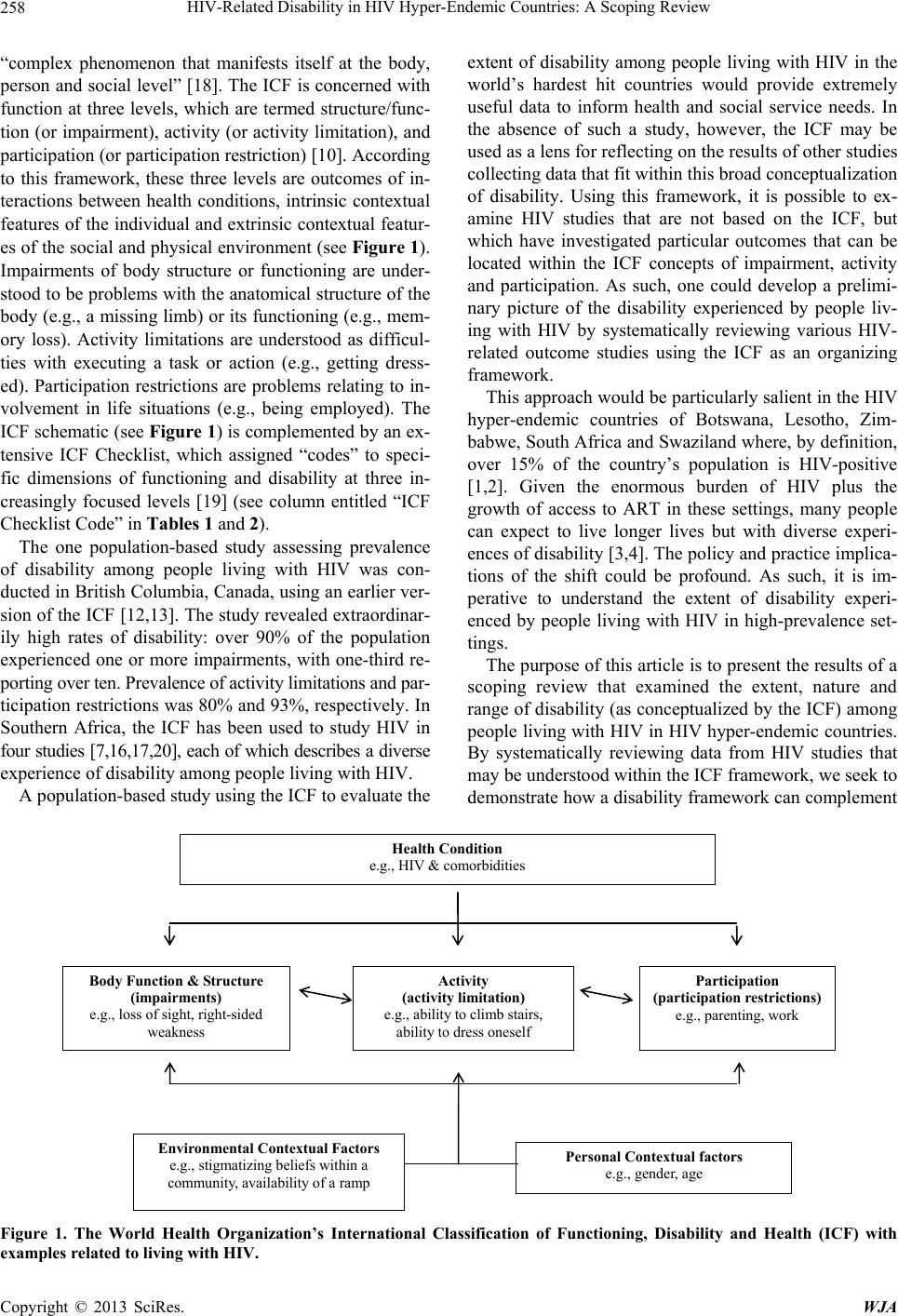

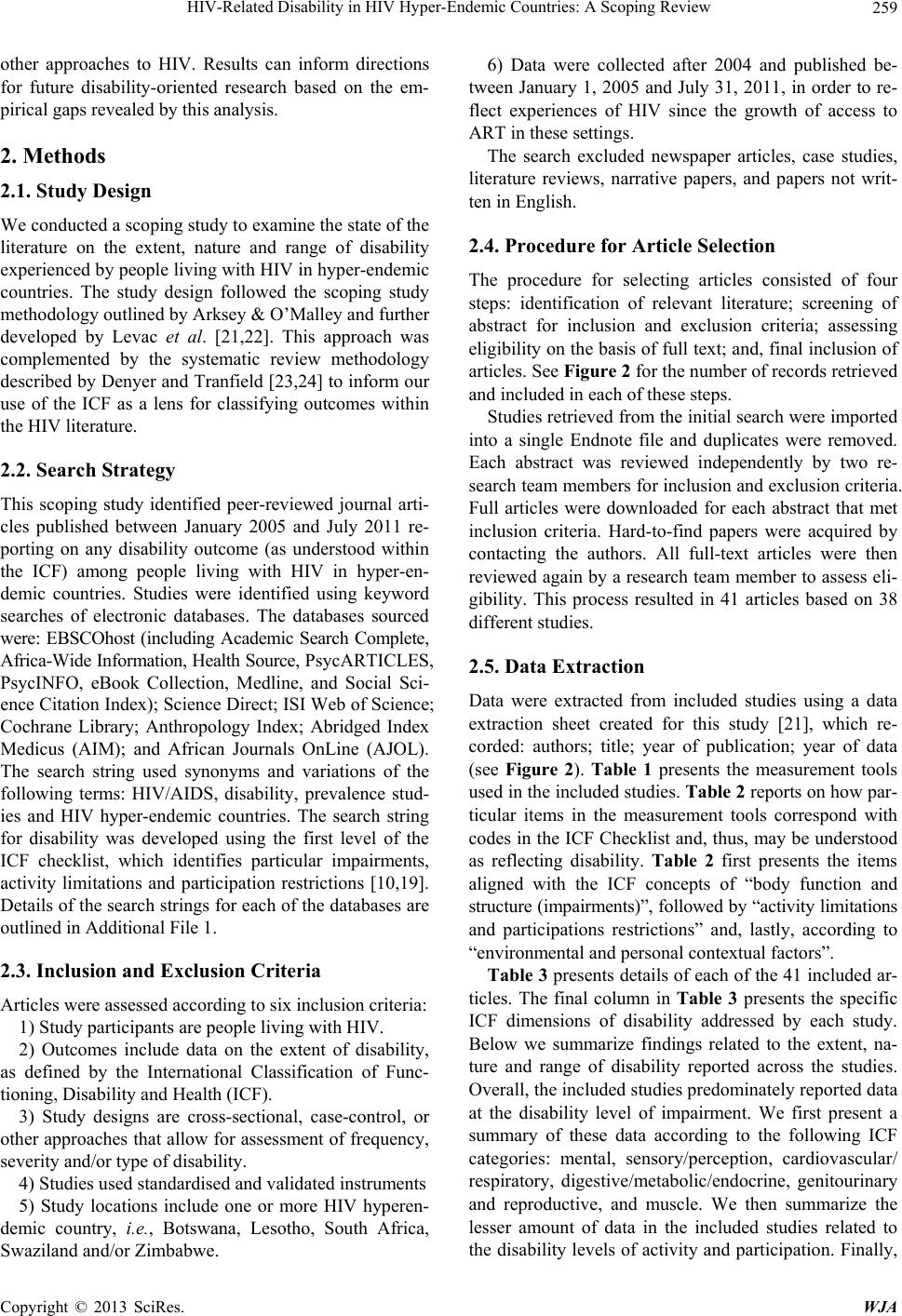

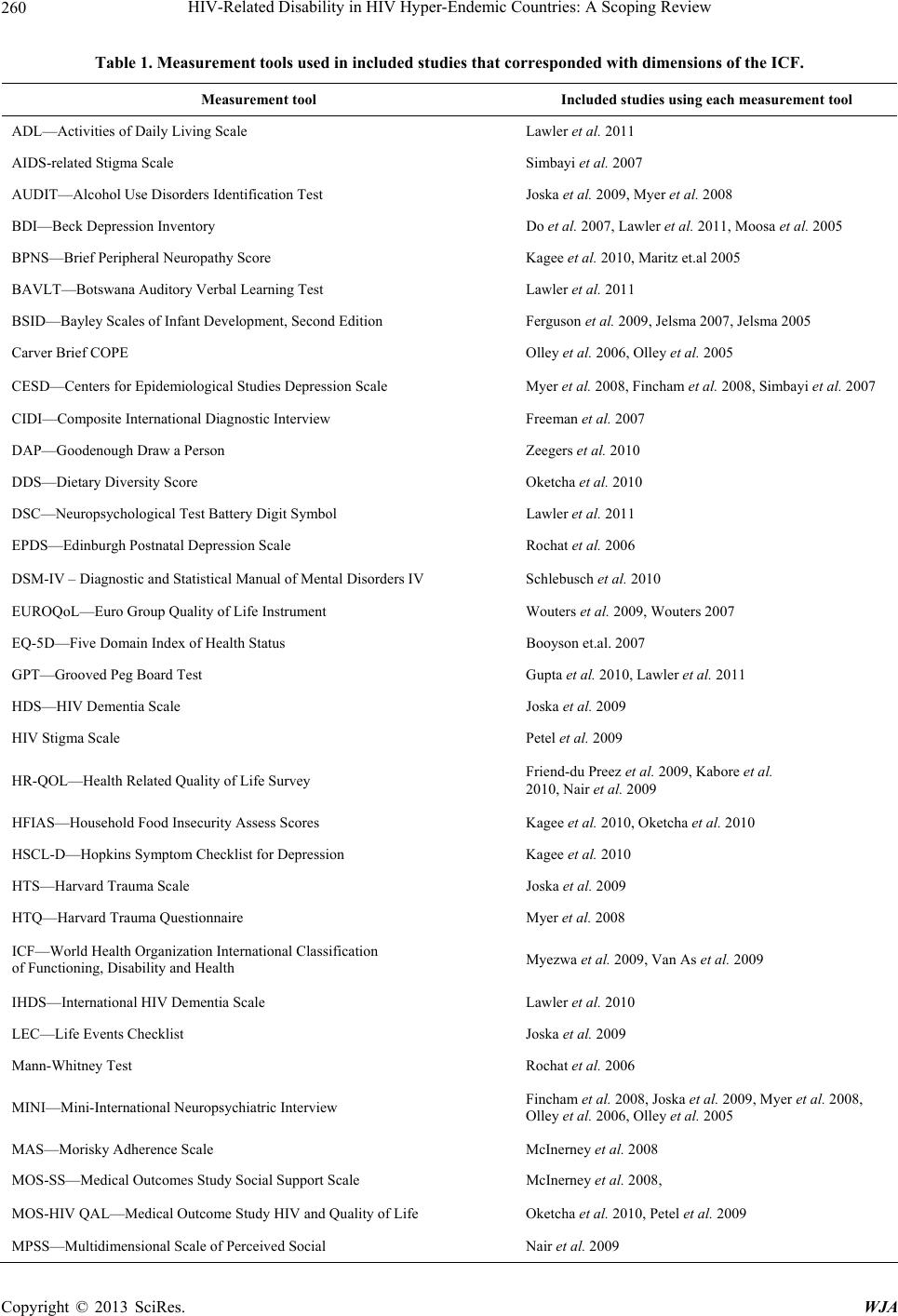

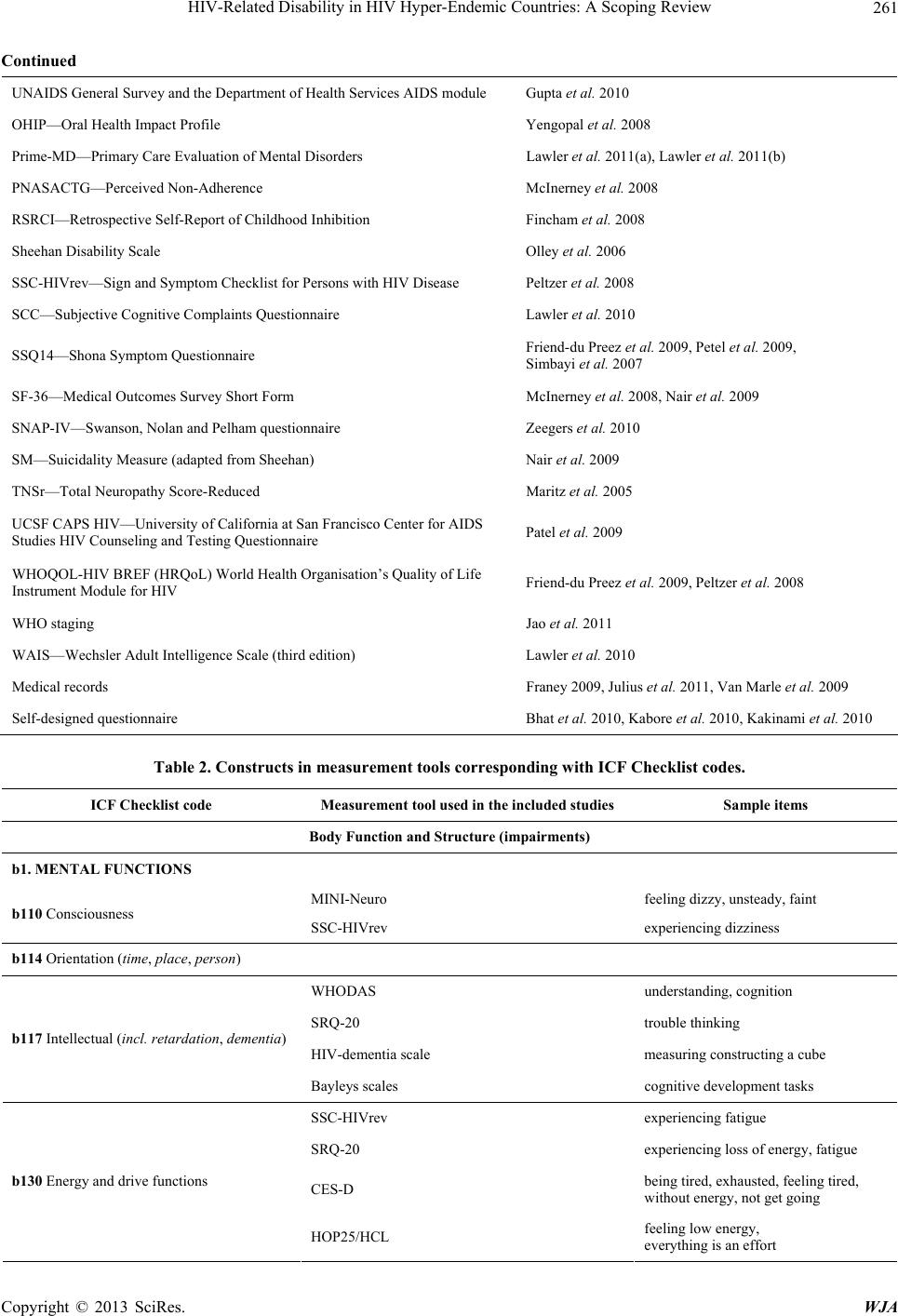

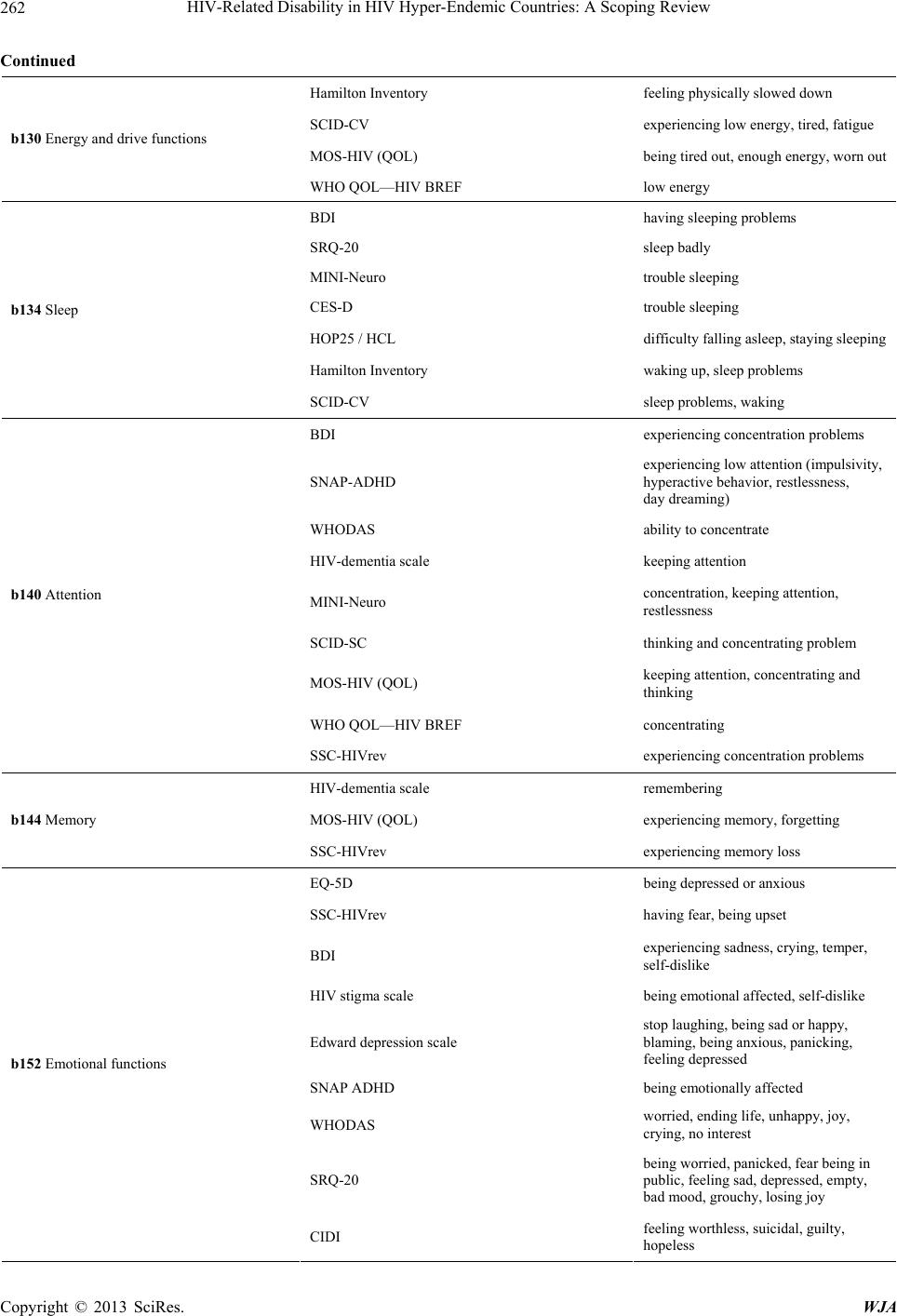

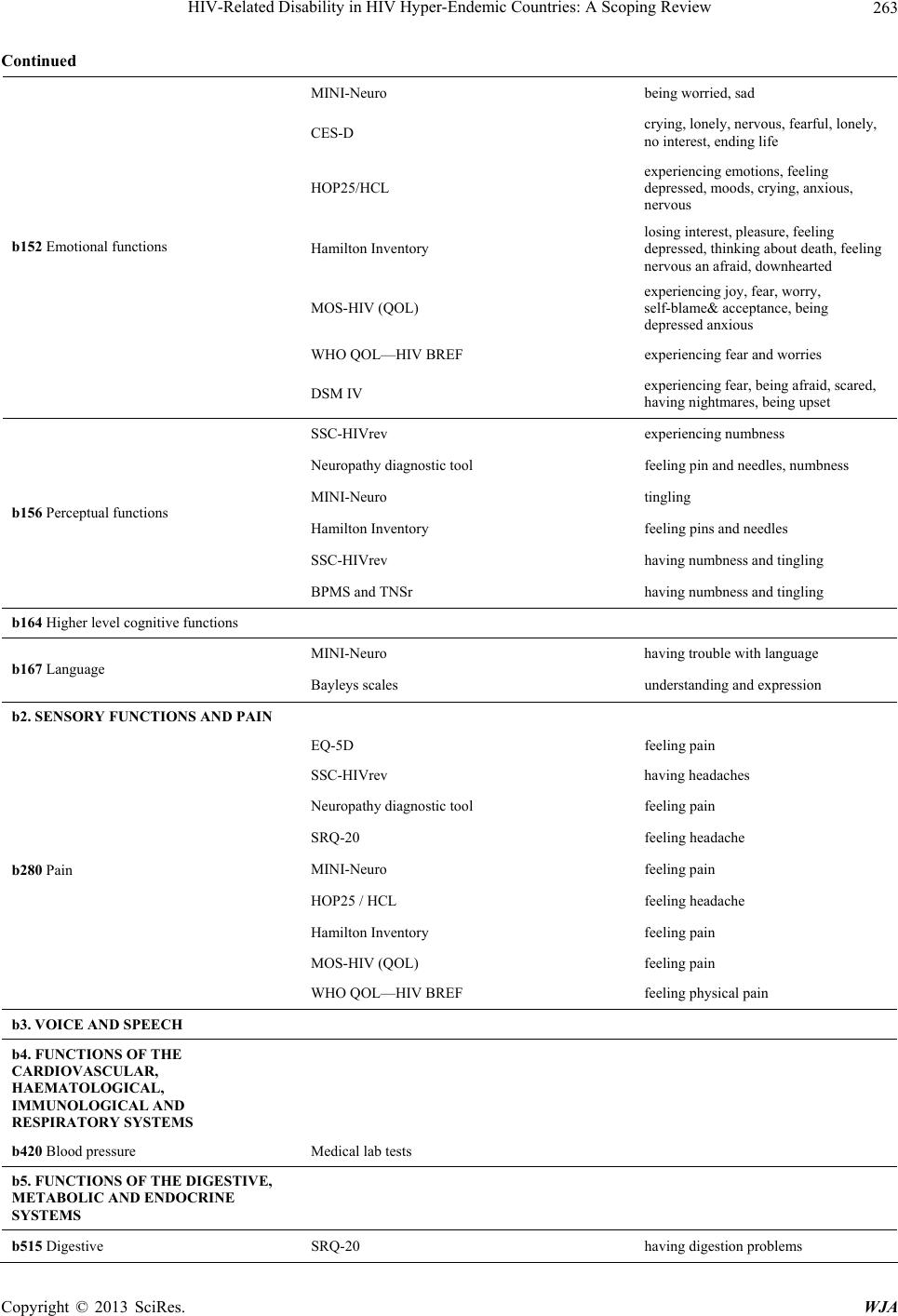

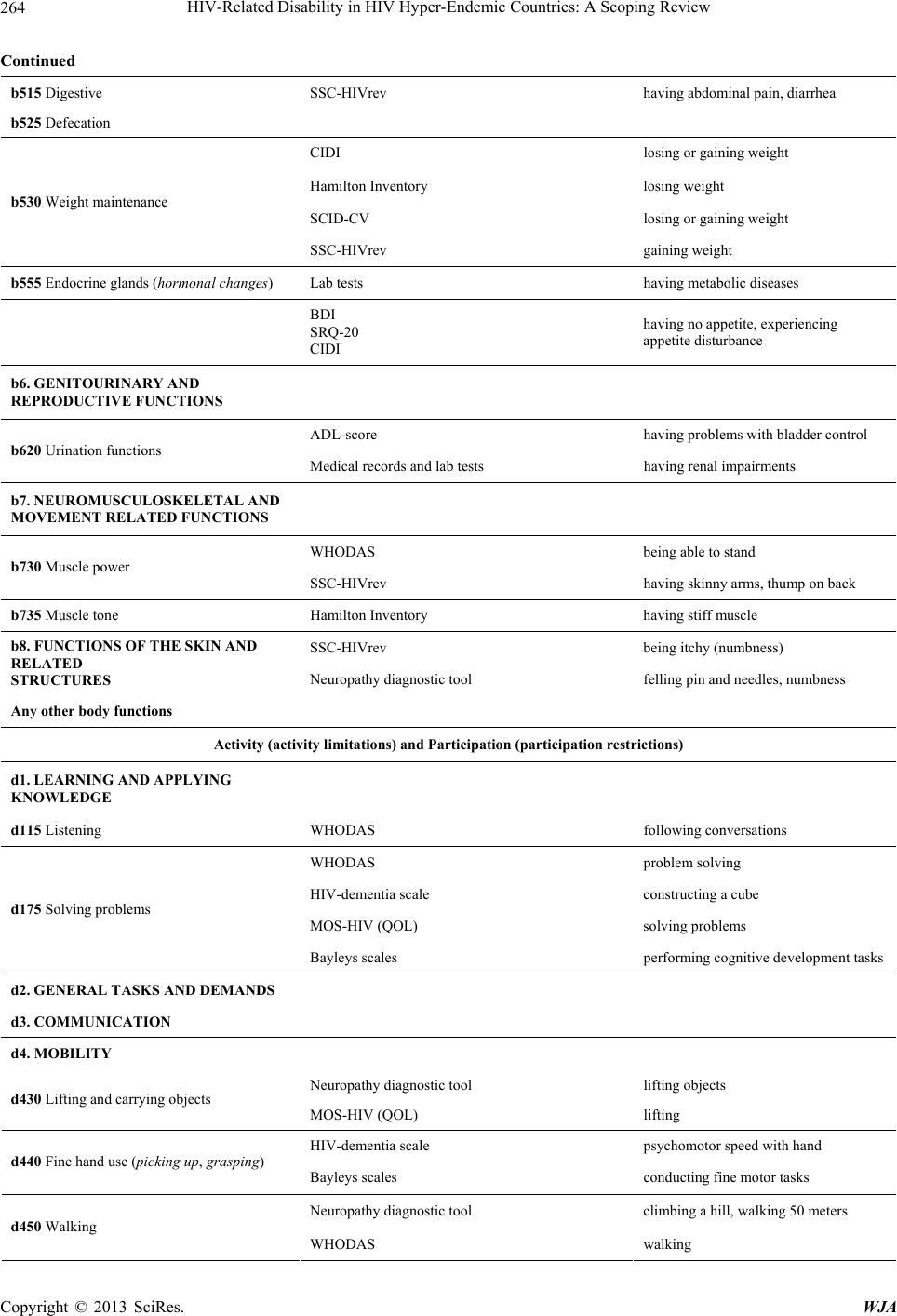

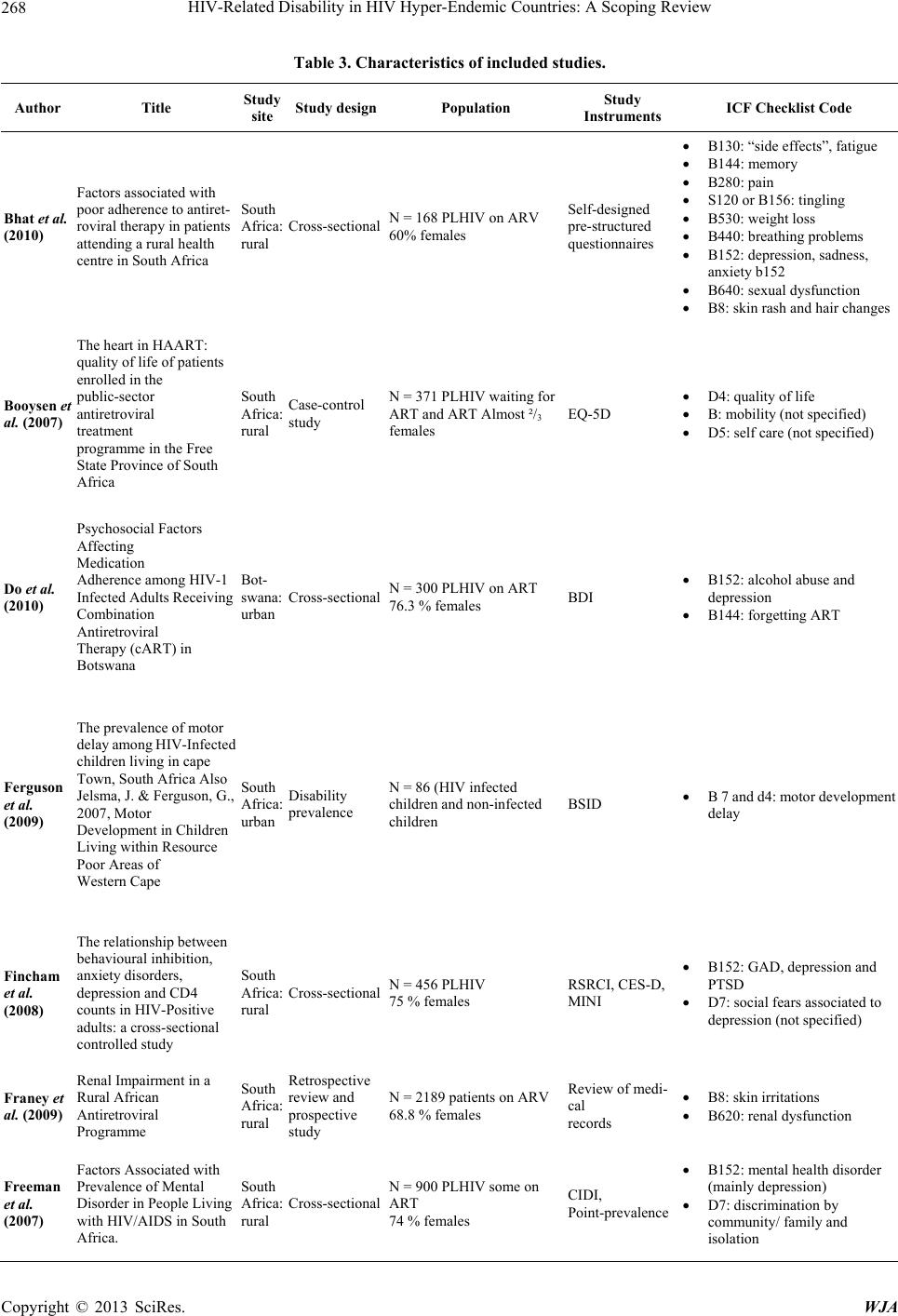

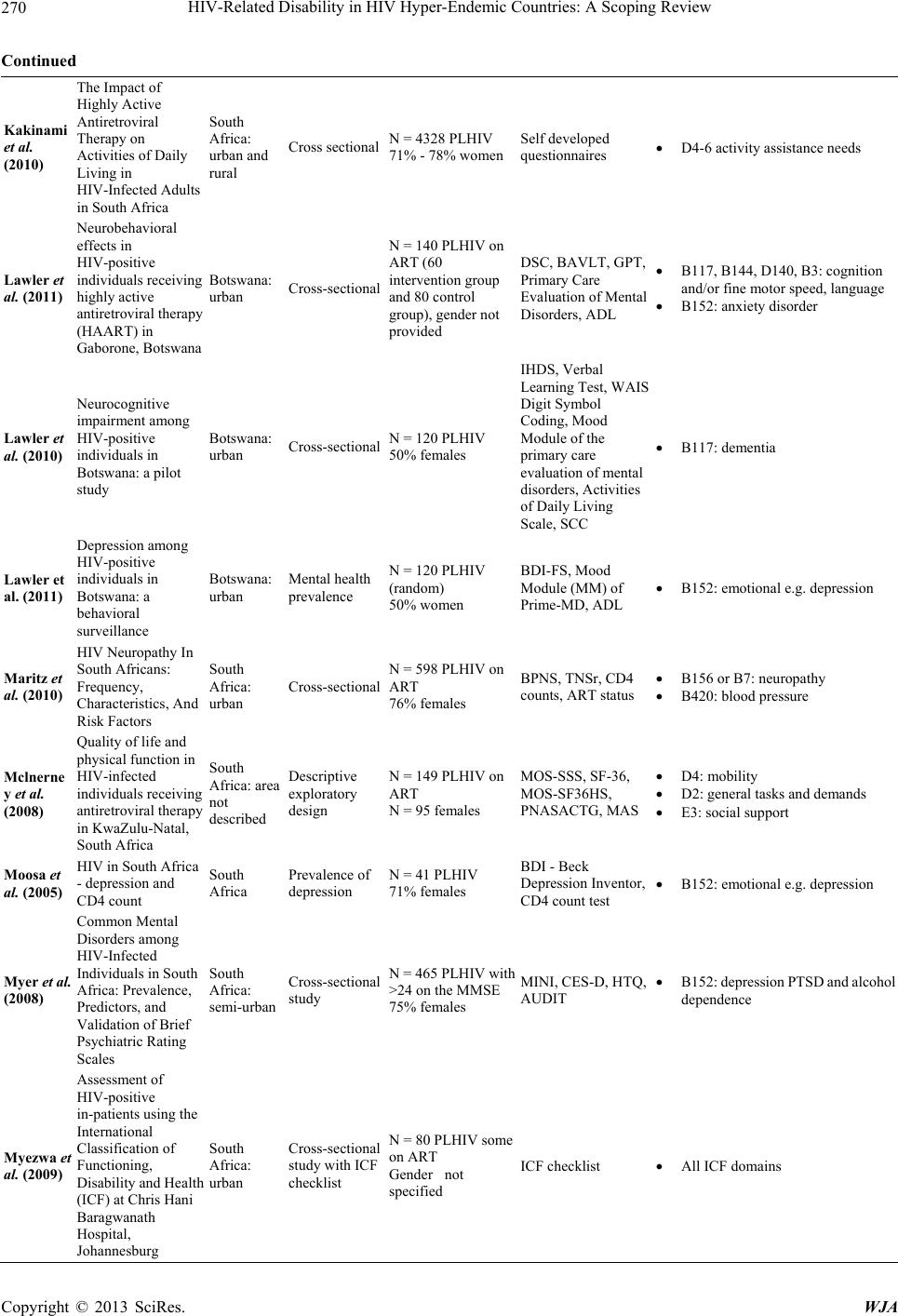

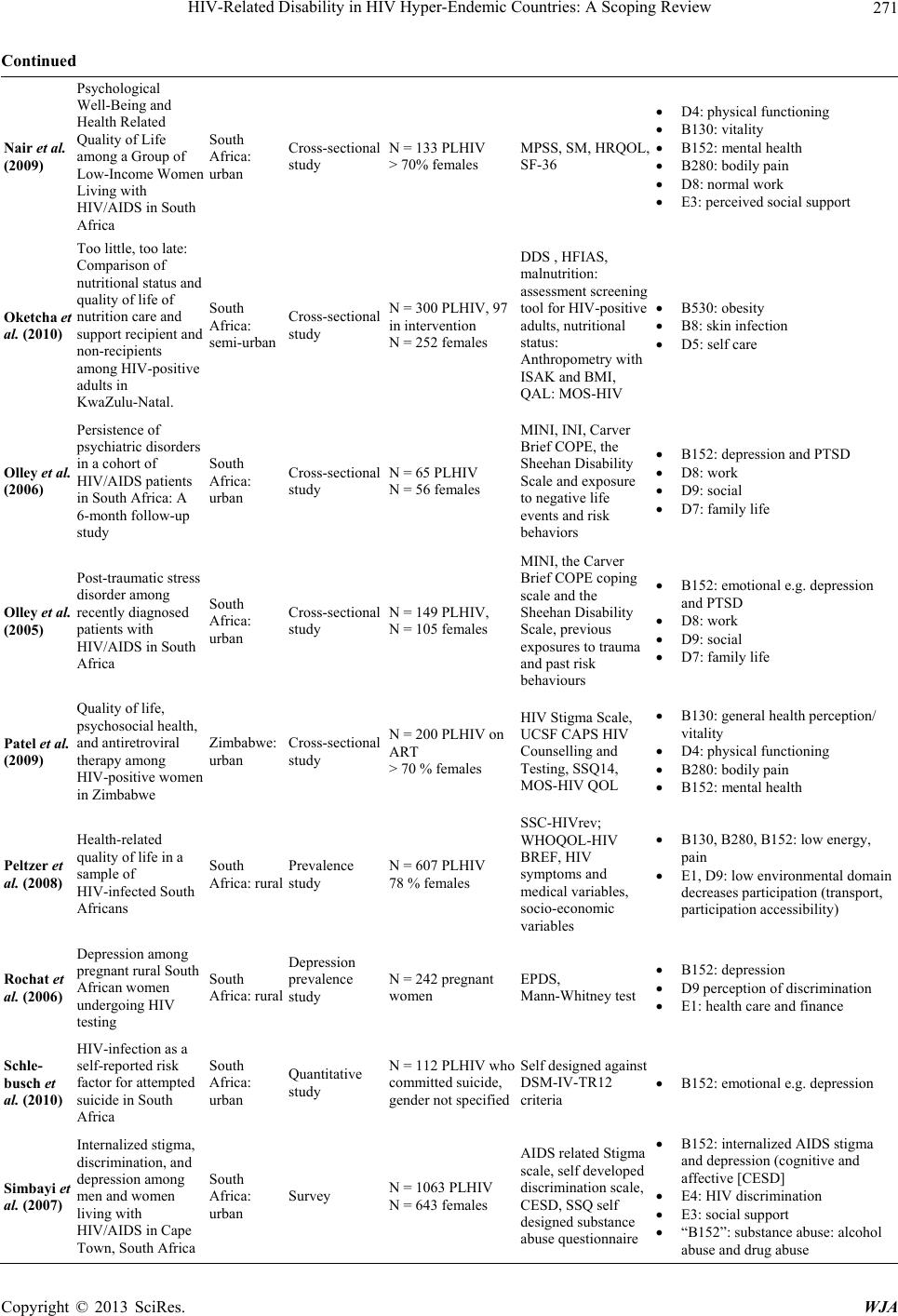

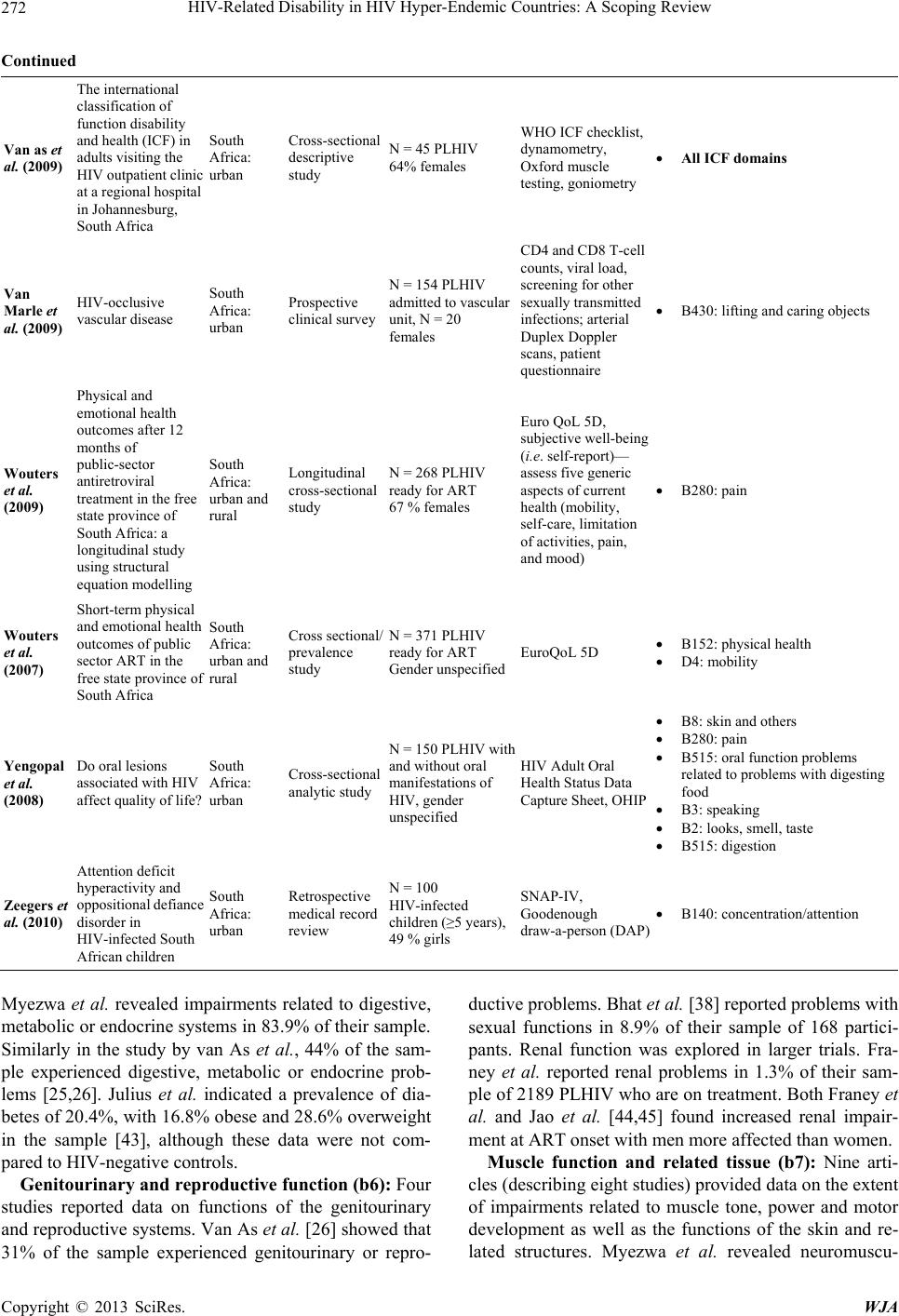

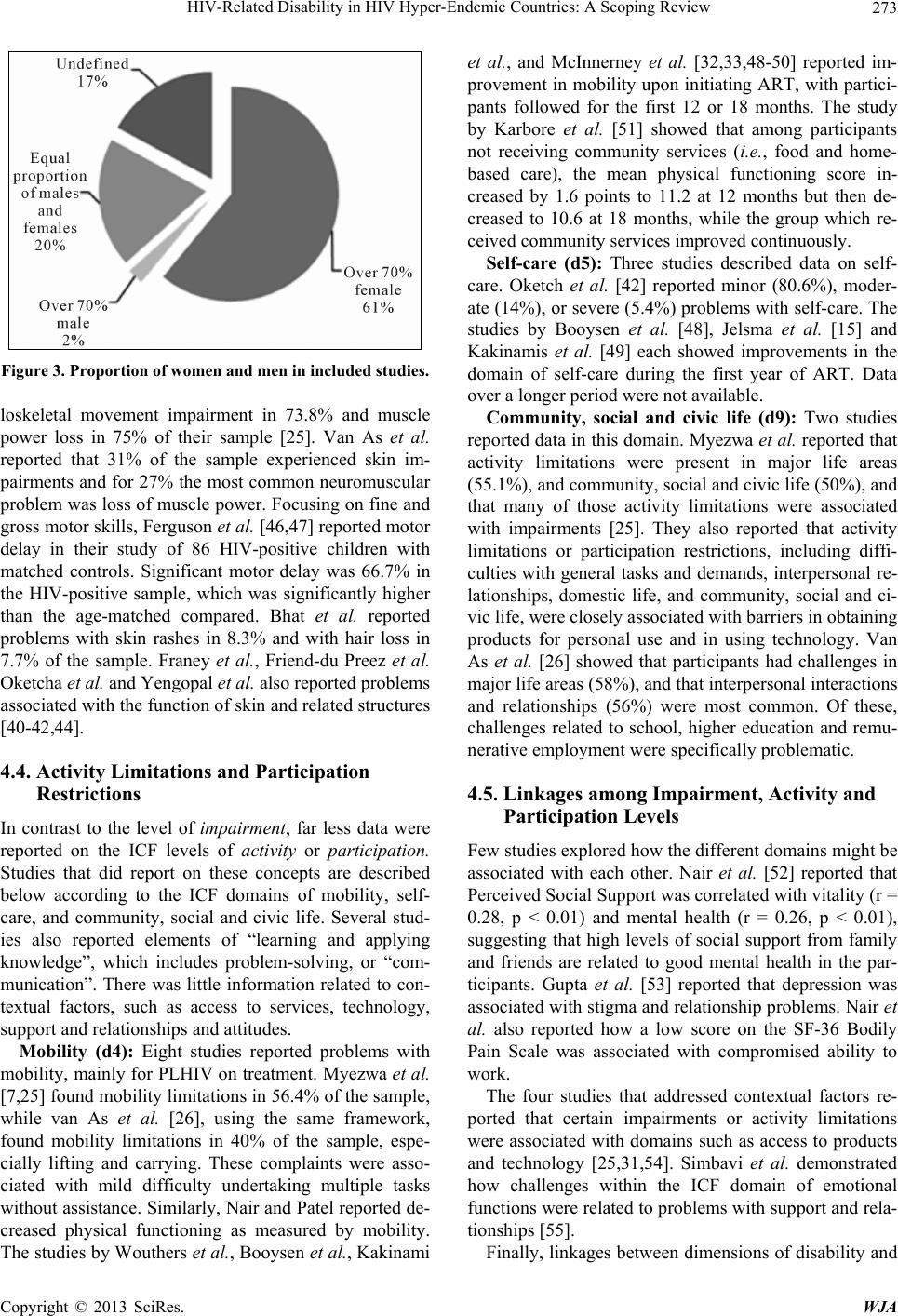

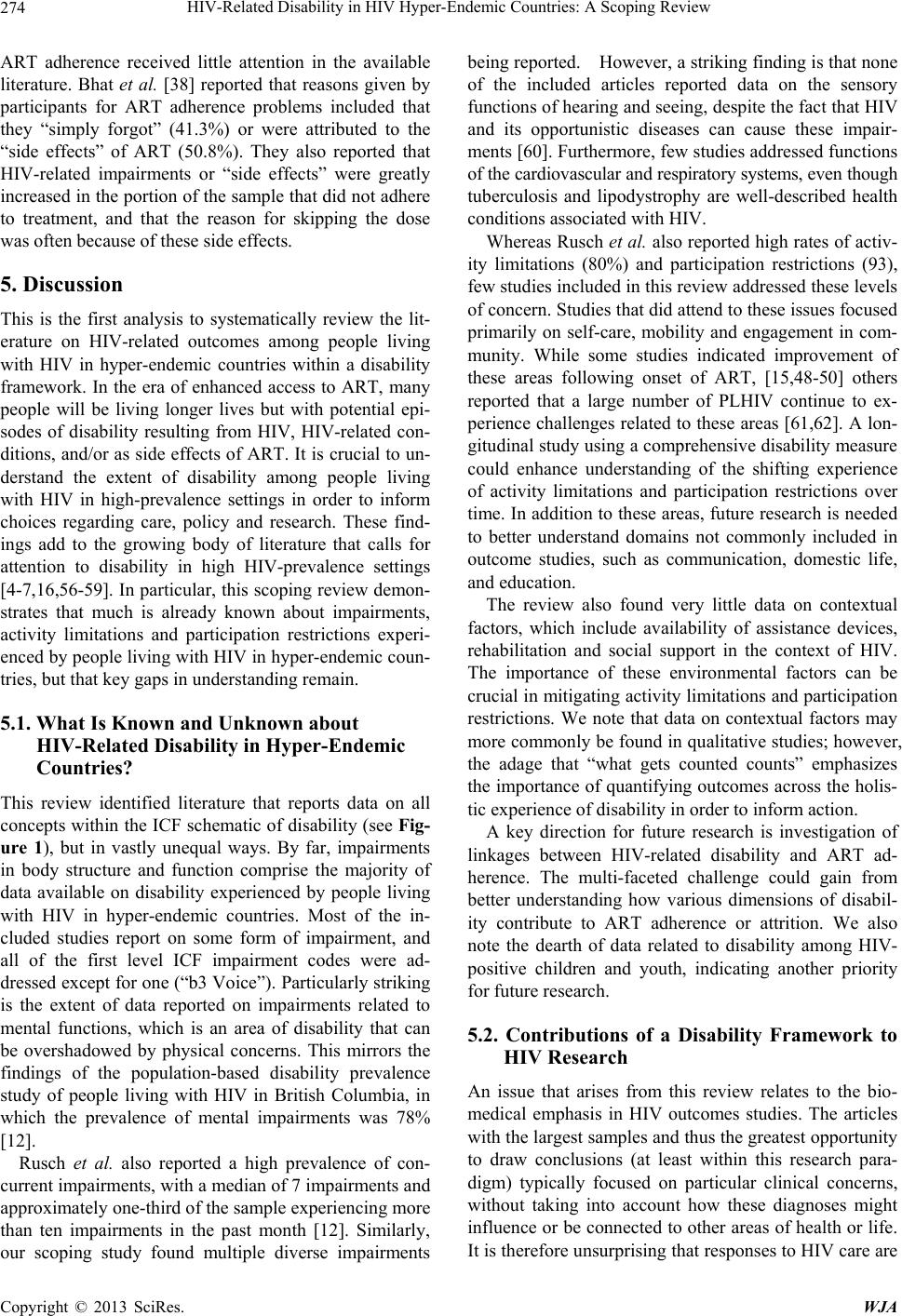

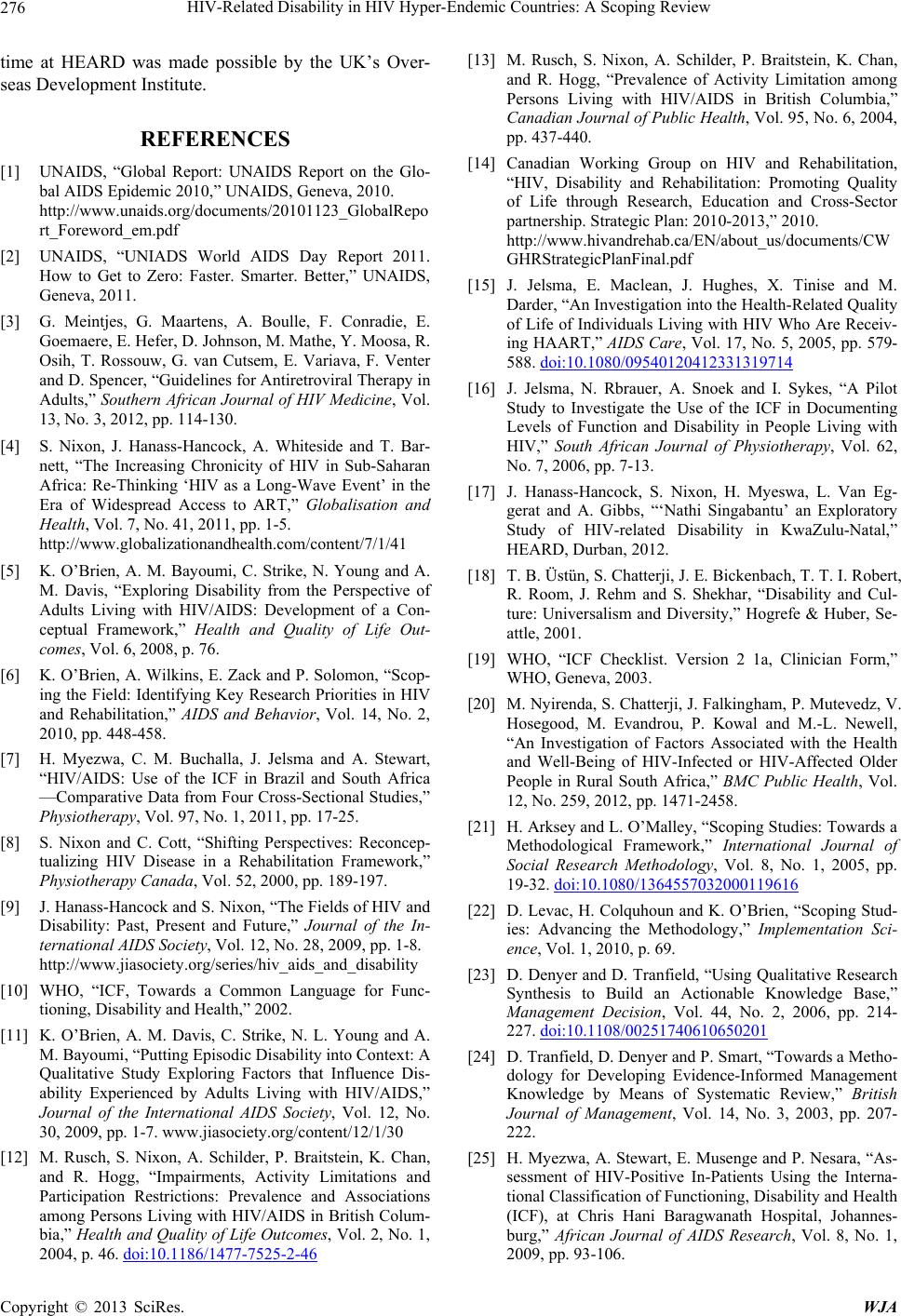

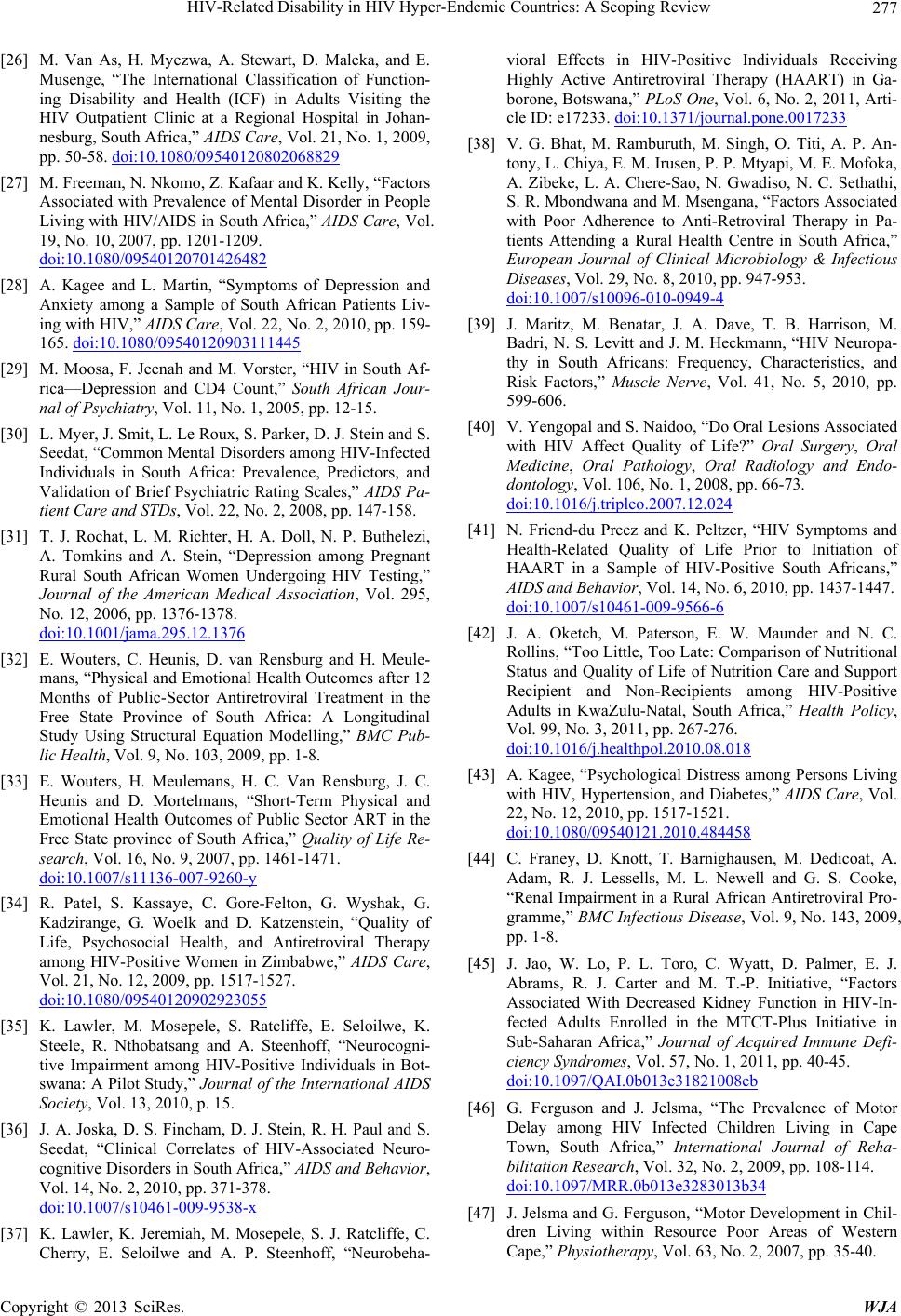

World Journal of AIDS, 2013, 3, 257-279 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/wja.2013.33034 Published Online September 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/wja) 257 HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review* Jill Hanass-Hancock1, Ilaria Regondi1, Leonie van Egeraat1,2, Stephanie Nixon1,3 1Health Economics and HIV/AIDS Research Division, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville Campus, Durban, South Africa; 2University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 3International Centre for Disability and Rehabilitation, Department of Phy- sical Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. Email: hanasshj@ukzn.ac.za Received May 7th, 2013; revised June 7th, 2013; accepted July 7th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Jill Hanass-Hancock et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution Li- cense, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Background: In the era of enhanced access to ART, many people live longer lives but with episodes of disability re- sulting from HIV, HIV-related conditions, and/or as side-effects of ART. It is crucial to understand the extent of dis- ability among people living with HIV in high-prevalence settings to inform choices regarding care, policy and research. This article presents the results of the first scoping review to examine the extent, nature and range of disability among people living with HIV in HIV hyper-endemic countries. Methods: This scoping review used the World Health Orga- nization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to conceptualize “disability”. A sys- tematic search of electronic databases was conducted using specific keyword and subject heading combinations. Iden- tified publications were screened and reviewed according to inclusion/exclusion criteria. Data were systematically ex- tracted and reviewed for quality. Extracted data were reviewed for patterns related to methods or results. Results were aligned with the corresponding ICF code. Results: Forty-one articles were included, reporting data from 38 unique studies. Most (78%) of the studies were conducted in South Africa; five in Botswana, one in Zimbabwe and Lesotho, and none in Swaziland. Almost all studies recruited more females than males. All studies except two were in adults. The studies indicate that people living with HIV experience a variety of disabilities. Impairments in body structure/function comprise the majority of data, with particular focus on mental function. Data on activity limitations and participations restriction were limited, however, they were recorded. They indicate severe impact on people’s life and possible adher- ence. Conclusions: We argue that the time has come to elevate the focus holistically on health and life-related conse- quences of living with HIV and to integrate disability into the discussions and approaches to HIV care. Keywords: Public Health; Disability; HIV/AIDS; Africa; Morbidity 1. Background The experience of HIV is shifting in hyper-endemic countries now that access to free antiretroviral therapy (ART) is becoming more widespread [1,2]. Many people living with HIV who can access and tolerate ART are living longer lives [3]. However, increased longevity can be accompanied by a diverse range of health-related challenges [3], which may be termed disability [4-7]. This changing experience calls for a shift in how we con- ceptualize HIV in order to inform responses within this new era [4,8]. Disability and rehabilitation frameworks became use- ful for HIV policy-makers, advocates and researchers upon the advent of ART in resource-rich countries in the mid- 1990s [9]. In particular, the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [10] is a framework that has proven helpful in un- derstanding and taking action on HIV [8-14]. The ICF has also been used for better understanding the disability dimensions of other health conditions in Southern Africa [7,15-17]. As such, the ICF offers a potentially useful framework for considering the experience of HIV in the era of enhanced access to ART in Southern Africa. *Comprting interests: The authors have no competing interests to de- clare. Authors’ contributions: JHH led the project, wrote the first and subse- quent drafts of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manu- script; IR, LvE, and SN helped conduct the review, contributed to writing of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.In the ICF framework, disability is understood as a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 258 “complex phenomenon that manifests itself at the body, person and social level” [18]. The ICF is concerned with function at three levels, which are termed structure/func- tion (or impairment), activity (or activity limitation), and participation (or participation restriction) [10]. According to this framework, these three levels are outcomes of in- teractions between health conditions, intrinsic contextual features of the individual and extrinsic contextual featur- es of the social and physical environment (see Figure 1). Impairments of body structure or functioning are under- stood to be problems with the anatomical structure of the body (e.g., a missing limb) or its functioning (e.g., mem- ory loss). Activity limitations are understood as difficul- ties with executing a task or action (e.g., getting dress- ed). Participation restrictions are problems relating to in- volvement in life situations (e.g., being employed). The ICF schematic (see Figure 1) is complemented by an ex- tensive ICF Checklist, which assigned “codes” to speci- fic dimensions of functioning and disability at three in- creasingly focused levels [19] (see column entitled “ICF Checklist Code” in Tables 1 and 2). The one population-based study assessing prevalence of disability among people living with HIV was con- ducted in British Columbia, Canada, using an earlier ver- sion of the ICF [12,13]. The study revealed extraordinar- ily high rates of disability: over 90% of the population experienced one or more impairments, with one-third re- porting over ten. Prevalence of activity limitations and par- ticipation restrictions was 80% and 93%, respectively. In Southern Africa, the ICF has been used to study HIV in four studies [7,16,17,20], each of which describes a diverse experience of disability among people living with HIV. A population-based study using the ICF to evaluate the extent of disability among people living with HIV in the world’s hardest hit countries would provide extremely useful data to inform health and social service needs. In the absence of such a study, however, the ICF may be used as a lens for reflecting on the results of other studies collecting data that fit within this broad conceptualization of disability. Using this framework, it is possible to ex- amine HIV studies that are not based on the ICF, but which have investigated particular outcomes that can be located within the ICF concepts of impairment, activity and participation. As such, one could develop a prelimi- nary picture of the disability experienced by people liv- ing with HIV by systematically reviewing various HIV- related outcome studies using the ICF as an organizing framework. This approach would be particularly salient in the HIV hyper-endemic countries of Botswana, Lesotho, Zim- babwe, South Africa and Swaziland where, by definition, over 15% of the country’s population is HIV-positive [1,2]. Given the enormous burden of HIV plus the growth of access to ART in these settings, many people can expect to live longer lives but with diverse experi- ences of disability [3,4]. The policy and practice implica- tions of the shift could be profound. As such, it is im- perative to understand the extent of disability experi- enced by people living with HIV in high-prevalence set- tings. The purpose of this article is to present the results of a scoping review that examined the extent, nature and range of disability (as conceptualized by the ICF) among people living with HIV in HIV hyper-endemic countries. By systematically reviewing data from HIV studies that may be understood within the ICF framework, we seek to demonstrate how a disability framework can complement Health Condition e.g., HIV & comorbidities Participation (participation restrictions) e.g., parenting, work Activity (activity limitation) e.g., ability to climb stairs, ability to dress oneself Body Function & Structure (impairments) e.g., loss of sight, right-sided weakness Environmental Contextual Factors e.g., stigmatizing beliefs within a community, availability of a ramp Personal Contextual factors e.g., gender, age Figure 1. The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) with examples related to living with HIV. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 259 other approaches to HIV. Results can inform directions for future disability-oriented research based on the em- pirical gaps revealed by this analysis. 2. Methods 2.1. Study Design We conducted a scoping study to examine the state of the literature on the extent, nature and range of disability experienced by people living with HIV in hyper-endemic countries. The study design followed the scoping study methodology outlined by Arksey & O’Malley and further developed by Levac et al. [21,22]. This approach was complemented by the systematic review methodology described by Denyer and Tranfield [23,24] to inform our use of the ICF as a lens for classifying outcomes within the HIV literature. 