Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.9, 549-556 Published Online September 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.49080 Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 549 An Implementation of the Japanese Autobiographical Method Seikatsu Tsuzurikata—“Life Writing”—In a US Elementary School Scott Richardson1, Haruka Konishi2 1Educational Foundations, Millersville University of Pennsylvania, Millersville, USA 2Education, University of Delaware, Newark, USA Email: scott.richardson@millersville.edu, harukak@udel.edu Received July 20th, 2013; revised August 20th, 2013; accepted August 27th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Scott Richardson, Haruka Konishi. This is an open access article distributed under the Crea- tive Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any me- dium, provided the o riginal work is properl y cited. This article explores the historical, philosophical, curricular, and practical methods of the Japanese auto- biographical method, “seikatusu tsuzurikata” and its implementation in a US elementary school. Seikatsu tsuzurikata is a progressive form of journaling that “provokes students to ‘objectively’ observe the reality surrounding them in terms of their own senses without any intervention of anyone else’s authority”, by writing essays “reflecting on their social situation” (Asanuma, 1986: pp. 153, 155). Part of life writing’s central philosophy is that students are not required to participate. For students who engaged in life writing, several benefits resulted, according to their teachers. However, we found that students had great difficulty articulating their social and emotional worlds because this kind of reflective work was uncomfortable and foreign to students who were subjected to teacher-driven, “content”, and “standards based” instruction. This article concludes by exploring the possibility of connecting life writing with social-emotional learn- ing (SEL). Keywords: Autobiographical Writing; Journaling; Language Arts; Democratic Pedagogy; Self-Actualization; Comparative Education What Is Seikatsu Tsuzurikata?—Historical and Philosophical Answers Tracing the historical roots of the tsuzurikata movement is a daunting task. Most primary sources are old Japanese texts that have been out of print for the better part of a century, or more. Our historical and philosophical understandings of the move- ment developed from several interviews of Japanese primary school teachers, conversations with curriculum theorist Shigeru Asanuma at Tokyo Gakugei University, and three English texts: 1) Asanuma’s (1986) The Autobiographical Method in Japa- nese Education, 2) Kitagawa & Kitagawa’s (1987) Making Connections with Writing: An Expressive Writing Model in Japanese Schools, and 3) Kitagawa & Kitagawa’s (2007) Core Values of Progressive Education: Seikatsu Tsuzurikata and Whole Language. During the Meiji Period (1868-1912), the primary goal of the emperor was to create a modern Japan. Meiji and his modern- izing elite believed modernization would benefit from a cen- tralized education system. In 1868, there were approximately 14,000 terakoya (primary schools). These schools operated autonomously from one another but provided an “institutional base upon which the modernizers could build” (Gutek, 2006). During the early years of the Meiji period, the government looked toward the educational models of the West for examples. In 1871, feudalism was abolished, and in 1872 the Meiji Fun- damental Code of Education—designed by Shimpei Eto, who was influenced by the educational systems of France, Germany, and the US—was implemented. This act established education as a national project and paved the road for future standardiza- tion. Japan’s primary schools became modeled after the American common school, and universities after German research institu- tions. In 1886, The School Ordinances, officially established a “uniform, standardized school system under the central author- ity of the national Ministry of Education and for four years of compulsory primary schooling” (Gutek, 2006). Japan was heavily influenced by the French system of education and es- tablished regional school inspection bureaus that were under the ministry’s direct authority. This helped lead the ministry’s in- volvement in national standardization and approval of text- books, subjects, and syllabi. Throughout the Meiji Period and into the Imperialist Period (1912-1945), Japan and its educa- tional system became increasingly nationalistic and militaris- tic. During these rapidly changing times in Japan’s history, cities were developed by middle and upper class families while rural farming communities and small mountain villages remained for the working poor. Many teachers in urban and rural contexts objected to the standardization of curricula because it narrowed the learning potential of their students, and they deemed the selected educational programming irrelevant. Urbanites sought for “more aesthetically refined culture because their desire was not fulfilled by the technical knowledge that was routinely  S. RICHARDSON, H. KONISHI Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 550 transmitted in school” (Asanuma, 1986) and teachers in rural schools were concerned with their students’ economic, social, and cultural oppression. In rural communities, many families were exploited by landowners in the tenant farm system and the curriculum did little to address this issue. Teachers in urban and rural communities began to address their dissatisfaction with the narrow and oppressive national curriculum by encouraging students to become self-actualized. Teachers believed that writing, specifically journaling, offered students the best op- portunity to do this. Thus, seikatsu tsuzurikata, an autobio- graphical method, was born somewhat independently in multi- ple geographic locations. Teachers encouraged students to