Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.9, 540-548 Published Online September 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.49079 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 540 Introducing Online Learning in Higher Education: An Evaluation David Fincham St Mary’s University College, London, UK Email: david.fincham@smuc.ac.uk Received December 8th, 2011; revised December 8th, 2012; accepted January 1st, 2013 Copyright © 2013 David Fincham. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Traditionally, in educational contexts, learning and teaching has been seen as a direct interpersonal classroom activity. However, with the development of information technology in general and Internet and online technologies in particular, there has been an increasing emphasis on the development of distance learning methods, providing opportunities to extend boundaries of space and time. In this paper, the author sets out to present the findings of a case-study enquiry into student perceptions of the introduction of an e-learning component as part of their experience of an M.A. programme in Catholic School Leadership at St Mary’s University College, Twickenham. By engaging with online learning, students were able to participate in a “virtual classroom” through which they were able to share discussions initi- ated by questions that were provided online. The introduction of online learning, therefore, represents a significant development that had a potential impact on pedagogy and assessment. This paper concludes that, whilst there were some anxieties about the introduction of the facility, students acknowledged that, generally, online activities enhanced the quality of their education. Keywords: Higher Education; Distance Learning; Information and Communication Technology; Blended Learning; Pedagogy; Assessment Introduction Learning and teaching in Higher Education—as in all sectors of education—has traditionally been characterised as face-to- face and classroom based. Thus, teachers stand at the front of the classroom and teach learners. To this extent, the traditional model of education has been defined as “closed” (Jarvis et al., 2003: p. 117). Indeed, historically, this has represented the pre- dominant educational approach1. Whilst Illich (1971), making a case for the de-schooling of education, advocated more radical and “open” models of learning and teaching, proposing, for example, the use of technology to support “learning webs”, his impact was, arguably, more theoretical than practical. With the development of information and communication technology, the Internet and online working, however, interest in “open” and distance strategies has become more prevalent. This has had a significant and practicable effect on learning and teaching. Such modes of interaction, exploiting computer tech- nologies, have broadened both temporal and spatial boundaries and increased the focus on learning. This has implications for the development and extension of courses beyond the confines of the classroom. Simultaneously, these developments have been associated with a trend towards globalisation and post- modernism2. It is argued, though, that distance learning is not so new. Black and Holford (Jarvis, 2002: p. 189), for example, contend that the exchange of letters between universities and other edu- cational institutions in the Middle Ages formed the basis of what we would now interpret as distance learning. In this light, moreover, correspondence courses, which emerged in the nine- teenth century and were extended in the twentieth century, might also be considered as early examples of distance learning. Significantly, though, with the establishment of the Open Uni- versity in the United Kingdom in 1969, the concept of distance learning has gained wider prominence and exposure. The emergence of global forms of communication, such as the “world wide web”3, however, has served as a catalyst for the expansion of distance learning and brought about our under- standing of the term as used today. With advances in technol- ogy, new patterns of pedagogy and assessment have arisen, which have, progressively, become a more pervasive element in education. Consequently, traditional models have been chal- lenged. Barnett and Hallam (1999: p. 137), for example, ask, “What forms of learning and teaching are appropriate to ‘a learn- ing society’ and ‘globalization’?” Bridges (2000: p. 49), quoting Burbules and Callister (1999: p. 10), points out that Increasingly, the Internet is a working space within which knowledge can be co-constructed, negotiated and revised over time; where dispa rate students from diverse locations 1Watkins (2005: p. 1) maintains that, since the earliest times, in the con- struction of classroom pedagogy, “learning” has been considered equivalent to “being taught”. 2Green (1997: p. 170), for example, draws attention to the impact of de- velopments in computer technology upon education in his discussion of the effects of globalizatio n. 3The invention of the “world-wide web” in 1990 is credited to Tim Berners- Lee, an English computer scientist.  D. FINCHAM Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 541 and backgrounds, even internationally, can engage one another in learning activities… Nowadays, it would seem to be axiomatic that all students should keep up with new forms of information and communi- cation technologies. By providing modes of distance learning, using online access, they are offered opportunities to do this. The combination of conventional and online approaches has led to the emergence and increasing use of “blended learning” in pedagogical methodology, whereby face-to-face learning is combined with the application of technology through appli- ances such as computers and video-conferencing. Blended learning has the capacity to expose students, at any level of study, to experience a variety of teaching and learning opportunities. This means that traditional face-to-face class- room teaching through lectures or seminars, which are sup- ported with recommended course reading, can be comple- mented with facilities that exploit information and