Impact of Ocular Compression on Ocular Surface Bacterial Contaminat i on

376

OC (approximately 30 mm Hg) for 15 ± 2 minutes using

a modified Honan’s balloon, and the control group (31

eyes of 31 patients) received retrobulbar anaesthesia

without the preoperative application of OC or digital

massage. In the control group, the patients’ eyes re-

mained closed for 15 ± 2 minutes after the anaesthesia

administration. Approval for accessing the patient health

records was obtained from the local research ethics

committee. Informed consent was obtained from each

patient. The study protocol and the safety and efficacy of

the intervention s were explained to all of the participants

prior to their enrolment.

2.2. Bacteriological Investigation

After the specified period of 15 ± 2 minutes and follow-

ing the device removal (study group only), the eyes were

opened, and bacterial cultures from the conjunctival sac

and lid margin were immediately initiated using sterile

cotton swabs moistened with sterile saline solution. In

addition, swabbing was performed for the lower lid

margin by rolling the swab from the lateral canthus up to

the lacrimal point. The samples from each eye were

placed in separate tubes containing thioglycolate broth

and incubated at 37˚C for 24 h. The bacterial isolation

and identification were performed using standard me-

thods, as described elsewhere [4].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The chi-squared test was used to compare the studied

variables. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statis-

tically significant.