na- turally and artistically write about their lives in journals so that they could “attain social consciousness of their community life” (Asanuma, 1986). Self-actualization was seikatsu tsuzurikata’s ultimate goal. According to Maslow, (1970) self-actualization is “the full use and exploitation of talents, capacities, potentiali- ties, etc.” (p. 150). He defines eight behaviors of self-actua- lization: 1) concentration, 2) growth choices, 3) self-awareness, 4) honesty, 5) judgment, 6) self-development, 7) peak experi- ences, and 8) lack of ego defenses (Maslow, 1971). Johnson and Johnson (2004), summarizes self-actualization as: the drive to actualize potential and take joy and a sense of fulfillment from being all that a person can be. Self-actu- alization is based on being aware of abilities and talents, applying them appropriately in a variety of situations, and celebrating their successful application. (p. 41) The primary philosophy of seikatsu tsuzurikata was that if students wrote in their journal s about their lived experiences, reflections on their social situations and deep analysis woul d result. Thus, self-actualized students would become a reality. Though seikatsu tsuzurikata was most popular pre-WWII, and shortly thereafter, many contemporary Japanese elementary school teachers still practice the method with their students. Interestingly, however, the term “seikatsu tsuzurikata” is con- sidered old-fashioned by many, and unknown by most teachers. During our most recent research trip to Tokyo, we asked teach- ers if they invited their students to journal at home or about their lives. They largely reported, “yes”. When we asked them if they followed seikatsu tsuzurikata guidelines, they became confused, because they were unfamiliar with the terminology. When we asked them why they encouraged their students to journal, they answered with responses like, “I don’t know… I just thought it is healthy for them to express their lives, so I asked them to do that.” Also it’s interesting that most Japanese teachers practice seikatsu tsuzurikata without understanding that it was ever a formal method, and that their colleagues —often right next door—also employed this kind of journaling with their students. Asanuma (1986) identifies four characteristics of seikatsu tsuzurikata: 1) The teacher emphasizes students to write descriptively. To write “events and things “as they are”… Students are advised to observe the world simply, using their own words, and to in- clude essential elements of their life in the community” (p. 156). 2) To pursue “the goals of cognitive development in social sciences”. That is, students’ writings should “be considered as an illustration of conceptualization of life” (p. 158). 3) It is “a means by which the individual can engage in crea- tive work whenever he/she wants”. This brings about the “abil- ity to reflect, which is an important educational goal of the tsuzurikata… developed by deeply understanding the objective reality on which the subjective reality is founded” (p. 159). 4) It provides students with a political orientation. Seikatsu tsuzurikata “has the advantage of brining students’ attention to social reality in the community and convincing them that the social reality they experience should be a source of the truth- fulness of the world” (p. 159). Teachers in Japan overwhelmingly agreed that journaling did indeed help students to become more self-actualized and more emotionally/socially centered. They also agreed that journaling helped to offset the pressures of standardization. Translation & Research Questions We recognized that there was great similarity between the old Japanese standards movement and that of the modern No Child Left Behind (NCLB) movement in the US. We wondered if life writing could supplement areas of inquiry, and provide students essential “non-academic” skills that are ignored by NCLB goals and standards. That is, could seikatsu tsuzurikata provide an opportunity to students that would allow them to think personally, socially, and creatively? We also wondered that if students engaged in seikatsu tsuzurikata, would they begin to understand their “schooling situation”. That is, would they more clearly understand that NCLB has limited their agency and self-determination as a student? And if so, would they begin to challenge their oppression? There has been much written about the consequences of NCLB, particularly for students in rural and urban school dis- tricts. For example, Bickel & Maynard (2004) notes that NCLB “oversimplifies the social context of schooling and underesti- mates the importance of socially ascribed traits” (p. 18). Dar- ling-Hammond (2007) adds that NCLB does not address “dreadful school conditions,” yields “consequences” that in- clude the undermining of “safety nets for struggling students”, impacts leaving school earlier (dropping out), and “strengthens the ‘school-to-prison pipeline’ (Wald & Losen, 2003)”. She posits, “Merely adopting tests and punishments will not create an accountability system that increases the likelihood of good practice and reduces the likelihood of harmful practices. In fact, as we have seen, adopting punitive sanctions without invest- ments increases the likelihood that the most vulnerable students will be more severely victimized by a system not organized to support their learning” (p. 258). In our view, NCLB is highly miseducative for multiple rea- sons, but predominantly because it expects the same course of experiences and results from every child regardless of their personalities, interests, and abilities. Or as William Pinar (2012) bluntly puts it, “Standardization makes everyone stupid” (p. 55). Students, particularly at the elementary level, largely accept schooling as it is because they have experienced it in no other way—they have become a deeply oppressed class of students. Under NCLB, schools have become increasingly task oriented, rather than inquiry oriented. Students have been expected to perform to isolated standards, not to think critically. To investigate the impact of life writing in a US context, we translated the method, developed several other more measure- able research questions, and employed it in an elementary school during the 2011-2012 school year.  