2.2. Search Strategy This scoping study identified peer-reviewed journal arti- cles published between January 2005 and July 2011 re- porting on any disability outcome (as understood within the ICF) among people living with HIV in hyper-en- demic countries. Studies were identified using keyword searches of electronic databases. The databases sourced were: EBSCOhost (including Academic Search Complete, Africa-Wide Information, Health Source, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, eBook Collection, Medline, and Social Sci- ence Citation Index); Science Direct; ISI Web of Science; Cochrane Library; Anthropology Index; Abridged Index Medicus (AIM); and African Journals OnLine (AJOL). The search string used synonyms and variations of the following terms: HIV/AIDS, disability, prevalence stud- ies and HIV hyper-endemic countries. The search string for disability was developed using the first level of the ICF checklist, which identifies particular impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions [10,19]. Details of the search strings for each of the databases are outlined in Additional File 1. 2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Articles were assessed according to six inclusion criteria: 1) Study participants are people living with HIV. 2) Outcomes include data on the extent of disability, as defined by the International Classification of Func- tioning, Disability and Health (ICF). 3) Study designs are cross-sectional, case-control, or other approaches that allow for assessment of frequency, severity and/or type of disability. 4) Studies used standardised and validated instruments 5) Study locations include one or more HIV hyperen- demic country, i.e., Botswana, Lesotho, South Africa, Swaziland and/or Zimbabwe. 6) Data were collected after 2004 and published be- tween January 1, 2005 and July 31, 2011, in order to re- flect experiences of HIV since the growth of access to ART in these settings. The search excluded newspaper articles, case studies, literature reviews, narrative papers, and papers not writ- ten in English. 2.4. Procedure for Article Selection The procedure for selecting articles consisted of four steps: identification of relevant literature; screening of abstract for inclusion and exclusion criteria; assessing eligibility on the basis of full text; and, final inclusion of articles. See Figure 2 for the number of records retrieved and included in each of these steps. Studies retrieved from the initial search were imported into a single Endnote file and duplicates were removed. Each abstract was reviewed independently by two re- search team members for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full articles were downloaded for each abstract that met inclusion criteria. Hard-to-find papers were acquired by contacting the authors. All full-text articles were then reviewed again by a research team member to assess eli- gibility. This process resulted in 41 articles based on 38 different studies. 2.5. Data Extraction Data were extracted from included studies using a data extraction sheet created for this study [21], which re- corded: authors; title; year of publication; year of data (see Figure 2). Table 1 presents the measurement tools used in the included studies. Table 2 reports on how par- ticular items in the measurement tools correspond with codes in the ICF Checklist and, thus, may be understood as reflecting disability. Table 2 first presents the items aligned with the ICF concepts of “body function and structure (impairments)”, followed by “activity limitations and participations restrictions” and, lastly, according to “environmental and personal contextual factors”. Table 3 presents details of each of the 41 included ar- ticles. The final column in Table 3 presents the specific ICF dimensions of disability addressed by each study. Below we summarize findings related to the extent, na- ture and range of disability reported across the studies. Overall, the included studies predominately reported data at the disability level of impairment. We first present a summary of these data according to the following ICF categories: mental, sensory/perception, cardiovascular/ respiratory, digestive/metabolic/endocrine, genitourinary and reproductive, and muscle. We then summarize the lesser amount of data in the included studies related to he disability levels of activity and participation. Finally, t Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 260 Table 1. Measurement tools used in included studies that c o rre sponde d with dimensions of the ICF. Measurement tool Included studies using each measurement tool ADL—Activities of Daily Living Scale Lawler et al. 2011 AIDS-related Stigma Scale Simbayi et al. 2007 AUDIT—Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Joska et al. 2009, Myer et al. 2008 BDI—Beck Depression Inventory Do et al. 2007, Lawler et al. 2011, Moosa et al. 2005 BPNS—Brief Peripheral Neuropathy Score Kagee et al. 2010, Maritz et.al 2005 BAVLT—Botswana Auditory Verbal Learning Test Lawler et al. 2011 BSID—Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition Ferguson et al. 2009, Jelsma 2007, Jelsma 2005 Carver Brief COPE Olley et al. 2006, Olley et al. 2005 CESD—Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Myer et al. 2008, Fincham et al. 2008, Simbayi et al. 2007 CIDI—Composite International Diagnostic Interview Freeman et al. 2007 DAP—Goodenough Draw a Person Zeegers et al. 2010 DDS—Dietary Diversity Score Oketcha et al. 2010 DSC—Neuropsychological Test Battery Digit Symbol Lawler et al. 2011 EPDS—Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale Rochat et al. 2006 DSM-IV – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV Schlebusch et al. 2010 EUROQoL—Euro Group Quality of Life Instrument Wouters et al. 2009, Wouters 2007 EQ-5D—Five Domain Index of Health Status Booyson et.al. 2007 GPT—Grooved Peg Board Test Gupta et al. 2010, Lawler et al. 2011 HDS—HIV Dementia Scale Joska et al. 2009 HIV Stigma Scale Petel et al. 2009 HR-QOL—Health Related Quality of Life Survey Friend-du Preez et al. 2009, Kabore et al. 2010, Nair et al. 2009 HFIAS—Household Food Insecurity Assess Scores Kagee et al. 2010, Oketcha et al. 2010 HSCL-D—Hopkins Symptom Checklist for Depression Kagee et al. 2010 HTS—Harvard Trauma Scale Joska et al. 2009 HTQ—Harvard Trauma Questionnaire Myer et al. 2008 ICF—World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Myezwa et al. 2009, Van As et al. 2009 IHDS—International HIV Dementia Scale Lawler et al. 2010 LEC—Life Events Checklist Joska et al. 2009 Mann-Whitney Test Rochat et al. 2006 MINI—Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview Fincham et al. 2008, Joska et al. 2009, Myer et al. 2008, Olley et al. 2006, Olley et al. 2005 MAS—Morisky Adherence Scale McInerney et al. 2008 MOS-SS—Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale McInerney et al. 2008, MOS-HIV QAL—Medical Outcome Study HIV and Quality of Life Oketcha et al. 2010, Petel et al. 2009 MPSS—Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Nair et al. 2009 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 261 Continued UNAIDS General Survey and the Department of Health Services AIDS module Gupta et al. 2010 OHIP—Oral Health Impact Profile Yengopal et al. 2008 Prime-MD—Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Lawler et al. 2011(a), Lawler et al. 2011(b) PNASACTG—Perceived Non-Adherence McInerney et al. 2008 RSRCI—Retrospective Self-Report of Childhood Inhibition Fincham et al. 2008 Sheehan Disability Scale Olley et al. 2006 SSC-HIVrev—Sign and Symptom Checklist for Persons with HIV Disease Peltzer et al. 2008 SCC—Subjective Cognitive Complaints Questionnaire Lawler et al. 2010 SSQ14—Shona Symptom Questionnaire Friend-du Preez et al. 2009, Petel et al. 2009, Simbayi et al. 2007 SF-36—Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form McInerney et al. 2008, Nair et al. 2009 SNAP-IV—Swanson, Nolan and Pelham questionnaire Zeegers et al. 2010 SM—Suicidality Measure (adapted from Sheehan) Nair et al. 2009 TNSr—Total Neuropathy Score-Reduced Maritz et al. 2005 UCSF CAPS HIV—University of California at San Francisco Center for AIDS Studies HIV Counseling and Testing Questionnaire Patel et al. 2009 WHOQOL-HIV BREF (HRQoL) World Health Organisation’s Quality of Life Instrument Module for HIV Friend-du Preez et al. 2009, Peltzer et al. 2008 WHO staging Jao et al. 2011 WAIS—Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (third edition) Lawler et al. 2010 Medical records Franey 2009, Julius et al. 2011, Van Marle et al. 2009 Self-designed questionnaire Bhat et al. 2010, Kabore et al. 2010, Kakinami et al. 2010 Table 2. Constructs in measurement tools corresponding with ICF Checklist codes. ICF Checklist code Measurement tool used in the included studies Sample items Body Function and Structure (impairments) b1. MENTAL FUNCTIONS MINI-Neuro feeling dizzy, unsteady, faint b110 Consciousness SSC-HIVrev experiencing dizziness b114 Orientation (time, place, person) WHODAS understanding, cognition SRQ-20 trouble thinking HIV-dementia scale measuring constructing a cube b117 Intellectual (incl. retardation, dementia) Bayleys scales cognitive development tasks SSC-HIVrev experiencing fatigue SRQ-20 experiencing loss of energy, fatigue CES-D being tired, exhausted, feeling tired, without energy, not get going b130 Energy and drive functions HOP25/HCL feeling low energy, everything is an effort Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 262 Continued Hamilton Inventory feeling physically slowed down SCID-CV experiencing low energy, tired, fatigue MOS-HIV (QOL) being tired out, enough energy, worn out b130 Energy and drive functions WHO QOL—HIV BREF low energy BDI having sleeping problems SRQ-20 sleep badly MINI-Neuro trouble sleeping CES-D trouble sleeping HOP25 / HCL difficulty falling asleep, staying sleeping Hamilton Inventory waking up, sleep problems b134 Sleep SCID-CV sleep problems, waking BDI experiencing concentration problems SNAP-ADHD experiencing low attention (impulsivity, hyperactive behavior, restlessness, day dreaming) WHODAS ability to concentrate HIV-dementia scale keeping attention MINI-Neuro concentration, keeping attention, restlessness SCID-SC thinking and concentrating problem MOS-HIV (QOL) keeping attention, concentrating and thinking WHO QOL—HIV BREF concentrating b140 Attention SSC-HIVrev experiencing concentration problems HIV-dementia scale remembering MOS-HIV (QOL) experiencing memory, forgetting b144 Memory SSC-HIVrev experiencing memory loss EQ-5D being depressed or anxious SSC-HIVrev having fear, being upset BDI experiencing sadness, crying, temper, self-dislike HIV stigma scale being emotional affected, self-dislike Edward depression scale stop laughing, being sad or happy, blaming, being anxious, panicking, feeling depressed SNAP ADHD being emotionally affected WHODAS worried, ending life, unhappy, joy, crying, no interest