Open Journal of Gastroenterology, 2013, 3, 259-266 OJGas http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojgas.2013.35044 Published Online September 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojgas/) Prognostic factors after palliative resection for colorectal cancer with incurable synchronous liver metastasis* Kiichi Sugimoto, Kazuhiro Sakamoto, Yuichi Tomiki, Michitoshi Goto, Yutaka Kojima, Hiromitsu Komiyama, Makoto Takahashi, Yukihiro Yaginuma, Shun Ishiyama, Koichiro Niwa, Kiichi Nagayasu, Shingo Ito, Masaya Kawai, Kazuhiro Takehara, Yoshihiko Tashiro, Shinya Munakata Department of Coloproctological Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan Email: ksugimo@juntendo.ac.jp Received 28 July 2013; revised 24 August 2013; accepted 31 August 2013 Copyright © 2013 Kiichi Sugimoto et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Purpose: With the improvements in newer chemo- therapeutic agents, there is currently no consensus regarding the validity of palliative resection of the primary tumor for colorectal cancer with incurable distant metastasis. We retrospectively analyzed prog- nostic factor in patients with colorectal cancer ac- companied by incurable synchronous liver metastasis. Methods: 82 patients with incurable synchronous liver metastases, who underwent primary tumor re- section alone, were enrolled. Results: The multivari- ate analysis revealed that the presence of ascites (P = 0.001, Hazard ratio = 2.96) and differentiation (P = 0.003, Hazard ratio = 3.68) were found to be signifi- cant independent prognostic factors. The median sur- vival time among the patients with ascites was 4.8 months and that among the patients with poorly-dif- ferentiated or mucinous adenocarcinoma, or signet ring cell carcinoma (high grade differentiation) was 1.4 months, respectively. Conclusion: The presence of ascites and differentiation were prognostic factors in the patients with incurable liver metastases. There- fore, because prognosis is generally poor after pri- mary tumor resection in the patients with ascites or high grade differentiation, the introduction of sys- temic chemotherapy with alleviation of symptoms re- lated to the primary tumor should be taken into ac- count as one of the therapeutic strategies. Keywords: Colorectal Carcinoma; Liver Metastasis; Primary Tumor Resection; Palliative Resection; Systemic Chemotherapy; Postoperative Morbidity 1. INTRODUCTION With the improvements in newer chemotherapeutic agents, there is currently no consensus regarding the validity of palliative resection of the primary tumor for colorectal cancer with incurable distant metastasis, be- cause there are many risks of postoperative mortality and morbidity due to highly-advanced tumor-bearing condi- tion [1,2]. Therefore, we determine whether or not re- section of the primary tumor should be performed, ac- cording to the symptom of the primary tumor, the status of distant metastasis and the patient’s status. In particular, in colorectal cancer patients with extensive metastatic lesions within the liver, the selection of a therapeutic strategy for the primary tumor is difficult because liver dysfunction, jaundice and ascites are occasionally seen preoperatively. This study was undertaken to retrospec- tively analyze the prognosis of primary tumor resection and its prognostic factor in patients with colorectal cancer accompanied by incurable synchronous liver me- tastasis and to identify patients requiring care in eva- luating the indication for primary tumor resection. 2. METHODS 2.1. Patient Selection Of the 1557 consecutive patients who underwent surgery for colorectal cancer at our department between Decem- ber 1998 and March 2009, 149 (9.6%) presented with synchronous colorectal liver metastases (Figure 1). In this study, synchronous metastases were defined as nodules that had been diagnosed before the primary colorectal surgery. The patients with synchronous color- ectal liver metastases were divided into two groups ac- cording to whether or not they underwent simultaneous curative liver resection for synchronous colorectal liver *Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts o interest. OPEN ACCESS  K. Sugimoto et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 259-266 260 Figure 1. Patient selection. metastases (n = 58; 38.9%, and n = 91; 61.1%, res- pectively). Among