com/campaign2008/obama/10.04.08. html Obama, B. (2009). Inaugural address [speech transcript]. http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/inaugural-address Pew Research Center for the People, & The Press. (2009). Health care debate seen as rude and disrespectful.Washington, DC: Author. Potter, W. J., & Levine-Donnerstein, D. (1999). Rethinking reliability and validity in content analysis. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 27, 258-284. doi:10.1080/00909889909365539 Ragas, M. (2012). Issue and stakeholder intercandidate agenda setting among corporate subsidies. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 89, 91-111. doi:10.1177/1077699011430063 Wanta, W., & Kalyango, Y. (2007). Terrorism and Africa: A study of agenda building in the United States. International Journal of Public Opinion Quarterly, 19, 434-450. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edm028 Wanta, W., Stephenson, M. A., Turk. J. V., & McCombs, M. E. (1989). How president’s state of the union talk influenced news media agen- das. Journalism Quarterly, 66, 537-541. doi:10.1177/107769908906600301 Wanta, W., & Foote, J. (1994). The president-news media relationship: A time series analysis of agenda-setting, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 38, 437-448. doi:10.1080/08838159409364277 Wu, H. D., & Lambert, C. A. (2010). Mediated struggle in a bill-mak- ing process: Howsources shaped news coverage about health care reform. Paper presented at the in Association for Education in Jour- nalism & Mass Communication (AEJMC), Denver, CO.

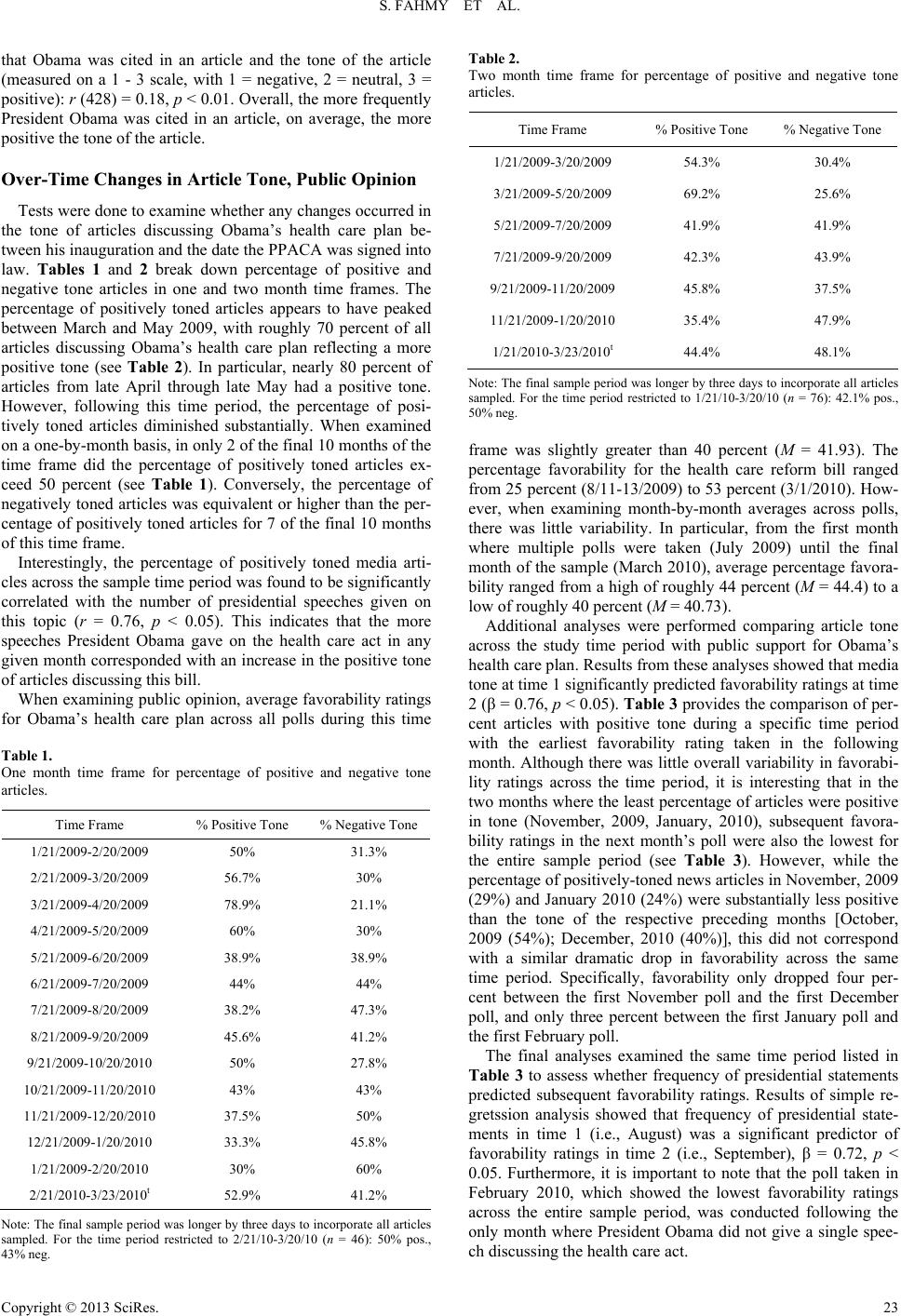

|