Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

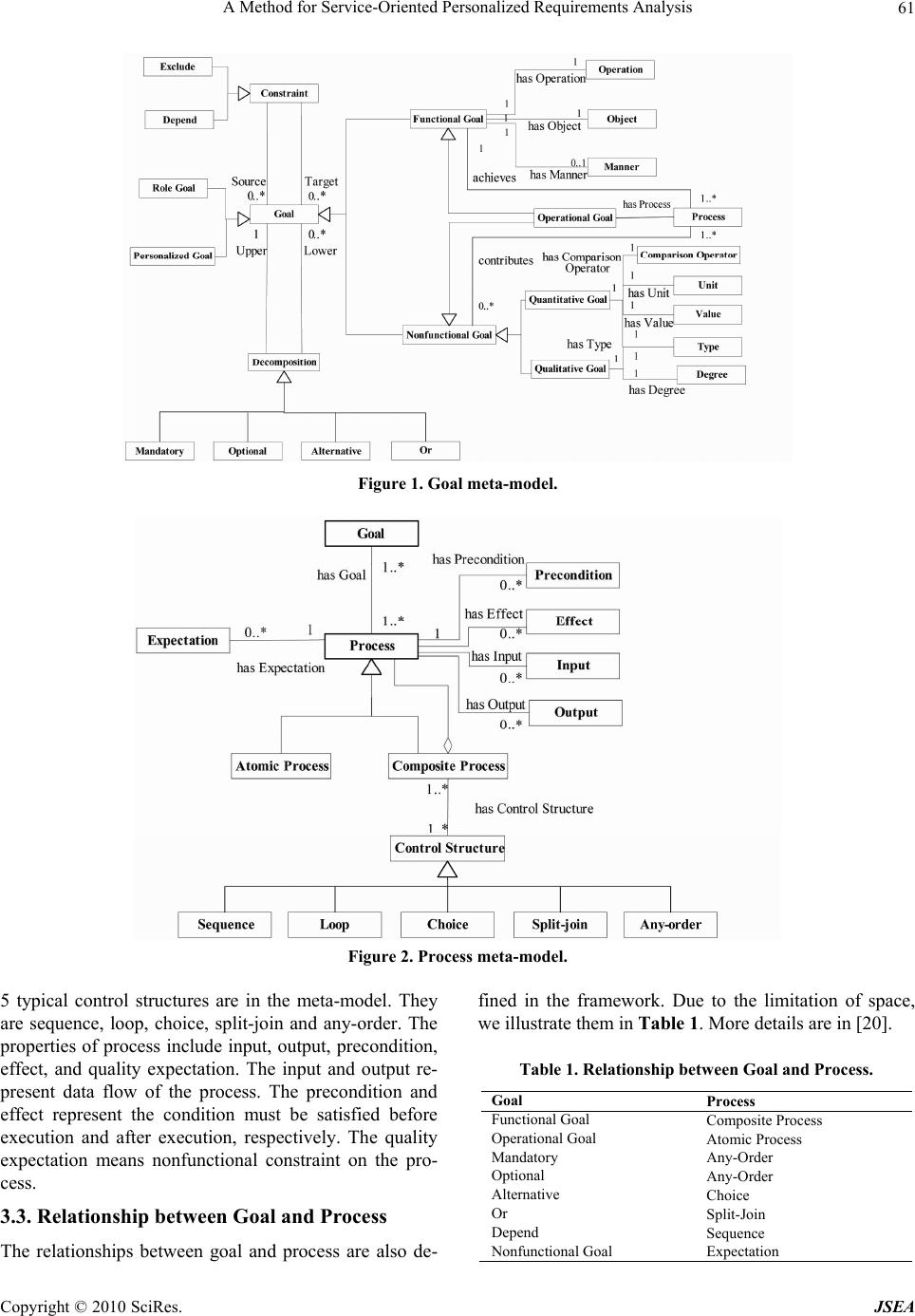

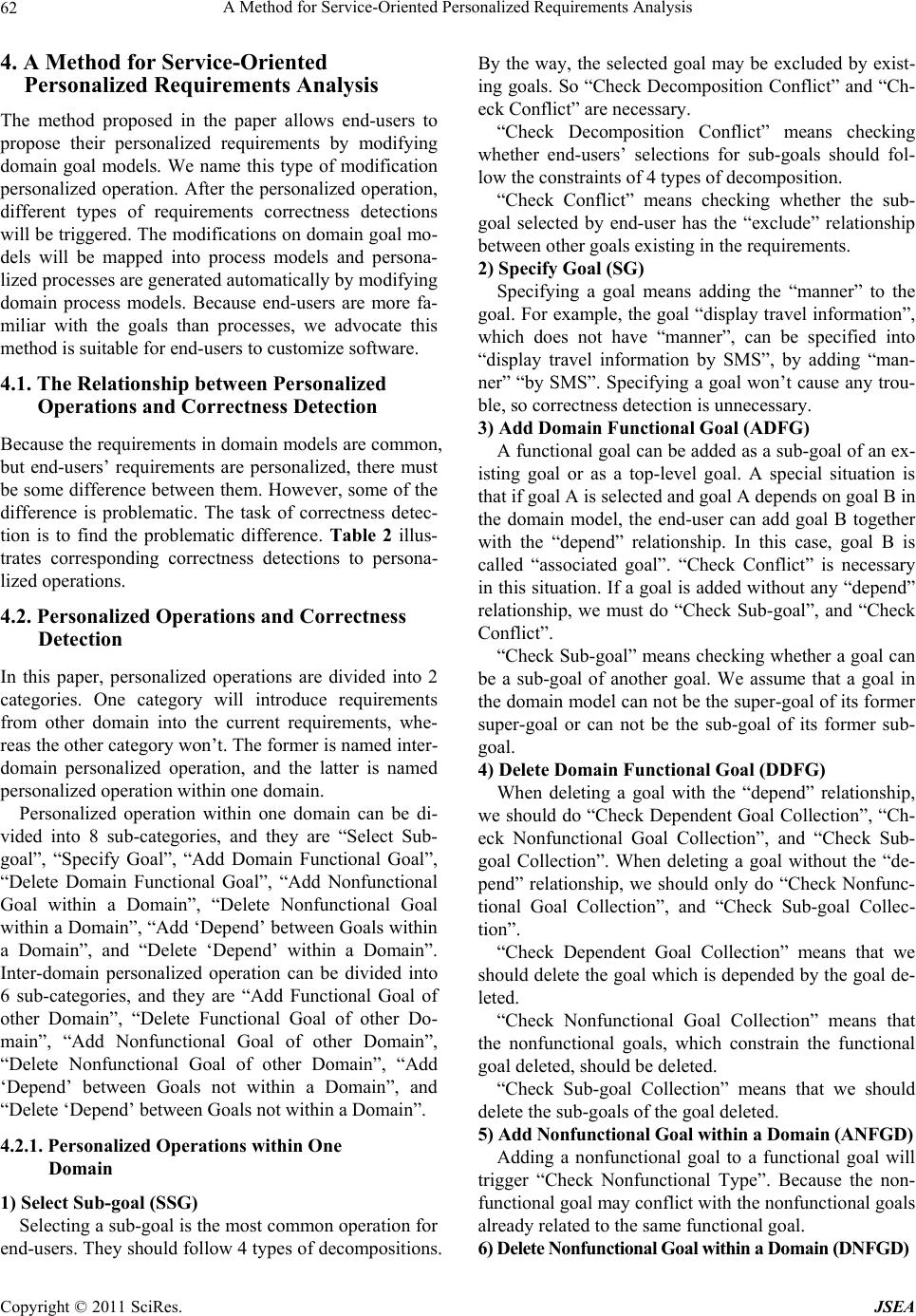

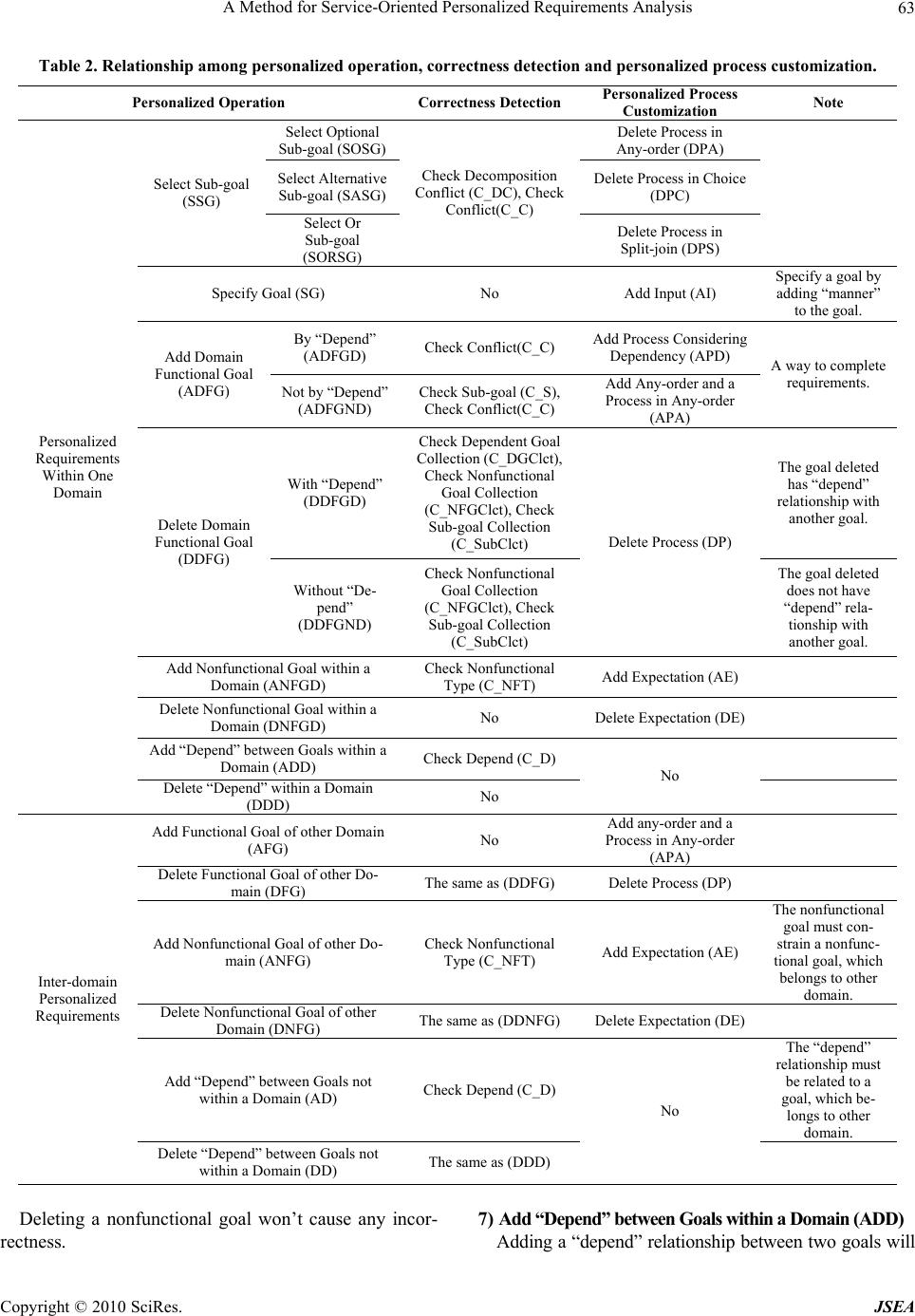

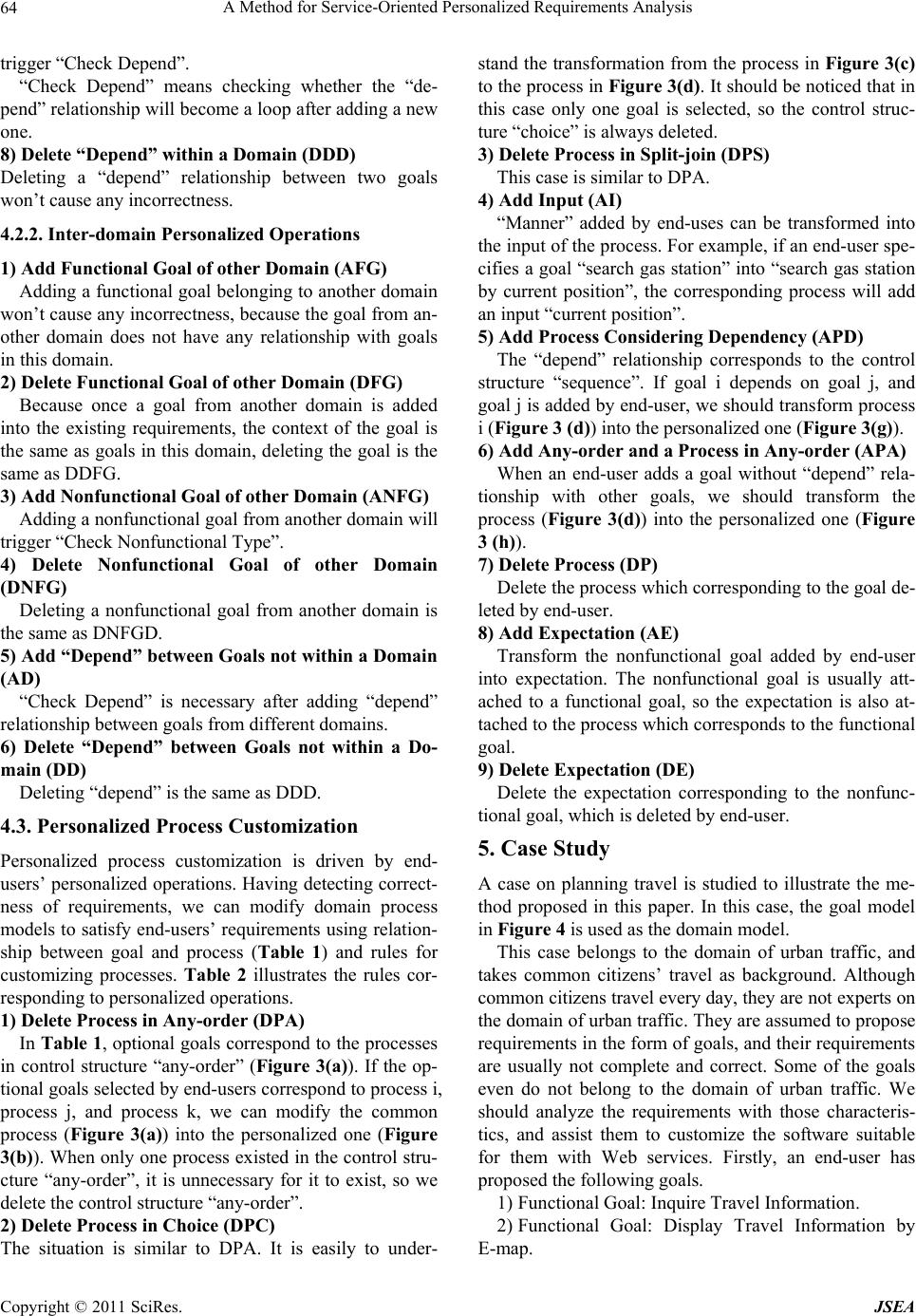

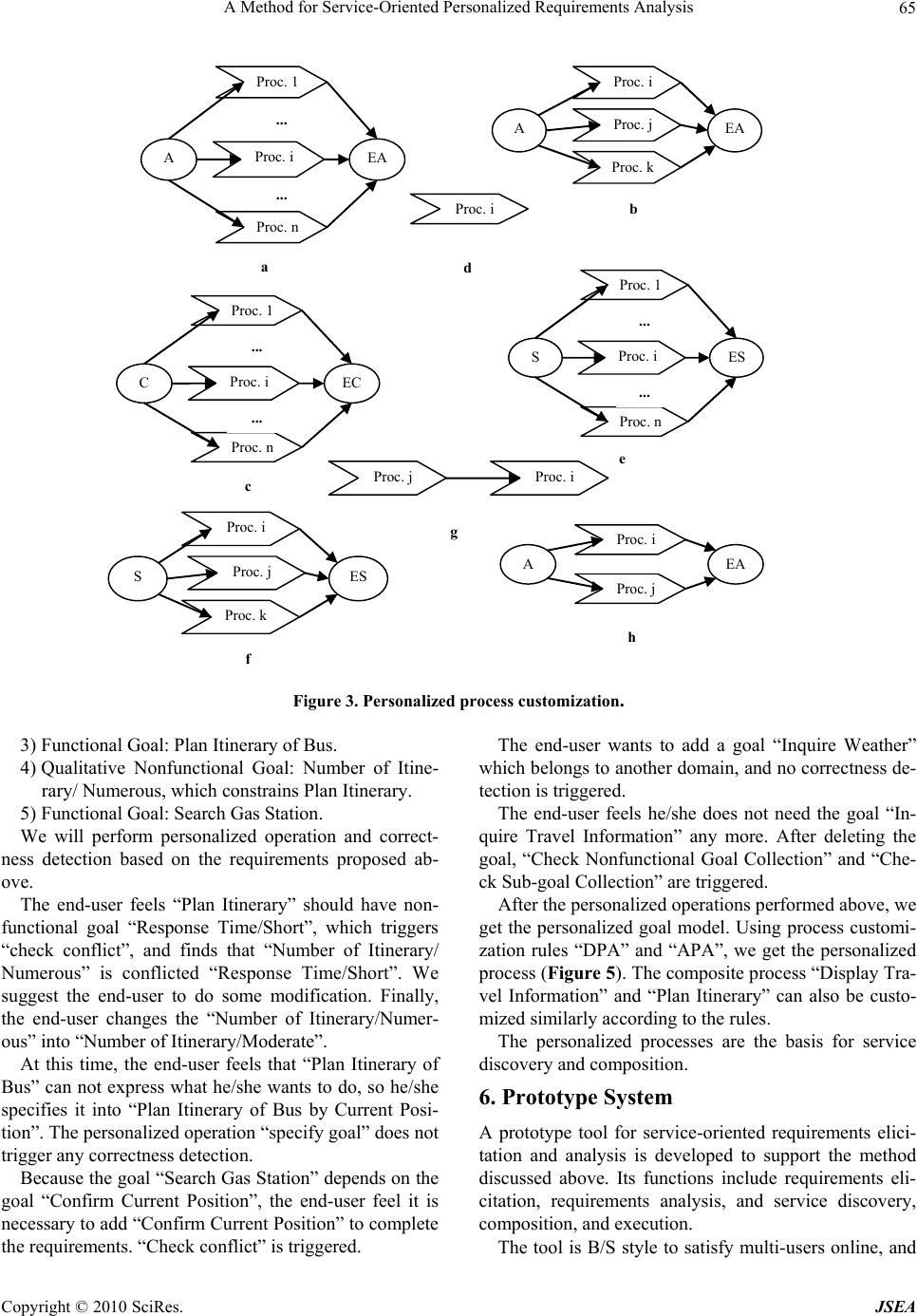

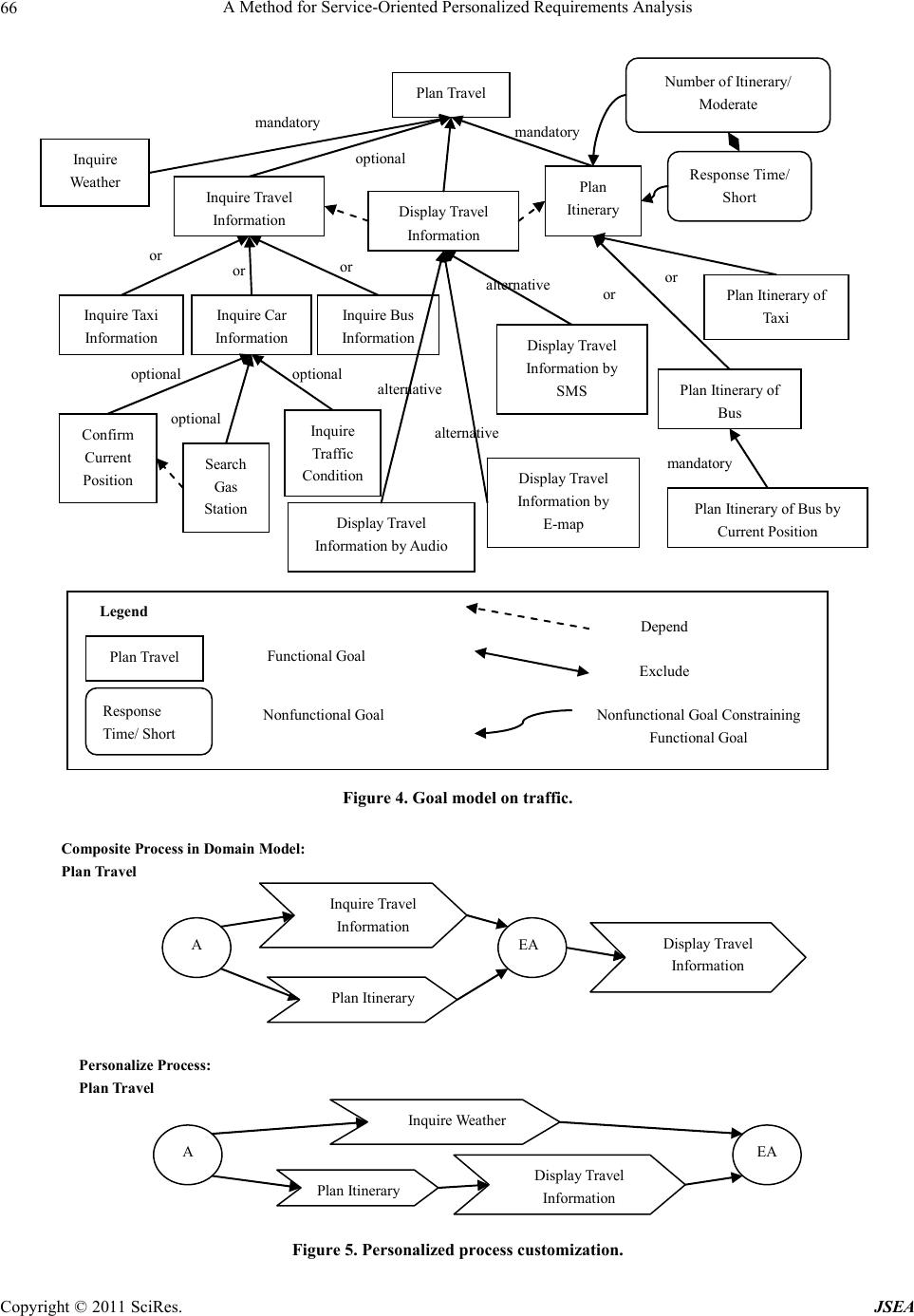

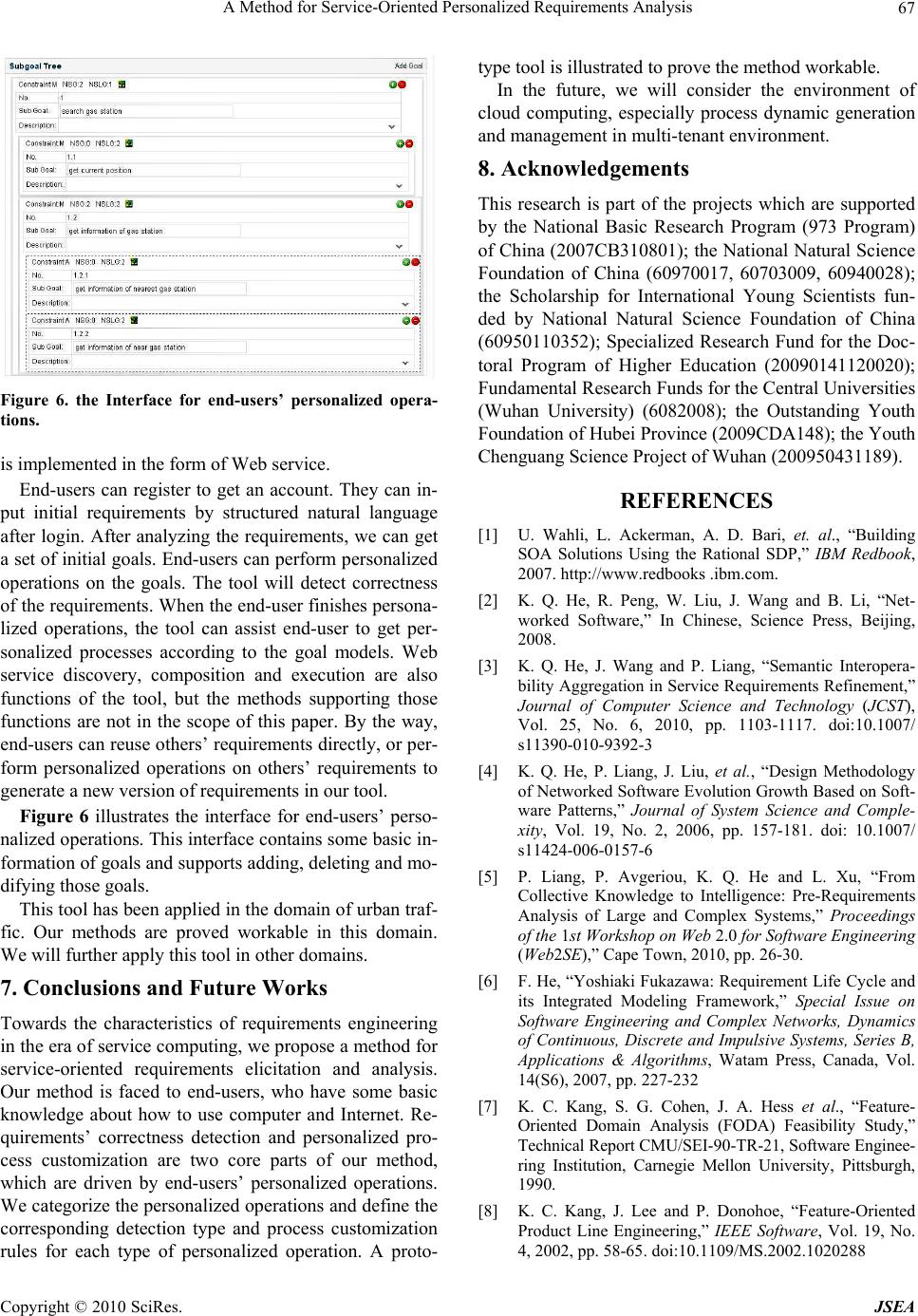

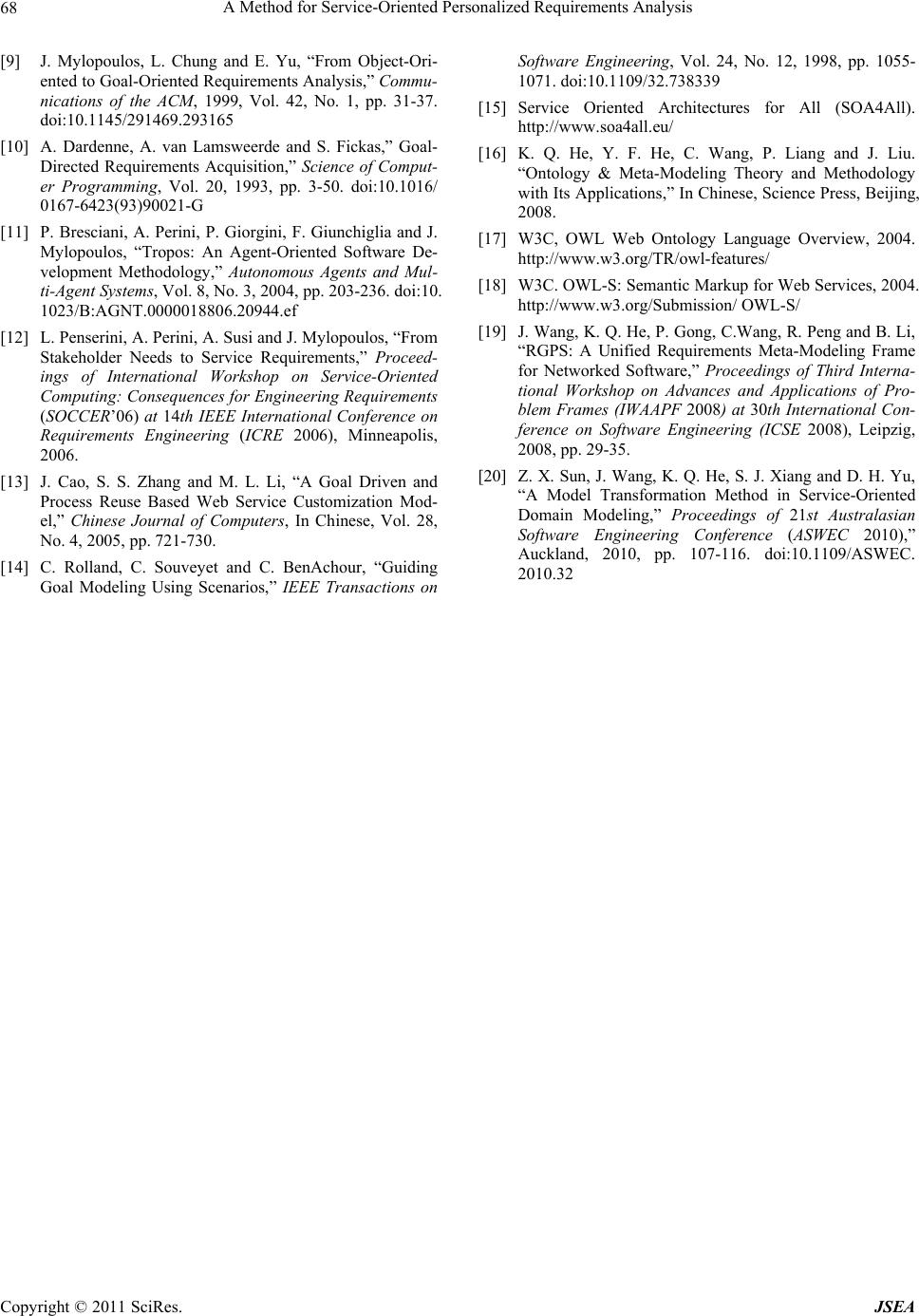

Journal of Software Engineering and Applications, 2011, 1, 59-68 doi:10.4236/jsea.2011.41007 Published Online January 2011 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jsea) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis Huafeng Chen, Keqing He State Key Laboratory of Software Engineering, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China Email: canada186771@yahoo.com.cn, hekeqing@public.wh.hb.cn Received November 22nd, 2010; revised December 4th, 2010; accepted December 20th, 2010. ABSTRACT The development of Web service has changed the process of software production, and requirements engineering be- comes the key issue of service-oriented software engineering. Meantime, it reduces the degree of difficulty of software production, which facilitates end-users to customize software according to their personalized requirements. The paper proposes a method for service-oriented personalized requirements analysis, which is based on domain goal model and process model. The method can inform users of potential errors in requirements by detecting the correctness of re- quirements, which is driven by users’ personalized operations on goal models, and customize personalized processes to satisfy users’ requirements by reusing domain processes. The personalized processes are the basis for Web service dis- covery and composition. Keywords: Personalized Requirements Analysis, Requirements Correctness Detection, Personalized Process Customization, Domain Model, Web Service 1. Introduction The development of Web service has changed the pro- cess of software production. Tradition ally, the process of software production includes several phases, such as re- quirements elicitation and analysis, design, coding and test. However, in the era of service co mputing, more and more Web services are deployed on the Internet, which provide plenty of resources for software development and facilitate a novel software production methodology “Meet-in-the-Middle” [1]. This novel methodology re- duces the degree of difficulty of software production and makes it possible for end-users with some knowledge about computer to customize their own software accord- ing to their personalized requirements. The software is composed of Web services and can be changed easily according to the requirements. Because the software is living on the Internet, we name it networked software [2-6]. Using existing Web services is the basis for customiz- ing networked software, so the key problem to solve is how to get accurate requirements from end-user, rather than design and coding. To serve the end-user well, we think a tool to support the procedure of customization is necessary. The tool should give them a lot of tips during the customization, since end-users are always without expert knowledge about software, but some knowledge about what they want to do. These tips should come from domain models which are constructed by experts beforehand. Domain models usually include common requirements and solutions, but requirements from end-users are al- ways personalized. The paper focuses on how to analyze end-users’ personalized requirements using common req- uirements in domain models. The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 is about related works. In Section 3, the RGPS requirements me- ta-model framework is introduced, which is the guideline of constructing domain models used in requirements ana- lysis. In Section 4, we introduce how to analyze service- oriented personalized requirements based on domain mo- dels. The procedure of analysis includes detecting the co- rrection of personalized requirements and personalized process customization. A case study is illustrated in Sec- tion 5. A prototype tool based on our method is intro- duced in Section 6. The last section concludes the paper and proposes some problems should be solved in the future. 