Hepatitis E Virus Infection in HIV Positive ART Naïve and Experienced Individuals in Nigeria 219

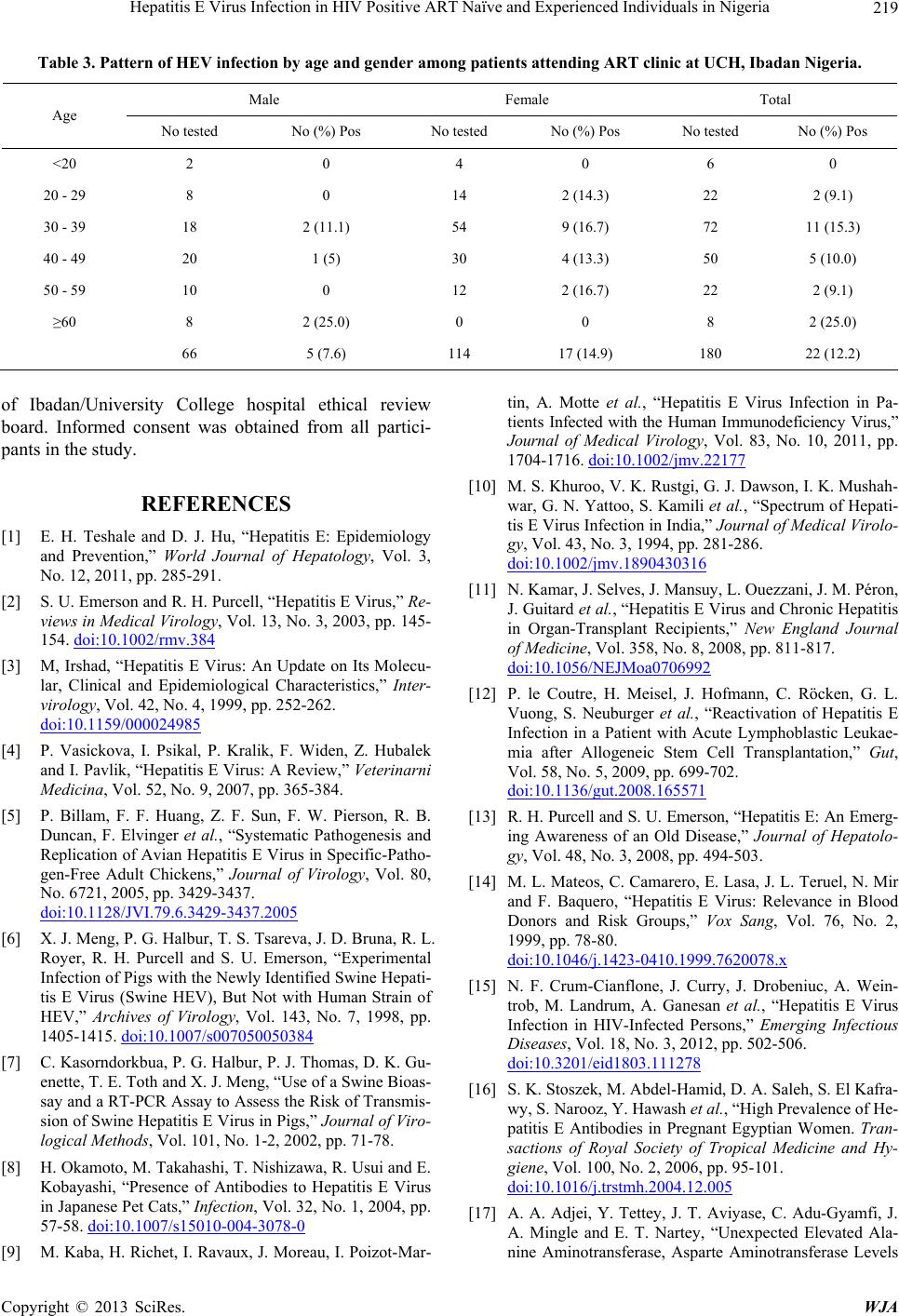

Table 3. Pattern of HEV infection by age and gender among patients attending ART clinic at UCH, Ibadan Nigeria.

Male Female Total

Age

No tested No (%) Pos No tested No (%) Pos No tested No (%) Pos

<20 2 0 4 0 6 0

20 - 29 8 0 14 2 (14.3) 22 2 (9.1)

30 - 39 18 2 (11.1) 54 9 (16.7) 72 11 (15.3)

40 - 49 20 1 (5) 30 4 (13.3) 50 5 (10.0)

50 - 59 10 0 12 2 (16.7) 22 2 (9.1)

≥60 8 2 (25.0) 0 0 8 2 (25.0)

66 5 (7.6) 114 17 (14.9) 180 22 (12.2)

of Ibadan/University College hospital ethical review

board. Informed consent was obtained from all partici-

pants in the study.

REFERENCES

[1] E. H. Teshale and D. J. Hu, “Hepatitis E: Epidemiology

and Prevention,” World Journal of Hepatology, Vol. 3,

No. 12, 2011, pp. 285-291.