the patients with incurable synchro- nous liver metastases, 9 underwent colostomy or bypass alone. The remaining 82 patients who underwent primary tumor resection alone were enrolled in this study. Cases that underwent emergency operation or died of non- cancer-related causes were excluded from this study. None of the patients received preoperative adjuvant therapy. The median observation period was 13.9 months (range: 0.5 - 121.7 months) in all patients with incurable synchronous liver metastases. On the other hand, among the 56 patients who died of cancer during the observation period, the median survival period was 12.6 months (range: 0.5 - 45.9 months). With respect to the indication for liver resection in our hospital, there were no limi- tations regarding the number or size of liver metastases. In this series, liver resection was indicated for liver metastases when the following 3 conditions were met: 1) the primary tumor, liver metastases and extrahepatic dis- tant metastases were curatively resected; 2) liver func- tional reserve was likely to be acceptable after liver resection; 3) tolerance for operation was adequate. Pa- tients who did not meet these criteria only underwent surgery for the primary tumor (resection of the primary tumor, colostomy or bypass). With respect to the thera- peutic strategies for the patients with curable liver meta- stasis, we did not perform preoperative adjuvant chemo- therapy before liver resection for the patients with curable liver metastasis. The reason for this is that during the study period, preoperative systemic chemotherapy was not popular in Japan. In addition, tumor progression during preoperative chemotherapy could reduce the opportunity for liver resection and introduce a risk of liver dysfunction. Therefore, at our department we per- formed liver resection immediately after diagnosis. 2.2. Clinicopathological Analysis Clinicopathological factors, i.e., patient background, pre- operative laboratory data, intraoperative findings, patho- logical findings, postoperative factors and survival data were analyzed to determine prognostic factors related to the prognosis after primary tumor resection. For the pa- tient backgrounds, age, gender, symptoms, preoperative comorbidity, body mass index (BMI), performance status criteria outlined by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), location, extent of liver metastasis and extrahepatic distant metastasis were investigated. In the preoperative laboratory data, white blood cell (WBC), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotrans- ferase (ALT), total bilirubin (T-Bil), albumin (Alb), C- reactive protein (CRP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and Child classification were investigated. Among the intraoperative findings, ascites and peritoneal metastasis were investigated. Regarding the pathological findings, primary tumor diameter, differentiation, invasion depth, lymphatic invasion, venous invasion and lymph node metastasis were investigated. With respect to postopera- tive factors, postoperative complications and chemothe- rapy were investigated. 2.3. Statistical Analysis Survival was measured from the time of primary tumor resection, and death was the end point. The survival rate was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method accord- ing to each of the clinicopathological factors. Univariate analyses were performed using the log-rank test. Dif- ferences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. With regard to the clinicopathological factors for which there were statistically significant differences in the univariate analyses, mutual correlation coefficients (r) were calculated using Spearman rank correlation coefficient. When |r| was >0.6, a strong correlation was detected among the clinicopathological factors. Clinico- pathological factors that achieved lower P-values in the log-rank test were used as covariables for the multi- variate analysis. For the multivariate analysis, the Cox proportional-hazard model was used with the Hazard ratio. Data were statistically analyzed using JMP 9.0.2 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Values are expressed as the median (min. - max.). 