2. Related Works Our method in this paper is related to several ideas or methodologies, such as mass customization, goal-orien-  A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 60 ted requirements analysis, and techniques fo r personalized process customization. The idea of mass customization is successfully applied in software engineering. One proof is the birth of soft- ware product line, which is related to domain analysis and modeling. Constructing domain requirements assets is usually necessary. Feature-oriented domain analysis [7] is very useful to construct common requirements and va- riable requirements [8]. The decomposition of goals in RGPS meta-model adopts similar idea. Goal-oriented requirements analysis is popular after object-oriented requirements analysis [9]. It is more sui- table for people without expert knowledge to describe requirements. KAOS [10] and Tropos [11] are classical goal-oriented requirements analysis methods. In the era of service computing, goal-oriented requi- rements analysis is still full of vitality. Tropos is exten- ded to make it possible to get service specification [12]. Personalized process customization is the key techni- que in service computing. A Web service customization model is constructed in [13], which is related to process customization. Web service customization is achieved by applying goal ontology model, process component reuse and flexible process defining. The process is described with ECA [14], and users are allowed to modify process directly. One of the characteristics of our work is that we face end-user. Service Oriented Architectures for All (SOA4All) is a large-scale integrating project funded by the European Seven th Framework Programme, under the Service and Software Architectures, Infrastructures and Engineering research area [15], which also faces end- user. The objective of SOA4All is to make the service Web as accessible and ubiquitous as today's information Web. It aims at integrating SOA and four complementary and revolutionary technical advances (the Web, context- aware technologies, Web 2.0 and Semantic Web) into a coherent and domain independent worldwide service de- livery platform. 3. RGPS Requirements Meta-Model Framework The RGPS requirements meta-model framework adopts ontology & meta-modeling theory [16], and defines 4 types of elements required by service-oriented require- ments modeling. They are role, goal, process and service, res- pectively. The role model and the goal model are des- cribed in OWL [17], and the process model and the service model are described in OWL-S [18]. All the models are annotated with ontology, which makes it possible for semantic inquiry and reasoning. 4 types of elements are not isolated. A role can have goals, a goal can be achieved by processes, and a process can be rea- lized by services. This requirements meta-model framework can be used to guide domain experts to cons truct domain models. The common requirements assets in domain models can be used to analyze requirements and customize personalized process. For the goal and the process are greatly related to this paper, we will look further into them. For the compre- hensive understanding of RG PS, we can ref e r to [19]. 3.1. Goal Meta-Model Goals and relationships between goals are two major ele- ments in the goal meta-model (Figure 1). Goals are de- fined as the target state of the system users expect, and are divided in to functional goals and non functional goals. Functional goals have 3 properties, and they are operation, such as “display”, object, such as “travel information”, and manner, such as “by SMS”. Nonfunctional goals are further divided into qualitative nonfunctional goal and quantitative nonfunctional goal. The former, such as “fast responsible time”, includes nonfunctional type, such as “responsible time”, and degree, such as “fas t”. Th e latter , such as “cost less than 20 dollars”, includes nonfunctional type, such as “cost”, comparison operator, such as “less”, value, such as “20”, and unit, such as “dollar”. A non- functional goal can affect one functional goal or the whole system. The relationship between goals can be divided into horizontal