SRQ-20 being worried, panicked, fear being in public, feeling sad, depressed, empty, bad mood, grouchy, losing joy b152 Emotional functions CIDI feeling worthless, suicidal, guilty, hopeless Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 263 Continued MINI-Neuro being worried, sad CES-D crying, lonely, nervous, fearful, lonely, no interest, ending life HOP25/HCL experiencing emotions, feeling depressed, moods, crying, anxious, nervous Hamilton Inventory losing interest, pleasure, feeling depressed, thinking about death, feeling nervous an afraid, downhearted MOS-HIV (QOL) experiencing joy, fear, worry, self-blame& acceptance, being depressed anxious WHO QOL—HIV BREF experiencing fear and worries b152 Emotional functions DSM IV experiencing fear, being afraid, scared, having nightmares, being upset SSC-HIVrev experiencing numbness Neuropathy diagnostic tool feeling pin and needles, numbness MINI-Neuro tingling Hamilton Inventory feeling pins and needles SSC-HIVrev having numbness and tingling b156 Perceptual functions BPMS and TNSr having numbness and tingling b164 Higher level cognitive functions MINI-Neuro having trouble with language b167 Language Bayleys scales understanding and expression b2. SENSORY FUNCTIONS AND PAIN EQ-5D feeling pain SSC-HIVrev having headaches Neuropathy diagnostic tool feeling pain SRQ-20 feeling headache MINI-Neuro feeling pain HOP25 / HCL feeling headache Hamilton Inventory feeling pain MOS-HIV (QOL) feeling pain b280 Pain WHO QOL—HIV BREF feeling physical pain b3. VOICE AND SPEECH b4. FUNCTIONS OF THE CARDIOVASCULAR, HAEMATOLOGICAL, IMMUNOLOGICAL AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEMS b420 Blood pressure Medical lab tests b5. FUNCTIONS OF THE DIGESTIVE, METABOLIC AND ENDOCRINE SYSTEMS b515 Digestive SRQ-20 having digestion problems Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 264 Continued b515 Digestive SSC-HIVrev having abdominal pain, diarrhea b525 Defecation CIDI losing or gaining weight Hamilton Inventory losing weight SCID-CV losing or gaining weight b530 Weight maintenance SSC-HIVrev gaining weight b555 Endocrine glands (horm onal changes) Lab tests having metabolic diseases BDI SRQ-20 CIDI having no appetite, experiencing appetite disturbance b6. GENITOURINARY AND REPRODUCTIVE FUNCTIONS ADL-score having problems with bladder control b620 Urination functions Medical records and lab tests having renal impairments b7. NEUROMUSCULOSKELETAL AND MOVEMENT RELATED FUNCTIONS WHODAS being able to stand b730 Muscle power SSC-HIVrev having skinny arms, thump on back b735 Muscle tone Hamilton Inventory having stiff muscle SSC-HIVrev being itchy (numbness) b8. FUNCTIONS OF THE SKIN AND RELATED STRUCTURES Neuropathy diagnostic tool felling pin and needles, numbness Any other body functions Activity (activity limitations) and Participation (participation restrictions) d1. LEARNING AND APPLYING KNOWLEDGE d115 Listening WHODAS following conversations WHODAS problem solving HIV-dementia scale constructing a cube MOS-HIV (QOL) solving problems d175 Solving problems Bayleys scales performing cognitive development tasks d2. GENERAL TASKS AND DEMANDS d3. COMMUNICATION d4. MOBILITY Neuropathy diagnostic tool lifting objects d430 Lifting and carrying objects MOS-HIV (QOL) lifting HIV-dementia scale psychomotor speed with hand d440 Fine hand use (picking up, grasping) Bayleys scales conducting fine motor tasks Neuropathy diagnostic tool climbing a hill, walking 50 meters d450 Walking WHODAS walking Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 265 Continued MOS-HIV (QOL) walking EQ-5D walking d450 Walking Bayleys scales conducting gross motor tasks d465 Moving around using equipment (wheelchair, skates, etc.) ADL-score WHODAS transferring from positions moving around d5. SELF CARE EQ-5D having problems with washing d510 Washing oneself (bathing, drying, washing hands, etc.) ADL-score bathing, transfer yourself d520 Caring for body parts (brushing teeth, shaving, grooming, etc.) ADL-score going on toilet d530 Toileting MOS-HIV (QOL) toileting EQ-5D having problems with dressing ADL-score dressing WHODAS dressing d540 Dressing MOS-HIV (QOL) dressing d550 Eating MOS-HIV (QOL) eating d6. DOMESTIC LIFE Sheehan Disability scale disrupted work EQ-5D performing “usual activities” e.g. housework WHODAS doing housework MOS-HIV (QOL) doing housework and social activities d640 Doing housework (cleanin g house, washing dishes laundry, ironing, etc.) WHO QOL—HIV BREF doing daily living activities d8. MAJOR LIFE AREAS d810 Informal education d820 School education Sheehan Disability scale having disrupted school d830 Higher education EQ-5D performing “usual activities” e.g. work Sheehan Disability scale having disrupted work WHODAS doing work d850 Remunerative employment MOS-HIV (QOL) working d9. COMMUNITY, SOCIAL AND CIVIC LIFE Sheehan Disability scale having “disrupted social life” d910 Community Life HIV stigma scale stopping to socialize d920 Recreation and leisure WHO QOL—HIV BREF participating in leisure activities Environmental and Personal Contextual Factors e1. PRODUCTS AND TECHNOLOGY e2. NATURAL ENV’T AND HUMAN MADE CHANGES TO ENVIRONMENT Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA 266 Continued e3. SUPPORT AND RELATIONSHIPS Multi Scale of perceived Social Support emotional support from family e310 Immediate family WHO QOL—HIV BREF having relationships Multi Scale of perceived Social Support having support friends e320 Friends WHO QOL—HIV BREF having support from friends e340 Personal care providers and personal assistants Multi Scale of perceived Social Support having support from career e4. ATTITUDES e460 Societal attitudes HIV-stigma scale feeling treated like an outcast, experiencing rejection by people e465 Social norms, practices and ideologies HIV-stigma scale keeping HIV secret E5. SERVICES Identification 7564 recor ds i de nti fied throu h database search 5211 records screened (based on abstract 5145 records excluded for failing to meet inclusion or exclusion criteria 66 records assessed for eligibility (based on full article) 41 records included, drawing from 38 different studies 25 records excluded for failing to meet inclusion or exclusion criteria 2353 duplicates excluded Inclusion Eligibility Screening Figure 2. Flow of citations through article selection process. we review the few studies that examined interlinkages collection; country and context (rural, peri-urban or ur- ban); sample size; target group; sampling method; study design; concepts/constructs measured; scales/tools used; study results in general; results relevant to disability as defined in the ICF; study limitations; and authors’ rec- ommendations. Extracted data were reviewed by a sec- ond research team member to ensure quality control and consistency of extraction process. Inconsistencies were resolved through consensus. 3. Analysis Once data were extracted from the 41 included articles (38 studies), we reviewed the findings for patterns related to study methods (e.g., approaches to sampling or study tools) and study results (e.g., data related to particular impairments). To analyse study results according to the ICF, we first aligned each study’s findings with the cor- responding ICF code. For articles that identified specific outcomes (e.g., difficulty getting dressed), we were able to directly align the outcome with the corresponding di- mension of the ICF framework (e.g., ICF code “d540 Dressing”). For studies that identified research measure- ment tools (e.g., the Hamilton Inventory), we reviewed each tool to clarify whether and how certain items within the tool corresponded with particular dimensions of the ICF (e.g., the item “sleep problems” in the Hamilton In- ventory corresponds with ICF code “b134 Sleep”). Table 1 outlines the measurement tools used in the included studies. Table 2 illustrates how constructs in each measure- ment tool corresponded with the ICF Checklist codes. Once study results were organized according to the ICF, we reviewed these findings for patterns and gaps related to the extent, nature and range of disability described across the studies. 4. Results 4.1. Characteristics of Included Studies Forty-one articles met inclusion criteria, which reported data from 38 different studies. Table 3 presents the char- acteristics of included studies. Of the five hyper-endemic countries considered in the scoping study, 78% of the included articles were studies conducted in South Africa (32 articles), 5 in Botswana and 1 in Zimbabwe; no stud- ies were conducted exclusively in Lesotho or Swaziland. Two studies were conducted in more than one country, one including a site in Lesotho.  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 267 Fifty one per cent of articles (21) took place exclu- sively in urban areas; 17% (7 articles) only in rural areas; 12% (5 articles) in both urban and rural settings; and 10% of studies (4 articles) in semi and peri-urban areas. Study setting was unclear in four articles. In terms of study design, most studies were cross-sec- tional (30 articles). Three studies also used either a pro- spective or retrospective study design. In terms of sample size, 85% of the articles (35 articles) included more than 100 participants. Three articles (7%) used a random sam- pling technique and 3 articles (7%) used stratified sam- pling. Nineteen articles (47%) used convenience sam- pling, 2 articles (5%) used purposive sampling, and 14 articles (34%) did not specify their sampling strategy. Almost all studies recruited more females than males. In 61% (25 articles), more than 70% of the sample was fe- male; 20% (8 articles) recruited roughly equal numbers of males and female; 17% (7 articles) did not describe the sex of their participants (see Figure 3). All studies included adults except for two, which included youth below the age of eighteen [25,26]. 4.2. Extent, Nature and Range of Disability This scoping review investigated the state of literature on disability (as conceptualized by the ICF) experienced by people living with HIV in HIV hyper-endemic countries among ICF levels. 