communica- tion technologies. Blended learning, therefore, implies the combining of resources, techniques and methods with a view to using them interactively in a learning environment. Indeed, the development of blended learning strategies has offered in- creasing opportunities for independent, personalised and flexi- ble learning. As a result, students are encouraged to become independent learners and to reduce their dependence on teacher- centred instruction. Middlewood (2001), moreover, argues that universities and other institutions of Higher Education need to explore new ways of reaching students so that they can extend access and establish new relationships. This may be part ly due to financ ial and economic considerations and partly due to the need for other forms of external accountability. Nevertheless, one con- sequence of this is that learning materials in institutions of Higher Education are now not only available in the printed form but also online. Increasingly, therefore, there are opportu- nities for students to communicate and interact in discussion groups in “virtual classrooms”. As Exley and Dennick (2005: p. 124) assert, As greater numbers of mature learners and part-time stu- dents enter H.E., such flexibility in course design and methods of facilitating discussion and tutor support will become increasingly necessary. It has also to be acknowledged, however, that there is scope for the development of online distance learning throuth progno- stications as to its future direction is as yet tentative. However, in terms of its potential to extend the reach of higher education, it is interesting to note, as Williams (2005: p. 330) points out that, as a pioneer of distance learning in higher education, the Open University: …is Britain’s largest university by far in terms of student numbers, yet its campus at Milton Keynes is physically the smallest and is rarely visited by students. It is evident that the increasing use of information and com- munication technologies and virtual learning environments add new opportunities for student learning4. Learning becomes more democratic in the sense that students who might otherwise be diffident in traditional classroom settings are able to offer their contributions to discussions. Tutors, too, can act as online facilitators, focussing discussions and adding observations in the light of student contributions. Significantly, by integrating asynchronous computer discus- sions into course design, it is possible to accord greater author- ity to the contribution of students. Students are able to take greater responsibility for their learning. Consequently, greater emphasis can be attached to learning compared with teaching. Thus, as Lea (2004) argues, the use of virtual learning envi- ronments potentially opens up new perspectives “by offering the students the opportunity for electronic debate and discus- sion and, additionally, providing a permanent record of these which can be accessed repeatedly by students throughout their studies.” (Lea, 2004: p. 759) The Study The introduction of new technology can be received with a diversity of responses, from enthusiasm to hostility. This is not surprising, perhaps, as innovation can be perceived as both a challenge and a threat. Stenhouse (1975: p. 170), for example, says: Genuine innovation begets incompetence. It de-skills tea- cher and pupil alike, suppressing acquired competencies and demanding the development of new ones. It was anticipated that the introduction of online learning as a key element of the MA Catholic School Leadership programme at St Mary’s University College might potentially create anxi- ety and apprehension for students. To this extent, it was con- sidered to be no different from any other innovation. In order to assess the reaction of students towards this initiative and how far they adapted to it, though, it was decided to investigate their attitudes towards its introduction. It was hoped, too, that by providing a basis for discussion, there would be an opportunity to involve students, enabling them to express their views and, as a means of evaluation, helping course leaders to address significant issues. The purpose of the exercise was not to reinforce predeter- mined notions but to encourage continued and considered ap- preciation of the role of online technology in Higher Education and to provide a basis for discussion and progression. Basically, the aim was to “test the water”. It was intended, therefore, to conduct a small-scale survey with a view to assessing the gen- eral climate of opinion. In order to do this, as an instrument of evaluation, a questionnaire would be distributed amongst stu- dents who were engaged with online learning in the MA Catho- lic School Leadership programme at St Mary’s University Col- lege. Methodology The purpose of the enquiry, then, was to investigate student perspectives of their experience of using online learning. Spe- cifically, it was intended to evaluate their perceptions of online learning as an element of their learning on the M.A. programme in Catholic School Leadership at St Mary’s University College. Consequently, in eliciting perceptions of participants towards the use of online learning, the enquiry represented a case study based on a questionnaire survey. Yin (2002) suggests that a case study should be defined as a research strategy, an empirical enquiry that investigates a phe- 4There are impl ications, too, f or Higher Education i n preparing student s for an increasingly interrelated global environment. Bennell and Pearce (2003), for example, explore the degree to which Higher Education provision in the United Kingdom and Australia has become i n t ernationalized.  D. FINCHAM Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 542 nomenon within its real life context. There are a number of advantages in adopting a case study approach. A case study, for example, can include quantitative and qualitative paradigms, rely on multiple sources of evidence and benefit from the prior development of theoretical propositions. A case study also provides a systematic way of looking at events, collecting data, analysing information and reporting results. It was felt that a case study would gain a clearer under- standing of events and what was significant for future research. One advantage of using a case study is that a number of differ- ent research tools are available. In this instance, it was decided to conduct a case study on the basis of the distribution of ques- tionnaires among students currently pursuing the course to elicit information as a source of evidence. Since the project was de- signed as a small-scale enquiry, it was felt that the distribution of a questionnaire would provide appropriate data for its pur- poses within a relatively short amount of time. The Context of the Study Starting from September 2007, students pursuing the St Mary’s University College M.A. Catholic School Leadership programme were to be assessed according to the regularity and frequency of their contributions, knowledge of material and responses to online activities via an e-learning facility. With access to the virtual learning environment, students would not only complete learning tasks, but they would also be able to exchange ideas through online discussion groups, involving collaborative learning and the use of interactive, case study and problem solving techniques. As the M.A. Catholic School Leadership programme attracts students from all over the United Kingdom, including Northern Ireland and Jersey, as well as from overseas, online learning provides opportunities for the extension of both independent and small group enquiry5. It was proposed, in addition, that up to 20% of the students’ marks for the programme would be directly allocated in respect of their online contributions. The introduction of online learning, therefore, represented a signifi- cant development in the configuration of the programme with potential impact on both pedagogy and assessment. The Survey Twenty-eight students from five different centres located in South-East and North-West England took part in the survey. The basis of selection was that they were all students who started the first module (i.e. Catholic Education) of the M.A. programme in Catholic School Leadership in October, 2007. This enabled the researcher achieve consistency by identifying respondents who were all engaged in the same part of the pro- gramme and had access to the same facilities at the same time. The number of students in each centre can be shown as fol- lows: All Saints’ Centre6 3 St Bernadette’s Centre 9 St Cecilia’s Centre 3 St Dunstan’s Centre 3 The Holy Family Centre 10 Total 28 Significantly, as all the students were all registered to parti- cipate in online learning and could share “discussions”, they all belonged to one “virtual classroom”. The point of the investiga- tion was to elicit the views of the twenty-eight students who had participated in Module One of the programme during 2007-2008. The intention of the investigation, then, was to elicit the views of students taking part in the M.A. programme in Catho- lic School Leadership towards the use of online learning. The next stage of the process was to design an appropriate instru- ment of measurement in the form of a questionnaire. Questionnaire The use of a questionnaire as an instrument of research was considered to be the most appropriate method of gathering data for this particular piece of enquiry as it was relatively easy to design and seemed to be the most efficient means of eliciting the required information within the time available. Advice and guidance was sought from colleagues who had had experience in working with questionnaires. For example, approaches towards designing a questionnaire were discussed with someone who had carried out a similar investigation into online use in the library, which led to a PGCHE qualification two years previously. Rather than “reinventing the wheel”, it was felt that it would be advantageous to look at an earlier questionnaire, which had been designed for a comparable en- quiry into the use of online resources. As a result, it was possi- ble to produce a first draft of the questionnaire. In addition, in order to check the suitability of the questions and the design of the questionnaire itself, a member of staff with experience in research methods was consulted. As a result, helpful feedback was gained, which led to amendments and modifications to the first draft. Careful consideration of the presentation of the questionnaire was taken into account. It was felt, for example, that, if the questionnaire were shorter, it would attract a higher response rate than a long complex one. Throughout, it was the concern of the researcher to indicate clearly where respondents needed to tick boxes or select an answer from a number of options. Above all, in order to encourage a high response rate, the intention was to keep the questionnaire relatively simple and to ensure that it was not too long. Attention was paid to layout as this could encourage the re- spondent to view the questionnaire in a positive manner. In- structions included an explanation of the purpose of the ques- tionnaire, assurance of confidentiality, how to complete the questions and where to return the completed questionnaire. By dividing the questionnaire into sections, it was hoped that the respondents would be more attracted to answering the questions. By using a variety of question formats, it was also hoped that it would keep it more interesting and avoid the danger of repeti- tiveness. The questionnaire began with a short introduction to explain to respondents how the questionnaire was structured. The first priority was to identify appropriate questions and to think about how to select appropriate variables. The questionnaire was divided into six sections. 5It should be added that, in 2008, one of the first Full Distance Learning (FDL) students, a teacher working in a school in Malta, joined the M.A. Catholic School Leadership programme. She graduated in 2012 with dis- tinction. Her work and the learning outcomes of other FDL students illus- trated that blended learning opportunities can be offered to students without any dilution in academic quality. 6For ethical reasons, and to preserve anonymity, the names of the centres have been changed.  