relationship and vertical relationship. The for- mer include “depend” and “exclude”. The “depend” rela- tionship means that if the goal A is selected, the goal B which is depended by the goal A, should be selected. The goal A is the source end, and th e goal B is the target end. The “exclude” relationship means that if a goal is se- lected, all the goals exclude it sho uld not be selected. The vertical relationship between goals is “decompose”. Goals can be refined by decomposition until operational goals which can be achieved by processes. We define 4 types of decomposition, and they are “mandatory”, “op- tional”, “alternative” and “or”. The “mandatory” means that if the super goal is selected, the sub-goal should be selected. The “optional” means that if the super goal is selected, the sub-goal could be selected or not. The “al- ternative” means that if the super goal is selected, one of the sub-goals in a group should be selected. The “or” means that if the super goal is selected, at least one of the sub-goals in a group should be selected. 3.2. Process Meta-Model The process meat-model includes process and its proper- ties (Figure 2). The process can be divided into atomic process and composite process. Atomic processes are composed into a composite process by control structures.  A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 61 Figure 1. Goal meta-model. Figure 2. Process meta-model. 5 typical control structures are in the meta-model. They are sequence, loop, choice, split-join and any-order. The properties of process include input, output, precondition, effect, and quality expectation. The input and output re- present data flow of the process. The precondition and effect represent the condition must be satisfied before execution and after execution, respectively. The quality expectation means nonfunctional constraint on the pro- cess. 3.3. Relationship between Goal and Process The relationships between goal and process are also de- fined in the framework. Due to the limitation of space, we illustrate them in Table 1. More details are in [20]. Table 1. Relationship betwee n Goal and Proc ess. Goal Process Functional Goal Composite Process Operational Goal Atomic Process Mandatory Any-Order Optional Any-Order Alternative Choice Or Split-Join Depend Sequence Nonfunctional Goal Expectation  A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 62 4. A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis The method proposed in the paper allows end-users to propose their personalized requirements by modifying domain goal models. We name this type of modification personalized operation. After the personalized operation, different types of requirements correctness detections will be triggered. The modifications on domain goal mo- dels will be mapped into process models and persona- lized processes are generated automatically by modifying domain process models. Because end-users are more fa- miliar with the goals than processes, we advocate this method is suitable for end-users to customize software. 4.1. The Relationship between Personalized Operations and Correctness Detection Because the requirements in domain models are common, but end-users’ requirements are personalized, there must be some difference between them. However, some of the difference is problematic. The task of correctness detec- tion is to find the problematic difference. Table 2 illus- trates corresponding correctness detections to persona- lized operations. 4.2. Personalized Operations and Correctness Detection In this paper, personalized operations are divided into 2 categories. One category will introduce requirements from other domain into the current requirements, whe- reas the other category won’t. The former is named inter- domain personalized operation, and the latter is named personalized operation within one domain. Personalized operation within one domain can be di- vided into 8 sub-categories, and they are “Select Sub- goal”, “Specify Goal”, “Add Domain Functional Goal”, “Delete Domain Functional Goal”, “Add Nonfunctional Goal within a Domain”, “Delete Nonfunctional Goal within a Domain”, “Add ‘Depend’ between Goals within a Domain”, and “Delete ‘Depend’ within a Domain”. Inter-domain personalized operation can be divided into 6 sub-categories, and they are “Add Functional Goal of other Domain”, “Delete Functional Goal of other Do- main”, “Add Nonfunctional Goal of other Domain”, “Delete Nonfunctional Goal of other Domain”, “Add ‘Depend’ between Goals not within a Domain”, and “Delete ‘Depend’ between Goals not within a Domain”. 