[2] S. U. Emerson and R. H. Purcell, “Hepatitis E Virus,” Re-

views in Medical Virology, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2003, pp. 145-

154. doi:10.1002/rmv.384

[3] M, Irshad, “Hepatitis E Virus: An Update on Its Molecu-

lar, Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics,” Inter-

virology, Vol. 42, No. 4, 1999, pp. 252-262.

doi:10.1159/000024985

[4] P. Vasickova, I. Psikal, P. Kralik, F. Widen, Z. Hubalek

and I. Pavlik, “Hepatitis E Virus: A Review,” Veterinarni

Medicina, Vol. 52, No. 9, 2007, pp. 365-384.

[5] P. Billam, F. F. Huang, Z. F. Sun, F. W. Pierson, R. B.

Duncan, F. Elvinger et al., “Systematic Pathogenesis and

Replication of Avian Hepatitis E Virus in Specific-Patho-

gen-Free Adult Chickens,” Journal of Virology, Vol. 80,

No. 6721, 2005, pp. 3429-3437.

doi:10.1128/JVI.79.6.3429-3437.2005

[6] X. J. Meng, P. G. Halbur, T. S. Tsareva, J. D. Bruna, R. L.

Royer, R. H. Purcell and S. U. Emerson, “Experimental

Infection of Pigs with the Newly Identified Swine Hepati-

tis E Virus (Swine HEV), But Not with Human Strain of

HEV,” Archives of Virology, Vol. 143, No. 7, 1998, pp.

1405-1415. doi:10.1007/s007050050384

[7] C. Kasorndorkbua, P. G. Halbur, P. J. Thomas, D. K. Gu-

enette, T. E. Toth and X. J. Meng, “Use of a Swine Bioas-

say and a RT-PCR Assay to Assess the Risk of Transmis-

sion of Swine Hepatitis E Virus in Pigs,” Journal of Viro-

logical Methods, Vol. 101, No. 1-2, 2002, pp. 71-78.

[8] H. Okamoto, M. Takahashi, T. Nishizawa, R. Usui and E.

Kobayashi, “Presence of Antibodies to Hepatitis E Virus

in Japanese Pet Cats,” Infection, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2004, pp.

57-58. doi:10.1007/s15010-004-3078-0

[9] M. Kaba, H. Richet, I. Ravaux, J. Moreau, I. Poizot-Mar-

tin, A. Motte et al., “Hepatitis E Virus Infection in Pa-

tients Infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus,”

Journal of Medical Virology, Vol. 83, No. 10, 2011, pp.

1704-1716. doi:10.1002/jmv.22177

[10] M. S. Khuroo, V. K. Rustgi, G. J. Dawson, I. K. Mushah-

war, G. N. Yattoo, S. Kamili et al., “Spectrum of Hepati-

tis E Virus Infection in India,” Journal of Medical Virolo-

gy, Vol. 43, No. 3, 1994, pp. 281-286.

doi:10.1002/jmv.1890430316

[11] N. Kamar, J. Selves, J. Mansuy, L. Ouezzani, J. M. Péron,

J. Guitard et al., “Hepatitis E Virus and Chronic Hepatitis

in Organ-Transplant Recipients,” New England Journal

of Medici ne, Vol. 358, No. 8, 2008, pp. 811-817.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706992

[12] P. le Coutre, H. Meisel, J. Hofmann, C. Röcken, G. L.

Vuong, S. Neuburger et al., “Reactivation of Hepatitis E

Infection in a Patient with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukae-

mia after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation,” Gut,

Vol. 58, No. 5, 2009, pp. 699-702.

doi:10.1136/gut.2008.165571

[13] R. H. Purcell and S. U. Emerson, “Hepatitis E: An Emerg-

ing Awareness of an Old Disease,” Journal of Hepatolo-

gy, Vol. 48, No. 3, 2008, pp. 494-503.

[14] M. L. Mateos, C. Camarero, E. Lasa, J. L. Teruel, N. Mir

and F. Baquero, “Hepatitis E Virus: Relevance in Blood

Donors and Risk Groups,” Vox Sang, Vol. 76, No. 2,

1999, pp. 78-80.

doi:10.1046/j.1423-0410.1999.7620078.x

[15] N. F. Crum-Cianflone, J. Curry, J. Drobeniuc, A. Wein-

trob, M. Landrum, A. Ganesan et al., “Hepatitis E Virus

Infection in HIV-Infected Persons,” Emerging Infectious

Diseases, Vol. 18, No. 3, 2012, pp. 502-506.

doi:10.3201/eid1803.111278

[16] S. K. Stoszek, M. Abdel-Hamid, D. A. Saleh, S. El Kafra-

wy, S. Narooz, Y. Hawash et al., “High Prevalence of He-

patitis E Antibodies in Pregnant Egyptian Women. Tran-

sactions of Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hy-

giene, Vol. 100, No. 2, 2006, pp. 95-101.

doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.12.005

[17] A. A. Adjei, Y. Tettey, J. T. Aviyase, C. Adu-Gyamfi, J.

A. Mingle and E. T. Nartey, “Unexpected Elevated Ala-

nine Aminotransferase, Asparte Aminotransferase Levels

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. WJA