3. Results

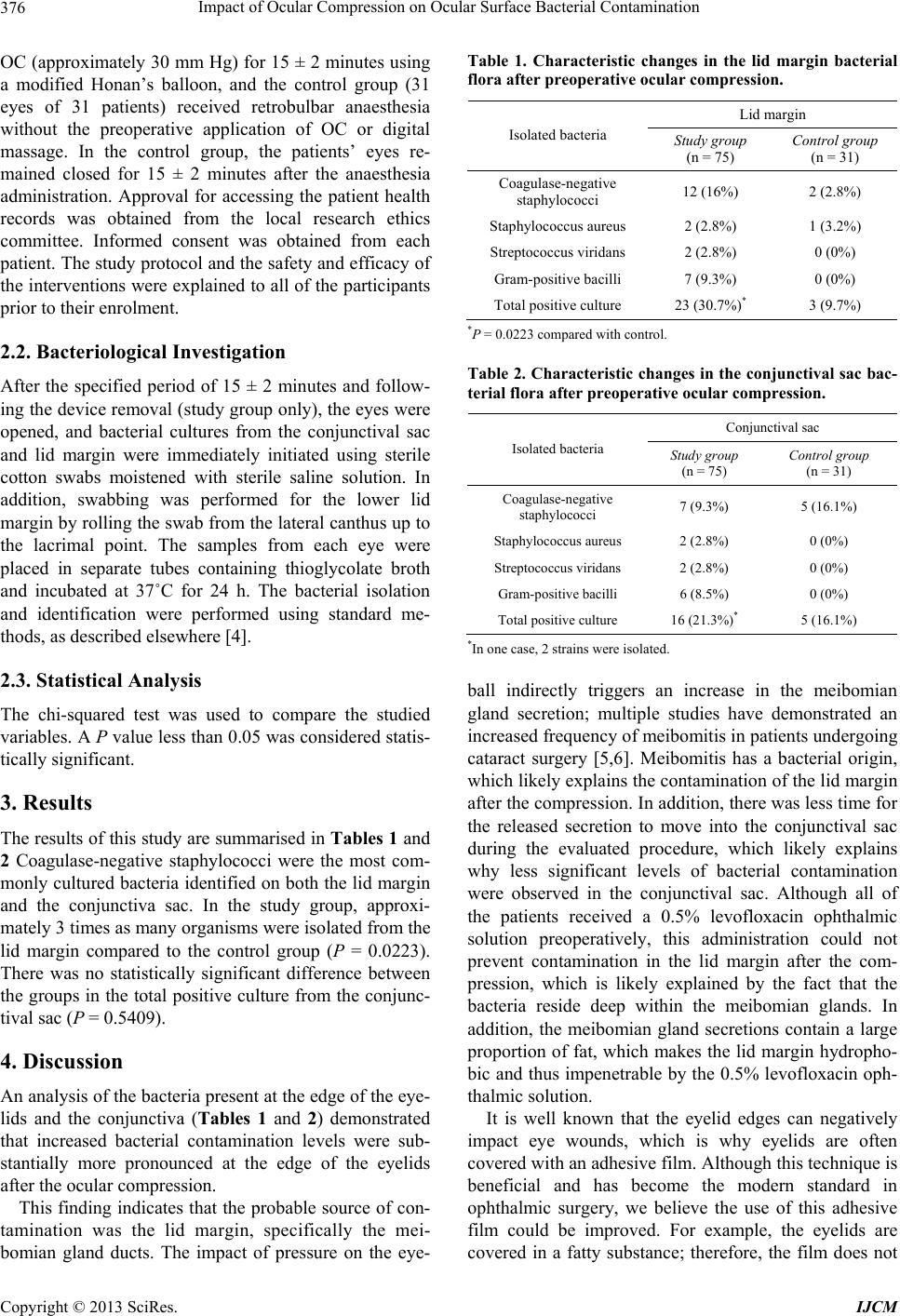

The results of this study are summarised in Tables 1 and

2 Coagulase-negative staphylococci were the most com-

monly cultured bacteria identified on both the lid margin

and the conjunctiva sac. In the study group, approxi-

mately 3 times as many organisms were isolated from the

lid margin compared to the control group (P = 0.0223).

There was no statistically significant difference between

the groups in the total positive culture from the conjunc-

tival sac (P = 0.5409).

4. Discussion

An analysis of the bacteria present at the edge of the eye-

lids and the conjunctiva (Tables 1 and 2) demonstrated

that increased bacterial contamination levels were sub-

stantially more pronounced at the edge of the eyelids

after the ocular compression.

This finding indicates that the probable source of con-

tamination was the lid margin, specifically the mei-

bomian gland ducts. The impact of pressure on the eye-

Table 1. Characteristic changes in the lid margin bacterial

flora after preoperative ocular compression.

Lid margin

Isolated bacteria Study group

(n = 75) Control group

(n = 31)

Coagulase-negative

staphylococci 12 (16%) 2 (2.8%)

Staphylococcus aureus 2 (2.8%) 1 (3.2%)

Streptococcus viridans 2 (2.8%) 0 (0%)

Gram-positive bacilli 7 (9.3%) 0 (0%)

Total positive culture 23 (30.7%)* 3 (9.7%)

*P = 0.0223 compared with control.

Table 2. Characteristic changes in the conjunctival sac bac-

terial flora after preoperative ocular compression.

Conjunctival sac

Isolated bacteria Stu dy group

(n = 75) Control group

(n = 31)

Coagulase-negative

staphylococci 7 (9.3%) 5 (16.1%)

Staphylococcus aureus 2 (2.8%) 0 (0%)

Streptococcus viridans 2 (2.8%) 0 (0%)

Gram-posi t iv e bacilli 6 (8.5%) 0 (0%)

Total positive culture 16 (21.3%)* 5 (16.1%)

*In one cas e, 2 strains were isolated.

ball indirectly triggers an increase in the meibomian

gland secretion; multiple studies have demonstrated an

increased frequency of meibomitis in patients undergoing

cataract surgery [5,6]. Meibomitis has a bacterial origin,

which likely exp lains the contamination o f the lid margin

after the compression. In addition, there was less time for

the released secretion to move into the conjunctival sac

during the evaluated procedure, which likely explains

why less significant levels of bacterial contamination

were observed in the conjunctival sac. Although all of

the patients received a 0.5% levofloxacin ophthalmic

solution preoperatively, this administration could not

prevent contamination in the lid margin after the com-

pression, which is likely explained by the fact that the

bacteria reside deep within the meibomian glands. In

addition, the meibomian gland secretions contain a large

proportion of fat, which makes the lid margin hydropho-

bic and thus impenetrable by the 0.5% levofloxacin oph-

thalmic solution.

It is well known that the eyelid edges can negatively

impact eye wounds, which is why eyelids are often

covered with an adhesive film. Although this technique is

beneficial and has become the modern standard in

ophthalmic surgery, we believe the use of this adhesive

film could be improved. For example, the eyelids are

covered in a fatty substance; therefore, the film does not

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. IJCM