4.2.1. Personalized Operations within One Domain 1) Select Sub-goal (SSG) Selecting a sub-goal is the most common operation for end-users. They should follow 4 types of deco mpositions. By the way, the selected goal may be excluded by exist- ing goals. So “Check Decomposition Conflict” and “Ch- eck Conflict” are necessary. “Check Decomposition Conflict” means checking whether end-users’ selections for sub-goals should fol- low the constraints of 4 types of d e composition. “Check Conflict” means checking whether the sub- goal selected by end-user has the “exclude” relationship between other goals existing in the requirements. 2) Specify Goal (SG) Specifying a goal means adding the “manner” to the goal. For example, the goal “display travel information”, which does not have “manner”, can be specified into “display travel information by SMS”, by adding “man- ner” “by SMS”. Specifying a goal won’t cause any trou- ble, so correctness detection is unnecessary. 3) Add Domain Functional Goal (ADFG) A functional goal can be added as a sub-goal of an ex- isting goal or as a top-level goal. A special situation is that if goal A is selected and goal A depends on goal B in the domain model, the end-user can add goal B together with the “depend” relationship. In this case, goal B is called “associated goal”. “Check Conflict” is necessary in this situation. If a goal is add ed without any “depend” relationship, we must do “Check Sub-goal”, and “Check Conflict”. “Check Sub-goal” means checking whether a goal can be a sub-goal of another goal. We assume that a goal in the domain model can not be the super-goal of its former super-goal or can not be the sub-goal of its former sub- goal. 4) Delete Domain Functional Goal (DDFG) When deleting a goal with the “depend” relationship, we should do “Check Dependent Goal Collection”, “Ch- eck Nonfunctional Goal Collection”, and “Check Sub- goal Collection”. When deleting a goal without the “de- pend” relationship, we should only do “Check Nonfunc- tional Goal Collection”, and “Check Sub-goal Collec- tion”. “Check Dependent Goal Collection” means that we should delete the goal which is depended by the goal de- leted. “Check Nonfunctional Goal Collection” means that the nonfunctional goals, which constrain the functional goal deleted, should be deleted. “Check Sub-goal Collection” means that we should delete the sub-go a ls of the goal deleted. 5) Add Nonfunctional Goal within a Domain (ANFGD) Adding a nonfunctional goal to a functional goal will trigger “Check Nonfunctional Type”. Because the non- functional goal may conflict with the nonfunctional goals already related to the same functional goal. 6) Delete N onfunction al Goal w ithin a Dom ain (DNFGD)  A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 63 Table 2. Relationship among personalized operation, correctness detection and personalized process customization. Personalized Operation Correctness Detection Personalized Process Customization Note Personalized Requirements Within One Domain Select Sub-goal (SSG) Select Optional Sub-goal (SOSG) Check Decomposition Conflict (C_DC), Check Conflict(C_C) Delete Process in Any-order (DPA) Select Alternative Sub-goal (SASG)Delete Process in Choice (DPC) Select Or Sub-goal (SORSG) Delete Process in Split-join (DPS) Specify Goal (SG) No Add Input (AI) Specify a goal by adding “manner” to the goal. Add Domain Functional Goal (ADFG) By “Depend” (ADFGD) Check Conflict(C_C) Add Process Considering Dependency (APD) A way to complete requirements. Not by “Depend” (ADFGND) Check Sub-goal (C_S), Check Conflict(C_C) Add Any-order and a Process in Any-order (APA) Delete Domain Functional Goal (DDFG) With “Depend” (DDFGD) Check Dependent Goal Collection (C_DGClct), Check Nonfunctional Goal Collection (C_NFGClct), Check Sub-goal Collection (C_SubClct) Delete Process (DP) The goal deleted has “depend” relationship with another