3. RESULTS 3.1. Patient Characteristics The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 68 years (34 - 86 years). The most frequently encountered location was sigmoid colon in 25 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  K. Sugimoto et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 259-266 261 Table 1. Patient characteristics. No. of patients (%) Total 82 Age 68 years (34 - 86) Location Cecum 6 (7.3%) Ascending colon 11 (13.4%) Transverse colon 12 (14.6%) Descending colon 7 (8.5%) Sigmoid colon 25 (30.5%) Rectosigmoid 11 (13.4%) Rectum 10 (12.2%) Extrahepatic distant metastasisa Lung 21 (25.6%) Peritoneum 15 (18.3%) Para-aortic lymph node 3 (3.7%) Spleen 1 (1.2%) Bone 1 (1.2%) Postoperative complicationa Wound infection 12 (14.6%) Ileus 8 (9.8%) Anastomotic leakage 5 (6.1%) Intrapelvic abscess 5 (6.1%) DIC 4 (4.9%) Others 3 (3.7%) Postoperative chemotherapy FOLFOX/FOLFIRI 27 (32.9%) Transcatheter arterial infusion (TAI) 17 (20.7%) IV 5FU/LV 12 (14.6%) Others (oral administration etc.) 8 (9.8%) None 18 (22.0%) aWith some duplication. patients (30.5%). Extrahepatic distant metastases were lung metastasis in 21 patients (25.6%), peritoneal meta- stasis in 15 patients (18.3%), para-aortic lymph node metastasis in 3 patients (3.7%), spleen metastasis in one patient (1.2%) and bone metastasis in one patient (1.2%). Postoperative complications were recognized in 31 pa- tients (37.8%). The most frequently encountered post- operative complication was wound infection in 12 pa- tients (14.6%); followed by ileus in 8 patients (9.8%), anastomotic leakage in 5 patients (6.1%), intrapelvic abscess in 5 patients (6.1%), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in 4 patients (4.9%) and other in 3 patients (3.7%). Sixty-four patients (78.0%) underwent postoperative chemotherapy. The most frequently en- countered chemotherapy was FOLFOX or FOLFIRI in 27 patients (32.9%); followed by transcatheter arterial infusion (TAI) in 17 patients (20.7%), intravenous in- jection of 5FU/LV in 12 patients (14.6%), and other in 8 patients (9.8%). On the other hand, 18 patients (22.0%) received no chemotherapy because of poor general status or advanced age. 3.2. Prognostic Factors Related to the Outcome Comparisons of the survival rates according to clinico- pathological factors are shown in Tables 2-4. Significant differences in comparisons of survival rates were recog- nized in the extent of liver metastasis (P = 0.02), abnor- mal AST (P = 0.01), abnormal ALT (P = 0.001), ascites (P = 0.0001) and differentiation (P = 0.01). Next, with respect to these clinicopathological factors for which there were significant differences in the log- Table 2. Comparisons of the survival rates according to clini- copathological factors (1). Clinicopathological factors Variables No. of patients Median survival time (month) P-value 75≤ 17 14.3 Age <75 65 13.8 0.77 Male 48 15.7 Gender Female 34 13.5 0.79 + 60 13.1 Symptom − 22 19.9 0.19 + 60 13.2 Preoperative comorbidity − 22 15.1 0.59 25.0< 21 16.8 Body mass index (BMI) ≤25.0 61 13.1 0.96 0 47 15.7 Performance status 1, 2 35 9.1 0.87 Colon 72 13.9 Location Rectum 10 15.2 0.86 High 23 8.9 Extent of liver metastasisa Low 59 15.7 0.02 + 25 15.7 Extrahepatic distant metastasis b − 57 13.2 0.98 aHigh: five or more metastatic tumors at least one of which is more than 5 cm in maximum diameter, Low: except for high grade. bExcept for perito- neal metastasis. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  K. Sugimoto et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 259-266 262 Tab l e 3. Comparisons of the survival rates according to clini- copathological factors (2). Clinicopathological factors Variables No. of patients Median survival time (month) P-value 9000< 30 12.2 WBC (/mm3) ≤9000 52 14.7 0.80 37< 33 8.0 AST (IU/l) ≤37 49 15.7 0.01 43< 22 4.2 ALT (IU/l) ≤43 60 16.4 0.001 1.2< 10 6.2 T-Bil (mg/dl) ≤1.2 72 14.6 0.12 4.0≤ 17 19.7 Alb (g/dl) <4.0 65 13.2 0.08 0.3< 70 12.6 CRP (mg/dl) ≤0.3 12 17.9 0.16 3.0< 78 13.9 CEA (ng/dl) ≤3.0 4 14.0 0.06 A 58 15.7 Child classification B, C 24 10.2 0.07 Abbreviations: WBC: White blood cell, AST: Aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: Alanine aminotransferase, T-Bil: Total bilirubin, Alb: Albumin, CRP: C-reactive protein, CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen. Table 4. Comparisons of the survival rates according to clini- copathological factors (3). Clinicopathological factors Variables No. of patients Median survival time (month) P-value + 25 4.8 Ascites − 57 16.8 0.0001 + 15 9.1 Peritoneal metastasis − 67 14.9 0.11 50< 51 14.0 Primary tumor diameter (mm) ≤50 31 13.8 0.28 Low gradea 73 14.3 Differentiation High gradeb 9 1.4 0.01 T3 27 15.9 Invasion depth T4 55 12.0 0.17 + 75 13.8 Lymphatic invasion − 7 17.8 0.61 + 79 13.8 Venous invasion − 3 16.8 0.87 + 71 13.4 Lymph node metastasis − 11 16.0 0.61 + 31 13.2 Postoperative complication − 51 14.3 0.91 + 27 17.8 Chemotherapy with novel agents c − 37d 14.9 0.62 aWell- and moderately-differentiated adenocarcinoma; bPoorly-differentiated or mucinous adenocarcinoma or signet ring cell carcinoma; cPostoperative chemotherapy with novel agents, such as oxaliplatin or irinotecan; dExcept for the patients without chemotherapy due to poor general status. rank test, mutual correlation coefficients were calculated using Spearman rank correlation coefficient (Table 5). As a result, a strong correlation between abnormal AST and abnormal ALT was recognized (r = 0.626). Because there was a lower P-value for abnormal ALT compared with the abnormal AST, four clinicopathological factors except for abnormal AST were used as co-variables for the multivariate analysis. Consequently, the presence of ascites (P = 0.001, Hazard ratio = 2.96) and differentia- tion (P = 0.003, Hazard ratio = 3.68) were found to be significant independent prognostic factors (Table 6). Comparisons of the cumulative survival rates accord- ing to the prognostic factors are shown in Figure 2. The median survival time among the patients with ascites was 4.8 months and that among the patients with poorly-dif- ferentiated or mucinous adenocarcinoma, or signet ring cell carcinoma (high grade differentiation) was 1.4 months, respectively. Therefore, it was shown that the prognosis among the patients with these prognostic factors was poor. 4. DISCUSSION The liver is the most common organ of distant metastases from colorectal cancer and the incidence of synchronous liver metastases in colorectal cancer has been reported to be 13% - 25% [3-5]. Surgical resection is the most effec- tive therapy for liver metastases and it has been reported that the 5-year survival rate after liver resection in pa- Figure 2. Comparision of the cumulative survival rate accord- ing to the prognostic factors. (a) Ascites; (b) Differentiation. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  K. Sugimoto et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 259-266 263 Table 5. Correlation coefficients among clinicopathological factors using Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Extent of liver metastasis AST ALT Ascites Differentiation Extent of liver metastasis - 0.539 0.418 0.235 0.128 AST - 0.626 0.213 0.189 ALT - 0.316 0.228 Ascites - 0.107 Differentiation - Table 6. Prognostic factors related to the outcome using Cox’s proportional hazards model. Prognostic factor P-value Hazard ratio 95% confidence interval Extent of liver metastasis (High) 0.13 1.59 0.87 - 2.89 ALT (>43IU/l ) 0.06 1.87 0.98 - 3.57 Ascites (+) 0.001 2.96 1.55 - 5.64 Differentiation (High gradea) 0.003 3.68 1.55 - 8.71 aPoorly-differentiated or mucinous adenocarcinoma or signet ring cell car- cinoma. tients with synchronous liver metastases is 19% - 38%, and that the prognosis of the patients with resectable syn- chronous liver metastases is better than for those with non-resectable liver metastases [6-9]. However, up to 70% - 80% of these patients have incurable disease, so the proportion of the patients with incurable liver metas- tases is greater than that of the patients with curable liver metastases [10-12]. On the other hand, due to recent ad- vances in systemic chemotherapy, the prognosis of the patients with distant metastases has been improved re- markably [13,14]. Therefore, it would appear that there is a possibility that the patients with incurable liver me- tastases could achieve a relatively good prognosis by systemic chemotherapy instead of primary tumor resec- tion [15,16]. Thus it is important to identify the patients with a poor prognosis who are unlikely to enjoy the benefits of primary tumor resection. Therefore, we ret- rospectively investigated the prognosis of primary tumor resection in patients with incurable synchronous liver metastasis and analyzed prognostic factors related to the prognosis. With respect to the prognosis after primary tumor resection