4.3. Impairments Related to Body Structure and Function Mental Function (b1): Twenty articles presented data focusing on mental functioning and an additional 8 arti- cles presented mental functioning as part of a wider in- quiry into participants’ health or quality of life. Using the ICF, Myezwa et al. [25] reported impairments in mental function in 72.6% of their sample of 80 people living with HIV. They also reported energy and drive impair- ments in 75% and sleep impairments in 71% of the sam- ple. Also using the ICF, van As et al. [26] reported men- tal functions impairments in 69% of their sample of 45 adults visiting an HIV outpatient clinic. Disorders such as depression, anxieties and post-traumatic stress disor- der (PTSD) were identified in a number of studies, with percentages of the sample showing symptoms of mental health condition as follows: Kagee 38% (depression), Myer 19%, Moosa 56%, Freeman 43% (depression), Rochat 41%, Olley 2006 48% (depression, post-trauma- tic stress disorder—PTSD), Olley 2005 14.8% (PTSD), Lawler 38% (depression), Gupta (28% (depression) and Finchman 13.1% (anxiety) [27-31]. Wouters et al. re- ported anxiety or feelings of depression in 30% of their sample [32,33]. Two studies [32-34] reported improve- ments in the area of emotional functions, energy and drive while being on treatment; however, one study high- lighted how activity limitations continued to affect the patient’s life when on ART [33]. Other mental function domains reported in the litera- ture were consciousness, intellectual functions, memory and language. Lawler et al. (2010) reported that 38% of their 120 participants were diagnosed with HIV-dementia. Joska et al. reported that 23.5% of their 536 participants in urban South Africa were diagnosed with HIV-associ- ated neurocognitive disorder (HAND). Lawler et al. (2011) reported that 37% of people living with HIV were described as cognitively impaired [35-37] and Bhat et al. identified significant loss of memory in 17.9% of their sample of 168 patients at a rural health centre in South Africa [38]. The study by Lawler et al. which used a con- trol group, reported that HIV-positive participants were more impaired on neuropsychological measures when compared to demographically-matched controls for all cognitive-motor ability areas, which included processing speed, verbal learning/memory, language, psychomotor speed, executive function, and fine motor speed [37]. Sensory and perception functions (b2): The sensory or perception functions reported most frequently were tingling or numbness. Maritz et al. reported 49% of their sample on HAART was diagnosed with peripheral neu- ropathy, and 30% with severe neuropathic symptoms [39]. Data were also reported on sensory function prob- lems and pain. Bhat et al. [38] reported that 20% of their sample experienced pain, Van As et al. [26] reveals that 71% of their sample experiencing sensory functions pro- blems and pain, and Myezwa et al. [25] reported 83.5% experienced sensory functions disorders. Similarly pain and discomfort were reported in 37% of participants in the study by Wouters et al. [32]. One study [40] report- ed on changes in ability to taste while being on treatment. No data were reported on other sensory functions, such as visual, hearing or voice impairments. Cardiovascular and respiratory function (b4): Four articles reported data in regards to functions of the car- diovascular and respiratory system. Myezwa et al. [25] described problems in 82.5% of the participants related to the haematological, immunological and respiratory systems. Similarly, the study by van As et al. of 45 clinic patients found hypertension in 33% of the sample, respi- ratory problems in 22% (which they attributed largely to TB), and at least one haematological problem in 96% of the sample. High blood pressure was also recorded Ma- ritz et al., and problems with breathing and breathless- ness in 13% of the sample in Bhat et al. Digestive, metabolic and endocrine function (b5): Six studies reported data on impairments in digestive, metabolic or endocrine function, on or off treatment. Data were presented regarding increase or loss in weight as well as diagnostic of obesity [38,41,42]. Additionally, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA 268 Table 3. Characteristics of included studie s. Author Title Study site Study designPopulation Study Instruments ICF Checklist Code Bhat et al. (2010) Factors associated with poor adherence to antiret- roviral therapy in patients attending a rural health centre in South Africa South Africa: rural Cross-sectionalN = 168 PLHIV on ARV 60% females Self-designed pre-structured questionnaires B130: “side effects”, fatigue B144: memory B280: pain S120 or B156: tingling B530: weight loss B440: breathing problems B152: depression, sadness, anxiety b152 B640: sexual dysfunction B8: skin rash and hair changes Booysen et al. (2007) The heart in HAART: quality of life of patients enrolled in the public-sector antiretroviral treatment programme in the Free State Province of South Africa South Africa: rural Case-control study N = 371 PLHIV waiting for ART and ART Almost ²/3 females EQ-5D D4: quality of life B: mobility (not specified) D5: self care (not specified) Do et al. (2010) Psychosocial Factors Affecting Medication Adherence among HIV-1 Infected Adults Receiving Combination Antiretroviral Therapy (cART) in Botswana Bot- swana: urban Cross-sectional N = 300 PLHIV on ART 76.3 % females BDI B152: alcohol abuse and depression B144: forgetting ART Ferguson et al. (2009) The prevalence of motor delay among HIV-Infected children living in cape Town, South Africa Also Jelsma, J. & Ferguson, G., 2007, Motor Development in Children Living within Resource Poor Areas of Western Cape South Africa: urban Disability prevalence N = 86 (HIV infected children and non-infected children BSID B 7 and d4: motor development delay Fincham et al. (2008) The relationship between behavioural inhibition, anxiety disorders, depression and CD4 counts in HIV-Positive adults: a cross-sectional controlled study South Africa: rural Cross-sectional N = 456 PLHIV 75 % females RSRCI, CES-D, MINI B152: GAD, depression and PTSD D7: social fears associated to depression (not specified) Franey et al. (2009) Renal Impairment in a Rural African Antiretroviral Programme South Africa: rural Retrospective review and prospective study N = 2189 patients on ARV 68.8 % females Review of medi- cal records B8: skin irritations B620: renal dysfunction Freeman et al. (2007) Factors Associated with Prevalence of Mental Disorder in People Living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. South Africa: rural Cross-sectional N = 900 PLHIV some on ART 74 % females CIDI, Point-prevalence B152: mental health disorder (mainly depression) D7: discrimination by community/ family and isolation  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 269 Continued Friend-du Preez et al. (2009) HIV Symptoms and Health-Related Quality of Life Prior to Initiation of HAART in a Sample of HIV-Positive South Africans South Africa: rural Cross-sectional N = 612 PLHIV prior HAART 70.3 % females SSC-HIVrev, WHOQOL-HIV BREF (HRQoL) B530: weight loss B8: dry mouth B280: headaches B144: memory loss B130: weakness B280: painful joints Gupta et al. (2010) Depression and HIV in Botswana: A population-based study on gender-specific socioeconomic and behavioral correlates Botswana: rural Cross-sectional N = 1168 PLHIV Not known gender distribution HSCL-D, UNAIDS General Survey and the Department of Health Services AIDS module B152: emotional e.g. depression D7 and D770: lack of control in sexual relationships and stigma Jao et al. (2011) Factors associated with decreased kidney function in HIV-infected adults enrolled in the MTCT-Plus Initiative in Sub-Saharan Africa Multicounty including, South Africa Prevalence study N = 2495 PLHIV on ART > 70 % females WHO staging, CD4 cell count, Cockcroft-Gault (CG) equations for creatinine clearance, Diet in Renal Disease Equation (MDRD) and CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) B620: Urination functions Jelsma et al. (2005) An investigation into the health-related quality of life of individuals living with HIV who are receiving HAART South Africa: urban Cross-sectional N = 83 PLHIV on HAART 74.5 % females EQ-5D B280: pain, discomfort B152: emotional e.g. anxiety and depression D4 mobility D5: self care activities Joska et al. (2009) Clinical Correlates of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND) in South Africa South Africa (SA): urban Cross-sectional N = 536 PLHIV 73.3 % females HDS, MINI, AUDIT, HTS, LEC B114, B117, B140, B144: HAND B152: PTSD Julius et al. (2011) The Burden of Metabolic Diseases Amongst HIV Positive Patients on HAART Attending The Johannesburg Hospital South Africa: urban Cross-sectional N = 304 PLHIV on ART >1 year) 78 % females Patient clinical records, blood tests and anthropometric measurements. B4: metabolic diseases (diabetes, hypertension...) Kabore et al. (2010) The Effect of Community-Based Support Services on Clinical Efficacy and Health-Related Quality of Life in HIV/AIDS Patients in Resource-Limited Settings in Sub-Saharan Africa Cross-count ry incl. South Africa, Lesotho and Botswana Observational cohort study N = 377 PLHIV on ART 72% females Self designed questionnaires, HRQOL D4: ART and/or community support improved physical D9: social B1 or B117: cognitive B152: emotional functioning B130: energy drive (all at baseline lower) Kagee et al. (2010) Psychological Distress among Persons Living with HIV, Hypertension, and Diabetes South Africa: semi-urban Cross-sectional N = 124 PLHIV receiving treatment for diabetes or hypertension, 79% females HSCL-25 B152: emotional distress Kagee et al. (2010) Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety among a Sample of South African Patients Living with HIV South Africa: semi-urban Prevalence study N = 85 PLHIV some on ART 75.3% females HSCL-25, BDI B152: depression and anxiety Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 270 Continued Kakinami et al. (2010) The Impact of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy on Activities of Daily Living in HIV-Infected Adults in South Africa South Africa: urban and rural Cross sectionalN = 4328 PLHIV 71% - 78% women Self developed questionnaires D4-6 activity assistance needs Lawler et al. (2011) Neurobehavioral effects in HIV-positive individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in Gaborone, Botswana Botswana: urban Cross-sectional N = 140 PLHIV on ART (60 intervention group and 80 control group), gender not provided DSC, BAVLT, GPT, Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders, ADL B117, B144, D140, B3: cognition and/or fine motor speed, language B152: anxiety disorder Lawler et al. (2010) Neurocognitive impairment among HIV-positive individuals in Botswana: a pilot study Botswana: urban Cross-sectional N = 120 PLHIV 50% females IHDS, Verbal Learning Test, WAIS Digit Symbol