goal. Without “De- pend” (DDFGND) Check Nonfunctional Goal Collection (C_NFGClct), Check Sub-goal Collection (C_SubClct) The goal deleted does not have “depend” rela- tionship with another goal. Add Nonfunctional Goal within a Domain (ANFGD) Check Nonfunctional Type (C_NFT) Add Expectation (AE) Delete Nonfunctional Goal within a Domain (DNFGD) No Delete Expectation (DE) Add “Depend” between Goals within a Domain (ADD) Check Depend (C_D) No Delete “Depend” within a Domain (DDD) No Inter-domain Personalized Requirements Add Functional Goal of other Domain (AFG) No Add any-order and a Process in Any-order (APA) Delete Functional Goal of other Do- main (DFG) The same as (DDFG) Delete Process (DP) Add Nonfunctional Goal of other Do- main (ANFG) Check Nonfunctional Type (C_NFT) Add Expectation (AE) The nonfunctional goal must con- strain a nonfunc- tional goal, which belongs to other domain. Delete Nonfunctional Goal of other Domain (DNFG) The same as (DDNFG) Delete Expectation (DE) Add “Depend” between Goals not within a Domain (AD) Check Depend (C_D) No The “depend” relationship must be related to a goal, which be- longs to other domain. Delete “Depend” between Goals not within a Domain (DD) The same as (DDD) Deleting a nonfunctional goal won’t cause any incor- rectness. 7) Add “Depend” between Goals within a Domain (ADD) Adding a “depend” relationship between two goals will  A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 64 trigger “Check Depend”. “Check Depend” means checking whether the “de- pend” relationship will become a loop after adding a new one. 8) Delete “Depend” within a Domain (DDD) Deleting a “depend” relationship between two goals won’t cause any incorrectness. 4.2.2. Inter-domain Personalized Operations 1) Add Functional Goal of other Domain (AFG) Adding a functional goal belonging to another domain won’t cause any incorrectness, because the goal from an- other domain does not have any relationship with goals in this domain. 2) Delete Functional Goal of other Domain (DFG) Because once a goal from another domain is added into the existing requirements, the context of the goal is the same as goals in this domain, deleting the goal is the same as DDFG. 3) Add Nonfunctional Goal of other Domain (ANFG) Adding a nonfunctional goal from another domain will trigger “Check Nonfunctional Type”. 4) Delete Nonfunctional Goal of other Domain (DNFG) Deleting a nonfunctional goal from another domain is the same as DNFGD. 5) Add “Depend” between Goals not within a Domain (AD) “Check Depend” is necessary after adding “depend” relationship between goals from different domains. 6) Delete “Depend” between Goals not within a Do- main (DD) Deleting “depend” is the same as DDD. 4.3. Personalized Process Customization Personalized process customization is driven by end- users’ personalized operations. Having detecting correct- ness of requirements, we can modify domain process models to satisfy end-users’ requirements using relation- ship between goal and process (Table 1) and rules for customizing processes. Table 2 illustrates the rules cor- responding to pers o nal i zed o perati o ns. 1) Delete Process in Any-order (DPA) In Tab le 1, optional goals correspond to the processes in control structure “any-order” (Figure 3(a)). If the op- tional goals selected by end-users correspond to process i, process j, and process k, we can modify the common process (Figure 3(a)) into the personalized one (Figure 3(b)). When only one process existed in the control stru- cture “any-order”, it is unnecessary for it to exist, so we delete the control structure “any-order”. 2) Delete Process in Choice (DPC) The situation is similar to DPA. It is easily to under- stand the transformation from the process in Figure 3(c) to the process in Figure 3(d). It should be noticed that in this case only one goal is selected, so the control struc- ture “choice” is always deleted. 3) Delete Process in Split-join (DPS) This case is similar to DPA. 4) Add Input (AI) “Manner” added by end-uses can be transformed into the input of the process. For example, if an end-user spe- cifies a goal “search gas station” into “search gas station by current position”, the corresponding process will add an input “current position”. 