in the patients with incurable distant metastases, some authors have reported median survival periods of 7.0 - 30.0 months [1,17-19] and mean survival periods of 10.6 - 13.9 months [2,20,21]. In this study the subjects were limited to the patients with incurable liver meta- stases, and consequently, the median survival period was 13.9 months. Because it is generally expected that the prognosis is poor in the patients with highly-advanced tumor-bearing condition, the identification of prognostic factors could possibly help us to decide the indication for operation. Only the presence of ascites and differentiation were prognostic factors in the patients with incurable liver metastases. The patient backgrounds and the extent of primary tumor and liver metastases were not prognostic factors in this study. In addition to this study, there has been a report that the presence of ascites was associated significantly with the prognosis [19]. The report con- cluded that the presence of ascites reflected a highly- advanced tumor-bearing condition. Because we studied patients with incurable synchronous liver metastasis, it was considered that there was likely to be liver dys- function due to extensive metastatic lesions within the liver or undernutrition due to the highly-advanced tumor- bearing underlying state of the patients with ascites and that this might significantly affect the prognosis. With regard to differentiation of the primary tumor, some authors have reported that the prognosis among patients with high grade differentiation was significantly poorer than that with well- and moderately-differentiated adeno- carcinoma [21-24]. The prognosis was extremely poor in this study, which suggested that differentiation also provided useful prognostic information among patients who underwent non-curative resection. Therefore, it is thought that the patients with high grade differentiation are unlikely to enjoy the benefits of primary tumor resection. The extent of liver metastases was not an independent prognostic factor in a multivariate analysis. Previously, Katoh et al. [25] reported that the extent of liver meta- stases was a significant independent factor in multi- variate analysis using the JCCC (Japanese Classification of Colorectal Cancer) staging system [26]. With respect to the extent of liver metastases, there was a significant difference in a univariate analysis, however, it was not a significant independent factor in the multivariate analysis conducted in this study. The reason for this was con- sidered that the criteria for incurable liver metastases included the resectability of extrahepatic distant meta- stases and general status in this study. Therefore, if the investigation was conducted with only the patients in whom liver metastasis itself was unresectable, it is be- lieved that the extent of liver metastases would be a prognostic factor for outcome. However, because in cli- nical practice there are many patients who cannot un- dergo liver resection due to the presence of unresectable extrahepatic distant metastases and poor general status, these patients were included in this study. In the patients with postoperative complications after Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  K. Sugimoto et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 259-266 264 curative resection of colorectal carcinoma, long-term survival is poor [27-29]. We investigated whether or not postoperative complications after primary tumor resec- tion were determinants of prognosis among the patients with incurable liver metastases. Some authors have re- ported that the incidence of postoperative complications among the patients with incurable liver metastases was 18.3% - 23.9% [2,19]. In this study, the incidence of postoperative complications was 37.8%, which was higher than previous reports. There was no significant differ- ence in long-term survival between the patients with or without postoperative complications. It has been demon- strated that postoperative complications could lead to a period of immunosuppression, resulting in proliferation of free tumor cells and occult malignant cells that would worsen the prognosis [27,30]. However, because the re- sidual metastatic lesions themselves strongly affect prog- nosis among the patients with incurable liver metastases, it was thought that the effects based on