Coding, Mood Module of the primary care evaluation of mental disorders, Activities of Daily Living Scale, SCC B117: dementia Lawler et al. (2011) Depression among HIV-positive individuals in Botswana: a behavioral surveillance Botswana: urban Mental health prevalence N = 120 PLHIV (random) 50% women BDI-FS, Mood Module (MM) of Prime-MD, ADL B152: emotional e.g. depression Maritz et al. (2010) HIV Neuropathy In South Africans: Frequency, Characteristics, And Risk Factors South Africa: urban Cross-sectional N = 598 PLHIV on ART 76% females BPNS, TNSr, CD4 counts, ART status B156 or B7: neuropathy B420: blood pressure Mclnerne y et al. (2008) Quality of life and physical function in HIV-infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa South Africa: area not described Descriptive exploratory design N = 149 PLHIV on ART N = 95 females MOS-SSS, SF-36, MOS-SF36HS, PNASACTG, MAS D4: mobility D2: general tasks and demands E3: social support Moosa et al. (2005) HIV in South Africa - depression and CD4 count South Africa Prevalence of depression N = 41 PLHIV 71% females BDI - Beck Depression Inventor, CD4 count test B152: emotional e.g. depression Myer et a l. (2008) Common Mental Disorders among HIV-Infected Individuals in South Africa: Prevalence, Predictors, and Validation of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scales South Africa: semi-urban Cross-sectional study N = 465 PLHIV with >24 on the MMSE 75% females MINI, CES-D, HTQ, AUDIT B152: depression PTSD and alcohol dependence Myezwa et al. (2009) Assessment of HIV-positive in-patients using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, Johannesburg South Africa: urban Cross-sectional study with ICF checklist N = 80 PLHIV some on ART Gender not specified ICF checklist All ICF domains Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 271 Continued Nair et al. (2009) Psychological Well-Being and Health Related Quality of Life among a Group of Low-Income Women Living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa South Africa: urban Cross-sectional study N = 133 PLHIV > 70% females MPSS, SM, HRQOL, SF-36 D4: physical functioning B130: vitality B152: mental health B280: bodily pain D8: normal work E3: perceived social support Oketcha et al. (2010) Too little, too late: Comparison of nutritional status and quality of life of nutrition care and support recipient and non-recipients among HIV-positive adults in KwaZulu-Natal. South Africa: semi-urban Cross-sectional study N = 300 PLHIV, 97 in intervention N = 252 females DDS , HFIAS, malnutrition: assessment screening tool for HIV-positive adults, nutritional status: Anthropometry with ISAK and BMI, QAL: MOS-HIV B530: obesity B8: skin infection D5: self care Olley et al. (2006) Persistence of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of HIV/AIDS patients in South Africa: A 6-month follow-up study South Africa: urban Cross-sectional study N = 65 PLHIV N = 56 females MINI, INI, Carver Brief COPE, the Sheehan Disability Scale and exposure to negative life events and risk behaviors B152: depression and PTSD D8: work D9: social D7: family life Olley et al. (2005) Post-traumatic stress disorder among recently diagnosed patients with HIV/AIDS in South Africa South Africa: urban Cross-sectional study N = 149 PLHIV, N = 105 females MINI, the Carver Brief COPE coping scale and the Sheehan Disability Scale, previous exposures to trauma and past risk behaviours B152: emotional e.g. depression and PTSD D8: work D9: social D7: family life Patel et al. (2009) Quality of life, psychosocial health, and antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive women in Zimbabwe Zimbabwe: urban Cross-sectional study N = 200 PLHIV on ART > 70 % females HIV Stigma Scale, UCSF CAPS HIV Counselling and Testing, SSQ14, MOS-HIV QOL B130: general health perception/ vitality D4: physical functioning B280: bodily pain B152: mental health Peltzer et al. (2008) Health-related quality of life in a sample of HIV-infected South Africans South Africa: rural Prevalence study N = 607 PLHIV 78 % females SSC-HIVrev; WHOQOL-HIV BREF, HIV symptoms and medical variables, socio-economic variables B130, B280, B152: low energy, pain E1, D9: low environmental domain decreases participation (transport, participation accessibility) Rochat et al. (2006) Depression among pregnant rural South African women undergoing HIV testing South Africa: rural Depression prevalence study N = 242 pregnant women EPDS, Mann-Whitney test B152: depression D9 perception of discrimination E1: health care and finance Schle- busch et al. (2010) HIV-infection as a self-reported risk factor for attempted suicide in South Africa South Africa: urban Quantitative study N = 112 PLHIV who committed suicide, gender not specified Self designed against DSM-IV-TR12 criteria B152: emotional e.g. depression Simbayi et al. (2007) Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa South Africa: urban Survey N = 1063 PLHIV N = 643 females AIDS related Stigma scale, self developed discrimination scale, CESD, SSQ self designed substance abuse questionnaire B152: internalized AIDS stigma and depression (cognitive and affective [CESD] E4: HIV discrimination E3: social support “B152”: substance abuse: alcohol abuse and drug abuse Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA 272 Continued Van as et al. (2009) The international classification of function disability and health (ICF) in adults visiting the HIV outpatient clinic at a regional hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa South Africa: urban Cross-sectional descriptive study N = 45 PLHIV 64% females WHO ICF checklist, dynamometry, Oxford muscle testing, goniometry All ICF domains Van Marle et al. (2009) HIV-occlusive vascular disease South Africa: urban Prospective clinical survey N = 154 PLHIV admitted to vascular unit, N = 20 females CD4 and CD8 T-cell counts, viral load, screening for other sexually transmitted infections; arterial Duplex Doppler scans, patient questionnaire B430: lifting and caring objects Wouters et al. (2009) Physical and emotional health outcomes after 12 months of public-sector antiretroviral treatment in the free state province of South Africa: a longitudinal study using structural equation modelling South Africa: urban and rural Longitudinal cross-sectional study N = 268 PLHIV ready for ART 67 % females Euro QoL 5D, subjective well-being (i.e. self-report)— assess five generic aspects of current health (mobility, self-care, limitation of activities, pain, and mood) B280: pain Wouters et al. (2007) Short-term physical and emotional health outcomes of public sector ART in the free state province of South Africa South Africa: urban and rural Cross sectional/ prevalence study N = 371 PLHIV ready for ART Gender unspecified EuroQoL 5D B152: physical health D4: mobility Yengopal et al. (2008) Do oral lesions associated with HIV affect quality of life? South Africa: urban Cross-sectional analytic study N = 150 PLHIV with and without oral manifestations of HIV, gender unspecified HIV Adult Oral Health Status Data Capture Sheet, OHIP B8: skin and others B280: pain B515: oral function problems related to problems with digesting food B3: speaking B2: looks, smell, taste B515: digestion Zeegers et al. (2010) Attention deficit hyperactivity and oppositional defiance disorder in HIV-infected South African children South Africa: urban Retrospective medical record review N = 100 HIV-infected children (≥5 years), 49 % girls SNAP-IV, Goodenough draw-a-person (DAP) B140: concentration/attention Myezwa et al. revealed impairments related to digestive, metabolic or endocrine systems in 83.9% of their sample. Similarly in the study by van As et al., 44% of the sam- ple experienced digestive, metabolic or endocrine prob- lems [25,26]. Julius et al. indicated a prevalence of dia- betes of 20.4%, with 16.8% obese and 28.6% overweight in the sample [43], although these data were not com- pared to HIV-negative controls. Genitourinary and reproductive function (b6): Four studies reported data on functions of the genitourinary and reproductive systems. Van As et al. [26] showed that 31% of the sample experienced genitourinary or repro- ductive problems. Bhat et al. [38] reported problems with sexual functions in 8.9% of their sample of 168 partici- pants. Renal function was explored in larger trials. Fra- ney et al. reported renal problems in 1.3% of their sam- ple of 2189 PLHIV who are on treatment. Both Franey et al. and Jao et al. [44,45] found increased renal impair- ment at ART onset with men more affected than women. Muscle function and related tissue (b7): Nine arti- cles (describing eight studies) provided data on the extent of impairments related to muscle tone, power and motor development as well as the functions of the skin and re- lated structures. Myezwa et al. revealed neuromuscu-  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 273 Figure 3. Proportion of wome n and men in inc lude d studies. loskeletal movement impairment in 73.8% and muscle power loss in 75% of their sample [25]. Van As et al. reported that 31% of the sample experienced skin im- pairments and for 27% the most common neuromuscular problem was loss of muscle power. Focusing on fine and gross motor skills, Ferguson et al. [46,47] reported motor delay in their study of 86 HIV-positive children with matched controls. Significant motor delay was 66.7% in the HIV-positive sample, which was significantly higher than the age-matched compared. Bhat et al. reported problems with skin rashes in 8.3% and with hair loss in 7.7% of the sample. Franey et al., Friend-du Preez et al. Oketcha et al. and Yengopal et al. also reported problems associated with the function of skin and related structures [40-42,44]. 