5) Add Process Considering Dependency (APD) The “depend” relationship corresponds to the control structure “sequence”. If goal i depends on goal j, and goal j is added by end-user, we should transform process i (Figure 3 (d)) into the personalized one (Figure 3(g)). 6) Add Any-order and a P rocess in Any-order (APA) When an end-user adds a goal without “depend” rela- tionship with other goals, we should transform the process (Figure 3(d)) into the personalized one (Figure 3 (h)). 7) Delete Process (DP) Delete the process which corresponding to the goal de- leted by end-user. 8) Add Expectation (AE) Transform the nonfunctional goal added by end-user into expectation. The nonfunctional goal is usually att- ached to a functional goal, so the expectation is also at- tached to the process which corresponds to the functional goal. 9) Delete Expectation (DE) Delete the expectation corresponding to the nonfunc- tional goal, which is de leted by end-user. 5. Case Study A case on planning travel is studied to illustrate the me- thod proposed in this paper. In this case, the goal model in Figure 4 is used as the domain model. This case belongs to the domain of urban traffic, and takes common citizens’ travel as background. Although common citizens travel every day, they are not experts on the domain of urban traffic. They are assumed to propose requirements in the form of goals, and their requirements are usually not complete and correct. Some of the goals even do not belong to the domain of urban traffic. We should analyze the requirements with those characteris- tics, and assist them to customize the software suitable for them with Web services. Firstly, an end-user has proposed the following goals. 1) Functional Goal: Inquire Travel Information. 2) Functional Goal: Display Travel Information by E-map.  A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 65 ... Proc. 1 A Proc. n EA Proc. i ... a Proc. i A Proc. j EA Proc. k b ... Proc. 1 C Proc. n EC Proc. i ... c Proc. i d ... Proc. 1 S Proc. n ES Proc. i ... e Proc. i S Proc. j ES Proc. k f Proc. j Proc. i g Proc. i A Proc. j EA h Figure 3. Personalized process customization. 3) Functional Goal: Plan Itinerary of Bus. 4) Qualitative Nonfunctional Goal: Number of Itine- rary/ Numerous, which constrains Plan Itinerary. 5) Functional Goal: Search Gas Station. We will perform personalized operation and correct- ness detection based on the requirements proposed ab- ove. The end-user feels “Plan Itinerary” should have non- functional goal “Response Time/Short”, which triggers “check conflict”, and finds that “Number of Itinerary/ Numerous” is conflicted “Response Time/Short”. We suggest the end-user to do some modification. Finally, the end-user changes the “Number of Itinerary/Numer- ous” into “Number of Itinerary/Moderate”. At this time, the end-user feels that “Plan Itinerary of Bus” can not express what he/she wants to do, so he/she specifies it into “Plan Itinerary of Bus by Current Posi- tion”. The personalized operation “specify goal” does not trigger any correctness detection. Because the goal “Search Gas Station” depends on the goal “Confirm Current Position”, the end-user feel it is necessary to add “Confirm Current Position” to co mplete the requirements. “Check conflict” is triggered. The end-user wants to add a goal “Inquire Weather” which belongs to another domain, and no correctness de- tection is triggered. The end-user feels he/she does not need the goal “In- quire Travel Information” any more. After deleting the goal, “Check Nonfunctional Goal Collection” and “Che- ck Sub-goal Collection” are triggered. After the personalized operations performed above, we get the personalized goal model. Using process customi- zation rules “DPA” and “APA”, we get the personalized process (Figure 5). The composite process “Display Tra- vel Information” and “Plan Itinerary” can also be custo- mized similarly according to the rules. The personalized processes are the basis for service discovery and composition. 6. Prototype System A prototype tool for service-oriented requirements elici- tation and analysis is developed to support the method discussed above. Its functions include requirements eli- citation, requirements analysis, and service discovery, composition, and execution. The tool is B/S style to satisfy multi-users online, and  A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 66 alternative or optional mandatory optional optional or or or or optional mandatory mandatory alternative alternative Plan Travel Plan Itinerary of Bus Plan Itinerary of Taxi Display T ravel Information by E-map Plan Itinerary In qu ir e Trave l Informati o n Inquire Bus Informatio n Inquire Car Informatio n Display Trave l Information Display T ravel Information by SMS Display Travel Inf o r m atio n by A udio Inquire Taxi Informati o n Search Gas Station Inquire Traffic Condition Response Time/ Short Plan Itinerary of Bus by Current Positio n Number of Itin er ary/ Moderate Confirm Current Position Inquire Weather Plan Travel Legend Functional Goal Nonfunctional Goal Depend Exclude Nonfunctional Goal Constraining Functional Goal Response Time/ Sho rt Figure 4. Goal model on traffic. A EA Composite Process in Domain Model: Plan Trave l Inquire Weathe r A Plan Itinerar y EA Display T ravel Information Inquir e Trav e l Information Plan Itinerary Display T ravel Information Persona lize Proc ess: Plan Travel Figure 5. Personalized process customization.  A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 67 Figure 6. the Interface for end-users’ personalized opera- tions. is implemented in the form of Web service. End-users can register to get an account. They can in- put initial requirements by structured natural language after login. After analyzing the requirements, we can get a set of initial goals. End-user s can perform personalized operations on the goals. The tool will detect correctness of the requ irements. When the end -user finis hes pers ona- lized operations, the tool can assist end-user to get per- sonalized processes according to the goal models. Web service discovery, composition and execution are also functions of the tool, but the methods supporting those functions are not in the scope of this paper. By the way, end-users can reuse others’ requirements directly, or per- form personalized operations on others’ requirements to generate a new version of requirements in our tool. Figure 6 illustrates the interface for end-users’ perso- nalized operations. This interface contains some basic in- formation of goals and su pports add ing, deletin g and mo- difying those goals. This tool has been applied in the domain of urban traf- fic. Our methods are proved workable in this domain. We will further apply this tool in other domains. 7. Conclusions and Future Works Towards the characteristics of requirements engineering in the era of service computing, we propose a method for service-oriented requirements elicitation and analysis. Our method is faced to end-users, who have some basic knowledge about how to use computer and Internet. Re- quirements’ correctness detection and personalized pro- cess customization are two core parts of our method, which are driven by end-users’ personalized operations. We categorize the personalized operations and define the corresponding detection type and process customization rules for each type of personalized operation. A proto- type tool is illustrated to prove the method workab le. In the future, we will consider the environment of cloud computing, especially process dynamic generation and management in multi-tenant environmen t. 8. Acknowledgements This research is part of the projects which are supported by the National Basic Research Program (973 Program) of China (2007CB31080 1); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (60970017, 60703009, 60940028); the Scholarship for International Young Scientists fun- ded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (60950110352); Specialized Research Fund for the Doc- toral Program of Higher Education (20090141120020); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Wuhan University) (6082008); the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Hubei Province (2009CDA148); the Youth Chenguang Science Project of Wuhan (200950431189). REFERENCES [1] U. Wahli, L. Ackerman, A. D. Bari, et. al., “Building SOA Solutions Using the Rational SDP,” IBM Redbook, 2007. http://www.redbooks .ibm.com. [2] K. Q. He, R. Peng, W. Liu, J. Wang and B. Li, “Net- worked Software,” In Chinese, Science Press, Beijing, 2008. [3] K. Q. He, J. Wang and P. Liang, “Semantic Interopera- bility Aggregation in Service Requirements Refinement,” Journal of Computer Science and Technology (JCST), Vol. 25, No. 6, 2010, pp. 1103-1117. doi:10.1007/ s11390-010-9392-3 [4] K. Q. He, P. Liang, J. Liu, et al., “Design Methodology of Networked Software Evolution Growth Based on Soft- ware Patterns,” Journal of System Science and Comple- xity, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2006, pp. 157-181. doi: 10.1007/ s11424-006-0157-6 [5] P. Liang, P. Avgeriou, K. Q. He and L. Xu, “From Collective Knowledge to Intelligence: Pre-Requirements Analysis of Large and Complex Systems,” Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Web 2.0 for Software Engineering (Web2SE),” Cape Town, 2010, pp. 26-30. [6] F. He, “Yoshiaki Fukazawa: Requirement Life Cycle and its Integrated Modeling Framework,” Special Issue on Software Engineering and Complex Networks, Dynamics of Continuous, Discrete and Impulsive Systems, Series B, Applications & Algorithms, Watam Press, Canada, Vol. 14(S6), 2007, pp. 227-232 [7] K. C. Kang, S. G. Cohen, J. A. Hess et al., “Feature- Oriented Domain Analysis (FODA) Feasibility Study,” Technical Report CMU/SEI-90-TR-21, Software Enginee- ring Institution, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, 1990. [8] K. C. Kang, J. Lee and P. Donohoe, “Feature-Oriented Product Line Engineering,” IEEE Software, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2002, pp. 58-65. doi:10.1109/MS.2002.1020288  A Method for Service-Oriented Personalized Requirements Analysis Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 68 [9] J. Mylopoulos, L. Chung and E. Yu, “From Object-Ori- ented to Goal-Oriented Requirements Analysis,” Commu- nications of the ACM, 1999, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 31-37. doi:10.1145/291469.293165 [10] A. Dardenne, A. van Lamsweerde and S. Fickas,” Goal- Directed Requirements Acquisition,” Science of Comput- er Programming, Vol. 20, 1993, pp. 3-50. doi:10.1016/ 0167-6423(93)90021-G [11] P. Bresciani, A. Perini, P. Giorgini, F. Giunchiglia and J. Mylopoulos, “Tropos: An Agent-Oriented Software De- velopment Methodology,” Autonomous Agents and Mul- ti-Agent Systems, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2004, pp. 203-236. doi:10. 1023/B:AGNT.0000018806.20944.ef [12] L. Penserini, A. Perini, A. Susi and J. Mylopoulos, “From Stakeholder Needs to Service Requirements,” Proceed- ings of International Workshop on Service-Oriented Computing: Consequences for Engineering Requirements (SOCCER’06) at 14th IEEE International Conference on Requirements Engineering (ICRE 2006), Minneapolis, 2006. [13] J. Cao, S. S. Zhang and M. L. Li, “A Goal Driven and Process Reuse Based Web Service Customization Mod- el,” Chinese Journal of Computers, In Chinese, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2005, pp. 721-730. [14] C. Rolland, C. Souveyet and C. BenAchour, “Guiding Goal Modeling Using Scenarios,” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, Vol. 24, No. 12, 1998, pp. 1055- 1071. doi:10.1109/32.738339 [15] Service Oriented Architectures for All (SOA4All). http://www.soa4all.eu/ [16] K. Q. He, Y. F. He, C. Wang, P. Liang and J. Liu. “Ontology & Meta-Modeling Theory and Methodology with Its Applications,” In Chinese, Science Press, Beijing, 2008. [17] W3C, OWL Web Ontology Language Overview, 2004. http://www.w3.org/TR/owl-features/ [18] W3C. OWL-S: Semantic Markup for Web Services, 2004. http://www.w3.org/Submission/ OWL-S/ [19] J. Wang, K. Q. He, P. Gong, C.Wang, R. Peng and B. Li, “RGPS: A Unified Requirements Meta-Modeling Frame for Networked Software,” Proceedings of Third Interna- tional Workshop on Advances and Applications of Pro- blem Frames (IWAAPF 2008) at 30th International Con- ference on Software Engineering (ICSE 2008), Leipzig, 2008, pp. 29-35. [20] Z. X. Sun, J. Wang, K. Q. He, S. J. Xiang and D. H. Yu, “A Model Transformation Method in Service-Oriented Domain Modeling,” Proceedings of 21st Australasian Software Engineering Conference (ASWEC 2010),” Auckland, 2010, pp. 107-116. doi:10.1109/ASWEC. 2010.32 |