S. RICHARDSON, H. KONISHI Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 551 Translation We translated “seikatsu tsuzurikata” as “life writing”. From the literature, and interviews with Japanese teachers, we deter- mined nine principles to properly employ “life writing” in school: 1) Students are invited to participate, but are never required to write; 2) Students should never write in school; 3) Students should write for themselves not for the teacher; 4) Students should write about whatever they choose; 5) Teachers should never provide writing prompts other than “write about your life”, or “be descriptive about a time and place…”; 6) Teachers should collect journals once a week and provide marginalia (ca lled “akapen” in Japanese) that elicits a tone as if the teacher is peeking over the shoulder of the student and lightly commenting; 7) Teachers’ marginalia should never correct students’ writ- ing; 8) Teachers’ marginalia should always be positive, and neu- tral—they should not influence how the student writes; 9) Students should write descriptively so that deep analysis will eventuall y a n d naturally occ u r . Research Questions Our research attempted to understand whether or not our im- plementation of life writing would lend itself to self-actualiza- tion. Primary Questions: Could life writing provide an effective response to NCLB? Could life writing provide an opportunity to students that would allow them to think personally, socially, and creatively? Would students more clearly understand that NCLB/narrow curricula/standards have limited their agency and self-determination as a student? Secondary Questions: What would life writing look like in a US elementary school? How do children narrate their realities? Are there differences according to grade level and gender? What are the limitations of life writing? Methods Participants This study took place at “Hyde Point Elementary”, a school located in a small Northeastern city in the United States. During the 2011-2012 school year, approximately 560 students were enrolled. The student body was identified as 91% White, 3% Latino, 3% Black, and 3% were Asian/other ethnicities. Teach- ers in two classrooms of 2nd graders, two classrooms of 3rd graders, and three classrooms of 5th graders agreed to partici- pate in life writing. Approximately one-quarter of all students in each classroom (42/170 students total) initially participated through December, but by May, on average, only three students per classroom were still writing in their journals. Teachers were interviewed so that we could understand their perceptions of life writing, and observations were conducted throughout the school year . Implementation of Life Writing At the start of the year, we trained the faculty of Hyde Point elementary school in life writing. Teachers became familiar with life writing objectives, our nine principles of the method, how to implement the practice of life writing, and good and bad examples of marginalia (Table 1). In the beginning of October, teachers distributed notebooks to their students and suggested that they “write about their lives” and to “be descriptive” when doing so. Teachers col- lected the notebooks on a weekly basis and provided marginalia to each student. The marginalia was always positive, reflective, and praised descriptions of the students’ world. Teachers never made corrections or talked about their lives, and at most simply recapped what the students had written. Researchers were available throughout the year to answer teachers’ questions and offer support. Data Analysis The journals were analyzed in December of 2011, and again in June of 2012. The principal, teachers, and school counselor were interviewed throughout the school year. Data analysis was conducted through an ethnographic-narrative and thematic analysis (Clandlin & Connelly, 2000; Butler-Kiser, 2010; Max- well & Miller, 2008; Merriam, 1997). “Thematic inquiry uses categorization as an approach for interpretation (Maxwell & Miller, 2008) that produces a series of themes that emerge in the process of the research that account for experiences across groups or situations…” Narrative inquiry uses a number of con- necting approaches to produce a contextualized and contiguous interpretation and storied account of the particular situation” (Butler-Kisber, 2010). Each journal entry was coded by topic (e.g., family, friends, emotions), genre (e.g., fantasy, realistic fiction, poetry, letter, non-fiction), style (e.g., titles, topic sen- tences) and depth and kind of analysis and voice (e.g., descrip- tive, analytical, writing for oneself or teacher). Depth and type of analysis and voice, was most important to determine because it could have provided evidence of whether or not life writing for self-actualization was accomplished. We determined that students were primarily descriptive by focusing on describing an event or a situation (e.g., “I went to my friend’s house…”). A few students became more analytical by making connections between described events and their subjective and objective experiences with these events. We determined students’ voice (who they were writing for) by taking into consideration for- mality, structure, word choice, and so on. The two authors independently coded journal entries and a Table 1. Examples of good and bad m arginalia from Jap a n e s e j o u rnals. Example of good marginalia Title: Grandpa My grandpa is a farmer and has been making rice for a lo ng time. He always says, “I only eat rice!” However, I have seen him enjoy eating bread. I wonde r if it’s just an act? Marginalia: Wow, you are watching your grandfather very closely! You are very perceptive. Example of bad marginalia Title: Shoki I am not very good at drawing. We had to draw in class today and it was really horrible. It was a pain. I didn’t like that at all. Marginalia: It’s important to be honest about how you feel. But I thought it shows your personality and was good.  S. RICHARDSON, H. KONISHI Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 552 consensus was reached for any disagreements. We challenged each other’s interpretations of the journals to ensure accuracy. Field notes, transcripts, and other records that resulted from interviews and observations were also shared, discussed, and coded thematically. Findings When crafting our research questions, we predicted that some would be easier to answer than others. Secondary re- search questions were more fully answered than primary re- search questions, and an unexpected finding (though it does not seems surprising now) is that Hyde Point’s existing writing curriculum impacted the depth at which students were/were not able to participate in the project of life writing. Hyde Point’s Existing Writing Curriculum Students at Hyde Point received writing instruction via an informal writing program titled, “Writers’ Workshop”. There are various formal writing programs called, “Writers’ Work- shop”, however, teachers at Hyde Point implemented none of these. Instead, they received professional development that informed them how to create mini-lessons, prompts, and ex- pectations largely based on specific writing skills. Writing was not taught in the same way between any two particular teachers, but similarities still existed. Teachers almost always asked stu- dents to write to predesigned teacher prompts, and in a formu- laic manner (e.g., topic sentence, body, conclusion, and so on). Much of the instruction also directly related to their classroom reading anthology series, and focused on skills that would be later assessed by the state’s standardized assessment. This kind of writing offered students little choice, options to be creative, opportunities to take risks, or chances to understand writing as a personal and expressive process crucial to understanding the relationship between their feelings and the world in which they live. Findings to Our Secondary Research Questions What would life writing look like in a US elementary school? How do children narrate their realities? Are there differences according to grade level and gender? What are the limitations of life writing? Teachers reported that life writing became very important to some students. They believed that students benefited from life writing because it gave them an “outlet” to form a relationship with their emotions and the teacher. Several of the teachers also reported that by reading the life writing journals, it gave them a more dynamic understanding of their students. Thus, teachers were able to better plan instruction that was more relevant and interesting. In this backdoor kind of way, life writing did chal- lenge the status quo of their standardized classrooms. Because life writing invited, rather than required participa- tion, only one-fourth of all students wrote in their journals. And on average, only three students from each class consistently wrote throughout the year. When we asked teachers why there was such little participation, they replied that they believed 1) students are generally disinterested in writing, 2) students do not wish to engage in perceived additional non-required “school work,” 3) students’ personal lives are busy and many do not have “quiet spaces” to write in the home, and 4) students do not know how to express themselves, or write in a creative way. Students who consistently wrote were excited to share their entries with their teachers. Often, they would write questions to teachers in their journals and outline spaces for teacher feed- back. US students were largely unable to write simply “for themselves”. It was clear that they were extrinsically motivated by teacher marginalia. Common topics that students wrote about included special events (e.g., Thanksgiving, friends’ birthday parties, slumber parties, trips with their families, and other social events). In terms of the style of writing, many students included titles and introductory sentences for their journal entries. Most students wrote just a few sentences per entry . Students who wrote more, generally composed their entries within the standard outline of the three to five paragraph essay. This reflects the kind of for- mulaic writing instruction they received in school. Students did not attempt to challenge typical writing conventions. While many students were descriptive, they were rarely analytical. Most students simply described events and wrote their general impressions of these events. There was little attempt to explain the reasoning behind their impressions. For example, Samantha suggested that she had a “fun” and “great” day. However, she provided no explanation or analysis of why it was so fun or great (Table 2). The same trend was found across many stu- dents, classrooms, and grade levels. Only three students consistently displayed some analysis in their journal entries. These students provided a detailed de- scription of their world and reflected on their subjective ex- periences of the event (Table 3). For example, Ezra carefully describes his experience being on a bus. Based on his descrip- tion, it is clear that he thinks everyone on the bus is being too noisy. However, he takes a step back an d c o n siders whether t h i s feeling is justified by thinking about what the bus driver might be feeling. Thus, he is reflecting on this event by considering multiple perspectives. In another example, Bryce discusses the number of dogs that his family has and considers why they went from having two dogs to one. Although, Bryce does not consider multiple perspectives he generates possible hypotheses that might explain why his family had to get rid of one dog. The quality of the journal entries that Erza and Bryce made are similar to that of typical Japanese students’ entries. Finally, Erika’s journal entries were at the level of a student who has significant practice with life writing. Erika does very little to warn the reader of the flow of her entries. In one entry, she goes from getting up in the morning, brushing her teeth to being on a bus, encountering a screaming girl, and talking about a boy that she may or may not like. It appears that she is not writing for a reader but is writing for herself. Despite how Erika is embed- ded in her own subjective world, she too considers multiple perspectives in her journal. She does not appreciate the scream- ing girl on the bus but she also recognizes it is not nice to say “shut up”. She is also aware of the screaming girl’s perspective and considers why she is screaming. Erika acknowledges that at times people do bad things for a reason, though she does not hypothesize these reasons. She reaches this depth of analysis by deeply grounding herself in a perspective that eventually leads to a significant level of objectivity and analysis. This trajectory is the typical process of students who practice life writing in Japan. It appears that although the majority of students either did not participate at all in life writing or did not continue to write, a small number of students displayed a deep level of analysis. This provides encouragement to continue the explora- tion and adaptation of this method.  S. RICHARDSON, H. KONISHI Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 553 Table 2. Excerpts of typical entries. Student A Title: Today I had a great tod ay. It was fun. Student B Title: My trip to granddads! I went to my grand fathers it was fun. He lives in South Caroli na! It was a long drive. I’ m glad I was going to see my grandparents. Student C Title: none Last week my dad took me to laser tag! I had a super surprise birthday! I had a fun we ek! Table 3. Excerpts of analytical entries. Ezra Title: None The bus is really noisy toda y. But me and my sister are j u st sitting here and every b o dy I see it being super loud. That I can’t even he ar. At least not everyone is being super loud. But I guess it ’ s okay if th e bus driver doesn’t care. Still tho ugh, everyon e is being too loud. That’s what I think. Bryce Title: My dogs I used to have 2 dogs, but now I only have 1 dog. This is why we had to get rid of my first dog. We got rid of Joe because he was always going to the bathroom in our house and he would jump on the chairs and would steal food out of my fami ly’s hands. My other dog is Maggie and she is very ca lm and very lovabl e. I can walk her every day because she doesn’t pull and doesn’t run away. Life is much easier with one dog. Erika Title: None Hello Journal, I woke up to my mom going to work. The lights were all on. I got out of bed and brushed my teeth and got d ressed. Well now I feel all clean. I went to the kitchen I f eel so hungr y. So I got a cookie dough pop tart. Yumm y in my tummy , so t here. A boy that I like as a friend and people say t h at I like him . But I don’t at al l . W ell there’s thi s really loud girl that sc r eams on the b u s and she sits in other p eople’s seats and everyone hates her. My ears are starting to hurt because of her. So one the bus, e veryone tells her to shut up. I agree but it was not nice to say shut up. I think there’s also a reason. People do bad things but there is also reason. School is easy but hard in social life. I think everyone can live without school but I can’t live without writing. There was one significant finding in how boys and girls wrote (dis)similarly. Students in second grade discussed “lov- ing” their family members, pets, and friends, at great lengths. Around the end of second grade, however, boys began to depart from this narrative of love. In third and fifth grades they in- creasingly discussed “masculine” topics such as sports, video games, and rough housing. Girls continued to discuss their social and emotional life throughout all grades, but with more sophistication, as they grew older. Girls often discussed the complicated nature of their feelings and relationships. It is im- portant to note that students rarely named events, objects, or feelings as “boy stuff” or “girl stuff”. However, it became evi- dent that students were heavily socialized “boys” and “girls”. In more advanced grade levels, students discussed single-sex par- ties, outings, and events organized by their parents, more than students in early grades. It was clear that parents began treating their children in more significantly gendered ways as they grew older. In our on-site observations, there was some evidence that upper elementary grade students were treated more stereotypi- cally “boy” and “girl” by their teachers as well. Boys and girls did not inherently understand components of their world in gendered ways, but adults socialized, or institutionalized, gen- der until they gain these masculine and feminine perspectives. The primary limitation to our study of life writing in the US was the lack of participation. Life writing was perceived as an “extra homework assignment”. Students were not required to participate, so most of them did not. The school assigned each student with a significant amount of homework (10 minutes per grade level)—e.g., second graders were assigned twenty min- utes of homework per night, while fifth graders were assigned fifty minutes of homework per night. Teachers understood that homework did not provide their students with any relevant edge, or learning (see: Kohn, 2006), however, continued to assign it out of institutional tradition. After trudging through assigned homework, students were unmotivated to do any additional perceived