the presence of postoperative complications were small. Furthermore, there were no deaths related to grave postoperative com- plications and there were no patients who required re- operation. However, the incidence of grave postoperative complications could lower the quality of life among the patients and delay the introduction of systemic chemo- therapy [31]. Prognosis can be improved through efforts to reduce postoperative complications. Some authors have reported that 76.0% - 79.0% of the patients with incurable liver metastases underwent chemo- therapy after primary tumor resection, which was equi- valent to this study. These reports concluded that the introduction of chemotherapy after primary tumor resec- tion was a significant prognostic factor and was impor- tant in order to improve the prognosis. However, there were some patients to whom chemotherapy could not be introduced because their general status was poor after the primary tumor resection. 22.0% of the patients were also unable to receive chemotherapy in this study. Therefore, it must be considered there was a bias that the patients who were able to receive chemotherapy after primary tumor resection had a good general status. In addition, we compared outcomes between the patients who re- ceived chemotherapy with novel agents, such as oxali- platin or irinotecan and those who received chemo- therapy with other regimen. In this study, the proportion of the patients who received chemotherapy with novel agents after primary tumor resection was 32.9%, while the proportion treated with oxaliplatin was 27.5% in the previous report [32]. The median survival time among the patients who received chemotherapy with novel agents was longer than that for the others, but there was no significant difference between the two groups. It was supposed the reason for this is that the patient back- grounds, i.e., the extent of extrahepatic distant metastasis and the regimens of chemotherapy after the primary tumor resection, were varied, because this study was retrospective in nature. Recently, with the improvements in systemic chemo- therapy, some authors have reported that non-operative management by systemic chemotherapy with novel agents and molecular target drugs was recommended for patients who had relatively asymptomatic colorectal can- cer with incurable distant metastases [17,33,34]. It was reported that when the patients who had relatively asymptomatic colorectal cancer with incurable distant metastases underwent FOLFOX or FOLFIRI treatment, not only metastatic lesions but also primary tumor could be well controlled and the rate of complications related to the non-resected primary tumor was very low. How- ever, because these reports had a small number of pa- tients, further investigations with larger numbers of pa- tients will be needed. Therefore, because prognosis is generally poor after primary tumor resection in the pa- tients with ascites or high grade differentiation, the intro- duction of systemic chemotherapy with alleviation of symptoms related to the primary tumor should be taken into account as one of the therapeutic strategies. REFERENCES [1] Temple, L.K., Hsieh, L., Wong, W.D., Saltz, L. and Schrag, D. (2004) Use of surgery among elderly patients with stage IV colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical On- cology, 22, 3475-3484. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.10.218 [2] Costi, R., Di Mauro, D., Veronesi, L., Ardizzoni, A., Salcuni, P., Roncoroni, L., Sarli, L. and Violi, V. (2011) Elective palliative resection of incurable stage IV colo- rectal cancer: Who really benefits from it? Surgery Today, 41, 222-229. doi:10.1007/s00595-009-4253-9 [3] Nordlinger, B., Quilichini, M.A., Parc, R., Hannoun, L., Delva, E. and Huguet, C. (1987) Hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases. Influence on survival of pre- operative factors and surgery for recurrences in 80 pa- tients. Annals of Surgery, 205, 256-263. doi:10.1097/00000658-198703000-00007 [4] Cady, B., Monson, D.O. and Swinton, N.W. (1970) Sur- vival of patients after colonic resection for carcinoma with simultaneous liver metastases. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, 131, 697-700. [5] Blumgart, L.H. and Allison, D.J. (1982) Resection and embolization in the management of secondary hepatic tumors. World Journal of Surgery, 6, 32-45. doi:10.1007/BF01656371 [6] Santibanes, E., Lassalle, F.B., McCormack, L., Pekoli, J., Quintana, G.O., Vaccaro, C. and Benati, M. (2002) Si- multaneous Colorectal and hepatic resections for colo- rectal cancer: Postoperative and longterm outcomes. Jour- nal of the American College of Surgeons, 195, 196-202. doi:10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01235-8 [7] Wang, X., Hershman, D.L., Abrams, J.A., Feingold, D., Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  K. Sugimoto et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 259-266 265 Grann, V.R., Jacobson, J.S. and Neugut, A.I. (2007) Pre- dictors of survival after hepatic resection among patients with colorectal liver metastasis. British Journal of Cancer, 97, 1606-1612. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604093 [8] Sakamoto, Y., Fujita, S., Akasu, T., Nara, S., Esaki, M., Shimada, K.., Yamamoto, S., Moriya, Y. and Kosuge, T. (2010) Is Surgical resection justified for stage IV colo- rectal cancer patients having bilobar hepatic metastases? An analysis of survival of 77 patients undergoing hepa- tectomy. Journal of Surgical Oncology, 102, 784-788. doi:10.1002/jso.21721 [9] Fujita, S., Akasu, T. and Moriya, Y. (2000) Resection of synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 7-11. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyd002 [10] Fong, Y., Fortner, J., Sun, R.L., Brennan, M.F. and Blumgart, L.H. (1999) Clinical score for predicting re- currence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: Analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Annals of Surgery, 230, 309-318. doi:10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004 [11] Adam, R., Pascal, G., Azoulay, D., Tanaka, K., Castaing, D. and Bismuth, H. (2003). Liver resection for colorectal metastases: The third hepatectomy. Annals of Surgery, 238, 871-883. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000098112.04758.4e [12] Petrelli, N.J., Abbruzzese, J., Mansfield, P. and Minsky, B. (2005) Hepatic resection: The last surgical frontier for colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 4475-4477. [13] Hurwitz, H., Fehrenbacher, L., Novotny, W., Cartwright, T., Hainsworth, J., Heim, W., Berlin, J., Baron, A., Griff- ing, S., Holmgren, E., Ferrara, N., Fyfe, G., Rogers, B., Ross, R. and Kabbinavar, F. (2004) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic co- lorectal cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 350, 2335-2342. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032691 [14] Wolpin, B.M. and Mayer, R.J. (2008) Systemic treatment of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology, 134, 1296-1310. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.098 [15] Muratore, A., Zorzi, D., Bouzari, H., Amisano, M., Mas- succo, P., Sperti, E. and Capussotti, L. (2007) Asympto- matic colorectal cancer with un-resectable liver metasta- ses: Immediate colorectal resection or up-front systemic chemotherapy? Annals of Surgical Oncology, 14, 766- 770. doi:10.1245/s10434-006-9146-1 [16] Stillwell, A.P., Ho, Y.H. and Veitch, C. (2011) Systemic review of prognostic factors related to overall survival in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer and unresectable metastases. World Journal of Surgery, 35, 684-692. doi:10.1007/s00268-010-0891-8 [17] Makela, J., Haukipuro, K., Laitinen, S. and Kairaluoma, M.I. (1990) Palliative operations for colorectal cancer. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 33, 846-850. doi:10.1007/BF02051920 [18] Nash, G.M., Saltz, L.B., Kemeny, N.E., Minsky, B., Sharma, S., Schwartz, G.K., Ilson, D.H., O’Reilly, E., Kelsen, D.P., Nathanson, D.R., Weiser, M., Guillem, J.G., Wong, W.D., Cohen, A.W. and Paty, P.B. (2002) Radical resection of rectal cancer primary tumor provides effec- tive local therapy in patients with stage IV disease. An- nals of Surgical Oncology, 9, 954-960. doi:10.1007/BF02574512 [19] Law, W.L., Chan, W.F., Lee, Y.M. and Chu, K.W. (2004) Non-curative surgery for colorectal cancer: Critical ap- praisal of outcomes. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 19, 197-202. doi:10.1007/s00384-003-0551-7 [20] Joffe, J. and Gordon, P.H. (1981) Palliative resection for colorectal carcinoma. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 24, 355-360. doi:10.1007/BF02603417 [21] Liu, S.K., Church, J.M., Lavery, I.C. and Fazio, V.W. (1997) Operation in patients with in curable colon can- cer—Is it worthwhile? Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 40, 11-14. doi:10.1007/BF02055675 [22] Harris, G.J., Senagore, A.J., Lavery, I.C., Church, J.M. and Fazio, V.W. (2002) Factors affecting survival after palliative resection of colorectal carcinoma. Colorectal Disease, 4, 31-35. doi:10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00304.x [23] Chafai, N., Chan, C.L., Bokey, E.L., Dent, O.F., Sinclair, G. and Chapuis, P.H. (2005) What factors influence sur- vival in patients with unresected synchronous liver me- tastases after resection of colorectal cancer? Colorectal Disease, 7, 176-181. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00744.x [24] Yun, H.R., Lee, W.Y., Lee, W.S., Cho, Y.B., Yun, S.H. and Chun, H.K. (2007) The prognostic factors of stage IV colorectal cancer and assessment of proper treatment ac- cording to the patient’s status. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 22, 1301-1310. doi:10.1007/s00384-007-0315-x [25] Katoh, H., Yamashita, K., Kokuba, Y., Satoh, T., Ozawa, H., Hatate, K., Ihara, A., Nakamura, T., Onosato, W. and Watanabe, M. (2008) Surgical resection of stage IV co- lorectal cancer and prognosis. World Journal of Surgery, 32, 1130-1137. doi:10.1007/s00268-008-9535-7 [26] Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (2009) Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma. 2nd English Edition, Kanehara & Co. Ltd., Tokyo, 7-10. [27] Law, W.L., Choi, H.K., Lee, Y.M. and Ho, J.W. (2007) The impact of postoperative complications on long-term outcomes following curative resection for colorectal can- cer. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 14, 2559-2566. doi:10.1245/s10434-007-9434-4 [28] McArdle, C.S., Mcmillan, D.C. and Hole, D.J. (2005) Impact of anastomotic leakage on long-term survival of patients undergoing curative resection for colorectal can- cer. British Journal of Surgery, 92, 1150-1154. doi:10.1002/bjs.5054 [29] Law, W.L., Choi, H.K., Lee, Y.M., Ho, J.W. and Seto, C.L. (2007) Anastomotic leakage is associated with poor long-term outcome in patients after curative colorectal resection for malignancy. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, 11, 8-15. doi:10.1007/s11605-006-0049-z [30] Mynster, T., Christensen, I.J., Moesgaard, F. and Nielsen, H.J. (2000) Effects of the combination of blood transfu- sion and postoperative infectious complications on prog- nosis after surgery for colorectal cancer. Danish RANX05 Colorectal Cancer Study Group. British Journal of Sur- gery, 87, 1553-1562. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  K. Sugimoto et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 259-266 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 266 OPEN ACCESS doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01570.x [31] Kleespies, A., Fuessl, K.E., Seeliger, H., Eichhorn, M.E., Müller, M.H., Rentsch, M., Thasler, W.E., Angele, M.K., Kreis, M.E. and Jauch, K.W. (2009) Determinants of mor- bidity and survival after elective non-curative resection of stage IV colon and rectal cancer. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 24, 1097-1109. doi:10.1007/s00384-009-0734-y [32] Vibert, E., Bretagnol, F., Alves, A., Pocard, M., Valleur, P. and Panis, Y. (2007) Multivariate analysis of predic- tive factors for early postoperative death after colorectal surgery in patients with colorectal cancer and synchro- nous unresectable liver metastases. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 50, 1776-1782. doi:10.1007/s10350-007-9025-2 [33] Benoist, S., Pautrat, K., Mitry, E., Rougier, P., Penna, C. and Nordlinger, B. (2005) Treatment strategy for patients with colorectal cancer and synchronous irresectable liver metastases. British Journal of Surgery, 92, 1155-1160. doi:10.1002/bjs.5060 [34] Poultsides, G.A., Servais, E.L., Saltz, L.B., Patil, S., Ke- meny, N.E., Guillem, J.G., Weiser, M., Temple, L.K., Wong, W.D. and Paty, P.B. (2009) Outcome of primary tumor in patients with synchronous stage IV colorectal cancer receiving combination chemotherapy without sur- gery as initial treatment. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27, 3379-3384. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9817

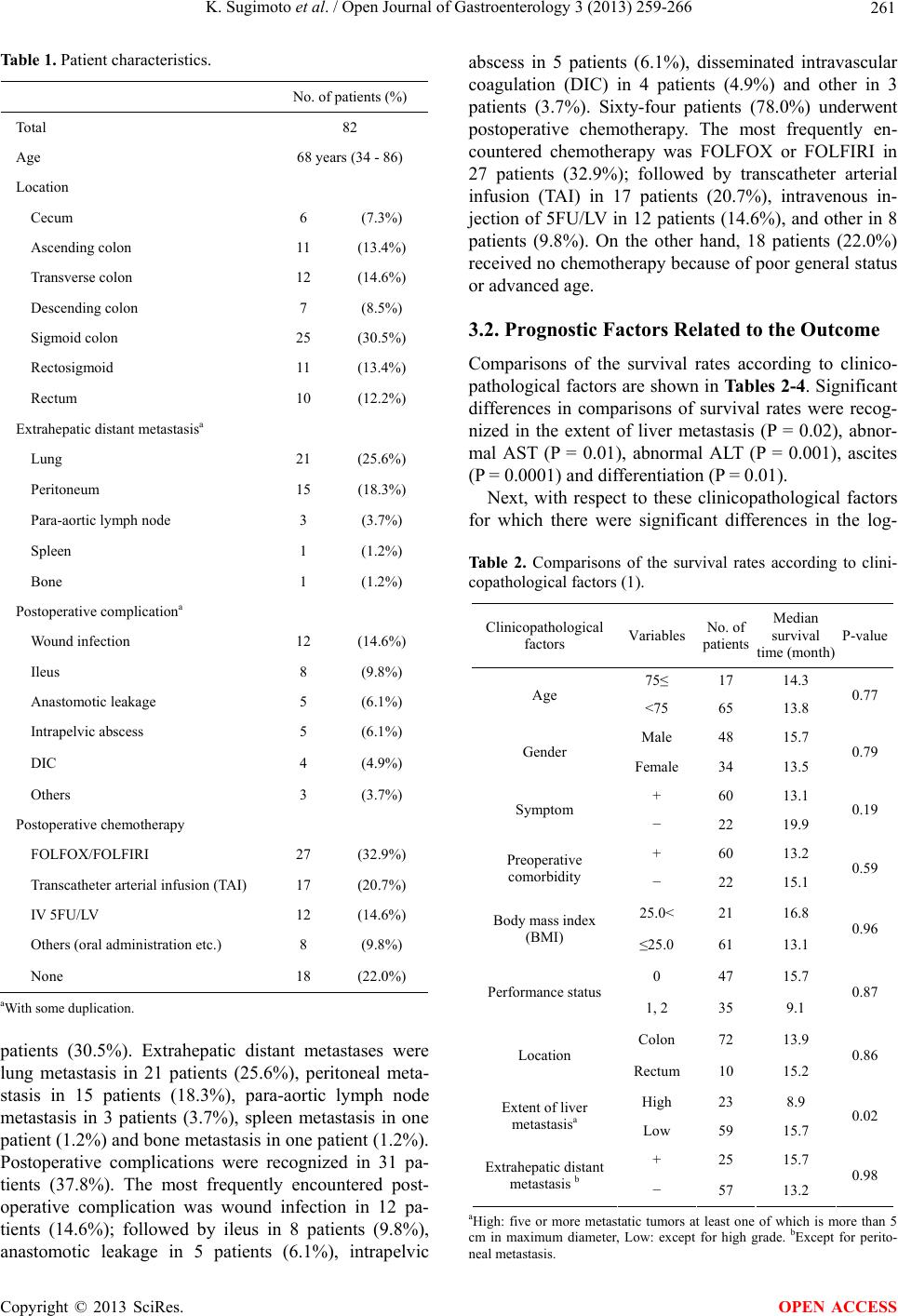

|