D. FINCHAM Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 543 The first section of the questionnaire consisted of factual questions that were relatively easy to answer. More difficult and thought-provoking questions were included later and an open-ended question was left until the end. The first section was concerned with eliciting factual data, such as the gender and age of the respondents. This data would potentially provide a basis for comparison of attitudes across the sample. The sec- ond section of the questionnaire was concerned with eliciting attitudes of respondents towards online learning in general. These were set out in a Likert-style five-point scale, designed to enable respondents to specify their level of agreement or disa- greement to a statement. The third section applied a tick-box approach to establish the regularity of use of online learning by respondents. In the fourth section the intention was to consider in more detail the extent to which Course Tools were utililised. There were a number of facilities that are available through the online learning portal, including, areas for Discussion, a Resouces Zone and Web Links and it was intended to discover to what extent these had been used. The Discussion forum learning activities were structured primarily to promote conversations that would facilitate the exchange of ideas between students—not between students and tutors! With hundreds of postings being made, it would not be feasible for tutors to respond to every posting! Tutors might spend about an hour a week skimming postings and would only contribute if it would help to move a discussion forward. A Resources Zone exploited the freedom within copyright regulations to make a wide range of literature sources available to students. Through this facility, copyright-free material can be made available to students through key chapters and papers scanned from relevant books, ensuring access to a breadth of reading during assignment planning The Web Links facility enabled students to gain direct access to relevant websites, including the National College of School Leadership, Catholic Education Service and the Vatican web- site from which a vast range of publications can be downloaded. This provided another resource for students to read around the subject and make further enquiries to benefit their studies. An opportunity was provided in the fifth section for res- pondents to indicate what help they required in using online learning. Finally, in the sixth section, an open-ended question was provided, which invited respondents to make any further comments about their attitudes and use of online learning as part of their studies. Ethical Considerations To be ethical, a research project needs to be designed with the intention of producing reliable outcomes. A researcher needs to anticipate every possible repercussion of procedures and conduct relating to the enquiry. Ethical problems can arise from all methodologies and appear at any stage. Consequently, as all participants were known personally, it was important that, as well as wishing to avoid partiality, participants would feel confident that they could give their responses honestly and without fear of publication or prejudice. By following these guidelines, each participant was assured that anonymity would be preserved with regard to evidence relating to the project. In order to protect their identity, then, all participants were assured that anonymity would be preserved and that all information gathered would be treated with the strictest confidentiality. Ethical considerations were taken into account with reference to the College’s ethical standards for research involving human participants. Initial permission was sought through the Ethics Committee of St Mary’s University College by means of com- pleting an Ethics Self-Assessment Form. As questionnaires represent a potential intrusion into other people’s lives, sensitivity towards the possible invasion of pri- vacy were taken into account. Therefore, a covering letter was attached to the questionnaire, indicating that participation in the survey was entirely voluntary. Students were assured that all information provided through the survey would be considered both anonymous and confidential. According to Sapsford and Abbott (1996, quoted in Briggs and Coleman, 2007): … confidentiality is a promise that you will not be identi- fied or presented in an identifiable form, while anonymity is a promise that even the researcher will not be able to tell which responses came from which respondent. (Briggs & Coleman 2007, p. 166) It was important for respondents to feel confident that they could give their responses honestly and without fear of identi- fication or prejudice so all participants were assured beforehand that information that could identify them as individuals would not be disclosed to anyone else7. Consequently, the covering letter also stated that information that could identify students as individuals would not be disclosed to anyone else and that sta- tistical information held on computer would be subject to the provisions of the Data Protection Act. Procedures One consideration concerned how the questionnaire was to be distributed. One approach, for example, would have been to send them out online. The advantage of this was that it could be guaranteed that it would be possible to contact all students by email. A potential drawback, however, was that those who were less confident about using a computer might be disadvantaged. It was considered, initially, that questionnaires would be dis- tributed personally at the end of a class with the request that completed questionnaires would be returned in the next session. However, in order to ensure completion and return of the ques- tionnaires, they were, in practice, distributed at the beginning of the class, while people were arriving and settling in. This prov- ed to be less disruptive to the lesson and also ensured that com- pleted questionnaires were handed in. Whilst allowance had to be made for possible absentees, it was felt that a face-to-face distribution of questionnaires would provide an opportunity to explain the purpose of the study orally and would enable the researcher to be immediately avai- lable to answer queries. If students were absent, they could be followed up at a later class. By numbering questionnaires, in addition, a check could be made later with regard to the number of questionnaires had been returned. As a result, the questionnaires were distributed to students of each of the groups at the beginning of their last lesson of mod- ule one during January and February 2008. 