4.4. Activity Limitations and Participation Restrictions In contrast to the level of impairment, far less data were reported on the ICF levels of activity or participation. Studies that did report on these concepts are described below according to the ICF domains of mobility, self- care, and community, social and civic life. Several stud- ies also reported elements of “learning and applying knowledge”, which includes problem-solving, or “com- munication”. There was little information related to con- textual factors, such as access to services, technology, support and relationships and attitudes. Mobility (d4): Eight studies reported problems with mobility, mainly for PLHIV on treatment. Myezwa et al. [7,25] found mobility limitations in 56.4% of the sample, while van As et al. [26], using the same framework, found mobility limitations in 40% of the sample, espe- cially lifting and carrying. These complaints were asso- ciated with mild difficulty undertaking multiple tasks without assistance. Similarly, Nair and Patel reported de- creased physical functioning as measured by mobility. The studies by Wouthers et al., Booysen et al., Kakinami et al., and McInnerney et al. [32,33,48-50] reported im- provement in mobility upon initiating ART, with partici- pants followed for the first 12 or 18 months. The study by Karbore et al. [51] showed that among participants not receiving community services (i.e., food and home- based care), the mean physical functioning score in- creased by 1.6 points to 11.2 at 12 months but then de- creased to 10.6 at 18 months, while the group which re- ceived community services improved continuously. Self-care (d5): Three studies described data on self- care. Oketch et al. [42] reported minor (80.6%), moder- ate (14%), or severe (5.4%) problems with self-care. The studies by Booysen et al. [48], Jelsma et al. [15] and Kakinamis et al. [49] each showed improvements in the domain of self-care during the first year of ART. Data over a longer period were not available. Community, social and civic life (d9): Two studies reported data in this domain. Myezwa et al. reported that activity limitations were present in major life areas (55.1%), and community, social and civic life (50%), and that many of those activity limitations were associated with impairments [25]. They also reported that activity limitations or participation restrictions, including diffi- culties with general tasks and demands, interpersonal re- lationships, domestic life, and community, social and ci- vic life, were closely associated with barriers in obtaining products for personal use and in using technology. Van As et al. [26] showed that participants had challenges in major life areas (58%), and that interpersonal interactions and relationships (56%) were most common. Of these, challenges related to school, higher education and remu- nerative employment were specifically problematic. 4.5. Linkages among Impairment, Activity and Participation Levels Few studies explored how the different domains might be associated with each other. Nair et al. [52] reported that Perceived Social Support was correlated with vitality (r = 0.28, p < 0.01) and mental health (r = 0.26, p < 0.01), suggesting that high levels of social support from family and friends are related to good mental health in the par- ticipants. Gupta et al. [53] reported that depression was associated with stigma and relationship problems. Nair et al. also reported how a low score on the SF-36 Bodily Pain Scale was associated with compromised ability to work. The four studies that addressed contextual factors re- ported that certain impairments or activity limitations were associated with domains such as access to products and technology [25,31,54]. Simbavi et al. demonstrated how challenges within the ICF domain of emotional functions were related to problems with support and rela- tionships [55]. Finally, linkages between dimensions of disability and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 274 ART adherence received little attention in the available literature. Bhat et al. [38] reported that reasons given by participants for ART adherence problems included that they “simply forgot” (41.3%) or were attributed to the “side effects” of ART (50.8%). They also reported that HIV-related impairments or “side effects” were greatly increased in the portion of the sample that did not adhere to treatment, and that the reason for skipping the dose was often because of these side effects. 5. Discussion This is the first analysis to systematically review the lit- erature on HIV-related outcomes among people living with HIV in hyper-endemic countries within a disability framework. In the era of enhanced access to ART, many people will be living longer lives but with potential epi- sodes of disability resulting from HIV, HIV-related con- ditions, and/or as side effects of ART. It is crucial to un- derstand the extent of disability among people living with HIV in high-prevalence settings in order to inform choices regarding care, policy and research. These find- ings add to the growing body of literature that calls for attention to disability in high HIV-prevalence settings [4-7,16,56-59]. In particular, this scoping review demon- strates that much is already known about impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions experi- enced by people living with HIV in hyper-endemic coun- tries, but that key gaps in understanding remain. 5.1. What Is Known and Unknown about HIV-Related Disability in Hyper-Endemic Countries? This review identified literature that reports data on all concepts within the ICF schematic of disability (see Fig- ure 1), but in vastly unequal ways. By far, impairments in body structure and function comprise the majority of data available on disability experienced by people living with HIV in hyper-endemic countries. Most of the in- cluded studies report on some form of impairment, and all of the first level ICF impairment codes were ad- dressed except for one (“b3 Voice”). Particularly striking is the extent of data reported on impairments related to mental functions, which is an area of disability that can be overshadowed by physical concerns. This mirrors the findings of the population-based disability prevalence study of people living with HIV in British Columbia, in which the prevalence of mental impairments was 78% [12]. Rusch et al. also reported a high prevalence of con- current impairments, with a median of 7 impairments and approximately one-third of the sample experiencing more than ten impairments in the past month [12]. Similarly, our scoping study found multiple diverse impairments being reported. However, a striking finding is that none of the included articles reported data on the sensory functions of hearing and seeing, despite the fact that HIV and its opportunistic diseases can cause these impair- ments [60]. Furthermore, few studies addressed functions of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, even though tuberculosis and lipodystrophy are well-described health conditions associated with HIV. Whereas Rusch et al. also reported high rates of activ- ity limitations (80%) and participation restrictions (93), few studies included in this review addressed these levels of concern. Studies that did attend to these issues focused primarily on self-care, mobility and engagement in com- munity. While some studies indicated improvement of these areas following onset of ART, [15,48-50] others reported that a large number of PLHIV continue to ex- perience challenges related to these areas [61,62]. A lon- gitudinal study using a comprehensive disability measure could enhance understanding of the shifting experience of activity limitations and participation restrictions over time. In addition to these areas, future research is needed to better understand domains not commonly included in outcome studies, such as communication, domestic life, and education. The review also found very little data on contextual factors, which include availability of assistance devices, rehabilitation and social support in the context of HIV. The importance of these environmental factors can be crucial in mitigating activity limitations and participation restrictions. We note that data on contextual factors may more commonly be found in qualitative studies; however, the adage that “what gets counted counts” emphasizes the importance of quantifying outcomes across the holis- tic experience of disability in order to inform action. A key direction for future research is investigation of linkages between HIV-related disability and ART ad- herence. The multi-faceted challenge could gain from better understanding how various dimensions of disabil- ity contribute to ART adherence or attrition. We also note the dearth of data related to disability among HIV- positive children and youth, indicating another priority for future research. 5.2. Contributions of a Disability Framework to HIV Research An issue that arises from this review relates to the bio- medical emphasis in HIV outcomes studies. The articles with the largest samples and thus the greatest opportunity to draw conclusions (at least within this research para- digm) typically focused on particular clinical concerns, without taking into account how these diagnoses might influence or be connected to other areas of health or life. It is therefore unsurprising that responses to HIV care are Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 275 largely medicalized and often do not include or privilege rehabilitation [3] or other services that could significantly improve quality of life. This is not to diminish the im- portance of biomedical approaches, and medicines in particular, to the experience of living with HIV. However, we argue that the time has come to elevate the health and life-related consequences of living with HIV to the status given to surrogate markers of disease progression. Lack of data can lead to lack of responses that could strengthen HIV care. An advantage of the ICF is the way that each concept in the schematic can influence and be influenced by the other concepts, as illustrated by the double-headed arrows (see Figure 1). This framing ac- knowledges the complexity of life and challenges re- searchers to consider not only the concepts but their in- teractions. Only a few studies explored interactions be- tween concepts, yet these findings provide important insights not only on the experience of disability but also on opportunities for providing support. For example, Nair et al. reported on links between pain and ability to work, pointing to the potential that pain management might play in reducing attrition from work. A more com- prehensive approach to HIV care that includes broader concerns with function and activity is needed to inform other responses, such as rehabilitation and community interventions that could complement ART. Using a dis- ability lens in the context of HIV has the potential to connect the medical field to others that address opportu- nities to promote human activity and participation. By far the most comprehensive approach to disability and HIV in this scoping review was undertaken in the studies by Myezwa et al. and van As et al. Both studies used the ICF checklist as a tool of investigation. As a result, these two articles provide data across impairment, activity limitations and participation restriction levels like no other study in this review. Myezwa et al. were able to demonstrate that difficulties with general tasks and demands, interpersonal relationships, domestic life and/or community, social and civic life are associated with barriers in obtaining products for personal use and using technology. This highlights the importance of assessing contextual factors as well. Studies that used the ICF pro- vide a more holistic understanding of the experience of living with HIV, and a link between the diagnoses of health conditions on the one hand, and the identification of impairments, activity limitations and participation re- strictions on the other. 