academic tasks that were not required by their teach- ers. Teachers informed us that most students dislike writing in general. They also hypothesized that since life writing does not offer prompts, students found it “difficult to know what to write about”. Students are almost always prompted, or told, how to complete/participate in all academic activities presented to them in school. When life writing provided an open and free space to creatively engage in their feelings, most students did not know how to even begin. Teachers identified that students have very shallow relationships with writing, partly because of the kind of writing instruction they received in school. From our observations, we agreed with the teachers and were re- minded of Calkins’ (1986) statement: We, in schools, set up roadblocks to stifle the natural and enduring reasons for writing, and then we complain that our students don’t want to write. After detouring around the authentic, human reasons for writing, we bury the students’ urge to write all the more with boxes and kits, and manuals full of synthetic writing-stimulants. At best, they produce artificial and short-lived sputters of enthusi- asm for writing, which then fade away, leaving passivity (p. 13). The guidance counselor recognized that students rarely shared their feelings in school primarily because typical school days are consumed with intense blocks of language arts and mathematics—tested subject areas. Students do not perceive school as a site where they “do” social-emotional work. One student reported to the guidance counselor, “There’s no space to be me at school”. Since students have not had ample practice in social-emotional skills, they have not acquired vocabulary that could accurately portray their perceptions and feelings. Thus, it was extremely difficult for students to participate in life writing. Findings to Our Primary Research Questions Could life writing provide an effective response to NCLB?  S. RICHARDSON, H. KONISHI Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 554 Could life writing provide an opportunity to students that would allow them to think personally, socially, and creatively? Would students more clearly understand that NCLB/narrow curricula/ standards have limited their agency and self-determination as a student? Many teachers asked us if they could provide students with the option to write in school so that participation might increase. In our first experimentation of life writing in a US school, we answered, “no”. We wanted to closely follow the method as practiced in Japan so that we could remark on its effectiveness. Given that only a few students consistently engaged in the project, understanding the capacity of life writing to “respond” to NCLB, is still largely unrealized. We hypothesize that rec- ognizing students’ “situations” requires simple participation at first, and then their writing will evolve to expose their “nama no koe” or “raw voice” (Kitagawa & Kitagawa, 2007), and eventually in-depth analysis of their expressions. Through teacher interviews and journal analysis, it was evident that a few consistent writers were able to do some of this. They were able to think more personally, socially, and creatively by the end of the year. However, it was too difficult to determine if students became any more self-actualized, or recognized their “schooling situation”. Discussion & Conclusion Teachers reported that there were several benefits to life writing for the students who had participated. Teachers also reported that they professionally benefited from implementing life writing in their classrooms. They better understood stu- dents’ needs which led them to adapt instruction accordingly. Also, teachers built positive relationships with these students. Teachers identified that the primary obstacle to life writing was students’ lack of motivation for writing and the manner in which schooling had socialized students to think only within assignments—seeking only external rewards like good grades, high scores on test, and so on. We wish to increase participation in future trials. To do so, we must explore why there was much more participation in seikatsu tsuzurikata/life writing in Japanese schools than at this US elementary school. We generated four hypotheses. The first comes from the notion that the teaching profession is highly respected and desirable in Japan (Hello Work Website, 2013). There is an expectation that whatever the teacher suggests must be good for students in some way. Therefore, although seikatsu tsuzurikata is not mandatory, Japanese students may feel more inclined to give it a try. In fact, most Japanese teachers we in- terviewed reported that by the end of the school year all of their students consistently wrote in their journals. Second, Japanese students often perceive seikatsu tsuzurikata as an opportunity to share different parts of their lives to their teachers and develop a bond with them. Japanese elementary school classrooms range from 30 to 40 students and there is little time for one to one interaction between teachers and students (Laslett, 1972). Therefore, students often value the chance to share their thoughts and experiences inside and outside of school. Al- though, some American students saw life writing as a means to communicate with their teacher (e.g., they wrote “Dear Mrs. Thomas” in their journal), the majority of students did not nec- essarily think about life writing as a way to share their personal life to their teacher but saw it simply as homework. Third, Japanese students have a strong and loyal tradition to dutifully complete homework. Many students spend hours tediously completing homework assignments and attending “after school schools” or “cram schools” known as “juku” into most even- ings. Homework is simply a way of life. American students, for the most part, have a strong aversion toward homework. For these reasons, American students in this elementary school saw less value in participating in life writing than Japanese students. Our research suggests that while seikatsu tsuzurikata has been highly successful in Japan, life writing’s fullest potential in the US is yet to be realized. We do believe, however, that a few students at our study site have begun to awaken their social consciousness to a small extent by writing essays on their social situation. Teachers at our US site wanted to continue to offer “life writing” into the next academic year because they perceived that it provided students with opportunities to “dabble in crea- tive fiction”, “to tell bits and pieces of their daily lives, their thoughts and dreams” (Dougherty, 1999: pp. 40-41), “to begin to face their external and internal struggles head on in a way that is less stressful” (Heydt, 2004: p. 19), “to take care of one-self by encouraging personal and cognitive growth”, to “promote a greater sense of self-knowledge, one that extends beyond formal educational structures”, and to “serve a public function in the classroom environment… with a voice toward classroom discussion” (Slifkin, 2001: p. 5). Taking this into consideration, but recognizing that journaling at home is proved to be difficult, we decided that future trials should allow the writing of journals during the school day. Also, we feel that students should be “primed” to emotionally connect with schooling, academics, and their thoughts prior to, and during, the implementation of life writing. This is perhaps, the most significant reason why seikatsu tsuzurikata was more readily attempted by students in Japan than those in the US. In Japan, students (particularly in early grades) are familiar with a school culture that “primes” or intentionally guides them to become “self-reliant and interpersonally skilled, spontaneous, joyful, and emotionally responsive” (Tobin, Hsueh, & Karasawa, 2009: p. 137) while students in the US are heavily “managed” by classroom teachers to mindlessly respond and perform “school” without any need to exercise much self-control or make emo- tional connections with their academic experiences. Japanese educators often employ pedagogical methods that demonstrate the making, and understanding, of feelings. For example, teachers often perform okote iru (anger), ureshii (happiness/ excitement/satisfaction), and sabishii (sadness/loneliness) for their students. Tobin, Hsueh, & Karasawa (2009) note that sabishii …is given the greatest curricular emphasis in Japan… emphasizing feelings of sadness and loneliness with young children is a pedagogical tool known to Japanese mothers and teachers alike; it is a deep cultural script, tied to a particular cultural sensibility—a kind of melancholic longing (wabi-sabi) highly valued in Japanese aesthetics and social life (Hayashi, Karasawa, & Tobin, 2009). Not purely or even mostly negative, sabishii, like shame and guilt, is a pro-social emotion that binds people together in society (p. 140). There are few emotional threads consistently woven and ex- plored throughout American society and education. While American education has largely ignored the works of prominent US educational philosophers, such as Nell Noddings, Maxine  S. RICHARDSON, H. KONISHI Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 555 Greene, and Megan Boler—who write on the power of feel- ings—the Japanese education system is deeply impacted by the works of Japanese educational philosophers, like Tsunesaburo Makuguchi—who claims happiness a primary aim of education. Noddings (2003) notes that Makuguchi’s “focus may seem a bit odd to Western readers” (p. 3). To further emphasize this point, Merry White (1987) provides an example of a typical 5th grade Japanese introductory math lesson: We [Americans] might easily expect an environment suf- fused with rote learning and memorization, a structured and disciplined setting with an authoritarian teacher in control. This is far from the reality of most classrooms… the teacher presented the children with a general statement about the concept of cubing. But before any formulas or drawings were displayed, the teacher asked the class to take out their math diaries and spend a few minutes writ- ing down their feelings and sense of anticipation about the new idea. Now, it is hard to imagine an American teacher beginning a lesson with an exhortation to examine one’s emotional predispositions about cubing (pp. 113-114). Japanese pedagogical practice such as this 1) reminds stu- dents to listen to and express their feelings in relation to ideas and the world, 2) encourages students to “see” their teacher as a person of emotional insight and mentorship, and 3) establishes a school culture that tells students that they are cared for. American schools, have been slow to recognize that “taking care” of the whole child (not just academically) is of great worth even though what “we remember and tell about our own schooling are not so much about what we learned, but how we learned and with whom… about teachers we loved, teachers we hated and those we feared… There were good days and others full of tears and broken hearts, and many, many days of bore- dom, monotony, and endless repetition (Rousmaniere et al., 1997, p. 4). We strongly recommend that if life writing is offered again in a US school, that the method be coupled with educators who encourage students to be in touch with their subjective world and emotions, as grounding oneself in their subjective experi- ence is a crucial component of life writing. Because American culture and schooling does not do this naturally, perhaps adop- tion of a social and emotional learning (SEL) program, might be a good first step. Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) defines SEL as, “a process for helping children and even adults develop the fundamental skills for life effectiveness. SEL teaches the skills we all need to han- dle ourselves, our relationships, and our work, effectively and ethically” (http://casel.org/why-it-matters/what-is-sel/). CASEL identifies five SEL core competencies: 1) self management, 2) self-awareness, 3) responsible decision-making, 4) relationship skills, and 5) social awareness. Concentration on SEL will em- power students with the language and means to think about their lived experiences and emotions. This would be an ap- proximation toward self-actualization because it provides stu- dents some autonomy, and honors their perspectives. McCombs (2004) states, “Real-life learning is often playful, recursive and nonlinear, engaging, self-directed, and meaningful from the learner’s perspective… Research shows that self-motivated learning is possible only in contexts that provide for choice and control. When students have choice and are allowed to control major aspects of their learning (such as what topics to pursue, how and when to study, and the outcomes they want to achieve), they are more likely to achieve self-regulation of thinking and learning processes” (p. 25). We hope that in future research, schools (guidance counsel- ors, teachers, and so on) will employ both the teaching of SEL and life writing in classrooms. We understand this to be impor- tant because, as stated by Zins, Bloodworth, Weissberg, & Walberg (2004), “there is a growing body of scientifically based research supporting the strong impact that enhanced so- cial emotional behaviors can have on success in school and ultimately in life” (p. 19). We hypothesize that with life writing and SEL, American students might be able to develop self- actualization like that of their Japanese peers. REFERENCES Asanuma, S. (1986). The autobiographical method in Japanese educa- tion: The writing project and its application to social studies. In W. Pinar (Ed.), Contemporary curriculum discourses (pp. 151-168). New York, NY: Peter Lang. Bickel, R., & Maynard, A. S. (2004). Group and interaction effects with “no child left behind”: Gender and reading in a poor, Appalachian district. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 12, 1-18. CASEL (n.d.). What is sel? http://casel.org/why-it-matters/what-is-sel Calkins, L. (1986). The art of teaching writing. Portsmouth, NH: Hei- nemann Educatio n a l B oo k s , Inc. Darling-Hammond, L. (2007). Race, inequality and educational ac- countability: The irony of “no child” left behind. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 10, 245-260. doi:10.1080/13613320701503207 Dougherty, S. (1999). Autobiography: Telling our stories. Montessori LIFE, 11, 40-41. Gutek, G. (2006). American education in a global society: Interna- tional and comparative perspectives (2nd ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Pres s. Hayashi, A., Karasawa, M., & Tobin, J. (2009). The Japanese pre- school’s pedagogy of feelings: Cultural strategies for supporting young children’s emotional development. Ethos, 37, 32-49. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1352.2009.01030.x Heydt, S. (2004). Dear diary: Don’t be alarmed. I’m a boy. Gifted Child Today, 27, 6-25. Johnson, D., & Johnson, R. (2004). The three Cs of promoting social and emotional learning in building academic success on social and emotional learning. In J. Zins, R. Weissberg, M. Wang, & H. Wal- berg (Eds.), Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say (pp. 40-58)? New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Kitagawa, M., & Kitagawa, C. (1987). Making connections with writing: An expressive writing model in Japanese schools. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann Educational B o ok s, Inc. Kitagawa, M., & Kitagawa, C. (2007). Core values of progressive edu- cation: Seikatsu tsuzurikata and whole language. International Jour- nal of Progressive Edu cation, 3, 52-67. Kohn, A. (2006). The homework myth: Why our kids get too much of a bad thing. Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo Press. Maslow (1970) Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper & Row. Maslow (1971) The reaches of human nature. New York, NY: Viking Press. McCombs, B. (2004). The learner-centered psychological principles: A framework for balancing academic achievement and social-emo- tional learning outcomes. In J. Zins, R. Weissberg, M. Wang, & H. Walberg (Eds.), Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say (pp. 23-39)? New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Noddings, N. (2003). Happiness and education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511499920 Pinar, W. (2012). What is curriculum theory (2nd ed.)? New York, NY: Routledge.  S. RICHARDSON, H. KONISHI Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 556 Hello Work Website ( 2 0 13 ). Popular professio ns i n J a pa n . http://www.13hw.com/jobapps/ranking.html Rousmaniere, K., Dehli, K. , & de Coninkl-Smith, N. (1997). Discipline, moral regulation and schooling. New York, NY: Garland Publishers. Slifkin, J. (2001). Writing the care of the self: Variances in higher order thinking and narrative topics in high school students' reflective jour- nals. English Le a dership Quarterly, 24, 5-11. Tobin, J., Hsueh, Y., & Karasawa, M. (2009). Preschool in three cul- tures revisited. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226805054.001.0001 Wald, M., & Losen, D. (2003). Deconstructing the school to prison pipeline. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. White, M. (1987). The Japanese educational challenge: A commitment to children. New York, NY: The Free Press. Zins, J., Bloodworth, M., Weissberg, R., & Walberg, H. (2004). The scientific base linking social and emotional learning to school suc- cess. In J. Zins, R. Weissberg, M. Wang, & H. Walberg (Eds.), Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say (pp. 3-22)? New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

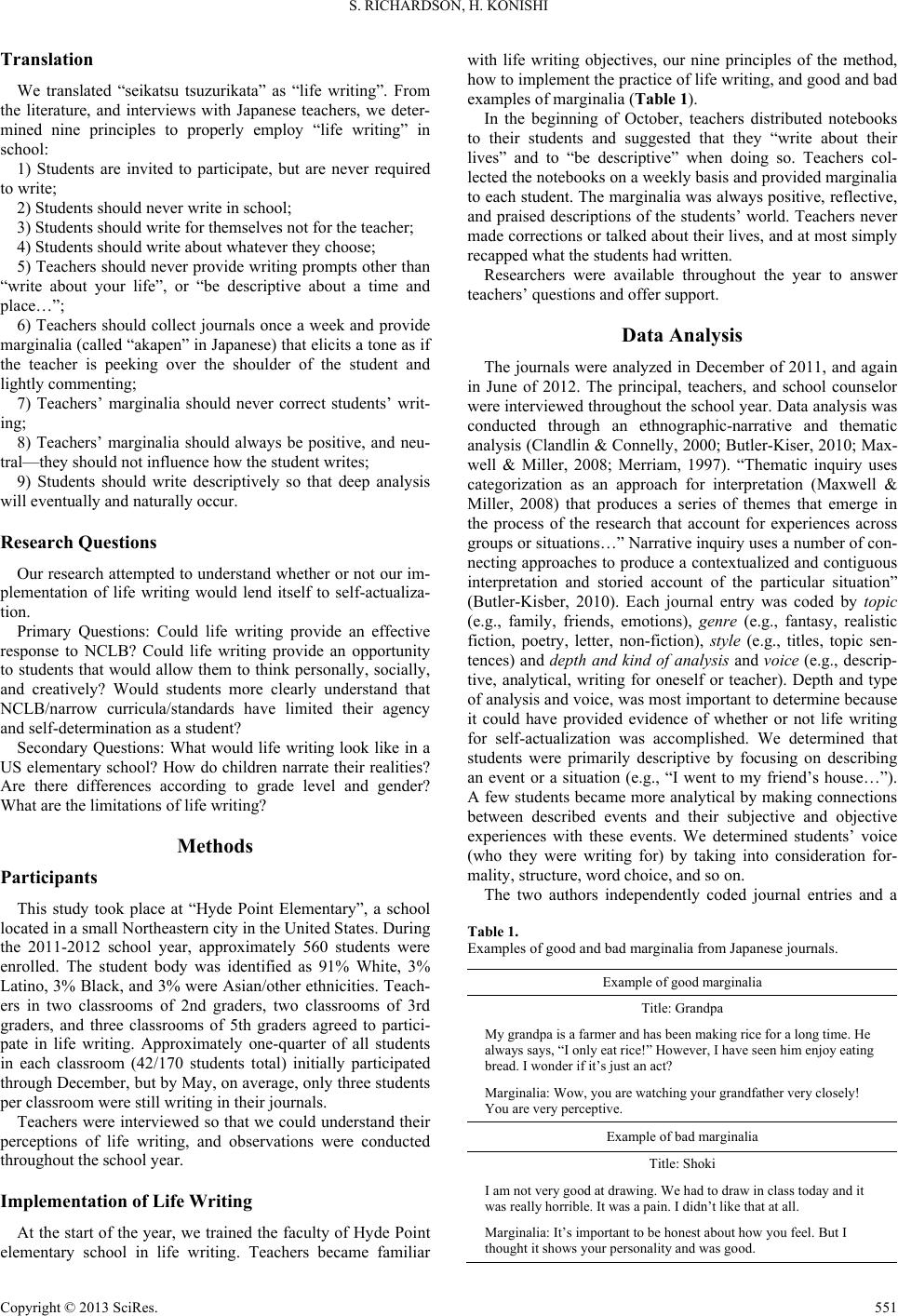

|