7In following ethical guidelines, participants were assured that all informa- tion gathered would be treated with the strictest confidentiality and they were assured that the i r anonymity would be preserved.  D. FINCHAM Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 544 Results Following the collection of data gathered through the distri- bution of a questionnaire, it was possible to present a summary of the participants’ responses. The results of the survey are set out in diagrammatical from in the Appendix at the end of this paper. They have been arranged and presented systematically according to the sequence of questions in the questionnaire. Discussion On examining background information about the students participating on Module One of the M.A. in Catholic School Leadership programme, it seemed that, whilst they may not provide a typical sample of students in Higher Education, there was an acceptable cross-section of age and experience in re- spect of this particular course. Figure 1, for example, shows that, of the twenty-eight participants in the survey, twelve (43%) of them were male and sixteen (57%) were female. Three of the participants (11%) were aged under 30, ten (36%) were aged between 30 and 39, thirteen (46%) were aged between 40 and 49, and two (7%) were aged between 50 and 59 (Figure 2). Nine (32%) of the participants worked in primary schools, fifteen (54%) in secondary schools, three (11%) worked in an “all through” (Key Stage 1 - 4) academy, and 1 (3%) in a Sixth Form College (Figure 3). The information provided a profile of the students participating in the investigation. Twenty-six (93%) of the twenty-eight participants indicated that they agreed or strongly agreed that online learning pro- vided a useful opportunity for reflection on the MA programme (Figure 4). Twenty-four (83%) of them agreed or strongly agreed that they used online learning when looking for infor- mation on the M.A. programme (Figure 5). Twenty-five (90%) of them agreed or strongly agreed that they being skilled in using facilities like online learning is very important for school leaders in the twenty-first century (Figure 6). In considering students’ attitudes towards online learning, therefore, the ma- jority of the participants clearly demonstrated a positive re- sponse to online learning. Considering that students were aware that 20% of their as- sessment on the programme would receive a mark based on their contribution to online discussions, it is, perhaps, not sur- prising that there was generally a positive response to the use of online learning as this provided an incentive. Thus, with regard to the use of online learning, fourteen (50%) of the participants indicated that they accessed the facility at least once a week and thirteen (47%) indicated that they accessed the facility at least once a month (Figure 7). On the other hand, as they had been encouraged to engage with online learning every week, it might be considered disappointing that there were not more students who did so. The virtual learning environment provided a number of course tools, which are available to the students to facilitate their learning. These include Discussions, Resources Zone and Web Links. In evaluating the perceptions of students towards using online learning, an enquiry of the extent of their engage- ment of these course tools was included. All twenty-eight of the students indicated that they had en- gaged with online Discussions (Figure 8). This was most en- couraging because student participation in online discussions was considered an important component of the M.A. pro- gramme. It was, after all, an expectation that students would Participants arranged according to gender 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 MaleFemale Figure 1. Male and female. Par tici pants a rranged a c c ording to age gr oup 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 -3030-39 40-49 50-59 Age Figure 2. Age. Participants organis ed acc o rding to phase of teaching 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 Prim arySecondaryP rimary / S ec ondary6th form Figure 3. Your present school or college. respond positively to this initiative. The unanimous engage- ment of students with online Discussions would also have been influenced by the fact that 20% of the assessment of the pro- gramme was based on the frequency and quality of the stu- dents’ contributions to online discussions. The Resources Zone included a range of readings and refer- ences that were considered an important basis for research and  D. FINCHAM Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 545 I think St Mary's online provide s a use ful opportunity for r e flection on the MA in Catholic School Lea de rs hip 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 St rongly dis agreeDis agreeNot c ert ainA greeSt rongly agree Figure 4. I think online learning provides a useful opportunity for reflection on the M.A. in Catholic School Leadership. I use St Mary ' s online when look ing for informa tion for the MA in Catholic School Lea de rs hip 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 S trongly dis agreeDis agreeNot c ertainA greeSt rongly agree Figure 5. I use online facilities when looking for information for the M.A. in Catholic School Leadership. I think being skilled in using facilities like St Mary's online is very impo rtant fo r s chool lea ders in the 2 1st c e n tury 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 S trongly dis agreeDis agreeNot c ertainA greeSt rongly agree Figure 6. I think being skilled in using online facilities is very important for school leaders in the 21st century. review. Course material and handbooks drew on the informa- tion provided in these resources. Whilst the content of this fa- cility could be accessed through other more traditional methods (e.g., library books), it was hoped that students would take ad- vantage of the support that was available online. The survey indicated that all but one of the twenty-eight students accessed How of te n do y ou use St Ma ry ' s online? Daily Weekly Mo nthly 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 Figure 7. How often do you access online learning? I have engaged with online Di scussi ons 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 yes no Figure 8. I have engaged with online disc u s s ions. the Resources Zone (Figure 9). Whilst this was regarded as extremely encouraging, the aim is to ensure that all students benefit from this facility. Another facility available on online learning was Web Links. The survey showed that 21 (75%) of the participants accessed this facility (Figure 10). Whilst the aim was that all students should access this facility during the course of the module, it was evident that this facility was open to further development and encouragement. Perhaps the most interesting—and illuminating—part of the questionnaire related to participants’ responses to the open invitation in Section 6 to provide “any further comments about your attitudes and use of online learning as part of the pro- gramme towards an M.A. in Catholic School Leadership”. Again, the responses to this enquiry were generally positive, consistent with the findings gained from other questions in the survey. With reference to the open-ended question that was provided, inviting respondents to make further comments about their attitudes and use of online learning as part of their studies, only four (14%) of the participants indicated that they would like more help in using online learning. The comments ranged from “Once registered it is very easy to use” (Respondent 1) to “Not so much needing ‘help’ as having time to ‘explore’ its intrica- cies in depth” (Respondent 2).  D. FINCHAM Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 546 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 yes no I have used the Resources Zone on St Mary's online Figure 9. I have used the Resources Zone as p art of my online learning. 0 5 10 15 20 25 yes no I have accessed We b Links on St Mary's online Figure 10. I have accessed web links. One participant pointed out that there had been problems ac- cessing e-library facilities: Accessing e-library stuff—I’ve had very little success. (Respondent 11) Whilst this facility offers enormous potential for students in conducting research, the results indicated that this is an area that should be the subject of further development. Another participant helpfully suggested that other forms of support might be provided such as: Maybe a d vice on essay writing… (Respondent 23) This was a helpful proposal. Indeed, in response to this and similar suggestions, a further addition to the Course List was provided in the form of a section for the dissertation. Included in this section, moreover, advice on writing a dissertation is now provided as well as an example of a model dissertation. One benefit reflected by several participants was that it fa- cilitated the exchange of views and ideas. Thus, participants in- dicated that some advantages of using online learning includ- ed providing opportunities for … reading other people’s views… (Respondent 1) … (allowing) further reflection and the sharing of good practice (Respondent 4) … being able to offer comments back… (Respondent 1) … (being) extremely beneficial to gain feedback… (and forcing) me to reflect on my own (professional) situa- tion… (Respondent 18) … (I can) reflect on experiences (of other teache rs) through- out the country… (Respondent 24) It should be noted, however, that Respondent 24 also ob- served, trenchantly, that … there seems to be … a north/south divide! In terms of its relevance for future leaders in schools, the opportunity to work in a virtual learning environment was re- garded by respondents as an important component of leadership. This seemed to endorse the generally positive responses to the statement in the questionnaire, which invited participants’ views towards the statement: “I think being skilled in using facilities like online learning is very important for school lead- ers in the 21st century” (Figure 6). The results in dic at e d t hat 25 of the 28 participants agreed or strongly agreed to this state- ment. Respondent 14 added that it was “… essential for future leaders to use technology in this way.” Interestingly, Respon- dent 12 added: I have found online learning much more useful than NCSL8—easier to access, to navigate and generally more user-friendly. Other participants indicated that they had found that the fa- cility was easy t o use: … generally it was simple to use + effective. (Respondent 5) … provides very accessible reading resources that can be copi ed, hig hlighted and print ed. (Respondent 1) However, a number of respondents also drew attention to some difficulties and problems in their experiences of using online learning. Inevitably, perhaps, the most recurrent problem that was put forward in this respect was that of time. Respon- dents 3, 6, 7, 8 and 22, for example, all alluded to the fact that they found that using the online learning facility was time- consuming. It should be pointed out, of course, that qualities of commitment and persistence are required of all students work- ing at this level. 8The National College for School Leadership (NCSL) provides opportuni- ties for professional d evelopment fo r all teachers f rom aspiring school lead- ers to experienced headteachers.  D. FINCHAM Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 547 It is possible, too, that students were reacting to the fact that online learning implies a different way of managing and organ- ising time, compared with traditional courses, requiring them to adapt and adjust to innovative modes of study. One respondent, for example, said … I don’t think it is the way that I personally learn the best. (Respondent 22) Clearly, technological innovations and advances will require different learning skills and, as acknowledged above, leaders of the future will need to accommodate these developments. Another significant difficulty that was expressed by a num- ber of participants was that of their experiencing technical pro- blems: … ongoing IT problems + the unforeseen time it took to “work out” that a computer fault was on my private sys- tem at home meant that I could not access weekly… (Respondent 2) Having no home Internet access proves problematic. (Respondent 3) … the facility seems to become disabled… (Respondent 13) The program does not seem to work very well with new versions of word. (Respondent 19) The interface itself can sometimes be slow to run… (Respondent 27) Admittedly, limitations in the availability of computers or the inability to access the system are potential impediments to pro- gress in adopting a virtual learning environment as a compo- nent of a programme such as this. On the other hand, the ability to overcome these problems is advantageous both personally and professionally. One question that was raised was that of confidentiality. It was made clear to all students online that opinions and views expressed in the “virtual classroom” came with the caveat: Remember all that we share should be treated as CON- FIDENTIAL to this group. (Catholic Education: UNIT 1) Thus, it was pointed out that the “virtual classroom” should be regarded in the same way as any classroom in which per- sonal and professional matters are shared. However, one par- ticipant expressed concerns that I sometimes worry about confidentiality when I post per- sonal viewpoints linked to my experiences as anyone who knows me would know which school or even member of staff I am talking about. (Respondent 15) The importance of confidentiality in using a virtual learning environment cannot be overemphasised. Controversial and sen- sitive issues need to be shared with understanding and con- sideration. This, however, would be no different from any other classroom situation, where there is a presumption that students will respect the contributions made by others with due discre- tion. Limitations It has to be acknowledged that there are limitations in using a case study approach. As it is based on a particular situation, event or case, for example, one cannot necessarily draw con- clusions by extending the findings of one specific case to other contexts. Nisbet and Watt (1978: p. 78), for example, indicate that there is the question of validity that governs the extent to which the results of a case study can be generalised. As there were a number of potential drawbacks, therefore, in undertaking a case study approach, a number of considerations needed to be taken into account. Care must be taken, for exam- ple, not to make unwarranted claims from limited data to facili- tate learning and teaching in which interpersonal communica- tion, analysis and reflection has been extended to a wider popu- lation. On the other hand, whilst it is acknowledged that there are limitations to a case study approach, there are also several ad- vantages. One advantage, for example, is that it can be con- ducted speedily where time is limited. Thus, according to Bell (1996: p. 8), The case-study approach is particularly appropriate for individual researchers because it gives an opportunity for one aspect of a problem to be studied in some depth within a limited time-scale… A case study also provides the researcher with an opportunity to examine similarities, discrepancies, alternative interpreta- tions and conflicts in perspectives that might be held by the students participating in the MA programme in Catholic School Leadership. As Cohen and Manion (1994: p. 123) point out, Given the variety and complexity of educational purposes and environments, there is an obvious value in having a data source for researchers and users whose purposes may be different from our own. In order to collect the relevant data for analysis, an appropri- ate instrument of research had to be considered. Bearing in mind the small scale of the research and the decision to respect the confidentiality and anonymity of respondents, it was de- cided that the use of a questionnaire would be the most appro- priate tool. There are also potential limitations that need to be taken into account when conducting a questionnaire survey. These include the question of validity and the extent to which the results can be generalised to other situations. As the study was confined to a relatively small number of people, it would be difficult to generalise from the findings. There would also have been scope for follow-up selective interviews if time had permitted. On the other hand, there are advantages in that it was possible to dis- cern some preliminary insights from the enquiry that might provide material for further research. Whilst it can be argued that the investigation was limited to a small group of students, it did nevertheless provide an oppor- tunity to explore perceptions of learners with regard to their use of online learning. There are, too, other advantages. For exam-  D. FINCHAM Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 548 ple, a questionnaire survey can be relatively easily administered where time is limited and, if prepared well, the results of a questionnaire can be collated and analysed in a manageable way. Conclusion Potentially, participants experience innovation in a variety of ways. As in any innovation, it was anticipated that there would be some anxiety and apprehension. However, the introduction of a virtual learning environment into the M.A. programme in Catholic School Leadership represented a new and distinctive departure from traditional methods of teaching and learning used on comparable programmes, particularly as online discus- sions were to contribute to 20% of the assessment for each module. When the virtual classroom was first introduced to support of the programme, student engagement tended to reduce after the first year. The introduction of assessment to reward active par- ticipation, however, led to very significant increase in engage- ment with the online element over the whole course. Whilst some students are more comfortable than others with engagement in the virtual classroom, some are more comfort- able than others in face-to-face seminars, but, on balance, all students gain from a blend of learning methods. As with any innovation, frequent and regular use is the best way for staff and students to lea r n how to get the most from th e fa cility. It has to be acknowledged that, initially, a significant in- vestment of time has to be made to ensure that all modes of learning blend together satisfactorily. The initial restructuring of materials and resources to complement online engagement take time but, in the course of time, they only need annual mi- nor updating and tweaking. It might be anticipated that with the growing familiarity and confidence in the use of information and communication tech- nologies and with the widespread use of the Internet, the prob- lems identified by students in this survey in their experience of communicating and interacting in discussion groups in a “vir- tual classroom” are likely to decrease. The use of full distance learning within a blended learning approach is becoming more common. Students should therefore be encouraged to exploit virtual learning technologies. Indeed, looking forward to further developments in the field of information technology, there is the potential in future for the introduction of online meetings. In particular, the rapidity of technological change would sug- gest that, for the M.A. programme in Catholic School Leader- ship, opportunities online learning represent a step towards a wider use of distance learning as part of a strategy of blended learning that will embrace not only national boundaries but will potentially be extended internationally9. Significantly, the expansion of Higher Education has been accompanied by the development of open and distance strate- gies for learning and teaching. Given the potential effect of the increase in the numbers of 18 year-old students on the provision of traditional undergraduate courses10, there are implications, too, for the extension of course provision in Higher Education in the future. In crude marketing terms, by providing access to opportunities for virtual learning, there is scope for increasing the numbers of students involved in courses in Higher Educa- tion both nationally and internationally. Evidence from this research indicates that, although the writer had been concerned that students might have felt anxie- ties about the introduction of online learning as an educational resource, the general impression from the findings was that the majority of students responded positively to the innovation and felt that the opportunities provided by online activities en- hanced the quality of their learning experience. This is not nec- essarily an obvious conclusion, however. In the writer’s ex- perience innovation in education can be perceived not only as a challenge but also as a threat. Resistance and a reluctance to embrace new skills can inhibit as well as excite interest amongst potential learners. It cannot always be assumed that online learning is universally regarded as a favoured means of learn- ing. REFERENCES Barnett, R., & Hallam, S. (1999). Teaching for supercomplexity: A pedagogy for higher education. In P. Mortimore (Ed.), Understand- ing pedagogy and its impact on learning (pp. 137-154). London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd. Bell, J. (1996). Doing your research project. Buckingham: Open Uni- versity Press. Bennell, P., & Pearce, T. (2003). The internationalisation of higher edu- cation: Exporting education to developing and transnational econo- mies. International Journal of Educational Development, 23, 215- 232. doi:10.1016/S0738-0593(02)00024-X Briggs, A. R. J., & Coleman, M. (2007). Research methods in educa- tional leadership and management (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Bridges, D. (2000) Back to the future: The higher education curriculum in the 21st century. Cambridge Journal of Education, 30, 37-55. Burbules, N. C., & Callister, T. A. (1999). Universities in transition: The challenge of new technologies. Cambridge Philosophy of Edu- cation Conference, 18 September 19 99. Exley, K., & Dennick, R. (2005). Small group teaching. London and New York: Routledge Falmer. Green, A. (1997). Education, globalisation and the nation state. New York: Macmillan Press, Basingstoke and St Martin’s Press. doi:10.1057/9780230371132 Illich, I. (1971) Deschooling society. Harmondsworth: Penguin. Jarvis, P., Holford, J., & Griffin, C. (2003). The theory & practice of learning. London an d N ew Y o rk: Routledge Falmer. Lea, M. R. (2004). Academic literacies: A pedagogy for course design. Studies in Higher Education, 2 9 , 739-756. doi:10.1080/0307507042000287230 Middlewood, D., & Lumby, J. (2001). Strategic management i n schools and colleges. London: Paul Chapma n . Nisbet, J. D., & Watt, J. (1978). Case study, rediguide No. 26. Notting- ham: Nottingham University. Stenhouse, L. (1975). An introduction to curriculum research and development. London: Heinemann. Watkins, C. (2005). Classrooms as learning communities: A review of research. London Review of Education, 3, 47-64. doi:10.1080/14748460500036276 Williams, P. (2005). Lessons from the future: ICT scenarios and the education of teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 31, 319- 339. doi:10.1080/02607470500280209 Yin, R. (2002). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 9It is hoped to develop links, for example, wit h I nd ia and Nigeria. 10According to Anthea Lipsett in the Guardian (http://www.guardian.co.uk/ education/2009/jan/15/ucas-universities-students), for example,in 2008 “the number of fulltime students accepted on to courses rose by 10.4%, 43,197. This may be the result of a combination of improved marketing of courses and greater availability of access to the Internet.

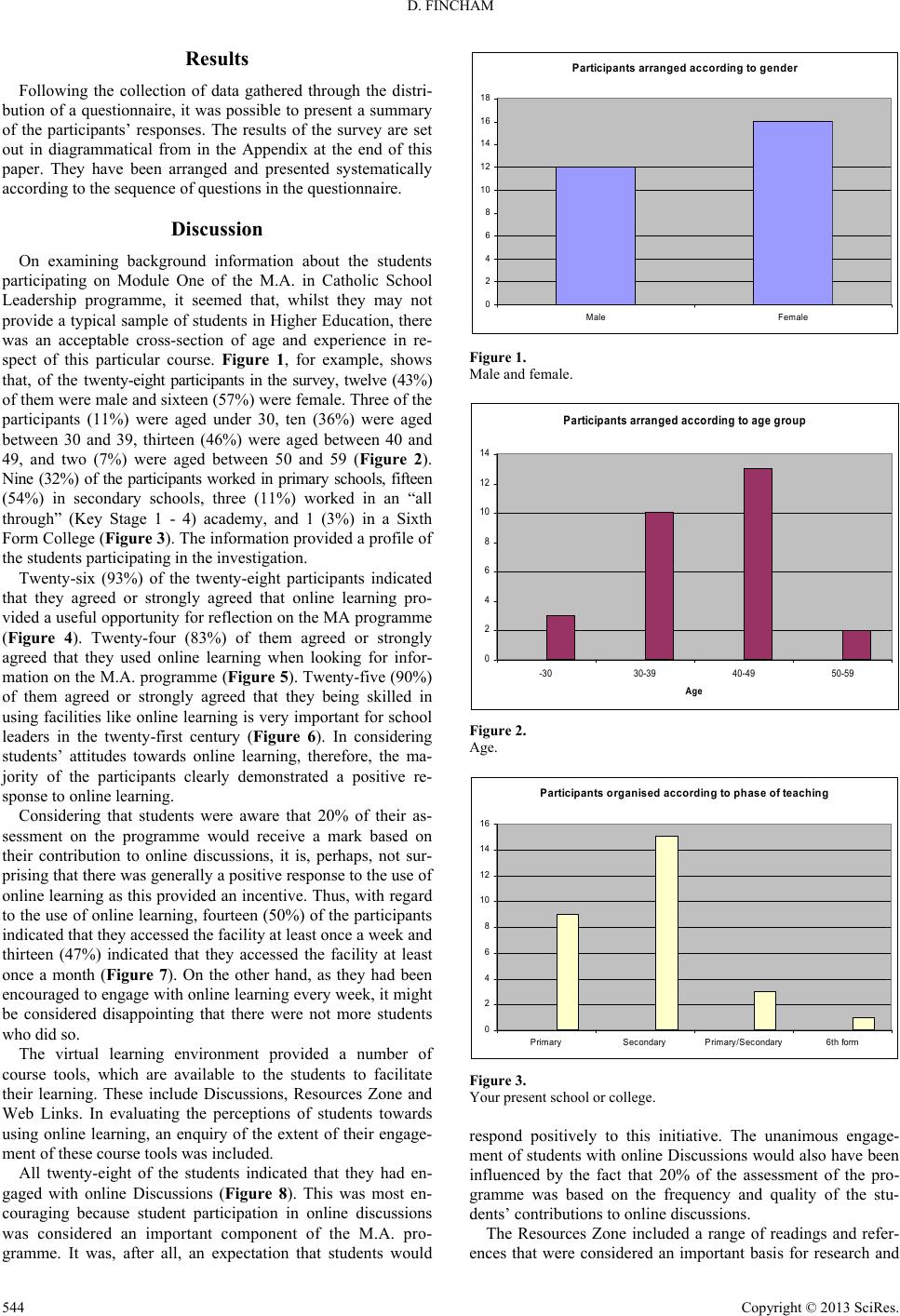

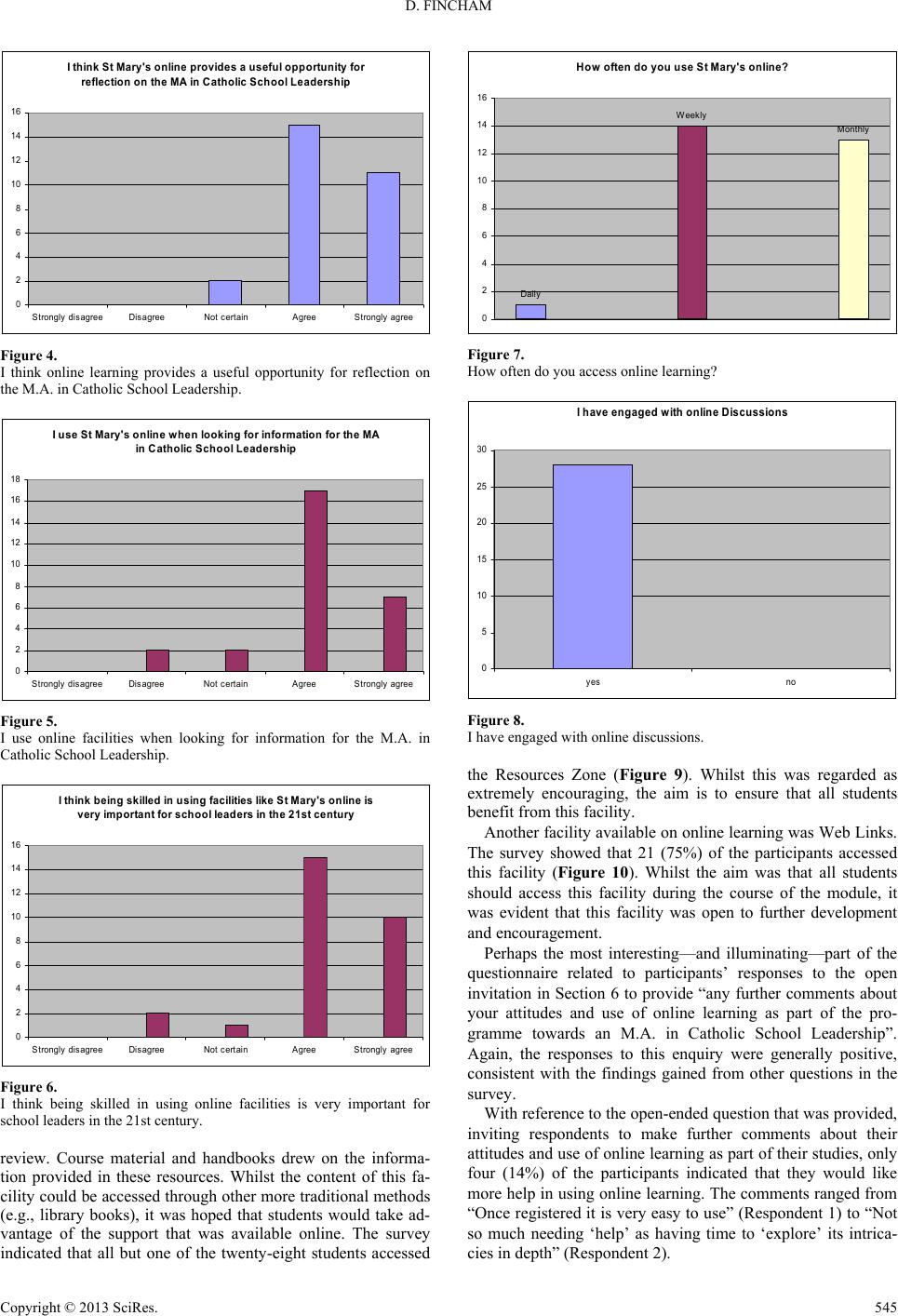

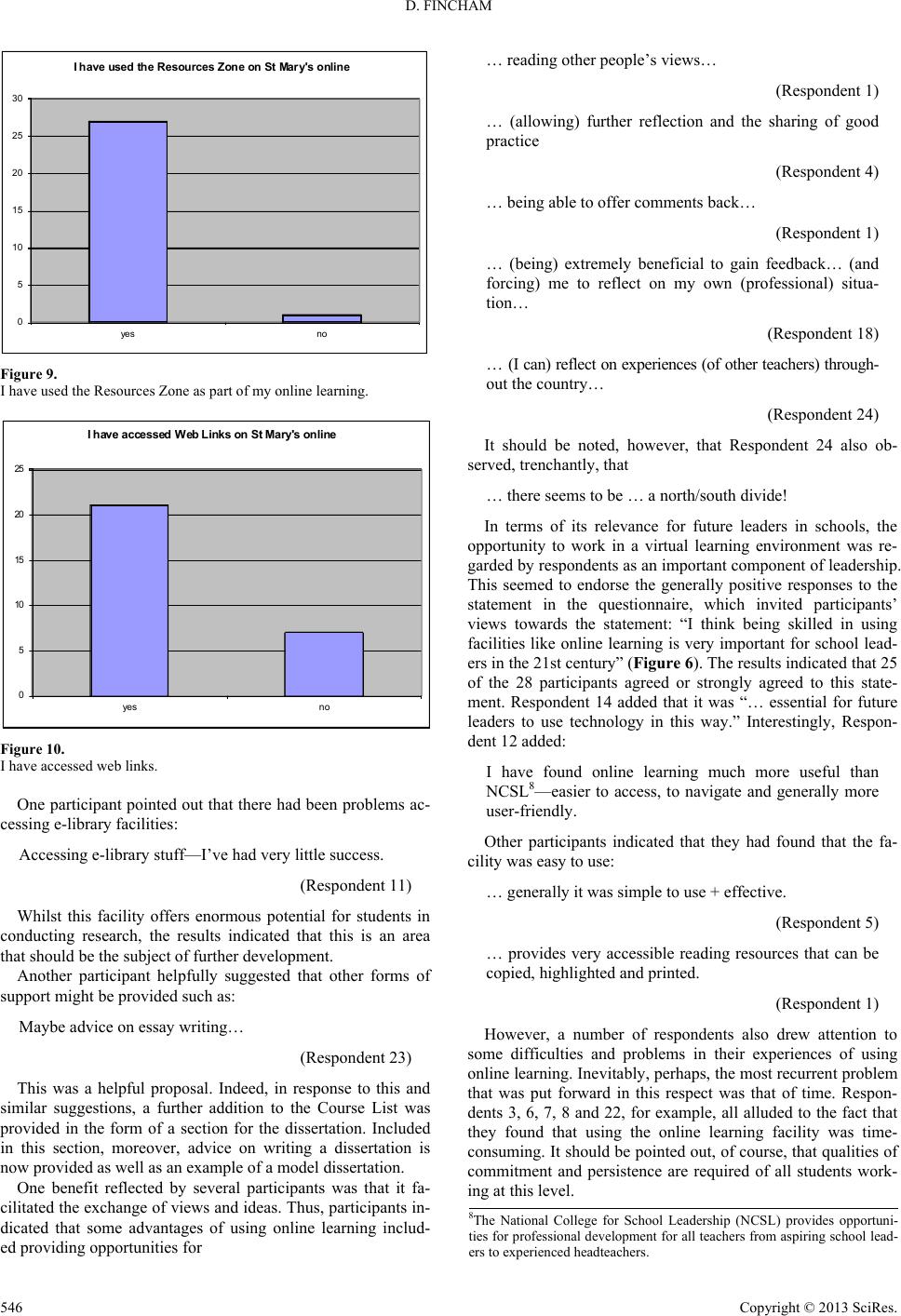

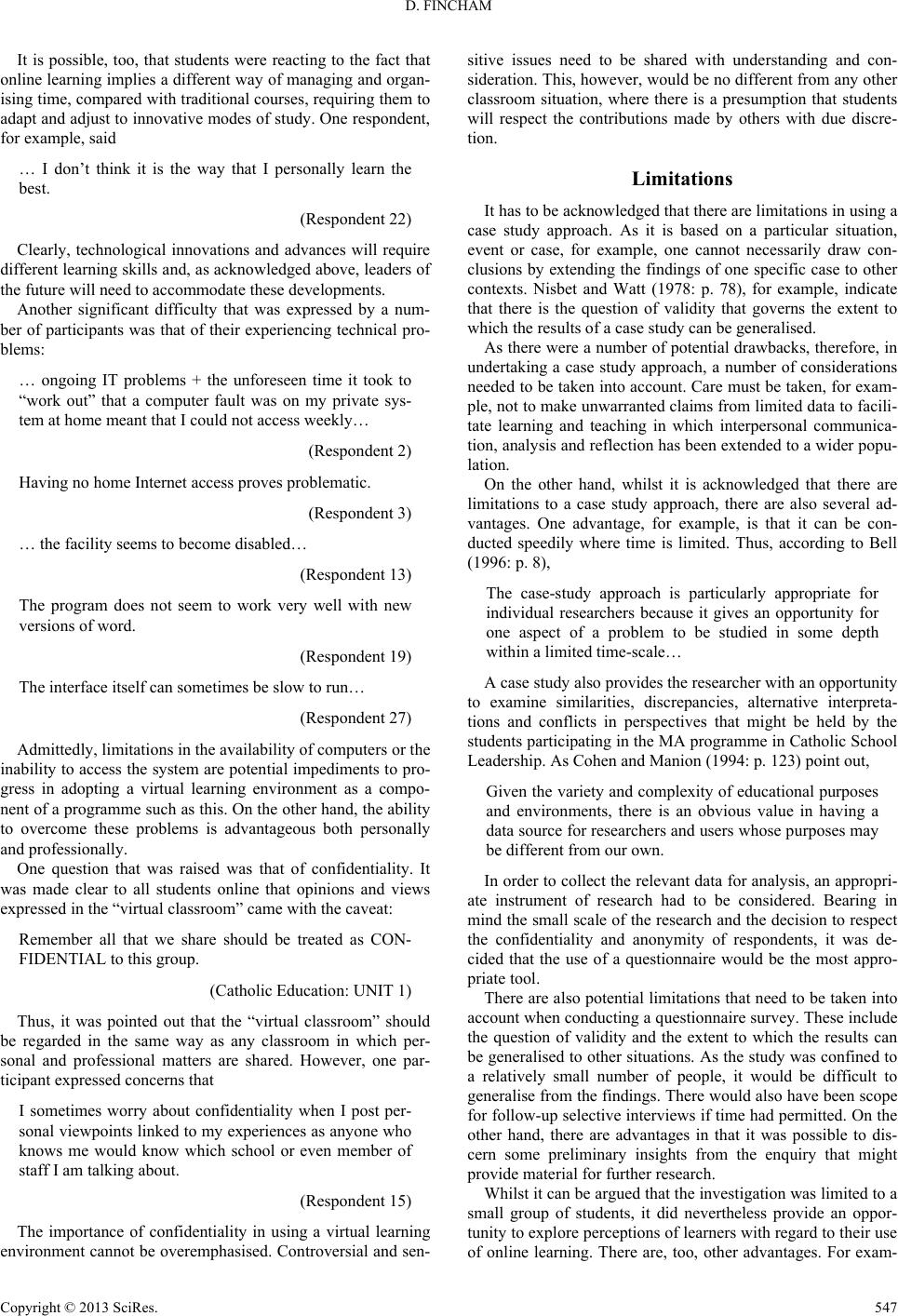

|