5.3. Limitations The extent to which our review’s findings can be gener- alised to reflect HIV-related disability in hyper-endemic countries is limited in three important ways: geographic and location issues, constraints of sampling approaches, and concerns with sample sizes. First, 78% of the studies were conducted in South Af- rica in contrast to just one study in Zimbabwe and none in Lesotho or Swaziland. Furthermore, all studies were conducted in public health care settings, which are more likely to include participants with lower socioeconomic status and less access to education and resources. As such, study results related to experiences of disability could be influenced by factors other than HIV. Future research needs to include matched control groups to clar- ify the degree to which disability is HIV-related. Secondly, most studies in this sample used conven- ience sampling; only three studies (7%) used random sampling. As such, findings are likely to reflect the kinds of individuals who more frequently attend the recruit- ment settings. Most of the studies in this review included more women than men. HIV prevalence in Southern Af- rica is higher in women, and women may be more likely than men to seek health services. As such, results may erroneously give the impression of certain experiences being more common among women than men. Con- versely, the study by van Marle et al. included more males than females [63]. However, the study focused on HIV-occlusive vascular disease, which may be more prevalent in men in the general population. Therefore, it would be inappropriate to make claims about gendered differences in the extent of disability related to this con- dition. Thirdly, the studies in this review with the largest sample sizes (n > 1000) focused on particular health con- ditions, such as renal failure or neurological disorders. Studies that took a broad view of disability had relatively small samples (n < 100). As such, we may draw only li- mited conclusions about the extent of disability in PLHIV. A population-based prevalence study of disabil- ity (understood comprehensively, as in the ICF) would mitigate each of these methodological concerns. 6. Conclusion This scoping review described the literature on disability experienced by people living with HIV in hyper-epi- demic countries since expanded access to ART in the mid-2000s. A key innovation in this study is the way that we have conceptualized HIV-related disability in South- ern Africa using the World Health Organization’s ICF. We hope that this review will prompt consideration of disability issues and inclusion of people with disabilities in our collective thinking about HIV in the region. 7. Acknowledgements and Funding We thank Peggy-Rae Carswell for her support as a re- search assistant. Stephanie Nixon is supported by the Ca- nadian Institutes for Health Research. Ilaria Regondi’s Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 276 time at HEARD was made possible by the UK’s Over- seas Development Institute. REFERENCES [1] UNAIDS, “Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Glo- bal AIDS Epidemic 2010,” UNAIDS, Geneva, 2010. http://www.unaids.org/documents/20101123_GlobalRepo rt_Foreword_em.pdf [2] UNAIDS, “UNIADS World AIDS Day Report 2011. How to Get to Zero: Faster. Smarter. Better,” UNAIDS, Geneva, 2011. [3] G. Meintjes, G. Maartens, A. Boulle, F. Conradie, E. Goemaere, E. Hefer, D. Johnson, M. Mathe, Y. Moosa, R. Osih, T. Rossouw, G. van Cutsem, E. Variava, F. Venter and D. Spencer, “Guidelines for Antiretroviral Therapy in Adults,” Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2012, pp. 114-130. [4] S. Nixon, J. Hanass-Hancock, A. Whiteside and T. Bar- nett, “The Increasing Chronicity of HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa: Re-Thinking ‘HIV as a Long-Wave Event’ in the Era of Widespread Access to ART,” Globalisation and Health, Vol. 7, No. 41, 2011, pp. 1-5. http://www.globalizationandhealth.com/content/7/1/41 [5] K. O’Brien, A. M. Bayoumi, C. Strike, N. Young and A. M. Davis, “Exploring Disability from the Perspective of Adults Living with HIV/AIDS: Development of a Con- ceptual Framework,” Health and Quality of Life Out- comes, Vol. 6, 2008, p. 76. [6] K. O’Brien, A. Wilkins, E. Zack and P. Solomon, “Scop- ing the Field: Identifying Key Research Priorities in HIV and Rehabilitation,” AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2010, pp. 448-458. [7] H. Myezwa, C. M. Buchalla, J. Jelsma and A. Stewart, “HIV/AIDS: Use of the ICF in Brazil and South Africa —Comparative Data from Four Cross-Sectional Studies,” Physiotherapy, Vol. 97, No. 1, 2011, pp. 17-25. [8] S. Nixon and C. Cott, “Shifting Perspectives: Reconcep- tualizing HIV Disease in a Rehabilitation Framework,” Physiotherapy Canada, Vol. 52, 2000, pp. 189-197. [9] J. Hanass-Hancock and S. Nixon, “The Fields of HIV and Disability: Past, Present and Future,” Journal of the In- ternational AIDS Society, Vol. 12, No. 28, 2009, pp. 1-8. http://www.jiasociety.org/series/hiv_aids_and_disability [10] WHO, “ICF, Towards a Common Language for Func- tioning, Disability and Health,” 2002. [11] K. O’Brien, A. M. Davis, C. Strike, N. L. Young and A. M. Bayoumi, “Putting Episodic Disability into Context: A Qualitative Study Exploring Factors that Influence Dis- ability Experienced by Adults Living with HIV/AIDS,” Journal of the International AIDS Society, Vol. 12, No. 30, 2009, pp. 1-7. www.jiasociety.org/content/12/1/30 [12] M. Rusch, S. Nixon, A. Schilder, P. Braitstein, K. Chan, and R. Hogg, “Impairments, Activity Limitations and Participation Restrictions: Prevalence and Associations among Persons Living with HIV/AIDS in British Colum- bia,” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2004, p. 46. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-2-46 [13] M. Rusch, S. Nixon, A. Schilder, P. Braitstein, K. Chan, and R. Hogg, “Prevalence of Activity Limitation among Persons Living with HIV/AIDS in British Columbia,” Canadian Journal of Public Health, Vol. 95, No. 6, 2004, pp. 437-440. [14] Canadian Working Group on HIV and Rehabilitation, “HIV, Disability and Rehabilitation: Promoting Quality of Life through Research, Education and Cross-Sector partnership. Strategic Plan: 2010-2013,” 2010. http://www.hivandrehab.ca/EN/about_us/documents/CW GHRStrategicPlanFinal.pdf [15] J. Jelsma, E. Maclean, J. Hughes, X. Tinise and M. Darder, “An Investigation into the Health-Related Quality of Life of Individuals Living with HIV Who Are Receiv- ing HAART,” AIDS Care, Vol. 17, No. 5, 2005, pp. 579- 588. doi:10.1080/09540120412331319714 [16] J. Jelsma, N. Rbrauer, A. Snoek and I. Sykes, “A Pilot Study to Investigate the Use of the ICF in Documenting Levels of Function and Disability in People Living with HIV,” South African Journal of Physiotherapy, Vol. 62, No. 7, 2006, pp. 7-13. [17] J. Hanass-Hancock, S. Nixon, H. Myeswa, L. Van Eg- gerat and A. Gibbs, “‘Nathi Singabantu’ an Exploratory Study of HIV-related Disability in KwaZulu-Natal,” HEARD, Durban, 2012. [18] T. B. Üstün, S. Chatterji, J. E. Bickenbach, T. T. I. Robert, R. Room, J. Rehm and S. Shekhar, “Disability and Cul- ture: Universalism and Diversity,” Hogrefe & Huber, Se- attle, 2001. [19] WHO, “ICF Checklist. Version 2 1a, Clinician Form,” WHO, Geneva, 2003. [20] M. Nyirenda, S. Chatterji, J. Falkingham, P. Mutevedz, V. Hosegood, M. Evandrou, P. Kowal and M.-L. Newell, “An Investigation of Factors Associated with the Health and Well-Being of HIV-Infected or HIV-Affected Older People in Rural South Africa,” BMC Public Health, Vol. 12, No. 259, 2012, pp. 1471-2458. [21] H. Arksey and L. O’Malley, “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework,” International Journal of Social Research Methodology, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2005, pp. 19-32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616 [22] D. Levac, H. Colquhoun and K. O’Brien, “Scoping Stud- ies: Advancing the Methodology,” Implementation Sci- ence, Vol. 1, 2010, p. 69. [23] D. Denyer and D. Tranfield, “Using Qualitative Research Synthesis to Build an Actionable Knowledge Base,” Management Decision, Vol. 44, No. 2, 2006, pp. 214- 227. doi:10.1108/00251740610650201 [24] D. Tranfield, D. Denyer and P. Smart, “Towards a Metho- dology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review,” British Journal of Management, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2003, pp. 207- 222. [25] H. Myezwa, A. Stewart, E. Musenge and P. Nesara, “As- sessment of HIV-Positive In-Patients Using the Interna- tional Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, Johannes- burg,” African Journal of AIDS Research, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2009, pp. 93-106. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 277 [26] M. Van As, H. Myezwa, A. Stewart, D. Maleka, and E. Musenge, “The International Classification of Function- ing Disability and Health (ICF) in Adults Visiting the HIV Outpatient Clinic at a Regional Hospital in Johan- nesburg, South Africa,” AIDS Care, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2009, pp. 50-58. doi:10.1080/09540120802068829 [27] M. Freeman, N. Nkomo, Z. Kafaar and K. Kelly, “Factors Associated with Prevalence of Mental Disorder in People Living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa,” AIDS Care, Vol. 19, No. 10, 2007, pp. 1201-1209. doi:10.1080/09540120701426482 [28] A. Kagee and L. Martin, “Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety among a Sample of South African Patients Liv- ing with HIV,” AIDS Care, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2010, pp. 159- 165. doi:10.1080/09540120903111445 [29] M. Moosa, F. Jeenah and M. Vorster, “HIV in South Af- rica—Depression and CD4 Count,” South African Jour- nal of Psychiatry, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2005, pp. 12-15. [30] L. Myer, J. Smit, L. Le Roux, S. Parker, D. J. Stein and S. Seedat, “Common Mental Disorders among HIV-Infected Individuals in South Africa: Prevalence, Predictors, and Validation of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scales,” AIDS Pa- tient Care and STDs, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2008, pp. 147-158. [31] T. J. Rochat, L. M. Richter, H. A. Doll, N. P. Buthelezi, A. Tomkins and A. Stein, “Depression among Pregnant Rural South African Women Undergoing HIV Testing,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 295, No. 12, 2006, pp. 1376-1378. doi:10.1001/jama.295.12.1376 [32] E. Wouters, C. Heunis, D. van Rensburg and H. Meule- mans, “Physical and Emotional Health Outcomes after 12 Months of Public-Sector Antiretroviral Treatment in the Free State Province of South Africa: A Longitudinal Study Using Structural Equation Modelling,” BMC Pub- lic Health, Vol. 9, No. 103, 2009, pp. 1-8. [33] E. Wouters, H. Meulemans, H. C. Van Rensburg, J. C. Heunis and D. Mortelmans, “Short-Term Physical and Emotional Health Outcomes of Public Sector ART in the Free State province of South Africa,” Quality of Life Re- search, Vol. 16, No. 9, 2007, pp. 1461-1471. doi:10.1007/s11136-007-9260-y [34] R. Patel, S. Kassaye, C. Gore-Felton, G. Wyshak, G. Kadzirange, G. Woelk and D. Katzenstein, “Quality of Life, Psychosocial Health, and Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV-Positive Women in Zimbabwe,” AIDS Care, Vol. 21, No. 12, 2009, pp. 1517-1527. doi:10.1080/09540120902923055 [35] K. Lawler, M. Mosepele, S. Ratcliffe, E. Seloilwe, K. Steele, R. Nthobatsang and A. Steenhoff, “Neurocogni- tive Impairment among HIV-Positive Individuals in Bot- swana: A Pilot Study,” Journal of the International AIDS Society, Vol. 13, 2010, p. 15. [36] J. A. Joska, D. S. Fincham, D. J. Stein, R. H. Paul and S. Seedat, “Clinical Correlates of HIV-Associated Neuro- cognitive Disorders in South Africa,” AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2010, pp. 371-378. doi:10.1007/s10461-009-9538-x [37] K. Lawler, K. Jeremiah, M. Mosepele, S. J. Ratcliffe, C. Cherry, E. Seloilwe and A. P. Steenhoff, “Neurobeha- vioral Effects in HIV-Positive Individuals Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) in Ga- borone, Botswana,” PLoS One, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2011, Arti- cle ID: e17233. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017233 [38] V. G. Bhat, M. Ramburuth, M. Singh, O. Titi, A. P. An- tony, L. Chiya, E. M. Irusen, P. P. Mtyapi, M. E. Mofoka, A. Zibeke, L. A. Chere-Sao, N. Gwadiso, N. C. Sethathi, S. R. Mbondwana and M. Msengana, “Factors Associated with Poor Adherence to Anti-Retroviral Therapy in Pa- tients Attending a Rural Health Centre in South Africa,” European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, Vol. 29, No. 8, 2010, pp. 947-953. doi:10.1007/s10096-010-0949-4 [39] J. Maritz, M. Benatar, J. A. Dave, T. B. Harrison, M. Badri, N. S. Levitt and J. M. Heckmann, “HIV Neuropa- thy in South Africans: Frequency, Characteristics, and Risk Factors,” Muscle Nerve, Vol. 41, No. 5, 2010, pp. 599-606. [40] V. Yengopal and S. Naidoo, “Do Oral Lesions Associated with HIV Affect Quality of Life?” Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endo- dontology, Vol. 106, No. 1, 2008, pp. 66-73. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.12.024 [41] N. Friend-du Preez and K. Peltzer, “HIV Symptoms and Health-Related Quality of Life Prior to Initiation of HAART in a Sample of HIV-Positive South Africans,” AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 14, No. 6, 2010, pp. 1437-1447. doi:10.1007/s10461-009-9566-6 [42] J. A. Oketch, M. Paterson, E. W. Maunder and N. C. Rollins, “Too Little, Too Late: Comparison of Nutritional Status and Quality of Life of Nutrition Care and Support Recipient and Non-Recipients among HIV-Positive Adults in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa,” Health Policy, Vol. 99, No. 3, 2011, pp. 267-276. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.08.018 [43] A. Kagee, “Psychological Distress among Persons Living with HIV, Hypertension, and Diabetes,” AIDS Care, Vol. 22, No. 12, 2010, pp. 1517-1521. doi:10.1080/09540121.2010.484458 [44] C. Franey, D. Knott, T. Barnighausen, M. Dedicoat, A. Adam, R. J. Lessells, M. L. Newell and G. S. Cooke, “Renal Impairment in a Rural African Antiretroviral Pro- gramme,” BMC Infectious Disease, Vol. 9, No. 143, 2009, pp. 1-8. [45] J. Jao, W. Lo, P. L. Toro, C. Wyatt, D. Palmer, E. J. Abrams, R. J. Carter and M. T.-P. Initiative, “Factors Associated With Decreased Kidney Function in HIV-In- fected Adults Enrolled in the MTCT-Plus Initiative in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Journal of Acquired Immune Defi- ciency Syndromes, Vol. 57, No. 1, 2011, pp. 40-45. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821008eb [46] G. Ferguson and J. Jelsma, “The Prevalence of Motor Delay among HIV Infected Children Living in Cape Town, South Africa,” International Journal of Reha- bilitation Research, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2009, pp. 108-114. doi:10.1097/MRR.0b013e3283013b34 [47] J. Jelsma and G. Ferguson, “Motor Development in Chil- dren Living within Resource Poor Areas of Western Cape,” Physiotherapy, Vol. 63, No. 2, 2007, pp. 35-40. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA 278 [48] F. Booysen, H. Van Rensburg, M. Bachmann, G. Lou- wagie and L. Fairall, “The Heart in HAART: Quality of Life of Patients Enrolled in the Public-Sector Antiretro- viral Treatment Programme in the Free State Province of South Africa,” Social Indicators Research, Vol. 81, 2007, pp. 283-329. [49] L. Kakinami, G. de Bruyn, P. Pronyk, L. Mohapi, N. Tshabangu, M. Moshabela, J. McIntyre and N. A. Mar- tinson, “The Impact of Highly Active Antiretroviral The- rapy on Activities of Daily Living in HIV-Infected Adults in South Africa,” AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2011, pp. 823-831. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9776-y [50] P. A. McInerney, B. P. Ncama, D. Wantland, B. R. Bhengu, C. McGibbon, S. M. Davis, I. B. Corless and P. K. Nicholas, “Quality of Life and Physical Functioning in HIV-Infected Individuals Receiving Antiretroviral Ther- apy in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa,” Nursing & Health Sciences, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2008, pp. 266-272. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2008.00410.x [51] I. Kabore, J. Bloem, G. Etheredge, W. Obiero, S. Wanless, P. Doykos, P. Ntsekhe, N. Mtshali, E. Afrikaner, R. Sayed, J. Bostwelelo, A. Hani, T. Moshabesha, A. Kalaka, J. Mameja, N. Zwane, N. Shongwe, P. Mtshali, B. Mohr, A. Smuts and A. Tiam, “The Effect of Community-Based Support Services on Clinical Efficacy and Health-Related Quality of Life in HIV/AIDS Patients in Resource-Limi- ted Settings in Sub-Saharan Africa,” AIDS Patient Care and STDs, Vol. 24, No. 9, 2010, pp. 581-594. doi:10.1089/apc.2009.0307 [52] K. M. Nair and N. Muthukrishna, “Psychological Well- Being and Health Related Quality of Life among a Group of Low-Income Women Living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa,” Journal of Psychology in Africa, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2009, pp. 517-529. [53] R. Gupta, M. Dandu, L. Packel, G. Rutherford, K. Leiter, N. Phaladze, F. P. Korte, V. Iacopino and S. D. Weiser, “Depression and HIV in Botswana: A Population-Based Study on Gender-Specific Socioeconomic and Behavioral Correlates,” PLoS One, Vol. 5, No. 12, 2010, Article ID: e14252. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014252 [54] K. Peltzer and N. Phaswana-Mafuya, “Health-Related Quality of Life in a Sample of HIV-Infected South Afri- cans,” African Journal of AIDS Research, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2008, pp. 209-218. [55] L. C. Simbayi, S. Kalichman, A. Strebel, A. Cloete, N. Henda and A. Mqeketo, “Internalized Stigma, Discrimi- nation, and Depression among Men and Women Living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa,” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 64, No. 9, 2007, pp. 1823-1831. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006 [56] S. Nixon, L. Forman, J. Hanass-Hancock, M. Mac-Seing, N. Munyanukato, H. Myezwa and C. Retis, “Rehabilita- tion: A Crucial Component in the Future of HIV Care and Support,” South African Journal of HIV Medicine, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2011, pp. 12-16. [57] J. Jelsma, N. Davids and G. Ferguson, “The Motor De- velopment of Orphaned Children with and without HIV: Pilot Exploration of Foster Care and Residential Place- ment,” BMC Pediatrics, Vol. 11, 2011, p. 11. [58] Canadian Working Group on HIV and Rehabilitation, “E-Module for Evidence-Informed HIV Rehabilitation,” 2011. [59] R. Brandt, “The Mental Health of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: A Systematic Review,” African Journal of AIDS Research, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2009, pp. 123- 133. [60] HIV Insight, “Ophthalmic Manifestations of HIV,” 2013. http://www.delta-search.com/?affID=110825&tt=230113 _srchd_0413_1&babsrc=HP_ss&mntrId=d2ba5ac600000 0000000ec55f976db6b [61] H. Myezwa, C. M. Buchalla, J. Jelsma and A. Stewart, “HIV/AIDS: Use of the ICF in Brazil and South Af- rica—Comparative Data from Four Cross-Sectional Stud- ies,” Physiotherapy, Vol. 97, No. 1, 2011, pp. 17-25. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2010.08.015 [62] M. Van As, H. Myezwa, A. Stewart, D. Maleka and E. Musenge, “The International Classification of Function Disability and Health (ICF) in Adults Visiting the HIV Outpatient Clinic at a Regional Hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa,” AIDS Care, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2009, pp. 50- 58. [63] J. van Marle, P. P. Mistry and K. Botes, “HIV-Occlusive Vascular Disease,” South African Journal of Surgery, Vol. 47, No. 2, 2009, pp. 36-42.  HIV-Related Disability in HIV Hyper-Endemic Countries: A Scoping Review 279 List of Abbreviations ARV: Antiretroviral ART: Antiretroviral therapy HAART: Highly active antiretroviral therapy HAND: HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health IHDS: International HIV dementia scale PLHIV: People living with HIV PTSD: Post traumatic stress disorder SF-36: Short Form 36 STD: Sexual Transmitted Disease SRQ-20: Self Reported Questionaire 20 QAL: Quality of Life Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA